Abstract

The effects of soil organic carbon fractions and tea enzyme activities on the antioxidant quality of tea leaves were determined. The experiment set up single biogas slurry application and co-application of biochar and biogas slurry (50%, 100%, 150%, 200% slurry substitution for nitrogen fertilizer, 350 °C pig manure biochar at 1% and 2% application rates and 500 °C rice straw biochar at 1% and 2% application rates). The results showed that, compared with the control (CK), the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry had a synergistic effect, with the most significant effect observed when 350 °C pig manure was combined with biogas slurry at a ratio of 2%. This treatment resulted in peak levels of readily oxidizable organic carbon (ROC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the soil, significantly increasing by 8.43 g/kg and 0.23 mg/kg, respectively, compared to the CK, and significantly enhancing the activity of key carbon cycle enzymes such as β-glucosidase (S-β-GC). These improvements in soil biochemical properties directly translated into improved tea quality: the tea leaves treated under this treatment had the highest content of tea polyphenols and amino acids, and the ABTS and DPPH free radical scavenging rates increased by 3.25% and 5.97%, respectively, compared to the CK, while the malondialdehyde (MDA) content was the lowest. Mantel test and multivariate regression analysis further confirmed that particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) were the main carbon components driving the accumulation of tea polyphenols, while catalase (CAT) and other enzymes were key co-regulatory enzymes. The optimal application ratio of biochar and biogas slurry not only improved tea leaf quality but also resulted in increased SOC content within the study period, providing preliminary evidence for promoting SOC accumulation in the short term.

1. Introduction

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is the largest pool of terrestrial carbon (C) globally, containing approximately 1550 Pg C in the top meter of soil, about 3-fold more than in vegetation biomass carbon, and has significant longer residence time than vegetation biomass carbon [1]. SOC plays a vital role in providing ecosystem services such as global C storage, soil functions (e.g., microbial activity, nutrient cycling, and water storage), soil fertility, and agricultural productivity [2,3]. However, SOC deficiencies in most areas, rapid soil decomposition in some environments, low overall nutrient content, and deterioration of soil structure caused by the overuse of synthetic fertilizers pose significant challenges to sustainable agriculture [4]. To address the practical challenge of reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers while enhancing both tea quality and soil health in intensively managed plantations, this study specifically investigated the synergistic potential of biogas slurry combined with contrasting biochar types.

Against this backdrop, biochar and biogas slurry have garnered significant attention as two highly promising soil amendments. Biochar is the carbon-rich product of the thermal degradation of biomass by pyrolysis under oxygen-limited conditions and relatively low temperatures (≤700 °C) [5,6]. Previous studies have shown that biochar can enhance soil organic matter content, improve soil physical and chemical properties, increase crop yield, and decrease soil greenhouse gas emissions. Incorporating biochar into cropland soil has been confirmed as an efficient way to mediate SOC sequestration and sustain crop productivity [7,8]. Biogas slurry, a byproduct of the anaerobic fermentation of crop straw, animal manure, and human excrement, can enhance nitrogen (N) uptake [9,10], soil microbial biomass (SMB) [11], and crop production. When applied individually, both have significant limitations: biochar itself has low nutrient content, resulting in limited short-term soil fertility effects [12]; nutrients in biogas slurry are prone to leaching, and long-term sole application may pose environmental risks [13]. Moreover, in tea plantation systems, especially in the context of organic input substitution, relevant evidence remains insufficient. Therefore, researching the optimal application ratio of biochar and biogas slurry is crucial not only for overcoming their respective limitations but also for achieving the dual goals of soil carbon accumulation and crop quality improvement in both theory and practice.

China is the largest tea-producing country in the world, and Zhejiang Province ranks second among the major tea-producing provinces in the country, with a total annual tea production of about 202,000 tons [14], which gives it a unique advantage in the tea trade. With the expansion of tea cultivation area and the increasing duration of tea planting, the excessive and uncontrolled application of large quantities of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and the over-exploitation of tea gardens have led to serious degradation of tea plantation soils, manifesting as acidification, compaction, and declining fertility, etc. [15]. The quality of the soil affects the quality of the tea leaves. The quality of tea is predominantly influenced by its core secondary metabolites, namely tea polyphenols (TPP), total amino acids (TAA), alkaloids, and aroma constituents. Specifically, the oxidation products of TPP contribute to the infusion color, while the diverse array of aroma compounds influences aroma quality [16]. TPP and TAA are important components of tea taste and major quality indicators that contribute about 70% of the umami taste intensity [17]. The antioxidant activity of tea has been extensively studied, and the main methods for evaluating the antioxidant activity of tea include 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrydrazyl radical (DPPH) and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), etc. [18]. Research indicates that biochar application directly enhances tea quality indices, improves soil pH, carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, and enzyme activity [19]. It also indirectly influences tea growth and quality by enhancing soil enzyme activity in tea gardens, thereby affecting the root environment [20]. Therefore, restoring soil quality should prioritize enhancing fertility and structural properties.

To mechanistically decipher how biochar and biogas slurry co-application influences soil carbon dynamics and tea quality, this study focuses on key SOC fractions and carbon-cycle-related enzymes. SOC is a complex mixture of compounds with very different turnover times. Researchers often partition SOC into labile versus stable pools to capture carbon dynamics. For example, “reactive organic carbon” includes DOC, ROC, and POC [21]. These are fast-turnover, easily decomposed fractions that strongly influence short-term soil C cycling and nutrient availability. In contrast, MAOC represents the more recalcitrant pool (often 50–70% of SOC) bound to soil minerals [22], reflecting long-term carbon storage. By measuring DOC, ROC, POC, and MAOC, we can distinguish how amendments affect both rapid carbon turnover and stable C sequestration in soil. Similarly, microbial enzymes offer functional insight into soil carbon processing. We focus on β-glucosidase (β-GC), sucrase (S-SC), catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD) because these enzymes catalyze key steps in C cycling. β-GC and S-SC break down polysaccharides (cellulose, sucrase) into simple sugars, driving organic matter decomposition [23], while CAT and POD degrade reactive peroxides and complex phenolics produced during decay [24]. In fact, these enzymes have been explicitly linked to the C cycle: Wang et al. noted [25] that “β-GC, S-SC, CAT and POD are associated with the C cycle”. In short, measuring β-GC, sucrase, CAT, and POD activities provides indicators of microbial carbon turnover [23]. Together with the SOC fractions, these enzyme assays help explain how biochar and biogas slurry alter soil C transformations and, by extension, tea plant nutrition and antioxidant quality.

Most of the current studies have focused on the effects of biogas slurry, biochar alone, or in combination with chemical fertilizers on the organic carbon composition of agricultural soils or on the antioxidant quality of tea; research on the combination of biochar and biogas slurry is still limited, especially for tea plants. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of biogas slurry application and the combined application of different types of biochar with biogas slurry at two temperatures on soil carbon components, and analyzed their impact on the antioxidant properties and quality of tea leaves. This study aims to: (1) determine the responses of different soil carbon components to these organic amendments and identify which component exerts the most significant influence on soil carbon-related enzymatic activity; and (2) elucidate how amendment-induced changes in soil carbon components affect the accumulation of antioxidant compounds in tea leaves through the regulation of soil microbial processes and carbon-cycle enzyme activities. Clarifying this mechanism will provide a scientific basis for selecting targeted amendments to enhance soil organic carbon pools and improve tea quality in tea plantations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

The experiment was conducted at Haishun Family Farm in Kaihua County, Quzhou, China (118°26′ E, 29°09′ N), the annual average temperature was 16.6 °C, with an annual average precipitation of 1830.8 mm. The tested tea plant variety was “Chunyu No.1”, which was 23 years old. The tested soil was a typical southern red soil with the following basic physicochemical properties: SOC 20.11 g/kg, pH 4.67, total phosphorus 0.54 g/kg, total nitrogen 0.85 g/kg, total potassium 3.51 g/kg.

The tested biogas slurry was obtained by a fermentation project at a farm in Zhejiang Province. The basic physicochemical properties of the biogas slurry were as follows: pH 8.08 ± 0.37, total nitrogen content 0.09 ± 0.02%, phosphorus (P2O5) content 0.011 ± 0.02%, and potassium (K2O) content 0.06 ± 0.01%. The biochar used in the experiment was prepared through anaerobic pyrolysis of pig manure and rice straw at 350 °C and 500 °C, respectively. Its basic properties are shown (Table 1).

Table 1.

Testing the basic physical and chemical properties of biochar.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment comprised nine treatment groups, each replicated three times. Each treatment plot measured 15 square meters (3 m × 5 m), with a fertilizer application rate of 448 kg ha−1 (N:P2O5:K2O = 15:5:26). After prioritizing the determination of the total nitrogen applied via biogas slurry, the remaining nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers were supplemented accordingly. The biogas slurry application rates without biochar amendment were set as follows: CK (pure chemical fertilizer), nitrogen content of biogas slurry 50% and nitrogen content of nitrogen fertilizer 50% (N1), nitrogen content of biogas slurry 100% (100% slurry substitution for nitrogen fertilizer) (N2), nitrogen content of biogas slurry 150%, without nitrogen fertilizers (N3), and nitrogen content of biogas slurry 200%, without nitrogen fertilizers (N4). For treatments N1 to content of biogas slurry 200%, withoutN4, the application rates of phosphorus (P2O5) and potassium (K2O) fertilizers were kept the same as those in the control (CK). The annual application rates of slurry, excluding CK, were 84.3 t ha−1, 149.3 t ha−1, 232.1 t ha−1, and 298.5 t ha−1, respectively. The biogas slurry was applied in five separate applications. For the biochar-amended treatments, all treatment areas apply an average of 149.3 t ha−1 of biogas slurry annually, in combination with either 1% pig manure biochar (N2Z1), 2% pig manure biochar (N2Z2), 1% rice straw biochar (N2S1), and 2% rice straw biochar (N2S2). N, Z, and S represent biogas slurry, pig manure charcoal, and rice straw charcoal, respectively. The biochar application rates were 0%, 1%, and 2% (by mass). 2.25 million kilograms of topsoil per hectare, with a plowing depth of 20 cm; The application rate of 1% carbon is 2.25 kg/m2. The tea trees in the experimental area were pruned uniformly in July each year. Irrigation with biogas slurry was carried out by water pipes, and weeding was done by manual weeding without the use of any herbicides.

2.3. Sample Collection

This experiment commenced in July 2021 with the application of biochar to the test site. Tea leaves and soil samples were collected in the fourth year following biochar application. Soil samples were collected from 0–20 cm of the soil layer using a soil auger with the five-point method in each experimental plot, and the soil samples were homogeneously mixed, and impurities such as sand and dead leaves were removed. The soil samples were then divided into two portions. One portion was subjected to natural air-drying and sieved after mortar-and-pestle grinding, with the objective of determining the soil organic carbon fractions and enzyme activities. The remaining portion was stored in a refrigerator set at −20 °C, with the objective of determining the soil microbial carbon and conducting additional measurements. Tea leaf samples were collected in accordance with national tea standards. Within each experimental plot, leaves at the same developmental stage were picked from multiple randomly selected tea plants, avoiding sampling immediately after rainfall to ensure stable leaf condition. The sampling method was one bud with three leaves. Three independent biological replicates were obtained for each treatment, with each replicate collected and processed separately.

2.4. Measurement Items and Methods

SOC was determined by external heating with potassium dichromate; Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) and Mineral-Associated Organic Carbon (MAOC) were separated from soil particle size by sodium hexametaphosphate leaching [26] and determined by a fully automated elemental analyzer (Vario Macro Cube elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany)); Readily Oxidizable Carbon (ROC) was determined by oxidation with potassium permanganate 333 mmol·L−1 [27]; The Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) was extracted from soil samples with deionized water at a water-to-soil ratio of 5:1 [28], and analyzed using a total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu TOC-VCPH analyzer (Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a TNM-1 device). β-S-GC (β-glucosidase), S-SC (Soil Sucrase), S-CAT (Soil Catalase), S-POD (Soil Peroxidase), CAT (Catalase), and POD (Peroxidase) activities were determined according to the enzyme activity kit provided by Su Zhou. The tea infusion was prepared according to GB/T 8305-2013 [29], weigh 2 g (accurate to 0.001 g) of the ground sample, add 300 mL of boiling distilled water, and immediately transfer to a boiling water bath for extraction for 45 min (shaking once every 10 min). Immediately after extraction, filter to obtain the tea infusion. Determination of DPPH radical scavenging activity and ABTS radical scavenging activity, TPP were determined using the forintol colorimetric method, free TAA were determined using the ninhydrin colorimetric method, and malondialdehyde was determined using the thiobarbituric acid colorimetric method.

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

Data were summarized, analyzed, and processed using Excel 2021 and analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS 27.0, with significant differences being labelled at p < 0.05 level. Correlation analyses of soil organic carbon fractions, soil enzyme activities, and antioxidant properties of tea were carried out by Pearson’s method and plotted using Origin 2024; the letter marking is the Duncan method.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Organic Carbon Fractions Changes with Biogas Slurry and Biochar Application

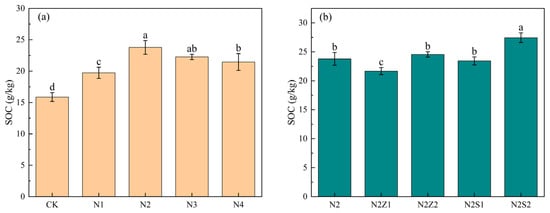

3.1.1. Content of Soil Organic Carbon

Soil organic carbon content under different fertilization regimes is shown (Figure 1). Compared with CK, treatments involving the application of either biogas slurry or combination of biochar and biogas slurry significantly increased SOC content. The most pronounced increase in SOC was observed in the N2S2 treatment, which showed a 61.8% increase relative to the CK treatment. The application of biogas slurry alone resulted in a unimodal response of SOC content to increasing nitrogen input, with the highest value observed under the N2 treatment (23.8 g/kg), which was 49.9% higher than that of the control (CK). Under the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry, SOC content was higher under the 2% biochar application than under the 1% rate. In contrast, no significant differences were detected among the N2, N2Z2, and N2S1 treatments.

Figure 1.

Effect of biogas slurry (a) and combined application (b) on soil organic carbon. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

Note: CK (pure chemical fertilizer), biogas slurry was applied to all plots at an annual rate of 5.65 t mu−1 (N1); 10.00 t mu−1 (N2); 15.55 t mu−1 (N3); and 20.00 t mu−1 (N4). For the biochar-amended treatments, all treatment areas apply an average of 10.00 t mu−1 of biogas slurry annually, in combination with either 1% pig manure biochar (N2Z1), 2% pig manure biochar (N2Z2), 1% rice straw biochar (N2S1), and 2% rice straw biochar (N2S2). Same as below.

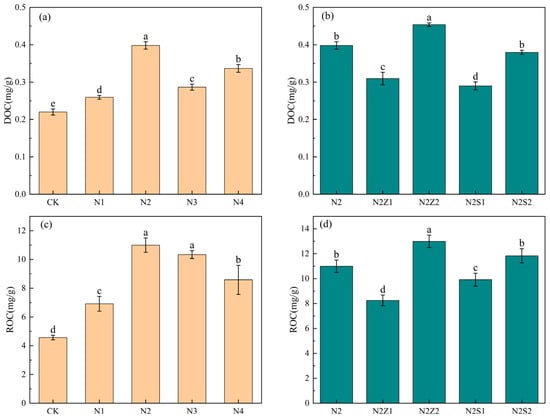

3.1.2. Content of Soil Active Organic Carbon Components

DOC and ROC are two important components of Soil Organic Carbon fractions. Compared with CK, both biogas slurry application and the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry significantly increased soil DOC and ROC contents, with the highest values observed under the N2Z2 treatment, which were 101.4% and 114.2% higher than those in CK, respectively (Figure 2). Under sole biogas slurry application, the contents of DOC and ROC exhibited a unimodal response to increasing nitrogen input, peaking at the N2 treatment. In the combined application, DOC and ROC contents were higher under the 2% biochar application than under the 1% rate; however, compared with N2, the addition of 1% biochar even reduced DOC and ROC contents.

Figure 2.

Effect of biogas slurry (a,c) and combined application (b,d) on soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and readily oxidizable carbon (ROC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

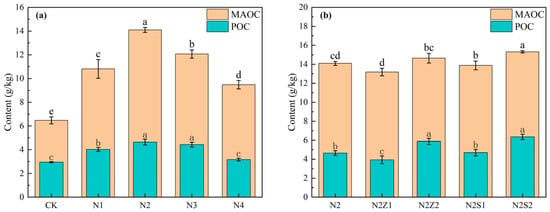

3.1.3. Content of Particle Size of Organic Carbon

As shown (Figure 3), both biogas slurry application and the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry significantly increased POC and MAOC content. Compared with CK, the application of biogas slurry alone and its combination with biochar significantly increased soil POC and MAOC contents, with the highest values observed under the N2Z2 treatment. Under biogas slurry application alone, POC and MAOC contents first increased and then decreased with increasing application rate, peaking at the N2 treatment at levels 57.9% and 117.6% higher than those in CK, respectively. In the combined application, POC and MAOC contents were higher at the 2% biochar rate than at the 1% rate. Compared with N2 alone, the addition of 2% biochar further increased the POC content, whereas MAOC content showed no significant difference.

Figure 3.

The effect of biogas slurry (a) and combined application (b) on soil Particulate organic carbon (POC) and Mineral-Associated Organic Carbon (MAOC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

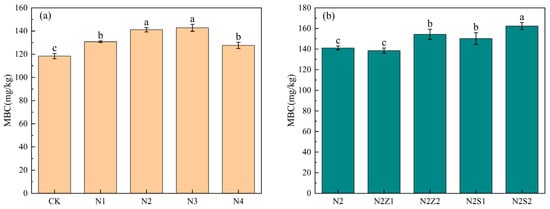

3.1.4. Content of Soil Microbial Carbon

As shown (Figure 4), both biogas slurry application and the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry significantly increased soil MBC content. The highest value was observed under the N2S2 treatment, which was 37.1% higher than that in CK. Under biogas slurry application alone, MBC content initially increased with application rate before decreasing. It peaked in the N3 treatment group, reaching 24.42 g/kg higher than the control group. Under biogas slurry application alone, MBC contents first increased and then decreased with increasing application rate, peaking at N3 treatment at levels 20.6% higher than those in CK. In the combined application, MBC content was higher at the 2% biochar rate than at the 1% rate, with respective increases of 17.0%, 30.4%, 26.9%, and 37.1% compared to CK. Compared with N2 alone, the addition of 2% biochar consistently enhanced MBC content, whereas no significant difference was observed between N2 and N2Z1.

Figure 4.

The effect of biogas slurry (a) and combined application (b) on soil Microbiological Carbon (MBC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

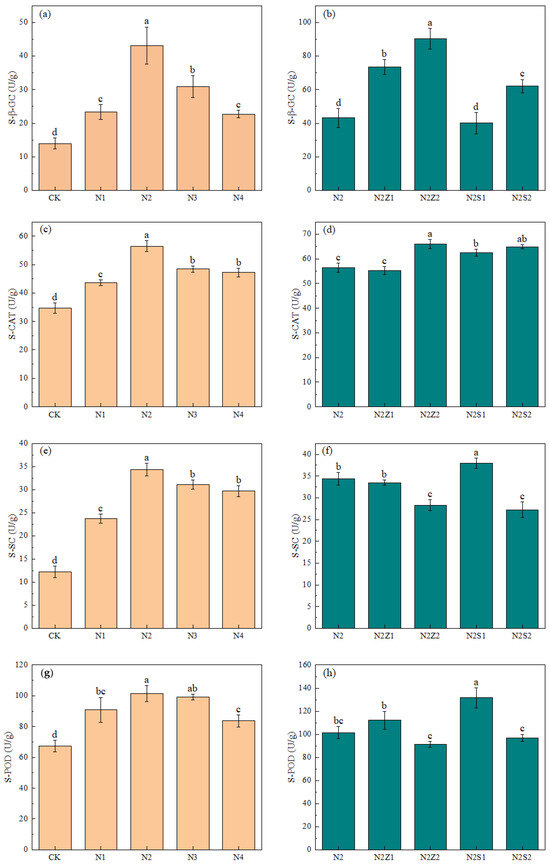

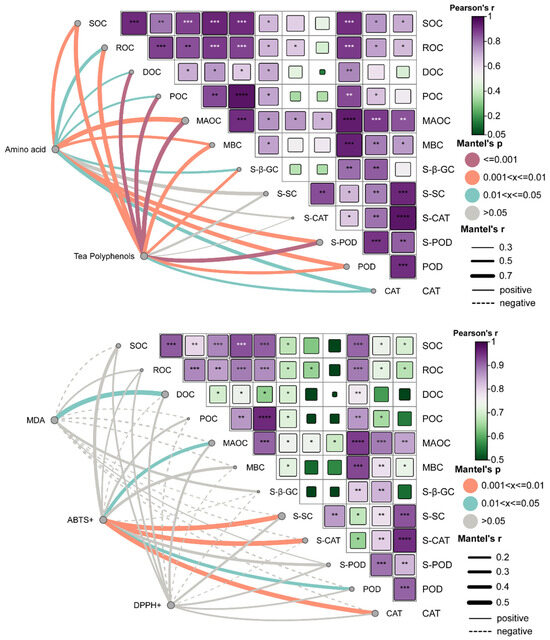

3.2. Soil Carbon-Related Enzyme Activities Change with Biogas Slurry and Biochar Application

The most pronounced increases were observed for S-β-GC and S-POD under the N2Z2 treatment, which were 363.5% and 90.7% higher than those in CK, respectively. Conversely, the activities of S-SC and S-CAT reached their maxima under the N2S1 treatment, showing increases of 211.9% and 131.7% compared to CK. Compared with CK, the activities of S-β-GC, S-SC, S-CAT, and S-POD were significantly increased in both biogas slurry application alone and its combination with biochar treatments (Figure 5). The most significant increases were observed for S-β-GC and S-POD activities under the N2Z2 treatment, which were 363.5% and 90.7% higher than those in CK, respectively. Conversely, the most significant increases were observed for S-SC and S-CAT activities under N2S1 treatment, which were 211.9% and 131.7% higher than those in CK, respectively. S-β-GC and S-POD activities were higher at 2% biochar application than at 1% biochar application under combined application, while the opposite was true for S-SC and S-CAT. Under biogas slurry application alone, the activities of soil carbon-related enzymes were all increased and then decreased with increasing application rate, and they were all highest under N2 treatment.

Figure 5.

The effect of biogas slurry (a,c,e,g) and combined application (b,d,f,h) on the activity of soil carbon-related enzymes. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

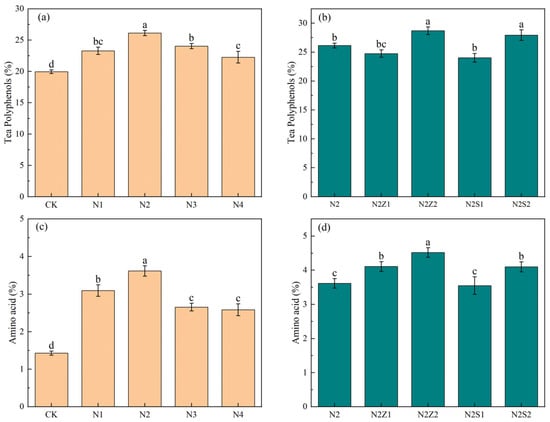

3.3. Tea Quality and Antioxidant Properties

3.3.1. Tea Leaf Quality

Compared with CK, both the biogas slurry application alone and the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry markedly increased the contents of TPP and TAA (Figure 6). Among the combined applications, the 2% biochar addition was superior to the 1% rate. The most significant enhancement was observed for tea polyphenol and amino acid contents under the N2Z2 treatment, which were 69.2% and 191.2% higher than those in CK, respectively. Under biogas slurry application alone, the contents of tea polyphenol and amino acid exhibited a unimodal trend with increasing application rate, peaking at N2 treatment.

Figure 6.

The effect of biogas slurry (a,c) and combined application (b,d) on Tea leaf quality. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

3.3.2. Antioxidant Properties of Tea Leaves

Although at a tea infusion concentration of 0.2 mg/mL (Figure 7), biogas slurry and combined application enhance removal activity. Specifically, the 1% biochar rate enhanced ABTS scavenging more than the 2% rate, with the N2S1 treatment exhibiting the highest effect (16.5%). The DPPH radical scavenging activity among the composite treatment groups showed little variation, with no significant differences observed between the N2 and N2Z2 treatment groups. In the combined application, the N2S1 and N2S2 treatments showed the highest malondialdehyde levels, whereas the N2Z2 treatment recorded the lowest content, representing a 42.1% reduction compared to the control group. ABTS radical scavenging activity showed no significant change under biogas slurry application alone. DPPH radical scavenging activity reached the maximum at N3 (76%), which was 122.6% higher than CK and even superior to the combined treatments. And the N2 and N4 treatments exhibited the highest malondialdehyde content, with no significant differences observed between the remaining treatments and the control group.

Figure 7.

The effect of biogas slurry (a,c,e) and combined application (b,d,f) on Antioxidant properties of tea leaves. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments at the 5% level, p < 0.05.

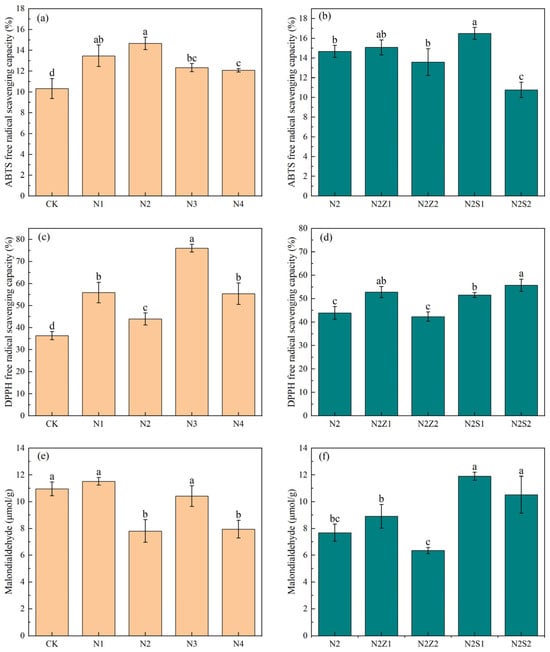

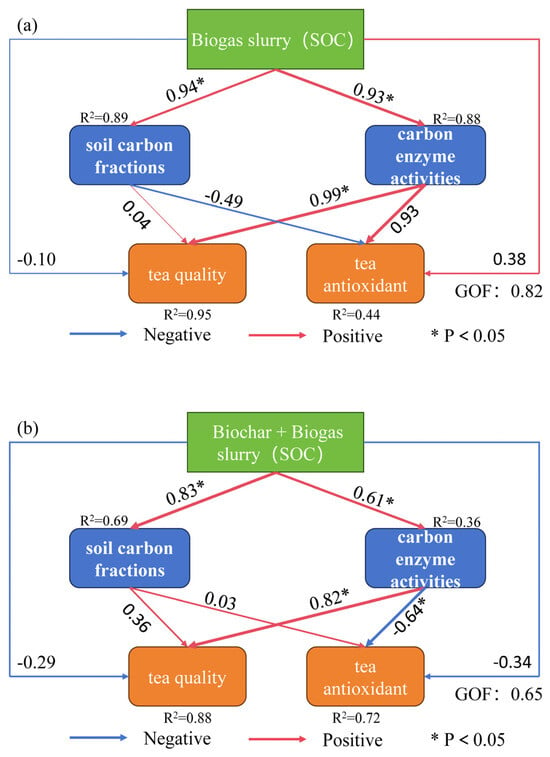

3.4. Correlation Among SOC Fractions, Enzyme Activities, and Tea Quality

In the tea quality analysis (upper panel), TPP showed highly significant positive correlations (p < 0.001) with major soil carbon fractions, such as DOC (r > 0.5), POC, and MAOC, as well as with carbon-related enzyme activities, such as POD and S-β-GC (p < 0.05) (Figure 8). These results suggest that soil carbon pools and carbon transformation capacity play key roles in regulating the accumulation of secondary metabolites of tea trees. In the antioxidant network (lower panel), the dashed edges of MDA pointed to carbon factors such as SOC and MAOC, reflecting the negative correlation between MDA and carbon storage. The ABTS scavenging activity formed strong network connections with indicators such as MAOC, S-SC, S-CAT, and POD, and the pathways were mostly positively correlated, indicating that mineral-bound organic carbon and antioxidant enzyme systems synergistically promote free radical scavenging. The positive correlation between ABTS radical scavenging activity and indicators such as MAOC, SC, S-CAT, and POD indicated that mineral-bound organic carbon and anti-oxidant enzyme system had a synergistic effect on free radical scavenging. Multiple linear regression analysis (Table 2) revealed that POD exhibited the highest standardized regression coefficient in the regression model linking TPP and TAA accumulation, indicating its significant positive regulatory effect on these compounds’ accumulation in tea leaves. These findings suggest that readily available carbon sources synergistically promote amino acid metabolism with the antioxidant system. Among antioxidant indicators, MDA exhibited significant negative correlations with ROC and S-SC, indicating that carbon and certain enzyme activities effectively reduce membrane lipid peroxidation levels. POD emerged as the primary regulator of ABTS and DPPH. Conversely, ROC showed negative correlations with DPPH, suggesting it may suppress tea quality and antioxidant properties under oxidative stress conditions. The structural equation modeling (Figure 9) showed that both biogas slurry and biochar-biogas slurry mixtures significantly increased soil carbon content and soil enzyme activity. SOC, as a core indicator of soil fertility, serves as a direct material source for antioxidant capacity through components such as phenolic compounds and aromatic carbon. Biochar and biogas slurry combined revealed a small positive impact on soil carbon content on tea quality; however, carbon cycling enzyme activity was closely related to tea biochemical traits and was an important mediating factor between soil properties and tea quality. When biogas slurry is applied alone, SOC can directly affect the antioxidant capacity of tea, while combined application may improve the antioxidant capacity of tea by affecting the organic carbon composition. Table 2 and Figure 9 use VIF values and SOC as measurement criteria, respectively, thereby enabling better observation of differences under specific conditions.

Figure 8.

Linkages Between Soil Organic Carbon Fractions, Carbon-Cycling Enzymes, and Tea Quality: Insights From Pearson and Mantel Correlation Networks. Note: Edge width corresponds to the Mantel r value for the respective distance correlation, while edge color indicates the significance level. Purple lines denote Mantel p ≤ 0.001, orange lines indicate 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01, blue lines represent 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, and gray lines signify no significance. In all panels, asterisks denote significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression results for TPP, TAA, MDA, ABTS, and DPPH (standardized coefficients).

Figure 9.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) diagrams showing the effects of biogas slurry (a) and biochar–biogas slurry (b) application on soil carbon fractions, carbon-cycle enzyme activities, tea quality, and tea antioxidant capacity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Biogas Slurry and Combined Biochar and Biogas Slurry Application on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions

SOC content is commonly used to characterize soil fertility and quality [30]. Therefore, increasing soil organic carbon content is an important condition for improving the soil and increasing crop yield. In this experimental study, it was found that the organic carbon content under 2% biochar application rate treatment was higher than under 1% application rate treatment. Biochar itself, as a highly stable carbon source, can directly increase the total soil carbon pool upon application [31]. More importantly, biochar addition rates often correlate positively with soil total organic carbon (TOC) and its active fractions, such as POC [32]. For instance, a cultivation experiment using 13C-labeled biochar demonstrated that at addition gradients ranging from 0.5% to 1%, higher doses (1%) more effectively increased both SOC and POC content [33]. The higher SOC accumulation observed in the 2% biochar treatment in this study likely stems from both the direct increase in exogenous stable carbon input and the enhanced physicochemical protection of the soil’s original organic carbon by the biochar. In this experimental study, biogas slurry application enhanced the SOC content, probably because the biogas slurry increased the soil water content, improved the soil microbial growth environment, and promoted the decomposition of plant residues [34] and thus also increased the SOC content. The results of this study are consistent with previous research. Cao et al. [35] found a significant increase in organic matter and easily oxidizable carbon in the soil with biogas slurry application. Depending on the formation pathway, persistence, and function, SOC can be categorized into two parts: POC (particle size > 53 micrometres) and MAOC (particle size < 53 micrometres). They jointly determine its storage capacity, turnover dynamics, and ecological functions [36,37]. POC has a faster turnover rate than MAOC, is more unstable, and belongs to the active organic carbon pool, while MAOC belongs to the inert organic carbon pool [38]. We found that both single application of biogas slurry and combined biochar and biogas slurry application can promote the accumulation of POC and MAOC, and the combination effect is more excellent. DOC and ROC are two important components of active organic carbon in soil. DOC is a key energy source for soil microorganisms and promotes the decomposition of SOC. In contrast, ROC is a more unstable form of organic carbon that can significantly alter stable SOC in soil. ROC is highly sensitive to environmental changes and can reflect the activity and temporal dynamics of SOC [39,40]. This study found that adding 1% biochar resulted in lower DOC and ROC content in the biogas slurry compared to applying biogas slurry alone. This is because low-dose biochar stimulates microbial activity, accelerates activated carbon metabolism [41], and effectively binds easily soluble and migratable organic carbon components in the biogas slurry through physical adsorption and chemical bonding [42]. Microorganisms are important participants in regulating the soil carbon biochemical cycle, and while decomposing soil organic carbon, they also assimilate and synthesize their own MBC, which is one of the most important indicators of soil microbial activity and soil nutrient status [43,44,45]. In the presence of biochar, biochar itself can increase soil carbon composition (DOC, MBC, POC, and ROC) [46]. The experimental results revealed that the effects of biochar and biogas slurry combinations on soil carbon composition were more obvious, and the probable reasons are as follows: (1) The combined application of biochar and biogas slurry may produce synergistic effects, which jointly promote the fixation and stabilization of soil carbon [47]. Biochar’s inherently stable aromatic carbon structure enables long-term persistence, increasing soil organic carbon content [48,49]. Meanwhile, biogas slurry is rich in organic matter and nutrients that are easily utilized by microorganisms, which can rapidly enhance soil fertility and promote plant growth. (2) The combined application of biochar and biogas slurry exerts profound impacts on the structure and function of soil microbial communities [50]. The porous structure of Biochar facilitates growth and reproduction by providing a porous habitat refuge [51], and biogas slurry stimulates microbial activity by supplementing abundant organic matter and essential nutrients.

4.2. Effect of Biogas Slurry and Combined Biochar and Biogas Slurry Application on Soil Enzyme Activities

Soil enzymes play very important roles in ecological processes such as soil carbon degradation, mineralization, and nutrient cycling [52]. They can be involved in the biochemical processes that regulate the transformation and cycling of soil organic carbon fractions. As such, soil enzyme activities are recognized as one of the most important indicators for evaluating the soil quality and ecological environment [53].

Soil enzyme activities are governed by a range of factors, including soil physicochemical properties [54], crop type [55], microbial community composition, and anthropogenic activities [56]. Furthermore, they can be influenced by the addition of exogenous substances, such as biochar addition [57,58]. Our results showed that both biogas slurry alone and combined biochar and biogas slurry application increased the activities of S-β-GC, S-SC, S-POD, and S-CAT. The increase in enzyme activities may be due to increased substrate concentration or enhanced microbial utilization and other processes [59]. The organic components of biogas slurry can also act as carbon sources for microorganisms, which stimulate their growth and consequently enhance soil enzyme activities [60]. The alteration of soil physicochemical properties (e.g., texture, structure, moisture, temperature, pH, and SOM) by exogenous substances ultimately affects soil enzyme activity [61,62]. Both biogas slurry and biochar may affect the redox potential of soil, which in turn affects microbial metabolism and enzyme activities [63]. The analysis in this paper showed that the improvement of soil properties such as SOC, ROC, and DOC played dominant roles in increasing soil enzyme activities. This is a finding consistent with previous research [64], which reported a positive correlation between the content of soil organic carbon fractions and the activities of carbon-converting enzymes. Specifically, significant positive correlations were observed between the content of SOC, POC, DOC, and the activity of sucrase.

This study shows that the response of SOC components and carbon cycling enzyme activity to biogas slurry application exhibits a significant unimodal curve. The moderate application treatments (N2; N3) showed the best improvement effect, which is the result of the synergistic effect of soil physicochemical property regulation and microbial processes. First, the alkalinity of biogas slurry is crucial for improving the generally acidified tea garden soil [65]. Increasing soil pH is one of the most critical environmental factors for enhancing the retention efficiency of exogenous organic carbon in soil, as it directly optimizes the microbial habitat and promotes the conversion of carbon into stable pools (such as MAOC) [66]. Second, biogas slurry, as a composite carrier of easily decomposable organic carbon and readily available nutrients, has a strong resource “stimulation effect” on the soil microbial community [67]. This input significantly and universally increases the total biomass of soil microorganisms, especially bacterial biomass. The growth of microbial biomass has been proven to be the core biodynamic driving force for the accumulation of soil organic carbon pools [68], which explains the phenomenon of simultaneous increase in related enzyme activity and SOC in this study. However, there is a balance threshold between the “stimulation effect” and carbon sequestration efficiency. This study observed that the effect of N4 treatment was lower than that of N3 treatment, suggesting that there may be an optimal carbon input level. When there is an excessive input of readily degradable carbon, microbial metabolism may tend to rapidly mineralize rather than biosynthesize, thereby reducing carbon use efficiency [69]. At the same time, high concentrations of ammonium salts and salinity in biogas slurry may cause mild stress when approaching or exceeding the soil buffering capacity, and begin to inhibit some microbial functions [70]. Therefore, appropriate biogas slurry application maximizes the improvement of soil carbon sequestration and ecosystem function by most effectively synergistically regulating soil pH and stimulating “efficient” microbial metabolism.

Compared with the application of biogas slurry alone, the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry can more effectively increase soil organic carbon content, improve soil structure, and promote the growth of soil microorganisms, which in turn can increase the activity of S-β-GC [47]. This result aligns with the findings of Zhang et al. [71], demonstrating that the co-application of biochar and biogas slurry further promotes soil enzyme activities and underscores their synergistic positive effects. The combined application of swine manure-derived biochar and biogas slurry significantly increased soil enzyme activities compared to CK. However, compared to the application of slurry alone (N2), N2S1 significantly enhanced S-SC and S-POD activities, while N2S2 showed no significant effect. On the one hand, the activities of S-SC and S-POD directly depend on the concentration of readily available sucrose substrates and the availability of substrates such as phenols in the soil solution, respectively. We hypothesize that high-dose biochar may over-adsorb these key substrates due to its large specific surface area, reducing their bioavailability [72] and thus limiting the activities of S-SC and S-POD. This inference is consistent with the research logic of Zhang et al. [73], whose study showed that biochar dosage significantly alters the accessibility and transformation pathway of exogenously added sucrose in the soil. S-POD may exhibit similar sensitivity because its substrates or its own proteins are also susceptible to adsorption. In addition, it may be related to the dose-dependent alteration of soil microbial communities by biochar. Studies have shown that the amount of biochar added is a key factor driving changes in soil microbial β-diversity, and when the dosage exceeds 2%, it has an inhibitory effect on specific functional microbial groups (such as Basidiomycetes) [74]. Therefore, it is speculated that the addition of 2% biochar may relatively inhibit the activity of these fungi, thereby limiting the growth of the activity of their dominant secreted S-POD and associated carbon-converting enzymes (such as S-SC). On the other hand, other enzymes involved in more fundamental carbon cycling (such as β-glucosidase and urease) typically have substrates derived from more complex organic polymers, which may not be easily adsorbed by biochar. Therefore, these enzyme activities may benefit more from the overall soil improvement (such as structure, water retention, and pH regulation) brought about by 2% biochar [75]. Biochar and biogas slurry application increased SOC and other nutrient contents, thereby increasing the availability of enzyme substrates. This stimulated soil microorganisms to secrete relevant cellular enzymes to obtain the nutrients necessary for growth, ultimately leading to the formation of more active organic carbon fractions [76].

4.3. Effect of Biogas Slurry and Combined Biochar and Biogas Slurry Application on Antioxidant Quality of Tea Leaves

In this study, the combined biochar and biogas slurry application generally increased the content of secondary metabolites (e.g., TPP and TAA) and enhanced the scavenging capacity of free radicals, such as DPPH and ABTS activities, whereas the MDA content was significantly reduced, suggesting that membrane lipid peroxidation damage was lessened. However, under the application of biogas slurry alone (N2), the optimal scenario may be: excessive replacement increases soil salinity/EC [77], inhibiting microbial activity. While multiple studies indicate that a replacement ratio of around 50% is optimal [77,78], in this study, 100% digested slurry replacement yielded the best performance in indicators such as DPPH and enzyme activity. This discrepancy may stem from the low initial organic matter content of the experimental soil, which required a higher threshold of organic carbon. The 100% replacement provided the most abundant readily degradable organic carbon, maximally stimulating soil microbial metabolic activity and carbon-nitrogen transformation processes. This effect can be attributed to the main mechanisms: The high porosity of biochar adsorbs nutrients from the biogas slurry and releases them gradually, which improves the availability of carbon sources in the rhizosphere and increases the accumulation of reactive carbon fractions, such as DOC and POC [79], and thus promotes the synthesis of secondary metabolites in tea trees. In contrast, the application of biogas slurry alone did not significantly enhance free radical scavenging capacity, despite supplying abundant nitrogen. Although biogas slurry alone supplies abundant nutrients and soluble organic carbon, these carbon inputs are largely labile and rapidly decomposed or leached without the presence of a stable carbon matrix [80]. Therefore, while biogas slurry can temporarily enhance soil nutrient availability, it does not provide the long-term carbon stabilization and nutrient retention effects observed when combined with a stable carbon carrier such as biochar. Studies have shown that biochar addition helps reduce nutrient losses from biogas slurry and improve soil carbon and microbial biomass, indicating that a stable carbon fraction is important for sustained soil amendment effects [81]. Yan et al. [82] reported that biogas slurry without carbonaceous material synergy may even inhibit certain microbial communities when used for a long period of time, which may affect the enzyme activities and activation of plant metabolic pathways. In conclusion, the synergistic formulation of biogas slurry and biochar not only provided nutrients but also improved soil physical chemistry, which was beneficial to tea quality and antioxidant function. The application of biochar and biogas slurry can also influence tea quality by enhancing soil organic carbon. SOC facilitates nitrogen transformation and uptake in soil, providing raw materials for synthesizing TPP and TAA [83]. Soils with high and balanced SOC levels often yield tea infusions with perfectly balanced bitterness and freshness. Furthermore, SOC profoundly influences the composition and function of rhizosphere microorganisms. For instance, as planting duration increases and soil acidification intensifies, fungal communities may gain dominance over bacterial populations. This shift alters nutrient decomposition and cycling pathways within the soil, indirectly regulating the synthesis of theanine (responsible for umami) and aromatic compounds in tea leaves [84].

4.4. Mechanisms of Soil Carbon-Enzyme-Tea Quality Interactions

Figure 9 uses SOC as an indicator to measure organic carbon components (reflecting conversion processes and stability, such as DOC or POC), enzyme activity (investigating effects on β-GC activity, etc.), quality (SOC-associated nutrients in tea leaves and fruits), and antioxidant capacity (e.g., phenols, quinones, aromatic carbons) as direct sources of antioxidant capacity. SOC serves as the fundamental material basis and key driver for all these specific properties. SEM quantitatively identified that SOC and ROC, alongside key enzymes (S-CAT, S-SC), are the primary regulators driving the accumulation of TPP and TAA.

Crucially, this synergy is profoundly dose-dependent. A pivotal finding is that 1% biochar (N2S1) underperformed sole biogas slurry (N2) in elevating certain active carbon pools (e.g., DOC/ROC). This anomaly is not an artefact but a likely manifestation of a low-dose “priming effect” [85]. We hypothesize that low-dose biochar (1%) may stimulate microorganisms to preferentially utilize readily decomposable carbon from the biogas slurry input and may trigger a redistribution of pre-existing soil organic carbon, rather than a net increase, temporarily reducing measurable DOC or ROC pools. In contrast, 2% biochar (N2S2) provides a dominant, stable carbon matrix that effectively adsorbs and physically protects active carbon input, while its stronger amendment effect optimizes soil acidity [73]. This creates a more favorable and stable microenvironment, explaining its superior performance in increasing total organic carbon and the activity of most enzymes. Therefore, the seemingly fragmented results—where 1% biochar excels for specific enzymes (S-SC, S-POD) and 2% biochar for overall SOC—collectively map a transition in microbial response across a dosage threshold. Lower doses may fine-tune specific microbial functions, while higher doses exert broader physicochemical control [74]. Additionally, when soil acidification or nutrient imbalance induces stress, microorganisms and tea plants may upregulate S-POD activity as a response [86]. This process alters carbon flow direction, redirecting resources from quality metabolism toward fundamental defense mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that the combined application of biochar and biogas slurry establishes a synergistic mechanism of “soil carbon-enzyme system driving tea tree secondary metabolism” by synergistically enhancing soil organic carbon composition and activating key carbon conversion enzymes. The combined application primarily promotes the accumulation of soil POC and DOC, providing tea trees with an efficient carbon source; simultaneously, it synergistically activates the activity of key enzymes such as S-CA and S-SC, enhancing soil carbon cycling and nutrient conversion efficiency. This series of improvements in soil biochemical processes ultimately effectively drives the synthesis and accumulation of tea tree secondary metabolites. This is reflected in the following: compared with the control, the content of TPP and TAA significantly increased by 4.06%~8.74% and 2.11%~3.09%, respectively; the antioxidant capacity of tea (ABTS and DPPH free radical scavenging rates) also increased accordingly by 0.43%~6.16% and 5.97%~19.38%. In summary, applying 2% concentration of pig manure biochar treated at 350 °C in combination with 100% nitrogen fertilizer replacement significantly improves tea quality and enhances economic benefits (jointly determined by feedstock and temperature). These data not only quantify the positive effects of combined application but also mechanistically confirm that the synergistic effect of soil carbon composition and enzyme activity is the core pathway to improve tea quality. Therefore, it can provide more accurate data for assessing the long-term effects on tea plants, the responses of different tea varieties, or conducting economic analyses. Furthermore, biochar should be regarded as a long-term agricultural investment due to its stability in soil, and from a social benefits perspective, it can deliver sustained environmental and agronomic benefits.

Author Contributions

S.W.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation. B.F.: Data curation, Validation. K.J.: Investigation. M.M.: Data curation. Z.J.: Conceptualization, Supervision. M.H.W.: Supervision. S.S.: Project administration, Funding acquisition. L.P.: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (2025C02097) for Shengdao Shan, and the Major Projects for Science and Technology Development of Zhejiang Province, China (2019C02061) for Lifeng Ping.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Ping for his meticulous guidance. Throughout the research process, Ping and Jin provided crucial guidance in research design, experimental implementation, and data analysis. Fang and Mi reviewed the data, Jiang collected the samples, Wong checked the manuscript, and Shan provided financial support. I sincerely thank my family for their unwavering support, which enabled me to fully dedicate myself to this academic research. Finally, I thank my friends for their help; your contributions are truly admirable. The findings of this paper build upon the foundational work of many distinguished scholars. I express my heartfelt gratitude to them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Lin, S.; Wang, W.; Sardans, J.; Lan, X.; Fang, Y.; Singh, B.P.; Xu, X.; Wiesmeier, M.; Tariq, A.; Alrefaei, A.F.; et al. Effects of slag and biochar amendments on microorganisms and fractions of soil organic carbon during flooding in a paddy field after two years in southeastern China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 824, 153783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Feng, W.; Luo, Y.; Baldock, J.; Wang, E. Soil organic carbon dynamics jointly controlled by climate, carbon inputs, soil properties and soil carbon fractions. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4430–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Shi, Z. Distinct controls over the temporal dynamics of soil carbon fractions after land use change. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4614–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Liu, D.; Shao, X.; Li, S.; Jin, X.; Qi, J.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Li, C. Effect of Biochar Types and Rates on SOC and Its Active Fractions in Tropical Farmlands of China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, T.; Khan, A.; Ghosh, T.; Kim, J.T.; Rhim, J.W. Advances and prospects for biochar utilization in food processing and packaging applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 39, e00831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.E.; Saldarriaga, J.F.; Tamayo, A. Effect of Biogas Slurry-Modified Biochar on Cd Immobilization, Uptake, Translocation, and the Bioavailability of N, P, and K in Soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 6281–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, Q.; Duan, C.; Huang, G.; Dong, K.; Wang, C. Biochar addition promotes soil organic carbon sequestration dominantly contributed by macro-aggregates in agricultural ecosystems of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Majrashi, M.A. Effect of Different Application Rates and Types of Biochar on Soil Biochemical Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 9743–9756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheets, J.P.; Yang, L.; Ge, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Beyond land application: Emerging technologies for the treatment and reuse of anaerobically digested agricultural and food waste. Waste Manag. 2015, 44, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Li, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Q. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal coupled with carbohydrate production by five microalgae cultures cultivated in biogas slurry. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 221, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubaker, J.; Risberg, K.; Jönsson, E.; Dahlin, A.S.; Cederlund, H.; Pell, M. Short-term effects of biogas digestates and pig slurry application on soil microbial activity. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2015, 2015, 658542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasse, D.P.; Weldon, S.; Joner, E.J.; Joseph, S.; Kammann, C.I.; Liu, X.; O’toole, A.; Pan, G.; Kocatürk-Schumacher, N.P. Enhancing plant N uptake with biochar-based fertilizers: Limitation of sorption and prospects. Plant Soil 2022, 475, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Yasaca, D.V.; Chu, C.Y. Insights into nutrients recovery from food waste liquid Digestate: A critical review and systematic analysis. Waste Manag. 2025, 200, 114743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hong, L.; Jia, X.; Kang, J.; Lin, S.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H. Improvement of soil acidification in tea plantations by long-term use of organic fertilizers and its effect on tea yield and quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1055900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Xue, J.; Wang, M.; Jian, G.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, L. Differences in the quality of black tea (Camellia sinensis var. Yinghong No. 9) in different seasons and the underlying factors. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Pan, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S. Influence of brewing conditions on taste components in Fuding white tea infusions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2826–2833. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Tan, H.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Lao, L.; Wong, C.; Feng, Y. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Liver Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26087–26124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Yao, J.; Ma, C.; Pu, L.; Lei, Z. Biochar, Organic Fertilizer, and Bio-Organic Fertilizer Improve Soil Fertility and Tea Quality. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jin, Z.; Shan, S.; Ping, L. Effects of Biochar Application on Enzyme Activities in Tea Garden Soil. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 728530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Liao, H. Comprehensive Analysis Revealed the Close Relationship between N/P/K Status and Secondary Metabolites in Tea Leaves. Acs Omega 2019, 4, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Jiang, J. The Effects of Different Plant Configuration Modes on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions in the Lakeshore of Hongze Lake. Forests 2025, 16, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Murillo, J.C.; Almendros, G.; Knicker, H. Wetland soil organic matter composition in a Mediterranean semiarid wetland (Las Tablas de Daimiel, Central Spain): Insight into different carbon sequestration pathways. Org. Geochem. 2011, 42, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunoras, J.; Kačergius, A.; Gudiukaitė, R. Role of Soil Microbiota Enzymes in Soil Health and Activity Changes Depending on Climate Change and the Type of Soil Ecosystem. Biology 2024, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemanowicz, J.; Bartkowiak, A.; Zielińska, A.; Jaskulska, I.; Rydlewska, M.; Klunek, K.; Polkowska, M. The Effect of Enzyme Activity on Carbon Sequestration and the Cycle of Available Macro- (P, K, Mg) and Microelements (Zn, Cu) in Phaeozems. Agriculture 2023, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pang, X.; Li, N.; Qi, K.; Huang, J.; Yin, C. Effects of Vegetation Type, Fine and Coarse Roots on Soil Microbial Communities and Enzyme Activities in Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Catena 2020, 194, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambardella, C.A.; Elliott, E.T. Particulate soil organic-matter changes across a grassland cultivation sequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sheng, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Lv, Z.; Qi, W.; Luo, W. Soil labile organic carbon indicating seasonal dynamics of soil organic carbon in northeast peatland. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Willett, V.B. Experimental evaluation of methods to quantify dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 38, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 8305-2013; Tea—Preparation of Ground Sample and Determination of Dry Matter Content. Standard Press of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- He, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, M.; Tong, X.; Sun, F.; Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Zhu, P.; He, X. Long-term combined chemical and manure fertilizations increase soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in aggregate fractions at three typical cropland soils in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 532, 635–644. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Qu, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, D. Soil Respiration and Organic Carbon Response to Biochar and Their Influencing Factors. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, F.; Ma, W.; Wang, Q.; Cao, S.; Geng, Z. Influence of biochar on soil respiration and soil organic carbon fractions. Res. Environ. Sci. 2017, 30, 920–928. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Chang, Y.; Liu, J.; Tian, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, J. Differences in the physical protection mechanisms of soil organic carbon with 13C-labeled straw and biochar. Biochar 2025, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yin, J.; Davy, A.J.; Pan, F.; Han, X.; Huang, S.; Wu, D. Biogas Slurry as an Alternative to Chemical Fertilizer: Changes in Soil Properties and Microbial Communities of Fluvo-Aquic Soil in the North China Plain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Yan, S.; Guo, D.; Wang, G.; Ma, Y. Soil chemical and microbial responses to biogas slurry amendment and its effect on Fusarium wilt suppression. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ren, C.; Wang, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Luo, Y.; Luo, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhu, B.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, S.; et al. Global turnover of soil mineral-associated and particulate organic carbon. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallee, J.M.; Soong, J.L.; Cotrufo, M.F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbi, D.K.; Boparai, A.K.; Brar, K. Decomposition of particulate organic matter is more sensitive to temperature than the mineral associated organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 70, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; He, P.; Wu, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J. Spatial patterns and influencing factors of soil SOC, DOC, ROC at initial stage of vegetation restoration in a karst area. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1099942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhong, C.; Chen, S.; Hu, G. Elevational patterns of soil organic carbon and its fractions in tropical seasonal rainforests in karst peak-cluster depression region. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1424891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Ohoro, C.R.; Ojukwu, V.E.; Oniye, M.; Shaikh, W.A.; Biswas, J.K.; Seth, C.S.; Mohan, G.B.M.; Chandran, S.A.; Rangabhashiyam, S. Biochar for ameliorating soil fertility and microbial diversity: From production to action of the black gold. iScience 2024, 28, 111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiong, X.; He, M.; Xu, Z.; Tsang, D.C.W. Roles of biochar-derived dissolved organic matter in soil amendment and environmental remediation: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Yan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Niklas, K.J.; Huang, H.; Mipam, T.D.; He, X.; Hu, H.; Wright, S.J. Global patterns and predictors of soil microbial biomass carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in terrestrial ecosystems. Catena 2022, 211, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, B.A.; Sarmah, A.K.; Smernik, R.; Hunter, D.W.; Fraser, S. Soil carbon characterization and nutrient ratios across land uses on two contrasting soils: Their relationships to microbial biomass and function. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 97, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Deb, S.; Sahoo, S.S.; Sahoo, U.K. Soil microbial biomass carbon stock and its relation with climatic and other environmental factors in forest ecosystems: A review. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Riaz, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; El-Desouki, Z.; Jiang, C. Biochar–N fertilizer interaction increases N utilization efficiency by modifying soil C/N component under N fertilizer deep placement modes. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Qiu, X.; Ji, H.; Ju, H.; Wang, J. Synergistic effect on soil health from combined application of biogas slurry and biochar. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, Q.; Lou, Y.; Du, Z.; Wang, Q.; Hu, N.; Wang, Y.; Gunina, A.; Song, J. Soil organic and inorganic carbon sequestration by consecutive biochar application: Results from a decade field experiment. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 37, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Lu, Z.; Ma, H.; Jin, S. Effect of biochar on carbon dioxide release, organic carbon accumulation, and aggregation of soil. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2014, 33, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wen, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Mei, X. Biogas slurry strategy reshapes biochar-mediated greenhouse gas emissions via soil bacterial sub-communities. Biochar 2025, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a tool for the improvement of soil and environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.G.; DeForest, J.L.; Marxsen, J.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Stromberger, M.E.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Weintraub, M.N.; Zoppini, A. Soil enzymes in a changing environment: Current knowledge and future directions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 58, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Lu, S.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Hong, J.; Zhou, J.; Peng, X. The effects of vegetation restoration strategies and seasons on soil enzyme activities in the karst landscapes of Yunnan, southwest China. J. For. Res. 2020, 31, 1949–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhao, G.; Zang, S. Soil enzyme activities and their relationships with soil C, N, and P in peatlands from different types of permafrost regions, Northeast China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 670769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, S.A.; Ostle, N.; Bardgett, R.D.; Hopkins, D.W.; Vanbergen, A.J. Biochar in bioenergy cropping systems: Impacts on soil faunal communities and linked ecosystem processes. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, B.; Lanfranconi, M.P.; Piña-Villalonga, J.M.; Bosch, R. Anthropogenic perturbations in marine microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choppala, G.K.; Bolan, N.S.; Chung, J.W.; Chuasavathi, T. Biochar reduces the bioavailability and phytotoxicity of heavy metals. Plant Soil 2011, 348, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Masto, R.E.; Ram, L.C.; Sarkar, P.; George, J.; Selvi, V.A. Biochar preparation from Parthenium hysterophorus and its potential use in soil application. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 55, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupiano, D.; Cocozza, C.; Baronti, S.; Amendola, C.; Vaccari, F.P.; Lustrato, G.; Lonardo, S.D.; Fantasma, F.; Tognetti, R.; Scippa, G.S. The effects of biochar and its combination with compost on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) growth, soil properties, and soil microbial activity and abundance. Int. J. Agron. 2017, 2017, 3158207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Qin, J.; Wang, B.; Chen, D.; Dai, Z.; Niu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F. Comprehensive evaluation of biogas slurry fertility: A study based on the effects of biogas slurry irrigation on soil microorganisms and enzyme activities in winter wheat fields. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, Y.M.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Ok, Y.S.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effects of polyacrylamide, biopolymer, and biochar on decomposition of soil organic matter and plant residues as determined by 14C and enzyme activities. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2012, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameloot, N.; De Neve, S.; Jegajeevagan, K.; Yildiz, G.; Buchan, D.; Funkuin, Y.N.; Prins, W.; Bouckaert, L.; Sleutel, S. Short-term CO2 and N2O emissions and microbial properties of biochar amended sandy loam soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, M.; Lu, J.; Ren, T.; Cong, R.; Lu, Z.; Li, X. Integrated rice–aquatic animals culture systems promote the sustainable development of agriculture by improving soil fertility and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Field Crops Res. 2023, 299, 108970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Li, G.; Yan, L. Changes in soil carbon fractions and enzyme activities under different vegetation types of the northern Loess Plateau. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 12211–12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Effects of organic fertilizer substitution for chemical fertilizer on tea yield and quality: A meta-analysis focusing on alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 254, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Bai, T.; Yu, W.; Zhu, T.; Li, D.; Ye, C.; Liu, M.; Hu, S. Soil pH and precipitation controls on organic carbon retention from organic amendments across soil orders: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 207, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sanusi, I.A.; Wang, J.; Ye, X.; Kana, E.B.G.; Olaniran, A.O.; Shao, H. Developments and prospects of farmland application of biogas slurry in China—A review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Song, D.; Xu, X.; Ai, C.; Liang, G.; Zhou, W. Investigating the effects of organic amendments on soil microbial composition and its linkage to soil organic carbon: A global meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 894, 164899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, M.; Gao, Y. The mechanism of the dose effect of straw on soil respiration: Evidence from enzymatic stoichiometry and functional genes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 168, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednik, M.; Medyńska-Juraszek, A.; Ćwieląg-Piasecka, I.; Dudek, M. Enzyme activity and dissolved organic carbon content in soils amended with different types of biochar and exogenous organic matter. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, J.; Mi, M.; Jin, Z.; Wong, M.H.; Shan, S.; Ping, L. Persistent effects of swine manure biochar and biogas slurry application on soil nitrogen content and quality of lotus root. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1359911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Huang, R. Adsorption of extracellular enzymes by biochar: Impacts of enzyme and biochar properties. Geoderma 2024, 451, 117082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, T.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhao, X.; Gao, W.; Jeewani, P.H. Distinct biophysical and chemical mechanisms governing sucrose mineralization and soil organic carbon priming in biochar amended soils: Evidence from 10 years of field studies. Biochar 2024, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yi, F.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Chen, H. Biochar dose-dependent impacts on soil bacterial and fungal diversity across the globe. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 930, 172509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, É.M.G.; Reis, M.M.; Frazão, L.A.; da Mata Terra, L.E.; Lopes, E.F.; Dos Santos, M.M.; Fernandes, L.A. Biochar increases enzyme activity and total microbial quality of soil grown with sugarcane. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile-Doelsch, I.; Balesdent, J.; Pellerin, S. Reviews and syntheses: The mechanisms underlying carbon storage in soil. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 5223–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Diao, F.; Gao, M.; Wang, X.; Shi, X. Effects of biogas slurry combined with chemical fertilizer on Allium fistulosum yields, soil nutrients, microorganisms, and enzymes activities. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2024, 32, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Gao, T.; Wu, C.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Han, L.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y.; Liao, X. Consecutive Application of Biogas Slurry Improved the Cumulative Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Regulating the Soil Carbon Pool. Plants 2026, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lim, J.W.; Lee, J.T.E.; Cheong, J.C.; Hoy, S.H.; Hu, Q.; Tan, J.K.N.; Chiam, Z.; Arora, S.; Lum, T.Q.H.; et al. Food-waste anaerobic digestate as a fertilizer: The agronomic properties of untreated digestate and biochar-filtered digestate residue. Waste Manag. 2021, 136, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, Y.; Zhan, X.; Li, T.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q. Enhancing soil fertility and organic carbon stability with high-nitrogen biogas slurry: Benefits and environmental risks. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 384, 125584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Naveed, M.; Azeem, M.; Yaseen, M.; Ullah, R.; Alamri, S.; Ain Farooq, Q.U.; Siddiqui, M.H. Efficiency of wheat straw biochar in combination with compost and biogas slurry for enhancing nutritional status and productivity of soil and plant. Plants 2020, 9, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Tian, H.; Song, S.; Tan, H.T.; Lee, J.T.; Zhang, J.; Sharma, P.; Tiong, Y.; Tong, Y.W. Effects of digestate-encapsulated biochar on plant growth, soil microbiome and nitrogen leaching. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 334, 117481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yi, X.; Ni, K.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Cai, Y.; et al. Patterns and abiotic drivers of soil organic carbon in perennial tea plantation system of China. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Li, W.; Dai, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Daniell, T.J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Yin, W.; Wang, X. Patterns and determinants of microbial- and plant-derived carbon contributions to soil organic carbon in tea plantation chronosequence. Plant Soil. 2024, 505, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S.; Seppänen, A.; Mganga, K.Z.; Sietiö, O.-M.; Glaser, B.; Karhu, K. Biochar reduced the mineralization of native and added soil organic carbon: Evidence of negative priming and enhanced microbial carbon use efficiency. Biochar 2024, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Feng, X.; Song, H.; Hao, Z.; Ma, S.; Hu, H.; Chu, Q. Enzymatic reactions throughout cultivation, processing, storage and post-processing: Progressive sculpture of tea quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.