Abstract

Soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration plays a vital role in sustaining soil productivity and mitigating climate change. Although biochar and charcoal-based fertilizers are known to enhance SOC sequestration, current understanding is predominantly derived from studies applying high doses. With the goal of elucidating the mechanisms through which long-term, low-dose biochar application influences SOC composition and stability, this study evaluated the long-term impacts of biochar and carbon-based fertilizers on SOC content, chemical structure, and microbial residual carbon assessed via amino sugar biomarkers. The following features are demonstrated by this study: (1) The application of biochar and carbon-based fertilizers significantly increased the contents of active organic carbon components (DOC, MBC, POC) and stable carbon components (MAOC, humic carbon) in the plow layer soil. Notably, the C50 treatment reduced the easily oxidizable organic carbon (EOC) content by 19.25% compared to the control. (2) Long-term application increased the relative abundance of aromatic functional groups in SOC, enhanced SOC decomposition resistance (as reflected by the F-index). Compared with NPK, the BBF treatment increased the F-index by 21.28% and 25.00% in the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers. (3) The BBF treatment significantly increased both soil amino sugar content and the contribution of microbial residual carbon to SOC. Specifically, it elevated the levels of GluN, GalN, and MurN by 9.24% to 33.31% across soil layers. Fungal residual carbon constituted the dominant fraction across all treatments. In summary, the content and stability of SOC are enhanced by biochar and biochar-based fertilizers through synergistic mechanisms that involve altering its chemical composition and stimulating the accumulation of fungal residual carbon.

1. Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activities have resulted in substantial emissions of greenhouse gases, which have driven a continuous increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations and profoundly altered global climate patterns. This challenge now stands as one of the most pressing issues facing human society [1]. Extensive studies have demonstrated the significant potential of soils to sequester atmospheric CO2, offering a viable pathway for achieving critical emission reduction targets. As the largest carbon pool in terrestrial ecosystems, soil stores 2–4 times more carbon than the aboveground biomass and about three times more carbon than the atmosphere. Even minor changes in soil carbon stocks can substantially affect atmospheric CO2 concentrations [2], playing a key role in regulating the global carbon balance. As a major agricultural country, China’s ability to manage soil organic carbon (SOC) and enhance carbon sequestration through improved farmland management practices is essential for realizing its “Dual Carbon” strategic goals.

SOC plays a fundamental role in soil systems, where it is stabilized and accumulated through biological processes. Based on decomposability and turnover rate, SOC is commonly divided into active, slow-cycling, and recalcitrant pools [3]. The active organic carbon fraction serves as an important carbon and nutrient source in soil, responds rapidly to agricultural management practices, and is closely associated with potential soil productivity. In contrast, slow-cycling and recalcitrant organic carbon are less accessible to microbial decomposition and exhibit limited sensitivity to environmental changes, making them key indicators of long-term carbon accumulation and stability [4]. Farmland SOC dynamics are strongly influenced by agricultural management practices, particularly tillage, fertilization regimes, and cropping systems [5,6,7].

SOC stability is a key indicator for evaluating the long-term carbon sequestration potential of soils. While the mechanisms governing SOC stability remain debated, one prominent view suggests that the inherent chemical structure and molecular properties of SOC confer resistance to microbial degradation and limit its bioavailability [2]. The soil microbial carbon pump (MCP) framework further underscores the central role of microbial processes in the formation of stable soil organic matter [8]. Microbial residual carbon (MRC) may contribute more than 50% of total SOC [9], highlighting its importance in carbon. Amino sugars—including glucosamine (GluN), galactosamine (GalN), and muramic acid (MurN)—constitute over 90% of microbial residue content. These biomarkers can be adsorbed onto mineral surfaces or physically protected within soil aggregates, enabling long-term preservation and serving as reliable tracers of microbial-derived carbon in SOC [10]. Understanding how management practices enhance carbon stability through regulating the chemical composition of soil organic carbon and promoting the accumulation of microbial residues has become a key research objective.

Biochar and biochar-based fertilizers represent a novel soil amendment strategy with carbon sequestration potential [11,12]. Owing to their high adsorption capacity, they enhance nutrient retention and modulate release kinetics, thereby reducing losses through leaching and volatilization [13]. Both biochar and biochar-based fertilizers have been shown to improve soil nutrient availability, enhance soil physical structure [14], and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions [15]. The high porosity and large specific surface area of biochar provide a favorable habitat for soil microorganisms, supporting their survival and activity [16]. Numerous studies have confirmed the potential of biochar in enhancing carbon sequestration. Although biochar and biochar-based fertilizers are showed to enhance soil SOC sequestration and stability, most current evidence from studies using high application rates (e.g., up to 10% of soil dry weight) [11,17,18]. It remains unclear whether long-term, low-dose biochar amendment can similarly improve the composition, and stability of SOC pools. This study tests the following hypothesis: (1) physicochemical pathways promote the transformation of SOC into mineral-associated forms and increase its chemical complexity; (2) activation of the soil microbial carbon pump, which is dominated by the accumulation of fungal-derived residual carbon, significantly increases contribution to stable carbon pools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

This study was based on a long-term field experiment established at the National Peanut Industry Technology System, Soil Fertility Experimental Station, Shenyang Agricultural University, situated in Shenyang, Liaoning Province (123°33′ E, 40°48′ N). The site lies in the southern core area of the Songliao Plain and experiences a temperate humid to semi-humid monsoon climate. The mean annual temperature ranges from 7.0 °C to 8.1 °C, with a cumulative temperature above 10 °C of 3300–3400 °C. The frost-free period lasts 148 to 180 days, and the average rainfall during the growing season is 547 mm. The soil at the experimental site is classified as brown soil. The long-term trial was initiated in 2011, and soil samples were taken in the autumn of 2010 for the analysis of basic soil chemical properties (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic chemical properties of soil at the beginning of experiment.

2.2. Experimental Design

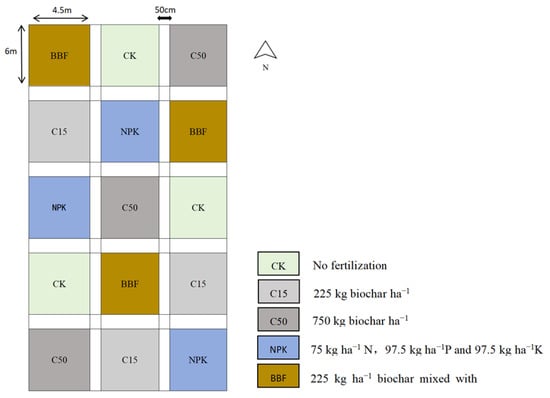

The field experiment utilized the Baisha peanut variety, cultivated under a continuous annual cropping system (Figure 1). Peanuts were sown in a double-row arrangement on broad ridges with 90 cm ridge spacing. Each ridge contained two rows spaced 30 cm apart, with hills spaced 15 cm apart and two plants per hill, resulting in a planting density of 300,000 plants per hectare. All fertilizers were applied as a basal dose prior to planting using a furrow-application method. Furrows were placed along the center of each ridge at a depth of 15–20 cm and subsequently covered with soil. Each experimental plot measured 27 m2 (6 m × 4.5 m). The treatments were arranged in a completely randomized block design with three replicates.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental design. CK, no fertilizer and biochar; C15, application of low amount of biochar; C50, application of high amount of biochar; NPK, application of chemical fertilizers; BBF, application of biochar-based fertilizer. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Biochar was produced from raw materials including corn stalks and peanut shells. The feedstocks were first dried, then sequentially crushed, sieved, and washed. Pyrolysis was conducted under oxygen-limited conditions at 500 °C for 30–60 min. The mass yield of biochar from the feedstock was approximately 1:3 (biochar: feedstock). Its composition was as follows: C 33.32%, N 0.50%, P2O5 0.84%, K2O 0.59%. The physicochemical properties of the biochar, including specific surface area and pore size, are provided in our earlier work [19]. For the preparation of biochar-based fertilizer (BBF), a nutrient ratio of 10-13-13 (N:P2O5:K2O) was targeted. The amounts of individual fertilizer components were calculated according to this ratio and their respective nutrient contents. The production process primarily followed the procedure described in a national invention patent authorized to the research team: “A Carbon-Based Slow-Release Fertilizer for Peanuts and Its Preparation Method” (Patent No. CN200710143933.6). The chemical fertilizers used included urea (N 46%), diammonium phosphate (18-46-0), and potassium sulfate (K2O 50%).

The experiment comprised five treatments: (1) control (CK, no fertilizer and biochar); (2) low dosages of biochar (C15); (3) high dosages of biochar (C50); (4) chemical fertilizer (NPK); and (5) biochar-based fertilizer (BBF). The nutrient inputs for each treatment are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Carbon and nutrient treatments for different treatments.

2.3. Soil Sampling and Preparations

Soil samples were collected during the peanut ripening period in the fall of 2023 using a randomized multi-point mixing method. In each plot, soil was randomly sampled from five locations in both the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers along an “S”-shaped pattern and combined to form a composite sample. Each composite sample was then processed as follows: one portion was stored at 4 °C for the analysis of soil microbial carbon (MBC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC); another portion was air-dried and passed through a 10-mesh sieve for the determination of particulate organic carbon (POC) and mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC); a third portion was passed through a 60-mesh sieve to analyze soil easily oxidized organic carbon (EOC) and humus carbon; and the remaining soil was sieved through a 100-mesh sieve for measuring soil organic carbon content, organic carbon functional group structure, and amino sugar content.

2.4. Determination of Soil Organic Carbon Components

EOC was determined by oxidation with 333 mmol L−1 KMnO4 (≥99.5%, Analytical Reagent, AR, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent) according to Blair et al. [20]. The content was calculated as follows:

where Δc represents the change in KMnO4 concentration (mmol L−1), and m is the soil mass (g). It is assumed that 1 mmol of KMnO4 consumed corresponds to 9 mg of oxidized carbon.

DOC was extracted with 0.5 mol L−1 K2SO4 (≥99.0%, AR, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai, China) following the procedure of Bolan et al. [21]. This mild extraction method is effective for isolating the labile carbon fraction in soil, which represents the pool of carbon most readily accessible to plants and microorganisms over the short term. Fresh soil equivalent to 5 g dry weight was shaken with 25 mL of extractant at 180 r min−1 for 1 h, centrifuged at 2500 r min−1 for 15 min, and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The supernatant was analyzed using a Multi N/C 3100 TOC analyzer (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany).

MBC was determined by the chloroform fumigation–extraction method [22]. This approach quantifies the metabolically active MBC pool by lysing microbial cells through chloroform fumigation and then measuring the difference in extractable carbon between fumigated and non-fumigated soil samples. Fumigated and non-fumigated soils were extracted with 0.5 mol L−1 K2SO4, filtered, and analyzed with the TOC analyzer. MBC was calculated as:

where Ec denotes the difference in extractable carbon between fumigated and non-fumigated samples.

POC and MAOC were separated as described by Cambardella and Elliott [23]. A 20 g portion of air-dried soil (<2 mm) was dispersed in 100 mL of 5 g L−1 sodium hexametaphosphate and shaken at 90 r min−1 for 18 h. The suspension was washed through a 0.053 mm sieve to separate the particulate (>0.053 mm) and mineral-associated (<0.053 mm) fractions. This fractionation is based on their distinct physical protection mechanisms, allowing for the investigation of organic carbon distribution across different stabilization pathways. After removing plant debris, both fractions were dried at 60 °C, weighed to determine mass proportions, and analyzed for organic carbon using an Elementar Vario EL III analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). The contents were calculated as:

POC/MAOC (g kg−1) = Organic carbon content of fraction (g kg−1) × Mass proportion of fraction (%)

Soil humus carbon was analyzed by the sodium pyrophosphate–potassium dichromate volumetric method [24], following International Humic Substances Society guidelines. Total humus carbon and humic acid carbon were determined by external heating with potassium dichromate. Fulvic acid carbon was calculated as the difference between total humus carbon and humic acid carbon. This method is designed to systematically separate and quantify humic components in soil based on their distinct chemical properties and stability. It differentiates between total humic carbon, humic acid carbon (characterized by higher molecular weight and greater chemical inertness), and fulvic acid carbon (which has a lower molecular weight and higher mobility).

2.5. Determination of Chemical Structure of Soil Organic Carbon

The chemical structure of soil organic carbon was characterized by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Nicolet IS50, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) using the potassium bromide pellet method. Absorbance spectra were analyzed to identify characteristic peaks, which were assigned to specific functional groups based on standard interpretations. The major absorption peaks and their corresponding functional groups are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Absorption peak attributes for infrared spectroscopy identification of organic carbon functional groups.

Each characteristic infrared absorption peak was associated with specific functional groups in soil organic carbon. The relative content of a target functional group was estimated by calculating the ratio of its corresponding peak area to the total area of all characteristic peaks. The resistance of organic carbon to decomposition was evaluated using the ratio of the peak areas of non-decomposable functional groups to those of decomposable functional groups, calculated as follows [25,26]:

where F represents the decomposition resistance of organic carbon, indicating the degree of soil organic carbon stabilization; SC=O/C=C and SC=O/C=N denote the peak areas corresponding to C=O/C=C and C=O/C=N functional group; and SC-O and SO-H/N-H refer to the peak areas of C-O and O-H/N-H functional groups.

2.6. Determination of Soil Amino Sugars

Soil amino sugars were analyzed according to the method of Zhang and Amelung [27] using gas chromatography (7890B MIDI Sherlock®, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) with hydrolysis, extraction, and derivatization to form sugar nitrile acetyl ester derivatives. The contributions of fungal and bacterial residues to soil microbial residual carbon were quantified by extracting and measuring specific amino sugars (e.g., glucosamine and peptidoglycan). These compounds serve as biomarkers, providing key evidence for elucidating microbial transformation pathways of organic carbon. The content of each amino sugar (Cx, mg kg−1) was quantified by the internal standard method using Equation (5):

where Ci is the concentration (mg kg−1) of the internal standard 1 (inositol); Gi is the mass of inositol in the sample assay; Ax is the peak area of the target amino sugar; and Rf is the relative correction factor of determined from standard samples and the internal standard 1.

Quantification of GluN, GalN, and MurA was based on their respective chromatographic peak areas. The total amino sugars (AS) was calculated as the sum of GluN, GalN, and MurA.

Fungal residue carbon (FRC, g kg−1), bacterial residue carbon (BRC, g kg−1), and total microbial residue carbon (MRC, g kg−1) were calculated using Equations (6)–(8):

where CGluN and CMurN represent the contents (mg kg−1) of glucosamine and muramic acid; 179.17 and 251.23 are the molecular weights of GluN and MurA; 9 is the conversion factor for fungal carbon derived from GluN; and 45 is the conversion factor for bacterial carbon derived from MurN.

FRC = [CGluN/179.17 − 2 × (CMurN/251.23)] × 179.17 × 9

BRC = 45 × CMurN

MRC = FRC + BRC

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Prior to data analysis, the normality of the data was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variance was assessed as part of one-way ANOVA in SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All datasets met the normality assumption (all > 0.05) and the assumption of homogeneity of variance, thereby satisfying the prerequisites for parametric analysis of variance. All data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2021 and statistically analyzed with SPSS 27.0. Treatment differences were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of p < 0.05. To assess potential interactive effects, the ANOVA model was reanalyzed to explicitly include the “soil layer depth × treatment” interaction term. Results revealed no statistically significant interaction effects for any of the response variables measured. Relationships among variables were evaluated using Pearson correlation analysis, with significance denoted as p < 0.05 * and p < 0.01 **. Infrared spectral data of organic carbon functional groups were processed and peak-fitted using OMNIC 9.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Origin 2024 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). All figures were also generated using Origin 2024. All graphical data are presented as means ± standard error (n = 3).

3. Results

3.1. Effects on Soil Organic Carbon Components

3.1.1. Effects on Soil Active Organic Carbon Components

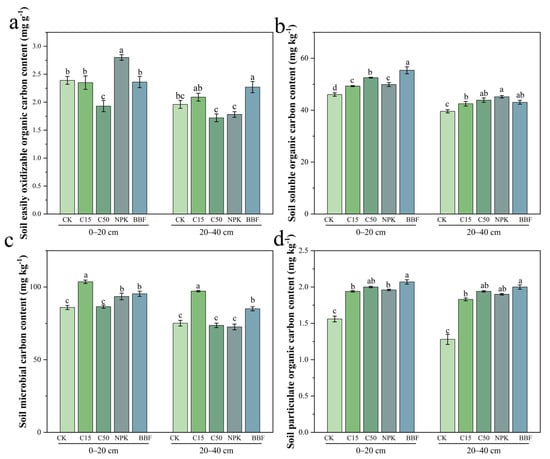

Biochar and biochar-based fertilizer application significantly affected EOC content (Figure 2a). In the 0–20 cm layer, the C50 treatment reduced EOC by 19.24% and 17.78% compared to CK and C15 (p < 0.05), while the BBF treatment decreased EOC by 15.71% relative to NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm layer, EOC remained lower under C50, whereas BBF resulted in the highest EOC content, exceeding NPK by 27.53% (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of different treatments on the contents of easily oxidizable organic carbon (EOC) (a), dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (b), microbial biomass carbon (MBC) (c), and particulate organic carbon (POC) (d) in different soil layers. CK, no fertilizer and biochar; C15, application of low amount of biochar; C50, application of high amount of biochar; NPK, application of chemical fertilizers; BBF, application of biochar-based fertilizer. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3).

DOC content was also influenced by organic amendments (Figure 2b). In the 0–20 cm layer, C15 and C50 increased DOC by 7.06% and 13.73% over CK (p < 0.05). The BBF treatment yielded the highest DOC content (55.37 mg kg−1), which was 11.00% higher than that under NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm layer, C15 and C50 continued to enhance DOC, though the maximum value (45.17 mg kg−1) was observed in the NPK treatment.

MBC responded distinctly to the treatments (Figure 2c). In the topsoil, C15 increased MBC by 13.22% compared to CK (p < 0.05), while BBF showed a non-significant increase over NPK. In the subsurface layer, C15 raised MBC by 29.36% over CK (p < 0.05), and BBF exceeded NPK by 17.21% (p < 0.05).

POC content increased consistently across soil layers under organic amendments (Figure 2d). In the 0–20 cm layer, C15 and C50 enhanced POC by 24.36% and 28.21% over CK, (p < 0.05), and BBF surpassed NPK by 5.61% (p < 0.05). These effects were more pronounced in the 20–40 cm layer, where C15 and C50 raised POC by 42.97% and 51.56% over CK (p < 0.05), and BBF resulted in the highest POC content.

3.1.2. Effects on Soil Recalcitrant Organic Carbon Components

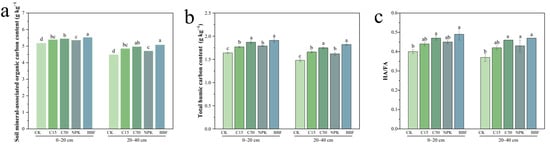

Among all SOC fractions, the MAOC and humified carbon pools, which represent long-term stability, showed the most consistent and significant increases in response to organic amendments. In the topsoil, both C15 and C50 significantly increased MAOC content compared to CK by 4.26% and 5.42% (p < 0.05). Under the BBF treatment, MAOC content reached 5.53 g kg−1, representing a significant increase of 3.17% over NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm layer, MAOC trends were consistent with those in topsoil: C15 and C50 increased MAOC by 8.26% and 19.94% over CK (p < 0.05), while BBF exceeded NPK by 7.86% (p < 0.05, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Effects of different treatments on the contents of mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC) (a), total humic carbon (b), and the ratio of humic acid to fulvic acid (HA/FA) (c) in different soil layers. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). See Figure 1 for abbreviations.

Total humic carbon responded positively to biochar and biochar-based fertilizers (Figure 3b). In the 0–20 cm layer, C15 and C50 increased total humic carbon by 7.93% and 14.02% over CK (p < 0.05), with C50 being 5.65% higher than C15 (p < 0.05). Additionally, BBF resulted in a 6.70% increase relative to NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm layer, total humic carbon content decreased overall but maintained similar trends with the topsoil: C15 and C50 enhanced it by 12.16% and 18.24%, compared to CK (p < 0.05), and BBF exceeded NPK by 12.53% (p < 0.05).

The humic acid to fulvic acid ratio (HA/FA), an indicator of humification degree and soil organic carbon stability, generally increased under amendments (Figure 3c). In topsoil, HA/FA showed a gradual increase from CK to C50, with the latter being 17.5% higher than CK (p < 0.05). The BBF treatment showed a non-significant increase in the HA/FA ratio relative to the NPK treatment. These patterns were consistent in the 20–40 cm layer.

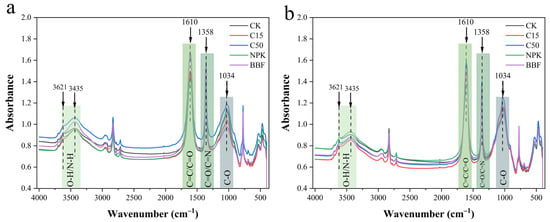

3.2. Effects on Soil Organic Carbon Structure

3.2.1. Effects on Functional Group Content of Soil Organic Carbon

The infrared spectral features of soil organic carbon functional groups showed high similarity across all treatments (Figure 4), suggesting that long-term application of biochar or biochar-based fertilizers did not substantially alter the fundamental chemical composition of soil organic carbon. The predominant functional groups consistently included alcohols/phenols, aliphatic compounds, aromatic structures, polysaccharides, and organosilicon compounds across the experimental treatments. The relative content of different functional groups was characterized by calculating the percentage of each peak area relative to the total peak area, expressed as the relative peak area (based on the raw spectral data in Table 4, as presented in Figure 4 and Table 5). The C=C/C=O and C=O/C=N functional groups exhibited strong responses to biochar and biochar-based fertilizers in both soil layers. In the 0–20 cm soil layer, the relative peak area of C=C/C=O increased significantly under C15 and C50 treatments compared to CK, with C50 exceeding C15 by 4.00%. The BBF treatment increased this area by 16.67% relative to NPK. For the C=O/C=N groups, both C15 and C50 significantly increased the relative peak area by 14.29% over CK (p < 0.05), while BBF increased it by 12.50% compared to NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm soil layer, the relative peak area of C=C/C=O under C15 and C50 increased by 26.31% compared to CK (p < 0.05), and BBF exceeded NPK by 18.18%. The C=O/C=N groups showed consistent trends with the surface soil: C15 and C50 enhanced the relative peak area by 40.00% over CK, while BBF increased it by 33.33% compared to NPK (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of different treatments on soil organic carbon functional groups across soil layers: (a) 0–20 cm and (b) 20–40 cm. Four characteristic infrared absorption peaks were analyzed, corresponding to the following organic functional groups: 1034 cm−1 (C–O stretching in polysaccharides), 1358 cm−1 (C=O/C=N stretching in aromatic compounds and carboxylic acids), 1610 cm−1 (C=C/C=O stretching in aromatic rings, quinones, and amides), and 3621 cm−1 and 3435 cm−1 (O–H stretching in alcohols/phenols and N–H stretching in proteins/amino sugars). See Figure 1 for abbreviations.

Table 4.

Peak areas in different soil layers under varied treatments.

Table 5.

Relative FTIR peak intensities across soil layers and treatments.

3.2.2. Effects on the Anti-Degradation Ability of Soil Organic Carbon

SOC decomposition resistance was significantly enhanced by the application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers (Figure 5). The chemical stability of SOC, as quantified by its resistance to decomposition, was fundamentally enhanced by biochar and BBF application. This parameter was quantified based on the peak area ratio of recalcitrant to labile functional groups (Equation (4); for raw data, see Table 4). In the 0–20 cm soil layer, resistance values progressively increased across the CK, C15, and C50 treatments. The C50 treatment improved resistance by 28.57% and 8.00% compared to CK and C15 (p < 0.05). Similarly, the BBF treatment increased resistance by 21.28% relative to NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm soil layer, decomposition resistance under C15 and C50 treatments significantly exceeded that of CK, with increases of 33.33% and 36.36% (p < 0.05). The BBF treatment also resulted in a 25.00% higher resistance than NPK (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of different treatments on the resistance of soil organic carbon to decomposition in different soil layers. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). See Figure 1 for abbreviations.

3.3. Effects on Soil Microbial Residual Carbon

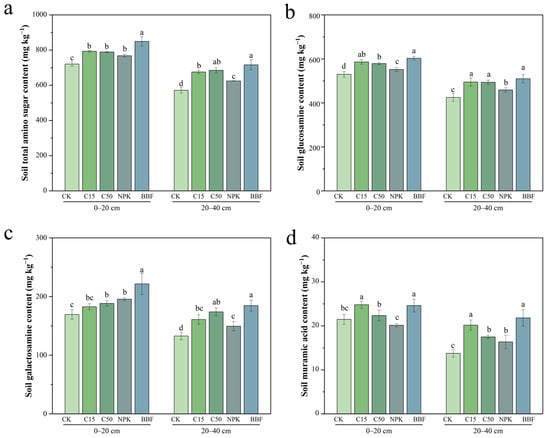

3.3.1. Effects on Soil Amino Sugar

Biochar and biochar-based fertilizer amendments significantly enhanced total amino sugar content across both soil layers (Figure 6a). In the topsoil, C15 and C50 treatments increased total amino sugars by 10.09% and 9.50% over CK (p < 0.05). The BBF treatment yielded the highest content in this layer, exceeding NPK by 10.61% (p < 0.05). In the subsurface layer, C15 and C50 further enhanced total amino sugars by 18.21% and 19.87%, compared to CK (p < 0.05). The BBF treatment demonstrated the most substantial improvement, increasing content by 14.65% relative to NPK (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of different treatments on the contents of total amino sugar content (a), glucosamine (b), galactosamine (c), and muramic acid (d) in different soil layers. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). See Figure 1 for abbreviations.

Biochar and biochar-based fertilizer significantly enhanced the contents of GluN in both soil layers (Figure 6b). In the 0–20 cm layer, GluN content increased by 10.61% and 9.22% under C15 and C50, compared to CK (p < 0.05), while BBF increased it by 9.24% over NPK (p < 0.05). These trends persisted in the 20–40 cm layer, where BBF raised GluN content by 11.09% relative to NPK (p < 0.05). GalN content was significantly enhanced by the application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizer (Figure 6c). In topsoil, C50 increased it by 11.10% over CK (p < 0.05), while BBF enhanced it by 13.30% compared to NPK (p < 0.05). In the subsurface layer, C15 and C50 raised GalN content by 21.12% and 30.92%, over CK, and BBF exceeded NPK by 23.52% (p < 0.05). MurA content also showed significant responses (Figure 6d). In the 0–20 cm layer, C15 treatment significantly increased MurA by 15.51% compared to CK (p < 0.05), while BBF treatment enhanced it by 22.19% relative to NPK (p < 0.05). In the 20–40 cm layer, both C15 and C50 treatments increased MurA content by 46.51% and 27.11%, over CK (p < 0.05). In addition, MurA levels under NPK and BBF treatments mirrored the trends observed in the topsoil.

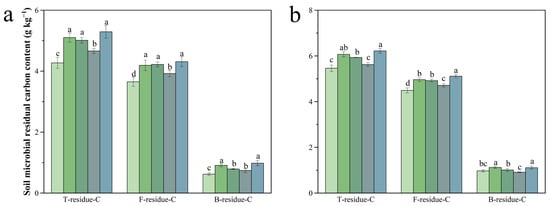

3.3.2. Effects on Soil Microbial Residual Carbon Content

Biochar and biochar-based fertilizer amendments significantly enhanced MRC pools in both soil layers, though concentrations were generally lower in the subsurface (20–40 cm) than in the plow layer (0–20 cm). In the 0–20 cm soil layer, both C15 and C50 treatments significantly increased the contents of MRC and FRC compared to CK. The C15 treatment also enhanced BRC by 15.46% relative to CK (p < 0.05). Compared with NPK, the BBF treatment increased MRC, FRC, and BRC by 10.68%, 8.49%, and 21.98% (p < 0.05, Figure 7a). In the 20–40 cm soil layer, MRC and FRC under C15 and C50 treatments remained significantly higher than those in CK. BRC showed a variation trend consistent with that in the topsoil. The BBF treatment significantly increased total MRC, FRC, and BRC by 13.52%, 9.95%, and 32.34%, compared to NPK (p < 0.05, Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Effects of different treatments on microbial residual carbon content in the 0–20 cm (a) and 20–40 cm (b) soil layers. T-residue-C, F-residue-C, and B-residue-C stand for the total MRC, fungi-derived MRC, and bacteria-derived MRC. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). See Figure 1 for abbreviations.

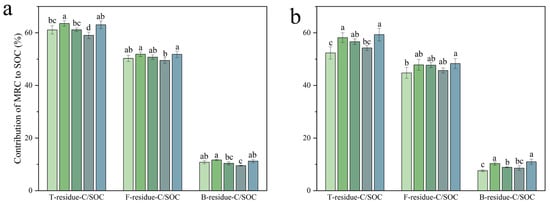

3.3.3. Contribution of Microbial Residual Carbon to Soil Organic Carbon

A key finding of this study was the significant accumulation of MRC and its increased contribution to SOC, driven primarily by fungal-derived compounds. In the 0–20 cm soil layer, total microbial residual carbon accounted for an average of 62.2% of the SOC across all treatments, confirming its role as a dominant component. Compared with the CK treatment, C15 significantly increased the contribution of total microbial residual carbon by 4.01% (p < 0.05). In contrast, neither C15 nor C50 showed a significant effect on the contributions of fungal and bacterial residual carbon relative to CK. When compared with the NPK treatment, BBF enhanced the contribution to SOC of total microbial, fungal, and bacterial residual carbon by 6.79%, 4.66%, and 17.86% (p < 0.05). Compositionally, FRC dominated the microbial-derived pool under organic amendments, accounting for 51.5% of SOC compared to 11.1% for bacterial residual carbon. These findings clearly demonstrate the predominant fungal origin of MRC in the surface layer (p < 0.05, Figure 8a).

Figure 8.

The contribution of microbial residual carbon to soil organic carbon in the 0–20 cm (a) and 20–40 cm (b) soil layer under different treatments. T-residue-C/SOC, F--residue-C/SOC, and B--residue-C/SOC represent the relative contributions of T-residue-C, F-residue-C, and B-residue-C to SOC. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in different treatments. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). See Figure 1 for abbreviations.

In the 20–40 cm soil layer, MRC accounted for an average of 56.1% of the SOC, a proportion lower than that in the plow layer (p < 0.05). The C15 and C50 treatments significantly increased the contributions of total microbial and bacterial residual carbon to SOC compared to CK, but did not significantly affect the fungal contribution. The BBF treatment, however, significantly increased the contributions of all three carbon pools relative to the NPK treatment. FRC dominated the microbial-derived SOC pool, accounting for 47.9% of total SOC, while BRC contributed 10.1% (p < 0.05). This composition highlights the predominant role of fungal-derived carbon in the subsurface layer (Figure 8b).

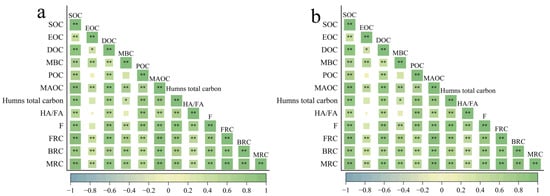

3.4. Correlation Analysis

SOC fractions were significantly intercorrelated in the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers (Figure 9a,b). SOC correlated positively with all fractions, most strongly with MAOC (r = 0.96, p < 0.01). MRC showed strong positive correlations with SOC, POC, DOC, MBC, and MAOC (r = 0.62–0.96, p < 0.01). The highest correlation was between MRC and MAOC (r = 0.96), indicating a central role for mineral binding in microbial residue stabilization. The correlation of FRC with MRC (r = 0.99) exceeded that of BRC (r = 0.92), underscoring the dominance of fungal residues. Labile carbon components (POC, DOC, MBC) were also significantly correlated with stable carbon pools (MAOC, total humic carbon) (r = 0.46–0.86, p < 0.01, p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Pearson’s correlations between SOC and other indicators in 0–20 cm (a) and 20–40 cm (b) layers. SOC, DOC, MBC, POC, MAOC, HA/FA, F, FRC, BRC, MRC stand for soil organic carbon, dissolved organic carbon, microbial biomass carbon, particulate organic carbon, mineral-associated organic carbon, humic acid to fulvic acid ratio, resistance of SOC to decomposition, fungal residual carbon, bacterial residue carbon and microbial residual carbon. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Biochar and Biochar-Based Fertilizer on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions

Soil active organic carbon is characterized by rapid turnover, low stability, and high susceptibility to mineralization, and is readily influenced by plant and microbial activities. In this study, the application of high rates of biochar and biochar-based fertilizer significantly reduced EOC content in the topsoil (Figure 2a), which aligns with the findings of Yan et al. [28]. The observed result is likely due to the inherent stability of biochar, derived from its aromatic and carbon-rich composition. Its addition to soil directly lowers the proportion of readily oxidizable organic carbon, supporting the long-term preservation of total SOC. An additional mechanism may involve the substantial specific surface area and porosity of high-dose biochar, which can directly sequester previously labile small-molecule organic matter through adsorption. This renders it inaccessible to microorganisms, thereby physically protecting it from decomposition [29]. The proportion of biochar that is readily available for microbial use is limited [30], a high-dose application can lead to a “negative stimulation effect” [31], as its small labile fraction is quickly consumed. This rapid depletion may prompt microorganisms to increasingly rely on unstable, EOC for energy and metabolic substrates. Additionally, long-term biochar application may reshape the microbial community structure, thereby modulating the decomposition kinetics of organic carbon and ultimately leading to a decline in EOC. It is noteworthy, however, that the long-term effect of biochar on EOC appears limited or even suppressive, implying a shift in the soil carbon pool from a labile to a more stable form—a transition that merits further investigation [28].

Long-term low-rate application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers in this study enhanced the contents of soil DOC and POC (Figure 2b,d). DOC is known for its fast turnover and high biodegradability, playing a critical role in SOC dynamics and CO2 emissions [32]. According to Amonette and Joseph [33], the introduction of biochar promotes the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups—such as carboxyl, lactone, phenolic, and carbonyl moieties—which enhance its solubility and raise soil DOC levels. Root-derived inputs may contribute to this increase: as roots grow into or through biochar-enriched zones, the release of humic acids and exudates can stimulate DOC accumulation in the surrounding soil [34]. The increase in POC following biochar and biochar-based fertilizer application aligns with results reported by Sun [35]. Biochar supports the formation and stabilization of soil aggregates [36], which can physically protect POC from rapid decomposition. Additionally, silicon and aluminum present in biochar ash may contribute to carbon stabilization in soil. For example, studies suggest that these ions can further inhibit the degradation of particulate organic carbon [37]. However, the net environmental impact of aluminum—whether it poses acidification risks or enhances stabilization—is strongly influenced by local conditions such as soil pH and organic matter type. Consequently, the long-term effects of these biochar components on soil carbon cycling require further context-specific evaluation.

The lack of a significant increase in MBC following high-rate biochar application observed in this study is consistent with the report by Liu et al. [38] (Figure 2c). A negative correlation between soil MBC and DOC has been documented in several studies [39,40], which may reflect the competition for available carbon sources between the two pools. One possible explanation is that the strong adsorption capacity of biochar restricts microbial access to soil organic matter by trapping microorganisms within its porous structure, limiting the conversion of organic substrates into MBC [41]. Alternatively, the high specific surface area of biochar may enhance the sorption of labile organic molecules onto external and internal surfaces, reducing their bioavailability and protecting them from microbial utilization [42].

MAOC comprises organic molecules bound to mineral surfaces or occluded within stable microaggregates, with formation mechanisms involving hydrogen bonding, ligand exchange, and van der Waals forces [43]. In this study, both biochar and biochar-based fertilizer significantly enhanced MAOC content (Figure 3a and Figure 9a,b), which is consistent with observations by Zhang et al. [44]. Previous research suggests that biochar particles interact extensively with soil minerals via surface functional groups [45,46], facilitating the formation of MAOC. The resulting organic–mineral–biochar complexes contribute to improved long-term stabilization of soil organic carbon. Although some of the observed increases in MAOC were modest in magnitude, they were statistically significant and exhibited consistent patterns. Given the long-term, low-dose experimental conditions and the inherently slow turnover rate of soil carbon, these changes likely indicate a meaningful directional shift in soil carbon sequestration processes.

Humus represents a key component and major repository of soil organic carbon, playing crucial roles in soil structure formation and nutrient accumulation [47]. The application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers significantly promoted the accumulation of humic carbon (Figure 3b and Figure 9a,b), which aligns with previous reports by Zhan et al. [48] and Jones et al. [49]. Long-term application of these amendments enhanced microbial metabolic activity, facilitating the decomposition and transformation of residual organic matter and humic substances, and thereby promoting the formation of high-molecular-weight organic polymers such as humic acids. The aliphatic and oxidized carbon fractions in biochar provided available carbon and energy sources for microorganisms, while simultaneously improving the microhabitat and raising the overall level of microbial metabolism [35,50]. These processes not only strengthened microbial degradation capacity but also promoted the accumulation of total humus and its component fractions.

HA/FA serves as an indicator of humus stability, reflecting the degree of humification and structural complexity of soil humus under different pedogenic conditions (Figure 3c). In the present study, the high dosages of biochar treatment significantly increased HA/FA, indicating that biochar application promoted the humification process. This phenomenon may be explained by two mechanisms. First, compared to the more structurally complex humic acid, fulvic acid has a lower molecular weight and simpler structure, making it more susceptible to decomposition, transformation, and adsorption onto biochar surfaces [51]. Second, biochar addition may enhance the condensation and aromaticity of humic acid, reduce its oxidation state, and increase its molecular complexity [52], thereby improving HA stability and suppressing its conversion to FA.

4.2. Effects of Biochar and Biochar-Based Fertilizer on Soil Organic Carbon Chemical Structure and Stability

The chemical structure of SOC significantly influences its content and stability [53], and these structural features are strongly affected by the molecular composition of exogenous organic inputs. As a carbon-rich soil amendment, biochar has attracted considerable interest due to its potential to enhance carbon sequestration. FTIR spectroscopy provides an effective approach for characterizing the composition of SOC and detecting changes in the nature and abundance of functional groups. In this study, long-term application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers did not change the types of SOC functional groups, which consistently comprised alcohols/phenols, aliphatics, aromatics, polysaccharides, and organosilicon compounds (Figure 4a,b), but it significantly influenced their relative distribution, in agreement with Zhao et al. [54].

Specifically, biochar and biochar-based fertilizers increased the relative peak intensities of C=O/C=N and C=C/C=O groups, while decreasing those of O–H and N–H groups (Table 5). Compared to the control, the relative abundance of aromatic functional groups increased with biochar application rate, likely due to the inherently high abundance of alkoxy and aromatic structures in biochar itself [55]. In addition, biochar application raised soil pH, which may promote deprotonation of weakly acidic O–H groups, further contributing to the observed spectral changes. These chemical modifications are associated with increased hydrophilicity and charge density of labile carbon fractions, enhancing the solubility of dissolved organic carbon while reducing the overall lability of SOC and improving its stability. Increased aromatic and aliphatic carbon content has been widely linked to greater SOC stability due to their recalcitrance to microbial decomposition [44,56]. In line with this, biochar and biochar-based fertilizer treatments in this study elevated the resistance of SOC to decomposition (Figure 5), supporting the view that aromatic functional groups contribute to SOC stability. Higher F-values thereby indicate a more stable SOC composition. While the aromatic characteristics of soil organic carbon can be influenced by multiple factors, the significant changes observed in this study—conducted under standardized treatments and homogeneous soil conditions—are primarily attributable to the application of biochar or biochar-based fertilizers.

4.3. Effects of Biochar and Biochar-Based Fertilizer on Soil Microbial Residual Carbon

MRC represents a major component of the stable soil carbon pool (Figure 8a,b and Figure 9a,b), contributing more than 50% of the total soil organic carbon. Amino sugars are widely used as biomarkers to quantify the contribution of MRC to SOC across different ecosystems [57]. In this study, the total amino sugar content was determined as the sum of GluN, GalN, and MurA. The results demonstrated that the application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers increased the contents of total amino sugars, GluN, GalN, and MurN in soil. Biochar amendment may improve soil texture and porosity while reducing clay adsorption, thereby enhancing microbial growth and promoting the accumulation of microbial residues, as reflected by amino sugar biomarkers [30,58]. In addition, biochar contains essential nutrients and energy sources that stimulate microbial metabolic activity [59], leading to increased microbial metabolites and subsequent accumulation of microbial necromass [57]. The effect of biochar on GluN content varied with application rate: low-dose biochar promoted GluN accumulation more effectively than high-dose biochar, suggesting a threshold beyond which the stimulatory effect diminishes. Some studies have even reported that high dosages of biochar doses can suppress MurA content [26]. After the application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers, MurA content showed variation trends similar to those of GluN across soil layers, indicating synchronized responses of fungal and bacterial residues to biochar input. This synchronization may be attributed to limited available nutrients in the soil, which promotes fungal proliferation. The decomposition of recalcitrant organic matter by fungi in turn provides carbon and nitrogen sources that support bacterial growth, thereby enhancing bacterial populations in the soil.

Soil microbial carbon includes both living MBC and MRC. This study revealed that biochar and biochar-based fertilizers promoted the accumulation of MRC to a greater extent than conventional chemical fertilization. The magnitude of this effect was dependent on the biochar application rate, which aligns with the results of Wang et al. [51]. In addition, both low-dose biochar and biochar-based fertilizer treatments increased MBC content (Figure 2c), suggesting a stimulatory effect of biochar on microbial growth and proliferation. The well-developed pore structure and specific surface characteristics of biochar provide favorable habitats for microorganisms and improve soil aeration and water permeability, thereby enhancing microbial abundance and activity [42,60]. In summary, the application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers not only increased the abundance of living microorganisms but also promoted the accumulation of microbial residues, indicating that these amendments can simultaneously enhance microbial activity and facilitate the formation of stable organic matter.

Although the addition of biochar led to an increase in microbial residual carbon content, its proportional contribution to SOC did not rise significantly (Figure 8a,b). This may be attributed to the fact that biochar, as a highly aromatic and stable form of organic carbon, directly enlarges the SOC pool upon application. In addition, biochar can enhance plant growth, resulting in greater input of root exudates and plant residues into the soil [34]. These plant-derived carbon sources are rapidly incorporated into the SOC pool, further expanding its size. In contrast, biochar-based fertilizer significantly enhanced the contribution of microbial residual carbon to SOC compared to chemical fertilizer alone. This likely occurs because biochar-based fertilizer provides both available carbon sources and essential mineral nutrients that support microbial growth, thereby fostering more efficient microbial assimilation [12] and promoting the conversion of carbon into stable microbial residues.

In this study, FRC showed a greater contribution to MRC than bacterial residual carbon BRC (Figure 7a,b and Figure 9a,b), which aligns with earlier reports [61]. In agricultural soils, fungal biomass has been reported to be threefold higher than bacterial biomass [62]. In addition, the inherent recalcitrance and high C/N ratio of biochar create more favorable conditions for fungal growth. Fungi exhibit a competitive advantage over bacteria in decomposing and utilizing recalcitrant organic materials in biochar as an energy source [51]. As a result, fungal residues contribute more substantially to soil carbon accumulation than bacterial residues following biomass turnover. Fungal cellular components decompose slowly, enhancing their persistence in soil [63]. These findings collectively underscore the dominant role of fungal residual carbon in the soil organic carbon pool. The observed increase in the proportion of microbial residual carbon mathematically indicates that its absolute increment exceeded that of total soil organic carbon. This suggests two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms: first, biochar input may have genuinely stimulated microbial activity and turnover, thereby enhancing the production of residual carbon [29]; second, biochar itself contains or can form relatively inert carbon fractions through chemical reactions [2]. Once incorporated into the total organic carbon pool, such carbon could alter the composition of its constituent fractions. Given the significant rise in the absolute content of microbial residual carbon observed here, we propose that the first mechanism—wherein biochar promotes microbial carbon accumulation by improving the soil microenvironment—is the primary driver of the proportional changes.

Building on these findings, we consider potential applications in agricultural management. In practice, the strategy of low-dose, multi-year application may be preferable to single, high-dose applications in terms of economic viability and ease of adoption. Large-scale implementation would depend on localized biochar feedstock supply, product standardization, and the refinement of associated agronomic practices. While no adverse effects were observed in this study, potential long-term risks such as heavy metal accumulation necessitate ongoing field monitoring and comprehensive life-cycle assessment.

This study sought to clarify the chemical and microbiological pathways through which long-term, low-dose biochar-based fertilizers affect soil organic carbon composition and stability. While our analysis focused on these key process indicators, a comprehensive evaluation of its feasibility as a mitigation technology applied to climate change will require future work integrating crop yield responses, full life-cycle carbon accounting, and economic cost–benefit analyses. Thus, the mechanisms delineated here lay the essential scientific groundwork for such integrated assessments.

5. Conclusions

This study utilized long-term field experiments with carbon-based fertilizers to systematically investigate the effects of continuous low-dose applications of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers on soil organic carbon fractions, chemical structure, and microbial residual carbon. In contrast to previous studies employing high application rates, our results indicate that even at low input levels, biochar can significantly promote the transformation of soil carbon pools toward more stable forms. The results of this study demonstrate that long-term application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers effectively enhanced both the labile (DOC, MBC, POC) and stable (MAOC, humic carbon) fractions of SOC, reducing the proportion of EOC in the topsoil and improving SOC stability. The application of biochar or biochar-based fertilizers enhanced the spectral intensity of aromatic functional groups and attenuated that of phenolic groups in the SOC, stabilizing its chemical structure and increasing its biochemical recalcitrance. The application of biochar and biochar-based fertilizers significantly enhanced the soil content of amino sugars and microbial residual carbon. Notably, treatments with low application rates increased the contribution of microbial residual carbon to total organic carbon, thereby improving the long-term stability of the soil organic carbon pool. At the application level, this study offers scientific support for sustainable carbon management strategies in agricultural systems. Biochar and carbon-based fertilizers not only improve soil carbon stability but also boost crop yield, showcasing their dual role in maintaining productivity while enhancing the stabilization of soil organic carbon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, B.W., C.G., and X.X.; data curation, B.W., Y.S., S.F., and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W. and C.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y., Y.Y., B.W., and C.G.; visualization, B.W. and X.X.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1500101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072679), and the National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System Peanut Industry Liaoning Innovation Team.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all who contributed to the research effort and the earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| EOC | Easily oxidizable organic carbon |

| POC | Particulate organic carbon |

| MBC | Microbial biomass carbon |

| MAOC | Mineral-associated organic carbon |

| GluN | Glucosamine |

| GalN | Galactosamine |

| MurN | Muramic acid |

| FRC | Fungal residue carbon |

| BRC | Bacterial residue carbon |

| MRC | Microbial residue carbon |

| AS | Amino sugars |

| AR | Analytical reagent |

References

- Goldstein, A.; Turner, W.R.; Spawn, S.A.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Cook-Patton, S.; Fargione, J.; Gibbs, H.K.; Griscom, B.; Hewson, J.H.; Howard, J.F.; et al. Protecting irrecoverable carbon in Earth’s ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumbore, S.E. Potential responses of soil organic carbon to global environmental change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 8284–8291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, W.; Prentice, I.C.; House, J.I.; Holland, E.A. Long-term sensitivity of soil carbon turnover to warming. Nature 2005, 433, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, L.J.; Hy, C.S.; Dong, W.X.; Li, X.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Liu, X.P.; Xiang, L.; Han, J. Effects of long-term exogenous organic material addition on the organic carbon composition of soil aggregates in farmlands of North China. Chin. J. Eco Agric. 2021, 29, 1384–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.W.; Xu, G.H.; Wang, N.; Xu, L.H. The effect of different tillage methods on soil organic carbon and its components in the black soil area of Northeast China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 3183–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.T.; Zhong, X.L.; Zhao, Q.G. Enhancement of soil quality in a rice-wheat rotation after long-term application of poultry litter and livestock manure. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2011, 31, 2837–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jackson, R.D.; Delucia, E.H.; Tiedije, J.M.; Liang, C. The soil microbial carbon pump: From conceptual insights to empirical assessments. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6032–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D.; Dai, G.; Feng, B.; Su, X.; Hu, H.; Li, K.; Han, W.; et al. Divergent accumulation of microbial necromass and plant lignin components in grassland soils. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joergensen, R.G. Amino sugars as specific indices for fungal and bacterial residues in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xia, L.; Groenigen, V.J.K.; Zhao, X.; Ti, C.; Wang, W.; Du, Z.; Fan, M.; Zhuang, M.; Smith, P.; et al. Sustained benefits of long-term biochar application for food security and climate change mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2509237122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Ren, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, L. Slow-release property and soil remediation mechanism of biochar-based fertilizers. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2021, 27, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondon, M.A.; Lehmann, J.; Ramírez, J.; Hurtado, M. Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with biochar additions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2007, 43, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, M.O.; Xin, X.; Nahayo, A.; Liu, X.; Korai, P.K.; Pan, G. Quantification of biochar effects on soil hydrological properties using meta-analysis of literature data. Geoderma 2016, 274, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tian, J.; Chen, L.; He, Q.; Liu, X.; Bian, R.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, K.; Xia, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Biochar boosted high oleic peanut production with enhanced root development and biological N fixation by diazotrophs in a sand-loamy Primisol. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 932, 173061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abhijeet, P.; Swagathnath, G.; Rangabhashiyam, S.; Asok Rajkumar, M.; Balasubramanian, P. Prediction of pyrolytic product composition and yield for various grass biomass feedstocks. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 10, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.M.; Busscher, W.J.; Laird, D.; Ahmedna, M.; Watts, D.W.; Niandou, M.A. Impact of Biochar Amendment on Fertility of a Southeastern Coastal Plain Soil. Soil Sci. 2009, 174, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Guo, Y.; Liang, F.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Cao, W.; Song, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, J. Global integrative meta-analysis of the responses in soil organic carbon stock to biochar amendment. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, Z.; Luan, S.; Hu, S.; Liu, X.; Li, N.; Han, X. A nine-year study: Continuous application of biochar achieves efficient potassium supply by modifying soil clay mineral composition and its potassium adsorption sites. J. Soils Sediments 2025, 25, 1829–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, G.J.; Lefroy, R.D.B.; Lisle, L. Soil carbon fractions based on their degree of oxidation, and the development of a carbon management index for agricultural systems. Aust. Agric. Res. 1995, 46, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.S.; Baskaran, S.; Thiagarajan, S. An Evaluation of the Methods of Measurement of Dissolved Organic Carbon in Soils, Manures, Sludges, and Stream Water. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1996, 27, 2723–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambardella, C.A.; Elliott, E.T. Particulate soil organic matter changes across a grassland cultivation sequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumada, K.; Sato, O.; Ohsumi, Y.; Ohta, S. Humus composition of mountain soils in Central Japan with special reference to the distribution of P type humic acid. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1967, 13, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margenot, A.J.; Calderón, F.J.; Bowles, T.M.; Parikh, S.J.; Jackson, L.E. Soil Organic Matter Functional Group Composition in Relation to Organic Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Fractions in Organically Managed Tomato Fields. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015, 79, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Xie, H.T.; Wang, F.P.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X.D. Effects of biochar incorporation on soil viable and necromass carbon in the luvisol soil. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Amelung, W. Gas chromatographic determination of muramic acid, glucosamine, mannosamine and galactosamine in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, S.; Yan, P.; Wei, Z.; Niu, X.; Zhang, H. Biochar application increased soil carbon sequestration by altering organic carbon components in aggregates. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 255, 106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathy, A.; Ray, J.; Paramasivan, B. Biochar amendments and its impact on soil biota for sustainable agriculture. Biochar 2020, 2, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar effects on soil biota-a review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S.; Seppänen, A.; Mganga, K.Z.; Sietiö, O.-M.; Glaser, B.; Karhu, K. Biochar reduced the mineralization of native and added soil organic carbon: Evidence of negative priming and enhanced microbial carbon use efficiency. Biochar 2024, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Costa, M.; Cerro-Galvez, E.; Martinez-Varela, A.; Casas, G.; Dachs, J. Anthropogenic dissolved organic carbon and marine microbiomes. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2646–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amonette, J.E.; Joseph, S. Characteristics of biochar: Microchemical properties. J. Party Sch. Shengli Oilfield 2009, 7, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Wang, J.; Dijkstra, F.A.; Lei, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, C. Nitrogen enrichment stimulates rhizosphere multi-element cycling genes via mediating plant biomass and root exudates. Soil Biol Biochem. 2024, 190, 109306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, X.; Bao, Z.; Bao, Z.; Gao, J.; Meng, J.; Han, X.; Lan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W. Responses of microbial necromass carbon and microbial community structure to straw-and straw-derived biochar in brown earth soil of Northeast China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 967746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, K.; Yang, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, H. Effects of biochar on the accumulation of necromass-derived carbon, the physical protection and microbial mineralization of soil organic carbon. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, L.D.; Zehetner, F.; Rampazzo, N.; Wimmer, B.; Soja, G. Long-term effects of biochar on soil physical properties. Geoderma 2016, 282, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W. Reducing CH4 and CO2 emissions from waterlogged paddy soil with biochar. J. Soils Sediments 2011, 11, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barg, A.K.; Edmonds, R.L. Influence of partial cutting on site microclimate, soil nitrogen dynamics, and microbial biomass in douglas-fir stands in western Washington. Can. J. For. Res. 1999, 29, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Song, T.; Chen, K.; Xu, X.; Peng, J.; Zhan, W.; Wang, Y.; Han, X. Influences of 6-year Application of Biochar and Biochar-based Compound Fertilizer on Soil Bioactivity on Brown Soil. Acta Agric. Boreali Sin. 2016, 31, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowles, M. Black carbon sequestration as an alternative to bioenergy. Biomass Bioenergy 2007, 31, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A.R.; Gao, B.; Ahn, M.-Y. Positive and negative carbon mineralization priming effects among a variety of biochar-amended soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xue, W.; Yan, Y.; Zuo, W.; Shan, Y.; Feng, K. The challenge of improving coastal mudflat soil: Formation and stability of organo-mineral complexes. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X.; Tavakkoli, E.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Du, Z. Biochar more than stubble management affected carbon allocation and persistence in soil matrix: A 9-year temperate cropland trial. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 3018–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, C.H.; Munroe, P.; Joseph, S.D.; Lin, Y.; Lehmann, J.; Muller, D.A. Analytical electron microscopy of black carbon and microaggregated mineral matter in Amazonian dark Earth. J. Microsc. 2012, 245, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgeon, V.; Fouché, J.; Leifeld, J.; Chenu, C.; Cornélis, J.T. Organo-mineral associations largely contribute to the stabilization of century-old pyrogenic organic matter in cropland soils. Geoderma 2021, 388, 114841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.A. The nature and dynamics of soil organic matter: Plant inputs, microbial transformations, and organic matter stabilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 98, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.Y.; Hao, L.W.; Yue, Q.; Liu, S.; Cao, D.Y.; Chen, W.F.; Lan, Y.; Qian, C.J. Effect of biochar application on the physicochemical properties and humus components of soybean meadow soil in Northeast China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 7797–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Rousk, J.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Deluca, T.H.; Murphy, D.V. Biochar-mediated changes in soil quality and plant growth in a three year field trial. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 45, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Lehmann, J.; Thies, J.E.; Burton, S.D.; Engelhard, M.H. Oxidation of black carbon by biotic and abiotic processes. Org. Geochem. 2006, 37, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Cao, D.Y.; Wang, D.; Zhan, Z.Y.; He, W.Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, W.F.; Lan, Y. Effects of Long-Term Application of Biochar on Nutrients, Fractions of Humic in Brown Soil. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 2612–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Song, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Kong, X.; Li, X.; Cui, D. Effects of Application of Biochar on Soil Humic Substances in Cropland under Wheat-Corn Rotation System. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2021, 5, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Mi, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Hu, K. Effects of combined application of bentonite and straw on organic carbonation structure and enzyme activity of soil in root zone. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2024, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, A. Effects of Biochar Pyrolyzed at Varying Temperatures on Soil Organic Carbon and Its Components: Influence on the Soil Active Organic Carbon. Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Lehmann, J.; Engelhard, M.H. Natural oxidation of black carbon in soils: Changes in molecular form and surface charge along a climosequence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, X.; Yu, X.; Dai, J.; Tian, X. Biochar superior than straw in enhancing soil carbon sequestration via altering organic matter stability and carbon cycle genes in Cd-Contaminated soil. Environ. Res. 2025, 287, 123128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Amelung, W.; Lehmann, J.; Kästner, M. Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3578–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Meng, J.; Xu, E.G.; Chen, W. Microbial community structure and predicted bacterial metabolic functions in biochar pellets aged in soil after 34 months. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 100, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, T.; Liu, K.S.; Wang, L.X.; Wang, K.; Zhou, Y. Effects of different amendments for the reclamation of coastal saline soil on soil nutrient dynamics and electrical conductivity responses. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 159, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, T.; Chang, S.X.; Jiang, X.; Song, Y. Biochar increases soil microbial biomass but has variable effects on microbial diversity: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.Z.; Mo, F.; Han, J. Microbial life-history strategies and particulate organic carbon mediate formation of microbial necromass carbon and stabilization in response to biochar addition. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.Y.; Mazza Rodrigues, J.L.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Barceló, M.; Olsson, P.A.; Song, C.; Tedersoo, L.; Yuan, F.H.; Yuan, F.M.; Lipson, D.A.; et al. Global biogeography of fungal and bacterial biomass carbon in topsoil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; An, S.S.; Liang, C.; Liu, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial necromass as the source of soil organic carbon in global ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 108422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.