Abstract

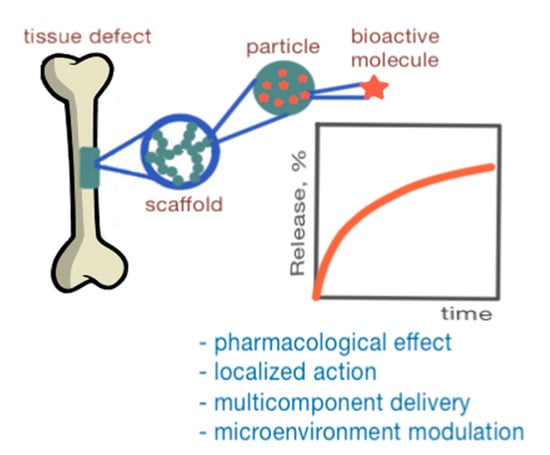

Tissue engineering offers a promising solution by developing scaffolds that mimic the extracellular matrix and guide cellular growth and differentiation. Recent evidence suggests that scaffolds must provide not only biocompatibility and appropriate mechanical properties, but also the structural complexity and heterogeneity characteristic of natural tissues. Particle-based scaffolds represent an emerging paradigm in regenerative medicine, wherein micro- and nanoparticles serve as primary building blocks rather than minor additives. This approach offers exceptional control over scaffold properties through precise selection and combination of particles with varying composition, size, rigidity, and surface characteristics. The presented review examines the fundamental principles, fabrication methods, and properties of particle-based scaffolds. It discusses how interparticle connectivity is achieved through techniques such as selective laser sintering, colloidal gel formation, and chemical cross-linking, while scaffold architecture is controlled via molding, templating, cryogelation, electrospinning, and 3D printing. The resulting materials exhibit tunable mechanical properties ranging from soft injectable gels to rigid load-bearing structures, with highly interconnected porosity that is essential for cell infiltration and vascularization. Importantly, particle-based scaffolds enable sophisticated pharmacological functionality through controlled delivery of growth factors, drugs, and bioactive molecules, while their modular nature facilitates the creation of spatial gradients mimicking native tissue complexity. Overall, the versatility of particle-based approaches positions them as prospective tools for tissue engineering applications spanning bone, cartilage, and soft tissue regeneration, offering solutions that integrate structural support with biological instruction and therapeutic delivery on a single platform.

1. Introduction

Despite the ongoing development of medicine, the loss or damage of tissue structure and function caused by trauma, aging, tumoral removal, or infectious disease represents a huge amount of medical cases [1,2,3,4]. This problem is negatively affected by the tissue aging associated with growing life expectancy [5]. Currently applied clinical practices, such as autografts, allografts, and implants, have their definite limitations [6]. The first ones can only be taken from a limited number of locations within the human organism, and the volume of tissues that can be taken without negative consequences is also highly restricted [7]. Allografts are also prone to foreign body responses. Implants can be designed for a much broader range of cases, but still cannot provide lost tissue remodeling and vascular ingrowth, which often leads to the malfunction of surrounding tissues [8]. In light of the foregoing, the development of innovative solutions that can improve the healthcare of the aging population and those living with disease continues to be a global challenge.

Tissue engineering represents a promising interdisciplinary scientific field that offers a unique opportunity to grow living tissue in vivo or in vitro in order to replace failing or malfunctioning tissues in a patient by using the patient’s own cells [8,9]. This field has been defined by Laurencin [10] as “the application of biological, chemical and engineering principles toward the repair, restoration or regeneration of living tissues using biomaterials, cells and factors alone or in combination”. The goal of tissue engineering can be reached by the development of precisely constructed media for supporting cells and guiding their growth. These media are called scaffolds, and they take over the role of the natural extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM provides cells with a supportive framework of structural proteins, carbohydrates, and signaling molecules [6]. An ideal scaffold must mimic the ECM and be composed of a biomaterial that provides all the necessary signals for cells to grow, differentiate, and interact, forming the target tissue structure [11].

The design of scaffolds plays a critical role in the success of regenerative medicine [11]. Their primary function is to guide the growth of cells, either those seeded within their porous network in vitro or those infiltrating from host tissue in vivo. Since most mammalian cells are anchorage-dependent, scaffolds must first provide a suitable substrate for attachment [9]. With many tissue engineering strategies now relying on stem cells [12,13,14,15], scaffolds must additionally support their differentiation into specific cells [8]. Other essential requirements include biocompatibility and biodegradability to enable tissue development and remodeling, as well as ease of processing into desired shapes. A highly porous architecture is crucial for efficient nutrient delivery and waste removal. In the context of connective tissue regeneration, scaffolds must also possess sufficient mechanical strength and dimensional stability [11,16,17].

Over the past decade, it has become increasingly evident that, in addition to the features mentioned above, scaffolds must also replicate the complexity and heterogeneity of the natural ECM [18,19,20,21]. It is well known that the natural ECM contains gradients of special signals and structural heterogeneity, which enable directed cell migration, vascularization, and the regulation of tissue density [11]. Thus, the development of methods for fabricating scaffolds with gradients of mechanical and biological properties is currently one of the crucial tasks for the success of tissue engineering.

One of the strategies for regulating the mechanical and biological properties of scaffolds is to incorporate micro- and nanoparticles into their structure [22]. For decades, such particles have been extensively studied for drug and gene delivery, progressing from the delivery of small molecules [23,24,25] to complex biomolecules like proteins [26,27,28] and nucleic acids [29]. These particles can be fabricated from a wide range of materials, including polymers, ceramics, and metals [30]. Numerous approaches have employed them as a minor phase within composite scaffolds to enhance material properties [31,32]. For example, silver nanoparticles have great significance in antimicrobial applications due to their potent bactericidal activity [33]. Ceramic particles, especially calcium phosphate [34], hydroxyapatite (HA) [35], as well as bioglass [36,37] and biosilica [37], are of interest because they allow the mechanical strength to be increased and enhance the bioactivity of scaffolds. As an example, biosilica particles isolated from the marine sponge Axinella infundibuliformis and incorporated into marine-derived collagen materials promoted fibroblast adhesion and exhibited osteoinductive properties [37]. Polymeric particles with diverse composition and tunable properties have also demonstrated a significant impact on the characteristics of scaffolds [38,39]. A key advantage of these polymeric systems is their capacity for the encapsulation and controlled release of bioactive molecules that are critical for tissue regeneration [40,41,42]. Beyond their role within the scaffold bulk, nanoparticles are also highly valuable as surface-modifying agents. Their application in this context allows control over surface topology, which is crucial for cell–material interactions [19,43,44]. Despite considerable research efforts, the creation of scaffolds with a controlled microstructure that accurately mimics the intercellular matrix of native tissue still represents a major challenge. In this context, the application of particles to fine-tune the bulk, surface, pharmacological, and biosignaling properties of scaffolds is of great interest [22,45,46,47].

As previously discussed, particles are commonly incorporated as a minor phase in numerous composites and serve as reinforcing agents or drug delivery vehicles. In contrast, scaffolds where particles themselves constitute the primary matrix-forming material are far less common. At the same time, particle-based scaffolds expand the poorly explored niche of materials that can provide very good performance as ECM-mimicking materials. Fundamentally, the precise combination of different particles with various natures, rigidities, sizes, surface modifications, etc., can serve as a versatile “toolbox” to precisely control the mechanical, biological, and pharmacological properties of scaffolds. Organizing multiple particle types into a material is a promising approach for developing well-vascularized scaffolds that effectively support cell ingrowth and new tissue formation.

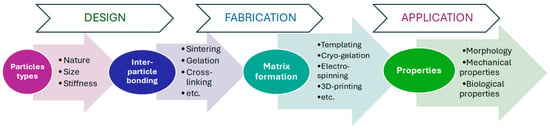

Given the significant potential of particle-based scaffolds, this review focuses on structures where particles constitute the primary matrix-forming phase, or where materials are enriched in particles rather than acting as a minor additive. To contextualize this review, it is important to acknowledge several excellent recent review papers on related topics. Xuan L. and colleagues have comprehensively reviewed microgel systems used in tissue engineering [48], while Bektas and colleagues have discussed in detail the use of microgels for bone tissue regeneration [49]. However, these reviews focus specifically on microgels as functional units rather than on their use as building blocks for scaffold formation. Similarly, a review on microspheres for bone and cartilage tissue engineering [50] provides extensive information on fabrication methods but does not detail the critical aspect of forming interparticle bonds. This specific topic is covered by other notable reviews on granular hydrogels [51,52]. While these reviews are foundational, they are largely confined to microgel-based systems and do not consider other types of particles, such as polyester-based, inorganic ones, etc. Thus, this review aims to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of the vast range of particles used in scaffold construction. The framework of the review is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of the review.

2. Types of Particles for Preparation of Particle-Based Scaffolds

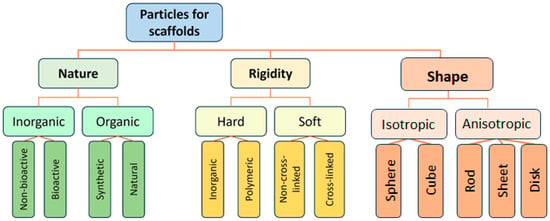

Different types of particles can serve as building blocks for scaffold construction. Just as the quality of bricks determines the characteristics of a building, the choice of particles is crucial, as it predetermines the material’s final properties (Figure 2). These particles act as the foundational units, and their selection directly dictates the scaffold’s physicochemical properties, morphology, and biological performance.

Figure 2.

Classification of particle types used for scaffold preparation.

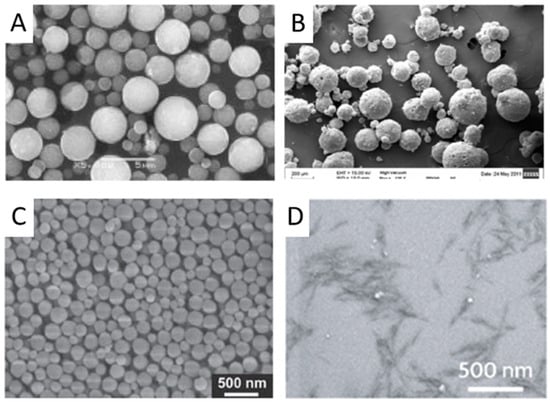

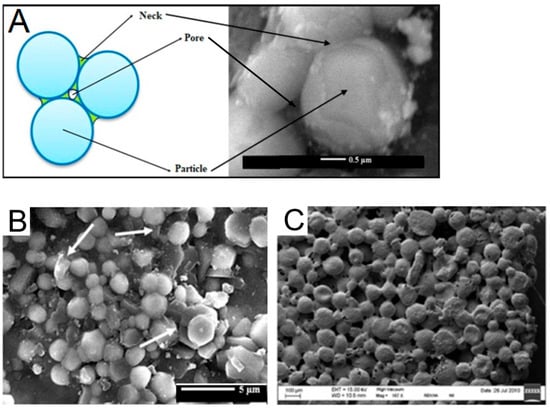

Particles used in scaffold fabrication can be classified by their nature into inorganic and organic ones. Historically, the first particles applied to scaffolds were inorganic [53], which was dictated by the type of process used for the formation of such scaffolds, namely sintering. However, these early scaffolds were primarily suitable for bone tissue regeneration, while the repair of other tissues requires more versatile materials [54]. This motivated researchers to explore polymers and polymer particles as scaffolding materials. Polymer particles can be further subdivided into those based on synthetic and natural polymers. Synthetic polymers usually offer greater control over the mechanical properties of the material and its microstructure, whereas natural polymers allow the formation of biomimetic and cell-instructive structures. A valuable and widely used property of polymeric particles is their suitability for drug encapsulation and sustained release. Consequently, they can function simultaneously as building blocks for the scaffold and as delivery vehicles for bioactive substances or drugs, enhancing the scaffold’s performance both in vitro and in vivo. Particles can also be classified by their shape into isotropic (sphere or cube) or anisotropic (disk, sheet, rod, whisker, and other). The shape of the particles directly affects the scaffold’s pore size and geometry. To date, the majority of particles used have an isotropic spherical shape and form a sphere-packaging type of microporous structure (Figure 3) [55,56,57]. The anisotropy of particles dramatically influences pore size and shape. For example, rod-shaped cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) form gels with a fibrillar macroporous structure [58,59,60]. SEM images of some inorganic and polymer particles are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

SEM images of some inorganic and polymer particles used for scaffold preparation: (A) hydroxyapatite particles (HA). Reproduced with permission from [61] Copyright© 2008, John Wiley and Sons. (B) poly(D,L-lactic acid) (PLA) particles coated with CTAB. Reproduced with permission from [56] Copyright© 2014, American Chemical Society. (C) gelatin A particles. Reproduced with permission from [57] Copyright© 2011, John Wiley and Sons. (D) cellulose nanocrystals (CNC). Reproduced with permission from [58] Copyright© 2023, Elsevier.

Particles for scaffold fabrication can also be classified by their rigidity into hard and soft particles [62]. Inorganic particles are generally hard and, as previously mentioned, are more suitable for regenerating hard connective tissues. They have been widely used in various composites, predominantly to enhance the mechanical properties of the scaffolds. Furthermore, particles based on hydroxyapatite (HA) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) are known to induce osteointegration of scaffolds in vivo. In contrast, soft nanoparticles have been successfully applied for the regeneration of soft tissues, such as the skin [63] and liver [64].

Recent studies have demonstrated that soft polymer microgels based on functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) [65], gelatin methacrylate [66], hyaluronic acid [67], poly(N-vinyl caprolactam) [68], and other polymers show promise for producing microporous granular scaffolds and colloidal gels. Notably, the stiffness of these granular microparticles can be tailored by selecting polymers with different chain flexibilities, adjusting the polymer molecular weight, or modifying the degree of crosslinking within the particles [52].

Modern trends in granular scaffold design include the creation of complex multifunctional compositions. For example, Rui-Chian Tang et al. developed crescent-shaped particles consisting of 4-armed PEG vinyl sulfone as a polymer backbone. These particles incorporated several functional components: peptides (K-peptide, Q-peptide, and RGD peptide) to promote cell adhesion, an MMP-sensitive cross-linker, gelatin as a sacrificial material, and Alpha Fluor 488 for visualization. These hydrogel microparticles have an average diameter of 50 μm with internal cavity sizes ranging from 68 to 84% of the particle diameter after equilibration. The particles were covalently annealed via Michael addition chemistry, where dithiol-modified PEG reacted with residual vinyl sulfone groups on the particle surface. These granular hydrogels were fabricated using a microfluidic water-in-oil droplet emulsion technique that also included a two-phase separation of the PEG and gelatin. This process was followed by overnight incubation at 37 °C, emulsion breaking, and ethanol sterilization [69].

Table 1 summarizes the recent studies on the types of particles and methods for fabricating particle-based scaffolds. It is noteworthy that in many studies, scaffolds have been formed by combining both inorganic and organic particles into interparticle composite structures. This interparticle approach allows for a high degree of control over the scaffold’s mechanical properties.

Table 1.

Types of particles and methods in particle-based scaffold formation.

3. Peculiarities of Particle-Based Scaffold Preparation

Modern tissue engineering requires scaffolds to be supermacroporous supports with interconnected pores and mechanical properties that mimic those of the native tissue. Therefore, fabricating a particle-based scaffold involves organizing particles into a three-dimensional macroporous material with satisfactory mechanical stability. Extending the brick analogy from the title, the “bricks” (particles) must bond to one another through specific interactions. This process primarily addresses two key challenges: (1) ensuring particle connectivity to form the continuous network; and (2) defining the resulting 3D structure and pore architecture. Particle interconnectivity can be achieved through either non-covalent cohesion, which relies on attractive physical forces, or covalent bonding, which involves the formation of chemical bonds between particles. Meanwhile, pore formation can be realized through various methods, such as colloidal gel assembly, cryogelation (freeze-drying), porogen leaching, or 3D printing.

3.1. Interparticle Network Formation

3.1.1. Particle Sintering and Fusion

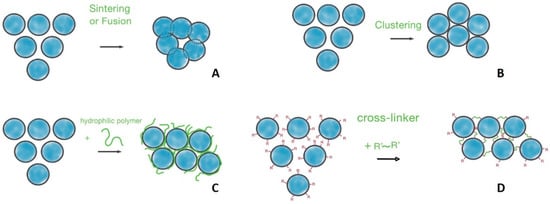

Sintering powder particles into a unified matrix was historically one of the first methods used for scaffold preparation. This technique is based on the fusion of particles through the application of heat or pressure (Figure 4A). It is important to note that this process does not involve melting the particles into a liquid phase. Instead, material diffusion across the boundaries of the particles fuses them into a continuous material structure. Sintering can be used for both inorganic (e.g., bioceramic) and polymeric particles.

Figure 4.

Principal methods of particle interconnection: (A) sintering or fusion; (B) clustering and aggregation of particles; (C) hydrophilic polymer-mediated interaction; (D) covalent cross-linking.

One of the most advanced techniques for the sintering of particles is selective laser sintering (SLS), which is based on the application of laser beam power to heat and fuse the particles. The SLS process offers significant benefits over other techniques because of its ability to produce parts with high dimensional accuracy, excellent mechanical properties [80], and good surface quality [81]. In particular, the SLS technology can accurately control the size, shape, and connectivity of bone scaffolds. Schematical representation of sintering model geometry of spherical particles as well as the SEM images of materials based on sintered inorganic and polymer particles are shown in Figure 5.

Sintering was first applied to fabricate scaffolds from bioceramic particles, such as bio-derived calcium phosphate [71], HA [82], bioglass [83], etc. For example, HA particles can be gelled, and the resulting structures sintered, to form a sponge-like ceramic matrix [72]. However, the need to optimize porosity, interpore connectivity, and surface area, as well as to tune mechanical properties, spurred the development of composite scaffolds combining polymeric and inorganic particles. This approach leverages the high elasticity of polymers and the rigidity of inorganic components to produce materials with enhanced and customizable properties via additive manufacturing. For instance, in a recent study, authors successfully used SLS to fabricate a polyamide (PA12) and HA interparticle composite, which demonstrated good mechanical and biological properties [55]. In another study, spherical composite porous particles were produced by incorporating milled bioglass into or onto foamed PLGA spheres [78]. These particles were subsequently laser-sintered into 3D materials exhibiting high porosity and a tunable microstructure.

Figure 5.

SEM images showing cross-section morphology of matrices obtained by particle sintering or fusion: (A) Scheme of sintering and a fragment of the sintered scaffold. Reproduced with permission from [84] Copyright© 2019, John Wiley and Sons. (B) A two-step sintered HA-Y2O3 biocomposite. Reproduced with permission from [84] Copyright© 2019, John Wiley and Sons. (C) PDLLA-CTAB membranes after fusion of particles by ethanol. Reproduced with permission from [56,57] Copyright© 2014, American Chemical Society.

Polymeric particles, such as PLA coated with hydrophobized chitosan, can also be sintered by surface-selective laser sintering (SSLS) to produce 3D porous materials [77]. It was shown that a hydrophobized chitosan layer effectively stabilized the interface during microparticle fabrication and provided a well-balanced surface hydrophilicity that facilitates water adsorption. During the sintering process, this adsorbed water acted as a sensitizer, responsive to infrared laser irradiation and transferring the heat to the subsurface layer of the PLA particles. This process was optimized to melt only the particle surface successfully, leaving the bulk of the microparticle intact [85].

Polymer particles can be fused not only by heating, but also by swelling the surface layer. For instance, PLA particles can undergo swelling-induced fusion in ethanol [86]. It is known that the stability of aqueous particle suspensions is often maintained by different surfactants. However, adding a non-polar or less polar solvent can disrupt this stability, leading to particle aggregation and the formation of organized 3D structures [87]. This principle was demonstrated in a study where surfactant-coated PLA particles in 100% ethanol fused at room temperature into membrane-type structures [56] (Figure 5C). The authors attributed this fusion to the desorption of the surfactant from the particle surface, accompanied by the formation of polymeric bridges between particles. These bridges represent the transient regions where polymer molecules were solubilized by the ethanol, enabling the formation of a continuous membrane-type structure.

While particle sintering is a powerful and well-established method for creating strong, porous scaffolds from durable materials such as titanium and hydroxyapatite, it has significant limitations for advanced tissue engineering. These include the following: (1) high-temperature or solvent-mediated processing; (2) the formation of closed pores; (3) non-uniform shrinkage; (4) challenges with multi-material and composite scaffolds preparation; and (5) difficulties in incorporating bioactive molecules and living cells. Taking into account such limitations, particle-based scaffold preparation technology has shifted toward low-temperature and room-temperature annealing strategies, which will be reviewed in the following sections.

3.1.2. Particle Clustering and Aggregation in Colloidal Gels

When particles interconnect via attractive, non-covalent surface interactions rather than interpenetration, the material forms through a process of clustering and subsequent aggregation (Figure 3B). This process is primarily driven by the reduction in the particles’ excess free surface energy and the cohesion between chemical groups on their surfaces.

Various non-covalent forces can cause direct particle attraction, clustering, and further aggregation into materials, which are commonly known as “colloidal gels” [88]. The attraction between particles is generally caused by van der Waals [89], hydrophobic [90], solvation [91], or electrostatic [70] forces. Such interactions between particles result in the formation of a heterogeneous structure characterized by the assembly of colloidal particles into strands, which form a mechanically stable particulate network.

The nature of these interparticle forces, along with the particle type, critically affects the scaffold’s rheological and mechanical properties. For instance, scaffolds assembled through electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged particles [74,76,92] aggregate more rapidly and exhibit greater mechanical stability than those formed by hydrophobic interactions. This makes electrostatically bonded scaffolds particularly suitable for tissue engineering applications.

Various biopolymer-based oppositely charged particles have demonstrated the possibility of forming gels upon mixing [57]. For example, such gels can be obtained using dextran microspheres modified by methacrylic acid (Dex-MA) or dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate (Dex-DMAEMA) [74] and gelatin (Gel) particles from different sources (cationic Gel A from porcine skin and anionic Gel B from bovine skin). A solid content of at least 10–15 wt% is generally required to achieve an elastic modulus above 500 Pa. However, the properties of the resulting gels vary significantly. The Dex-MA/Dex-DMAEMA gel exhibits plastic behavior at a low mechanical stress (~10 Pa), indicating that its electrostatic bonds can be easily broken. At the same time, once the stress is removed, the gel shows self-recovery. Furthermore, this gel stability is highly sensitive to ionic strength. In particular, a sharp drop in storage modulus is observed at ionic strength above 0.5 M. In contrast, mixtures of Gel A and Gel B form substantially more stable structures. At a 20% (w/v) solid content, they achieve an elastic modulus of approximately 10 kPa and remain stable at a physiological ionic strength that indicates their superior potential as injectable biomedical scaffolds. Moreover, the authors compared gels based on gelatin microspheres and nanospheres and showed that the latter were considerably more elastic. This enhancement was attributed to the larger specific surface area of the nanospheres, which creates a greater interparticle contact area and thus provides higher resistance to shear forces [57].

Methacrylated gelatin (GelMA) nanospheres have recently been structured into 3D supports via colloid gelation. In this process, the GelMA particles are initially bonded by multiple reversible non-covalent bonds. This design confers shear-thinning properties: under the stress of a printer nozzle, the reversible bonds break, allowing the particles to flow like a liquid. At the same time, when the shear stress is removed, the bonds rapidly re-form, restoring the solid-like gel structure and “fixing” the printed filament in place [93].

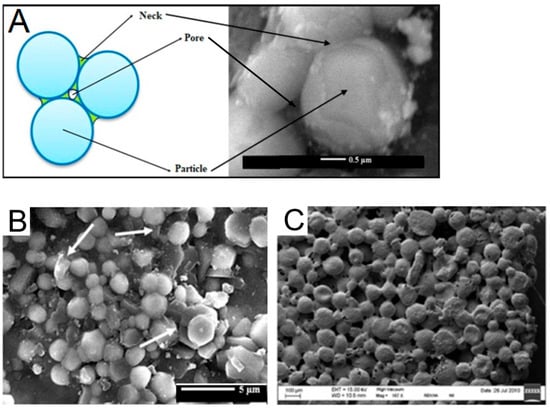

Wang et al. reported the formation of scaffolds by gelling oppositely charged particles made of synthetic biodegradable aliphatic polyester, namely poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) [76]. The surface charge was imparted via nanoprecipitation of the PLGA solution into polyvinylamine (PVAm) to create positively charged particles, and into poly(ethylene-co-maleic acid) (PEMA) for negatively charged ones. Interestingly, that excess of negatively charged particles resulted in more rigid structures. The authors attributed this to the larger zeta potential of the positively charged nanoparticles, suggesting that an excess of negatively charged particles created a more balanced overall charge. While the resulting structures were generally fluid, a particle concentration of 20% produced relatively stable gels (Figure 6). These gels can be used directly or further stabilized by gel lyophilization [76]. Similar results were obtained when a PLGA particle charge was generated by blending with chitosan (positive) and alginate (negative) for the preparation of oppositely charged particles [92].

Figure 6.

Scaffolds made of PLGA nanoparticles with opposite charges (PLGA-PEMA and PLGA-PVAm): (A) photo of stable material made from 20 wt% colloidal gels (1:1 mass ratio). (B) SEM image of material obtained at 7:3 mass ratio of PLGA-PEMA/PLGA-PVAm. Reproduced with permission from [76]. Copyright© 2007, John Wiley and Sons.

The clustering and aggregation of diverse particles with different stiffnesses provide a great opportunity to fabricate organic–inorganic composites with finely tuned mechanical and biological properties [94]. According to Wang et al. [75], nanostructured colloidal composite gels can offer several advantages over conventional bulk composites, including the following: (i) enhanced control over macroscopic scaffold properties by fine-tuning the sub-populations of particulate building blocks [95,96,97]; (ii) injectability/moldability for minimally invasive application into irregular defects [74,76]; (iii) in situ gel formation without the need for potentially cytotoxic gelling/cross-linking agents [95,98]; and (iv) facile incorporation of therapeutic agents [99,100].

It has been shown that calcium phosphate and gelatin nanoparticles can co-assemble into heteroclusters, forming organic–inorganic composites [75]. These systems exhibited superior viscoelastic properties at a gelatin solid content of 10 wt% and a CaP/Gel B ratio between 0.5 and 1. The inclusion of CaP nanoparticles (zeta potential: +3 mV) with the anionic Gel B nanoparticles (zeta potential: −20 mV) significantly enhanced the material’s stiffness. The storage modulus (G’) increased dramatically from 7 to 10 kPa in gels without CaP to as high as 48 kPa in the composite heteroclusters.

Diba et al. developed a smart way to initiate particle aggregation into a material by gradually altering the pH of a colloidal solution [70]. The authors correctly noted that colloidal gels formed by direct mixing often suffer from uncontrollable, nonuniform aggregation and phase separation, which compromise their structural integrity and mechanical strength. To overcome this, they prepared suspensions of gelatin and silica nanoparticles in a basic medium (pH 11), where both components were negatively charged and stable. Glucono-delta-lactone (GDL) was then introduced into the system as a slow acidifier. As GDL hydrolyzed, it gradually lowered pH below the isoelectric point of gelatin, resulting in its charge changing to positive. This triggered the self-assembly of the newly positive gelatin particles with the negative silica particles, allowing the formation of superior gels with a storage modulus (G’) ranging from 10 to 50 kPa.

The interaction between organic and inorganic particles can be further enhanced through surface modification. In a follow-up study, Diba et al. functionalized gelatin particles with calcium-binding bisphosphonate groups, which specifically increased their attraction to calcium-containing bioactive glass particles [101]. The aggregation of these modified particles produced gels that exhibited frequency-independent solid-like behavior. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of these materials could be quite precisely tuned by varying the ratio of bioglass/gelatin nanoparticles.

The reversible nature of non-covalent interparticle interactions is critical for developing advanced biomaterials, enabling the creation of both injectable in situ-forming scaffolds and self-healing systems [70,101]. This self-healing capability was vividly demonstrated in a gelatin/silica nanoparticle gel, which recovered over 100% of its original storage modulus after being subjected to destructive shear [70]. The authors explained this strengthening as a structural reorganization into a more stable configuration. Confocal microscopy confirmed that the recovered gel featured thicker, longer strands and a lower node density compared to the initial network structure. This “strand thickening” effect is likely a result of high shear forces breaking the initial bonds and allowing particles and clusters to reassemble into a more densely packed, robust architecture.

Similarly, a composite gel of calcium phosphate and gelatin nanoparticles also exhibited strong self-healing. It was characterized by almost 70% recovery of initial gel elasticity within 5 min after severe gel network destruction [75]. Together, these findings underscore how reversible bonds facilitate not only injectability but also intrinsic repair mechanisms, making such colloidal gels highly promising for applications requiring durability and resilience.

An interesting approach for the controllable in situ formation of a 3D gel matrix utilizes thermogelable poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (P(NIPAAM-co-HEMA) microparticles [64]. At low temperatures, the microgel particles were swollen and stabilized by electrostatic repulsion. However, when heated to 37 °C, the microgel particles shrink due to their thermosensitive nature. This shrinkage induces hydrophobic interactions between the particles, leading to the formation of a physically crosslinked 3D network.

This assembly of particles into a bulk material is a hallmark of granular gels, where the fundamental principle is jamming [51]. In these systems, a transition from a liquid-like to a solid-like state occurs based on packing density [52]. When the particle volume fraction (φ) of microgels exceeds 0.58, the system reaches a “random loose packing” state and jams. At φ ≈ 0.64, it achieves a “random close packing”, which often requires microgel deformation. In this jammed state, particles are immobilized by physical constraints and interactions with their neighbors until sufficient stress is applied to overcome the packing force. A key property of these jammed systems is shear-thinning: their viscosity decreases under shear stress, enabling injectability and 3D printing [51,52]. This principle has been demonstrated with microgels based on PEG [102], polyacrylamide [51], poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) [52], gelatin [93], and hyaluronic acid [67].

To ensure the stability of interconnected granular gels, secondary cross-linking between particles is often essential. Physical cross-linking relies on non-covalent interactions such as host–guest interactions, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding [65,103,104]. These interactions are more spontaneous and dynamically reversible, supporting properties like self-healing and injectability. Covalent cross-linking strategies for these systems will be discussed in a subsequent section.

Colloidal gels represent a significant paradigm shift from traditional monolithic hydrogels toward more modular and porous architectures. However, their primary limitations arise from the fundamental trade-off between establishing a highly porous network and maintaining robust mechanical integrity. While post-assembly strategies like annealing have successfully addressed many of these challenges, they introduce additional procedural complexity.

The field is actively pursuing several innovative paths to overcome these challenges, including the following:

- -

- The development of stronger, more sophisticated, and bio-orthogonal annealing chemistries (e.g., click reactions);

- -

- Advancements in high-throughput and precise microgel fabrication techniques;

- -

- The creation of composite systems that integrate the porosity of colloid gels with reinforcing fibrous networks or a stronger secondary matrix.

Despite the current limitations, the exceptional injectability, high porosity, and modular nature of colloidal gels establish them as a uniquely powerful platform for non-load-bearing tissue regeneration, 3D bioprinting, and drug delivery applications.

3.1.3. Flexible-Chain Polymer-Mediated Interaction

Attractive interactions between particle surfaces may be mediated by dissolved macromolecules that cause their clustering and aggregation (Figure 3C). The resulting architecture depends on several factors: the interaction energy between particles, their volume fraction, and the range of the interaction, which is influenced by molecules in the surrounding medium [105,106,107]. By modulating these parameters, one can steer the process toward distinct outcomes. Fast diffusion-limited clustering occurs when attractions are strong and long-range, producing tenuous branched networks with low fractal dimensions. In contrast, slow reaction-limited cluster aggregation results from weaker, short-range attractions, forming more compact and dense aggregates with higher fractal dimensions [108,109]. For a material at a fixed volume fraction, varying the interaction range is a key control mechanism. Highly attractive interactions produce branched strands, while less attractive ones form compact aggregates [105]. This control can be achieved by introducing ionic low molecular components [110] or specific macromolecules [111] to the medium.

Yuan et al. demonstrated that the microstructure of cationic polyurethane colloidal materials can be controlled by the type of anion mediating their electrostatic aggregation [105]. When aggregated by small anions in phosphate-buffered saline, the particles formed dense aggregates. In contrast, using the carboxylate groups of a poly(acrylic acid) resulted in a tenuous, branched aggregate [105]. The authors used these features to spatially control the localization of cues within the scaffold, thereby enhancing angiogenesis. The discussion of this issue will be presented below.

Flexible-chain polymer-mediated interactions are excellent for creating injectable, self-healing, and stimuli-responsive scaffolds. However, for applications requiring high mechanical strength, predictable long-term stability, and resistance to a dynamic biological environment, the strategy of the covalent annealing of particles provides a more reliable choice.

3.1.4. Particle Cross-Linking

Covalent crosslinking into a unique monolithic structure is preferred for applications requiring greater stability (Figure 4D). This approach provides a versatile route for fabricating scaffolds with controllable properties. It is important to note that covalent cross-linking can be applied after initial particle clustering or can drive the aggregation process itself.

For instance, cross-linking after clustering was applied by Cho et al. [112]. The authors reported the preparation of a thermally responsive hydrogel by first aggregating positively charged microparticles with anionic poly(acrylic acid), followed by covalent cross-linking of particles with glutaraldehyde [112]. This cross-linking formed a stable interparticle network that imparted thermo-sensitivity to the entire matrix and allowed for the incorporation of other functional particles.

In the study by Siders et al., particle hydrogels were used to create microporous scaffolds through annealing hyaluronic acid-based microgel particles [67]. The authors compared several cross-linking techniques, namely, transglutaminase-mediated amide bond formation, thiol-ene Michael addition, and amine/carboxylic acid-based cross-linking. The resulting materials combined microporosity with tunable mechanical properties, making them promising for injectable tissue engineering applications where both cell infiltration and structural integrity are required.

Recently, Morozova et al. reported a method for creating fibrillar hydrogel scaffolds using the Diels–Alder reaction to cross-link two types of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) with furan and maleimide groups [113]. The gelation was studied at various component ratios and temperatures ranging from 20 to 60 °C. The authors determined that a 5 wt% CNC concentration was required to form a stable hydrogel with minimal swelling in aqueous media across different pH.

In our study, we have applied UV-initiated cross-linking to assemble scaffolds from poly(lactic acid) (PLA) nanoparticles and CNC [114]. Both PLA nanoparticles and CNC were methacrylated in order to provide reactivity in a free-radical cross-linking reaction. To enhance the material’s properties, we incorporated gelatin–methacrylate as a macromolecular cross-linker, which was shown to produce matrices with significantly improved viscoelasticity.

Another recent study employed a similar approach. GelMA particles were assembled into 3D materials via a colloidal gel approach and then converted into a permanent, robust scaffold by exposing the formed structure to UV light in the presence of a photoinitiator. This process creates a continuous, covalently bonded fibrous network that fuses the particles into a cohesive whole, blurring their individual boundaries [93].

Chemical reaction-driven annealing of hydrogel microparticles represents the popular approach to granular microgels. The process is based on the formation of covalent bonds between adjacent microgels. These reactions often require modifications to functional groups on molecular chains or the surface of microgels. Popular chemical annealing strategies include enzyme-catalyzed reactions [115], free radical polymerization [116], and click reactions [117].

Hung-Pang Lee et al. presented hydrazone bond formation as a key microgel cross-linking strategy. The proposed method involved mixing aldehyde- and hydrazide-functionalized microgels to provide interparticle cross-linking through reversible hydrazone bonds [102]. This strategy imparted shear-thinning and self-healing properties to the resulting materials.

However, several challenges are associated with interparticle cross-linking in scaffold preparation. Firstly, it can compromise the injectability that makes particle-based systems so attractive. Secondly, the cross-linking chemistry itself is often complex. Finally, there is a persistent risk of cytotoxicity from the reagents or reaction conditions, which is a critical concern when cells are present. A thorough understanding of these trade-offs is therefore crucial for selecting an appropriate cross-linking strategy for a given tissue engineering application.

3.2. Scaffold Shape Control and Pore Structure Formation

Beyond the methods for binding particles, shaping them into specific geometries and pore architectures is critical. In regenerative medicine, a scaffold must conform to the defect site. While granular materials can be packed into cavities, pre-formed scaffolds that match the defect’s shape or can be easily contoured to it offer significant advantages. The optimal geometry is tissue-dependent: flat films or membranes are suitable for epithelial layers, volumetric constructs are essential for connective tissue, and tubular structures are required for nerve and muscle guidance.

Furthermore, a successful scaffold requires a macroporous structure with high interconnectivity. Pores must be at least 100 µm to facilitate cell penetration, viability, and proliferation. Pore morphology is also material-dependent; for instance, fibrous materials typically exhibit elongated pores, while foams tend to have a more spherical shape of pores [118,119].

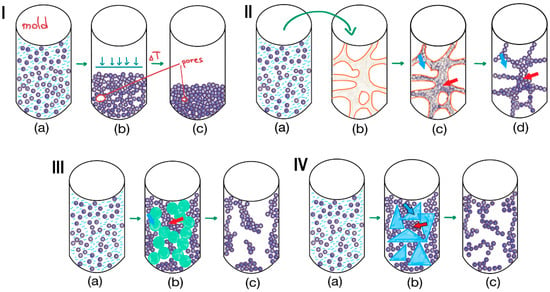

Methods for fabricating scaffolds with controlled shapes and architectures can be broadly classified into two categories: physicochemical methods and instrumental methods.

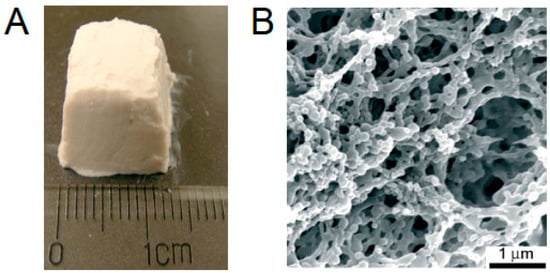

- Physicochemical methods, such as molding, templating, and cryogelation, rely on material properties and spontaneous processes to define morphology and pore structure (Figure 7).

- Instrumental methods, including 3D printing and electrospinning (Figure 8), use specialized equipment to provide the scaffold’s architectural features.

Figure 7.

Methods for 3D structuring and pore formation: (I)—molding: (a)—placing a particles suspension into the mold, (b)—compression of particles, (c)—molded particles-based material; (II)—external templating: (a,b)—placing a particles suspension into the polyurethane sponge; (с)—removal of excess suspension from large pores of polyurethane sponge; (d)—material formed from sintered or fused particles; red arrow shows how particles aggregates form walls; blue arrow shows supermaropore of sponge and then of particles-based matrix; (III)—internal templating: (a,b)—emulsification of particles suspension, (b,c)—solidification of particles in the continuous phase; red arrow shows particles pushed together by emulsion; blue arrow shows emulsion drops, which allow to form supermacropores; (IV)—cryogelation: (a,b)—freezing of the particles suspension, (b,c)—lyophilization of the frozen solvent; red arrow shows unfrozen microphase, in which particles are pushed together by frozen solvent; blue arrow shows crystalline frozen solvent phase, which allow to form supermacropores.

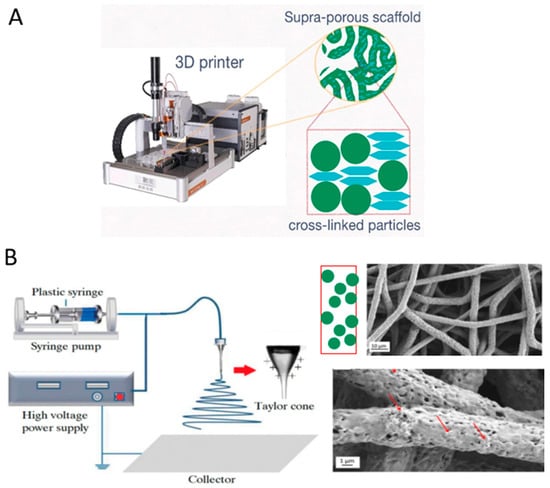

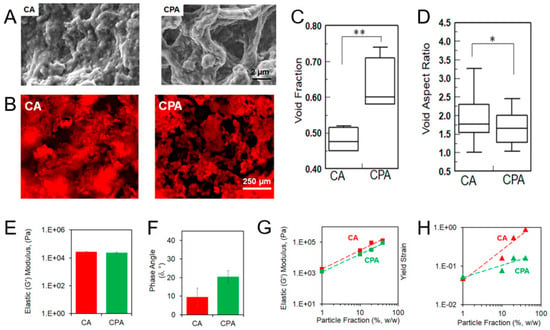

Figure 8.

Instrumental methods for the fabrication of particle-based or particle-rich 3D scaffolds: (A) 3D printing based on direct ink writing combined with stereolithography (UV-mediated cross-linking of rigid (spherical elements) and soft (flattened elements) nanoparticles). Reproduced from [114] under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license; (B) electrospinning. The red arrows indicate HA particles. Adapted from [120,121]. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY li-cense.

However, while some techniques enable simultaneous control over both macroscopic shape and micro-scale pore structure, others primarily control only one of these parameters.

3.2.1. Molding

Molding is the manufacturing process of shaping materials into desired forms. This transformation is achieved by introducing a raw material into a mold—a hollow matrix that determines the shape and size of the final product (Figure 7I(a–c)). However, this technique typically offers control over the macroscopic shape but not the internal micro-architecture.

This type of manufacturing was successfully used for the preparation of scaffolds made of polyester nanoparticles [76]. For that, particle suspensions were just placed into the mold and gelled. Such systems formed more or less stable 3D porous materials (Figure 6), in which nanoparticles were linked together into micrometer-scale ringlike structures. However, the diameter of the pores was less than 10 µm and could not be considered sufficient for effective cell ingrowth.

The molding process is a straightforward method for achieving a desired macroscopic geometry. However, it must be combined with another technique to control pore size. Therefore, for effective scaffold fabrication, molding is often integrated with methods like sintering, templating, and cryogelation, which are discussed in the following subsections.

3.2.2. Templating

Various templates can be applied to form scaffolds of diverse geometry. In contrast to molding, templating can allow control not only of material shape, but also of its porosity. Based on this, templating techniques can be classified as either external templating, which controls both the overall material shape and its internal pore structure, or internal templating, which is used specifically to engineer the porous architecture.

External Templating Approaches

As an example of an external templating approach, the application of highly porous polyurethane (PU) foam with interconnected, open, large pores can be considered [122]. This foam was used as a template to prepare an HA-based scaffold for bone tissue engineering. In this process, HA nanoparticles (HA NPs) were suspended in a poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) aqueous solution (Figure 7II(a)), and the suspension was infused into the PU sponge (Figure 7II(b,c)). The resulting matrix was subsequently dried and sintered at 1100 °C, yielding a highly porous scaffold with pore diameters of 400–600 µm (Figure 7II(d)). This “replication method” produces a porous structure that closely resembles the architecture of the foam template [123]. The technique fundamentally involves the penetration of a particle suspension into the pores of the template, followed by the destruction of the template and sintering of the particles. While excellent porosity can be achieved, this method is primarily suitable for inorganic particles like HA rather than polymeric ones.

Internal Templating Approaches

For assembling organic particles into porous matrices with controlled porosity, emulsion templating is particularly useful. The technique generally involves two main steps: (1) the preparation of an emulsion composed of at least two immiscible liquids, where the internal phase is dispersed in the continuous phase (Figure 7III(a,b)), and (2) the solidification of the continuous phase of the emulsion [124]. The droplets of the dispersed phase act as pore templates, which are removed after solidification to create a porous matrix (Figure 7III(c)). These biphasic emulsion systems can be either water-in-oil (w/o) or oil-in-water (o/w) depending on the polymer in the continuous phase. The solidification of the continuous phase often occurs due to polymerization. When the volume of the dispersed phase is very high, the method is called high internal phase emulsion (HIPE) polymerization and results in a highly porous polyHIPE foam [125].

A critical aspect of this approach is the stabilization of the high internal phase content, which enables the production of microcellular structures with large pore sizes (up to 1 mm). Interestingly, such an emulsion can be stabilized as a Pickering emulsion using solid particles as surfactants [126]. In these systems, pore size can be adjusted by varying the particle concentration. The stabilizing particles concentrate at the pore interfaces and can significantly influence the final scaffold’s properties.

Recently, Yuan et al. used gelatin microspheres, obtained by water-in-oil emulsion, as an internal template for a porous scaffold [127]. The scaffold was prepared according to the following procedure. First, gelatin droplets were formed in an oil phase. These droplets were then solidified into gelatin microspheres using genipin, a low-molecular-weight crosslinking agent. Second, a macromolecular crosslinker, dialdehyde amylose, was used to cluster the microspheres together through covalent cross-linking. Finally, the material was washed to remove unreacted gelatin from the microsphere interiors. Critically, the pore size was directly governed by the size of the gelatin microspheres. Although the final scaffold was not particulate in nature, the size and spatial organization of the microspheres were undoubtedly crucial in determining its overall architecture.

Recent advancements, such as a rapidly curable, biocompatible polyHIPE foam [128] have enabled the incorporation of porous, growth-factor-loaded microspheres into its structure [129]. This progress indicates that rapid in situ porous polymerization of the continuous phase is emerging as a key fabrication strategy. This is further supported by work on functionalized microspheres for injectable scaffolds [130], and the development of fast-curing emulsions using click chemistry [131].

Templating is an effective technique for proof-of-concept studies, where achieving a highly specific and ordered macro-architecture is the main goal. It offers effective control over pore size and shape, compared to random packing methods. However, due to its complexity, harsh post-processing, and inability to directly create cell-laden scaffolds, it may not be suitable for many advanced tissue engineering applications that require bioactivity, scalability, and the creation of complex hierarchical structures. For these applications, other methods, such as cryogelation, electrospinning, and 3D bioprinting, may be preferred, as they provide a more direct and biocompatible route to creating functional scaffolds.

3.2.3. Cryogelation

Cryogelation is a process that induces the gelation of a particle suspension under frozen conditions. In this method, the solvent (usually water) freezes (Figure 7IV(a,b)), forming a network of ice crystals that acts as a porogen. These growing crystals exclude and concentrate dissolved polymers or suspended particles into the interstitial, unfrozen liquid micro-phase between them (Figure 7IV(b)). Subsequent sublimation (freeze-drying) or thawing removes the ice crystals, yielding a highly porous, monolithic network (Figure 7IV(c)). This technique can be applied to suspensions of pre-formed particles, e.g., polymer microspheres, ceramic granules, cellulose nanocrystals, etc., to create supermacroporous sponge-like architecture with large, interconnected pores (typically 10–200 µm). The particles are not just physically packed together. During freezing, they are concentrated in the unfrozen liquid micro-phase between ice crystals. If the particles possess surface functionality or a small amount of binder polymer is present, they become permanently fused at their contact points upon solvent sublimation. This process transforms loose particles into a robust, monolithic structure. The interparticle bonding responsible for this fusion can be either covalent cross-linking or physical interactions.

One of the first and most classical studies in this area described a one-step method for the cryostructuration of soft particles [132]. Pre-synthesized microgel particles (e.g., PNIPAAm) were dispersed in an aqueous medium at a specified concentration (typically 5 wt%). The particle suspension was cooled in an ice bath, and a chemical cross-linking agent was then added and homogeneously distributed throughout the cooled suspension. The mixture was transferred to molds and subjected to controlled freezing (e.g., −12 °C) for a prolonged period (often overnight) to facilitate cross-linking within the unfrozen micro-phase. Finally, the samples were thawed and washed to remove any residual cross-linker and unintegrated particles.

The versatility of cryogelation is demonstrated by its application to various materials. For instance, magnetically responsive gelatin cryogels have been fabricated from a suspension containing 4 wt% gelatin and 5 wt% magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles. In that case, the alkaline co-precipitation of Fe2+ and Fe3+ salts with NaOH yielded magnetite crystals with an average core diameter of 10 nm. Immediately after precipitation, the particles were coated with a terpolymer shell composed of PEG, styrene, and N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-methacrylamide (DMAPM), which increased the hydrodynamic radius to approximately 200 nm and provided amine-rich surface groups for subsequent coupling. Prior to gel formation, both the functionalized particles and gelatin were pre-activated with NHS/EDC chemistry. The cryogelation protocol began by thoroughly dispersing the magnetic nanoparticle suspension into the gelatin solution in 0.1 M acetic acid at room temperature; the mixture was held for 2 h to ensure complete infiltration of the polymer shell by gelatin chains. The sol was then directionally frozen in a two-step regime (−20 °C followed by −80 °C) and freeze-dried. The resulting macroporous monoliths were further cross-linked and washed to yield the final scaffold.

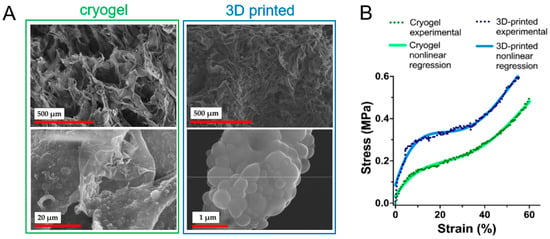

In a more recent example, cryogelation was used to organize methacrylate-functionalized PLA nanoparticles and methacrylate-functionalized cellulose nanocrystals into supermacroporous materials [114]. Surface modification enabled the particles to undergo free-radical cross-linking in the unfrozen micro-phase, initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) and accelerated by tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA). The precooled suspension of modified nanoparticles and reagents was mixed, transferred to a mold, and frozen at −13 °C for 24 h. The resulting cryogel was then thawed and thoroughly washed.

Another significant study demonstrated the cryostructuring of silica particle–silk fibroin composites without a covalent cross-linker [133]. In this work, mesoporous silica particles were dispersed in deionized water using sonication to achieve a homogeneous suspension. The resulting suspension was then mixed with a silk fibroin solution to form a stable hybrid. This mixture was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently held at −20 °C to allow for controlled ice crystal growth, which defined the macroporous architecture. To induce physical cross-linking of the silk fibroin, the frozen construct was treated with cold methanol at −20 °C for 24 h, facilitating a conformational transition to β-sheet structures. The scaffold was then thawed at room temperature, allowing the ice crystals to melt and reveal the interconnected pore network, and finally washed to remove residual methanol.

When considering cryogelation for fabricating particle-based scaffolds, it is crucial to recognize that the final pore architecture is dictated by the morphology of the ice crystals, which depends on several key parameters: freezing rate, freezing direction, particle concentration, and size. Slower freezing rates generally produce larger ice crystals and consequently larger pores, while unidirectional freezing creates aligned, channel-like pores [134]. Notably, the overall shape of the cryogel is determined by the mold in which it is frozen. Thus, it is excellent for creating simple blocks, cylinders, or sheets, but it cannot easily create complex, predefined internal architectures.

3.2.4. Electrospinning and Electrospraying

Beyond self-assembly and templating, instrumental techniques like electrospinning and electrospraying offer powerful routes for creating particle-rich scaffolds. Electrospinning is widely used to fabricate nanofibrous scaffolds that mimic the native ECM [135]. A significant advancement in this field has been the incorporation of functional particles into these fibers, creating multifunctional biomaterials that combine structural benefits with enhanced bioactive properties (Figure 8) [136].

The electrospinning process involves several critical parameters, such as voltage (typically 10–30 kV), flow rate (0.1–2.0 mL/h), and collector distance (10–25 cm), that directly influence fiber formation and particle incorporation [137]. These parameters must be optimized for each polymer–particle system to achieve uniform fiber formation and prevent particle aggregation.

Recent studies have demonstrated the successful incorporation of cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2-NPs) for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [138], zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) for osteogenic applications [139], and titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) for wound healing [138].

Beyond nanoparticles, researchers have incorporated microparticles and composite particles. For instance, hyaluronic acid–chitosan (HA-CS) nanoparticles have been successfully electrospun with poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and gelatin fibers [140]. Silica nanoparticles associated with DNA have been used for gene delivery applications [141]. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) have been incorporated into collagen scaffolds for magnetic stimulation applications [142].

Advanced electrospinning methodologies enable the fabrication of complex scaffolds. Coaxial electrospinning has been employed to create core–shell nanofibers with controlled particle distribution [143]. For example, Zhao et al. designed a new biomimetic bone scaffold using an electrospun PCL/collagen/HA shell and a core of freeze-dried collagen with icariin-loaded chitosan microspheres [144]. This drug-loaded 3D scaffold supports excellent cell attachment in vitro and has promoted abundant new bone formation in in vivo studies. Other techniques, such as multi-needle electrospinning systems, allow for the creation of 3D scaffolds with enhanced structural complexity [135]. Blend electrospinning involves the direct mixing of particles with polymer solutions before spinning, while surface modification techniques allow for post-spinning particle attachment [140].

It is important to note that in all these examples, the particles are incorporated alongside fiber-forming polymers, which provide the structural integrity for the scaffold. Electrospinning itself is not designed to create scaffolds from discrete particles alone. Methods such as particulate leaching or sintering are more suitable for fabricating purely particle-based scaffolds.

Besides electrospinning, electrospraying can also be applied to form particle-rich scaffolds [145]. Electrospray deposition is a solution-based, high-voltage atomization process that converts a dilute polymer or polymer-nonsolvent mixture into a cloud of charged micro- and nano-droplets. Because the liquid viscosity is below the threshold for fiber formation, the jet breaks up into droplets that solidify into particles or hollow microcapsules. The final morphology is governed by formulation and operating conditions. Specifically, a lower polymer concentration or the addition of a volatile non-solvent (e.g., ethanol in chloroform) promotes phase separation and yields particles with nanofibrous surfaces. Elevated humidity enhances vapor-induced phase separation, increasing surface porosity. Higher flow rates produce larger droplets and thus larger particles. The charged particles can be steered electrostatically to accumulate into predefined 2D and 3D architectures. Use of an electrostatic lens further concentrates the particle stream, enabling the direct writing of high-aspect-ratio pillars, continuous lines, and custom micro-architectures without masks or post-processing. The resulting constructs possess multiscale porosity—nanopores in the particle shell, hollow interiors, and inter-particle voids, while the fibrous outer layer offers cell-adhesive topography. Continuous production, solvent evaporation at room temperature, and the ability to switch inks on the fly confer scalability and compositional versatility. Consequently, electrospray deposition provides a straightforward route to particle-rich scaffolds for tissue engineering, drug-delivery microcarriers, porous membranes, functional coatings, and other advanced material systems that benefit from controlled morphology, high surface area, and spatially resolved assembly.

Sequential electrospinning and electrospraying methods have been developed to create bilayer scaffolds, where one layer contains the base polymer and the second layer incorporates particles [146]. This approach allows for controlled release profiles and enhanced functionality.

Although electrospinning and electrospraying are highly versatile techniques, they present distinct challenges, especially when the goal is to create scaffolds from pre-formed particles. The first is incompatibility with aqueous particle suspensions. In fact, many functional particles, such as microgels, are synthesized and stored in aqueous buffers. However, electrospinning typically requires polymer solutions in volatile organic solvents to facilitate fiber formation. The second challenge is the limited control over 3D scaffold architecture, since these techniques commonly produce scaffolds that are inherently dense and sheet-like. The third challenge in creating a scaffold by particle electrospinning or electrospraying is that they typically land and form a loose powder or very weak aggregate held together by weak forces. So, without a binding matrix or a post-processing sintering step, the scaffold lacks structural integrity and falls apart easily.

3.2.5. 3D-Printing

3D-printing or additive manufacturing (AM) has revolutionized tissue engineering by enabling the fabrication of customized scaffolds with precise and complex architectures. A key advantage of AM is its ability to create patient-specific implants based on individual medical image data, offering a tailored fit for the defect site. While many 3D-printed scaffolds are fabricated from polymers, hydrogels, or composites, there is growing interest in particle-based scaffolds constructed solely from micro- or nanoparticles. These structures offer unique benefits, including high surface area, tunable porosity, and enhanced bioactivity [147,148].

The ability of particles to encapsulate various molecules and even cells makes them particularly attractive for 3D printing. Early studies described that using cell-laden microspheres in bioprinting could reduce the required initial cell density while improving the compressive strength of the construct [149,150]. Subsequent studies have described the use of microspheres for the local delivery of drugs such as small molecules [151] and growth factors [152,153]. Particles have also been used as structural support [154], and as sacrificial particles to create interconnected porous networks [155].

Several 3D-printing methods are specially designed for the fabrication of scaffolds from particles: binder jetting, selective laser sintering (SLS)/selective laser melting (SLM), electrophoretic deposition-assisted 3D-printing, and direct ink writing combined with stereolithography. In binder jetting, a liquid binding agent is selectively deposited onto a thin layer of powder, binding the particles together in a layer-by-layer fashion (Figure 8). The types of particles that can be used in this process include ceramics (HA, TCP) [156] and polymers [157]. Binder jetting does not require the application of any support, offers high resolution, and is relatively easily scalable. Processing parameters such as binder concentration, surfactant addition, and layer thickness directly affect printability, pore definition, and the mechanical and biological performance. A significant challenge for this technique, however, is achieving strong interlayer adhesion, and its print resolution is typically in the range of 20–100 µm [158].

SLS and SLM use a laser selectively to sinter or melt powdered particles, fusing them into solid structures [158]. These techniques are compatible with thermoplastics (PLLA, PCL) [159], metals, and ceramic particles [160], and can produce scaffolds with robust, strong mechanical properties without the need for binders. A significant disadvantage of this method is the use of high temperatures, especially the instant heat from the laser, which limits the number of biocompatible materials that can be used and makes the incorporation of temperature-sensitive bioactive molecules (e.g., growth factors, drugs) impossible [161]. Furthermore, SLS/SLM typically works better with particle sizes of around 100 µm.

Electrophoretic deposition-assisted 3D-printing uses electric fields to direct charged particles onto a substrate in a layer-by-layer manner [162]. For example, nanocrystalline HA and bioactive glass particles were used to form materials with this process. This approach allows fine control over particle deposition without thermal degradation. All printing operations occur at room temperature, so temperature-sensitive additives such as growth factors or drugs could, in principle, be incorporated without degradation. A significant advantage of this method over other techniques is that it can utilize very small ceramic [163] or polymer [164] particles. However, this method is primarily useful for creating thin-film coatings and gradient structures rather than large, bulky implants. Limitations include the need for a specialized membrane support and issues with reproducibility. In solvents with high permittivity like water, strong electric field gradients can cause fluid turbulence, disturbing particle deposition and leading to poor resolution and undefined shapes.

In addition to the classical methods discussed above, particles can also be organized into macroporous matrices with the application of conventional extrusion and direct ink writing methods. Recently, Klar et al. employed an extrusion-based additive manufacturing platform to implement the “3D-McMap” protocol, in which the printable feedstock was a highly concentrated suspension of monodisperse microspheres [165]. The bio-ink consisted of 200 ± 10 µm PLA or PLGA microparticles dispersed in a 3% aqueous carboxymethyl-cellulose solution. During printing, the syringe barrel was cooled to 4 °C to retard drying, whereas the build stage was maintained at 50–60 °C to accelerate solvent removal from the deposited filaments.

Deposition was interrupted after every two layers for 10 s to allow partial drying. An aluminum foil served as a sacrificial substrate, and extrusion pressure was manually adjusted to maintain a steady flow and the completed constructs were exposed to dichloromethane vapor to sinter the particle contacts and consolidate the scaffold. This approach yields scaffolds composed almost entirely of microspheres, endowing the printed filaments with intrinsic microporosity and providing a high local loading capacity for bioactive agents; it also permits spatially resolved placement of multiple particle populations and, after vapor sintering, affords compressive strengths of more than twice those of its unsintered counterparts. However, the current implementation of this method is still labor-intensive and sensitive to both environmental and process variables. The sticky, particle-rich ink demands continual operator intervention for pressure adjustment, nozzle cleaning, and layer-pause timing. It is also prone to clogging and cannot be deposited as isolated dots or segments without “stringing”.

The outstanding feature of 3D printing is the ability to exercise spatial control over the distribution of mechanical properties and biological signals within a fabricated structure. The connective tissues often possess various gradients, which should be maintained by scaffolds. In this context, particle-based systems have been demonstrated to be highly useful building blocks for constructing such graded architectures [166]. For example, Singh et al. produced uniform PLGA microspheres using the precision particle fabrication technique and either left them blank or loaded them with the model dyes rhodamine B or fluorescein to mimic distinct bioactive cues. For scaffold construction, two separate suspensions of these microspheres were placed into syringes mounted on programmable syringe pumps and delivered into a cylindrical glass mold. By imposing user-defined flow-rate profiles on each pump, the relative proportion of the two microsphere types entering the mold could be varied in real time. This process enabled the fabrication of scaffolds with bilayer, multilayer, or continuously smooth graded architectures. Once the desired packing profile had been established, the settled microspheres were soaked in ethanol for 50 min. Ethanol induced surface plasticization of the PLGA, creating a thin interconnecting film that fused neighboring particles into a continuous, highly porous matrix. The construct was finally freeze-dried to remove residual solvent and stabilize the three-dimensional scaffold.

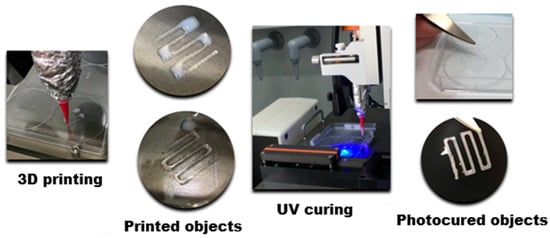

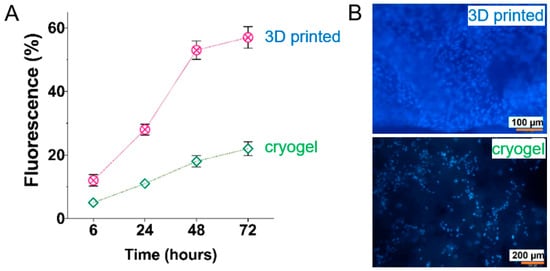

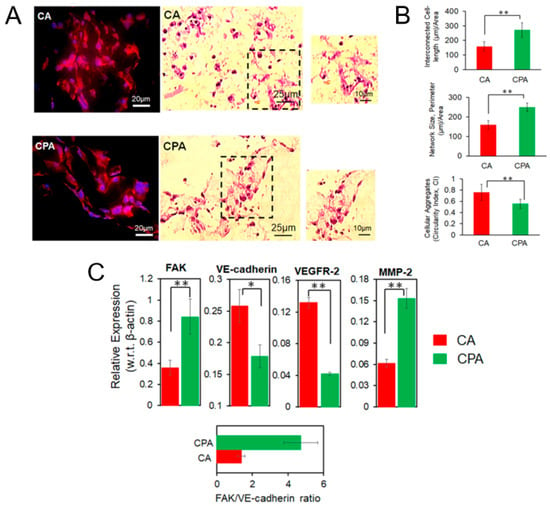

The above-mentioned protocol could be realized via a hybrid 3D printing technique combining direct ink writing (DIW) and stereolithography (SLA) [114]. For example, Leonovich et al. used an aqueous suspension of methacrylated PLA and CNC particles (PLA-MA and CNC-MA) as “ink” [114]. The suspension was also supplemented with a macromolecular cross-linker, GelMA, which acted as a “molecular glue”. Its addition significantly enhanced the formation of a stable 3D network between the particles during UV-curing. For printing, the particle-based bioink was loaded into a syringe and extruded through a fine nozzle (0.254 mm diameter) onto a platform (Figure 9). This step deposited the material layer-by-layer according to a pre-designed CAD model, defining the scaffold’s macro-architecture. After each layer was deposited, the printed layer was immediately irradiated by a UV light (365 nm). This UV exposure triggered a free-radical polymerization that cross-linked the particles and GelMA via their methacrylate groups. This in situ curing solidified the layer, fixing the particles in place and providing the scaffold with mechanical integrity. The discussed study employed a single syringe extruder for the particle mixture (PLA-MA and CNC-MA) [114]. However, using two separate syringes, each containing a different particle type, is a route for creating gradient scaffolds.

Figure 9.

Scheme for the production of scaffolds from a mixture of methacrylated polymer nanoparticles via 3D-printing based on a combination of direct ink writing and stereolithography.

Granular hydrogels are extremely interesting materials within the context of scaffold fabrication via 3D printing. Microgels exhibit excellent shear-thinning behavior that makes them ideal for extrusion-based 3D printing. A key advantage of cross-linked microgel systems is their ability to create self-supporting structures immediately after printing. It was demonstrated that the reversible dynamic covalent cross-links in granular hydrogels provide self-healing properties that confer stability after extrusion without any additional cross-linking [102]. This eliminates the need for post-printing curing steps that are often required with many bioinks. Authors successfully printed grids, hexagons, and lines and reported that the geometric accuracy of the printed structures was slightly improved when using 1 mm extrusion tips relative to 0.4 mm. The printed structures maintained their shape when a granular hydrogel was printed as a 5 mm cylinder tube with 50 layers. This tube demonstrated elasticity and mechanical stability without post-printing cross-linking.

Another study presented an advanced triple-click chemistry approach for 3D printing. The authors applied gelatin–norbornene–carbohydrazide microgels that could be dynamically stiffened and annealed them into granular hydrogels through three orthogonal reactions. This allows for precise control over mechanical properties both during and after printing [117].

Despite their promise, several challenges persist in the 3D printing of particle-based scaffolds. A primary issue is particle agglomeration within the bio-ink, which can clog nozzles and affect printability. Another significant issue is weak interparticle bonding; unbound particles are prone to collapse. To overcome this, a post-printing consolidation step, such as thermal sintering, solvent vapor fusion, or chemical cross-linking, is frequently necessary to ensure structural integrity.

Despite these limitations, 3D-printed particulate scaffolds offer several promising perspectives for future advancement. A key perspective is multi-material printing, which enables the spatial integration of different functional particles, for instance, combining growth factor-releasing microspheres with structurally reinforcing granules. Another frontier is in situ bioprinting, which involves depositing scaffolds directly into anatomical defects using bioactive particles. The development of advanced stimuli-responsive particles for direct ink writing, which can solidify or modify their properties upon exposure to physiological cues (e.g., temperature, pH, or light), is particularly promising for realizing these advanced applications [58,167].

4. Properties of Particle-Based Scaffolds

4.1. Mechanical Properties and Morphology

Particle-based scaffolds show considerable promise for tissue engineering applications due to their capacity to form unique structures, create gradients, and deliver bioactive agents. However, their practical utility is governed by critical mechanical and morphological properties. A primary challenge is the balance between mechanical strength and the high porosity required for nutrient diffusion, vascularization, and cell migration. Furthermore, the particle surface texture directly influences cellular behavior; while irregular surfaces can enhance cell attachment, they may also provoke undesirable inflammatory responses. Finally, a uniform particle distribution is crucial for consistent scaffold performance and avoiding points of weakness.

Mechanical properties of scaffolds are very important for their performance and have been addressed by many researchers. This section first reviews literature in which the introduction of particles helped to tune the mechanics of the scaffolds. For instance, Chowdhury et al. investigated porous ceramic scaffolds fabricated from TCP, HA, and a mixed HA-TCP (50:50 wt%) composite using the polyurethane sponge replication method [168]. This technique produced particle-based scaffolds, whose architecture was a direct 3D replica of the original sponge, yielding a highly interconnected macroporous network with pore sizes exceeding 250 µm. Nanoindentation tests (to 600 nm depth) revealed that the composite HA + TCP scaffolds exhibited significantly superior mechanical properties compared to those made of pure TCP. The Young’s modulus of the composite was 10.3 GPa versus 1.5 GPa of pure TCP. Similarly, the hardness values of the composite scaffold were 240 MPa compared to 21 MPa for TCP. These results demonstrate that incorporating HA substantially enhances the mechanical performance of biodegradable scaffolds while preserving the interconnected porous architecture essential for bone tissue engineering.

The introduction of silica-based particulate materials, namely bioactive glass 4555, diatomaceous earth, and biosilica into marine-derived collagen materials has improved the compressive modulus of scaffolds. The scaffolds with incorporated particles also exhibited decreased water uptake compared to pure collagen scaffolds, leading to more stable and cohesive structures [37].

A recent study demonstrated that adding nano-CaP particles to AP40mod glass–ceramic powder fundamentally alters the scaffold properties [71]. The nanoparticles inhibit densification during sintering, increasing porosity (70% vs. 60%) and creating a finer, smoother surface morphology compared to the pure, coarse AP40mod. The nanoparticles also promote the β-TCP-to-HA transformation, enhancing the scaffold’s bioactivity. However, nanopowder content exceeding 10 wt% impairs flowability and printability, requiring higher binder saturation (110%) and limiting processability. These findings confirm that even small amounts of nano-CaP significantly modify sinterability, microstructure, and printing behavior, enabling the use of bioactive calcium phosphate in binder jetting, albeit with a compromise between enhanced porosity and manufacturability.

Ceramic nanoparticles are also well-known for enhancing the mechanical properties of polymer scaffolds. For instance, a study on electrospun PLA/HA composite scaffolds demonstrated this effect clearly [169]. The incorporation of HA significantly increased the elastic modulus, with nanoHA providing superior reinforcement—a 140–170% increase—compared to a 70% increase with microHA. The effect on tensile strength, however, depended on fiber alignment: it decreased by 68–70% in random mats but increased in aligned mats by ~130% with µHA and ~84% with nHA. All composites showed increased brittleness, with elongation at break reduced by 70–85%. Morphologically, the scaffolds formed porous nanofibrous networks. The aligned fibers were 10–20% thinner and more uniform than random fibers. NanoHA produced smoother fibers with well-dispersed small agglomerates (<4 µm), while microHA formed large irregular agglomerates (5–20 µm) that created stress concentration points, reducing reinforcement efficiency. Fiber alignment amplified HA’s benefits, with aligned composites maintaining strength while achieving higher stiffness. The optimal formulation, a PLA containing 20% nHA, combined maximum stiffness with a favorable morphology for bone tissue engineering.

However, it should be considered that the introduction of particles can very often result in the formation of fragile structures. For example, in PLGA/bioactive glass composite scaffolds, increasing the bioactive glass content from 20 to 50% led to high porosity (73.7–76.1%) up to 200 μm but also caused severe mechanical fragility that precluded quantitative testing [78]. This particle-based composition directly dictated the scaffold’s properties: higher bioactive glass content disrupted polymer continuity, creating irregular particles that reduced sintering quality and caused mechanical fragility.