Abstract

Under today’s climate warming, mitigating the risks of soil organic carbon (SOC) decomposition in cropping systems is critical to maintain carbon sequestration. This study posits that nitrogen addition rate and duration are the key factors influencing the responses of soil heterotrophic respiration (Rh) to climate warming in a cropping system. Based on soil sampled from traditional-agriculture rice-growing regions in the Taihu Lake Basin in eastern China, this study aimed to clarify how nitrogen addition strategies affect soil Rh and its temperature sensitivity (Q10) and to explore the underlying mechanisms of the changes in soil environment that influence carbon emissions under nitrogen addition through the Rh pathway. The results demonstrate that, with the increasing duration of nitrogen addition, soil Rh and its Q10 were initially increased but subsequently suppressed, and the inhibitory effect on soil Rh became apparent after six years of continuous addition. Further analysis revealed that decreases in C/N, pH, and extractable organic nitrogen and increases in mineral nitrogen are the primary factors suppressing soil Rh. These findings indicate that an optimized nitrogen addition strategy tailored to specific crops could achieve profitable crop yields while effectively mitigating the promoting effect of climate warming on SOC decomposition.

1. Introduction

As an important carbon storage reservoir on planet Earth, terrestrial ecosystems‘ carbon release mainly manifests through soil respiration [1]. While agricultural systems serve as the material supply frontline for ensuring human survival, they function not only as a major source of greenhouse gas emissions but also as a substantial carbon sink system [2,3]. Therefore, mitigating the current carbon loss caused by intensive farming and enhancing the carbon sink capacity of agricultural systems are crucial for restoring soil functions, maintaining ecosystem stability, and safeguarding the sustainability of agricultural production [4,5]. Notably, humans interfere with agricultural systems more profoundly than with any other terrestrial ecosystem. This intensive human intervention not only enhances the differentiation of soil respiration intensity across diverse agricultural systems but also endows the soil respiration intensity within agricultural systems with controllability [6,7]. Among the various factors influencing soil respiration, nitrogen input stands out as a crucial factor in altering carbon cycle fluxes via this pathway [8,9]. Additionally, agricultural systems are characterized by annual crop biomass harvests driven by production goals, and nitrogen input from chemical fertilizers is a necessary measure to ensure product yields. Moreover, its input intensity (reaching 120–300 kg ha−1 per single cultivation season for rice, wheat, and oil rapeseed in the Taihu Lake Basin [10]) is significantly higher than that of most other terrestrial ecosystems (their primary exogenous nitrogen input occurs through atmospheric deposition, typically below 30 kg ha−1 [11]). These unique features make the response of soil respiration to various nitrogen addition strategies in agricultural systems distinct from that in other terrestrial ecosystems.

Regarding soil respiration (Rs), its response to nitrogen addition in agricultural systems is the outcome of the interaction between crop roots (an important subject of soil autotrophic respiration) [12] and soil microorganisms (an important subject of soil heterotrophic respiration (Rh)) [13,14]. The influence of nitrogen addition on soil autotrophic respiration via crop roots is regulated by multiple anthropogenic factors, including crop variety characteristics, interannual harvesting frequency, and crop residue disposal methods [12,15,16], thereby exhibiting a high degree of complexity and limited controllability. Soil Rh utilizes soil carbon as its consumption substrate and accounts for more than 60% of total soil respiration [17], which makes it crucial in determining the carbon output of an agricultural system. By altering the abiotic environment of the soil, nitrogen addition may influence multiple aspects of soil microorganisms and, further, influence the soil Rh they mediate. Firstly, the nitrogen addition from agricultural activities may alter the soil organic carbon composition, affecting the accumulation of recalcitrant organic carbon and the content of readily degradable organic carbon, thereby changing the quantity and form of the consumable substrates available to soil microorganisms. Secondly, nitrogen addition may modify the physiochemical conditions of the soil (such as the pH, moisture, and temperature conditions) [18,19] and its carbon and nitrogen contents [14,20,21] and induce morphological changes [9,22], which, in turn, can cause changes in multiple factors including microbial biomass [15] and alterations in the structure of related microbial communities [23,24,25] and enzyme activity intensity [16]. Thirdly, nitrogen addition may also affect nutrient supply availability for soil microorganisms, thereby influencing microbial metabolic activity and their capacity to respond to environmental changes. Regarding soil Rh, its Q10 serves as a key indicator for measuring the risk of carbon loss. In the context of climate warming, studying the soil Rh’s Q10 enables more accurate prediction of Rh intensity in future warmer environments, thereby facilitating improved estimations of carbon loss magnitude in an agricultural system. In summary, it is believed that, in an agricultural system, taking soil Rh and its Q10 as the starting point, exploring the impact of nitrogen addition on carbon decomposition is of greater significance for achieving theoretical carbon regulation via nitrogen.

Nitrogen addition strategy encompasses three dimensions: nitrogen form, addition rate, and duration. Previous studies reported the promoting effect of nitrogen addition on soil Rh in grasslands, wetlands, and deserts, but the effect on agricultural systems was uncertain [7,26], with only a significant decrease in soil Rh observed in treatments with a high amount of nitrogen addition in wheat cultivation systems [27]. Moreover, a high nitrogen addition amount has also been reported to inhibit soil Rh in forest systems [28]. Furthermore, a study based on forest soils has found that the effect of nitrogen addition on soil Rs changes with addition duration, with a high addition amount causing the negative effects on soil Rs to occur earlier [28], and structural equation modeling has output the results of the negative effect of nitrogen addition duration on Rh [7,29]. These results all suggest that there may be an interaction effect between the rate and duration of nitrogen addition on soil Rh, but there are currently no relevant studies for agricultural systems. In this context, it is proposed that the relationship between nitrogen addition strategies and soil Rh in agricultural systems represents a promising issue requiring further investigation. It is, therefore, hypothesized that, in an agricultural system, a dynamic and potentially bidirectional response of soil Rh to nitrogen addition may occur depending on the nitrogen addition rate and duration. Meanwhile, in real life, the excessive application of nitrogen chemical fertilizers is a common problem for Chinese farmers nowadays [10]. They (especially conventional ones) tend to apply 50% to over 100% more nitrogen fertilizers than the current season’s crop requirements to secure their yield, rather than mitigating nitrogen losses to enhance fertilizer utilization efficiency [10]. Therefore, the exploration of the appropriate amount of nitrogen fertilizer and its dynamic adjustment on the time scale is key to balancing agricultural output and environmental impact [30]. While addressing the demands of agricultural production, if researchers could explore the impact patterns and main controlling factors of nitrogen addition strategies with respect to carbon decomposition, it would be possible to effectively increase the carbon pool of agricultural systems by adjusting the nitrogen input rate and duration.

Moreover, rice, as one of the most important food crops, plays a dual role of carbon source and carbon sink in the agroecosystem. The global total soil organic carbon (SOC) storage of rice farmlands is 18 Pg C, accounting for 1.2% of the global total soil SOC and 14.2% of the global farmland SOC [2]. China is the world’s largest producer of rice. Reducing carbon emissions from rice systems by controlling the soil Rh pathway, so as to further exploit the carbon sequestration potential of rice soil, plays an indispensable role in mitigating climate warming.

In this regard, this study utilized soil samples from traditional-agriculture rice-growing areas in the Taihu Lake Basin, eastern China, as the experimental subject and selected three test field sites with varying levels of nitrogen fertilizer application (the sites had been carrying out the preliminary exploration of the ‘chemical fertilizer reduction policy’ starting at different time points over the past 15 years). This study investigated the effects of annual-basis nitrogen addition strategies on soil Rh and its Q10 from two dimensions: the application rate and duration of nitrogen addition. By measuring the samples’ soil Rh value under different-temperature experimental conditions, we compared the differences in the effects of different long-term nitrogen addition strategies on soil Rh and its Q10. On this basis, short-term mineral nitrogen addition treatments were introduced to explore the temporal-scale response patterns of carbon release by soil Rh to nitrogen addition. Integrating the changing trends of soil-related factors, this study investigated the mechanistic pathways through which nitrogen addition influences carbon decomposition processes within agricultural cropping systems. The research findings advance our understanding of the mechanism of carbon regulation via nitrogen in agricultural cropping systems and provide a scientific theoretical foundation for both predicting the dynamic carbon-release patterns associated with soil Rh under long-term nitrogen addition conditions and enlarging the carbon sequestration pool in rice systems through optimized strategic nitrogen addition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Site Description

Three field sites, located in Changzhou (CZ), Suzhou (SZ), and Wuxi (WX) in the Taihu Lake Basin (eastern China), were selected as the subjects of this study. All field sites experience a northern subtropical humid monsoon climate with a similar annual mean temperature of 15–16 °C and abundant precipitation ranging between 800 and 1100 mm. All field sites have rice soil but with different origins: in the case of CZ and SZ sites, a clay loam soil derived from yellow soil, while in WX, a clay soil derived from lacustrine deposit. The main nutrient properties of the soil are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Site information, nitrogen experiment design, and soil (0–20 cm) characteristics.

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Experiment on Long-Term Nitrogen Fertilizer Application

These agricultural fields in the Taihu Lake Basin have been cultivated for decades or even centuries, with common crop-rotation systems including rice–wheat, rice–oilseed rape, and rice–fallow. Rice is transplanted in June and harvested in early November, followed by a winter season of either fallow or non-fallow. The selection of rotation crops is determined by individual farmers’ production strategies, which may be influenced by the guidance of the government’s year-by-year subsidy policies.

In order to minimize the confounding effects of differences in the annual total nitrogen input amount and forms brought about by crop rotation and various fertilizer types, all soil samples were collected from the rice–fallow rotation fields. All three field sites were under a rice–wheat rotation system before 2010. Subsequently, due to policy changes, they gradually adopted a rice–fallow system and remained as such in a yearly rotation. In the rice-growing season each year, 4 different long-term nitrogen addition rates were implemented as major parts of the experimental treatments at all three field sites, with chemical nitrogen fertilizer (urea) used exclusively. They were as follows: the farmers’ average nitrogen addition rate, N3 (270 kg ha−1); the recommended nitrogen addition rate, N2 (200–210 kg ha−1); the reference low nitrogen addition rate, N1 (150 kg ha−1); and no nitrogen, N0 (0 kg ha−1) (Table 1). Nitrogen fertilizers were applied exclusively during the rice-growing season, from June to August. All treatments varied solely in the nitrogen addition rate, whereas the rates and methods for phosphorus and potassium fertilizer remained constant across the 4 treatments.

In all three field sites, 3 or 4 independent replicate plots were established for each nitrogen treatment rate. Following the rice-harvest season in November, five soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm plough layer of each plot. At the time of sampling, most aboveground biomass had been removed from all sites, and no straw had yet been returned; only crop residues and root remnants remained in the fields. The collected soil samples were thoroughly homogenized and sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove stones and organic debris. The resulting composite samples, representative of each nitrogen treatment, were then stored at 4 °C for subsequent analysis and short-term nitrogen addition experiments.

By the time all the soil samples were collected in 2022, the N fertilizer experiments in rice growing at the three field sites had been ongoing for different lengths of time. Among the three sites, the 1-year site received nitrogen treatments for only 1 single rice-growing season (initiated in 2022, location: CZ), the 6-year site was subjected to four treatments for 6 rice-growing seasons (initiated in 2017, location: SZ), and the 11-year site had been carrying out experiments for 11 seasons (initiated in 2012, location: WX).

2.2.2. Short-Term Nitrogen Addition

Short-term nitrogen addition was set based on the soil samples with different long-term nitrogen fertilizer application rates and application durations. Short-term nitrogen addition to each soil sample occurred at three levels: SN0 (0 kg ha−1), SN1 (equivalent to 135 kg ha−1), and SN2 (equivalent to 270 kg ha−1). Urea was dissolved in deionized water and applied to soil samples to achieve the designed short-term N addition, and then all soil samples were placed in a well-ventilated location and maintained at 60% of the saturated water content daily for 15 days of pre-incubation at 20 °C.

2.3. Soil Incubation and Soil Rh Analysis

After nitrogen addition and pre-incubation, soil samples, equivalent to 20 g dry weight, were incubated in 150 mL glass bottles under changing temperatures with three replicates. Incubation temperature varied from 4 to 28 °C, with a step width of 4 °C for soil heterotrophic respiration analysis. The rates of soil Rh at different temperatures were determined from the change in CO2 concentration in headspace. The whole soil incubation period lasted for 8 days. A full description of the incubation system and measuring procedure was detailed by Chen [31].

2.4. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Analysis

Two sets of soil samples were used for the detection of soil carbon and nitrogen indicators. Set1 was the soil samples collected from long-term nitrogen fertilizer application plot in the 3 field sites prior to short-term nitrogen addition; Set2 was the soil samples after short-term nitrogen addition and incubation. Soil total nitrogen (TN) and soil organic carbon (SOC) contents were analyzed based on Set1 soil samples. Moreover, soil labile organic carbon (LOC), extractable organic nitrogen (EON), mineral nitrogen (MN), and microbial biomass carbon (Cmic) were analyzed based on Set1 and Set2 soil samples. Parts of soil samples were oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant mass then ground to pass a 0.149 mm sieve for TN and SOC analysis using an elemental analyzer (Thermo Flash EA1112, Waltham, MA, USA) and LOC analysis using a KMnO4 oxidized method detailed by Weil [32]. Fresh soil samples, stored at 4 °C, were used for Cmic analysis by a fumigation extraction method described by Vance [33]. For MN and EON analysis, fresh soil samples were extracted with 2 mol·L−1 KCl solution; after that, MN (NH4+-N + NO3−-N) and extractable total nitrogen (ETN) in the filtrate were analyzed by an autoanalyzer (Traacs 800, Bran & Luebbe, Tokyo, Japan). EON was determined by the difference between ETN and MN.

2.5. Calculations

The relationship of the rate of soil Rh was described by an exponential function:

where Rh20 is soil Rh rate (μg g−1 soil h−1); a is a fitting parameter referring to respiration rate at 20 °C; T is temperature (°C); and b is a parameter defining the temperature dependence of soil respiration. A reference respiration rate of 20 °C (Rh20) was then estimated with fitted Equation (1). The Q10 value, commonly referred to as Q10 of soil Rh, was calculated using Equation (2) [34]:

Rh20 = a × ebT

Q10 = e10b

The metabolic quotient of soil microbes, qmic, was calculated using Equation (3) [35]:

where Cmic was soil microbial biomass carbon.

qmic = Rh20 ÷ Cmic

The rate of soil Rh and its Q10 values measured under variable temperature control under laboratory conditions are placed in Tables S1 and S2.

Due to the differences in soil backgrounds among the three rice fields, the effect sizes of Rh20 and its Q10 brought about by nitrogen addition were used for comparison. An N0 and an SN0 treatment were set to indicate the degree of change in Rh20 or Q10 based on the corresponding comparison processing. Effect size of Rh20 or Q10 under different long-term nitrogen fertilizer application levels (N1, N2, or N3) or short-term nitrogen addition levels (SN1 or SN2) was calculated based on the value of Rh20 or Q10 under N0 or SN0 treatments. Effect sizes of pH, C/N, EON, and MN under different long-term nitrogen fertilizer application levels (N1, N2, or N3) were calculated based on the values of pH, C/N, EON, and MN under N0 treatments. Effect sizes of EON, MN, and qmic under short-term nitrogen addition levels (SN1 or SN2) were calculated based on the values under SN0 treatments.

2.6. Statistics

Significant differences in the changes in Rh20 and its Q10 value and soil environmental factors (pH, C/N, EON, and MN after long-term nitrogen fertilizer application) among the soil samples from each field site were tested using Duncan’s multiple-range test. Additionally, T test was used to test the significant differences between the changes in soil EON, MN, and qmic after short-term nitrogen addition.

Linear regression analysis was implemented to assess the effects of long-term nitrogen fertilizer application (LN) and short-term nitrogen addition (SN) rates on Rh20 and its Q10 value at each field site using Equation (4):

where NI represents nitrogen addition impact on Rh and its Q10 as affected by two variables (LN and SN). α is estimated coefficients, and α0 is the constant.

NI = α1 × LN + α2 × SN + α0

Further regression analysis was developed to estimate how Rh and its Q10 would respond to soil environmental factors under different durations of nitrogen addition using Equation (5):

where SI represents soil environment impact and are the various control variables affecting Rh20 and its Q10 under long-term and short-term nitrogen addition conditions. β is estimated coefficients, β0 is the constant, and ε is the residual error. The soil environmental factors C/N, pH, LOC, EON, MN, and Cmic were used to estimate the response of Rh20 to long-term nitrogen fertilizer application; LOC, EON, MN, and Cmic to estimate the response of Rh20 to short-term nitrogen addition; C/N, pH, LOC, EON, MN, Cmic, and qmic to estimate the response of Q10 to long-term nitrogen fertilizer application; and LOC, EON, MN, Cmic, and qmic to estimate the response of Q10 to short-term nitrogen addition.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with significance at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Nitrogen Addition on Soil Rh20 and Its Q10

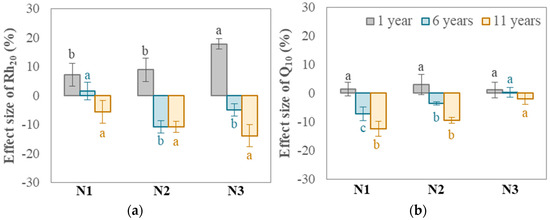

Long-term nitrogen fertilizer application: The direction of the effect of nitrogen fertilizer application in rice field systems on soil Rh is affected by the duration of continuous application (Figure 1). When the nitrogen fertilization treatment was maintained for only 1 year, the high nitrogen application treatment (N3) resulted in a significantly increased soil Rh20 compared to the treatment without nitrogen fertilizer (N0). When the nitrogen fertilizer application lasted for 6 years, the response of the soil Rh to differences in the nitrogen application level was not significant. When the nitrogen fertilizer application lasted for 11 years, the nitrogen application treatment reduced the soil Rh20 by 6% to 14% compared with the treatment without nitrogen fertilizer (N0), and the effect was significant when the nitrogen addition was greater than 200 kg ha−1 (N2 and N3 treatments).

Figure 1.

Effect sizes of Rh20 (a) and its Q10 (b) under long-term nitrogen fertilizer application conditions. Different lowercase letters indicate whether there exist significant differences in the comparison of effect sizes of Rh20 or Q10 under three diverse long-term nitrogen addition rates (three data points with identical duration are in the same comparison group), determined by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Letters are shown in the same color as in figure key to indicate each data point’s time property.

In addition, differences in the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application also produced different responses in the Q10 of soil Rh in rice field systems. When nitrogen fertilizer was applied for 6 years, the Q10 value decreased by 7% compared with the treatment without nitrogen fertilizer (N0); when nitrogen fertilizer was applied for 11 years, the Q10 value decreased by 12%. The Q10 of the 200 kg ha−1 annual nitrogen addition treatment (N2) reached a significant decrease of 10% after 11 years of nitrogen fertilizer application.

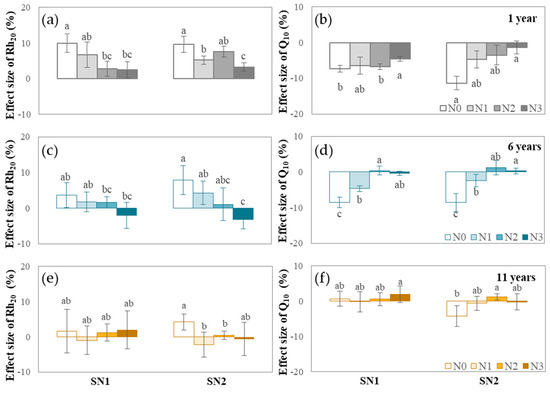

Short-term nitrogen addition: Short-term nitrogen addition increased the rate of soil Rh and reduced Q10 to a certain extent (Figure 2). Soil Rh20 and Q10 values responded more significantly to the short-term high-intensity nitrogen addition (SN2) condition than to the short-term low-intensity nitrogen addition (SN1) condition. Moreover, among the different long-term nitrogen fertilizer application treatments, short-term nitrogen addition had a more significant effect on the soil Rh20 and Q10 values of the soil in treatment without nitrogen fertilizer (Rh20 increased by 2–10% and the Q10 value decreased by 4–12%), while it had a relatively small effect on the soil Rh20 and Q10 values of the soil in the nitrogen application treatment, especially the higher nitrogen application treatment (Rh20 changed by −3–6% and the Q10 value changed by −7–2%, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect sizes of Rh20 and its Q10 in short-term nitrogen addition conditions: (a) soil Rh20 at the 1-year site; (b) Q10 of soil Rh at the 1-year site; (c) soil Rh20 at the 6-year site; (d) Q10 of soil Rh at the 6-year site; (e) soil Rh20 at the 11-year site; (f) Q10 of soil Rh at the 11-year site. Different lowercase letters indicate whether there exist significant differences in the comparison of effect sizes of Rh20 or Q10 under four diverse long-term and two diverse short-term nitrogen addition rates (eight data points with identical durations are in the same comparison group, regardless of their long- and/or short-term nitrogen addition rates), determined by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05).

In addition, the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application also significantly influenced the responses of soil Rh20 and Q10 values to short-term nitrogen addition. When the nitrogen fertilizer treatment lasted for 1 year, short-term nitrogen addition increased the soil Rh20 by 3–10% and reduced the Q10 value by 2~12% (Figure 2a,b). Soil Rh20 and Q10 values were sensitive to short-term nitrogen addition. Among them, the Rh20 and Q10 values of the soil in the long-term no-nitrogen application treatment condition (N0) and in the annual-average-nitrogen application condition of less than 200 kg ha−1 (N1) responded significantly to short-term nitrogen addition. As the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application increased, the soil originally treated with nitrogen fertilizer gradually became less responsive to short-term nitrogen addition. When the nitrogen fertilizer treatment lasted for 6 years, only the soil Rh20 and Q10 values of the no-nitrogen treatment (N0) showed a significant increase of 4–8% and a significant decrease of 8–9%, respectively, due to the short-term nitrogen addition. The soils with nitrogen treatments greater than 200 kg ha−1 (N2, N3) even showed the opposite response (Figure 2c,d). When the nitrogen fertilizer treatment lasted for 11 years (WX), short-term nitrogen addition had no significant effect on soil Rh20 or Q10 values in the fertilization treatment conditions (Figure 2e,f).

3.2. Response of Soil Rh20 and Its Q10 to the Rate and Duration of Nitrogen Addition

Nitrogen addition rate had a significant effect on the rate of soil Rh, but the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application affected the direction of the effect of nitrogen addition on soil Rh (Table 2). Under the conditions of only 1 year of nitrogen fertilizer application, the nitrogen addition rate was significantly positively correlated with soil Rh20; that is, the greater the nitrogen addition rate, the stronger the soil Rh. However, when the nitrogen fertilizer application treatment reached more than 6 years, the nitrogen addition rate and the soil Rh20 showed a significant negative correlation; that is, the nitrogen addition rate inhibited soil Rh. In addition, the rate of long-term nitrogen fertilizer application showed a positive correlation with Q10 values, but as the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application increased, the response of Q10 to the nitrogen addition rate gradually weakened (correlation in the 11-year condition was not significant). The effects of short-term nitrogen addition on soil Rh and its Q10 were significant only when nitrogen fertilizer was applied for 1 year; that is, short-term nitrogen addition promoted soil Rh20 and reduced the Q10 value (Table 2). As the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application increased, soil Rh and Q10 became less sensitive to short-term nitrogen addition.

Table 2.

Response of soil Rh20 and Q10 value to the rate and duration of nitrogen addition.

3.3. Response of Soil Rh20 and Its Q10 to the Soil Environmental Factors

Under long-term nitrogen fertilizer application conditions, soil C/N, pH, EON, and MN are the main factors affecting the rate of soil Rh; soil C/N and MN are also related to the Q10 of soil Rh (Table 3). Under the combined short-term nitrogen addition conditions, EON was the main factor affecting the rate of soil Rh, while the Q10 of soil Rh was mainly associated with soil MN and qmic.

Table 3.

Response of soil Rh20 and Q10 value to the soil environmental factors under different nitrogen addition conditions.

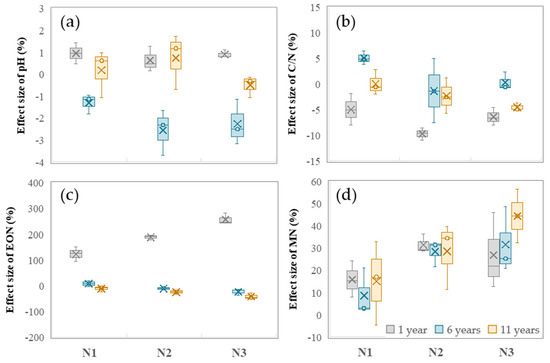

Long-term nitrogen fertilizer application significantly increased soil MN content, and the magnitude of the change became more significant with increasing nitrogen fertilizer application intensity and a longer treatment duration (Figure 3d). The EON content was increased by the nitrogen fertilizer application rate only in the 1-year planting condition, while it decreased with the increase in the application rate in the 6-year and 11-year planting conditions (Figure 3c). The soil C/N fluctuation caused by long-term nitrogen fertilizer application showed a downward trend in the 1-year condition and tended to be stable as the years of continuous nitrogen fertilizer application treatment were prolonged (Figure 3b). The pH value of rice field soil varied from −3% to 1% under long-term nitrogen fertilizer application and showed a decrease only in the 6-year condition, but it did not reach a significant level, and there was no significant difference between different nitrogen fertilizer application rates (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Response of soil pH (a), C/N (b), EON (c), and MN (d) to long-term nitrogen fertilizer application.

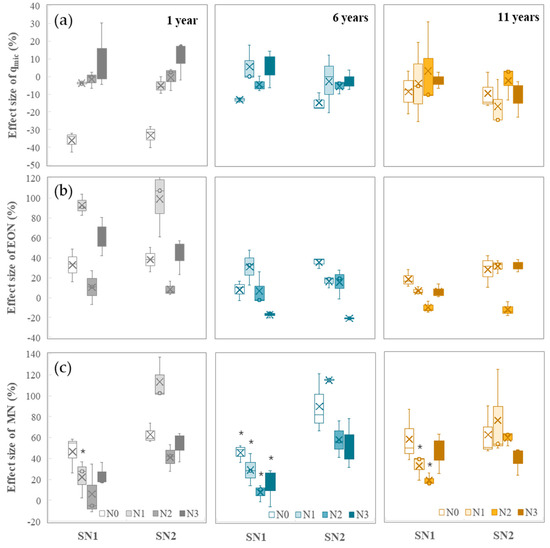

The response of soil qmic to short-term nitrogen addition was mainly affected by the nitrogen fertilizer application rate and the duration of treatment (Figure 4a). Short-term nitrogen addition had a tendency to reduce soil qmic, but there was no significant difference among the different short-term nitrogen addition rates. In the no-nitrogen fertilizer application condition, the reduction effect of short-term nitrogen addition on soil qmic was more significant. In addition, as the duration of nitrogen fertilizer application increased, the impact of short-term nitrogen addition on soil qmic gradually weakened, and the differences in soil background caused by long-term nitrogen fertilizer application also gradually narrowed.

Figure 4.

Response of soil qmic (a), EON (b), and MN (c) to short-term nitrogen addition. * The black-colored stars indicate whether there exist significant differences in the comparison of the effect size of qmic, EON, and MN under the same long-term nitrogen addition rates and different short-term nitrogen rates (two data points in the same comparison group have the same duration and long-term nitrogen rate, as well as different short-term nitrogen rates), determined by T test (p < 0.05). The absence of a star indicates that no significant differences exist in the given comparison group.

4. Discussion

4.1. Nitrogen Addition Altering Soil Environmental Factors and Soil Rh

In this study, under conditions of long-term nitrogen fertilizer application and short-term nitrogen addition, soil C/N, pH, EON, and MN all exhibited significant correlations with soil Rh rates (Table 3). Although in this study, all treatments involved only the application of chemical nitrogen fertilizers, both soil MN and EON (related to nitrogen addition) demonstrated a significant correlation with Rh in the regression analysis.

MN serves as a nutrient that can be directly absorbed and utilized by plants and microorganisms for growth. Theoretically, an increase in the MN content in the soil environment could promote the growth of soil microorganisms and their carbon decomposition activities [23,24,36]. However, in this study, MN and the rate of soil Rh show a significant negative correlation under long-term nitrogen addition conditions. Conversely, under short-term nitrogen addition conditions, a significant positive correlation is observed. Combined with the changes in the other soil properties (Figure 3), partially due to the possible direct inhibition of the respiration rate by mineral nitrogen in the soil [29,37], the increase in soil MN content caused by long-term nitrogen addition may change the microbial community or activity [16,18,28], the shifts of which then inhibit soil Rh in the presence of LOC and nutrients [36]. By contrast, short-term nitrogen addition increases soil Rh to a certain extent, and this increase is most evident in the non-fertilized treatment in the 1-year planting condition (Figure 2a). These findings show that when the native soil MN content is relatively low, nitrogen addition could stimulate carbon decomposition in the short term; however, this effect may not be significant under soil native conditions subjected to continuous nitrogen addition over multiple years. Therefore, it is evident that the behavioral feedback of microorganisms regarding carbon fixation or decomposition depends on the nutrient status of the soil [38].

On another note, under both long-term and short-term nitrogen addition conditions, the soil EON content exhibited a strong positive correlation with the soil Rh. Only in the one-year condition did the EON content increase significantly with the increase in both the long-term and short-term nitrogen addition rates. Regarding the increased EON in this part, it is highly probable that it stems from the decomposition of biomass detritus by microorganisms. The application of nitrogen fertilizers augments the amount of biomass detritus entering the soil, thus leading to an elevation in the EON content [25,36]. Conversely, in the 6-year and 11-year conditions, the EON content decreased in response to an increase in the long-term nitrogen addition rate yet exhibited no marked response to short-term nitrogen addition (Figure 3c). These findings indicate that the maintenance of soil EON content is, to a large extent, reliant on the addition of organic nitrogen [9], whereas the long-term application of chemical nitrogen fertilizer alone could result in the depletion of EON.

As relatively stable physical and chemical properties of soil, pH, and C/N did not show a significant response to nitrogen addition rates, even under long-term nitrogen fertilization conditions. Be that as it may, this study still finds that soil C/N and pH show a positive correlation with Rh (Table 3, Figure 3). Regarding soil pH, with urea serving as the main nitrogen fertilizer, both the nitrification process of nitrogen fertilizers and the uptake of NH4+-N by the rice plant are accompanied by the release of protons, thus leading to soil acidification and inhibiting microbial biomass and activity [18]. Therefore, the appropriateness of the nitrogen addition rate of chemical fertilizers (in line with crop growth) is crucial for determining the soil acidification rate. Long-term high-rate nitrogen addition is likely to result in a simultaneous decline in both soil pH and Rh [28].

When it comes to C/N, this study shows a downward trend in C/N with long-term nitrogen addition, especially when the addition rate reached more than 200 kg ha−1 (Figure 3). Although during one year of nitrogen addition, the decline in C/N is accompanied by an increase in the soil Rh rate, when extended to six continuous years or more, a depressing effect on the soil Rh rate is observed (Figure 3a,c), which indicates a positive correlation between the soil C/N and the rate of soil Rh (Table 3). Numerous studies suggest that a lower C/N condition is more favorable for soil Rh [7,20]. Nevertheless, the positive correlation between soil C/N and the respiration rate typically emerges under circumstances where the inherent soil properties are at a relatively high level, as exemplified by forest soils [35]. In this context, nitrogen supplementation or the addition of low-C/N substances could alleviate the competition for nitrogen between microorganisms and crops [7]. It is worth noting that, as the cropping systems in this study are relatively abundant in nitrogen, the soil C/N ranges from 9 to 13. The synchronous changes observed between C/N and the rate of soil Rh, to a certain extent, indicate that even when C/N increases, nitrogen is still abundant and does not constitute a nitrogen-limited state to limit the carbon decomposition by microorganisms [35,37]. In addition, as carbon serves as the substrate for soil Rh, its depletion could become a decisive factor influencing the Rh response [21,37]. However, in this study, although continuous multi-year cultivation and varying nitrogen application rates resulted in yield differences, the implementation of straw return did not lead to significant changes in soil SOC or LOC (Table 1). Therefore, it could be inferred that the inhibition of soil Rh caused by long-term nitrogen fertilizer application (exceeding 6 years) is unlikely to be attributable to the reduction in substrate availability.

4.2. Nitrogen Addition and Q10 of Soil Rh

In this study, soil MN showed a significant positive correlation with the Q10 of Rh under both long-term nitrogen fertilizer application and short-term nitrogen addition conditions. Under short-term nitrogen addition conditions, the positive effect of qmic on Q10 was also significant (Table 2), implying that nitrogen increased Rh’s Q10 through the increase in substrate availability and better specific microbial activity [25,39] under short-term nitrogen addition conditions. A previous study suggests that, in agricultural systems, the response of soil microbial communities to nitrogen addition enhances their activity in decomposing organic carbon under a warmer climate [39]. The fate or management pathway of carbon and nitrogen in biological residues is a key factor determining the sensitivity of soil Rh to nitrogen addition across ecosystems [7,21]. In this study, affected by the continuous return of straw back to the field, the contents of soil SOC and LOC remained relatively stable and sufficient across different nitrogen strategies (Table 1). Under these conditions, after 11 years of nitrogen addition, the effect of nitrogen on Rh’s Q10 is no longer statistically significant (Table 2). This is an interesting phenomenon, suggesting that for long-term rice-cultivation systems, nitrogen addition may weaken the impact of climate warming on SOC decomposition. Therefore, compared with the nitrogen addition rate, the addition duration seemed to contribute more to the Q10 of Rh.

In the one-year condition, the soil Rh’s Q10 responded significantly to short-term nitrogen addition (Table 2), but when the duration was extended to 6 and 11 years, short-term nitrogen addition did not significantly change Rh’s Q10. There is no doubt that the effect of short-term nitrogen addition on the dynamic behavior of microbial carbon decomposition plays a crucial role in determining the direction of Rh’s changes [7,25]. Yet, soil microbial biomass was not a key factor affecting Rh or its Q10 in this study (Table 3), and MN and qmic are positively correlated with Q10 under short-term nitrogen addition conditions. This shows that, for rice field soils with a C/N of around 10, the changes in mineral nitrogen brought about by short-term (14 days) nitrogen addition are not sufficient to significantly change the total biomass of the microbial community. Considering that Rh’s Q10 is mainly determined by specific microorganisms [24], the correlation between qmic and the Q10 of Rh could indicate that short-term nitrogen addition changes the response strategy of related functional bacteria to the intensity of carbon decomposition under variable temperature environments [16,35]. The correlation between microbial indicators and the Q10 of Rh was found only in the short-term nitrogen addition conditions and not in the long-term conditions (Figure 4a). It also means that, in a soil environment with relatively abundant total nitrogen, the effect of nitrogen addition on microbial carbon decomposition behavior and its sensitivity is not mainly reflected in microbial biomass. Instead, the structure of the microbial community might be the key factor influencing the carbon decomposition efficiency of relevant microorganisms, and this area is expected to become an important focus of future research.

4.3. Implications for Adjusting Nitrogen Addition Based on Soil Rh and Its Q10

In agroecosystems, the rate of nitrogen fertilizer application is a critical determinant of how nitrogen addition influences soil Rh and its Q10, a finding consistently supported by this study and numerous prior investigations [7,24]. As for the rice systems in the Taihu Lake Basin involved in the current study, when the annual nitrogen addition rate is set to greater than 200 kg ha−1, the inhibition of the soil Rh rate is more significant, and only when the annual addition rate is set to less than 200 kg ha−1 is the decrease in the soil Rh’s Q10 significant (Figure 1). Interestingly, from the perspective of nitrogen management, the annual nitrogen addition rate of approximately 200 kg ha−1 during rice season precisely aligns with the recommended nitrogen addition rate for rice fields in the Taihu Lake Basin in recent years, which aims to achieve green production. This indicates that an annual nitrogen application rate of 200 kg ha−1 represents an optimal strategy that maintains crop productivity while balancing nitrogen use efficiency with nitrogen emission control [30]. When carbon emissions reduction (or the prevention of emission increases) is integrated into agricultural production objectives, a nitrogen fertilizer application strategy tailored to soil properties and crop yield intensity could simultaneously mitigate both soil carbon decomposition via Rh pathways and Q10. Although short-term nitrogen addition may lead to an increase in the soil Rh rate, appropriate nitrogen addition rates and extended addition durations could effectively mitigate the response of soil Rh to such short-term nitrogen addition and enhance the stability of carbon decomposition by the soil Rh process. This indicates that, on a fixed field, long-term and stable nitrogen fertilizer application in rice cultivation would be conducive to reducing carbon emissions from soil carbon decomposition and mitigating temperature-induced fluctuations in decomposition rates, thereby promoting the development of a more stable soil organic carbon pool within agroecosystems.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that, in the rice system, as the duration of continuous nitrogen fertilizer application increases, the rate of soil Rh and its Q10 are initially promoted and then inhibited. A high nitrogen application rate could effectively inhibit soil Rh; however, it also keeps the Q10 value at a relatively high level. In the sample rice systems of our study, the inhibitory effect of nitrogen fertilizer application on soil Rh became evident after more than 6 years of continuous nitrogen fertilizer application. The decrease in C/N, pH, and EON and the increase in MN resulting from long-term nitrogen fertilizer application are the primary factors inhibiting soil Rh, while Q10 exhibits a more notable response to soil C/N and MN. Short-term (14 days) nitrogen addition could increase soil Rh and attenuate its Q10. In nitrogen-rich rice soils, although short-term nitrogen addition does not notably alter microbial biomass, it may reduce qmic as a result of the increased content of soil mineral nitrogen, thereby influencing the response strategies of related functional bacteria regarding carbon decomposition intensity in a fluctuating-temperature environment.

Based on the responses of soil Rh and its Q10 to the nitrogen addition rate and duration, this study reveals that appropriate nitrogen application strategy could gradually achieve balanced crop yields, suppress the soil carbon decomposition rate, and alleviate carbon pool fluctuations caused by global warming over a long period of time.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15112521/s1, Table S1: The rate of soil heterotrophic respiration (μmol h−1 g−1) under variable temperatures from 4 to 28 °C; Table S2: The Q10 value of soil heterotrophic respiration.

Author Contributions

Y.Y.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; H.C.: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation; J.T.: methodology, formal analysis, data interpretation; L.Y.: study design, data interpretation, supervision, funding acquisition; L.X.: study design, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project of China, grant number 2021YFD1700801.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hao Cheng was employed by the company Suzhou Haoguo Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd. Author Jie Tang was employed by the company Central-Southern Safety & Environment Technology Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Rh | Heterotrophic respiration |

| Rh20 | Heterotrophic respiration at 20 °C |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| LOC | Labile organic carbon |

| MN | Mineral nitrogen |

| EON | Extractable organic nitrogen |

| ETN | Extractable total nitrogen |

| C/N | Carbon/nitrogen ratio |

| Cmic | Microbial biomass carbon |

| qmic | Metabolic quotient of soil microbes |

| LN | Long-term nitrogen fertilizer application |

| SN | Short-term nitrogen addition |

References

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9575–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.L.; Sheng, Y.Q.; Xu, L.L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.X.; Deng, J.S. Carbon sequestration potential of paddy soil in China under the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. Engineering 2024, 26, 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Hedlund, K.; Jackson, L.E.; Kätterer, T.; Lugato, E.; Thomsen, I.K.; Jørgensen, H.B.; Söderström, B. What are the effects of agricultural management on soil organic carbon in boreo-temperate systems? Environ. Evid. 2015, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendig, I.; Guzman, A.; De La Cerda, G.; Esquivel, K.; Mayer, A.C.; Ponisio, L.; Bowles, T.M. Quantifying direct yield benefits of soil carbon increases from cover cropping. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Bradford, M.A.; Wood, S.A. Global meta-analysis of the relationship between soil organic matter and crop yields. Soil 2019, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Cui, Z.L.; Zhou, R.R.; Zhang, W.S.; Gao, Q.; Chen, Y.X.; Yue, S.C.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. Soil organic carbon thresholds control fertilizer effects on carbon accrual in croplands worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Pokharel, P.; Liu, L.X.; Qiao, J.B.; Wang, Y.Q.; An, S.S.; Chang, S.X. Global effects on soil respiration and its temperature sensitivity depend on nitrogen addition rate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 174, 108814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocci, K.S.; Lavallee, J.M.; Stewart, C.E.; Cotrufo, M.F. Soil organic carbon response to global environmental change depends on its distribution between mineral-associated and particulate organic matter: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.M.; Xu, Y.H.; He, Y.J.; Zhou, X.H.; Fan, J.L.; Yu, H.Y.; Ding, W.X. Nitrogen fertilization stimulated soil heterotrophic but not autotrophic respiration in cropland soils: A greater role of organic over inorganic fertilizer. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 116, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.L.; Zhao, R.F.; Yang, Y.; Meng, Q.F.; Ying, H.; Cassman, K.G.; Cong, W.F.; Tian, X.S.; He, K.; Wang, Y.C.; et al. A steady-state N balance approach for sustainable smallholder farming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2106576118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.W.; Xu, W.; Tang, A.H.; Liu, X.J. Inorganic nitrogen wet deposition in eastern China: Comparison of different land use-based monitoring sites in north and south regions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 27, 3205–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Han, H.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhong, M.X.; Hui, D.F.; Niu, S.L.; Wan, S.Q. Plant functional groups regulate soil respiration responses to nitrogen addition and mowing over a decade. Funct. Ecol. 2018, 32, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, P.; Starke, R.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Hess, N. Apparent temperature sensitivity of soil respiration can result from temperature driven changes in microbial biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.X.; Yu, H.Y.; Cai, Z.C.; Han, F.X.; Xu, Z.H. Responses of soil respiration to N fertilization in a loamy soil under maize cultivation. Geoderma 2010, 155, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.Y.; Liu, T.Q.; Ding, H.A.; Li, C.F.; Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Cao, C.G. The effects of straw returning and nitrogen fertilizer application on soil labile organic carbon fractions and carbon pool management index in a rice-wheat rotation system. Pedobiologia 2023, 101, 150913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Lu, X.K.; Yang, Y.F.; Hartley, I.P.; Zhang, W.; Mo, J.M.; Yu, G.R.; Zhou, J.Z.; Kuzyakov, Y. Long-term nitrogen addition modifies microbial composition and functions for slow carbon cycling and increased sequestration in tropical forest soil. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3267–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.Y.; Wang, W. Soil Respiration As A Key Belowground Process: Issues And Perspectives. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2007, 31, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.M.; Li, J.J.; Lan, Z.C.; Hu, S.J.; Bai, Y.F. Soil acidification exerts a greater control on soil respiration than soil nitrogen availability in grasslands subjected to long-term nitrogen enrichment. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Hua, K.K.; Zhan, L.C.; He, C.L.; Wang, D.Z.; Nagano, H.; Cheng, W.G.; Inubushi, K.; Guo, Z.B. Effect of soil acidification on temperature sensitivity of soil respiration. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Marschner, P. Soil respiration, microbial biomass and nutrient availability in soil after repeated addition of low and high C/N plant residues. Biol. Fert. Soils 2016, 52, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Inagaki, Y.; Toyota, K.; Kosaki, T.; Funakawa, S. Substrate-induced respiration responses to nitrogen and/or phosphorus additions in soils from different climatic and land use conditions. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2017, 83, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Hyun, J.; Michelsen, A.; Kwon, E.E.; Jung, J.Y. Key determinants of soil labile nitrogen changes under climate change in the Arctic: A meta-analysis of the responses of soil labile nitrogen pools to experimental warming and snow addition. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 153066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.X.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Liao, C.; Li, Q.X.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F. Microbial community mediated response of organic carbon mineralization to labile carbon and nitrogen addition in topsoil and subsoil. Biogeochemistry 2016, 128, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.B.; Liu, C.A.; Hua, K.K.; Wang, D.Z.; Wu, P.P.; Wan, S.X.; He, C.L.; Zhan, L.C.; Wu, J. Changing soil available substrate primarily caused by fertilization management contributed more to soil respiration temperature sensitivity than microbial community thermal adaptation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.Y.; Li, J.W.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.S.; Mayes, M.A.; Dzantor, K.E.; Hui, D.F.; Luo, Y.Q. Soil extracellular enzyme activities, soil carbon and nitrogen storage under nitrogen fertilization: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 101, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Zhang, B.C.; Lu, M.; Luo, Y.Q.; Liu, L.L.; Li, B. Different responses of soil respiration and its components to nitrogen addition among biomes: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.P.; Jin, W.Y.; Shao, J.J.; He, Y.H.; Zhang, G.D.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.H. Different response patterns of soil respiration to a nitrogen addition gradient in four types of land use on an alluvial island in China. Ecosystems 2017, 20, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, A.J.; Du, E.Z.; Shen, H.H.; Xu, L.C.; Zhao, M.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Fang, J.Y. High-level nitrogen additions accelerate soil respiration reduction over time in a boreal forest. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, P.K.; Li, L.; Zhao, M.N.; Yan, P.S.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, S.Y.; Zhao, Q.H. Soil respiration and carbon sequestration response to short-term fertilization in wheat-maize cropping system in the North China Plain. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 251, 106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, W.; Schwenke, G.; Yan, T.M.; Liu, D.L. Optimizing N fertilizer rates sustained rice yields, improved N use efficiency, and decreased N losses via runoff from rice-wheat cropping systems. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 324, 107724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Tang, J.; Jiang, L.F.; Li, B.; Chen, J.K.; Fang, C.M. Evaluating the impacts of incubation procedures on estimated Q10 values of soil respiration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2282–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.R.; Islam, K.R.; Stine, M.A.; Gruver, J.B.; Samson-Liebig, S.E. Estimating active carbon for soil quality assessment: A simplified method for laboratory and field use. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2003, 18, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Pei, J.M.; Pendall, E.; Fang, C.M.; Nie, M. Spatial heterogeneity of temperature sensitivity of soil respiration: A global analysis of field observations. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 141, 107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Chodak, M. Microbial respiration per unit biomass increases with carbon-to-nutrient ratios in forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.H.; Zhou, X.H.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, L.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Liu, R.Q.; Du, Z.G.; Zhou, G.Y.; Shao, J.J.; Ding, J.X.; et al. Apparent thermal acclimation of soil heterotrophic respiration mainly mediated by substrate availability. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 29, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, K.S.; Craine, J.M.; Fierer, N. Nitrogen fertilization inhibits soil microbial respiration regardless of the form of nitrogen applied. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2336–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vain, A.C.; Rakotondrazafy, N.; Razanamalala, K.; Trap, J.; Marsden, C.; Blanchart, E.; Bernard, L. The fate of primed soil carbon between biomass immobilization and respiration is controlled by nutrient availability. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2021, 105, 103332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Sandino, T.; García-Palacios, P.; Maestre, F.T.; Plaza, C.; Guirado, E.; Singh, B.K.; Wang, J.T.; Cano-Díaz, C.; Eisenhauer, N.; Gallardo, A.; et al. The soil microbiome governs the response of microbial respiration to warming across the globe. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).