Abstract

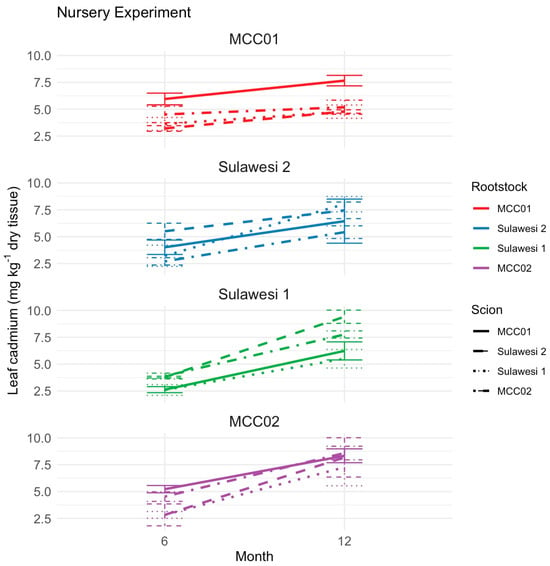

Cadmium (Cd) accumulation in cocoa poses a regulatory challenge for cacao producers in regions with naturally elevated soil Cd, such as Indonesia. This study evaluated the potential of soil-based and plant-based solutions to reduce Cd uptake in cacao. The efficacy of soil amendments was tested with two experiments: (1) a 12-week soil incubation tested lime, biochar, and lime–biochar mixtures at five rates on sandy clay loam and (2) a field trial evaluating zeolite applied at three rates (300, 600, and 900 kg ha−1) with heat or alkali pretreatments. A third experiment evaluated the potential of four cacao genotypes and their rootstock–scion interactions to mitigate Cd uptake over the course of a 12-month nursery trial in Cd-augmented soil. In the incubation study, some lime and biochar treatments produced numerically lower soil Cd concentrations than the control (0.25 mg kg−1), with final means as low as 0.15 mg kg−1, but these differences were not statistically significant in this experiment. Application of zeolite in the field significantly reduced leaf and bean Cd levels (leaf: 0.35–0.50 mg kg−1; bean: 0.25–0.75 mg kg−1) compared to the control (p < 0.01). In the nursery experiment, average increases in leaf Cd concentrations from 6 to 12 months after spiking were lowest in rootstock MCC01 (1.46 mg kg−1; p < 0.001) compared to higher increases in MCC02 (4.16 mg kg−1) and Sulawesi 1 (3.53 mg kg−1), indicating reduced Cd uptake by MCC01 across scions, while scion and interaction effects were not significant. Targeted soil amendments and specific rootstock–scion combinations are promising strategies to reduce Cd concentrations in cacao systems.

1. Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) is a naturally occurring heavy metal present in agricultural soils [1,2,3], and it is subject to regulatory limits in food products, such as cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) and chocolate products, where levels must comply with international standards [1,4]. The EU has implemented regulations on Cd levels, with maximum levels for cocoa mass or cocoa liquor of 0.8 mg kg−1, and allowable limits are progressively decreasing [4]. Cadmium can enter soils through contaminated inputs such as fertilizers, and cacao trees grown in soils with naturally elevated Cd levels can accumulation Cd in cocoa beans [1,2,3]. Soil and plant strategies to manage Cd at the farm scale are needed to meet regulatory thresholds and allow farmers to maintain market access [5]. These strategies are particularly important in Indonesia, the world’s third-largest cocoa producer, with an estimated 1.44 M ha producing 667,300 tons in 2020 [6]. The island of Sulawesi in particular is a key center for production. One notable attribute of Indonesian cocoa beans is their high flavanol content; however, some production areas also have high Cd concentrations in beans [7]. Failure to find solutions could have consequences for Indonesian farmers and the viability of the cocoa industry.

Soil amendments are one viable option to reduce Cd accumulation in cocoa beans, either by modifying soil properties that affect the dominant form of Cd present or by interacting directly with Cd species [2,3,8]. Soil pH plays a crucial role in determining the solubility and bioavailability of Cd in soil, with acidic conditions favoring mobility of the divalent form Cd2+ in soil solution and alkaline conditions promoting Cd immobilization [9]. Lime application can thus reduce Cd bioavailability in acidic soils indirectly, via modification of soil pH. Biochar exhibits high porosity and diverse functional groups on its surface can interact with and stabilize heavy metals through ion exchange and redox reactions [10,11,12]. Similarly, zeolites, a soil amendment derived from clay minerals, have been shown to immobilize Cd in soil and reduce its uptake by crops such as tobacco and rice through multiple mechanisms including ion exchange and modification of soil pH and redox conditions [13,14,15]. Pre-treatment of zeolites with heat or chemical reagents can modify their structure to increase porosity and affinity for cations, enhancing their ability to immobilize Cd [16]. These amendments could reduce available Cd not only alone, but also in combination with one another given the complementarity of direct and indirect mechanisms; for example, a lime-biochar combination was shown to reduce Cd uptake by cacao trees [8]. While lime, biochar, and zeolite show potential in laboratory and field conditions, further research is needed in tropical soils and especially in cacao production systems.

Clone selection, including low-Cd combinations of rootstock and scion varieties, is another promising strategy. Studies have identified a tenfold variation in Cd uptake among nine Colombian rootstocks even over the course of 90 days [5,17]. Another study showed that the Indonesian clones ‘Sulawesi 1’, ‘Sulawesi 2’, and ‘Scavina 6’ differed roughly fivefold in the percentage of Cd translocated from root to shoot [17]. This genetic variation could form the basis for propagation programs to promote clones with low Cd uptake by rootstocks and/or low Cd translocation by scions, allowing farmers to manage Cd on their farms without additional soil amendments. Most screening work has relied on Cd concentrations in leaves and other vegetative tissues as practical indicators of genotype differences, because juvenile trees often do not yet bear pods and several field studies have reported positive relationships between Cd in leaves and Cd in beans and soil [18,19]. Furthermore, rootstock–scion interactions also play a role in Cd uptake, translocation and bean accumulation, showing that grafting could create clonal combinations with Cd reductions beyond the summed effects of their respective rootstocks and scions. Still, research gaps remain, particularly in Southeast Asia: while the impact of rootstocks on Cd uptake has been reported in Colombian cacao clones, systematic data on the screening of local Indonesian clones is still lacking.

This study evaluates practical soil- and plant-based strategies to reduce Cd accumulation in cocoa beans through three agronomic trials. We tested the effects of the soil amendments lime, biochar, and zeolites as well as clonal rootstock–scion combinations on soil, leaf, and bean cadmium concentrations. While many studies have focused on mechanistic aspects of Cd uptake under controlled conditions, fewer have assessed mitigation strategies under nursery and field settings. This research contributes proof-of-concept evidence from Indonesia, a major cocoa-producing country where Cd contamination erodes economic opportunity and market access. We hypothesized that the combined application of lime and biochar would reduce soil Cd availability, that treated zeolite would reduce both leaf and bean Cd concentrations, and that selected rootstock–scion combinations could accumulate lower leaf Cd. Our goal was to generate field- and nursery-based evidence on agronomically relevant approaches that could inform on farm decision-making and help prioritize future research in Indonesian cacao systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

This study consisted of a series of three experiments conducted over a four-year period, including a soil incubation and nursery experiment conducted at MCRC Tarengge (2°33′22″ S 120°47′56″ E), Luwu Timur regency, and a field trial carried out in farmer-owned fields at Bakka village, Sabbang subdistrict, Luwu Utara regency (2°39′12″ S 120°13′37″ E), both on the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia. The average annual rainfall at these locations is 2886 mm, with an average temperature of 29 °C. The soil order is Entisols, with physical and chemical characteristics detailed in Table 1. Soil physical and chemical properties reported in Table 1 were determined as follows: the particle size distribution was measured to determine the sand, silt, and clay fractions; soil pH was measured in a 1:1 soil/water slurry; organic C and total N were determined by combustion; available P and K were measured using ammonium acetate extraction; and cation exchange capacity and base saturation were determined from exchangeable cations extracted at neutral pH. The soil used in the incubation and nursery experiments was a sandy clay loam, and the field trial was conducted on a silt loam.

Table 1.

Soil physical and chemical properties for study experiments.

2.2. Experimental Designs

The soil incubation lasted for twelve weeks. The soil was air-dried, sieved to 2 mm, and thoroughly homogenized prior to treatment. No cadmium was added to the soil. The experiment used field-collected soil with naturally elevated background Cd levels, representative of cacao-growing conditions in Sulawesi. Treatments included agronomic rates of lime and biochar at a 2:1 ratio equivalent to 65.0, 130, 195, 260 and 325 g m−2 of lime; 32.5, 65.0, 97.5, 130 and 162.5 g m−2 of biochar; a combination of the two sets of rates equivalent to 97.5, 195, 292.5, 390 and 487.5 g m−2 of lime and biochar (Carbon Gold Ltd., Bristol, UK); and an unamended control for a total of sixteen (16) treatments each with three replications. The biochar is derived from a combination of woody feedstocks and retains wood-like porosity and has high carbon content (~80%). Soil was mixed with treatments and transferred into 11 L polybags with 35 cm in depth. Soil cores were collected from each container every two weeks over three months, cleaned, air-dried, and analyzed for total and available Cd as described in Section 2.3.

The field trial tested leaf and bean Cd concentration for three pretreatments and three rates of zeolite plus an unamended control for a total of ten (10) treatments. Field soils were not modified prior to amendment application and remained in undisturbed field condition to reflect on-farm practices. The Cd concentration of the soil amendments used in the study was analyzed prior to application. Total Cd levels were 0.010 mg kg−1 in lime, below the detection limit in biochar, and 0.048 mg kg−1 in zeolite. These values are consistent with background levels commonly found in natural materials and are not considered a significant source of Cd input. Pretreatments included heating, NaOH treatment, and no activation. These pretreatments, adapted from other protocols [20,21], are commonly used to remove impurities, adjust pore structure, and modify surface charge of natural zeolites, with the goal of increasing their affinity for heavy metals such as Cd. They involved heating at 300 °C for three hours and cooling to room temperature, or mixing with 1 N NaOH solution and maintaining the suspension at 70 °C for 24 h, then washing with demineralized water and drying at room temperature, respectively. Application rates were 300, 600 and 900 kg ha−1. Each treatment was surface applied to the base of three trees for a total of 30 plots. Zeolite chemical properties are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical properties of zeolite for field trial.

Leaf samples were collected after six months by sampling composite tissues from the upper, middle, and lower canopy. Leaf samples were washed, dried, and ground using a blender. Ripe cacao pods were collected during the harvest seasons in July and November from each tree before bean extraction and sun drying to 7% moisture. All dried leaf and bean samples underwent Cd testing at the Mars Chemical Lab in Makassar using a iCAP RQ Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany).

The nursery experiment focused on changes in leaf Cd concentrations by rootstock and scion combinations of four top-performing Indonesian clones–MCC02, MCC01, Sulawesi 1, and Sulawesi 2. The experiment was conducted over a 21-month period. Field soil (the same soil as in the incubation experiment) was collected, cleaned of any foreign materials, transferred to polybags and transplanted with seedlings from each clone following germination in the nursery. The soil was used in its field-moist condition without drying or sieving, to reflect standard nursery management practices. At 3 months, the seedlings underwent cleft grafting, where each of the four rootstocks was grafted with scions from all four clones, which in combination with four un-grafted seedlings resulted in twenty (20) genotypes. Each genotype was replicated in three sets of three polybags for a total of 180 polybags and 60 experimental units. At six months, each polybag containing 10 kg of fresh soil with 20% moisture was injected with 500 mL of 2 mg L−1 Cd solution prepared from Cd(NO3)2 to elevate the Cd concentration from an average baseline of 0.25 mg Cd kg−1 soil to 1.50 mg Cd kg−1 soil. Leaf samples were collected just prior to the injection at six and again at twelve months. Each set was combined into one composite sample, dried for three days and then ground into a fine powder.

2.3. Cadmium Measurement and Quality Control

Cadmium concentrations in soil, leaf, and bean samples were determined using established extraction and digestion procedures followed by instrumental analysis. For soils, total Cd was measured after acid digestion, and available Cd was quantified following standard Mehlich-3 extraction. Digestions were conducted in closed vessels with the temperature ramped to 190 °C and held for 15–20 min under controlled pressure. For plant tissues, approximately 0.5 g of dried, ground material was digested in a closed-vessel system using concentrated nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide, and Cd was determined by inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

After digestion or extraction, samples were cooled, filtered, and brought to volume with ultrapure deionized water. ICP-based analyses were performed with external calibration using multi-element standards, and instrument performance was verified using internal standards. Certified reference materials for soils and plant tissues from the FAPAS proficiency testing program, laboratory blanks, duplicates, and matrix spike samples were included in each analytical batch to ensure data quality. Cadmium recoveries in reference materials ranged from 97% to 109%, and relative percent differences in duplicates were typically below 10%. The method detection limit for Cd was approximately 0.5 µg kg−1 in plant tissue and 1 µg kg−1 in soil, well below the regulatory maximum level of 0.8 mg kg−1 for Cd in cocoa mass. All reported values met laboratory quality assurance and quality control criteria.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of means, standard errors or standard deviations, analysis of variance (ANOVA), p values, and visualizations were conducted in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), accessed through RStudio version 2024.04.1+748 (Posit PBC, Boston, MA, USA). A combination of one-way and two-way ANOVA models were used to analyze study effects of treatments on Cd concentrations of soil, leaf tissue and beans, with assumption checks performed using the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Levene’s test for variance homogeneity, and Q-Q plot visualization. Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons were applied to identify significant pairwise differences. In case of the soil incubation where normality tests and associated transformations failed, a Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted as a non-parametric alternative.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Incubation

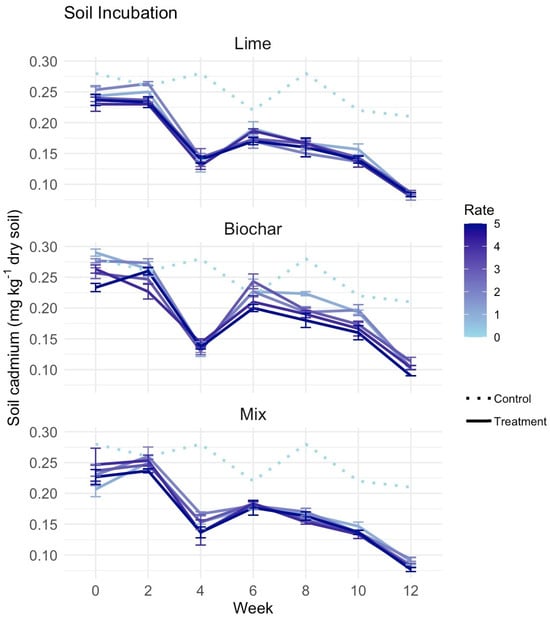

In the twelve-week soil incubation, there were no statistically significant differences in available soil Cd concentrations among lime, biochar, lime–biochar mixtures, and the unamended control. Mean available Cd concentrations in amended treatments were numerically lower than in the control throughout the incubation (Figure 1). In the lime treatment, soil Cd levels decreased within the first two weeks at all application rates, with a drop from approximately 0.25 mg kg−1 to around 0.15 mg kg−1. After week six, the levels stabilized or slightly increased, followed by a final decline by week twelve. The biochar treatment followed a similar pattern, with an initial reduction in soil Cd concentration, followed by a period of relative stability and a final decline. The magnitude of the numerical change in soil Cd was smaller in the biochar treatment than in the lime treatment.

Figure 1.

Soil incubation for twelve weeks testing amendments on available soil cadmium (Cd) (mg kg−1 dry soil) in sandy clay loam field soil. Control was unamended (Rate 0) and the same units for each panel graph. Treatments were five rates of lime (65.0, 130, 195, 260 and 325 g m−2 for Rates 1 to 5), five rates of biochar (32.5, 65.0, 97.5, 130 and 162.5 g m−2 for Rates 1 to 5) and a lime-biochar mixture combining Rates 1 to 5 for each for a total of sixteen treatments. Each treatment included three replications for soil sampling at each time point with standard errors presented.

In the lime–biochar combined treatment, the temporal pattern was similar to that of the individual amendments, with an initial decrease in soil Cd, a mid-period plateau, and a further decrease by week twelve. Mean soil Cd concentrations were lowest at the highest application rates, but differences among rates were relatively small and were not statistically significant.

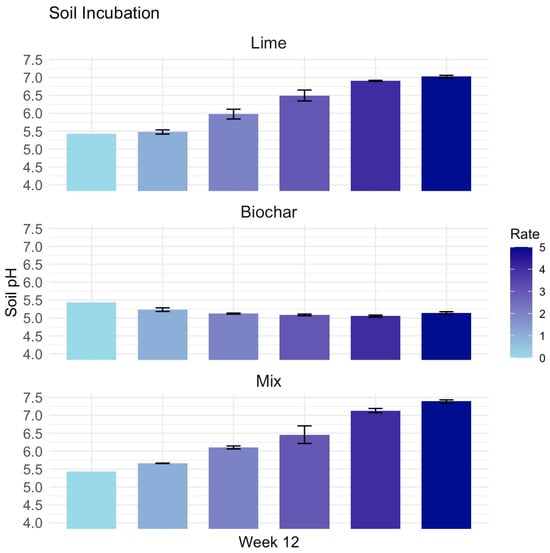

At week 12, soil pH measurements revealed distinct differences among treatments. Lime application significantly increased soil pH in a clear dose-dependent manner (p < 0.001), with the highest rate reaching values above 7.0 (Figure 2). In contrast, biochar had a minimal effect on soil pH, with little change observed across rates. The lime–biochar combination produced a pH response similar to lime alone, indicating that lime dominated the pH effect even when applied in combination with biochar.

Figure 2.

Soil pH at week 12 from a soil incubation experiment testing amendment effects in sandy clay loam field soil. Control was unamended (Rate 0) and pH units are the same across all panel graphs. Treatments included five rates of lime (65.0, 130, 195, 260, and 325 g m−2 for Rates 1 to 5), five rates of biochar (32.5, 65.0, 97.5, 130, and 162.5 g m−2 for Rates 1 to 5), and a lime-biochar mixture combining Rates 1 to 5 of each material. Each treatment was replicated three times; error bars represent standard errors.

3.2. Field Trial

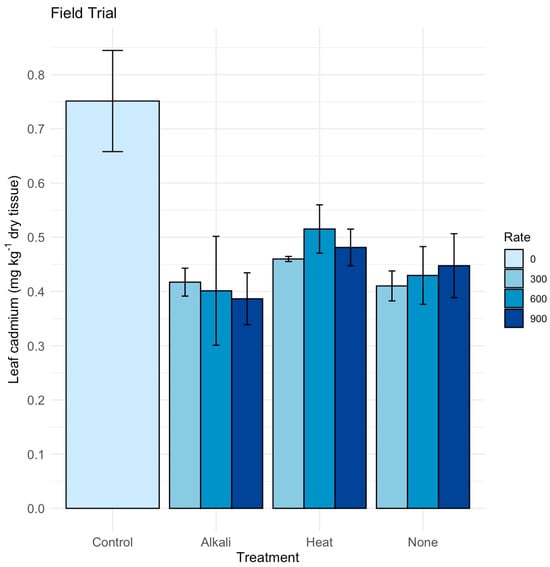

Our field trial testing zeolite pretreatments and rates showed the highest mean leaf Cd concentration of 0.75 mg kg−1 in the unamended control (Figure 3). In contrast, all zeolite treatments showed reduced leaf Cd levels, ranging from approximately 0.35 to 0.50 mg kg−1 across application rates, an effect that was statistically significant (p < 0.01). A post hoc Tukey test identified significantly lower leaf Cd for alkali-treated zeolite and zeolite with no pretreatment at all rates, as well as heat-pretreated zeolite at 300 kg ha−1 (p < 0.05), but with no difference between the control and heat-pretreated zeolite at 600 and 900 kg ha−1. The large differences in leaf Cd between the control and zeolite treatments emphasize that zeolite can play a critical role in reducing leaf Cd levels. In our study, however, the pattern of response across rates and pretreatments did not show a consistent advantage of heat or alkali activation over unmodified zeolite.

Figure 3.

Field trial for twelve months testing zeolite application to soils with different pretreatments of zeolite–alkali, heat or no pretreatment and rates 0, 300, 600 and 900 kg ha−1 on leaf cadmium (Cd) (mg kg−1 dry tissue) in silt loam field soil. At six months after application, leaf samples were collected from three replications with standard errors presented.

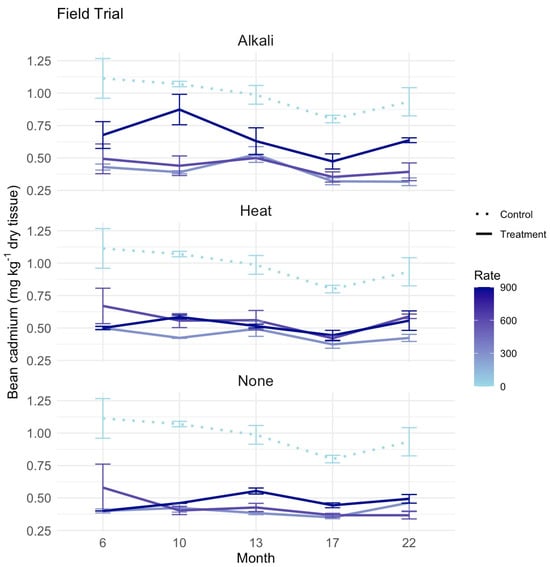

Bean Cd concentrations also varied among zeolite pretreatments and application rates (Figure 4). The unamended control consistently exhibited the highest bean Cd concentration, ranging from approximately 0.80 to 1.20 mg kg−1 dry tissue, while soils treated with zeolite resulted in lower bean Cd concentrations, ranging from 0.25 to 0.75 mg kg−1. Statistical analysis confirmed the significant effect of zeolite application on bean Cd when compared to the unamended control (p < 0.001) with no effect of application rate or pre-treatment. Post hoc Tukey analysis revealed significant differences between the control and several treated combinations including 300 kg ha−1 with alkali (p = 0.028) and no pretreatment (p = 0.023), 600 kg with alkali (p = 0.018) and no pretreatment (p = 0.038) and at 900 kg with alkali pre-treatment only (p = 0.012). Observations showed that the zeolite with alkali pretreatment reached a peak in bean Cd at month 10 for the 600 and 900 kg ha−1 rates at approximately 0.75 mg kg−1 before declining over time. Furthermore, the zeolite with heat pretreatment demonstrated relatively stable bean Cd levels across rates after month 10, fluctuating between 0.40 and 0.60 mg kg−1. Across rates and sampling times, the unmodified zeolite generally had the lowest mean bean Cd levels, remaining below 0.50 mg kg−1, although differences among zeolite pretreatments were not statistically significant. These results demonstrate that zeolite application plays an effective role in reducing bean Cd accumulation, particularly at lower rates and without the need for pretreatment.

Figure 4.

Field trial for 22 weeks testing zeolite application to soils with different pretreatments of zeolite–alkali, heat or no pretreatment and rates 0, 300, 600 and 900 kg ha−1 on bean cadmium (Cd) (mg kg−1 dry tissue) in silt loam field soil. Each treatment included three replications for soil sampling at each time point with standard errors presented.

3.3. Nursery Experiment

Our results present a twelve-month nursery experiment testing various scion and rootstock combinations of the clones MCC01, MCC02, Sulawesi 1, and Sulawesi 2 for changes in leaf Cd concentrations (Figure 5). At the six-month mark, just prior to the injection of Cd solution, leaf Cd levels were relatively low across all combinations, ranging from less than 2.5 to greater than 5.0 mg kg−1. After the Cd solution was injected, leaf Cd levels increased across all scion-rootstock combinations by the twelve-month sampling. Notably, leaf Cd accumulation varied depending on the combination of scion and rootstock used (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Change in leaf cadmium (Cd) (mg kg−1 dry tissue) in a twelve-month nursery experiment with four rootstocks (MCC01, MCC02, Sulawesi 1, Sulawesi 2) and four scions, plus ungrafted controls. Bars show mean Cd concentrations for three replicate experimental units; error bars indicate standard errors.

Based on the analysis of the effects of different rootstocks and scions on Cd leaf levels, significant variation was attributable to rootstock, but not scion. ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rootstock on leaf Cd concentration (p < 0.001). In contrast, the effect of scion was not statistically significant, nor was the interaction between scion and rootstock. A summary of changes in leaf Cd concentrations by rootstock showed that the largest mean increase over time was in plants using MCC02 as rootstock (4.16 mg kg−1), followed by Sulawesi 1 (3.53 mg kg−1), Sulawesi 2 (2.53 mg kg−1), and MCC01 (1.46 mg kg−1). Given that MCC01 showed the smallest increase, it may be the most effective rootstock of the four tested at minimizing Cd uptake. Because this nursery experiment used juvenile plants that did not yet produce pods, we focused on leaf Cd as an indicator of whole-plant Cd uptake rather than a direct measure of bean Cd.

4. Discussion

4.1. Lime and Biochar Produced Non-Significant Reductions in Soil Cd

We hypothesized that the highest rates of lime and biochar would significantly reduce available soil Cd. This hypothesis was not supported by the incubation results because no significant differences in available soil Cd concentrations were detected across treatments. The relatively small number of replicated containers in this experiment limited the statistical power to detect changes in available Cd, which is an important limitation of the study design. Mean available Cd concentrations in amended treatments were lower than in the control, and the pH response to lime was consistent with previous work, but we interpret these incubation results as preliminary rather than conclusive evidence of lime or biochar effectiveness in these soils. Lime showed the largest numerical reduction in available soil Cd on average, while biochar exhibited a slightly smaller numerical change. Lime has been widely observed to increase soil pH, thereby reducing soil Cd availability and, correspondingly, its uptake by cacao. A pot experiment with Cd-augmented soil demonstrated liming increased soil pH by 0.8 leading to a 32% reduction in cacao leaf Cd [22]. Similarly, an 18-month field experiment found liming decreased soil Cd resulting in a threefold decline in leaf Cd [23].

While this study found no significant effect on soil Cd levels after biochar application, other studies have shown mixed effectiveness of biochar. Both feedstock and pyrolysis conditions have a profound impact on the chemical structure of the biochar generated, leading to differences in its behavior in relation to heavy metals and other soil components [10]. López et al. [24] demonstrated that quinoa straw biochar applied at 2% reduced available soil Cd by 71% and cacao leaf Cd by 48%, outperforming biochar derived from oil palm and coffee husk. Ramtahal et al. [8] found biochar reduced soil Cd by 80% at a rate of 752 kg ha−1 under controlled conditions yet, higher rates were necessary to be effective in the field trial.

Contrary to the hypothesis of synergistic effects, the lime-biochar combination performed similarly to lime alone in impacts on both pH and Cd (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Direct interactions of biochar functional groups with Cd2+ in soil, including redox reactions and ion exchange, are strongly affected by soil environmental conditions. While biochar effectively reduced soil Cd when applied alone, the rapid rise in pH in the combination treatment due to lime application could have altered the reactivity of biochar surface chemistry and/or removed Cd2+ ions from solution, reducing the effectiveness of biochar-mediated Cd immobilization. In studies where lime and biochar reduced soil and leaf Cd levels by 50% over 120 days, the addition of lime to biochar may have extended the effects of lime in the root zone through the formation of soluble complexes [25,26]. Different feedstocks and pyrolysis conditions could also have contributed to the inconsistencies in outcomes between studies. Taken together with published studies that have demonstrated significant Cd reductions following lime and biochar application, our results indicate that these amendments remain candidates for Cd mitigation. However, their effectiveness in Indonesian soils needs to be tested in future experiments.

4.2. Zeolite Effective on Leaf and Soil Cadmium

Our hypothesis was that pretreated zeolite at the highest rate would significantly reduce leaf and bean Cd concentrations. The field trial demonstrates zeolite significantly reduced leaf and bean Cd concentrations even at the lowest rates of 300 kg ha−1 and without pretreatment. This result is important from an agronomic perspective because it suggests that, for the zeolite source and soil type used here, farmers may obtain meaningful Cd reductions without the additional cost and complexity of thermal or chemical activation. Mechanistically, the mild heat treatment (300 °C) applied in this study may not have been sufficient to substantially alter zeolite structure, and NaOH activation may have partially saturated exchange sites with Na+ ions. Because we did not directly measure changes in surface chemistry or Cd speciation, these explanations remain hypotheses and highlight the need for complementary mechanistic studies.

Zeolite is effective in soil remediation of heavy metals through ion exchange, adsorption, and redox reactions [27]. Yet the literature reports mixed results of Cd reduction by zeolite. A study with zeolite application at 1% of soil mass in wheat showed a significant reduction in available Cd in neutral and acidic soils [28]. Another study found that zeolite application at a rate of 5 g kg−1 soil improved soil aggregation and nutrient availability, leading to enhanced growth characteristics in corn while significantly decreasing available soil Cd [29]. In one cacao study, zeolite showed no significant impact on extractable soil Cd, while vermicompost reduced Cd levels in Cd-augmented soils, likely due to raising pH [30]. Our results support the potential for zeolite as a soil-based strategy for Cd reduction in Indonesian cacao systems and highlight the importance of matching zeolite applications to soil type and management context, particularly with respect to soil redox conditions and other physicochemical characteristics.

4.3. Rootstock Selection Reduces Leaf Cadmium

Based on the literature, we hypothesized that rootstock and scion combinations would significantly affect leaf Cd concentration. The nursery experiment demonstrated that leaf Cd concentration varied significantly based on rootstock, but not scion or the rootstock–scion interaction. Across all rootstock–scion combinations, leaf Cd concentrations increased after Cd augmentation, with rootstocks showing distinct differences in their contribution to Cd uptake. A significant main effect of rootstock on leaf Cd concentration was evident (p < 0.001), with MCC01 exhibiting the smallest increase in leaf Cd concentration. Previous studies have shown that genotypes with lower Cd in vegetative tissues can also have lower Cd in beans, although the strength of this relationship varies among environments and genetic backgrounds. As a result, the present nursery results should be viewed as an initial screen of rootstock effects on Cd uptake, and MCC01 should be considered a promising candidate for follow-up field trials that directly measure bean Cd [19]. There was no significant effect of scion on Cd accumulation and no significant interaction was observed between scion and rootstock, meaning that grafting different scions with the same rootstock did not influence Cd accumulation beyond the rootstock effect alone.

Little previous research has assessed differences in Cd accumulation among these four clones. Previous work at the same site including these clones identified significant effects of rootstock, scion, and rootstock–scion interaction on leaf Cd in a short-term nursery study [31]. The study reported MCC01 as scion had the lowest Cd accumulation level in high and low Cd soil. Elsewhere, no differences were found in plant Cd concentrations between clones Sulawesi 1 and Sulawesi 2 [17]. Studies of other cacao varieties and other crops have also identified genetic variation in Cd uptake and shown the potential for rootstock-driven Cd mitigation, however. In Colombia, a study quantified rootstock-mediated genetic contributions to Cd uptake, growth, and physiological traits in juvenile cacao plants, detecting moderate heritability. The rootstock effects faded over time, highlighting complex rootstock by scion by soil interactions [32]. In addition, studies of other perennial crops, including apple, have shown that rootstock impacts can influence Cd uptake [26]. Our findings support rootstock selection as a strategy to reduce Cd accumulation in cocoa.

4.4. Study Scope and Future Work

This study was designed primarily to evaluate agronomic performance of mitigation options under nursery and field conditions in Indonesia, rather than to fully resolve the mechanistic pathways that control Cd behavior in soil and plants. We did not quantify Cd speciation, sorption isotherms, or plant physiological responses, which limits our ability to distinguish among mechanisms such as changes in redox status, complexation, or tissue partitioning. Instead, we interpret our findings in the context of existing mechanistic work on lime, biochar, zeolite, and genotype effects, and focus on identifying practical strategies that warrant further investigation. Future studies that combine the most promising interventions identified here with soil chemistry and plant physiology measurements will be important to refine and mechanistically validate mitigation strategies. Although the three experiments were conducted independently, they address complementary components of a broader mitigation strategy: soil amendments in a controlled incubation, zeolite application in a farmer field with direct measurements of bean Cd, and rootstock effects on Cd uptake in a nursery setting. Together, these experiments point toward a combined approach that couples soil-based mitigation with plant-based selection. Testing specific combinations, such as MCC01 rootstock with zeolite or lime on contrasting soil types, will require longer-term field trials that are a logical next step.

5. Conclusions

Cadmium presence in cacao-growing soils presents a challenge for cacao production, particularly in regions like Indonesia. This study explored soil amendments, rootstock and scion combinations, and zeolite application as strategies to reduce soil, leaf, and bean Cd concentrations. In the incubation study, lime and biochar did not significantly change soil Cd concentrations under the conditions tested, although mean values were lower in amended soils than in the control. These results should therefore be viewed as preliminary and interpreted together with other studies that have evaluated these amendments at larger scales. Additionally, zeolite application significantly reduced leaf and bean Cd concentrations, with no significant effect from pretreatment or rates higher than 300 kg ha−1. Zeolite offers a cost-effective and scalable option for ongoing assessment as a soil strategy. Rootstock selection also emerged as a critical factor, with MCC01 showing the smallest increase in leaf Cd concentration among the four rootstocks tested. This suggests that MCC01 may help limit Cd uptake into the plant, but its effect on bean Cd still needs to be confirmed in longer-term field trials. To build on these results and address existing knowledge gaps, future research should address scales both smaller and larger than the scope of the present study. At the micro-scale, a mechanistic understanding of the interactions between these soil amendments when applied in combination, especially across varying redox conditions and soil environments, could inform optimal soil-based solutions. At larger spatial and temporal scales, the soil amendments could be tested in other soil types (e.g., clayey soils) in addition to the sandy clay loam and silt loam soils of Sulawesi tested in this study. The long-term effects (>2 years) of zeolite and its impact on cocoa yield still require monitoring and validation. While these findings provide valuable insights, further research is needed to confirm the long-term effectiveness of these soil and plant strategies under more diverse soil types and farm conditions and to refine their application for widespread adoption in cacao cultivation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and A.W.; methodology, M.M. and A.W.; software, M.M. and S.D.S.K.; validation, M.M. and S.D.S.K.; formal analysis, M.M. and S.D.S.K.; investigation, M.M.; resources, M.M. and A.W.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., J.E.S. and S.D.S.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M., J.E.S. and S.D.S.K.; visualization, S.D.S.K.; supervision, M.M. and A.W.; project administration, A.W.; funding acquisition, A.W. and S.D.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported directly by Mars Wrigley Science & Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the field and laboratory teams Mars Cocoa Research Centers Tarengge and Pangkep for their contributions to this study. We extend our thanks to the farmers at for providing access to their fields and assisting with the field trials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are employed by Mars Wrigley. Otherwise, no other conflicts of interest are reported.

References

- Maddela, N.R.; Kakarla, D.; García, L.C.; Chakraborty, S.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Cocoa-Laden Cadmium Threatens Human Health and Cacao Economy: A Critical View. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello, D.; Chavez, E.; Lauryssen, F.; Vanderschueren, R.; Smolders, E.; Montalvo, D. Soil Properties and Agronomic Factors Affecting Cadmium Concentrations in Cacao Beans: A Nationwide Survey in Ecuador. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderschueren, R.; Argüello, D.; Blommaert, H.; Montalvo, D.; Barraza, F.; Maurice, L.; Schreck, E.; Schulin, R.; Lewis, C.; Vazquez, J.L.; et al. Mitigating the Level of Cadmium in Cacao Products: Reviewing the Transfer of Cadmium from Soil to Chocolate Bar. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Cadmium Dietary Exposure in the European Population. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.R.M.; de Almeida, A.-A.F.; Santos, N.d.A.; Pirovani, C.P. Tolerance Strategies and Factors That Influence the Cadmium Uptake by Cacao Tree. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 293, 110733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Crops and Livestock Products 2022; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dwijatmoko, M.I.; Nurtama, B.; Yuliana, N.D.; Misnawi, M. Characterization of Polyphenols from Various Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Clones During Fermentation. Pelita Perkeb. 2018, 34, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtahal, G.; Umaharan, P.; Hanuman, A.; Davis, C.; Ali, L. The Effectiveness of Soil Amendments, Biochar and Lime, in Mitigating Cadmium Bioaccumulation in Theobroma cacao L. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, N.T.; Ryan, J.A.; Chaney, R.L. Trace Element Chemistry in Residual-Treated Soil: Key Concepts and Metal Bioavailability. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Bolan, N.; Prévoteau, A.; Vithanage, M.; Biswas, J.K.; Ok, Y.S.; Wang, H. Applications of Biochar in Redox-Mediated Reactions. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchimiya, M.; Chang, S.; Klasson, K.T. Screening Biochars for Heavy Metal Retention in Soil: Role of Oxygen Functional Groups. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 190, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology; Lehmann, J., Joseph, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84977-055-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, K.; Reddy, D.D. Zeolites and Their Potential Uses in Agriculture. Adv. Agron. 2011, 113, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zeng, W.; Li, F.; Huang, Y.; Gu, S.; Cai, H.; Zeng, M.; Li, Q.; Tan, L. Effect of Nano Zeolite on the Transformation of Cadmium Speciation and Its Uptake by Tobacco in Cadmium-Contaminated Soil: Nano Zeolite Impact Soil Cd Speciation and Cd Uptake by Tobacco. Open Chem. 2018, 16, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xie, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, G. Effects and Mechanisms of Cd Remediation with Zeolite in Brown Rice (Oryza Sativa). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velarde, L.; Nabavi, M.S.; Escalera, E.; Antti, M.-L.; Akhtar, F. Adsorption of Heavy Metals on Natural Zeolites: A Review. Chemosphere 2023, 328, 138508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariyya, F.; Santoso, T.I.; Abdoellah, S. Absorption of Cadmium and Its Effect on the Growth of Halfsib Family of Three Cocoa Clones Seedling. Pelita Perkeb. 2022, 38, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engbersen, N.; Gramlich, A.; Lopez, M.; Schwarz, G.; Hattendorf, B.; Gutierrez, O.; Schulin, R. Cadmium Accumulation and Allocation in Different Cacao Cultivars. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 678, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Gardini, E.; Arévalo-Hernández, C.O.; Baligar, V.C.; He, Z.L. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Leaves and Beans of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) in Major Cacao Growing Regions in Peru. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuldeyev, E.; Seitzhanova, M.; Tanirbergenova, S.; Tazhu, K.; Doszhanov, E.; Mansurov, Z.; Azat, S.; Nurlybaev, R.; Berndtsson, R. Modifying Natural Zeolites to Improve Heavy Metal Adsorption. Water 2023, 15, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, S.S.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Alghamdi, A.G. Application of Natural and Modified Zeolite Sediments for the Stabilization of Cadmium and Lead in Contaminated Mining Soil. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Bolanoa, J.A. Phytoextractor Species and Dolomitic Lime as Strategies to Manage Cd in Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) and Spinach (Spinacia Oleracea). Available online: https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll23/id/2128 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Ramtahal, G.; Chang Yen, I.; Hamid, A.; Bekele, I.; Bekele, F.; Maharaj, K.; Harrynanan, L. The Effect of Liming on the Availability of Cadmium in Soils and Its Uptake in Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) in Trinidad & Tobago. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2018, 49, 2456–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.E.; Arroyave, C.; Aristizábal, A.; Almeida, B.; Builes, S.; Chavez, E. Reducing Cadmium Bioaccumulation in Theobroma cacao Using Biochar: Basis for Scaling-up to Field. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello, D.; Chavez, E.; Gutierrez, E.; Pittomvils, M.; Dekeyrel, J.; Blommaert, H.; Smolders, E. Soil Amendments to Reduce Cadmium in Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.): A Comprehensive Field Study in Ecuador. Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.E.; Saldarriaga, J.F. Surface Co-Application of Dolomitic Lime with Either Biochar or Compost Changes the Fractionation of Cd in the Soil and Its Uptake by Cacao Seedlings. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 4926–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belviso, C. Zeolite for Potential Toxic Metal Uptake from Contaminated Soil: A Brief Review. Processes 2020, 8, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yuan, H.; Ning, C.; Li, S.; Xia, Z.; Zhu, M.; Ma, Q.; Yu, W. Evaluation of Different Types and Amounts of Amendments on Soil Cd Immobilization and Its Uptake to Wheat. Environ. Manag. 2020, 65, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirahmadi, E.; Ghorbani, M.; Moudrý, J. Effects of Zeolite on Aggregation, Nutrient Availability, and Growth Characteristics of Corn (Zea mays L.) in Cadmium-Contaminated Soils. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, E.; He, Z.L.; Stoffella, P.J.; Mylavarapu, R.; Li, Y.; Baligar, V.C. Evaluation of Soil Amendments as a Remediation Alternative for Cadmium-Contaminated Soils under Cacao Plantations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 17571–17580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.E.; Dorman, M.; Ward, A.; Firl, A. Rootstock, Scion, and Microbiome Contributions to Cadmium Mitigation in Five Indonesian Cocoa Cultivars. Pelita Perkeb. 2023, 39, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Paz, J.; Cortés, A.J.; Hernández-Varela, C.A.; Mejía-de-Tafur, M.S.; Rodriguez-Medina, C.; Baligar, V.C. Rootstock-Mediated Genetic Variance in Cadmium Uptake by Juvenile Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Genotypes, and Its Effect on Growth and Physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 777842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).