Abstract

The research on cadmium (Cd) pollution remediation technologies in farmland is of great significance for ensuring food security. However, there is currently a lack of empirical research on the passivation effects of the related repair materials on alkaline farmland in arid regions. This study selected a typical experimental area in a dryland corn farmland in Ningxia, Northwest China. Field experiments were conducted on four typical remediation materials: mercapto clay minerals, sepiolite remediation materials, microbial inoculants, and bio-organic fertilizers. The effects of these four materials on the available cadmium in the soil, cadmium content in corn stems and leaves, and enrichment coefficients were analyzed. The results show that the four types of remediation fertilizers have significant differences in their effects on the available Cd content in the soil, with a reduction range of 3.33–60.94%. The order of the inhibitory effect from strong to weak is as follows: mercapto clay mineral passivation material, bio-organic fertilizer, sepiolite, and microbial inoculant. The cumulative distribution pattern of Cd in the organs of corn plants is leaf > stem > grain. It reduces the cadmium content in corn stems by 7.01–37.16% and reduces the cadmium content in corn leaves by 1.45–26.56%. Under the four types of remediation fertilizer treatments, the enrichment coefficients of corn stems and leaves all decreased. The enrichment coefficient of stems decreased by 3.78% to 29.42%, and the enrichment coefficient of leaves decreased by 3.41% to 31.92%. The mercapto clay minerals passivation material has the best effect on reducing the available cadmium in the soil of dryland corn in the arid areas of Northwest China and also has the best effect on inhibiting the absorption of cadmium by various organs of corn. It can be further verified in the field and promoted for application, providing support for the restoration of heavy metal pollution in farmland based on local conditions and differentiated measures.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of industrial and mining sectors, accelerated urbanization, and extensive use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, the soil environment has undergone prolonged degradation, particularly with heavy metal pollution becoming increasingly severe [1,2,3,4]. Recent studies indicate that heavy metal contamination in global farmland soils poses a threat to agricultural production and public health, among which cadmium (Cd) constitutes the highest proportion [5,6]. Classified as a human carcinogen, cadmium (Cd) is recognized as one of the most hazardous heavy metals to organisms due to its high toxicity [7,8]. Cadmium pollution in farmland adversely affects soil and surrounding ecosystems, inhibits plant growth, reduces crop yields which leads to agricultural and economic losses, and endangers human health through bioaccumulation in the food chain [9,10,11,12]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for efficient and feasible remediation technologies to address cadmium contamination in agricultural soils.

The content of available Cd in soil mainly refers to the Cd element that can be absorbed by the roots of crops during the growth period. It is also an important indicator for evaluating the toxicity of soil Cd pollution, as it is the part that crops can directly absorb and utilize, determining the degree of cadmium accumulation and toxicity in crops [13,14]. Currently, remediation of heavy metal contamination in farmland primarily relies on the application of immobilizing agents. The core principle involves reducing the bioavailability of heavy metals, thereby inhibiting their migration within the soil–plant system. Specifically for cadmium contamination, the key to remediation lies in lowering the concentration of available cadmium in the soil. This approach not only serves as the fundamental method for mitigating cadmium accumulation and toxicity in crops but also represents the common mechanism of action for various immobilizing agents. For a long time, research on the remediation of heavy metal pollution was mainly concentrated on acidic soil [15,16]. In recent years, the enrichment of cadmium in alkaline farmland and the consequent cadmium pollution in agricultural products have attracted increasing attention. However, in the treatment of heavy metal pollution in alkaline farmland soil, the research on stabilization repair materials is relatively lacking, especially the theoretical research and technological development for the treatment of cadmium pollution in alkaline farmland soil in arid areas, which are relatively weak [17]. Most alkaline soil is in an oxidized state, rich in silicon and calcium but lacking aluminum and iron, significantly different from acidic soil rich in iron and aluminum and lacking silicon and calcium [18]. The arid environment usually has less rainfall and a large evaporation rate, which aggravates the alkaline environment, hinders the migration and transformation of heavy metals, and leads to special migration and transformation behaviors of heavy metals [19,20]. Therefore, the stabilization materials used to fix cadmium in acidic soil have poor adaptability in arid alkaline soil and may lead to soil compaction and fertility decline [21,22]. In China, the research on stabilization repair materials for heavy metal Cd in farmland mainly comes from acidic rice fields in the south, and there are relatively few research cases in arid farmland corn fields in the northwest. Especially, there is a lack of comprehensive comparative studies on the repair effects of multiple types and multiple action principles of stabilization repair materials [23,24]. Therefore, screening suitable stabilization repair materials for cadmium in arid alkaline farmland is of great significance for ensuring food safety and human health.

This study selected a typical representative experimental area, a certain alkaline farmland in Ningxia, China, with high cadmium concentration. Through field trials, it conducted an evaluation study on the remediation effects of common passivation materials (such as passivating agents, biological remediation agents, and functional fertilizers) on heavy metal Cd. This study explored the changes in the available Cd in the soil, the Cd content in corn stems and leaves, and the enrichment coefficient under different remediation measures. The aim was to explore suitable remediation measures for alkaline cadmium-rich dry farmland in arid regions to ensure food production safety, with the expectation of further improving the agricultural heavy metal Cd remediation technology system in various application scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Test Site

Field experiments were conducted from April to September in 2021. This experiment site is located in certain farmland in Guoyuan City, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, where the cadmium content is relatively high. It represents the representative alkaline soil environment and farming practices in the northwest region of China. This area belongs to the temperate semi-humid zone and features a climate typical of forest grassland, characterized by “cold spring, cool summer, short autumn, and long winter”. The annual average temperature is 6.9 °C, the sunshine duration is 2370 h, the frost-free period is 141 days, and the annual average precipitation is 641.5 mm. Its unique natural conditions such as low precipitation, abundant sunshine, large diurnal temperature difference, and strong evaporation make the soil alkaline, with low cadmium activity, poor migration, low microbial activity, and inability to effectively carry out metabolism and reproduction. The soil type in the experimental area is gray–brown soil, and the planting system is a single-crop corn planting mode. The basic monitoring indicators of the soil in this experimental field are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic monitoring indicators of soil in the experimental field.

2.2. Test Materials

Crops planted: Local main-cultivated corn varieties, provided by local farmers.

Test restoration materials: Four restoration materials with good effects in existing research and field restoration cases were selected, namely sepiolite-type passivator, mercapto clay minerals, microbial inoculants, and bio-organic fertilizer. The composition information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composition of test restoration materials.

2.3. Experimental Design

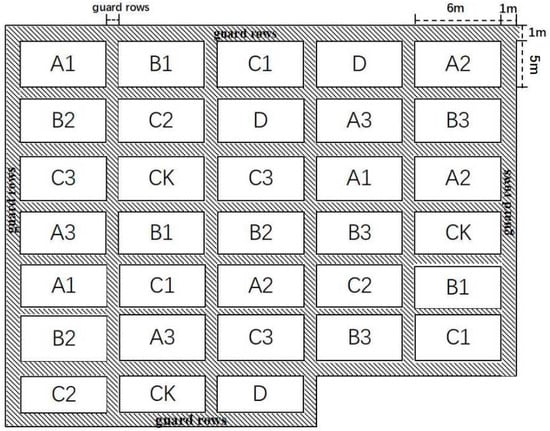

This experiment set up 11 treatments (Table 3), with each treatment replicated three times, totaling 33 plots, and each plot having an area of 30 m2 (5 m × 6 m). The design of this experimental plot adopted a completely random arrangement method. Each plot was separated from the others by furrows (with the width of the furrow approximately 30 cm) to prevent the lateral movement of water and nutrients. This ensured that each treatment could be effectively distinguished. To reduce edge effects, a 1 m-wide protective row was set up around the entire experimental field and each plot, and the same crop was planted. All plant and soil samples were collected from the central area of the plots, avoiding the edge plants. (Figure 1). According to the farmers’ daily planting habits, one week before planting corn, the experimental area was tilled, ridged, and divided into uniform blocks. Then, with urea and phosphorus di-ammonium fertilizer, the various remediation materials were uniformly applied to the experimental plots by manual spreading. The remediation materials were mixed with the soil through repeated tilling. The field management of each experimental plot was strictly consistent, and the daily water management and subsequent fertilization were all in line with local practices.

Table 3.

Experimental design and fertilizer application rates.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of experimental plots.

2.4. Sample Collection and Determination

Soil samples: At the beginning of April 2021 during the early stage of material addition and at the end of September 2021 during the corn ripening period, soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm cultivated layer of each experimental plot using the five-point sampling method. Five samples were combined to form one soil sample. Upon returning to the laboratory, samples were air-dried in a clean, well-ventilated area. Stones and plant debris were removed and passed through a 2 mm nylon mesh. Samples were then sealed and stored for future use.

Plant Samples: Collected simultaneously during corn maturity. Within each plot, corn plants exhibiting consistent growth were selected using the “five-point method” and pooled into a single sample; the corn plants were divided into three parts: stem, leaf, and grain. They were successively washed with tap water, distilled water, and high-purity water, blanched in a 105 °C drying oven for 30 min, and then dried at 70 °C until constant weight. The roots, stems and leaves, and grains were then ground and passed through a 100-mesh nylon sieve for future use.

2.5. Measurement Items and Methods

The determination of soil pH follows the procedure outlined in “Soil Testing Part 2: Determination of Soil pH” (NY/T 1121.2-2006) [25]. The specific procedure is as follows: Weigh 10.00 g of air-dried soil sample passed through a 2 mm sieve into a 50 mL beaker. Add 25.0 mL of ultrapure water (water-to-soil mass ratio of 2.5:1) and stir with a glass rod for 2 min to ensure thorough mixing. Allow the suspension to settle for 30 min. Using a Mettler S20 pH meter (Manufacturer: Mettler-Toledo Group Headquarters City: Greifenstein Country: Switzerland) calibrated with standard buffer solutions of pH 4.00, 6.86, and 9.21, insert the composite electrode into the upper clarified layer. Record the pH value once the reading stabilizes. Perform three parallel measurements for each sample and calculate the average result.

Determination of total cadmium content in soil shall refer to “Soil and Sediment—Determination of Twelve Metal Elements—Aqua Regia Extraction-Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry” (HJ 803-2016)) [26]. The specific procedure is as follows: Accurately weigh 1.0000 g of air-dried soil sample (passed through a 100-mesh sieve) into a 50 mL digestion tube. Add 12 mL of aqua regia (hydrochloric acid and nitric acid in a 3:1 volume ratio) and digest at (95 ± 5) °C in a water bath for 2 h. After digestion, cool to room temperature and dilute with ultrapure water to the 25 mL mark. Allow the extract to settle and clarify, then filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm membrane filter. Finally, determine the cadmium concentration in the filtered solution using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS, Agilent 7700x, Manufacturer: Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The instrument detection limit for cadmium under this method is 0.035 mg/kg.

The available cadmium content in soil was determined using the Gradient Diffusion Membrane (DGT) technique, following the guidelines outlined in “Extraction of Available Cadmium from Agricultural Soil Using the Gradient Diffusion Membrane (DGT) Method” (DB52/T 1465-2019) [27]. The specific procedure is as follows: Weigh 120 g of air-dried soil sample passed through a 2 mm sieve. Add 50.0 mL of Grade 1 water, mix thoroughly, and level the surface. Cover the sample and incubate it in a constant temperature and humidity incubator at 25 °C for 24 h ± 1 h (maintaining relative air humidity at 80% throughout). Evenly distribute the conditioned soil into the DGT device base, then sequentially cover with the filter membrane and the fixed membrane (Chelex-100 resin gel membrane, Manufacturer: Promega (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. City: Beijing Country: China ). Assemble the device and place it face down, flush against the soil surface. After 24 h at 25 °C in darkness, remove the fixed membrane and elute the adsorbed cadmium using 9 mL of ultrapure HNO3 (1.0 mol/L) solution. Finally, determine the cadmium concentration in the eluate using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS, Agilent 7700x). Calculate the content of cadmium in the available form in soil (CDGT) based on the formula provided in the standard.

Determination of cadmium content in various parts of maize plants (stems, leaves, grains) shall follow the National Food Safety Standard for Determination of Multiple Elements in Food (GB 5009.268-2016) [28]. After sample collection, rinse sequentially with tap water and deionized water to remove surface debris, then dry in a 70 °C oven to constant weight. After grinding with a plant pulverizer, sieve through a 60-mesh nylon screen for later use. Accurately weigh 0.5000 g of the powdered sample into a digestion tube, add 8.0 mL of ultrapure nitric acid, and fully digest using a microwave digestion system. After cooling the digestion solution, transfer with ultrapure water and dilute to a 25 mL volumetric flask. Perform final determination using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS, Shimadzu 2030, Manufacturer: Shimadzu Corporation, City: Kyoto, Country: Japan) with a detection limit of 0.002 mg/kg for cadmium under this method.

2.6. Evaluation of Heavy Metal Remediation Effect

2.6.1. Reduction in the Available Forms of Heavy Metals in the Soil and Passivation Rate

The absorption of heavy metal elements by plants mainly refers to their effective state, also known as their biological availability. The passivation effect of conditioning agents on heavy metal elements in soil is mainly reflected in reducing the degree of the effective state of this element in the environment. Generally, the passivation effect of conditioning agents is expressed as the percentage of the decrease in the effective state of heavy metals in the soil (ratio) after adding the conditioning agent compared to the effective state of heavy metals in the soil (ratio) [29]. This ratio is also called the passivation rate. Therefore, the greater the reduction amplitude of the effective state of heavy metals in the soil by a certain remediation material, the higher the passivation rate, indicating that the passivation effect of the remediation material is better.

2.6.2. Enrichment Coefficient of Corn Plants

The enrichment coefficient is an important indicator for the absorption capacity of various plant organs for heavy metals in the soil. It can reflect the ability of plants to absorb heavy metals from the soil and can also, to some extent, represent the difficulty of the element being absorbed and utilized by the plants. The larger the enrichment coefficient, the stronger the enrichment ability for Cd [30,31]. The calculation formula for the Cd enrichment coefficient (BCF) of the stem and leaf parts of corn is as follows:

Stem Enrichment Coefficient:

Leaf Enrichment Coefficient:

Among these, denotes the cadmium content in the stem, denotes the cadmium content in the leaf, and represents the cadmium content in soil.

This study used Microsoft Excel 2019 and Origin 2023 for data processing and plotting. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed, and the differences between treatments were tested for significance using the LSD method (p = 0.05). The data in the charts are presented as means ± standard errors.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in the Available Cadmium Content in Soil During Different Treatments

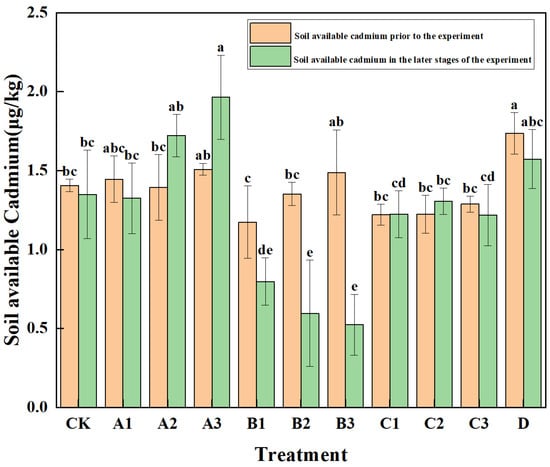

Through one-way analysis of variance, the early-stage soil available forms showed 10 degrees of freedom within groups and 22 degrees of freedom between groups, yielding F = 3.637, p = 0.06. The late-stage soil available forms showed 10 degrees of freedom within groups and 22 degrees of freedom between groups, yielding F = 13.54, p < 0.001. The results of the influence of different treatments on the available cadmium content in the soil are shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that, compared with the blank treatment (CK), except for the A2, A3, C1, and C2 treatments, the available cadmium content in the soil of the other treatments was significantly lower than before the implementation of the measures (p < 0.05). The test treatment groups in group B all significantly reduced the available cadmium in the soil. The B1, B2, and B3 treatments, respectively, reduced the available cadmium in the soil from 1.173 μg·kg−1 to 0797 μg·kg−1, 1.351 μg·kg−1 to 0.595 μg·kg−1, and 1.488 μg·kg−1 to 0.523 μg·kg−1, and the B3 treatment had the most significant effect in reducing the available cadmium content in the soil. In group A, A1 showed an ability to reduce the available cadmium in the soil, reducing it from 1.455 μg·kg−1 to 1.324 μg·kg−1. The A2 and A3 treatments in group A had an increase in the available cadmium content in the soil. In group C, C3 showed an ability to reduce the available cadmium in the soil, reducing it from 1.288 μg·kg−1 to 1.218 μg·kg−1. The C1 and C2 treatments in group C had an increase in the available cadmium content in the soil. The test treatment in group D reduced the available cadmium content in the soil from 1.735 μg·kg−1 to 1.537 μg·kg−1, showing an ability to reduce the available cadmium in the soil.

Figure 2.

Cadmium content in soil available forms under different treatments. Note: Different lowercase letters in the figure indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

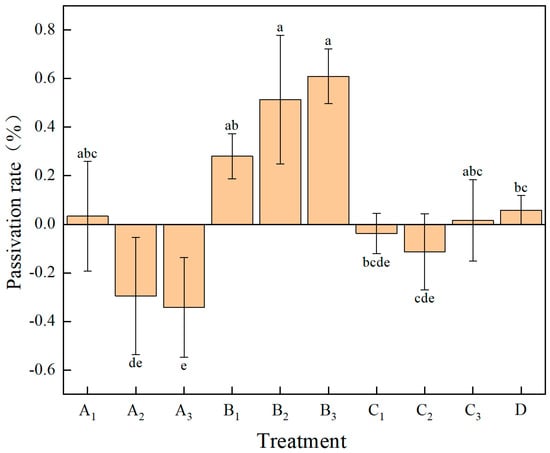

3.2. The Inhibitory Effects of Different Treatments on the Availability of Cadmium in the Soil

The passivation rates of soil available Cd by different treatments are shown in Figure 3. One-way ANOVA between treatment groups yielded a between-subjects degrees of freedom of 9, with an F-value of 9.667 and p < 0.001. Except for A2, A3, C1, and C2, all other treatments have a passivation effect on Cd in the soil. The passivation rates from high to low are B3 > B2 > B1 > D > A1 > C3. The B treatment group not only has a higher passivation rate, but the passivation rate of soil available Cd also continuously increases with the increase in the dosage of the remediation material. When the dosage is 2250 kg·ha−1, which is the B3 treatment, the passivation rate of soil available Cd compared to the CK group reaches 60.94%. In the A treatment group, as the dosage of the remediation material increases, the passivation rate of soil available Cd continuously decreases. Only at the dosage of 1500 kg·ha−1, which is the A1 treatment, does it have a passivation effect on soil available cadmium, and compared to the CK control group, the soil passivation efficiency is 3.33%. The C3 treatment of group C has a passivation effect on soil Cd. When the dosage is 3600 kg·ha−1, compared to the CK control group, the passivation rate of soil Cd is 1.62%. The D treatment group has a passivation effect on soil available cadmium. When the dosage is 3600 kg·ha−1, compared to the CK control group, the soil passivation efficiency is 5.86%.

Figure 3.

The inhibition rates of different treatments on the available cadmium in the soil. Note: Different lowercase letters in the figure indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

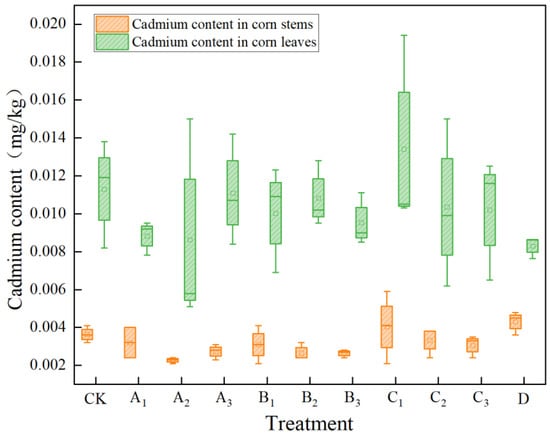

3.3. Effects of Different Treatments on Cadmium Content in Different Parts of Corn Plants

The Cd content in the stems and leaves of corn after different treatments is shown in Figure 4. The order of cadmium content in the above-ground parts of corn plants among all treatment groups was leaves > stems > grains (the cadmium content in corn grains was not detected the detection limit was 0.002 mg·kg−1). Overall, it showed a characteristic of jointly reducing the Cd content in corn stems and leaves, but the degree of influence varied among different treatments. From the reduction amplitude of Cd (Table 4), compared with the CK treatment group, both the A treatment and the B treatment significantly reduced the Cd content in the stems and leaves of corn. Among them, the Cd content in the corn stems compared with the CK group was reduced by 37.16%, and the Cd content in the corn leaves compared with the blank group was reduced by 23.50%. The Cd content in the corn stems and leaves after the B3 treatment compared with the CK group was reduced by 26.32% and 15.70%, respectively. The Cd content in the corn stems and leaves after the C3 treatment compared with the blank group was reduced by 15.86% and 9.80%, and the Cd content in the corn leaves after the D treatment compared with the blank group was reduced by 26.56%.

Figure 4.

Cadmium content in corn stems and leaves under different treatments.

Table 4.

Effects of different treatments on cadmium content in corn stems and leaves.

3.4. Effects of Different Treatments on Cadmium Enrichment Coefficient of Maize

The effects of different treatments on the cadmium enrichment coefficients of corn stems and leaves are shown in Table 5. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no significant differences in the enrichment coefficients of stems among treatments. The degrees of freedom were 10 for between-group variation and 21 for within-group variation, yielding an F-value of 1.532 and a p-value of 0.197. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the enrichment coefficients of leaves, with degrees of freedom of 10 and 22, respectively, resulting in an F-value of 1.532 and a p-value of 0.230. As shown in the table, it can be seen that different treatments all have certain effects on the Cd accumulation coefficient of the corn plants. From the reduction in the Cd accumulation coefficient, the treatment groups are ranked as B > A > D > C. Compared with the CK group, in all treatments except C1, C2, and D, the enrichment coefficients of Cd in corn stems and leaves decreased. Among them, the enrichment coefficient of corn stems and leaves in treatment A2 was the lowest, which was 31.92% and 19.84% lower than that of control group (CK), respectively. Next is the B3 treatment, which significantly reduced by 31.09% and 19.61%, respectively, compared to the CK group. In both group A and group B, the Cd accumulation coefficients of corn stems and leaves were generally low. As the additional amount increased, the enrichment coefficient of cadmium in the corn stems of the B treatment group showed a downward trend, which was consistent with the trend of cadmium’s available form in the soil.

Table 5.

Cadmium accumulation coefficients of corn stems and leaves in different treatments.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Different Restoration Materials on the Available Cadmium Content in the Soil

The principle by which applying conditioning agents can reduce the risk of soil heavy metal pollution and achieve safe food production is that they can alter the bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil. In this study, the application of four remediation materials within a certain concentration range was able to effectively reduce the available content of heavy metal Cd. The reduction extent decreased in order from large to small: mercapto clay minerals > biological organic fertilizer > sepiolite > microbial inoculants. Among them, sepiolite and microbial agent did not show any inhibition effect in most treatment groups.

The mercapto clay minerals type passivation materials exhibit excellent passivation effect on the available cadmium in alkaline dryland soil in arid regions. Analyzing the main reasons, mercapto clay minerals belong to modified clay minerals. Due to the presence of a large number of negative charges and functional groups such as hydroxyl groups on their surface, they can undergo adsorption or complexation reactions with heavy metals in the soil, reducing the mobility and biological availability of heavy metals in the soil. However, research has found that applying mercapto clay minerals can increase the negative charges on the surface of soil clay particles and enhance the adsorption and fixation of Cd2+ by soil clay particles. The sulfide modification can significantly enhance the adsorption capacity of the passivation material for heavy metal ions. This characteristic is particularly prominent in an arid environment with less rainfall and a high evaporation rate [32,33,34]. Wu et al. [35] applied sulfide-modified montmorillonite in alkaline dryland wheat fields. The results showed that an addition amount of 0.5 g·kg−1–2.0 g·kg−1 could reduce the available cadmium in the soil by up to 58.18%. This conclusion is close to the 60.94% reduction in available cadmium in the soil by the mercapto clay minerals, with an additional amount of 2250 kg·ha−1, in this study. Currently, there are many verified cases of the performance of modified clay passivation materials for soil heavy metal remediation, As Yu et al. [36]. modified bentonite with two different organic treatment methods, tetramethylammonium and dodecyltrimethylammonium, and quantified the metal mobility in the soil after treatment by using the Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP), it was found that the treated bentonite had a stronger immobilization effect on heavy metals than the unmodified bentonite.

In this study, the biological organic fertilizer treatment group showed a certain inhibitory effect on the available Cd in the soil. Biological organic fertilizer is a multifunctional fertilizer that combines the effects of microbial fertilizer and organic fertilizer. It is made from specific functional microorganisms and plant and animal residues. The biological organic fertilizer selected in this study contains Bacillus subtilis, Streptomyces lichenivorus, etc., and the effective viable bacteria count is ≥200 million, and organic matter greater than 40%. It has functions such as improving soil fertility, improving the structure of soil microorganisms, promoting crop production, and reducing heavy metal pollution [37,38]. Studies have shown that the genus Bacillus has a thick peptidoglycan layer rich in anions, enabling it to remove heavy metal ions with high affinity [39]. Liu Yuechang et al. [40] demonstrated that Bacillus subtilis alone or in combination with other bacteria can increase the fixed state content of Cd in farmland soil and reduce the bioavailability of Cd in the soil.

Sepiolite is also a commonly used material for the remediation and passivation of heavy metals in farmland. Numerous studies indicate that the sepiolite passivation materials have a certain passivating effect on the available Cd in farmland soil, but these studies are mostly conducted in acidic paddy fields [41,42]. The passivation principle of these materials mainly relies on physical–chemical adsorption, precipitation, complexation, and the increase in soil pH to convert Cd from an exchangeable state to a stable residue state, thereby reducing the activity of soil Cd. Due to its narrow internal pores and low loading capacity, the adsorption performance of sepiolite is limited, and its passivation efficiency is often lower than that of modified mineral passivation materials [43,44]. The results of this study show that the passivation effect of sepiolite passivation material is not ideal. As the additional amount of sepiolite passivator increases, the passivation effect weakens. Sepiolite is a fibrous, porous, magnesium-rich silicate clay mineral, rich in exchangeable calcium ions (Ca2+) and magnesium ions (Mg2+), with a high surface area, strong ion exchange capacity, and strong surface adsorption capacity. After applying sepiolite, the pH value of the soil will increase, increasing the negative charges in the soil, which is conducive to the adsorption and precipitation of cadmium, thereby reducing the bioavailability and mobility of heavy metals in the soil [45,46]. Studies have shown that sepiolite is an alkaline substance that can increase the pH value of acidic soil, thereby exerting a better effect; however, under certain specific conditions, its effectiveness will be limited, and it will increase the mobility of cadmium and cause soil hardening [47,48]. Li Xiang et al. [49] found in their research that excessive application of alkaline amelioration materials in the soil can easily cause side effects, leading to problems such as activation and leaching of heavy metals. Shi Xin [50] studied the effect of sepiolite passivation remediation on soil catalase activity at different additional amounts. It was found that as the additional amount of sepiolite increased, the soil catalase activity showed both an increase and a decrease. When the additional amount of sepiolite was 50 g·kg−1, the soil catalase activity was lower than that in other sepiolite addition treatment groups. This might be because excessive sepiolite had a certain inhibitory effect on soil catalase activity. Huang Rong [51] studied the effects of applying different fertilizers on the restoration of cadmium-contaminated soil. She found that during the process of using sepiolite to treat cadmium-contaminated soil, the application of urea, calcium magnesium phosphate fertilizer, common calcium, and K2SO4 did not have significant adverse effects on the detoxification effect. However, the application of KCl to a certain extent reduced the detoxification effect of sepiolite. It can be seen that applying fertilizer in the field has little effect on the remediation of cadmium pollution by sepiolite. The soil in this experimental area is inherently alkaline. As the amount of added sepiolite increases, the concentration of OH− ions in the alkaline soil rises. These ions combine with heavy metal cations to form a series of negatively charged hydroxide complexes, thereby weakening the surface adsorption and cation exchange capacity of sepiolite in an alkaline environment. Therefore, when using sepiolite to remediate Cd pollution in alkaline soil, a dose gradient experiment is necessary to further explore the appropriate additional amount.

The microbial inoculants also performed poorly in this study, which is closely related to the soil environment in the arid regions of Northwest China. The effectiveness of microbial remediation of soil heavy metal pollution is mainly influenced by environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, and humidity. In soil environments under drought stress, extreme temperatures, or acidic or alkaline conditions, it is not conducive to the growth and activity of microorganisms. The beneficial microorganisms applied to the soil are very susceptible to the influence of the natural environment and natural enemies, resulting in a decrease in their survival rate. Therefore, appropriate temperature and pH values are crucial for the colonization of rhizosphere-beneficial microorganisms [52,53]. To avoid the inactivation of microbial inoculants, strong environmental conditions are required for their application in agricultural heavy metal remediation. However, in this study area, there is a large diurnal temperature difference, less rainfall, and strong evaporation, which are not conducive to the colonization and survival of microorganisms. It can be seen that the application of exogenous microbial inoculants in heavy metal remediation fields in the arid regions of Northwest China is not ideal.

4.2. The Influence of Different Restoration Materials on the Accumulation Capacity of Corn Plants

The differences in heavy metal content among crop organs are attributed to the organ’s enrichment capacity, crop varieties, and some climatic factors. Relevant studies have shown that the immobilizing materials mainly reduce the accumulation of cadmium in crops by affecting the biological availability of cadmium in the soil. In this study, the accumulation of Cd in different organs of corn plants was found to be leaf > stem > grain, and the enrichment coefficients of each part showed the same pattern. Since stems and leaves are mainly composed of plant fibers, while the main component of grains is starch, cadmium mainly accumulates in the fibers, and starch has a relatively weak effect on cadmium accumulation. This distribution pattern is similar to that of Liu Jing et al. [54]. In this experiment, after applying four immobilizing materials, all affected the Cd content in the stems and leaves of corn and the enrichment coefficients of each part. Overall, the biological enrichment coefficients of each organ of corn were less than 1, indicating that corn has a weak ability to accumulate cadmium in the soil. Immobilizing materials mainly inhibit the biological availability of cadmium in the soil, thereby affecting the accumulation of Cd in plants. Although the effects of the four immobilizing materials on the accumulation of Cd in different parts of corn are different, they all hinder the absorption of soil Cd by corn, thereby reducing the content of Cd in each part. Compared with the CK group, the immobilizers and microbial agents can reduce the accumulation of Cd in the stems and leaves of corn at certain additional amounts, and the Cd content in the leaves of corn plants after applying biological organic fertilizer is lower than that of the blank group, while the Cd content in the stems is slightly higher than that of the blank group. The application of organic fertilizer increases the accumulation of Cd in the stems of corn. Overall, the enrichment coefficients of Cd in the stems and leaves of corn after applying immobilizers are lower than those after applying microbial agents and biological organic fertilizers, indicating that the application of immobilizers reduces the biological availability of heavy metal Cd in the soil and limits the migration of Cd into corn. Research shows that the impact of applying organic fertilizers on the accumulation of cadmium in crops is rather complex. Generally, the application of organic fertilizers can promote the growth of crops, increase yields, and reduce the availability of cadmium in the soil through adsorption and complexation [55]. According to over 80% of the literature surveyed, the application of organic fertilizers leads to an increase in the content of heavy metals in crops. Organic matter can form highly stable soluble substances with cadmium, which significantly increases the solubility of cadmium in the soil but does not enhance the absorption by plants. However, the formation of small-molecule soluble complexes does increase the absorption of cadmium by plants [56,57]. The results of this study are consistent with the conclusions of most of the above studies. However, some studies have shown that in cadmium-contaminated soil, applying biological organic fertilizer can significantly reduce the content of available cadmium in the soil, promote the transformation of weakly acidic extractable cadmium to residual cadmium, and reduce the harm of cadmium; the cadmium content in the roots and grains of corn decreased significantly [58]. It can be seen that the research results on the effects of organic fertilizers on the accumulation and activity of heavy metals in soil are different, possibly because different types of organic fertilizers have different effects on the effective content of heavy metals in the soil.

In conclusion, the addition of passivation remediation materials to the cadmium-contaminated soil in dryland corn fields in Northwest China can effectively reduce the availability of cadmium in the soil, decrease the migration and accumulation of cadmium to the above-ground parts of corn, and thereby reduce the enrichment of cadmium in the corn grains. However, in the selection of passivation remediation materials, conventional modified mineral immobilization materials, sepiolite, microbial agents, and bio-organic fertilizers have significant differences in their cadmium reduction capabilities. They control the migration and transformation process of cadmium in the soil–crop system from different perspectives. Based on the changes in the available cadmium in the soil, the cadmium content in corn stems and leaves, and the enrichment coefficient, the application of mercapto clay minerals type passivation materials has the best effect.

5. Conclusions

Applying four remediation materials, namely mercapto clay minerals type passivation, sepiolite, microbial inoculants, and bio-organic fertilizers, within a certain concentration range, all materials reduced the available cadmium content in the soil. However, the effects vary significantly. The order of passivation effectiveness from the highest to the lowest is mercapto clay minerals, bio-organic fertilizers, sepiolite, and microbial inoculants. Among them, the passivation efficiency of applying 2250 kg·ha−1 of mercapto clay minerals type passivation reached 60.94%; the passivation efficiency of bio-organic fertilizers was 5.86%. The passivation effects of the latter two were relatively unstable. At the same time, the addition of different remediation materials had different effects on the accumulation and translocation of cadmium in different parts of corn plants. Overall, the sequence of cadmium content in the above-ground organs of corn plants in all treatment groups was leaves > stems > grains. Under different additive amounts, sepiolite and mercapto clay minerals both reduced the cadmium content in the stems and leaves of corn. Simultaneously analyzing the effects of four remediation agents on mercury, arsenic, lead, and chromium in soil, compared to the control group, there was no significant change in soil mercury levels before and after applying the remediation fertilizer. Overall, arsenic content increased by 0.53–7.86%, lead content rose by 1.66–6.67%, and chromium content climbed by 1.39–14.56%. According to farmer feedback, crop yields decreased by less than 10% after applying the remediation fertilizer. Overall, mercapto clay minerals type passivation materials have better effects on the passivation of soil available cadmium and the inhibition of cadmium absorption in various tissues of corn. They can be further verified and promoted in field trials in dryland alkaline farmland corn fields, providing certain technical references for the targeted and categorized soil heavy metal pollution remediation in cultivated land.

Author Contributions

K.Y. and D.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Project Administration. T.M.: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing—Review and Editing, Funding Acquisition. Y.Y. and Y.L.: Methodology, Visualization, Data Curation. Z.Z. and Y.G.: Sample Collection, Methodology, Data Analysis. R.S.: Formal Analysis, Writing—Review and Editing, Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia HuiAutonomous Region (Grant No. 2023BEG01002); Funds for Science and Technology Innovation Project from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2025-CAAS-CXGC-SRG).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Zou, T.; Lian, J.P.; Chen, Y.L.; Cheng, L.P.; Hamid, Y.; He, Z.L.; Jeyakumar, P.; Yang, X.E.; Wang, H.L. Simultaneous mitigation of cadmium contamination and greenhouse gas emissions in paddy soil by iron-modified biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.F.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.Q.; Wang, J.N.; Liu, T.T. Review of soil heavy metal pollution in China: Spatial distribution, primary sources, and remediation alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.C.; Wang, S.T.; He, X.; Sun, H.; Yan, H.Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, K.X.; Liu, W. The joint action of nano-montmorillonite and plant roots on the remediation of cadmium-contaminated soil and the improvement of rhizosphere bacterial characterization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.J.; Cai, C.; Chi, H.F.; Reid, B.J.; Coulon, F.; Zhang, Y.C.; Hou, Y.W. Remediation of cadmium and lead polluted soil using thiol-modified biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 122037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.Y.; Jia, X.Y.; Wang, L.W.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.J.; Bank, M.S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global soil pollution by toxic metals threatens agriculture and human health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.F.; Parikh, S.J.; Colinet, G.; Garland, G.; Huo, L.J.; Zhang, N.; Shan, H.; Zeng, X.B.; Su, S.M. Water-fertilizer regulation drives microorganisms to promote iron, nitrogen and manganese cycling: A solution for arsenic and cadmium pollution in paddy soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.B.; Guo, W.Q.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, G.Y.; Xian, J.R.; Yang, Y.X.; Liu, L.X.; Xu, X.X. Possibility of using combined compost-attapulgite for remediation of cd contaminated soil. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.K.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.Y.; Ma, L.Y.; Wu, Y.J.; Liu, Q.Z.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y. Cadmium uptake from soil and transport by leafy vegetables: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.J.; Gao, F.K.; Gao, J.L.; Ding, J.X.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.Y.; Li, H.L.; Yan, Y.X. The synergistic impact of cadmium and the wheat rhizosphere on the soil bacterial community in alkaline cropland in northern China. J. Soils Sediments 2025, 25, 2420–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.J.; Wang, P. Arsenic and cadmium accumulation in rice and mitigation strategies. Plant Soil 2020, 446, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; He, L.; Long, S.; Wang, S.L. Bioavailability, migration and driving factors of as, cd and pb in calcareous soil amended with organic fertilizer and manganese oxidizing bacteria in arid northwest China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.X.; Wang, N.; Luo, Y.C.; Pan, Y.Y.; Cao, Y.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Wen, X.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, Z.H. Insights into the remediation of cadmium pollution, changes of carrot nutrients and microbial communities in farmland soil amended by oyster shell powder compared to corn stalk biochar. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 317, 122035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z.; Yu, H.; Sun, X.W.; Yang, J.T.; Wang, D.C.; Shen, L.F.; Pan, Y.S.; Wu, Y.C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y. Effects of sulfur application on cadmium bioaccumulation in tobacco and its possible mechanisms of rhizospheric microorganisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 368, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.W.; Cheng, Z.H.; Gao, X.Y.; Xu, Y.J.; Wang, Y. Plant Responses to Cadmium Pollution: From Absorption, Transport to Response and Mitigation Mechanisms. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 49, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.H.; Bai, J.J.; Tian, R.Y.; Wang, G.C.; You, L.Y.; Liang, J.N.; Ci, K.D.; Liu, M.L.; Kou, L.Y.; Zhou, L.L.; et al. Cadmium Remediation Strategies in Alkaline Arable Soils in Northern China: Current Status and Challenges. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2024, 61, 348–360. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Gao, S.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.X.; Jia, H.T.; Zhu, H.; Sun, Y.B. Passivation remediation of weak alkaline cadmium contaminated soil with biochar and sepiolite. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2024, 44, 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.H.; Yan, Y.; He, C.; Feng, Y.; Darma, A.; Yang, J.J. The immobilization of cadmium by rape straw derived biochar in alkaline conditions: Sorption isotherm, molecular binding mechanism, and in-situ remediation of cd-contaminated soil. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 351, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Q.; Xu, Y.M.; Song, C.Z.; Wu, Y.X.; Huang, Q.Q.; Liang, X.F. Using thiolated palygorskite to remediate Cd-contaminated alkaline soil via rapid immobilization. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.X.; Yin, M.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.H.; Li, H.G.; Hong, M.; Qiu, G.H.; Feng, X.H.; Tan, W.F. Simulation of vertical migration behaviors of heavy metals in polluted soils from arid regions in northern China under extreme weather. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.W.; Yu, C. The leaching characteristics of cd, zn, and as from submerged paddy soil and the effect of limestone treatment. Paddy Water Environ. 2015, 13, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.L.; Huang, N.; Liu, X.; Gong, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, S.R.; Chen, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, G. Enhanced silicate remediation in cadmium-contaminated alkaline soil: Amorphous structure improves adsorption performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Wang, W.H.; Liu, L.H.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.W.; Li, X.Z.; Qiu, G.H. Remediation of cadmium-polluted weakly alkaline dryland soils using iron and manganese oxides for immobilized wheat uptake. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.L.; Yuan, C.; Zhu, X.L.; Fu, Y.C.; Gui, G.; Zhang, Z.X.; Li, P.X.; Liu, D.H. In-situ Passivation Remediation Materials in Cadmium Contaminated Alkaline Agricultural Soil: A Review. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 49, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.; Di, X.R.; Liang, X.F.; Qin, X.; Peng, Y.Y.; Xu, Y.M.; Huang, Q.Q.; Sun, Y.B. Effect of single and combined application of sulfhydryl grafted palygorskite and manganese compounds on alkaline Cd contaminated soils. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2024, 44, 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- NY/T 1121.2-2006; Soil Testing Part 2: Determination of Soil pH. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- HJ 803-2016; Soil and Sediment—Determination of Twelve Metal Elements—Aqua Regia Extraction-Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- DB52/T 1465-2019; Extraction of Available Cadmium from Agricultural Soil Using the Gradient Diffusion Membrane (DGT) Method. Guizhou Provincial Administration for Market Regulation: Guizhou, China, 2019.

- GB 5009.268-2016; National Food Safety Standard Determination of Multiple Elements in Food. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Liu, J.; Zhang, N.M.; Yuan, Q.H. Passivation Effect and Influencing Factors of Different Passivators on Lead-cadmium Compound Contaminated Soils. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2021, 30, 1732–1741. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.W.; Jing, Y.P.; Li, Y.; Nie, Y.; Xu, Y.L.; Kang, X. Effects of chelating agents on cadmium pollution soil remediation and cadmium absorption by rapeseed. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2023, 55, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Le, X.Y.; Hu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Li, H.J.; Gao, P.; Li, L.H. The Effects of Soil Cadmium Pollution on the Growth and Cadmium Distribution of Lilium lancifolium. Chin. Soil Fertil. 2023, 61, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.F.; Qin, X.; Huang, Q.Q.; Huang, R.; Yin, X.L.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.B.; Xu, Y.M. Mercapto functionalized sepiolite: A novel and efficient immobilization agent for cadmium polluted soil. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 39955–39961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.F.; Li, N.; He, L.Z.; Xu, Y.M.; Huang, Q.Q.; Xie, Z.L.; Yang, F. Inhibition of cd accumulation in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grown in alkaline soil using mercapto-modified attapulgite. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Sun, G.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Cao, M.H.; Tu, S.X.; Xiong, S.L. Simultaneous reduction in cadmium and arsenic accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) by iron/iron-manganese modified sepiolite. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Q.; Yang, H.M.; Wang, M.; Sun, L.; Xu, Y.M. Immobilization of soil cd by sulfhydryl grafted palygorskite in wheat-rice rotation mode: A field-scale investigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Xu, J.; Jiang, X.H.; Liu, C.; McCall, W.; Lu, J.L. Stabilization of heavy metals in soil using two organo-bentonites. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.M.; Jing, F.; Hu, S.M.; Wen, X.; Li, L.Q. Effects of bio-organic fertilizer on the forms and migration characteristics of Cd in soil-rice system. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 40, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Babaei, K.; Sharifi, R.S.; Pirzad, A.; Khalilzadeh, R. Effects of bio fertilizer and nano Zn-Fe oxide on physiological traits, antioxidant enzymes activity and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under salinity stress. J. Plant Interactions. 2017, 12, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; You, X.X.; Wang, B.; Du, L.N. Quantification of the antagonistic and synergistic effects of Pb2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ bioaccumulation by living Bacillus subtilis biomass using XGBoost and SHAP. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 446, 130635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Li, B.Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, L. Study of Two Microbes Combined to Remediate Field Soil Cadmium Pollution. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 34, 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.B.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.M.; Liang, X.F.; Wang, L. In situ stabilization remediation of cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) co-contaminated paddy soil using bentonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 105, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.H.; Gu, Y.; He, F.P.; Wu, H.Y.; Liu, Q.F.; Li, M.D. Effects of Soil Conditioners and Compound Microbial Fertilizers on Cd and Pb in Farmland Soil and Rice. Hunan Agric. Sci. 2017, 3, 27–30+34. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.; Xie, S.; Zheng, S.N.; Xu, Y.M.; Sun, Y.B. Two-step modification (sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate composites acid-base) of sepiolite (SDBS/ABsep) and its performance for remediation of Cd contaminated water and soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 433, 128760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, P.Y.; Ye, J.P.; Zhang, G.M.; Cai, Y.J. Simultaneous in-situ remediation and fertilization of Cd-contaminated weak-alkaline farmland for wheat production. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Y.; Tang, L.; Hussain, B.; Usman, M.; Liu, L.; Ulhassan, Z.; He, Z.L.; Yang, X.E. Sepiolite clay: A review of its applications to immobilize toxic metals in contaminated soils and its implications in soil–plant system. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.B.; Sun, G.H.; Xu, Y.M.; Wang, L.; Liang, X.F.; Lin, D.S. Assessment of sepiolite for immobilization of cadmium-contaminated soils. Geoderma 2013, 193, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Ye, G.Y.; Gao, Y.T.; Wang, H.Q.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y.Y.; Chun, J. Cadmium adsorption by thermal-activated sepiolite: Application to in-situ remediation of artificially contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.H.; Li, Y.H.; Sun, H.B.; Liu, R.X.; Han, Y.; Bi, F.X.; Fan, H.L.; Zhang, G.S.; Zhang, Y.P.; Wang, Y.F.; et al. Ball-milled sepiolite/phosphate rock for simultaneous remediation of cadmium-contaminated farmland and alleviation of phosphorus deficiency symptoms in pepper. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 150925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.B. Leaching Behavior of Pb, Cd and Zn from Soil Stabilized by Lime Stabilized Sludge. Environ. Sci. 2014, 35, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X. The Effects of Sepiolite on lmmobilization Remediationof Soil Contaminated by Cadmium. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Jilin, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R. Effects of Different Inorganie Fertilizer on Immobilization Remediation of Cd Polluted Paddy Soil Using Sepiolite. Chin. Acad. Agric. Sci. 2018, 26, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.M.; Zhao, J.Y.; Ding, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, S.R.; Zhen, J.; Wu, Z.J.; Guo, X.B.; Liu, Y.Z.; Wang, Z.W.; et al. Study on the effects of biochar-based microbial agents on plant absorption of heavy metals and soil microorganisms. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2024, 53, 1160–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.H.; Tian, P. A review of soil microorganism functions in soil improvement and remediation. Pratacultural Sci. 2024, 41, 2622–2636. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Effects of Cadmium Concentrations on Growthand Cadmium Accumulation in Maize. Master’s Thesis, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.J.; Zhou, D.L.; Ye, W.L.; Fan, T.; Ma, Y.H. Research Progress of Bio-organic Fertilizer in Soil Improvement and Heavy Metal Pollution Remediation. Environ. Pollut. Control 2019, 41, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.F. The Effects of Different Fertilization on Cadmium Accumulation and Transference in Soil. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Lin, C.J.; Wang, X.; Peng, B.; Tan, C.Y.; Zhang, X.P. Effects of Organic Manure Fertilizers and Its Amendment of Sulfates on Availability of Arsenic and Cadmium in Soil-Rice System. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2020, 57, 667–679. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.H.; Lv, Q.Y.; Zhang, G.Z.; Hu, H.Q. Effects of bio-organic fertilizers on morphology of cadmium in soil and accumulation of cadmium in maize. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2024, 43, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).