Abstract

The growing use of radiation technologies has increased the need for shielding materials that are lightweight, safe, and adaptable to complex geometries. While lead remains highly effective, its toxicity and weight limit its suitability, driving interest in alternative materials. The process of 3D printing enables the rapid fabrication of customized shielding geometries; however, only limited research has focused on 3D-printed polymer composites formulated specifically for mixed photon–neutron fields. In this study, we developed a series of 3D-printable ABS-based composites incorporating tungsten (W), bismuth oxide (Bi2O3), gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3), and boron nitride (BN). Composite filaments were produced using a controlled extrusion process, and all materials were 3D printed under identical conditions to enable consistent comparison across formulations. Photon attenuation at 120 kVp and neutron attenuation using a broad-spectrum Pu–Be source (activity 4.5 × 107 n/s), providing a mixed neutron field with a central flux of ~7 × 104 n·cm−2·s−1 (predominantly thermal with epithermal and fast components), were evaluated for both individual composite samples and layered (sandwich) configurations. Among single-material prints, the 30 wt% Bi2O3 composite achieved a mass attenuation coefficient of 2.30 cm2/g, approximately 68% of that of lead. Layered structures combining high-Z and neutron-absorbing fillers further improved performance, achieving up to ~95% attenuation of diagnostic X-rays and ~40% attenuation of neutrons. The developed materials provided a promising balance between 3D-printability and dual-field shielding effectiveness, highlighting their potential as lightweight, lead-free shielding components for diverse applications.

1. Introduction

Nuclear technology represents one of the most significant scientific achievements of the modern era, providing immense benefits across diverse sectors, including medical diagnostics, nuclear power generation, radiation processing, and advanced imaging technology [1,2,3,4]. However, the proliferation of these applications results in the inevitable production of harmful ionizing radiation, such as X-rays, gamma rays (photons), and neutrons [5,6,7,8]. Exposure to these high-energy radiations poses serious hazards to human health, potentially causing irreversible biological damage, including cancer induction, genetic mutations, brain malfunction, and digestive and other systemic complications [9,10,11,12,13]. Consequently, ensuring effective protection from radiation is essential to minimize occupational exposure and reduce environmental risks. The preferred method for achieving this safety objective is the implementation of effective shielding materials, mitigating exposure more reliably than relying solely on the limitations of time or distance from the source [14,15,16,17].

Historically, heavy metals like lead have served as the principal materials for photon shielding due to their high density and atomic number (Z), offering robust attenuation capacity against gamma rays and X-rays [18,19,20]. However, conventional lead-based shields pose several critical disadvantages, prompting an urgent need for alternatives. Lead is a heavy, toxic material linked to environmental contamination and severe health consequences, including neurological damage. Moreover, it causes recycling problems and is notably ineffective for shielding neutrons [21,22,23,24,25,26].

This demand for safer, non-toxic, lightweight, and high-efficiency radiation protection solutions has driven the investigation of polymer matrix composites (PMCs) as compelling alternatives [27,28]. Polymers offer numerous advantages over metallic or concrete shields, including excellent processing performance, resistance to corrosion, inherent flexibility, thermal stability, and low density, which is advantageous for mobile and aerospace applications. While polymers alone typically possess insufficient attenuation capacity for high-energy photons due to their low-Z composition, their performance can be radically transformed by incorporating suitable heavy metal fillers [29,30,31,32,33].

For photon (X-ray and gamma-ray) shielding, the focus has shifted toward high-atomic number (high-Z) elements such as Tungsten (W) and Bismuth (Bi) and their compounds, which are favored for their high density and effectiveness in promoting photoelectric absorption at low energies [29,32,34,35,36]. Various studies have demonstrated the viability of integrating these high-Z fillers into polymer matrices like epoxy resin, HDPE, or even highly temperature-resistant polyether ether ketone (PEEK) to achieve superior gamma attenuation comparable to or exceeding lead, without compromising mechanical stability [37,38,39].

Conversely, effective neutron shielding fundamentally relies on two distinct processes: fast neutron moderation and thermal neutron absorption. Hydrogen-rich polymers, particularly polyethylene (PE), serve as indispensable matrices for moderating fast neutrons via elastic scattering due to their high hydrogen concentration. Once slowed, thermal neutrons must be captured by isotopes possessing huge neutron absorption cross-sections [40,41]. Boron compounds, such as boron carbide (B4C) and boron nitride (BN), are traditionally employed, yielding low-energy secondary gamma rays [42,43]. However, gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3) is increasingly utilized, given that gadolinium (Gd) boasts significantly higher thermal neutron absorption cross-sections [44,45]. These materials form composites, such as Gd2O3/PE and BN/HDPE nanocomposites, which show enhanced thermal neutron absorption and mechanical properties [44,46].

The development of materials capable of robust mixed neutron–photon shielding is particularly complex, necessitating a careful combination of light elements (for moderation and absorption) and heavy elements (for photon and secondary gamma attenuation). A critical challenge persists in achieving the homogeneous dispersion of fillers with widely differing densities, often leading to phase segregation and reduced overall composite performance, especially when manufacturing materials for simultaneous dual-field protection. This complexity often mandates intricate layering or the design of hybrid core–shell nanoparticles to maximize efficacy [46,47,48,49].

The manufacturing technology itself has also become a focal point of innovation. Additive manufacturing (AM), commonly known as 3D printing, particularly fused deposition modeling (FDM), offers exceptional advantages for creating customized shields with complicated geometries that maximize material efficiency and minimize waste. FDM allows for rapid prototyping and the ability to control filler distribution or orientation layer-by-layer, addressing some limitations faced by traditional molding techniques. Consequently, many contemporary research efforts involve integrating high-Z elements (W, Bi) and neutron absorbers (B, Gd) within printable polymer matrices, including acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and PEEK, to produce custom, functional shielding accessories [50,51,52,53,54]. However, a significant gap remains in the comprehensive development of 3D-printable, lightweight, lead-free composites that reliably deliver high-efficiency performance across both neutron and high-energy photon spectra simultaneously [55,56,57,58,59].

Therefore, the main aim of this work was to develop and thoroughly characterize 3D-printable, lead-free, lightweight composite materials using an acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) matrix reinforced with a combination of boron nitride (BN), gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3), bismuth oxide (Bi2O3), and tungsten (W) fillers, specifically optimized for mixed neutron and photon radiation shielding applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Composite Formulations

Acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (MAGNUM™ 3453 ABS) ((C8H8·C4H6·C3H3N)n), selected as the matrix material due to its good processability and compatibility with extrusion-based 3D printing, was purchased from 3Devo (3Devo, Utrecht, The Netherlands). Functional fillers, including Bi2O3 (99.99%, ~300 nm), Gd2O3 (99.5%, <200 nm), W powder (99.9%, ≤300 nm), and BN (98%, <500 nm), were obtained from VI Halbleiter material GmbH (Laatzen, Germany). The key physical parameters of the raw materials and the corresponding composite formulations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composite formulations and their physical parameters.

Five material compositions were investigated: pure ABS as the reference material and four ABS-based composites containing BN, W, Gd2O3, and Bi2O3 at the respective loadings listed in Table 1. The selected filler contents were mainly chosen based on filament extrusion stability and FDM printability. Increasing the filler loading resulted in higher melt viscosity, brittle filament behavior, and unstable extrusion, as commonly reported for highly filled polymer composites in the literature review. Therefore, filler concentrations were limited to levels that allowed continuous filament production and reliable printing under identical conditions. Pure ABS was printed to provide a baseline for evaluating the influence of filler incorporation on printability, density, and radiation attenuation. Fillers represent both high-Z photon attenuators (Bi2O3, W, Gd2O3) and neutron-reactive materials (BN, Gd2O3), enabling a comparative assessment of their individual contributions to the shielding performance of the 3D-printed composites.

2.2. Preparation of Composite Filaments

Composite filaments were produced by dry-mixing ABS granules with the corresponding fillers for 15–20 min, followed by extrusion using a 3Devo Precision (3Devo, Utrecht, The Netherlands). The extruder was purged with DevoClean HDPE before each formulation to prevent cross-contamination.

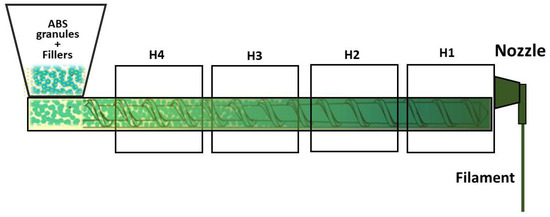

Filaments were extruded using the following settings: H4 = 220 °C, H3 = 230 °C, H2 = 235 °C, H1 = 240 °C, corresponding to the progression from the feeding zone (H4) to the nozzle (H1) as shown in Figure 1. The screw speed (3–5 rpm) controlled material throughput, while the fan speed (50%) regulated cooling of the extrudate. To improve filler dispersion, first pass filaments were shredded and re-extruded. Only the filament within 1.75 ± 0.05 mm was collected for subsequent 3D printing.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the extrusion setup used for composite filament fabrication.

2.3. 3D Printing of Samples

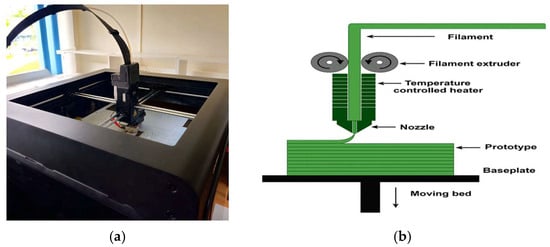

Samples were printed using a Zortrax M300 3D printer (Zortrax S.A., Olsztyn, Po-land) equipped with a 0.4 mm nozzle and operated in a fully enclosed chamber (Figure 2a). The printer uses the fused deposition modeling (FDM) technique, in which softened filament is extruded through a heated nozzle and deposited layer-by-layer to form the final structure (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Zortrax M300 3D printer used to fabricate ABS and composite samples. (b) Schematic representation of the FDM printing process.

A customized ABS printing profile was used for all materials. The nozzle temperature was set to 280 °C and the baseplate temperature to 90 °C, with a print speed of 30 mm/s and 5% cooling fan, a 0.29 mm layer height, and 100% infill to ensure consistent bulk density of attenuation measurements. A raft was used for every print to improve first layer adhesion, particularly for composites with increased viscosity.

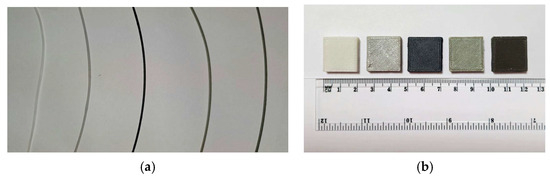

All composite formulations were successfully extruded into 1.75 mm filaments suit-able for FDM printing (Figure 3). However, it should be noted that the incorporation of functional fillers (BN, W, Gd2O3, and Bi2O3) into the ABS matrix presented several chal-lenges during filament extrusion and 3D printing, primarily related to flow characteristics and print density, consistent with difficulties reported in the literature for high filler con-tent composites [50,53,56].

Figure 3.

(a) Extruded ABS-based composite filaments; (b) 3D-printed samples (20 mm × 20 mm × 5 mm) of each material formulation. Materials are arranged from left to right as follows: ABS, ABS–5BN, ABS–30W, ABS–10Gd2O3, and ABS–30Bi2O3.

The physical density of all printed samples was measured to verify uniform bulk properties prior to attenuation testing using the Archimedes method. Each sample was weighed in air and then submerged in distilled water. The values were then compared with theoretical densities to evaluate printing accuracy and material distribution consistency.

—The sample’s mass in air;

—The sample’s mass in distilled water;

= 1.0 g/cm3— the density of the distilled water.

2.4. Mechanical Tests

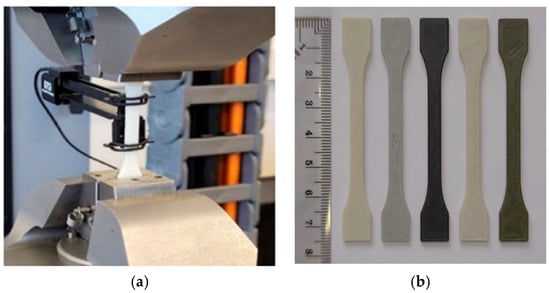

Dog-bone-shaped tensile specimens were 3D printed in accordance with ISO 527-2 [60] for the determination of the tensile behavior of plastics (Figure 4b). Mechanical testing was performed using a an ElectroPuls® E10000 Linear-Torsion machine (Instron, MA, USA) according to ISO 527-1:2019 [61] (Figure 4a) at a constant crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. Mechanical response was evaluated based on the recorded stress–strain curves.

Figure 4.

(a) Equipment used to perform tensile tests of 3D-printed samples; (b) 3D-printed test specimens fabricated from ABS and ABS-based composite filaments used for mechanical characterization. Materials are arranged from left to right as follows: ABS, ABS–5BN, ABS–30W, ABS–10Gd2O3, and ABS–30Bi2O3.

2.5. Evaluation of Surface Morphology and Topography

Surface topography of some experimental samples has been performed using atomic force microscope (NanoWizard III AFM, JPK Instruments, Bruker Nano GmbH, Berlin, Germany). AFM images were collected using a V-shaped silicon cantilever (spring constant of 3 N/m, pyramidal tip shape, tip curvature radius (ROC) of 10.0 nm, and cone angle of 20°) operating in contact quantitative imaging mode. Data were analyzed using JPKSPM data processing software (Version spm-4.3.25, JPK Instruments, Bruker Nano GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Surface and cross-sectional morphology of experimental samples have been assessed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-3400 N, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a secondary electron detector. In addition, elemental composition and elemental mapping of the 3D-printed composite polymers, reinforced with metal oxide nanoparticles, were investigated with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Bruker Quad 5040, Billerica, MA, USA).

To determine the attenuation properties of the in-house produced materials, and to assess the homogeneity of samples and radiation density of fabricated materials, CT scans of experimental samples printed with 100% infill density were analyzed using the software package ImageJ 1.54g (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Sample images were acquired by CT (Siemens Light Speed RT16, Erlangen, Germany) using the same exposure parameters (head protocol; tube voltage 120 kV; current 335 mA).

2.6. Radiation Attenuation Measurements

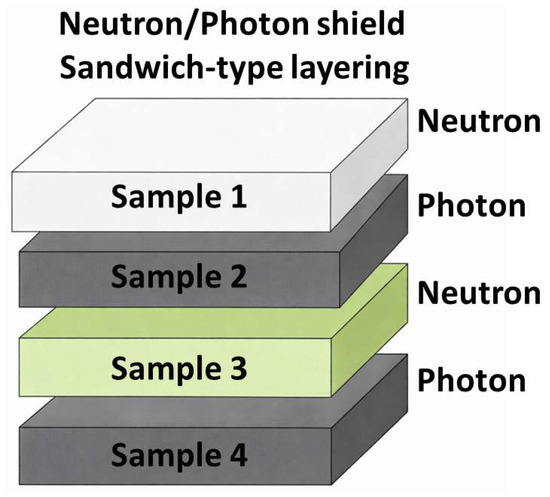

Radiation attenuation was evaluated for all samples using two irradiation conditions: X-rays (120 kVp) and mixed neutron–photon fields from a Pu–Be source. For both modalities, a reference dose was measured in the direct beam, followed by the transmitted dose with the sample in place. All exposures delivered a nominal 1 Gy. Measurements were performed for individual samples and for a multilayer stacked configuration (Figure 5), where the incident beam entered the materials in the following order:

Figure 5.

Multilayer configuration used in attenuation experiments, illustrating the sequential arrangement of composite samples for mixed-field photon–neutron shielding evaluation.

- ABS–5BN;

- ABS–30W;

- ABS–10Gd2O3;

- ABS–30Bi2O3.

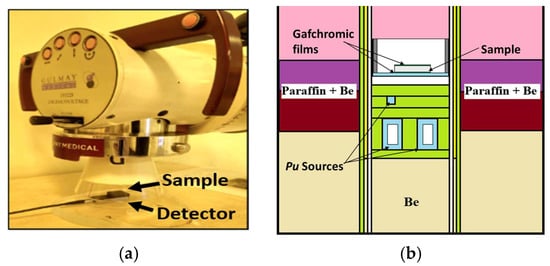

Low-energy photon attenuation was examined using a Gulmay D3225 X-ray unit (Gulmay Medical Ltd., Surrey, UK) operated at 120 kVp. Dose readings were obtained with a Piranha dosimetry system (RTI Group, Mölndal, Sweden) (Figure 6a). Gafchromic EBT3 films (Ashland, Wilmington, DE, USA), calibrated for this beam quality, were placed at the same measurement position to provide independent verification of detector readings.

Figure 6.

(a) Experimental setup for 120 kVp X-ray attenuation measurements. (b) Schematic of the Pu–Be mixed neutron–photon irradiation geometry.

Mixed-field attenuation was assessed using a Pu–Be source (4.5 × 107 n/s) with a central channel neutron flux of 7.12 × 104 n/cm2/s, consisting of 68% thermal, 9% epithermal, and 23% fast neutrons. Attenuation was quantified using EBT3 films calibrated for current beam and placed directly behind each sample along the central irradiation axis (Figure 6b).

2.7. Data Analysis and Attenuation Calculations

Because the detectors used in this study (Piranha system and EBT3 films) measure absorbed dose, attenuation was evaluated directly from the ratio of transmitted to reference dose. Under narrow-beam conditions, this dose ratio is proportional to the primary beam intensity, allowing the Beer–Lambert law to be applied without additional scatter corrections. The attenuation percentage both for X-ray and Pu-Be source irradiation was calculated as

where D0 is the reference dose measured directly and Dt is the transmitted dose measured with the sample in place.

To allow comparison between shielding configurations with different total thicknesses, a thickness-normalized attenuation parameter, keff, was additionally calculated based on the measured dose ratio. This parameter was defined as

where dtot is the total thickness of the tested shielding configuration expressed in centimeters; for multilayer stacks, keff represents an empirical, order-dependent metric that reflects the overall attenuation behavior of the specific layer sequence under the given irradiation conditions.

For photon attenuation measurements, the experimental mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) of each composite was obtained using

To compare the photon attenuation performance of the composites with lead, the relative attenuation efficiency (RAE) was calculated using

This parameter expresses the photon shielding capability of each material as a percentage of lead’s attenuation efficiency at the same energy.

Theoretical attenuation for photons was estimated using NIST XCOM MAC values at 50–60 keV, corresponding to the effective energy of the 120 kVp polyenergetic X-ray beam. Using the monoenergetic value at 120 keV would underestimate attenuation because it does not represent the actual beam spectrum.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extrusion of Filaments and Their Characterization

As shown in Table 2, all composite filaments exhibited reduced surface quality (grainy or slightly textured) and some flow issues (pulsing or minor clogging) compared to pure ABS, which had a smooth surface and flow. This degraded flowability in filled polymers is expected, as incorporating shielding fillers typically leads to high melt viscosity, hindering the extrusion process [57,59].

Table 2.

Filament extrusion characteristics for ABS-based composites.

Specifically, the W and Bi2O3 composites suffered from a pervasive “pulsing flow”, suggesting viscosity issues that were mitigated during printing by increasing the extrusion temperature from 265 °C to 280 °C to achieve a more stable melt flow (Table 3). This adjustment aligns with the principle that higher extrusion temperatures are often necessary to maintain flow quality when printing composites.

Table 3.

Printing issues encountered and corresponding parameter adjustments.

Optimization of printing parameters was essential to counter the inherent material challenges and achieve functional density, confirming that precise parameter adjustment is critical for high quality composite printing, as noticed in previous works as well [50,55,56,57,58,59]. The adjustments detailed in Table 3, such as reducing print speed and controlling the extruder flow rate, addressed issues like surface roughness and over-extrusion, factors known to negatively impact layer uniformity and lead to defects.

Despite the optimization, all printed composites showed slightly lower measured densities than theoretical values (Table 4), a typical outcome of FDM processes where micro-voids and incomplete interlayer fusion reduce bulk compactness. The highest discrepancy occurred in the W and Bi2O3 composites (−5.7% and −5.9%, respectively), materials that also exhibited the most significant extrusion flow issues (Table 2). This connection highlights that flowability issues during printing can result in the formation of pores and voids in the final components as mentioned also by other research groups [50,53,57,58,59].

Table 4.

Theoretical and measured densities of printed materials.

Similar density deficits (95–99% of theoretical) were reported for W- and B4C-filled PEEK composites by Wu et al. [54,57], who attributed the loss to viscosity-driven limitations in melt flow. These results confirm that densification limitations are inherent to highly filled 3D-printed shielding materials and must be considered when interpreting attenuation trends.

3.2. Characterization of 3D-Printed Samples

It should be noted that the main focus of this article was the evaluation of the mixed-beam attenuation properties of newly developed and fabricated 3D printing materials. It is assumed that this first step is absolutely necessary for the selection of the best attenuating composites and multilayer compositions for the real fabrication of shielding constructions and for avoiding the unnecessary fabrication and detailed investigation of the morphological, mechanical, and thermal properties of less suitable samples. Examples of the rough investigation of ABS reinforced with Bi2O3 particles are provided below.

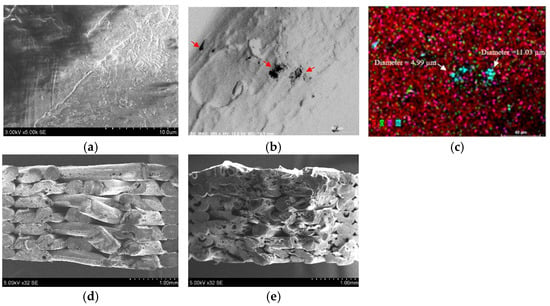

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was carried out on the surfaces and fractured surfaces of the ABS and ABS–30Bi2O3 composites, to identify mechanisms believed to be responsible for the observed changes in the fracture surface. The corresponding SEM images and EDX map for the ABS–30Bi2O3 composite are provided in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

SEM micrographs of ABS surface (a) and fracture surface resulting from tensile testing (d) and ABS–30Bi2O3 surface (b) with EDX image (c) and fracture surface resulting from tensile testing (e). Attention: magnification in different images is different.

As can be seen from Figure 7, the added filler content leads to an increase in elastic fracture, with more polymer spikes visible on the fracture surface compared to pure ABS. Moreover, in samples with 30% filler content, filler agglomerations are visible (Figure 7c). These agglomerations appear to influence the brittleness of composites compared to pure ABS. These findings agree with the tensile stress results provided in Section 3.3 of this article.

Additionally, it was observed that for the high filler loadings, as it was in the case of ABS–30Bi2O3, the potential agglomeration of filler particles likely caused small, air-filled voids and pores to form in the 3D-printed samples, indicating the influence of the extruded polymer composite filament’s inhomogeneity, both in terms of filler distribution within the polymer matrix and the filament’s shape.

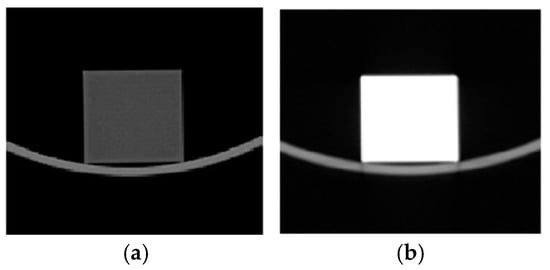

The radiation density of the material plays an important role when analyzing the attenuation properties of the materials. An investigation of the CT scans of the experimental samples measured across five consecutive sample slices was performed (Figure 8) and evaluated using ImageJ program package, which indicated a very high radiation density of 3071 ± 9.584 HU for ABS–30Bi2O3 as compared to 133.069 ± 17.459 for ABS. It should be mentioned that radiation density was calculated specifically for photon beams.

Figure 8.

CT scans of experimental samples: (a) ABS, (b) ABS–30Bi2O3.

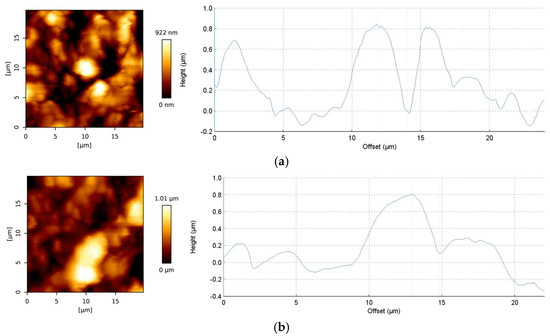

The results of the performed AFM measurements were in line with the discussed SEM results. Increased surface roughness of 3D-printed ABS polymers containing 30% of Bi2O3 and less uniform surface profile was observed, compared with printed pure ABS samples (Figure 9). Specifically, the average roughness Ra (arithmetic average of the absolute values of the profile heights over the evaluation length) value of 177.4 nm and root mean square roughness Rq (RMS average of the profile heights over the evaluation length) value of 229.6 nm for ABS–30Bi2O3 were observed in comparison with 163.0 nm and 209.6 nm for pure ABS.

Figure 9.

The 2D surface topography and roughness height profiles of ABS (a) and ABS-30Bi2O3 (b) samples.

More detailed analysis of ABS containing different concentrations of Bi2O3 can be found in our previous paper [58].

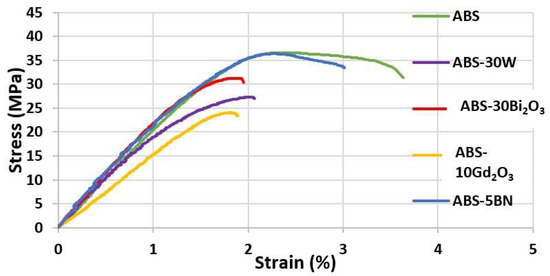

3.3. Initial Mechanical Testing Results of Experimental Samples

Tensile tests of all experimentally fabricated 3D-printed samples have been investigated and the results are shown in the form of stress–strain curves in Figure 10. It is evident that all additives incorporated into the ABS polymer matrix reduced the plasticity of ABS. The lowest impact was observed for BN filler: the ABS–5BN composite was less brittle, but had almost the same UTS value of 36.35 MPa as ABS. Young’s modulus values for ABS–5BN and ABS–30Bi2O3 composites were almost the same at 2133 MPa and slightly higher than the value of 2083 MPa for pure ABS. ABS–30Bi2O3 and ABS–10Gd2O5 were most brittle from all investigated samples. In addition, the ABS–10Gd2O5 composite indicated the lowest value of 1552 MPa for Young’s modulus.

Figure 10.

Stress–strain curves of the investigated initial ABS—based composites.

The performed investigation revealed that the mechanical properties (tensile) of ABS are reduced after the incorporation of fillers into the matrix. Experimental composites from the investigated set can be compatible when adjusting their mechanical properties for the fabrication of layered shielding constructions accordingly.

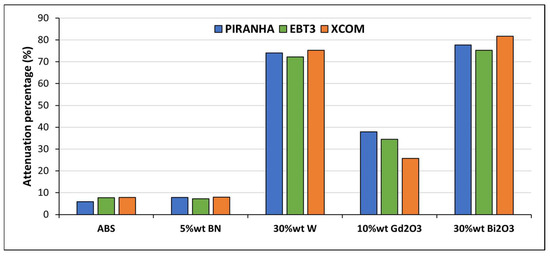

3.4. Attenuation Properties of the Experimental 3D-Printed Samples

The attenuation of X-rays in the energy range of 120 kVp is governed primarily by the photoelectric effect, which scales steeply with the atomic number (Z4 − 5) of the absorbing material. This fundamental principle is directly reflected in the measured attenuation percentage of the shielding composite materials (Figure 11). The material with the lowest measured performance, ABS–5BN, showed only ~7.98% attenuation. This result is expected because boron compounds (such as boron nitride) consist of low-Z elements and thus offer minimal photon shielding. A substantial increase in shielding was observed with high-Z fillers. The ABS–30W composite achieved ~72–75% attenuation across Piranha, EBT3, and XCOM, reflecting tungsten’s high photoelectric interaction probability at energies around 120 kVp. The ABS–30Bi2O3 composite demonstrated the highest overall attenuation (~78–82%), which is consistent with bismuth’s higher atomic number and its K-edge proximity (90.5 keV) to the peak of the 120 kVp X-ray spectrum, enhancing photoelectric absorption [31,54]. The ABS–10Gd2O3 composite provided ~35–40% attenuation which is lower than W and Bi2O3 due to both its lower weight fraction and lower Z.

Figure 11.

Attenuation performance of ABS-based composite samples at 120 kVp measured using Piranha, EBT3 film, and XCOM calculations.

Piranha-based measurements were selected as the primary attenuation quantification method, with EBT3 film used for independent validation; the close agreement between the two confirms the stable fabrication and acceptable sample uniformity. XCOM calculations showed some discrepancies compared to measurement results, which are expected because XCOM assumes an ideal, homogeneous material and a strictly monoenergetic beam, while our measurements were conducted in a polychromatic spectrum and are influenced by FDM-related microstructural variations.

The measured mass attenuation coefficients (MACs) further confirmed the strong dependence of the shielding performance on the filler atomic number and loading (Table 5) [39,59]. Pure ABS demonstrated the lowest MAC (0.12 cm2/g), reflecting the limited photon interaction probability of low-Z polymers [51]. The slight increase observed for ABS–5BN (0.16 cm2/g) is consistent with BN’s modest contribution to photoelectric absorption at diagnostic energies. In contrast, the incorporation of high-Z fillers produced substantial increases in the MACs.

Table 5.

Mass attenuation coefficients (MACs) of ABS-based composites at 120 kVp.

ABS–30W exhibited a MAC of 1.95 cm2/g, almost an order of magnitude higher than pure ABS, aligning with the literature reporting exponential MAC growth with increasing W content in polymer matrices. Studies involving W-based polymer composites consistently demonstrate improved radiation shielding performance and are recognized for manufacturing complex 3D-printed parts and wearable equipment where toughness and low toxicity are required. The highest MAC was obtained for ABS–30Bi2O3 (2.30 cm2/g), consistent with the superior attenuation of bismuth-containing composites observed in previous studies (Pavlenko et al., 2019 [36]; Shabib et al., 2025 [38]), as bismuth is favored as a lead-free replacement owing to its high atomic number (Z = 83) and non-toxic nature, offering comparable shielding efficiency. ABS–10Gd2O3 (0.88 cm2/g) showed intermediate MAC values, reflecting both the lower filler loading and Gd’s reduced photoelectric contribution compared to W and Bi [51].

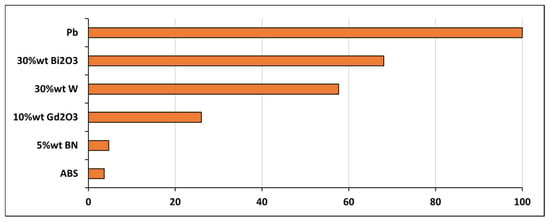

The RAE results were found to clearly distinguish the shielding capabilities of the composites (Figure 12). Lead was measured as the reference material (100%), while ABS–30Bi2O3 was determined to reach ~68%, representing the highest efficiency among the lead-free samples. ABS–30W was observed at ~58%, and ABS–10Gd2O3 at ~26%. Very low efficiencies (<5%) were recorded for ABS–5BN and pure ABS. Generally, the RAE values were shown to align with the attenuation and MAC trends.

Figure 12.

Relative attenuation efficiency (RAE) of ABS-based composites at 120 kVp, benchmarked against lead.

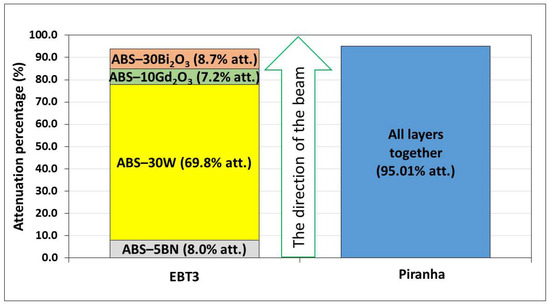

The multilayer configuration was found to produce a cumulative attenuation of ~95%, as shown in Figure 13, demonstrating a strong synergistic effect among the individual layers. Although Bi2O3 showed the highest attenuation when measured as a single material, the W-containing layer was observed to contribute the largest share within the multilayer system.

Figure 13.

Individual contribution of each layer in the multilayer composite system to total attenuation at 120 kVp (EBT3), compared with overall attenuation measured by Piranha.

This can be explained by the fact that attenuation in a stacked configuration is not determined solely by the intrinsic attenuation coefficient, but by how much additional attenuation each layer provides after the preceding layers have already removed part of the spectrum. Since W interacts strongly with both low- and mid-energy photons, it removes a substantial portion of the incident beam before significant spectral hardening occurs. Consequently, the remaining layers encounter a reduced and hardened spectrum, causing their incremental contributions, particularly that of Bi2O3, to appear smaller despite their high individual performance.

The thickness-normalized attenuation values in Table 6 further illustrate that the multilayer configuration is not optimized to maximize photon attenuation per unit thickness, but rather to combine materials with distinct interaction characteristics within a single structure. Because the stack intentionally includes both high-Z photon-attenuating layers and lower-Z functional layers, the resulting keff represents an averaged response over materials with different attenuation efficiencies. Consequently, a lower keff for the multilayer is expected and does not contradict its superior cumulative attenuation, but instead reflects the trade-off between per-thickness efficiency and multifunctional shielding design.

Table 6.

Thickness-normalized attenuation parameter (keff) for single-layer composites and the multilayer configuration under 120 kVp X-ray irradiation.

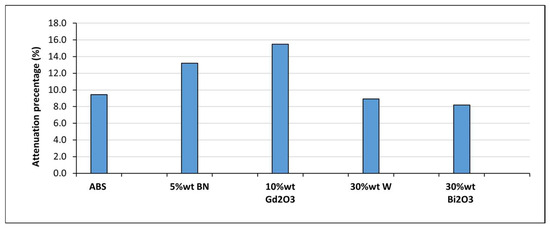

The mixed-field attenuation under Pu-Be source irradiation for single sample results demonstrated behavior distinct from the X-ray measurements, reflecting the fundamentally different interaction mechanisms governing neutrons and secondary photons. In general, attenuation remained modest (8–16%), as can be observed in Figure 14, which is expected for thin polymer-based samples exposed to a broad neutron spectrum. The highest reduction was observed for ABS–10Gd2O3, consistent with gadolinium’s exceptionally high thermal neutron capture cross-section [44]. A similar, though smaller, enhancement was recorded for ABS–5BN, consistent with boron’s capacity to absorb thermalized neutrons [42]. In contrast, ABS–30W and ABS–30Bi2O3 exhibited only limited attenuation, aligning with the fact that high-Z fillers contribute minimally to fast-neutron moderation or capture. However, some measurable attenuation was still detected in these composites because the EBT3 film recorded an integrated response to both neutron-induced dose and accompanying secondary photon dose. As a result, photon interactions within W- and Bi-containing samples contributed to the measured film response, and the reported attenuation values therefore represent an effective mixed-field dose reduction rather than a quantitative separation of neutron capture and photon attenuation mechanisms.

Figure 14.

Mixed-field attenuation of ABS-based composites measured with EBT3 film under Pu–Be source irradiation.

Furthermore, it should be noted that ABS, while offering excellent printability and structural stability, contains a lower hydrogen density compared to polyethylene-based matrices, which are more effective for fast neutron moderation. Quantitatively, ABS contains approximately 7–8 wt% hydrogen, compared to ~14.4 wt% for high-density polyethylene, corresponding to roughly two times lower hydrogen atom density [49,59]. As a result, neutron slowing in the present ABS-based samples was inherently limited, particularly given the relatively small sample thickness of 5 mm, which provided an insufficient path length for extensive moderation prior to thermal neutron capture. Consequently, the observed mixed-field attenuation was dominated by thermal neutron capture rather than moderation effects. Future work will therefore explore hydrogen-rich matrices such as HDPE in combination with neutron-absorbing fillers to enhance fast neutron moderation while retaining the advantages of additive manufacturing.

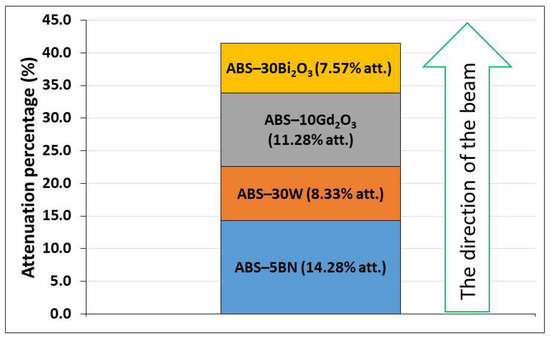

The multilayer configuration was designed based on established neutron–photon shielding principles, where neutron-absorbing and photon-attenuating materials are arranged in an alternating sequence. Neutron capture reactions in boron- and gadolinium-containing layers are accompanied by the emission of secondary gamma radiation, causing these layers to act as secondary photon sources. The inclusion of adjacent high-Z layers therefore enables the attenuation of both primary and secondary photons. Repeating neutron–photon stages allow the progressive reduction in residual radiation components, providing more efficient mixed-field attenuation within a compact structure [30,41].

Under Pu–Be irradiation, the multilayer exhibited a cumulative attenuation composed of distinct contributions from each layer (Figure 15), reflecting the differing neutron interaction mechanisms of the fillers [57]. The BN-containing layer exhibited the largest effective attenuation (~14.3%), which is consistent with the strong affinity of boron for absorbing thermalized neutrons. The ABS–10Gd2O3 layer followed (~11.3%), supported by gadolinium’s exceptionally high thermal neutron capture cross-section. These two layers dominated the overall response, suggesting that neutron capture-related processes played a dominant role in the effective mixed-field attenuation. The noticeable, though smaller, contributions from the ABS–30W and ABS–30Bi2O3 layers (~8.3% and ~7.6%, respectively) show that photon-sensitive materials still played a role in the mixed field, consistent with the fact that EBT3 integrates both a neutron- and photon-induced dose. Because the layers were arranged in an alternating neutron–photon–neutron–photon attenuating materials sequence, the observed pattern reflects the interplay between moderation/capture processes and photon attenuation rather than a simple upstream–downstream depletion effect. The results therefore highlight that, in this geometry, neutron-active fillers largely govern dose reduction, while high-Z layers mainly provide an additional, secondary contribution linked to the photon component of the Pu–Be field.

Figure 15.

Individual contribution of each layer in the multilayer composite system to total attenuation of Pu–Be source mixed-field irradiation, based on EBT3 film response.

The thickness-normalized attenuation values in Table 7 indicate that neutron-active single layers (ABS–5BN and ABS–10Gd2O3) exhibit higher keff than photon-dominant composites, reflecting the dominance of thermal neutron capture in the mixed field. The multilayer configuration shows a lower keff despite higher cumulative attenuation, as its thickness is distributed among materials with different neutron and photon interaction roles. Moreover, neutron capture in BN- and Gd-containing layers is accompanied by secondary gamma emission, which contributes to the dose recorded by EBT3 and limits the apparent per-thickness attenuation.

Table 7.

Thickness-normalized attenuation parameter (keff) for single-layer composites and the multilayer configuration under Pu–Be mixed-field irradiation.

Future research may focus on optimizing layer sequencing and thickness ratios to enhance the mixed-field attenuation efficiency while minimizing material usage. Incorporating higher loadings of neutron-active fillers or exploring alternative isotopes with strong capture cross-sections could further improve performance. Detailed Monte Carlo modeling should be employed to resolve the individual neutron and photon contributions measured by EBT3 films. Additionally, evaluating the mechanical integrity, thermal behavior, and long-term stability under prolonged irradiation would support the development of application-ready, lead-free multilayer shields.

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrated that ABS-based composites containing BN, W, Gd2O3, and Bi2O3 can be successfully processed into filaments and 3D-printed into functional shielding structures, confirming the feasibility of additive manufacturing for lead-free radiation protection applications. Although high filler loadings introduced viscosity-related challenges and minor porosity, careful adjustment of the extrusion and printing parameters enabled the fabrication of dense, mechanically stable components. Under 120 kVp X-ray irradiation, W- and Bi2O3-filled composites showed high attenuation efficiency for the investigated formulations, and the multilayer architecture achieved ~95% attenuation, illustrating the capability of 3D printing to tailor material distribution within complex shielding designs. Mixed-field Pu–Be measurements highlighted the complementary behavior of neutron-active and photon-active fillers, demonstrating that customized layer sequencing can be strategically used to target specific radiation environments. In conclusion, these results show that 3D printing enables lightweight, geometry-flexible, and compositionally tunable shielding materials, offering a promising pathway toward application-ready alternatives to conventional lead-based systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.; methodology, S.A.; validation, S.A. and D.A.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, S.A.; resources, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, D.A. and J.L.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, D.A.; project administration, D.A.; funding acquisition, D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the research project grant no. S-MIP-CERN-24-1 of the Research Council of Lithuania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Raineri, R.; Binder, J.; Cohen, A.; Muller, A. Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy in Less Industrialized Countries: Challenges, Opportunities, and Acceptance. Energies 2025, 18, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, A.; Rachlew, E. Nuclear power in the 21st century: Challenges and possibilities. Ambio 2016, 45, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, K. Radiopharmaceuticals and their applications in medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.I.; Kwon, J.; Kim, K.P. Current trends in cyclotrons and Radionuclide production: A comprehensive analysis in the Republic of Korea. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, S.; Casolaro, P.; Dellepiane, G.; Mateu, I.; Mercolli, L.; Pola, A.; Rastelli, D.; Scampoli, P. A novel experimental approach to characterize neutron fields at high- and low-energy particle accelerators. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, T.; Biegała, M. Energy-Dependent Neutron Emission in Medical Cyclotrons: Differences Between 18F and 11C and Implications for Radiation Protection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmeškal, M.; Košt’ál, M.; Lebeda, O.; Zach, V.; Běhal, R.; Czakoj, T.; Šimon, J.; Novák, E.; Matěj, Z. Measurement of secondary neutron spectra and the total yield from 18O(p,xn) reaction. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 229, 112431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegała, M.; Jakubowska, T. Levels of exposure to ionizing radiation among the personnel engaged in cyclotron operation and the personnel engaged in the production of radiopharmaceuticals, based on radiation monitoring system. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2020, 189, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, N.F.; Amira Othman, S.; Amirah Nor Azman, N.F.; Saqinah Jasrin, N. Effect of ionizing radiation towards human health: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 268, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-Q.; Yin, G.; Huang, J.-R.; Xi, S.-J.; Qian, F.; Lee, R.-X.; Peng, X.-C.; Tang, F.-R. Ionizing radiation-induced brain cell aging and the potential underlying molecular mechanisms. Cells 2021, 10, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.-T.; Boonhat, H.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Klebe, S.; Takahashi, K. Health Effects of Occupational and Environmental Exposures to Nuclear Power Plants: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Talapko, D.; Katalinić, D.; Kotris, I.; Erić, I.; Belić, D.; Vasilj Mihaljević, M.; Vasilj, A.; Erić, S.; Flam, J.; et al. Health Effects of Ionizing Radiation on the Human Body. Medicina 2024, 60, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.; Teles, P.; Santos, J. A systematic review on the occupational health impacts of ionising radiation exposure among healthcare professionals. J. Radiol. Prot. 2025, 45, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA Safety Standards for Protecting People and the Environment General Safety Guide No. GSG-7 Occupational Radiation Protection Jointly Sponsored by. (n.d.). Available online: http://www-ns.iaea.org/standards/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Chida, K. What are useful methods to reduce occupational radiation exposure among radiological medical workers, especially for interventional radiology personnel? Radiol. Phys. Technol. 2022, 15, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z. Analysis of the Impact of Nuclear Radiation on Environment and Investigation of Safety Protection. J. Saf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudin, C.; Vacquier, B.; Thin, G.; Chenene, L.; Guersen, J.; Partarrieu, I.; Louet, M.; Ducou Le Pointe, H.; Mora, S.; Verdun-Esquer, C.; et al. Occupational exposure to ionizing radiation in medical staff: Trends during the 2009–2019 period in a multicentric study. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 5675–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisa, M.E.M. Comparative Review of Gamma Ray Shielding Properties of Building and Metallic Materials Using Experimental and Theoretical Methods. Ann. De Chim. Sci. Des Mater. 2025, 49, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.; Suzuki, T. Evaluation of lead aprons and their maintenance and management at our hospital. J. Anesth. 2016, 30, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.-J.; Kim, K.-J.; Jahng, T.-A.; Kim, H.-J. Efficiency of lead aprons in blocking radiation—How protective are they? Heliyon 2016, 2, e00117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.C.; Ünay Çubukçu, N.; Oner, E. The Disadvantages of Lead Aprons and the Need for Innovative Protective Clothing: A Survey Study on Healthcare Workers’ Opinions and Experiences. Usak Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 7, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, O.; Makkawi, K.; Aga, Z.B.; Albakri, H.; Assiri, N.; Althagafy, K.; Ajlouni, A.-W. A review on using nanocomposites as shielding materials against ionizing radiation. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2023, 9, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.M.; Shoag, J.M.; Kahlon, S.S.; Parsons, P.J.; Bijur, P.E.; Taragin, B.H.; Markowitz, M. Lead Aprons Are a Lead Exposure Hazard. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2017, 14, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna-Attisha, M.; Lanphear, B.; Landrigan, P. Lead poisoning in the 21st century: The silent epidemic continues. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1430–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, T.; Lamture, Y.; Kumar, M.; Dhamecha, R. Unveiling the Health Ramifications of Lead Poisoning: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.; Das, A.P. Lead pollution: Impact on environment and human health and approach for a sustainable solution. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2023, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilys, L.; Griškonis, E.; Griškevičius, P.; Adlienė, D. Lead Free Multilayered Polymer Composites for Radiation Shielding. Polymers 2022, 14, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baamer, M.A.; Alshahri, S.; Basfar, A.A.; Alsuhybani, M.; Alrwais, A. Novel Polymer Composites for Lead-Free Shielding Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safari, A.; Rafie, P.; Taeb, S.; Najafi, M.; Mortazavi, S.M.J. Development of Lead-Free Materials for Radiation Shielding in Medical Settings: A Review. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 2024, 14, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X. Radiation shielding polymer composites: Ray-interaction mechanism, structural design, manufacture and biomedical applications. Mater. Des. 2023, 233, 112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrevičius, L.; Laurikaitienė, J.; Laurikaitytė, G.; Adlienė, D. Development of metal/metal oxide enriched polymer composites for radiation shielding of low-energy photons. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 234, 112807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Kang, Q.; Duan, Z.; Qin, B.; Feng, X.; Lu, H.; Lin, Y. Development of Polymer Composites in Radiation Shielding Applications: A Review. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2023, 33, 2191–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, S.; Saravanan, T.; Philip, J. A review on polymer nanocomposites as lead-free materials for diagnostic X-ray shielding: Recent advances, challenges and future perspectives. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 4, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Khalafi, H.; Tohidifar, M.R.; Bagheri, S. Thermoplastic and thermoset polymer matrix composites reinforced with bismuth oxide as radiation shielding materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 278, 111443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Ö.; Eren Belgin, E.; Aycik, G.A. Effect of different tungsten compound reinforcements on the electromagnetic radiation shielding properties of neopentyl glycol polyester. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlenko, V.I.; Cherkashina, N.I.; Yastrebinsky, R.N. Synthesis and radiation shielding properties of polyimide/Bi2O3 composites. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, N.; Karaman, M.; Aksoy, R. Structural, Mechanical, and Radiation Shielding Properties of Epoxy Composites Reinforced with Tungsten Carbide and Hexagonal Boron Nitride. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 8860–8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabib, M.; Tawfik, E.K.; Reheem, A.M.A.; Nada, A.; Ashry, H.A. Evaluation of bismuth oxide nanoparticles for enhanced gamma-ray/neutron shielding in HDPE-based composites. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2025, 225, 112010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonlek, C.; Wimolmala, E.; Hemvichian, K.; Mahathanabodee, S.; Poltabtim, W.; Toyen, D.; Lertsarawut, P.; Saenboonruang, K. PEEK Nanocomposites Containing Bi2O3 or BaSO4: A Complete Determination of X-Ray Shielding, Mechanical, Thermal, and Wear Characteristics Under Harsh Radiation Conditions. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 15057–15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Kuang, S.; Bao, J.; Liu, S. Development and application analysis of high-energy neutron radiation shielding materials from tungsten boron polyethylene. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, S.T.; Ahmad, Z.; Thomas, S.; Rahman, A.A. Introduction to neutron-shielding materials. In Micro and Nanostructured Composite Materials for Neutron Shielding Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Althakafy, J.T.; Liu, Y.; Abo-Dief, H.M.; Huang, M.; Zhou, L.; Su, F.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene fiber/boron nitride composites with high neutron shielding efficiency and mechanical performance. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 2012–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeli, R.; Shirmardi, S.P.; Ahmadi, S.J. Neutron irradiation tests on B4C/epoxy composite for neutron shielding application and the parameters assay. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2016, 127, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyen, D.; Wimolmala, E.; Hemvichian, K.; Lertsarawut, P.; Saenboonruang, K. Highly Efficient and Eco-Friendly Thermal-Neutron-Shielding Materials Based on Recycled High-Density Polyethylene and Gadolinium Oxide Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumazert, J.; Coulon, R.; LeComte, Q.; Bertrand, G.H.V.; Hamel, M. Gadolinium for neutron detection in current nuclear instrumentation research: A review. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2018, 882, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkashina, N.I.; Pavlenko, V.I.; Rudnev, P.I.; Cheshigin, I.V.; Romanyuk, D.S.; Ruchiy, A.Y. Study of radiation-protective characteristics of polyethylene composites with B4C and Bi2O3 to neutron and gamma radiation. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2025, 432, 113732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toto, E.; Lambertini, L.; Laurenzi, S.; Santonicola, M.G. Recent Advances and Challenges in Polymer-Based Materials for Space Radiation Shielding. Polymers 2024, 16, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğul, H.; Agar, O.; Bulut, F.; Kaçal, M.R.; Dilsiz, K.; Polat, H.; Akman, F. A comparative neutron and gamma-ray radiation shielding investigation of molybdenum and boron filled polymer composites. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2023, 194, 110731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jreije, A.; Mutyala, S.K.; Urbonavičius, B.G.; Šablinskaitė, A.; Keršienė, N.; Puišo, J.; Rutkūnienė, Ž.; Adlienė, D. Modification of 3D Printable Polymer Filaments for Radiation Shielding Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogul, H.; Gultekin, B.; Bulut, F.; Us, H. A comparative study of 3D printing and sol-gel polymer production techniques: A case study on usage of ABS polymer for radiation shielding. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 1943–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.M.E.; Khatri, N.R.; Kulkarni, N.; Egan, P.F. Polymer 3D printing review: Materials, process, and design strategies for medical applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez, J.; Fuentealba, M.; Santibáñez, M. Characterization of Radiation Shielding Capabilities of High Concentration PLA-W Composite for 3D Printing of Radiation Therapy Collimators. Polymers 2024, 16, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafi, M.; El-Nahal, M.A.; Sayyed, M.I.; Saleh, I.H.; Abbas, M.I. Novel 3-D printed radiation shielding materials embedded with bulk and nanoparticles of bismuth. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, D. Neutron shielding performance of 3D-Printed boron carbide PEEK composites. Materials 2020, 13, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, S.J.; Robison, T.; Long, A.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Brounstein, Z.; Lee, K.-S.; Geller, D.; Lum, E.; Labouriau, A. Flexible 3D printed silicones for gamma and neutron radiation shielding. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2021, 188, 109616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, H.; Wan, K.; Li, D.; He, Q.; Wu, H. High-performance PEEK composite materials research on 3D printing for neutron and photon radiation shielding. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 185, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, D. Mechanical properties and gamma-ray shielding performance of 3d-printed poly-ether-ether-ketone/tungsten composites. Materials 2020, 13, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jreije, A.; Keršienė, N.; Griškevičius, P.; Adliene, D. Properties of irradiated Bi2O3 and TiO2 enriched 3D printing polymers for fabrication of patient specific immobilization devices in radiotherapy. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 2024, 549, 165298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J. The Advancement of Neutron-Shielding Materials for the Transportation and Storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel. Materials 2022, 15, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 527-2:2025; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Test Conditions for Molding and Extrusion Plastics. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/527-2 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles (3rd ed.). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.