Abstract

To clarify the interactions of rainfall characteristics and sugarcane growth stages on the characteristics of soil erosion and nutrient loss in intensive sugarcane-cultivated lands. Based on the in situ observation experiment, we investigated runoff, sediment yield, and nutrient loss under a total of 97 natural rainfall events from 2019 to 2022. Rainfall pattern A (large R and I30, medium TR) and B (medium R, TR, and I30) were the main erosive rainfalls in the study area. Runoff and sediment induced by pattern A contributed 38.3% and 61.0% of total runoff and sediment, while pattern B contributed 37.1% and 31.4%, respectively. The sediment yield and nutrient loss (particularly PP) was mainly concentrated in sugarcane seeding stage (SS), dissolved nutrient loss in the tillering stage (TS), particularly NO3−–N, which accounted for 49.6% of the total dissolved nitrogen loss, and the highest runoff occurred at the elongation stage (ES). In addition, the reduction in sugarcane growth on soil erosion and nutrient loss in pattern A were the most obvious. The positive influences of rainfall characteristics on runoff depth and soil loss were higher than the negative effects of sugarcane coverage. Rainfall amount accounts for 26.1%~61.8% (p < 0.01) of the variation in soil erosion parameters (RD, SL, RNO3−–N, and PP loss). The RDA showed that EI30 (explaining 45.9% of variation), E (explaining 41.2% of variation), and R (explaining 27.9% of variation) were the primary drivers of soil erosion and nutrient loss in the ES, TS, and SS. The combination of a high amount of and intensity rainfall, low sugarcane canopy coverage, and irrational application such as applying fertilizers after rainfall, were the main cause of soil erosion and nutrient loss in sugarcane fields. Thus, increasing sugarcane ground coverage and increasing the fertilization time are strongly recommended for reducing soil and nutrient loss. This may be an important practice to protect the agricultural ecological environment of sugarcane fields and improve their economic benefits.

1. Introduction

Soil erosion and nutrient loss from sloping farmlands, which has a serious impact on water quality, threatens food security and ecosystem viability, and thus causes considerable damage to human society and ecosystems [1,2]. Runoff and sediment from farmland are considered the main sources of soil nutrients entering water bodies. Nutrients are usually lost in two ways—sediment-associated nutrients lost as particles and dissolved nutrients lost with runoff. The loss of nitrogen and phosphorus in sloping croplands are the key factors that reduce soil fertility and influence crop growth [3,4,5]. Therefore, investigation of soil erosion and nutrient loss from farmland is important for better management of agricultural production and the ecological environment.

Soil erosion and nutrient loss induced by rainfall is an extremely dynamic and complicated process, and studies on soil erosion and nitrogen and phosphorus losses have identified contributing factors such as rainfall amount, rainfall intensity, rainfall duration, and rainfall erosivity [6,7,8,9,10]. Generally, runoff is significantly and positively related to rainfall [11], and nutrient concentration is directly affected by the runoff volume and eroded soil amount [12]. Generally, for rainfall-induced erosion, the dominant sediment transport mechanism depends on both raindrop detachment and the resultant overland runoff [13]. The variability in precipitation and the complexity of natural geographical conditions determine the complexity of the runoff and sediment formation process [14]. Increasing rainfall intensity not only enhances the detachment of raindrops on soil particles, but also significantly influences the variations in flow spatial distribution and its mechanisms in the erosion process [15,16,17]. However, in natural rainstorms, rainfall intensity is highly variable overtime and influences the formation of saturation overland flow, the initiation of sediment and transport, raindrop impact crust, and so on [18]. Dividing rainfall events into different rainfall patterns based on comprehensive rainfall characteristics will enhance our understanding of soil detachment and sediment transport processes [19]. Rainfall with a higher intensity and/or longer duration usually generates a higher runoff peak, especially when the rainfall is highly temporally variable [17]. By influencing raindrop detachment and enhancing flow transport, the results of Alavinia et al., (2018) [13] found that a varying-intensity rainfall pattern implied that the rainfall pattern controlled the sediment transport mechanism. Wang et al., (2023) [20] showed that the falling pattern and falling–rising pattern had a shorter time gap between rainfall initiation and runoff occurrence as well as a larger sediment yield than those of the other rainfall patterns. Rainfall with a high intensity and short duration mainly causes the greatest proportion of runoff and soil loss [13] and also drives the redistribution nutrients due to larger runoff volumes and sediment yield [21,22,23,24]. Jia et al., (2007) [25] indicated that the dynamics of runoff NO3−–N loss are highly complex and affected by variable natural rainfall events. The runoff NO3−–N concentration was significantly higher in the moderate and heavy rains than in the light rain and large rainstorms [26,27]. However, previous studies have focused on the relationships between soil erosion, nutrient loss, and rainfall characteristics. Runoff and sediment generation in different areas may vary greatly with various rainfall patterns, so ensuring adequate responses to runoff and soil loss to different rainfall patterns is therefore important for cultivated land.

The interaction of soil erosion and nutrient loss with rainfall is a complex and dynamic process, which is also influenced by multiple factors, such as crops [28,29]. The impact of crops on soil loss and water erosion has been widely studied. In general, the interception of rainfall by above-ground plant parts effectively reduces nutrient loss via runoff and sediment transport [30,31,32]. Lower coverage produces higher sediment, and consequently, higher nutrient loss. Udawatta et al., (2006) [33] reported 57% of TN exports from the watershed without crop cover. Liu et al, (2024) [23] demonstrates that, among 12 runoff plots in the red soil region of southern China, runoff and sediment in the peanut seedling stage accounted for 71.5% of the whole growth period. Other studies have reported reductions in N and P losses following an increase in coverage [34,35]. Overall, studies have shown that different growth stages of crops reflect different runoff regulation functions [36,37,38]. Many studies have shown that runoff and sediment produced under the same vegetation type can vary greatly depending on different rainfall patterns [39,40], such as N and P loss with runoff and soil. However, the interaction of rainfall pattern, runoff-related and sediment-associated (particulate) nutrient loss during different crop growth stages remains unclear, and further quantitative analysis is needed. Sugarcane is a perennial crop that grows for a long time, and its vegetation coverage varies significantly during the growth period. In addition, sugarcane is the main crop planted in the red soil region, and 70% of the sugarcane is planted on hilly slopes, according to Chen et al., (2024) [41,42]. Moreover, Moreover, the growth stages of sugarcane coincide with the regional rainfall erosivity period, and fertilizer application may exacerbate nutrient loss [43]. A lot of research has been conducted on soil erosion and nutrient loss in sugarcane cultivation. Yang et al., (2023) [43] used runoff plot monitoring to analyze the effects of different rainfall patterns on runoff and sediment output in sugarcane fields. Li et al., (2022) [27] applied dual stable isotope tracing techniques to assess the contribution of fertilization to nitrate nitrogen pollution in rivers within sugarcane planting areas. Based on field experiments, Wang et al., (2021) [14] found that maintaining a replanting ratio of around 30% can effectively mitigate soil erosion and nutrient loss in sugarcane fields. However, the response mechanisms of soil erosion and nutrient loss on sugarcane slopes to rainfall characteristics during different growth periods still requires further investigation. Additionally, long-term natural rainfall conditions is of great practical significance for scientifically preventing and controlling soil erosion and nutrient loss on different sugarcane-growing slopes.

Therefore, this study collected runoff and sediment samples from field plots with different rainfall patterns across the sugarcane growth stage. The response of N and P loss in runoff and sediment to rainfall characteristics and sugarcane coverage were investigated, based on in situ monitoring data over a four-year period (2019 to 2022). The aims of this study were as follows: (1) to describe the characteristics of runoff and sediment yield to rainfall patterns under different sugarcane growth periods, (2) to investigate the distributions of NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and P losses in runoff and sediment under each rainfall pattern, and (3) to evaluate the impacts of the contributing factors on runoff, sediment yield, and nutrient loss on sugarcane slope.

2. Materials and Methods

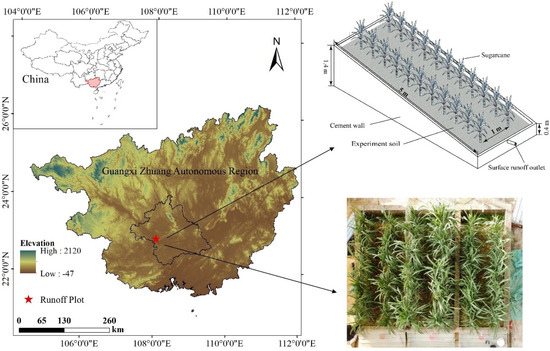

2.1. Study Area

The research area, which belongs to a subtropical monsoon climate zone, is located at the experimental base of Guangxi University in Nanning, Guangxi (108°17′38″ E, 22°50′59″ N). The average annual rainfall is approximately 1400 mm, with an average annual temperature of 22.4 °C and an average relative humidity of 79% (China Statistical Yearbook, 2023) [44]. The soil type is lateritic red soil, which has a cohesive medium loam texture and contains 43.9% sand, 37.9% silt, and 18.2% clay. The physicochemical properties of the top 0–20 cm of the soil before conducting the study were as follows: soil bulk density 1.2–1.3 g/cm3, soil pH 6.7, 6.6 g/kg organic carbon, 1.3 g/kg total nitrogen, 13.1 mg/kg ammonium nitrogen, 24.7 mg/kg nitrate nitrogen, and 0.6 g/kg total phosphorus.

2.2. Experimental Design and Monitoring

The experiment adopted an in situ observation method for runoff plots in the field (Figure 1). The experimental runoff plots were 5.0 m (length) × 2.0 m (width) and facing south. The slope gradient of the runoff plots was 10°. Cement walls were built around the runoff plots, and a water outlet was set at the lower end of the plots. The outlet was connected to a steel flow collection tank (2 m long, 0.6 m wide, and 0.4 m high), and the wall of the flow collection tank was equipped with a ruler to observe the water depth inside the flow collection tank. The plastic cover on the flow collection tank was used to prevent rainwater from seeping in.

Figure 1.

The schematic drawing of the experimental setup.

The treatment runoff plots were planted with sugarcane longitudinally. The two runoff plots were duplicated, and no control treatment was applied. The average value of the two runoff plots was taken for data processing and analysis. Sugarcane was planted in two rows at a spacing of 100 cm in each belt. The sugarcane planting and fertilization management plans are shown in Table 1 and Table S1, and other field management measures included typical local agricultural management. The observation period was from May to September in 2019 to 2022 and included the sugarcane seedling stage (SS), tillering stage (TS), and elongation stage (ES). Runoff depth, soil erosion, and nutrient loss were observed on the sugarcane-cultivation slopes.

Table 1.

Experimental treatments.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Erosive Rainfall Data

The statistical analysis of this experiment was based on 97 erosive rainfall events from 2019 to 2022. The observation indices mainly included rainfall depth (R, mm) and rainfall duration (TR, h) and were recorded by a tipping bucket self-recording rain gauge (Brand: Veinasa; Model: MAWS016; temporal resolution: 0.2 mm/min). According to the rainfall depth (R, mm) and rainfall duration (TR, h) recorded by the rain gauge, the rainfall intensity (I30, 30 min maximum rainfall intensity) and kinetic energy, etc., were obtained, and were calculated by the rain record software. Rainrecord 1.03 has been developed for various types of rainfall observation data and has been used in the field of soil and water conservation monitoring. This software is based on the VC++ language and Qt database and can analyze the characteristics of rainfall for tipping bucket rain gauges and the corresponding electronic data formats. The characteristics of erosive rainfalls in the study area from April to October 2019 to 2022 are shown in Figure S1.

2.3.2. Runoff, Sediment Yield, and Nutrient Dates

The volume of runoff and sediment yield in each collection tank were measured after each rainfall event. The water depths in the collecting troughs were measured and recorded. After thoroughly mixing at different locations, three samples of the mixture of runoff and sediment were collected by using polyethylene plastic bottles (500 mL) at different locations in the collection tank. The sediment was collected in an aluminum box, and the remainder of the sample was removed. The samples were then passed through a 0.45 μm filter membrane to separate surface runoff and sediment yield. The runoff samples were immediately stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for further analysis. The sediment yield samples were air-dried and weighed for the determination of sediment concentration and then sieved through a 1 mm sieve for nutrient determination. The runoff amount in each trough was measured by volumetric method, and the soil erosion amount was obtained via gravimetric analysis.

Nitrate nitrogen (NO3−–N) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+–N) in runoff were determined by a continuous flow chemical analyzer (model: AA3; origin: Hamburg, Germany). The nitrate nitrogen (NO3−–N) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+–N) in the sediment yield were analyzed by a continuous flow chemical analyzer (model: AA3; origin: Germany) following extraction with 0.01 mol/L of CaCl2. The dissolved phosphorus (DP) in the surface runoff (filtrate) was measured by molybdenum antimony anti-UV spectrophotometry after digestion with K2S2O8 (ultraviolet spectrophotometer, model: T6; origin: Beijing, China), and the particulate phosphorus (PP) was determined by the molybdenum antimony colorimetric method after digestion with H2SO4 and HClO4 (ultraviolet spectrophotometer; model: T6; origin: Beijing, China).

2.4. Calculation of Parameters and Statistical Analysis

In situ observation for runoff and sediment yield was used to analyze soil erosion in this study. Runoff (RD, mm) and sediment yield (SL, kg/hm2) for each rainfall event were generated by the following formulate:

where RV, S, and SM were, respectively, water sample volume for a given rainfall event (m3), the area of runoff plot (hm2), and weight of sediment (kg).

The runoff coefficient (RC) was calculated as the ratio of runoff to rainfall. The sediment coefficient (SC) was calculated as the ratio of sediment to runoff. In addition, the calculation of the total runoff, sediment, and N and P volume in the sugarcane-cultivated slopes is as follows:

where Ci and Cii are the nutrient concentration in runoff (mg/L) and in sediment (mg/kg or g/kg) for rainfall event i, respectively, TRD, TSL, TRN (TNO3−–RN and TNH4+–RN), TSN (TNO3−–SN and TNH4+–SN), TDP, and TPP are the total amount of runoff (mm), sediment yield (kg/hm2), NO3−–N and NH4+–N loss in runoff and sediment (g/hm2), dissolved phosphorus (DP) (g/hm2), and particulate phosphorus (PP) (g/hm2)) under erosive rainfall events, respectively. In this study, we used NO3−–RN and NH4+–RN to represent N loss in runoff, and NO3−–SN and NH4+–SN represent N loss in sediment.

The average unit rainfall events runoff, sediment yield, and N and P loss are calculated as follows:

where ARD, ASL, ARN (ANO3−–RN and ANH4+–RN), ASN (A NO3−–SN and ANH4+–RN), ADP, and APP are the average runoff depth (mm), sediment yield (kg/hm2), NO3−–N and NH4+–N loss in runoff and sediment (g/hm2), DP (g/hm2), and PP (g/hm2) loss of unit rainfall events, respectively.

The runoff, sediment yield, and N and P loss caused by unit rainfall are calculated as follows:

where RRD, RSL, RRN (RNO3−–RN and RNH4+–RN), RSN (R NO3−–SN and RNH4+–RN), RDP, and RPP are runoff, sediment yield, NO3−–N and NH4+–N loss in runoff and sediment, DP, and PP caused by unit rainfall (RRD is no units, the units of RSL are kg/(hm2·mm), and RRN, RSN, RDP, and RPP are g/(hm2·mm)). Ri was rainfall amount (mm).

Vegetation coverage on the slope was vertically captured using drones, which imported the captured images into a computer and processed them into grayscale images. The vegetation coverage was determined based on the grayscale data. Images of the vegetation on sugarcane planting slopes were taken every 7 days. The vegetation coverage at the SS, TS, and ES was 11.6%, 44.2%, and 79.3%, respectively.

Rainfall (R, mm), rainfall duration (TR, h), and maximum 30 min rainfall intensity (I30, mm/h) were selected as indicators [45,46] to classify erosive rainfall events in the experimental area. K-means clustering analysis and discriminant analysis were conducted on erosive rainfall data to classify different rainfall patterns by using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, SPSS, New York, NY, USA). Redundancy analysis (RDA) was used to visualize the relationships between response variables (i.e., runoff depth, sediment yield, N and P loss) and explanatory factors (i.e., rainfall parameters and sugarcane coverage) in CANOCO 5.0 software (Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, NY, USA).

Charts were drawn by using Origin 2018 and Microsoft Office 2013.

3. Results

3.1. Classification of Rainfall Patterns

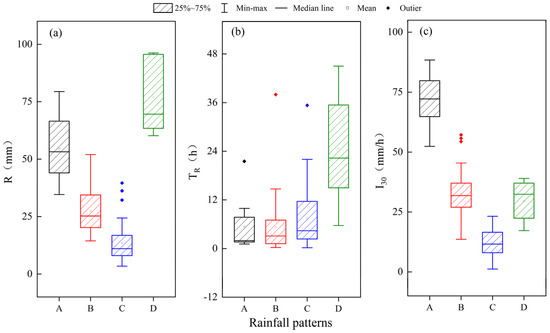

The statistical results of different rainfall patterns were based on the rainfall characteristic parameters of R, TR, and I30 of 97 erosive rainfall events (total rainfall was 2649.8 mm) (Figure 2). Pattern A, with a large R (45.1–64.3 mm), medium TR (1.6–7.5 h), and the highest I30 (66.6–78.3 mm/h), occurred 12 times, and the cumulative rainfall was 655.8 mm. Pattern B, characterized by a medium R (20.3–34.1 mm), short TR (1.2–7.0 h), and medium I30 (27.1–37.0 mm/h), occurred 38 times and had the highest cumulative rainfall (1042.00 mm), accounting for 39.3% of the total rainfall. Pattern C was characterized by the lowest R (9.7–16.5 mm), medium TR (2.4–11.4 h), and the lowest I30 (8.1–16.2 mm/h), and had the highest frequency (42 times), accounting for 43.3% of the total rainfall events, and its rainfall depth was 567.0 mm. Pattern D was characterized by the largest R (63.4–95.6 mm), the longest TR (14.9–35.4 h), and medium I30 (22.4–37.0 mm/h), which had the lowest frequency (five times) and the smallest cumulative rainfall depth (385.0 mm).

Figure 2.

Statistical features of (a) rainfall (R), (b) rainfall duration(TR) and (c) the maximum rainfall intensity in 30 min (I30); among the four rainfall patterns. Note: the colors black, red, blue, and green represent rainfall patterns A, B, C, and D, respectively.

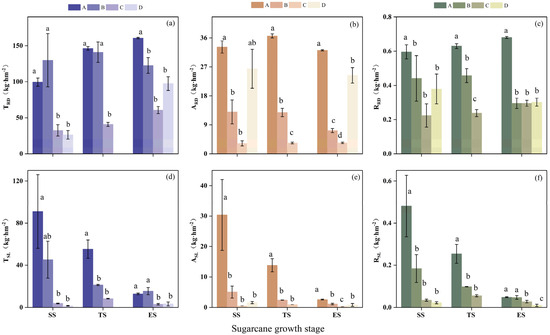

3.2. Runoff Depth and Sediment Yield

The results summarized from 97 erosive rainfall events showed the total of RC, RD, SC, and SL of pattern A were the highest, with 0.68, 406.5 mm, 39.05 kg m−3, and 159,181.61 kg/hm2, while pattern C had the lowest values (Table 2). Mean RD and SL of pattern A were 3.3, 10.4, and 1.4 and were 5.2, 24.0, and 13.7 times larger than those under patterns B, C, and D; there existed significant differences among pattern A and the other three patterns. The variation in RD and SL across the growth stages is presented in Figure 3, the highest RD concentrated on the ES (41.7% of the total) is times higher than other stages, while the minimum occurred at the SS (27.2%). The SL showed SS (50.2%) > TS (31.78%) > ES (18.0%). As shown in Figure 3, the TRD under different patterns is exhibited as pattern A (38.3%) > B (37.1%) > D (12.9%) > C (11.7%), while, for ARD, it is exhibited as A > D > B > C. Although similar order trends were found for sediment yield, TSL was followed by pattern A (61.0%) > B (31.4%) > C (5.7%) > D (1.9%), for example, indicating the effects of the rainfall pattern on sediment yield were more obvious than those on runoff. There were no differences between ARD and RRD under pattern A among all sugarcane stages, but these values under pattern A were obviously higher than those under the other patterns across all growth stages. Remarkably, the ASL induced by pattern A were 6.0 to 19.4, 5.8 to 15.1, and 2.3 to 9.3 times larger than those under the other rainfall patterns for the SS, TS, and ES, respectively (Figure 3e). In particularly, the ASL induced by pattern A at the SS (30,369.3 kg/hm2) was significantly higher than that at the TS (13,833.4 kg/hm2) and ES (2548.0 kg/hm2). The same changing trend was also found for RSL.

Table 2.

Runoff and sediment yield characteristics under different rainfall patterns.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of runoff and sediment loss under different rainfall patterns in different sugarcane growth periods. Note: SS, seeding stage; TS, tillering stage; ES, elongation stage; different letters indicate significant differences between different rainfall patterns under the same growth stage at p < 0.05. (a) TRD, the total runoff depth; (b) ARD, the average of runoff depth; (c) RRD, the volume of runoff depth caused by unit rainfall; (d) TSL, the volume of total sediment yield; (e) ASL, the average of sediment yield; (f) RSL, the volume of sediment yield caused by unit rainfall.

3.3. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loss in Runoff and Sediment Yield

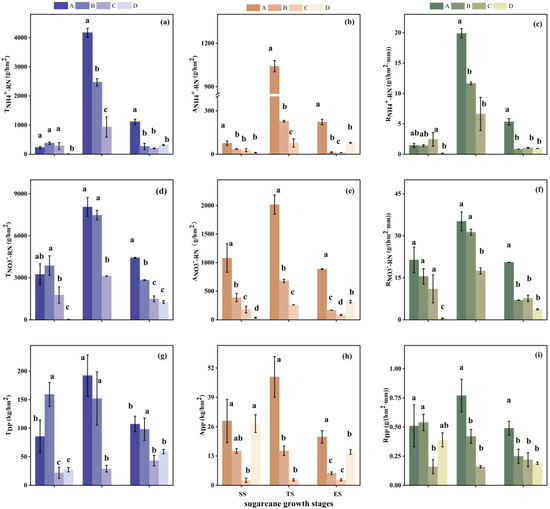

3.3.1. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loss in Runoff

The characteristics of nitrogen and phosphorus concentration in runoff under each rainfall pattern are shown in Table 3. The NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and DP concentrations under the four rainfall patterns ranged from 0.10 to 18.46, 0.02 to 11.68, and 0.01 to 0.038 mg/L, and the average NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and DP losses under pattern A were significantly higher and were 5.4 to 13.5, 3.4 to 8.4 times, and 1.9 to 14.2 times higher than those under pattern B, C, and D. The NH4+–N and NO3−–N in the runoff varied considerably across the growth stages (Figure 4), and concentrated on the TS, accounting for 49.6% and 73.1%. The DP loss followed the order of TS (373.4 g/hm2) > ES (307.9 g/hm2) > SS (294.3 g/hm2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and DP loss in runoff under each rainfall pattern.

Figure 4.

Characteristics of NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and DP loss in runoff under different rainfall patterns at different sugarcane growth periods. Note: SS, seeding stage; TS, tillering stage; ES, elongation stage; different letters indicate significant differences between different rainfall patterns under the same growth stage at p < 0.05. (a) TNH4+−RN, the volume of NH4+–N loss in runoff; (b) ARNH4+–N, the average of NH4+–N loss in runoff; (c) RNH4+–RN, the volume of NH4+–N loss in runoff caused by unit rainfall; (d) TNO3−–RN, the volume of NO3−–N loss in runoff; (e) ANO3−–RN, the average of NO3−–N loss in runoff; (f) RNO3−–RN, the volume of NO3−–N loss in runoff caused by unit rainfall; (g) TDP, the volume of DP loss in runoff; (h) ADP, the average of DP loss in runoff; (i) RDP, the volume of DP loss in runoff caused by unit rainfall.

As presented in Figure 5a, TNH4+–RN under patterns A, B, C, and D accounted for 52.6%, 30.7%, 13.6%, and 3.2% of total NH4+–N loss. Additionally, TNH4+–RN, ANH4+–RN, and RNH4+–RN under pattern A, with 228.4 g/hm2, 76.1 g/hm2, and 19.9 g/(hm2·mm) at the TS for example, were 1.7 to 16.6, 4.6 to 13.4, and 1.7 to 3.0 times greater than those under pattern B, and C, respectively (Figure 4a–c). The results also indicated TNH4+–RN, ANH4+–RN, and RNH4+–RN under all patterns were concentrated in the TS, which were remarkably different with the distributions of runoff (Figure 4a–c). TNO3−–RN induced by pattern A and B, which were 8063.4, and 7475.9 g/hm2, accounted for 43.2% and 40.01% of total NO3−–N loss. ANO3−–RN under pattern A among all sugarcane stages was 2015.9 g/hm2, which was significantly higher than others. RNO3−–RN under different patterns showed a similar trend, but the gaps among different rainfall patterns were much smaller than those in ANO3−–RN (Figure 5f). The results also showed that NO3−–N was the main form of dissolved N loss in runoff, accounting for 78.1% of total. The DP loss in runoff under rainfall pattern A and B, which contributed to 81.4% of the TDP (Figure 4e), and ADP and RDP under pattern A and B at TS were significantly higher than those of patterns C and D (p < 0.05) (Figure 5h,i). According to Figure 5e–i, pattern A at the TS induced the maximum TDP, ADP, and RDP, with values of 385.4 g/hm2, 32.1 g/hm2, and 0.77 g/(hm2·mm), while the minimum values occurred under pattern C or B.

Figure 5.

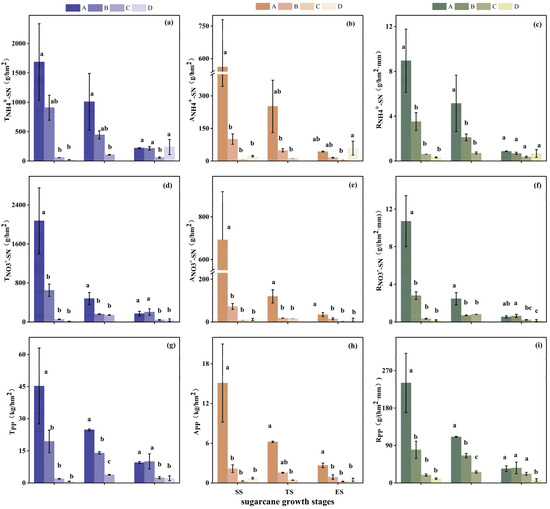

Characteristics of NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and PP loss in sediment under different rainfall patterns at different sugarcane growth periods. Note: SS, seeding stage; TS, tillering stage; ES, elongation stage; different letters indicate significant differences between different rainfall patterns under the same growth stage at p < 0.05. (a) TNH4+–SN, the volume of NH4+–N loss in sediemnt; (b) ANH4+–SN, the average of NH4+–N loss in sediment; (c) RNH4+–SN, the volume of NH4+–N loss in sediment caused by unit rainfall; (d) TNO3−–SN, the volume of NO3−–N loss in sediment; (e) ANO3−–SN, the average of NO3−–N loss in sediment; (f) RNO3−–SN, the volume of NO3−–N loss in sediment caused by unit rainfall. (g) TPP, the volume of PP loss in sediment; (h) APP, the average of PP loss in sediment; (i) RPP, the volume of PP loss in sediment caused by unit rainfall.

3.3.2. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loss in Sediment

According to Table 4, the variations in nutrient concentrations in sediment were quite different than those in runoff. For different rainfall patterns, concentrations of NH4+–N and NO3−–N in sediment were in the ranges of 5.55 to 110.00 and 0.64 to 33.74 mg/kg. The mean NH4+–N losses in sediment under all patterns were nearly equal to those in runoff, while NO3−–N losses in sediment among the four patterns were only 4.7%~17.8% of that in runoff. The highest NH4+–N (53.9%) and NO3−–N (69.3%) losses in sediment losses occurred in the ES with minimum sugarcane cover. TNH4+–SN, ANH4+–SN, and RNH4+–SN under pattern A in the SS were 1684.7 g/hm2, 561.6 g/hm2, and 9.0 g/(hm2·mm), and were higher than those in the other patterns (Figure 5a–c). However, no obvious differences among the four patterns were found in the ES. In addition, the values of TNH4+–N, ANH4+–N, and RNH4+–N under all patterns sharply decreased with increasing of sugarcane coverage, especially under pattern A. Simultaneously, the TNO3−–N induced by pattern A accounted 67.73% of the total NO3−–N loss in the sediment; TNO3−–N, ANO3−–N, and RNO3−–N under pattern A in the SS, with 2077.6 g/hm2, 692.5 g/hm2, 10.7 g/(hm2·mm), were 3.2 to 177.9, 9.6 to 59.3, 3.8 to 63.9 times the other three patterns in the SS (Figure 5d–f). Additionally, TNO3−–SN, ANO3−–SN, and RNO3−–SN under pattern A in the TS and ES were 8.3% to 23.1%, 5.0% to 17.3%, and 5.0% to 23.0% of those under pattern A in the SS. Nevertheless, unlike what occurred in runoff, compared with those in the SS, the TNO3−–SN, ANO3−–SN, and RNO3−–SN decreased sharply under all rainfall patterns in ES and TS.

Table 4.

Characteristics of NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and PP loss in sediment under each rainfall pattern.

No significant differences in PP concentrations in sediment among the four patterns were observed. PP losses were highly consistent with those of sediment yields under all patterns. The highest PP loss occurred in the SS, being 1.6 and 2.8 times the amount of the TS and ES. PP loss under pattern A was the highest, with 79,610.4 g/hm2, while that of pattern D was the lowest. The mean PP loss under pattern A was 6634.20 g/hm2, which was 4.7 to 22.2 times larger than those under the other three patterns. They were 2.3 to 23.1, 7.0 to 54.0, and 3.0 to 23.1 times greater than the TPP, APP, and RPP under pattern A in the SS compared with pattern B, C, and D. Moreover, TPP, APP, and RPP decreased significantly under all patterns from the SS to the ES (Figure 5g–i).

3.4. The Effect of Rainfall Parameters on Soil Erosion and Nutrition Loss Under Different Sugarcane Growth Stages

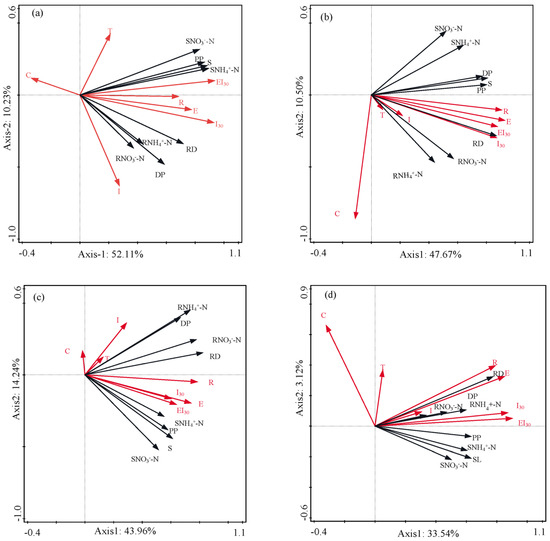

Pearson correlation showed that rainfall parameters were significantly correlated with RD, SL, and N and P loss (Figure S2). But there was not a significant relationship between sugarcane coverage and soil erosion parameters. Redundancy analysis can be used to identify key factors contributing to soil erosion and nutrient loss in sugarcane fields (Figure 6 and Figure S2). From the response variables point of view, RD, SL and N and P loss mainly correlated with axis–1. Figure 6a showed that EI30 and E in the SS could explain 72.50% of the variation in soil erosion parameters (RD, SL, N, P), following rainfall intensity (I and I30) (accounted for 20.30%) (p < 0.01). For the TS, E played a dominant role on soil erosion parameters, with a contribution of 68.00% (Figure 6b), followed by C (13.50%) and I30(7.40%). In addition, the contributions of the R to soil erosion parameters was the highest in the ES, and rainfall parameters exhibited as R (42.6%) > I (14.9%) > I30 (13.4%) > T (13.3%) (p < 0.05). The coverage only accounted for 0.3%~3.7% of the variation in soil erosion parameters under different patterns and was negatively correlated with soil erosion parameters (Figure 6a–d).

Figure 6.

Ordination plot of redundancy analysis (RDA) for RD, SL, and N and P loss constrained by all rainfall parameters and sugarcane coverage under (a) SS, (b) TS, (c) ES, and (d) the entire observation period. Note: abbreviations of affecting factors are as follows: R: rainfall. TR: rainfall duration. I: mean rainfall intensity. I30: the maximum rainfall intensity in 30 min; E: the mean kinetic energy of rainfall; EI30: the rainfall erosivity. C: sugarcane coverage.

4. Discussion

In this study, pattern A, with high precipitation and rainfall intensity, which contributed 38.3% and 61.0% of total runoff and sediment yield, induced significantly higher soil and nutrient losses than other rainfall patterns. High rainfall intensity has a strong ability to separate soil particles and form surface crusts, and then runoff depth increased by decreasing soil infiltration. Generally, higher sediment yield occurred because of the increasing of runoff transportation ability, and explained why higher runoff and sediment yield occurred under pattern A. Meanwhile, compared with other rainfall patterns, the increasing influences of pattern A on sediment yield were obviously higher than those on runoff. This was probably ascribed to runoff generation and the amount mainly depended on soil conditions and rainfall precipitation [47]. Near-saturated antecedent soil moisture could lead to higher runoff depth, even under low rainfall precipitation [48], such as in pattern B and C. For the clay soil used in this study, the energy of raindrop impact is insufficient to break surface soil aggregates, and sediment concentrations were quite low as not enough fine material could be transported by runoff. This characteristic results in slight increase in sediment yield with an obvious increase in runoff (Figure 3). Those results were also consistent with the theories of (Kinnell 2005; 2020) [16]. During the elongation stage, both precipitation volume and frequency exceeded those observed in other growth stages (Figure S4). This accounts for the sustained higher runoff levels under high canopy coverage conditions during this period, a correlation further substantiated by our redundancy analysis results (Figure 6c and Figure S4). However, the TRD, ARD, and RRD under all rainfall patterns varied slightly among different sugarcane stages, while TSL, ASL, and RSL decreased sharply with the increase in sugarcane coverage, particularly for pattern A. The slight fluctuation in runoff under each rainfall pattern among sugarcane growth periods can be attributed to the low hydraulic conductivity of clay soil and high initial soil moisture during filed observation periods (Sachs and Sarah 2017) [49]. Hence, no obvious differences in runoff coefficients were found among pattern B, C, and D. For pattern A with high rainfall intensity, sediment transport was dominated by suspension/saltation and rolling under rainfall conditions [50], resulting in a higher RSL eventually. In our results, TSL and ASL at the seedling stage were significantly higher than those at other growth stage, especially under pattern A. Our results are consistent with the experimental findings of Yu et al., (2025) [51] in the laterite region, demonstrating that sugarcane growth can effectively mitigate the soil and water loss caused by heavy rainfall, with its protective effect significantly enhancing as sugarcane grows. This phenomenon was inextricably related to the role of vegetation and topsoil conditions. On the one hand, the vegetation canopy can intercept rainfall and lessen the quantity of rain that lands on the ground through leaves and other means [52,53]. Compared with the other stages, the lower vegetation coverage (11.4%) at the seeding stage cannot significantly reduce soil erosion by intercepting rainfall and decreasing raindrop kinetic energy [39]. In this study, the significant negative relationships between RD and SL with sugarcane coverage (Figure 6d) also validated those results. On the other hand, vegetation roots can improve the soil pore structure, infiltration capacity, and root binding and bonding effects, thus significantly increasing erosion resistance and reducing soil erosion [54,55,56,57], but the crop root density is low at the SS [58]. Simultaneously, the expanding root system, particularly roots with diameters less than 1 mm and those between 1 and 2 mm, enhances soil stabilization, and these effects could potentially be intensified with sugarcane growth [43].

The results indicated average NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and DP losses under pattern A, with 456.85, 1273.66, and 32.11 g/hm2, which were 5.4 to 13.5, 3.4 to 8.4, and 1.9 to 14.2 times as those under pattern B, C, and D (Table 3 and Table 4). Ramos et al., (2019) [59] reported that nutrient loss under high rainfall intensity was greater than that under low rainfall intensity. Meanwhile, the losses of NH4+–N, NO3−–N and DP under each rainfall pattern showed different responses compared to concentrations of those. High NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and DP losses under pattern A suggested that N and P losses were mainly dependent on runoff or sediment yield rather than their concentrations [24,33,60]. Increasing runoff depths with rainfall intensity and precipitation were associated with diminished NO3−–N concentrations in runoff [16]. These results were consistent with the previous findings of Li et al., (2022) [27]. In addition, runoff is the main route of nutrient loss [61,62,63], particularly for N lost, and NO3−–N was the main component of inorganic N in runoff. This was attributed to soil NO3−–N being easily lost with runoff in dissolved form [50]. Additionally, NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and DP in runoff under all rainfall patterns were mainly concentrated in the tillering stage, while sediment was in the seeding stage. The distributions of NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and DP in runoff among sugarcane growth stages displayed marked differences with particulate nutrient Higher NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and DP losses in the TS indicated that nutrient losses were highly associated with fertilizer management [27,64]. In this study, the loss of dissolved nutrients mainly occurred in June (Table S1), which is the period of sugarcane tillering. The vegetation coverage is low at this time, and appropriately increasing slope coverage can reduce soil erosion and nutrient loss. In addition, June is the critical period for applying fertilizer to promote tillering. The urea applied as a topdressing directly accelerated the loss of nitrogen. The reduction in sediment is the most direct cause of the decrease in nutrient loss (particularly PP) [8,65]. Furthermore, vegetation coverage further affects nutrient loss by affecting sediment transport mechanisms [66,67,68]. As the rate of vegetation coverage increased, the sediment yield decreased. Almost all the rainfall factors significantly affected the loss of nutrients, but I30 played a dominant role in influencing nutrient loss [31,69]. Figure 6 also indicated that the correlation between sugarcane coverage and the response variables was less than that of most of rainfall parameters. This highlights that soil erosion and nutrient loss in sugarcane fields are influenced by multi–scale factors, including land management practices, fertilizer application, and rainfall runoff. To reduce soil and water loss, it is crucial to avoid fertilization during periods of low ground cover and heavy rainfall. To confirm the validity of results, further studies or verification tests in the field under artificial simulated rainfall should be conducted in the future.

In this study, the soil erosion and nutrient loss characteristics of 97 erosive rainfalls in different sugarcane growing stages were analyzed. The results provided basic data for the study on the effects of different rain patterns on soil erosion and nutrient loss of sugarcane land. However, due to the lack of sugarcane roots, the magnitude of nutrient loss may not be sufficient to reflect the influence of entire rainfall levels during sugarcane growth.

5. Conclusions

A 4-year field monitoring experiment indicated that rainfall patterns and sugarcane growth stage significantly affected runoff, sediment yield, and N and P loss on sugarcane-cultivated slopes and quantified their loss characteristics across sugarcane growth stages. Rainfalls with large R, medium TR, and the highest I30 (pattern A) induced the highest mean runoff, sediment yield, and nutrient losses (p < 0.05). NH4+–N and NO3−–N were predominantly lost with runoff, while P was mainly transported with sediment. The highest runoff and nutrient loss in the runoff were obtained in the ES and TS, respectively, while SL and nutrient losses were concentrated in the SS. EI30 was the main factor that aggravated soil erosion in sugarcane slopes, while the contribution of EI30 to soil erosion declined as the sugarcane grew. Therefore, we recommend tailoring conservation practices to specific growth stages: increasing ground cover, especially in the seedling stage, to directly reduce rainfall-induced sediment and PP loss, and advancing tillering-stage fertilization to avoid the peak rainy season, thus minimizing nitrate nitrogen leaching. These findings contribute to reducing runoff-related N and P losses by rainfall patterns with high rainfall amounts, thereby preventing environmental degradation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15112531/s1, Figure S1: Characteristics of erosive rainfall in the study area during the observation period; Figure S2: Pearson correlation between rainfall parameters, sugarcane coverage and RD, SL, and N and P loss under the (a) SS, (b) TS, (c) ES, and (d) the entire observation period. Note: abbreviations of affecting factors are as follows: R: rainfall. TR: rainfall duration. I: mean rainfall intensity. I30: the maximum rainfall intensity in 30 min; E: the mean kinetic energy of rainfall; EI30: the rainfall erosivity. C: sugarcane coverage. Figures (a), (b), (c), (d) represent patterns A, B, C, and D, respectively. *** indicates p < 0.001, ** indicates p < 0.01, * indicates p < 0.05; Figure S3: The contribution rate of factors in affecting the loss of RD, SL, and N and P under the (a) SS, (b) TS, (c) ES, and (d) the entire observation period in RDA. ** indicates p < 0.01, * indicates p < 0.05; Figure S4: The characteristic rainfall depth (a) and number of runoff events (b) at different sugarcane growth stages. Table S1: Date of fertilization.

Author Contributions

G.L. and Y.H. designed the experiment. Y.H., R.Y., M.W., H.L. and Y.Z. conducted the experiment. Y.H. and G.L. wrote the manuscript. Y.H. and R.Y. analyzed the data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [41967010]; the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation [2018GXNSFBA138024]; and the Young and Middle-aged Teachers’ Research Foundation Improvement Project in Guangxi Colleges and Universities [2024KY2024].

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hao Guo for his insightful comments on the manuscript. We also acknowledge the assistance of Tao Chen, Haoyu Yang, Zigui Zhao, Yeyang Wang, Jiali Ning, and Zhaozhu Chen in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| SS | Seeding stage |

| TS | Tillering stage |

| ES | Elongation stage |

| RD | Runoff depth |

| SL | Sediment yield |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NO3−–N | Nitrate nitrogen |

| NH4+–N | Ammonium nitrogen |

| NO3−–RN | Nitrate nitrogen loss in runoff |

| NO3−–SN | Nitrate nitrogen loss in sediment |

| NH4+–RN | Ammonium nitrogen loss in runoff |

| NH4+–SN | Ammonium nitrogen loss in sediment |

| P | Phosphorus |

| DP | Dissolved phosphorus |

| PP | Particulate phosphorus |

| TRD | The total amount of runoff depth |

| TSL | The total amount of sediment yield |

| TRN | With respect to the TNO3−–RN and TNH4+–RN means the total amount of nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen loss in runoff |

| TSN | With respect to the TNO3−–SN and TNH4+–SN, means the total amount of nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen loss in sediment |

| ARD | The average of runoff depth |

| ASL | The average of sediment yield |

| ARN | With respect to ANO3−–RN and ANH4+–RN, and means the average of nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen loss in runoff |

| ASN | With respect to the ANO3−–SN and ANH4+–SN, means the average of nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen loss in sediment |

| RRD | The volume of runoff depth caused by unit rainfall |

| RSL | The amount of sediment yield caused by unit rainfall |

| RRN | With respect to RNO3−–RN and RNH4+–RN, and means the amount of nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen loss in runoff caused by unit rainfall |

| RSN | With respect to the TNO3−–SN and TNH4+–SN, and means the amount of nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen loss in sediment caused by unit rainfall |

| R | Rainfall amount |

| TR | Rainfall duration |

| I | Mean rainfall intensity |

| I30 | 30 min maximum rainfall intensity |

| E | The mean kinetic energy of rainfall |

| EI30 | The rainfall erosivity |

References

- Adimassu, Z.; Mekonnen, K.; Yirga, C.; Kessler, A. Effect of soil bunds on runoff, soil and nutrient losses, and crop yield in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2014, 25, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.T.; Bertol, I.; Luciano, R.V.; Gonzalez, A.P. Phosphorus losses in water and sediments in runoff of the water erosion in oat and vetch cropsseed in contour and downhill. Soil. Tillage Res. 2009, 106, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.K.; Zhan, X.Y.; Zhou, F.; Yan, X.Y.; Gu, B.J.; Rei, S.; Wu, Y.L.; Liu, H.B.; Piao, S.L.; Tang, Y.H. Detection and attribution of nitrogen runoff trend in China’s croplands. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitzinger, S.P.; Mayorga, E.; Bouwman, A.F.; Kroeze, C.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Billen, G.; Van Drecht, G.; Dumont, E.; Fekete, B.M.; Garnier, J.; et al. Global River Nutrient Export: A Scenario Analysis of Past and Future Trends. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2010, 24, 2621–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Wu, H.; Yao, M.Y.; Zhou, J.; Wu, K.B.; Hu, M.P.; Shen, H.; Chen, D.J. Estimation of nitrogen runoff loss from croplands in the yangtze river basin: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 272, 116001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.Y.; Liu, C.J.; Yu, X.X.; Chen, L.H.; Zheng, W.G.; Yang, Y.H.; Yin, C.W. Direct and indirect effects of rainfall and vegetation coverage on runoff, soil loss, and nutrient loss in a semi-humid climate. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.Q.; Xu, J.; Mo, Y.M.; Tang, H.W.; Wei, T.; Wang, Y.G.; Li, L. Response of sediments and phosphorus to catchment characteristics and human activities under different rainfall patterns with Bayesian Networks. J. Hydrol. 2020, 584, 124695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L.; Hu, Y.X.; Li, Z.W.; Yu, X.X. Relating rainfall, runoff, and sediment to phosphorus loss in northern rocky mountainous area of China. Catena 2024, 247, 108504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.F.; Zhang, J.Q.; Shang, Y.T.; Wu, K.Z.; Bai, R.R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M.Y. Correlation between flood couplet-based sediment yield and rainfall patterns in a small watershed on the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2024, 637, 131407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, S.Y.; Huang, Y.R.; Chen, M.H.; Huang, L. Modeling of rainfall induced phosphorus transport from soil to runoff with consideration of phosphorus-sediment interactions. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.N.; He, Y.F.; Chen, J.; Huang, Q.; Lian, X.; Wang, H.C.; Liu, Y.L. Nitrogen surface runoff losses from a Chinese cabbage field under different nitrogen treatments in the Taihu Lake Basin.; China. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 159, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Li, B.L.; Han, W.Y.; Liu, D.B.; Gan, X.Z. Nitrogen and phosphorus losses by runoff erosion: Field data monitored under natural rainfall in three gorges reservoir area, China. Catena 2016, 147, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavinia, M.; Saleh, F.N.; Asadi, H. Effects of rainfall patterns on runoff and rainfall-induced erosion. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2019, 34, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ni, J.P.; Ni, C.S.; Wang, S.; Xie, D.T. Effect of natural rainfall on the migration characteristics of runoff and sediment on purple soil sloping cropland during different planting stages. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, 3064–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, L.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Spalevic, V.; Cerda, A.; Kavian, A. Effect of storm pattern on soil erosion in damaged rangeland; field rainfall simulation approach. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, P.J.A.; Srinivasan, M.S.; Dell, C.J.; Schmidt, J.P.; Sharpley, A.N.; Bryant, R.B. Role of rainfall intensity and hydrology in nutrient transport via surface runoff. J. Environ. Quality 2006, 35, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.H.; Su, D.Y.; Li, P.; He, Z.G. Experimental study of the impact of rainfall characteristics on runoff generation and soil erosion. J. Hydrol. 2012, 424, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkerley, D. Rain event properties in nature and in rainfall simulation experiments: A comparative review with recommendations for increasingly systematic study and reporting. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 4415–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, X.P.; Abla, M.; Lü, D.; Yan, R.; Ren, Q.F.; Ren, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Zhao, W.H.; Lin, P.F.; et al. Effects of vegetation and rainfall types on surface runoff and soil erosion on steep slopes on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2018, 170, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, Q.H.; Ding, P.W.; Yao, Y.W.; Li, K.F.; Yan, Y.J.; Yi, X.S.; He, J. Effects of rainfall intensity and underground pore density on the soil erosion mechanism of sloping maize farmland in a typical karst area of SW China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 1910–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhang, P.; Shen, Z. Runoff characteristics and nutrient loss mechanism from plain farmland under simulated rainfall conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Zhai, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, A.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Lei, Q. Cross-ridge tillage decreases nitrogen and phosphorus losses from sloping farmlands in southern hilly regions of China. Soil. Tillage Res. 2019, 191, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, K.N.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, Z.H. Effects of tillage practices on runoff and soil losses in response to different crop growth stages in the red soil region of southern china. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 2199–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D.; Singh, P.; Nakamura, K. Spatiotemporal variation of rainfall over the central himalayan region revealed by trmm precipitation radar. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D22106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.Y.; Lei, A.; Lei, J.S.; Ye, M.; Zhao, J.Z. Effects of hydrological processes on nitrogen loss in Purple Soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2007, 89, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewry, J.J.; Newham, L.T.H.; Croke, B.F.W. Suspended sediment, nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations and exports during storm-events to the Tuross Estuary, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, B.H.; Wu, X.Y.; Du, Y.N. Nitrate loss by runoff in response to rainfall amount category and different combinations of fertilization and cultivation in sloping croplands. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 273, 107916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Zuazo, V.H.; Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; García-Tejero, I.F. Cover Crop Effects on Surface Runoff and Subsurface Flow in Rainfed Hillslope Farming and Connections to Water Quality. Land 2024, 13, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Abegunrin, T.P.; Guo, H.; Huang, Z.G.; Are, K.S.; Wang, H.; Gu, M.; Wei, L. Variation of dissolved nutrient exports by surface runoff from sugarcane watershed is controlled by fertilizer application and ground cover. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 303, 10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Q.; Ma, R.; Wang, N.N.; Wang, S.; Li, T.X.; Zheng, Z.C. Comparison of nitrogen losses by runoff from two different cultivating patterns in sloping farmland with yellow soil during maize growth in Southwest China. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Yang, P.; Ren, S.; Ao, C.; Li, X.; Gao, W. Slope length effects on processes of total nitrogen loss under simulated rainfall. Catena 2016, 139, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Zhang, W.W.; Wu, J.Y.; Li, H.J.; Zhao, T.K.; Zhao, C.Q.; Shi, R.S.; Li, Z.S.; Wang, C.; Li, C. Loss of nitrogen and phosphorus from farmland runoff and the interception effect of an ecological drainage ditch in the North China Plain-A field study in a modern agricultural park. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udawatta, R.P.; Motavalli, P.P.; Garrett HE Krstansky, J.J. Nitrogen losses in runoff from three adjacent agricultural watersheds with claypan soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 117, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siller, A.R.S.; Albrecht, K.A.; Jokela, W.E. Soil Erosion and Nutrient Runoff in Corn Silage Production with Kura Clover Living Mulch and Winter Rye. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, W.F. Variations in soil detachment by rill flow during crop growth stages in sloping farmlands on the Loess Plateau. Catena 2022, 216, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xu, H.; He, S.Q.; Liang, X.L.; Zheng, Z.C.; Luo, Z.T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Tan, B. Characteristics of Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) Loss with Water Erosion in Sloping Farmland of Southwestern China during Maize (Zea mays L.) Growth Stages. Agronomy 2023, 13, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.; Gerstmann, H.; Gao, F.; Dahms, T.C.; Förster, M. Coupling of phenological information and simulated vegetation index time series: Limitations and potentials for the assessment and monitoring of soil erosion risk. Catena 2017, 150, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plambeck, N.O. Reassessment of the potential risk of soil erosion by water on agricultural land in Germany: Setting the stage for site-appropriate decision-making in soil and water resources management. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Li, P.; Li, Z.N.; Sun, J.M.; Wang, D.J.; Min, Z.Q. Effects of grass vegetation coverage and position on runoff and sediment yields on the slope of Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J. Effects of grain-forage crop type and natural rainfall regime on sloped runoff and soil erosion in the mollisols region of northeast China. Catena 2023, 222, 106888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Are, K.S.; Huang, Z.G.; Guo, H.; Wei, L.; Abegunrin, T.P.; Gu, M.; Qin, Z. Particulate N and P exports from sugarcane growing watershed are more influenced by surface runoff than fertilization. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.T.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.M.; Guo, H.; Huang, Z.G. Contribution of the ratoon sugarcane with planting years to river pollution evidenced from the four-year watershed observation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 373, 109099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.X.; Zheng, J.S.; Li, G.F.; Huang, Y.H.; Wang, J.H.; Qiu, F. Effects of rainfall characteristics and sugarcane growth stage on soil and nitrogen losses. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 87575–87587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2023/indexeh.htm (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Han, Y.; Zheng, F.L.; Xu, X.M. Effects of rainfall regime and its character indices on soil loss at loessial hillslope with ephemeral gully. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Nie, X.; Liu, Z.; Mo, M.; Song, Y. Identifying optimal ridge practices under different rainfall types on runoff and soil loss from sloping farmland in a humid subtropical region of southern China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, K.; Bholah, A.; Volcy, L.; Pynee, K. Nitrogen and phosphorus transport by surface runoff from a silty clay loam soil under sugarcane in the humid tropical environment of Mauritius. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 91, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, M.Z. Effects of antecedent soil moisture on runoff and soil erosion in alley cropping systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2007, 94, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, E.; Sarah, P. Combined effect of rain temperature and antecedent soil moisture on runoff and erosion on Loess. Catena 2017, 158, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.L.; Wei, Y.J.; Wang, J.G.; Wang, D.; She, L.; Wang, J.; Cai, C.F. Effects of soil physicochemical properties on aggregate stability along a weathering gradient. Catena 2017, 156, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Li, C. Influence of Sugarcane on Runoff and Sediment Yield in Sloping Laterite Soils During High-Intensity Rainfall. Agronomy 2025, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoneli, V.; de Jesus, F.C.; Bednarz, J.A.; Thomaz, E.L. Stemflow and throughfall in agricultural crops: A synthesis. Rev. Ambiente Água 2021, 16, e2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Chen, K.B.; Zhang, Q.W.; Wang, C.F.; Lu, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, F.Q. The contribution rate of stem-leaf and root of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) to sediment and runoff reduction. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3991–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.P.; da Costa Silva, R.W.; de Andrade, T.M.B.; Salemi, L.F.; de Camargo, P.B.; Martinelli, L.A.; de Moraes, J.M. Stemflow generation as Influenced by Sugarcane Canopy Development. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; He, J.S.; Dong, K.B.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Xiao, J.B.; Feng, L.S. Factors influencing maize stemflow in western Liaoning, China. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 2708–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Shih, C.Y.; Wang, J.T.; Liang, Y.H.; Hsu, Y.S.; Lee, M.J. Root traits and erosion resistance of three endemic grasses for estuarine sand drift control. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mo, Y.Q.; Are, K.S.; Huang, Z.; Guo, H.; Tang, C.; Abegunrin, T.P.; Qin, Z.; Kang, Z.; Wang, X. Sugarcane planting patterns control ephemeral gully erosion and associated nutrient losses: Evidence from hillslope observation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 309, 10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zheng, Z.C.; Li, T.X.; He, S.Q.; Zhang, X.Z.; Wang, Y.D.; Huang, H.G.; Ye, D.H. Temporal variation of soil erosion resistance on sloping farmland during the growth stages of maize (Zea mays L.). Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.C.; Lizaga, I.; Gaspar, L.; Navas, A. Particulate phosphorus in runoff in a mediterranean agroforestry catchment driven by land use and rainfall characteristics. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 4882–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sänger, A.; Geisseler, D.; Ludwig, B. Effects of rainfall pattern on carbon and nitrogen dynamics in soil amended with biogas slurry and composted cattle manure. J. Plant Nutr. Soil. Sci. 2010, 173, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.F.; Fang, Y.; Fu, Y.Q.; Chen, N.W. Storm-induced nitrogen transport via surface runoff, interflow and groundwater in a pomelo agricultural watershed, southeast China. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, L.P.; Yu, X.X. Impacts of surface runoff and sediment on nitrogen and phosphorus loss in red soil region of southern China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 67, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.W.; Dai, Q.H.; Gao, R.X.; Gan, Y.X.; Yi, X.S. Effects of rainfall intensity on runoff and nutrient loss of gently sloping farmland in a karst area of sw China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Hao, Z.; Ma, X.; Gao, J.; Fan, X.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Lin, M.; Zhou, Y. Effects of different proportions of organic fertilizer replacing chemical fertilizer on soil nutrients and fertilizer utilization in gray desert soil. Agronomy 2024, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.N.; Zhang, S.H.; Ruan, Q.Y.; Tang, C.H. Synergetic impact of climate and vegetation cover on runoff; sediment, and nitrogen and phosphorus losses in the Jialing River Basin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnell, P.I.A. Raindrop-impact-induced erosion processes and prediction: A review. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 2815–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnell, P.I.A. The influence of time and other factors on soil loss produced by rain-impacted flow under artificial rainfall. J. Hydrol. 2020, 587, 125004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.H.; Liu, G.B.; Wang, G.L.; Wang, Y.X. Effects of vegetation cover and rainfall intensity on sediment-bound nutrient loss.; size composition and volume fractal dimension of sediment particles. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, L.D.; Fu, B.J.; Huang, Z.L.; Wu, D.P.; Gui, L.D. The effect of land uses and rainfall regimes on runoff and soil erosion in the semi-arid loess hilly area, China. J. Hydrol. 2007, 335, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).