Abstract

Although biochar and manure have been shown in many studies to influence abundant microbial communities, their differential effects on the rare and abundant microbial communities in soybean–corn intercropping systems remain poorly understood. Understanding how biochar and manure differentially shape these unique communities is critical to optimizing the sustainability and productivity of intercropping systems. Therefore, this study employed ITS and 16S rRNA sequencing to obtain the relative ASV abundance and thereby investigated how partial substitution of inorganic fertilizer with pig manure and corn stalk biochar influences the diversity, structure, assembly, and co-occurrence patterns of abundant and rare microbiota in border-row rhizospheres. Diversity analysis revealed that biochar and manure significantly increased the richness and evenness of rare fungal communities compared with conventional fertilization. In contrast, the richness and evenness of rare bacterial communities and abundant fungal communities remained stable. Null model analysis revealed that assembly processes shifted toward determinism for rare bacterial communities and toward stochasticity for rare fungal, abundant bacterial, and abundant fungal communities. Co-occurrence network analysis revealed that biochar and manure synergistically reduced the complexity and interaction strength of the rare bacterial network, whereas increasing the complexity and connectivity of the rare fungal network. These results demonstrate that biochar and manure promote distinct community assembly processes in border rows, thereby reshaping the ecological networks of rare and abundant taxa.

1. Introduction

Soybean–corn intercropping is a classic agricultural model widely practiced in developing countries [1]. It helps to protect and improve soil quality while stabilizing grain production [2]. However, interspecific competition between the intercropped species can deteriorate the rhizosphere microenvironment, limiting root nutrient cycling and spread [3,4,5]. It may be possible to alleviate these competitive stresses by applying soil amendments such as biochar and manure [6,7]. Biochar, a porous and highly aromatic material rich in functional groups and nutrients, provides suitable habitats for soil microorganisms [8,9]. This amendment promotes nutrient cycling in microbial communities, enhances soil ecosystem function, and thereby improves the soil environment [10]. Furthermore, manure can restructure soil microbiome composition, enhance sustainable microbial relative abundance, thereby fostering improved rhizosphere habitats under contrasting soil–plant regimes [11,12,13]. The inconsistent responses of rhizosphere microbial communities to biochar and manure have rendered their assembly mechanisms and interaction patterns unclear [14,15,16]. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the changes in microbial community composition and network interactions in the intercropped rhizosphere following biochar and manure application, in order to evaluate their mitigating effects on interspecific competition.

Previous work on biochar and manure impacts in soil microbiology has mainly addressed abundant taxa under monoculture, whereas rare taxa responses in intercropping contexts have received considerably less attention. Indeed, soil microbial communities typically display highly uneven distributions [17,18], characterized by a limited number of abundant species and numerous rare species. These rare taxa, despite their low abundance, exhibit remarkably high diversity [19]. Additionally, research has indicated that the rare taxa community structure is often more susceptible to deterministic processes [20], whereas abundant taxa assembly may be predominantly governed by stochastic processes [21,22]. As important sources of environmental heterogeneity, biochar and manure can significantly influence microbial community composition, diversity, and assembly processes [23,24]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate how these two amendments affect rare and abundant taxa in intercropping systems to comprehensively understand soil microbial functions. Furthermore, abundant and rare taxa exhibit markedly distinct ecological functions [25]. Abundant taxa primarily contribute to biomass maintenance and overall metabolic activities [26], such as carbon and nitrogen cycling processes, while rare taxa—despite their low abundance—contribute disproportionately high phylotype diversity to sustain ecosystem functions and enhance multifunctionality [23,27]. Accumulating evidence indicates that rare microbial taxa might buffer environmental stressors by increasing functional substitutability [19,28,29]. Rare taxa have been characterized as a microbial ‘seed bank,’ capable of transitioning to abundant status in response to environmental disturbances, thereby sustaining ecosystem resistance and functional stability [26,30,31]. However, empirical evidence for this phenomenon under biochar and manure application remains insufficient.

Soil microbiota are central to the niche differentiation processes of biochar and composted manure. Consequently, elucidating the response mechanisms of both abundant and rare taxa is essential for comprehending ecosystem processes and maintaining stability. We hypothesized that rare taxa would respond more sensitively to biochar and manure amendments than abundant taxa, and that rare subcommunities would exhibit greater sensitivity in their diversity, structure, assembly mechanisms, and co-occurrence patterns to environmental changes. This study aimed to (1) explore the diversity and composition of abundant and rare bacterial and fungal taxa (based on 16S rRNA and ITS sequencing, respectively) under biochar and manure amendments in the border-row rhizosphere; (2) clarify the assembly processes of these microbial taxa under these amendments; (3) reveal the co-occurrence network patterns as a network-level expression of these assembly processes. This study will demonstrate that rare taxa constitute key determinants of microbial community stability and function, providing novel theoretical insights for harnessing soil microbial communities to enhance intercropping system sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Experimental Layout and Management

The study area is located at Xiangyang Experimental Station, Northeast Agricultural University, Xiangfang District, Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province, China (45°34′–45°46′ N, 126°22′–126°50′ E), with mollisol soil type and a cold temperate continental monsoon climate. Rainfall in the region is mainly concentrated in July–August each year, with an average annual rainfall of roughly 400–600 mm and a frost-free period of about 140 days. Before sowing, 0–20 cm plow layer soil samples were sampled from five sampling points across the study plot. The basic physicochemical properties of the samples are: pH 6.05, a bulk density of 1.72 g/cm3, a conductivity of 92.45 µS/cm, a total nitrogen content of 1.27 g/kg, a total phosphorus content of 0.37 g/kg, a total potassium content of 18.98 g/kg, and an organic carbon content of 14.18 g/kg.

The field experiment was conducted during the 2024 growing season (May to October) using a completely randomized block design. The total plot area was 26.4 m × 10.4 m, with row spacing of 65 cm and plant spacing of 27 cm. The specific field layout is shown in Figure S1. Four treatment groups were established, each with three replicate plots. All treatments received chemical NPK (N-P2O5-K2O 12-18-15) fertilizer applied at 525 kg/ha for corn and 315 kg/ha for soybean, with amendments as follows: control (CK); manure addition at 7500 kg/ha (M); biochar addition at 10 t/ha (B); and co-application of manure (7500 kg/ha) and biochar (10 t/ha) (MB). The biochar used in the experiment was purchased from Liaoning Jinhefu Development Co., Ltd. (Anshan, China), with corn stalk as the raw material. And its specific physicochemical properties are presented in Table S1. Specific fertilizer application rates are detailed in Table S2. Before sowing, the biochar and manure were spread evenly on the ground surface, followed by repeated turning and mixing using a rotary tiller (1WGQZ4.0-100C, Weima Agricultural Machinery Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) to ensure full integration. The chemical NPK fertilizer was applied at once as a base fertilizer.

2.2. Rhizosphere Soil Sampling and Processing

In September 2024, rhizosphere soil was collected during the maize filling and soybean bulking stages from border rows (maize rows adjacent to soybean rows) in the intercropping system. Five plants were randomly selected from border rows; soil beyond 10 cm from the root system was removed with a knife, and the 1–3 cm layer adhering to root surfaces was harvested using a sterile brush. Subsequently, the soil samples were sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove roots and debris, then thoroughly homogenized. Following this, the homogenized samples were split into three subsamples, transferred to sterile self-sealing bags, and immediately transported to the laboratory under ice-cooled conditions. Specifically, one subsample was preserved at −80 °C for soil microbial DNA extraction; a second was held at 4 °C for the analysis of ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N), and soil pH; and the third was air-dried to determine total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) contents.

2.3. Maize Yield and Soil Physicochemical Analysis

At maize maturity, five healthy maize plants were randomly selected per replicate plot for grain yield assessment. Grain samples were oven-dried, weighed, and standardized to 14% moisture content. Fresh soil NH4+-N and NO3−-N contents were quantified via indophenol blue and KCl extraction-dual wavelength methods, respectively, while pH and electrical conductivity were determined using pH and EC meters, respectively. Air-dried soils underwent separate analyses: total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) were determined via an elemental analyzer (EA), while total phosphorus (TP) and total potassium (TK) were quantified using a soil nutrient rapid analyzer (Zhejiang Tuopuyun TPY-16A, Zhuji, China). Soil organic carbon was measured separately using potassium dichromate oxidation-spectrophotometry.

2.4. Extraction of Microbial DNA and Amplicon Sequencing

Soil samples were maintained on dry ice during transit to Hangzhou Lianchuan Biotechnology Co. (Hangzhou, China), where total microbiome DNA was isolated via cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocols. Extract integrity and concentration were evaluated through 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Bacterial communities were profiled through V3–V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA genes, while fungi were targeted through ITS2 region amplification, employing primer sets 341F/805R (5′-CCTACGGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′/5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) and fITS7/ITS4 (5′-GTGARTCATCGAATCTTTG-3′/5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATATGC-3′), respectively. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were assembled with 12.5 µL Phusion® Hot Start Flex 2× Master Mix (NEB, M0536L, Ipswich, MA, USA), 2.5 µL each primer, 50 ng template DNA, and 25 µL of ddH2O. Amplification conditions included an initial denaturation at 98 °C (30 s), followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C (10 s), annealing at 50 °C (30 s), and extension at 72 °C (45 s), concluding with a final extension at 72 °C (10 min). Resulting amplicons underwent purification (AMPure XT beads; Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA, USA), quantification (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and electrophoretic verification on 2% agarose gels prior to sequencing.

2.5. Libraries Generated and High-Throughput Sequencing

Libraries were constructed using the NEB Next® Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) per manufacturer instructions with indexed adapters. Quality assessment employed the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Kapa Biosciences quantification kit (Woburn, MA, USA). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (PE250), generating 250 bp paired-end reads. Post-sequencing processing included demultiplexing, adapter/barcode trimming, and paired-end assembly via FLASH (v1.2.8). Clean tags were generated through fqtrim (v0.94) quality control with stringent filtering, and chimeras were eliminated using Vsearch (v2.3.4). DADA2 was utilized for denoising and ASV delineation, yielding feature sequences and abundance profiles. Taxonomic assignments for bacteria and fungi were performed against SILVA (Release 138) and RDP (unite) database. The ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1% were defined as abundant taxa, those with <0.01% were defined as rare taxa, and those between 0.01 and 0.1% were considered moderate taxa [32]. Subsequently, based on the KEGG database, the metabolic functions of the rare and abundant communities were predicted using the PICRUSt2 tool on the Wekemo Bioincloud platform (https://www.bioincloud.tech (accessed on 27 August 2025)), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the phylogenetic tree construction tool on the same platform [33].

2.6. Sequencing Data Processing

All statistical procedures described below were performed using R software (version 4.4.1). For analyzing alpha diversity of abundant and rare microbial taxa, we applied one-way ANOVA followed by LSD post hoc tests through the ‘agricolae’ package. Community structure patterns were examined via principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Jaccard distances, implemented with the ‘vegan’ package, and subsequently compared using PERMANOVA. The ‘microeco’ package enabled sequential Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon testing to identify differentially abundant species within abundant and rare microbial groups. Biomarker discovery was accomplished using LEfSe with an LDA threshold exceeding 3.0.

2.7. Community Assembly and Network Processing

We calculated the β-nearest taxon index (β-NTI), a standardized effect size that measures the deviation of the observed β-mean nearest taxon distance (β-MNTD) from a null model expectation, to assess the ecological processes driving community assembly based on phylogenetic distance. Specifically, β-MNTD represents the mean phylogenetic distance between each species in one community and its closest relative in another community, while β-NTI indicates whether this process is significantly higher or lower than expected by chance [34]. Accordingly, values of |β-NTI| > 2 and |β-NTI| < 2 indicate a community that is dominated by deterministic processes and stochastic processes, respectively [35]. All phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the picante package in R. The niche breadth of both abundant and rare species, which characterizes community sensitivity to environmental conditions, was calculated using the β-diversity “niche breadth” function [36] in “spaa”. Subsequently, the “niche overlap” index was calculated for both abundant and rare species to quantify competitive intensity [37]. The “WGCNA” and “igraph” packages were used to construct the co-occurrence network of the microbial subcommunities (|r| > 0.6; p < 0.001), and network visualization was performed using the Gephi v0.10.1 software. Subsequently, we used the igraph package to generate 1000 random networks with identical degree sequences for each empirical network based on the configuration model and calculated the characteristics of these random networks to assess the non-randomness of empirical network structures. Meanwhile, we tested the differences in characteristics between the random and empirical networks using t-tests [38].

3. Results

3.1. Diversity Analysis of Microbiota

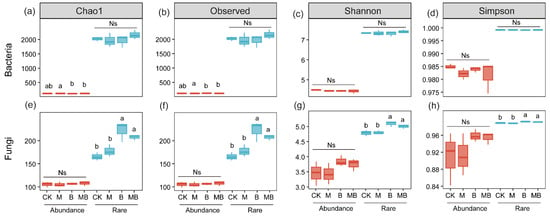

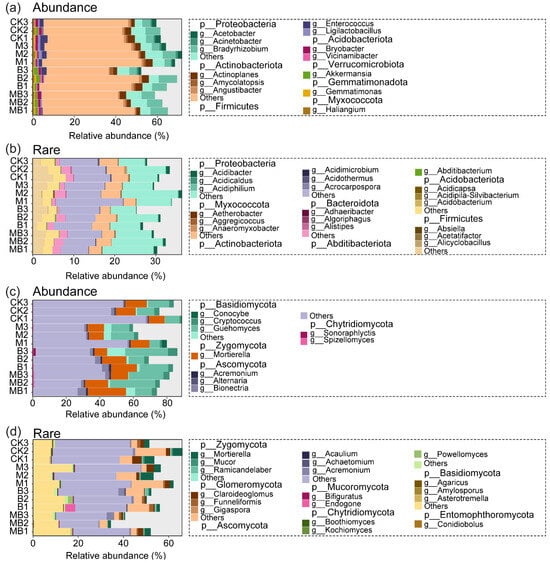

After quality control, the ASVs of bacteria and fungi in all processed soil samples were 16,627 and 1963, respectively (Figure S2). Specifically, the rare and abundant bacterial taxa accounted for 14,616 and 119 ASVs, respectively, while their relative abundances were 23.2% and 50.3%. For fungi, the numbers of ASVs for rare and abundant taxa were 1434 and 130, respectively, yet their relative abundances showed a stark contrast at 3.4% and 84.4%. The richness (ASV number) of rare taxa was one to two orders of magnitude higher than that of abundant taxa. In contrast, the relative abundance of abundant taxa was several to dozens of times greater than that of rare taxa. The results of the abundance–occupancy relationship showed that rare bacterial communities showed a stronger positive correlation than abundant bacterial communities (Figure S3c,d). The Chao1 and Observed indices are commonly used to measure the number of species in microbial communities, while the Shannon and Simpson indices are used to assess the evenness of distribution of individuals among different species within microbial communities. In the rhizospheres of B and MB, the species richness (Chao1 and Observed) and evenness (Shannon and Simpson) indices of the rare fungal communities were significantly higher than those in the rhizospheres of CK and M (p < 0.05), whereas these indices of the abundant fungal communities showed no significant changes (p > 0.05; Figure 1e–h). Furthermore, the richness and evenness indices did not significantly differ between MB and B treatments for either rare or abundant fungal communities (p > 0.05; Figure 1e–h). Additionally, compared with CK, the species richness and evenness indices of both the rare and abundant bacterial communities in the rhizospheres of B and MB showed no significant changes (p > 0.05; Figure 1a–d). However, the richness index of the abundant bacterial community in the rhizosphere of MB was significantly higher than that in the rhizosphere of M (p < 0.05; Figure 1a,b). In all treatments, the richness and evenness indices of rare taxa were higher than those of abundant taxa. The abundant bacterial community was dominated by Actinobacteriota (60%), Proteobacteria (15%), Chloroflexi (8%), Acidobacteriota (6%), and Gemmatimonadota (4%) (Figure 2a), while the rare bacterial community was dominated by Actinobacteriota (19%), Planctomycetota (19%), Proteobacteria (17%), Acidobacteriota (8%), Chloroflexi (7%), Myxococcota (6%), Verrucomicrobiota (5%), Firmicutes (4%), Gemmatimonadota (4%), and Bacteroidota (4%) (Figure 2b). The abundant fungal community was dominated by Ascomycota (60%), Basidiomycota (28%), and Zygomycota (12%) (Figure 2c), while the rare fungal community was primarily composed of Ascomycota (47%), Basidiomycota (18%), Glomeromycota (9%), and Chytridiomycota (4%) (Figure 2d). Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, and Chytridiomycota were dominated by rare taxa in the MB rhizosphere, whereas no significant difference was observed between abundant and rare taxa in the CK rhizosphere (Figures S3 and S4). Gemmatimonadota was dominated by abundant taxa in the MB rhizosphere, while no significant difference was observed between abundant and rare taxa in the CK rhizosphere (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Analysis of microbial α-diversity and relative abundance under different treatments. (a–d) Analysis of bacterial richness (Chao1 and Observed) and evenness (Shannon and Simpson) indices. (e–h) Analysis of fungal richness (Chao1 and Observed) and evenness (Shannon and Simpson) indices. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05); Ns indicates no significant difference (p > 0.05). CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the relative abundance of abundant and rare bacteria (a,b) and fungi (c,d). CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

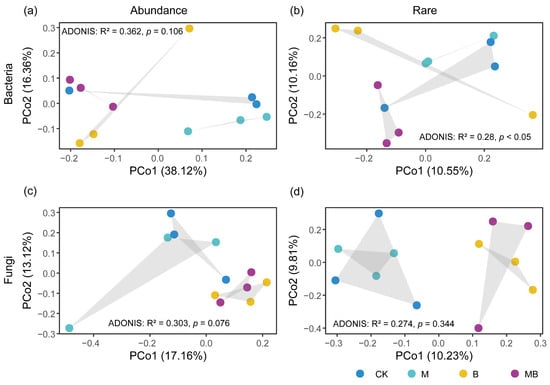

The principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Jaccard indicated that rare bacteria exhibited higher community differences compared with abundant bacteria (Figure 3a,b), but there was no significant difference in the community structure between rare fungi and abundant fungi (Figure 3c,d). PCoA 1 and PCoA 2 accounted for 20.71% (10.55% and 10.16%, respectively) of the variation in the rare bacterial community (Figure 3b) and 20.04% (10.23% and 9.81%, respectively) of the rare fungal community variation (Figure 3d). The rare bacterial communities of MB and B were distinctly separated along Axis 2 (Figure 3b), while the rare fungal communities were densely distributed (Figure 3d). The null model analysis elucidated that the influences of determinism (i.e., βNTI ≥ 2 or βNTI ≤ −2) and stochasticity (i.e., −2 < βNTI < 2) on community assembly in the rhizosphere under different treatments exhibited variations (Figure S6). In the CK, M, and B rhizospheres, the β-NTI values of most rare and abundant taxa communities fell between −2 and 2 (Figure S6), showing that stochastic processes predominantly governed most communities in the CK, M, and B rhizospheres. In the MB rhizosphere, the β-NTI values of most rare bacterial taxa were below −2 (Figure S6d), whereas those of abundant bacterial taxa, rare fungal taxa, and abundant fungal taxa ranged between −2 and 2 (Figure S6a–c), showing that the community assembly of rare bacterial taxa in the MB rhizosphere was predominantly governed by deterministic processes, while those of abundant bacterial taxa, rare fungal taxa, and abundant fungal taxa were primarily driven by stochastic processes. The β-NTI values of rare fungal taxa in the MB rhizosphere were significantly higher than those in the CK rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure S6b), whereas the β-NTI values of abundant bacterial taxa were significantly lower than those in the CK rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure S6c).

Figure 3.

The principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of abundant and rare microbial communities under different treatments. (a,b) PCoA analysis of abundant and rare bacterial communities based on Jaccard distance. (c,d) PCoA analysis of abundant and rare fungal communities based on Jaccard distance. ADONIS denotes permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

3.2. Community Assembly of Microbiota

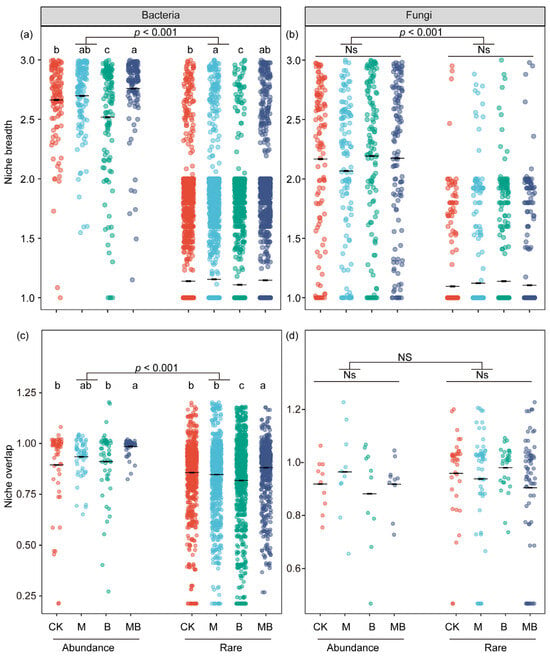

Niche breadth quantifies the extent to which a species can exploit a range of resources or tolerate varying environmental conditions [39], whereas niche overlap describes the extent to which different species share the use of the same resources or occupy similar ecological niches [40]. Compared with rare bacterial and fungal communities, abundant bacterial and fungal communities exhibit higher niche breadth (p < 0.001; Figure 4a,b). The niche widths of both abundant and rare bacterial groups in the B rhizosphere were significantly narrower than those in the CK rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure 4a), while niche overlap among rare bacterial communities was significantly lower in the B rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure 4c). Both the niche width and niche overlap of abundant and rare bacterial communities in the MB rhizosphere were significantly higher than those in the B rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure 4a,c). Additionally, the niche width of abundant bacterial communities in the MB rhizosphere was significantly higher than that in the CK rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure 4a), while the niche overlap of both abundant and rare bacterial communities was also significantly higher than that in the CK rhizosphere (p < 0.05; Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

The niche breadths and overlap difference in abundant and rare taxa. The average niche width for abundant species and rare species in bacteria (a) and fungi (b), respectively. The average niche overlap for abundant species and rare species in bacteria (c) and fungi (d), respectively. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05); Ns indicates no significant difference (p > 0.05). CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

3.3. Co-Occurrence Network of Microbial Communities

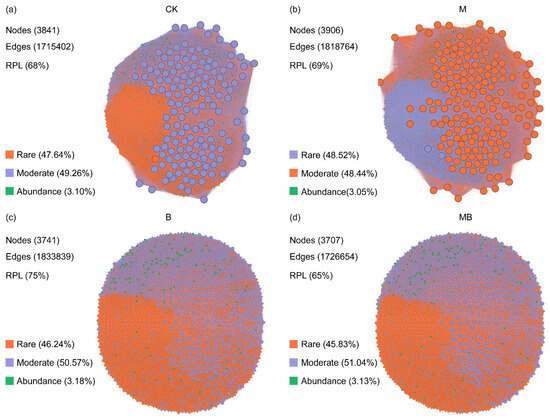

The co-occurrence networks for the abundant and rare microbes were constructed based on the Spearman correlations between the ASVs to explore the interconnection of microorganisms after the application of biochar and manure (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Among these network properties, nodes represent ASVs, the basic operational taxonomic units of microorganisms. The degree distribution, number of edges, and clustering coefficients reflected the connectivity between nodes in the network and the strong interactions between microorganisms [41]. A module is a group of nodes that are highly interconnected within the group but have fewer connections outside, reflecting the degree of functional or niche differentiation within microbial communities [42]. The ratio of positive links indicates mutually beneficial or synergistic relationships between microbial taxa [43]. Co-occurrence network analysis of the bacterial community revealed that the majority of nodes belonged to rare and Moderate taxa (Figure 5). Compared with the CK treatment, the M treatment increased the number of nodes (3906) and edges (1,818,764), as well as the proportion of positive connections (69%) (Figure 5b). The B treatment increased the number of edges (1,833,839) and the proportion of positive connections (75%), but decreased the number of nodes (3741) (Figure 5c). The MB treatment increased the number of edges (1,726,654), but decreased the number of nodes (3707) and the proportion of positive connections (65%) (Figure 5d). In addition, in the co-occurrence network of fungal communities, the majority of nodes were rare and Moderate taxa (Figure 6). Compared with the CK treatment, the M treatment increased the number of nodes (980), edges (161,753), and the proportion of positive connections (87%) (Figure 6b). The B treatment increased the number of nodes (1088) and edges (174,559), but decreased the proportion of positive connections (82%) (Figure 6c). The MB treatment increased the number of nodes (1069), edges (181,158), and the proportion of positive connections (86%) (Figure 6d).

Figure 5.

Co-occurrence network analysis of bacterial communities for CK (a), M (b), B (c), and MB (d) treatments. Different colors represent different communities. RPL denotes the ratio of positive links. CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%. Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%; Moderate denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance between 0.01% and 0.1%.

Figure 6.

Co-occurrence network analysis of fungal communities for CK (a), M (b), B (c), and MB (d) treatments. Different colors represent different communities. RPL denotes the ratio of positive links. CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%; Moderate denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance between 0.01% and 0.1%.

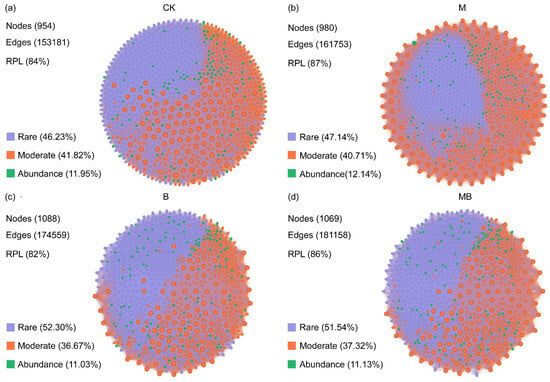

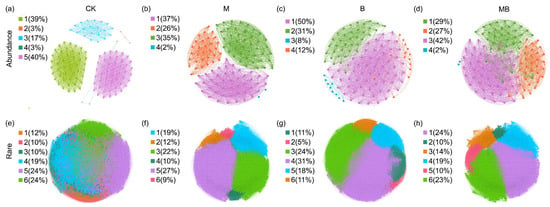

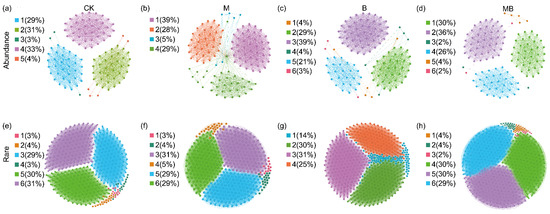

Subsequently, subnetworks were constructed for the abundant and rare communities, respectively (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The topological characteristics of the subnetwork showed that the rare taxa network was broader and had more modules and a higher modularity, average degree (AD), and ratio of positive links (RPL) compared with the abundant taxa network. Meanwhile, the abundant taxa had a higher average clustering coefficient (ACC) (Figure 7; Table S3). Compared with CK, M decreased the number of edges (2273), the number of modules (4), and the proportion of positive links (51%) in the abundant bacterial network (Figure 7b; Table S3) but increased the number of edges (349932), the number of nodes (1895), and the average degree (369) in the rare bacterial network (Figure 7f; Table S3). B increased the number of edges (2504) and average degree (42) in the abundant bacterial network (Figure 7c; Table S3) but decreased its number of modules (4). Conversely, in the rare bacterial network, it increased the number of edges (319,581), average degree (369), and proportion of positive links (90%) (Figure 7g; Table S3), while reducing the number of nodes (1730). MB decreased the number of edges (2203 and 1699), nodes (116 and 268979), average degree (38 and 42), and proportion of positive links (50% and 80%) in the abundant and rare bacterial networks, respectively (Figure 7d,h; Table S3). Additionally, the M, B, and MB treatments increased network metrics for abundant fungi relative to CK, with edges of 2009, 1999, and 2010; nodes of 120, 120, and 119; average degrees of 34, 33, and 34; and proportions of positive links of 60%, 50%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 8b–d; Table S4). The rare fungal networks responded more dramatically, with edges increasing to 28,067, 41,551, and 41,138; nodes to 462, 569, and 551; and the average degrees to 122, 146, and 149, respectively (Figure 8f–h; Table S4).

Figure 7.

Co-occurrence network analysis of bacterial communities for the abundant (a–d) and rare (e–h) species. Different colors represent different modules. CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

Figure 8.

Co-occurrence network analysis of fungal communities for the abundant (a–d) and rare (e–h) species. Different colors represent different modules. CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

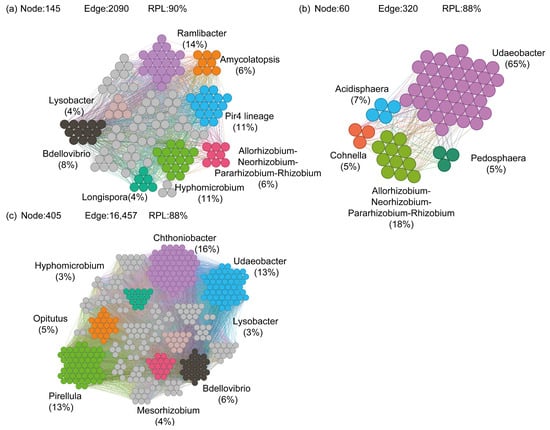

A co-occurrence network was constructed based on the biomarkers identified using LEfSe to assess their cooperative characteristics, displaying only interactions with significant correlations (|R| > 0.6, p < 0.05). The LEfSe results revealed that compared with CK, the M rhizosphere significantly enriched abundant phyla within the genus Geodermatophilus (p < 0.05; Figure S7a) and rare phyla within genera such as Hyphomicrobium (p < 0.05; Figure S8a). The B rhizosphere significantly enriched abundant bacterial lineages within the genus Gaiella (p < 0.05; Figure S7b) and rare bacterial lineages within the genus Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium clade (p < 0.05; Figure S8b). The MB rhizosphere significantly enriched abundant bacterial groups within genera such as Micromonospora, Gaiella, and Pseudonocardia (p < 0.05; Figure S7c) and rare bacterial groups within genera such as Chthoniobacter, Pirellula, and Mesorhizobium (p < 0.05; Figure S8c). Additionally, compared with CK, the M rhizosphere significantly enriched abundant fungal phyla from genera such as Acremonium and Kotlabaea (p < 0.05; Figure S9a), as well as rare fungal phyla from genera including Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula, and Gamsia (p < 0.05; Figure S10a). The B rhizosphere significantly enriched abundant fungal communities from genera such as Khuskia, Acremonium, and Plectosphaerella (p < 0.05; Figure S9b), as well as rare fungal communities from genera including Glomus, Cryptococcus, and Torula (p < 0.05; Figure S10b). The MB rhizosphere significantly enriched abundant fungal communities from genera such as Sistotrema, Lecythophora, and Spizellomyces (p < 0.05; Figure S9c), as well as rare fungal communities from genera including Cyathus, Rhodotorula, and Auriculibulle (p < 0.05; Figure S10c). Moreover, only the co-occurrence network of biomarkers for rare bacterial communities was constructed due to the limited number of OTUs for biomarkers of abundant bacterial and fungal communities and rare fungal communities. The results showed that the complexity and connectivity of the MB biomarker network were significantly stronger than those of B and M. The number of ASV nodes in the biomarker network of M was 145; the number of edges and the ratio of positive connections between different ASV nodes were 2090 and 90%, respectively; and the genera of the majority of ASV nodes were Ramlibacter (14%), Pir4 lineage (11%), and Hyphomicrobium (11%) (Figure 9a). The number of ASV nodes in the biomarker network of B was 60; the number of edges between different ASV nodes and the ratio of positive connections were 320 and 88%, respectively; and the genera of most of the ASV nodes were Udaeobacter (65%) and Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium clade (18%) (Figure 9b). The number of ASV nodes in the biomarker network of MB was 405. The number of edges and the positive connectivity ratio between different ASV nodes were 16457 and 88%, respectively, and the genera of most of the ASV nodes were Chthoniobacter (16%), Udaeobacter (13%), and Pirellula (13%) (Figure 9c).

Figure 9.

Co-occurrence network of biomarkers in soils of M (a), B (b), and MB (c) groups. RPL is the ratio of positive links. Different colors represent different genera. M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar.

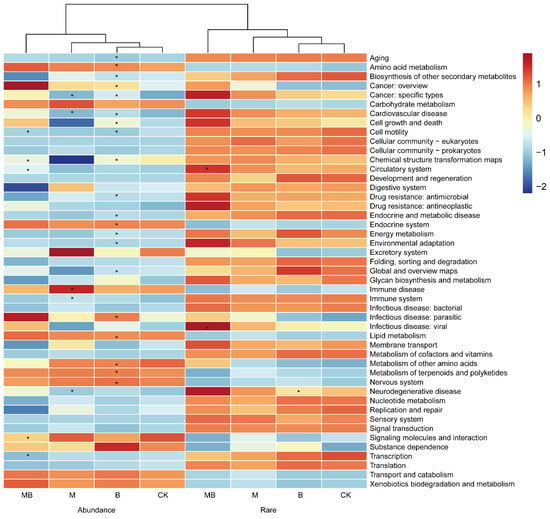

3.4. Function of Microbial Communities

The ITS and 16S rRNA gene sequencing data were entered into the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database to predict the effects of biochar and manure on fungal and bacterial functions. KEGG (level 2) functional information was obtained via functional prediction with PICRUSt2, and 44 and 71 predicted metabolic functions were inferred for the bacterial and fungal communities, respectively (Figure 10; Figure S9). These predictive analyses indicated that functional abundance was higher in rare communities than in abundant communities. Compared with CK, B was predicted to significantly reduce species abundance in abundant bacterial communities for functions involved in basic metabolism and cellular processes, such as amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, and cell growth and death (p < 0.05), while having no significant effect on functional abundance in rare bacterial communities (p > 0.05; Figure 10). MB was predicted to significantly increase species abundance in rare bacterial communities involved in circulatory system and cell motility functions. However, it was predicted to significantly decrease species abundance in abundant bacterial communities involved in chemical structure transformation maps and cell motility functions (p < 0.05; Figure 10). Additionally, compared with CK, B was predicted to significantly reduce the abundance of species involved in nucleotide and amino acid biosynthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, and lipid metabolism within the abundant fungal community, while increasing the abundance of species associated with sugar, lipid, and nucleotide metabolism within the rare fungal community (p < 0.05; Figure S9). MB was predicted to significantly reduce species richness in the abundant fungal group involved in nucleotide metabolism and significantly increase species richness in the rare fungal group involved in lipid and nucleic acid synthesis and metabolism (p < 0.05; Figure S9).

Figure 10.

Relative abundance of bacterial metabolic functions in soil across treatment groups. The colors progress from blue to red, representing a gradual increase in functional abundance. CK denotes control; M denotes manure addition; B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%. * p < 0.05.

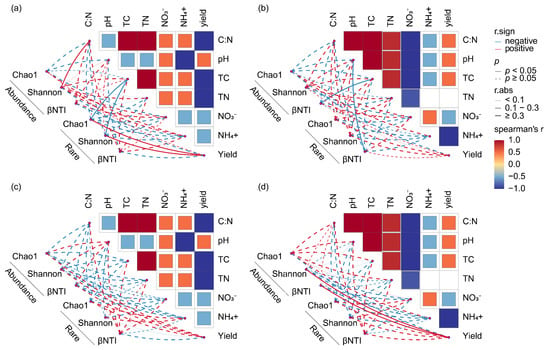

3.5. Correlation Analysis Between Soil Physicochemical Properties, Yield, and Microbial Communities

In the border-row rhizosphere, soil bacteria were more sensitive to biochar than fungi, and the combination of biochar and organic fertilizer altered the effects of soil properties on abundant and rare bacterial and fungal communities under single biochar application (Figure 11). In the border-row rhizosphere of the MB treatments, the Shannon index of abundant bacterial communities was significantly positively correlated with C–N, while the Chao1 and Shannon indices of rare bacterial communities were significantly positively correlated with yield but significantly negatively correlated with TC content (p < 0.05; Figure 11a). However, in the border-row rhizosphere of the M treatment, the βNTI index of abundant bacterial communities was significantly negatively correlated with TC content, while the βNTI index of rare bacterial communities was significantly positively correlated with pH but significantly negatively correlated with TC content (p < 0.05; Figure 11b). Additionally, in the border-row rhizosphere of the M treatment, the βNTI and Shannon indices of abundant bacterial communities were significantly positively correlated with yield (p < 0.05; Figure 11d).

Figure 11.

Spearman correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties, yield, and microbial community. (a) Correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties, yield, and bacterial community under MB treatment. (b) Correlation analysis between soil physical and chemical properties, yield, and bacterial community under B treatment. (c) Correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties, yield, and fungal community under MB treatment. (d) Correlation analysis between soil physical and chemical properties, yield, and fungal community under B treatment. Red represents positive correlation, and blue represents negative correlation. βNTI denotes beta nearest taxon index. B denotes biochar addition; MB denotes co-application of manure and biochar. Abundance denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of >0.1%; Rare denotes the ASVs with a relative abundance of <0.01%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity and Structure of Abundant and Rare Species Communities in Response to Biochar and Manure

Consistent with previous findings [44,45,46], the application of biochar and manure in intercropping systems exerted significant effects on the composition and structure of rhizosphere microbial communities in the border-row rhizosphere. In this study, abundant prokaryotic groups were widely distributed in the border-row rhizosphere, while rare prokaryotic bacterial and fungal groups accounted for only 23.2% and 3.4% of the collected samples, respectively. This phenomenon arises because abundant groups possess stronger competitive abilities and broader ecological adaptability in the specialized microenvironment of the border-row rhizosphere, enabling them to efficiently acquire and utilize resources, thereby gaining a dominant position in interspecific competition. In contrast, despite comprising numerous species, rare groups exhibit low individual abundance per species [31]. Overall, the rare groups exhibited significantly higher species richness and evenness than the abundant groups and showed greater sensitivity to responses to biochar and manure (Figure 1). This aligns with studies by Qin et al. [47], potentially because abundant groups possess higher nutrient resource competition capabilities, making them more resilient and resistant to environmental changes [48]. In contrast, rare taxa contribute less to total abundance and occupy narrower niches [24,49]. At the individual level, they are characterized by specialized resource requirements and limited adaptability. Xu et al. [50] found that rare bacterial communities were more sensitive to soil amendment-induced environmental changes in soil pH, Cd, and soil organic matter than abundant bacterial communities. Biochar and manure can stabilize cadmium and other metals in soil by forming stable organic ligand–metal complexes [51], potentially affecting rare species communities. Although both biochar and manure are rich in base cations that can neutralize soil acidity, biochar exhibits a stronger pH-buffering capacity than manure due to its functional groups, such as -COO− and O− [52,53,54,55]. Consequently, the synergistic effect of these two materials has led to changes in rare microbial communities. Furthermore, the richness and evenness of rare fungi in the rhizosphere of boundary rows treated with MB were significantly higher than in those treated with CK, while the richness and evenness of rare bacteria showed no significant changes. However, their community structure was significantly altered (Figure 3). This aligns with Zhang et al.’s findings [24]. Deshoux et al.’s review [56] showed that fungal diversity indices are influenced by soil texture, pH, and nutrient content. Indeed, biochar produced from different feedstocks under varying pyrolysis parameters possesses distinct physicochemical properties [57], and its co-application with manure may differentially alter soil microbial diversity [45,58,59]. The corn straw biochar and pig manure used in this study exhibited high alkalinity, which could directly neutralize soil acidity [60]. Simultaneously, the organic-rich manure, through biochar’s adsorptive effects, modified the soil environment [61,62,63], thereby increasing the diversity of rare fungi. Moreover, the community structure of rare bacteria underwent significant changes, indicating altered structural distribution patterns among different species. Specifically, in the rhizosphere of biochar and manure treatments, rare species within abundant phyla such as Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, and Chytridiomycota significantly increased. In the rhizosphere, Proteobacteria emerged as one of the major enriched groups. These bacteria are considered eutrophic, capable of adapting to carbon-rich environments with high metabolic activity and rapid growth [64]. Firmicutes represent a large group of Gram-positive, eutrophic bacteria characterized by thick peptidoglycan cell walls, exhibiting high abundance in the rhizosphere of grass crops [65,66,67]. Acidobacteria represent one of the most abundant bacterial groups in soil, particularly prevalent in acidic soils and oligotrophic environments. As oligotrophic organisms, they exhibit diverse metabolic functions, including carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur metabolism [68]. Chytridiomycota is a basal phylum within the fungal kingdom, whose members are minute saprophytes or parasites. This phylum comprises two classes: Monoblepharidomycetes and Chytridiomycetes, both widely distributed in soil environments [69]. Studies by Liao et al. [70] and Xu et al. [71] revealed that the relative abundance of phyla such as Proteobacteria and Firmicutes showed a significant positive correlation with soil C–N ratios. Thus, rare subclade species within these abundant phyla accumulate in rhizosphere soils treated with biochar and manure. This may occur because biochar, with its highly porous structure and large surface area, increases the C–N ratio in rhizosphere soils. Meta-analyses by Denoncourt et al. [72] and Maillard et al. [73] showed that animal manure, which is rich in organic carbon and nitrogen, directly inputs large sources of carbon and nitrogen to the soil and indirectly increases the soil C–N ratio by promoting the accumulation of particulate organic matter (POM) and mineral-bound organic matter (MAOM). Simultaneously, rare subclades are more susceptible to environmental changes [74]. This led to a change in the relative abundance of rare subfamilies in these clades, driven by the synergy of biochar and manure, and to rare subfamilies contributing a greater diversity of ecological functions than productive subfamilies.

4.2. Assembly Process of Abundant and Rare Species Communities in Response to Biochar and Manure

Furthermore, we analyzed the assembly mechanisms of abundant and rare microbial communities to advance our understanding of the driving forces shaping microbial composition and reveal the competitive relationships among them. In this study, biochar and manure influenced the community composition of abundant and rare taxa through random processes when applied individually. However, their combined application altered the balance between determinism and random processes in the rhizosphere of border rows, affecting the composition of rare and abundant communities. They exerted a decisive synergistic effect on rare bacterial communities while producing random effects on rare fungal communities and abundant bacterial and fungal communities. This aligns with the findings of Jiao et al. [75] and Wang et al. [20]. Jiao et al. revealed that soil pH and temperature regulate the assembly processes of abundant and rare subcommunities, respectively [76]. Wu et al. reported that biochar leads to deterministic processes dominating bacterial community assembly by providing suitable abiotic environmental conditions, whereas stochastic processes dominate in fungal communities [77]. Therefore, shifts in the assembly processes of rare and abundant microbial communities can be attributed to differences in life history strategies and dispersal potential among rare and abundant bacteria, as well as among rare and abundant fungi [78,79,80]. Compared to bacterial communities, fungal communities are more resistant to environmental changes induced by biochar addition [81]. Meanwhile, biochar and manure provide nutrients and suitable habitats for the development of abundant microbial communities [82,83], thereby favoring stochastic processes in abundant taxa. Furthermore, in this study, the niche widths of most rare taxa in all root-zone treatments were significantly narrower than those of abundant taxa. This aligns with the observed lower tolerance of rare taxa to environmental disturbances and the greater adaptability of abundant taxa to environmental changes [84], indicating that stochastic processes play a more significant role in the assembly of abundant communities. Moreover, compared with CK, the niche overlap indices between rare and abundant bacterial communities significantly increased in the rhizosphere under the biochar and manure treatments, with abundant bacteria exhibiting higher niche overlap indices than rare bacteria. However, no significant changes were observed in the niche overlap indices between rare and abundant fungal communities (Figure 4). This may be attributed to the synergistic enhancement of organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus levels in the rhizosphere by biochar and manure [85,86], improved rhizosphere porosity [87], and the creation of resource-enriched microdomains that promoted closer coexistence among bacterial groups with similar resource requirements, thereby intensifying competition [88,89]. Additionally, under the biochar and manure treatments, competition among rare bacterial communities was lower than among abundant bacterial communities. This may be because rare bacteria are predominantly dormant and possess narrower niche widths, awakening and gaining dominance only under favorable environmental conditions [31,90,91], making them less sensitive to environmental competition than abundant bacterial groups. Furthermore, Xue et al. [92] found that fungal communities exhibit strong resistance and resilience to environmental changes and disturbances. This aligns with this study’s findings, potentially because fungal communities rely more heavily on resource utilization strategies involving the decomposition of refractory organic matter, such as lignin and cellulose [93]. Since biochar and manure have limited direct effects on these substrates, the pattern of interspecific niche differentiation among fungi remains stable.

4.3. Co-Occurrence Patterns of Abundant and Rare Species Communities in Response to Biochar and Manure

Compared with simple descriptions of community diversity indices and assembly patterns, network analysis provides in-depth insights into microbial subcommunity interactions, deepening our understanding of underlying ecological relationships [94,95]. In this study, despite occupying lower abundances, rare subpopulations exhibited significantly higher network topological features—including the number of modules, modularity index, average degree, and positive connectivity ratio—compared with abundant subpopulations (Figure 7 and Figure 8). This indicates that rare subpopulations possess greater network complexity and connectivity than abundant subpopulations, as reported by Calatayud et al. [96] and Tian et al. [97]. This further confirms that rare taxa maintain coexistence through positive interactions and exhibit a greater tendency toward cooperation in resource competition. Compared with CK, the biochar and manure treatments reduced the number of edges, nodes, average degree, and positive connectivity ratio in rare bacterial networks (Figure 7), while increasing the number of edges, nodes, and average degree in rare fungal networks (Figure 8). This indicates that biochar and manure synergistically reduced the complexity and interaction intensity of rare bacterial networks while enhancing the complexity and connectivity of rare fungal networks. This aligns with Qi et al.’s findings [98]. The reduction in topological features of rare bacterial networks may stem from biochar and manure significantly increasing the soil carbon and nitrogen content, promoting bacterial community succession toward oligotrophic groups, and diminishing redundant interactions among rare taxa [62,99]. In this study, the rare oligotrophic bacterial genera Chthoniobacter, Pirellula, and Udaeobacter, serving as biomarkers, showed significant enrichment in the rhizosphere under biochar and manure treatments (Figure 9c), further supporting this conclusion. Pirellula is an oligotrophic genus within the Planctomycetota phylum characterized by unique cellular structures and reproductive modes, significantly influencing soil nutrient cycling and enzyme activities, such as urease and protease [100]. Chthoniobacter is an oligotrophic genus within the Verrucomicrobiota phylum involved in the degradation of plant-derived organic matter, particularly the breakdown of xylan-type hemicellulose [101]. It is primarily distributed in peatland soils. Udaeobacter is also an oligotrophic genus within the Verrucomicrobiota phylum, likely oxidizing trace gases such as H2 to generate energy and participating in the hydrogen cycle [102]. However, in this study, the topological characteristics of the rare bacterial network increased under manure treatment alone, while they decreased under biochar treatment alone. This suggests that the reduction in topological characteristics of the rare bacterial network is primarily influenced by biochar. The Udaeobacter genus was significantly enriched under biochar treatment, accounting for over half of the positive connectivity edges (Figure 9b). This further demonstrates that biochar-amended treatments promoted the succession of bacterial communities toward oligotrophic states and fostered greater cooperative tendencies. This may have occurred because biochar elevates the soil C–N ratio, potentially inducing soil nitrogen limitation [62]. Moreover, biochar adsorption of unstable organic carbon may reduce soluble organic carbon in the soil, necessitating oligotrophic organisms as dominant players to obtain energy and nutrients for survival. This aligns with the nutrient mining hypothesis [62,103,104]. Furthermore, the increase in topological properties of rare fungal networks may relate to the nutritional strategies of rare fungal communities [56,105]. Allison et al. [106] found that fungal abundance correlates with variations in soil C–N ratios and nitrogen availability, potentially explaining how biochar and manure increase rare fungal abundance by altering rhizosphere C–N ratios and nutrient availability, thereby influencing rare fungal interactions. In this study, compared with M, MB resulted in a greater increase in the topological characteristics of rare fungal networks, further indicating that biochar is the primary variable influencing the response of rare fungal networks. Cyathus, Rhodotorula, and Auriculibulle, rare fungal genera serving as biomarkers, were significantly enriched in the rhizosphere under biochar and manure treatments. These three genera all belong to the Basidiomycota phylum. The Rhodotorula genus also exhibited significant enrichment in the rhizosphere where biochar or manure was applied individually. The genus Rhodotorula is common in soils and is known for its ability to survive under various abiotic stresses, typically associated with environments fluctuating between nutrient-poor (oligotrophic) and nutrient-rich (eutrophic) states [107]. The genus Cyathus represents typical saprophytic fungi that obtain nutrients by decomposing dead organic matter [108]. The genus Auriculibulle is less studied but belongs to the order Tremellales, where most genera are saprophytic fungi, such as the common edible fungi Tremella and Auricularia [109]. Bello et al. [110] similarly found that saprophytes exhibited a higher proportion of participation in co-occurrence networks observed in biochar treatments. One possible explanation is that the porous structure and large specific surface area of biochar provide a favorable habitat for saprophytic fungi to proliferate [111]. Furthermore, Basidiomycota typically utilize cellulose and lignin as carbon sources for metabolism [112]. Biochar, as a significant carbon material primarily derived from the pyrolysis of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [113], provides this carbon source for Basidiomycota. Yin et al.’s study [114] demonstrated that biochar promotes fungal degradation of cellulose in swine manure. Manure is rich in organic carbon and nutrients, providing direct and diverse carbon and energy sources for saprophytic fungi. This is a core factor driving their increased abundance. In synergy with biochar, this leads to a heightened abundance of rare saprophytic fungal taxa.

5. Conclusions

In the border-row rhizosphere, rare and abundant taxa responded differentially to various fertilization regimes. Although rare taxa communities exhibited lower abundances, they displayed greater richness and evenness, increased sensitivity to biochar and manure amendments, and cooperative rather than competitive dynamics. Under biochar and manure treatments, the rare bacterial communities were dominated by deterministic processes, whereas the rare fungal, abundant bacterial, and fungal communities were dominated by stochastic processes. Additionally, the network topology of the rare taxa was more complex than that of the abundant taxa. Rare taxa are a major component of microbial diversity, with narrower and less adaptable recipes as individuals, but they behave as potential seed banks as groups of higher diversity, resistant and adaptive to environmental changes and disturbances caused by exogenous biogenic carbon and feces. They play a significant role in maintaining the stability of the soybean–maize intercropping system. Our research underscores the ecological importance of rare taxa, and future fertilization strategies could be adjusted by leveraging these taxa.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020251/s1. Figure S1: Layout of experimental intercropping plots; Figure S2: Venn diagram of the total ASV, rare ASV, and abundant ASV counts under different treatments; Figure S3: The abundance–occupancy relationship of abundant and rare prokaryotic subpopulations in the rhizosphere; Figure S4: Taxonomic distributions of abundant and rare bacterial at the phylum level in the soil of different treatments; Figure S5: Taxonomic distributions of abundant and rare fungal communities at the phylum level in the soil of different treatments; Figure S6: The distribution of beta nearest taxon index (βNTI) for abundant and rare microbial taxa within different treatments; Figure S7: LeFSe analysis results for abundant bacterial communities under different treatment groups; Figure S8: LeFSe analysis results for rare bacterial communities under different treatment groups; Figure S9: LeFSe analysis results for abundant fungal communities under different treatment groups; Figure S10: LeFSe analysis results for rare fungal communities under different treatment groups; Figure S11: Relative abundance of fungal metabolic functions in soil across treatment groups; Table S1: Physicochemical properties of biochar and manure; Table S2: Fertilizer usage table; Table S3: Topological parameters of bacterial rhizosphere co-occurrence networks and random networks; Table S4: Topological parameters of fungal rhizosphere co-occurrence networks and random networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and W.Z.; methodology, R.M. and W.P.; formal analysis, W.Z. and Y.L.; investigation, W.Z. and R.M.; data curation, W.Z. and R.M.; visualization, W.Z., Y.L. and W.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and W.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and Y.L.; resources, G.S. and W.P.; project administration, G.S.; supervision, G.S. and W.P.; funding acquisition, H.L.; validation, W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Heilongjiang Province Postdoctoral Fund Project (Grant No. LBH-Z17017) as well as the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024MD753908).

Data Availability Statement

The original datasets and sequencing samples produced in this study are accessible from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, in compliance with institutional data transfer procedures.

Acknowledgments

This research received support from the Xiangyang Base of Northeast Agricultural University. All authors express their gratitude to the Hangzhou, China-based Lian Chuan-Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for providing technical support in the analysis of raw sequencing data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm that no competing financial interests or personal relationships exist that could have influenced the work presented in this paper.

Abbreviations

| β-NTI | β-nearest taxon index |

| β-MNTD | β-mean nearest taxon distance |

References

- Brooker, R.W.; Bennett, A.E.; Cong, W.-F.; Daniell, T.J.; George, T.S.; Hallett, P.D.; Hawes, C.; Iannetta, P.P.M.; Jones, H.G.; Karley, A.J.; et al. Improving intercropping: A synthesis of research in agronomy, plant physiology and ecology. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusinamhodzi, L.; Corbeels, M.; Nyamangara, J.; Giller, K.E. Maize–grain legume intercropping is an attractive option for ecological intensification that reduces climatic risk for smallholder farmers in central Mozambique. Field Crops Res. 2012, 136, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Feng, L.Y.; van der Werf, W.; Iqbal, N.; Khalid, M.H.B.; Chen, Y.K.; Wasaya, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ud Din, A.M.; Khan, A.; et al. Maize leaf-removal: A new agronomic approach to increase dry matter, flower number and seed-yield of soybean in maize soybean relay intercropping system. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Rahman, T.; Song, C.; Su, B.; Yang, F.; Yong, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, W. Changes in light environment, morphology, growth and yield of soybean in maize-soybean intercropping systems. Field Crops Res. 2017, 200, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Wei, W.; Zhang, S.; Keyhani, A.B.; Li, L.; Zhang, W. Border row effects on the distribution of root and soil resources in maize–soybean strip intercropping systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 233, 105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F.; Abd Razak, A.S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Aziz, M.A.A.; Krishnan, S.; Nasrullah, M. Comprehensive assessment of biochar integration in agricultural soil conditioning: Advantages, drawbacks, and future prospects. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2023, 132, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Sun, X.; Chen, G.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F.; Ping, S.; Lai, H.; Guo, H.; An, Y.; et al. Biochar addition mitigates asymmetric competition of water and increases yield advantages of maize–alfalfa strip intercropping systems in a semiarid region on the Loess Plateau. Field Crops Res. 2024, 319, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Six, J. Soil structure and microbiome functions in agroecosystems. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Xiong, X.; Zhu, H.; Xu, H.; Leng, P.; Li, J.; Tang, C.; Xu, J. Association of biochar properties with changes in soil bacterial, fungal and fauna communities and nutrient cycling processes. Biochar 2021, 3, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palansooriya, K.N.; Wong, J.T.F.; Hashimoto, Y.; Huang, L.; Rinklebe, J.; Chang, S.X.; Bolan, N.; Wang, H.; Ok, Y.S. Response of microbial communities to biochar-amended soils: A critical review. Biochar 2019, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shu, A.; Song, W.; Shi, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, S.; et al. Long-term organic fertilizer substitution increases rice yield by improving soil properties and regulating soil bacteria. Geoderma 2021, 404, 115287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Peng, F.; Gao, P. Long-term combined application of manure and chemical fertilizer sustained higher nutrient status and rhizospheric bacterial diversity in reddish paddy soil of Central South China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, K.K.; Misra, A.K.; Ghosh, P.K.; Hati, K.M. Effect of integrated use of farmyard manure and chemical fertilizers on soil physical properties and productivity of soybean. Soil Tillage Res. 2010, 110, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Durenkamp, M.; De Nobili, M.; Lin, Q.; Devonshire, B.J.; Brookes, P.C. Microbial biomass growth, following incorporation of biochars produced at 350 °C or 700 °C, in a silty-clay loam soil of high and low pH. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Barberán, A.; Li, Y.; Brookes Philip, C.; Xu, J. Bacterial Community Composition Associated with Pyrogenic Organic Matter (Biochar) Varies with Pyrolysis Temperature and Colonization Environment. mSphere 2017, 2, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abujabhah, I.S.; Bound, S.A.; Doyle, R.; Bowman, J.P. Effects of biochar and compost amendments on soil physico-chemical properties and the total community within a temperate agricultural soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 98, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Zhang, N.; Liang, C.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D. Divergent Co-occurrence Patterns and Assembly Processes Structure the Abundant and Rare Bacterial Communities in a Salt Marsh Ecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00320–e00322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Song, H.; Lei, Y.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C. Distinct co-occurrence patterns and driving forces of rare and abundant bacterial subcommunities following a glacial retreat in the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2019, 55, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zi, H.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Hu, B.; Jiang, Y. Contrasting assembly mechanisms and drivers of soil rare and abundant bacterial communities in 22-year continuous and non-continuous cropping systems. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Ren, C.; Yang, G.; Zhong, Z.; Han, X. Abundant and rare fungal taxa exhibit different patterns of phylogenetic niche conservatism and community assembly across a geographical and environmental gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 186, 109167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Wu, L.; Liu, W.; Ge, Y.; Mu, T.; Zhou, T.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Sun, X.; Luo, Y.; et al. Biogeography and diversity patterns of abundant and rare bacterial communities in rice paddy soils across China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 139116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cheng, K.; Li, K.; Jin, Y.; He, X. Deciphering the diversity patterns and community assembly of rare and abundant bacterial communities in a wetland system. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-L.; Ding, J.; Zhu, D.; Hu, H.-W.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Ma, Y.-B.; He, J.-Z.; Zhu, Y.-G. Rare microbial taxa as the major drivers of ecosystem multifunctionality in long-term fertilized soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 141, 107686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Dong, C.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Huang, F. Rare bacterial and fungal taxa respond strongly to combined inorganic and organic fertilization under short-term conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 203, 105639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Li, S.; Lang, X.; Huang, X.; Su, J. Rare species contribute greater to ecosystem multifunctionality in a subtropical forest than common species due to their functional diversity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 538, 120981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, W.; Wang, C.; Gao, M. Distinct distribution patterns and functional potentials of rare and abundant microorganisms between plastisphere and soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, G.; Jiao, S. Rare Species-Driven Diversity–Ecosystem Multifunctionality Relationships are Promoted by Stochastic Community Assembly. mBio 2022, 13, e00422–e00449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, M.; Eguíluz, V.M.; Duarte, C.M.; Voolstra, C.R. Rare symbionts may contribute to the resilience of coral–algal assemblages. ISME J. 2018, 12, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musat, N.; Halm, H.; Winterholler, B.; Hoppe, P.; Peduzzi, S.; Hillion, F.; Horreard, F.; Amann, R.; Jørgensen, B.B.; Kuypers, M.M.M. A single-cell view on the ecophysiology of anaerobic phototrophic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17861–17866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurm, V.; Geisen, S.; Gera Hol, W.H. A low proportion of rare bacterial taxa responds to abiotic changes compared with dominant taxa. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.D.J.; Neufeld, J.D. Ecology and exploration of the rare biosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, J.; Rong, X.; Peng, J.; Yin, L.; Zhou, X.; Luo, G. Enhanced productivity of maize through intercropping is associated with community composition, core species, and network complexity of abundant microbiota in rhizosphere soil. Geoderma 2024, 442, 116786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.-X. Wekemo Bioincloud: A user-friendly platform for meta-omics data analyses. iMeta 2024, 3, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kembel, S.W.; Cowan, P.D.; Helmus, M.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Morlon, H.; Ackerly, D.D.; Blomberg, S.P.; Webb, C.O. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ning, D. Stochastic Community Assembly: Does It Matter in Microbial Ecology? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, e00002-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levins, R. Evolution in Changing Environments: Some Theoretical Explorations. (MPB-2); Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Geange, S.W.; Pledger, S.; Burns, K.C.; Shima, J.S. A unified analysis of niche overlap incorporating data of different types. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2011, 2, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Nuccio, E.E.; Shi, Z.J.; He, Z.; Zhou, J.; Firestone, M.K. The interconnected rhizosphere: High network complexity dominates rhizosphere assemblages. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Meijenfeldt, F.A.B.; Hogeweg, P.; Dutilh, B.E. A social niche breadth score reveals niche range strategies of generalists and specialists. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.I.; Barabás, G.; Bimler, M.D.; Mayfield, M.M.; Miller, T.E. The evolution of niche overlap and competitive differences. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.-L.; Gulbahce, N.; Loscalzo, J. Network medicine: A network-based approach to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8577–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.; Lu, T.; Qian, H.; Liu, Y. Machine learning models reveal how biochar amendment affects soil microbial communities. Biochar 2023, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Q.; Xu, M.; Zheng, J.; Bian, R.; Zhang, X.; Pan, G. Biochar improves soil organic carbon stability by shaping the microbial community structures at different soil depths four years after an incorporation in a farmland soil. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 5, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Mao, W.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Sun, W. Response of soil microbial ecological functions and biological characteristics to organic fertilizer combined with biochar in dry direct-seeded paddy fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xu, W.; Dong, J.; Yang, T.; Shangguan, Z.; Qu, J.; Li, X.; Tan, X. The effects of biochar and its applications in the microbial remediation of contaminated soil: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, L.; Wang, S.; Yu, G.; Miao, A. Responses of abundant and rare prokaryotic taxa in a controlled organic contaminated site subjected to vertical pollution-induced disturbances. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, G.; Chen, W.; Lu, Y. Dominant role of abundant rather than rare bacterial taxa in maintaining agro-soil microbiomes under environmental disturbances. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhang, C. Rare bacterial biosphere is more environmental controlled and deterministically governed than abundant one in sediment of thermokarst lakes across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 944646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Huang, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Liao, H.; Lv, Z.; Chen, W.; Luo, X.; Hao, X. Distinct Responses of Rare and Abundant Microbial Taxa to In Situ Chemical Stabilization of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil. mSystems 2021, 6, e01040-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Kunhikrishnan, A.; Thangarajan, R.; Kumpiene, J.; Park, J.; Makino, T.; Kirkham, M.B.; Scheckel, K. Remediation of heavy metal(loid)s contaminated soils—To mobilize or to immobilize? J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 266, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Gross, C.D.; Chen, X.; Bork, E.W.; Carlyle, C.N.; Chang, S.X. Manure and its biochar affect activities and stoichiometry of soil extracellular enzymes in croplands. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 3286–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Razavi, B.S.; Yao, S.; Hao, C.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Tian, J. Contrasting mechanisms of nutrient mobilization in rhizosphere hotspots driven by straw and biochar amendment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 187, 109212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, L.; Cai, Z.J.; Chen, J.; Shen, R.F. Different contributions of rare microbes to driving soil nitrogen cycles in acidic soils under manure fertilization. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 196, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, Q.; de Vries, W.; Ros, G.H.; Chen, X.; Muneer, M.A.; Zhang, F.; Wu, L. Effects of soil amendments on soil acidity and crop yields in acidic soils: A world-wide meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshoux, M.; Sadet-Bourgeteau, S.; Gentil, S.; Prévost-Bouré, N.C. Effects of biochar on soil microbial communities: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Í.V.d.; Fregolente, L.G.; Pereira, A.P.d.A.; Nascimento, C.D.V.d.; Mota, J.C.A.; Ferreira, O.P.; Sousa, H.H.d.F.; Silva, D.G.G.d.; Simões, L.R.; Souza Filho, A.G.; et al. Biochar as a carbonaceous material to enhance soil quality in drylands ecosystems: A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, T.; Chang, S.X.; Jiang, X.; Song, Y. Biochar increases soil microbial biomass but has variable effects on microbial diversity: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Jiang, Q.; Akhtar, K.; Luo, R.; Jiang, M.; He, B.; Wen, R. Biochar and manure co-application improves soil health and rice productivity through microbial modulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Xu, M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Wen, S.; Gao, S. Effectiveness of crop straws, and swine manure in ameliorating acidic red soils: A laboratory study. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 2893–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smebye, A.; Alling, V.; Vogt, R.D.; Gadmar, T.C.; Mulder, J.; Cornelissen, G.; Hale, S.E. Biochar amendment to soil changes dissolved organic matter content and composition. Chemosphere 2016, 142, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Harindintwali, J.D.; Cui, H.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, Q.; Chang, S.X.; Wang, F.; Yang, J. Decoupled fungal and bacterial functional responses to biochar amendment drive rhizosphere priming effect on soil organic carbon mineralization. Biochar 2024, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Ning, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. Biochar and Manure Co-Application Increases Rice Yield in Low Productive Acid Soil by Increasing Soil pH, Organic Carbon, and Nutrient Retention and Availability. Plants 2024, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Tran, P.Q.; Kieft, K.; Anantharaman, K. Genome diversification in globally distributed novel marine Proteobacteria is linked to environmental adaptation. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2060–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, N.; Wang, T.; Kuzyakov, Y. Rhizosphere bacteriome structure and functions. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, N.; Megrian, D.; Witwinowski, J.; Adam, P.; Poppleton, D.; Borrel, G.; Beloin, C.; Gribaldo, S. Genome-wide analysis of the Firmicutes illuminates the diderm/monoderm transition. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Wakelin, S.; Huygens, F.; Hargreaves, M. Firmicutes dominate the bacterial taxa within sugar-cane processing plants. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Basu, A.; Ahmad, I.; Sayyed, R.Z.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Suriani, N.L. Recent Understanding of Soil Acidobacteria and Their Ecological Significance: A Critical Review. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longcore, J.E.; Simmons, D.R. Chytridiomycota. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Li, Y.; Yao, H. Biochar Amendment Stimulates Utilization of Plant-Derived Carbon by Soil Bacteria in an Intercropping System. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, H.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Gundale, M.J.; Zou, X.; Ruan, H. Global meta-analysis reveals positive effects of biochar on soil microbial diversity. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoncourt, C.; Chantigny, M.H.; Angers, D.A.; Maillard, É.; Halde, C. Animal manure application promotes nitrogen and organic carbon accumulation in soil organic matter fractions: A global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 996, 180097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, É.; Angers, D.A. Animal manure application and soil organic carbon stocks: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Li, Z.; Song, C.; Dai, H.; Shao, Y.; Luo, H.; Huang, D. Rare taxa as the microbial taxa more sensitive to environmental changes drive alterations of daqu microbial community structure and function. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Lu, Y. Abundant fungi adapt to broader environmental gradients than rare fungi in agricultural fields. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4506–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Lu, Y. Soil pH and temperature regulate assembly processes of abundant and rare bacterial communities in agricultural ecosystems. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wu, H.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Rensing, C.; Lin, W. The combination of biochar and PGPBs stimulates the differentiation in rhizosphere soil microbiome and metabolites to suppress soil-borne pathogens under consecutive monoculture regimes. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 14, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peduruhewa, J.H.; Brown, R.W.; Chadwick, D.R.; Griffiths, R.I.; Fu, H.; Bian, H.; Sheng, L.; Ma, Q.; Jones, D.L. Biochar reshapes soil bacterial community composition and survival strategies: A meta-analysis revealing trade-offs between microbial stability and functional complexity. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Wilkinson, D.M. The biogeography of abundant and rare bacterioplankton in the lakes and reservoirs of China. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2068–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Logares, R.; Huang, B.; Hsieh, C.-h. Abundant and rare picoeukaryotic sub-communities present contrasting patterns in the epipelagic waters of marginal seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cong, M.; Yan, H.; Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Tang, G.; Xu, W.; Zhu, X.; Jia, H. Effects of biochar addition on aeolian soil microbial community assembly and structure. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 3829–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Qi, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H. Soil nematode community and crop productivity in response to 5-year biochar and manure addition to yellow cinnamon soil. BMC Ecol. 2020, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]