Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the SiLOR Gene Family in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

2.2. Identification of SiLOR Genes in Foxtail Millet

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis of Foxtail Millet SiLOR Proteins

2.4. Gene Structure and Conserved Motifs Analysis

2.5. Chromosomal Localization and Expansion Patterns of Foxtail Millet LOR Genes

2.6. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoter Region of Foxtail Millet SiLOR Genes

2.7. Expression Patterns of Foxtail Millet SiLOR Members in Different Tissues

2.8. Foxtail Millet SiLOR Gene Differential Expression Analysis

2.9. Expression Analysis of Foxtail Millet SiLOR Genes

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of SiLOR Gene Family Members in Foxtail Millet

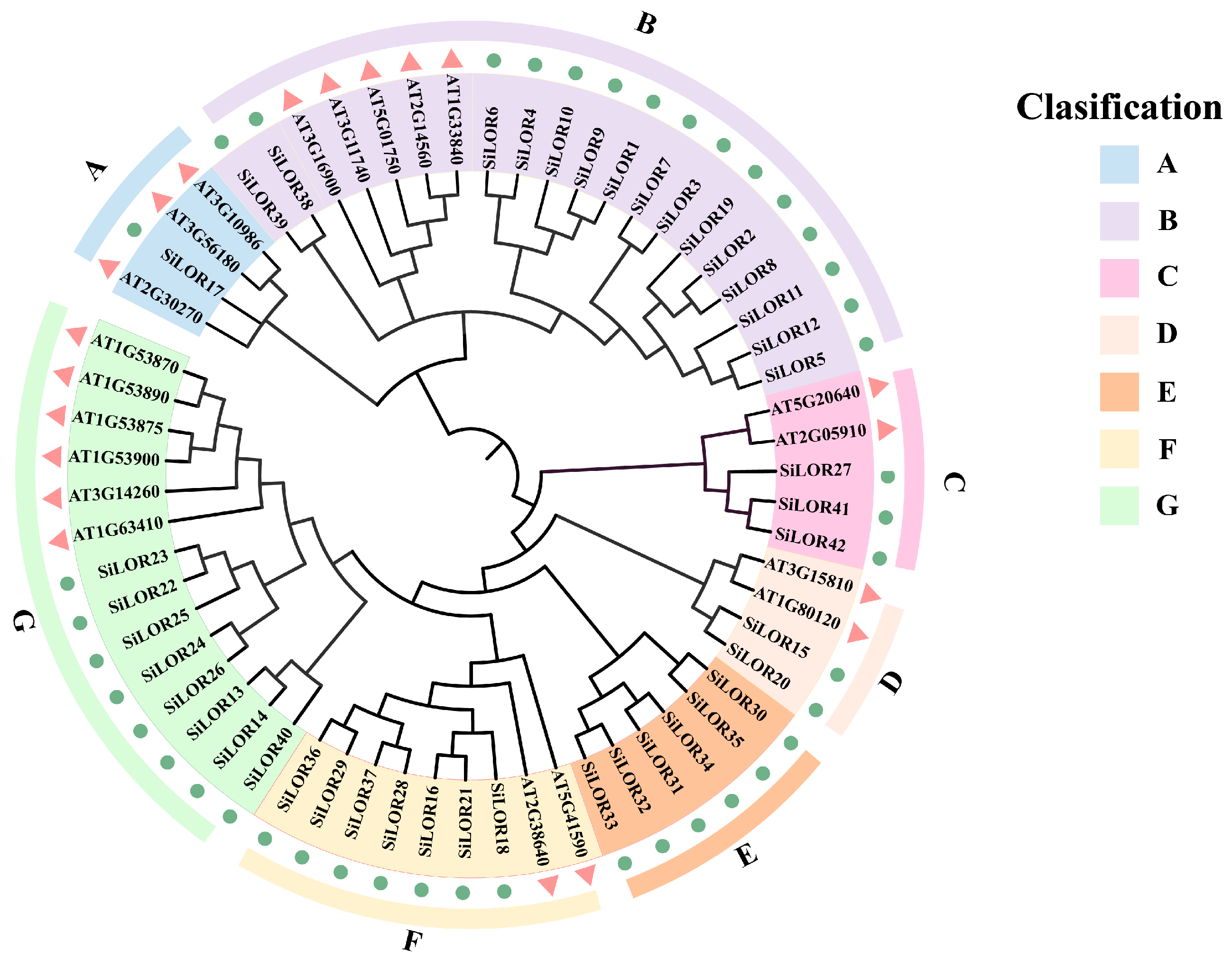

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationships of LOR Proteins in Foxtail Millet and Arabidopsis

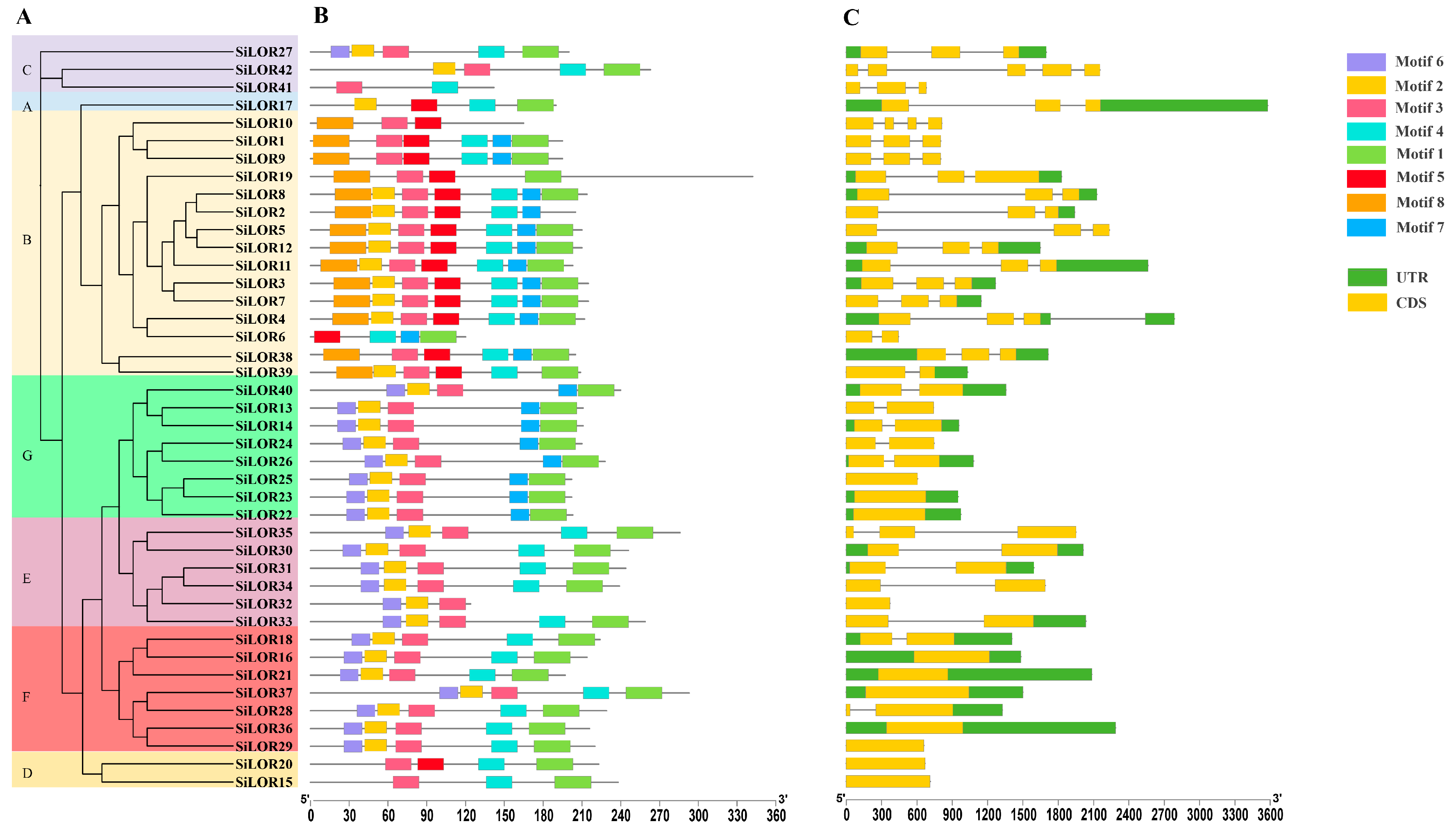

3.3. Gene Structure and Protein Motifs of the SiLOR Gene Family

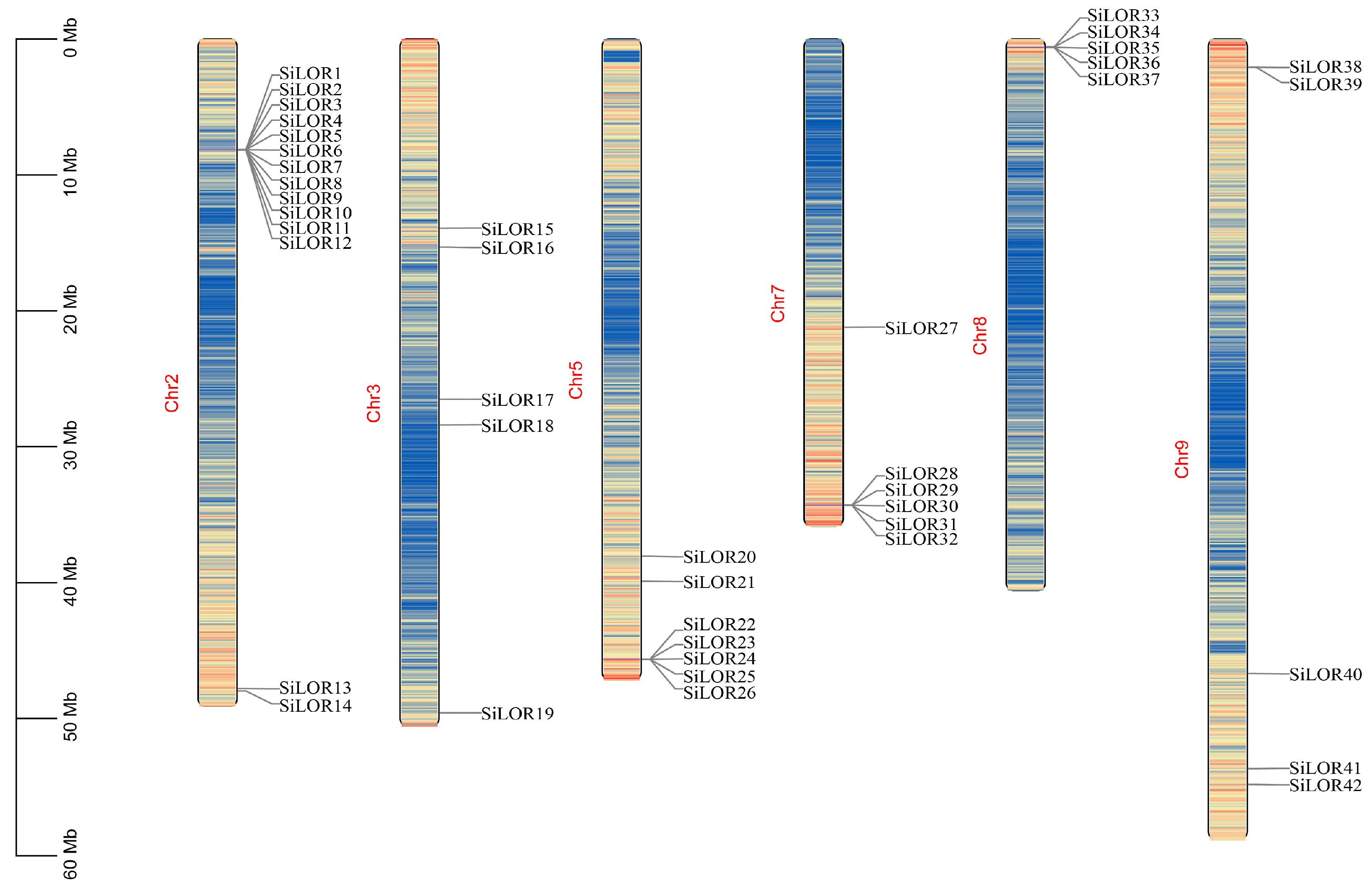

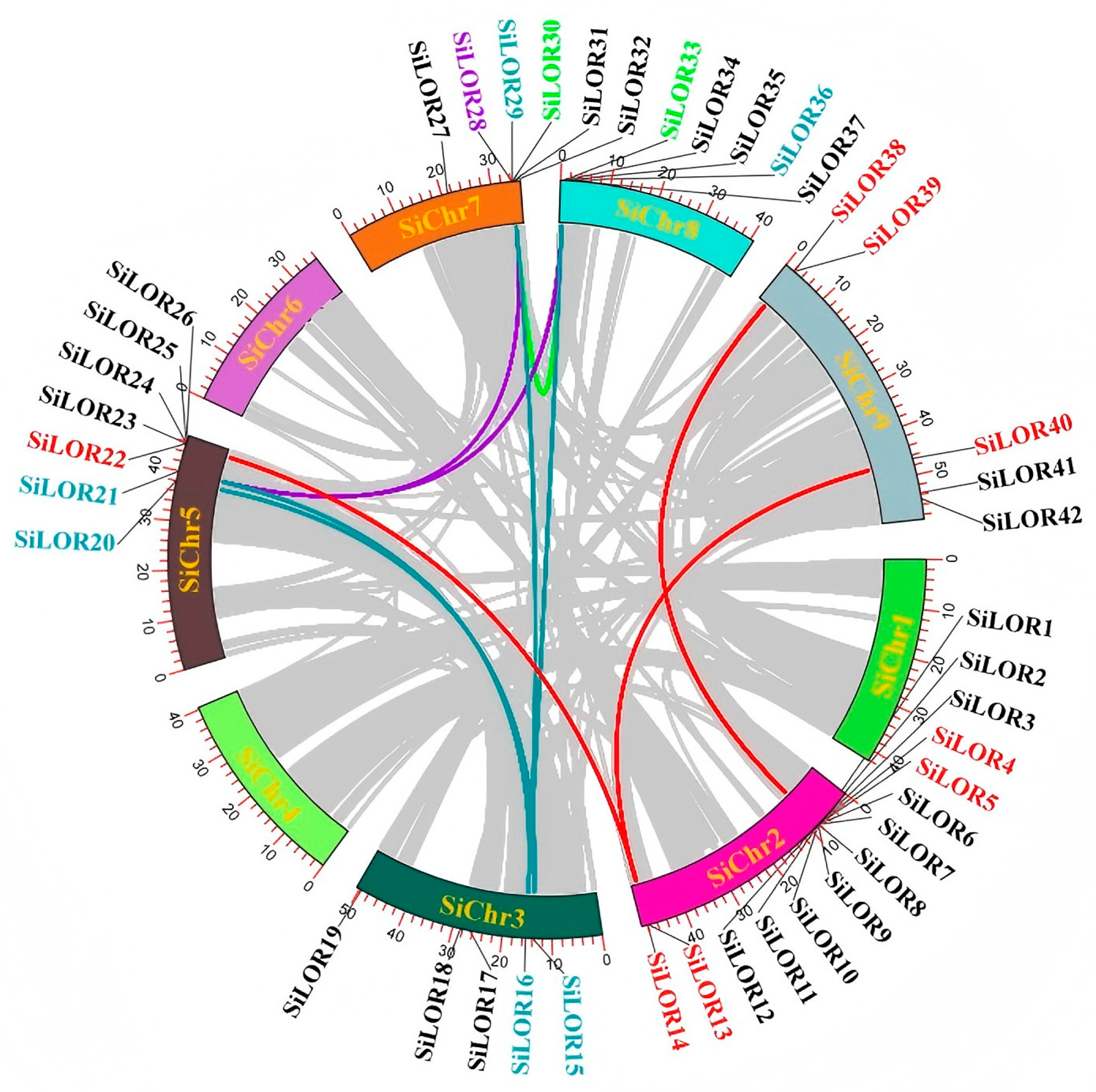

3.4. Distribution of SiLOR Genes in Foxtail Millet Chromosomes and Collinearity Analysis

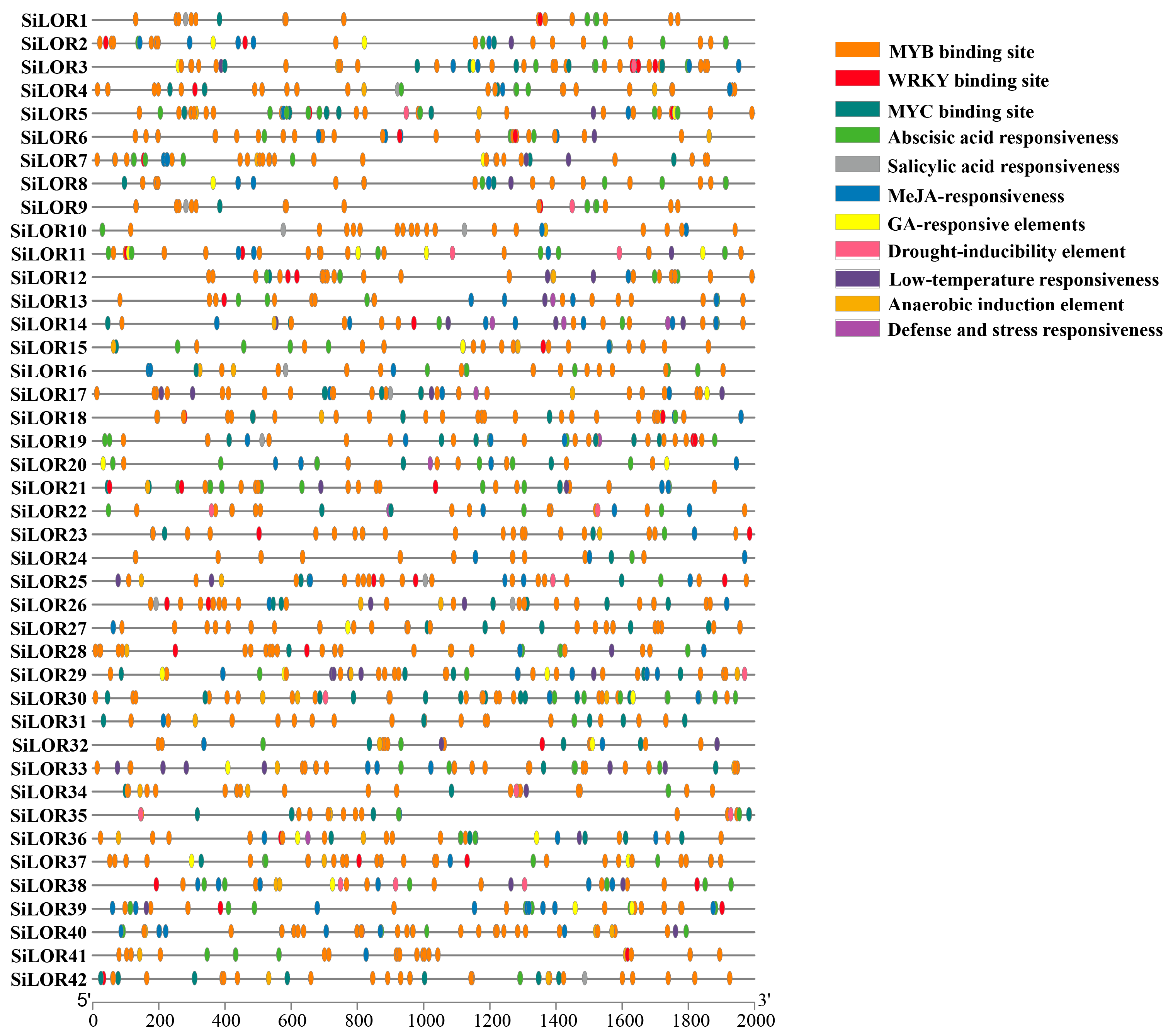

3.5. Cis-Elements Analysis of the SiLOR Promoters

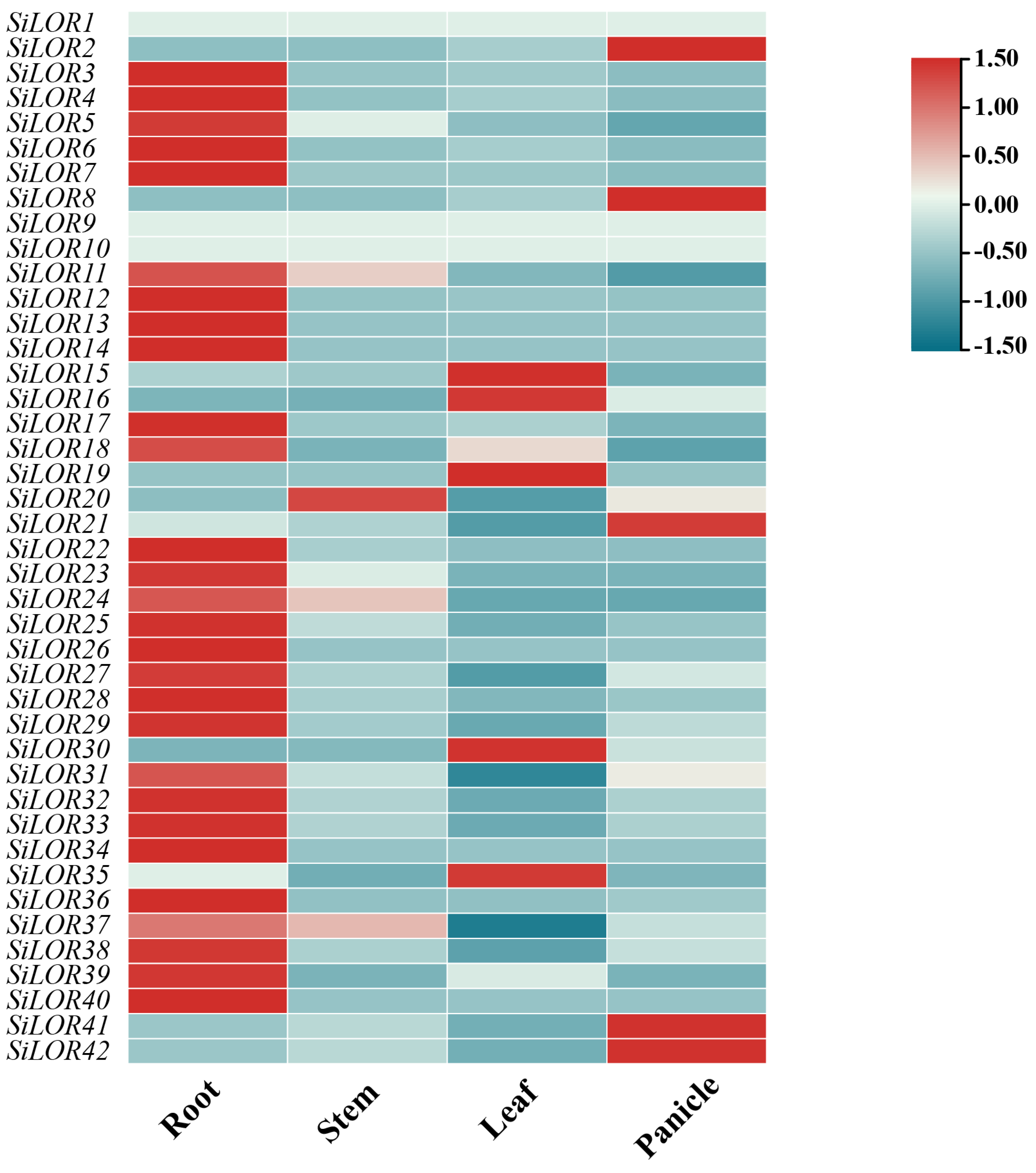

3.6. Expression Analysis of Foxtail Millet SiLOR Genes in Different Tissues

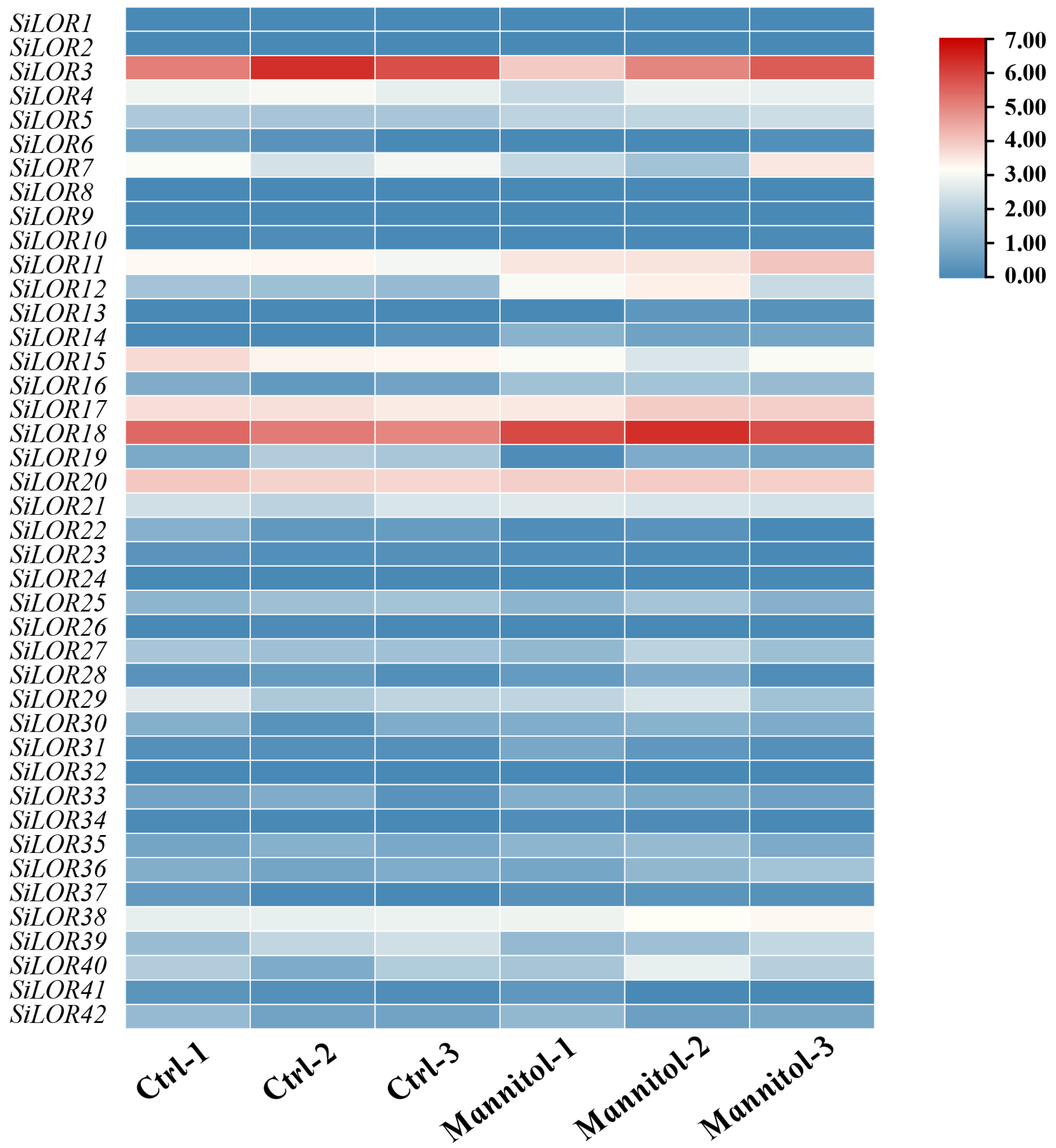

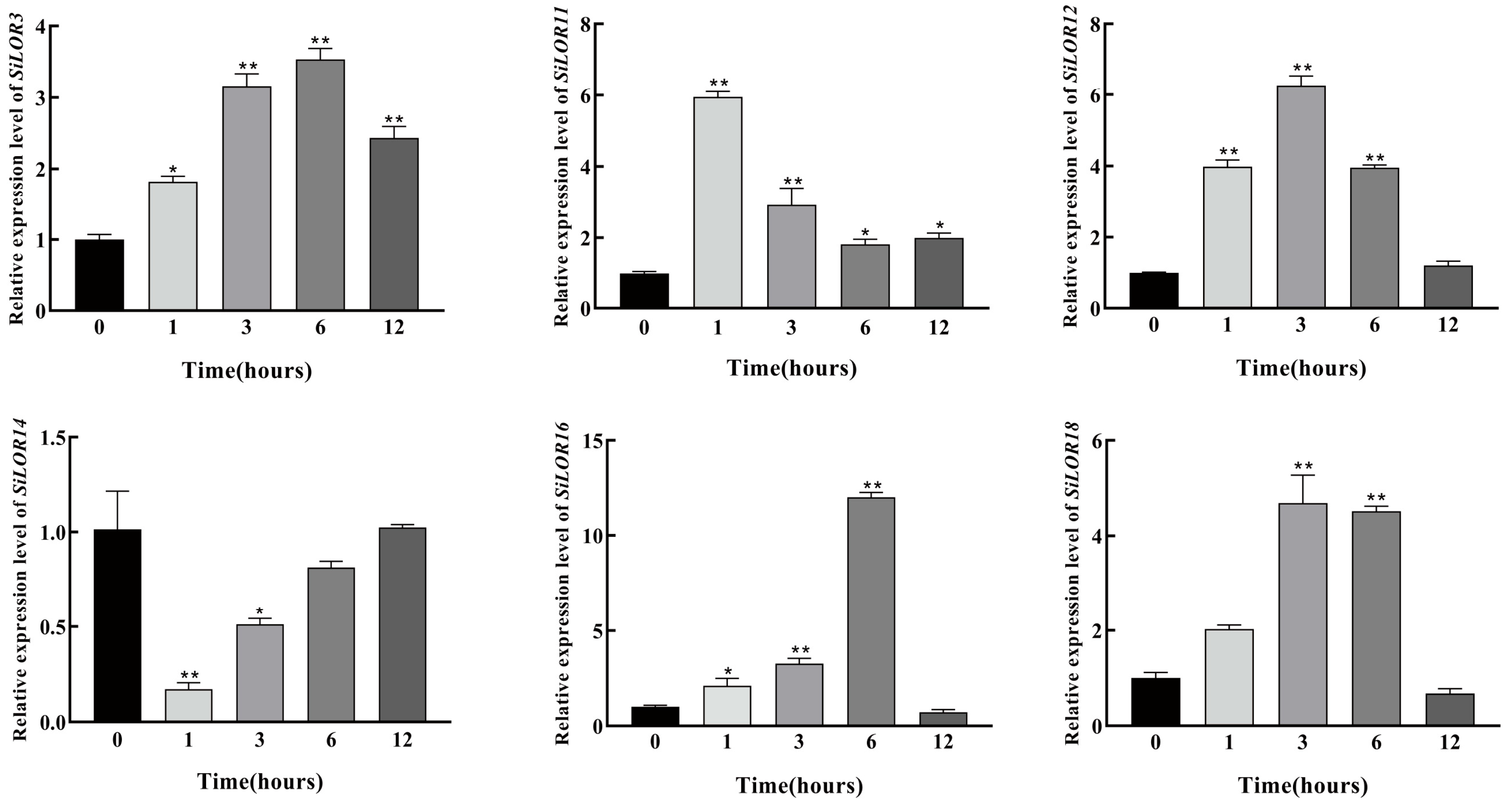

3.7. Expression Analysis of SiLOR Genes in Foxtail Millet Under Mannitol Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suzuki, N.; Rivero, R.M.; Shulaev, V.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohama, N.; Sato, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Transcriptional Regulatory Network of Plant Heat Stress Response. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Finn, R.D.; Sims, P.J.; Wiedmer, T.; Biegert, A.; Söding, J. Phospholipid scramblases and Tubby-like proteins belong to a new superfamily of membrane tethered transcription factors. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Tate, J.; Mistry, J.; Coggill, P.C.; Sammut, S.J.; Hotz, H.R.; Ceric, G.; Forslund, K.; Eddy, S.R.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 32, D281–D288. [Google Scholar]

- Knoth, C.; Eulgem, T. The oomycete response gene LURP1 is required for defense against Hyaloperonospora parasitica in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008, 55, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, J.; Ding, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, G.; Ulhassan, Z.; Wei, J.; Wang, J. Genome-wide investigation and expression profiling of LOR gene family in rapeseed under salinity and ABA stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1197781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, T.L.; Cevik, V.; Beynon, J.L.; Gifford, M.L. Spatial dissection of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcriptional response to downy mildew using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Jeon, H.S.; Kim, H.G.; Park, O.K. An Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor NAC4 promotes pathogen-induced cell death under negative regulation by microRNA164. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricchi, I.; Bertea, C.M.; Occhipinti, A.; Paponov, I.A.; Maffei, M.E. Dynamics of Membrane Potential Variation and Gene Expression Induced by Spodoptera littoralis, Myzus persicae, and Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A. Role of Arabidopsis LOR1 (LURP-one related one) in basal defense against Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 103, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Cao, D.; Yang, H.; Guo, W.; Ouyang, W.; Chen, H.; Shan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Soybean GmLOR Gene Family and Expression Analysis in Response to Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Ul Hassan, M.; Wang, R.; Diao, X.; Li, X. Adaptation of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) to abiotic stresses: A special perspective of responses to nitrogen and phosphate limitations. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Devos, K.M.; Liu, C.J.; Wang, R.Q.; Gale, M.D. Construction of RFLP-based maps of foxtail millet, Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1998, 96, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthamilarasan, M.; Bonthala, V.S.; Khandelwal, R.; Jaishankar, J.; Shweta, S.; Nawaz, K.; Prasad, M. Global analysis of WRKY transcription factor superfamily in Setaria identifies potential candidates involved in abiotic stress signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, C.; Kang, X.; Pei, Z.Q.; Bai, X.; Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, T.G. Identification and expression analysis of MAPK cascade gene family in foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Plant Signal Behav. 2023, 18, 2246228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Han, Y.; Lin, X. Genome-wide identification of AAAP gene family and expression analysis in response to saline-alkali stress in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Quan, Z.; Cheng, S.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.; Xie, M.; Zeng, P.; Yue, Z.; Wang, W.; et al. Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Huang, X.; Zhi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, W.; Chai, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, K.; Lu, H.; et al. A haplotype map of genomic variations and genome-wide association studies of agronomic traits in foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetzen, J.L.; Schmutz, J.; Wang, H.; Percifield, R.; Hawkins, J.; Pontaroli, A.C.; Estep, M.; Feng, L.; Vaughn, J.N.; Grimwood, J.; et al. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gebali, S.; Mistry, J.; Bateman, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Luciani, A.; Potter, S.C.; Qureshi, M.; Richardson, L.J.; Salazar, G.A.; Smart, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D427–D432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Mikael, B.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clement, I.L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathail, C.; Ahamed, A.; Burgin, J.; Cummins, C.; Devaraj, R.; Gueye, K.; Gupta, D.; Gupta, V.; Haseeb, M.; Ihsan, M.; et al. Facing growth in the European Nucleotide Archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D30–D35. [Google Scholar]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, S.B.; Mitra, A.; Baumgarten, A.; Young, N.D.; May, G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2004, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.B. Introns as Gene Regulators: A Brick on the Accelerator Frontiers in genetics. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 672. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, B.Y.; Simons, C.; Firth, A.E.; Brown, C.M.; Hellens, R.P. Effect of 5’UTR introns on gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 2006, 7, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Ni, P.; Dong, W.; Hu, S.; Zeng, C.; et al. The Genomes of Oryza sativa: A history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeger-Lotem, E.; Sattath, S.; Kashtan, N.; Itzkovitz, S.; Milo, R.; Pinter, R.Y.; Alon, U.; Margalit, H. Network motifs in integrated cellular networks of transcription-regulation and protein-protein interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5934–5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhang, H.; Kong, L.; Gao, G.; Luo, J. PlantTFDB 3.0: A portal for the functional and evolutionary study of plant transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D1182–D1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, I.; Herzog, C.; Dawes, M.A.; Arend, M.; Sperisen, C. How tree roots respond to drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, H.; Urao, T.; Ito, T.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoth, C.; Ringler, J.; Dangl, J.L.; Eulgem, T. Arabidopsis WRKY70 is required for full RPP4-mediated disease resistance and basal defense against Hyaloperonospora parasitica. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Sanhueza, R.; Soto-Cerda, B.; Tighe-Neira, R.; Reyes-Díaz, M.; Alvarez, J.M.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Ibáñez, C.; Inostroza-Blancheteau, C. Plant resilience to abiotic stresses: Revealing the role of silicon in drought and metal(loid) tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 4869–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.A. Global Synthesis of Drought Effects on Maize and Wheat Production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terfa, G.N.; Pan, W.; Hu, L.; Hao, J.; Zhao, Q.; Jia, Y.; Nie, X. Mechanisms of Salt and Drought Stress Responses in Foxtail Millet. Plants 2025, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Gene | Phytozome Setaria italica Gene ID | Instability Index | Aliphatic Index | Grand Average of Hydropathicity | Protein Physicochemical Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (aa) | MW (kDa) | pI | ||||||

| 1 | SiLOR1 | Seita.2G088800 | 43.43 | 94.54 | 0.267 | 194 | 21,281.88 | 10.17 |

| 3 | SiLOR3 | Seita.2G089100 | 46.59 | 95.51 | 0.078 | 214 | 23,473.98 | 7.73 |

| 4 | SiLOR4 | Seita.2G089200 | 39.02 | 82.65 | 0.121 | 211 | 23,109.95 | 9.77 |

| 5 | SiLOR5 | Seita.2G089300 | 42.01 | 88.13 | 0.053 | 209 | 22,993.45 | 8.41 |

| 6 | SiLOR6 | Seita.2G089400 | 28.48 | 83.45 | −0.078 | 119 | 13,564.78 | 9.75 |

| 7 | SiLOR7 | Seita.2G089500 | 48.28 | 93.27 | 0.057 | 214 | 23,389.82 | 7.73 |

| 8 | SiLOR8 | Seita.2G089600 | 47.3 | 86.95 | −0.069 | 213 | 23,680.2 | 6.22 |

| 9 | SiLOR9 | Seita.2G089800 | 43.43 | 94.54 | 0.267 | 194 | 21,281.88 | 10.17 |

| 10 | SiLOR10 | Seita.2G089900 | 47.38 | 83.23 | 0.204 | 164 | 17,800.54 | 8.33 |

| 11 | SiLOR11 | Seita.2G090000 | 41.4 | 99.9 | 0.282 | 202 | 22,083.56 | 8.43 |

| 12 | SiLOR12 | Seita.2G090100 | 36.69 | 89.09 | 0.108 | 209 | 22,950.37 | 7.74 |

| 13 | SiLOR13 | Seita.2G425400 | 38.16 | 79.19 | −0.11 | 210 | 22,823.3 | 9.28 |

| 14 | SiLOR14 | Seita.2G427600 | 38.16 | 78.71 | −0.145 | 210 | 22,890.33 | 9.48 |

| 15 | SiLOR15 | Seita.3G184100 | 37.58 | 81.05 | −0.2 | 237 | 25,087.06 | 5.19 |

| 16 | SiLOR16 | Seita.3G201100 | 49.32 | 85.63 | −0.04 | 213 | 22,931.42 | 9.51 |

| 17 | SiLOR17 | Seita.3G282800 | 49.19 | 79.47 | 0.057 | 189 | 20,516.86 | 9.94 |

| 18 | SiLOR18 | Seita.3G291000 | 57.75 | 81.93 | −0.035 | 223 | 23,459.71 | 8.87 |

| 19 | SiLOR19 | Seita.3G394500 | 60.47 | 72.67 | −0.388 | 341 | 38,039.42 | 5.09 |

| 20 | SiLOR20 | Seita.5G333600 | 43.38 | 86.22 | −0.056 | 222 | 23,363.68 | 8.86 |

| 21 | SiLOR21 | Seita.5G359800 | 56.84 | 80.1 | −0.149 | 196 | 21,317.38 | 8.84 |

| 22 | SiLOR22 | Seita.5G440700 | 36.1 | 74.36 | −0.127 | 202 | 21,618.7 | 9.24 |

| 23 | SiLOR23 | Seita.5G440800 | 42.64 | 70.3 | −0.1 | 201 | 21,662.85 | 9.14 |

| 24 | SiLOR24 | Seita.5G440900 | 31.49 | 86.6 | −0.159 | 209 | 23,167.81 | 8.96 |

| 25 | SiLOR25 | Seita.5G441000 | 39.19 | 80.55 | −0.026 | 201 | 21,535.82 | 9.8 |

| 26 | SiLOR26 | Seita.5G441100 | 24.5 | 90.53 | −0.091 | 227 | 24,951.01 | 9.14 |

| 27 | SiLOR27 | Seita.7G112900 | 42.77 | 88.54 | −0.025 | 199 | 21,860.38 | 7.59 |

| 28 | SiLOR28 | Seita.7G304500 | 54.39 | 82.19 | −0.234 | 228 | 24,812.31 | 9.61 |

| 29 | SiLOR29 | Seita.7G304600 | 45.94 | 88.72 | −0.042 | 219 | 23,489.05 | 9.95 |

| 30 | SiLOR30 | Seita.7G304800 | 58 | 67.71 | −0.409 | 245 | 26,561.12 | 9.69 |

| 31 | SiLOR31 | Seita.7G305000 | 56.02 | 71.07 | −0.411 | 243 | 27,151.82 | 8.88 |

| 32 | SiLOR32 | Seita.7G305100 | 68.17 | 72.44 | −0.195 | 123 | 13,194.96 | 9.5 |

| 33 | SiLOR33 | Seita.8G009600 | 53.96 | 63.18 | −0.383 | 258 | 28,573.45 | 8.82 |

| 34 | SiLOR34 | Seita.8G009700 | 50.81 | 72.94 | −0.416 | 238 | 26,809.4 | 8.77 |

| 35 | SiLOR35 | Seita.8G009800 | 54.76 | 67.16 | −0.326 | 285 | 30,657.78 | 9.34 |

| 36 | SiLOR36 | Seita.8G010600 | 49.73 | 89.81 | −0.092 | 215 | 23,192.6 | 10.01 |

| 37 | SiLOR37 | Seita.8G010700 | 55.67 | 80.96 | −0.26 | 292 | 31,418.86 | 9.67 |

| 38 | SiLOR38 | Seita.9G037500 | 41.04 | 105.15 | 0.366 | 204 | 21,932.29 | 6.11 |

| 39 | SiLOR39 | Seita.9G037600 | 51.16 | 88.85 | 0.121 | 208 | 22,214.48 | 9.26 |

| 40 | SiLOR40 | Seita.9G407600 | 36.23 | 86.19 | 0.046 | 239 | 25,497.33 | 9.32 |

| 41 | SiLOR41 | Seita.9G502700 | 21.13 | 87.66 | −0.244 | 141 | 15,544.73 | 8.48 |

| 42 | SiLOR42 | Seita.9G519000 | 41.7 | 87.06 | −0.034 | 262 | 28,044.09 | 8.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, G.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Zheng, S.; Yang, N. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the SiLOR Gene Family in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122787

Wu G, Wei X, Zhang X, Li R, Zhang R, Wang J, Wu W, Zheng S, Yang N. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the SiLOR Gene Family in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122787

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Guofan, Xin Wei, Xueting Zhang, Ruini Li, Rui Zhang, Jiayu Wang, Wangze Wu, Sheng Zheng, and Ning Yang. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the SiLOR Gene Family in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica)" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122787

APA StyleWu, G., Wei, X., Zhang, X., Li, R., Zhang, R., Wang, J., Wu, W., Zheng, S., & Yang, N. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the SiLOR Gene Family in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Agronomy, 15(12), 2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122787