Effects of Environmental Factors on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Leaf Manuscripts: Natural Aging, Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Light Radiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Simulated Aging Experiment

2.2.1. Temperature Aging Experiment

2.2.2. Humidity Aging Experiment

2.2.3. Light Radiation Aging Experiment

- Ultraviolet (UV) radiation: Conducted in the UV aging chamber, with a radiation wavelength of 340 nm, an irradiance of 1.51 W/m2, and a temperature of 55 °C.

- Visible light: Performed in the environmental test chamber equipped with a ring-shaped white LED light source (64 LED Lights, Yike, Shenzhen, China). The radiation wavelength ranged from 400 to 645 nm, with an output power of 10 W, at 25 °C and 50% RH.

- Infrared (IR) radiation: Performed in the environmental test chamber equipped with a ring-shaped infrared LED light source (HS-RD0, Hongshuo Technology, Hangzhou, China). The radiation wavelength ranged from 800 to 1750 nm, with an output power of 10 W, at 25 °C and 50% RH.

2.3. Flexural Strength Testing

2.4. FT-IR Test

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Natural Aging of Samples

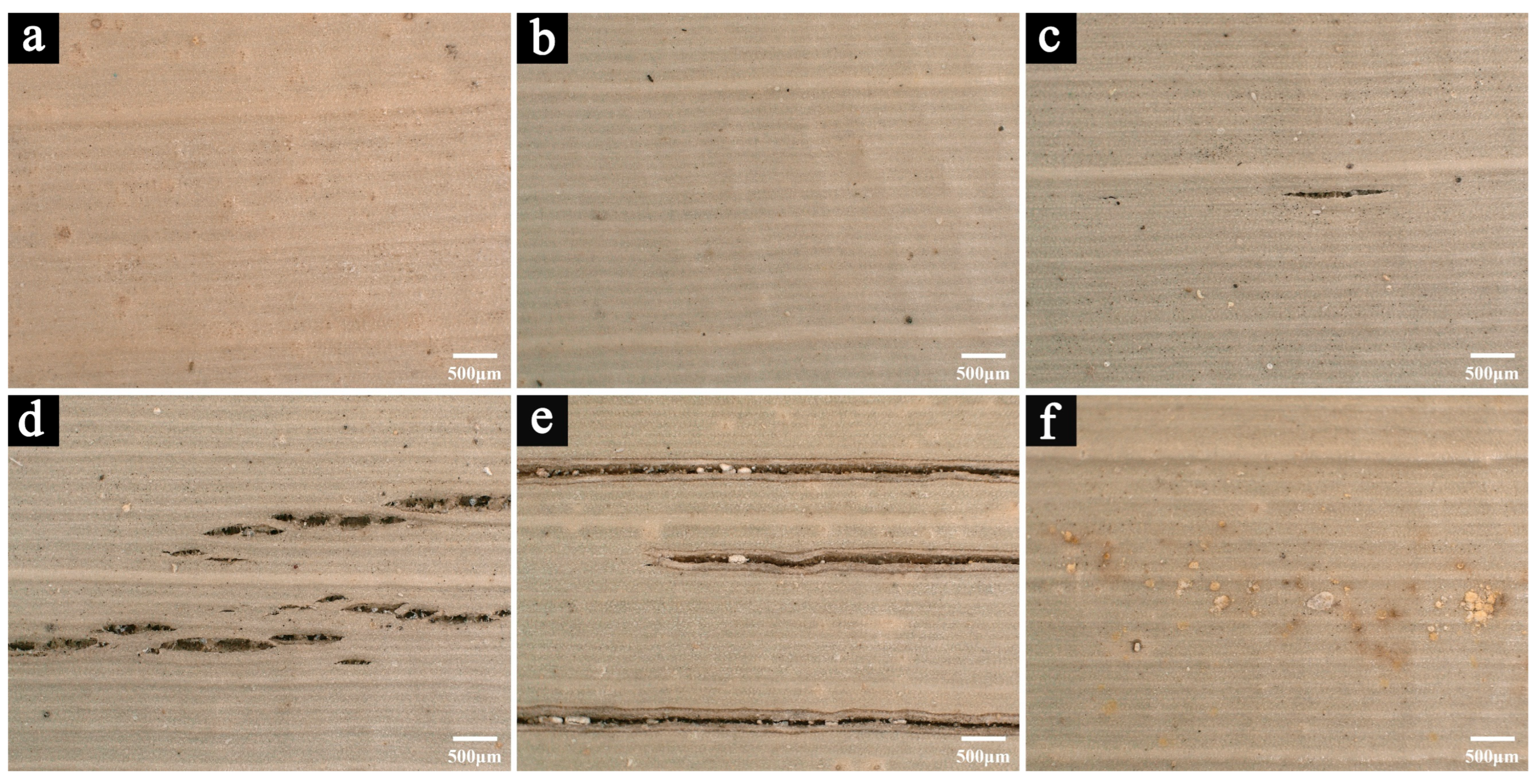

3.1.1. Microscopic Images

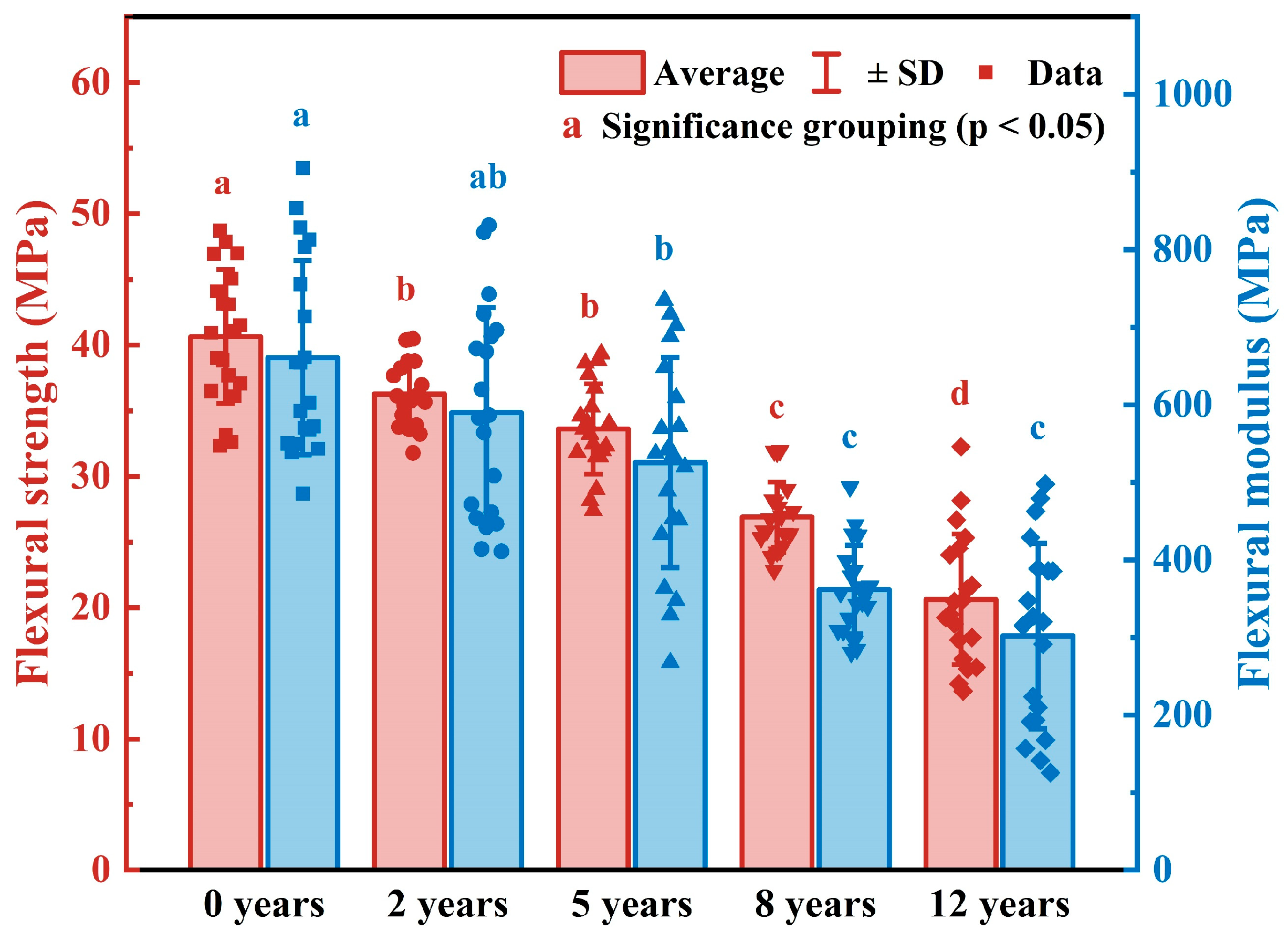

3.1.2. Mechanical Properties

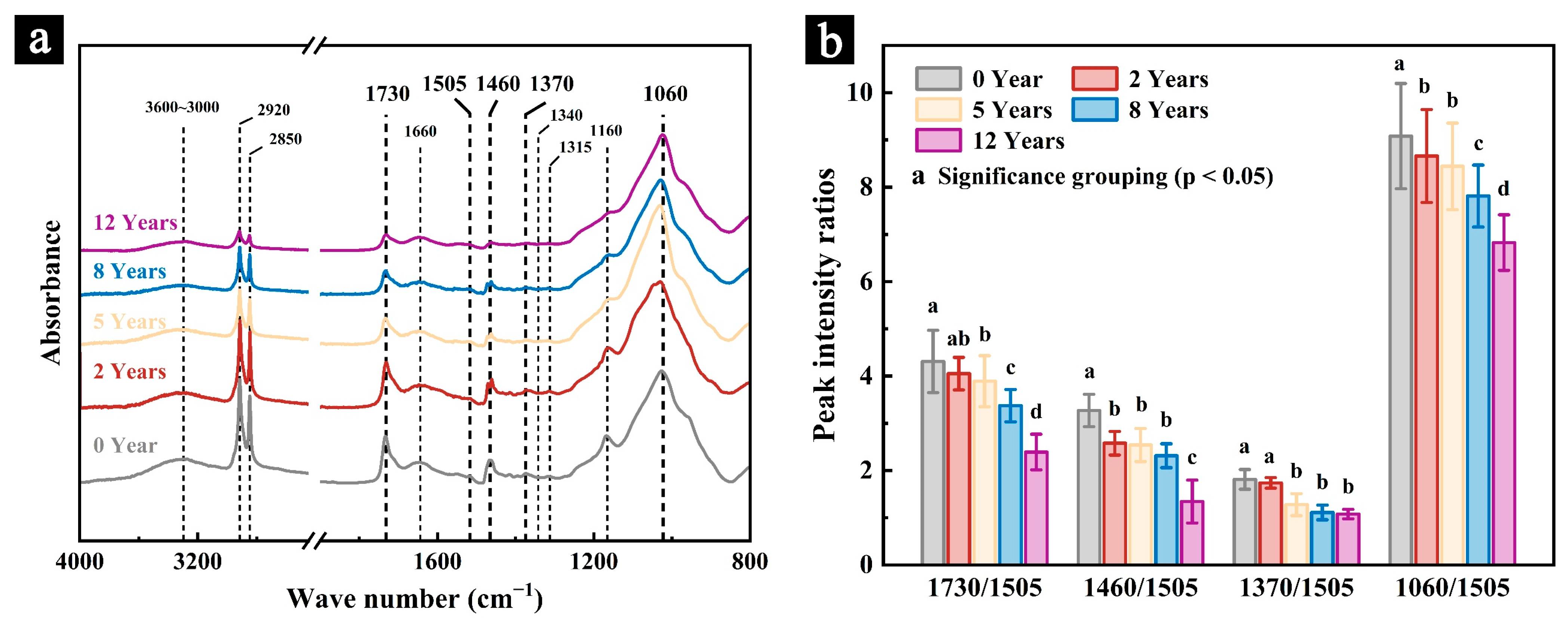

3.1.3. FT-IR

| Wave Number (cm−1) | Functional Groups Ascriptions |

|---|---|

| 3600~3000 | Stretching vibration by the hydroxyl on cellulose and the intermolecular hydrogen bonds [29] |

| 3000~2800 | Stretching vibration by the methyl and methylene groups on cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin [30,31] |

| 1730 | Stretching vibration by the carbonyl group on hemicelluloses [25,26] |

| 1660 | Stretching vibration by the carbonyl group on deconjugated carbonyl ketone in lignin [30,32] |

| 1550~1500 | Backbone vibration of butyl propane in butyl lignin [26,33] |

| 1460 | Stretching vibration by the methylene group on hemicelluloses [25,26] |

| 1450 | Bending vibration by the methylene group in lignin and the hydroxyl group in cellulose [34,35] |

| 1370 | Bending vibration by the methyl group on cellulose [26,27] |

| 1330 | Bending vibration by the methyl group on methoxy in amorphous cellulose [34,35] |

| 1315 | Bending vibration by the methylene group on crystalline cellulose [34,36] |

| 1160 | Bending vibration by the glycosidic bond on glucopyranose, carbohydrate, and crystalline cellulose [31,34] |

| 1060 | Bending vibration by the glycosidic bond on cellulose [26,27] |

3.2. Simulated Aging of Samples

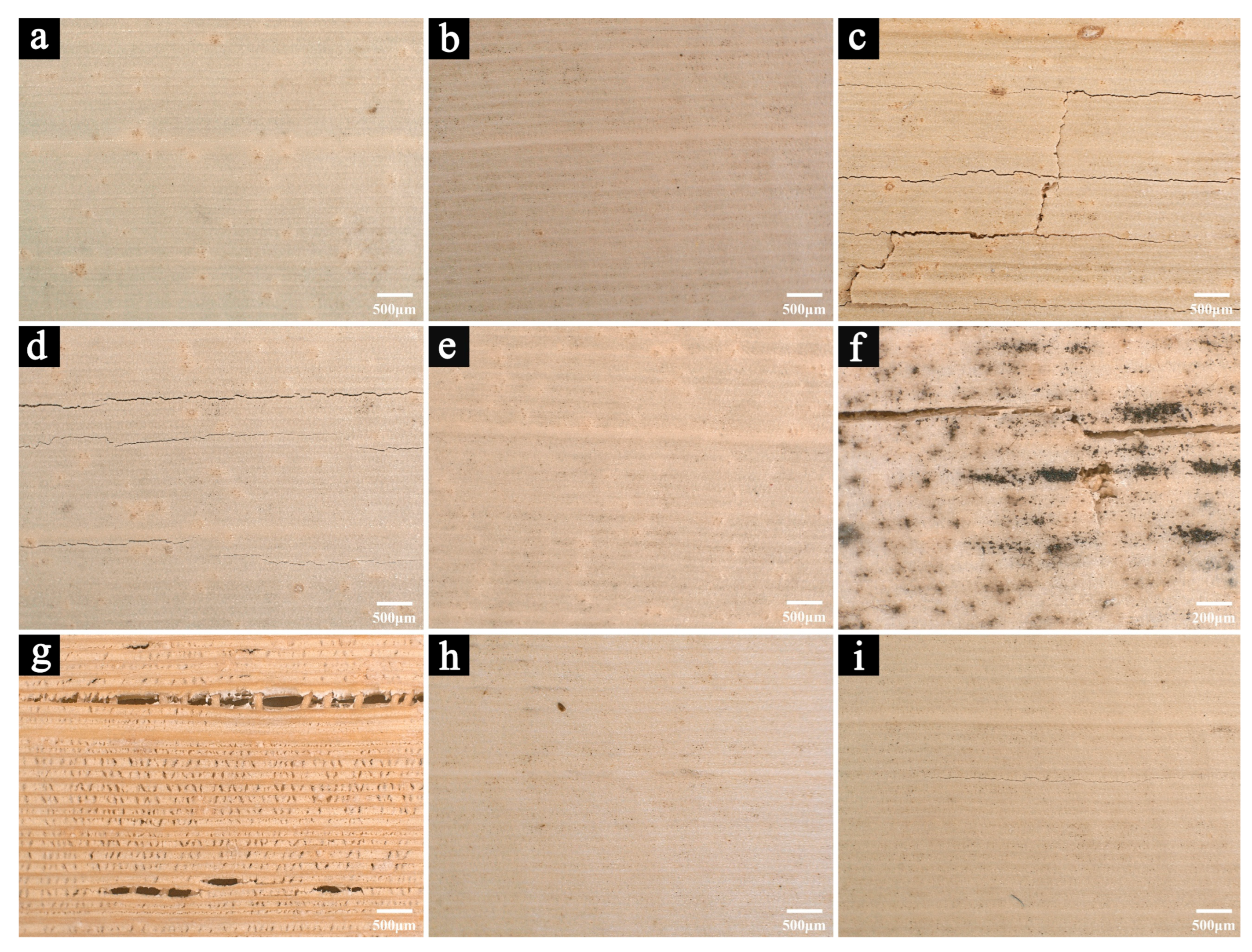

3.2.1. Microscopic Images

3.2.2. Mechanical Properties

3.2.3. FT-IR

3.3. Discussion and Prospect

4. Conclusions

- Temperature: Low-temperature environments enhance the mechanical properties of palm leaf manuscripts in the short term, but the accompanying growth and rupture of ice crystals damage the fibers and reduce the mechanical properties of palm leaf manuscripts. In contrast, the mechanical properties of palm leaf manuscripts decline rapidly in high-temperature environments, primarily due to dehydration-induced shrinkage, cracking, and thermal decomposition of hemicellulose.

- Relative Humidity: Humid environments accelerate the degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose through microbial activity and moisture-driven hydrolysis, leading to the maximum deterioration of the mechanical properties of palm leaf manuscripts. Dry environments, meanwhile, impair their mechanical properties by inducing cracking and shrinkage in palm leaf manuscripts.

- Light Radiation: Ultraviolet irradiation triggers extensive photochemical degradation of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose in palm leaf manuscripts, resulting in significant losses in mechanical properties. Infrared light produces milder effects, primarily influencing the mechanical properties of palm leaf manuscripts through its thermal impact.

- FT-IR analysis confirmed a strong link between chemical composition and mechanical properties.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, D.U.; Sreekumar, G.; Athvankar, U. Traditional writing system in southern India—Palm leaf manuscripts. Des. Thoughts 2009, 7, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, A.K.; Litt, D. Odia Script in Palm-Leaf Manuscripts. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 23, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Meher, R. Tradition of palm leaf manuscripts in Orissa. Orissa Rev. 2009, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, M.; Krist, G.; Velayudhan, N.M. Structural characterisation of 18th century Indian Palm leaf manuscripts of India. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 9, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, M.R.; Dighe, B. Chromatographic Study on Traditional Natural Preservatives Used for Palm Leaf Manuscripts in India. Restaurator 2018, 39, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.R.; Sharma, D. Investigation of Pigments on an Indian Palm Leaf Manuscript (18th–19th century) by SEM-EDX and other Techniques. Restaurator 2020, 41, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, O.P. Conservation of Manuscripts and Paintings of South-East Asia; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, A. Palm Leaf Manuscripts of the World: Material, Technology and Conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2002, 47 (Suppl. S1), 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, T.J.; Kumar, S.S. A novel binarization technique based on Whale Optimization Algorithm for better restoration of palm leaf manuscript. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, K.; Subramaniam, M. Creation of original Tamil character dataset through segregation of ancient palm leaf man-uscripts in medicine. Expert Syst. 2021, 38, e12538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeenian, R.; Paramasivam, M.; Anand, R.; Dinesh, P. (Eds.) Palm-leaf manuscript character recognition and classification using convolutional neural networks. In Computing and Network Sustainability: Proceedings of IRSCNS 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, X.; Wang, J.; Lyu, X. Preservation characteristics and restoration core technology of palm leaf manuscripts in Potala Palace. Arch. Sci. 2022, 22, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Han, L.; Guo, H. Study on the hygroscopicity and kinetic and thermodynamic properties of ancient Tibetan Palm Leaf Manuscripts. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiland, J.; Brown, R.; Fuller, L.; Havelock, L.; Johnson, J.; Kenn, D.; Kralka, P.; Muzart, M.; Pollard, J.; Snowdon, J. A literature review of palm leaf manuscript conservation—Part 1: A historic overview, leaf preparation, materials and media, palm leaf manuscripts at the British Library and the common types of damage. J. Inst. Conserv. 2022, 45, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiland, J.; Brown, R.; Fuller, L.; Havelock, L.; Johnson, J.; Kenn, D.; Kralka, P.; Muzart, M.; Pollard, J.; Snowdon, J. A literature review of palm leaf manuscript conservation—Part 2: Historic and current conservation treatments, boxing and storage, reli-gious and ethical issues, recommendations for best practice. J. Inst. Conserv. 2023, 46, 64–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, S. Study on the material properties and deterioration mechanism of palm leaves. Restaurator 2024, 45, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graminski, E.L.; Parks, E.J.; Toth, E.E. The Effects of Temperature and Moisture on the Accelerated Aging of Paper. Restaurator 1979, 3, 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Y.; Timar, M.C.; Varodi, A.M.; Sawyer, G. An Investigation of Accelerated Temperature-Induced Ageing of Four Wood Species: Colour and FTIR. Wood Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund Melin, C.; Hagentoft, C.-E.; Holl, K.; Nik, V.M.; Kilian, R. Simulations of Moisture Gradients in Wood Subjected to Changes in Relative Humidity and Temperature Due to Climate Change. Geosciences 2018, 8, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Choi, Y.-S.; Oh, J.-J.; Kim, G.-H. Experimental investigation of the humidity effect on wood discoloration by selected mold and stain fungi for a proper conservation of wooden cultural heritages. J. Wood Sci. 2020, 66, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, S.; Di Lazzaro, P.; Flora, F.; Mezi, L.; Murra, D. Raman spectral mapping reveal molecular changes in cellulose aging induced by ultraviolet and extreme ultraviolet radiation. Cellulose 2024, 31, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, K.; Takada, H.; Sugiyama, M.; Hasegawa, R. Changes in the Properties of Light-Irradiated Wood with Heat Treatment: Part 1. Effect of Treatment Conditions on the Change in Color. Holzforschung 2001, 55, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Han, L.; Guo, H. Aging effects of relative humidity on palm leaf manuscripts and optimal humidity conditions for preservation. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Guo, H. Influence of Relative Humidity on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Leaf Manuscripts: Short-Term Effects and Long-Term Aging. Molecules 2024, 29, 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanninger, M.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Pereira, H.; Hinterstoisser, B. Effects of short-time vibratory ball milling on the shape of FT-IR spectra of wood and cellulose. Vib. Spectrosc. 2004, 36, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchessault, R.H. Application of infra-red spectroscopy to cellulose and wood polysaccharides. Pure Appl. Chem. 1962, 5, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K.; Pitman, A.J. FTIR studies of the changes in wood chemistry following decay by brown-rot and white-rot fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2003, 52, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Lin, L.; Tian, X. Analysis of Aspergillus niger isolated from ancient palm leaf manuscripts and its deterioration mechanisms. npj Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Athanassiou, A. Alkaline hydrolysis of biomass as an alternative green method for bioplastics preparation: In situ cellulose nanofibrillation. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 454, 140171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukir, A.; Guiliano, M.; Asia, L.; El Hallaoui, A.; Mille, G. A fraction to fraction study of photo-oxidation of BAL 150 crude oil asphaltenes. Analusis 1998, 26, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Rahaman, T.; Gupta, P.; Mitra, R.; Dutta, S.; Kharlyngdoh, E.; Guha, S.; Ganguly, J.; Pal, A.; Das, M. Cellulose and lignin profiling in seven, economically important bamboo species of India by anatomical, biochemical, FTIR spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 158, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, N.; Larsson, P.A.; Jain, K.; Abitbol, T.; Cernescu, A.; Wågberg, L.; Johnson, C.M. Elucidating the fine-scale structural morphology of nanocellulose by nano infrared spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 302, 120320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Miller, K.; Kermanshahi-Pour, A.; Brar, S.K.; Beims, R.F.; Xu, C.C. Nanocrystalline cellulose derived from spruce wood: Influence of process parameters. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouramdane, Y.; Haddad, M.; Mazar, A.; Aît Lyazidi, S.; Oudghiri Hassani, H.; Boukir, A. Aged Lignocellulose Fibers of Cedar Wood (9th and 12th Century): Structural Investigation Using FTIR-Deconvolution Spectroscopy, X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), Crystallinity Indices, and Morphological SEM Analyses. Polymers 2024, 16, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broda, M.; Popescu, C.-M. Natural decay of archaeological oak wood versus artificial degradation processes—An FT-IR spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 209, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukir, A.; Fellak, S.; Doumenq, P. Structural characterization of Argania spinosa Moroccan wooden artifacts during natural degradation progress using infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) and X-Ray diffraction (XRD). Heliyon 2019, 5, e02477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Lin, L.; Tian, X. Evaluation of the Deterioration State of Historical Palm Leaf Manuscripts from Burma. Forests 2023, 14, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Yao, J.; Jin, S.; Tang, Y. Chemistry directs the conservation of paper cultural relics. Polymer Degrad. Stab. 2023, 207, 110228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonsky, M.; Šima, J. Oxidative degradation of paper—A minireview. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 48, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Fei, B.; Chen, H. The mechanical properties and thermal conductivity of bamboo with freeze–thaw treatment. J. Wood Sci. 2021, 67, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, O.E. Effect of freezing temperature on impact bending strength and shore-D hardness of some wood species. BioResources 2022, 17, 6123–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Liu, J. Alkaline Degradation of Plant Fiber Reinforcements in Geopolymer: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Guo, H. Effects of Environmental Factors on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Leaf Manuscripts: Natural Aging, Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Light Radiation. Polymers 2025, 17, 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233229

Zhang W, Wang S, Guo H. Effects of Environmental Factors on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Leaf Manuscripts: Natural Aging, Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Light Radiation. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233229

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenjie, Shan Wang, and Hong Guo. 2025. "Effects of Environmental Factors on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Leaf Manuscripts: Natural Aging, Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Light Radiation" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233229

APA StyleZhang, W., Wang, S., & Guo, H. (2025). Effects of Environmental Factors on the Mechanical Properties of Palm Leaf Manuscripts: Natural Aging, Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Light Radiation. Polymers, 17(23), 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233229