Application and Effect of Micropeptide miPEP164c on Flavonoid Pathways and Phenolic Profiles in Grapevine “Vinhão” Cultivar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vineyard Conditions, Treatment, and Sampling

2.2. Solubilization of miPEP164c

2.3. Anthocyanin Quantification

2.4. Proanthocyanidin Quantification

2.5. Total Phenolic Quantification

2.6. Protein Extraction

2.7. Enzymatic Activity Assays

2.8. Metabolomics Analysis of Specialized Metabolome by Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS)

2.9. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.10. Transcriptional Analyses by Real-Time qPCR

2.11. Statistical Analyses and Data Presentation

3. Results

Modulation of Specialized Metabolites Induced by miPEP164c Exogenous Application in Grape Berry Clusters—An UPLC-MS-Based Metabolomics Analysis

4. Discussion

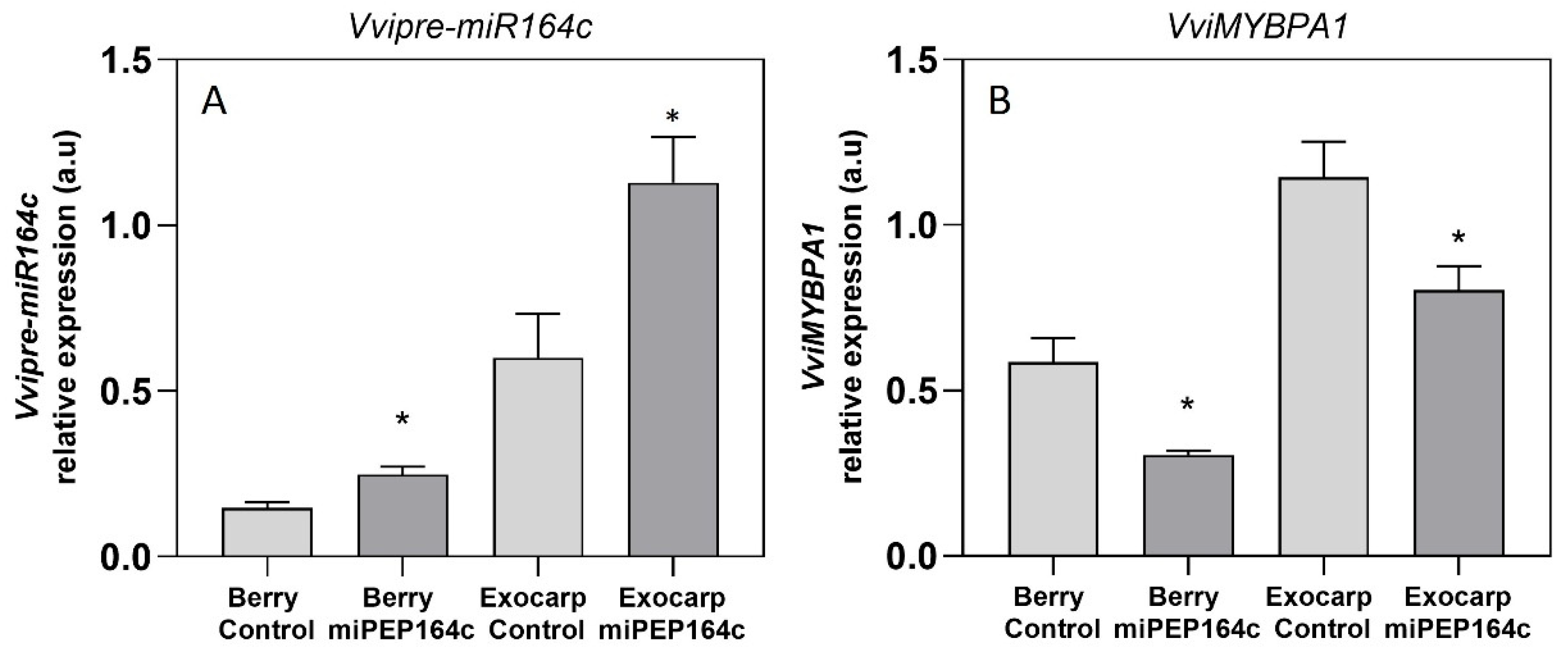

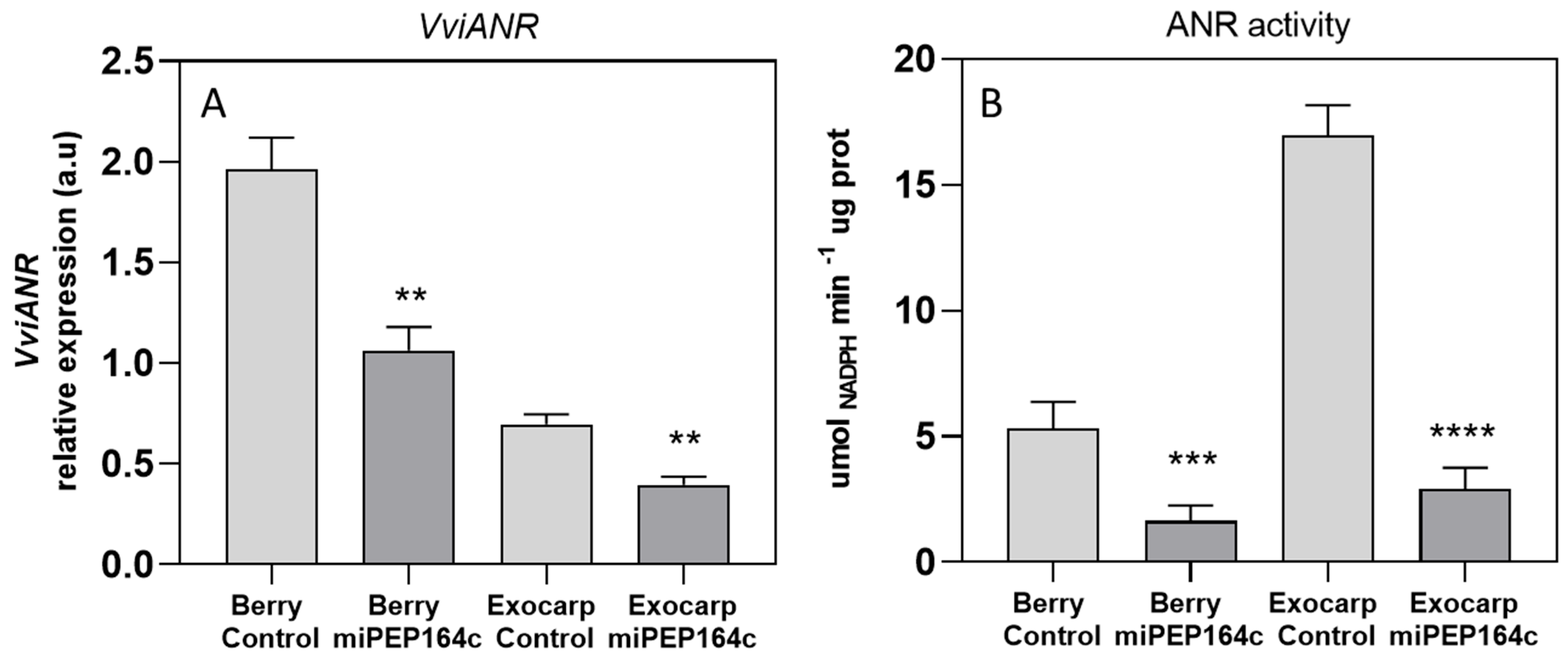

4.1. In Planta Application of miPEP164c on Grape Berries Enhances Pre-miR164c Expression, Leading to Reduced Proanthocyanidin Biosynthesis

4.2. miPEP164c Exogenous Application Modulates Other Flavonoid Compounds in Grape Berries

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cv. | cultivar |

References

- Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Runge, A.K.W.; Bouby, L.; Lacombe, T.; Samaniego Castruita, J.A.; Adam-Blondon, A.F.; Figueiral, I.; Hallavant, C.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Schaal, C.; et al. Palaeogenomic insights into the origins of French grapevine diversity. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Zarrouk, O.; Francisco, R.; Costa, J.M.; Santos, T.; Regalado, A.P.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Lopes, C.M. Grapevine under deficit irrigation: Hints from physiological and molecular data. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.; Eiras-Dias, J.; Castellarin, S.D.; Gerós, H. Berry phenolics of grapevine under challenging environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18711–18739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Eichmeier, A.; Mattii, G.B. Effects of Global Warming on Grapevine Berries Phenolic Compounds—A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montealegre, R.; Romero Peces, R.; Chacón Vozmediano, J.L.; Martínez Gascueña, J.; García Romero, E. Phenolic compounds in skins and seeds of ten grape Vitis vinifera varieties grown in a warm climate. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, M.; Rodrigues, J.; Badim, H.; Gerós, H.; Conde, A. Exogenous Application of Non-mature miRNA-Encoded miPEP164c Inhibits Proanthocyanidin Synthesis and Stimulates Anthocyanin Accumulation in Grape Berry Cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 706679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, H.A.; Elsayed, A.M.; Bassuiny, R.I.; Abdel-Aty, A.M.; Mohamed, S.A. Improvement of phenolic profile and biological activities of wild mustard sprouts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, A.; Machemer, K.; Braun, E.L.; Grotewold, E. Evolutionary and comparative analysis of MYB and bHLH plant transcription factors. Plant J. 2011, 66, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, H.; Sharma, A.; Trivedi, P.K. Plant microProteins and miPEPs: Small molecules with much bigger roles. Plant Sci. 2023, 326, 111519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.W. Subspecialization of R2R3-MYB repressors for anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin regulation in forage legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Lei, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z. R2R3-MYB Transcription Factors Regulate Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Grapevine Vegetative Tissues. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, E.; Matus, J.T.; Finezzo, L.; Zenoni, S.; Loyola, R.; Guzzo, F.; Schlechter, R.; Ageorges, A.; Arce-Johnson, P.; Tornielli, G.B. The Phenylpropanoid Pathway Is Controlled at Different Branches by a Set of R2R3-MYB C2 Repressors in Grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1448–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogs, J.; Jaffe, F.W.; Takos, A.M.; Walker, A.R.; Robinson, S.P. The Grapevine Transcription Factor VvMYBPA1 Regulates Proanthocyanidin Synthesis during Fruit Development. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1347–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauressergues, D.; Couzigou, J.M.; San Clemente, H.; Martinez, Y.; Dunand, C.; Bécard, G.; Combier, J.P. Primary transcripts of microRNAs encode regulatory peptides. Nature 2015, 520, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couzigou, J.M.; André, O.; Guillotin, B.; Alexandre, M.; Combier, J.P. Use of microRNA-encoded peptide miPEP172c to stimulate nodulation in soybean. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kamal Badola, P. miRNA-encoded peptide, miPEP858, regulates plant growth and development in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.J.; Deng, B.H.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.L.; Song, S.R.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.P.; Xu, W.P.; Zhang, C.X.; et al. A mirna-encoded small peptide, vvi-miPEP171d1, regulates adventitious root formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-J.; Zhang, L.-P.; Song, S.-R.; Wang, L.; Xu, W.-P.; Zhang, C.-X.; Wang, S.-P.; Liu, H.-F.; Ma, C. vvi-miPEP172b and vvi-miPEP3635b increase cold tolerance of grapevine by regulating the corresponding MIRNA genes. Plant Sci. 2022, 325, 111450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, A.; Badim, H.; Dinis, L.T.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Ferrier, M.; Unlubayir, M.; Lanoue, A.; Gerós, H. Stimulation of secondary metabolism in grape berry exocarps by a nature-based strategy of foliar application of polyols. Oeno One 2024, 58, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Rashmi, R.; Toppo, V.; Chole, P.B.; Banadka, A.; Sudheer, W.N.; Nagella, P.; Shehata, W.F.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Alessa, F.M.; et al. Plant Secondary Metabolites: The Weapons for Biotic Stress Management. Metabolites 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowański, S.; Adamski, Z.; Marciniak, P.; Rosiński, G.; Büyükgüzel, E.; Büyükgüzel, K.; Falabella, P.; Scrano, L.; Ventrella, E.; Lelario, F.; et al. A review of bioinsecticidal activity of Solanaceae alkaloids. Toxins 2016, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Evaluation of parameters that affect the 4-dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde assay for flavanols and proanthocyanidins. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C619–C625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badim, H.; Vale, M.; Coelho, M.; Granell, A.; Gerós, H.; Conde, A. Constitutive expression of VviNAC17 transcription factor significantly induces the synthesis of flavonoids and other phenolics in transgenic grape berry cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 964621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, C.E.; Lancaster, J.E.; Walker, J.R.L. Developmental changes in enzymes of flavonoid biosynthesis in the skins of red and green apple cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1996, 71, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, S.; Lacampagne, S.; Claisse, O.; Gény, L. Leucoanthocyanidin reductase and anthocyanidin reductase gene expression and activity in flowers, young berries and skins of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet-Sauvignon during development. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, K.; Zhao, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Gao, L.; Xia, T. Characterisation of anthocyanidin reductase from Shuchazao green tea. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.E.; Olsson, N.; Schlosser, J.; Peng, F.; Lund, S.T. An optimized grapevine RNA isolation procedure and statistical determination of reference genes for real-time RT-PCR during berry development. BMC Plant Biol. 2006, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-González, G.F.; Grosskopf, E.; Sadgrove, N.J.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Chemical Diversity of Flavan-3-Ols in Grape Seeds: Modulating Factors and Quality Requirements. Plants 2022, 11, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine polyphenol content and its influence on wine quality and properties: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estévez, I.; Pérez-Gregorio, R.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; De Freitas, V. Oenological perspective of red wine astringency. Oeno One 2017, 51, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, C.; González-Muñoz, B.; O’Brien, J.A.; Laurie, V.F.; Osorio, F.; Núñez, E.; Vega, R.E.; Bordeu, E.; Brossard, N. Red wine astringency: Correlations between chemical and sensory features. LWT 2022, 154, 112656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra, M.L.F.; Serra, P.; Casati, P. Recent advances on the roles of flavonoids as plant protective molecules after UV and high light exposure. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Ye, D.X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.L. Peptides, new tools for plant protection in eco-agriculture. Adv. Agrochem 2023, 2, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pržić, Z.; Simić, A.; Brajević, S.; Marković, N.; Vuković Vimić, A.; Vujadinović Mandić, M.; Niculescu, M. Grass Cover in Vineyards as a Multifunctional Solution for Sustainable Grape Growing: A Case Study of Cabernet Sauvignon Cultivation in Serbia. Agronomy 2025, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vale, M.; Lanoue, A.; Abdallah, C.; Gerós, H.; Conde, A. Application and Effect of Micropeptide miPEP164c on Flavonoid Pathways and Phenolic Profiles in Grapevine “Vinhão” Cultivar. Agronomy 2026, 16, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010097

Vale M, Lanoue A, Abdallah C, Gerós H, Conde A. Application and Effect of Micropeptide miPEP164c on Flavonoid Pathways and Phenolic Profiles in Grapevine “Vinhão” Cultivar. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleVale, Mariana, Arnaud Lanoue, Cécile Abdallah, Hernâni Gerós, and Artur Conde. 2026. "Application and Effect of Micropeptide miPEP164c on Flavonoid Pathways and Phenolic Profiles in Grapevine “Vinhão” Cultivar" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010097

APA StyleVale, M., Lanoue, A., Abdallah, C., Gerós, H., & Conde, A. (2026). Application and Effect of Micropeptide miPEP164c on Flavonoid Pathways and Phenolic Profiles in Grapevine “Vinhão” Cultivar. Agronomy, 16(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010097