Abstract

Soil salinization threatens soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration. Although microbial necromass carbon (MNC) is crucial for SOC formation and stability, how biochar affects MNC in saline–alkaline soils remains unclear. This study assessed the impact of biochar amendment (0, 10, 20, and 30 t ha−1) on SOC and MNC dynamics in saline–alkaline soils cultivated with Arundo donax cv. Lvzhou No. 1 across tillering, jointing, and maturity stages. Biochar amendment significantly enhanced SOC and the soil C/N ratio, with the highest dose (30 t ha−1) raising SOC by 47.21% at jointing and 34.64% at maturity. Biochar significantly increased MNC at all growth stages, with increases ranging from 22.74% to 30.81%. From the jointing to the maturity stage, SOC exhibited a decline (20.03 to 27.77%), in contrast to the minimal change in MNC (–6.37% to 9.80%). This divergent trend consequently led to a peak in the MNC/SOC ratio at maturity. It directly demonstrates the relative stability of MNC and indicates its role as a persistent carbon reservoir within the topsoil. Biochar also elevated soil pH and nutrient availability, which reshaped microbial community structure and enhanced bacterial diversity. Partial least squares path modeling revealed that biochar facilitates MNC accumulation directly and indirectly by modifying soil chemical properties and thereby enhancing microbial diversity. These findings show that biochar enhances stable SOC storage in saline–alkaline soils primarily through the formation and stabilization of microbial necromass, thus revealing its potential for climate change mitigation.

1. Introduction

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is vital for soil health and ecosystem functioning [1,2], and its dynamics significantly influence atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations [3,4]. The IPCC AR6 emphasizes that while climate warming risks turning soils into a carbon source, improved management can enhance their sink capacity [5]. In China, saline–alkaline land accounts for 10.1% of the world’s total [6], covering an area of 9.9 × 107 ha [7]. Stabilizing SOC in these stressful environments is particularly challenging. Elevated salinity suppresses microbial activity and biomass [8] and disrupts soil aggregation [9], thereby reducing SOC stocks both by limiting the production of microbial-derived carbon and by accelerating the decomposition of previously protected organic matter [10]. This contributes to a global carbon loss of approximately 3.47 t C ha−1 within the saline–alkaline topsoil [11]. Stabilizing SOC in these soils is therefore both challenging and urgent.

Long-term carbon sequestration in saline–alkaline soils is closely linked to microbial necromass carbon (MNC). Derived from microbial metabolites and cellular remains, MNC plays a pivotal role in the formation and stabilization of SOC [12]. Through association with soil minerals and occlusion within aggregates, these residues become physically protected from microbial and enzymatic decomposition [13], thereby persisting long-term in the soil [14]. MNC can constitute a substantial portion of SOC (often 30–60%) [15] and serves as a robust indicator of SOC stability and turnover [16].

A promising strategy for reclaiming these degraded soils involves the combined application of biochar with salt-tolerant plant species. Arundo donax cv. Lvzhou No. 1 (Lvzhou No. 1), a perennial grass recognized for its vigorous root system, rapid growth, high biomass yield, and broad ecological adaptability [17,18,19], making it an ideal candidate for phytoremediation and carbon sequestration in saline–alkaline environments. Biochar (BC), a carbon-rich material produced from biomass pyrolysis, has attracted attention for its potential in carbon sequestration and improving soil properties in saline–alkaline environments, owing to its high carbon content, porosity, and strong sorption capacity [20,21,22,23]. However, the influence of BC on soil properties is highly contingent upon feedstock source and pyrolysis parameter [24,25,26]. According to a worldwide meta-analysis, SOC content can be markedly increased through biochar application [27]. The carbon sequestration effect of biochar stems not only from the incorporation of its inherent carbon but is also closely tied to its regulation of key processes within the soil carbon cycle. A complex interaction exists between biochar and MNC. Biochar creates a suitable habitat for microorganisms and supplies a rich source of organic matter, directly or indirectly influencing microbial growth, mortality, community composition and diversity. These changes influence MNC formation by modulating the dynamics of the microbial carbon pump [28,29]. Shifts in microbial community composition further affect the decomposition of SOC and its fractions, thereby altering the turnover and stability of both SOC and MNC [29,30].

Although biochar is known to influence soil carbon dynamics, a critical knowledge gap persists regarding its specific effect on the dynamics and mechanisms of MNC formation in saline–alkaline soils. The complex interactions between biochar, the soil microbial community, and the microbial carbon pump under such stressful conditions are not yet fully elucidated [31,32]. This study therefore aims to: (i) assess the effects of biochar application on SOC and MNC dynamics in saline–alkaline soils, (ii) quantify MNC accumulation and its contribution to SOC, and (iii) elucidate how biochar reshapes microbial communities and drives MNC dynamics. Thus, we tested the following two hypotheses: (i) Biochar amendment enhances MNC accumulation in saline–alkaline soils, with a more pronounced effect on bacterial necromass carbon (BNC) than on fungal necromass carbon (FNC). (ii) Biochar application modifies microbial community structure and diversity, which in turn regulates the microbial carbon pump and facilitates MNC formation. The findings are expected to elucidate the mechanisms by which biochar enhances organic carbon sequestration in saline–alkaline soils, providing a scientific foundation for land improvement strategies and agricultural carbon neutrality initiatives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

The study was conducted at a coastal forest farm in Dafeng District, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province, China (120°46′58″ E, 33°3′59″ N). This region experiences a humid monsoon climate, transitional between subtropical and warm–temperate zones. It is characterized by cold, dry, and frost–prone winters, contrasted with warm, rainy summers influenced by maritime air masses. The mean annual temperature is 14.1 °C, ranging from 0.8 °C in January to 27 °C in July. Average annual precipitation reaches 1068 mm, predominantly from June to September. Furthermore, the area receives about 2239 h of sunshine yearly, accounting for 51% of the possible total. The initial topsoil properties (0–10 cm) prior to biochar amendment were as follows: SOC of 8.23 g kg−1, soil total nitrogen of 0.13 g kg−1, pH (H2O) of 8.5, Electrical Conductivity (EC) value of 2.41 mS cm−1, and bulk density of 1.23 g cm−3.

2.2. Experimental Design

In April 2023, Arundo donax cv. Lvzhou No. 1 was planted at the experimental site. Three main plots (4 m × 10.5 m) were established in a randomized block design, each with four biochar treatments and three replicates, resulting in 12 experimental units (0.5 m × 4 m). Seedlings of Lvzhou No. 1 were planted at 80 cm × 30 cm spacing. The cold winter conditions caused aboveground die-back and variable rhizome survival in Lvzhou No. 1. Therefore, to ensure uniform plant density and a consistent starting point for all plots at the beginning of the 2024 growing season, all plots were uniformly replanted in April 2024.

Biochar was produced from rice husks by pyrolysis at 500 °C for 2 h under oxygen-limited conditions (pH: 8.5; carbon content: 32.75%; hydrogen content: 1.36; nitrogen content: 0.39%; moisture content: 4.57%; ash content: 56.61%; purchased from Henan Housen Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China). Based on the baseline topsoil organic carbon (0–10 cm; 10 t·ha−1), four biochar rates were applied: CK (0 t·ha−1), B1 (10 t·ha−1), B2 (20 t·ha−1) and B3 (30 t·ha−1). Before planting in 2023, the topsoil (0–10 cm) was rototilled, and biochar was thoroughly mixed into the soil to ensure uniform distribution.

Soil samples were collected at three growth stages of Lvzhou No. 1: tillering (July 2024), jointing (August 2024), and maturity (October 2024). At each stage, three cores were randomly collected from each plot and combined into a single composite sample. These composite samples were sieved (2 mm) and divided into three subsamples: one stored at –80 °C for microbial high-throughput sequencing, one at –20 °C for soil available nutrient analysis, and one air-dried for amino sugar quantification and basic physicochemical assays.

2.3. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.3.1. Soil Chemical Properties Analysis

Soil pH (H2O) was measured in a 2.5:1 (w/v) suspension using a pH electrode (PHSJ–3F, Inesa Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using an elemental analyzer (Elementar vario EL III, Langenselbold, Germany). Ammonium–nitrogen (NH4+–N) was determined by the indophenol blue method and nitrate–nitrogen (NO3−–N) was determined via UV spectrophotometry (759S, LengGuang Technology, Shanghai, China) [33]. SOC was measured by the external heating potassium dichromate oxidation method [34]. The ratio of organic carbon to total nitrogen (C/N) was calculated by dividing SOC by TN.

2.3.2. Soil Biological Properties Analysis

Microbial Necromass Carbon

Amino sugars (AS), including glucosamine (GluN), mannosamine (ManN), galactosamine (GalN), and muramic acid (MurA), are employed as biomarkers to quantify microbial necromass [35,36]. Soil AS were analyzed following the protocol of Zhang and Amelung [37]. Soil samples were hydrolyzed and amino sugars were derivatized to aldononitrile derivatives, with myo-inositol and N-methylglucosamine used as internal standards. Derivatives were separated by gas chromatography (Agilent 6890A) with FID using a DB-1 column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm). MNC was calculated according to the following formulas [38].

FNC was calculated using the following formula:

BNC was calculated using the following formula:

MNC was calculated using the following formula:

Microbial Community Composition

Total soil DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA). Amplicon libraries were prepared and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform; raw reads were quality-filtered and merged, OTUs were clustered at 97% similarity, chimeras removed, and taxonomic assignment performed with RDP Classifier (70% confidence). For alpha diversity comparisons, samples were rarefied to 20,000 reads; Good’s coverage averaged 99.09%. Phylum-level composition was summarized per sample.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the effects of biochar amendment on soil physicochemical properties, amino sugar contents, and microbial alpha diversity indices. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Duncan’s multiple range test and the least significant difference (LSD) test, with statistical significance defined at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). Data visualization and additional statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.5.1, https://www.r–project.org) [39]. Linear regression analysis was fitted using the lm() function to examine the relationship between microbial alpha diversity (predictor) and MNC (response). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated using the psych package [40] to assess associations among soil physicochemical properties and microbial community characteristic indicators. Mantel tests were conducted using the linkET package [41] to evaluate the relationship between MNC and soil properties. Partial least squares path modeling (PLS–PM) was performed using the plspm package [42] in R to investigate the direct and indirect pathways by which soil physicochemical properties, microbial community composition, and microbial diversity influence MNC.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Chemical Properties

ANOVA revealed no significant changes in nitrate–nitrogen (NO3−–N) or total nitrogen (TN) following biochar amendment (p > 0.05). However, ammonium–nitrogen (NH4+–N) and soil pH increased significantly at the jointing stage (p < 0.05). Available nitrogen fractions exhibited dynamic changes throughout plant development. NH4+–N contents reached their maximum at the maturity stage, whereas NO3−–N contents were highest at the tillering stage (Table S1).

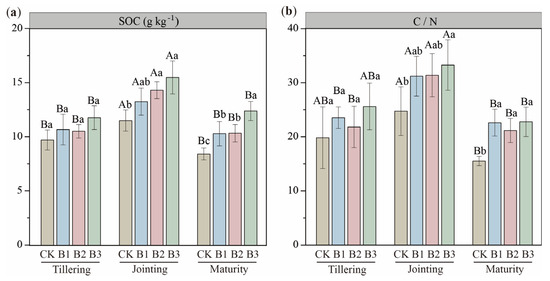

Biochar amendment significantly enhanced SOC content, with the most substantial increase observed under the B3 treatment, which elevated SOC by up to 47.21% at the maturity stage (Figure 1a). All biochar treatments significantly increased SOC at the jointing and maturity stages (p < 0.05), demonstrating a clear dose-dependent effect. Similarly, the soil C/N ratio was significantly increased by biochar addition, with the B3 treatment increasing the C/N ratio by 34.35% and 46.65% at the jointing and maturity stages, respectively (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Soil organic carbon (SOC) content and (b) the ratio of SOC to total nitrogen (C/N) in biochar-added soil during the three growth stages. CK: no biochar; B1: 10 t·ha−1 biochar; B2: 20 t·ha−1 biochar; B3: 30 t·ha−1 biochar. Different uppercase letters represent significant differences between the same treatments at different growth stages (p < 0.05), and different lowercase letters represent significant differences between different treatments at the same growth stage (p < 0.05). The error bars are used to represent the SD, n = 3.

3.2. Soil Microbial Necromass Carbon Contents

The contents of four amino sugars at different biochar application rates during the growth of Lvzhou No. 1 are shown in Figure S1. Biochar addition significantly increased the concentrations of GluN and MurA at the jointing stage and significantly reduced the concentrations of ManN and GalN at the tillering stage.

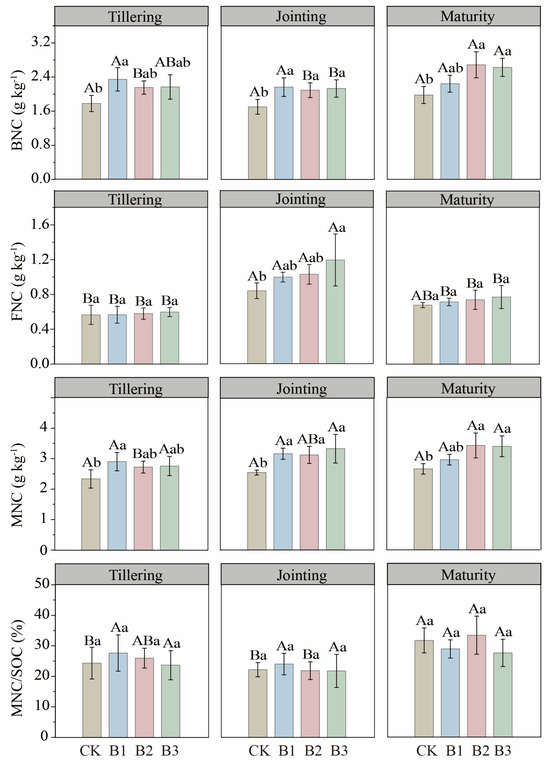

The FNC contents, BNC contents, MNC contents and the MNC/SOC ratios, calculated from amino sugar data, are shown in Figure 2. The high-dose biochar treatment (B3) consistently enhanced both BNC (by over 30%) and MNC (by over 25%) at the jointing and maturity stages compared to CK. In contrast, FNC was less responsive, showing a significant increase (42.22%) only under the B3 treatment at the jointing stage (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bacterial necromass carbon (BNC), fungal necromass carbon (FNC), total microbial necromass carbon (MNC), and the contribution of microbial necromass carbon to soil organic carbon (MNC/SOC) in biochar–added soil across three growth stages. CK: no biochar; B1: 10 t·ha−1 biochar; B2: 20 t·ha−1 biochar; B3: 30 t·ha−1 biochar. Different uppercase letters represent significant differences among growth stages within the same treatment (p < 0.05), and different lowercase letters represent significant differences among treatments within the same growth stage (p < 0.05). The error bars are used to represent the SD, n = 3.

Despite increases in MNC pools, the MNC/SOC ratio did not change significantly with treatment. Ratios of BNC/SOC and FNC/SOC were likewise stable across stages, and BNC remained consistently higher than FNC. Biochar application also did not significantly affect the BNC/SOC ratio. The only notable ratio change was a 22.99% reduction in FNC/BNC under B1 at tillering (p < 0.05); FNC/BNC reached its overall maximum at jointing (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Contribution of bacterial and fungal necromass carbon to soil organic carbon (BNC/SOC and FNC/SOC), and the ratio of fungal to bacterial necromass carbon (FNC/BNC) in biochar-amended soils across three growth stages. CK: no biochar; B1: 10 t·ha−1 biochar; B2: 20 t·ha−1 biochar; B3: 30 t·ha−1 biochar. Different uppercase letters represent significant differences among growth stages within the same treatment (p < 0.05), and different lowercase letters represent significant differences among treatments within the same growth stage (p < 0.05). The error bars are used to represent the SD, n = 3.

3.3. Soil Microbial Community Composition and Alpha Diversity

Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, and Actinobacteriota were the dominant bacterial phyla (relative abundance > 10%) with relative abundances of 18.58 to 33.23%, 13.26 to 26.81%, and 11.87 to 24.58% across all treatments, respectively. Ascomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Basidiomycota were the dominant fungal phyla (relative abundance > 1%), with relative abundances of 65.75 to 81.83%, 3.68 to 14.05%, and 2.03 to 15.17%, respectively. Biochar application increased the relative abundance of the Proteobacteria phylum, while decreasing that of the Acidobacteria phylum and the Chloroflexi phylum. Under biochar addition treatment, the relative abundance of the Ascomycota phylum was reduced by, whereas that of Mortierellomycota phylum was increased (Figure S2).

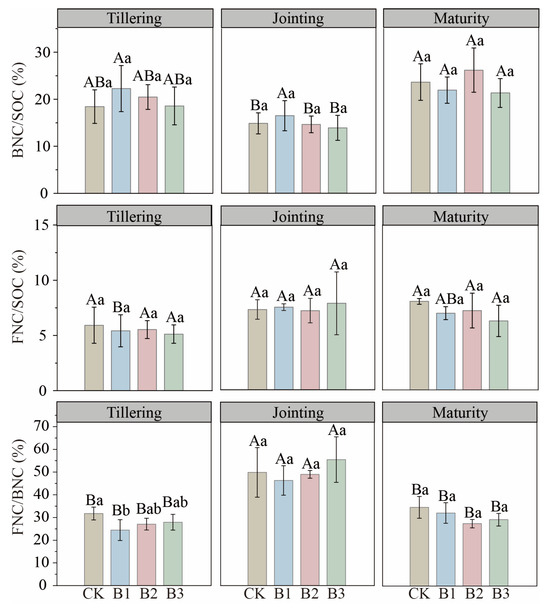

As shown in Figure 4, biochar treatments significantly enhanced bacterial alpha-diversity. Despite an overall decline in bacterial richness (ACE, Chao1) and diversity (Shannon) by maturity, all biochar treatments (B1–B3) consistently outperformed CK, with B1 and B3 showing the greatest effects at early and late stages, respectively. Conversely, fungal richness and diversity remained unaffected by biochar addition across all stages.

Figure 4.

Richness (ACE and Chao 1) and diversity (Shannon and Simpson) indices of bacterial (a–d) and fungal (e–h) species in soil with different biochar treatments across three growth stages. CK: no biochar; B1: 10 t·ha−1 biochar; B2: 20 t·ha−1 biochar; B3: 30 t·ha−1 biochar. Different uppercase letters represent significant differences among growth stages within the same treatment (p < 0.05), and different lowercase letters represent significant differences among treatments within the same growth stage (p < 0.05). The error bars are used to represent the SD, n = 3.

3.4. Relationships of Soil Properties, MNC and Microbial Community Characteristics

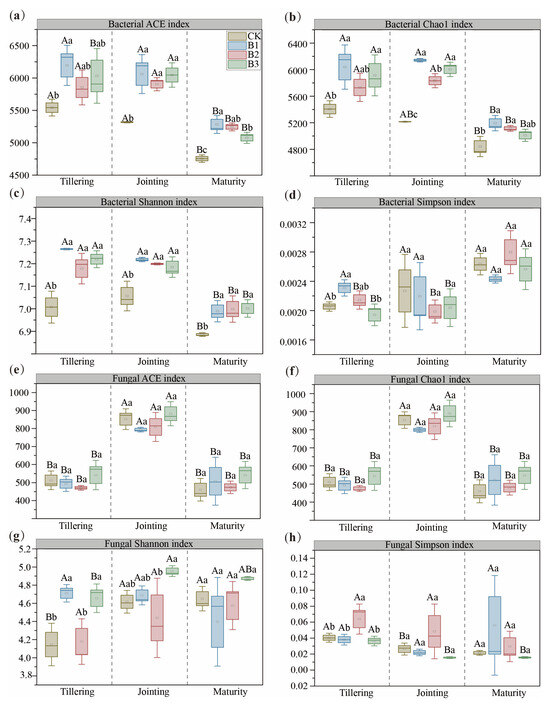

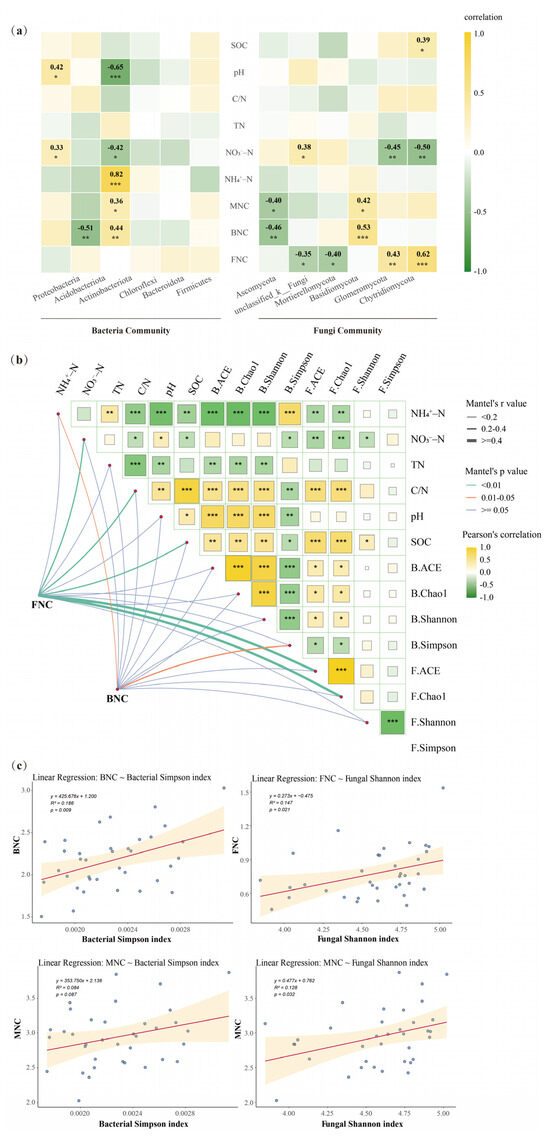

Pearson correlation analysis showed that the dominant communities at the bacterial phylum level (Acidobacteriota and Actinobacteriota) were significantly correlated with BNC, and the dominant community at the fungal phylum level (Mortierellomycota) was significantly correlated with FNC (Figure 5a). Soil properties, particularly pH and SOC, were strongly correlated with microbial community structure and diversity (Figure 5a,b). Mantel’s test analysis indicated that FNC was significantly associated with fungal richness (p < 0.01) and soil properties such as nitrate nitrogen, C/N and SOC (p < 0.05) (Figure 5b). Linear regression revealed significant positive relationships between bacterial diversity and BNC (p < 0.01), as well as between fungal diversity and both FNC and MNC (p < 0.05) (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

(a) The correlation between microbial community composition (the top six bacteria phylum and the top six fungi phylum by relative abundance) and both soil properties (SOC, pH, C/N, TN, NH4+–N, NO3−–N) and microbial necromass carbon (MNC, BNC, FNC). Color scale indicates correlation coefficients. The star suggested that there was a significant correlation between different parameters (*, ** and *** indicate the significance level at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001). (b) Correlations between soil properties (SOC, pH, C/N, TN, NH4+–N, NO3−–N) and microbial diversity (B.ACE: Bacterial ACE index; B.Chao1: Bacterial Chao1 index; B.Shannon: Bacterial Shannon index; B.Simpson: Bacterial Simpson index; F.ACE: Fungal ACE index; F.Chao1: Fungal Chao1 index; F.Shannon: Fungal Shannon index; F.Simpson: Fungal Simpson index). Color scale indicates correlation coefficients. The star suggested that there was a significant correlation between different parameters (*, ** and *** indicate the significance level at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001). Edge width corresponds to Mantel’s correlation coefficient, and edge color reflects Mantel’s significance. (c) Linear regressions between microbial necromass carbon (MNC, BNC, FNC) and microbial diversity indexes. The dots represent the observed data points, and the solid red line denotes the fitted regression line.

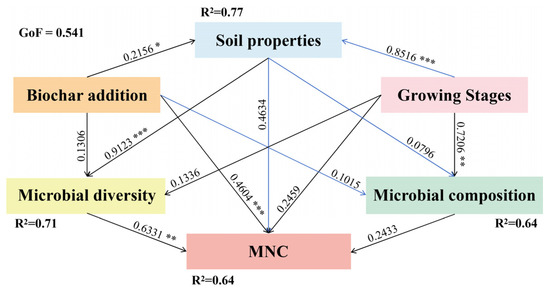

Partial least squares path modeling (PLS–PM) indicated that biochar addition positively influenced soil physicochemical properties (path coefficient = 0.2156, p < 0.05), which in turn had a strong positive impact on microbial diversity (path coefficient = 0.9123, p < 0.001). Microbial diversity subsequently positively influenced MNC accumulation (path coefficient = 0.6331, p < 0.01). A significant direct path from biochar to MNC was also identified (path coefficient = 0.4604, p < 0.001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS–PM) depicting causal relationships among soil properties, microbial community characteristics (microbial community composition and diversity), and MNC under biochar improvement during three growth stages. Soil properties include: pH, C/N, TN, NH4+–N, NO3−–N. Microbial composition includes the relative abundance of the top six bacterial and fungal phylum. Microbial diversity includes: the ACE, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices of bacterial and fungal. MNC includes: FNC, BNC and MNC. The black line represents positive influence, the blue line represents negative influence. the numbers above the lines: the path coefficients, GoF: goodness of fit, R2: the explained variance. Asterisks denote significance level. *, **, and ***, respectively, represent p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Biochar Addition on SOC and MNC

This study found that the addition of biochar significantly increased the SOC content in the topsoil, which aligns with the research of Wang et al. [43] and Chen et al. [29]. Biochar addition significantly enhanced SOC storage, primarily through promoting the accumulation and stabilization of microbial necromass (Figure 2). By gradually releasing nutrients and offering ecological niches, biochar facilitates microbial activity and increases the production of microbial-derived organic carbon (MNC), thereby strengthening this key pathway of SOC formation. In addition to these microbial mechanisms, the stabilization of SOC may be further enhanced by biochar-induced improvements in soil aggregation and the formation of organo-mineral complexes through its interactions with silicates, iron oxides, and aluminum oxides [44,45].

Research on biochar’s impact on MNC has yielded conflicting results. Although some studies indicate a positive effect through stimulated microbial growth [46,47], others report a decline, which is attributed to factors like a dilution effect on microbial communities or increased nitrogen limitation leading to necromass reassimilation [48,49]. This suggests that the net effect is complex and context-dependent, varying with biochar type and soil environment. Our results demonstrate a significant increase in MNC following biochar addition. The increase is explained by a sequential causal pathway, quantitatively supported by Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM, Figure 6). The model demonstrates that biochar first enhanced soil physicochemical properties, primarily by elevating the C:N ratio and nutrient availability [50]. These improved soil conditions then functioned as a key driver, strongly promoting microbial diversity, which in turn served as the primary direct factor leading to MNC accumulation [51].

The accumulation of net MNC and its proportional contribution to SOC reflect the stability potential of microbial-derived carbon [50]. Existing studies present varying results. Sun et al. [52] observed a decrease in the proportional contribution of MNC to SOC under biochar treatment, attributing this to the negative priming effect and enhanced SOC stability. In contrast, Meng et al. [46] reported that low-concentration biochar reduced the contribution of MNC to SOC, whereas high-concentration biochar application had no significant impact. Our results were consistent with the latter scenario. Although biochar addition increased the net contents of BNC, FNC, and total MNC, it did not significantly alter their proportional contributions to SOC (Figure 2 and Figure S1). This may be attributed to the simultaneous increase in MNC and SOC contents induced by biochar, which helped maintain a dynamic balance between SOC accumulation and mineralization processes driven by microbial activity. Such a dynamic balance is critical for maintaining the long-term stability of the soil carbon pool.

4.2. Changes in MNC and Its Contribution to SOC During the Growth Stages

The surface SOC content increased at the jointing stage but decreased by maturity (Figure 1a), indicating an initial accumulation during the growing season, followed by leaching and downward migration later. However, BNC and MNC remained relatively stable across all three growth stages (Figure 2), showing no significant fluctuations. In addition, the ratios of BNC to SOC and MNC to SOC peaked during the maturity stage (Figure 2 and Figure 3). These findings suggested that MNC, as a stable carbon pool in surface soil, gradually accumulated and stabilized in the surface soil, contributing significantly to the maintenance of the SOC pool. The stability of MNC can be attributed to the entombing effect, which means that microbial residues become protected through association with soil minerals or within aggregates, rendering them resistant to decomposition [50]. In saline–alkaline soils where traditional SOC stabilization mechanisms are compromised, the microbial carbon pump effectively creates a stable carbon sink. This underscores MNC’s importance not just as an SOC component, but as the foundational core of carbon sequestration in degraded lands.

Global studies consistently show that FNC constitutes a larger portion of MNC than BNC [53]. This dominance, exemplified by FNC contributing 1.8–3.8 times more than BNC in grassland ecosystems [54], is primarily due to the slower decomposition of fungal cell walls, which enhances FNC’ persistence in soils [55]. In contrast, our study revealed that in saline–alkaline soils, BNC consistently exceeded FNC (Figure 3), establishing BNC as the dominant component of MNC. This finding is consistent with our initial hypothesis. It also aligns with the findings of Song et al. [56] in similar saline–alkaline environments. The observed discrepancy may result from the filtering effect of saline–alkalinity on microbial community composition, wherein fungi are more sensitive to salinity stress than bacteria [57,58]. This environmental selection promotes bacterial biomass and enhances the accumulation of bacterial-derived carbon. Consequently, the compositional and biomass differences between fungi and bacteria likely explain the reduced FNC relative to BNC in saline–alkaline soils.

The FNC/BNC ratio exhibited pronounced seasonal fluctuations during Lvzhou No. 1 growth (Figure 3). Compared with bacteria, fungi possess greater nutritional competitiveness and can utilize organic acid substrates secreted by roots to synthesize cell wall components and intracellular energy storage compounds, thereby sustaining growth and reproduction [59]. Therefore, during the jointing stage, the proportion of fungal biomass increases substantially, leading to a gradual rise in the FNC/BNC ratio. However, elevated extracellular enzyme activities during the growing season may also facilitate decomposition of relatively recalcitrant FNC. Owing to their competitive advantage under environmental stress, bacteria constitute a larger share of the microbial biomass during the non-growing season [60], thereby reducing the FNC/BNC ratio.

4.3. Effects of Biochar Addition on Microbial Community Characteristics and Its Correlation with Microbial Necromass Carbon

Biochar application restructured the microbial community (Figure S2), influenced by its inherent properties such as pH, pore structure, and mineral composition [61]. These properties collectively improved the soil environment by elevating pH, increasing SOC, and enhancing nutrient availability (Figure 1, Table S1), which in turn drove taxonomic shifts. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria increased, which can be attributed to their salt tolerance and copiotrophic lifestyle under the nutrient-enriched conditions created by biochar [62]. Concurrently, the abundance of Acidobacteria declined, a phylum known to prefer acidic and oligotrophic environments, likely due to the combined effects of increased soil pH and intensified competition from copiotrophic taxa under improved nutrient conditions. Biochar addition increased the relative abundance of the Mortierellomycota phylum, as organic compounds released from biochar provided energy sources that enhanced the competitiveness of saprophytic fungi [63]. However, bacteria within a phylum may follow divergent life-history strategies [64], and the differentiation of responses at the phylum level may be inappropriate [65]. Therefore, further investigation and verification at finer taxonomic levels are warranted.

In parallel with these structural changes, our study demonstrated that biochar amendment increased bacterial richness (ACE and Chao1 indices) and diversity (Shannon index) (Figure 4), a finding consistent with global meta-analysis [66]. This improvement may be attributed to the introduction of additional carbon and energy sources by biochar, which stimulates microbial growth and metabolic activity, thereby reducing the dominant influence of salinity on bacterial communities. Biochar may also selectively promote the growth of highly adaptable specialized microbial taxa, diminish the competitive advantage of certain dominant species, and facilitate the proliferation of previously rare species, collectively enhancing the habitat suitability for bacterial colonization. Furthermore, the porous structure of biochar provides microhabitats that shelter bacteria and expand ecological niche space, thereby increasing niche heterogeneity and promoting bacterial α–diversity [67]. Additionally, biochar improved broader soil physicochemical properties by enhancing permeability, water retention capacity, and nutrient availability in saline–alkaline soils, which collectively supported microbial community diversification [68]. In contrast, biochar amendment did not significantly affect fungal richness. This may be due to the sustained stimulation of saprophytic fungi, which boosts their competitiveness against pathogenic and symbiotic fungi, thereby maintaining overall fungal community stability [69].

These biochar-induced shifts in microbial community characteristics were critically linked to the accumulation of MNC. Significant correlations were observed between MNC and several dominant microbial phyla, including Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Ascomycota (Figure 5a). Microbial diversity was strongly correlated with MNC (Figure 5c). Partial least squares path modeling (PLS–PM, Figure 6) indicated that biochar promoted microbial diversity by altering soil physicochemical properties, thereby facilitating MNC accumulation. The significance of microbial diversity in regulating the MNC can be clearly identified, which is also consistent with the research of Yang et al. [70]. These findings supported the hypothesis that biochar modulates MNC dynamics principally by inducing shifts in microbial community characteristics.

The functional traits of key microbial taxa further explain this causal relationship. For instance, Actinobacteriota are enriched with carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes). They play a critical role in decomposing plant residues, thereby facilitating the transformation of plant-derived carbon into stable microbial necromass [71]. Proteobacteria and Ascomycota are r-strategists with rapid growth rates [72]. These taxa preferentially consume labile organic carbon, as well as proteins and lipids derived from microbial necromass [73]. Acidobacteriota are K-strategists with slow growth rates. They play important roles in degrading complex organic compounds such as hemicellulose and cellulose through the production of extracellular enzymes [74]. These distinct biochemical traits and life-history characteristics among microbial groups, which modulate the dynamics of necromass decomposition and accumulation in soil [75]. For example, according to the Y–A–S framework, A-strategists (resource acquisition) allocate resources to extracellular enzyme production to mobilize nutrients from complex substrates rather than to biomass accumulation, potentially reducing net necromass accrual [76]. Therefore, shifts in community composition toward resource-acquiring or degradative functional types can markedly influence MNC pools. Microbial diversity is usually positively correlated with microbial carbon use efficiency (CUE) [77], whereby higher CUE can increase carbon allocation to biomass and subsequently to necromass pools [78]. For instance, saprophytic bacteria, which prefer labile organic matter, allocate more carbon to growth rather than enzyme production. This strategy results in high CUE and rapid growth rates, thereby promoting the accumulation of MNC [79]. In addition, the process of microbial death may be influenced by the dynamics of microbial communities and interspecific interactions [80]. For example, intensified resource competition within communities may elevate starvation and mortality rates, elevating necromass formation and contributing to higher MNC pools [81].

This study provides important data and practical guidance for using biochar to improve saline–alkaline soils and promote sustainable agricultural development. However, this study has several limitations. The correlation observed between microbial community shifts and MNC accumulation requires deeper mechanistic investigation. In addition, while our data from a single growing season provide valuable initial insights, they remain inadequate for drawing definitive conclusions, particularly in a field context where inter-annual variability is significant. Given that the effects of biochar on soil are long-term, and both microbial community succession and MNC stabilization require longer timeframes, short-term observations may not fully capture the dynamics involved. Furthermore, this study focused solely on the topsoil layer. As leaching and redistribution of soil organic carbon are critical processes, the dynamics of carbon pools in deeper soil layers also deserve attention. Moreover, the practical scalability of biochar requires further systematic evaluation before large-scale implementation can be recommended, including its long-term economic viability, production capacity, and adaptability across diverse saline–alkaline environments.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that biochar amendment increased SOC and MNC in saline–alkaline soils. Despite seasonal fluctuations in surface SOC, MNC remained relatively stable and served as a key persistent reservoir, underscoring its critical role in long-term carbon sequestration under such stressed conditions. BNC consistently exceeded FNC, suggesting that fungi were more sensitive to saline–alkaline stress. Biochar addition increased bacterial richness and diversity, and these community shifts likely reconfigured microbially mediated carbon transformation pathways that promote MNC accumulation. In summary, our findings provide preliminary evidence positioning biochar as a promising tool for restoring degraded soils and enhancing carbon storage. By establishing an enhanced and stabilized carbon pool, this approach could offer a synergistic pathway to advance both soil restoration and the carbon neutrality goal in saline–alkaline regions. Further studies should extend to multiple growing seasons to verify the reliability of the results and the long-term effects of biochar, and also systematically assess its practical scalability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15112472/s1, Figure S1: Effects of biochar application on the contents of four amino sugars during three growth stages; Figure S2: Effects of biochar application on the relative abundance of microbial communities during three growth stages; Table S1: Effect of biochar addition on physicochemical properties during the three growth stages; Table S2: Significance tests of two–way ANOVA on the main and interactive effects of biochar addition (B) and growing stage (S) on soil physicochemical properties and microbial necromass carbon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.W., Z.G. and Z.M.; Methodology: Y.W., Y.G., H.Z. and R.W.; Validation: Y.G.; Formal Analysis: Y.W.; Investigation: R.W.; Resources: Z.G.; Data Curation: Y.G. and H.Z.; Writing—Original Draft: Y.W.; Writing—Review and Editing: Y.G., H.Z., R.W., Z.G. and Z.M.; Visualization: Y.W., H.Z. and R.W.; Supervision: Z.M.; Project Administration: Z.G.; Funding Acquisition: Z.G. and Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Jiangsu Provincial Innovation Research Program on Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality (BT2024012); the Jiangsu Forestry Science & Technology Innovation and Extension Project (Project No.: LYKJ [2022] 02); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171856).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all members of the Biodiversity and Ecological Conservation Research Group at Nanjing Forestry University for their support in sample collection, data analysis and insightful suggestions on experimental design and interpretation. We also wish to acknowledge the reviewers and editors for their insightful feedback, which substantially enhanced this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bünemann, E.K.; Bongiorno, G.; Bai, Z.; Creamer, R.E.; De Deyn, G.; De Goede, R.; Fleskens, L.; Geissen, V.; Kuyper, T.W.; Mäder, P.; et al. Soil Quality–A Critical Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xiong, S.; Chen, Y.; Cui, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z. Total Organic Carbon Content as an Early Warning Indicator of Soil Degradation. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhu, B.; Cheng, W. Decadally Cycling Soil Carbon Is More Sensitive to Warming than Faster-Cycling Soil Carbon. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 4602–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsia, A.; Moinet, A.; Vazquez, C.; Creamer, R.E.; Moinet, G.Y.K. The Challenge of Selecting an Appropriate Soil Organic Carbon Simulation Model: A Comprehensive Global Review and Validation Assessment. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 5760–5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Jia, X.; Zhao, C.; Shao, M. A Review of Saline-Alkali Soil Improvements in China: Efforts and Their Impacts on Soil Properties. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 317, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Feng, B.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, F.; Shen, C.; Ma, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Saline-Alkali Land Reclamation Boosts Topsoil Carbon Storage by Preferentially Accumulating Plant-Derived Carbon. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 2948–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, W.; Sun, M.; Shi, W.; Lun, J.; Zhou, B.; Hou, L.; Gao, Z. Decoupling Soil Community Structure, Functional Composition, and Nitrogen Metabolic Activity Driven by Salinity in Coastal Wetlands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 198, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.C.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhou, H.; Rahman, M.T.; Wang, D.Z.; Guo, X.S.; Li, L.J.; Peng, X.H. Long-Term Animal Manure Application Promoted Biological Binding Agents but Not Soil Aggregation in a Vertisol. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 180, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xie, W.; Yao, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Li, T. Abiotic and Biotic Factors Mediate the Decomposition of Crop Straw in Saline Farmland Soils. Geoderma 2025, 459, 117390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, K.M.; Rousk, J. Salt Effects on the Soil Microbial Decomposer Community and Their Role in Organic Carbon Cycling: A Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Song, X.; Zeng, H.; Wang, J. Soil Microbial Necromass Carbon in Forests: A Global Synthesis of Patterns and Controlling Factors. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 240237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, H.; Mao, Z.; Bao, X.; He, H.; Zhang, X.; Liang, C. Fungi Determine Increased Soil Organic Carbon More than Bacteria through Their Necromass Inputs in Conservation Tillage Croplands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 167, 108587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Ranalli, M.G.; Haddix, M.L.; Six, J.; Lugato, E. Soil Carbon Storage Informed by Particulate and Mineral-Associated Organic Matter. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Deng, L.; Feng, J.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Q.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Liu, Y. Climatic Seasonality Challenges the Stability of Microbial-Driven Deep Soil Carbon Accumulation across China. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 4430–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Fang, K.; Chen, L.; Feng, X.; Qin, S.; Kou, D.; He, H.; Liang, C.; Yang, Y. Depth-Dependent Drivers of Soil Microbial Necromass Carbon across Tibetan Alpine Grasslands. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Lin, X.S.; Lin, H.; Lin, D.M.; Yang, F.L.; Lin, Z. Advances on Juncao research and application. J. Fujian Agric. For. Univ. 2020, 49, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R.; Zhang, H.; Guo, T.; Liu, X.; Wu, B.; Ma, J. Tianshui Soil and Water Conservation Experimental Station. Preliminary Report on the Introduction Experiment of Four Species of Gramineae in Gullied Rolling Loess Area. Yellow River 2019, 41, 100–102+110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Xu, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Rao, J.; Yang, W.; Xu, Q. Preparation of Lvzhou No.1 Biomass Carbon-Based Shape-Stabilized Composite Phase Change Material and Their Thermal Properties. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 5991–6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Cowie, A.; Masiello, C.A.; Kammann, C.; Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Cayuela, M.L.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Whitman, T. Biochar in Climate Change Mitigation. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Bartocci, P.; Fantozzi, F.; Mašek, O.; Agblevor, F.A.; Wei, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Lu, X.; et al. Prospective Contributions of Biomass Pyrolysis to China’s 2050 Carbon Reduction and Renewable Energy Goals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Mavi, M.S.; Choudhary, O.P.; Gupta, N.; Singh, Y. Rice Straw Biochar Application to Soil Irrigated with Saline Water in a Cotton-Wheat System Improves Crop Performance and Soil Functionality in North-West India. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Singh, B.P.; Wang, H.; Jia, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Bibliometric Analysis of Biochar Research in 2021: A Critical Review for Development, Hotspots and Trend Directions. Biochar 2023, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.J.; Ok, Y.S.; Lehmann, J.; Chang, S.X. Recommendations for Stronger Biochar Research in Soil Biology and Fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar Physicochemical Properties: Pyrolysis Temperature and Feedstock Kind Effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, L.; Hu, Z.; Xue, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Griffiths, B.S.; Whalen, J.K.; Liu, M. Biochar Exerts Negative Effects on Soil Fauna across Multiple Trophic Levels in a Cultivated Acidic Soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cai, A.; Wu, D.; Liang, G.; Xiao, J.; Xu, M.; Colinet, G.; Zhang, W. Effects of Biochar Application on Crop Productivity, Soil Carbon Sequestration, and Global Warming Potential Controlled by Biochar C:N Ratio and Soil pH: A Global Meta-Analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cai, H.; Yuan, J.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Soil Organic Carbon Accumulation Mechanisms in Soil Amended with Straw and Biochar: Entombing Effect or Biochemical Protection? Biochar 2025, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, Z.; Weng, Z.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Y.; et al. Formation of Soil Organic Carbon Pool Is Regulated by the Structure of Dissolved Organic Matter and Microbial Carbon Pump Efficacy: A Decadal Study Comparing Different Carbon Management Strategies. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 5445–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Sun, K.; Yang, Y.; Xia, X.; Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Xing, B. Biochar’s Stability and Effect on the Content, Composition and Turnover of Soil Organic Carbon. Geoderma 2020, 364, 114184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y. Biochar Stability in Soil: Meta-analysis of Decomposition and Priming Effects. GCB Bioenergy 2016, 8, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, P.; Liu, F.D.; Xiao, H.; Dong, Y.C.; Sun, H.W. Research and Application Progress of Biochar in Amelioration of Saline-Alkali Soil. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 940–951. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, Y.; Chen, J.; Awais, M.; Abdulraheem, M.I.; Yusuff, M.A.; Geng, K.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Nitrate Nitrogen Quantification via Ultraviolet Absorbance: A Case Study in Agricultural and Horticultural Regions in Central China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An Examination of the Degtjareff Method for Determining Soil Organic Matter and a Proposed Modification of the Chromic Acid Titration Method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, R.G. Amino Sugars as Specific Indices for Fungal and Bacterial Residues in Soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hu, G.; Xie, H.; Yan, J.; Han, S.; He, H.; Zhang, X. Linkage of Microbial Residue Dynamics with Soil Organic Carbon Accumulation during Subtropical Forest Succession. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 114, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Amelung, W. Gas Chromatographic Determination of Muramic Acid, Glucosamine, Mannosamine, and Galactosamine in Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Amelung, W.; Lehmann, J.; Kästner, M. Quantitative Assessment of Microbial Necromass Contribution to Soil Organic Matter. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3578–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Revelle, W. R package, version 2.3.12; psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Huang, H. R Package, Version 0.0.7.4; linkET: Everything is Linkable. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=linkET (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Sanchez, G.; Trinchera, L.; Russolillo, G. R Package, Version 0.5.1; plspm: Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=plspm (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Joseph, S.; Flury, M.; Wang, X.; Tahery, S.; Li, B.; Shang, J. Stabilization of Organic Carbon in Top- and Subsoil by Biochar Application into Calcareous Farmland. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 168046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.U.; Jiang, F.; Guo, Z.; Peng, X. Does Biochar Application Improve Soil Aggregation? A Meta-Analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.P.; Cowie, A.L.; Smernik, R.J. Biochar Carbon Stability in a Clayey Soil as a Function of Feedstock and Pyrolysis Temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11770–11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; An, N.; Guan, S.; Dou, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, W.; Yue, J. Unraveling Mechanisms of Carbon Enrichment via Straw and Biochar Application to Enhance Soil Fertility and Improve Maize Yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 169, 127673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Song, D.; Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Distribution Characteristics of Microbial Residues within Aggregates of Fluvo-Aquic Soil under Biochar Application. Agronomy 2023, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, K.; Ren, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, B.; Gunina, A.; Aloufi, A.S.; Kuzyakov, Y. Biochar and Microplastics Affect Microbial Necromass Accumulation and CO2 and N2O Emissions from Soil. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 4, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Q.; Ma, R.; Xu, M.; Song, K.; Bian, R.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X. The Divergent Response of Fungal and Bacterial Necromass Carbon in Soil Aggregates under Biochar Amendment in Paddy Soil. Plant Soil 2025, 513, 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Schimel, J.P.; Jastrow, J.D. The Importance of Anabolism in Microbial Control over Soil Carbon Storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; Mo, F.; Han, J. Microbial Life-History Strategies and Particulate Organic Carbon Mediate Formation of Microbial Necromass Carbon and Stabilization in Response to Biochar Addition. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, X.; Bao, Z.; Gao, J.; Meng, J.; Han, X.; Lan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W. Responses of Microbial Necromass Carbon and Microbial Community Structure to Straw- and Straw-Derived Biochar in Brown Earth Soil of Northeast China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 967746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Chen, H.; Ma, Z.; Liang, G.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L.; Wanek, W.; Wu, L.; Ma, Q. Fungal Necromass Carbon Dominates Global Soil Organic Carbon Storage. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.P.; Wu, M.Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Pang, D.B.; Chen, L.; Li, X.B.; Chen, Y.L. Accumulation and influencing factors of soil microbial necromass carbon in different grassland types of Ningxia, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 9300–9313. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; He, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.; Six, J.; Cai, Z.; Barthel, M.; Zhang, J.; Necpalova, M.; Ma, Q.; et al. Distinct Responses of Soil Fungal and Bacterial Nitrate Immobilization to Land Conversion from Forest to Agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 134, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Razavi, B.; Chang, F.; Yu, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y. Bacterial Necromass as the Main Source of Organic Matter in Saline Soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhuge, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, X. Distinct Accumulation of Bacterial and Fungal Residues along a Salinity Gradient in Coastal Salt-Affected Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 108266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Tian, L.; Nasir, F.; Bahadur, A.; Batool, A.; Luo, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Tian, C. Response of Microbial Communities and Enzyme Activities to Amendments in Saline-Alkaline Soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 135, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, W.; Nottingham, A.T.; Xiao, D.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, H.; Xiao, J.; Duan, P.; Tang, T.; et al. Lithological Controls on Soil Aggregates and Minerals Regulate Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency and Necromass Stability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21186–21199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellado-Vázquez, P.G.; Lange, M.; Gleixner, G. Soil Microbial Communities and Their Carbon Assimilation Are Affected by Soil Properties and Season but Not by Plants Differing in Their Photosynthetic Pathways (C3 vs. C4). Biogeochemistry 2019, 142, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar Effects on Soil Biota–A Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Qian, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, H.; An, Y.; Qi, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Land Conversion to Agriculture Induces Taxonomic Homogenization of Soil Microbial Communities Globally. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Xiong, X.; Zhu, H.; Xu, H.; Leng, P.; Li, J.; Tang, C.; Xu, J. Association of Biochar Properties with Changes in Soil Bacterial, Fungal and Fauna Communities and Nutrient Cycling Processes. Biochar 2021, 3, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.W.G.; Dijkstra, P.; Finley, B.K.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Foley, M.M.; Hayer, M.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Koch, B.J.; Li, J.; Liu, X.J.A.; et al. Life History Strategies among Soil Bacteria—Dichotomy for Few, Continuum for Many. ISME J. 2023, 17, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Bradford, M.A.; Jackson, R.B. Toward an Ecological Classification of Soil Bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yi, F.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Fu, X.; Yao, Z.; Dai, Z.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Biochar Dose-Dependent Impacts on Soil Bacterial and Fungal Diversity across the Globe. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Xing, B. Effects and Mechanisms of Biochar-Microbe Interactions in Soil Improvement and Pollution Remediation: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, N.; Li, J.; Liang, X.; Yi, K.; Gu, Y.; Guo, X. Effects of Biochar Amendment and Organic Fertilizer on Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere Soil of Wheat in Yellow River Delta Saline-Alkaline Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1250453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Enders, A.; Rodrigues, J.L.M.; Hanley, K.L.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J.; Lehmann, J. Soil Fungal Taxonomic and Functional Community Composition as Affected by Biochar Properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 126, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gunina, A.; Chen, J.; Wang, B.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Liang, C.; An, S.; Chang, S.X.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Unfolding the Potential of Soil Microbial Community Diversity for Accumulation of Necromass Carbon at Large Scale. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Dolfing, J.; Guo, Z.; Chen, R.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Lin, X.; Feng, Y. Important Ecophysiological Roles of Non-Dominant Actinobacteria in Plant Residue Decomposition, Especially in Less Fertile Soils. Microbiome 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, P.; Lynch, L.; Xie, H.; Bao, X.; Liang, C. Tradeoffs among Microbial Life History Strategies Influence the Fate of Microbial Residues in Subtropical Forest Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 153, 108112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Yuan, H.; Chen, J.; Ge, T.; Xu, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. Bacterial Necromass Decomposition and Priming Effects in Paddy Soils Depend on Long-Term Fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 211, 109992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Wang, B.; Xue, Z.; Wang, Y.; An, S.; Chang, S.X. Deciphering Factors Driving Soil Microbial Life-History Strategies in Restored Grasslands. iMeta 2023, 2, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, F.; Beatty, B.; Park, M.; Adamczyk, S.; Adamczyk, B.; See, C.R.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Hobbie, S.E.; Kennedy, P.G. Microbial Community Attributes Supersede Plant and Soil Parameters in Predicting Fungal Necromass Decomposition Rates in a 12-Tree Species Common Garden Experiment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Martiny, J.B.H.; Brodie, E.L.; Martiny, A.C.; Treseder, K.K.; Allison, S.D. Defining Trait-Based Microbial Strategies with Consequences for Soil Carbon Cycling under Climate Change. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Pold, G.; Liu, X.-J.A.; Frey, S.D.; Melillo, J.M.; DeAngelis, K.M. Microbial Diversity Drives Carbon Use Efficiency in a Model Soil. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastida, F.; Eldridge, D.J.; García, C.; Kenny Png, G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Soil Microbial Diversity–Biomass Relationships Are Driven by Soil Carbon Content across Global Biomes. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.; Rousk, J. Microbial Growth and Carbon Use Efficiency in Soil: Links to Fungal-Bacterial Dominance, SOC-Quality and Stoichiometry. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 131, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenzind, T.; Mason-Jones, K.; Mansour, I.; Rillig, M.C.; Lehmann, J. Formation of Necromass-Derived Soil Organic Carbon Determined by Microbial Death Pathways. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Morrissey, E.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Qu, L.; Sang, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; et al. Integrating Microbial Community Properties, Biomass and Necromass to Predict Cropland Soil Organic Carbon. ISME Commun. 2023, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).