Abstract

The application of organic amendments is increasing in intensive modern agriculture. However, the impacts of organic amendments with distinct quality and quantity on soil mineral nitrogen (N) dynamics remain unclear. In this study, we performed a laboratory incubation experiment for 90 days to investigate the effects of organic amendments with different carbon-to-nitrogen ratios (C/N) (7, 119, 506) and application rates (2, 4, 6 g C kg−1) on N mineralization–immobilization processes in calcareous cropland soil. The study showed that net N mineralization induced by low C/N amendment (rapeseed cake, 7) occurred in this soil. In contrast, net N immobilization was stimulated by glucose and high C/N organic amendments, including maize straw (C/N, 119) and cypress sawdust (C/N, 506). The immobilized N was in the order of glucose > maize straw > cypress sawdust regardless of application rates, which was ascribed to the discrepancy of their C availability. Both N mineralization and N immobilization increased with application rates during the incubation period. The net N mineralization from these organic amendments was significantly affected by C/N ratios (p < 0.001), application rates (p < 0.001), and their interaction (p < 0.001). The study indicated that organic amendments with a higher C/N ratio would promote soil N immobilization, which was further reinforced by higher application rates, thereby decreasing the risk of reactive N loss in calcareous soil.

1. Introduction

A significant increase in cereal production, primarily driven by the large-scale use of synthetic nitrogen (N) fertilizers, has taken place over the past half century to ensure food security for people worldwide [1,2,3]. However, excess N fertilizer application in agriculture has led to a significant buildup of nitrate (NO3−) [4], which increases N loss through leaching and denitrification, ultimately leading to a low N retention capacity of soil [5]. This outcome decreases N fertilizer use efficiency and further triggers various environmental problems, such as greenhouse gas emissions [2,6,7]. The purple soil widely distributed in the Sichuan Basin has a higher autotrophic nitrification rate due to its high pH [8], consequently contributing to a significant accumulation of NO3− [9,10]. However, microbial NO3− immobilization induced by organic amendments is beneficial for reducing NO3− contents [11,12,13].

Organic amendments alone or together with mineral N are increasingly being applied in intensively cultivated agricultural systems for preventing nutrient deficiency and maintaining high productivity [14,15,16]. In soils, carbon (C) is closely linked to N [15], which undoubtedly affects the soil N temporary dynamics [14,17]. Microbial-driven N transformation processes, such as N mineralization or immobilization, are regulated by the chemical quality of organic amendments and soils [18,19,20]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that the soil N immobilization rate increased with soil organic C, total N (TN), phosphorus, and microbial biomass C but decreased with soil pH [21], a finding consistent with the results of Li et al. [22]. Additionally, the biochemical composition of plant residues has been extensively investigated in relation to the dynamics of soil inorganic N and greenhouse gas emissions following their applications. For example, Song et al. [23] have revealed that the correlation of carbon dioxide (CO2) emission to net N mineralization strongly depended on soil labile C and the carbon-to-nitrogen ratios (C/N). Wang et al. [24] proposed that among all biochemical indices, the ratios of aryl/carbonyl, O-aryl/carbonyl, and (aryl+O-aryl)/carbonyl C exhibited the closest relationships with cumulative C mineralization. Among these quality characteristics, the C/N ratio of organic residues is generally recognized as the key regulator linking C decomposition to N dynamics in cropland soils.

Generally, high C/N residues are considered to be more effective at minimizing mineral N accumulation and enhancing N immobilization than low C/N ratios [25,26,27,28]. Nevertheless, some studies have shown that residues with a lower C/N ratio can cause more soil mineral N immobilization [18,29]. Zhao et al. [30] found a stronger stimulation effect of rice straw on microbial N immobilization than sugarcane bagasse despite a lower C/N ratio of rice straw. Bonanomi et al. [31] also suggested that, despite similar C/N ratios, cellulose stimulated N immobilization within 3–10 days, whereas this was apparent after 100 days of incubation in sawdust-added soils. Moreover, the effects of application rates on soil N mineralization or the N immobilization process after organic amendments return to soils have also been reported. Moreno-Cornejo et al. [32] described that net N immobilization was generated after low pepper residue input, while net N mineralization was stimulated following high residue incorporation. Cheng et al. [33] also suggested that microbial N immobilization could be stimulated when an input of simple C sources was greater than 0.5 g C kg−1. These studies focused solely on the effects of C/N ratios or the application rates of organic amendments on soil N mineralization–immobilization processes. However, few studies have investigated the two factors simultaneously and their combined effects. In addition, there are fewer available studies on decreasing NO3− loss and consequently enhancing soil N retention capacity by adding organic amendments in calcareous purple soils. Therefore, with distinct quantity and quality, the impact that organic amendments will have on the soil N mineralization or N immobilization process needs to be further explored.

The objectives of this study were to investigate the effects of C/N ratios and application rates on soil N dynamic changes from organic amendments. We hypothesized that the quality and quantity of amendments could affect the soil N mineralization and immobilization processes. With high C/N residue addition, soil N immobilization would be enhanced and reinforced by higher application rates, thus decreasing the risk of reactive N loss in calcareous soil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soils

The studied soil, collected from the Yanting Agro-Ecological Station of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Sichuan Province (31°16′ N, 105°28′ E), is classified as Pup-Orthic Entisols using Chinese soil taxonomy and as Eutric Regosols using FAO soil classification [34]. Local cropping is typical of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) and summer maize (Zea mays). Five cores were taken from the plow layer (0–20 cm) and pooled together to form a composite sample. The soil samples were sieved (<2 mm) to remove visible organic debris and then split into two subsamples, with one for the organic addition incubation experiment (stored at 4 °C) and another for the analysis of edaphic properties after air-drying (kept in a sealed plastic bag). The soil had a pH of 8.3 (at a soil/water ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v)), a water-holding capacity of 48.04%, an organic C content of 8.03 g kg−1, a TN concentration of 0.77 g kg−1, a C/N ratio of 10, and an inorganic N concentration (NH4+ and NO3−) of 33.48 mg kg−1, mainly in the form of NO3−, accounting for 97%.

2.2. Organic Amendments

Rapeseed cake, maize straw, and cypress sawdust were selected as amendments according to their varying C/N ratios. Glucose was an easily decomposable C source and was purchased online. Maize straw came from the remains of the crops after harvest, while rapeseed cake was collected from local farmers and cypress sawdust was obtained from a wood mill.

These amendments were dried at 50 °C for 48 h, milled to <2 mm, and mixed thoroughly. The chemical properties of these organic amendments are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of organic amendments for the incubation experiment (dry-weight basis).

2.3. Laboratory Incubations

The soil samples were pre-incubated in a controlled incubator at 25 °C for one day to stimulate microbial activity and stabilize microbial populations. The soil sample (20 g of soil on a dried basis) was thoroughly mixed with ground rapeseed cake, maize straw, or cypress sawdust in a 250 mL wide-mouth glass bottle. These amendments were applied at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1 soil, respectively. Then, a 2 mL KNO3 solution was applied uniformly on the soil surface with a pipette. The control treatment was soil without amendments but KNO3. According to the conventional practices of local agricultural production, KNO3 was added at a rate of 100 mg N kg−1, equivalent to about 280 kg N ha−1, into the 0–20 cm soil layer. Glucose was dissolved in a KNO3 solution and then applied to the soils. The soil was brought to 60% water-holding capacity with distilled water, and meanwhile, the weight of each bottle was measured. To maintain aerobic conditions, all bottles were covered with plastic film that had been perforated with a needle. They were then kept in a laboratory incubator for 90 days at 25 °C in the dark. During the incubation period, distilled water was supplied every five days to keep the soil moisture constant by weighing the bottles. Destructive sampling of the soil samples was performed at 0.02, 1, 3, 7, 15, 30, 60, and 90 days after KNO3 addition.

In order to detect soil respiration, gas samples were gathered at 1, 3, 7, 15, and 30 days for CO2 analysis. The bottles were opened for 1 h to renew the atmosphere inside. Then, 50 mL of gas samples were collected from the headspace of the bottle with a medical syringe after the bottle had been closed with a silicone stopper and incubated for 6 h. At the same time, another 50 mL of gas was taken from the air around the bottle as the background value of CO2. All gas samples were measured within 24 h after sampling. Finally, three replicate bottles containing the soil and organic amendments were selected for subsequent extraction after the gas sampling. Furthermore, a mixture without gas collection can be immediately extracted with the 2 M KCl solution after its incubation. The experiment treatments consisted of four organic amendments, three application rates, and one control, performed in triplicate for each of the eight sampling dates, resulting in a total of 312 soil samples.

2.4. Analyses

The soil pH was detected with a DMP-2 mV/pH detector (Quark Ltd., Nanjing, China) at a soil/water ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v). The organic C and total N (TN) of soils and organic amendments were measured with an elemental analyzer (vario MACRO cube, Elementar, Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). The incubated soils were extracted with a 2 M KCl solution at a soil/solution ratio of 1:5 (w/v), and they were shaken on a 250 rpm mechanical shaker for 1 h at 25 °C. Then, the extract was filtered and analyzed for the concentration of NH4+ and NO3− by a continuous-flow analyzer (AA3, Bran Luebbe, Norderstedt, Germany). A gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector was used for CO2 concentration detection.

2.5. Calculation and Statistics

The influences of organic amendments on the mineral N dynamics were calculated using the following equation [35,36]:

where is the net N mineralization (mg N kg−1); is the mineral N content from soils treated with organic amendments (mg N kg−1); and is the mineral N content from soils treated with no organic amendments (mg N kg−1). When , it indicates that the soil is predominated by N mineralization. When , it indicates that the soil is predominated by N immobilization.

The CO2 emission was calculated using the following equation [30]:

where is the CO2 emission flux (mg C kg−1 d−1); is the CO2 density under standard conditions (kg m−3); is the valid volume of the glass bottle (m3); is the oven-dry weight of the soil (g); is the change in CO2 concentration; and is the incubation temperature (°C). The cumulative CO2 emissions over the entire incubation period were calculated by linear interpolation of the daily fluxes between the two closest sampling dates.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 26.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significant differences in maximum N immobilization between treatments were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA followed by the least significant difference at the p < 0.05 level. A two-way ANOVA was used to determine the effects of C/N ratios, application rates, and their interaction with net N mineralization. Repeated-measures analyses were applied to measure the net N mineralization, with “time” as the within-subject factor and “treatments” as the between-subject factor. The Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons for “time” and the “time × treatment” interaction were used to identify the differences among treatments at each time. Figures were created with Origin 2018.

3. Results

3.1. CO2 Emission

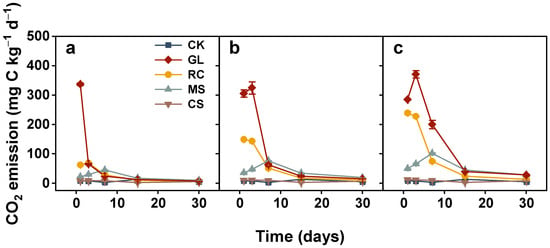

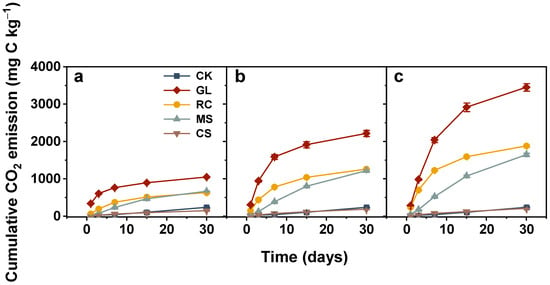

The CO2 emissions from soils treated with organic amendments were significantly higher compared with CK except for cypress sawdust (Figure 1). For rapeseed cake, CO2 production declined rapidly during the first 15 days and gradually remained relatively stable till the end. The CO2 emitted from glucose and maize straw-added soils increased from the start of incubation, peaked on the third or seventh day, and dropped sharply with incubation time. The soils incorporated with cypress sawdust had a similar CO2 dynamic to CK, keeping a constant level throughout the entire incubation period. As for cumulative CO2 emissions, they were highest in glucose and lowest in cypress sawdust (Figure 2). The cumulative CO2 emissions among different application rates were 1047.75–3450.75, 628.81–1879.02, 665.39–1646.71, and 148.33–206.27 mg C kg−1 in soils treated with glucose, rapeseed cake, maize straw, and cypress sawdust, respectively, at the end of incubation.

Figure 1.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emission from soils treated with various organic amendments with different application rates during the 30-day incubation experiment. Note: CK, soil without amendments; GL, glucose; RC, rapeseed cake; MS, maize straw; CS, cypress sawdust. (a–c) Organic amendments applied at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1, respectively. Error bar represents standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Cumulative CO2 emissions from soils treated with various organic amendments with different application rates during the 30-day incubation experiment. Note: CK, soil without amendments; GL, glucose; RC, rapeseed cake; MS, maize straw; CS, cypress sawdust. (a–c) Organic amendments applied at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1, respectively. Error bar represents standard error of the mean (n = 3).

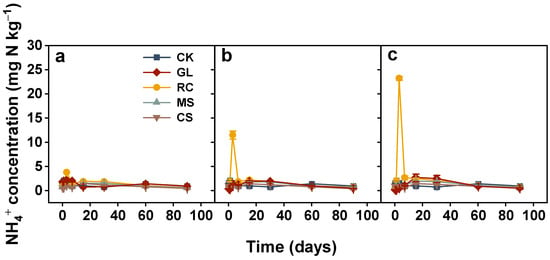

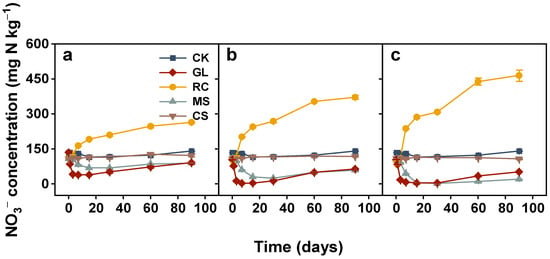

3.2. Soil Mineral Nitrogen

The soil NH4+ concentration showed little change during incubation when soil was amended with maize straw, cypress sawdust, and glucose regardless of application rates (Figure 3). In rapeseed cake treatments, NH4+ concentration increased sharply from the start of the experiment, peaked on the third day, and decreased dramatically with incubation time. And its NO3− concentration was greater than CK from the third day and persistently increased with time (Figure 4). Compared to the CK treatment, increases in NO3− concentration of 123.07, 230.82, and 324.07 mg N kg−1 under 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1, respectively, were observed at the end of incubation. However, the NO3− concentrations from maize straw and glucose were lower than CK for the incubation periods. Glucose-induced NO3− concentration dropped sharply and gradually increased from the 15th day onwards. The soils treated with maize straw exhibited a similar trend to glucose. At the end of the experiment, decreases in NO3− concentration were shown to be 51.39, 82.4, and 120.47 mg N kg−1 for the 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1 maize straw-added soils compared to CK. In addition, NO3− concentration from cypress sawdust had no significant change throughout the entire incubation (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Changes in ammonium (NH4+) concentration in soils treated with various organic amendments with different application rates during the 90-day incubation experiment. Note: CK, soil without amendments; GL, glucose; RC, rapeseed cake; MS, maize straw; CS, cypress sawdust. (a–c) Organic amendments applied at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1, respectively. Error bar represents standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Changes in nitrate (NO3−) concentration in soils treated with various organic amendments with different application rates during the 90-day incubation experiment. Note: CK, soil without amendments; GL, glucose; RC, rapeseed cake; MS, maize straw; CS, cypress sawdust. (a–c) Organic amendments applied at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1, respectively. Error bar represents standard error of the mean (n = 3).

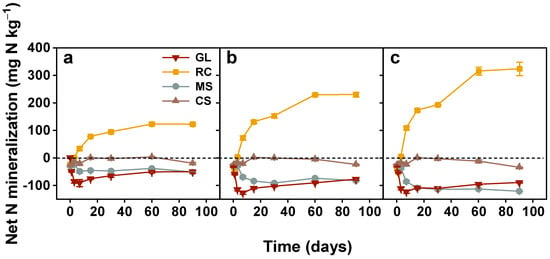

3.3. Net N Mineralization

The mineral N content was generally in NO3− form in the soils; consequently, net N mineralization followed the same trend as NO3− concentration. Statistical analysis showed that soil net N mineralization from these organic amendments was significantly affected by C/N ratios (p < 0.001), application rates (p < 0.001), and their interaction (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Two different and distinct N mineralization patterns were produced after organic amendments were added (Figure 5). The soils with rapeseed cake (C/N, 7) showed a continuous increase in N mineralization over the incubation time. On the contrary, N immobilization was stimulated by glucose, maize straw (C/N, 119), and cypress sawdust (C/N, 506) from the onset of the experiment.

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA analysis showing the effects of C/N ratios and application rates on soil net N mineralization after 90 days of incubation.

Figure 5.

Net N mineralization of added organic amendments with different application rates during the 90-day incubation experiment. Note: GL, glucose; RC, rapeseed cake; MS, maize straw; CS, cypress sawdust. (a–c) Organic amendments applied at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1, respectively. Error bar represents standard error of the mean (n = 3).

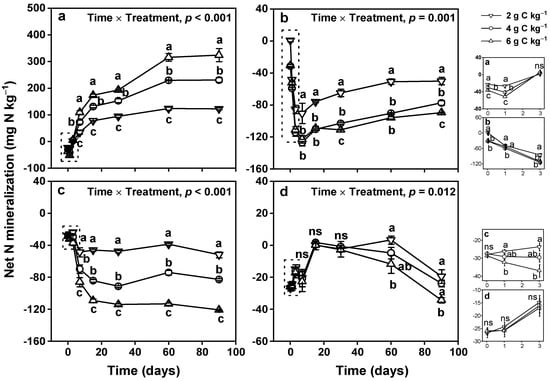

The repeated-measures analysis (Figure 6) indicated that the net N mineralization from rapeseed cake was significantly different among application rates at each sampling date, except on the third day (p < 0.05). At the end, net N mineralization from 6 g C kg−1 was 323.82 mg N kg−1, which is 1.4 times and 2.6 times higher than the 4 and 2 g C kg−1, respectively. The net N immobilization from glucose-added soils increased dramatically and reached the maximum on the seventh day; however, there was no significant difference between 4 and 6 g C kg−1 (p > 0.05) (Table 3). Then, a continuous decrease in N immobilization was observed for the rest of the incubation time. The maize straw exhibited a similar tendency to glucose, with its respective maximum N immobilization at 2, 4, and 6 g C kg−1 being 51.73, 91.31, and 120.78 mg N kg−1. The net N immobilization was not affected by application rates in cypress sawdust for the initial 30 days, with a maximum of 26 mg N kg−1 immobilized compared to unamended soils. However, net N immobilization varied significantly with application rates in the last 60 days.

Figure 6.

Net N mineralization with different application rates from (a) rapeseed cake, (b) glucose, (c) maize straw, and (d) cypress sawdust during the 90-day incubation. Differences between treatments over time (repeated-measures analysis) are also indicated. Different letters indicate a significant difference between application rates at each sampling date (p < 0.05); ns, no significant difference. The small figures on the right represent the regions with a black dotted line and show the significance among application rates during the first 3 days. Error bar represents standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Table 3.

Maximum N immobilization from added organic amendments with different application rates during the 90-day incubation.

4. Discussion

Our research has demonstrated that the quality and quantity of organic amendments could significantly influence soil N mineralization–immobilization processes. The application of organic amendments with a high C/N ratio and high application rate is more conducive to increasing soil N immobilization, thereby reducing the risk of reactive N loss through leaching.

The application of these amendments induced two distinct N mineralization patterns. A net N mineralization process was stimulated by rapeseed cake with a C/N of 7; on the contrary, the increase in net N immobilization occurred in soils amended with high C/N maize straw (C/N, 119) and cypress sawdust (C/N, 506). The low C/N organic residue (rapeseed cake) contained a high N content (66.34 g kg−1) and thus could release amounts of N when applied to soils; however, the high C/N residues with a low N availability (maize straw, 3.76 g kg−1, cypress sawdust, 1.02 g kg−1) could not meet the microbial demand for N and thus would assimilate available mineral N from soils (Table 1) [25,26]. Therefore, N immobilization rather than N mineralization occurs when soils are amended with high C/N organic residues. The C/N ratios of added amendments have usually been regarded as an important factor for regulating soil N mineralization–immobilization processes [19,37], which can serve as a reliable indicator for assessing the N dynamic changes following their incorporation into soils. To meet the demands of agricultural management, suitable organic amendments can be selected for either providing N fertilizer for crops with low C/N residues or enhancing N retention capacity in soils with high C/N amendments.

Our investigations have shown that glucose can immobilize more mineral N than maize straw and cypress sawdust regardless of application rates, and this is consistent with the findings of Qiu et al. [38], who noted that amendment with glucose increased NO3− immobilization by 2.65 times compared to maize straw at the end of their experiment. The reason for this consequence is probably related to the discrepancy of C availability in organic amendments, which can be indirectly proved by total CO2 emissions (Figure 2), being significantly highest in glucose-amended soils. Glucose, an easily decomposing C source containing no cellulose or lignin, can provide significant amounts of available C for microorganisms, thus retaining more N in soils [39]. However, a recalcitrant C source with high lignin content, like cypress sawdust, was highly resistant to microbial decomposition because of its complicated structure and consequently had less stimulation on N immobilization [40]. Although cypress sawdust was applied at 6 g C kg−1, its maximum N immobilization was merely 34.24 mg N kg−1, accounting for 1/4 of maize straw with the same C content addition (Table 3). Therefore, organic amendments with a high C/N ratio and high C availability should be selected when applied in fields to increase N retention capacity.

Net N mineralization or immobilization following the incorporation of these amendments increased with the increase in application rates. These results indicated that the increase in organic application could intensify soil N mineralization or the N immobilization process, which has been reported in previous studies [19]. Higher rates of application from Gliricidia increased more mineral N in the soil compared with a lower application, and more available N was also immobilized by higher farmyard manure addition [41]. However, an inconsistent result was shown by Cheng et al. [33], who found that animal manure addition did not stimulate microbial N immobilization regardless of the amount of manure input. The reason for this contradiction could probably be related to the low C/N of manure with high N content. Hence, N mineralization rather than N immobilization occurred in soils amended with animal manure [42,43]. Enhancing the intensity of these N transformation processes may be associated with soil microorganisms, such as fungi and bacteria. Some reports have suggested that their N immobilization activities would increase with the organic addition rate. With the increase in SOC content in soils, both fungi and bacteria can immobilize more NO3− [22]. This can be demonstrated by the cumulative CO2 emission in our study (Figure 2). A higher application of organic amendments can provide enough C sources to stimulate microorganism growth, thus enabling them to more effectively participate in N transformation processes [44].

Our results showed that there was no significant difference in the maximum N immobilization between 4 and 6 g C kg−1 in glucose treatments. This was because the N substrate had almost been consumed in the soil. As shown by the depletion of NO3− at day 7 (Figure 4b,c) and the continuous increase in cumulative CO2 emissions after day 7 (Figure 2b,c), more mineral N can be immobilized if sufficient NO3− substrate is supplied. The low availability of mineral N under a higher application of organic amendments probably hindered microbial N immobilization. A similar result was mentioned in Mohanty et al.’s study [41], who found that a higher application of farmyard manure would immobilize more N if there was enough mineral N existing in soils. Ma et al. [45] proposed that the incorporation of starch into soil could not reach its N immobilization potential, and significant N immobilization would occur if there was available inorganic N for microbes. The present investigation indicated that N immobilization may be limited by mineral N availability in soils in addition to the application rates of organic amendments.

The application of cypress sawdust with different application rates had few effects on net N immobilization during the first 30 days, which could be verified by similar CO2 emissions from these treatments. This result contradicted the widespread view that a stronger stimulation of microbial N immobilization was associated with higher application rates [12]. This inconsistent consequence may be ascribed to the high lignin content in sawdust, likely highlighted by the relatively high aromatic fraction observed in the 13C-CPMAS NMR spectra [31], which is resistant to microbial decomposition and has a slower nutrient release. However, a significant difference in net N immobilization was observed among application rates during the final 60 days. An explanation can be obtained from the report of Reichel et al. [40], who found that no clear decomposition trend occurred in the spruce sawdust amendment treatment until 49 days. An adequate experimental period with organic residue may be in favor of the regulation of recalcitrant organic sources on microbial N immobilization by changing the microbial community structure [46], which can shift from bacteria using labile substrates to fungi that can decompose recalcitrant sources [47,48].

The influence of organic amendment application on inorganic N dynamics (net N mineralization or immobilization) was calculated by the difference between the amount of inorganic N in the amended and unamended soils [20,49]. This methodology gives no information with regard to gross N mineralization and immobilization processes. Future research should focus on the various mineral N dynamic changes with more novel methods, such as 15N-labeled technology and acetylene inhibition methods. Microbes, including fungi and bacteria, are important participants in soil N mineralization–immobilization processes [44,50,51]. Given the distinct physiologies of fungi and bacteria, their respective N immobilization may respond differently to organic amendments [52,53]. New technologies such as high-throughput sequencing and AS-SIP should be used in subsequent studies to explore the roles of microbes in the N mineralization–immobilization process as much as possible.

5. Conclusions

The C/N ratios of organic amendments could be an indicator for assessing the N dynamic changes following their incorporation into soils. The results have revealed that the application of low C/N organic amendments (e.g., rapeseed cake) could stimulate net N mineralization, whereas net N immobilization would be induced by the amendments with a high C/N ratio (e.g., maize straw and cypress sawdust). Higher application rates could reinforce these N transformation processes in calcareous cropland soil. Organic amendments with a high C/N ratio and high C availability should be selected when applied in fields to increase N retention capacity. In addition, mineral N availability should be considered for promoting soil N immobilization under a higher application of organic amendments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.H. and B.Z.; methodology: Y.H. and B.Z.; formal analysis: Y.H. and B.Z.; investigation: Y.H.; writing—original draft: Y.H.; writing—review and editing: Y.H. and B.Z.; project administration: B.Z.; funding acquisition: B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20107).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tilman, D.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature 2002, 418, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. A plan for efficient use of nitrogen fertilizers. Nature 2017, 543, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G. Nitrogen fertilization mitigates global food insecurity by increasing cereal yield and its stability. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 34, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Gu, B.J.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Ju, X.T. Significant accumulation of nitrate in Chinese semi-humid croplands. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, X.T.; Xing, G.X.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Liu, X.J.; Cui, Z.L.; Yin, B.; Christie, P.; Zhu, Z.L.; et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3041–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.H.; Shi, Y.; Groffman, P.M.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Zhu, Y.G. Centennial-scale analysis of the creation and fate of reactive nitrogen in China (1910–2010). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 2052–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, R.; Kunal; Moulick, D.; Bárek, V.; Brestic, M.; Gaber, A.; Skalicky, M.; Hossain, A. Sustainable strategies to limit nitrogen loss in agriculture through improving its use efficiency—Aiming to reduce environmental pollution. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.X.; Dai, S.Y.; Meng, L.; He, M.Q.; Wang, X.G.; Cai, Z.C.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, J.B.; Nardi, P.; Müller, C. Effects of 18 years repeated N fertilizer applications on gross N transformation rates in a subtropical rain-fed purple soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 189, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhu, B.; Kuang, F.H. Reducing interflow nitrogen loss from hillslope cropland in a purple soil hilly region in southwestern China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2012, 93, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yao, Z.Y.; Hu, D.N.; Bah, H. Effects of substitution of mineral nitrogen with organic amendments on nitrogen loss from sloping cropland of purple soil. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, H.; Nishio, T. Immobilization and remineralization of N following addition of wheat straw into soil: Determination of gross N transformation rates by 15N-ammonium isotope dilution technique. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Elrys, A.S.; Zhang, H.M.; Tu, X.S.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.B.; Cai, Z.C. How does organic amendment affect soil microbial nitrate immobilization rate? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Wang, J.; Cao, M.M.; Chen, Z.X.; Tu, X.S.; Elrys, A.S.; Jing, H.; Wang, X.Z.; Cai, Z.C.; Müller, C.; et al. Awakening soil microbial utilization of nitrate by carbon regulation to lower nitrogen pollution. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 362, 108848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, X.C.; Luo, J.F.; Li, Y.; Lindsey, S.; Shi, Y.L.; He, H.B.; Zhang, X.D. Effects of maize residue return rate on nitrogen transformations and gaseous losses in an arable soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 211, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Huang, B.; Lu, C.Y.; Su, C.X.; Song, L.L.; Zhao, X.H.; Shi, Y.; Chen, X.; Fang, Y.T. Effects of ryegrass amendments on immobilization and mineralization of nitrogen in a plastic shed soil: A 15N tracer study. CATENA 2021, 203, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Yamamuro, S. Fate of nitrogen derived from 15N-labeled plant residues and composts in rice-planted paddy soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2001, 47, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domouso, P.; Pareja-Sánchez, E.; Calero, J.; García-Ruiz, R. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization of common organic amendments in olive grove soils. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinsoutrot, I.; Recous, S.; Bentz, B.; Linères, M.; Chèneby, D.; Nicolardot, B. Biochemical quality of crop residues and carbon and nitrogen mineralization kinetics under nonlimiting nitrogen conditions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sloot, M.; Kleijn, D.; De Deyn, G.B.; Limpens, J. Carbon to nitrogen ratio and quantity of organic amendment interactively affect crop growth and soil mineral N retention. Crop Environ. 2022, 1, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazicki, P.; Geisseler, D.; Lloyd, M. Nitrogen mineralization from organic amendments is variable but predictable. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Zeng, Z.Q.; Song, Z.P.; Wang, F.Q.; Tian, D.S.; Mi, W.H.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.S.; Song, L.; Yang, Z.K.; et al. Vital roles of soil microbes in driving terrestrial nitrogen immobilization. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 1848–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; He, H.B.; Zhang, X.D.; Yan, X.Y.; Six, J.; Cai, Z.C.; Barthel, M.; Zhang, J.B.; Necpalova, M.; Ma, Q.Q.; et al. Distinct responses of soil fungal and bacterial nitrate immobilization to land conversion from forest to agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 134, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, X.L.; Shi, P.L. Correlation between CO2 efflux and net nitrogen mineralization and its response to external C or N supply in an alpine meadow soil. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Baldock, J.A.; Dalal, R.C.; Moody, P.W. Decomposition dynamics of plant materials in relation to nitrogen availability and biochemistry determined by NMR and wet-chemical analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 2045–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Yuan, L.; Ma, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.D.; He, H.B.; Chen, X. Effects of N fertilization and maize straw on the transformation and fate of labeled (15NH4)2SO4 among three continuous crop cultivations. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.B.; Müller, C.; Wang, S.Q. 15N tracing study to understand the N supply associated with organic amendments in a vineyard soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.J.; Blackmer, A.M. Residue decomposition effects on nitrogen availability to corn following corn or soybean. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1995, 59, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, N.; Xu, M.G.; Wang, S.Q.; Zhang, J.B.; Cai, Z.C.; Cheng, Y. The influence of long-term animal manure and crop residue application on abiotic and biotic N immobilization in an acidified agricultural soil. Geoderma 2019, 337, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Tan, A.; Chen, K.; Pan, Y.M.; Gentry, T.; Dou, F. Effect of cover crop type and application rate on soil nitrogen mineralization and availability in organic rice production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.B.; Müller, C.; Cai, Z.C. Temporal variations of crop residue effects on soil N transformation depend on soil properties as well as residue qualities. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanomi, G.; Sarker, T.C.; Zotti, M.; Cesarano, G.; Allevato, E.; Mazzoleni, S. Predicting nitrogen mineralization from organic amendments: Beyond C/N ratio by 13C-CPMAS NMR approach. Plant Soil 2019, 441, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Cornejo, J.; Zornoza, R.; Faz, A. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization during decomposition of crop residues in a calcareous soil. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.Y.; Chang, S.X.; Wang, S.Q. The quality and quantity of exogenous organic carbon input control microbial NO3− immobilization: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, T.; You, X.; Gao, M.R. Nutrient release from weathering of purplish rocks in the Sichuan Basin, China. Pedosphere 2008, 18, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, P. Short-term nitrogen transformations in soil amended with animal manure. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsor, G.W.; Pollard, A.G. Carbon-nitrogen relationships in soil. I.—The immobilization of nitrogen in the presence of carbon compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1956, 7, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.T.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Gao, D.C.; Wang, C.; Dai, W.W.; Jiang, P.; Bai, E. Nitrogen, lignin, C/N as important regulators of gross nitrogen release and immobilization during litter decomposition in a temperate forest ecosystem. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 440, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.J.; Ju, X.T.; Ingwersen, J.; Guo, Z.D.; Stange, C.F.; Bisharat, R.; Streck, T.; Christie, P.; Zhang, F.S. Role of carbon substrates added in the transformation of surplus nitrate to organic nitrogen in a calcareous Soil. Pedosphere 2013, 23, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.X.; Xu, C.; Elrys, A.S.; Shen, F.; Cheng, Y.; Chang, S.X. Organic amendment enhanced microbial nitrate immobilization with negligible denitrification nitrogen loss in an upland soil. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, R.; Wei, J.; Islam, M.S.; Schmid, C.; Wissel, H.; Schroder, P.; Schloter, M.; Bruggemann, N. Potential of wheat straw, spruce sawdust, and lignin as high organic carbon soil amendments to improve agricultural nitrogen retention capacity: An incubation study. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, M.; Reddy, K.S.; Probert, M.E.; Dalal, R.C.; Rao, A.S.; Menzies, N.W. Modelling N mineralization from green manure and farmyard manure from a laboratory incubation study. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masunga, R.H.; Uzokwe, V.N.; Mlay, P.D.; Odeh, I.; Singh, A.; Buchan, D.; De Neve, S. Nitrogen mineralization dynamics of different valuable organic amendments commonly used in agriculture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 101, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankole, G.O.; Azeez, J.O. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur mineralization patterns of different animal manures applied on a sandy loam soil–an incubation study. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Li, Z.A.; Zhang, X.D.; Xia, L.L.; Zhang, W.X.; Ma, Q.Q.; He, H.B. Disentangling immobilization of nitrate by fungi and bacteria in soil to plant residue amendment. Geoderma 2020, 374, 114450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zheng, J.S.; Watanabe, T.; Funakawa, S. Microbial immobilization of ammonium and nitrate fertilizers induced by starch and cellulose in an agricultural soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 67, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.S.; He, Z.L.; Zhu, T.B.; Zhao, F.L. Organic-C quality as a key driver of microbial nitrogen immobilization in soil: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2021, 383, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijboer, A.; ten Berge, H.F.M.; de Ruiter, P.C.; Jørgensen, H.B.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Bloem, J. Plant biomass, soil microbial community structure and nitrogen cycling under different organic amendment regimes; a 15N tracer-based approach. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.W.; Zhu, R.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Xu, X.P.; Ai, C.; He, P.; Liang, G.Q.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, P. Effect of high soil C/N ratio and nitrogen limitation caused by the long-term combined organic-inorganic fertilization on the soil microbial community structure and its dominated SOC decomposition. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, M.; Shahbazi, K.; Kharazi, N.; Rezaei, M. The influence of organic amendment source on carbon and nitrogen mineralization in different soils. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 20, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, Y.D.; Uchida, Y.; Araki, H. Roles of soil bacteria and fungi in controlling the availability of nitrogen from cover crop residues during the microbial hot moments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Liu, H.X.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.H.; Zhong, X.B.; Lv, J.L. Contribution of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria to nitrogen transformation in a soil fertilized with urea and organic amendments. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Q.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial–fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Song, L. Advances in the study of NO3− immobilization by microbes in agricultural soils. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).