Abstract

Carotenoids are a class of C40 isoprenoid-derived fat-soluble pigments that play vital roles in plant physiology and human health and serve as precursors for several biologically critical regulatory molecules. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) are key enzymes that catalyze the selective oxidative cleavage of carotenoids into apocarotenoids, thereby significantly influencing plant development and responses to abiotic stress. Although extensive research has been conducted on many model species, comprehensive studies on the StCCD gene family in potato remain limited. In this study, we conducted a genome-wide analysis to identify and characterize the CCD gene family in potato. Phylogenetic and structural analyses classified the 17 StCCD genes into six distinct subfamilies, which are distributed across five chromosomes of the genome. Analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements revealed that the promoters of most StCCD genes contain various elements associated with light responsiveness, stress signaling, and phytohormone regulation. Molecular docking analysis indicated that CCD proteins exhibit distinct substrate specificity in their binding to carotenoids and intermediate products. The expression profiling of StCCD genes uncovered pronounced specificity in their expression, which was evident across tissues, throughout tuber maturation, and following exposure to abiotic stresses and hormonal applications. This specificity strongly implicates these genes in the regulation of developmental processes and stress adaptation mechanisms. This study provides a comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic overview of the CCD gene family in potato, establishing a foundation for functional characterization of individual genes in the future.

1. Introduction

Carotenoids represent a major class of C40 isoprenoid fat-soluble pigments that are ubiquitously distributed in animals, plants, algae, fungi, and bacteria [1]. Comprising over 750 structurally diverse compounds, carotenoids are broadly classified into carotenes and xanthophylls, imparting yellow, orange, and red pigmentation to fruits and flowers [2,3]. As accessory photosynthetic pigments integral to photosynthetic apparatus, carotenoids are predominantly localized in chloroplasts and chromoplasts, where they facilitate essential roles in photosynthesis and photoprotection [4,5]. Moreover, carotenoids function as potent antioxidants, mitigating reactive oxygen species generated under environmental stress and reducing the incidence of chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and age-related macular degeneration [3,6]. Additionally, carotenoids act as precursors for key regulatory molecules, including the phytohormones abscisic acid (ABA) and strigolactones (SLs), which orchestrate stress responses and developmental processes in plants [7].

While previous research has predominantly focused on carotenoid biosynthesis, the degradation pathways of these compounds have received comparatively less attention. Carotenoids contain a central chain with multiple conjugated double bonds that can be selectively cleaved by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs), yielding a diverse array of apocarotenoids [8,9]. CCDs constitute a family of non-heme iron (Fe2+)-dependent enzymes that catalyze the oxidative cleavage of conjugated carbon–carbon double bonds in carotenoids, thereby generating various apocarotenoid derivatives [10]. In plants, the CCD gene family is divided into two main subfamilies: the nine-cis-epoxycarotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (NCEDs) and the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) [11]. The first carotenoid-cleaving enzyme, NCED1, was isolated from the viviparous14 (vp14) maize mutant [12,13]. In Arabidopsis thaliana L., nine CCD enzymes have been identified, including four CCDs (CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, and CCD8) and five NCEDs (NCED2, NCED3, NCED5, NCED6, and NCED9) [14]. All CCD proteins contain the retinal pigment epithelium membrane protein (RPE65) domain, a hallmark structural feature of carotenoid-cleaving enzymes [15,16]. Despite this common domain, sequence similarity among CCD family members is generally low, with the exception of four highly conserved histidine residues and a limited number of glutamate residues. Although CCDs and NCEDs belong to the same gene family, they share relatively low sequence homology and exhibit distinct enzymatic activities and substrate preferences. Certain CCD enzymes (CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, and CCD8) demonstrate specificity toward particular carotenoid or apocarotenoid substrates, whereas NCEDs display broader substrate promiscuity, as observed in heterologous expression systems. CCD1 and CCD4 catalyze the formation of flavor volatiles and aroma compounds across various species [17,18,19]. In contrast, CCD7 and CCD8 are involved in the biosynthesis of strigolactones, a class of phytohormones that inhibit shoot branching [20,21,22]. NCEDs primarily catalyze the stereospecific cleavage of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoids, yielding apo-12′-epoxycarotenal (C25) and xanthoxin (C15), the latter being a key precursor in abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis. This reaction represents a critical rate-limiting step in the ABA biosynthetic pathway [23,24].

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is the world’s third most important non-cereal crop and is extensively cultivated across diverse geographical regions. It serves as a valuable source of carbohydrates, dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, carotenoids, proteins, and antioxidants [25]. Beyond yield assurance, elevated carotenoid content enhances both the sensory quality and nutritional value of potato tubers, while also contributing to improved resilience under environmental stress conditions. In this study, we conducted a genome-wide analysis to identify members of the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) gene family in potato. We isolated the StCCD genes and compared its genomic structure with those of homologous genes in related species and representative plants, including Arabidopsis, tomato, and pepper. Furthermore, we performed a comprehensive examination of gene structures, duplication events, and cis-regulatory elements within the potato CCD gene family. Additionally, RNA-seq data and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was employed to assess the expression patterns of CCD genes across various tissues and under salt stress conditions, thereby elucidating their potential roles in developmental processes and abiotic stress responses. Our findings provide critical insights that will facilitate future investigations into the biological functions of CCD genes in potato.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Two potato cultivars, Chuanyu No.50 (CY50) and Huasong No.7 (HS7), were cultivated in pots filled with a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of soil and vermiculite at the experimental station in Chengdu, China (103°86′17″ E, 30°70′52″ N) in 2024. To analyze expression patterns of StCCD genes, different developmental stages tuber tissues (tuber formation, bulking, and maturation) of CY50 and HS7, were collected and frozen at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction.

2.2. Identification and Sequence Analysis of CCD Gene Family Members in Potato

The genomic data for potato, Arabidopsis, tomato and pepper were retrieved from the Ensembl database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html). A Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile (PF03055) corresponding to the conserved domain of CCD genes was obtained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org). Using the HMMER software (v3.1) implemented in TBtools v1.119, an HMMsearch was performed against the potato protein sequence database to identify potential CCD genes. An e-value threshold of 1.0 × 10−11 was applied to ensure the retrieval of reliable CCD domain sequences. Finally, the integrity of the TCP domains were assessed using the NCBI-CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) and EBI-Interpro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/). Multiple sequence alignment was carried out using ClustalW (v2.0).

To maintain gene sequence integrity, the longest transcript isoform was chosen as the representative sequence for each of these genes, and redundant sequences and alternative splice isoforms were removed. Then chromosomal locations, exon numbers, genomic sequences, protein sequences, and coding sequences of the potato CCD genes were acquired from Phytozome (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/). The molecular weights and theoretical isoelectric points (PIs) of all StCCD proteins were predicted using ExPASy (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/). Based on their genomic coordinates, the chromosomal positions of the StCCD genes were mapped and visualized.

2.3. Sequence Analysis and Structural Characterization

Gene exon/intron structures were examined and graphically represented using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS, https://gsds.gao-lab.org/). Conserved motifs within the protein sequences were identified via the web-based tool Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME, https://meme-suite.org/meme/) with the number of motifs set to 10 and the expected motif distribution configured as Zero or One Occurrence Per Sequence (ZOOPs). The resulting gene structures and motif architectures were visualized using TBtools-II (v2.153) [26].

2.4. Sequence Alignments and Phylogenetic Analysis

We selected the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana L., as well as tomato, eggplant, pepper and potato, which belong to the same family (Solanaceae), for evolutionary analysis together. Protein sequences of Arabidopsis AtCCDs were retrieved from the Arabidopsis information resource (TAIR; http://www.arabidopsis.org), tomato SlCCDs from the Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/), eggplant SmCCDs from the Sol Genomics Network (http://eggplant-hq.cn/Eggplant/home/index) and pepper CaCCDs from Ensembl Plants (https://plants.ensembl.org/index.html). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal W under default parameters. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method in TBtools v2.122, supported by 1000 bootstrap replicates. The resulting tree was further annotated and visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL; https://itol.embl.de/).

2.5. Analysis of Cis-Element

To investigate cis-regulatory elements for StCCD genes, a 2000 bp genomic region upstream of the start codon for each CCD gene was extracted from the Phytozome database. Then these promoter sequences were analyzed using the PlantPAN website (http://plantpan.itps.ncku.edu.tw/plantpan4/) and the PlantCARE website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). Prediction results of cis-elements are presented in the form of a heatmap. And GO annotation analysis was conducted using the AgriGO2.0 program (http://systemsbiology.cau.edu.cn/agriGOv2/index.php).

2.6. Synteny Analysis and Chromosome Localization

Syntenic relationships among CCD genes across different species were identified using MCScanX [27], with results visualized through TBtools [26]. The non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates were computed using MEGA to assess evolutionary selection pressures.

2.7. Protein Structure Prediction and Virtual Docking

The two-dimensional (2D) structures of various carotenoids—including all-trans-violaxanthin, all-trans-neoxanthin, phytoene, lycopene, ζ-carotene, 8-apo-β-carotenal, 9-cis-neoxanthin, 9-cis-violaxanthin, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, and zeaxanthin—were retrieved from the ChemSpider database for molecular docking analysis. These ligand structures were subsequently converted into three-dimensional (3D) format using ChemDraw 23 software, followed by energy minimization to optimize their geometries. The resulting structures were saved as mol2 format for further investigation. The three-dimensional structures of the StCCD proteins were predicted using AlphaFold3. Each predicted protein structure was opened in PyMol, where solvent molecules were removed by executing the command remove solvent, and any bound organic ligands were eliminated with the command remove organic. The cleaned protein structures were then saved as .pdb format.

Molecular docking was performed between the processed macromolecular receptors (StCCD proteins) and the small-molecule ligands (carotenoids) employing AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 Hydrogen atoms were added to the protein structures, indicated visually by the appearance of white stick models. Ligand molecules were imported separately; if a ligand was initially positioned too close to the protein, it was manually moved to a distant location to prevent interference with active site identification, and likewise saved as pdbqt format. The secondary structure of the protein was displayed, where the center coordinates and dimensions were adjusted to fully encompass the predicted binding pocket. The grid parameters were saved as a .gpf file. Finally, molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina under a semi-flexible docking protocol. The command-line interface was employed within the target working directory to execute the docking process, which generated 20 docking poses along with their corresponding RMSD values. The results were visualized and analyzed using PyMol, and a heatmap visualizing the results was generated using TBtools.

2.8. Expression Pattern Analysis of StCCD Genes in Potato

The expressions of StCCD genes in 13 tissues (root, stem, leaf, petiole, petals, stamens, flower, fruit, stolons, Young tubers, and mature tuber) in DM potato and the whole plant in vitro that was treated for abiotic stress (salt treatment: 150 mM NaCl, 24 h; mannitol-induced drought stress: 260 M mannitol, 24 h; heat treatment: 35 °C, 24 h; wounding treatment) and hormone treatments [benzylaminopurine (BAP): 10 M, 24 h; abscisic acid (ABA): 50 M, 24 h; indole acetic acid (IAA): 10 M, 24 h; gibberellic acid (GA3): 50 M, 24 h]) were analyzed based on the Illumina RNA-seq data that was downloaded from the PGSC (The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium). TBtools software was used to draw the heat map.

2.9. Quantification of Carotenoids

Carotenoid extraction was performed using a solvent mixture of acetone (purity > 99.5%, Kelong, Chengdu, China) and petroleum (color intensity < 10, Kelong, Chengdu, China) ether (4:1, v/v) as the extraction solution. Fresh potato tubers were washed, peeled, and 1.0 g of tuber flesh was homogenized in a mortar with 4 mL of the extraction solution under light-protected conditions. The resulting homogenate was transferred to a 10 mL centrifuge tube, mixed with an additional 4 mL of extraction solvent, and thoroughly vortexed. The tube was then incubated in a constant-temperature water bath at 50 °C for 30 min while maintaining protection from light. After incubation, the volume was adjusted with extraction solvent, and the sample was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, and its absorbance was measured at 440 nm. The carotenoid content was calculated according to the following formula: Carotenoid content (μg/100 g) = (100,000 × A × V)/(2500 × m), where A represents the absorbance value, V is the total volume of the supernatant (mL), and m denotes the mass of the sample (g).

2.10. Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with the FastPure Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme, RC401) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using random primers and the PrimeScript II First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Dalian, China, 6210A). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Dalian, China) on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). Gene-specific primers and the potato Actin gene used as an internal control are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCT) method [28].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

For all multiple comparisons, the significance of the difference between different groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA along with LSD multiple comparison test at a significance level of 0.01 and 0.05 using SPSS 24.0. * and ** above the bars indicate significantly different groups (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01).

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of CCD Family Genes in Potato

Candidate genes were identified through Hidden Markov Model (HMM)-based screening and subsequent comparative analysis. A total of 86 amino acid sequences were retrieved from the potato genome. After selecting representative isoforms among alternative splicing variants, 17 sequences were retained for further analysis, including 14 belonging to the CCD subfamily and 3 to the NCED subfamily (Table 1). Bioinformatic analysis of the encoded StCCD proteins revealed that their lengths range from 175 to 1115 amino acids, with molecular weights varying between 19.80 kDa (StCCD13) and 127.12 kDa (StCCD11), and theoretical isoelectric points (PI) ranging from 4.99 (StCCD14) to 8.75 (StCCD13). Subcellular localization predictions indicated that StCCD proteins are targeted to multiple compartments, including the chloroplast, cytoplasm, peroxisome, and nucleus. Notably, 58.8% of the StCCD proteins were predicted to localize to the chloroplast, and 29.4% to the cytoplasm, while StCCD10 and StCCD15 were specifically assigned to the peroxisome and nucleus, respectively.

Table 1.

Characterization of CCD gene family members in potato. CDS, coding sequence, bp, base pair; Chr, chromosome; PI, isoelectric point; GRAVY, grand average of hydropathicity.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the StCDD Family Genes

To elucidate the evolutionary relationships among CCD proteins, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method based on 65 CCD protein sequences from potato, Arabidopsis and three Solanaceae plants (tomato, eggplant and pepper) (Figure 1). The results demonstrated that the CCD proteins were clustered into two distinct subfamilies: CCD and NCED. The CCD subfamily comprised five clades-CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, CCD8, and CCDL-while the NCED subfamily contained three members: NCED1, NCED3, and NCED6. These findings are consistent with previous reports in Arabidopsis and tobacco [29]. Notably, Arabidopsis contains a single protein in each of the CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, and CCD8 subfamilies, whereas potato possesses three CCD1 members, five CCD4 members, and three CCDL members. It is noteworthy that CCD proteins from different species exhibit closer phylogenetic relationships with orthologs of the same type than with other CCD types within the same species, suggesting a high degree of functional and sequence conservation within each CCD type across species.

Figure 1.

The phylogenetic analysis of the CCD family members of potato (St), Arabidopsis (At), tomato (Sl), eggplant (Sm) and pepper (Ca). The CCD proteins of potato, Arabidopsis, tomato, eggplant and pepper were specifically identified using red squares, yellow stars, green triangles, blue circles and black triangles. The analyses were performed using TBtools software with the neighbor-joining method (NJ), allowing for comprehensive sights into the evolutionary patterns and relationships among these species.

3.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of CDD Family Genes in Potato

Based on the coding sequences and the whole-genome data, the exon-intron structures of the StCCD gene family were analyzed using the online tool GSDS 2.0, and schematic representations of each gene were generated (Figure 2). Structural analysis revealed that the gene lengths vary from 500 bp to 17,000 bp, with StCCD14 being the longest (16,925 bp) and StCCD13 the shortest (525 bp) (Table 1). The number of introns ranged from 0 to 23. Among the 17 StCCDs, members of the CCD4 subfamily (CCD2, CCD4, CCD5, CCD13, and CCD16) and the NCED subfamily (StNCED1, StNCED3, and StNCED6) contained 0–3 introns, whereas genes in other subfamilies possessed 5 to 23 introns. These structural features are consistent with their phylogenetic relationships, as genes clustered within the same clade exhibited similar exon-intron architectures and comparable numbers of introns in their coding sequences.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram for gene structure of CCDs and conserved motifs analysis of CCD proteins in potato. (A) Gene structure of CCD genes. Blue boxes indicate the untranslated 5′/3′ regions; yellow boxes indicate CDS; black lines represent introns. (B) Distribution of conserved motifs within the CCD proteins. The differently colored boxes represent different bases, and the number of conserved domains was set to 10 at most. The graph was connected to a phylogenetic tree on the left of (A,B).

To further characterize the StCCD proteins, we identified conserved motifs using the MEME suite. A total of eight conserved motifs were predicted. As illustrated in Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S1, most genes within the same phylogenetic branch shared identical motif compositions and arrangements. Motifs 1, 2, 4, and 7 were conserved across all StCCD proteins. Notably, motif 8 was present in all except StCCD14. These findings suggest that proteins within the same subfamily possess conserved motif architectures, which may underlie their functional similarities. Furthermore, the motif conservation reflects functional differentiation and evolutionary conservation within this gene family.

3.4. Analysis of Cis-Elements in the Promoter Regions of CCD Family Genes in Potato

Cis-acting elements in gene promoters serve as binding sites for various transcription factors and play a crucial role in transcriptional regulation [12]. To investigate the transcriptional regulation of StCCD genes during plant development and stress responses, we analyzed the promoter sequences of each gene using the PlantCARE database. The results revealed that the identified cis-acting elements were predominantly associated with light responsiveness, hormone signaling, and stress responses (Figure 3), implying that the expression of StCCD genes is intricately regulated by diverse environmental and hormonal cues. Hormone-related elements included the TCA-element (involved in salicylic acid response), ABRE (abscisic acid response), GARE-motif (gibberellin response), AuxRR-core and TGA-elements (auxin response), and TGACG-motif (methyl jasmonate response). Notably, abscisic acid response elements (ABRE) were the most abundant, suggesting that most StCCD genes are potentially involved in ABA-mediated processes. In addition, a variety of stress-related cis-elements were identified, such as the anaerobic induction element (ARE), low-temperature responsiveness element (LTR), drought-inducible element (MBS), as well as defense and stress response elements (TC-rich repeats and W-box). Furthermore, a light-responsive G-box element was detected in the promoters of all StCCD genes. While GO enrichment analysis of the StCCD family revealed their primary localization to cytoplasmic and organellar compartments, along with significant enrichment in carotenoid and terpenoid metabolic processes (Supplementary Figure S2). These functional annotations are consistent with their role in maintaining redox homeostasis in plants.

Figure 3.

Analysis of cis-elements within the promoter of CCD genes family members in potato. (A) The number of cis-elements in CCDs promoter. Based on the functional annotation, the cis-acting elements were classified into three main types: plant development and growth environment response, light-responsive, phytohormone-responsive and others. (B) A detailed examination of the StCCD gene family revealed diverse cis-element structures, each denoted by a unique color code for clarity.

3.5. Chromosome Distribution and Synteny Analysis of CCD Family Genes in Potato

To determine the chromosomal distribution of CCD genes in potato, the genomic locations of all StCCD family members were analyzed. The 17 identified StCCD genes were distributed across five of the twelve potato chromosomes, specifically chromosomes 1, 5, 7, 8, and 11, exhibiting an uneven distribution pattern. Chromosome 8 harbored the highest number of StCCD genes, with a total of 10 (approximately 58.8%), followed by chromosome 1 with four genes. The remaining chromosomes each contained only one StCCD gene. Furthermore, all StCCD genes were located in close physical proximity on their respective chromosomes. Analysis of the potato functional genomic database revealed the exon–intron structures of the StCCD genes (Figure 4). In general, fewer StCCD genes were located in the central regions of the chromosomes, whereas a greater concentration was observed toward the telomeric regions.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the chromosomal distributions and duplication of the CCD genes in the potato genome. (A) CCD genes distribution map on 12 potato chromosomes. The scale on the left indicates the chromosome length. The scale is in megabases (Mb). Tandemly duplicated genes were marked by colourful boxes. (B) Genomic locations and segmental duplication of the StCCD genes. The red lines link paralogous CCD genes.

Gene duplication serves as an important evolutionary mechanism contributing to functional diversification. To investigate the expansion of the StCCD gene family, duplication events were analyzed using the MCScanX program. The analysis identified seven tandem duplication events involving 11 StCCD genes. Among these, chromosome 2 contained one tandem duplication cluster (CCD1/CCD14/CCD15), and chromosome 8 contained five tandem duplication clusters (CCD2/CCD5/CCD13, CCD4/CCD16, and CCD10/CCD11/CCD12) (Figure 4A). Additionally, one pair of segmentally duplicated genes (comprising two StCCD genes) was detected (Figure 4B). These findings suggest that gene duplication events have contributed to the expansion of the StCCD family. Both tandem and segmental duplications played crucial roles in this process. To assess the selective pressures acting on these duplication events, the nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates were calculated using the Ka/Ks Calculator 2.0. The Ka/Ks ratios for tandemly duplicated gene pairs ranged from 0.2682 to 0.5385, while the segmentally duplicated pair had a Ka/Ks value of 0.2009 (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). All calculated Ka/Ks values were less than 1, indicating that the StCCD gene family has likely undergone purifying selection during evolution.

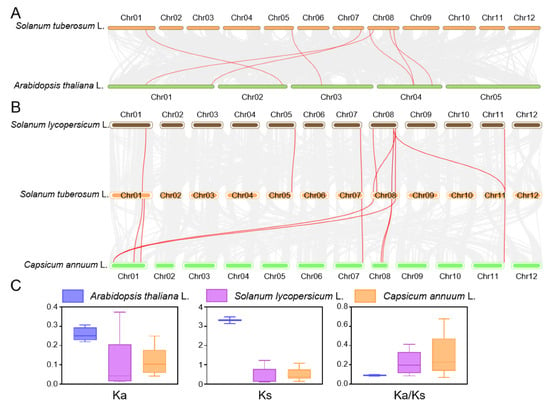

To further elucidate the evolutionary history of the StCCD gene family, synteny analyses were conducted between potato and three other species (Arabidopsis, tomato, and pepper) using MCScanX (Figure 5A,B). The analysis revealed seven orthologous pairs between potato and Arabidopsis, with Ka/Ks values ranging from 0.0848 to 0.0976; ten orthologous pairs between potato and tomato, with Ka/Ks values between 0.0870 and 0.4114; and eight orthologous pairs between potato and pepper, with Ka/Ks values ranging from 0.0346 to 0.2747 (Figure 5C and Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 5.

Synteny analysis of CCD genes between potato, Arabidopsis, tomato and pepper. (A) Synteny analysis of potato and Arabidopsis. (B) Synteny analysis of potato and Solanaceous plant. (C) Average values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks of duplicated CCD genes, respectively. The gray lines in the background indicate the collinear regions in the genomes of these species, the highlighted red lines indicate the collinear CCDs genes pairs in (A,B).

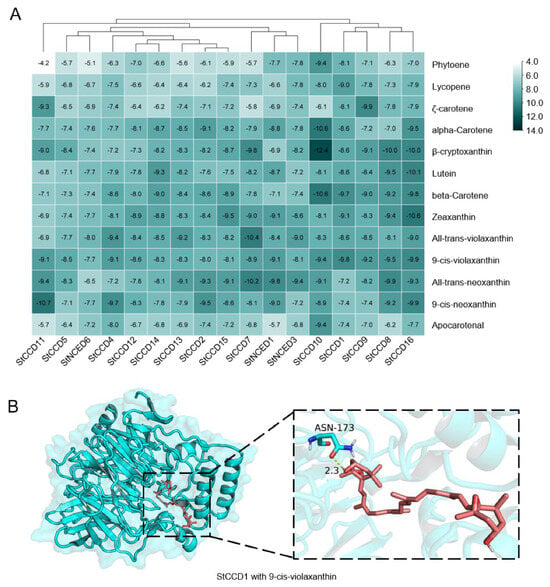

3.6. Molecular Docking for StCCD Proteins and Carotenoids

To investigate the cleavage potential of StCCD proteins toward carotenoids and their intermediate products, molecular docking was performed between the proteins encoded by the nine hub genes and thirteen core carotenoids along with key intermediates (Figure 6, Supplementary Figure S3 and Supplementary Table S4). All CCD family proteins exhibited high binding affinity for carotenoids and their derivatives, with affinities lower than −7 kcal/mol (Figure 6A). Notably, the strongest interaction was observed between StCCD10 and β-cryptoxanthin, with an affinity value of −12.4 kcal/mol. Among the potential substrates analyzed, StCCD10, StCCD1, StCCD9, StCCD8, and StCCD16 displayed pronounced affinity for β-cryptoxanthin, β-carotene, 9-cis-violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin. In contrast, StCCD7, StNCED1, and StNCED3 showed a binding preference for all-trans-violaxanthin, 9-cis-violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin, while the remaining StCCD proteins interacted more strongly with β-cryptoxanthin and 9-cis-neoxanthin. These findings collectively indicate that CCD proteins exhibit distinct substrate specificity in their binding to carotenoids and intermediate products.

Figure 6.

Results of molecular docking for StCCD proteins. (A) A clustered heatmap showing the affinities between each pair of docking conformations. (B) Molecular docking diagrams showing the putative docking models between StCCD1 and 9-cis-violaxanthin.

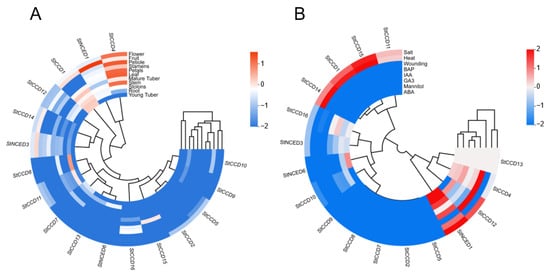

3.7. Expression Profiles of StCCD Genes in Different Tissues and Expression Patterns of StCCD Genes Under Abiotic Stress

To investigate the putative roles of StCCD genes in potato growth and development, RNA-seq data were obtained from the PGSC and analyzed to determine the expression patterns of the 17 StCCD genes across various tissues and organs. The expression of StCCD gene family members was detected in multiple tissues, implying functional diversification (Figure 7A). Notably, StCCD1 and StCCD4 exhibited comparatively high expression levels across most tissues, suggesting their fundamental roles in potato growth and development. In addition, StCCD14, StNCED1, and StNCED3 were expressed in potato fruits, indicating their potential importance during reproductive development. Several StCCDs displayed tissue-specific expression patterns: StCCD8 and StCCD11 were predominantly expressed in roots, StCCD15 was specifically expressed in leaves, and StCCD14, StNCED1, and StNCED3 were notably expressed in fruits, implying their specialized functions in the development of respective tissues.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the expression patterns of StCCD genes in different tissues and kinds of treatments. (A) Expression profile analysis in different tissues (root, stem, leaf, petiole, petals, stamens, flower, fruit, stolons, young tubers, and mature tuber) in double haploid (DM) potato based on RNA-seq data. (B) Expression profile analysis in different treatments. Abiotic stress: salt treatment: 150 mM NaCl, 24 h; mannitol-induced drought stress: 260 M mannitol, 24 h; heat treatment: 35 °C, 24 h; wounding treatment; and hormone treatments: benzylaminopurine (BAP): 10 M, 24 h; abscisic acid (ABA): 50 M, 24 h; indole acetic acid (IAA): 10 M, 24 h; gibberellic acid (GA3): 50 M, 24 h.

To further elucidate the response of StCCD genes to abiotic stresses and phytohormonal treatments, we analyzed publicly available RNA-seq data from the PGSC. As illustrated in Figure 7B, the expression profiles of StCCD genes under abiotic stress conditions could be categorized into three distinct groups based on their expression patterns. Among these, StCCD4 and StNCED1 exhibited significant transcriptional upregulation under treatments including ABA, GA3, BAP, drought (simulated by mannitol), wounding, and salt, suggesting their potential involvement in mediating abiotic stress tolerance in potato. In contrast, the expression of StCCD1, StCCD11, StCCD14, and StCCD15 was induced under heat and salt stresses, while StCCD12 showed moderate upregulation in response to drought, wounding, and salt treatments, indicating their possible roles in stress adaptive responses.

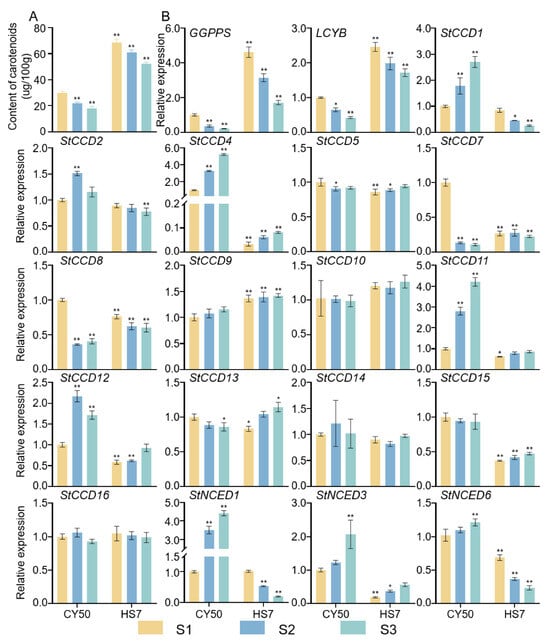

3.8. Expression Profiles of StCCD Genes in Pigmented Potato Cultivars

To identify the potential functions of StCCD genes in flavonoid biosynthesis of potato, the expression patterns of the StCCD genes in tuber tissues (white and yellow) of tetraploid pigmented potato cultivars were analyzed. As shown in Figure 7, the carotenoids content in the tubers of Chuanyu 50 (CY50) was significantly higher than that of HuaSong 7 (HS7) at all developmental stages, including the tuber formation stage (S1), the tuber bulking stage (S2), and the tuber maturation stage (S3) (Figure 8A). Then we detected the expression of StCCDs genes in different developmental stages of CY50 and HS7 (Figure 8B). There were six StCCD genes (StCCD1, StCCD4, StCCD11, StNCED1, StNCED3, and StNCED6) which showed similar expression patterns at different stages of tuber development, and the expression levels in both CY50 and HS7 exhibited a continuously decreasing trend; however, the expression level in the CY50 was consistently higher than that in the HS7. While we noticed that the induced expression levels of two pivotal genes related to the synthesis pathway of carotenoids, StGGPPS, and StLCYB, were higher in HS7 than in CY50, which were to that of the previous six genes. Therefore, these StCCD genes might play a role in the process of carotenoid degradation during all tuber development stages. In particular, StCCD7 and StCCD8 were highly expressed in S1 of CY50 than other stages of CY50 and HS7, this finding suggests that StCCD7 and StCCD8 are associated with carotenoid degradation only in early tuber development stage. In addition, StCCD15 was steadily expressed during three stages of CY50 and HS7, however the expression level in CY50 is higher overall than that in HS7. The other genes, including StCCD2, StCCD5, StCCD9, StCCD10, StCCD13, StCCD14 and StCCD16, were no significant changes during different stages of tuber development and among different varieties, they may not be involved in carotenoid degradation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

qRT-PCR expression analysis of StCCD genes in different stages of CY50 and HS7. (A) The content of carotenoids. (B) Expression levels of carotenoids-related genes. Actin was chosen as a negative control. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); * and ** indicate significant differences (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01), One-way ANOVA along with LSD multiple comparison test.

4. Discussion

Potato stands as one of the most important non-cereal food crops worldwide. The carotenoid content in tubers significantly influences both sensory quality and nutritional value. Current research primarily focuses on carotenoid biosynthesis, whereas the degradation process remains less extensively characterized. Genes belonging to the CCD family play pivotal roles in carotenoid catabolism. In this study, a total of 17 CCD genes were identified in the potato genome, which were phylogenetically classified into six subfamilies: CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, CCD8, CCDL, and NCED-a classification consistent with that observed in rice and other mycorrhizal plants (Figure 1 and Table 1). In contrast, Arabidopsis thaliana typically contains only the first four subfamilies (CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, and CCD8). Notably, species within the genus Gossypium (cotton) often possess an additional subfamily, ZAS (zaxinone synthase). These StCCD genes are unevenly distributed across the potato chromosomes. Members of the same subfamily (particularly within the CCD1, CCD4, and CCDL groups) exhibit a pronounced clustering pattern, suggesting potential intragenomic gene duplication events. This genomic arrangement may reflect functional constraints, as genes within the same subfamily often participate in analogous metabolic pathways. Subcellular localization predictions indicated that most StCCD genes are predominantly targeted to chloroplasts or the cytoplasm, with the exceptions of StCCD10, which localizes to peroxisomes, and StCCD15, which is nuclear-localized. This compartmentalization aligns with their putative roles in chlorophyll-related photosynthesis and carotenoid metabolism, consistent with previous reports [29].

Previous studies have indicated that molecular characteristics and the arrangement of exons and introns are important for the evolution of gene families [30]. The molecular properties of StCCD proteins were found to vary; however, members within the same subgroup exhibited similar molecular weights and isoelectric points (Table 1). In general, exon–intron structures were highly conserved among members of the same subfamily, for instance, the NCED subfamily has no introns at all; while most members of the CCD4 subfamily have 2–3 exons, while varied considerably between different subfamilies, such as CCD1, CCD4, and NCED (Figure 2). These results suggests that the core coding region structure of this subfamily is relatively stable during evolution. We also found that the numbers of CCD1 subfamily, CCD1 and CCD15 are completely consistent (14 exons), while CCD14 has only 5 exons. These structural differences likely arise from insertion/deletion events and provide valuable insights into gene evolutionary mechanisms and maybe cause changes in gene function.

Notably, all genes within the NCED subfamily lack introns, a genomic feature that may contribute to their functional efficiency in abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis and ABA-mediated abiotic stress responses [31]. Furthermore, analysis of amino acid sequences revealed highly conserved motif compositions among the CCD1, CCD4, and NCED subfamilies, suggesting that their evolutionary pathways in potato are largely conserved. These findings align with the well-documented roles of CCD1/4 and NCED proteins in secondary metabolism and abiotic stress adaptation, respectively, highlighting their functional specialization in response to environmental cues.

Cis-regulatory elements, which are often located within promoter regions, play essential roles in transcriptional regulation. Analysis of StCCD genes promoters identified numerous putative cis-elements associated with light responsiveness, hormone signaling, and stress responses. These included MeJA-responsive elements (CGTCA-motif and TGACG-motif), an SA-responsive element (TCA-element), GA-responsive elements (GARE-motif, TATC-box, and P-box), and an auxin-responsive element (ABRE TGA-element) (Figure 3). These results suggest that the expression of StCCD genes is modulated by diverse hormonal and environmental signals through specific cis-regulatory elements during potato growth and development. To further investigate the functional implications of the StCCD family, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was conducted (Supplementary Figure S2). The results indicated that StCCD genes are primarily localized in cytoplasmic and organellar compartments and are involved in carotenoid and terpenoid metabolic processes, which are critical for maintaining redox homeostasis in plants.

Gene expression patterns provide critical insights into gene functions. Previous studies have established that CCD genes exhibit spatiotemporal specificity and stress responsiveness across plant species [17,29,31,32]. Among them, CCD1 is known for cleaving carotenoids to generate apocarotenoid volatiles that influence flavor and aroma [33,34,35], and its expression is often stress-inducible [17,36]. The CCD4 subfamily modulates carotenoid content in a tissue-specific manner and plays species-specific roles in stress adaptation, as demonstrated in cucumber and sweet potato [19,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Meanwhile, CCD7 and CCD8 participate in strigolactone biosynthesis, regulating plant architecture and stress responses [33,44,45,46,47], and often function cooperatively [48]. In contrast, CCDL remains poorly characterized [49], whereas the NCED subfamily is essential for ABA biosynthesis and abiotic stress responses [50,51,52,53,54], with its expression subject to multi-level regulation [55,56,57]. In this study, most StCCD genes displayed tissue-specific expression under various treatments (Figure 7A), supporting their involvement in key developmental and stress-response processes. Notably, StCCD1 and StCCD4 homologs were widely expressed across tissues, suggesting broad functional roles, whereas others exhibited localization to specific organs such as roots (StCCD8, StCCD11), fruits (StCCD14, StNCED1, StNCED3), and leaves (StCCD15), consistent with reports in other species [17,29]. Under abiotic stress and hormone treatments, StCCD genes showed divergent induction patterns: StCCD4 responded to multiple stimuli, underscoring its central role in stress adaptation; StCCD12 was activated by mannitol, wounding, and salt; and CCD1-type genes and StCCD11 were upregulated under heat and salt stress. Furthermore, StNCED1 expression was modulated by environmental and hormonal cues, particularly ABA, indicating an ABA-dependent regulatory pathway. In addition, CCD genes harbor numerous cis-acting elements associated with light sensitivity, hormonal responses, growth and development, and stress responses (Figure 3A). This observation is further supported by expression analysis (Figure 7A). For instance, the promoters of StCCD genes are enriched with ABA-responsive elements (ABREs), which aligns with their roles in salt and ABA tolerance. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to fully elucidate the intricate relationships among CCD genes, hormonal signaling, and plant growth and development in potato.

The color of fruits and vegetables is largely determined by carotenoid content, which in turn is regulated by the expression of carotenoid metabolic genes [3]. While the expression of genes such as GGPPS and PSY promotes carotenoid accumulation, members of the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) family typically degrade these pigments [9,10]. Our findings align with this paradigm: yellow-fleshed potato tubers accumulated significantly higher levels of carotenoids than white-fleshed ones (Figure 8A). Notably, the expression trend of GGPPS was opposite to that of CCD1 and CCD4 (Figure 8B), and molecular docking confirmed that CCD proteins can directly bind carotenoid substrates (Figure 6), collectively supporting a role for CCDs in carotenoid degradation. In summary, this study provides a foundation for understanding the functional roles of CCD genes in potato. Further experimental validation is necessary to elucidate their precise mechanisms in plant development and stress responses.

5. Conclusions

In this comprehensive study, we identified 17 CCD genes in potato via a genome-wide analysis. We systematically characterized their gene structures, conserved motifs, phylogenetic relationships, chromosomal locations, gene duplication events, promoter cis-elements, and expression profiles. These genes were unevenly distributed across five chromosomes and classified into six subfamilies based on phylogenetic and structural analyses. The expansion of the CCD gene family in potato is suggested to be driven by tandem and segmental duplication events. The detection of interspecific synteny between several potato CCD genes and their counterparts in related solanaceous plants points to a closer phylogenetic relationship. Molecular docking indicated that not only can all CCD proteins bind to carotenoids, but they also exhibit distinct binding capabilities for different substrates. Expression profiling demonstrated that StCCD genes exhibit tissue and stimulus-specific expression patterns under various abiotic stresses and hormone treatments, suggesting functional diversification. Notably, the expression levels of several StCCD genes in pigmented tubers correlated with carotenoid content, indicating their potential involvement in carotenoid degradation throughout tuber development. Overall, our findings elucidate the specific roles of StCCD genes and enhance the understanding of their functions in carotenoid cleavage and abiotic stress responses in potato. Based on these results, further investigation of key StCCD members is warranted to construct upstream and downstream regulatory models. Such studies will contribute to a deeper comprehension of the regulatory networks governing carotenoid metabolism in potato.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020250/s1, Supplementary Figure S1. Motif logo of StCCD proteins. The size of the letters represents the high or low rating rate; Supplementary Figure S2. Gene ontology (GO) annotation among StCCD protein; Supplementary Figure S3. Molecular docking diagrams for StCCD proteins; Supplementary Table S1. Primers used in this study; Supplementary Table S2. Ka/Ks values of StCCD genes with tandem and segmental duplications; Supplementary Table S3. Ka/Ks ratios of the syntenic relationships between potato and other plants; Supplementary Table S4. The docking scores of StCCD protein–substrate complexes.

Author Contributions

H.S., Q.Z., N.T., K.Z. and Z.W. performed investigations for experiments; H.S., Q.Z., N.T., K.Z., Z.W., X.F. and C.W. performed formal analysis; H.S., Q.Z., N.T., K.Z., Z.W., X.F., C.W., F.W., X.H., C.Y. and H.Z. analyzed the data; X.F., C.W., F.W., X.H. and C.Y. verified results; F.W., X.H. and C.Y. provided varieties and experimental materials; H.Z., S.Z. and Z.R. supervised the experimental progress; P.L. and Z.R. provided funding acquisition; S.Z. and Z.R. administered the project; H.S. and Z.R. drafted the manuscript; H.Z., S.Z. and Z.R. edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Panxi Crops Research and Utilization Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province Open Fund Project Grants (grant numbers SZKF202306); Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (grant number 2024NSFSC1294); National Natural Science Foundation of China (32400466 to Z.T.R.); and Sichuan Potato Innovation Team (grant number sccxtd-2024-09).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study can be found in the manuscript and Supplementary Information, with further inquiries being directed to the corresponding authors P.H.L., S.L.Z. and Z.T.R.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Liang, M.H.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, J.G. Carotenoids biosynthesis and cleavage related genes from bacteria to plants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 2314–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzonelli, C.I. Carotenoids in nature: Insights from plants and beyond. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, N.; Li, L.; Lu, S.; Khin, N.C.; Pogson, B.J. Carotenoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, H.; Uragami, C.; Cogdell, R.J. Carotenoids and photosynthesis. Subcell. Biochem. 2016, 79, 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Yuan, H.; Cao, H.; Yazdani, M.; Tadmor, Y.; Li, L. Carotenoid metabolism in plants: The role of plastids. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggersdorfer, M.; Wyss, A. Carotenoids in human nutrition and health. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 652, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Babili, S.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Strigolactones, a novel carotenoid-derived plant hormone. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chang, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Li, P.; Xin, X.; Zhang, F.; Yu, S.; et al. Recent advancements and biotechnological implications of carotenoid metabolism of Brassica. Plants 2023, 12, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.K.; Li, J.G.; Rui, X.; Ding, F.; Hu, F.C.; Wang, X.H.; Ma, W.Q.; Zhou, K.B. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of carotenoid cleavage oxygenase genes in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.L.; Pogson, B.J. Prospects for carotenoid biofortification targeting retention and catabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, S.; Sami, A.; Haider, M.Z.; Tasawar, L.; Akram, J.; Ahmad, A.; Shafiq, M.; Zaki, H.E.M.; Ondrasek, G.; Shahid, M.S. Genome-Wide identification and in silico expression analysis of CCO gene family in Citrus clementina (Citrus) in response to abiotic stress. Plants 2025, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biłas, R.; Szafran, K.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K.; Kononowicz, A.K. Cis-regulatory elements used to control gene expression in plants. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 2016, 127, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Tan, B.C.; Gage, D.A.; Zeevaart, J.A.; McCarty, D.R. Specific oxidative cleavage of carotenoids by VP14 of maize. Science 1997, 276, 1872–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmiya, A. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases and their apocarotenoid products in plants. Plant Biotechnol. 2009, 26, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hwang, I.; Jung, H.J.; Park, J.I.; Kang, J.G.; Nou, I.S. Genome-wide classification and abiotic stress-responsive expression profiling of carotenoid oxygenase genes in Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 35, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, P.D. Retinal pigment epithelium 65 kDa protein (RPE65): An update. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 88, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Y. Genome-wide identification of CCD gene family in six cucurbitaceae species and its expression profiles in melon. Genes 2022, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Peng, L.; Dong, B.; Zhong, S.; Deng, J.; Fang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Genome-wide identification of 9-cis-epoxy-carotenoid dioxygenases (NCEDs) and potential function of OfNCED4 in carotenoid biosynthesis of Osmanthus fragrans. Trees 2024, 38, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, K.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Cao, H.; Tan, M.; Xie, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, J.; et al. Natural variation in CCD4 promoter underpins species-specific evolution of red coloration in citrus peel. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1294–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, H.; Jamil, M.; Wang, J.Y.; Al-Babili, S.; Mahfouz, M. Engineering plant architecture via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated alteration of strigolactone biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Guo, Y.; Kong, J.; Lecourieux, F.; Dai, Z.; Li, S.; Liang, Z. Knockout of VvCCD8 gene in grapevine affects shoot branching. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Feng, G.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Nie, G.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X. A favorable natural variation in CCD7 from orchardgrass confers enhanced tiller number. Plant J. 2025, 121, e17200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Niu, L.; Yao, J.L.; Pan, L.; Lu, Z.; Cui, G.; Li, G.; et al. PpERF3 positively regulates ABA biosynthesis by activating PpNCED2/3 transcription during fruit ripening in peach. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Hyden, B.; Qin, L.; Liu, L.; Bai, Y.; Han, Y.; Wen, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. Double NCED isozymes control ABA biosynthesis for ripening and senescent regulation in peach fruits. Plant Sci. 2021, 304, 110739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, T.; Wen, L.; Zhang, T.; Ren, M. Biofortification of potato nutrition. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 75, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.Z.; Marler, B.; Kissinger, J.C.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Jin, J.; Cao, P.; Yang, Y. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases: Identification, expression, and evolutionary analysis of this gene family in tobacco. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Yang, Y.L.; Xia, H.X.; Li, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases gene family in Forsythia suspensa: Expression profile and cold and drought stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, G.; Gu, T.; Ding, J.; Li, Y. Bioinformatic and expression analyses on carotenoid dioxygenase genes in fruit development and abiotic stress responses in Fragaria vesca. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2017, 292, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, K.; Fu, W.; Jia, Z.; Li, W.; Tran, L.P.; Jia, K.P.; et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression profiles of the CCD gene family in Gossypium species. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. ZmCCD7/ZpCCD7 encodes a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase mediating shoot branching. Planta 2016, 243, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, G. The genes of CYP, ZEP, and CCD1/4 play an important role in controlling carotenoid and aroma volatile apocarotenoid accumulation of apricot fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 607715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Cheng, J.; Yang, Z.; Cao, R.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, B. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 catalyzes lutein degradation to influence carotenoid accumulation and color development in foxtail millet grains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9283–9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Moraga, A.; Rambla, J.L.; Fernández-de-Carmen, A.; Trapero-Mozos, A.; Ahrazem, O.; Orzáez, D.; Granell, A.; Gómez-Gómez, L. New target carotenoids for CCD4 enzymes are revealed with the characterization of a novel stress-induced carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase gene from Crocus sativus. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 86, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.A.; Jain, D.; Abbas, N.; Ashraf, N. Overexpression of Crocus carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase, CsCCD4b, in Arabidopsis imparts tolerance to dehydration, salt and oxidative stresses by modulating ROS machinery. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 189, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.C.; Molnár, P.; Schwab, W. Cloning and functional characterization of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3011–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Kang, L.; Park, W.S.; Ahn, M.J.; Kwak, S.S.; Kim, H.S. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 (CCD4) cleaves β-carotene and interacts with IbOr in sweetpotato. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 14, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Shen, M.; Lin, F.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Miao, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, R. Optimizing carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 (CCD4) for enhanced β-ionone production in Nicotiana tabacum. Crop J. 2025, 2214–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Chung, M.Y.; Lee, H.A.; Lee, S.B.; Grandillo, S.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Lee, J.M. Natural overexpression of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 in tomato alters carotenoid flux. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; He, L.; Dong, J.; Zhao, C.; Tang, R.; Jia, X. Overexpression of sweet potato carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 (IbCCD4) decreased salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; He, L.; Dong, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Tang, R.; Wang, W.; Ji, Z.; Cao, Q.; Xie, H.; et al. Integrated metabolic and transcriptional analysis reveals the role of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 (IbCCD4) in carotenoid accumulation in sweetpotato tuberous roots. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrazem, O.; Rubio-Moraga, A.; Berman, J.; Capell, T.; Christou, P.; Zhu, C.; Gómez-Gómez, L. The carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase CCD2 catalysing the synthesis of crocetin in spring crocuses and saffron is a plastidial enzyme. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umehara, M.; Hanada, A.; Yoshida, S.; Akiyama, K.; Arite, T.; Takeda-Kamiya, N.; Magome, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Yoneyama, K.; et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature 2008, 455, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, L.; Yu, H.; Zeng, L.; Hu, J.; Ni, S.; Rao, Y.; Li, S.; Chu, J.; Meng, X.; et al. A strigolactone biosynthesis gene contributed to the green revolution in rice. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasare, S.A.; Ducreux, L.J.M.; Morris, W.L.; Campbell, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Roumeliotis, E.; Kohlen, W.; van der Krol, S.; Bramley, P.M.; Roberts, A.G.; et al. The role of the potato (Solanum tuberosum) CCD8 gene in stolon and tuber development. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Gu, X.; Chen, S.; Qi, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, X. Far-red light inhibits lateral bud growth mainly through enhancing apical dominance independently of strigolactone synthesis in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wan, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, R.; Ruan, M.; Ye, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhou, G.; Yao, Z.; Yang, Y. A comprehensive analysis of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases genes in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016, 34, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Qanmber, G.; Li, F.; Wang, Z. Updated role of ABA in seed maturation, dormancy, and germination. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 35, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.K.; Da-Silva, C.J.; Garcia, N.; Agualongo, D.A.P.; de Oliveira, A.C.B.; Kanamori, N.; Takasaki, H.; Urano, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Nakashima, K.; et al. The overexpression of NCED results in waterlogging sensitivity in soybean. Plant Stress 2022, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavassi, M.A.; Silva, G.S.; da Silva, C.d.M.S.; Thompson, A.J.; Macleod, K.; Oliveira, P.M.R.; Cavalheiro, M.F.; Domingues, D.S.; Habermann, G. NCED expression is related to increased ABA biosynthesis and stomatal closure under aluminum stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 185, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Xie, N.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, F.; Gao, Q.; Tian, L.; et al. OsNCED5, a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene, regulates salt and water stress tolerance and leaf senescence in rice. Plant Sci. 2019, 287, 110188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.F.; Contaldi, F.; Celso, F.L.; Karalija, E.; Paz-Carrasco, L.C.; Barone, G.; Ferrante, A.; Martinelli, F. Expression profile of the NCED/CCD genes in chickpea and lentil during abiotic stress reveals a positive correlation with increased plant tolerance. Plant Sci. 2023, 336, 111817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.P.; Mi, J.; Ali, S.; Ohyanagi, H.; Moreno, J.C.; Ablazov, A.; Balakrishna, A.; Berqdar, L.; Fiore, A.; Diretto, G.; et al. An alternative, zeaxanthin epoxidase-independent abscisic acid biosynthetic pathway in plants. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Du, K.; Shi, Y.; Yin, L.; Shen, W.H.; Yu, Y.; Liu, B.; Dong, A. H3K36 methyltransferase SDG708 enhances drought tolerance by promoting abscisic acid biosynthesis in rice. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1967–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.U.; Mun, B.G.; Bae, E.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.H.; Shahid, M.; Choi, Y.I.; Hussain, A.; Yun, B.W. Drought stress-mediated transcriptome profile reveals NCED as a key player modulating drought tolerance in Populus davidiana. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 755539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.