Abstract

Advances in plant nutrition have driven substantial progress in modern fertilization technologies. Nevertheless, excessive chemical fertilizer application, low nutrient-use efficiency, and the resulting environmental pollution remain widespread. We have reviewed the research progress and existing limitations in the field of plant nutrition and fertilization technology. Based on the traditional plant nutrition diagnosis and integrating visual diagnosis methods, this study explores the intrinsic relationship between plant growth status, nutrient supply conditions, and crop yield and proposed the concept of “status nutrition”. Variations in environmental nutrient conditions lead plants to exhibit distinct growth status in terms of vigor and phenotype. We define the plant nutritional status reflected by this growth status as “status nutrition”. Based on growth characteristics, plant growth status can be classified as weak, normal, or vigorous, corresponding to deficient, appropriate, and excessive environmental nutrient supply, respectively. Guided by this concept, an innovative rice “extremely dense planting” technology is integrated by increasing planting density, eliminating tiller-stage fertilization, and optimizing nitrogen management. The technology adapts to growth status with low nutrient demand, coordinates population growth and main-stem panicle formation, and achieves high yield with reduced fertilizer inputs. Further research is needed on the nutrient metabolism mechanisms of plants under different growth statuses and the growth status grading system. The promotion of “extremely dense planting” is constrained by crop variety traits and soil fertility, and its parameters urgently need to be optimized. Overall, the framework of “status nutrition” provides important theoretical support for the development and application of crop high-yield cultivation technologies.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of accelerated global climate change, intensified international fluctuations, and tightening global food supply and demand balance, the development of large-scale, intensive, efficient, and sustainable modern agriculture has become a core strategic focus. However, the sustained high input, low efficiency, and high pollution patterns of fertilizer use still seriously hinder the green transformation of agriculture. In technical solutions to address these issues, “reducing nitrogen content and improving efficiency” is a key method. This strategy aims to improve nutrient utilization efficiency and reduce resource waste, pollutant emissions, and production costs while enabling agriculture to achieve high yield, high efficiency, and green low-carbon development, providing key technological support for long-term sustainable development.

Building on advances in plant nutrition and modern fertilization science, chemical fertilizer reduction can be pursued through multiple dimensions, including precision fertilization, partial substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic amendments, optimization of fertilization methods, adjustment of planting density, and so on [1]. Studies have shown that the combined application of these measures can significantly improve nitrogen-use efficiency (NUE) and markedly enhance the effectiveness of fertilizer reduction and efficiency improvement [1,2]. In recent years, nitrogen-reduction and dense-planting cultivation models have been adopted in major cereal crops such as rice, wheat, and maize, demonstrating clear advantages in simultaneously increasing crop yield and NUE, and offering an effective technical pathway to achieve “nitrogen reduction with efficiency enhancement” [3,4]. To explore the potential of such models in rice, we previously developed rice “extremely dense planting” cultivation technology through field experiments integrating nitrogen reduction, tiller control, and dense planting. The rice “extremely dense planting” technology [5] increases basic seedling density to secure the number of effective panicles required for high yield while regulating tiller dynamics through optimized nitrogen management and omitting traditional tillering fertilizer. This strategy coordinates population growth with main-stem panicle formation, enabling high rice yields while substantially reducing both the rate and frequency of nitrogen application, improving NUE.

In this context, the present paper integrates the development of plant nutrition and modern fertilization techniques and systematically analyzes the environmental nutrient supply characteristics corresponding to different plant growth statuses at the same developmental stage. We propose the concept of “status nutrition”, establish classification criteria for plant growth status and environmental nutrient conditions, and describe the matching relationships between plant growth status and nutrient requirements, thereby providing a theoretical basis for precise nutrient regulation. Field practice has demonstrated that, by deliberately selecting plant growth status with relatively low nutrient demands and increasing planting density, it is possible to achieve high crop yields while reducing chemical fertilizer inputs. This theoretical framework offers key support for the design and application of the rice “extremely dense planting” technology [5]. Moreover, “status nutrition” and “extremely dense planting” have practical significance for innovating crop cultivation technologies, further mitigating excessive chemical fertilizer use, and promoting the green development of agriculture.

2. Advances in Plant Nutrition and Efficient Fertilization Technology

In recent years, plant nutrition research has achieved substantive progress in several core directions, including nutritional genetic analysis, nutrient cycling, the development of novel fertilizers, and the optimization of high-efficiency fertilization technologies. These advances are increasingly being translated into major drivers of sustainable agricultural development [6,7]. Nevertheless, agricultural production still faces persistent challenges, such as excessive chemical fertilizer inputs, nutrient losses, soil fertility decline, and low fertilizer use efficiency. Under conditions of long-term intensive land use, reconciling the multiple objectives of stable high yield, efficient nutrient utilization, and the sustained health of agroecosystems has become a major technical challenge for plant nutrition in the new era [6].

2.1. Research Priorities in Plant Nutrition at the New Stage

In recent years, plant nutritional molecular biology has made notable progress in elucidating the mechanisms of nutrient uptake and transport. Numerous functional genes and regulatory components involved in nutrient acquisition have been mapped and functionally characterized, including members of the OsNRT, OsPT, and ZmAMT families; specific transporter proteins; and associated signal transduction modules such as OsNRT2s-OsNAR2, CBL-CIPK-AKT1, SPX4-PHRs-NLP, and PHR-SPX-PT. These advances provide a strong molecular foundation for improving nutrient uptake capacity and enhancing both yield and NUE [8,9,10,11]. In parallel, the internal regulatory mechanisms governing crop growth, yield formation, and quality traits have been extensively investigated [12,13,14,15]. With modern molecular breeding tools, an increasing number of excellent alleles with stress tolerance and high nutrient-use efficiency have been identified, providing elite germplasm resources for improving yield and efficiency [16,17,18].

Soil nutrient cycling is fundamental to sustaining soil fertility and ecosystem functioning and is closely linked to agricultural productivity. Optimized fertilization can enhance soil carbon sequestration and reduce greenhouse gas emissions [19,20,21,22]. Soil microorganisms are the core drivers of nutrient cycling. With advances in high-throughput sequencing, global maps of soil fungal and bacterial diversity have been established [23,24]. Studies have confirmed that ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, nitrite-oxidizing bacteria, and archaea can promote nitrogen transformation [25,26]; phosphorus-solubilizing microorganisms can increase the bioavailability of soil phosphorus [27,28]; and microbial interactions can improve resource use efficiency and reduce nutrient loss [29,30]. Soil degradation reduces the stability of fungal networks [31], while progress in strain isolation and community assembly regulation provides technical support for exploring microbiome functional potential [32]. In recent years, the community structure and spatial distribution patterns of microbiomes have been clarified in crops such as maize and rice [33,34], and their functional roles in maintaining crop health have been elucidated through the integration of environmental, soil, and crop characteristics [3,4,35]. For example, biological nitrification inhibitors secreted by rice roots can improve nitrogen absorption efficiency [36]; phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria can activate insoluble phosphorus [37]; and rhizosphere microbe–root interactions can enhance crop resistance to soil-borne diseases [38]. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria activity and how legumes adapt to rhizobia are also prominent research directions [36,39,40]. Although there has been progress in exploring soil nutrient cycling and microbial community functions, the specific mechanisms of cycling and the core mechanisms of soil fertility maintenance under high-intensity utilization of arable land have not been clarified, and there is a lack of efficient fertilization and efficiency regulation technologies, which makes it difficult to support sustainable agricultural development.

Substantial progress has also been made in the development of novel fertilizers, including bio-organic fertilizers and slow- and controlled-release fertilizers, among others. Organic fertilizer products not only show strong efficacy in the integrated management of soil-borne diseases but also alleviate soil acidification, regulate soil microbial community structure, and enhance soil fertility while meeting crop nutrient demands [41,42]. Fertilizers centered on functional microorganisms can significantly improve crop nutrient uptake and utilization efficiency through microbial metabolic activities and their interactions with plants and soil [23]. In the field of slow- and controlled-release fertilizers, high-efficiency and intelligent coating materials represent a core direction for breakthroughs, enabling responsive nutrient release to soil signals such as pH and temperature and better synchronizing supply with crop nutrient uptake [43]. Fertilizers containing humic acid and other bioactive components can contribute to yield improvement [44], and biochar application in farmland shows considerable potential for carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emission reduction [45]. Water-soluble fertilizers based on amino acids, humic acids, and other organic resources have also developed rapidly [23,46,47]. While novel fertilizers exhibit prominent advantages in improving soil fertility, optimizing crop nutrient supply, and other aspects, they have not been widely promoted and applied due to factors such as relatively high costs and inadequate supporting technologies.

2.2. Research on High-Efficiency Fertilization Techniques

Centering on the core goal of synergistically achieving high crop yield, good quality, efficient nutrient use, and ecological environment protection, there have been continuous innovations in theories and technologies in the field of efficient fertilization. Various high-efficiency fertilization technologies have developed rapidly, including soil testing and formulated fertilization, nutrient diagnosis-based fertilization technology, and intelligent fertilization systems, as well as the regulation of planting density and nitrogen fertilizer management.

Soil testing and formulated fertilization play a pivotal role in improving on-farm fertilization practices, accurately matching crop nutrient requirements, and promoting sustainable agricultural development. However, challenges persist in management models and technical implementation, including the standardization of soil testing and analysis procedures, the adaptability of recommended fertilization index systems across regions and crop types, and the efficiency of translating technical recommendations into user-friendly products and services.

Plant nutrition diagnosis is a core technical system that accurately determines the nutritional deficiency, suitability, or excess status of plants to guide scientific fertilization. As a core component of precision agriculture, fertilization technology based on nutritional diagnosis has made some progress in recent years. Sun et al. [48] constructed a nitrogen stress diagnostic index system by scanning rice leaves and using MATLAB 2013b (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) software to extract multipart characteristic parameters of the leaves, providing new ideas for precise nutrient regulation. Yang et al. [49] proposed a linear regression estimation model framework that combines unmanned aerial vehicle multispectral data with the RiceGrew model to invert phenological periods, significantly improving the accuracy of estimating dry matter/nitrogen accumulation and nutrient index. Due to the innovation of computer technology, nutritional diagnosis technology has made breakthrough progress in systematization and programmability, providing important technical support for plant nutritional diagnosis [50,51,52]. However, traditional plant nutrition diagnosis classification systems have limitations and mainly focus on guidance for topdressing [53,54], making it difficult to meet the urgent need for precise, reduced, and efficient fertilization throughout the entire growth period of crops. Therefore, plant nutrition diagnosis needs to be combined with yield targets, plant growth characteristics, and nutrient demand patterns to construct a more refined classification system, providing more accurate technical support for achieving the goal of reducing fertilizer application and increasing efficiency.

In the context of the synergistic regulation of nitrogen nutrition and planting density, the “reducing nitrogen and increasing density” fertilization strategy has shown distinct advantages in concurrently improving crop yield and nitrogen-use efficiency [3,4]. Taking rice as an example, under traditional sparse planting patterns, farmers often rely on increased basal and tiller-promoting nitrogen applications to elevate tiller number and thereby raise yield. However, studies have shown that the peak of nitrogen uptake in rice occurs from the jointing stage to full heading, whereas excessive nitrogen input at early stages often leads to severe nitrogen loss. The underlying issue is a mismatch between the temporal pattern of soil nitrogen supply and the dynamics of crop nitrogen demand, which constrains the simultaneous improvement in yield and NUE. Existing research has confirmed that “reducing nitrogen and increasing density” can effectively achieve the synergistic enhancement of yield and NUE in multiple crops, thereby fulfilling the goal of “nitrogen reduction with efficiency enhancement” [3,4,5]. Despite these promising outcomes, systematic and in-depth studies remain insufficient on the mechanisms governing the balance and coordination between nitrogen application rate and planting density and on how to fully exploit the potential for nitrogen reduction and efficiency improvement in rice within this framework.

Despite the rapid development of plant nutrition and efficient fertilization technologies in recent years, environmental pollution caused by excessive fertilization has become increasingly prominent [55,56,57], and the average nitrogen application rate in the high-yield cultivation systems of major food crops remains at a relatively high level [57,58,59]. Taking rice cultivation as an example, the reasons are as follows: first, existing technical research still focuses on yield improvement, and the fertilizer reduction effect has not been fully highlighted; second, even under the nitrogen reduction regulation mode, the application of tillering fertilizer is still widely valued, and the dependence of crop yield formation on tillering has not been fundamentally changed [5]. Therefore, modern fertilization technology shifts from the traditional paradigm of “emphasizing input while neglecting regulation” to a new paradigm prioritizing synergy and precise regulation; its core scientific basis lies in clarifying the coordination between plant growth status and nutrient conditions in the growth environment, thereby maintaining a rational and efficient population growth status. Against this background, based on traditional plant nutrition diagnosis, this study proposes the concept of “status nutrition” by thoroughly analyzing the intrinsic relationships among environmental nutrient conditions, crop growth status, and yield formation. The concept divides classification criteria for plant growth status and environmental nutrient conditions and clarifies the matching relationships between growth status and nutrient demand. Based on this theoretical framework, an innovative integrated rice “extremely dense planting” technology has been developed. This technology innovatively regulates planting density, fertilizer application rate, and fertilizer application timing. Practical applications have shown that this technology can significantly increase rice yield and NUE. Subsequently, it is intended to integrate supporting measures such as the optimization of variety characteristics and the application of new-type fertilizers to promote its widespread application, thereby providing a practical model for scientific and rational fertilization.

3. Plant Status Nutrition

Plant growth is inherently stage-specific [60,61]. Owing to differences in environmental nutrient conditions—particularly the intensity and buffering capacity of nutrient supply—plants can display distinct growth status (vigor and phenotype) even at the same developmental stage. We define the internal nutritional status manifested by these growth differences as “status nutrition”. Plant productive performance varies across different status–nutrition. Based on observable growth characteristics, plant growth status can be classified into three primary categories—weak, normal, and vigorous—corresponding to environmental nutrient supply levels characterized as deficient, appropriate, and excessive, respectively.

The status–nutrition framework provides a more refined phenotypic basis and classification system for conventional plant nutrient diagnosis, while plant nutrient diagnosis offers essential technical support for the validation, quantification, and practical application of status nutrition.

3.1. Plant Growth Status

In practical crop management, differences in growth increment are typically expressed through growth vigor and phenotype [60,61,62], and these features correspond closely to the level of environmental nutrient supply. Based on long-term observations and research on plant growth characteristics, taking widely cultivated conventional japonica rice cultivars such as “Nanjingjing 46” and “Ningxiangjing 9” as the research objects, plant growth status can be grouped into three primary categories: weak, normal, and vigorous. Each primary category can be further subdivided into three secondary grades according to differences in growth intensity. Accordingly, plants can exhibit nine distinct growth statuses within a given period, sequentially numbered from Grade 1 to Grade 9 in ascending order of growth vigor. The correspondence between these growth-status grades and the specific evaluation indicators is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Graded evaluation indicators for plant growth status.

3.1.1. Weak Growth Status

Plants in a weak growth status generally exhibit insufficient vegetative and reproductive growth. Typical characteristics include dwarf or stunted plants, slender stems, few or no branches/tillers, small and thin leaves, low chlorophyll content, pale or yellowish-green leaf color, small fruits or ears with few seeds, and low yield per plant. Depending on the severity of the growth limitation, weak growth status can be subdivided into three grades:

Grade 1: Extremely weak growth status.

Plants are severely dwarfed, with very slender stems and almost no branches or tillers. Leaves are extremely small and thin; chlorophyll content is extremely low; and leaf color is yellowish-green. Fruits or ears are extremely small, with very few seeds. Yield per plant is approximately 40% of the normal yield level of the variety.

Grade 2: Strongly weak growth status.

Plants are dwarfed, with slender stems and few or no branches/tillers. Leaves are small and thin, with low chlorophyll content and yellowish-green coloration. Fruits or ears are relatively small and bear few seeds. Yield per plant is approximately 60% of the normal yield of the variety.

Grade 3: Weak growth status.

Plants are moderately dwarfed, with slender stems and few or no branches/tillers. Leaves are small and thin; chlorophyll content is relatively low; and leaf color is pale green. Fruits or ears are small and carry relatively few seeds. Yield per plant is approximately 80% of the normal yield of the variety.

3.1.2. Normal Growth Status

Plants in a normal growth status generally exhibit healthy individual growth. Typical features include normal plant height, moderately thick stems, few or no branches/tillers, upright leaves, a compact architecture, appropriately sized and thick leaves, normal chlorophyll content, bright green leaf color, normal fruit or ear development, normal seed number, and normal yield per plant. Based on subtle differences in growth performance, normal growth status can be subdivided into three grades:

Grade 4: Weak normal growth status.

Plants have normal height and moderately thick stems, with few or no branches/tillers. Leaves are upright and the plant type is compact. Leaf size and thickness are appropriate, but chlorophyll content is slightly low and leaf color appears pale green. Fruits/ears and seed number are largely normal. Yield per plant reaches approximately 80–85% of the normal yield of the variety.

Grade 5: Slightly weak normal growth status.

Plants maintain normal height and moderately thick stems, with few or no branches/tillers. Leaves are upright and moderately sized, with normal thickness. Chlorophyll content is within the normal range and leaves appear light emerald green. Fruits/ears and seed number are normal. Yield per plant reaches approximately 85–95% of the normal yield of the variety.

Grade 6: Normal growth status.

Plants show normal height and moderately thick stems, few or no branches/tillers, upright leaves, and a compact plant type. Leaf size and thickness are appropriate; chlorophyll content is normal; and leaves are emerald green. Fruits/ears and seed number are normal. Yield per plant reaches approximately 95–100% of the normal yield of the variety.

3.1.3. Vigorous Growth Status

Plants in a vigorous growth status generally display robust vegetative growth. They are characterized by tall plant height, thick and sturdy stems, numerous branches or tillers, large and thick leaves that may spread outward, high chlorophyll content, dark green leaf color, abundant fruits or ears with normal seed number, and high yield per plant. According to the degree of vigor, this status can be subdivided into three grades:

Grade 7: Weak vigorous growth status.

Plants are tall with relatively thick stems and a moderately increased number of branches/tillers. Leaves are large and thick, mostly upright, and chlorophyll content is high; leaf color is emerald green. Fruits/ears are abundant with normal seed number, and yield per plant is relatively high, increasing with higher nutrient supply.

Grade 8: Vigorous (robust) growth status.

Plants are tall with thick, sturdy stems and numerous branches/tillers. Leaves are large and thick, upright but forming a large angle with the stem. Chlorophyll content is high and leaf color is dark green. Fruits/ears are abundant with a normal number of seeds, and yield per plant is high and relatively stable.

Grade 9: Ultra-vigorous (excessively vigorous) growth status.

Plants are very tall with thick, fleshy stems and a large number of branches/tillers. Leaves are extremely large and thick, spreading nearly perpendicular to the stem or even drooping. Chlorophyll content is high and leaf color is deep green. Vegetative growth is excessive and reproductive development is delayed. Although fruits/ears are abundant and seed number per ear is generally normal, intensified competition for assimilates among branches reduces the seed-setting rate. Biomass per plant is the highest among all grades, whereas grain yield per plant gradually declines with further increases in nutrient supply.

3.2. Plant Growth Status and Environmental Nutrient Conditions

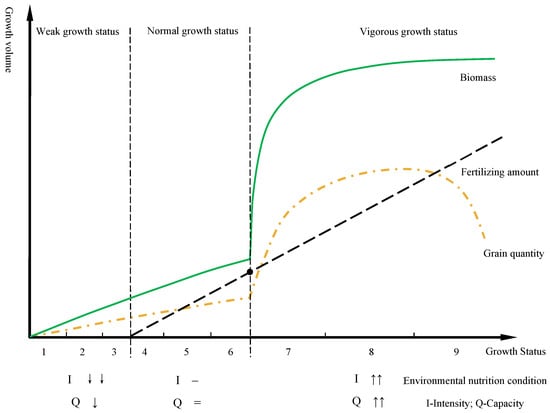

Differences in plant growth status essentially represent external manifestations of internal metabolic intensity. This intrinsic link underpins the tight coupling between plant growth status and nutritional condition [63,64,65,66,67]. Plant nutritional status, in turn, is directly constrained by environmental nutrient conditions, specifically the intensity and buffering capacity of available nutrient supply in the growth medium. In general, each growth-status grade corresponds to a characteristic range of environmental nutrient conditions. The relationship between plant growth status and environmental nutrient levels can be illustrated schematically (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between plant growth status and environmental nutrient conditions. Note: I (intensity) refers to the immediate supply capacity of soil available nutrients; Q (capacity) refers to the potential nutrient reserve capacity of soil. The corresponding parameter changes and quantitative thresholds for each growth stage are as follows: in the weak growth stage, intensity decreases sharply (I↓↓) and capacity decreases (Q↓); in the normal growth stage, intensity remains stable (I−) and capacity stays constant (Q=); and in the vigorous growth stage, both intensity (I↑↑) and capacity (Q↑↑) increase sharply.

For the weak growth status (Grades 1–3), severely restricted growth indicates inadequate internal nutrient content and poor nutritional status. This corresponds to environmental conditions in which both the supply intensity and buffering capacity of available nutrients are extremely low: soil nutrients are markedly deficient, nutrient supply is far below plant demand, and plants cannot acquire sufficient mineral nutrients to sustain normal growth and development. This combination reflects a weak growth status under deficient environmental nutrient conditions.

For the normal growth status (Grades 4–6), overall growth performance (aside from limited or absent branching/tillering) is normal, indicating adequate internal nutrient content and favorable nutritional status. This corresponds to environmental nutrient conditions where both nutrient supply intensity and buffering capacity can meet the demands of a single plant without branches/tillers. Under these conditions, nutrient supply and demand are essentially balanced, resulting in normal plant growth. This normal growth status reflects appropriate environmental nutrient conditions.

For the vigorous growth status (Grades 7–9), growth clearly exceeds the normal range, indicating substantial nutrient accumulation in plant tissues. This corresponds to environmental nutrient conditions where both supply intensity and buffering capacity far exceed the requirements of a single, non-branching plant. In this context, plants grow vigorously, produce numerous branches/tillers, and accumulate biomass rapidly. Such growth reflects excessive environmental nutrient conditions.

4. Status Nutrition and High-Yield Crop Models

By analyzing the relationship between plant “status nutrition” and yield formation, differentiated high-yield pathways and fertilization strategies can be developed for plants with a distinct growth status. On this basis, corresponding cultivation and nutrient-management technology systems can be established, with potentially far-reaching implications for agricultural production and broader socio-economic development. The concept of plant “status nutrition” therefore provides a new lens for interpreting crop production processes and supports a broad classification of high-yield models into two types: the traditional high-yield model and an innovative high-yield model, namely the “extremely dense planting” model.

4.1. Traditional Crop High-Yield Model

The traditional high-yield mode mainly promotes and regulates branching (tillering) through the application of chemical fertilizers to increase yield and remains the dominant paradigm in current crop production.

4.1.1. Selection of Plant Growth Status in Traditional High-Yield Models

In traditional models, Grades 1–6 plants are typically characterized by limited or absent branching (or very few branches) and relatively weak overall growth. Although plants in Grade 7 begin to branch, branching intensity remains low and growth is still comparatively weak. Accordingly, seedlings in Grades 1–7 are collectively referred to as “weak seedlings”.

In contrast, Grade 9 represents an excessively vigorous growth status. Plants in this grade exhibit overly luxuriant vegetative growth, intensified competition for light and nutrients within and among plants, elevated susceptibility to pests and diseases, and a high risk of lodging. Although total biomass is high, grain yield is often low or may even decline, accompanied by a reduced harvest index. Consequently, Grade 9 seedlings are classified as “over-vigorous seedlings” and are generally undesirable in production.

Therefore, the traditional high-yield model typically identifies Grade 8 as the optimal growth status. Seedlings in this grade are considered “robust seedlings”, with an advantageous combination of vigor and architecture for high yield, and are widely recognized as the preferred target status for achieving high crop productivity.

4.1.2. Fertilization Techniques in Traditional High-Yield Models

In the traditional high-yield model, Grade 8 is adopted as the target growth status, and yield formation depends strongly on developing a large number of effective branches/tillers. However, achieving and maintaining this ideal status in production is challenging. Beyond favorable environmental conditions, it requires a sustained and sufficiently high intensity of nutrient supply, particularly nitrogen. If nutrient supply intensity is inadequate or cannot be maintained, crops cannot accumulate sufficient nutrients, the target growth status cannot be sustained, and yield is ultimately compromised. To achieve and maintain the Grade 8 “ideal status”, “promotion and regulation” fertilization technologies function as essential control measures, and their integration constitutes the central technical pillar of the traditional high-yield model [68,69,70,71]. These measures can be summarized as “early promotion, mid-term regulation, and late stabilization”.

Early promotion refers to rapidly elevating plant nutrient status during early growth by applying adequate basal fertilizer and early topdressing designed to stimulate branching/tillering. This approach accelerates branch/tiller initiation and growth, supports the formation of robust seedlings, and establishes a strong foundation for subsequent development and yield formation. Production experience indicates that the earlier branches/tillers are induced under “early promotion”, the greater their probability of becoming productive and contributing to yield. However, early promotion depends heavily on readily available chemical fertilizers, because only quick-acting fertilizers can rapidly increase soil nutrient supply intensity within a short period to meet crop uptake requirements and deliver the intended “promotion” effect. Because organic fertilizers generally provide lower nutrient supply intensity and are difficult to synchronize with early rapid growth demands—even at higher application rates—they are often underutilized in the traditional model.

Mid-term regulation involves controlling fertilizer inputs, irrigation, and other agronomic factors during the middle growth stage to prevent excessive vegetative growth and to maintain crops stably in Grade 8. Regulation is typically achieved through integrated agronomic measures; when these are insufficient, chemical growth regulators may be used. In many cropping systems, chemical regulation has become a routine component of high-yield cultivation.

Late stabilization refers to timely and appropriate fertilizer application during later growth stages, particularly in fields where early fertilization was limited. The objective is to prevent premature senescence, improve seed-setting rate, and increase grain weight. In addition, small supplemental applications may be made based on real-time crop growth status to avoid excessive luxuriance and delayed maturity.

In current practice, heavy basal and tiller fertilization remains the mainstream pattern. In rice, this approach aligns well with traditional high-yield strategies and is favored for its operational simplicity. Although many studies advocate for split nitrogen application and delayed topdressing, farmers often continue to prefer heavy basal and tiller fertilization because of concerns that late-stage fertilization may not sufficiently compensate for early nutrient deficits. However, this traditional model applies large amounts of nitrogen during stages when rice has a relatively low N demand and limited uptake capacity, resulting in substantial nitrogen losses and low fertilizer use efficiency. Lin et al. [72] further showed that the utilization efficiency of basal and tiller fertilizers in rice is the lowest among all nitrogen applications, thereby constraining overall nitrogen-use efficiency.

4.2. “Extremely Dense Planting” Model

The “extremely dense planting” model is a crop production strategy that secures the required number of effective panicles for high yield by markedly increasing the planting density of basic seedlings. Through optimized nitrogen management and omission of traditional tiller fertilizer, this model deliberately restricts tiller production, aiming to minimize or even eliminate tillering in rice. In doing so, it coordinates population growth with main-stem panicle formation while reducing chemical fertilizer inputs to a minimum.

Developed through many years of field experimentation, this technology represents a novel, high-yield, and green production model that is fundamentally distinct from traditional approaches and characterized by the dual advantages of high yield and reduced chemical fertilizer inputs [5]. Although originally proposed in the context of nitrogen reduction and efficiency enhancement in rice, the core principles of “extremely dense planting” are, in theory, transferable to other crops and may provide a valuable reference for designing broader high-efficiency production systems.

4.2.1. Fertilization Techniques in the “Extremely Dense Planting” Model

With the deepening implementation of national policies on fertilizer reduction and efficiency enhancement, crop production urgently requires a green cultivation technology system that simultaneously ensures stable grain yield, reduced fertilizer inputs, and improved nutrient-use efficiency. In recent years, nitrogen reduction combined with dense planting has been shown to synergistically increase yield and nitrogen-use efficiency in staple crops such as rice and wheat [3,4,35]. However, existing studies still exhibit clear limitations. First, most work remains yield-centered, and the reduction in fertilizer inputs is typically modest (generally 20–30%) [5]. Second, even under nitrogen-reduction treatments, many studies continue to follow the traditional nutrient-management logic of “promoting tillering with nitrogen”, placing excessive emphasis on tiller-stage topdressing and thereby failing to fully exploit the potential for efficient nitrogen utilization in crops [5].

Through systematic analysis of the intrinsic relationship between nutrient supply and yield formation, we found that the total nutrient demand of non-tillering plants is substantially lower than that of tillering plants [73,74]. In rice, plant nitrogen content generally must reach or exceed 3.5% during the tillering stage to ensure normal tiller initiation; insufficient nitrogen directly reduces tiller number [75]. Meanwhile, the main stem exhibits superior production performance relative to tillers, and the main-stem root system has stronger nutrient uptake capacity than tiller roots [76]. Based on these findings, we proposed the “extremely dense planting” technology for rice. Its core lies in optimizing fertilizer composition, scientifically managing nitrogen application, omitting tiller fertilizer, and precisely controlling tiller number to coordinate population growth with main-stem panicle formation. Wu et al. [5] have conducted multi-year, multi-location field plot experiments and demonstration programs across major rice-producing regions in Anhui and Jiangsu provinces. The results indicated that, under the optimized fertilization regime of “extremely dense planting”, both rice yield and nitrogen-use efficiency (NUE) were significantly higher than those under the corresponding treatments of conventional-density cultivation.

The central innovation of “extremely dense planting” is that it breaks away from the conventional nutrient-management paradigm of “promoting tillering with nitrogen”. Instead, it emphasizes matching nutrient supply to the actual growth status of plants rather than simply pursuing higher tiller numbers, thereby achieving a closer alignment between plant nutrient demand and environmental nutrient supply. This technology not only provides a practical cultivation carrier for implementing the “status nutrition” concept but also establishes a grain production model with greater yield potential and stronger green attributes than traditional high-yield approaches. It therefore offers a feasible technical pathway for nitrogen reduction and efficiency enhancement in agriculture and for advancing sustainable development.

4.2.2. Selection of Plant Growth Status in “Extremely Dense Planting” Models

In the “extremely dense planting” model, Grades 4–6 (normal growth status) are selected as the target growth status. Under this model, branching/tillering is not required; normal main-stem growth is sufficient to support high yield when combined with increased planting density. As a result, there is no need to promote tillering at early stages or suppress excessive tillering in the mid stages, substantially simplifying the fertilization strategy and field regulation.

Under the “extremely dense planting” model, no dedicated tiller fertilizer is applied, total fertilizer input (on a pure nutrient basis) can be reduced by approximately 20% relative to the optimized fertilizer rate in traditional high-yield models, and nitrogen input can be reduced by more than 50% [5]. Importantly, nitrogen application must be strictly controlled in “extremely dense planting”. Excessive nitrogen input, when coupled with ultra-high planting density, will inevitably increase lodging and disease risks and exacerbate inefficient assimilate allocation, leading to yield penalties.

5. Conclusions

Achieving “nitrogen reduction with efficiency enhancement” in crop production constitutes a core challenge in contemporary agricultural development. Based on the concept of plant “status nutrition”, the “extremely dense planting” technology selects Grades 4–6 (normal growth status) as the target status. Within this framework, nitrogen inputs can be significantly reduced, while yield reductions at the individual plant level are compensated by optimized population density, thereby realizing a synergistic improvement in rice yield and nitrogen-use efficiency. This establishes a novel technical pathway centered on “status nutrition” for achieving crop “nitrogen reduction with efficiency enhancement”. Nevertheless, large-scale dissemination and application of “extremely dense planting” remain constrained by factors such as varietal characteristics, soil fertility conditions, and management practices, and the optimal technical parameters require further refinement.

6. Conditions and Limitations for the Application of the Technique, and Future Perspectives

The current classification of plant growth status is still limited to the framework of traditional plant nutrition diagnosis methods and only provides more refined grading of plant growth status and appearance characteristics. To further enrich, refine, and quantify the growth status classification system, there is an urgent need to systematically investigate key metabolic processes (e.g., nutrient absorption, translocation, and assimilation) in plants under different growth statuses, thereby laying a theoretical foundation for the scientific rigor of the classification criteria.

Different crop varieties respond differently to “status nutrition” because of variations in plant architecture, nutrient-use efficiency, and related traits. Traditional breeding has long targeted the Grade 8 vigorous growth status, imposing requirements for strong tillering capacity and luxuriant growth [77,78]. In contrast, the “extremely dense planting” model deliberately restricts tillering and requires only a nutrient supply sufficient to maintain normal main-stem growth, thereby markedly reducing dependence on high soil fertility. Under this model, ideal rice varieties should possess the following traits: excellent grain quality, moderate plant height, compact architecture, large panicles with high grain number, high grain yield per panicle, strong stress resistance, and stable adaptation to Grades 4–6 growth status. In this sense, “extremely dense planting” not only reconciles high yield with high nutrient-use efficiency but also provides new technical directions and breeding targets for developing high-yield, high-efficiency crop varieties with substantial research and application value. In the future, molecular genetics approaches may be used to identify rice genotypes well-suited to “extremely dense planting”, further enhancing its adaptability and deployment potential.

Traditional high-yield models rely on intensive chemical fertilizer application, leading to considerable nutrient losses and severe non-point source pollution. In contrast, the “extremely dense planting” model employs minimal chemical fertilizer inputs. A natural concern arises as to whether this approach will accelerate soil fertility depletion and induce long-term yield reductions. The most straightforward strategy to address this concern lies in systematic soil fertility enhancement. Practices such as straw incorporation and organic fertilizer application—which typically yield limited short-term benefits in traditional models and are therefore often underutilized—tend to deliver more pronounced yield benefits under “extremely dense planting”. This improved responsiveness can increase farmer acceptance, providing strong support for maintaining soil fertility and promoting sustainable agricultural development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft, and funding acquisition, D.W.; conceptualization and writing—original draft, S.C.; investigation and validation, X.L., F.W., X.Y., and W.P.; conceptualization, writing—review, editing, supervision, and project administration, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD2301402), and Anhui Science and Technology University Talent Introduction Program (ZHYJ202301).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, Y.X.; Chen, Y.F.; Searchinger, T.D.; Zhou, M.; Pan, D.; Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; et al. Air quality, nitrogen use efficiency and food security in China are improved by cost-effective agricultural nitrogen management. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.R.; Li, T.Y.; Cao, H.B.; Zhang, W.F. Research on the driving factors of fertilizer reduction in China. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2020, 26, 561–580. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.T.; Liu, Y.N.; Dai, X.L.; Song, S.; Wang, L.J.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y.L.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhang, G.Z.; Wei, X.H.; et al. Effects of interaction between nitrogen rate and planting density on pest and disease occurrence, yield, and nitrogen use efficiency of wheat in east Shandong. J. Shanxi Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Li, G.H.; Lu, W.P.; Lu, D.L. Increasing planting density and decreasing nitrogen rate increase yield and nitrogen use efficiency of summer maize. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2020, 26, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.X.; Chen, S.Y.; Yuan, X.F.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xia, J.L.; Wang, J.F. Research progress on the synergistic effects of nitrogen nutrition and cultivation density of rice and the “extremely dense planting” technology. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2024, 30, 2000–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Ai, C.; Yi, K.K. Research focus of plant nutrition and fertilizer science in new stage. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2024, 30, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.X.; Shen, J.B.; Cui, Z.L.; Zhang, F.S. Advances and Prospects of Plant Nutrition. J. Agric. 2018, 8, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Jiang, Z.M.; Wang, W.; Qiu, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.H.; Liu, Y.Q.; Li, A.F.; Gao, X.K.; Liu, L.C.; Qian, Y.W.; et al. Nitrate-NRT1.1B-SPX4 cascade integrates nitrogen and phosphorus signalling networks in plants. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Mao, C.Z. Phosphate uptake and transport in plants: An elaborate regulatory system. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Hu, B.; Chu, C.C. Nitrogen assimilation in plants: Currentstatus and future prospects. J. Genet. Genom. 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G. Iron uptake, signaling, and sensing in plants. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Liu, J.; Cao, B.L.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.P.; Chen, Z.Y.; Dong, C.Q.; Liu, X.Q.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, W.X.; et al. Reducing brassinosteroid signalling enhances grain yield in semi-dwarf wheat. Nature 2023, 617, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.N.; Zhang, Y.X.; Jia, X.Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.B.; Liu, J.F.; Yang, Q.S.; Ruan, W.Y.; Yi, K.K. Alternative splicing of REGULATOR OF LEAF INCLINATION 1 modulates phosphate starvation signaling and growth in plants. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3319–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Zhang, H.; Yu, C.; Luo, N.; Yan, J.J.; Zheng, S.; Hu, Q.L.; Zhang, D.H.; Kou, L.Q.; Meng, X.B.; et al. Low phosphorus promotes NSP1-NSP2 heterodimerization to enhance strigolactone biosynthesis and regulate shoot and root architecture in rice. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1811–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.T.; Jin, Y.; Deng, L.X.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Qu, H.Y.; Zhang, S.N.; Liu, Y.; et al. The transcription factor MYB110 regulates plant height, lodging resistance, and grain yield in rice. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 298–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tateishi-Karimata, H.; Endoh, T.; Jin, Q.L.; Li, K.X.; Fan, X.R.; Ma, Y.J.; Gao, L.M.; Lu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; et al. High-temperature adaptation of an OsNRT2.3 allele is thermoregulated by small RNAs. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadc9785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, W.; Ou, S.J.; Tang, J.Y.; Li, H.; Che, R.H.; Zhang, Z.H.; Chai, X.Y.; Wang, H.R.; Wang, Y.Q.; et al. Variation in NRT1.1B contributes to nitrate-use divergence between rice subspecies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, H.R.; Jiang, Z.M.; Wang, W.; Xu, R.N.; Wang, Q.H.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, A.F.; Liang, Y.; Ou, S.J.; et al. Genomic basis of geographical adaptation to soil nitrogen in rice. Nature 2021, 590, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Wang, M.Y.; Hu, S.J.; Zhang, X.D.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, G.L.; Huang, B.; Zhao, S.W.; Wu, J.S.; Xie, D.T.; et al. Economics- and policy-driven organic carbon input enhancement dominates soil organic carbon accumulation in Chinese croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4045–4050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.J.; Wang, G.C.; Wang, E.L.; Liu, S.L.; Chang, J.F.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, H.X.; Wei, Y.C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Spatiotemporal co-optimization of agricultural management practices towards climate-smart crop production. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.L.; Zhang, X.M.; Reis, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; He, P.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Gu, B.J. Nitrogen cycles in global croplands altered by elevated CO2. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.M.; Yu, M.J.; Chen, H.H.; Zhao, H.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Su, W.Q.; Xia, F.; Chang, S.X.; Brookes, P.C.; Dahlgren, R.A.; et al. Elevated temperature shifts soil N cycling from microbial immobilization to enhanced mineralization, nitrification and denitrification across global terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 5267–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.M.; Singh, B.K. Plant-microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Oliverio, A.M.; Brewer, T.E.; Benavent-González, A.B.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Maestre, F.T.; Singh, B.K.; Fierer, N. A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil. Science 2018, 359, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.M.; Hughes, D.J.; Fu, Q.L.; Abadie, M.; Hirsch, P.R. Metagenomic approaches reveal differences in genetic diversity and relative abundance of nitrifying bacteria and archaea in contrasting soils. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, M.; Six, J. Soil structure and microbiome functions in agroecosystems. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.M.; Liu, G.F.; Chen, H.H.; Chen, C.R.; Wang, J.K.; Ai, S.Y.; Wei, D.; Li, D.M.; Ma, B.; Tang, C.X.; et al. Long-term nutrient inputs shift soil microbial functional profiles of phosphorus cycling in diverse agroecosystems. ISME J. 2020, 14, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.J.; Rensing, C.; Han, D.F.; Xiao, K.Q.; Dai, Y.X.; Tang, Z.X.; Liesack, W.; Peng, J.J.; Cui, Z.L.; Zhang, F.S. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals distinct phosphorus acquisition strategies between soil microbiomes. mSystems 2022, 7, e01107-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Kuramae, E.E.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.P.; Fei, J.C.; Rong, X.M.; Peng, J.W.; Yin, L.C.; Zhou, X.; Luo, G.W. Enhanced productivity of maize through intercropping is associated with community composition, core species, and network complexity of abundant microbiota in rhizosphere soil. Geoderma 2024, 442, 116786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Png, G.K.; Ostle, N.J.; Zhou, H.; Hou, X.; Luo, C.; Quinton, J.N.; Schaffner, U.; Sweeney, C.; Wang, D.; et al. Grassland degradation-induced declines in soil fungal complexity reduce fungal community stability and ecosystem multifunctionality. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 176, 108865. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, J.K.; McClure, R.; Egbert, R.G. Soil microbiome engineering for sustainability in a changing environment. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, X.N.; Hu, B.; Qin, Y.; Xu, H.R.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.X.; Qian, J.M.; et al. Root microbiota shift in rice correlates with resident time in the field and developmental stage. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Zhu, Y.G.; Wang, J.T.; Singh, B.; Han, L.L.; Shen, J.P.; Li, P.P.; Wang, G.B.; Wu, C.F.; Ge, A.H.; et al. Host selection shapes crop microbiome assembly and network complexity. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.L.; Gao, L.M.; Kong, Y.L.; Hu, X.Y.; Xie, K.L.; Zhang, R.Q.; Ling, N.; Shen, Q.S.; Guo, S.W. Improving rice population productivity by reducing nitrogen rate and increasing plant density. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, E0182310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.P.; Xu, Z.H.; Chen, L.; Xun, W.B.; Shu, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, X.L.; Wang, Z.Q.; Ren, Y.; Shen, Q.R.; et al. Root colonization by beneficial rhizobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 48, fuad066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, T.; Friman, V.P.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Jousset, A. Trophic network architecture of root-associated bacterial communities determines pathogen invasion and plant health. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.P.; Cui, Z.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Bai, J.S.; Meng, Q.F.; Hou, P.; Yue, S.C.; Römheld, V.; et al. Integrated soil-crop system management for food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6399–6404. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Lan, L.Y.; Jin, Y.; Yu, N.; Wang, D.; Wang, E. Mechanisms underlying legume-rhizobium symbioses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 244–267. [Google Scholar]

- Berrios, L.; Yeam, J.; Holm, L.; Robinson, W.; Pellitier, P.T.; Chin, M.L.; Henkel, T.W.; Peay, K.G. Positive interactions between mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria are widespread and benefit plant growth. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 2878–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.Z.; Xue, C.; Penton, C.R.; Thomashow, L.S.; Shen, Q. Suppression of banana Panama disease induced by soil microbiome reconstruction through anintegrated agricultural strategy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 128, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.S.; Lv, N.; Deng, X.H.; Xiong, W.; Shen, Z.Z.; Zhang, N.; Geisen, S.; Li, R.; et al. Additive fungal interactions drive biocontrol of Fusarium wilt disease. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1198–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.H.; Ke, R.Y.; Yang, T.; Song, J. pH-responsively water-retainingcontrolled-release fertilizer using humic acid hydrogel and nano-silica aqueous dispersion. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 2286–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclaren, C.; Mead, A.; Balen, D.; Claessens, L.; Etana, A.; Haan, J.; Haagsma, W.; Jck, O.; Keller, T.; Labuschagne, J. Long-term evidence for ecological intensification as a pathway to sustainable agriculture. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.L.; Cao, L.; Yang, Y.; Ti, C.P.; Liu, Y.Z.; Smith, P.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Lehmann, J.; Lal, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; et al. Integrated biochar solutions can achieve carbon-neutral staple crop production. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakpa, E.P.; Xie, J.M.; Zhang, J.; Han, K.N.; Ma, Y.F.; Liu, T.D. Influence of soil amendment of different concentrations of amino acid water-soluble fertilizer on physiological characteristics, yield and quality of “Hangjiao No. 2” chili pepper. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.J.; Zhao, J.C.; Yang, Z.Y. Effects of compound fertilizer decrement and water-soluble humic acid fertilizer application on soil properties, bacterial community structure, and shoot yield in lei bamboo (Phyllostachys praecox) plantations in subtropical China. Forests 2024, 15, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Zhu, S.C.; Yang, X.; Weston, M.V.; Wang, K.; Shen, Z.Q.; Xu, H.W.; Chen, L. Nitrogen diagnosis based on dynamic characteristics of rice leaf image. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, J.; Fu, Z.; Wang, W.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X. Integrating phenology information with UAV multispectral data for rice nitrogen nutrition diagnosis. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 169, 127696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Xu, D.; He, L.; Feng, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Coburn, C.A.; Guo, T. Using multi-angle hyperspectral data to monitor canopy leaf nitrogen content ofwheat. Precis. Agric. 2016, 17, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Mistele, B.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Schmidhalter, U. Reflectance estimation ofcanopy nitrogen content in winter wheat using optimised hyperspectral spectralindices and partial least squares regression. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 52, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Qiang, L.; He, S.L.; Yi, S.L.; Liu, X.F. Prediction of nitrogen andphosphorus contents incitrus leavesbased onhyperspectral imaging. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2015, 8, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.S.; Li, R.G. Principles and Practices of Farmland Fertilization; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Xu, X.P.; Ding, W.C.; Zhou, W. Principles and practices of intelligent fertilizer recommendation based on yield response and agronomic efficiency. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2023, 29, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.L.; Li, J.S.; Zhang, B.; Spyrakos, E.; Tyler, A.N.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, F.F.; Kutser, T.; Lehmann, M.K.; Wu, Y.H.; et al. Trophic state assessment of global inland waters using a MODIS-derived Forel-Ule index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xu, W.; Lu, X.K.; Zhong, B.Q.; Guo, Y.X.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Y.H.; He, W.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; et al. Exploring global changes in agricultural ammonia emissions and their contribution to nitrogen deposition since 1980. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2121998119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Xu, M.; Li, R.; Zheng, L.; Liu, S.; Reis, S.; Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H. Optimizing nitrogen fertilizer use for more grain and less pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.T.; Geng, Y.b.; Liang, T. Optimization of reduced chemical fertilizer use in tea gardens based on the assessment of related environmental and economic benefits. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulhánek, M.; Asrade, D.A.; Suran, P.; Sedlář, O.; Černý, J.; Balík, J. Plant Nutrition-New Methods Based on the Lessons of History: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlár, O.; Balík, J.; Kulhánek, M.; Cerny, J.; Suran, P.; Sedlár, O. Sulphur nutrition index in relation to nitrogen uptake and quality of winter wheat grain. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 79, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.B.; Li, X.; Lu, Z.F.; Zhang, H.; Ye, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.Y.; Pei, H.C.; Duan, F.Y.; et al. A transcriptional regulator that boosts grain yields and shortens the growth duration of rice. Science 2022, 377, eabi8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Yu, X.P.; Li, W.R.; Wang, K.j.; Zhan, G.J.; Yu, Y.Q. Research advance in the roles of water and nitrogen interaction on rice growth and development, carbon and nitrogen metabolism, nitrogen absorption and utilization. North Rice 2025, 55, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, T.T.; Ma, C.; Li, X.h.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.C. Response of growth and nitrogen metabolism of cucumber seedlings to different exogenous nitrate nitrogen levels under low temperature stress. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2025, 31, 564–577. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S.; Yanagisawa, S. Characterization of metabolic states of Arabidopsis thaliana under diverse carbon and nitrogen nutrient conditions via targeted metabolomic analysis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingler, A.; Henriques, R. Sugars and the speed of life-Metabolic signals that determine plant growth, development and death. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13656. [Google Scholar]

- Hafiz, F.B.; von Tucher, S.; Rozhon, W. Plant Nutrition: Physiological and Metabolic Responses, Molecular Mechanisms and Chromatin Modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Huang, N.; Zhong, X.; Mai, G.; Pan, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liang, K.; Pan, J.; Xiao, J.; et al. Improving grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency of direct-seeded rice with simplified and nitrogen-reduced practices under a double-cropping system in South China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 5727–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Zhong, X.H.; Huang, N.R. Effect of Three Controls Nutrient Management Technology on Growth, Development and Nitrogen Uptake of Rice. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2010, 26, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S.B.; Zhang, J.L.; Gao, H.X.; Wang, C.B. Advances and prospects of high-yield peanut cultivation in China. Acta Agron. Sin. 2025, 51, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Guo, F.; Li, D.W.; Yang, S.; Geng, Y.; Meng, J.J.; Li, X.G.; Wan, S.B. Effects of three prevention and three promotion regulation techniques on economical characteristics and yield of high yield peanut. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2018, 40, 828–834. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.J.; Li, G.H.; Xue, L.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Xu, H.G.; Wang, S.H.; Yang, L.Z.; Ding, Y.F. Subdivision of nitrogen use efficiency of rice based on 15N tracer. Acta Agron. Sin. 2014, 40, 1424–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzueta, I.; Abeledo, L.G.; Mignone, C.M.; Miralles, D.J. Differences between wheat and barley in leaf and tillering coordination under contrasting nitrogen and sulfur conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2012, 41, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, P.W.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Lilley, J.M.; Gregory, P.J.; Rebetzkek, G.J. A tillering inhibition gene influences root-shoot carbon partitioning and pattern of water use to improve wheat productivity in rainfed environments. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Lin, S.X.; Ma, G.R. Nitrogen nutrition of paddy rice plant and its diagnosis. J. Zhejiang Agric. Univ. 1981, 7, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.L.; Zou, Y.B.; Peng, S.B.; Buresh, R.J. Nitrogen uptake distribution by rice and its losses from plant tissues during. Plant Nutr. Fertil. Sci. 2004, 10, 579–583. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Smith, S.; Li, J. Genetic Regulation of Shoot Architecture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Zhu, L.M.; Shen, C.B.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, H.P.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.P.; Yang, N.; He, Y.B.; et al. Natural allelic variation in a modulator of auxin homeostasis improves grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 566–580. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.