Abstract

Understanding the dormancy behavior and germination requirements of Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Houtt.) J.H.Pak & Kawano, a valuable vascular plant native to Korea, is essential for establishing an efficient seed propagation protocol. In this study, we developed a propagation method by examining the effects of temperature, light, gibberellic acid (GA3), and cold stratification to determine whether the seeds possess non-deep physiological dormancy. The light and temperature experiment was conducted under a constant 4 °C and alternating temperature regimes of 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C (12 h day/12 h night). Seeds were incubated under either 12 h light/12 h dark or continuous darkness (24 h). GA3 treatment and cold stratification were conducted only at 15/6 °C or 25/15 °C under the 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod. All seed treatments were incubated for 8 weeks under their respective temperature conditions. To investigate the influence of GA3, seeds were soaked for 24 h in solutions of 0, 10, 100, or 1000 mg∙L−1 GA3 and then incubated. Cold stratification was tested by storing seeds at 4 °C for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks before incubation. Seeds germinated without additional embryo growth, and no physical dormancy due to seed coat impermeability was observed. No germination occurred at 4 °C. Under light conditions, final germination at 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C was 51.8 ± 1.2%, 28.3 ± 3.5%, and 30.8 ± 2.2%, respectively, while under dark conditions it was 37.0 ± 3.1%, 17.3 ± 2.4%, and 13.5 ± 8.5%, respectively. GA3 enhanced germination. Without GA3 treatment, final germination was 41.2% at 15/6 °C and 37.5% at 25/15 °C, whereas with GA3, final germination reached 100% under both temperatures, regardless of concentration. Cold stratification increased germination, improving both initial and final germination compared to the control. Notably, GA3 at 1000 mg·L−1 induced rapid and uniform germination under all temperatures, making it the most effective treatment for the propagation of C. denticulatum seeds, and supporting the conclusion that this species exhibits non-deep physiological dormancy.

1. Introduction

Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Houtt.) J.H.Pak & Kawano is a vascular plant belonging to the family Asteraceae, with stems reaching 30–70 cm in height, branching profusely, and often exhibiting a purple hue [1,2]. The Asteraceae family comprises more than 30,000 species and is distributed worldwide except in Antarctica [3]. Species diversity is particularly high in arid and semi-arid regions, where the family holds considerable economic value as a food resource [4]. C. denticulatum is widely distributed across Korea, as well as in Russia, Mongolia, Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. In Korea, it is known as a medicinal plant and typically inhabits shaded areas on mountain slopes and foothills [2,5]. In Korea, approximately 285 species of Asteraceae are native, and have traditionally been utilized for food and medicinal purposes [6,7]. C. denticulatum is widely distributed across mountainous regions and fields of Korea, along with related taxa such as Ixeridium dentatum (Thunb.) Tzvelev, Crepidiastrum sonchifolium (Bunge) Pak & Kawano, Lactuca indica L., and Taraxacum platycarpum Dahlst [8]. This species contains abundant hydroxycinnamic acids, including O-dicaffeoylquinic acid and chicoric acid, which exhibit hepatoprotective, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, and are known to contribute to the prevention of metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases [9]. In Korea, C. denticulatum is traditionally consumed as a vegetable and in fermented foods such as kimchi and has been reported to exhibit cancer chemopreventive and antioxidative activities. Similarly, Crepidiastrum lanceolatum exhibits antioxidant effects attributed to chicoric, chlorogenic, and caffeic acids [10]. Moreover, C. denticulatum possesses detoxifying and hepatoprotective activities against chronic alcohol-induced liver damage [11], and recent studies demonstrated that mixtures of fucoidan and C. denticulatum extract induce apoptosis in HepG2 liver cancer cells, underscoring its anticancer potential and functional value [12]. Owing to the plant’s outstanding potential as a horticultural and functional species, recent investigations have aimed to optimize its cultivation and enhance the biosynthesis of functional compounds within plant factories utilizing artificial lighting (PFALs) [5,9].

The efficiency of seed propagation is closely related to the state of seed dormancy, and understanding dormancy is essential for achieving uniform germination and stable cultivation. However, studies on seed dormancy and germination characteristics of C. denticulatum are extremely limited, and little is known about its physiological mechanisms. Therefore, fundamental research on dormancy release and germination requirements is necessary to establish an efficient propagation system for this species. Seed-based propagation offers advantages in maintaining genetic diversity and enabling large-scale multiplication [13,14], while studies on germination physiology can provide valuable insights to improve productivity and promote the practical utilization of this functional plant resource. Seed dormancy is an intrinsic trait that regulates the timing and conditions of seed germination, enabling plants to synchronize seedling emergence with favorable environmental factors such as temperature, moisture, and light [15,16,17,18]. Dormancy serves as an adaptive mechanism that restricts germination to specific cues, thereby ensuring successful establishment across diverse habitats. It is generally classified into five types: physiological dormancy (PD), caused by physiological inhibition within the embryo; morphological dormancy (MD), in which the embryo is underdeveloped; morphophysiological dormancy (MPD), combining MD and PD; physical dormancy (PY), caused by water-impermeable seed coats; and combinational dormancy (PY + PD), in which both PY and PD occur [19]. Among these, PD accounts for approximately 50–75% of dormant species worldwide [20], representing a major mechanism controlling germination timing.

PD is classified into three levels, non-deep, intermediate, and deep, according to the strength of physiological inhibition within the embryo [20]. Among these levels, non-deep physiological dormancy represents the weakest form, as it can be released by relatively short periods of cold or warm stratification, dry after-ripening, or the application of gibberellic acid (GA3). This classification reflects differences in the depth of physiological inhibition that characterize the three levels of PD [19].

In Asteraceae, seeds at maturity are either nondormant or exhibit non-deep PD, and the relative frequency of these two states varies among vegetation zones worldwide [3]. However, the seed dormancy type of C. denticulatum has not yet been clearly identified, and studies on its dormancy-breaking requirements remain scarce. Understanding its dormancy and germination physiology is therefore crucial for establishing an effective propagation strategy and for promoting the practical utilization of this species.

Germination parameters, including germination onset, capacity, and rate, are strongly influenced by major environmental factors such as temperature, light, and soil moisture, and the interactions between these factors and seed dormancy are critical determinants of germination success [21]. Most species in the Asteraceae family possess non-deep PD and often regulate germination timing in natural habitats through an annual dormancy–non-dormancy cycle in response to seasonal temperature fluctuations. Dormancy can also be released by cold stratification, warm stratification, or dry after-ripening, depending on environmental conditions [3]. In practice, dormancy release and improved germination have been reported in various Asteraceae species in response to temperature and plant growth regulator (PGR) treatments. Seeds of Arnica mollis Hook., Crepis acuminata Nutt., Erigeron pumilus Nutt., and Chaenactis douglasii (Hook.) Hook. & Arn. possess non-deep PD, which was most effectively broken by cold stratification. In addition, A. mollis and C. acuminata showed enhanced germination following GA3 treatment, and dry after-ripening partially released dormancy in A. mollis, C. acuminata, and E. pumilus [22]. Picris willkommii seeds exhibit PD, as indicated by their positive response to GA3 treatment [23]. Moreover, Helianthus maximiliani, Verbesina virginica, and Viguiera dentata possess conditional physiological dormancy (PD), and their germination was enhanced following cold stratification [24]. Crepis acuminata and Erigeron pumilus possess conditional physiological dormancy (PD), with germination increasing to over 70–90% following about three months of cold stratification. Moreover, exogenous GA3 application elicited a dormancy-breaking effect comparable to that achieved by two months of cold stratification [22]. Similarly, the two endemic species Rhaponticum bicknellii and R. scariosum from the Italian Alps exhibited contrasting germination responses [25]. R. bicknellii showed a significant increase in germination rates with longer periods of cold stratification, suggesting that it possesses a form of non-deep physiological dormancy. In contrast, R. scariosum responded minimally even after 90 days of cold stratification, and germination was promoted only under warm temperature conditions. Currently, research on the seed dormancy type and germination-promoting techniques of C. denticulatum remains limited. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the dormancy type of C. denticulatum through various germination-promoting treatments, including GA3 application and cold stratification, and to provide basic data for establishing an efficient propagation system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Collection and Basic Characteristics

Seeds (achenes) of C. denticulatum were obtained from the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), South Korea. These seeds had been originally collected by NIBR from Taebaek, Gangwon Province, on 5 November 2022 (accession no. NIBRGR0000666444). The seeds were stored at 0 °C with silica gel until use. Seed length and width were measured using a vernier caliper (150 mm Digital Caliper; generic, Shenzhen, China) with 10 replications. The 100-seed weight (mg) was determined with five replications using an electronic balance (Ohaus, PAG214, Parsippany, NJ, USA). For internal structure observation, seeds were sectioned using a razor blade (Dorco, Seoul, Republic of Korea), and the internal and external lengths were measured under a USB digital microscope (AM3111 Dino-Lite Premier, AnMo Electronics Co., Taipei, Taiwan).

2.2. Water Imbibition Test

To evaluate the water uptake ability of seeds, an imbibition test was conducted. Seeds were placed in Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm, diameter × height) filled with distilled water, ensuring that the seeds were completely immersed. Seed weight was recorded at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after immersion. Each treatment consisted of 20 seeds and was replicated four times. Water imbibition percentage (Ws %) was calculated according to the following formula: Ws (%) = (Wh − Wi)/Wi × 100, where Wh is the seed weight after a given imbibition period, and Wi is the initial seed weight.

2.3. Seed Sterilization and Incubation

All experiments in this study were conducted using 20 seeds with four replications. This was because C. denticulatum is a wild Asteraceae species and the number of seeds obtainable from a single collection was limited. Similar numbers of seeds and replications have been used in ecological and physiological germination studies of wild plant species, and there are several reports in which 20–25 seeds with 4–5 replications were employed to evaluate germination characteristics [21,22,25]. For laboratory experiments, seeds were first rinsed with distilled water and then surface-sterilized by shaking in a benomyl solution (1000 mg·L−1) for 24 h. The sterilized seeds were rinsed again with distilled water and incubated in Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm, diameter × height) lined with two layers of filter paper moistened with distilled water. To prevent moisture loss, all Petri dishes were sealed with parafilm. Incubation at a constant temperature of 4 °C was carried out in a cold-lab chamber (HB-603CM, HANBAEK Scientific, Bucheon, Republic of Korea), while alternating temperature regimes (15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C) were maintained in a multi-room chamber (HB-302S-4, HANBAEK Scientific, Bucheon, Republic of Korea). All chambers were set to a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod, with a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 22–30 μmol·m−2·s−1 under light conditions. Germination, defined as the emergence of a radicle at least 1 mm in length, was recorded once a week for 8 weeks. The final germination percentage was calculated at the end of this 8-week incubation period.

2.4. Light and Temperature Conditions

For the light and temperature treatments, seeds were incubated under light and dark conditions combined with four temperature regimes: 4 °C, and alternating day/night temperatures of 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C. These temperature regimes were selected to approximate typical winter (4 °C), early-spring/late-autumn (15/6 °C), late-spring/early-autumn (20/10 °C), and summer (25/15 °C) soil temperatures in Korea. Furthermore, these temperature conditions were devised based on seasonal temperature variations in North America, which has a latitude similar to the location where we conducted our experiment, and are temperature conditions that have already been applied in many seed ecology experiments [26]. Under light conditions, Petri dishes were incubated under a 12/12 h (light/dark) photoperiod with a PPFD of 22–30 μmol·m−2·s−1. For the dark treatment, Petri dishes were wrapped with aluminum foil and maintained in continuous darkness (24 h). Incubation at a constant temperature of 4 °C was carried out in a cold-lab chamber (HB-603CM, HANBAEK Scientific, Bucheon, Republic of Korea). Alternating temperature regimes (15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C) were maintained in a multi-room chamber (HB-302S-4, HANBAEK Scientific, Bucheon, Republic of Korea), with the higher temperature applied for 12 h during the day and the lower temperature for 12 h during the night. For the light treatment, a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod was used, simply dividing the 24 h day into equal light and dark periods so that daytime was represented by light and night-time by darkness.

2.5. GA3 Treatment

To examine the effects of GA3 on dormancy and germination, seeds were soaked at room temperature (22–25 °C) for 24 h in GA solutions (MBcell, Cat. No.: MB-G5512, KisanBio, Seoul, Republic of Korea) at concentrations of 0 (distilled water), 10, 100, or 1000 mg·L−1. After treatment, seeds were disinfected by soaking in a benomyl solution (FarmHannong, Seoul, Republic of Korea) at 1000 mg·L−1 for 4 h and subsequently sown on Petri dishes. Because GA3 uptake is inhibited when seeds are pre-moistened, GA3 immersion was performed prior to benomyl treatment, and the benomyl immersion time was shortened to avoid excessive soaking. The dishes were incubated in multi-room chambers (HB-302S-4, HANBAEK Scientific, Bucheon, Republic of Korea) under alternating temperature regimes of 15/6 and 25/15 °C.

2.6. Cold Stratification

To evaluate the effects of cold stratification on dormancy release and germination, seeds were stratified for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks. For cold stratification, seeds were placed in Petri dishes prepared as described above for the germination tests and kept at 4 °C in a cold-lab chamber (HB-603CM, HANBAEK Scientific, Bucheon, Republic of Korea) for the respective stratification periods. After stratification, the seeds were transferred to alternating temperature regimes of 15/6 and 25/15 °C for germination tests.

2.7. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Final germination percentage (GP, %) was calculated using the formula GP (%) = (N/S) × 100, where N is the number of germinated seeds and S is the total number of seeds tested. Mean germination time (MGT, day) was calculated using the formula MGT = ∑(D × n)/N, where D is the day of scoring, n is the number of seeds germinated on that day, and N is the total number of germinated seeds. The results for each treatment were presented graphically using SigmaPlot 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of variance was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and statistical significance among treatment means was tested using Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Seed Collection and Basic Characteristics

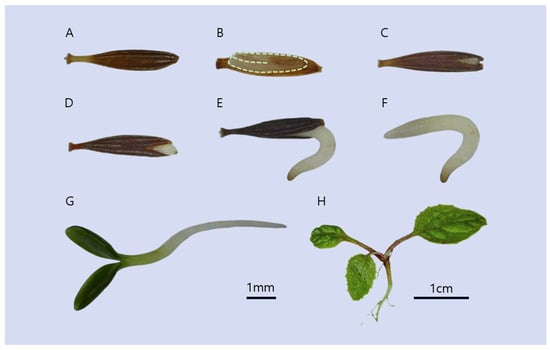

Seeds of C. denticulatum are achenes, with an average length of 5.74 ± 0.12 mm, a width of 0.435 ± 0.10 mm, and a 100-seed weight of 1251.58 ± 3.80 mg (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stages of C. denticulatum seed germination and seedling development. (A) intact seed; (B) internal structure of a seed at dispersal; (C) seed coat splitting; (D,E) germinating seeds; (F) a germinated seed after seed coat removal; (G) a seedling with cotyledons; (H) a young plant with true leaves. Scale bars: 1 mm (A–G), 1 cm (H).

3.2. Water Imbibition Test

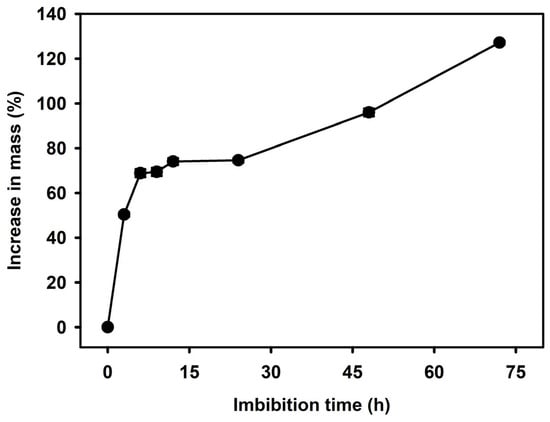

In the water imbibition test, seeds absorbed approximately 50% of water within the first 3 h and reached about 75% after 12 h. Ultimately, water uptake increased to approximately 127% after 72 h, indicating that the seeds efficiently absorbed water (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Water uptake (%) of C. denticulatum seeds during 72 h of imbibition. Seeds were immersed in distilled water. Error bars indicate mean ± SE (n = 4).

3.3. Light and Temperature Conditions

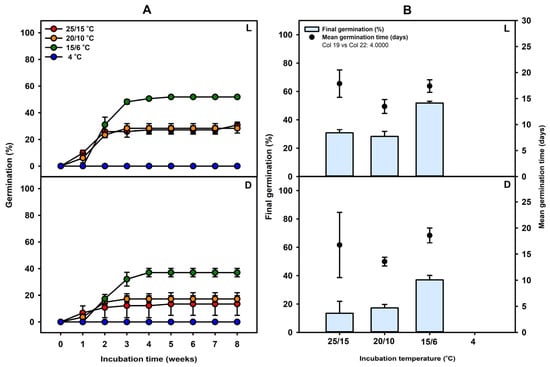

Seeds did not germinate under either light or dark conditions at 4 °C throughout the 8-week incubation period (Figure 3). Final germination percentages under light conditions were 51.84 ± 1.19, 28.33 ± 3.53, and 30.83 ± 2.20% at 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C, respectively. Under dark conditions, germination percentages were lower, with 37.02 ± 3.13, 17.26 ± 2.43, and 13.47 ± 8.47% at 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C, respectively (Figure 3). Across both light and dark conditions, germination at 15/6 °C was significantly higher than at the other temperature treatments. Overall, C. denticulatum seeds exhibited the highest germination percentage at a relatively low temperature of 15/6 °C. Mean germination time (MGT) appeared to be shortest at 20/10 °C, with values of 13.48 ± 1.33 days under light and 13.56 ± 0.84 days under dark conditions. However, the differences in MGT among temperature treatments were not statistically significant, as indicated by overlapping error bars. Moreover, germination percentages at 20/10 °C were significantly lower than those at 15/6 °C. Therefore, although 20/10 °C may show a trend toward slightly faster germination, 15/6 °C remains the most favorable temperature condition overall due to its substantially higher germination success.

Figure 3.

(A) Germination percentage of C. denticulatum seeds incubated at 25/15, 20/10, 15/6, and 4 °C under light (L) or dark (D) conditions. (B) Final germination percentage and mean germination time of C. denticulatum seeds incubated at 25/15, 20/10, 15/6, and 4 °C under light (L) or dark (D) conditions. No germination was observed in seeds incubated at 4 °C; consequently, the mean germination time could not be determined. Error bars indicate mean ± SE (n = 4).

3.4. GA3 Treatment

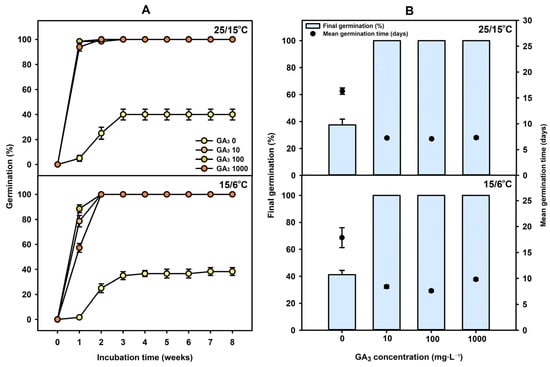

Seeds were treated with GA3 solutions at concentrations of 0, 10, 100, or 1000 mg·L−1 and incubated at 25/15 °C and 15/6 °C. At 25/15 °C, germination percentages after 1 week were 3.75 ± 2.39, 97.55 ± 1.40, 98.86 ± 1.13, and 95.45 ± 3.21%, respectively, with final germination percentages of 37.50 ± 4.33, 100, 100, and 100%. At 15/6 °C, germination percentages after 1 week were 1.25 ± 1.25, 79.97 ± 4.53, 91.36 ± 3.13, and 59.64 ± 3.50%, respectively, with final germination percentages of 41.25 ± 3.14, 100, 100, and 100%. These final germination percentages were obtained after only approximately 2–3 weeks of incubation under the two temperature regimes (15/6 °C and 25/15 °C). Under both temperature regimes, the GA3 treatments showed significantly higher germination percentages than the control. Thus, GA3 treatment markedly enhanced both initial and final germination percentages compared with the control (Figure 4). The mean germination time (MGT) was significantly reduced by GA3 treatment under both 25/15 °C and 15/6 °C conditions. At 25/15 °C, the control showed the longest MGT of 16.30 ± 0.62 days, whereas GA3 treatment markedly shortened the MGT to 7.08 ± 0.08–7.32 ± 0.22 days, with the lowest value observed at 100 mg·L−1. Similarly, under 15/6 °C conditions, the MGT of the control (17.85 ± 1.92 days) was greatly reduced to 7.60 ± 0.22 days with 100 mg·L−1 GA3 treatment, indicating that GA3 effectively enhanced the germination rate even under relatively low-temperature conditions.

Figure 4.

(A) Germination percentage of C. denticulatum seeds treated with GA3 (0, 10, 100, or 1000 mg·L−1) and incubated at 15/6 and 25/15 °C. (B) Final germination percentage and mean germination time of C. denticulatum seeds treated with different GA3 concentrations (0, 10, 100, or 1000 mg·L−1) under 25/15 °C and 15/6 °C conditions. Error bars indicate mean ± SE (n = 4).

3.5. Cold Stratification

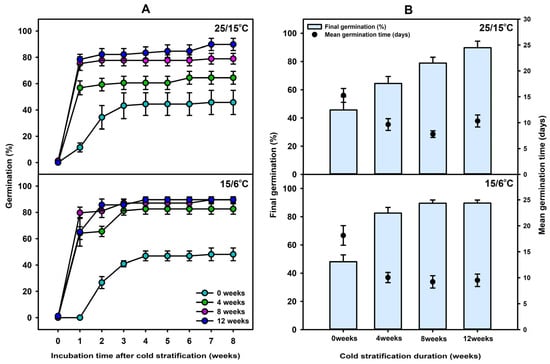

Seeds were subjected to cold stratification for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks and then incubated at 25/15 °C and 15/6 °C. At 25/15 °C, germination percentages after 1 week were 11.51 ± 3.39, 56.80 ± 5.27, 75.22 ± 5.18, and 78.42 ± 3.87%, respectively, with final germination percentages of 45.72 ± 9.19, 64.44 ± 4.89, 78.91 ± 4.07, and 89.80 ± 4.64%, respectively. At 15/6 °C, germination percentages after 1 week were 0, 64.22 ± 4.84, 79.69 ± 4.28, and 65.22 ± 10.89%, respectively, with final germination percentages of 48.09 ± 4.86, 82.60 ± 3.97, 89.59 ± 2.25, and 89.67 ± 2.10%, respectively. At both temperature regimes, cold stratification for 4 weeks or longer resulted in significantly higher germination percentages than the control. Overall, cold stratification markedly enhanced both initial and final germination percentages compared with the control (Figure 5). Mean germination time (MGT) decreased with increasing cold stratification duration, indicating a cumulative effect of stratification on germination speed. At 25/15 °C, the MGT of the control was the longest at 15.27 ± 1.34 days, while the shortest MGT of 7.79 ± 0.65 days was observed with 8 weeks of stratification. Similarly, at 15/6 °C, the control showed an MGT of 18.14 ± 1.89 days, which was reduced to 9.20 ± 1.19 days after 8 weeks of stratification.

Figure 5.

(A) Germination percentage of C. denticulatum seeds after cold stratification at 4 °C for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks, followed by incubation at 15/6 and 25/15 °C. (B) Final germination percentage and mean germination time of C. denticulatum seeds after cold stratification for 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks, incubated at 25/15 °C and 15/6 °C. Error bars indicate mean ± SE (n = 4).

4. Discussion

In this study, Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Houtt.) J.H.Pak & Kawano seeds exhibited normal water uptake (Figure 2). In general, seeds with PY possess seed coats or pericarps that impede water absorption [26]; thus, the present results indicate that C. denticulatum does not exhibit PY characteristics. In addition, the seeds of C. denticulatum contained fully developed embryos at the time of dispersal (Figure 1). MD seeds typically possess underdeveloped or undifferentiated embryos, which may germinate without pretreatment or after only dry storage as the embryo continues to grow [27,28]. However, C. denticulatum did not display these features (Figure 1), suggesting that its seeds do not belong to the MD or MPD types.

Baskin and Baskin [29] classified seeds as having PD when they possess fully developed embryos at dispersal but exhibit delayed germination of more than 30 days. In the present study, C. denticulatum seeds treated with GA3 achieved 100% final germination under both temperature regimes (15/6 and 25/15 °C). In contrast, seeds in the control group exhibited delayed germination, with final germination percentages ranging from 37.50% to 41.25%. PD is characterized by metabolic requirements that have not yet been met, making germination difficult even under otherwise favorable environmental conditions [30], and inhibiting embryo growth and seed germination until specific chemical changes occur [31]. Therefore, the seeds of C. denticulatum are likely to possess PD. This type of dormancy can be broken by treatments such as warm and/or cold stratification, GA application, or dry storage [31,32]. Hormonal treatments break dormancy by shifting the hormonal balance toward embryo growth, whereas temperature stratification provides environmental cues conducive to germination. PD is further classified into three levels of depth: non-deep, intermediate, and deep [20]. Non-deep PD can be broken by relatively short periods of cold stratification, dry after-ripening, or treatment with GA3. Intermediate PD is generally broken by 12–16 weeks of moist-cold stratification or by a sequence of warm and cold stratification (warm + cold stratification). In species with intermediate PD, a preceding warm stratification period can greatly reduce the length of cold stratification required for dormancy break. In particular, in temperate species with intermediate PD, a preceding warm period can reduce the cold stratification requirement for dormancy break to about 8–10 weeks. In contrast, deep PD requires a prolonged period of cold stratification of 12 to 24 weeks, and GA3 treatment alone is generally ineffective in breaking dormancy [19,33,34,35].

Based on the results of this study, C. denticulatum seeds exhibited suppressed germination at 4 °C, while the highest germination rate was observed under 15/6 °C conditions. The four temperature regimes (4, 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C) in this study were selected to represent seasonal temperature conditions in Korea and are similar to those used in previous studies on seed dormancy and germination [26,36]. In this study, 4 °C was used to approximate winter conditions, 15/6 °C early-spring and late-autumn conditions, 20/10 °C late-spring and early-autumn conditions, and 25/15 °C summer conditions. The study site, Andong, is located at a latitude similar to that of Kentucky, USA, where Baskin and Baskin [26] proposed a seasonal temperature regime using 5, 15/6, 20/10, and 25/15 °C in a “move-along” experiment. In the present study, we applied a similar framework, adjusting the winter temperature to 4 °C. Therefore, the germination patterns observed in our experiments can be interpreted as responses to realistic seasonal temperature conditions in the species’ natural habitat. Conditional dormancy (CD) is a transitional state in which seeds germinate only within a restricted range of environmental conditions, representing an intermediate stage between full dormancy and non-dormancy [37]. The light- and temperature-dependent germination pattern observed in C. denticulatum therefore fits within the framework of non-deep PD. Germination markedly increased at both 15/6 °C and 25/15 °C following cold stratification or GA3 treatment (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Although seeds germinated more poorly at 25/15 °C than at 15/6 °C in the temperature experiment (Figure 3), these treatments raised germination at 25/15 °C to above 90%. This indicates that the temperature range at which the seeds can germinate has been broadened.

Furthermore, the higher germination percentage under light than in darkness indicates that C. denticulatum is positively photoblastic and responsive to light and temperature cues. Similar light-requiring germination behavior has been reported in the related species C. grandicollum (Koidz.) Nakai, in which germination required 1–2 months at 20–25 °C [38], and in C. denticulatum itself, which showed approximately 40% germination under light but only 20% under dark conditions when incubated at 15 °C for 16 days [39]. Likewise, several Asteraceae species, including Podolepis canescens [40] and Waifzia suaveolens var. flava [41], exhibit very high germination percentages (80–100%) under light conditions, whereas germination in darkness is markedly low. These patterns are consistent with the results of the present study and suggest that light and temperature act as key environmental signals regulating the transition from dormancy to germination in this species. Light plays an important role in inhibiting or promoting seed germination [21], and seeds are capable of efficiently sensing environmental changes to adjust their germination responses accordingly [42]. Temperature is also a critical factor regulating seed dormancy and germination, directly influencing not only germination success but also seedling establishment and subsequent crop growth [43,44].

Both GA3 treatment and cold stratification significantly enhanced the germination of C. denticulatum seeds. GA3 treatment increased germination by more than 60% compared with the control under both temperature regimes and also reduced the mean time to germination (Figure 4). Similarly, cold stratification increased germination percentage and accelerated germination as the duration of stratification increased (Figure 5). These results demonstrate that GA3 treatment and cold stratification are effective in improving germination and reducing germination time, supporting the conclusion that C. denticulatum seeds exhibit non-deep PD. Although small differences in early germination speed were observed among GA3 concentrations, these differences were not consistent across temperature treatments, and all concentrations above 10 mg·L−1 resulted in the same final germination percentage of 100%. Therefore, using higher concentrations does not provide additional benefits while substantially increasing the amount of GA3 required, making 10 mg·L−1 the most practical and cost-effective option for cultivation and propagation.

GA3 and/or cold stratification have also been reported to break seed dormancy in other Korean native species. In Campanula takesimana Nakai, the germination percentage varied greatly depending on GA3 concentration. Seeds treated with 1000 mg·L−1 GA3 showed the highest germination rates, reaching 57.0 ± 1.91% at 15/6 °C and 94.0 ± 1.15% at 25/15 °C, and the mean germination time (MGT) also decreased, indicating faster germination compared with other treatments [45]. Lychnis wilfordii (Regel) Maxim seeds exhibited very low germination without any pretreatment. However, germination was markedly enhanced by 1000 mg·L−1 GA3 treatment, resulting in 56.3% germination at 15/6 °C and 73.2% at 25/15 °C. Furthermore, germination increased with the duration of cold stratification, reaching 77.0% under light and 58.4% under dark conditions after 6 weeks, and 83.3% and 83.1% under light and dark conditions, respectively, after 9 weeks [46]. In addition, the germination of Scutellaria indica L. var. coccinea S.T.Kim & S.T.Lee was markedly enhanced by increasing both the duration of cold stratification and the concentration of GA3. Germination reached approximately 90% after 8–12 weeks of cold stratification, and 97.4% and 100.0% at GA3 concentrations of 100 and 1000 mg·L−1, respectively, indicating that these treatments are effective in promoting germination [36].

CD refers to a state in which seeds can germinate only under a limited range of environmental conditions initially, but after dormancy-breaking processes, they become capable of germinating over a wider temperature range [47]. This reflects the characteristic that germination is possible under certain conditions but inhibited under others [21]. In this study, C. denticulatum seeds exhibited CD in part of the seed population, and dormancy was released by a relatively short period of cold stratification or GA3 treatment. This pattern is similar to the germination behavior of non-deep PD reported in several Asteraceae species, including Echinops gmelinii, Epilasia acrolasia, Koelpinia linearis, and Bidens pilosa [48,49]. Taken together, these findings provide strong evidence that C. denticulatum seeds possess non-deep PD. Dormancy was fully released after only 4 to 8 weeks of cold stratification, which is substantially shorter than the periods required for intermediate or deep PD. In addition, germination was markedly enhanced by GA3, which is characteristic of non-deep PD but not of deeper dormancy levels. Warm and cold sequential stratification was also not required. This suggests that germination can be induced by relatively simple treatments and provides important baseline information for future studies on resource utilization and cultivation of this species. Overall, these characteristics are consistent with the established criteria that distinguish non-deep PD from intermediate and deep forms.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that C. denticulatum seeds exhibit non-deep PD that can be effectively overcome by either GA3 treatment or cold stratification. Both treatments markedly improved germination, confirming that dormancy can be released by relatively simple and practical methods. GA3 treatment significantly enhanced germination, and no significant differences in the final germination percentage were observed among concentrations above 10 mg·L−1. Although 100 mg·L−1 GA3 produced the shortest mean germination time, the improvement relative to 10 mg·L−1 was modest. Considering this marginal difference, together with cost-effectiveness and practical applicability, GA3 at 10 mg·L−1 can be regarded as the most suitable concentration for large-scale propagation. Short periods (4–8 weeks) of cold stratification also broke dormancy, providing an alternative treatment where the use of GA3 is limited or undesirable. Because C. denticulatum is widely recognized as an important edible and medicinal plant in Korea, establishing an efficient seed-based propagation protocol provides a scientific foundation for its stable conservation and large-scale production. Overall, this study contributes not only to the physiological understanding of seed dormancy and dormancy-breaking requirements in Asteraceae species but also to the sustainable utilization of C. denticulatum as a functional food and pharmaceutical resource.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.B., Y.J.L., G.-H.N., J.-W.K. and S.Y.L.; Investigation and Formal analysis, J.J.B. and S.Y.L.; Resources, Y.J.L. and G.-H.N.; Data curation, J.J.B.; Funding acquisition, Y.J.L., G.-H.N., J.-W.K. and S.Y.L.; Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, J.-W.K. and S.Y.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.J.B. and S.Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, Y.J.L., G.-H.N., J.-W.K. and S.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), funded by the Ministry of Environment (MOE) of the Republic of Korea (NIBR202414201, NIBR202513201).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all members of the Floriculture and Landscape Plants Lab (FLPL), Gyeongkuk National University, for their kind support and cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Korea National Arboretum. Nature: Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Houtt.) J.H.Pak & Kawano. Available online: https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?docId=3541468&cid=46694&categoryId=46694 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- National Institute of Biological Resources. Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Houtt.) J.H.Pak & Kawano. Available online: https://species.nibr.go.kr/home/mainHome.do?cont_link=009&subMenu=009002&contCd=009002&pageMode=view&ktsn=120000063851 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seed dormancy in Asteraceae: A global vegetation zone and taxonomic/phylogenetic assessment. Seed Sci. Res. 2023, 33, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doilom, M.; Hyde, K.D.; Dong, W.; Liao, C.F.; Suwannarach, N.; Lumyong, S. The plant family Asteraceae is a cache for novel fungal diversity: Novel species and genera with remarkable ascospores in Leptosphaeriaceae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 660261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Oh, M.M. Enhancement of Crepidiastrum denticulatum production using supplemental far-red radiation under various white LED lights. J. Bio-Environ. Control 2021, 30, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B. The plants of the Asteraceae family as agents in the protection of human health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, M.H.; Jung, Y.H.; Park, C.H.; Lee, H.H.; Na, C.S. Antioxidant activity of Asteraceae plant seed extracts. J. Life Sci. 2021, 31, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, H.K. Hepatotoxicity reducing effect of ethanol extracts from fermented Youngia denticulata Houtt. Kitamura in ethanol-treated rats. J. East Asian Soc. Diet. Life 2016, 26, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Bae, J.H.; Oh, M.M. Manipulating light quality to promote shoot growth and bioactive compound biosynthesis of Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Houtt.) Pak & Kawano cultivated in plant factories. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2020, 16, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Cha, K.H.; Kim, C.Y.; Nho, C.W.; Pan, C.H. Bioavailability of hydroxycinnamic acids from Crepidiastrum denticulatum using simulated digestion and Caco-2 intestinal cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5290–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.H.; Kang, K.; Yun, J.H.; Kim, M.A.; Nho, C.W. Crepidiastrum denticulatum extract protects the liver against chronic alcohol-induced damage and fat accumulation in rats. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Choi, D.; Oh, K.N.; Kim, H.; Park, H.; Kim, K.M. Induction of apoptosis using the mixture of fucoidan and Crepidiastrum denticulatum extract in HepG2 liver cancer cells. Food Sci. Preserv. 2024, 31, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladouceur, E.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B.; Marin, M.; De Vitis, M.; Abbandonato, H.; Iannetta, P.P.; Pritchard, H.W. Native seed supply and the restoration species pool. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrady, M.; Lampei, C.; Bossdorf, O.; Hölzel, N.; Michalski, S.; Durka, W.; Bucharova, A. Plants cultivated for ecosystem restoration can evolve toward a domestication syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219664120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, C.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, K.S.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, K.C. Dormancy and seed germination in the endemic Korean plant Ligustrum foliosum Nakai. Flower Res. J. 2017, 25, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.G.; Im, J.H.; Kwak, M.J.; Park, C.H.; Lee, M.H.; Na, C.S.; Woo, S.Y. Non-deep physiological dormancy in seed and germination requirements of Lysimachia coreana Nakai. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonogaki, H. Seed germination and dormancy: The classic story, new puzzles, and evolution. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 61, 541–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, S. Seed Dormancy and Germination. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R874–R878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. A classification system for seed dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carruggio, F.; Onofri, A.; Catara, S.; Impelluso, C.; Castrogiovanni, M.; Lo Cascio, P.; Cristaudo, A. Conditional seed dormancy helps Silene hicesiae Brullo & Signor. overcome stressful Mediterranean summer conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildisheva, O.A.; Erickson, T.E.; Kramer, A.T.; Zeldin, J.; Merritt, D.J. Optimizing physiological dormancy break of understudied cold desert perennials to improve seed-based restoration. J. Arid Environ. 2019, 170, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Tapias, R. Seed dormancy and seedling ecophysiology reveal the ecological amplitude of the threatened endemism Picris willkommii (Schultz Bip.) Nyman (Asteraceae). Plants 2022, 11, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M.; Van Auken, O.W. Role of Temperature in Dormancy Break and/or Germination of Autumn-maturing Achenes of Eight Perennial Asteraceae from Texas, U.S.A. Plant Species Biol. 1998, 13, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasso, V.; Mucciarelli, M.; Dovana, F.; Müller, J.V. Comparative germination ecology of two endemic Rhaponticum species (Asteraceae) in different climatic zones of the Ligurian and Maritime Alps (Piedmont, Italy). Plants 2020, 9, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. When breaking seed dormancy is a problem: Try a move-along experiment. Nativ. Plants J. 2003, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Bu, Z.J.; Poschlod, P.; Yusup, S.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zhang, Z.X. Seed dormancy types and germination response of 15 plant species in temperate montane peatlands. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nautiyal, P.C.; Sivasubramaniam, K.; Dadlani, M. Seed dormancy and regulation of germination. Seed Sci. Technol. 2023, 52, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 1st ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, B.B.; Pausas, J.G. Seed dormancy revisited: Dormancy-release pathways and environmental interactions. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.S.A.; Attanda, M.L. Factors that cause seed dormancy. In Seed Biology Updates; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Shin, U.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, M.J. Non-deep physiological dormancy in seeds of Euphorbia jolkinii Boiss. native to Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 45, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva, M.G. Physiology of Deep Dormancy in Seeds; Shapiro, Z., Translator; Nauka: Leningrad, Russia; National Science Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Mimicking the natural thermal environments experienced by seeds to break physiological dormancy to enhance seed testing and seedling production. Seed Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Park, K.; Jang, B.K.; Ji, B.; Lee, H.; Baskin, C.C.; Cho, J.S. Exogenous gibberellin can effectively and rapidly break intermediate physiological dormancy of Amsonia elliptica seeds. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1043897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kwon, H.C.; Lee, S.Y. Seed dormancy and germination characteristics of Scutellaria indica L. var. coccinea S.T. Kim & S.T. Lee, an endemic species found on Jeju Island, South Korea. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, K.; Soltani, E.; Arabhosseini, A.; Aghili Lakeh, M. A quantitative analysis of primary dormancy and dormancy changes during burial in seeds of Brassica napus. Nord. J. Bot. 2021, 39, e03281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, N.; Yamanaka, M.; Yasue, N. Crepidiastrum grandicollum (Koidz.) Nakai: Compositae: Plants in peril 42. Curtis’s Bot. Mag. 2024, 41, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.T.; Choi, B.K.; Moon, Y.G.; Kim, S.W.; Park, K.D.; Kwon, S.B. Effect of light conditions and wet cold treatments on seed germination in several wild vegetables. J. Agric. Life Environ. Sci. 2018, 30, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, D.J.; Kristiansen, M.; Flematti, G.R.; Turner, S.R.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Trengove, R.D.; Dixon, K.W. Effects of a butenolide present in smoke on light-mediated germination of Australian Asteraceae. Seed Sci. Res. 2006, 16, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, J.; Bell, D. The effect of temperature, light and gibberellic acid (GA3) on the germination of Australian everlasting daisies (Asteraceae, tribe Inuleae). Aust. J. Bot. 1995, 43, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klupczyńska, E.A.; Pawłowski, T.A. Regulation of seed dormancy and germination mechanisms in a changing environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, A.; Sawada, Y. Effects of temperature on seed dormancy and germination of the coastal dune plant Viola grayi: Germination phenology and responses to winter warming. Am. J. Bot. 2022, 109, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yoong, F.Y.; O’Neill, C.M.; Penfield, S. Temperature during seed maturation controls seed vigour through ABA breakdown in the endosperm and causes a passive effect on DOG1 mRNA levels during entry into quiescence. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, G.M.; Lee, M.H.; Park, C.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.M.; Na, C.S. Dormancy-release and germination improvement of Korean bellflower (Campanula takesimana Nakai), a rare and endemic plant native to the Korean peninsula. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.H.; Rhie, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Ko, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, K.C. Effect of after-ripening, cold stratification, and GA3 treatment on Lychnis wilfordii (Regel) Maxim. seed germination. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Yang, M.; Baskin, C.C.; Li, M.; Zhu, M.; Jiao, C.; Zhang, P. Type 2 nondeep physiological dormancy in seeds of Fraxinus chinensis subsp. rhynchophylla (Hance) A.E. Murray. Forests 2022, 13, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.; Baskin, C.C.; Lu, J.J.; Tan, D.Y.; Baskin, J.M. A new type of non-deep physiological dormancy: Evidence from three annual Asteraceae species in the cold deserts of Central Asia. Seed Sci. Res. 2014, 24, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, J. Achene heteromorphism in Bidens pilosa (Asteraceae): Differences in germination and possible adaptive significance. AoB Plants 2019, 11, plz026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.