Abstract

Soil salinization severely constrains crop productivity and ecosystem services in arid regions. While the application of soil amendments represents a promising mitigation strategy, it remains uncertain whether this practice can effectively enhance soil quality index (SQI), crop productivity, and ecosystem service value (ESV) in saline–alkali farmlands. To address this, a three-year field experiment was conducted to analyze the effects of different amendments (rotary-tilled straw return (RT), plowed straw return (PL), biochar (BC), desulfurized gypsum (DG), DG combined with organic fertilizer (DGO), and an unamended control (CK)) on SQI, sunflower productivity, and ESV in a saline–alkali farmland of arid Northwest China. Results indicated that the BC treatment significantly reduced bulk density by 5.1–7.6% and increased porosity by 6.3–8.3% compared to CK. Both BC and DGO significantly increased soil organic matter and available nutrients while reducing saline ions (HCO3−, Cl−, Na+), which reduced soil salinity by 21.2–33.6% and 19.9–26.5%, respectively. These synergistic improvements enhanced the SQI by 76.8% and 74.1% for BC and DGO, respectively, relative to CK. Correlation analysis revealed strong positive relationships between SQI and crop nitrogen uptake and yield. Accordingly, BC and DGO increased nitrogen uptake by 74.9–129.0% and yield by 12.2–45.2%, with BC offering more stable benefits over time. Furthermore, BC increased the values of agricultural product supply, nutrient accumulation and climate regulation, thereby increasing the total ESV by 13.7–53.9% relative to CK. In summary, BC and DGO are effective strategies to synergistically enhance soil quality, crop productivity, and ecosystem services in saline–alkali farmlands of arid regions.

1. Introduction

Soil salinization, a widespread form of soil degradation in arid, semi-arid, and coastal regions, poses a serious threat to global soil quality, agricultural productivity, and ecosystem services functions [1,2,3]. Statistical evidence indicates that over 1.13 billion hectares of land worldwide are affected by salinization [4], with this area expanding at an annual rate of 1–2% [5]. The inhibitory effect of high soil salinity on crops is mainly attributed to osmotic, ionic, and oxidative stresses, which disrupt water and nutrient uptake [6]. Furthermore, excessive exchangeable Na+ in saline–alkali soils leads to the collapse of soil structure by dispersing aggregates, causing soil solidification, and reducing pore space [7]. These adverse effects collectively compromise soil quality and crop productivity, while also impairing the soil ecosystem and its vital services [8]. Therefore, it is imperative to adopt effective agricultural practices to improve saline–alkali soil quality, enhance crop productivity, and restore associated ecosystem services function.

In recent decades, various amendments have been employed to improve saline–alkali soils and support crop production. Among organic amendments, the straw return practice (e.g., via rotary tillage or plowing) is widely adopted for its ability to release nutrients, improve soil structure, and facilitate salt leaching [9,10,11]. A more efficient derivative of straw is biochar, produced through pyrolysis. Its high porosity, carbon-rich composition, and extensive specific surface area help optimize soil microstructure and reduce nutrient leaching, thereby alleviating saline–alkali stress and promoting crop growth [12,13]. For instance, a long-term study demonstrated that successive biochar amendment not only improved soil aggregate stability (mean weight diameter increased by 85%) but also increased key nutrient availability (e.g., available phosphorus by 241%), leading to a 189% increase in cumulative aboveground biomass over five crop rotations [14]. Among chemical amendments, desulfurization gypsum (DG), a byproduct of sulfur removal from flue gases in coal-fired power plants, is primarily composed of CaSO4·2H2O [15]. Its core mechanism involves the displacement of Na+ ions on soil colloids by Ca2+ ions, thereby effectively reducing soil pH and sodium adsorption ratio, and mitigating Na+ toxicity [16]. Simultaneously, DG can supply essential nutrients such as calcium and sulfur, thereby supporting crop growth [17]. However, DG alone cannot compensate for the inherent organic matter deficit and low fertility of saline–alkali soils [18]. Consequently, the co-application of DG with organic fertilizer has emerged as a promising integrated strategy to simultaneously reduce alkalinity and enhance soil fertility through synergistic effects [19]. Despite its potential, systematic evaluation of the combined use of DG and organic fertilizers under saline–alkali conditions in the arid regions of China remains limited, and its effectiveness is still not well understood.

Although numerous studies have investigated the effects of individual soil amendments, their practical efficacy is often constrained by diverse factors such as climate, soil type, and cropping systems [20,21]. These constraints highlight the necessity of conducting localized empirical research tailored to specific regional conditions and agricultural contexts. However, systematic comparisons of various amendment strategies, such as biochar, straw return (via rotary tillage or plowing), DG, and its combined application with organic fertilizer, remain scarce in saline–alkali farmland. Furthermore, existing studies have predominantly focused on the responses of soil physicochemical properties or crop yield to different soil amendments, while a systematic analysis of their integrated impacts on soil quality, crop yield and ecological benefits remains lacking. Specifically, few studies have assessed the soil quality index (SQI), calculated from key physicochemical indicators, and the ecosystem service value (ESV), which reflects provisioning and regulating functions, under different soil amendment types. Consequently, a multidimensional evaluation of the combined effects of different amendment types from the perspective of “soil quality–crop productivity–ecosystem services” remains absent. This gap hampers a comprehensive understanding of the overall ecological and agronomic benefits offered by different soil amendment types.

The Hetao Irrigation District (HID), located in the arid northwest of China, is a typical agricultural region severely affected by saline–alkali stress. Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), as a major economic crop in the region, suffers from substantial yield losses and growth inhibition under these conditions, accompanied by a pronounced decline in farmland ecosystem services [22,23]. Therefore, identifying suitable amendment practices that can simultaneously improve the soil quality, increase crop yield, and enhance ecological service functions is of critical importance for this region. Based on this, a three-year field experiment was conducted in the HID to systematically compare the comprehensive effects of different amendment practices on saline–alkali farmland. The main research objectives were to (1) investigate the effects of various amendment practices on saline–alkali soil physicochemical properties and the SQI; (2) evaluate their efficacy in improving sunflower nitrogen (N) uptake, yield, and partial N productivity; and (3) assess their impact on the value of key farmland ecosystem services. By addressing these objectives, this study aims to determine effective strategies for the sustainable management of saline–alkali sunflower farmlands in arid regions, providing a scientific basis for promoting soil improvement practices that enhance both agricultural productivity and ecosystem services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

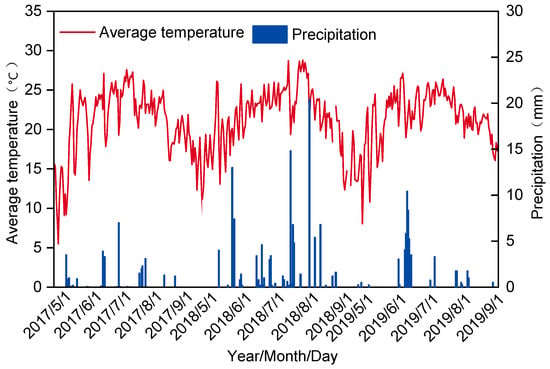

The field experiment was conducted from 2017 to 2019 at the Sandaoqiao Experimental Station in the HID of Inner Mongolia, China (40°49′ N, 106°54′ E). The region has a semi-arid to arid continental climate with marked seasonal variation. Annual precipitation averages 138.2 mm, while potential evaporation reaches 2094.4 mm. The mean annual temperature is 7.9 °C, and the average wind speed is approximately 2–3 m s−1 [21]. A drainage ditch, 1.5 m deep, is located 2.2 m from the experimental site for drainage and salt removal. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Soil Taxonomy [24], the soil in the 0–20 cm layer was identified as Aridisol (Sodic Haplocambids). Based on the USDA Textural Classification [25], the soil texture in this layer was classified as silt loam. Initial soil properties in the 0–20 cm root zone were as follows: pH of 8.3, bulk density (BD) of 1.4 g cm−3, and soil organic matter (SOM) of 12.6 g kg−1, soil salt content of 5.2 g kg−1, available N of 50.7 mg kg−1, available phosphorus (AP) of 8.8 mg kg−1, available potassium (AK) of 218.5 mg kg−1, exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP) of 28.2%. A miniature weather station (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA) was installed in the test field, recording precipitation and air temperature at 30 min intervals. Figure 1 shows the mean daily air temperature and daily rainfall during the experimental period.

Figure 1.

Daily precipitation and average air temperature during the growth period of sunflowers in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

2.2. Experimental Design and Practice Management

The experiment consisted of six treatments: rotary-tilled straw return to 0.1 m (RT), plowed straw return to 0.3 m (PL), biochar (BC), desulfurized gypsum (DG), DG combined with organic fertilizer (DGO) treatment, and a control without any amendment (CK) corresponding to the local farmer practices. The treatments followed a randomized complete block design with three replications. Each plot measured 30 m × 5 m (150 m2). Before the experiment began in early May 2017, primary tillage was performed in all plots using a rotary cultivator. Specifically, the RT plots were rototilled to 0.1 m depth, while the PL, BC, DG, DGO, and CK plots were tilled to 0.3 m depth. No further amendments were applied in 2018 and 2019.

The biochar was produced from corn residue via slow pyrolysis in a steel carbonization furnace under oxygen-deprived conditions (400–500 °C for 8 h), with an appropriate field application rate of 22.5 t ha−1. For straw amendments, corn straw was first chopped into pieces (approximately 0.5 m) using a local hay cutter. The application rates for rotary tillage and plowing incorporation were set at 20.6 t ha−1 and 12.0 t ha−1, respectively. Desulfurized gypsum, obtained as a by-product from Baotou Second Thermal Power Plant, was applied at 37.5 t ha−1, an application rate determined based on ion exchange principles. Its main component was CaSO4·2H2O. Organic fertilizer was produced by the aerobic fermentation of sheep manure at local composting stations. The DGO treatment involved the co-application of desulfurized gypsum and organic fertilizer, each at 37.5 t ha−1. The application rates for biochar, straw, and organic fertilizer were based on local government recommendations and prevailing farmer practices, enabling a direct assessment of locally suitable amendment strategies for the study area and similar regions.

Sunflower cultivar ‘902’, which is widely cultivated in the HID region, was sown on 18, 20, and 24 May, and harvested on 23, 27, and 27 September in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively. The plant spacing was 50 cm and row spacing was 60 cm, resulting in a plant density of approximately 33,000 per hectare. Wide rows were covered with polypropylene film. All experimental treatments followed identical irrigation and fertilization regimes. Drip irrigation was employed throughout the growing period. Irrigation events were initiated when tensiometer readings at 0–20 cm depth indicated a soil matric potential of −25 kPa, with each event supplying 20 mm of water. Three irrigation events of equal volume were applied at the budding, flowering, and grain-filling stages each year, occurring on 1 July, 3 August, and 21 August in 2017; on 23 June, 27 July, and 14 August in 2018; and on 1 July, 8 August, and 20 August in 2019. Basal fertilization was uniformly applied to all plots at rates of 101 kg N ha−1, 192 kg P ha−1, and 17 kg K ha−1. An additional 105 kg N ha−1 was supplied via fertigation, divided equally among the budding, flowering, and grain-filling stages, with 35 kg N ha−1 applied at each stage. The nutrient sources were diammonium phosphate (39% P2O5), urea (46.67% N), and a compound fertilizer (30% N, 5% P2O5, 5% K2O).

2.3. Sampling Collection and Measurements

2.3.1. Soil Properties and Plant Samples

At the sunflower maturity stage in 2017, 2018 and 2019, soil samples were collected from the main root zone (0–30 cm depth) using a soil auger for the analysis of soil physicochemical properties. Soil BD was determined using the undisturbed core method. Briefly, soil BD was measured by carefully inserting a stainless-steel cutting ring of known volume (100 cm3; inner diameter: 5 cm, height: 5 cm) into the soil at the target depths. Each intact soil core was extracted, oven dried at 105 °C to constant weight, and weighed. BD was calculated as the dry mass divided by the fixed core volume. Soil total porosity was calculated from the measured BD using the standard formula: Porosity(%) = 1 − (BD/SPD), where SPD is the soil particle density, assumed to be 2.65 g cm−3 [26,27]. Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in a 1:5 soil–water suspension using a pH meter (FE28, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) and a conductivity meter (DDSJ-308A, INESA Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), respectively [28]. Na+ ions were measured by flame photometry, Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions were determined by EDTA titration, SO42− ions were analyzed by indirect EDTA complexometric titration, Cl− ions by AgNO3 titration, and HCO3− ions by double-indicator acid-base titration [29]. The SOM content was determined by the potassium dichromate oxidation method with external heating [30]. Alkali-hydrolyzable N (AN) was measured by the diffusion method, soil AP was determined using the 0.5 M NaHCO3 extraction method, and AK by flame photometry [31].

At the maturation stage, sunflower yield was determined by harvesting a 4 m2 area from each plot. Subsequently, three representative plants were sampled from the central rows of each plot for aboveground biomass determination. The collected plants were first heated at 105 °C for 30 min to terminate enzymatic activity, followed by oven-drying at 85 °C until constant mass was attained, and the resulting dry weight was recorded. The N content in sunflower samples was determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario Macro CN, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). For analysis, 50.0 mg of ground, dried plant material (particle size: 0.5 mm) was weighed and sealed in a tin foil capsule prior to measurement [32].

2.3.2. Greenhouse Gases Sampling and Measurement

Greenhouse gas (GHG) fluxes were monitored using the static chamber–gas chromatography technique during the sunflower growing season each year. For each treatment, three static dark chambers were deployed per plot. Each chamber consisted of a base frame (40 cm × 40 cm × 15 cm) inserted 10 cm into the soil and a removable top box (40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm). To ensure gas homogeneity, a small fan was mounted inside the top box, and a sealing strip was attached to its bottom to prevent leakage. GHG emissions were monitored at approximately 10-day intervals during the growing season, except following irrigation or fertilization events, when the sampling interval was reduced to 2–3 days. All gas samples were collected between 9:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. During each sampling, gas was manually extracted from the chamber using a 60 mL polypropylene syringe at 0, 10, 20 and 30 min after chamber closure. Samples were stored in sealed plastic bags and analyzed within 48 h using a gas chromatograph (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Kyoto, Japan). A linear regression method between gas concentrations and time interval was used to calculate the CO2, N2O and CH4 fluxes [33].

2.4. Calculations

In agricultural production systems, the utility of soil quality assessments as stand-alone tools is limited unless linked to productivity predictions [34]. Thus, to effectively evaluate soil quality, an SQI is typically developed by integrating key soil indicators that are significantly correlated with crop yield. We evaluated SQI in the third year after applying the amendment treatments. The SQI was developed using the following procedure: First, key soil indicators were selected. A stepwise regression analysis was performed using soil physicochemical properties as independent variables and crop yield as the dependent variable. Indicators that reached a statistically significant relationship with yield were selected as valid indicators for constructing the SQI [35]. Then, each selected soil indicators were normalized to a score between 0 and 1. The indicators were then categorized into two groups based on their relationship with soil quality: those where “more is better” (e.g., SOC, AN, AP, AK) were scored using Equation (1), while those where “less is better” (e.g., EC, Na+) were scored using Equation (2) [36]:

where Ri is the linear score of the soil indicator; X, Xmax, and Xmin represent the measured, maximum, and minimum values of that indicator, respectively.

The SQI was then calculated using the SQI-area approach, which evaluates the integrated radar chart area formed by all soil indicators [36]:

where n is the number of indicators, π = 3.14.

The partial N productivity (PNP, kg kg−1) was calculated using Equation (4):

where Ygrain represents the yield (kg ha−1) and Fnitrogen represents the amount of N fertilizer applied (kg ha−1).

In this study, farmland ESV was classified into agricultural products supply value, SOM accumulation value, soil nutrient accumulation value, and climate regulation value, taking into account both the specific conditions of the study area and previous studies [37,38,39].

The agricultural products supply value was calculated using Equation (5):

where Vap is the agricultural products supply value (CNY ha−1); Pc is the market price of sunflowers (CNY kg−1); Mi is the input materials (seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, soil amendments, plastic mulches, electricity for irrigation, drip irrigation tapes, and agricultural machinery operations); Vi is the market price of input materials; Cl is the labor price per unit area (CNY ha−1).

The organic matter accumulation value in the farmland ecosystem was assessed using the SOM retention method and the opportunity cost method [40] according to Equation (6):

where Vo is the SOM accumulation value (CNY ha−1); H is the depth of tilled soil (0.3 m); OMS is the SOM content (g kg−1); ρs is soil bulk density (g cm−3); Po is the organic matter price, (CNY t−1), the price of organic matter is based on the opportunity cost price of fuelwood is 51.3 CNY t−1 and the ratio of fuelwood to organic matter is 2:1.

In this study, soil AN, AP, and AK contents were selected to evaluate the soil nutrient accumulation function of the farmland ecosystem. Due to the lack of market-based prices for soil nutrients, the shadow price method was employed to convert AN, AP, and AK in the soil into the average prices of N, P, and K fertilizers, respectively [41]. The economic value of soil nutrient accumulation was calculated as follows:

where Vn is the soil nutrient accumulation value (CNY ha−1); Di is the soil AN, AP, AK content (mg kg−1); Pn represents the price of the corresponding fertilizer for AN, AP, and AK, respectively. Based on market research, the prices of N, P, and K fertilizers are 4.3 CNY kg−1, 5.3 CNY kg−1, and 3.5 CNY kg−1, respectively.

Farmland ecosystems provide climate regulation through the release of O2, fixation of CO2, and emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs: CO2, CH4, and N2O). According to the equation of photosynthesis, the accumulation of 1.00 g of plant dry matter corresponds to the fixation of 1.63 g of CO2 and the release of 1.19 g of O2. Using the dry matter mass of sunflower at maturity, the amounts of CO2 fixed and O2 released were converted into economic values following Equations (8) and (9), respectively [42]:

where VCO2 represents the carbon sequestration value (CNY ha−1); Dbiomass denotes the dry biomass of sunflowers (kg ha−1); CCO2 denotes the value of fixed CO2, taken as 0.63 CNY kg−1; 3/11 is the proportion of carbon in CO2; VO2 indicates the O2 release value (CNY ha−1); CO2 refers to the O2 production value, taken as 0.38 CNY kg−1, which is the average calculated using the industrial O2 production method and the afforestation cost method [43].

The economic value of GHG emissions was calculated based on the global warming potential (GWP). Specifically, emissions of N2O and CH4 from farmland were converted into CO2 equivalents, and their economic value was then assessed by the GWP and carbon sequestration cost [44]:

where Va1 is the negative value of GHG emissions (CNY ha−1); GWP is the global warming potential (kg ha−1); FCH4, FN2O, and FCO2 are accumulative seasonal emissions of CH4, N2O and CO2 (kg ha−1).

The total value of ecosystem services was calculated as the sum of the values for agricultural products supply, SOM accumulation, soil nutrient accumulation, and climate regulation, calculated using Equation (12):

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2019, and visualizations were created with Origin 2021 software. All statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A one-way ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of different treatments (RT, PL, BC, DG, DGO, and CK) on soil physicochemical properties, SQI, sunflower N uptake, yield, partial N productivity, and farmland ESV. The least significant difference method (LSD) at the p = 0.05 level was used to determine significant differences. Stepwise regression analysis was performed using DPS software (version 7.05)to analyze the relationships between soil physicochemical properties and sunflower yield.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physical Properties and Nutrient Availability

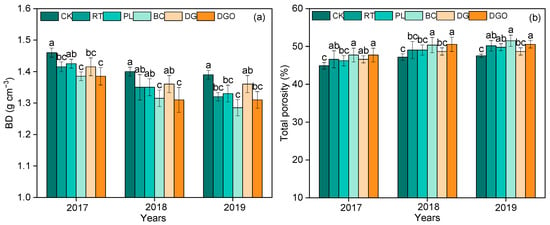

The impacts of different treatments on soil BD, total porosity, SOM, AN, AP and AK at the end of the 2017 to 2019 growing seasons are shown in Figure 2. The results indicated that all amendment treatments generally decreased soil BD and increased soil total porosity compared with the CK (Figure 2a,b). Among them, the BC treatment resulted in the lowest BD and the highest soil total porosity, reducing BD by 5.1–7.6% and increasing total porosity by 6.3–8.3% relative to the CK (p < 0.05). Consequently, BC treatment proved most effective in alleviating soil compaction and enhancing soil porosity.

Figure 2.

Soil physiochemical properties in the 0–30 cm layers for different treatments at the end of the sunflower growing season in 2017, 2018, and 2019. (a) Soil bulk density (g cm−3); (b) Total porosity (%); (c) Soil organic matter (g kg−1); (d) Alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen (mg kg−1); (e) Available phosphorus (mg kg−1); (f) Available potassium (mg kg−1). Note: Error bars represent standard error of means (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). BD, SOM, AN, AP, and AK represent bulk density, soil organic matter, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium, respectively. CK, RT, PL, BC, DG and DGO represent the treatments without any amendment, straw return with rotary tillage, straw return with plowing, biochar, desulfurized gypsum and desulfurized gypsum combined with organic fertilizer, respectively.

No significant difference in SOM was observed between the CK and DG treatments from 2017 to 2019 (Figure 2c). In contrast, other amendment treatments (RT, PL, BC, and DGO) significantly increased SOM (p < 0.05) compared with the CK. Over the three-year period, the RT, PL, BC and DGO treatments enhanced SOM content by 16.0–27.3%, 16.4–29.2%, 26.6–45.4% and 21.5–24.2%, respectively, relative to the CK. Similarly, the amendment treatments significantly enhanced the contents of AN, AP, and AK (p < 0.05) (Figure 2d–f). The BC treatment resulted in the highest AN content in 2018 and 2019, which was 58.7–68.6% higher than that of the CK. The DGO treatment also substantially enhanced AN by 36.8–56.5% in 2018 and 2019. AP showed a similar trend, with the BC achieving the highest AP content, followed by the DGO treatment, with increases of 33.4–77.9% and 28.8–57.8%, respectively, compared with the CK (p < 0.05). As for AK, the RT, PL, BC, DG, and DGO treatments showed notable enhancements after three years of application, with increases of 12.6–37.7%, 15.7–41.1%, 15.0–49.2%, 7.5–22.8%, and 11.6–28.5%, respectively, relative to the CK. Overall, these results indicate that the applied amendments enhanced soil nutrient contents to varying degrees, with BC and DGO being the most effective.

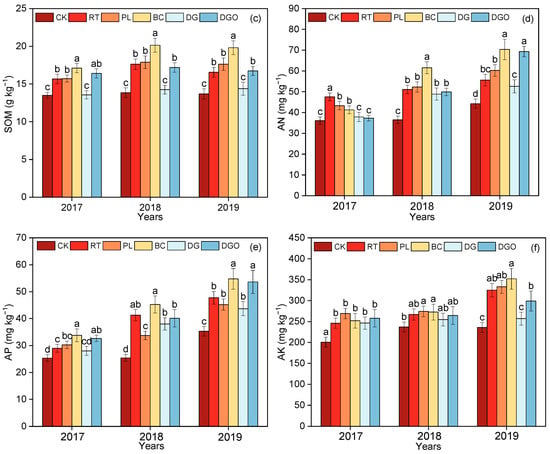

3.2. Soil Soluble Ion Composition and Salinity

The composition of soil soluble ions and EC was significantly influenced by the amendment treatments (Figure 3). Over the three-year period, HCO3− concentrations were generally lower in all amended treatments than in the CK (Figure 3a–c). A similar trend was observed for Cl−, with most treatments showing reduced concentrations; the BC treatment consistently maintained the lowest levels, specifically reducing Cl− by 7.3–35.8% relative to the CK (p < 0.05). In contrast, SO42− concentrations were substantially increased in the DG and DGO treatments, and were 4.5–9.8% higher than those in the other treatments over the three years. Similarly, Ca2+ concentrations were substantially higher in the DG and DGO treatments, with increases of 0.6–7.4 times and 0.6–8.9 times, respectively, relative to the CK. Moreover, the other amendments also significantly enhanced Ca2+ concentrations and were 0.1 to 1.9 times higher than the CK. Mg2+ concentrations were generally increased under all amendment treatments compared to the CK. Notably, Na+ concentrations, a key factor in soil sodicity, were highest in the CK and were significantly reduced in all amended treatments (p < 0.05). The most pronounced decreases were observed under the BC, DG, and DGO treatments, which reduced Na+ by 30.6–47.2%, 27.2–49.7%, and 44.6–56.9%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Changes in major soluble ion content and EC in the 0–30 cm soil layers under different treatments in 2017, 2018, and 2019. (a) Soil soluble ion content in 2017 (cmol kg−1); (b) Soil soluble ion content in 2018 (cmol kg−1); (c) Soil soluble ion content in 2019 (cmol kg−1); (d) Soil EC from 2017 to 2019 (mS cm−1). Note: Error bars represent standard error of means (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). CK, RT, PL, BC, DG and DGO represent the treatments without any amendment, straw return with rotary tillage, straw return with plowing, biochar, desulfurized gypsum and desulfurized gypsum combined with organic fertilizer, respectively.

All amendments effectively reduced soil salinity (Figure 3d). Among them, the BC and DGO treatments were the most effective, consistently maintaining the lowest EC values throughout the experimental period. Compared to the CK, the BC and DGO treatments decreased EC by 19.9–33.6% over the three years (p < 0.05), with the largest reduction observed in the BC treatment in the third year. These results demonstrate that the amendments, particularly BC and DGO, substantially improved the soil’s ionic environment and alleviated soil salinization in the study area.

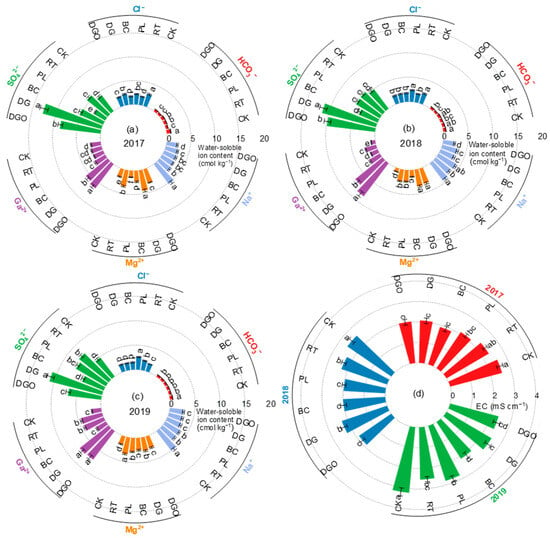

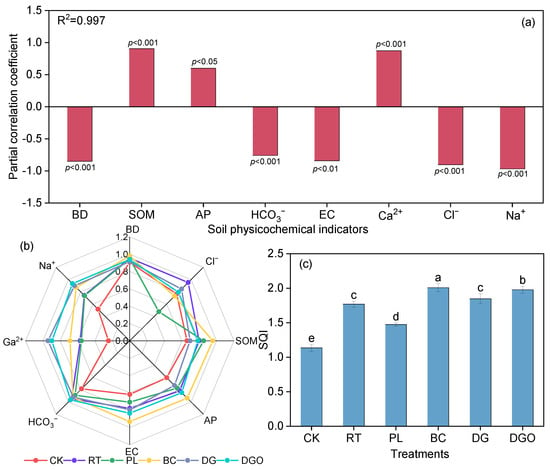

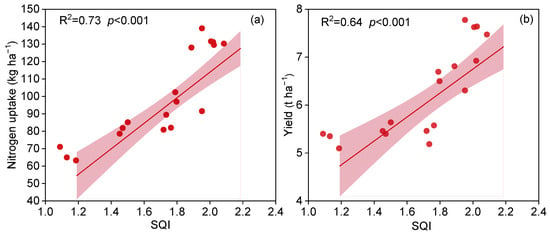

3.3. Soil Quality Index

Stepwise regression analysis identified soil BD, SOM, AP, EC, HCO3−, Ca2+, Cl− and Na+ as the key soil properties significantly associated with crop yield (all p < 0.05; Figure 4a). These variables were subsequently selected as indicators for calculating the SQI. Most amendment treatments improved these eight soil indicators relative to the CK (Figure 4b), leading to significantly higher SQI values (Figure 4c). Among the treatments, the BC treatment resulted in the highest SQI, which was 76.8% higher than that of the CK treatment. The RT, PL, DG, and DGO treatments also increased SQI by 55.8%, 29.8%, 62.6%, and 74.1%, respectively, relative to the CK. In summary, all amendments improved SQI, with the BC treatment demonstrating the most pronounced positive impact. In addition, the SQI was significantly and positively correlated with sunflower N uptake (Figure 5a) and yield (Figure 5b) (all p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Impacts of different treatments on soil quality index (SQI). (a) Partial correlation coefficients of physicochemical properties with yield; (b) Soil physicochemical property scores under different treatments; (c) SQI under different treatments. Note: Error bars represent standard error of means (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). BD, SOM, AP, and EC represent bulk density, soil organic matter, available phosphorus, and electrical conductivity, respectively. CK, RT, PL, BC, DG and DGO represent the treatments without any amendment, straw return with rotary tillage, straw return with plowing, biochar, desulfurized gypsum and desulfurized gypsum combined with organic fertilizer, respectively.

Figure 5.

Relationships between the SQI and sunflower N uptake (a). Relationships between SQI and sunflower yield (b). Note: The solid and shadow represent the linear regression lines and 95% confidence intervals. The R2 value denotes the goodness of fit of the regression. The p value shows the significance (p < 0.05) based on Spearman’s correlation test.

3.4. Sunflower Biomass, N Uptake, Yield, and Partial N Productivity

Sunflower dry biomass, N uptake, grain yield, and PNP were significantly affected by the different amendment treatments over the three-year study (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Overall, all amendments generally enhanced sunflower biomass and N uptake relative to the CK. In 2017, the DG treatment obtained the highest biomass, which was 27.3% higher than the CK, while the BC treatment resulted in the highest N uptake, exceeding the CK by 87.0%. In 2018 and 2019, the BC and DGO treatments showed more pronounced improvements. For instance, in 2019, BC and DGO treatments increased biomass by 44.7% and 40.1%, and N uptake by 103.5% and 100.1%, respectively, compared with the CK. Notably, the BC treatment resulted in a greater increase than the DGO treatment. The effects of different amendments on yield and PNP were consistent with their effects on sunflower biomass and N uptake. The BC treatment consistently achieved the highest yield and PNP across all three years, with the most notable results in the third year, where it increased yield by 17.4–45.2% over the CK (p < 0.05). The DGO treatment also significantly improved yield by 12.1–35.7% (p < 0.05). Overall, the BC and DGO treatments effectively improved sunflower productivity and N use efficiency in the saline–alkali soil, with the BC treatment exhibiting particularly stable and comprehensive enhancements throughout the study period.

Table 1.

Aboveground dry biomass, N uptake, yield, and partial N productivity in 2017–2019.

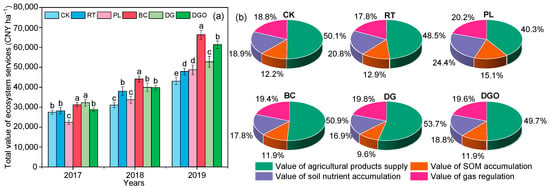

3.5. Farmland Ecosystem Service Value

The sunflower farmland ESV for agricultural products supply, organic matter accumulation, and soil nutrient accumulation under different treatments are shown in Table 2. In 2017, the agricultural product supply values for the RT, PL, and DGO treatments were slightly lower than those of the CK. However, from 2018 to 2019, the agricultural product supply values of all amendment treatments exceeded those of the CK. Among them, the BC treatment showed the most stable and significant enhancement, increasing the value of agricultural products supply by 9.4–58.6% relative to the CK over the three years. The DGO treatment also exhibited progressively stronger effects, achieving a 46.2% increase over the CK by 2019, indicating that long-term application of soil amendments contributes to sustained improvement in agricultural economic returns. In terms of SOM accumulation, all treatments (except DG) had higher functional values than the CK. For soil nutrient accumulation, the BC treatment consistently achieved the highest economic values for AN and AP in 2018 and 2019, and the DGO treatment also significantly enhanced the accumulation values of AN and AP. For the AK accumulation value, the PL treatment exhibited the most notable improvement, with an increase of 12.4–37.0% compared to the CK. Overall, with the exception of DG, all treatments significantly increased the total soil nutrient accumulation value and exhibited a clear upward trend over time. The BC treatment provided the greatest improvement, enhancing the total soil nutrient accumulation value by 18.5–39.1% compared to the CK.

Table 2.

Values of agricultural products supply, SOM accumulation and soil nutrient accumulation in 2017–2019.

Soil amendments also significantly influenced the climate regulation value (Table 3). The BC treatment achieved the highest value for carbon sequestration and oxygen release, exceeding the CK by 10.0–43.7%, followed by the DGO with a 9.0–41.1% increase. However, while providing these positive effects, the agricultural ecosystem also generates GHG emissions. Notably, the BC treatment resulted in the lowest negative value associated with GHG emissions, demonstrating significant potential for emission mitigation. Integrating the effects of carbon sequestration, oxygen release, and GHG emissions, the BC treatment achieved the highest total climate regulation value, surpassing the CK by 13.3–63.1%. In conclusion, the BC treatment also demonstrated the highest total ESV, with a 13.7–53.9% increase over the CK (Figure 6a). The RT, PL, DG, and DGO treatments increased the total ESV by 2.4–22.6%, 8.7–13.1%, 17.1–28.7%, and 4.7–42.4%, respectively. In terms of ESV composition, agricultural product supply contributed the largest proportion (40.3–53.7%), followed by nutrient accumulation (16.9–24.4%) and climate regulation services (17.8–20.2%) (Figure 6b). In summary, soil amendments, particularly BC, can effectively enhance the total ESV in saline–alkali farmland by synergistically improving the value of agricultural product supply, soil nutrient accumulation, and climate regulation services.

Table 3.

Values of climate regulation services under different treatments in 2017–2019.

Figure 6.

Total ecosystem service value (a) and the proportional contributions of its components (b). Note: Error bars represent standard error of means (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). CK, RT, PL, BC, DG and DGO represent the treatments without any amendment, straw return with rotary tillage, straw return with plowing, biochar, desulfurized gypsum and desulfurized gypsum combined with organic fertilizer, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Different Amendments on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Quality Index

Our study showed that all amendments significantly enhanced the SQI compared with the CK (Figure 4c), although their improvement efficiencies varied substantially. These differences mainly resulted from their distinct influences on soil compaction status (as reflected by BD), salinity content, and nutrient availability. Soil compaction, a fundamental determinant of SQI [45], was markedly improved by several amendments. The BC, RT, PL, and DGO treatments significantly reduced soil BD and increased total porosity. Notably, the BC treatment showed the most pronounced and sustained improvement through to the third year, indicating its superior and long-term capacity for mitigating soil compaction under identical cropping conditions. This superior performance can be attributed to biochar’s highly porous structure and stable carbon skeleton, which form a persistent pore network resistant to compaction, thereby creating conditions conducive to improved water infiltration and root growth [46,47]. Furthermore, its abundance of surface functional groups (e.g., carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl) promotes soil aggregation through ion exchange and complexation, further optimizing pore connectivity [48]. The significant increase in SOM under the BC treatment also contributed to aggregate stabilization via physical entanglement of organic polymers and fungal hyphae [49]. In contrast, the application of DG alone did not significantly increase SOM, resulting in limited alleviation of compaction. This highlights that chemical amendments without organic matter input are insufficient for the long-term physical restoration of saline–alkali soils.

In addition to physical properties, chemical properties, particularly soil salinity, are also critical for improving soil quality [50]. The elevated salt concentrations in saline–alkali soils are primarily attributed to Na+, while their alkalinity is governed by HCO3− and CO32− [51]. All treatments reduced soil HCO3−, Na+, and EC relative to the CK, with BC, DG, and DGO showing particularly prominent desalination effects. The DG treatment supplied substantial amounts of Ca2+ and SO42−, promoting the exchange of Na+ from soil colloids, thereby reducing salinity. In the DGO treatment, the decomposition of organic fertilizer releases humic substances rich in functional groups and low-molecular-weight organic acids [52]. The humic substances increase the soil’s cation exchange capacity through their functional groups, while the organic acids significantly enhance the activity and mobility of Ca2+ ions in the soil solution via complexation [53]. Consequently, a synergistic effect occurs between the Ca2+ directly supplied by gypsum dissolution and the Ca2+ activated through organic acid complexation, enabling Ca2+ to more effectively displace exchangeable Na+ ions on soil colloids [54]. The displaced Na+ is subsequently leached by irrigation and rainfall, thereby significantly reducing the soil salt content. In BC-amended soils, biochar addition reduces soil water evaporation, thereby limiting the upward movement of salts to the topsoil. Its porous structure improves soil aeration and permeability, alleviates compaction, and promotes water infiltration and salt leaching [55]. Simultaneously, this porous structure provides adsorption capacity, enabling biochar to adsorb soluble salts such as Na+ from the soil solution, thereby reducing soil EC [56].

Improvements in soil BD and salinity conditions provided favorable environments for enhancing nutrient availability. The optimized physical conditions supported root proliferation and microbial activity, accelerating the mineralization and transformation of soil nutrients [57]. The BC treatment significantly increased AN and AP. This was achieved not only by acting as an adsorbent and slow-release source for NH4+-N and phosphate, but also by providing a habitat that supports microbial activity, thereby augmenting N availability through enhanced nitrification and biological fixation [58,59]. The DGO treatment increased AN and AP primarily through direct nutrient inputs from organic fertilizer mineralization and improved P solubility [60]. Meanwhile, PL and RT treatments showed a significant increase in AK, primarily because potassium in plant residues exists predominantly in soluble ionic forms that are rapidly released upon decomposition, providing a direct and readily available input to the soil exchangeable K+ pool [61].

Overall, the improvement of these key physicochemical properties directly and positively impacted the integrated soil quality, as reflected in the SQI (Figure 4). Among all treatments, BC treatment consistently outperformed others by simultaneously improving soil BD, reducing salinity, and enhancing nutrient availability, resulting in the highest SQI. Therefore, biochar is proven to be the most effective amendment in this study, offering a multifunctional solution to the combined physical, chemical, and nutritional constraints of saline–alkali soils. The DGO treatment also showed considerable potential for improving soil quality. However, its application requires caution due to possible heavy metal inputs associated with desulfurized gypsum. Although some studies reported no heavy metal accumulation after multiple years of application [62], others observed slight increases in heavy metals in crop tissues [63]. Therefore, while DGO demonstrates clear short-term benefits, its long-term impacts on soil and crop safety require continuous monitoring and further validation through extended field trials.

4.2. Effect of Different Amendments on Sunflower N Uptake, Yield, and Partial N Productivity

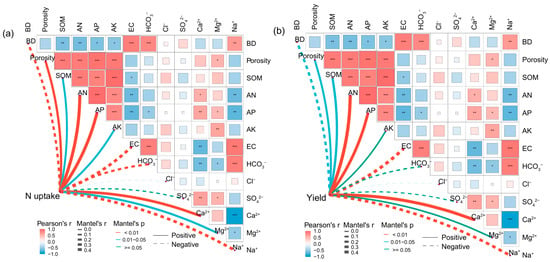

Saline–alkali stress severely constrains crop root growth and limits N uptake and yield by increasing soil osmotic pressure, disrupting soil structure, and reducing nutrient availability [64,65]. In this study, all soil amendments improved sunflower N uptake, yield, and PNP to varying degrees, with BC and DGO treatments showing the most pronounced effects. The superior performance of BC and DGO can be directly linked to their comprehensive amelioration of soil physicochemical properties, as reflected in the enhanced SQI. The significant positive correlation between SQI and both crop N uptake and yield (Figure 5) suggests that integrated soil quality improvement, rather than the modification of any single limiting factor, is the fundamental driver for boosting productivity and N use efficiency in saline–alkali soils. This holistic improvement is critical because constraints in saline–alkali soils are often interconnected. Correlation analysis further revealed that both crop N uptake and yield were significantly negatively correlated with soil BD and EC (Figure 7). This supports the conclusion that elevated soil BD and salinity act synergistically to inhibit root growth and function, ultimately constraining water and nutrient acquisition [66]. The BC and DGO treatments effectively alleviated these constraints by reducing soil BD and increasing porosity, which in turn lowered the mechanical resistance to root penetration and improved soil aeration and water-holding capacity. As a result, root systems were able to explore a larger soil volume, improving plant access to water and nutrients [67]. Meanwhile, the BC and DGO treatments also significantly reduced rhizosphere concentrations of phytotoxic ions (e.g., Na+, Cl−, and HCO3−) and EC. Mitigating this ionic and osmotic stress enabled plants to reallocate metabolic resources from costly stress tolerance mechanisms (e.g., osmotic adjustment, ion exclusion) toward growth and developmental processes, including N assimilation and translocation. This physiological shift provided the essential foundation for observed improvements in N uptake and yield formation [68,69].

Figure 7.

Correlation and Mantel test results between environmental factors and N uptake (a) and crop yield (b). Note: Red lines indicate highly significant correlations (p < 0.01), blue lines indicate significant correlations (p < 0.05), and green lines indicate non-significant correlations (p > 0.05). Solid lines represent positive correlations, dashed lines represent negative correlations, and line thickness reflects the strength of the Mantel test correlation. * Substantial at the 0.05 probability level, ** substantial at the 0.01 probability level, *** substantial at the 0.001 probability level. BD, SOM, AN, AP, AK, and EC represent bulk density, soil organic matter, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, and electrical conductivity, respectively.

In addition to alleviating physical and salinity constraints, the enhancements in nutrient availability and SOM accumulation played a pivotal role in enhancing crop productivity. SOM and available nutrient contents were significantly positively correlated with crop N uptake and yield (Figure 7). The BC and DGO treatments substantially increased SOM, AN, AP, and AK, providing continuous and stable nutrient support for crop growth. This not only directly promoted N uptake and grain filling but also optimized the carbon–N metabolism, improving the efficiency with which photosynthetic products were translocated to grains, thereby elevating overall N use efficiency [70]. Furthermore, SOM accumulation enhances the soil’s buffering capacity and resilience against salinity fluctuations, helping to maintain higher N availability and sustained crop physiological activity over successive growing seasons [71].

In contrast, while RT and PL improved SOM and available nutrients, they were less effective at promoting salt leaching and removing harmful ions. Moreover, the decomposition of high C:N ratio straw can induce transient soil N immobilization, potentially restricting the timely supply of plant-available N. These factors likely contributed to their relatively weaker and less consistent effects on enhancing N uptake and yield [72]. Similarly, although the DG treatment stimulated initial crop growth by reducing exchangeable Na+ via Ca2+–Na+ exchange, its benefits diminished over time. This decline occurred because DG failed to durably increase SOM or provide long-term structural and nutritional support, resulting in long-term benefits that were inferior to those of the BC and DGO treatments. These findings are consistent with previous studies that report the limited long-term efficacy of desulfurized gypsum applied alone for the sustained reclamation of saline–alkali soils [73,74].

In summary, the BC and DGO treatments improved the structural, saline, and nutrient conditions of salt-affected soils, effectively enhancing sunflower yield and N use efficiency. Among the treatments, biochar exhibited the most favorable overall performance in this study due to its high stability, multiple modes of action, and long-lasting ameliorative effects. Therefore, in the HID and similar salt-affected regions, the application of biochar can be considered the most promising amendment for achieving sustainable crop production and efficient N management.

4.3. Effect of Different Amendments on Farmland Ecosystem Service Value

The economic valuation of farmland ESV provides a systematic framework for assessing the comprehensive benefits of soil amendments in promoting ecological agriculture. The results of this study indicate that, compared to the CK, various soil amendments significantly enhanced the total farmland ESV by influencing key processes such as SOM accumulation, nutrient dynamics, and crop productivity. Notably, the value of agricultural product supply accounted for 40.3–53.7% of the total ESV, highlighting the critical role of farmland ecosystems in meeting human food demands. In the first year, the ESV for the RT, PL, and DGO treatments was slightly lower than that of CK, likely due to higher initial input costs or the time needed for the soil system to adapt and respond. However, as the effects of the improvements accumulated over the years, all the amendments significantly increased sunflower yield from 2018 to 2019. This change was mainly attributed to the reduction in soil salinity, the increase in organic matter content, and the enhancement of available nutrient levels, which significantly boosted the value of agricultural product supply. Notably, the BC treatment exhibited the most substantial yield enhancement and the greatest increase in supply value in the latter two years, highlighting its key role in enhancing sustainable agricultural output.

Regarding the value of SOM accumulation, all amendments, except DG treatment, significantly increased SOM content, thereby enhancing its ESV. This result highlights the effectiveness of organic matter-based amendment measures (i.e., BC, RT, PL, and DGO) in promoting soil carbon sequestration in saline–alkali or structurally degraded soils. Notably, the BC treatment exhibited outstanding performance in enhancing SOM accumulation, confirming previous findings that biochar contributes to the formation of a stable soil carbon pool due to its aromatic structure and longer mean residence time [75]. In terms of nutrient accumulation value, all amendments enhanced this function by increasing the stocks of AN, AP, and AK. These results indicate that farmland ecosystems not only meet human food demands by supporting crop production but also contribute to the long-term restoration of soil fertility [76].

Climate regulation is one of the key services provided by farmland ecosystems, which was significantly influenced by the amendments. The CK treatment had the lowest positive values for carbon sequestration and oxygen release, while all the amendments enhanced this function by improving soil conditions and promoting the accumulation of crop biomass. The BC treatment achieved the greatest enhancement, benefiting from its dual role as a direct, stable carbon input and a soil conditioner that improves carbon use efficiency and plant growth. Additionally, the BC treatment exhibited a suppressive effect on GHG emissions (i.e., CO2, CH4, N2O), which may be related to biochar’s improvement of soil aeration, its ability to adsorb microbial metabolic substrates, and its impact on microbial community function. These mechanisms collectively enhance the net climate regulation function of farmland [77].

In summary, the enhancement of farmland ESV comprehensively reflects the effectiveness of soil improvements. Among all strategies, BC treatment demonstrated synergistic, stable, and significant improvement, exhibiting remarkable performance in key ecological functions such as agricultural product supply, climate regulation, and the accumulation of organic matter and nutrients.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the combined effects of different amendments (RT, PL, BC, DG, DGO) on soil quality, crop productivity, and ESV in saline–alkali farmland of an arid region through a three-year field experiment. The results indicated that both BC and DGO treatments significantly improved soil quality, with the BC treatment exhibiting particularly outstanding and persistent comprehensive benefits. Specifically, the BC treatment not only optimized soil physical structure by reducing BD and increasing total porosity, but also significantly enhanced soil fertility and alleviated saline–alkali ion toxicity, resulting in the highest SQI. The improvement in SQI was closely associated with enhanced crop productivity. In the third year of amendment, the BC treatment achieved the highest sunflower N uptake, grain yield, and PNP. Furthermore, the BC treatment synergistically enhanced multiple ESV, particularly agricultural product supply, climate regulation, and SOM accumulation, resulting in the greatest increase in total farmland ESV. In summary, both BC and DGO treatments are effective amendments for the amelioration of saline–alkali soils. Notably, biochar demonstrated exceptional performance in simultaneously improving soil quality, crop productivity, and total ESV, highlighting its broad potential for practical application. These findings provide important theoretical support and practical pathways for the sustainable utilization of saline–alkali farmland and the development of ecological agriculture in arid and semi-arid regions.

Author Contributions

M.H.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. Y.L.: Writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. Y.Z.: Investigation, writing—review and editing. Z.Q.: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number: 2025M772478) and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number: GZB20250568).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahab, S.; Suhani, I.; Srivastava, V.; Chauhan, P.S.; Singh, R.P.; Prasad, V. Potential risk assessment of soil salinity to agroecosystem sustainability: Current status and management strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 144164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopmans, J.W.; Qureshi, A.S.; Kisekka, I.; Munns, R.; Grattan, S.R.; Rengasamy, P.; Ben-Gal, A.; Assouline, S.; Javaux, M.; Minhas, P.S.; et al. Critical knowledge gaps and research priorities in global soil salinity. Adv. Agron. 2021, 169, 1–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, M. Synergistic improvement of carbon sequestration and crop yield by organic material addition in saline soil: A global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, E.; El-Beshbeshy, T.; Abd El-Kader, N.; El Shal, R.; Khalafallah, N. Impacts of biochar application on soil fertility, plant nutrients uptake and maize (Zea mays L.) yield in saline sodic soil. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. The regulation of plant cell wall organisation under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Luo, J.; Park, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Masin, R. Soil salinization in agriculture: Mitigation and adaptation strategies combining nature-based solutions and bioengineering. iScience 2024, 27, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Yan, A.; Han, R.; Yao, Y.; Chang, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, L.; Meng, T. Preliminary study on the effect of microbial amendment on saline soils in a coastal reclaimed area. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 120–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Du, L.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, F.; Zhong, T.; Ren, F.; Yin, M.; Ding, L.; Liu, X. Effects of dual mulching with wheat straw and plastic film under three irrigation regimes on soil nutrients and growth of edible sunflower. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 288, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruiyot, W.K.; Zhu, S.; Indoshi, S.N.; Wang, W.; Ren, A.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Shallow-incorporated straw returning further improves rainfed maize productivity, profitability and soil carbon turnover on the basis of plastic film mulching. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, J.; Wu, G.; Huang, X.; Fan, G. Maize straw mulching with no-tillage increases fertile spike and grain yield of dryland wheat by regulating root-soil interaction and nitrogen nutrition. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 228, 105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Cowie, A.L.; Van Zwieten, L.; Bolan, N.; Budai, A.; Buss, W.; Cayuela, M.L.; Graber, E.R.; Ippolito, J.A.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. How biochar works, and when it doesn’t: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to biochar. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1731–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aborisade, M.A.; Feng, A.; Oba, B.T.; Kumar, A.; Battamo, A.Y.; Huang, M.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y.; Sun, P.; Zhao, L. Pyrolytic synthesis and performance efficacy comparison of biochar-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron on soil polluted with toxic metals. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2022, 69, 2249–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, S.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Xing, G. Successive biochar amendment improves soil productivity and aggregate microstructure of a red soil in a five-year wheat-millet rotation pot trial. Geoderma 2020, 376, 114570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, P. Potential flue gas desulfurization gypsum utilization in agriculture: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralegedara, N.H.; Pinto, P.X.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Al-Abed, S.R. Recent advances in flue gas desulfurization gypsum processes and applications—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Tian, L.; Shi, S.; Xu, S.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, C. Aggregate-related changes in soil microbial communities under different ameliorant applications in saline-sodic soils. Geoderma 2018, 329, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, B.; Murtaza, G.; Sabir, M.; Owens, G.; Abbas, G.; Imran, M.; Shah, G.M. Amelioration of saline-sodic soil with gypsum can increase yield and nitrogen use efficiency in rice-wheat cropping system. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2017, 63, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Qiao, T. The effect of fungal fertilizer and desulfurization gypsum combined application on the quality of saline-alkali soil and the yield of pacesetter. Soil Fert. Sci. China 2024, 10, 127–135. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Soil salinity: A global threat to sustainable development. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasafi, T.E.; Moukhtari, A.E.; Farissi, M.; Ziouti, A.; Prasad, M.N.V.; Oukarroum, A.; Haddioui, A. Soil amendments as promising strategies for phytomanagement of Cd contaminated soils. In Bio-Organic Amendments for Heavy Metal Remediation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Kang, Y.; Cui, G. Effects of different soil water matric potentials on growth traits and yield characteristics of sunflower (Helianthus annuus Linn.) under drip irrigation in a salinized farmland in northern China. Irrig. Sci. 2025, 43, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.; Daliakopoulos, I.N.; Del Moral, F.; Hueso, J.J.; Tsanis, I.K. A Review of Soil-Improving Cropping Systems for Soil Salinization. Agronomy 2019, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 13th ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 1–410. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, M.A.; Boersma, L. A unifying quantitative analysis of soil texture. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1984, 48, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Q.; Kuai, J.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhou, G. The effect of sowing depth and soil compaction on the growth and yield of rapeseed in rice straw returning field. Field Crops Res. 2017, 203, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, G.R.; Hartge, K.H. Bulk Density. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part I Physical and Mineralogical Methods, 2nd ed.; Klute, A., Ed.; ASA-SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1986; pp. 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Huang, G.; Sun, C.; Pereira, L.; Ramos, T.; Huang, Q.; Hao, Y. Assessing the effects of water table depth on water use, soil salinity and wheat yield: Searching for a target depth for irrigated areas in the upper Yellow River basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 125, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.; Zang, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, J. Analysis of high content water-soluble salt cation in saline-alkali soil by X-Ray fluorescence spectrometry. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40, 1467–1472. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Hu, M.; Shi, J.; Tian, X.; Wu, J. Integrated wheat-maize straw and tillage management strategies influence economic profit and carbon footprint in the Guanzhong Plain of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 145347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brealey, L. The Determination of potassium in fertilisers by flame photometry. Analyst 1951, 76, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Q.; Xu, X.; Huo, Z. Effects of irrigation and fertilization on grain yield, water and nitrogen dynamics and their use efficiency of spring wheat farmland in an arid agricultural watershed of Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoru, C.R.; Nyoni, F.C.; Borges, A.V.; Darchambeau, F.; Nyambe, I.; Bouillon, S. Spatial variability and temporal dynamics of greenhouse gas (CO2, CH4, N2O) concentrations and fluxes along the Zambezi River mainstem and major tributaries. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2014, 11, 16391–16445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.S.; Karlen, D.L.; Mitchell, J.P. A comparison of soil quality indexing methods for vegetable production systems in Northern California. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 90, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, D. Development of biological soil quality indicator system for subtropical China. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 126, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Gunina, A.; Zamanian, K.; Tian, J.; Luo, Y.; Xingliang, X.U.; Yudina, A.; Aponte, H.; Alharbi, H.; Ovsepyan, L. New approaches for evaluation of soil health, sensitivity and resistance to degradation. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Cao, W.; Huang, Y. Appraisal of Agro-ecosystem Services in Winter Green Manure-spring Maize. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2016, 25, 597–604. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Q.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P. Recycling. Achieving sustainable development goals in agricultural energy-water-food nexus system: An integrated inexact multi-objective optimization approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Q.; Huang, G. A process simulation-based framework for resource, food, and ecology trade-off by optimizing irrigation and N management. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 129035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H.; Shao, Y.; Fang, B.; Yue, J.; Lu, F.; Ma, F.; Qin, F.; Yang, C. Evaluation of ecosystem services of wheat-maize cropping system under different farming modes in the rain-fed area of southern Henan Province. Chin. J. Ecol. 2015, 34, 1270–1276. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Khushboo, D.; Subhash, B.; Sanjay, S.R.; Rishi, R.; Md, Y.; Veda, K.; Sudesh; Aastika, P.; Ananya, G.; Vipin, K.; et al. Effect of legume integration and nitrogen levels on selected ecosystem services and soil biological indicators in maize farming under humid subtropics. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2025, 91, 1512–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Costanza, R.; Sandhu, H.; Sigsgaard, L.; Wratten, S. The value of producing food, energy, and ecosystem services within an agro-ecosystem. Ambio 2009, 38, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, P. Evaluation of ecological service value of rice-wheat rotation ecosystem. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2008, 16, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhen, L.; Zhang, L. Dynamic changes in the value of China’s ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Shen, N.; Yang, M.; Li, S. Response of Soil Aggregate Stability Changes of Typical Huangmian Soil to Vegetation Succession. Soils 2025, 57, 195–203. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jia, A.; Song, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Han, Z.; Gao, H.; Gao, Q.; Zha, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Biochar enhances soil hydrological function by improving the pore structure of saline soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra-Mendoza, K.; Horn, R. Effect of biochar addition on hydraulic functions of two textural soils. Geoderma 2018, 326, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shang, J. Effects of low molecular weight organic acids on aggregation behavior of biochar colloids at acid and neutral conditions. Biochar 2022, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H. Biochar and Soil Physical Properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 687–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, I.; Hooker, D.C.; Deen, B.; Janovicek, K.; Van Eerd, L.L. Long-term effects of crop rotation, tillage, and fertilizer nitrogen on soil health indicators and crop productivity in a temperate climate. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, L. New Insight into Plant Saline-Alkali Tolerance Mechanisms and Application to Breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Liu, H.; Liu, A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, G.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Lei, M. Rhizosphere environmental factors regulated the cadmium adsorption by vermicompost: Influence of pH and low-molecular-weight organic acids. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 266, 115593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Huang, C.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, F. Effects of different amount of organic materials combined with desulfurized gypsum on soil improvement and crop yield in saline-sodic soil. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2019, 37, 34–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Xia, R.; Ying, Y.; Lu, S. Desulfurization steel slag improves the saline-sodic soil quality by replacing sodium ions and affecting soil pore structure. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, M.O.; Xin, X.; Nahayo, A.; Liu, X.; Korai, P.K.; Pan, G. Quantification of biochar effects on soil hydrological properties using meta-analysis of literature data. Geoderma 2016, 274, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Dahlawi, S.; Naeem, A.; Rengel, Z.; Naidu, R. Biochar application for the remediation of salt-affected soils: Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, Z.U.R.; Qadir, A.A.; Alserae, H.; Raza, A.; Mohy-Ud-Din, W. Organic amendment-mediated reclamation and build-up of soil microbial diversity in salt-affected soils: Fostering soil biota for shaping rhizosphere to enhance soil health and crop productivity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 109889–109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Liang, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, B.; Han, S.; Wu, M.; He, X.; Zeng, W.; He, Z.; Xiao, J.; et al. Effects of Biochar-Based Fertilizers on Fenlong-Ridging Soil Physical Properties, Nutrient Activation, Enzyme Activity, Bacterial Diversity, and Sugarcane Yield. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Shi, W.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, G. Pyrolysis temperature shapes biochar-mediated soil microbial communities and carbon-nitrogen metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1657149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Yan, Y. Application of desulfurized gypsum combined with pig manure to improve soil quality and promote crop growth in saline-alkali soils. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2025, 40, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Jiao, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, C. The Fate and Challenges of the Main Nutrients in Returned Straw: A Basic Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, L. Long-term performance of flue gas desulfurization gypsum in a large-scale application in a saline-alkali wasteland in northwest China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 261, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, J. Effect of typical takyr solonetzs reclamation with Flue flue gas desulphurization gypsum and its security assessment. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 141–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. Response Mechanisms of Plants Under Saline-Alkali Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chang, L.; Li, G.; Li, Y. Advances and future research in ecological stoichiometry under saline-alkali stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 5475–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, M. Interactive effects of pH, EC and nitrogen on yields and nutrient absorption of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 194, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammary, A.A.G.; Al-Shihmani, L.S.S.; Fernández-Gálvez, J.; Caballero-Calvo, A. A comprehensive review of impacts of soil management practices and climate adaptation strategies on soil thermal conductivity in agricultural soils. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio-Technol. 2025, 24, 513–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.H.A.; Li, B.; Zhu, X.; Song, C. Nitrogen assimilation under osmotic stress in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 94, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahanger, M.A.; Qin, C.; Begum, N.; Qi, M.; Dong, X.; El-Esawi, M.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Alatar, A.A.; Zhang, L. Nitrogen availability prevents oxidative effects of salinity on wheat growth and photosynthesis by up-regulating the antioxidants and osmolytes metabolism, and secondary metabolite accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ye, J.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; Zhong, X.; Wang, C.; Tian, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y. Optimizing Agronomy Improves Super Hybrid Rice Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency through Enhanced Post-Heading Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism. Agronomy 2023, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gu, S.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, X.; Hatano, R. Saline-Alkali Soil Reclamation Contributes to Soil Health Improvement in China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Lam, S.; Wolf, B.; Kiese, R.; Chen, D.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Trade-offs between soil carbon sequestration and reactive nitrogen losses under straw return in global agroecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 5919–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, A.; Ma, F.; Liu, J.; Xiao, G.; Xu, X. Amendment of Saline-Alkaline Soil with Flue-Gas Desulfurization Gypsum in the Yinchuan Plain, Northwest China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, G.; Wang, X.; Li, T. Gypsum and organic materials improved soil quality and crop production in saline-alkali on the loess plateau of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1434147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y. Biochar stability in soil: Meta-analysis of decomposition and priming effects. GCB Bioenergy 2016, 8, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, M.F.; Abdullah, M.A.; Rizwan, M.; Haider, G.; Ali, M.A.; Zafar-Ul-Hye, M.; Abid, M. Different nitrogen and biochar sources’ application in an alkaline calcareous soil improved the maize yield and soil nitrogen retention. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, N.; Huang, M.; Ye, X. Combined metabolomic and microbial community analyses reveal that biochar and organic manure alter soil C-N metabolism and greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Int. 2024, 192, 109028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.