Abstract

Although sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) is gaining importance in West Africa, it remains uncertain whether the research is adequately advanced to support the promotion of this crop in the region. Consequently, this systematic review of 125 articles provides a detailed overview of studies focused on sweet potatoes in West Africa. The paper explores various bibliometrics, the research geographic spread, and the topics discussed (e.g., food security and nutrition, climate resilience, livelihoods). The study indicates that sweet potato has the potential to address multiple issues in West Africa, including food and nutrition insecurity (especially micronutrient deficiencies, e.g., vitamin A) as well as poverty. However, it also reveals significant research gaps in terms of geographical and thematic areas. From a geographical perspective, research is primarily conducted in Nigeria and Ghana. From a thematic perspective, there are deficiencies in areas like economics and social sciences, applications in animal husbandry, marketing, use of leaves, irrigation methods, and impacts on climate resilience and livelihoods. There is a pressing need for collaborative research and knowledge exchange among nations to fully realize the potential of sweet potato and develop its value chains to contribute to sustainable socio-economic development across West Africa.

1. Introduction

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), also known as sweetpotato, is a dicotyledonous plant that is part of the Convolvulaceae family [1]. Among the roughly 1000 species in the Convolvulaceae family, I. batatas stands out as the only significantly important crop. The genus Ipomoea, which includes the sweet potato, also features various garden flowers commonly referred to as morning glories. Some organizations and researchers recommend writing the name as one word—sweetpotato—to highlight its genetic distinction from both common potatoes and yams (Dioscorea), thereby reducing confusion about its classification as a type of common potato [2,3]. Currently, the two-word format is predominantly used [4]. The large, sweet-tasting tuberous roots of the sweet potato serve as a root vegetable [5,6]. Though they share the same order, Solanales, I. batatas is only vaguely related to Solanum tuberosum, the common potato. However, though sweet potato and common potato are not closely related botanically, they do have a common linguistic origin [7].

The sweet potato originates from the tropical areas of the Americas [8,9]. Sweet potatoes became a popular food crop in the Pacific Ocean islands [10], South India, Uganda, and various other African nations [11]. Nowadays, they are grown in temperate areas where there is enough water [12]. The plant cannot withstand frost. It thrives best at a usual temperature of 24 °C, requiring ample sunlight. An annual rainfall of 750–1000 mm is deemed ideal. Sweet potatoes are vulnerable to drought during the tuber formation phase and are not resilient to waterlogged conditions [13]. Tubers are typically cured after harvest to enhance their storage life, flavour, and nutritional value, as well as to allow the healing of skin wounds [14,15].

The plant is a perennial vine that is herbaceous. The edible tuberous root is elongated and tapering, characterized by a smooth skin that comes in various colours, including beige, brown, orange, purple, red, and yellow. The flesh colour can vary from beige to orange, pink, purple, red, violet, white, and yellow. Cultivars of sweet potatoes that have clear-coloured flesh (e.g., white, pale-yellow) tend to be less sweet and moist compared to those with dark-coloured flesh (e.g., red, pink, orange) [3]. The time it takes for tuberous roots to mature varies between two to nine months based on the cultivar and environmental conditions. Short-cycle varieties can be cultivated as seasonal summer crops in temperate regions. Sweet potatoes are primarily propagated through cuttings from stems or roots, or by adventitious shoots (i.e., “slips”) emerging from tubers during their storage period. Generally, sweet potato seeds are utilized solely for breeding purposes [16].

The crop is relatively simple to plant since it is propagated using vine cuttings instead of seeds. It thrives in various agricultural environments and faces minimal natural threats, so the use of pesticides is required infrequently. Sweet potato is affected by relatively few pests and diseases. It is affected by the sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus (SPCSV) and sweet potato feathery mottle virus [17,18]. Sweet potato is also impacted by several species of Phytophthora, including P. carotovorum, P. odoriferum, and P. wasabiae [19]. It can be cultivated in different types of soil but prefers well-drained, light-to-medium-textured soils [5]. Although sweet potatoes can flourish in poor soil with minimal fertilization [20,21], they are highly susceptible to aluminum toxicity [5]. Additionally, because the swiftly growing vines overshadow weeds, there is minimal need for weeding.

In 2020, the worldwide production of sweet potatoes reached approximately 89 million tons, with China accounting for 55% of the total global production. The next largest producers were Malawi, Tanzania, and Nigeria [22]. In 2022, the list of the top 20 world countries in terms of production was still topped by China with more than 46 million tons [22]. However, the top 20 list featured many African countries such as Malawi, Tanzania, Nigeria, Angola, Rwanda, Uganda, Madagascar, Ethiopia, Burundi, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Cameroon. Meanwhile, the average yield ranged from just 1752.3 kg/ha in Chad to 44,317.9 kg/ha in Congo (Table A1).

According to FAO [23], sweet potato is among the most productive crops in terms of land use, generating around 70,000 kcal per hectare per day. The sweet potato’s tuberous roots are the most significant product. In certain tropical regions, these tubers serve as a primary food source. Cooking the tubers before eating enhances their nutritional value and digestibility, even though they can be consumed raw [24]. Cooked sweet potato (baked with skin) is rich in water and carbohydrates and has low protein and minimal fat contents. Sweet potatoes offer lower edible energy and protein per weight compared to cereals like rice, wheat, and maize; however, they are more nutrient-dense than these grains [25]. Sweet potatoes are an excellent source of vitamins like A, C, and B6. They also serve as a moderate source of potassium. Sweet potato varieties that feature dark-coloured flesh have higher contents of beta-carotene, converted into vitamin A during digestion, compared to those with lighter-coloured flesh. The cultivation of sweet potato is being promoted in Africa due to the significant issue of vitamin A deficiency. Sun-dried sweet potato tubers serve as a fundamental food for individuals in Uganda [26]. Sweet potato is a popular crop and food in different countries across the globe, such as Papua New Guinea [27], Kenya [28], Egypt [29], Ethiopia [30], the United States [31,32,33,34], and Italy [35].

Furthermore, its leaves are consumable and can be cooked similarly to spinach [36]. The young leaves are commonly eaten as a vegetable in countries of West Africa (e.g., Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone), in addition to being popular in Uganda, East Africa [26]. As reported by the FAO [37], leaves and shoots provide rich sources of vitamins (e.g., A, C, B2). Mature leaves can be utilized as feed for livestock [26].

Sweet potato also has some industrial applications. In Southern America, the liquid extracted from red sweet potato tubers was traditionally mixed with lime juice to create a dye; adjusting the juice ratios allows for the achievement of various shades ranging from pink to black [38]. Additionally, the colour derived from purple sweet potatoes is utilized as a natural food colouring [39]. Sweet potato has been processed in several formulations and products with a variety of ingredients [40,41].

Despite its huge potential, sweet potato is often regarded as an underutilized crop. While various African nations are involved in its production, it remains unclear whether the research is sufficiently advanced to support the crop’s promotion, especially in West Africa. Previous reviews on sweet potatoes have either become outdated or only partially addressed the topic from geographical and thematic perspectives (Table A2). Additionally, no comprehensive bibliometric or content analysis has been conducted for all of West Africa. This indicates a substantial gap in the research, as there has not been a recent systematic review focusing on sweet potatoes in the region. Therefore, this systematic review aims to provide an in-depth summary of research concerning sweet potatoes in West Africa. The article includes bibliometric metrics and examines the geographic spread of the studies. It also highlights the topics discussed in the academic literature related to sweet potatoes in West Africa, specifically regarding their potential role in sustainable development in terms of food and nutrition security, climate resilience, and livelihood.

2. Methods

This article covers the West Africa region (Figure 1). The systematic review [42,43] is based on a search conducted on the Web of Science Core Collection on 31 May 2024. The search utilized the subsequent query: (“Ipomoea batatas” OR “I. batatas” OR “sweet potato” OR sweetpotato OR batata) AND (Togo OR Senegal OR Sahel OR Nigeria OR Niger OR Mauritania OR Mali OR Liberia OR Guinea OR Ghana OR Gambia OR Burkina OR Benin OR “West* Africa” OR “Sierra Leone” OR “Ivory Coast” OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR “Côte d’Ivoire” OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Cabo Verde”). The search yielded 368 items. The process of selecting suitable publications was guided by the approach used by El Bilali et al. [44,45].

Figure 1.

West Africa region. Source: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing [46]. Stars refer to the main, capital cities.

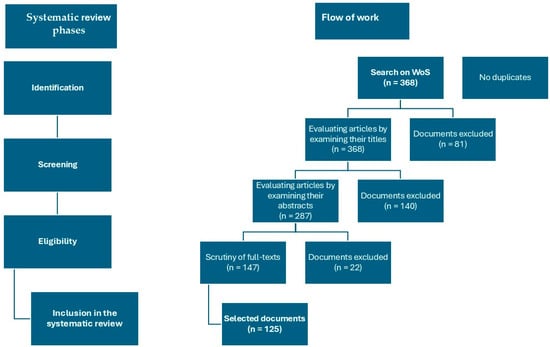

Figure 2 details the various steps involved in the selection process. In particular, three specific criteria were considered for eligibility: geographical relevance (i.e., the publication relates to West Africa or a West African nation), thematic relevance (i.e., the publication focuses on sweet potato), and document type (i.e., only original research papers, chapters, or conference papers were accepted, while editorials and reviews were eliminated). After reviewing the titles, 81 publications were removed because they did not concern West African nations. In particular, many documents refer to Papua New Guinea as well as Australia, Cameroon, Kenya, Malawi, and Uganda. Furthermore, 140 documents were discarded after examining their abstracts, as they failed to satisfy at least one of the inclusion criteria: 27 documents did not discuss sweet potato, 102 did not relate to West Africa or West African nations, and 11 lacked abstracts. Concerning geographical relevance, the term “Niger” is used in a few articles in reference to Aspergillus niger. Further articles refer to Papua New Guinea. Regarding the species, some articles mention taro, yam, cassava, and Frafra potato. Finally, 22 documents were removed following a comprehensive examination of their full texts, counting 9 reviews.

Figure 2.

Selection of the appropriate articles to be incorporated into the review regarding sweet potatoes in West Africa.

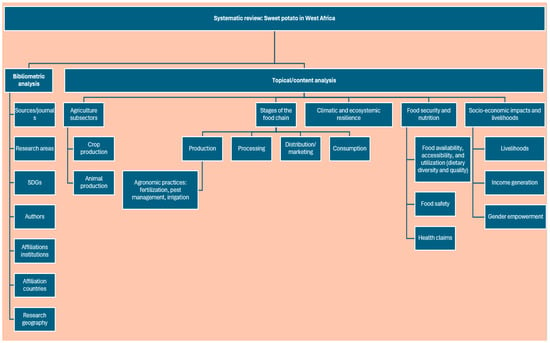

The analysis systematically reviewed a total of 125 documents (Table A3). This included 107 articles from journals and 18 papers from conferences. The analysis combines bibliometric and topical/content analyses (Figure 3). The evaluation of the selected documents commenced with an analysis of bibliographic metrics and the geographical distribution of studies in West Africa. Next, the identified articles were scrutinized for various topics, such as agriculture subsectors, food chain phases, and the role of sweet potatoes in promoting food security and good nutrition, supporting livelihoods, and enhancing climatic and ecosystemic resilience. All analyses followed the approach utilized for mapping research on moringa [45], roselle [47] and Bambara groundnut [44].

Figure 3.

Organization of the review.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bibliometrics of Research on Sweet Potato in West Africa

West Africa appears to have a marginal role in the scholarly literature regarding sweet potatoes, both in Africa and worldwide. A search performed on 31 May 2024 in WoS, without geographical filters [viz. “Ipomoea batatas” OR “I. batatas” OR “sweet potato” OR sweetpotato OR batata], yielded 11,318 records. Meanwhile, a similar search considering the whole African continent [viz. (“Ipomoea batatas” OR “I. batatas” OR “sweet potato” OR sweetpotato or batata) AND (Africa OR Algeria OR Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR “Burkina Faso” OR Burundi OR “Cabo Verde” OR “Cape Verde” OR Ethiopia OR Eswatini OR Eritrea OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR Congo OR Comoros OR Chad OR Cameroon OR “Ivory Coast” OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR “Côte d’Ivoire” OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR “Central African Republic” OR Zimbabwe OR Zambia OR Uganda OR Tunisia OR Togo OR Tanzania OR Swaziland OR Sudan OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR Rwanda OR Nigeria OR Niger OR Namibia OR Mozambique OR Morocco OR Mauritius OR Mauritania OR Mali OR Malawi OR Madagascar OR Libya OR Liberia OR Lesotho OR Guinea OR Kenya OR Ghana OR Gambia OR Gabon OR “South Sudan” OR “South Africa” OR “Sierra Leone” OR Somalia OR “São Tomé and Príncipe” OR “Guinea-Bissau”)] returned 1124 documents. In comparison to the 368 records found in the search related to sweet potatoes in West Africa, this suggests that West Africa represents only about 3.25% of the global literature potentially dealing with sweet potato. West Africa’s share of in the literature potentially dealing with sweet potatoes increased to 32.74% when focusing on Africa.

The first research article on sweet potatoes in West Africa indexed in WoS dates to 1991 [48]. Since then, the annual output of publications on sweet potatoes in Africa shows that interest has been variable and fluctuating. Between 1991 and 2024, the yearly article numbers shifted dramatically, ranging from zero in certain years (e.g., 1996, 1999, 2002, 2005, 2011) to just one in several others (e.g., 1991, 1994, 1995, 1997, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2013, 2014), with a peak of 12 publications in 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022. In 2023, 9 papers dealing with sweet potatoes in West Africa were published, indicating a possible reduction in interest (compared to 12 publications in 2022).

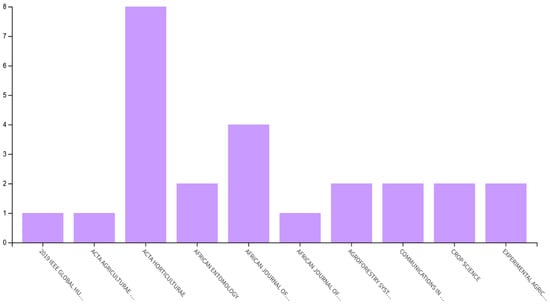

The compilation of sources and journals (Figure 4) is topped by Acta Horticulturae (8 articles, 6.40%), followed by the proceedings of the 9th Triennial African Potato Association Conference held on 30 June–4 July 2013, in Naivasha, Kenya (8 articles, 6.40%), and Tropical Agriculture (5 articles, 4.00%). Nevertheless, the 125 selected publications were distributed across 87 distinct sources and journals, suggesting that research on sweet potatoes in West Africa lacks a dedicated publication venue.

Figure 4.

Studies on sweet potato in West Africa–top ten journals and sources.

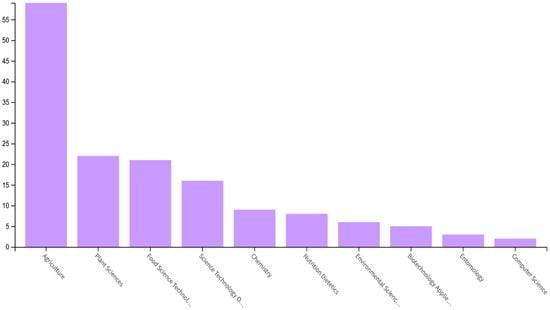

Most of the publications that meet the eligibility criteria fall within the research areas of Agriculture (62 publications, 49.60%), Plant Sciences (22 publications, 17.60%), and Food Science Technology (22 publications, 17.60%) (Figure 5). However, it is important to highlight that the chosen publications span over 28 research fields (comprising behavioural sciences, business economics, chemistry, computer science, development studies, ecology, engineering, entomology, forestry, geology, geography, meteorology, microbiology, nutrition dietetics, pediatrics), reflecting a multidisciplinary landscape of research. Nonetheless, it can be inferred that the primary focus of this research area is on biological sciences (e.g., agriculture, plant sciences, food science), with a restricted presence of economics and social sciences.

Figure 5.

Studies on sweet potato in West Africa—top ten research areas.

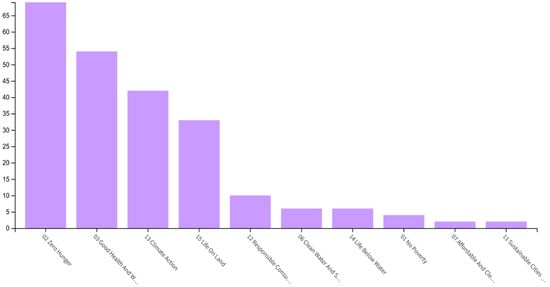

The extensive variety of sectors and fields addressed by the studies on sweet potatoes is clear in the SDGs they relate to (Figure 6). The articles examined in this review regarding sweet potatoes are linked to 11 SDGs, with the most prominent being 02 (67 documents, 53.60%), 03 (56 documents, 44.80%), 13 (45 documents, 36.00%), and 15 (34 documents, 27.20%). Other SDGs that are less significant include 12 (10 documents), 14 (8 documents), 06 (6 documents), 01 (5 documents), 07 and 11 (2 documents, each), and 09 (1 document).

Figure 6.

Studies on sweet potato in West Africa—main SDGs related with the considered studies.

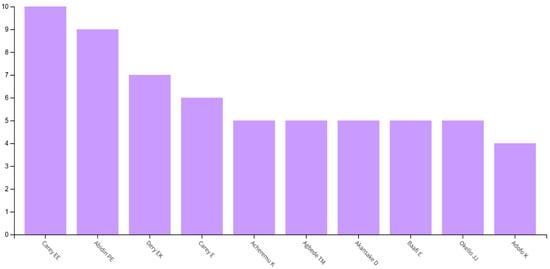

The analysis of bibliometric data regarding sweet potato research in West Africa indicates that the most notable and productive authors in this field are Edward E. Carey (Ghana), Putri Ernawati Abidin (Ghana), and Eric K. Dery (Ghana) (Figure 7). However, there is a lack of consistency within the field, as many authors have published only a limited number of articles. In fact, among the 506 scholars and researchers who contributed to the 125 selected publications, a significant 489 scholars (i.e., 96.64%) published two or fewer articles on sweet potatoes. This indicates that even those authors who concentrate on sweet potatoes do so sporadically instead of regularly, likely because of the lack of structured research initiatives, programmes, and projects focused on sweet potatoes in West Africa.

Figure 7.

Research on sweet potato in West Africa—top ten authors and scholars.

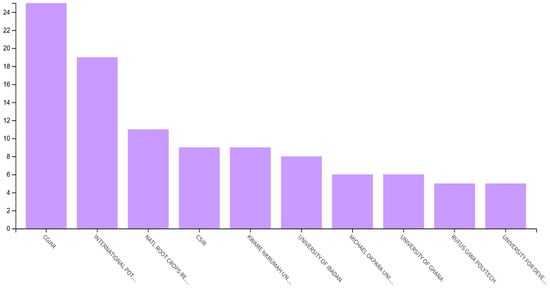

The 125 selected articles on sweet potato were written by researchers connected to 174 institutions and research centres. Leading the list of affiliated institutions (Figure 8) are international organizations like CGIAR (25 articles) and CIP (19 articles). Notable West African institutions are primarily located in Nigeria (National Root Crops Research Institute, University of Ibadan, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Adekunle Ajasin University, Landmark University, University of Benin) and Ghana (Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, University of Ghana, University of Cape Coast, University for Development Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology), and to a lesser extent in the Ivory Coast (Universite Felix Houphouet Boigny) and Benin (University of Parakou). Additionally, organizations engaged in sweet potato research in West Africa were found outside the region, including in France (CIRAD) and Sweden (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences).

Figure 8.

Studies on sweet potato in West Africa—top ten affiliations. CSIR: The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; CGIAR: Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research.

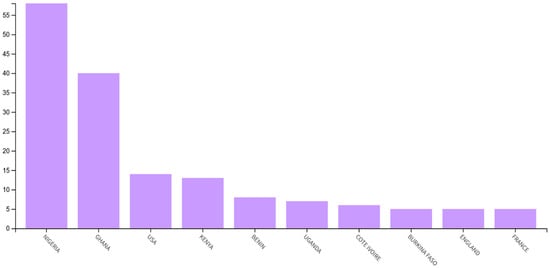

The findings concerning institutional affiliations correspond with those of the countries of affiliation (Figure 9). Indeed, the leading countries are Nigeria (60 articles, 48.00%) and Ghana (40 articles, 32.00%). Other notable West African countries in the research field are Benin (8 articles), the Ivory Coast (7 articles), Burkina Faso (6 articles), and Sierra Leone (4 articles). Furthermore, numerous authors are connected to institutions based beyond West Africa, in Africa (e.g., Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa, Kenya, Senegal, Cameroon), Europe (e.g., France, England, Germany, Sweden, Italy, Belgium), Asia (e.g., Malaysia, Syria, Bangladesh), North America (e.g., USA, Canada), Latin America (e.g., Peru), and Oceania (e.g., Australia). The 125 selected publications were authored by scholars and researchers based in 40 countries and regions.

Figure 9.

Studies on sweet potato in West Africa—top ten countries.

The analysis of the bibliographical data reveals that the primary sources of funding are outside West Africa and even Africa, specifically international foundations (viz. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) and research organizations (viz. CGIAR, International Potato Centre). Some studies have been funded through West African institutions, either national (e.g., CSIR Crops Research Institute Ghana, Tertiary Education Trust Fund Nigeria) or regional ones (e.g., CORAF). Further research activities have received funding from African institutions such as the African Union and the African Potato Association (APA). Moreover, funding has been provided by some European foundations (e.g., Agropolis Foundation) and agencies (e.g., Department for International Development of the UK). Consequently, the results underscore the insufficient domestic funding for sweet potato research in West Africa, potentially hindering the development of domestic research endeavours.

3.2. Geography of the Research on Sweet Potato in West Africa

Studies on sweet potatoes exhibit considerable variation throughout West Africa (Table 1). A handful of nations, including Nigeria and Ghana—which lead the affiliation rankings—have conducted most of the studies. In fact, Nigeria and Ghana account for almost three-quarters of all studies on sweet potatoes in West Africa. Nigeria tops the list with the highest number of studies on sweet potatoes (59 articles, representing 47.2% of the total), followed by Ghana (31 articles, 24.8%). The significant number of studies from Nigeria, due to its large and populous nature and it being one of the largest producers of sweet potatoes worldwide, is somewhat anticipated, while the research output of Ghana could suggest a noteworthy dynamism in its research landscape. Other countries in West Africa with notable contributions include Burkina Faso (6 articles), the Ivory Coast (5 articles), and Sierra Leone (6 articles). Conversely, many West African nations lack sufficient coverage in this research area. For example, some countries—including Cabo Verde and Senegal—have only produced one study on sweet potatoes. Additionally, about half of the West African nations (8 out of 16)—viz. Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Togo—have not been specifically studied concerning sweet potatoes, reflecting a considerable research deficiency in this domain.

There is a general deficiency of thorough research on sweet potatoes covering the entire West African region, with a few notable exceptions. For instance, Mourtala et al. [49] evaluated new hybrids of sweet potato under drought conditions in Niger and Nigeria. Adekambi et al. [50] tested whether the uptake of OFSP, rich in vitamin A, improved the level of dietary diversity in households in Ghana and Nigeria. The limited number of regional studies may suggest a lack of collaboration among West African nations concerning sweet potato research.

Table 1.

Geography of studies on sweet potato in West Africa.

Table 1.

Geography of studies on sweet potato in West Africa.

| Country or Region (Articles Number) * | Documents |

|---|---|

| Benin (3) | Ahoudou et al. [51]; Sanoussi et al. [52]; Sohindji et al. [53] |

| Burkina Faso (6) | Ouédraogo et al. [54]; Sawadogo et al. [55]; Somé et al. [56]; Some et al. [57]; Tibiri et al. [58]; Tibiri et al. [59] |

| Cabo Verde (1) | Nascimento [60] |

| Côte d’Ivoire/Ivory Coast (5) | Koffi et al. [61]; Kouassi et al. [62]; Mahyao et al. [63]; Jean Maurel et al. [64]; Tetchi et al. [65] |

| Gambia (0) | |

| Ghana (31) | Acheampong et al. [66]; Adekambi et al. [67]; Adom et al. [68]; Adu-Kwarteng et al. [69]; Akomeah et al. [70]; Amagloh et al. [71]; Amenyenu et al. [72]; Atuna et al. [73]; Atuna et al. [74]; Ayensu et al. [75]; Ayensu et al. [76]; Baafi et al. [77]; Baafi et al. [78]; Bonsi et al. [79]; Bonsi et al. [80]; Carey et al. [81]; Darko et al. [82]; Donkor et al. [83]; Dziedzoave et al. [84]; Etwire et al. [85]; Hormenoo et al. [86]; Kubuga et al. [87]; Lartey et al. [88]; Morrison and Twumasi [89]; Otoo et al. [90]; Quayson and Ayernor [91]; Sossah et al. [92]; Sugri et al. [93]; Swanckaert et al. [94]; Tortoe et al. [95]; Younge et al. [96] |

| Nigeria (59) | Adekiya et al. [97]; Adetola et al. [98]; Adeyonu et al. [99]; Agbede [100]; Agbede and Oyewumi [101]; Agbede and Oyewumi [102]; Agbede and Oyewumi [103]; Agbede et al. [104]; Aiyelaagbe and Jolaoso [105]; Aladesanwa and Adigun [106]; Alalade et al. [107]; Anikwe and Ubochi [108]; Anioke et al. [109]; Anuebunwa [110]; Anyaegbunam et al. [111]; Chinenye et al. [112]; Dania et al. [113]; Ebem et al. [114]; Ebeniro et al. [115]; Ejike et al. [116]; Ekwe et al. [117]; Etela et al. [118]; Farayola et al. [119]; Iheme et al. [120]; Just et al. [121]; Lagerkvist et al. [122]; Larbi et al. [123]; Lawal et al. [124]; Law-Ogbomo and Ikpefan [125]; Law-Ogbomo and Osaigbovo [126]; Mafulul et al. [127]; Meludu [128]; Nayan et al. [129]; Njoku et al. [130]; Nnam [131]; Nnam [132]; Nta et al. [133]; Nwinyi [134]; Nwokocha et al. [135]; Odebode [136]; Odebode et al. [137]; Ogbalu [138]; Ogbonna et al. [139]; Ohizua et al. [140]; Ojimelukwe et al. [141]; Okorie et al. [142]; Okpara et al. [143]; Okungbowa and Osagie [144]; Oloniyo et al. [145]; Olorunsogo et al. [146]; Oshunsanya [147]; Oshunsanya [148]; Oyeogbe et al. [149]; Oyinloye et al. [150]; Salau et al. [151]; Shourove et al. [152]; Winter et al. [153]; Yusuf et al. [154]; Zuofa and Tariah [155] |

| Senegal (1) | Thiam et al. [156] |

| Sierra Leone (6) | Alghali and Bockarie [157]; Fereno et al. [158]; Kamara and Lahai [159]; Karim et al. [48]; Rhodes [160]; Williams et al. [161] |

| Western Africa ** (7) | Adekambi et al. [50]—Ghana and Nigeria; Adekambi et al. [162]—Ghana and Nigeria; Dery et al. [163]—Ghana and Nigeria; Glato et al. [164]; Mourtala et al. [49]—Niger and Nigeria; Peters [165]—Burkina Faso, Ghana and Nigeria; Ssali et al. [166]—Ghana and Nigeria |

| Sub-Saharan Africa *** (6) | Abidin et al. [167]—Ghana and Malawi; Assefa et al. [168]—Ghana and Ethiopia; Feukam Nzudie et al. [169]; Moyo et al. [170]—Ghana and Uganda; Utoblo et al. [171]—Ghana and Malawi; Villordon et al. [172] |

* No article specifically addresses the following Western African countries: Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Togo and Niger. ** Contains articles that focus on at least two countries in West Africa. *** Contains articles that cover at least one country from another region in Africa outside of West Africa.

Further studies cover several sub-Saharan African countries, even from outside West Africa. For instance, Utoblo et al. [171] analyzed the good practises and challenges encountered in the implementation of gender-responsive breeding of sweet potato and dissemination of selected varieties in Ghana and Malawi. Feukam Nzudie et al. [169] modelled and forecasted losses of roots and tubers (e.g., cassava, potato, sweet potato, yam) and estimated the resulting water losses in sub-Saharan Africa. Villordon et al. [172] used GIS-based tools and consensus modelling approaches to explore the distribution of the germplasm of sweet potato in sub-Saharan Africa.

3.3. Agriculture Subsectors and Food Chain Stages

Regarding the agricultural subsectors, as expected, the majority of eligible studies concentrate on crop production, considering that I. batatas is a crop, with a few exceptions [117,118,123]. Etela et al. [118] investigated the effects of adding fresh sweet potato leaves to Guinea grass on milk yield in Bunaji and N’Dama cows during early lactation in Nigeria. Larbi et al. [123] analyzed the yields of fodder and tubers as well as the fodder quality of 18 varieties of sweet potato at various stages of maturity in Nigeria. Ekwe et al. [117] investigated the effects of sweet potato meal on the performance of weaner rabbits. This result may suggest that sweet potatoes are not typically utilized in animal nutrition/feeding or, alternatively, that there is a lack of studies on this topic in West Africa.

The production phase is significantly the most discussed part of the food chain, followed by processing and consumption; in contrast, intermediate stages, particularly marketing and distribution, are often neglected in scholarly research (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stages of the food chain.

The research on production encompasses several studies that explored, among others, the diversity of sweet potato cultivars/varieties and their performance across various nations, including Benin [52,53], Ghana [78,90,93,94], Niger [49], Nigeria [49,114], and Burkina Faso [57], as well as West Africa [164] and the whole of sub-Saharan Africa [172]. For instance, Ebem et al. [114] evaluated 41 genotypes of sweet potato in diverse Nigerian environments. Ejike et al. [116] analyzed the involvement of youth in the production of sweet potato in Abia State (Nigeria) and found that the main constraints relate to motivation, access to credit, and access to information from extension services.

A number of studies have examined the processing of sweet potatoes. For example, Meludu [128] shed light on the various strategies that can be deployed for the establishment of sweet potato’s cottage industry in Nigeria. The various processing and preparation methods include fermentation [154], boiling [62,141,170], frying [62,163,166], sun-drying [144], oven-drying [141], roasting [141], mashing [62], and stewing [62]. Kouassi et al. [62] point out that the main ways of preparing the roots of sweet potatoes in central and northern Ivory Coast are frying, boiling, mashing, and stewing. Referring to the production of sweet potato spari in southwest Nigeria, Odebode [136] state that “Processing methods include peeling, grating, pressing, sieving, drying and packaging” (p. 418). Sweet potatoes have been utilized in the production of flour [69,75,84,95,96,98,131,132,140,145,161], starch [65,135], biscuits [75], chips [112], muffins [158,161], bread [69,79], noodles [69,146], yoghurt [83], and Gari [74]. Referring to the sweet potato promotion programme in Ghana, Adu-Kwarteng et al. [69] pointed out that the analyzed genotypes have numerous potential uses and applications in the food sector; these applications encompass fufu flour, bread, pastries, French fries, gluten-free noodles, yoghurt filler, baby food, juices, and raw materials for breweries and various other industries. This shows that sweet potato has a huge industrial potential.

Meanwhile, there is a restricted amount of research concentrating on the marketing of sweet potato and its related products. For example, Anyaegbunam et al. [111] investigated market integration and difficulties related to sweet potato marketing in southeastern Nigeria; they found that the main difficulties in sweet potato marketing comprise the lack of credit and banking facilities, inappropriate market infrastructure and stalls, high cost of transportation, commodity bulkiness, and deficiency of storage facilities.

Regarding consumption, research has focused on sweet potato as an edible product and its possible health benefits. The majority of articles in this field investigate sweet potato’s role in food and nutrition security, with a particular focus on its contribution to addressing vitamin A deficiency. These studies encompass the utilization of sweet potatoes in the fortification of foods.

Some researchers take a broader perspective, looking at various stages of the food supply chain or value chain [81,141,161,165]. For instance, Ojimelukwe et al. [141] analyzed the effects of soil nutrient management methods (cf. production)—namely poultry manure, Agrolyser, and NPK—and preparation/cooking methods (cf. processing) on nutrient content and the phytochemical composition of OFSP in Umudike (Abia State, Nigeria). Williams et al. [161] evaluated the sensory quality characteristics of different muffins from sweet potato flours, thus addressing both processing and consumption. Carey et al. [81] delineated an integrated approach for the development and deployment of non- or low-sweet potato cultivars in Ghana that addresses aspects relating to production, processing, marketing, and consumption. Peters [165] provided an overview of the development of the value chain of sweet potato in West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, and Burkina Faso), spanning from production to consumption through marketing.

Sweet potatoes are cultivated in various agricultural systems, both through monocrop and intercropping methods, including agroforestry [48,105]. They have been intercropped with several crops, such as maize in Nigeria [129,149,155], eggplant in Nigeria [115], okra in Nigeria [130], and papaya in Nigeria [105]. This highlights the crop’s flexibility in intercropping across diverse environments and farming practises.

In terms of production, some research focuses on fertilization and pest control, while irrigation is typically overlooked (Table 3). Further agronomic practises tested also included foliage/shoot removal [72,134].

Table 3.

Agronomic practises explored in research related to sweet potato cultivation.

Typically, there is a scarcity of research focused on irrigation practises for sweet potatoes, with only a few notable exceptions. For example, Mourtala et al. [49] evaluated twenty-three hybrids of sweet potato under drought and irrigation conditions in four locations in Niger and two locations in Nigeria. Sawadogo et al. [55] used satellite remote sensing-derived indicators (e.g., crop water productivity) to assess the performance of irrigation of different crops, including sweet potatoes, in the Kou Valley Irrigation Scheme in Burkina Faso.

Research related to pest management encompasses various pests and diseases, such as sweet potato weevils (Cylas spp.) in Ghana [68] and Nigeria [114,133], Lepidopterous Acraea acerata in Nigeria [109,138], soft rot disease caused by Rhizopus in Nigeria [113], millipede (Bandeirenica caboverdus) in Cape Verde [60], SPFMV in Burkina Faso [58,59] and Ghana [92], SPCSV in Burkina Faso [58,59], CMV in Ghana [92], SPCFV in Ghana [92], SPCV in Ghana [92], SPLCV in Ghana [92] and Burkina Faso [59], SPMMV in Ghana [92], SPMSV in Ghana [92], and SPVG in Ghana [92]. For instance, Adom et al. [68] analyzed the susceptibility of seven Ghanaian improved varieties to the sweet potato weevil (Cylas spp.) in the coastal savanna zone of Ghana. Sossah et al. [92] assessed the incidence of various viruses in 20 accessions of sweet potato in Ghana. Furthermore, certain studies have addressed weed management in countries such as Ghana [86]. Sweet potato has also been used as an intercrop or a live mulch to control weeds, especially in Nigeria [106,110,129,155].

Numerous articles explore the fertilization of sweet potato as well as soil fertility management concerning this crop. Indeed, research on this topic has been conducted throughout West Africa in countries such as Nigeria [97,100,101,102,103,104,124,125,126,143], Ghana [73,82], and Sierra Leone [159]. For instance, Agbede and Oyewumi [103] examined the impacts of different levels of biochar and poultry manure on sweet potato growth and yield as well as of soil physical and chemical qualities in southwestern Nigeria. Darko et al. [82] assessed the effects of fertilizer application rates on the productivity of sweet potato in different agroecological zones in Ghana. Additionally, the application of sweet potato in intercropping is another approach to dealing with fertilization and soil fertility management.

Different parts of sweet potato, such as the tubers/roots and leaves, were the subjects of the selected research (Table A4). Depending on the area of interest, various parts of the plant have been investigated. Studies focusing on sweet potato as a leafy green primarily concentrate on the leaves. Conversely, research that involves the processing and examination of the properties of processed products generally focuses on tubers. However, some agronomy-related articles address the sweet potato plant as a whole. Additionally, certain studies explore several parts of the sweet potato simultaneously. This includes multiple investigations that examined the diversity of sweet potatoes and/or the performances of different varieties/cultivars/clones in various West African countries [52,53,57,78,90,93,94,114,164,172].

3.4. Climatic and Ecosystemic Resilience

Only some papers address the potential of sweet potatoes in tackling numerous environmental issues in Western Africa, including changing climate and degrading land.

Overall, the academic literature regarding sweet potatoes in Western Africa gives insufficient attention to climate change and climate variability. Some research has explored the relationship between sweet potato and climate change in Western Africa. For instance, Glato et al. [164] assessed the diversity of the species in West Africa by collecting samples from a region that stretches from coastal Togo to Sahelian Senegal, encompassing various climatic conditions; they concluded that the genetic diversity of sweet potatoes in West Africa is organized into multiple groups, with certain groups being found in very distinct climatic environments, such as those under a tropical humid climate or a Sahelian climate. Meanwhile, Feukam Nzudie et al. [169] modelled the effects of climate variables on losses of roots and tubers (e.g., cassava, potato, sweet potato, yam) as well as the resulting water losses in sub-Saharan Africa. They found that in 2025, the magnitude of root and tuber losses is expected to increase by 27.72% from 2013 levels for West Africa. This implies that water losses will also increase; so, measures aimed at preventing root and tuber losses will also lessen the pressure on available water resources. In this context of changing climate, it is important to pay particular attention to the storage of sweet potatoes; sand storage technology seems promising for drought-prone areas and can help mitigate the climate change effects [167].

A dearth of studies dealt with the drought tolerance of sweet potatoes in various Western African countries such as Niger [49] and Nigeria [49]. However, Mourtala et al. [49] claim that while Western Africa is a dry region, no drought-tolerant variety of sweet potato was registered. If this is confirmed, it implies that sweet potato is not particularly adapted to rainfed cultivation in arid and semi-arid regions of Western Africa, such as the Sahel region.

Likewise, as for climate change, the importance of sweet potatoes in mitigating land degradation has generally been neglected in the existing literature. However, some articles discuss its role in sustaining or improving soil fertility. It seems that sweet potato crop can be used as a soil conservation strategy [139] and can be employed in conservation agriculture [168]. Moreover, some sweet potato cultivars/genotypes have been adapted to different environments and agroecological zones [94,114]. Thus, sweet potato holds the potential to serve as a valuable resource in marginal agroecosystems. However, harvesting sweet potatoes can contribute to fertile topsoil loss and removal [148].

3.5. Food Security and Nutrition

Research shows that sweet potato has considerable potential to enhance food security and nutritional well-being in West Africa by improving food availability, accessibility, and dietary diversity and quality.

The existing literature on sweet potatoes in West Africa briefly addresses the aspect of food availability. Nevertheless, the limited studies available imply that sweet potato serves as a significant food source for households across West Africa. The presence of sweet potato and its derivatives is contingent upon crop yield. In this context, various studies indicate that sweet potato yield is influenced by factors such as cultivar/accession [49,57,62,68,78,82,90,94,101,114,124,142], harvesting and maturity stage [123], and agronomic techniques (e.g., fertilization/soil nutrient management, pest management, weeding, irrigation) [49,58,68,72,82,93,97,100,103,104,108,124,125,126,134,141,143]. In addition to yield, the market availability of sweet potatoes is also reliant on the effective management of postharvest and storage losses [62,68,73,133,167].

Although research on sweet potatoes in West Africa concerning food access has been limited, findings reveal that households with access to sweet potatoes experience better food security and nutrition, particularly among lower-income families. Iheme et al. [120] showed that the price of sweet potato increased dramatically in Nigeria during the COVID-19 lockdown, which negatively affected its financial accessibility and affordability for Nigerians. Sweet potato cultivation in the urban and peri-urban regions of countries, like the Ivory Coast [63], facilitates better access to this valuable nutrient source for city residents. Value addition increases the income of sweet potato farmers, as shown in Kwara State (Nigeria) [107], which can provide them with additional financial resources and improve their access to food. However, the impact of sweet potatoes on food security and food access is dependent on market access [107].

Most articles discussing food security in relation to sweet potatoes concentrate on their nutritional role in the population’s diets, with a focus on food utilization. Numerous authors emphasize the exceptional nutritional composition, quality, and profile of sweet potatoes [50,52,56,57,67,71,79,145,154,162] to support their promotion as a solution to addressing nutrition-related issues, especially micronutrient deficiencies. Apart from tubers, sweet potato leaves have also shown an interesting nutritional profile [71,80]. Sweet potato is abundant in vitamins, particularly vitamin A [56,145,154]. In this regard, substantial focus has been placed on orange-fleshed sweet potato, known for its high beta-carotene or pro-vitamin A content (Table 4). Interventions and projects using sweet potatoes, especially orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, to address malnutrition among the population have been reported in several West African countries such as Ghana [79,87,162], Senegal [156], the Ivory Coast [64], and Nigeria [98,121,122,162]. These regarded mainly women [156] and infants and children [64,98,121,122,156]. Dark sweet potato varieties also have a high iodine content [151]. The nutritional value and nutrient content of sweet potato, including its pro-vitamin A levels, can be influenced by various factors/variables such as cultivar/variety [56,57,84,95], agronomic and postharvest practises [72,73,81,102], and processing, cooking, and preparation techniques [141,154].

Table 4.

Research on orange-fleshed sweet potato in West Africa.

The incorporation of sweet potato in fortification/supplementation programmes in numerous West African nations [79,146] is attributed to its outstanding nutrient composition and nutritional profile. Sweet potato has been utilized as a dietary addition in flours such as cassava in Ghana [74,96], porridges from processed sorghum and Bambara groundnut in Nigeria [132], bread in Ghana [79], noodles in Nigeria [146], and biscuits in Ghana [75,76].

Ensuring food safety is crucial for optimizing food utilization. Some studies have indicated that sweet potatoes (tubers and leaves) and their derivatives may harbour heavy metals [127] and pesticide/herbicide residues [86,150], which could potentially threaten human health and wellness. Research revealing these potential health risks has been carried out in countries such as Nigeria [127,150] and Ghana [86].

A limited number of the selected articles address claims regarding the health advantages of sweet potatoes [61,64,88,152]. Koffi et al. [61] found that diet supplementation with the orange-fleshed sweet potato accelerates the healing of hard-to-heal wounds in the Ivory Coast. Jean Maurel et al. [64] argued that the diversification of food thanks to sweet potato has a positive effect on the prognostic inflammatory and nutritional index (PINI) among school-age children in the Ivory Coast. Lartey et al. [88] reported that sweet potato tubers are commonly used in Ghana in the management of erectile dysfunction. Meanwhile, Shourove et al. [152] found that the occurrence of anemia was lower among Nigerian children fed vegetables such as sweet potato, pumpkin, carrot, and squash.

There is no dedicated article that addresses the connection between food security and stability. However, it is essential to emphasize the role of sweet potatoes in sustaining the population during times of food shortages. This, in turn, can aid in maintaining the consistency of food supply despite the challenges posed by climate change. However, climate change can increase the losses of roots and tubers (e.g., potato, cassava, sweet potato, yam) in sub-Saharan Africa [169], which might jeopardize the stability of food production and supply. Furthermore, the instability of some cultivars [49] might determine the variation in yield and, consequently, production from one year to another. Meanwhile, Some et al. [57], referring to the breeding of sweet potato in Burkina Faso, postulated that “increased storage root yield improvement would be slow” (p. 69). Genetic instability can also affect the nutritional value and nutrient contents of sweet potato clones/cultivars [70].

3.6. Socio-Economic Impacts and Livelihoods

The literature regarding sweet potatoes in West Africa covers various social and economic aspects. The findings from the bibliometric analysis support the assumption that the predominant focus within this research area lies in biological and environmental sciences, while social sciences and economics have received inadequate attention. Nonetheless, the analysis of the scholarly works on sweet potatoes in Western Africa concerning the SDGs indicated that SDG 2 and SDG 03, which pertain to the socio-economic domain, are the most prominently addressed goals. Meanwhile, other SDGs related to socio-economic issues, such as SDG 01 (No Poverty) and SDG 05 (Gender Equality), have received only limited coverage. Some research indicates that sweet potatoes can have a beneficial effect on local communities, particularly among smallholders, by aiding in the generation of income, the empowerment of women, and the enhancement of rural livelihoods. Nevertheless, the number and scope of these studies are quite limited.

Sweet potato is viewed as a vital source of livelihood and income across numerous West African countries. In fact, some researchers consider sweet potatoes to hold substantial economic significance in various West African nations, including Ghana [93], Nigeria [111] and Ivory Coast [63]. Several studies have shown the profitability of sweet potato [63,93,139]. Considering both return on investments and benefit–cost ratio, several sweet potato varieties were found to be economically viable in northern Ghana [93]. Sweet potato was also profitable as a soil conservation strategy in Abia State, Nigeria [139]. The use of sweet potatoes as an intercrop or a live mulch with different crops, such as maize, was financially viable in Nigeria [106,110,155]; indeed, it contributed to weed control and suppression, thus reducing production costs and increasing the income of farmers. Sweet potatoes represent an important source of livelihood for youth; Ejike et al. [116] found that youths were highly involved in the production of sweet potatoes in Abia State, Nigeria. Furthermore, intercropping sweet potatoes with cereals can stabilize farmers’ incomes; Oyeogbe et al. [149] concluded that the intercropping of maize with sweet potato and/or cowpea in the tropical rainforest agroecosystem of Nigeria can meet the food, nutrition, and income stability of farmers. Etela et al. [118] posited that fresh sweet potato foliage can be utilized for the whole or partial replacement of costly cottonseed meal or dried brewers’ grains in the diets of lactating cows in Nigeria to save costs, thus increasing the income of cow breeders. Furthermore, sweet potatoes could offer prospects for diversifying income-generating endeavours and creating jobs through processing [69,83,107,128,137]. Alalade et al. [107] found that producers in Kwara State (Nigeria) engaged in value-adding activities had higher incomes from sweet potatoes than those that sold the raw produce at the farm gate.

The significance of sweet potatoes for poor individuals, including smallholders, is considerable. This crop is typically grown by small-scale and economically disadvantaged farmers. Sweet potato is mostly grown on small plots of land (less than 1 ha) in central and northern Ivory Coast [62] and western Nigeria [119]. Sweet potato’s relevance and versatility make it a good component of agricultural development projects and programmes, especially those addressing food insecurity and malnutrition [50,79,156].

Certain studies suggest that sweet potatoes may contribute to promoting gender empowerment. In fact, various analyses indicate that women are widely involved in the value chains (cultivation, processing, and marketing) of sweet potatoes and their products in several countries like the Ivory Coast [62,63] and Nigeria [136]. Kouassi et al. [62] found that women represent the majority of sweet potato producers (66%) in the central and northern Ivory Coast. Mahyao et al. [63] underscored that the market supply chains of sweet potato leaves in Yamoussoukro and Abidjan (Ivory Coast) are dominated by women (97.5% in Abidjan and 100% in Yamoussoukro). Studies addressing gender in relation to sweet potatoes have been performed in several Western African countries such as Ghana [66,75,80,85,171], Ivory Coast [62,63], and Nigeria [136]. They cover diverse topics such as participatory breeding [62,171] and agricultural communication and extension [85]. Utoblo et al. [171] posit that the application of gender-responsive breeding and variety dissemination practises resulted in the adoption and development of acceptable varieties of sweet potatoes (including orange-fleshed sweet potato) in Ghana and Malawi. Odebode [136] argues that the promotion of processed sweet potato products such as spari could not only contribute to food security but also economic empowerment among rural women in southwest Nigeria. However, Acheampong et al. [66] showed that the adoption of improved sweet potato varieties significantly increased farmers’ income in Ghana but underlined that men gained more advantages than women because they had better access to extension services, enhanced varieties, and more productive resources.

The development of sweet potato value chains holds the promise of addressing various issues and fostering long-term socio-economic development in Western Africa. Processing underutilized crops such as sweet potatoes can enhance producers’ income, bolster food security, and contribute to rural development.

4. Conclusions

West Africa appears to have a limited presence in the academic literature concerning sweet potatoes. Additionally, research focusing on sweet potatoes in West Africa has only emerged in recent years. The annual fluctuation in publication numbers suggests that interest in this crop varies over time. The field of research is multidisciplinary but predominantly revolves around biological sciences, with a scarce representation of economics and social sciences. The literature examined connects to 11 SDGs, with the most prominent being SDG 02 and SDG 03. The articles selected for analysis feature authors from 174 different research institutions and universities. Leading the list of affiliations are international organizations like CGIAR and CIP. Notable West African institutions are primarily located in Nigeria and Ghana, with lesser representation from the Ivory Coast and Benin. Furthermore, numerous authors are connected to institutions outside West Africa. A considerable share of funding for sweet potato research in West Africa comes from outside the region, particularly from international foundations (such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) and research organizations (like CGIAR and CIP). This underlines the scarcity of domestic funding within West Africa. Research on sweet potatoes varies greatly throughout Africa, with a handful of countries, mainly Nigeria and Ghana, conducting most of research; they collectively represent almost three-quarters of all sweet potato research in West Africa. In contrast, half of the West African countries (8 out of 16) were not the focus of any dedicated sweet potato research. Moreover, the limited number of regional studies may indicate a lack of collaboration among West African nations concerning sweet potatoes.

In terms of agricultural subsectors, the chosen papers concentrate on crop production. Production is overwhelmingly examined, followed by processing and consumption, while marketing and distribution often receive minimal attention in the academic literature. With regard to production, some studies explore fertilization and pest management, but irrigation is frequently neglected. Only a few articles indexed on WoS address the potential of sweet potatoes in tackling numerous environmental issues in West Africa, such as climate change and land degradation. Academic research suggests that sweet potatoes can play a role in guaranteeing food security and nutrition in Africa by improving food availability, enhancing food accessibility, and improving dietary quality. However, most of the articles selected that link sweet potatoes to food security primarily focus on their nutritional contributions, particularly highlighting food utilization and their role in mitigating vitamin A deficiencies. A limited number of selected studies address the health advantages of sweet potatoes. The body of literature surrounding sweet potatoes in West Africa pays scant attention to social and economic elements. Some research indicates that sweet potatoes can benefit local communities, especially smallholders, by aiding in income generation, rural livelihoods, and gender empowerment. Nevertheless, these studies are few in number and limited in scope.

Given the numerous validated benefits of the crop, it is essential to promote sweet potatoes in West Africa to confront the various developmental challenges the region encounters. As suggested by Peters [165], possible measures to enhance the sweet potato value chain in West Africa include the following: (i) the breeding or selection of high-yield varieties that meet farmers as well as market and consumer preferences; (ii) implementing optimal production and agronomic practises such as ridging and weeding techniques to lower labour requirements, applying suitable fertilization and pest management methods, and determining the most effective intercropping methods; and (iii) coordinating and organizing farmers to improve their access to market to minimize the expenses and time involved in individual marketing efforts. In this context, it is essential to conduct studies on sweet potato in West Africa to tackle the existing challenges and limitations hindering its promotion and development. Specifically, there is a necessity to enhance the understanding of the crop’s genetic diversity to support breeding programmes and refine production specifications, along with effective agronomic practises (such as fertilization, pest management, and irrigation) to be communicated and shared with producers/farmers. Research is also vital for creating acceptable and cost-effective processing/transformation methods while preserving the quality of sweet potato and complying with safety standards. Enhancements in both quality and safety would boost the marketing and consumption of sweet potato, particularly orange-fleshed varieties, which already enjoy a positive reputation among researchers, policymakers, and the general public.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.E.B., F.G., I.D.G., J.N., L.D., R.A.S., R.K.N., S.R.F.T., V.-M.R., Z.K., and F.A; methodology, H.E.B.; software, H.E.B.; validation, H.E.B.; formal analysis, H.E.B.; investigation, H.E.B.; resources, H.E.B.; data curation, H.E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.E.B., F.G., I.D.G., J.N., L.D., R.A.S., R.K.N., S.R.F.T., V.-M.R., Z.K., and F.A; writing—review and editing, H.E.B., F.G., I.D.G., J.N., L.D., R.A.S., R.K.N., S.R.F.T., V.-M.R., Z.K., and F.A; visualization, H.E.B.; project administration, H.E.B., L.D., J.N., F.G., and F.A.; funding acquisition, H.E.B., L.D., J.N., F.G., and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the DeSIRA initiative (Development Smart Innovation through Research in Agriculture) of the European Union (contribution agreement FOOD/2021/422-681).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the project SUSTLIVES (SUSTaining and improving local crop patrimony in Burkina Faso and Niger for better LIVes and EcoSystems—https://www.sustlives.eu).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APA | African Potato Association |

| CGIAR | Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research |

| CIP | International Potato Centre |

| CIRAD | Agricultural Research Centre for International Development |

| CMV | Cucumber mosaic virus |

| CORAF | West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research and Development |

| CSIR | Council of Scientific and Industrial Research |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| NUS | Neglected and Underutilised Species |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SLU | Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences |

| SPCFV | Sweet potato chlorotic fleck virus |

| SPCSV | Sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus |

| SPCV | Sweet potato collusive virus |

| SPLCV | Sweet potato leaf curl virus |

| SPMMV | Sweet potato mild mottle virus |

| SPMSV | Sweet potato mild speckling virus |

| SPVG | Sweet potato virus G |

| WoS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Production, area harvested, and yield of sweet potato in top 20 world countries and African countries, 2022.

Table A1.

Production, area harvested, and yield of sweet potato in top 20 world countries and African countries, 2022.

| Country | Production (t) | Area Harvested (ha) | Yield (kg/ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 20 world countries | China | 46,828,761.12 | 2,157,292 | 21,707.2 |

| Malawi | 8,051,118.37 | 335,783 | 23,977.1 | |

| Tanzania | 4,259,619.65 | 576,196 | 7392.7 | |

| Nigeria | 4,011,034.89 | 1508,514 | 2658.9 | |

| Angola | 1,873,002 | 189,378 | 9890.3 | |

| Rwanda | 1,372,745.21 | 189,435 | 7246.5 | |

| Uganda | 1,337,511.74 | 314,250 | 4256.2 | |

| India | 1,184,000 | 107,000 | 11,065.4 | |

| USA | 1,176,483 | 53,500 | 21,990.3 | |

| Madagascar | 1,132,742.12 | 133,334 | 8495.6 | |

| Ethiopia | 1,000,575.96 | 43,685 | 22,904.4 | |

| Viet Nam | 976,122.24 | 85,821 | 11,374 | |

| Indonesia | 875,000 | 47,444 | 18,443 | |

| Brazil | 847,100 | 58,229 | 14,547.7 | |

| Burundi | 807,860.51 | 71,685 | 11,269.5 | |

| Japan | 710,700 | 32,300 | 22,003.1 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 710,120.73 | 139,026 | 5107.8 | |

| Kenya | 650,000 | 47,468 | 13,693.5 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) | 591,101 | 117,919 | 5012.8 | |

| Cameroon | 579,883.47 | 89,010 | 6514.8 | |

| Other African countries | Mozambique | 510,238 | 10,597 | 5340.4 |

| Egypt | 508,314.04 | 69 | 16,855.8 | |

| Mali | 452,193 | 9880 | 11,698.2 | |

| Guinea | 384,052.51 | 195 | 14,369.2 | |

| Sierra Leone | 286,118.06 | 31,984 | 6816.4 | |

| Sudan | 266,986.71 | 2250 | 4698.8 | |

| Niger | 233,696.64 | 1278 | 7190.7 | |

| Chad | 218,015 | 33,489 | 1752.3 | |

| Ghana | 142,671.37 | 14,775 | 34,404.2 | |

| Zambia | 132,442.12 | 19,218 | 5398.7 | |

| Burkina Faso | 115,579.98 | 1336 | 1870.1 | |

| Senegal | 110,600 | 2015 | 1943.1 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 103,749.32 | 78,340 | 1821.2 | |

| South Africa | 87,647 | 73,153 | 5250 | |

| Zimbabwe | 62,792.59 | 8155 | 4995.7 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 58,684.14 | 2187 | 11,154.1 | |

| Benin | 56,589.62 | 30,359 | 14,894.9 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 40,738.15 | 2782 | 1892.4 | |

| Liberia | 24,393.55 | 115 | 15,295.7 | |

| Morocco | 11,710 | 560 | 20,910.7 | |

| Comoros | 10,572.29 | 83,646 | 6100 | |

| Togo | 9919 | 7376 | 31,682.6 | |

| Congo | 9190.5 | 2496 | 44,317.9 | |

| Somalia | 8655.65 | 34,563 | 8278.1 | |

| Mauritania | 5264.75 | 873 | 9917.9 | |

| Gabon | 3915.14 | 33,008 | 2655.3 | |

| Cabo Verde | 2802 | -- | -- | |

| Eswatini | 2498.99 | 34,790 | 7674.3 | |

| Mauritius | 1759 | 2738 | 3622.7 | |

| Botswana | 1169.12 | 39,684 | 3337.4 |

Source: FAO [22].

Table A2.

Earlier reviews dealing partially with sweet potatoes in West Africa retrieved from the Web of Science database.

Table A2.

Earlier reviews dealing partially with sweet potatoes in West Africa retrieved from the Web of Science database.

| Review | Publication Date | Review Type | Geographical Coverage | Thematic Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Howeler et al. [173] | October 1993 | Narrative | Tropics | Tillage systems for root and tuber crops |

| Alegbejo [174] | 2000 | Narrative | Nigeria | Plant viruses transmitted by whiteflies |

| Ohimain [175] | June 2013 | Narrative | Nigeria | Biofuel policy |

| De Moura et al. [176] | 2015 | Narrative | Africa | Provitamin A carotenoids retention in biofortified staple crops (cassava, maize, and sweet potato) |

| McEwan et al. [177] | 2015 | Narrative | Sub-Saharan Africa | Local seed systems |

| Carey et al. [178] | March 2021 | Narrative | West Africa | Frying quality |

| Mulongo et al. [179] | June 2021 | Narrative | Sub-Sahara Africa | Scaling-up orange-fleshed sweet potato |

| Samuel et al. [180] | March 2024 | Systematic | Global | Farmers’ adoption of biofortified crops (e.g., banana, cassava, rice and sweet potato) |

| Neela and Fanta [181] | June 2019 | Narrative | Sub-Sahara Africa | Nutritional content of orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP) and the approach to managing vitamin A deficiency |

Table A3.

Articles dealing with sweet potatoes in Western Africa.

Table A3.

Articles dealing with sweet potatoes in Western Africa.

| Year | Number of Documents | References |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 * | 6 | Acheampong et al. [66]; Ejike et al. [116]; Kouassi et al. [62]; Lartey et al. [88]; Sugri et al. [93]; Utoblo et al. [171] |

| 2023 | 9 | Adekambi et al. [162]; Agbede and Oyewumi [103]; Ahoudou et al. [51]; Etwire et al. [85]; Koffi et al. [61]; Kubuga et al. [87]; Mourtala et al. [49]; Olorunsogo et al. [146]; Sohindji et al. [53] |

| 2022 | 12 | Adekiya et al. [97]; Agbede and Oyewumi [101]; Agbede and Oyewumi [102]; Agbede et al. [104]; Chinenye et al. [112]; Dania et al. [113]; Iheme et al. [120]; Just et al. [121]; Mafulul et al. [127]; Shourove et al. [152]; Thiam et al. [156]; Younge et al. [96] |

| 2021 | 12 | Adu-Kwarteng et al. [69]; Atuna et al. [74]; Dery et al. [163]; Ebem et al. [114]; Hormenoo et al. [86]; Jean Maurel et al. [64]; Moyo et al. [170]; Ojimelukwe et al. [141]; Oloniyo et al. [145]; Oyeogbe et al. [149]; Oyinloye et al. [150]; Ssali et al. [166] |

| 2020 | 12 | Adekambi et al. [50]; Adekambi et al. [67]; Adetola et al. [98]; Ayensu et al. [76]; Baafi et al. [78]; Darko et al. [82]; Donkor et al. [83]; Feukam Nzudie et al. [169]; Nayan et al. [129]; Sawadogo et al. [55]; Swanckaert et al. [94]; Tibiri et al. [59] |

| 2019 | 12 | Abidin et al. [167]; Adeyonu et al. [99]; Adom et al. [68]; Akomeah et al. [70]; Alalade et al. [107]; Assefa et al. [168]; Ayensu et al. [75]; Carey et al. [81]; Fereno et al. [158]; Law-Ogbomo and Ikpefan [125]; Law-Ogbomo and Osaigbovo [126]; Tibiri et al. [58] |

| 2018 | 3 | Atuna et al. [73]; Lagerkvist et al. [122]; Nta et al. [133] |

| 2017 | 6 | Amagloh et al. [71]; Baafi et al. [77]; Glato et al. [164]; Ohizua et al. [140]; Sanoussi et al. [52]; Tortoe et al. [95] |

| 2016 | 4 | Bonsi et al. [79]; Okorie et al. [142]; Oshunsanya [148]; Yusuf et al. [154] |

| 2015 | 9 | Anyaegbunam et al. [111]; Ebeniro et al. [115]; Ekwe et al. [117]; Farayola et al. [119]; Lawal et al. [124]; Peters [165]; Some et al. [57]; Sossah et al. [92]; Williams et al. [161] |

| 2014 | 1 | Nwokocha et al. [135] |

| 2013 | 1 | Oshunsanya [147] |

| 2012 | 2 | Ouédraogo et al. [54]; Nascimento [60] |

| 2010 | 3 | Agbede [100]; Dziedzoave et al. [84]; Morrison and Twumasi [89] |

| 2009 | 5 | Etela et al. [118]; Mahyao et al. [63]; Meludu [128]; Okpara et al. [143]; Okungbowa and Osagie [144] |

| 2008 | 4 | Aladesanwa and Adigun [106]; Odebode [136]; Odebode et al. [137]; Salau et al. [151] |

| 2007 | 6 | Anikwe and Ubochi [108]; Larbi et al. [123]; Njoku et al. [130]; Ogbonna et al. [139]; Quayson and Ayernor [91]; Tetchi et al. [65] |

| 2006 | 1 | Villordon et al. [172] |

| 2004 | 1 | Somé et al. [56] |

| 2003 | 1 | Rhodes [160] |

| 2001 | 2 | Ogbalu [138]; Nnam [132] |

| 2000 | 2 | Anuebunwa [110]; Nnam [131] |

| 1998 | 3 | Amenyenu et al. [72]; Bonsi et al. [80]; Otoo et al. [90] |

| 1997 | 1 | Kamara and Lahai [159] |

| 1995 | 1 | Anioke et al. [109] |

| 1994 | 1 | Alghali and Bockarie [157] |

| 1992 | 4 | Aiyelaagbe and Jolaoso [105]; Nwinyi [134]; Winter et al. [153]; Zuofa and Tariah [155] |

| 1991 | 1 | Karim et al. [48] |

* As of 31 May 2024.

Table A4.

Parts of sweet potatoes addressed in the selected documents.

Table A4.

Parts of sweet potatoes addressed in the selected documents.

| Sweet Potato Part * | Articles |

|---|---|

| Roots/Tubers | Abidin et al. [167]; Acheampong et al. [66]; Adekambi et al. [162]; Adekambi et al. [67]; Adekiya et al. [97]; Adetola et al. [98]; Adeyonu et al. [99]; Adom et al. [68]; Adu-Kwarteng et al. [69]; Agbede [100]; Agbede and Oyewumi [101]; Agbede and Oyewumi [102]; Agbede et al. [104]; Ahoudou et al. [51]; Alalade et al. [107]; Amenyenu et al. [72]; Anikwe and Ubochi [108]; Anyaegbunam et al. [111]; Atuna et al. [73]; Atuna et al. [74]; Ayensu et al. [75]; Baafi et al. [78]; Bonsi et al. [79]; Bonsi et al. [80]; Carey et al. [81]; Chinenye et al. [112]; Darko et al. [82]; Dery et al. [163]; Dziedzoave et al. [84]; Ebem et al. [114]; Ebeniro et al. [115]; Ekwe et al. [117]; Etwire et al. [85]; Fereno et al. [158]; Feukam Nzudie et al. [169]; Iheme et al. [120]; Just et al. [121]; Kamara and Lahai [159]; Koffi et al. [61]; Kouassi et al. [62]; Kubuga et al. [87]; Lagerkvist et al. [122]; Larbi et al. [123]; Lartey et al. [88]; Lawal et al. [124]; Law-Ogbomo and Osaigbovo [126]; Jean Maurel et al. [64]; Moyo et al. [170]; Nascimento [60]; Njoku et al. [130]; Nnam [131]; Nnam [132]; Nta et al. [133]; Nwinyi [134]; Nwokocha et al. [135]; Odebode [136]; Odebode et al. [137]; Ohizua et al. [140]; Ojimelukwe et al. [141]; Okorie et al. [142]; Okpara et al. [143]; Okungbowa and Osagie [144]; Oloniyo et al. [145]; Oshunsanya [147]; Oshunsanya [148]; Otoo et al. [90]; Ouédraogo et al. [54]; Peters [165]; Quayson and Ayernor [91]; Salau et al. [151]; Sanoussi et al. [52]; Shourove et al. [152]; Somé et al. [56]; Some et al. [57]; Ssali et al. [166]; Sugri et al. [93]; Swanckaert et al. [94]; Tetchi et al. [65]; Thiam et al. [156]; Tortoe et al. [95]; Williams et al. [161]; Younge et al. [96]; Yusuf et al. [154] |

| Leaves | Agbede and Oyewumi [102]; Amagloh et al. [71]; Amenyenu et al. [72]; Bonsi et al. [80]; Etela et al. [118]; Larbi et al. [123]; Law-Ogbomo and Osaigbovo [126]; Mahyao et al. [63]; Morrison and Twumasi [89]; Nwinyi [134] |

| Whole plant | Adekambi et al. [50]; Adekiya et al. [97]; Adom et al. [68]; Agbede [100]; Agbede and Oyewumi [101]; Agbede and Oyewumi [102]; Agbede and Oyewumi [103]; Agbede et al. [104]; Ahoudou et al. [51]; Aiyelaagbe and Jolaoso [105]; Akomeah et al. [70]; Aladesanwa and Adigun [106]; Alghali and Bockarie [157]; Amenyenu et al. [72]; Anikwe and Ubochi [108]; Anuebunwa [110]; Assefa et al. [168]; Atuna et al. [73]; Baafi et al. [78]; Bonsi et al. [80]; Carey et al. [81]; Darko et al. [82]; Ebem et al. [114]; Ebeniro et al. [115]; Ejike et al. [116]; Etwire et al. [85]; Glato et al. [164]; Hormenoo et al. [86]; Kamara and Lahai [159]; Karim et al. [48]; Kouassi et al. [62]; Larbi et al. [123]; Lawal et al. [124]; Law-Ogbomo and Ikpefan [125]; Law-Ogbomo and Osaigbovo [126]; Mourtala et al. [49]; Nayan et al. [129]; Njoku et al. [130]; Nwinyi [134]; Ogbalu [138]; Ogbonna et al. [139]; Ojimelukwe et al. [141]; Okorie et al. [142]; Okpara et al. [143]; Otoo et al. [90]; Oyeogbe et al. [149]; Sanoussi et al. [52]; Sawadogo et al. [55]; Sohindji et al. [53]; Some et al. [57]; Sossah et al. [92]; Sugri et al. [93]; Swanckaert et al. [94]; Tibiri et al. [58]; Tibiri et al. [59]; Utoblo et al. [171]; Villordon et al. [172]; Zuofa and Tariah [155] |

* Some documents deal with different parts of sweet potato.

References

- NatureServe. Ipomoea Batatas. Available online: https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.149769/Ipomoea_batatas (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- International Potato Center. Sweetpotato: One Word or Two? Available online: https://cipotato.org/research/sweet-potato/sweetpotato-one-word-or-two/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Loebenstein, G.; Thottappilly, G. The Sweetpotato; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- University of California. What Is a Sweetpotato? UC Agriculture and Natural Resources: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Woolfe, J.A. Sweet Potato: An Untapped Food Resource; Cambridge University Press (CUP) and the International Potato Center (CIP): Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Purseglove, J.W. Tropical Crops: D. Longman Scientific and Technical; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.A.A. Los Indigenismos En La Historia de Las Indias de Bartolomé de Las Casas; CSIC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, P.; Wells, T.; Wood, J.R.I.; Carruthers, T.; Anglin, N.L.; Jarret, R.L.; Scotland, R.W. Discovery and Characterization of Sweetpotato’s Closest Tetraploid Relative. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Oxford. Mystery of Sweetpotato Origin Uncovered, as Missing Link Plant Found by Oxford Research. Available online: https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2022-01-24-mystery-sweetpotato-origin-uncovered-missing-link-plant-found-oxford-research (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Denham, T. Ancient and Historic Dispersals of Sweet Potato in Oceania. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1982–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roullier, C.; Duputié, A.; Wennekes, P.; Benoit, L.; Fernández Bringas, V.M.; Rossel, G.; Tay, D.; McKey, D.; Lebot, V. Disentangling the Origins of Cultivated Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hair, S.K. Tropical Root and Tuber Crops. In Advances in New Crops; Janick, J., Simon, J.E., Eds.; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, P. Tropical Soils and Fertilizer Use; Longman Scientific and Technical Ltd.: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, K.L. Sweetpotato: Organic Production. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20110526063807/http:/attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/sweetpotato.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Cantwell, M.; Suslow, T. Sweet Potato—Recommendations for Maintaining Postharvest Quality. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20101105211935/http:/postharvest.ucdavis.edu/Produce/ProduceFacts/Veg/sweetpotato.shtml (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Chaney, C. Pollinating Sweet Potatoes. Available online: https://www.weekand.com/home-garden/article/pollinating-sweet-potatoes-18061087.php (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Karyeija, R.F.; Gibson, R.W.; Valkonen, J.P.T. The Significance of Sweet Potato Feathery Mottle Virus in Subsistence Sweet Potato Production in Africa. Plant Dis. 1998, 82, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuze, J.F.; Karyeija, R.F.; Gibson, R.W.; Valkonen, J.P.T. Comparisons of Coat Protein Gene Sequences Show That East African Isolates of Sweet Potato Feathery Mottle Virus Form a Genetically Distinct Group. Arch. Virol. 2000, 145, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkowski, A.O. The Changing Face of Bacterial Soft-Rot Diseases. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rós, A.B. Sistemas de preparo do solo para o cultivo da batata-doce. Bragantia 2017, 76, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hill, W.A.; Hortense, D.; Hahn, S.K.; Mulongoy, K.; Adeyeye, S.O. Sweet Potato Root and Biomass Production with and without Nitrogen Fertilization. Agron. J. 1990, 82, 1120–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT—Sweet Potatoes. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- FAO. Roots, Tubers, Plantains and Bananas in Human Nutrition—Nutritive Value. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/t0207e/T0207E04.htm (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- EnkiVeryWell. Can You Eat Sweet Potato Raw? Available online: https://www.enkiverywell.com/raw-sweet-potato.html (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Scott, G.J.; Best, R.; Rosegrant, M.; Bokanga, M. Roots and Tubers in the Global Food System: A Vision Statement to the Year 2020 (Including Annex); International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, P.E. Sweetpotato Breeding for Northeastern Uganda: Farmer Varieties, Farmer-Participatory Selection, and Stability of Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.; Hainzer, K.; Best, T.; Wemin, J.; Aris, L.; Bugajim, C. Commercial Sweetpotato Production in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1251, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nungo, R.A. Nutritious Kenyan Sweet Potato Recipes; Kenya Agricultural Research Institute: Kakamega, Kenya, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ElMeshad, S. The Batata Man—Egypt Independent. Available online: https://www.egyptindependent.com/batata-man/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Tsegaw, T.; Dechassa, N. Registration of Adu and Barkume: Improved Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas) Varieties for Eastern Ethiopia. East. Afr. J. Sci. 2008, 2, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associated Press. Ivey OKs Naming Sweet Potato as Alabama’s State Vegetable. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/alabama/articles/2021-04-17/ivey-oks-naming-sweet-potato-as-alabamas-state-vegetable (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- State of Louisiana. Louisiana State Legislature—Revised Statutes. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180728221322/https:/legis.la.gov/Legis/Law.aspx?d=181346 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- NCpedia. State Vegetable of North Carolina: Sweet Potato. Available online: https://www.ncpedia.org/symbols/vegetable (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- McLellan Plaisted, S. Sweet Potato “Fries” Are Not New. Available online: https://hearttohearthcookery.com/2011/10/02/sweet-potato-fries-are-not-new/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Mondo Agricolo Veneto. La Patata Americana Di Anguillara e Stroppare. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20100112083605/http:/www2.regione.veneto.it/videoinf/rurale/prodotti/pat_americana.htm (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Dyer, M.H. Potato Vine Plant Leaves: Are Sweet Potato Leaves Edible? Available online: https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/edible/vegetables/sweet-potato/are-sweet-potato-leaves-edible.htm (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- FAO. Sweet Potato—Leaflet No. 13. Available online: https://www.cd3wdproject.org/INPHO/VLIBRARY/NEW_ELSE/X5425E/X5425E0D.HTM (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Verrill, A.H.; Barrett, O.W. Foods America Gave the World: The Strange, Fascinating and Often Romantic Histories of Many Native American Food Plants, Their Origin, and Other Interesting and Curious Facts Concerning Them; L.C. Page & Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- American Chemical Society. Purple Sweet Potatoes among ‘New Naturals’ for Food and Beverage Colors. Available online: https://www.acs.org/pressroom/newsreleases/2013/september/purple-sweet-potatoes-among-new-naturals-for-food-and-beverage-colors.html (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Amagloh, F.K.; Coad, J. Sweetpotato-Based Formulation: An Alternative Food Blend for Complementary Feeding. In Proceedings of the 9th Triennial African Potato Association Conference, Naivasha, Kenya, 30 June–4 July 2013; Low, J., Nyongesa, M., Quinn, S., Parker, M., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2015; pp. 592–601. [Google Scholar]

- El Sheikha, A.F.; Ray, R.C. Potential Impacts of Bioprocessing of Sweet Potato: Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Kiebre, Z.; Nanema, R.K.; Dan Guimbo, I.; Rokka, V.-M.; Gonnella, M.; Tietiambou, S.R.F.; Dambo, L.; Nanema, J.; Grazioli, F.; et al. Mapping Research on Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) in Africa: Bibliometric, Geographical, and Topical Perspectives. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Dan Guimbo, I.; Nanema, R.K.; Falalou, H.; Kiebre, Z.; Rokka, V.-M.; Tietiambou, S.R.F.; Nanema, J.; Dambo, L.; Grazioli, F.; et al. Research on Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) in Africa. Plants 2024, 13, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]