Abstract

Extensive goat farming is the dominant livestock system in the Mediterranean region, where woody rangelands represent essential forage resources for goats. Understanding how goats move and select vegetation within these heterogeneous landscapes–and how these patterns are shaped by herding decisions-is critical for improving grazing management. This study investigated the spatio-temporal movement behavior of a goat flock in a complex woody rangeland using GPS tracking combined with GIS-based vegetation and land morphology mapping. The influence of seasonal changes in forage availability and the shepherd’s management on movement trajectories and vegetation selection was specifically examined over two consecutive years. Goat movement paths, activity ranges, and speed differed among seasons and years, reflecting changes in resource distribution, physiological stage, and herding decisions. Dense oak woodland and moderate shrubland were consistently the most selected vegetation types, confirming goats’ preference for woody species. The shepherd’s management—particularly decisions on grazing duration, route planning, and provision or withdrawal of supplementary feed—strongly affected movement characteristics and habitat use. Flexibility in adjusting grazing strategies under shifting economic conditions played a crucial role in shaping spatial behavior. The combined use of GPS devices, GIS software, vegetation maps, and direct observation proved to be an effective approach for assessing movement behavior, forage selection and grazing pressure. Such integration of technological and classical methods provides valuable insights into diet composition and resource use and offers strong potential for future applications in precision livestock management. Real-time monitoring and decision support tools based on this approach could help farmers optimize grazing strategies, improve forage utilization, and support sustainable rangeland management.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the economic sustainability of intensive livestock farming systems in the Mediterranean region appears to be constrained by prolonged economic uncertainty and their high dependency on capital [1,2]. As a result, extensive farming systems relying on native breeds well adapted to local environmental conditions, are gaining importance [3]. Public concern for animal welfare [4] and increasing demand for livestock products from extensively reared animals [5,6] further support the development of these systems.

Small ruminant farming is the most important livestock sector in Greece, contributing about 45% of the total value of livestock production [2,7]. Greece uniquely produces more milk from small ruminants than from cow milk [8] and leads the European Union in goat farming, with 2.6 million animals representing 24.6% of the EU total [9]. The predominant breed, the “Greek local” goat, is well adapted to mountainous and harsh environments, producing milk with higher fat and protein content despite lower yields compared to imported breeds [10,11].

Goats are able to exploit a wide range of vegetation types (herbs, shrubs, and trees) due to their anatomical and physiological traits, highlighting their exceptional adaptability to diverse habitats [12]. However, they prefer woody species over herbaceous ones [13,14,15,16,17], and their grazing behavior is more selective in heterogeneous woody rangelands compared to homogeneous grasslands [18]. Grazing patterns are influenced by both animal and environmental factors [19] as well as by shepherd management, which determines grazing areas, movement directions, and time spent in each area [20,21,22]. Mediterranean woody rangelands are biodiversity hotspots and strongly depend on traditionally managed goat grazing systems, yet quantitative information on how goats utilize the diverse vegetation mosaics under herding conditions remains limited.

Understanding goat feeding behavior and movement in the grazing area in relation to herding practices of shepherds is of great interest. Traditional direct observation methods are inexpensive but labor-intensive [23,24] and can affect animal’s behavior, although Perevolotsky et al. [25] reported that the grazing behavior of hand-raised and hand-milked goats remained unaffected by the close presence of the observer. Modern tools such as video monitoring, pedometers, accelerometers, automatic jaw movement recorders, and microcomputer-based systems allow more detailed, minimally invasive studies [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Global Positioning System (GPS)-tracking combined with Geographical Information Systems (GIS) mapping is increasingly used to study spatial utilization of rangelands and grazing behavior [24,26,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. However, few studies have combined GPS-GIS data with detailed assessments of shepherd management, economic context, and multi-year seasonal monitoring to capture how adaptive herding decisions shape movement, forage selection, and habitat use. Schlecht et al. [45], using these techniques, highlighted that the shepherd is an important factor implicitly affecting the grazing behavior of goats and their habitat selection, as he determines the movement paths and grazing periods in different areas. Nevertheless, they concluded that this human contribution to the behavior of goats’ locomotion needs further investigation in order to be more explicit.

In this study, the spatio-temporal movement behavior of grazing goats in a Mediterranean woody rangeland was investigated using GPS-tracking combined with GIS-based vegetation and land morphology mapping. Specifically, this work aims to provide the first detailed analysis of a shepherded goat flock monitored over two consecutive years and three seasons, quantifying how herding decisions interact with seasonal forage availability and economic constraints to influence movement trajectories, vegetation use, and habitat selection. The influence of shepherd management on goat trajectories and vegetation selection across different seasons over two consecutive years was specifically examined taking into account that: (1) Goat movement paths and activity ranges are expected to differ among seasons due to changes in forage availability; (2) Vegetation selection is expected to be influenced both by resource distribution and by the shepherd’s herding decisions; (3) Goat movement patterns and habitat utilization are expected to be affected by the shepherd’s adaptive decisions, which vary in response to prevailing economic conditions. Specifically, during periods of economic constraints, changes in herding strategies, grazing duration, and selection of feeding areas are expected to result in measurable alterations in spatial behavior and forage utilization of the flock. Finally, by combing GPS-based analysis with previously collected bite-count data from the same site, the study offers a novel methodological triangulation that allows independent validation of vegetation selection patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

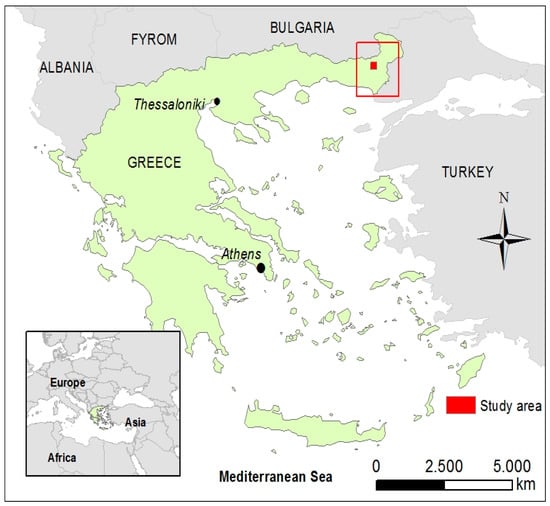

The experiment was conducted during 2010 and 2011 in a mixed Hungarian oak (Quercus frainetto)—prickly juniper (Juniperus oxycedrus) rangeland. The area is located near the small village of Megalo Dereio (41°14′ N; 26°01′ E, 380 m a.s.l) (Figure 1) in the Evros region of Northeastern Greece. The climate is sub-Mediterranean, with an average annual rainfall of 565 mm and a mean annual air temperature of 13.4 °C [46]. During the study period, weather conditions varied greatly. In particular, in 2010 and 2011, annual rainfall was 690 and 430 mm and mean temperatures were 15.7 and 14.3 °C, respectively. Moreover, unusually high rainfall and temperature levels were recorded in November 2010 compared with the same month of 2011 (see [16]).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in Greece.

2.2. Forage Composition—Vegetation Map

The forage composition of the area was measured by the authors at the beginning of the experiment and for practical reasons was divided into eight functional groups: Quercus frainetto (8.93%), Juniperus oxycedrus (8.46%), Cistus creticus (15.85%), other woody species (0.72%), grasses (35.76%), legumes (14.24%), and forbs (16.04%). The other woody species group consisted mainly of Carpinus orientalis and Paliurus spina-christi. The forage composition was assessed using vegetation measurements based on the line-point transect method, and the percentage of each functional group reflects its relative frequency along the transects (see [16]).

In order to generate a detailed vegetation map of the study area, homogeneous polygons with a minimum mapping unit of 0.05 ha were delineated using on-screen digitizing of natural color orthoimages. The orthoimage quadrangles used in the study were produced from natural color aerial imagery acquired in 2009 using a Leica ADS40 Airborne digital camera system (Leica Geosystems, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) under the Hellenic National Cadastre campaign and were available on a web mapping service (WMS) (http://gis.ktimanet.gr/wms/wmsopen/wmsserver.aspx, accessed on 20 August 2025). Stereo-pairs of air photos were also used as a supplement to monoscopic on-screen interpretation in order to identify indistinct features. Additionally, during the land use/land-cover mapping process, an existing map produced during the compilation of a recent forest management plan of the area was considered.

Furthermore, the canopy cover of the area was extracted following procedures similar processing to those described earlier. Overall, based on the spatial overlay of the vegetation and canopy cover maps, a detailed final classification scheme was developed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classes of vegetation type of the study area.

2.3. Goat Flock Management

For the present study, a flock of 650 Greek local breed female goats was used. All animals used in the study were of the same age class (3–4 years), in the same productive stage and had similar body characteristics (see [16]). The flock grazed from early March to mid-December, depending on weather conditions, whereas it was kept indoors and fed with alfalfa hay and cereal grains (corn and wheat) during the winter.

The production system was the traditional sedentary extensive, in which the farmer remains on-site and the flock grazes in the same region throughout the whole year [47]. A shepherd led the flock to a communal rangeland during all the grazing season and made decisions about the direction of the flock’s routes by taking into consideration the forage availability in the specific season and criteria to prevent overgrazing, as the area was grazed by other flocks (mainly goats, with fewer sheep) and a few cattle herds.

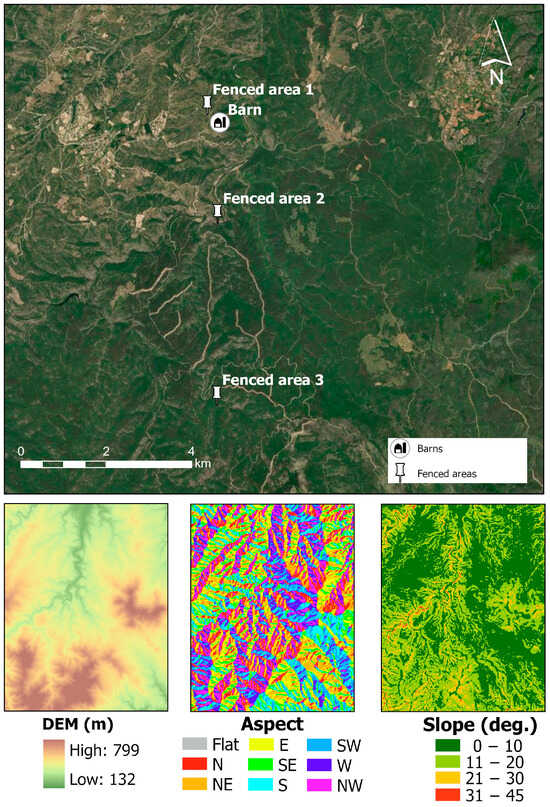

A rangeland area of about 25 km2 was available for grazing to the experimental flock, which after the daily grazing returned to the barn (B) (Figure 2) to be housed during the night. In the barn, the goats received supplementary feeds and the shepherd hand-milked them twice per day (early morning and late afternoon) as is traditionally applied in such production systems in Greece [48]. A fenced area (FA1), about 500 m away from the barn, was used as a waiting area for the flock before leaving for the grazing areas. Apart from FA1, there were two other fenced areas (FA2 and FA3) (Figure 2) located, respectively, at about 2.3 and 6.5 km from the barn, which were used during autumn to keep the flock close to the less-grazed areas at night and provide access to better forage resources.

Figure 2.

The available rangeland with the barn (B) and the fenced areas (FA1, FA2, and FA3).

The lactation stage lasted from early March to late August, and the shepherd managed the duration of the daily grazing time by taking into account the productive stage of the goats as well as the supplementary feeding. During the study period, the shepherd significantly modified the amounts of supplementary feeds (Table 2), considering both their price as well as the selling price of the milk.

Table 2.

Flock management and feed supplement schedule.

Particularly, the goats received 400 g corn grains and 400 g wheat grains per head during spring and summer of 2010. No additional supplementary feeding was provided to the flock during the autumn (both 2010 and 2011) as the lactation stage had been completed. During the spring of 2011, apart from corn and wheat grains, the farmer supplied to the goats with an additional 400 g alfalfa hay per head in order to increase their productivity, since milk prices were high, but he stopped providing any supplementary feeds during summer of 2011, because prices of supplementary feeds increased markedly.

As the purpose of the present research was to study and record the existing management practices of the shepherd, no recommendation was given to him that could affect his decisions.

2.4. Goats Tracking

The experiment was performed using commercial, lightweight, and low-cost GPS data loggers (Qstarz BT-Q1000XT, Taipei, Taiwan), as they are suitable for studying animal movements in open habitats such as pastures [37]. The GPS data loggers were attached to collars that were placed on individual female goats during spring (May), summer (July), and late autumn (November) of 2010 and 2011. On each occasion, goats were randomly selected from the flock while ensuring comparable body size, age, and physiological condition, in order to minimize potential behavioral or hierarchical biases. Ten GPS data loggers were used during 2010 and twenty during 2011, to increase the sample size. Previous studies on free-ranging goats in similar extensive systems have shown that a subset of 10–20 individuals can adequately capture flock-level movement patterns when selected randomly [38,40,45]. This approach balances the need for representative data with logistical constraints and animal welfare considerations, as equipping all 650 goats with GPS collars would not be feasible.

The devices were set to record the geographical position (latitude, longitude, and altitude) every 5 s, providing high temporal resolution of movement patterns. The typical positional accuracy of the GPS model is approximately ±3 m under open-sky conditions, as reported by the manufacturer and confirmed in preliminary field tests, while position-fix success rates were consistently above 95% in open areas and decreased under dense canopy cover. To ensure data, positions associated with impossible movement speeds (>5 m s−1) or implausible altitudinal changes were removed, and those recorded under dense canopy with low positional accuracy were flagged and excluded from the analysis. Due to the low battery capacity and high recording frequency, the GPS data loggers were removed from the animals every night after their return to the barn (B) or fenced areas (FA) (Figure 3) in order to download the data via USB and recharge their batteries, and were repositioned the next morning on different individuals randomly selected among goats of similar characteristics. Data were recorded for four consecutive days during each experimental period.

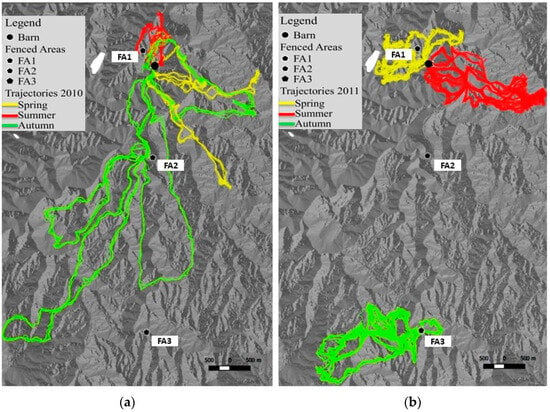

Figure 3.

Goats’ trajectories and movement patterns in the study area during (a) 2010 and (b) 2011.

2.5. Processing of GPS Data

GPS locations were screened for positional errors following Bjørneraas et al. [49], and positions showing unreliable deviations from movement paths were excluded. Furthermore, the locations within or very close to fenced areas (FA1, FA2, and FA3) and the barn were deleted, because within these areas the behavior of animals could not be considered independent. The GPS locations for each animal were converted into trajectories (i.e., the sequence of location points and the segments connecting them) [50]. The analysis was performed using only complete individual daily trajectories (n = 74 in 2010; n = 211 in 2011). Different metrics characterizing each trajectory were then computed. The “duration” (h d−1) was calculated as the time elapsed between the first and the last position recorded. This variable indicates the total time that the collared goats spent daily in the rangeland. The distance traveled daily (km d−1) was expressed as “horizontal distance” by summing the lengths of all segments of each trajectory, as “total distance” by summing each segment length corrected for the altitudinal gradient between the initial and final position, and as “vertical distance” by summing all absolute elevation differences between consecutive locations. The “speed” (m s−1) was calculated by dividing “total distance” by “duration”. The portions of each trajectory overlapping each vegetation type were then extracted, in order to calculate the “proportion of time” (% of total duration) spent in each vegetation type for each trajectory. For the habitat selection analysis, availability areas were defined by creating seasonal buffers of 150 m along the paths. The choice of a seasonal buffer of 150 m around the trajectories was based on the flock’s management practices. Specifically, the flock was actively herded by shepherds during monitored movements, which limited the free movement of individual animals. For each area so defined, the percentage of each vegetation type inside was calculated. The GPS and vegetation data were organized and processed in a PostgreSQL 9.5 + Post-GIS 2.2 (www.postgresql.org/; http://postgis.refractions.net) and Quantum GIS 2.16 (www.qgis.org).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The metrics describing individual goats’ trajectories (duration, distances, and speed) as well as the proportion of time spent in each vegetation type were sorted according to the three seasons of grazing (spring, summer, and autumn) of the two years under investigation (2010 and 2011), and the differences between seasons, years and their interaction were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Also, analysis of the effect of the seasons on the above measurements within each trial year was carried out using one-way ANOVA. Tukey–Kramer HSD test was used to perform the multiple comparisons for all pairs of means. The significance level was set to p < 0.05 [51]. The statistical analysis was performed using version 8.0 of the JMP software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A principal component analysis (PCA) was used to describe and interpret the goats’ movement behavior according to the vegetation types. Characteristics of individual goat trajectories (duration, total distance, vertical distance, and speed) were chosen as the main variables of the analysis. In addition, variables expressing the time spent by the goats in each vegetation type in the rangeland were used as supplementary variables, with the R package FactoMiner [52]. Data were initially scaled to unit variance before the analysis to avoid the influence of measurement units on the principal components.

Selection of vegetation type was analyzed with a compositional analysis of log ratios [53] using the Compos analysis software [54]. The compositional analysis of habitat use is a multivariate technique recommended by Aebischer et al. [53] for the analysis of habitat selection by several animals, when the resources are defined by several categories (e.g., vegetation types).

The analysis was performed for each season and year. The availability was defined as the percentage of each vegetation type on the total surface of the trajectories used in each season, with a buffer of 150 m, as explained in Section 2.5; the use was calculated as the allocation of time spent by collared goats in each vegetation type. In some seasons, some vegetation types were not available in the trajectories and for this reason, the classes considered differed among seasons.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Goats’ Trajectories

Significant differences in the characteristics of goats’ trajectories were found among years and seasons, and for their interaction (Table 3; Figure 3). The duration of the trajectories was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in 2011 (7.01 h d−1) than in 2010 (6.28 h d−1) whereas there were no significant differences for the total traveled distances. The distance of goats’ vertical movement was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in 2011 (0.67 km d−1) than in 2010 (0.59 km d−1), whereas the reverse trend was found for the horizontal distance (p < 0.05). Significantly higher (p < 0.001) movement speed of goats was recorded in 2010 (0.39 m s−1) compared to 2011 (0.36 m s−1).

Table 3.

Statistical significance from the analysis of variance of the metrics describing goats’ trajectories.

In autumn, the duration, the total, the horizontal, and the vertical distance of the trajectories were significantly higher (p < 0.001) compared to those of spring and summer. Additionally, goats moved at a higher speed in autumn (0.41 m s−1) than in spring (0.38 m s−1) and summer (0.35 m s−1).

Due to significant differences among the seasons and years as well as the different management practices of the shepherd during the study period, these characteristics were further analyzed separately for each year. During 2010, the average duration of the flock’s movement in the rangeland was 8.37 h d−1 and 8.03 h d−1 in spring and autumn, respectively, with no significant differences between them, while the duration was considerably shorter (p < 0.001) in summer (Table 4). Significant differences (p < 0.001) were recorded in the total traveled distance of the goats among the seasons. The average total distance was significantly higher in autumn, followed by spring, while in summer the travel distance was the shortest. The same tendency was found for the horizontal and vertical distances of the trajectories among the seasons. In autumn, the goats walked during their movement in the rangeland at a higher speed (0.48 m s−1) compared with the other two seasons (0.33 and 0.37 m s−1 in spring and summer respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Metrics describing goats’ trajectories in 2010 and 2011. Data show mean ± standard deviation, p-values and effect size (n2).

During 2011, the flock of goats spent 9.81 h d−1 during summer in the rangeland, a duration significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the other seasons. The duration of the flock’s movement was significantly higher in autumn than in spring (Table 4). The traveled distance by the flock differed significantly (p < 0.001) among the seasons, with the longest daily average 11.44 km d−1 during summer, followed by autumn and spring. The longer uphill movement of goats was recorded during summer and autumn (0.85 and 0.83 km d−1, respectively) without significant differences between them, and both were significantly higher than in spring. On the contrary, the average speed of goats’ movement in the rangeland was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in spring compared to the other seasons (Table 4).

3.2. Vegetation Type Selection

3.2.1. Spent Time Allocation

Both season and year, as well as their interaction, significantly affected the proportion of time that goats spent in different vegetation types (Table 5). The flock spent a higher proportion of time (p < 0.01) in the grassland during 2011 (16.57%) compared with 2010 (11.80%). The proportion of time in the grassland differed widely (p < 0.001) among seasons, and the highest percentage was recorded during spring, followed by autumn. Significantly higher was the time that the flock spent in the abandoned agricultural land during spring and summer compared to autumn (p < 0.001), while the flock spent more time in this vegetation type during 2010. Both moderate and dense oak woodland were preferred by the goats in higher rates (p < 0.001) during 2011 than in 2010 while autumn was the season with the highest time proportions compared with the other seasons. The proportion of time spent either in open or moderate shrubland was higher during 2010 (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively) and in spring (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Statistical significance from the analysis of variance of the daily time (%) in the rangeland spent the goats in different vegetation type.

During 2010, significant differences among the seasons were recorded in the proportion of time spent by the flock of goats in all the vegetation types (Table 6). The percentages of time in the abandoned agricultural land were 22.22% and 26.34% in spring and summer, respectively, which were significantly higher (p < 0.001) compared to autumn (4.48%). The grassland was used by the flock at higher rates during spring and autumn (p < 0.001) whereas the moderate oak woodland was used mainly during autumn (p < 0.001). The flock spent a high proportion of its time during the movement through the rangeland in the dense oak woodland. The highest percentage was recorded in autumn (39.51%) without significant difference from spring (32.59%), followed by the summer (31.46%) (p < 0.01). The open shrubland was used by the goats in significantly higher share in spring (11.53%) whereas the moderate shrubland was used mainly in summer at a rate of 35.20% (p < 0.001).

Table 6.

Proportion (%) of the daily time in the rangeland spent the goats in different vegetation type during 2010 and 2011. Data show mean ± standard deviation, p-values, and effect size (n2).

During 2011, as illustrated in Table 6, the proportion of time spent in the rangeland allocated to different vegetation types significantly differed among seasons (p < 0.001). The flock of goats used the grassland and the abandoned fields mainly in spring, whereas the coniferous plantation was used in autumn. Both moderate and dense oak woodland were used at significantly higher rates in autumn (11.77% and 64.69%, respectively) and at lower rates in spring. Finally, goats spent a high proportion of their time during spring in the moderate shrubland at a rate of 36.50%, which was significantly higher than the corresponding proportions in summer and autumn.

3.2.2. Vegetation Type Ranking

The results of compositional analysis (Table 7) indicated different preferences for vegetation types among periods. In spring 2010, abandoned agricultural land, grassland, riparian areas, and moderate shrubland were preferred to the other vegetation types. In summer 2010, the preferences were less evident, with moderate oak woodland being less used. In autumn 2010, on the other hand, moderate oak woodland was the preferred vegetation type, along with grasslands, whereas abandoned agricultural land was avoided.

Table 7.

Results of compositional analysis of time spent by goats in each vegetation type versus availability of each category within the study area (second-order selection). “>>>” indicates a significant positive selection of one class, while “>” indicates non-significant selection.

In 2011 the goats’ preferences changed: in spring the preferred vegetation type was moderate shrubland; in summer, grasslands and moderate oak woodland were preferred, and abandoned agricultural land was avoided; in autumn moderate oak woodland was strongly selected, and coniferous plantation was avoided.

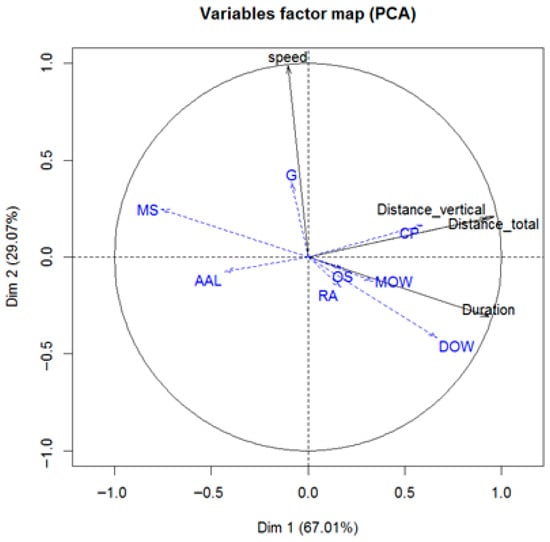

3.3. PCA on the Behavioral Variables of Goats

A PCA was performed for the characteristics of individual goat trajectories and the classes of the available vegetation in the study area, throughout the overall periods under investigation. The first component (Dim 1) of the PCA (Figure 4) explained 67.01% of the data variability and was mainly associated with total and vertical distance, movement duration, and the use of coniferous plantation and dense oak woodland. This axis, therefore, represents a gradient of movement intensity and the use of closed or woody habitats (Table 8). The second component (Dim 2), explaining 29.07% of the variance, was primarily correlated with speed and grassland, contrasting with moderate shrubland and abandoned agricultural land, and thus reflects a gradient of movement rate and openness of vegetation (Table 8). Together, the first two components accounted for 96.08% of the total variance, effectively summarizing the main patterns of goat movement behavior across vegetation types.

Figure 4.

Plot of variables and the PCA axes of the two first principal components (variables include: Duration, Distance_total, Distance_vertical, Speed, AAL = Abandoned agricultural land, CP = Coniferous plantation, G = Grassland, MOW = Moderate oak woodland, DOW = Dense oak woodland, RA = Riparian area, OS = Open shrubland, MS = Moderate shrubland). Names of explanatory variables are in italics.

Table 8.

Loadings (Cos2) of the variables on the two main PCA axes (Dim 1 and Dim 2) (variables include: Duration, Distance_total, Distance_vertical, Speed, AAL = Abandoned agricultural land, CP = Coniferous plantation, G = Grassland, MOW = Moderate oak woodland, DOW = Dense oak woodland, RA = Riparian area, OS = Open shrubland, MS = Moderate shrubland).

4. Discussion

The present study examined how the shepherd’s management practices over two consecutive years influenced the spatio-temporal movement and vegetation choices of goats grazing in a Mediterranean woody rangeland. In extensive pastoral systems, socieconomic conditions influence herding decisions and flock mobility strategies [55,56]. The shepherd’s key management choices, including grazing system, daily grazing duration, stocking rate, and feed supplementation, are essential for optimizing productivity while supporting rangeland biodiversity under changing climate conditions [57,58].

Marked annual differences were recorded in the shepherd’s management practices of the grazing and time spent in the rangeland. His decisions reflected both animal and environmental factors, including the goats’ productive stage, seasonal forage availability, feed prices, and milk value, aiming to maintain farm efficiency and household livelihood [59]. Moreover, the shepherd took into consideration criteria to prevent overgrazing in the communal rangeland, acknowledging that excessive pressure reduces rangeland productivity and degrades vegetation [38,60,61].

Low-intensity grazing in such heterogeneous landscapes promotes plant diversity and ecosystem stability [62]. Moreover, it is well documented that shepherds’ herding decisions, based on knowledge of seasonal forage dynamics and plant phenology, influence how goats can exert their dietary preferences [63,64]. Therefore, this study also analyzed how goats selected among vegetation types along their movement routes, in relation to the shepherd’s choices and the available vegetation types.

4.1. Goats’ Trajectories

Castro and Fernández Núñez [39] reported that grazing duration and behavior of small ruminants depend on forage availability and the production system. Similarly, several authors have found significant seasonal and management differences in the duration and length of goats’ itineraries [38,45,65]. In this study, all movement characteristics differed significantly among seasons and/or years, reflecting the varying management practices applied by the shepherd.

During 2010, the duration and distances of goats’ trajectories were much shorter in summer than in spring and autumn. Between these two seasons, duration was similar, but distances were longer in autumn, while movement speed was highest in autumn and lowest in spring and summer. In spring 2010, when goats were in early lactation and had high nutrient requirements, the shepherd supplied them with supplementary feed and allowed extensive grazing, resulting in long durations and low speed. In summer 2010, goats were in late lactation with lower nutritional needs; the shepherd-maintained supplementation but reduced grazing time by about 2.5 h per day and kept the flock in fenced area 1 (FA1) close to the barn (B), where water was available, leading to shorter distances. High temperatures also contributed to this reduction, as observed by Akasbi et al. [38] and Thomas et al. [66], who reported shorter walking distances during hot weather. In autumn, when goats were dry and no longer supplemented, their nutritional needs were met exclusively by grazing. The shepherd extended the grazing routes and moved the flock from fenced area 2 (FA2) to more distant areas with better forage, which increased both distance and speed. Similar relationships between longer routes and higher movement speed were reported by Schlecht et al. [22]. In contrast, Cheng et al. [67] found lower speeds in spring and winter in semi-arid Chinese grasslands with different vegetation and climate characteristics. Jouven et al. [43] noted that herders influence flock movement and distribution by modifying the location of shelters, while Akasbi et al. [38] similarly observed that in Southern Morocco, goats traveled longer distances in autumn to reach areas with available fodder. During 2011, contrary to 2010, goats’ trajectory duration and distances were longest in summer, intermediate in autumn and shortest in spring, while speed was highest in spring. To meet the nutritional needs of goats in early lactation, the shepherd increased supplementary feeding compared to spring 2010, keeping the flock in fenced area 1 (FA1) and providing additional alfalfa hay (400 g/animal), which resulted in shorter grazing periods. In summer 2011, although goats were still in late lactation, the shepherd stopped supplementation due to the rising prices of feedstuffs and the decline in milk value. It is generally accepted that feed costs represent the main variable expense in small ruminant farming [8,68], and the economic pressure led to longer grazing times and distances, as pasture is the most economical feed source [69]. Similar behavior was reported by Chebli et al. [17], who suggested that goats extend grazing to satisfy nutritional needs efficiently. In autumn 2011, both grazing duration and distances declined relative to summer, likely reflecting the goats’ lower nutrient needs as they were in the dry period and the shepherd’s decision to reduce range access. However, vertical distance remained comparable to summer, as the starting point of the trajectories (FA3) and surrounding terrain were steeper. Lachica et al. [29] likewise observed longer distances in summer than autumn in Mediterranean mountain rangelands, while Schlecht et al. [22] reported the opposite pattern in northern Oman. Such regional differences are expected, as herding strategies vary with forage availability and quality, vegetation type, and climatic conditions [21,38].

The shepherd decisions had a strong influence on grazing time and movement paths, which varied considerably among seasons. Changes in grazing duration reflected a trade-off between animal needs, feed costs, and the shepherd’s willingness to reduce labor time for personal or family activities [70], which is a common feature of extensive systems [8,71]. When supplementary feeds were affordable relative to milk income, the shepherd shortened rangeland access, but reversed this decision when high feed costs could be offset by extending grazing and working time. Similarly, Al-Khalidi et al. [72] reported that herders often intensify grazing to reduce feed expenses, while Papadopoulou et al. [73] emphasized that grazing enhances flexibility, competitiveness, and long-term sustainability. Greater movement distances not only increase the shepherd’s workload but also raise animals’ maintenance energy requirements. For example, an additional 1 km walked on flat terrain corresponds to an energy cost of about 3.35 J/kg body weight [74]. Considering the observed variation in trajectory distances between months and years, these energetic costs may represent a substantial trade-off for extended grazing time. Although body weight and milk production data were not recorded, integrating such measurements with detailed trajectory analysis would allow a more accurate assessment of the energetic and economic implications of the shepherds’ management decisions.

4.2. Vegetation Type Selection

The goats followed different trajectory patterns across seasons and years, guided by the shepherd to utilize seasonally available vegetation [21,75]. These differences were reflected in the variation in time spent in each vegetation type. Both year and season significantly affected this distribution, with season exerting the strongest influence, as also reported by Manousidis et al. [76] and Feldt and Schlecht [65], who linked seasonal grazing behavior to forage availability and vegetation composition. The time spent and movement speed within each vegetation type indicated whether goats were led there to graze or simply to pass through. These patterns are primarily the results of the shepherd’s choices, informed by his knowledge of goats’ preferences and vegetation quality. The study also examined vegetation selection along the goats’ routes, which reflects mainly their own foraging behavior.

Results from a previous study at the same site [16], where forage selection was measured by direct observation, were used for comparison. In that study, bite counts of major plant groups (Q. frainetto, J. oxycedrus, C. creticus, Other woody, Grasses, Legumes, Forbs and Acorns) were converted into dietary percentages. Comparing these findings with GPS-based data provided valuable insights into vegetation type preferences.

Goats spent more time in coniferous plantations during autumn because the trajectories started nearby (FA2 and FA3). However, these areas were mainly crossed rather than grazed due to their sparse understory vegetation. In contrast, time spent in moderate and dense oak woodland was significantly higher in autumn, reflecting better forage availability. Goats also used abandoned agricultural land more in spring and summer. Although grazing on agricultural land is usually restricted to avoid crop damage and conflicts between farmers [77], the local fields were infertile, long abandoned, and covered by native herbaceous vegetation, thus serving as grazing areas [65]. Goats spent more time in grasslands during spring when herbaceous forage was most abundant, consistent with previous reports that goats increase consumption of herbaceous plants when they are available [78,79]. Use of shrubland also increased in spring, particularly in moderate shrubland, due to goats’ preference for J. oxycedrus, the dominant shrub species in this vegetation type [16].

During 2010, goats spent the highest proportion of time in grasslands during spring and autumn, with no significant difference between the two seasons. This preference was reflected in forage selection, as direct observation showed that herbaceous plants accounted for 58.4% and 49.2% of total bites in spring and autumn, respectively [16]. Although high herbaceous consumption in spring was expected [12,79], unusually heavy rainfall and warm temperatures promoted regrowth in autumn, increasing forage availability. Aharon et al. [14] similarly reported that the Boer goat breed consumed herbaceous forage equally in both seasons following heavy autumn rainfalls. In this study, the shepherd guided the flock to grasslands in order to exploit the increased autumn availability.

During autumn 2010, goats spent about 50% of their grazing time in oak woodlands (moderate and dense). Despite the early defoliation of oaks [16], they foraged on C. creticus and acorns, which were abundant that year due to the masting of Q. frainetto. Time spent in dense oak woodland (about 32%) did not differ between spring and autumn, although the proportion of Q. frainetto in the diet was higher in summer [16], likely because goats also consumed herbaceous understory vegetation. Similar patterns were reported by Benmellouk [80] in northern Portugal, where goats showed a strong preference for oak forests, particularly in summer and autumn.

High grazing time allocation in open shrubland during spring 2010 and in moderate shrubland during summer 2010 corresponds to the consumption of J. oxycedrus. Direct observation showed that goats remained in shrublands primarily to consume J. oxycedrus in both seasons, and secondarily herbaceous plants in spring. Similar seasonal patterns occurred in 2011. Goats spent the highest proportion of time in grasslands during spring, matching the increased consumption of herbaceous species [16]. Oak woodland was mostly used according to shepherd guidance. The smallest time allocation to moderate and dense oak woodland was recorded in spring, consistent with the reduced contribution of Q. frainetto to the goats’ diet composition [16]. On the contrary, time spent in both oak woodland types peaked in autumn, accompanied by intake of Q. frainetto and C. creticus, the latter representing about 75% of total bites [16]. Goats rarely used open shrubland in 2011, but spent 36% of their grazing time in moderate shrubland during spring—the highest of the year—mirroring the increased selection of J. oxycedrus (about 23% of bites) [16], its dominant shrub species.

The multivariate analysis of trajectory characteristics supports these findings. Total and vertical distance increased when the shepherd led the flock towards distant, hilly areas with better forage—mainly dense oak woodland—requiring passage through coniferous plantations and resulting in longer itineraries. On the contrary, spending more time in moderate shrubland or abandoned agricultural land, both located near the barn, resulted in shorter and less extensive routes. Movement speed increased in grasslands, where herbaceous vegetation was less preferred by the browsing goats.

Compositional analysis further confirmed shifts in vegetation type preferences across seasons and years, highlighting a consistent preference for oak woodland, particularly in autumn and more strongly in 2011. Overall, the ranking of vegetation types matched patterns observed in forage selection and diet composition [16].

4.3. Limitations

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the number of GPS-collared goats, although consistent with similar studies, represents only a subset of the flock and may not fully capture individual behavioral variability. This restriction was partly due to the high cost of GPS devices, which made larger sample sizes impractical. Second, time allocation within each vegetation type was used as a proxy for feeding activity, but goats may rest, ruminate, or simply pass through an area, which can lead to an overestimation of true grazing behavior. Third, activity classification relied solely on movement metrics rather than accelerometer-based data, limiting the ability to distinguish accurately between grazing, moving, and resting. Fourth, vegetation availability was defined based on buffered daily trajectories, reflecting the areas the flock actually visited under the shepherd’s management. This approach may underestimate the availability of distant vegetation types that were not reached for management reasons. If availability were defined using the full seasonal range, relative preferences for more remote or higher-quality vegetation types might differ. Lastly, because the shepherd strongly influenced daily routes, vegetation not accessed during the study cannot be evaluated for potential goat preference independently of management constraints.

5. Conclusions

The movement trajectories of goats varied significantly among seasons and years, with dense oak woodland and moderate shrubland being the most selected vegetation types, confirming their preference for woody species. Shepherd management practices strongly influenced both movement patterns and vegetation selection, demonstrating the importance of experience and flexibility in adapting grazing strategies under changing vegetation and economic conditions.

The combination of GPS collars, GIS software, vegetation maps, and direct observation proved to be an effective tool for studying the spatio-temporal movement behavior and forage selection of grazing goats. This combined approach can provide valuable insights into grazing behavior, diet composition, and forage resource use.

Future applications of this approach could help livestock farmers better understand the quantity and quality of forages consumed by grazing goats and provide rangeland managers with key information on grazing pressure across vegetation types. Moreover, these methods offer strong potential for precision livestock management through real-time monitoring and decision-support tools that optimize grazing strategies, improve forage utilization, and support sustainable rangeland management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A., A.P.K. and T.M.; data collection, T.M.; data analysis T.M., P.S., E.S., G.M. and A.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.; writing—review and editing, A.P.K., E.S. and A.C.P.; supervision, Z.A. and A.P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author T.M. The data are not publicly available as they were collected by T.M. for his PhD thesis with no external funding and will be used for further processing.

Acknowledgments

The GPS data analysis was performed as a part of the Erasmus+ traineeship program of the fist author in the Department of Agronomy, Food, Natural Resources, Animals and Environment (DAFNAE), University of Padova, Italy. He is grateful to the people of DAFNAE for the technical support on GIS issues and for their hospitality. He is also grateful to Hamdi Kourt, the shepherd of the experimental flock, for his permission to work with his goats and for his kind cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Manousidis, T.; Abas, Z.; Ragkos, A.; Abraham, E.M.; Parissi, Z.M.; Kyriazopoulos, A.P. Effects of the economic crisis on sheep farming systems: A case study from the north Evros region, Greece. Options Méditerr. Ser. A Mediterr. Semin. 2012, 102, 439–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ragkos, A.; Koutsou, S.; Manousidis, T. In Search of Strategies to Face the Economic Crisis: Evidence from Greek Farms. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2016, 21, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachica, M.; Aguilera, J.F. Energy expenditure of walk in grassland for small ruminants. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 59, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szűcs, E.; Geers, R.; Jezierski, T.; Sossidou, E.N.; Broom, D.M. Animal Welfare in Different Human Cultures, Traditions and Religious Faiths. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.P.; Dwyer, C.M. Welfare assessment in extensive animal production systems: Challenges and opportunities. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montossi, F.; Font-i-Furnols, M.; Del Campo, M.; San Julián, R.; Brito, G.; Sañudo, C. Sustainable sheep production and consumer preference trends: Compatibilities, contradictions, and unresolved dilemmas. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Fthenakis, G.C. Data on Mapping 444 Dairy Small Ruminant Farms during a Countrywide Investigation Performed in Greece. Animals 2023, 13, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rancourt, M.; Fois, N.; Lavin, M.P.; Tchakerian, E.; Vallerand, F. Mediterranean sheep and goats production: An uncertain future. Small Rumin. Res. 2006, 62, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Data. Statistical Databases. 2025. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- European Farm Animal Biodiversity Information System (EFABIS). Breed Data Sheets. 2016. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dad-is/regional-national-nodes/efabis/tools/en/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Boyazoglu, J.; Morand-Fehr, P. Mediterranean dairy sheep and goat products and their quality. A critical review. Small Rumin. Res. 2001, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decandia, M.; Yiakoulaki, M.D.; Pinna, G.; Cabiddu, A.; Molle, G. Foraging Behaviour and Intake of Goats Browsing on Mediterranean Shrublands. In Dairy Goats Feeding and Nutrition; Cannas, A., Pulina, G., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, J.; Fellahi, M.; Benmellouk, I.; Castro, M.; Yessef, M. Enhancing rangeland management through technology: A case study of sheep and goat grazing in Montesinho Natural Park. In Proceedings of the 12th International Rangeland Congress, Adelaide, Australia, 2–6 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aharon, H.; Henkin, Z.; Ungar, E.D.; Kababya, D.; Baram, H.; Perevolotsky, A. Foraging behavior of the newly introduced Boer goat breed in a Mediterranean woodland: A research observation. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 69, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aich, A.; El Assouli, N.; Fathi, A.; Morand-Fehr, P.; Bourbouze, A. Ingestive behavior of goats grazing in the Southern Argan (Argania spinosa) forest of Marocco. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 70, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousidis, T.; Kyriazopoulos, A.P.; Parissi, Z.M.; Abraham, E.M.; Korakis, G.; Abas, Z. Grazing behavior, forage selection and diet composition of goats in a Mediterranean woody rangeland. Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 145, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, Y.; El Otmani, S.; Hornick, J.-L.; Keli, A.; Bindelle, J.; Cabaraux, J.-F.; Chentouf, M. Forage Availability and Quality, and Feeding Behaviour of Indigenous Goats Grazing in a Mediterranean Silvopastoral System. Ruminants 2022, 2, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iussig, G.; Lonati, M.; Probo, M.; Hodge, S.; Lombardi, G. Plant species selection by goats foraging on montane semi-natural grasslands and grazable forestlands in the Italian Alps. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 14, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuth, J.W. Foraging behavior. In Grazing Management. An Ecological Perspective; Heitschmidt, R.K., Stuth, J.W., Eds.; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1991; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, S.; Provenza, F.; Silanikove, N. Feeding behaviour and utilization of vegetation by goats under extensive systems. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Goats, Tours, France, 15–18 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ouédraogo-Koné, S.; Kaboré-Zoungrana, C.Y.; Ledin, I. Behaviour of goats, sheep and cattle on natural pasture in the sub-humid zone of West Africa. Livest. Sci. 2006, 105, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlecht, E.; Dickhoefer, U.; Gumpertsberer, E.; Buerkert, A. Grazing itineraries and forage selection of goats in the Al Jabal al Akhdar mountain range of northern Oman. J. Arid Environ. 2009, 73, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetsch, A.L.; Gipson, T.A.; Askar, A.R.; Puchala, R. Invited review: Feeding behavior of goats. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, D.G.; Derner, J.D. Assessing herbivore foraging behavior with GPS collars in a semiarid grassland. Sensors 2013, 13, 3711–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevolotsky, A.; Landau, S.; Kababia, D.; Ungar, E.D. Diet selection in dairy goats grazing woody Mediterranean rangeland. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 57, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Winters, C.; Estell, R.E.; Fredrickson, E.L.; Doniec, M.; Detweiler, C.; Rus, D.; James, D.; Nolen, B. Characterising the spatial and temporal activities of free-ranging cows from GPS data. Rangeland J. 2012, 34, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.W.; Heitschmidt, R.K.; Dowhower, S.L. Evaluation of pedometers for measuring distance traveled by cattle on two grazing systems. J. Range Manag. 1985, 39, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Saini, A.L.; Singh, N.; Ogra, J.L. Seasonal variations in grazing behaviour and forage nutrient utilization by goats on semi-arid reconstituted silvopasture. Small Rumin. Res. 1998, 27, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachica, M.; Somlo, R.; Barroso, F.G.; Boza, J.; Prieto, C. Goats locomotion energy expenditure under range grazing conditions: Seasonal variation. J. Range Manag. 1999, 52, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.; Siebert, S.; Buerkert, A.; Schlecht, E. Use of a tri-axial accelerometer for automated recording and classification of goats’ grazing behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 119, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, S.M.; Champion, R.A.; Penning, P.D. An automatic system to record foraging behavior in free-ranging ruminants. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1997, 54, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animut, G.; Goetsch, A.L.; Aiken, G.E.; Puchala, R.; Detweiler, G.; Krehbiel, C.R.; Merkel, R.C.; Sahlu, T.; Dawson, L.J.; Johnson, Z.B.; et al. Grazing behavior and energy expenditure by sheep and goats co-grazing grass/forb pastures at three stocking rates. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 59, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, K. Automatic Registration of Dairy Cows Grazing Behaviour on Pasture. Ph.D. Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkiewicz, S.M.; Fuller, M.R.; Kie, J.G.; Bates, K.K. Global positioning system and associated technologies in animal behaviour and ecological research. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 2163–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, Y.; Chentouf, M.; El Otmani, S. Application of precision livestock farming to monitor the grazing behavior of goats. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies in Agriculture, Food & Environment (HAICTA 2024), Karlovasi, Samos, Greece, 17–20 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Buerkert, A.; Schlecht, E. Performance of three GPS collars to monitor goats’ grazing itineraries on mountain pastures. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 85, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forin-Wiart, M.-A.; Hubert, P.; Sirguey, P.; Poulle, M.-L. Performance and Accuracy of Lightweight and Low-Cost GPS Data Loggers According to Antenna Positions, Fix Intervals, Habitats and Animal Movements. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasbi, Z.; Oldeland, J.; Dengler, J.; Finckh, M. Analysis of GPS trajectories to assess goat grazing pattern and intensity in Southern Marocco. Rangeland J. 2012, 34, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Fernández Núñez, E. Seasonal grazing of goats and sheep on Mediterranean mountain rangelands of northeast Portugal. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2016, 28, 91. Available online: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd28/5/cast28091.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Chebli, Y.; El Otmani, S.; Hornick, J.-L.; Keli, A.; Bindelle, J.; Chentouf, M.; Cabaraux, J.-F. Using GPS Collars and Sensors to Investigate the Grazing Behavior and Energy Balance of Goats Browsing in a Mediterranean Forest Rangeland. Sensors 2022, 22, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, S.M. The integration of GPS, vegetation mapping and GIS in ecological and behavioural studies. R. Bras. Zootec. 2007, 36, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.J.; Tozer, K.N.; Griffith, B.A.; Champion, R.A.; Cook, J.E.; Rutter, S.M. Foraging paths through vegetation patches for beef cattle in semi-natural pastures. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 141, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouven, M.; Lapeyronie, P.; Moulin, C.-H.; Bocquier, F. Rangeland utilization in Mediterranean farming systems. Animal 2010, 4, 1746–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, F.M.; Bailey, D.W.; Cibils, A.F.; Holechek, J.L. A GPS-based Evaluation of Factors Commonly Used to Adjust Cattle Stocking Rates on Both Extensive and Mountainous Rangelands. Rangelands 2020, 42, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlecht, E.; Hiernaux, P.; Kadaouré, I.; Hülsebusch, C.; Mahler, F. A spatio-temporal analysis of forage availability and grazing and excretion behavior of herded and free grazing cattle, sheep and goats in Western Niger. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 113, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, A. The Climate of Evros. 2006. Available online: http://www.orestiadaweather.gr (accessed on 15 October 2016).

- Hatziminaoglou, I.; Polyzos, N.; Magoulas, I.; Boyazoglou, I. Législation, utilisation par les animaux et perspectives: Cas de la Grèce. In Terres Collectives en Méditerranée. Histoire, Legislation, Usages, et Modes d’Utilisation par les Animaux; Bourbouze, A., Rubino, R., Eds.; INA Paris-Grignon: Paris, France, 1992; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjigeorgiou, I. Past, present and future of pastoralism in Greece. Pastoralism 2011, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørneraas, K.; Van Moorter, B.; Rolandsen, C.M.; Herfindal, I. Screening Global Positioning System location data for errors using animal movement characteristics. J. Wildl. Manag. 2010, 74, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calenge, C.; Dray, S.; Royer-Carenzi, M. The concept of animals’ trajectories from a data analysis perspective. Ecol. Inform. 2009, 4, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.G.D.; Torrie, J.H. Principles and Procedures of Statistics, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980; p. 481. [Google Scholar]

- Lê, S. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebischer, N.J.; Robertson, P.A.; Kenward, R.E. Compositional analysis of habitat use from animal radio-tracking data. Ecology 1993, 74, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.G. Compos Analysis, Version 6.3 Pro [Software]; Smith Ecology Ltd.: Abergavenny, UK, 2015.

- Baker, L.E.; Hoffman, M.T. Managing variability: Herding strategies in communal rangelands of semiarid Namaqualand, South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batdelger, G.; Oborny, B.; Batjav, B.; Molnár, Z. The relevance of traditional knowledge for modern landscape management: Comparing past and current herding practices in Mongolia. People Nat. 2025, 7, 1056–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, A.; Fedele, V.; Di Grigoli, A. Grazing management of dairy goats on Mediterranean herbaceous pastures. In Dairy Goats Feeding and Nutrition; Cannas, A., Pulina, G., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jarne, A.; Usón, A.; Reiné, R. Predictive Production Models for Mountain Meadows: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, S. Rangelands at equilibrium and non-equilibrium: Recent developments in the debate. J. Arid Environ. 2005, 62, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rowaily, S.L.; El-Bana, M.I.; Al-Bakre, D.A.; Assaeed, A.M.; Hegazy, A.K.; Basharat Ali, M. Effects of open grazing and livestock exclusion on floristic composition and diversity in natural ecosystem of Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.J.; Schwilch, G.; Lauterburg, N.; Crittenden, S.; Tesfai, M.; Stolte, J.; Zdruli, P.; Zucca, C.; Petursdottir, T.; Evelpidou, N.; et al. Multifaceted Impacts of Sustainable Land Management in Drylands: A Review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janišová, M.; Škodová, I.; Magnes, M.; Iuga, A.; Biro, A.-S.; Ivașcu, C.M.; Ďuricová, V.; Buzhdygan, O.Y. Role of livestock and traditional management practices in maintaining high nature value grasslands. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 309, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyerges, A.E. Traditional pastoralism and patterns of range degradation. In Browse in Africa: The Current State If Knowledge; Le Houerou, H.N., Ed.; ILCA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1980; pp. 465–472. [Google Scholar]

- Baumont, R.; Prache, S.; Meuret, M.; Morand-Fehr, P. How forage characteristics influence behavior and intake in small ruminants: Review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 64, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldt, T.; Schlecht, E. Analysis of GPS trajectories to assess spatio-temporal differences in grazing patterns and land use preferences of domestic livestock in southwestern Madagascar. Pastoralism 2016, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.T.; Wilmot, M.G.; Alchin, M.; Masters, D.G. Preliminary indications that Merino sheep graze different areas on cooler days in the Southern Rangelands of Western Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2008, 48, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Johansen, K.; Jin, B.; Sun, G.; McCade, M.F. Seasonal movement behavior of domestic goats in response to environmental variability and time of day using Hidden Markov Models. Mov. Ecol. 2025, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khaza’leh, J.; Reiber, C.; Al Baqain, R.; Valle Zárate, A. A comparative economic analysis of goat production systems in Jordan with an emphasis on water use. Livestock Res. Rural Dev. 2015, 27, 81. Available online: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd27/5/khaz27081.html (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- Molle, G.; Decandia, M.; Ligios, S.; Fois, N.; Treacher, T.T.; Sitzia, M. Grazing management and stocking rate with particular reference to the Mediterranean environment. In Dairy Sheep Nutrition; Pulina, G., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2004; pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hostiou, N.; Dedieu, B. A method for assessing work productivity and flexibility in livestock farms. Animal 2012, 6, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakopoulos, L.; Tsimpoukas, K.; Vallerand, F. The basic characteristics of the evolution of dairy livestock production in Greece (period 1961–1997). In Report of the FAIR3—CT96—1893 Programme Title: Diversification and Reorganization of Activities Related to Animal Production in LFA’s; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalidi, K.M.; Alassaf, A.A.; Al-Shudiefat, M.F.; Al-Tabini, R.J. Economic performance of small ruminant production in a protected area: A case study from Tell Ar-Rumman, a Mediterranean ecosystem in Jordan. Agric. Econ. 2018, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, A.; Ragkos, A.; Theodoridis, A.; Skordos, D.; Parissi, Z.; Abraham, E. Evaluation of the Contribution of Pastures on the Economic Sustainability of Small Ruminant Farms in a Typical Greek Area. Agronomy 2021, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachica, M.; Prieto, C.; Aguilera, J.F. The energy costs of walking on the level and on negative and positive slopes in the Granadina goat (Capra hircus). Br. J. Nutr. 1997, 77, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P.D.; McPeak, J.G. Resilience and Pastoralism in Africa South of the Sahara, with a Particular Focus on the Horn of Africa and the Sahel, West Africa; 2020 Conference Paper 9; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Manousidis, T.; Malesios, C.; Kyriazopoulos, A.P.; Parissi, Z.M.; Abraham, E.M.; Abas, Z. A modeling approach for estimating seasonal dietary preferences of goats in a Mediterranean Quercus frainetto–Juniperus oxycedrus woodland. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 177, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.D.; McPeak, J.G.; Ayantunde, A. The role of livestock mobility in the livelihood strategies of rural peoples in semi-arid West Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kababya, D.; Perevolotsky, A.; Bruckental, I.; Landau, S. Selection of diets by dual-purpose Mamber goats in Mediterranean woodland. J. Agric. Sci. 1998, 131, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, T.A.; Landau, S.Y.; Ungar, E.D.; Perevolotsky, A.; Dvash, L.; Muklada, H.; Kababya, D.; Walker, J.W. Foraging selectivity of three goat breeds in a Mediterranean shrubland. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 102, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmellouk, I. Characterization of Grazing Patterns: Analyzing a Goat Herd Dynamics in Montesinho Natural Park. Master’s Thesis, School of Agriculture of Bragança, Bragança, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.