Abstract

Weed competition in red beet (Beta vulgaris L. Conditiva Group) directly reduces crop yield and quality, making detection and eradication essential. This study proposed a three-phase experimental protocol for multi-class detection (cultivation and six types of weeds) based on RGB (red-green-blue) colour images acquired in a greenhouse, using state-of-the-art deep learning (DL) models (YOLO and RT-DETR family). The objective was to evaluate and optimise performance by identifying the combination of architecture, model scale and input resolution that minimises false negatives (FN) without compromising robust overall performance. The experimental design was conceived as an iterative improvement process, in which each phase refines models, configurations, and selection criteria based on performance from the previous phase. In phase 1, the base models YOLOv9s and RT-DETR-l were compared at 640 × 640 px; in phase 2, the YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, YOLO12s and RT-DETR-l models were compared at 640 × 640 px and the best ones were selected using the F1 score and the FN rate. In phase 3, the YOLOv9 (s = small, m = medium, c = compact, e = extended) and YOLOv10 (s = small, m = medium, l = large, x = extra-large) families were scaled according to the number of parameters (s/m/c-e/l-x sizes) and resolutions of 1024 × 1024 and 2048 × 2048 px. The best results were achieved with YOLOv9e-2048 (F1: 0.738; mAP@0.5 (mean Average Precision): 0.779; FN: 28.3%) and YOLOv10m-2048 (F1: 0.744; mAP@0.5: 0.775; FN: 27.5%). In conclusion, the three-phase protocol allows for the objective selection of the combination of architecture, scale, and resolution for weed detection in greenhouses. Increasing the resolution and scale of the model consistently reduced FNs, raising the sensitivity of the system without affecting overall performance; this is agronomically relevant because each FN represents an untreated weed.

1. Introduction

Red beet (Beta vulgaris L., Conditiva Group) is a root vegetable eatable with high nutritional value and increasing demand in both fresh markets and the food-processing industry [1]. Its production has become established in temperate regions worldwide due to its adaptability and economic value. However, as with other horticultural crops, its yield is severely affected by competition with weed species that emerge simultaneously during the early phenological stages [1]. These weeds compete for essential resources such as water, light, nutrients, and space, reducing not only total yield but also the commercial quality of the roots. According to recent studies, weed interference can cause yield losses that in some cases exceed 42% when no adequate control is implemented [2]. Currently, the most widely used methods for weed control in red beet are pre- and post-emergence herbicide applications and, to a lesser extent, mechanical weeding. However, both approaches present significant limitations. The indiscriminate use of herbicides poses environmental and health risks [3], while manual or mechanical weeding entails high operating costs, making it economically unfeasible to sustain these crops, particularly on small and medium-sized farms. This situation has motivated the development of intelligent management systems, among which precision weeding stands out. This strategy enables localized herbicide application only where weeds are detected, thereby optimizing resource use and reducing environmental impact. The basis of these systems is the ability to automatically and reliably identify weeds in crop images. However, this task is challenging due to the high visual similarity between beet leaves and those of particular broadleaf weed species, as well as additional factors such as occlusion, morphological variability, and changing illumination conditions [4]. In view of these challenges, deep learning (DL) approaches, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have become increasingly relevant.

In automatic weed detection using computer vision, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are at the core of most modern detectors, learning hierarchical representations of the image from local filters applied to specific regions [5,6]. This capability allows them to capture everything from basic patterns (edges, texture) to complex morphological features associated with plant structures, which are decisive in discriminating between crops and weeds in multi-class scenarios [7]. In precision agriculture, CNN-based DL has become particularly established in detection and localization tasks due to its speed and accuracy in species identification and its integration with acquisition platforms such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and tractor-mounted systems, which facilitates deployment under biological variability and lighting changes typical of operating conditions [8,9,10,11]. As a result, more accurate and efficient automatic weeding systems have been developed, where the quality of detection directly determines the effectiveness of selective intervention [12,13,14]. In this context, various studies have demonstrated the potential of DL to support site-specific weed detection, segmentation, and control in different crops, enabling targeted herbicide applications or assisted mechanical weeding [15,16]. To this end, models capable of real-time operation on robotic platforms and embedded systems have been proposed, seeking a balance between performance and computational cost [17,18,19]. More recently, the incorporation of attention mechanisms and hybrid schemes has shown improvements in dealing with occlusions, overlaps, and lighting variations, factors that dominate errors in weed detection and limit its use in real-world scenarios [20,21]. Taken together, this evidence positions deep learning-based automatic weed detection as a key component in reducing chemical inputs and improving agronomic efficiency in precision control strategies.

Regarding the application of DL in beet cultivation, recent advances have focused mainly on the sugar variety (Beta vulgaris L. var. saccharifera), due to the availability of datasets and its industrial relevance, as well as a reference model for developing and validating weed detection and classification algorithms in real agricultural environments [22,23,24]. In contrast, red beet (Beta vulgaris L., Conditiva Group), although it shares morphological similarities with the sugar variety, presents distinctive chromatic, structural, and phenotypic traits, such as the reddish coloration of its tissues, greater variability in leaf reflectance, and a more compact growth habit, which may affect the performance and generalization capacity of models trained in other domains. The scarcity of specific studies on this variety reveals a scientific and technological gap in applying DL to intelligent weed management in this crop. Consequently, the available related literature focuses mainly on sugar beet, where approaches have been explored that integrate detection and segmentation networks with spectral information derived from the red and near-infrared (NIR) bands, taking advantage of the crop–weed contrast to improve the discrimination and robustness of the system under operational conditions. Among these studies, the work of Sunil et al. [25] stands out, in which DL models were trained for site-specific herbicide application, implementing YOLOv8 and YOLOv9 models, and a customised lightweight version (YOLOv9_CW5) for the multi-species detection of crops and weeds in real field conditions using ground robots (Weedbot and Mini Weedbot). Their system, trained on RGB images collected at four locations in North Dakota, achieved mAP@0.5 values of 78.4–83.9% and up to 96.9% for specific detections such as beet and maize. The lightweight version (YOLOv9_CW5) maintained competitive performance with only 26.5 GFLOPs, demonstrating its viability for integration into robotic platforms and real-time intelligent spraying systems.

As additional context, various studies on beet cultivation show that deep learning has provided solutions beyond object detection, also incorporating segmentation approaches and other computer vision tasks; Hu et al. [26] developed ATT-NestedUNet, an enhanced UNet++ model integrating the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to discriminate sugar beet plants and weeds under field conditions, achieving 91.42% mIoU on 1026 BoniRob images and reducing false positives and background noise. Likewise, Liu et al. [27] proposed a real-time semantic segmentation model with a ResNet18-based multi-branch design and fusion modules to improve spatial discrimination, reporting mIoU values of 0.713–0.906 on datasets such as BoniRob and CWFID, and 93.6 FPS on a GTX1050 GPU. In a practical site-specific application, Spaeth et al. [28] evaluated a smart sprayer based on RGB segmentation with an R/NIR filter (without deep neural networks or species classification), obtaining control efficiencies of 72–99%, herbicide savings of 10–55%, and yield increases of up to 15% in beet, maize, and sunflower, supporting the relevance of vision-based strategies for precision weed management in row crops. In Ortatas et al. [29], a hybrid deep learning approach was proposed for selective weed identification in sugar beet fields using 1336 RGB images. The system, based on Faster R-CNN and Federated Learning, showed robustness under illumination changes and occlusions, supporting the feasibility of automated weed detection in open-field conditions.

In this context, the present study aims to evaluate and adapt DL models for automated weed detection in red beet, analyzing their performance and their potential integration into precision weeding systems. The results are intended to provide empirical evidence to support the optimization of computer vision models aimed at reducing herbicide use, improving operational efficiency, and strengthening the sustainability of horticultural production in high-value crops.

The paper is organized into four main sections. Section 1 presents the introduction and theoretical background, highlighting the relevance of DL and CNNs in automated weed detection, with emphasis on advances achieved in beet crops. Section 2 describes in detail the materials and methods employed, including the experimental design, the biological material used, the image acquisition and annotation process, and the model configurations and evaluation metrics. Section 3 presents the results obtained and their comparative analysis, examining the performance of the different CNN architectures for weed detection under controlled greenhouse conditions. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions of the study, highlighting the main contributions, observed limitations, and future perspectives for implementing computer vision systems for precision weeding in high-value horticultural crops such as red beet (Beta vulgaris L., Conditiva Group). The major contributions of this work are as follows: (1) build a greenhouse RGB dataset for red beet (1630 annotated images; crop + six weed classes) in YOLO format; (2) we propose a three-phase protocol to select architecture, model scale, and input resolution using operationally relevant criteria with emphasis on reducing false negatives; (3) we evaluate multiple YOLO versions (v8–v12) and RT-DETR-l under the same acquisition setting and quantify the effect of scaling and resolution (1024 and 2048 px); and (4) we analyze error modes using precision–recall behavior and confusion patterns to identify candidate configurations for subsequent field validation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material and Experimental Setup

The experiment was conducted in a climate-controlled greenhouse at the La Yutera campus (41.988799° N, 4.513528° W), University of Valladolid, Palencia, Spain, under controlled temperature (24 °C) and relative humidity (60%) conditions. Agronomic management consisted of frequent irrigation to ensure proper crop establishment and development.

A total of 150 seeds of red or red beet (Beta vulgaris L., Conditiva Group, cv. Kestrel F1) (Figure 1) were sown in substrate placed on raised beds. The plants were kept in the trial until the end of the vegetative period (40 days after sowing), a critical stage in beet cultivation. During this early stage, seedlings exhibit slow growth and limited canopy cover, making them highly susceptible to competition from weeds, which tend to emerge and develop more rapidly [30]. Under these conditions, if timely management is not implemented, young beet plants may be overgrown by weeds, compromising both crop establishment and potential yield [31]. Six weed species were established: Solanum nigrum, Sonchus oleraceus, Lolium rigidum, Chenopodium album, Conyza canadensis, and Sinapis arvensis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative samples of the crop and weed classes.

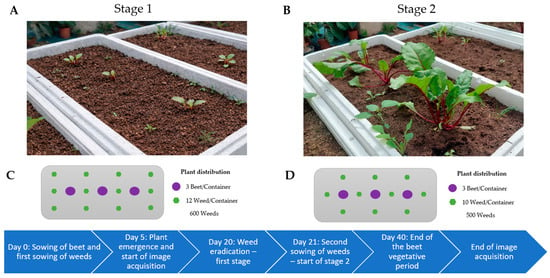

The experiment was structured into two consecutive stages covering the period from sowing to the end of the beet vegetative cycle. The first stage comprised simultaneous crop sowing and the introduction of the first weed, followed by the start of image acquisition after emergence and the controlled removal of weeds (Figure 2A). The second stage began with a new weed sowing to simulate late-season interference and extended until the end of the vegetative period (Figure 2B). This design enabled the capture of different phenological conditions and levels of crop–weed competition under controlled conditions. Figure 2 summarizes the full timeline of the sowing process and weed management and serves as a reference for the detailed description of each stage provided below.

Figure 2.

Panoramic view and floor plan of the greenhouse experiment for detecting weeds in red beets: Stage 1 (A,C) and Stage 2 (B,D).

- Stage 1 (0–20 days): The six weed species were sown randomly, with six plants distributed around each beet plant, resulting in twelve individuals per container and a total of 600 weed plants (Figure 2C). On day 20, these were eradicated to avoid excessive competition with the crop and to simulate early weeding under commercial conditions.

Image Acquisition Setup

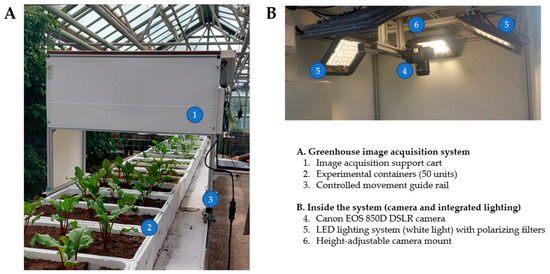

For image acquisition, a support cart was installed on the raised bed in the greenhouse and moved along a linear guide rail system, enabling controlled, stable motion (Figure 3A). This cart housed the image-acquisition system, consisting of a Canon EOS 850D digital single-lens reflex camera (Ohta-ku, Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with a 22.3 × 14.9 mm CMOS sensor, positioned 1 m above the substrate. The camera was used together with an EF-S 15–55 mm f/4–5.6 IS STM lens (Tanzi, Canon Inc., Taichung, Taiwan) fitted with a 58 mm circular polarizing filter (PL-C) (Tanzi, Canon Inc., Taichung, Taiwan) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Support cart for image acquisition in red beet cultivation. (A) Overview of the acquisition system. (B) Interior view showing the camera and integrated lighting.

Illumination was provided by two white LED lamps (6000 K), each configured as a 6 × 6 diode matrix. To minimize reflections on the leaf surface, both lamps were covered with a ROSCO polarizing filter (Rosco Laboratories Inc., Stamford, CT, USA), (38% transmission, equivalent to 1.5 f/stops). RGB images with a resolution of 6000 × 4000 pixels were captured over 35 consecutive days, from seedling emergence (day 5) to the end of the vegetative period (day 40).

2.2. Three-Phase Methodological Design for Architecture Selection

An experimental procedure divided into phases was implemented to evaluate the most efficient architectures for weed detection in red beet crops, prioritizing model performance and stability. Each phase was guided by the results obtained in the previous stage. In this way, decisions about training configurations, the incorporation of new architectures, model scaling, and the application of pre-processing techniques were made progressively based on experimental evidence. This strategy allowed not only a comparative evaluation of performance but also adaptive adjustments until more stable and consistent configurations were achieved.

2.2.1. Selection of Architectures

The choice of architectures for weed detection in red beet was based on the results reported by García et al. [32], who evaluated different detection models in maize crops. In that study, architectures from the YOLO family (YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, YOLOv10s, and YOLO11s), as well as the transformer-based RT-DETR-l model, were trained to identify four weed species. The findings showed that the best-performing configurations corresponded to YOLOv9s and RT-DETR-l. In particular, YOLOv9s achieved competitive performance, with an mAP@0.5 of 0.834, reflecting a high detection capability, and an F1-score of 0.78, indicating an adequate balance between precision and recall. In turn, RT-DETR-l stood out as the model with the best overall balance, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 0.828 and a higher F1-score of 0.80, denoting an optimal trade-off between precision and recall.

2.2.2. Phase 1: Baseline Configuration

The initial training was performed with YOLOv9s and RT-DETR-l, using the parameters defined by García et al. [32]; A maximum of 300 epochs was set, with Early Stopping as a regularization technique and a patience of 20 epochs. This configuration allowed training to stop automatically when no further improvement in validation loss was observed, thus preventing overfitting and optimizing computational resources. The batch size was fixed at 32, a value that balances training speed and generalization capacity. Although the original images had higher resolution, they were rescaled to 640 × 640 pixels to align with YOLO’s internal processing. The optimization parameters were set to lr0 = 0.01, lrf = 0.01, weight decay = 0.0005, momentum = 0.937, and IoU = 0.7. The remaining hyperparameters were kept at the default values recommended by the reference implementation [33].

The dataset was split into three subsets: 70% for training (1140 images), 12% for testing (200 images), and 18% for validation (290 images). The partitioning was performed stratified by class, so that the proportions of crop instances and each weed type remained as similar as possible across the three subsets, thereby avoiding extreme imbalances in minority classes. In addition, the temporal structure of the experiment (stages and acquisition days) was taken into account, ensuring that all three partitions included images from both stages and at different points in the crop cycle. This reduced the risk of temporal biases and dependencies between subsets.

2.2.3. Phase 2: Extended Architecture Evaluation

In this phase, the range of evaluated models was expanded by incorporating YOLOv8s, YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, and YOLO12s. The objective of this extension was to explore whether other architectures in the YOLO family, with structural modifications to the backbone network and feature aggregation mechanisms, could improve weed detection while addressing the limitations observed in Phase 1. To ensure the comparability of results, the same training configuration used in Phase 1 was maintained (300 epochs, early stopping with a patience of 20, batch size of 32, 640 × 640 pixel resolution, lr0 = 0.01, lrf = 0.01, weight decay = 0.0005, momentum = 0.937, and IoU = 0.7). In this way, differences in model performance could be attributed to the architectures themselves rather than to variations in the experimental procedure.

The choice of these architectures was based on their relevance in the state of the art: YOLOv8 represents the first optimized generation from Ultralytics, with improvements in the efficiency of anchor-free detection, whereas YOLOv10 and YOLO11 incorporate optimizations in feature fusion modules and loss-balancing strategies to improve recall. YOLO12, in turn, integrates recent innovations in attention mechanisms and efficient learning, making it an interesting candidate for agricultural scenarios with high background variability. This phase aimed to determine whether any of these architectures could outperform YOLOv9s under homogeneous training conditions and, in particular, whether they would exhibit greater generalization with respect to the background confusion issues previously identified.

2.2.4. Phase 3: Model Scaling and Input Resolution

Based on the results of the previous phase, in which YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 were identified as the architectures with the best overall performance, a new stage was launched to assess the impact of structural scaling and input resolution on the detection system’s performance. To this end, the higher-capacity variants of each architecture were trained: YOLOv9 in its s, m, c, and e versions, and YOLOv10 in its s, m, l, and x versions. The objective was to analyse whether increasing the structural complexity of the model, expressed in a larger number of parameters and a deeper network (Table 1), could lead to substantial improvements in precision, stability, and generalization capacity during weed detection.

Table 1.

Model and resolution configurations used for the YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 variants.

At the same time, the image input resolution was increased from the standard format to 1024 × 1024 and 2048 × 2048 pixels to analyse how the additional spatial detail affects the detection of small structures, such as leaf edges and partial occlusions. This adjustment was intended to find a balance point between higher visual precision and computational feasibility, given that higher resolutions entail a significant increase in resource consumption in computer vision systems designed for precision weeding.

This procedure made it possible to comprehensively analyse the interaction between architectural complexity and visual resolution, assessing their impact on key performance metrics (F1-score, FN%, and mAP@0.5).

2.3. Experimental Settings

2.3.1. Image Preprocessing and Annotation

To build the dataset RedBeetWeedSet-1630 (RBWS-1630), a selection and cleaning process was carried out. Images with a high degree of blur or in which the beet plant had grown beyond the camera’s field of view—mainly observed during the last days of the vegetative period—were discarded. In total, 120 images were removed, resulting in a final set of 1630 images suitable for training.

Image annotation was performed using the open-source LabelImg 1.8.6 tool, which generates annotations in YOLO format (Figure 4). Seven classes were defined, corresponding to the crop and the established weed species, with the following abbreviations: Beet: (Beta vulgaris L. Conditiva Group Kestrel F1); Weed1: Solanum nigrum, Weed2: Sonchus oleraceus, Weed3: Lolium rigidum, Weed4: Chenopodium album, Weed5: Conyza canadensis, Weed6: Sinapis arvensis. Experts in weed identification carried out the annotation process.

Figure 4.

Interface and image annotation process using LabelImg.

The dataset RBWS-1630 resulting from the selection and annotation process was divided into three subsets, preserving the original class distribution to ensure representativeness: 70% for training (1140 images), 12% for testing (200 images), and 18% for validation (290 images). This data partitioning is consistent with the standard practice reported in the literature for deep learning–based object detection tasks [5], where the largest proportion of samples is reserved for training (typically between 60% and 80%) and the remainder is distributed between validation and independent testing (often between 10% and 20% each) [34], in order to balance adequate model fitting with robust and unbiased evaluation of its performance.

2.3.2. Experimental Environment

Model training was carried out on the high-performance computing (HPC) systems of the Castilla y León Supercomputing Center (SCAYLE, León, Spain), using nodes equipped with NVIDIA H100 GPUs (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, California, USA) optimized for computer vision workloads. This environment significantly reduced processing times and enabled parallel management of multiple experiments via the Slurm workload manager. The training setup is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Configuration used for model training.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

2.4.1. Confusion Matrix Indicators (Precision, Recall, F1, FP%, FN%)

The confusion matrix is a fundamental tool for analysing the performance of classification models, especially in multiclass problems [35]. In this context, it organises model predictions versus true labels into a matrix C of size K × K, where K is the number of classes, and each element Cij counts the number of instances whose true class is i and that are predicted as class j. From this global matrix, metrics are computed per class, treating each class k as “positive” and grouping the rest as “negative” (one-vs-rest approach). For each class k, the following quantities are defined:

- True Positive (TPk): instances of class k that are correctly classified as k.

- False Positive (FPk): instances of other classes that the model incorrectly predicts as k.

- False Negative (FNk): instances of class k that the model assigns to a different class.

- True Negative (TNk): instances of all other classes that are correctly not assigned to k.

Based on the per-class counts in the confusion matrix, performance metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score are computed for each class [35], allowing the behaviour of the model to be assessed individually for each class.

- Precision: proportion of correctly predicted positive instances with respect to the total number of positive predictions made, Equation (1).

- Recall: measures the ability of the model to correctly identify positive instances, Equation (2).

- F1-score: corresponds to the harmonic mean between precision and recall and is particularly useful in scenarios with imbalanced classes, Equation (3).

2.4.2. Intersection over Union (IoU) Metric

The Intersection over Union (IoU) metric quantifies the overlap between a predicted bounding box and the ground-truth box [36,37]. It is computed as the ratio between the area of intersection and the area of the union of both boxes (Equation (4)).

The IoU value ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates a perfect match and 0 indicates no overlap. In object detection tasks, predefined thresholds are commonly used, with 0.5 being the most typical:

- IoU ≥ 0.5: the prediction is considered a True Positive (TP).

- IoU < 0.5: the prediction is classified as a False Positive (FP).

- IoU = 0: when there is no prediction for a ground-truth object, it is counted as a False Negative (FN).

The use of IoU has become a standard evaluation criterion for object localization in detection models.

2.4.3. Average Precision (AP) and Mean Average Precision (mAP)

Average Precision (AP) is a widely used metric in object detection that captures the trade-off between precision and recall across different confidence levels. It is computed as the area under the PR curve for a given class. An AP value close to 1 denotes outstanding performance, whereas low values indicate difficulties in balancing both metrics [36,37] (Equation (5)).

where:

N: is the number of sampled points on the PR curve.

Rn: is the recall at point n.

Rn − 1: is the recall at the previous point (n − 1).

Pn: is the precision at point n.

The mean Average Precision (mAP) is obtained by averaging the AP values over all classes (Equation (6)) and is the most widely used reference metric for comparing object detection models.

where:

N: is the total number of classes.

APi: is the Average Precision of class i.

2.4.4. Precision–Recall (PR) Curve

The Precision–Recall (PR) curve is widely used to evaluate classification and object detection models, particularly in scenarios with imbalanced classes [38]. This curve shows the relationship between precision and recall as the model’s confidence threshold is varied. An ideal model maintains high values for both metrics across different thresholds, resulting in a curve close to the upper-right corner [39]. From the PR curve, metrics such as Average Precision (AP)—the area under the curve for a specific class—and mean Average Precision (mAP)—the average of AP across all classes—are derived. Both metrics are standard criteria for comparing object detection models.

3. Results and Analysis

The following subsections present the results from each phase, highlighting the performance of the evaluated architectures and the experimental decisions that guided the study.

3.1. Results Phase 1: Baseline Configuration (YOLOv9s vs. RT-DETR-l, 640 × 640)

3.1.1. Performance of the YOLOv9s Baseline Configuration

The YOLOv9s model achieved moderately satisfactory overall performance in detecting the beet crop and the six weed classes (Table 3), with an average F1-score of 0.686 and an mAP@0.5 of 0.688. These metrics indicate an acceptable level of accuracy, although still insufficient for an operational in-field weed control system. Overall precision (0.711) and recall (0.665) values indicate balanced performance, but with a tendency to miss true instances (FN = 28.9%), which is critical in agricultural contexts, where each missed detection represents an uncontrolled weed and therefore a potential yield loss.

Table 3.

Performance metrics of the YOLOv9s model for crop and weed detection.

The model showed strong discriminative ability for the classes Beet, Weed3, and Weed6, with F1-scores ranging from 0.740 to 0.752, indicating stable performance for species with well-defined morphology and high chromatic contrast. However, classes Weed4 (Chenopodium album) and Weed5 (Conyza canadensis) recorded the lowest values (0.654 and 0.609), along with high rates of false positives and false negatives (>40%). These shortcomings suggest that the model struggles to distinguish foliar structures similar to those of the crop and to handle illumination variability or overlapping vegetation.

From an agronomic perspective, the magnitude of the observed false negatives compromises the operational reliability of the model for precision weeding applications. In such systems, the priority is not only to avoid erroneous detections, but to ensure exhaustive identification of weeds, even at the cost of increasing false positives. In this sense, the global F1-score below 0.70 indicates that YOLOv9s still does not meet the performance threshold required for direct deployment in field conditions.

3.1.2. Performance of the RT-DETR-l Baseline Configuration

The RT-DETR-l model exhibited an overall intermediate performance, characterized by high sensitivity but limited precision, resulting in less balanced behaviour than that observed for YOLOv9s (Table 4). The model achieved a global F1-score of 0.648 and an mAP@0.5 of 0.716, indicating adequate spatial detection capability, albeit with notable errors in final classification. On average, it achieved Precision = 0.549 and Recall = 0.798, indicating a clear tendency toward overprediction, at the expense of accuracy.

Table 4.

Performance metrics of the RT-DETR-l model for crop and weed detection.

The high global recall (0.798) demonstrates that the model can identify most crop and weed instances in the image, reducing the risk of omission (FN = 45.14%, higher than that observed with YOLOv9s). However, this gain in sensitivity comes at the cost of a high false-positive rate (FP = 20.20%), reducing the practical reliability of the system. In automated control scenarios, this behaviour may lead to unnecessary herbicide applications or mechanical weeding errors, affecting both operational efficiency and agronomic precision.

At the class level, the most consistent detections were obtained for Beet (F1 = 0.717), Weed4 (0.662), and Weed6 (0.681), all with mAP@0.5 values above 0.69, suggesting that the model robustly recognizes larger objects or those with regular morphology. However, species Weed2, Weed3, and Weed5, which exhibit more variable leaf structures or partial occlusions, showed a decline in precision (0.45–0.52) combined with high recall (>0.80), indicating a tendency to over-detect when classifying ambiguously. This pattern is characteristic of Transformer-based architectures, which prioritize global attention at the expense of fine details, especially when spectral differences between crop and weeds are minimal.

From an agronomic standpoint, although RT-DETR-l reduces the false negative rate and improves detection coverage, its F1-score below 0.65 limits its direct applicability in the field. The model shows promising potential for assisted or combined detection systems (ensembles), where its high sensitivity could complement more precise models such as YOLOv9s. However, its current performance highlights the need to optimize confidence thresholds and spatial attention mechanisms to better balance sensitivity and precision, ensuring exhaustive detection without compromising system reliability.

3.1.3. Comparison Between YOLOv9s and RT-DETR-l

Table 5 summarizes the overall behaviour of both models, revealing clear differences in their balance between precision and sensitivity. YOLOv9s exhibited more stable and controlled performance, with the highest F1-score (0.686) and a better trade-off between precision and recall, whereas RT-DETR-l, despite achieving higher recall, substantially reduced precision, resulting in more incorrect detections. This contrast reflects two opposing tendencies: YOLOv9s is conservative and tends to miss some weeds, whereas RT-DETR-l is more sensitive but less reliable in its final classification.

Table 5.

Comparative performance metrics of the YOLOv9s and RT-DETR-l models.

From an agronomic standpoint, both scenarios are problematic: omissions (false negatives) reduce weed control effectiveness, and erroneous detections undermine the operational precision of weeding. Therefore, the results confirm that neither of the two architectures achieves an adequate balance between sensitivity and specificity, which justifies the need for new training runs, parameter tuning, and the evaluation of more advanced architectures aimed at improving sensitivity without sacrificing precision in weed detection in red beet.

In interpretive terms, the comparison reveals different operating behaviours. YOLOv9s maintains a more controlled trade-off between precision and sensitivity, whereas RT-DETR-l achieves higher sensitivity at the cost of a marked reduction in precision, leading to increased spurious detections and limiting practical reliability. This is relevant for weed management because an automated system must maximise coverage to avoid leaving weeds untreated, while keeping false activations low to prevent unnecessary interventions. Consequently, these findings support proceeding to an optimisation stage focused on reducing omissions without compromising robust overall performance.

3.2. Results Phase 2: Extended Architecture Evaluation (YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, YOLOv10s, YOLO11s YOLO12s + RT-DETR-l, 640 × 640)

3.2.1. Performance of the YOLOv8s Baseline Configuration

The YOLOv8s model showed limited overall performance, with a global F1-score of 0.651 and an mAP@0.5 of 0.666, indicating moderate detection capability and poorer generalization compared with later YOLO versions. Although the average precision (0.673) and recall (0.636) remained balanced, the model exhibited a marked tendency to omit true instances (FN = 32.7%), a critical issue in weed detection, since each omission represents an uncontrolled plant and therefore a potential loss of efficiency in weeding or localized herbicide application. The per-class analysis revealed a wide variability in performance (Table 6), with outstanding results for Beet (F1 = 0.714) and Weed3 (F1 = 0.715), whereas Weed2 (F1 = 0.614) and Weed5 (F1 = 0.585) showed the greatest limitations, with error rates above 40%, associated with morphological similarity to the crop and illumination variations during image acquisition.

Table 6.

Comparative performance metrics of YOLO models (v8s, v9s, v10s, 11s, 12s) and RT-DETR-l.

From an agronomic perspective, recall levels below 0.65 in most classes indicate that the model does not achieve sufficient detection coverage for direct field implementation. In practice, this behaviour would imply that a significant number of weeds remain undetected, reducing the effectiveness of intelligent spraying systems or precision weeding. Although the achieved precision is moderate, the operational cost of false negatives far outweighs the benefit of avoiding false detections.

3.2.2. Performance of the YOLOv10s Baseline Configuration

The YOLOv10s model achieved a global F1-score of 0.676 and an mAP@0.5 of 0.665, slightly better than YOLOv8s but still limited for reliable field deployment. Although the model maintained a high average precision of 0.749, its recall of 0.617 indicates insufficient sensitivity (Table 6), with a marked tendency to miss true detections (FN = 25.1%). This gap between precision and sensitivity suggests that, while the model is often correct when it produces a detection, it still fails to identify a substantial number of weeds, compromising the effective coverage of the system.

At the class level, the most consistent detections corresponded to Beet (F1 = 0.722), Weed3 (F1 = 0.725), and Weed6 (F1 = 0.714), with moderate error rates (FP < 35% and FN < 25%), indicating stable recognition in species with greater morphological and chromatic contrast. In contrast, Weed5 (F1 = 0.604) and Weed1 (F1 = 0.633) yielded the poorest results, with false-positive rates above 44%, revealing high confusion with the background and crop foliage. From an agronomic standpoint, recall levels below 0.65 confirm that the model does not achieve sufficiently comprehensive detection for effective weed control in the field. This limitation implies that a relevant fraction of weeds could go unnoticed, reducing the effectiveness of weeding or localized herbicide application. In crops such as beet, where early competition is critical, model sensitivity is more decisive than precision to guarantee operational applicability.

3.2.3. Performance of the YOLO11s Baseline

The YOLO11s model achieved an average F1-score of 0.674 and an mAP@0.5 of 0.691, showing stable performance and more homogeneous behaviour across classes compared with its predecessors. The mean precision (0.687) and recall (0.665) indicate a slight improvement in detection consistency (Table 6). However, the model still exhibits a false-negative rate of 31.3%, indicating that a significant number of true instances are still missed. Nevertheless, the reduction in false positives (33.5%) relative to earlier versions suggests progress in the model’s ability to discriminate background vegetation, providing greater control over spurious detections.

Individually, the crop Beet (F1 = 0.730) and the weeds Weed3 (F1 = 0.714) and Weed6 (F1 = 0.754) showed the strongest results, with a good balance between precision and sensitivity, reflecting robust performance across chromatic and morphological variability. In contrast, Weed1 (F1 = 0.585) and Weed5 (F1 = 0.630) remained the most challenging classes, due to confusion with the background and their lower representation in the training set. From an agronomic viewpoint, the model exhibits intermediate operational capability, sufficient for experimental applications or decision-support systems, but still limited for the exhaustive detection required in selective weed control, where the omission of individuals can compromise the effectiveness of intervention. However, the improvement observed in inter-class stability suggests that YOLO11s provides a more mature baseline for subsequent optimizations aimed at field implementation.

3.2.4. Performance of the YOLO12s Baseline Configuration

The YOLO12s model achieved an average F1-score of 0.671 and an mAP@0.5 of 0.690, demonstrating stable, predictable behaviour across classes (Table 6), though without a substantial performance leap over YOLO11s. The global precision of 0.685 and recall of 0.663 reflect a balanced relationship between correct detections and sensitivity, with a slight improvement in the management of false positives (FP = 33.7%) compared with previous models. This balance points to a more refined architecture that maintains consistency without degrading performance for minority classes. However, the false negative rate (31.5%) still limits its direct use in field scenarios. Per-class performance was relatively uniform, with Beet (F1 = 0.710), Weed3 (F1 = 0.732), and Weed6 (F1 = 0.717) standing out for their stability and low error levels, suggesting good discrimination in species with well-defined leaf structures. Conversely, Weed5 (F1 = 0.571) remained the most problematic category, with more than 50% false positives associated with confusion with the background and less distinctive visual patterns. From an agronomic perspective, the model offers relative reliability for assisted applications but still lacks the sensitivity required for exhaustive detection in precision weeding systems. While the achieved precision indicates a more mature and efficient architecture, the magnitude of false negatives suggests that YOLO12s requires additional modifications to achieve better performance.

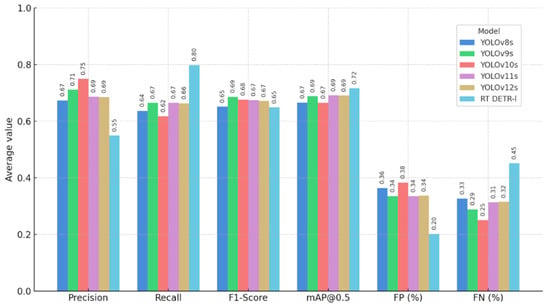

3.2.5. Global Benchmarking and Selection of Architectures for Scaling Based on F1 and FN

The comparative analysis reveals a progressive evolution in the performance of the YOLO models across versions (Table 6). From a technical and agronomic standpoint, the comparative analysis of the models shows that YOLOv9s and YOLOv10s were the architectures with the best overall performance (Figure 5), combining the highest F1-scores (0.686 and 0.676, respectively) with the lowest false negative rates (28.9% and 25.1%). This result is particularly relevant in the agricultural context, where FNs correspond to undetected weeds that persist in the field, maintaining direct competition with the crop and reducing the effectiveness of control measures.

Figure 5.

Comparative performance of YOLO and RT-DETR-l models.

Although none of the models achieves perfect detection, both provide an adequate balance between precision and sensitivity, ensuring effective coverage without generating excessive false detections. In particular, YOLOv9s stands out for its inter-class stability and consistency in identifying both the crop and the weeds, whereas YOLOv10s exhibits more conservative behaviour but with an acceptable error margin for precision weeding applications. Consequently, a third phase was initiated, consisting of training the higher-capacity variants (s, m, l, and x) of the selected architectures (YOLOv9 and YOLOv10) to analyse whether the increase in structural complexity, number of parameters, and network depth translates into improved performance and stability in weed detection. In addition, the effect of input resolution (1024 × 1024 and 2048 × 2048 pixels) on system precision and sensitivity was evaluated to determine the most robust and agronomically viable configuration for implementation in computer vision systems for precision weeding.

Based on the homogeneous 640 × 640 px benchmark, the results indicate that architectural differences alone do not necessarily translate into fewer omissions, as several models exhibit comparable overall performance and similar sensitivity constraints under identical training conditions. Consequently, candidate selection for scaling was driven by the stability of the precision–sensitivity trade-off, since missed weeds impose a higher operational cost than overdetections in selective control. Therefore, Phase 2 served to narrow the search space and advance only those model families most likely to benefit from increased capacity and higher input resolution in the subsequent phase.

3.3. Results Phase 3: Model Scaling and Input Resolution (YOLOv9–YOLOv10, 1024 and 2048)

The results obtained in this phase provide an accurate view of model behaviour under different scaling levels, enabling the identification of the most efficient and robust configurations for their application in computer vision systems for precision weeding in red beet cultivation (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparative results of the scaled YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 variants at different resolutions.

The scaling of the YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 models revealed a general trend of improved stability and consistency in detections as both network capacity and input resolution increased. Overall, the models trained on 2048 × 2048 pixel images systematically outperformed their 1024 × 1024 counterparts, with F1-score gains of up to 7% and marked reductions in false-negative rates. This behaviour confirms that higher spatial density contributes to better delineation of fine structures such as leaf margins, overlaps, and partial occlusions—elements that are critical for discriminating between crop and weeds under real field conditions.

Within the YOLOv9 family, the YOLOv9e-2048 variant emerged as the best configuration, achieving an F1-score of 0.738, an FN rate of 28.34%, and the highest mAP@0.5 of the entire phase (0.779). This model exhibited a solid balance between precision and sensitivity, showing consistent detection performance even for species with morphological or colour features similar to the crop. By contrast, the smaller versions (YOLOv9s and YOLOv9m) delivered acceptable performance but with a slight loss of sensitivity (FN > 28.5%), suggesting that increasing the number of parameters and network depth enhances generalization capacity without compromising operational efficiency.

3.4. Comparative Summary Across Phases

The three-phase approach allowed us to move from an initial comparison between detector families (CNN vs. Transformer) to an informed selection of architectures and, finally, to the optimization of capacity and resolution to reduce false negatives (FN), which is the most critical failure mode in weed control. The strength of the approach lies in the fact that each phase restricts the search space and converts performance findings (F1, FN%, and mAP@0.5) into explicit experimental decisions about which models to scale and at what resolution to evaluate.

In Phase 1 (baseline, 640 × 640), under homogeneous conditions, YOLOv9s showed moderate and relatively balanced overall performance (F1 = 0.686; FN = 28.9%), while RT-DETR-l showed high sensitivity but low precision (Recall = 0.798; Precision = 0.549), with a lower F1 (0.648) despite a higher mAP@ 0.5 (0.716), confirming that mAP alone does not reflect the operational cost of errors when the system tends to overpredict or when the final classification is unstable. Therefore, this phase contributes to the use of F1 and FN% as primary criteria for selecting the most efficient architecture and most aligned with the agronomic objective of minimizing undetected weeds.

In Phase 2 (extended benchmark, 640 × 640), the homogeneous comparison between YOLO versions revealed systematic differences under the same training configuration: YOLOv8s was the most limited (F1 = 0.651; FN = 32.7%), YOLOv9s maintained the best balance (F1 = 0.686; FN = 28.9%), and YOLOv10s stood out for its high precision (0.749) and lowest FN at 640 (25.1%), although with moderate recall (0.617; F1 = 0.676). YOLO11s/YOLO12s showed stability in mAP (0.690–0.691) but no clear improvements in FN (31%), limiting their operational advantage. Overall, this phase consolidated a reproducible ranking and justified limiting scaling to YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 due to their better overall profile and lower omission rate.

In Phase 3 (scaling + 1024/2048 resolution), the increase in resolution and, to a lesser extent, model capacity consistently improved performance and reduced omissions, demonstrating that greater spatial detail favors detection under overlaps and occlusions. In YOLOv9, going from 1024 to 2048 increased F1 (e.g., 0.689 → 0.734 in YOLOv9s) and reduced FN (32.5% → 28.2%), with an increase in mAP@0.5 (0.727 → 0.774), with YOLOv9e-2048 standing out as the most robust configuration (F1 = 0.738; FN = 28.34%; mAP@0.5 = 0.779). In YOLOv10, the 2048 variants achieved the best F1 scores in the study, with YOLOv10m-2048 as the best compromise (F1 = 0.744; FN = 27.48%; mAP@0.5 = 0.775), while larger variants showed marginal gains or changes in the trade-off. Methodologically, the phase confirms that resolution is a dominant factor and that scaling must be justified by net improvements in F1/FN, not just mAP.

Overall, Phase 1 provided a diagnosis of the trade-off between families (control vs. overprediction) and established decision metrics; Phase 2 provided a homogeneous benchmark for selecting candidates with the best operational profile; and Phase 3 quantified the impact of resolution and scaling, identifying priority configurations (YOLOv9e-2048 and YOLOv10m-2048) for further validation. This progression reduces experimental redundancy because each stage fulfills a different function (baseline → screening → optimization) and transforms results into design decisions, improving methodological traceability and the reproducibility of the architecture selection process for multi-class weed detection in red beets.

Moreover, phase 3 indicates that input resolution is a dominant factor in crop–weed scenes with overlap and partial occlusion, as it preserves fine details such as leaf edges, textures, and small structures, which improves separability between visually similar classes. Consequently, configurations with 2048 × 2048 px tend to stabilize performance and reduce omissions compared to 1024 × 1024 px, consolidating the finalist models as more consistent alternatives for a greenhouse environment. This reinforces that scaling should be justified by net improvements in operational metrics, not just slight increases in mAP.

3.5. Class Evaluation and Performance Analysis of the Finalist Models

3.5.1. Analysis of YOLOv9e at 2048-Pixel Resolution

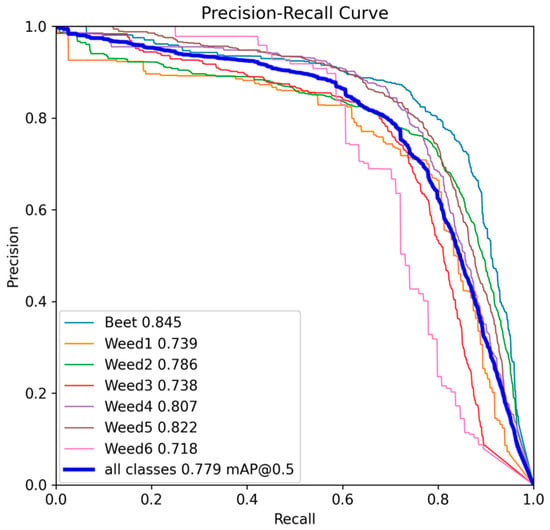

As noted above, the YOLOv9e model at 2048 pixels exhibited a consistent balance between precision and sensitivity, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 0.779 and a global F1-score of approximately 0.738.

The PR curves (Figure 6) show smooth trajectories without early collapses, indicating stable behaviour across different thresholds. The area under the curve (AP) confirms the following order of per-class performance: Beet (0.845), followed by Weed5 (0.822), then Weed4 (0.807), Weed2 (0.786), Weed3 (0.738), Weed1 (0.739), and finally Weed6 (0.718). In practical terms, Beet, Weed5, and Weed4 maintain high precision even at elevated recall values; Weed2 retains solid behaviour but loses precision when recall exceeds approximately 0.8; and Weed1, Weed3, and Weed6 exhibit an earlier drop in precision, indicating greater sensitivity to occlusions, background texture, and inter-species similarity.

Figure 6.

Precision–Recall curve for YOLOv9e at 2048 px resolution.

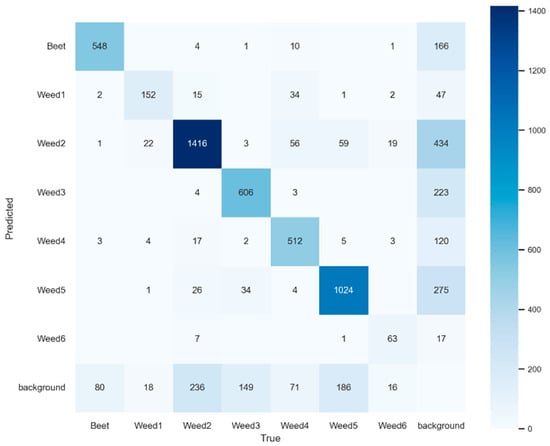

Taken together, the model keeps errors under control in the dominant classes. Beet shows FP of 13.56% and FN of 24.93% (Table 8), consistent with 166 Beet predictions drifting to background and 80 true Beet instances missed to background (Figure 7), yielding an F1 of 0.804. Weed5 and Weed2 display an operationally solid profile: Weed5 with FP of 19.75% and FN of 24.93% (F1 = 0.776); Weed2 with FP of 17.91% and FN of 29.55% (F1 = 0.758). In both cases, the main error source is FN falling into the background (Weed5: 186; Weed2: 236), consistent with omissions driven by occlusion, object size, or NMS effects rather than by inter-species confusion.

Table 8.

Main performance metrics of YOLOv9e at 2048 px resolution.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix for YOLOv9e at 2048 px resolution.

In the intermediate block, Weed4 and Weed3 maintain F1 values of 0.755 and 0.743, with FP rates of 25.80% and 23.77%, and FN rates of 23.12% and 27.51%, respectively. The matrix (Figure 7) shows that Weed4 does suffer from cross-confusion (FN distributed toward Weed2: 56 and Weed1: 34, in addition to 71 to background), whereas Weed3 is mainly lost to background (223) with very little drift to other classes. This suggests prioritising techniques for recovering partially occluded objects rather than hardening inter-class decision boundaries.

The critical classes are Weed1 and Weed6. Weed1 combines an FN of 39.92%, an FP of 22.84%, and an F1 of 0.676; the matrix shows that almost half of its FN drifts to Weed2 (15) and Weed4 (34), in addition to 18 to background, highlighting the impact of morphological similarity. Weed6 exhibits an FP of 39.42% and an FN of 28.41%, with an F1 of 0.656; its errors concentrate on confusion with Weed2 (7) and losses to background (17), which increases with the low sample size.

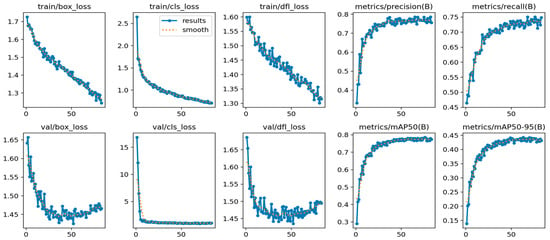

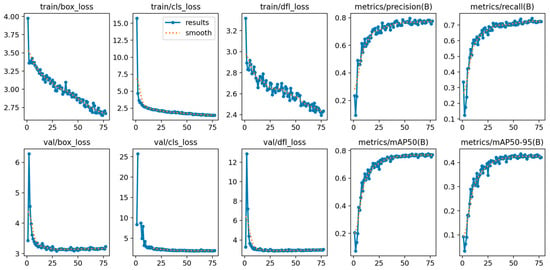

Regarding training, YOLOv9e-2048 (Figure 8), the learning dynamics show a continuous reduction in training losses, with regular decreases in train/box_loss, train/cls_loss, and train/dfl_loss, confirming a progressive adjustment of both box regression and class discrimination. In validation, val/cls_loss stabilizes early after the initial drop, indicating that the separation between categories is consolidated in a few epochs. In contrast, val/box_loss and val/dfl_loss decline rapidly and then stabilize with a slight final increase, a typical pattern when the improvement in localization becomes marginal and an incipient loss of generalization appears in the geometric adjustment, without this translating into relevant operational degradation.

Figure 8.

Training and validation curves for the YOLOv9e at 2048 px resolution.

In terms of metrics, the model reaches a consistent regime with precision (0.78) and recall (0.74–0.75), accompanied by mAP@0.5 = 0.78 and mAP@0.5:0.95 = 0.44, with clear stabilization after the first few dozen epochs. This behavior suggests that the final performance is dominated by an early stage of efficient learning and that, subsequently, training enters a zone of fine refinement with limited gains.

3.5.2. Analysis of YOLOv10m at 2048-Pixel Resolution

Within the YOLOv10 family, the YOLOv10m variant at 2048-pixel resolution maintained a well-balanced global performance, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 0.775 and an average F1-score of 0.744, placing it among the best-performing models in the entire series. This result reflects an appropriate relationship between precision (0.725) and sensitivity (0.766), with a noticeable reduction in false negatives compared with lower-resolution models. The overall stability of the model confirms that the increase in capacity and spatial detail favoured the detection of fine structures and the separation of morphologically similar classes.

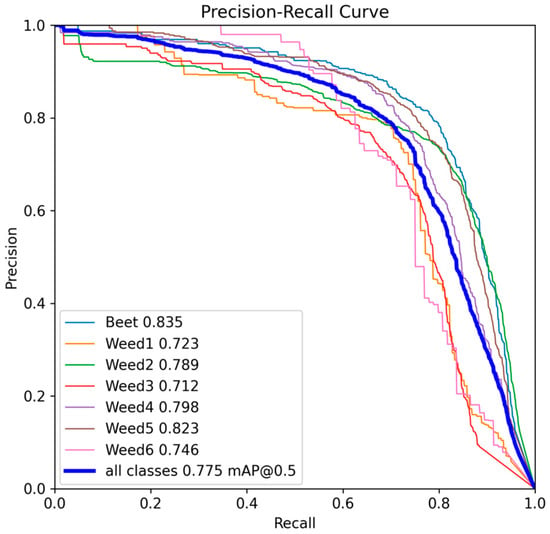

The PR curves (Figure 9) show stable behaviour without abrupt drops, indicating a coherent model response to changes in confidence thresholds. The area under the curve (AP) reveals the following order of per-class performance: Beet (0.835), Weed5 (0.823), Weed4 (0.798), Weed2 (0.789), Weed6 (0.746), Weed1 (0.723), and Weed3 (0.712). In practical terms, Beet, Weed5, and Weed4 maintain high precision even at elevated recall levels, suggesting good morphological discrimination; Weed2 preserves stable performance, although it is more sensitive at high thresholds, whereas Weed1, Weed3, and Weed6 exhibit earlier drops in precision, associated with visual similarity and low occurrence frequency.

Figure 9.

Precision–Recall curve for YOLOv10m at 2048 px resolution.

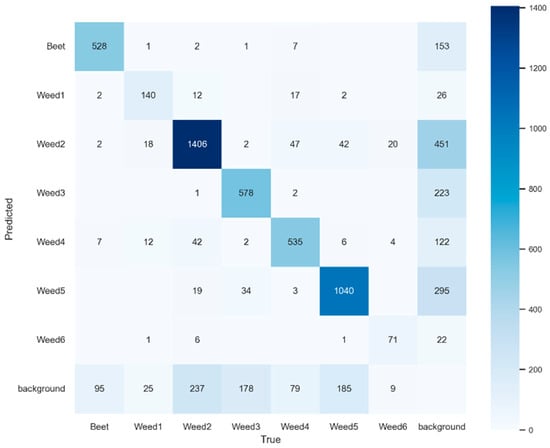

According to the confusion matrix (Figure 10), the dominant classes showed low error rates. The Beet class reached an F1-score of 0.796, with 16.72% FP and 23.70% FN (Table 9), values consistent with 153 incorrect predictions to background and 95 true instances not detected. Among the weed classes, Weed5 (F1 = 0.780), Weed2 (F1 = 0.757), and Weed4 (F1 = 0.754) exhibited stable operational performance, with FN ranging from 25% to 29% and FP below 23%. Most errors corresponded to omissions to background, with 295, 451, and 122 instances, respectively. Occasional inter-class confusion was also observed, mainly between Weed2 and Weed5 and between Weed2 and Weed4, attributable to chromatic and morphological similarities at early phenological stages. These patterns suggest the need to refine non-maximum suppression mechanisms and spatial separation between classes to reduce losses due to overlap.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix for YOLOv10m at 2048 px resolution.

Table 9.

Main performance metrics of YOLOv10m at 2048 px resolution.

The intermediate classes, Weed3 (F1 = 0.723) and Weed1 (F1 = 0.707), maintained acceptable performance, with false negatives around 29% and false positives in the 27–29% range. In both cases, most omissions corresponded to detections classified as background (223 and 26 cases, respectively), indicating limitations in segmenting partially occluded structures. Weed6 (F1 = 0.693) remains the least stable class, with 31.7% false positives and 29.70% false negatives, which is associated with its low representation in the training set and its morphological similarity to other narrow-leaved species.

With regard to the training process, YOLOv10m-2048 (Figure 11), the curves show a stable training process with good generalization. First, training losses (train/box_loss, train/cls_loss, and train/dfl_loss) decrease steadily throughout the epochs, without abrupt oscillations, indicating a progressive improvement in both localization and classification. In validation, the losses (val/box_loss, val/cls_loss, val/dfl_loss) show a sharp drop in the first ~10–15 epochs and then enter a plateau with small variations, without increasing separation from the training losses; this pattern is consistent with the absence of significant overfitting and suggests early convergence.

Figure 11.

Training and validation curves for the YOLOv10m at 2048 px resolution.

At the same time, performance metrics increase rapidly at the beginning and then stabilize: Precision increases to values close to 0.78–0.79, Recall converges around 0.72–0.73, and mAP@0.5 reaches a plateau close to 0.78, while mAP@0.5:0.95 stabilizes around 0.43. Most of the gain occurs in the first ~20–30 epochs, and subsequent improvements are marginal, supporting that the model reaches a stable and reproducible performance regime.

Overall, class-level results indicate that remaining errors are mainly due to omissions that end up being assigned to the background and confusion between morphologically similar weeds, especially in low-frequency classes. Precision–Recall (PR) curves show stable behavior for dominant classes, while minority classes show earlier degradation of precision, consistent with occlusions and limited representation. These patterns suggest that robustness is limited less by overall learning dynamics and more by the detection of small or overlapping objects and class imbalance at the inference stage.

From an agronomic perspective, false negatives are the most critical factor, as they imply undetected weeds that are not treated during weeding or selective spraying. In this context, both YOLOv9e-2048 and YOLOv10m-2048 stand out for combining high sensitivity and precision with moderate error levels, ensuring sufficient detection coverage to maintain crop competitiveness against weed interference. Although neither model achieves perfect performance, both provide a stable response aligned with the operational requirements of precision agriculture, making them the most suitable candidates for subsequent field validation stages.

4. Conclusions

This study confirms the preliminary feasibility, under controlled conditions, of deep learning–based detection models for automated weed identification in red beet, under a phased protocol and with selection criteria centred on F1-score and false negatives (FN) as key metrics. The initial comparison of architectures, followed by capacity scaling and increased input resolution, enabled a rigorous characterization of the trade-off between precision, sensitivity, and inter-class stability in a controlled experimental setting.

In the baseline evaluation, YOLOv9s showed the best initial balance (global F1 of 0.686). In contrast, RT-DETR-l, despite its high recall, yielded a lower F1 score (<0.648) and a high FN rate, limiting its operational usefulness. With architectural scaling and increased resolution to 2048 × 2048 pixels, the best results were obtained with YOLOv9e-2048 (global F1 of 0.738; mAP@0.5 of 0.779) and YOLOv10m-2048 (global F1 of 0.744; mAP@0.5 of 0.775). These models maintained FN rates around 27–29% without a proportional increase in FP, and showed smooth Precision–Recall curves—altogether indicators of threshold robustness and good inter-class generalization.

From a weed management standpoint, FNs represent the system’s critical cost: each omission results in an untreated weed that continues to compete for water, light, and nutrients during the most sensitive crop stages. In this sense, YOLOv9e-2048 and YOLOv10m-2048 offer the best balance between sensitivity and overtreatment, emerging as potential candidates for integration into selective weeding/spraying systems, with sufficiently high F1 scores and acceptable FP/FN ratios for real-time operation. The per-class hierarchy derived from PR curves and AP supports this conclusion: the crop (Beet) and dominant weeds (e.g., Weed2, Weed4, Weed5) are consistently detected, while minority classes (Weed1, Weed6) require closer attention.

The findings of this study allow the selected models to be integrated into a selective weed control system in controlled environments, given that increasing the input resolution and scale of the models consistently reduces FN, which is critical because each FN implies an untreated weed. In practice, the detected crop and weed boxes are transformed into coordinates on the container plane through camera-plane calibration and translated into action commands according to the control mechanism. In selective spraying, each weed detection activates a nozzle and defines an application pulse; additionally, multi-class detection distinguishes weed types, allowing the application strategy to be adjusted by pulse intensity/time or dose variation. In mechanical weeding, crop detections delimit exclusion zones, and weed detections define weeding zones where the tool acts without affecting the crop.

Future Directions

Future work should prioritise field validation of the selected models across different phenological stages and soil management conditions. In open-field scenarios, lighting variability, soil background heterogeneity, wind-induced motion, and broader phenological diversity shift distributions relative to greenhouse imagery. Therefore, expanding the dataset with field images covering multiple growth stages and operational conditions for both crop and weeds is essential to improve class balance, reduce bias in underrepresented classes, and obtain a realistic assessment of performance under deployment conditions. In addition, model operation should be refined by evaluating confidence-threshold calibration and the suppression of overlapping detections under agronomic cost-sensitive criteria, aiming to reduce omissions while keeping unnecessary interventions under control. Finally, to enable embedded deployment in automated weed management platforms, future studies should quantify real-time constraints and assess lightweight optimisation strategies, such as model compression or efficient model combinations, while preserving the precision–sensitivity trade-off achieved in this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L.G.-N., A.B.B. and L.M.N.-G.; methodology, O.L.G.-N., A.B.B. and L.M.N.-G.; software, O.L.G.-N. and A.B.B.; validation, O.L.G.-N. and A.B.B.; formal analysis, O.L.G.-N., A.B.B. and L.M.N.-G.; investigation, O.L.G.-N., A.B.B. and L.M.N.-G.; resources, L.M.N.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.L.G.-N. and L.M.N.-G.; writing—review and editing, O.L.G.-N., A.B.B. and L.M.N.-G.; supervision, A.B.B. and L.M.N.-G.; project administration, L.M.N.-G.; funding acquisition, L.M.N.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the European Union through CIRAWA Project (Agroecological Strategies for resilient farming in West Africa, HEEU-101084398) and DIGIS3 Project (DIGITAL-2021-EDIH-01) funded by the European Union.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available because they are part of ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

Oscar Leonardo García-Navarrete was financed under the call for University of Valladolid 2021 predoctoral contracts, co-financed by Banco Santander. The authors would like to thank Castilla y León Supercomputing Centre (SCAYLE—https://www.scayle.es; accessed on 28 November 2025) and the Research Group TADRUS of the Department of Agricultural and Forestry Engineering, University of Valladolid. The authors used ChatGPT version 5.0 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) and Grammarly to assist in improving the English language and readability of this manuscript. These tools were used solely for language editing; no AI tools were used to generate, analyze, or interpret the scientific content. The authors reviewed and verified all content and took full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdo, E.; El-Sohaimy, S.; Shaltout, O.; Abdalla, A.; Zeitoun, A. Nutritional Evaluation of Beetroots (Beta Vulgaris L.) and Its Potential Application in a Functional Beverage. Plants 2020, 9, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilà, M.; Williamson, M.; Lonsdale, M. Competition Experiments on Alien Weeds with Crops: Lessons for Measuring Plant Invasion Impact? Biol. Invasions 2004, 6, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.S. Principles of Weed Management in Agroecosystems and Wildlands. Weed Technol. 2004, 18, 1559–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subeesh, A.; Bhole, S.; Singh, K.; Chandel, N.S.; Rajwade, Y.A.; Rao, K.V.R.; Kumar, S.P.; Jat, D. Deep Convolutional Neural Network Models for Weed Detection in Polyhouse Grown Bell Peppers. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2022, 6, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Badri, A.H.; Ismail, N.A.; Al-Dulaimi, K.; Salman, G.A.; Khan, A.R.; Al-Sabaawi, A.; Salam, M.S.H. Classification of Weed Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review-Challenges, Current and Future Potential Techniques. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudul Hasan, A.S.M.; Sohel, F.; Diepeveen, D.; Laga, H.; Jones, M.G.K. Weed Recognition Using Deep Learning Techniques on Class-Imbalanced Imagery. Crop. Pasture Sci. 2022, 74, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.S.M.M.; Sohel, F.; Diepeveen, D.; Laga, H.; Jones, M.G.K. A Survey of Deep Learning Techniques for Weed Detection from Images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoglou-Grammatikis, P.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Lagkas, T.; Moscholios, I. A Compilation of UAV Applications for Precision Agriculture. Comput. Netw. 2020, 172, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Young, S. Performance Evaluation of Deep Transfer Learning on Multi-Class Identification of Common Weed Species in Cotton Production Systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.; Konovalov, D.A.; Philippa, B.; Ridd, P.; Wood, J.C.; Johns, J.; Banks, W.; Girgenti, B.; Kenny, O.; Whinney, J.; et al. DeepWeeds: A Multiclass Weed Species Image Dataset for Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H.K.; IJsselmuiden, J.; Hofstee, J.W.; van Henten, E.J. Transfer Learning for the Classification of Sugar Beet and Volunteer Potato under Field Conditions. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 174, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, L.; Xing, J.; Shi, L.; Gao, Z.; Yuan, Q. Research Status of Mechanical Intra-Row Weed Control in Row Crops. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2017, 33, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- García-Navarrete, O.L.; Correa-Guimaraes, A.; Navas-Gracia, L.M. Application of Convolutional Neural Networks in Weed Detection and Identification: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tianhua, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Shi, Y.; Abdelhamid, M.A. A Comprehensive Review of Applications of Robotics and Artificial Intelligence in Agricultural Operations. Stud. Inform. Control. 2023, 32, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, G. Attention-Aided Lightweight Networks Friendly to Smart Weeding Robot Hardware Resources for Crops and Weeds Semantic Segmentation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1320448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmalek, Z.; Raineault, N.A. Remote Science at Sea with Remotely Operated Vehicles. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1454923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Qiao, Y.; Kong, H.; Sukkarieh, S. Real Time Detection of Inter-Row Ryegrass in Wheat Farms Using Deep Learning. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 204, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, M.; Huang, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, H. A Deep Learning Approach Incorporating YOLO v5 and Attention Mechanisms for Field Real-Time Detection of the Invasive Weed Solanum Rostratum Dunal Seedlings. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumuga Arun, R.; Umamaheswari, S.; Mohamed Meerasha, I.; Mohankumar, B. Enhancing the Weed Segmentation in Diverse Crop Fields Using Computationally Effective Concatenated Attention U-Net with Convolutional Block Attention Module. Sci. Rep. 2025. Scientific Reports. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Omid, M.; Taheri-Garavand, A.; Jafari, A. Deep Learning-Based Precision Agriculture through Weed Recognition in Sugar Beet Fields. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 35, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, S.I.; Khan, U.S.; Qureshi, W.S.; Tiwana, I.M.; Rashid, N.; Alasmary, W.S.; Iqbal, J.; Hamza, A. A Patch-Image Based Classification Approach for Detection of Weeds in Sugar Beet Crop. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 121698–121715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; French, A.P.; Pound, M.P.; He, Y.; Pridmore, T.P.; Pieters, J.G. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Image-Based Convolvulus Sepium Detection in Sugar Beet Fields. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunil, G.C.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Howatt, K.; Peters, T.; Ostlie, M.; Aderholdt, W.; Sun, X. Field-Based Multispecies Weed and Crop Detection Using Ground Robots and Advanced YOLO Models: A Data and Model-Centric Approach. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jeon, W.-S.; Cielniak, G.; Rhee, S.-Y. ATT-NestedUnet: Sugar Beet and Weed Detection Using Semantic Segmentation. Int. J. Fuzzy Log. Intell. Syst. 2024, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, M. Real-time Semantic Segmentation Network for Crops and Weeds Based on Multi-branch Structure. IET Comput. Vis. 2024, 18, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaeth, M.; Sökefeld, M.; Schwaderer, P.; Gauer, M.E.; Sturm, D.J.; Delatrée, C.C.; Gerhards, R. Smart Sprayer a Technology for Site-Specific Herbicide Application. Crop. Prot. 2024, 177, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortatas, F.N.; Ozkaya, U.; Sahin, M.E.; Ulutas, H. Sugar Beet Farming Goes High-Tech: A Method for Automated Weed Detection Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Precision Agriculture. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 4603–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, R.; Bezhin, K.; Santel, H.-J. Sugar Beet Yield Loss Predicted by Relative Weed Cover, Weed Biomass and Weed Density. Plant Prot. Sci. 2017, 53, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jursík, M.; Holec, J.; Soukup, J.; Venclová, V. Competitive Relationships between Sugar Beet and Weeds in Dependence on Time of Weed Control. Plant Soil Environ. 2008, 54, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Goodacre, R. On Splitting Training and Validation Set: A Comparative Study of Cross-Validation, Bootstrap and Systematic Sampling for Estimating the Generalization Performance of Supervised Learning. J. Anal. Test. 2018, 2, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A Systematic Analysis of Performance Measures for Classification Tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, 45, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Goadrich, M. The Relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC Curves. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning—ICML ’06; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall Plot Is More Informative than the ROC Plot When Evaluating Binary Classifiers on Imbalanced Datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Navarrete, O.L.; Camacho-Tamayo, J.H.; Bregon, A.B.; Martín-García, J.; Navas-Gracia, L.M. Performance Analysis of Real-Time Detection Transformer and You Only Look Once Models for Weed Detection in Maize Cultivation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; NanoCode012; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; TaoXie; Fang, J.; imyhxy; et al. Ultralytics/Yolov5: V7.0—YOLOv5 SOTA Realtime Instance Segmentation; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.