New Proposal to Increase Soybean Seed Vigor: Collection Based on Pod Position

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

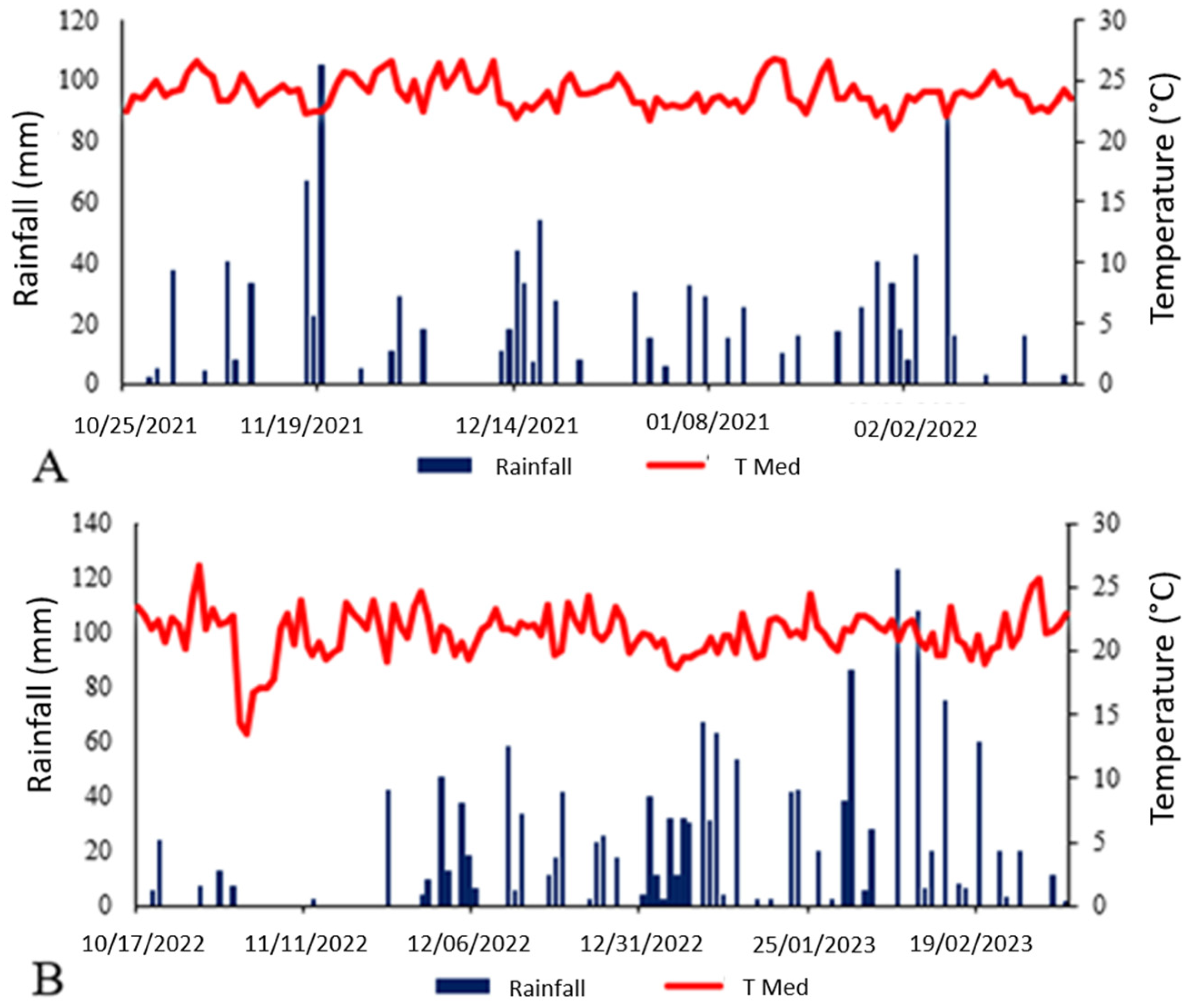

2.1. Field Experiments

2.2. Pod Tagging on Soybean Plants

2.3. Harvest and Seed Separation

2.4. Seed Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

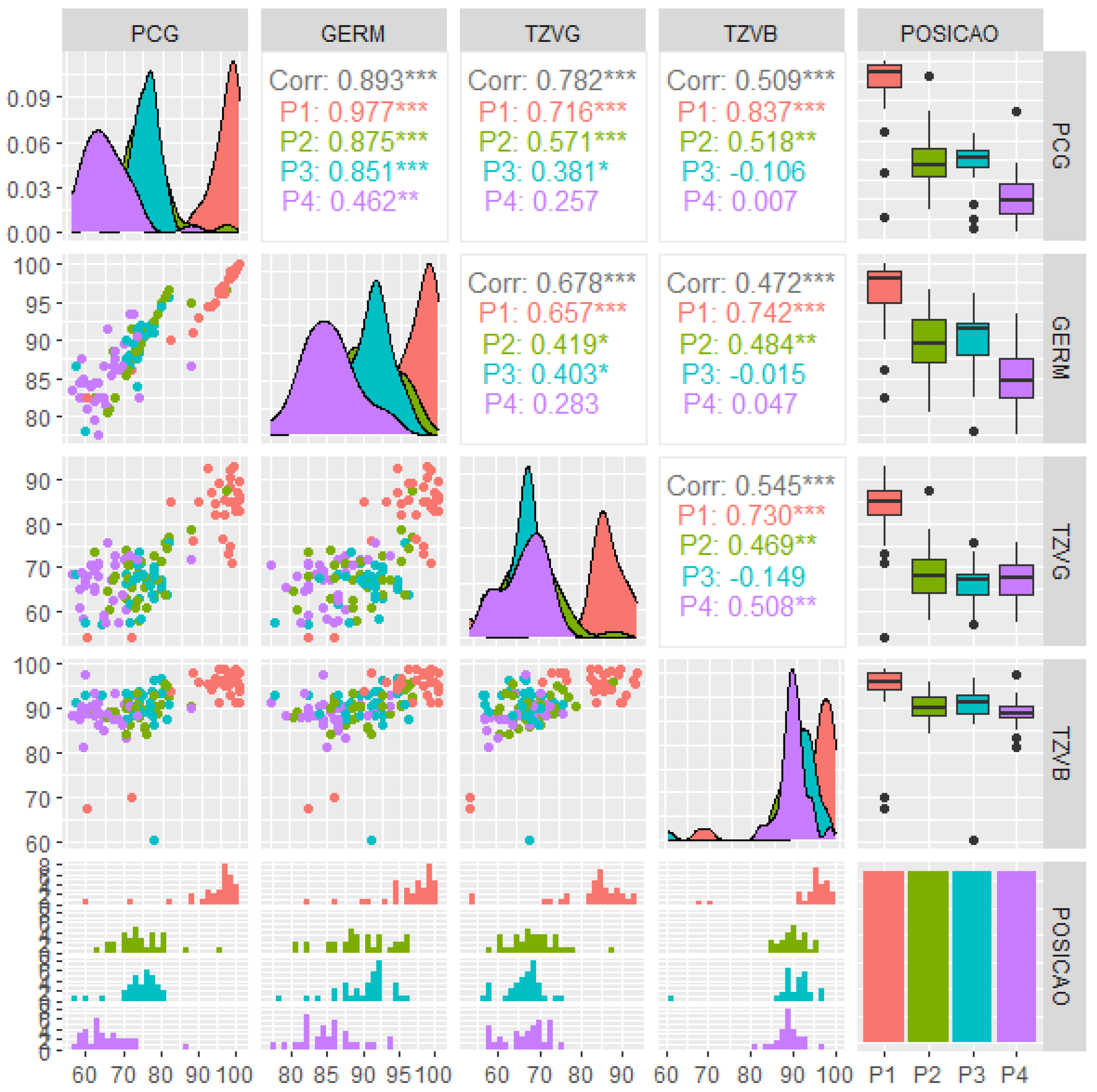

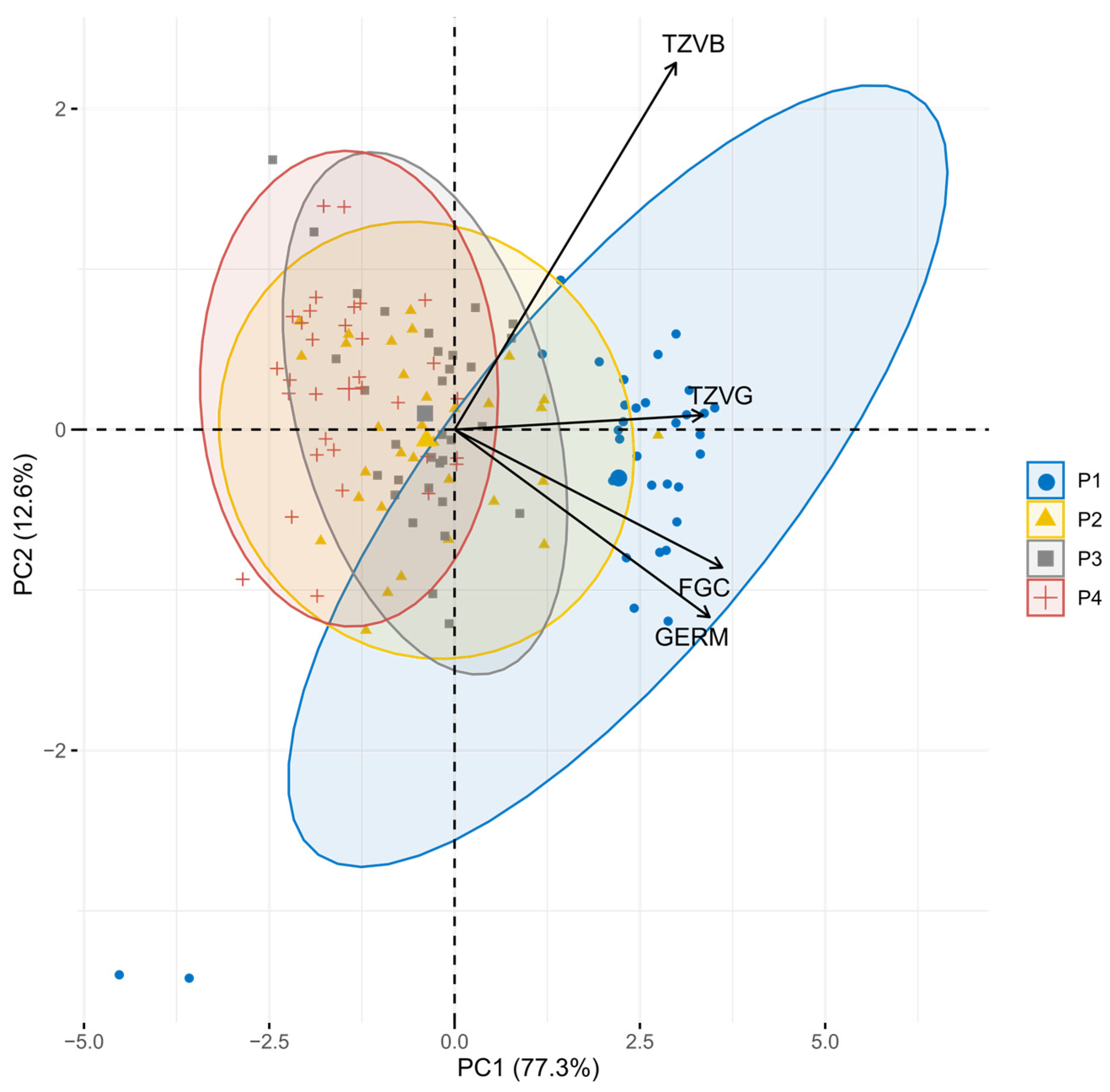

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wijewardana, C.; Reddy, K.R.; Bellaloui, N. Soybean Seed Physiology, Quality, and Chemical Composition under Soil Moisture Stress. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz-Henning, L.M.; Ferreira, L.C.; Henning, F.A.; Mandarino, J.M.G.; Santos, E.D.; Oliveira, M.C.N.D.; Nepomuceno, A.L.; Farias, J.R.B.; Neumaier, N. Effect of Water Deficit-Induced at Vegetative and Reproductive Stages on Protein and Oil Content in Soybean Grains. Agronomy 2018, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.T.; Liu, W.; Olhoft, P.; Crafts-Brandner, S.J.; Pennycooke, J.C.; Christiansen, N. Soybean Yield Formation Physiology–a Foundation for Precision Breeding Based Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 719706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumanthappa, D.; Raju, T.J. Chapter-3 Prognosis of Seed Maturity and Its Impact on Seed Quality. Adv. Hortic. 2023, 29, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Soba, D.; Arrese-Igor, C.; Aranjuelo, I. Additive Effects of Heatwave and Water Stresses on Soybean Seed Yield Is Caused by Impaired Carbon Assimilation at Pod Formation but Not at Flowering. Plant Sci. 2022, 321, 111320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumrani, K.; Bhatia, V.S. Impact of Combined Stress of High Temperature and Water Deficit on Growth and Seed Yield of Soybean. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos Filho, J. Fisiologia de Sementes de Plantas Cultivadas; Abrates: Londrina, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, D.; Hou, H.; Meng, A.; Meng, J.; Xie, L.; Zhang, C. Rapid Evaluation of Seed Vigor by the Absolute Content of Protein in Seed within the Same Crop. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Long, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tian, X.; Fan, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, W. Physiological Alterations and Nondestructive Test Methods of Crop Seed Vigor: A Comprehensive Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lu, L.; Yang, N.; Fisk, I.D.; Wei, W.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, Q.; Zeng, R. Integration of Hyperspectral Imaging, Non-Targeted Metabolomics and Machine Learning for Vigour Prediction of Naturally and Accelerated Aged Sweetcorn Seeds. Food Control 2023, 153, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.A. Seed vigor and its assessment. In Handbook of Seed Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 603–648. [Google Scholar]

- Ebone, L.A.; Caverzan, A.; Tagliari, A.; Chiomento, J.L.T.; Silveira, D.C.; Chavarria, G. Soybean Seed Vigor: Uniformity and Growth as Key Factors to Improve Yield. Agronomy 2020, 10, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masino, A.; Rugeroni, P.; Borrás, L.; Rotundo, J.L. Spatial and Temporal Plant-to-Plant Variability Effects on Soybean Yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 98, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altizani-Júnior, J.C.; Cicero, S.M.; de Lima, C.B.; Alves, R.M.; Gomes-Junior, F.G. Optimizing Basil Seed Vigor Evaluations: An Automatic Approach Using Computer Vision-Based Technique. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zou, J.; Ning, Z.; Tan, X.; Yang, F.; Yang, W. Functional Consequences of Light Intensity on Soybean Leaf Hydraulic Conductance: Coordinated Variations in Leaf Venation Architecture and Mesophyll Structure. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 210, 105301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Tan, T.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) Seedlings Response to Shading: Leaf Structure, Photosynthesis and Proteomic Analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, S.; Erbaş, S.; Önder, D.; Tonguç, M.; Mutlucan, M. Seed filling. In Seed Biology Updates; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 1803558148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. Contribution of the Leaf and Silique Photosynthesis to the Seeds Yield and Quality of Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.) in Reproductive Stage. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Chagas, P.H.M.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Santana, D.C.; Filho, M.C.M.T.; Coradi, P.C.; Torres, F.E.; Bhering, L.L.; Teodoro, P.E. Understanding the Combining Ability of Nutritional, Agronomic and Industrial Traits in Soybean F2 Progenies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, A., Jr.; de Castro, C.; Pereira, L.R.; da Domingos, C.S. Estádios Fenológicos e Marcha de Absorção de Nutrientes Da Soja. 2016. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1047123 (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária E Abastecimento. Regras Para Análise de Sementes; Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária E Abastecimento: Brasilia, Brazil, 2009.

- Krzyzanowski, F.C.; de França-Neto, J.B.; Henning, A.A. A Alta Qualidade Da Semente de Soja: Fator Importante Para a Produção da Cultura; Circular Técnica: Londina, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J.; Knott, M. A Cluster Analysis Method for Grouping Means in the Analysis of Variance. Biometrics 1974, 30, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. 2016, 1, 409. [Google Scholar]

- Sripathy, K.V.; Groot, S.P.C. Seed development and maturation. In Seed Science and Technology: Biology, Production, Quality; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ostmeyer, T.; Parker, N.; Jaenisch, B.; Alkotami, L.; Bustamante, C.; Jagadish, S.V.K. Impacts of Heat, Drought, and Their Interaction with Nutrients on Physiology, Grain Yield, and Quality in Field Crops. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2020, 25, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, L.-N.; Jiang, C.-D.; Liu, Y.-J.; Shi, L. Effects of Mutual Shading on the Regulation of Photosynthesis in Field-Grown Sorghum. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 137, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Mittler, R.; Balfagón, D.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Plant Adaptations to the Combination of Drought and High Temperatures. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 162, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, J.S.; Quijano, A.; Gosparini, C.O.; Morandi, E.N. Changes in Leaflet Shape and Seeds per Pod Modify Crop Growth Parameters, Canopy Light Environment, and Yield Components in Soybean. Crop J. 2020, 8, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, J.A.; Lange, B.M. Metabolic Cross Talk between Cytosolic and Plastidial Pathways of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis: Unidirectional Transport of Intermediates across the Chloroplast Envelope Membrane. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 415, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoufa, A.; Hossain, Z. Regulation of Carotenoid Accumulation in Plants. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2012, 1, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, D.A.; Braga Silveira, B.; Cavenaghi Prete, C.E.; Bahry, C.A.; Nardino, M. Agronomic Performance of Soybean with Indeterminate Growth Habit in Different Plant Arrangements. Commun. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandar, C.C.; Pal, D. Relation between seed life cycle and cell proliferation. Metabolic changes in seed germination. In Seeds: Anti-Proliferative Storehouse for Bioactive Secondary Metabolites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, F.; Balbinot Junior, A.A.; Ferreira, A.S.; de Silva, M.A.E.A.; Debiasi, H.; Franchini, J.C. Soybean Growth Affected by Seeding Rate and Mineral Nitrogen. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agric. Ambient. 2016, 20, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagno, S.; Sadras, V.O.; Aznar-Moreno, J.A.; Durrett, T.P.; Ciampitti, I.A. Selection for Yield Shifted the Proportion of Oil and Protein in Favor of Low-Energy Seed Fractions in Soybean. Field Crops Res. 2022, 279, 108446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, D.C.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Baio, F.H.R.; dos Santos, R.G.; Coradi, P.C.; Biduski, B.; da Silva, C.A., Jr.; Teodoro, P.E.; Shiratsuchi, L.S. Classification of Soybean Genotypes for Industrial Traits Using UAV Multispectral Imagery and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. Appl. 2023, 29, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.D.; Black, M. Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 1489910026. [Google Scholar]

- Poeta, F.B.; Rotundo, J.L.; Borrás, L.; Westgate, M.E. Seed Water Concentration and Accumulation of Protein and Oil in Soybean Seeds. Crop Sci. 2014, 54, 2752–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinta, R.T.; Quebedeaux, B.; Sadler, N.L.; Franceschi, V.R. Assimilate partitioning in soybean leaves during seed filling. In Proceedings of the World Soybean Research Conference III; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, R.A.; Ort, D.R. Perspectives on Improving Light Distribution and Light Use Efficiency in Crop Canopies. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, S.C.; Lal, M.A. Secondary metabolites. In Plant Physiology, Development and Metabolism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 765–808. [Google Scholar]

| Position | Reproductive Stage (R) | Description | Representative Figure |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | R4 | Fully developed pods, 2 cm in length, located at one of the four uppermost nodes of the stem. |  |

| P2 | R5 | Pods at grain-filling stages, perceptible to touch and exhibiting varying degrees of grain development. | |

| P3 | R6 | Pods at grain-filling stages, perceptible to touch and exhibiting varying degrees of grain development. | |

| P4 | R7 | Beginning of physiological maturity of the seeds, with at least one mature pod present on the main stem. |

| SV | DF | FGC | GERM | TZVG | TZVB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Season (S) | 1 | 154,907.24 * | 6033.97 * | 44,249.45 * | 4289.10 * |

| Position (P) | 3 | 37,454.86 * | 5350.66 * | 15,385.28 * | 1320.64 * |

| Genotypes (G) | 31 | 532.09 * | 171.59 * | 452.09 * | 161.81 * |

| P × G | 93 | 316.98 * | 116.58 * | 329.64 * | 141.15 * |

| P × S | 3 | 20,701.37 * | 1797.50 * | 5928.25 * | 1021.24 * |

| G × S | 31 | 137.84 * | 66.55 * | 256.22 * | 50.74 * |

| P × S × G | 92 | 149.27 * | 58.89 * | 175.35 * | 56.42 * |

| Residual | 769 | 27.67 | 29.21 | 47.69 | 34.24 |

| CV (%) | - | 6.82 | 5.97 | 9.74 | 6.42 |

| Genotype | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 98.5 aB | 79.5 bB | 76.0 bA | 59.5 cB |

| G2 | 97.5 aA | 76.0 bCc | 77.5 bA | 70.5 bA |

| G3 | 100.0 aA | 71.5 bC | 77.5 bA | 64.5 bB |

| G4 | 99.5 aA | 96.5 aA | 76.5 bA | 67.5 bA |

| G5 | 98.0 aA | 87.5 bA | 77.0 cA | 66.5 cA |

| G6 | 94.5 aA | 80.5 bB | 74.0 bA | 87.5 aA |

| G7 | 100.0 aA | 81.5 bB | 77.5 bA | 71.5 bA |

| G8 | 99.0 aA | 77.5 bB | 74.0 bA | 72.5 bA |

| G9 | 96.0 aA | 75.5 bC | 79.5 bA | 70.0 bA |

| G10 | 97.5 aA | 75.5 bC | 79.5 bA | 63.5 cB |

| G11 | 100.0 aA | 73.5 bC | 79.5 bA | 63.5 cB |

| G12 | 99.0 aA | 72.0 bC | 77.5 bA | 60.0 cB |

| G13 | 100.0 aA | 67.0 cC | 76.5 bA | 60.5 cB |

| G14 | 99.0 aA | 62.5 cC | 75.0 bA | 56.5 cB |

| G15 | 97.5 aA | 66.0 bC | 57.5 bB | 58.5 bB |

| G16 | 99.5 aA | 71.0 bC | 74.5 bB | 61.5 cB |

| G17 | 91.5 aA | 74.0 bC | 64.0 bB | 63.5 bB |

| G18 | 72.0 aB | 72.5 aC | 60.0 bB | 62.5 bB |

| G19 | 97.0 aA | 70.5 bC | 71.5 bA | 60.0 cB |

| G20 | 96.0 aA | 67.5 cC | 81.0 bA | 64.5 cB |

| G21 | 94.5 aA | 73.5 bC | 70.5 bA | 65.0 bB |

| G22 | 97.5 aA | 74.5 bC | 70.5 bA | 63.5 cB |

| G23 | 93.5 aA | 70.5 bC | 73.5 bA | 59.0 cB |

| G24 | 95.5 aA | 65.5 bC | 62.5 bB | 58.5 bB |

| G25 | 98.0 aA | 77.5 bB | 74.5 bA | 67.5 bA |

| G26 | 88.0 aA | 78.5 aB | 71.5 bA | 67.0 bA |

| G27 | 92.5 aA | 71.0 bC | 73.5 bA | 71.5 bA |

| G28 | 60.5 bC | 73.0 aC | 81.5 aA | 68.5 bA |

| G29 | 97.0 aA | 77.5 bB | 77.5 bA | 62.5 cB |

| G30 | 89.0 aA | 80.5 aB | 72.5 bA | 69.5 bA |

| G31 | 82.0 aB | 81.0 aB | 76.5 bA | 65.5 bB |

| G32 | 93.5 aA | 73.5 bC | 77.0 bA | 73.5 bA |

| Genotype | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 98.5 aA | 95.0 aA | 91.5 bA | 85.0 bB |

| G2 | 98.0 aA | 91.0 bA | 92.5 bA | 87.5 bA |

| G3 | 100.0 aA | 87.5 bB | 92.5 bA | 86.5 bA |

| G4 | 99.5 aA | 96.5 aA | 92.0 bA | 87.5 bA |

| G5 | 98.5 aA | 95.0 aA | 92.0 aA | 85.5 bB |

| G6 | 96.0 aA | 95.5 aA | 88.5 bA | 86.5 bA |

| G7 | 100.0 aA | 96.5 aA | 92.5 aA | 82.5 bB |

| G8 | 99.5 aA | 92.5 bA | 91.5 bA | 93.5 bA |

| G9 | 97.0 aA | 90.5 bA | 94.5 aA | 89.5 bA |

| G10 | 98.0 aA | 90.5 aA | 94.5 aA | 77.5 bB |

| G11 | 100.0 aA | 89.5 bB | 94.5 aA | 84.5 bB |

| G12 | 99.0 aA | 91.5 bA | 92.0 bA | 84.5 cB |

| G13 | 100.0 aA | 88.5 bB | 91.5 bA | 81.0 cB |

| G14 | 99.0 aA | 82.5 cC | 90.5 bA | 83.5 cB |

| G15 | 99.0 aA | 81.0 bC | 86.5 bB | 84.5 bB |

| G16 | 99.5 aA | 86.0 bB | 89.5 bA | 84.0 bB |

| G17 | 94.5 aA | 89.0 aB | 82.5 bC | 82.0 bB |

| G18 | 86.0 aB | 87.5 aB | 78.0 bC | 84.5 aB |

| G19 | 98.0 aA | 85.5 bB | 86.5 bB | 82.5 bB |

| G20 | 96.0 aA | 82.5 bC | 96.0 aA | 82.5 bB |

| G21 | 96.5 aA | 88.5 bB | 90.0 bA | 81.5 cB |

| G22 | 98.5 aA | 89.5 bB | 87.5 bB | 82.5 cB |

| G23 | 95.0 aA | 85.5 bB | 91.5 aA | 87.5 bA |

| G24 | 97.0 aA | 80.5 bC | 84.2 bB | 82.5 bB |

| G25 | 99.0 aA | 92.5 bA | 92.0 bA | 88.5 bA |

| G26 | 91.0 aA | 93.5 aA | 88.0 aB | 86.5 aA |

| G27 | 94.5 aA | 86.0 bB | 87.5 bB | 93.5 aA |

| G28 | 83.5 bB | 88.5 bB | 95.5 aA | 86.0 bA |

| G29 | 98.0 aA | 92.5 bA | 91.0 bA | 79.5 cB |

| G30 | 93.0 aA | 95.5 aA | 89.5 bA | 86.5 bA |

| G31 | 90.0 aA | 96.0 aA | 91.0 aA | 91.5 aA |

| G32 | 95.0 aA | 88.5 aB | 91.5 aA | 90.5 aA |

| Genotype | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 93.0 aA | 71.5 bA | 67.0 bA | 58.5 cB |

| G2 | 88.5 aA | 61.0 bB | 69.5 bA | 60.5 bB |

| G3 | 85.5 aA | 70.5 bA | 70.0 bA | 58.0 cB |

| G4 | 85.0 aA | 87.5 aA | 67.4 bA | 72.5 bB |

| G5 | 85.0 aA | 78.5 aA | 68.0 bA | 67.0 bB |

| G6 | 89.0 aA | 75.5 bA | 73.5 bA | 72.0 bA |

| G7 | 83.0 aA | 77.0 aA | 63.0 bB | 70.5 bA |

| G8 | 83.0 aA | 72.5 bA | 63.0 bB | 67.0 bA |

| G9 | 82.0 aA | 68.0 bB | 67.0 bA | 72.0 bA |

| G10 | 75.0 aB | 65.5 aB | 65.0 aA | 70.5 aA |

| G11 | 86.0 aA | 68.5 bB | 66.5 bA | 68.0 bA |

| G12 | 83.5 aA | 65.5 bB | 68.0 bA | 67.0 bA |

| G13 | 89.5 aA | 67.0 bB | 66.0 bA | 68.0 bA |

| G14 | 84.0 aA | 73.5 bA | 68.5 bA | 68.5 bA |

| G15 | 92.0 aA | 60.5 bB | 68.5 bA | 61.0 bB |

| G16 | 87.0 aA | 70.5 bA | 71.0 bA | 70.5 bA |

| G17 | 92.5 aA | 58.0 bB | 57.0 bB | 64.5 bB |

| G18 | 54.0 cC | 71.0 aA | 57.5 bB | 69.5 aA |

| G19 | 73.0 aB | 63.0 aB | 61.5 aB | 66.0 aA |

| G20 | 85.5 aA | 68.0 bB | 64.0 bB | 59.0 bB |

| G21 | 89.0 aA | 70.5 bA | 66.5 bA | 57.5 cB |

| G22 | 90.5 aA | 71.5 bA | 68.5 bA | 71.0 bA |

| G23 | 82.0 aA | 74.0 bA | 70.5 bA | 69.0 bA |

| G24 | 76.5 aB | 64.5 bB | 67.5 bA | 65.0 bA |

| G25 | 71.0 aA | 64.0 bB | 58.5 bB | 70.5 aA |

| G26 | 76.0 aB | 67.0 bB | 57.5 bB | 62.5 bB |

| G27 | 87.0 aA | 67.5 bB | 68.0 bA | 72.0 bA |

| G28 | 54.0 bC | 61.0 bB | 75.5 aA | 57.5 bB |

| G29 | 85.0 aA | 67.0 bB | 68.0 bA | 65.5 bA |

| G30 | 85.0 aA | 64.0 bB | 67.0 bA | 64.0 bB |

| G31 | 85.0 aA | 74.5 bA | 66.0 bA | 75.5 bA |

| G32 | 84.5 aA | 62.5 bB | 64.0 bB | 72.0 bA |

| Genotype | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 98.0 aA | 91.0 bB | 89.5 bA | 81.5 cA |

| G2 | 97.5 aA | 84.5 bB | 88.5 bA | 83.5 bA |

| G3 | 95.0 aA | 86.5 bB | 86.5 bA | 85.0 bA |

| G4 | 96.0 aA | 96.0 aA | 91.5 aA | 89.5 aA |

| G5 | 97.5 aA | 90.5 aB | 94.0 aA | 89.5 aA |

| G6 | 99.0 aA | 94.5 bA | 91.5 bA | 90.0 bA |

| G7 | 94.0 aA | 92.5 aA | 96.5 aA | 88.5 aA |

| G8 | 96.0 aA | 93.0 aA | 94.0 aA | 93.0 aA |

| G9 | 99.0 aA | 86.0 bB | 96.5 aA | 92.0 bA |

| G10 | 98.0 aA | 85.5 bB | 93.5 aA | 91.5 aA |

| G11 | 98.0 aA | 90.5 bB | 97.0 aA | 86.5 bA |

| G12 | 91.5 aA | 90.0 aB | 89.5 aA | 87.5 aA |

| G13 | 91.5 aA | 87.5 aB | 91.5 aA | 89.0 aA |

| G14 | 99.0 aA | 89.0 bB | 93.0 bA | 88.5 bA |

| G15 | 96.5 aA | 89.5 bB | 91.5 bA | 87.5 bA |

| G16 | 98.5 aA | 92.5 bA | 93.0 bA | 90.5 bA |

| G17 | 95.5 aA | 88.0 aB | 93.0 aA | 93.5 aA |

| G18 | 70.0 bB | 88.5 aB | 93.0 aA | 91.0 aA |

| G19 | 98.0 aA | 84.5 bB | 93.0 aA | 90.0 bA |

| G20 | 95.0 aA | 89.5 aB | 87.5 aA | 88.0 aA |

| G21 | 91.5 aA | 91.0 aB | 93.5 aA | 88.0 aA |

| G22 | 93.0 aA | 90.0 aB | 87.5 aA | 89.5 aA |

| G23 | 97.0 aA | 90.0 bB | 90.0 bA | 90.5 bA |

| G24 | 96.5 aA | 88.0 bB | 89.0 bA | 89.0 bA |

| G25 | 96.0 aA | 93.0 aA | 89.5 aA | 93.5 aA |

| G26 | 98.0 aA | 89.0 bB | 91.0 bA | 87.5 bA |

| G27 | 94.5 aA | 91.5 aA | 89.0 aA | 90.5 aA |

| G28 | 67.5 bB | 90.0 aB | 91.0 aA | 87.5 aA |

| G29 | 95.0 aA | 90.5 aB | 90.5 aA | 88.5 aA |

| G30 | 96.0 aA | 96.5 aA | 88.5 bA | 86.5 bA |

| G31 | 94.0 aA | 95.0 aA | 90.5 aA | 89.0 aA |

| G32 | 95.5 aA | 93.5 aA | 88.5 bA | 88.5 bA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, I.C.d.; Santana, D.C.; Seron, A.C.d.S.C.; Alves, C.Z.; Vaez, R.N.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Teodoro, P.E. New Proposal to Increase Soybean Seed Vigor: Collection Based on Pod Position. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112563

Oliveira ICd, Santana DC, Seron ACdSC, Alves CZ, Vaez RN, Teodoro LPR, Teodoro PE. New Proposal to Increase Soybean Seed Vigor: Collection Based on Pod Position. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112563

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Izabela Cristina de, Dthenifer Cordeiro Santana, Ana Carina da Silva Cândido Seron, Charline Zaratin Alves, Renato Nunez Vaez, Larissa Pereira Ribeiro Teodoro, and Paulo Eduardo Teodoro. 2025. "New Proposal to Increase Soybean Seed Vigor: Collection Based on Pod Position" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112563

APA StyleOliveira, I. C. d., Santana, D. C., Seron, A. C. d. S. C., Alves, C. Z., Vaez, R. N., Teodoro, L. P. R., & Teodoro, P. E. (2025). New Proposal to Increase Soybean Seed Vigor: Collection Based on Pod Position. Agronomy, 15(11), 2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112563