Development of 3D Printing Filament from Poly(Lactic Acid) and Cassava Pulp Composite with Epoxy Compatibilizer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Cassava Pulp for Starch Removal

2.3. Alkali Treatment of Cassava Pulp

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.5. Tensile Properties

2.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.7. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.8. Contact Angle

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.10. Melt Flow Index (MFI)

2.11. Folding Endurance

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. FTIR Analysis of Fiber

3.2. Effect of Fiber Size on the Mechanical Properties of PLA/CP Composites

3.2.1. Mechanical Properties of PLA/CP Composites

3.2.2. Morphology of PLA/CP Composite

3.3. Effect of Epoxy Resin Content on PLA/CP/Epoxy Resin Composite Properties

3.3.1. FTIR Analysis of PLA/CP/Epoxy Composite

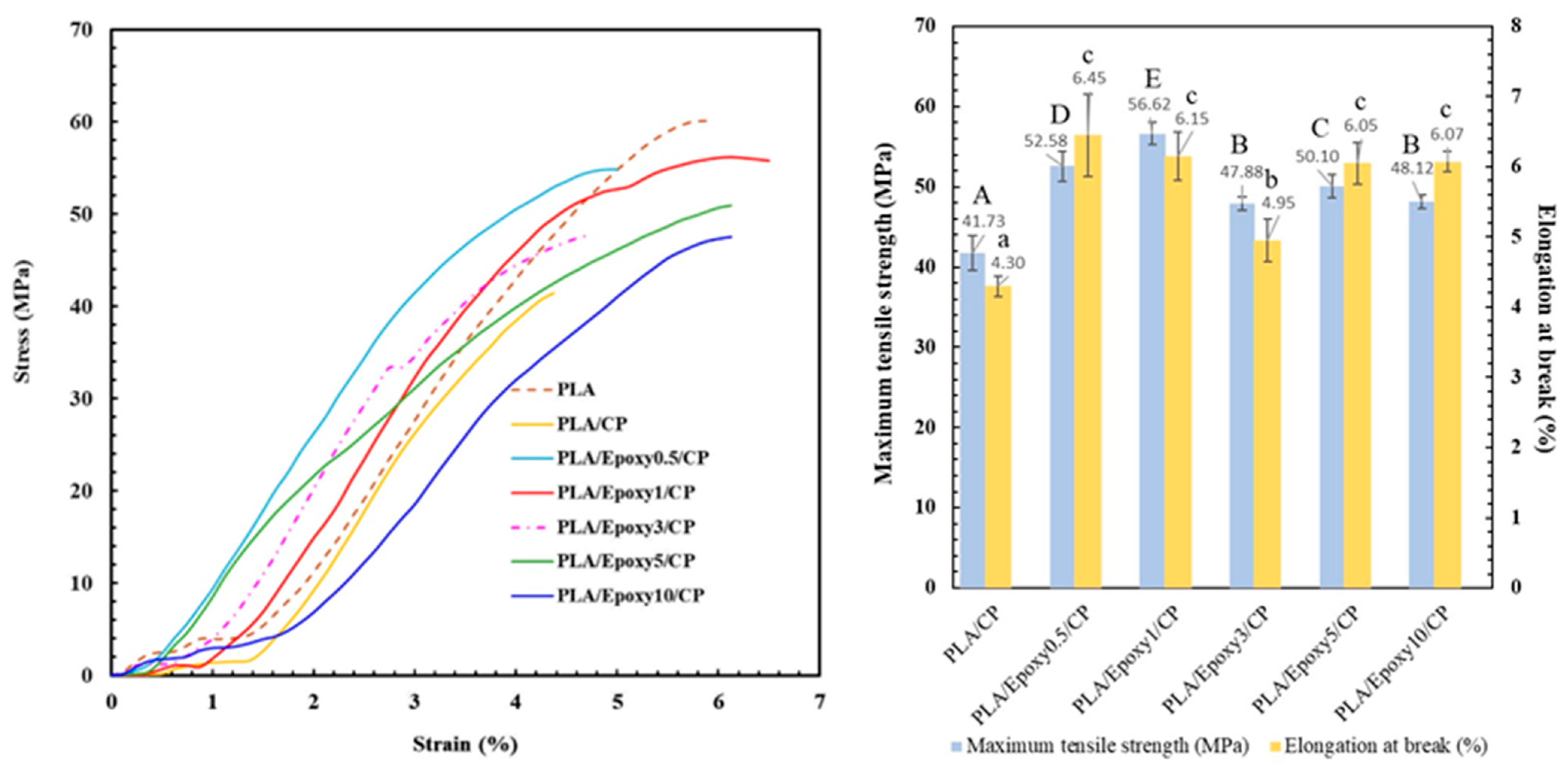

3.3.2. Mechanical Properties of PLA/CP/Epoxy Resin Composite

3.3.3. Contact Angle of PLA/CP/Epoxy Composite

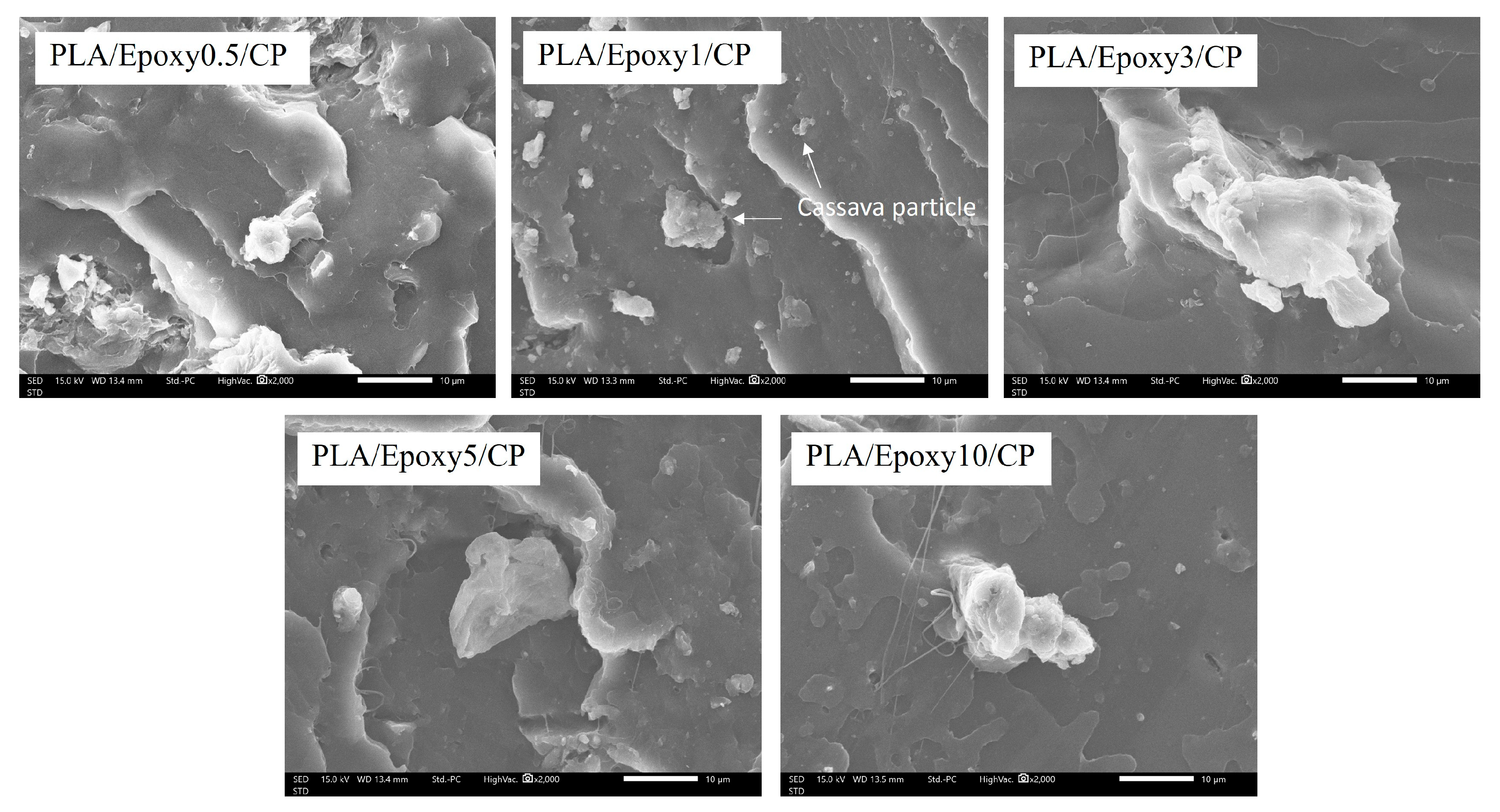

3.3.4. Morphology

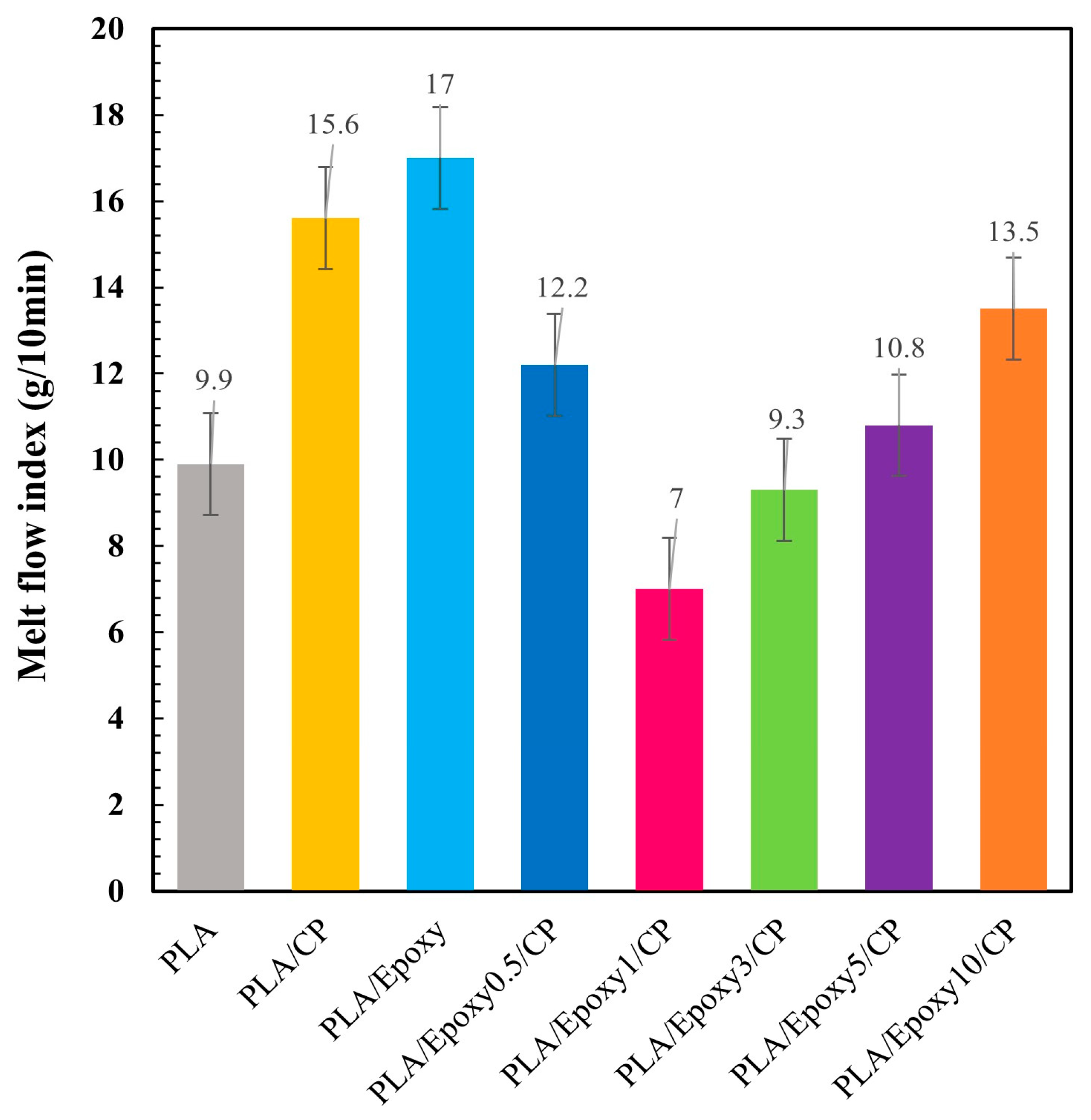

3.3.5. Melt Flow Index

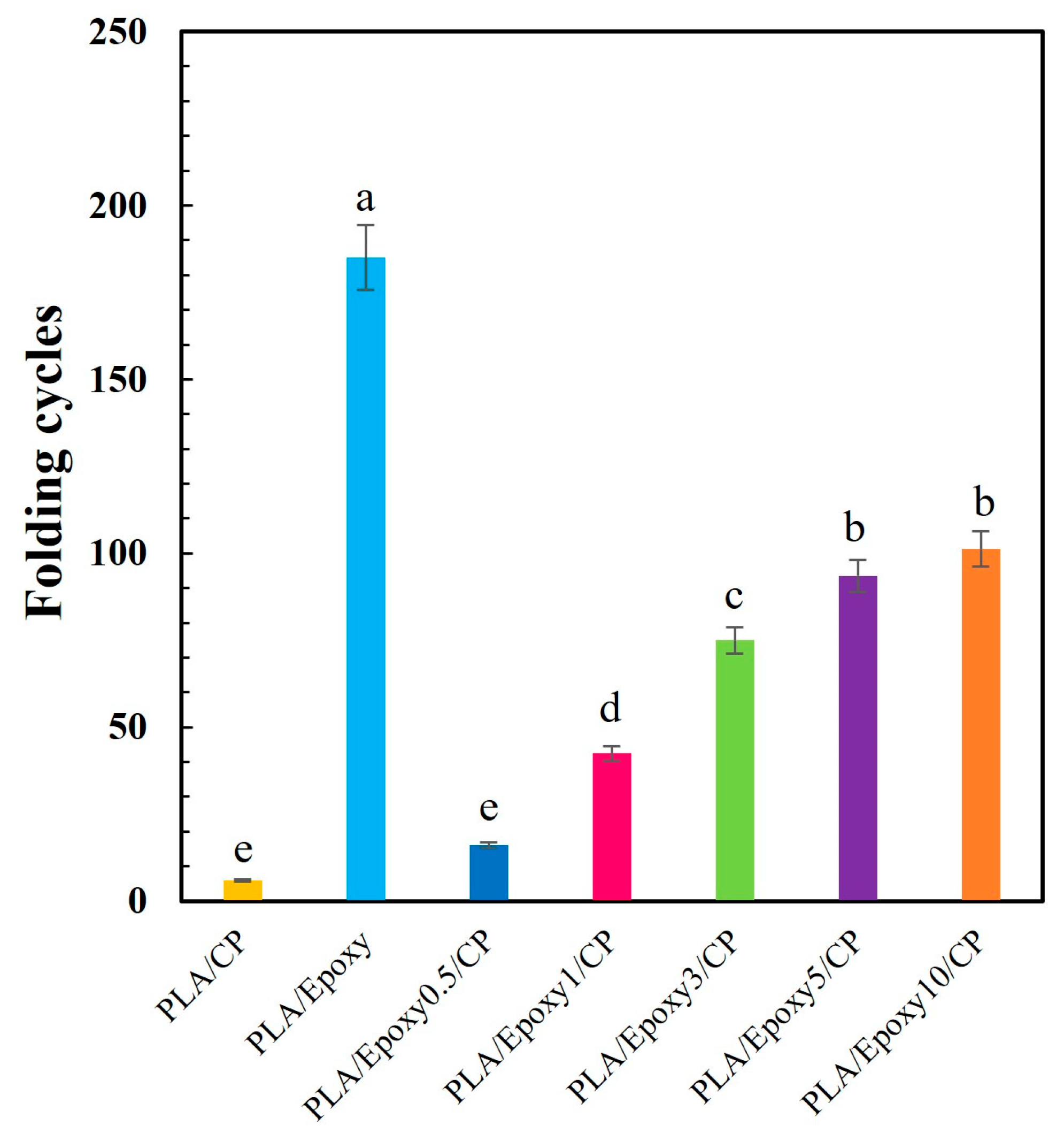

3.3.6. Folding Endurance Test

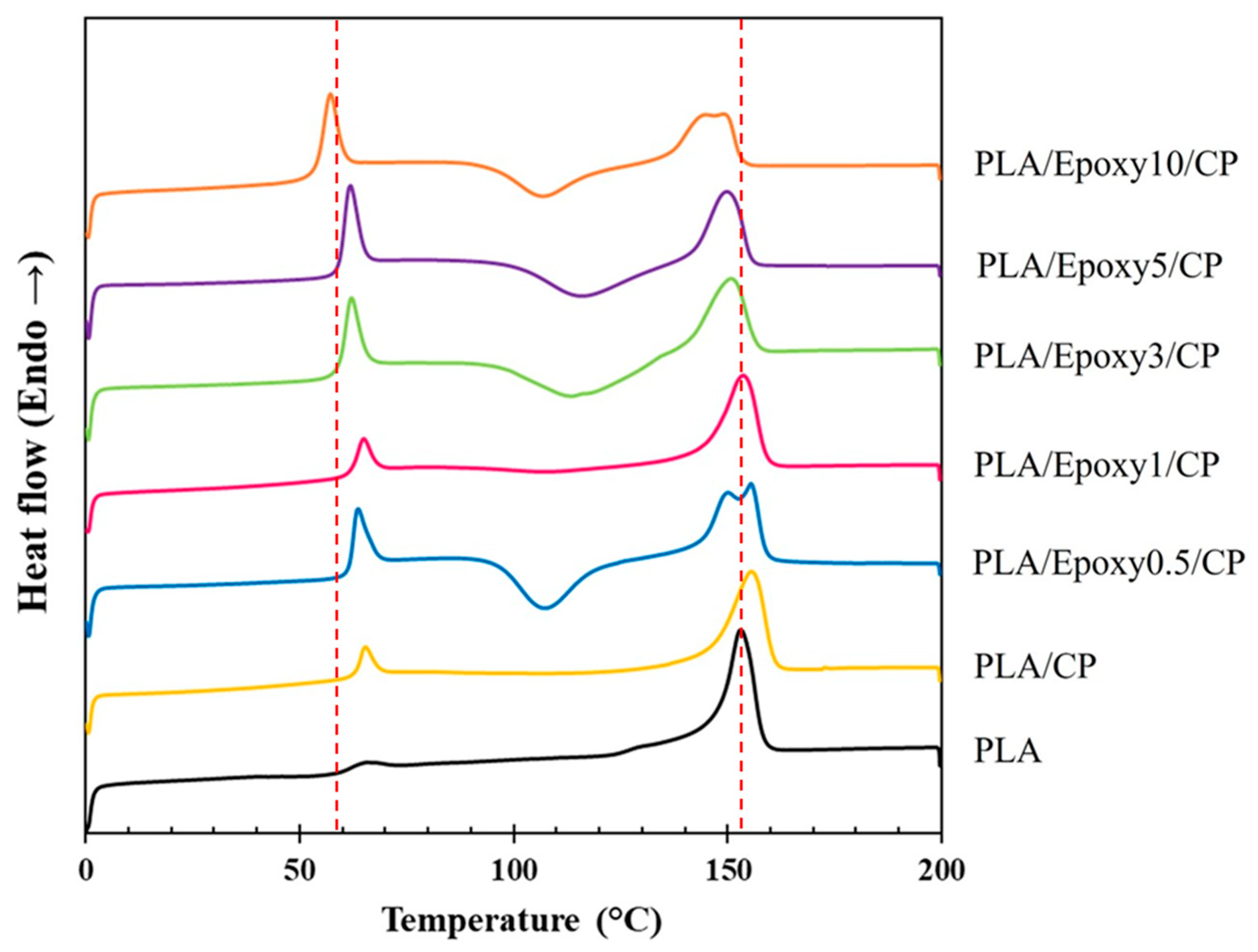

3.3.7. Thermal Properties

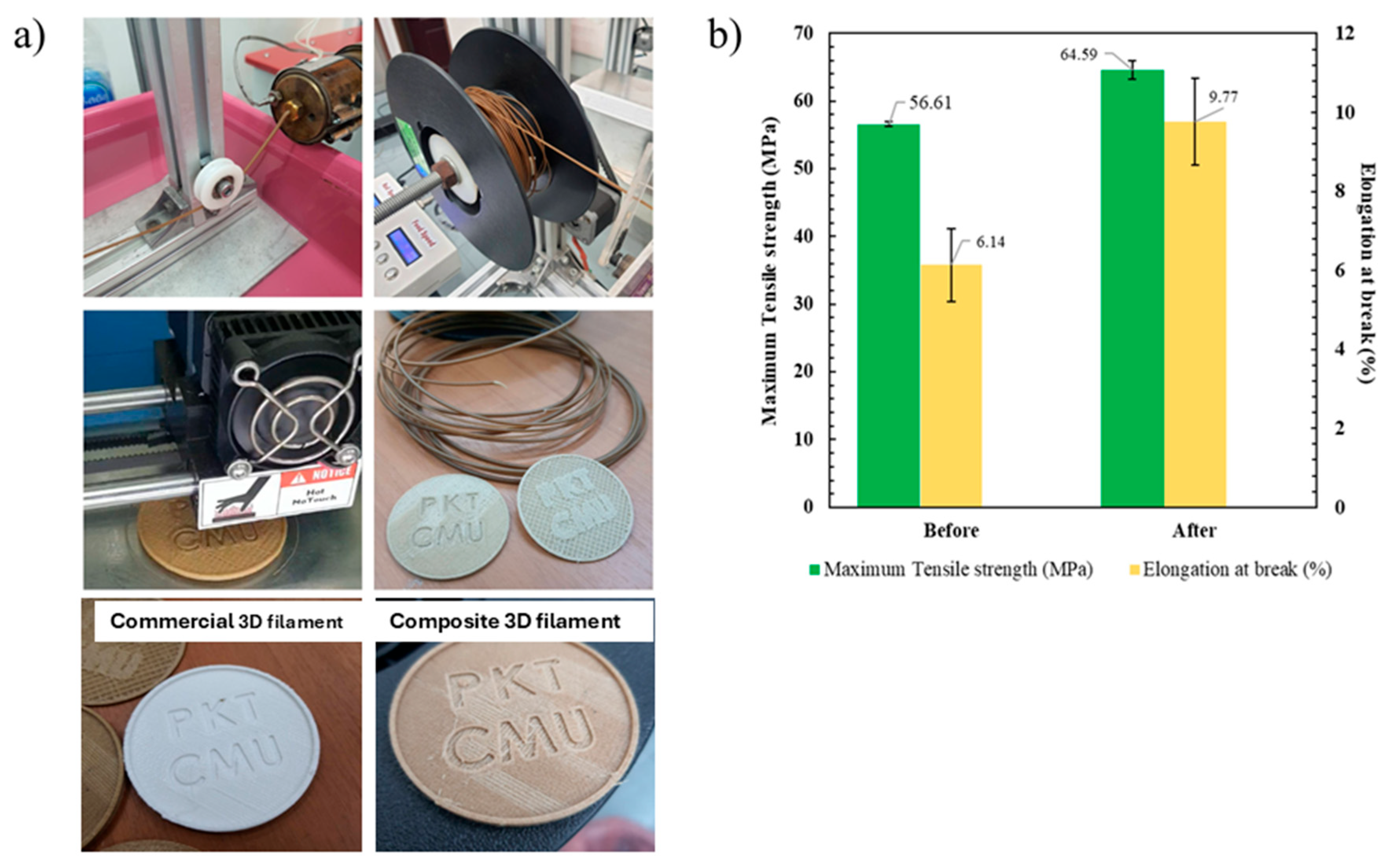

3.3.8. Three-Dimensional Filament Derived from PLA/Epoxy1/CP

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Hassan, M.M.; Tucker, N.; Le Guen, M.J. Thermal, mechanical and viscoelastic properties of citric acid-crosslinked starch/cellulose composite foams. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, M.; Garg, N.; Chand, P.; Jakhete, A. Bio-based bioplastics: Current and future developments. In Valorization of Biomass to Bioproducts; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 475–504. [Google Scholar]

- Arjmandi, R.; Hassan, A.; Zakaria, Z. Polylactic Acid Green Nanocomposites for Automotive Applications. In Green Biocomposites; Green Energy and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Haafiz, M.K.M.; Hassan, A.; Arjmandi, R.; Marliana, M.M.; Fazita, M.R.N. Exploring the Potentials of Nanocellulose Whiskers Derived from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch on the Development of Polylactid Acid Based Green Nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2016, 24, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonoobi, M.; Harun, J.; Mathew, A.P.; Oksman, K. Mechanical properties of cellulose nanofiber (CNF) reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) prepared by twin screw extrusion. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 1742–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorokhoda, V.; Semeniuk, I.; Peretyatko, T.; Kochubei, V.; Ivanukh, O.; Melnyk, Y.; Stetsyshyn, Y. Biodegradation of polyhydroxybutyrate, polylactide, and their Blends by microorganisms, including Antarctic Species: Insights from weight Loss, XRD, and thermal Studies. Polymers 2025, 17, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.M.; Kallingal, A.; Suresh, A.M.; Mahapatra, D.K.; Hasanin, M.S.; Haponiuk, J.; Thomas, S. 3D printing of polylactic acid: Recent advances and opportunities. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, G.; Zhu, P.; Gao, C. Recent Progress on 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid and Its Applications in Bone Repair. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 22, 1901065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.M.E.; Khatri, N.R.; Kulkarni, N.; Egan, P.F. Polymer 3D Printing Review: Materials, Process, and Design Strategies for Medical Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcharamongkol, T.; Khaopueak, P.; Seesuea, C.; Wechakorn, K. Green hydrothermal synthesis of multifunctional carbon dots from cassava pulps for metal sensing, antioxidant, and mercury detoxification in plants. Carbon. Resour. Convers. 2024, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullanun, P.; Yoksan, R. Morphological characteristics and properties of TPS/PLA/cassava pulp biocomposites. Polym. Test. 2020, 88, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Surface modifications of natural fibers and performance of the resulting biocomposites: An overview. Compos. Interface. 2001, 8, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsissou, R.; Seghiri, R.; Benzekri, Z.; Hilali, M.; Rafik, M.; Elharfi, A. Polymer composite materials: A comprehensive review. Compos. Struct. 2021, 262, 113640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; da Silva, M.A.; dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-based plasticizers and biopolymer films: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeman, R.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Van Wachem, P.; Van Luyn, M.; Hendriks, M.; Cahalan, P.; Feijen, J. Crosslinking and modification of dermal sheep collagen using 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Off. J. Soc. Biomater. Jpn. Soc. Biomater. Aust. Soc. Biomater. Korean Soc. Biomater. 1999, 46, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustiniani, A.; Ilyas, M.; Indei, T.; Gong, J.P. Relaxation mechanisms in hydrogels with uniaxially oriented lamellar bilayers. Polymer 2023, 267, 125686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1238; Standard Test Method for Melt Flow Rates of Thermoplastics by Extrusion Plastometer. ASTM international: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Panyathip, R.; Witthayapak, M.; Thuephloi, P.; Sukunta, J.; Thipchai, P.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Rachtanapun, P. Characterization of corn husks carboxymethyl cellulose formation using Raman spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 228, 120887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, S.; Chai, G.B. A review of advances in fatigue and life prediction of fiber-reinforced composites. Proc. IMechE. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2012, 227, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, A.H.D.; Chalimah, S.; Primadona, I.; Hanantyo, M.H.G. Physical and chemical properties of corn, cassava, and potato starchs. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 160, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Chakrabarty, D. Isolation of nanocellulose from waste sugarcane bagasse (SCB) and its characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, W.P.F.; Silvério, H.A.; Dantas, N.O.; Pasquini, D. Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from agro-industrial residue–Soy hulls. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 42, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini, H.; Tan, C.P.; Aghlara, A.; Hamid, N.S.; Yusof, S.; Chern, B.H. Influence of pectin and CMC on physical stability, turbidity loss rate, cloudiness and flavor release of orange beverage emulsion during storage. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 73, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, M.; Bairwan, R.D.; Khalil, H.A.; Surya, I.; Mawardi, I.; Ahmad, A.; Yahya, E.B. The Role of Natural Fiber Reinforcement in Thermoplastic Elastomers Biocomposites. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 3061–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thajai, N.; Rachtanapun, P.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Punyodom, W.; Worajittiphon, P.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Leksawasdi, N.; Ross, S.; Jantrawut, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K. Reactive Blending of Modified Thermoplastic Starch Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Poly(butylene succinate) Blending with Epoxy Compatibilizer. Polymers 2023, 15, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Preparation of chitosan/PLA blend micro/nanofibers by electrospinning. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, M.R.; Corcione, C.E.; Giuri, A.; Maggio, M.; Maffezzoli, A.; Guerra, G. Graphene oxide as a catalyst for ring opening reactions in amine crosslinking of epoxy resins. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 23858–23865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiattipornpithak, K.; Thajai, N.; Kanthiya, T.; Rachtanapun, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Rohindra, D.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Sommano, S.R.; Jantanasakulwong, K. Reaction mechanism and mechanical property improvement of poly (lactic acid) reactive blending with epoxy resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanthiya, T.; Kiattipornpithak, K.; Thajai, N.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Rachtanapun, P.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Leksawasdi, N.; Tanadchangsaeng, N.; Sawangrat, C.; Wattanachai, P. Modified poly (lactic acid) epoxy resin using chitosan for reactive blending with epoxidized natural rubber: Analysis of annealing time. Polymers 2022, 14, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-L.; Wu, Z.-H.; Yang, W.; Yang, M.-B. Thermal and mechanical properties of chemical crosslinked polylactide (PLA). Polym. Test. 2008, 27, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.T.; García, S.J.; Cabello, R.; Suay, J.J.; Gracenea, J.J. Effect of plasticizer on the thermal, mechanical, and anticorrosion properties of an epoxy primer. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2005, 2, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laput, O.; Vasenina, I.; Salvadori, M.C.; Savkin, K.; Zuza, D.; Kurzina1, I. Low-temperature plasma treatment of polylactic acid and PLA/HA composite material. Polym. Biopolym. 2019, 54, 11726–11738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gao, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Feng, S.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, P.; Ding, Y. Effect of hydroxyl and carboxyl-functionalized carbon nanotubes on phase morphology, mechanical and dielectric properties of poly (lactide)/poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, D.; Kamo, T. A comprehensive study on the oxidative pyrolysis of epoxy resin from fiber/epoxy composites: Product characteristics and kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Valavala, P.K.; Clancy, T.C.; Wise, K.E.; Odegard, G.M. Molecular modeling of crosslinked epoxy polymers: The effect of crosslink density on thermomechanical properties. Polymer 2011, 52, 2445–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiattipornpithak, K.; Rachtanapun, P.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Jantrawut, P.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Sommano, S.R.; Leksawasdi, N.; Kittikorn, T.; Jantanasakulwong, K. Bamboo Pulp Toughening Poly(Lactic Acid) Composite Using Reactive Epoxy Resin. Polymers 2023, 15, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Functional Groups | Wave Number in the Literature | PLA | Cassava | Epoxy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O–H stretching | 3600–3300 | - | 3447 | - |

| C–H stretching | 2931 | 2946 | 2821 | 3059 |

| C=O stretching | 1740 | 1740 | - | - |

| C=C stretching | 1510, 1609 | - | - | 1510, 1609 |

| –CH3 bending | 1450 | 1450 | - | 1445 |

| C–C stretching | 1175 | 1175 | - | - |

| C–O stretching | 1200–800 | 850 | 1060, 893 | 912 |

| Sample | Tg (°C) | Tc (°C) | Tm (°C) | ∆Hc (J/g) | ∆Hm (J/g) | %X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 62.3 | - | 153.5 | - | 33.8 | 36.1 |

| PLA90/CP10 | 61.1 | - | 156.0 | - | 28.7 | 30.7 |

| PLA/Epoxy0.5/CP | 61.3 | 107.3 | 155.8 | 19.5 | 25.5 | 6.4 |

| PLA/Epoxy1/CP | 61.1 | - | 154.0 | - | 26.5 | 28.3 |

| PLA/Epoxy3/CP | 59.2 | 113.5 | 151.2 | 19.1 | 25.1 | 6.4 |

| PLA/Epoxy5/CP | 58.6 | 116.0 | 150.2 | 17.3 | 18.3 | 1.1 |

| PLA/Epoxy10/CP | 53.7 | 107.0 | 149.3 | 12.1 | 19.4 | 7.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanthiya, T.; Changsuwan, P.; Kiattipornpithak, K.; Rachtanapun, P.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Jantrawut, P.; Tanadchangsaeng, N.; Worajittiphon, P.; Kittikorn, T.; Jantanasakulwong, K. Development of 3D Printing Filament from Poly(Lactic Acid) and Cassava Pulp Composite with Epoxy Compatibilizer. Polymers 2025, 17, 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233228

Kanthiya T, Changsuwan P, Kiattipornpithak K, Rachtanapun P, Thanakkasaranee S, Jantrawut P, Tanadchangsaeng N, Worajittiphon P, Kittikorn T, Jantanasakulwong K. Development of 3D Printing Filament from Poly(Lactic Acid) and Cassava Pulp Composite with Epoxy Compatibilizer. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233228

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanthiya, Thidarat, Pattraporn Changsuwan, Krittameth Kiattipornpithak, Pornchai Rachtanapun, Sarinthip Thanakkasaranee, Pensak Jantrawut, Nuttapol Tanadchangsaeng, Patnarin Worajittiphon, Thorsak Kittikorn, and Kittisak Jantanasakulwong. 2025. "Development of 3D Printing Filament from Poly(Lactic Acid) and Cassava Pulp Composite with Epoxy Compatibilizer" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233228

APA StyleKanthiya, T., Changsuwan, P., Kiattipornpithak, K., Rachtanapun, P., Thanakkasaranee, S., Jantrawut, P., Tanadchangsaeng, N., Worajittiphon, P., Kittikorn, T., & Jantanasakulwong, K. (2025). Development of 3D Printing Filament from Poly(Lactic Acid) and Cassava Pulp Composite with Epoxy Compatibilizer. Polymers, 17(23), 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233228