Abstract

Soil-borne pathogens significantly threaten crop production and global food security, while green and efficient antipathogenic materials are scarce. In this study, green and efficient Ag/AgCl nanoparticles (Ag/AgCl-NPs) were developed using an aqueous extract of ginger-straw waste as the raw material. The synthesized Ag/AgCl-NPs exhibited a spherical morphology with an average size of approximately 40 nm, good crystal structure, and abundant surface groups. Additionally, they exhibited excellent antimicrobial activity against representative soil-borne pathogens, including Ralstonia solanacearum (MIC = 20 μg/mL; MBC = 40 μg/mL) and Fusarium oxysporum (spore MIC = 20 μg/mL; mycelial EC50 = 64.596 μg/mL). The antimicrobial mechanism was attributed to cell membrane disruption and oxidative stress induction. This study provides an excellent antimicrobial agent for controlling crop soil-borne pathogens.

1. Introduction

Crop diseases pose a critical threat to global food security and the sustainability of agricultural systems. Globally, diseases caused by fungal, bacterial, and viral pathogens result in substantial annual yield losses and severe economic damage [1]. Among them, soil-borne diseases have emerged as a major challenge in crop production owing to their persistent latency, complex transmission routes, and control difficulties [2]. Ralstonia solanacearum (R. solanacearum) and Fusarium oxysporum (F. oxysporum) are representative soil-borne bacterial and fungal pathogens, respectively [3]. R. solanacearum has a broad host range and infects more than 200 economically important crops, such as tomato, potato, and ginger [4,5,6]. It induces rapid wilting and crop death by colonizing and obstructing vascular tissues, which typically results in rapid disease spread and widespread field failures. Similarly, F. oxysporum infects various crops, including banana, watermelon, and ginger, and causes wilting and chlorosis through phytotoxin production and vascular occlusion, thus resulting in persistent and severe disease progression [7].

Fungicide application remains one of the most effective approaches for controlling R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum, which significantly reduces disease incidence in agricultural systems [8]. In particular, chemical fungicides, including carbendazim, prochloraz, streptomycin, oxytetracycline, prothioconazole, and thiophanate-methyl, have demonstrated efficacy against R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum in disease-control systems for crops such as tomato, ginger, and watermelon [9,10,11]. Although these agents exhibit excellent initial antimicrobial activity, their action mechanisms depend primarily on single-site inhibition. Their prolonged use readily induces resistance in pathogen populations through mechanisms such as target-site mutations, overexpression of target genes, enhanced drug efflux capacity, and biofilm formation, which collectively diminish control efficacy and exacerbate disease recurrence [12]. Furthermore, approximately 90% of applied agrochemicals may enter environmental compartments through degradation, volatilization, or leaching, thus posing potential risks to the ecosystem structure and function and indirectly affecting human health [13]. Therefore, novel antimicrobial agents with sustained efficacy, low resistance risk, and high environmental compatibility must be urgently developed to facilitate green strategies in crop-disease management.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have been extensively utilized in antimicrobial and anticancer therapies, food science, cosmetics, and clinical and pharmaceutical fields owing to their highly reactive surfaces and nanoscale effects [14]. In particular, AgNPs exhibit remarkable antimicrobial activity, with a bactericidal efficacy several hundred times greater than that of conventional silver-based agents. Biosynthetic approaches have garnered increasing interest owing to their environmental friendliness, mild reaction conditions, and low cost [15,16]. Such methods have been widely investigated for the development of green bactericides, which serve as reducing and capping agents for the sustainable preparation of AgNPs [17]. Tabassum et al. successfully synthesized AgNPs using violet extract, which exhibited significant antifungal activity against F. oxysporum at 60 mg/L [18]. Vanti et al. biosynthesized AgNPs using Solanum torvum extract and demonstrated their bactericidal effects against Pseudomonas angulata and R. solanacearum in vitro [19]. However, the biosynthesized AgNPs present limitations, such as insufficient long-term stability and ease of agglomeration and oxidation, which compromise their functional performance [20]. To improve their stability, researchers have developed silver-based composite nanomaterials, such as Ag/ZnO, Ag/InS, and Ag/AgCl, which have been employed in antimicrobial assays [21,22,23]. Moreover, compared with other silver-based composites, Ag/AgCl nanoparticles (Ag/AgCl-NPs) not only retain the strong antimicrobial properties of silver ions but also enhance the photocatalytic antimicrobial activity by promoting electron–hole separation via the formation of heterojunction structures [24]. Under visible-light irradiation, these nanocomposites enable the sustained release of silver ions, thereby affording long-lasting antimicrobial efficacy [25]. Hassan et al. synthesized Ag/AgCl-NPs with an average size of 16.99 ± 0.3 nm using Chara algae extract and demonstrated their efficacy against clinically isolated pathogenic bacteria [26]. Thirubuvanesvari-Duraivelu et al. synthesized MdSE-Ag/AgCl-NPs using Medjool-date seed extract, which showed significant antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [27]. Nevertheless, despite increasing investigations into the plant extract-mediated biosynthesis of Ag/AgCl-NPs for antimicrobial applications, studies regarding their effectiveness against crop pathogenic microorganisms and their underlying mechanisms of action remain primarily unexplored.

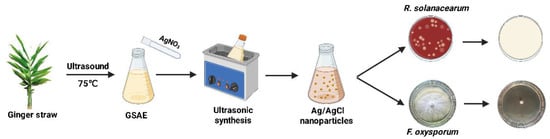

Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) is an important medicinal and edible plant rich in diverse bioactive phytochemicals [28]. Recently, ginger rhizome extracts have been employed as reducing agents for the synthesis of various nanomaterials, including AgNPs, SnO2, and ZnO [29,30,31]. However, their direct application in nanomaterial synthesis presents challenges of low resource utilization and unsatisfactory economic viability. By contrast, ginger straw—a major byproduct of ginger production—is typically discarded in large quantities, thus resulting in environmental concerns [32]. Notably, ginger straw contains abundant reducing components [33], which indicates its potential as both a reducing agent and stabilizer for the synthesis of Ag-based NPs. In this study, Ag/AgCl-NPs were synthesized via an ultrasonication-assisted method using ginger-straw aqueous extract (GSAE), and their inhibitory effects and underlying mechanisms against R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum were systematically investigated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the synthesis and antimicrobial application of Ag/AgCl-NPs against soil-borne pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

Ginger straw was obtained from a ginger cultivation base in Chongqing, China. F. oxysporum (PX705825) and R. solanacearum (MN830162.1) were provided by Yangtze University (Jingzhou, China). Phosphate buffer solution and silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.8%) were purchased from Chengdu Chron Chemical Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 99.8%) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99.8%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Meanwhile, 2, 3, 5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, 98%) was obtained from Shanghai Acmec Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay kit, potato dextrose agar (PDA), and potato dextrose broth (PDB) medium were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Casamino acid–peptone–glucose (CPG) medium was obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Catalase (CAT) and malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kits were purchased from Suzhou Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). A reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection kit was acquired from Biyuntime Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Preparation of Ag/AgCl-NPs

Briefly, 30 g of ginger-straw powder was added to 500 mL of distilled water and then extracted via ultrasound at 75 °C for 60 min. Next, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to obtain GSAE. Subsequently, 20 mL of the GSAE was added to 180 mL of AgNO3 solution at different concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM). The system was reacted in an ultrasonic instrument (SN-QS-150D, ES SENS, Shanghai, China) under various pH (3, 5, 7, 9, and 11, adjusted by 0.1 mol/L HCl and NaOH) and different reaction temperatures (25 °C, 35 °C, 45 °C, 55 °C, and 65 °C) for different reaction times (20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 min). Once the reaction had completed, Ag/AgCl-NPs were obtained via centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 10 min), after which they were washed and freeze-dried.

2.3. Characterization of Ag/AgCl-NPs

The optical properties of the Ag/AgCl-NPs were analyzed using an ultraviolet–visible (UV-vis) spectrophotometer (TU-1900, Persee, Beijing China). The morphology was examined using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, SU-4800, Hitachi, Japan). The crystallographic structure was characterized via high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, Tecnai G2 F20, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA), and the lattice spacings observed in the HRTEM micrographs were measured using the Gatan Digital Micrograph software 3.9.1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker Corporation, Karlsruhe, Germany) with a 2θ range of 20–80°, with phase identification performed by matching the diffraction profiles with standard PDF cards. The surface functional groups were detected using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The zeta potential was assessed via zeta potential measurements using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK).

2.4. Antimicrobial-Activity Assay

The antimicrobial activity of the Ag/AgCl-NPs against R. solanacearum was evaluated using the standard disc diffusion assay and broth-microdilution method. The discs containing different concentrations of Ag/AgCl-NPs (0–320 μg/mL) were placed onto the agar surface. Inoculated plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h, and the inhibition zones were observed. Furthermore, a series of two-fold serial dilutions of the Ag/AgCl-NPs was prepared in CPG medium supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) TTC. A bacterial suspension was introduced into each well to achieve a final concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL. After 48 h of incubation at 30 °C, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of Ag/AgCl-NPs that prevented the appearance of red color. Meanwhile, the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined by inoculating samples from wells with Ag/AgCl-NP concentrations at or above the MIC onto a solid CPG medium supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) TTC and 1.5% agar. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration at which no red coloration developed on the medium surface. The antifungal activity of the Ag/AgCl-NPs against F. oxysporum was evaluated using spore inhibition assays and via mycelial growth studies. The spore suspensions were adjusted to final concentrations of 1 × 106 spores/mL in a 96-well plate containing two-fold serially diluted Ag/AgCl-NPs. After incubation at 28 °C for 48 h, the turbidity of each well was examined visually to determine the inhibitory effect of the Ag/AgCl-NPs on spore germination. The mycelial growth rate method, cross-hatch technique, and median effective concentration (EC50) analysis were employed to further investigate the antifungal activity of Ag/AgCl-NPs against F. oxysporum mycelia [34]. Fungal cakes (5 mm in diameter) retrieved from actively growing margins were placed upside down at the center of PDA plates amended with Ag/AgCl-NPs at concentrations of 0, 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 μg/mL. The colony diameters were measured every 24 h for 5 d along two perpendicular axes using the cross-hatch method. The mycelial growth inhibition rate was calculated as follows:

where D denotes the colony growth diameter, D1 is the colony diameter, D2 is the cake’s colony diameter, I is the mycelial growth inhibition rate, D0 is the blank control’s colony growth diameter, and Dt is the colony growth diameter following treatment with Ag/AgCl-NPs.

Control experiments were performed to exclude the individual effects of the GSAE (0.6 g/mL) and AgNO3 (2 mM). The commercial fungicide carbendazim (CBZ, 20 μg/mL) was also used as a reference for efficacy evaluation. A control group was set up containing the same composition but not inoculated.

2.5. Leakage of Cell Contents

The R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum were treated with Ag/AgCl-NPs at concentrations of 0, 10, and 20 μg/mL for 0, 1, 2, and 3 h, respectively, and the samples were centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) and observed by FE-SEM. Meanwhile, the resulting supernatant was retrieved and analyzed via UV-vis spectroscopy at a wavelength of 260 nm to determine the nucleic-acid leakage, which serves as an indicator of membrane integrity loss. The 1 mL sample was centrifuged at 8000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min. After the supernatant was discarded, the precipitate was resuspended in the extraction buffer, and the cells were broken. Subsequently, the homogenate was centrifuged at 8000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected as the test sample to determine the content of MDA and the activities of SOD and CAT. The MDA content was determined by the TBA method [35]. The absorbance was measured at 532 nm (characteristic absorption) and 600 nm (turbidity correction) using a multifunctional microplate reader (SpectraMax ID3; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, California, USA). The MDA content was calculated using the following formula:

Here, V0 denotes the total volume of the reaction system, 4 × 10−4 L; ε is the molar extinction coefficient of malondialdehyde, 1.55 × 106 L/mol/cm; d is the light path of the cuvette, 0.5 cm; V1 represents the volume of the sample aliquot added, 0.1 mL; and V2 corresponds to the volume of the extraction buffer added, 1 mL.

2.6. Determination of Intracellular ROS and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum were treated with varying concentrations (0, 10, and 20 μg/mL) of Ag/AgCl-NPs, and their intracellular ROS levels were determined via the following experimental procedures [35,36]. The bacterial suspensions were adjusted to concentrations of 1 × 107 cells/mL. The DCFH-DA fluorescent probe was added to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L, and the mixture was incubated at optimum growth temperature for 20 min. To remove excess probe, the cells were washed thrice with a serum-free cell culture medium. Rosup was used as a positive control. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 525 nm, respectively, to determine the intracellular ROS levels. SOD activity was determined by the NBT photoreduction method, with absorbance monitored at 560 nm [37]. One unit of enzyme activity (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme required to achieve 50% inhibition of NBT photochemical reduction. The CAT activity was determined using the ammonium molybdate colorimetric method by monitoring the absorbance at 405 nm, where U was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the decomposition of 1 μmol of H2O2 per minute per gram of sample mass [37].

where Alight represents the absorbance of the light-control well, Atest is the absorbance of the test well, V is the total volume of the sample solution (mL), VT is the volume of the sample used in the measurement (mL), W is the fresh weight of the sample (g), ACK is the absorbance of the control well, AEG is the absorbance of the test well, and W is the sample quality.

2.7. Data Analysis

Excel 2003 and SPSS 27.0 software were used for statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison among multiple groups, and Duncan’s multiple range test was used for post hoc multiple comparison (α = 0.05). In order to evaluate the dose–response, the inhibition rate of mycelial growth was regressed with the logarithm of Ag/AgCl-NP concentration (log10) by Probit analysis, and the toxicity was analyzed. The Probit regression equation, EC50, and model fitting statistics were derived from the model.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation Parameters of Ag/AgCl-NPs

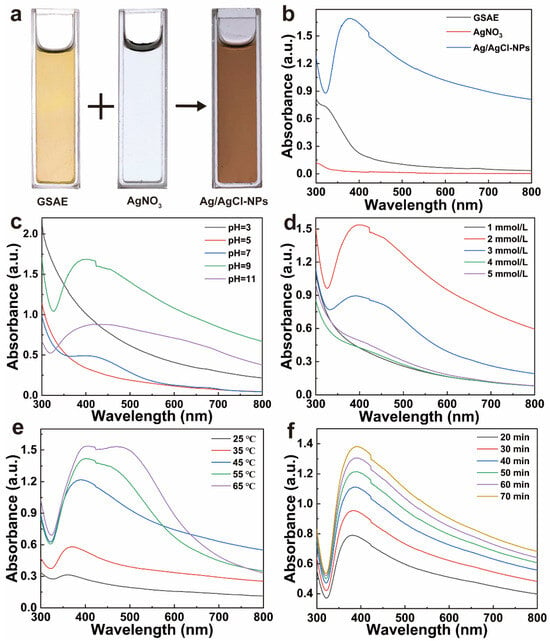

In this study, Ag/AgCl-NPs were synthesized via an ultrasonication-assisted method by reacting GSAE with AgNO3 aqueous solution. A visible color transition from faint yellow to dark brown was observed during the reaction (Figure 2a), thus indicating the consumption of silver ions and the successful formation of Ag/AgCl-NPs. This color change is typically attributed to the excitation of surface plasmon resonance in metallic NPs [17]. UV-vis spectroscopy was employed to monitor the formation of Ag/AgCl-NPs. As shown in Figure 2b, neither the GSAE nor the AgNO3 aqueous solution exhibited characteristic absorption peaks across the scanned wavelength range. By contrast, the Ag/AgCl-NPs showed a distinct absorption peak at approximately 380 nm, thus indicating the successful synthesis of Ag/AgCl-NPs [38].

Figure 2.

(a) The images and (b) UV-vis absorption spectra of GSAE, AgNO3 aqueous solution, and Ag/AgCl-NPs. UV-vis absorption spectra of Ag/AgCl-NPs synthesized under varying conditions: (c) pH, (d) AgNO3 concentration, (e) reaction temperature, and (f) reaction time.

The effects of key synthesis parameters, including pH, AgNO3 concentration, reaction temperature, and reaction time, on the formation of Ag/AgCl-NPs were systematically investigated using UV-vis spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 2c, under acidic conditions, no characteristic absorption peaks were observed, thus indicating ineffective NP formation. When the pH increased from 7 to 11, an absorption peak appeared, while the intensity initially increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum at pH 9. One can infer that neutral to weakly alkaline conditions are more favorable for the synthesis of Ag/AgCl-NPs. A blue shift in the absorption peak at pH 9 suggests the formation of smaller particles, whereas excessively alkaline conditions compromise the colloidal stability and induce particle aggregation [39]. As illustrated in Figure 2d, the absorbance of the Ag/AgCl-NPs first increased and then decreased with increasing AgNO3 concentration, with a maximum reached at 2 mmol/L. This indicates that a moderate Ag+ concentration can promote silver nucleation and growth, while excessively high concentrations induce particle agglomeration, which results in a slight red shift, thereby reflecting an increase in particle size [40]. Increasing the temperature significantly enhanced the yield of Ag/AgCl-NPs (Figure 2e), as reflected by the continuous increase in the absorption intensity. However, a concomitant red shift indicates a gradual increase in particle size. When the temperature exceeded 45 °C, dual absorption peaks emerged near 420 and 450 nm, thus suggesting a broader size distribution, increased heterogeneity, and severe aggregation [41]. The absorption intensity of the Ag/AgCl-NPs increased consistently as the reaction progressed (Figure 2f), thus indicating continuous NP formation. Within 40 min, the reaction proceeded rapidly owing to the abundance of precursors, whereas the growth rate plateaued after 60 min. Similarly, a gradual red shift was observed over time, thus suggesting that extended ultrasonication may promote particle aggregation and size increase [42]. The optimal synthesis conditions for Ag/AgCl-NPs were as follows: pH 9; AgNO3 concentration, 2 mmol/L; reaction temperature, 45 °C; and reaction time, 60 min.

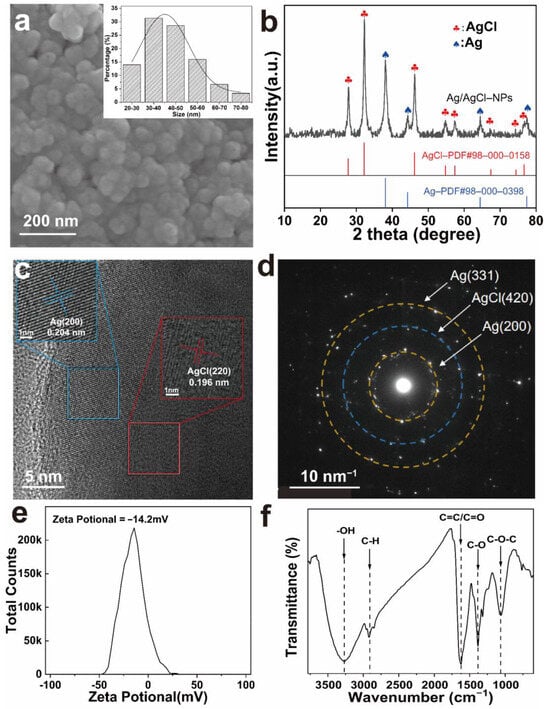

3.2. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Ag/AgCl-NPs

FE-SEM images show that the prepared Ag/AgCl-NPs exhibited an almost spherical morphology with favorable dispersibility and a relatively uniform size distribution (Figure 3a). The diameters of the Ag/AgCl-NPs ranged from 20 to 80 nm, with an average particle size of 40 nm. Previous studies demonstrated that Ag-based NPs exhibit enhanced antimicrobial activity, as their reduced particle size facilitates cellular internalization, while their increased specific surface area provides more active sites for interaction with pathogenic microorganisms [43]. Therefore, the as-prepared Ag/AgCl-NPs are expected to exhibit superior antimicrobial performance. The crystal structure of the Ag/AgCl-NPs was characterized via XRD (Figure 3b). The pattern obtained over the 2θ range of 20–80° showed distinct diffraction peaks at 27.84°, 32.24°, 46.18°, 54.83°, 57.34°, and 74.78°, which corresponded to the (111), (200), (220), (311), (222), and (420) crystal planes of AgCl (PDF: 98-000-0158), respectively [27]. The chloride source of AgCl was likely derived from GSAE, which was similar to other reports [17,23]. The additional diffraction peaks observed at 38.07°, 44.32°, 64.47°, and 77.44° were assigned to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) planes of metallic Ag (PDF: 98-000-0398), respectively [27]. These diffraction features confirmed the coexistence of Ag and AgCl phases exhibiting face-centered cubic crystal structures, which is consistent with a previous report [23]. Notably, the significantly higher diffraction intensity of the AgCl peaks compared with that of Ag suggests that AgCl dominated the composite material. Furthermore, the HRTEM image (Figure 3c) revealed clearly resolved lattice fringes with distinct grain orientations in the Ag/AgCl-NPs. The blue region corresponded to the (200) crystal plane of metallic Ag with an interplanar spacing of 0.204 nm, whereas the red region corresponded to the (220) plane of AgCl, with a d-spacing of 0.196 nm [44]. The SAED pattern (Figure 3d) shows concentric rings composed of discrete diffraction spots, thus confirming the polycrystalline nature of the Ag/AgCl-NPs. These diffraction rings were indexed to the (200) and (311) planes of Ag, along with the (420) plane of AgCl [45]. Collectively, the complementary evidence obtained from the FE-SEM, XRD, HRTEM, and SAED analyses consistently verified the successful formation of Ag/AgCl-NPs.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM image and particle size distribution; (b) XRD pattern; (c) HR-TEM image; (d) SAED pattern; (e) Zeta potential plot; (f) FTIR spectrum of Ag/AgCl-NPs.

The zeta potential value of −14.2 mV indicated that the Ag/AgCl-NPs were negatively charged owing to the presence of negatively charged surface groups derived from ginger straw adsorbed on the Ag/AgCl-NP surface (Figure 3e). The electrostatic repulsion resulting from these surface charges may contribute to maintaining colloidal stability and preventing particle aggregation [27]. FTIR spectroscopy was employed to investigate the surface groups of the Ag/AgCl-NPs (Figure 3f). The broad absorption at 3268 cm−1 was attributed to O-H stretching vibrations—indicative of alcohols and polyphenols [46]. The weak band at 2917 cm−1 corresponded to C-H stretching vibrations, which had likely originated from polysaccharides in the extract [47]. The prominent peaks at 1625 and 1384 cm−1 were assigned to aromatic C=C/C=O and C-O stretching vibrations, respectively [48,49]. The carbonyl stretching vibration, which is commonly associated with biomolecules involved in metal-ion reduction and the prevention of NP aggregation, may originate from ketones, aldehydes, carboxylic acids, or amide bonds in proteins [48]. The absorption at 1062 cm−1 is ascribed to C-O-C/C-O stretching vibrations [50]. The FTIR spectroscopy results confirmed the formation of a stable protective coating on the Ag/AgCl-NPs composed of biomolecules from GSAE. These biomolecules not only serve as reducing agents for the conversion of Ag+ to Ag0 but also provide effective steric stabilization to the NPs through their abundant functional groups [43].

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity of Ag/AgCl-NPs

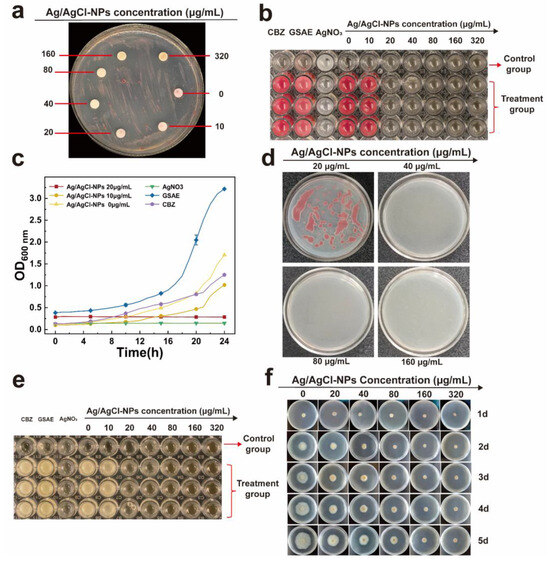

As shown in Figure 4a–c, Ag/AgCl-NPs exhibited concentration-dependent antimicrobial activity against R. solanacearum. A clear inhibitory effect was observed at the concentrations above 20 μg/mL of Ag/AgCl-NPs (Figure 4a), with diameters increasing from 14.16 ± 0.76 mm (40 μg/mL) to 20.44 ± 1.16 mm (320 μg/mL). As the Ag/AgCl-NP concentration decreased, the turbidity of the culture medium increased progressively, along with a corresponding enhancement in the color red due to TTC reduction (Figure 4b) [51]. The MIC was defined as the lowest sample concentration yielding a clear medium without TTC-derived coloration, which was determined to be 20 μg/mL. As shown in Figure 4c, the growth of R. solanacearum was significantly inhibited by Ag/AgCl-NPs in a concentration-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 4b,c, 2 mM AgNO3 could inhibit the growth of R. solanacearum, while 0.6 g/mL GSAE and 20 µg/mL CBZ could not inhibit the growth of R. solanacearum. To further evaluate bactericidal activity, samples from all nonturbid and TTC-unstained wells were placed on fresh agar plates and incubated. The MBC was identified as the lowest sample concentration that resulted in no bacterial growth on the agar plates, which was measured to be 40 μg/mL (Figure 4d). These results indicate that the Ag/AgCl-NPs not only exerted strong bacteriostatic activity against R. solanacearum (MIC = 20 μg/mL) but also achieved a bactericidal effect at 40 μg/mL.

Figure 4.

(a) Inhibition zone, (b) MIC, (c) growth curve, and (d) MBC of Ag/AgCl-NPs against R. solanacearum. Inhibition of (e) F. oxysporum spore and (f) mycelial growth by Ag/AgCl-NPs at different concentrations (n = 3, mean ± SD).

The MIC for spore germination of F. oxysporum was determined to be 20 μg/mL, based on a visual assessment of turbidity treated by Ag/AgCl-NPs (Figure 4e). Consistent with the observation of R. solanacearum, only AgNO3 treatment remained clear, whereas GSEA and CBZ showed turbidity, indicating that there was no inhibitory effect on spore germination at the test concentration. Moreover, investigations into solid media showed a concentration-dependent inhibition of mycelial growth by Ag/AgCl-NPs (Figure 4f). Whereas the control group exhibited continuous mycelial expansion throughout the incubation period, treatments with increasing concentrations of Ag/AgCl-NPs showed progressively stronger suppression of fungal growth. The inhibition of mycelial growth was statistically significant (p < 0.05) and showed a clear dose–response relationship. Furthermore, quantitative analysis revealed significant differences in colony diameter between the treatment and control groups (Table 1). After 5 d of incubation, Ag/AgCl-NPs at concentrations of 20–40 μg/mL inhibited mycelial growth by 28.56 ± 0.79% to 37.78 ± 2.95%. When the concentration was increased to 80–320 μg/mL, the inhibition rates increased significantly to 56.87 ± 3.45%–75.00 ± 0.70%. These results show that the antifungal activity of Ag/AgCl-NPs increased significantly with concentration in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, at the highest concentration tested (320 μg/mL), the inhibition rate reached 75.00 ± 0.70%, thus approaching the saturation effect (p < 0.05). In summary, Ag/AgCl-NPs showed strong, broad-spectrum antibacterial activity in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with commercial fungicides, Ag/AgCl-NPs showed more excellent antibacterial properties at the same concentration, indicating their potential commercial value.

Table 1.

Antifungal activity of Ag/AgCl-NPs against F. oxysporum.

3.4. Antimicrobial Mechanism of Ag/AgCl-NPs

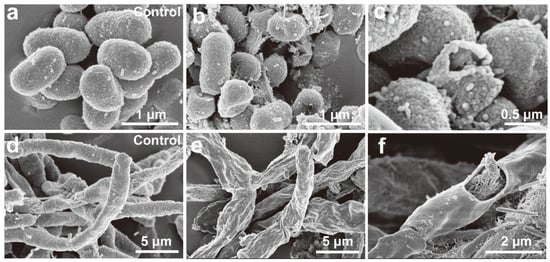

FE-SEM was used to directly assess the structural changes in R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum after Ag/AgCl-NP treatment. As shown in Figure 5a, untreated R. solanacearum cells exhibited a plump, smooth morphology. In contrast, Ag/AgCl NPs-treated cells (Figure 5b,c) displayed obvious surface depression and rupture. For F. oxysporum, the control mycelium (Figure 5d) showed normal, continuous, and smooth tubular structures, whereas treated mycelium (Figure 5e,f) underwent severe morphological alterations, including noticeable shrinkage, deformation, and fragmentation. The FE-SEM results indicated that Ag/AgCl NPs compromise cell membrane integrity, leading to the leakage of cellular contents.

Figure 5.

FE-SEM images of control and Ag/AgCl-NP-treated samples of R. solanacearum (a–c) and F. oxysporum (d–f).

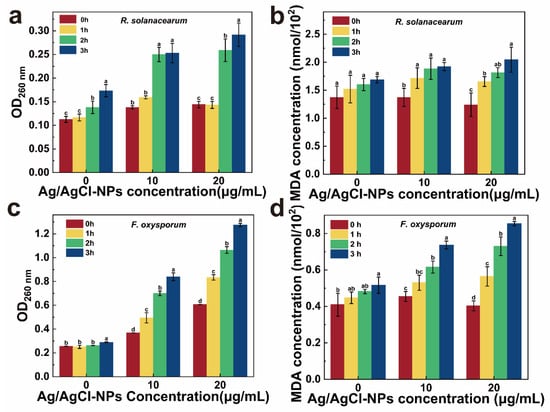

Furthermore, the cell membrane damage induced by Ag/AgCl-NPs was evaluated by the extracellular nucleic acid release (OD260) and MDA levels. As a key end-product of lipid peroxidation, MDA not only serves as a reliable indicator of oxidative damage but also actively exacerbates membrane disruption [52]. As shown in Figure 6a–d, both the OD260 and MDA levels in R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum treated with Ag/AgCl-NPs increased significantly over the 0–3 h period compared with those of the control, thus demonstrating a clear positive correlation with both the treatment concentration and duration. These results indicate that exposure to Ag/AgCl-NPs induces substantial lipid peroxidation in microbial cells, thus causing the loss of membrane integrity, leakage of intracellular components, and consequent disruption of normal physiological functions [53].

Figure 6.

Nucleic acid and MDA contents of (a,b) R solanacearum and (c,d) F oxysporum with treatment of different Ag/AgCl-NP concentrations (0, 10, and 20 µg/mL) (n = 3, mean ± SD; letters a–d denote statistically significant differences, p < 0.05).

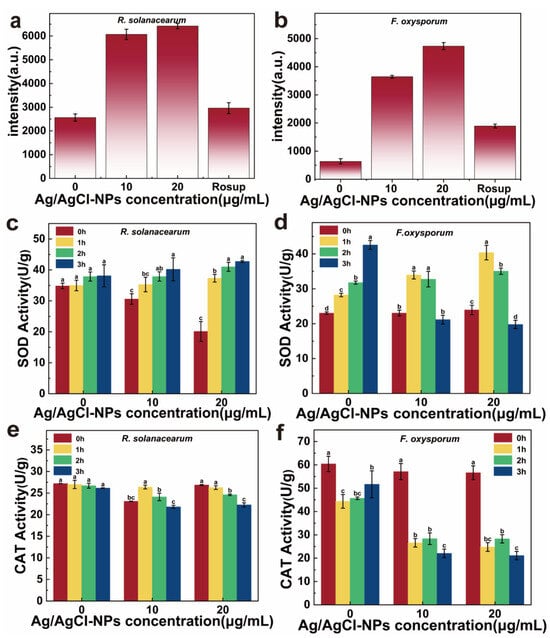

To further investigate the mechanism of cellular damage induced by Ag/AgCl-NPs, intracellular ROS level, SOD, and CAT activities were monitored. As shown in Figure 7a,b, the dose-dependent increase in intracellular ROS increased with Ag/AgCl-NP concentration, demonstrating the stress produced in the microbial cell and under Ag/AgCl-NP treatment. As key antioxidant enzymes, SOD and CAT are key in scavenging free radicals, interrupting radical chain reactions, and maintaining cellular redox homeostasis [37,54]. In R. solanacearum, the SOD activity remained stable in the control group (0 μg/mL) over the 90 min incubation period, whereas the treated groups exhibited significant upregulation (Figure 7c). Under 20 μg/mL of Ag/AgCl-NPs, the SOD activity increased approximately twofold within 1 h and plateaued during the subsequent 2 to 3 h, before finally reaching a level comparable to that of the 10 μg/mL group. These results indicate a pronounced SOD response triggered by Ag/AgCl-NP-induced oxidative stress. By contrast, the CAT activity displayed differential behavior: at 10 μg/mL, the activity initially increased and then declined, whereas at 20 μg/mL, it was consistently suppressed (Figure 7e).

Figure 7.

Fluorescence intensity of (a) R. solanacearum and (b) F. oxysporum with treatment of different Ag/AgCl-NP concentrations (0, 10, 20 µg/mL). Rosup serves as the positive control reagent. (c,d) CAT and (e,f) SOD activities of R solanacearum and F oxysporum with treatment of different Ag/AgCl-NP concentrations (0, 10, 20 µg/mL) (n = 3, mean ± SD; letters a–d denote statistically significant differences, p < 0.05).

Compared with R. solanacearum, F. oxysporum showed a more pronounced antioxidant enzyme response. As illustrated in Figure 7d, under treatment with 10 and 20 μg/mL of Ag/AgCl-NPs, the SOD activity of F. oxysporum initially increased and subsequently decreased, whereas the CAT activity declined steadily over time (Figure 7f). These findings suggest that the antioxidant system of F. oxysporum may undergo earlier functional disruption at higher Ag/AgCl-NP concentrations, thus rendering it incapable of effectively counteracting the progressively intensifying oxidative stress. As a Gram-negative bacterium, R. solanacearum possesses a dense double-layered cell wall composed of a peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane. The outer membrane contains abundant porin proteins and lipopolysaccharides crosslinked by divalent cations, which may reduce Ag/AgCl-NP binding and thus attenuate their antimicrobial efficacy [55]. Furthermore, the negatively charged surface of Gram-negative bacteria, coupled with the inherent negative charge of Ag/AgCl-NPs, generates electrostatic repulsion. This interaction impedes the binding and internalization of Ag/AgCl-NPs into R. solanacearum cells [35]. These results show that Ag/AgCl-NPs induce oxidative stress by stimulating intracellular ROS generation. With prolonged exposure, the excessive accumulation of ROS exceeds the cellular antioxidant capacity, thus resulting in a significant decline in antioxidant enzymes and their eventual inactivation [37]. Consequently, the accumulation of ROS causes irreversible cellular damage.

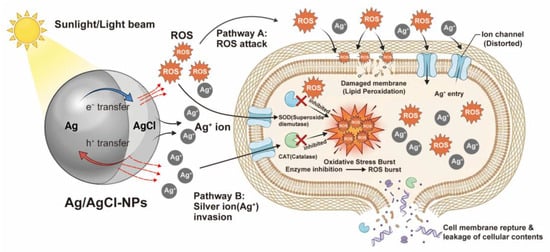

Based on the results above, a potential antimicrobial mechanism for Ag/AgCl-NPs is proposed (Figure 8). Initially, Ag/AgCl-NPs bind to bacterial cells through electrostatic interactions and continuously release silver ions [25], thereby impairing the normal physiological functions of transmembrane proteins, including channels, porins, and receptors [56]. This binding not only causes structural damage to the cell membrane but also disrupts the proton pool in the intermembrane space and impedes electron transport along the respiratory chain. The impaired electron transport promotes electron transfer to oxygen molecules, thus forming superoxide radicals [35]. These radicals react with other cellular components, thereby resulting in substantial ROS accumulation. Simultaneously, the photocatalytic activity of Ag/AgCl-NPs contributes to additional ROS generation [57]. Excessive ROS induces oxidative damage in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, thus causing oxidative destruction to the cell membrane and disrupting the cell wall integrity. Ultimately, membrane failure results in the leakage of intracellular components and cell death [53]. Therefore, the antimicrobial mechanism of the Ag/AgCl-NPs primarily involves cell membrane disruption and oxidative stress induction.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the proposed antimicrobial mechanism of Ag/AgCl-NPs.

4. Conclusions

In this work, green Ag/AgCl-NPs were prepared using ginger-straw waste as the raw material. The prepared Ag/AgCl-NPs showed excellent antibacterial activity against soil-borne pathogens, including R. solanacearum and F. oxysporum. The antimicrobial mechanism of the Ag/AgCl-NPs involved cell membrane disruption and oxidative stress induction. These findings demonstrate the potential of Ag/AgCl-NPs as a promising antimicrobial agent for preventing crop soil-borne pathogens and provide a strategy for the value-added utilization of ginger straw.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, investigation, methodology, Z.G.; Validation, data curation, Q.Z., M.L. and Y.Y.; Visualization, formal analysis, Q.L. and L.J.; Resources, conceptualization, H.L., Z.L. and K.H.; Writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, W.Z. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Graduate Research Innovation of Chongqing Project (CYS240784), Natural Science Foundation Project of Chongqing (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX1070), Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJZD-K202501301), Foundation for Chongqing Talents Program for Young Top Talents (CQYC20220510999), and Innovation Team of the Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System for Seasonings in Chongqing City (CQMAITS202510).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Strange, R.; Scott, P. Plant Disease: A Threat to Global Food Security. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Guerra, C.A.; Cano-Díaz, C.; Egidi, E.; Wang, J.-T.; Eisenhauer, N.; Singh, B.K.; Maestre, F.T. The proportion of soil-borne pathogens increases with warming at the global scale. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Thomashow, L.S.; Luo, Y.; Hu, H.; Deng, X.; Liu, H.; Shen, Z.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Resistance to bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum depends on the nutrient condition in soil and applied fertilizers: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 329, 107874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Z.; Yang, K.; Wang, J.; Jousset, A.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Friman, V.-P. Phage combination therapies for bacterial wilt disease in tomato. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, W.; Huang, M.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Meng, C.; Cheng, D.; et al. Ralstonia solanacearum type III effector RipAS associates with potato type one protein phosphatase StTOPP6 to promote bacterial wilt. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aysanew, E.; Alemayehu, D. Integrated management of ginger bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) in Southwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2022, 8, 2125033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edel-Hermann, V.; Lecomte, C. Current status of Fusarium oxysporum formae speciales and races. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbasa, W.V.; Nene, W.A.; Kapinga, F.A.; Lilai, S.A.; Tibuhwa, D.D. Characterization and chemical management of Cashew Fusarium Wilt Disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum in Tanzania. Crop Prot. 2021, 139, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, K.L.; Egel, D.S.; Langston, D.; Zhou, X.-G. Chemical management of Fusarium wilt of watermelon. Crop Prot. 2014, 66, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhou, L.; Yang, C.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Tomato Fusarium wilt and its chemical control strategies in a hydroponic system. Crop Prot. 2004, 23, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prameela, T.P.; Suseela Bhai, R. Bacterial wilt of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) incited by Ralstonia pseudosolanacearum—A review based on pathogen diversity, diagnostics and management. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; He, D.; Wang, L. Advances in Fusarium drug resistance research. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 24, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.I.; Manjula, M.; Bhavani, R.V. Agrochemicals, Environment, and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasmi, F.; Hamitouche, H.; Laribi-Habchi, H.; Benguerba, Y.; Chafai, N. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), Methods of Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Application: A Review. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 9455–9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Jadhav, N.D.; Lonikar, V.V.; Kulkarni, A.N.; Zhang, H.; Sankapal, B.R.; Ren, J.; Xu, B.B.; Pathan, H.M.; Ma, Y.; et al. An overview of green synthesized silver nanoparticles towards bioactive antibacterial, antimicrobial and antifungal applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 323, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.G.A.; Kumar, V.G.; Dhas, T.S.; Karthick, V.; Govindaraju, K.; Joselin, J.M.; Baalamurugan, J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles (biosynthesis): A short review on recent advances. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 27, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, N.; Ruhul-Amin, M.; Parvin, S.; Siddika, A.; Hasan, I.; Kabir, S.R.; Asaduzzaman, A.K.M. Green synthesis of silver/silver chloride nanoparticles derived from Elaeocarpus floribundus leaf extract and study of its anticancer potential against EAC and MCF-7 cells with antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.Z.; Mehmood, A.; Khalid, A.u.R.; Ahmad, K.S.; Rauf Khan, M.A.; Amjad, M.S.; Raffi, M.; Khan, G.-e.-l.; Mustafa, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antifungal activity against tomato fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 61, 103376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanti, G.L.; Kurjogi, M.; Basavesha, K.N.; Teradal, N.L.; Masaphy, S.; Nargund, V.B. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of solanum torvum mediated silver nanoparticle against Xxanthomonas axonopodis pv.punicae and Ralstonia solanacearum. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 309, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izak-Nau, E.; Huk, A.; Reidy, B.; Uggerud, H.; Vadset, M.; Eiden, S.; Voetz, M.; Himly, M.; Duschl, A.; Dusinska, M.; et al. Impact of storage conditions and storage time on silver nanoparticles’ physicochemical properties and implications for their biological effects. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 84172–84185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.K.; Kim, D.H. AgInS2-Coated Upconversion Nanoparticle as a Photocatalyst for Near-Infrared Light-Activated Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 1628–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Paul, D.R.; Sharma, A.; Choudhary, P.; Meena, P.; Nehra, S.P. Biogenic mediated Ag/ZnO nanocomposites for photocatalytic and antibacterial activities towards disinfection of water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 563, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-López, J.L.; Lázaro-Mass, S.; De la Rosa-García, S.; Alvarez-Lemus, M.A.; Gómez-Rivera, A.; López-González, R.; Lobato-García, C.E.; Morales-Mendoza, G.; Gómez-Cornelio, S. Medicinal Plants Extract for the Bio-Assisted Synthesis of Ag/AgCl Nanoparticles with Antibacterial Activity. J. Clust. Sci. 2024, 36, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Pan, H.; Wang, X.; Chu, P.K.; Wu, S. Photo-Inspired Antibacterial Activity and Wound Healing Acceleration by Hydrogel Embedded with Ag/Ag@AgCl/ZnO Nanostructures. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9010–9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Meng, W.; Cui, E.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Dai, Y.; et al. Photococatalytic anticancer performance of naked Ag/AgCl nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.T.; Ibraheem, I.J.; Hassan, O.M.; Obaid, A.S.; Ali, H.H.; Salih, T.A.; Kadhim, M.S. Facile green synthesis of Ag/AgCl nanoparticles derived from Chara algae extract and evaluating their antibacterial activity and synergistic effect with antibiotics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirubuvanesvari-Duraivelu, P.; Abd Gani, S.S.; Hassan, M.; Halmi, M.I.E.; Abutayeh, R.F.; Al-Najjar, M.A.A.; Abu-Odeh, A. Phytofabrication of Ag/AgCl silver nanoparticles from the extract of Phoenix dactylifera L. Medjool date seeds: Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial properties. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 27723–27737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, R.; Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Samar, N.; Shahbaz, A.; Ateeq, H.; Farooq, M.U.; Akram, N.; Asghar, A.; Rasheed, A.; et al. Bio valorization and industrial applications of ginger waste: A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 2772–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadi, M.; Azizi, M.; Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Abyadeh, M.; Milani, M. Antibacterial activity of green gold and silver nanoparticles using ginger root extract. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivarajan, Y.; Ishak, K.A.; Yaacob, J.S. Green Synthesis of Tin Oxide (SnO2) Nanoparticles Using Ginger Extracts for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes in Wastewater. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 5668–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliannezhadi, M.; Mirsanaee, S.Z.; Jamali, M.; Shariatmadar Tehrani, F. The physical properties and photocatalytic activities of green synthesized ZnO nanostructures using different ginger extract concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Wei, W. An efficient heterogeneous acid catalyst derived from waste ginger straw for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy 2021, 176, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthalaeng, N.; Gao, Y.; Remón, J.; Dugmore, T.I.J.; Ozel, M.Z.; Sulaeman, A.; Matharu, A.S. Ginger waste as a potential feedstock for a zero-waste ginger biorefinery: A review. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Hu, K.; Ou, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, X.; Liao, X.; Li, M.; Li, R. Synergistic antifungal activity and mechanism of carvacrol/citral combination against Fusarium oxysporum in Dendrobium officinale. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 215, 106671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sheng, L.; Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Ye, Y.; Geng, S.; Ning, D.; Zheng, J.; Fan, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Natural biomass-derived carbon dots as potent antimicrobial agents against multidrug-resistant bacteria and their biofilms. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 36, e00584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariona, N.; Mtz-Enriquez, A.I.; Sánchez-Rangel, D.; Carrión, G.; Paraguay-Delgado, F.; Rosas-Saito, G. Green-synthesized copper nanoparticles as a potential antifungal against plant pathogens. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18835–18843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liu, Q.; Jing, M.; Wan, J.; Huo, C.; Zong, W.; Tang, J.; Liu, R. Toxic mechanism on phenanthrene-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and activity changes of superoxide dismutase and catalase in earthworm (Eisenia foetida): A combined molecular and cellular study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 418, 126302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Meena, P.; Nehra, S.P. A rapid green synthesis of Ag/AgCl-NC photocatalyst for environmental applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 3972–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Qi, Z.; Shan, S.; Lu, K.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Tan, X. Aqueous assembly of AgNPs with camellia seed cake polyphenols and its application as a postharvest anti-Penicillium digitatum agent via increasing reactive oxygen species generation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 206, 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabnezhad, S.; Rassa, M.; Seifi, A. Green synthesis of Ag nanoparticles in montmorillonite. Mater. Lett. 2016, 168, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yao, Y.; Lian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shah, R.; Zhao, X.; Chen, M.; Peng, Y.; Deng, Z. A Double-Buffering Strategy to Boost the Lithium Storage of Botryoid MnO(x)/C Anodes. Small 2019, 15, 1900015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Xie, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Tao, R.; Popov, S.A.; Yang, G.; Shults, E.E.; Wang, C. Synthesis of novel ursolic acid-gallate hybrids via 1,2,3-triazole linkage and its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity study. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkan, K.; Rumjit, N.P.; Ngangbam, A.K.; Vijayanand, S.; Nedumpillil, N.K. Novel advancements in the sustainable green synthesis approach of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) for antibacterial therapeutic applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 499, 215528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, Z.; Kashmar, R.; Abdallah, A.M.; Awad, R.; Khalil, M.I. Characterization, antioxidant, antibacterial, and antibiofilm properties of biosynthesized Ag/AgCl nanoparticles using Origanum ehrenbergii Boiss. Results Mater. 2024, 21, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Kato, R.; Balamurugan, M.; Kaushik, S.; Soga, T. Efficiency improvement in dye sensitized solar cells by the plasmonic effect of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2017, 2, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nortjie, E.; Basitere, M.; Moyo, D.; Nyamukamba, P. Assessing the Efficiency of Antimicrobial Plant Extracts from Artemisia afra and Eucalyptus globulus as Coatings for Textiles. Plants 2024, 13, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonupara, T.; Kajitvichyanukul, P. Facile synthesis of plasmonic Ag/AgCl nanoparticles with aqueous garlic extract (Allium Sativum L.) for visible-light triggered antibacterial activity. Mater. Lett. 2020, 277, 128362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazman, Ö.; Khamidov, G.; Yilmaz, M.A.; Bozkurt, M.F.; Kargioğlu, M.; Tukhtaev, D.; Erol, I. Environmentally friendly silver nanoparticles synthesized from Verbascum nudatum var. extract and evaluation of its versatile biological properties and dye degradation activity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 33482–33494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Li, P.; Yang, L.; Wu, L.; Gao, F.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Z. Hydrothermal synthesis of magnetic sludge biochar for tetracycline and ciprofloxacin adsorptive removal. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, X.; Chen, D.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Chromium(VI) removal from synthetic solution using novel zero-valent iron biochar composites derived from iron-rich sludge via one-pot synthesis. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.B.; Mungmai, L.; Vimolmangkang, S.; Uputinan, S.; Panprommin, D.; Pathom-aree, W.; Auputinan, P. TLC-bioautography-guided valorization of vetiver (Chrysopogon spp.) leaf extracts into an anti-acne gel. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Jia, X.; Fu, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. Antioxidant peptides, the guardian of life from oxidative stress. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 275–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-y.; Li, P.-j.; Xie, R.-s.; Cao, X.-y.; Su, D.-l.; Shan, Y. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticle composites based on hesperidin and pectin and their synergistic antibacterial mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 214, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, S.; et al. Local Photothermal/Photodynamic Synergistic Therapy by Disrupting Bacterial Membrane To Accelerate Reactive Oxygen Species Permeation and Protein Leakage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 17902–17914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liang, H.; Yuan, G.; Wu, X.; Zheng, D. Genome-Wide Identification of Ralstonia solanacearum Genes Required for Survival in Tomato Plants. mSystems 2021, 6, e00838-00821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rtimi, S.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Pillai, S.C.; Kiwi, J. Advances in catalytic/photocatalytic bacterial inactivation by nano Ag and Cu coated surfaces and medical devices. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 240, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, R.; He, T.; Xu, K.; Du, D.; Zhao, N.; Cheng, X.; Yang, J.; Shi, H.; Lin, Y. Biomedical Potential of Ultrafine Ag/AgCl Nanoparticles Coated on Graphene with Special Reference to Antimicrobial Performances and Burn Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15067–15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.