Ionic Conductive Hydrogels with Choline Salt for Potential Use in Electrochemical Capacitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Choline Methacrylate (ChMAA) Synthesis

2.2.2. Preparation of Photocurable Compositions

2.2.3. Hydrogel Polymer Electrolyte Synthesis

2.2.4. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy

2.2.5. NMR

2.2.6. Electrolyte Sorption

2.2.7. Thermal Characteristics

2.2.8. Puncture Resistance

2.2.9. Ionic Conductivity

2.2.10. Preparation of Electrodes and Electrochemical Capacitor

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Monomer Synthesis

3.2. Hydrogel Polymer Electrolytes Synthesis

3.3. Sorption of Electrolyte

3.4. Puncture Resistance

3.5. Thermal Characteristics

3.6. Ionic Conductivity

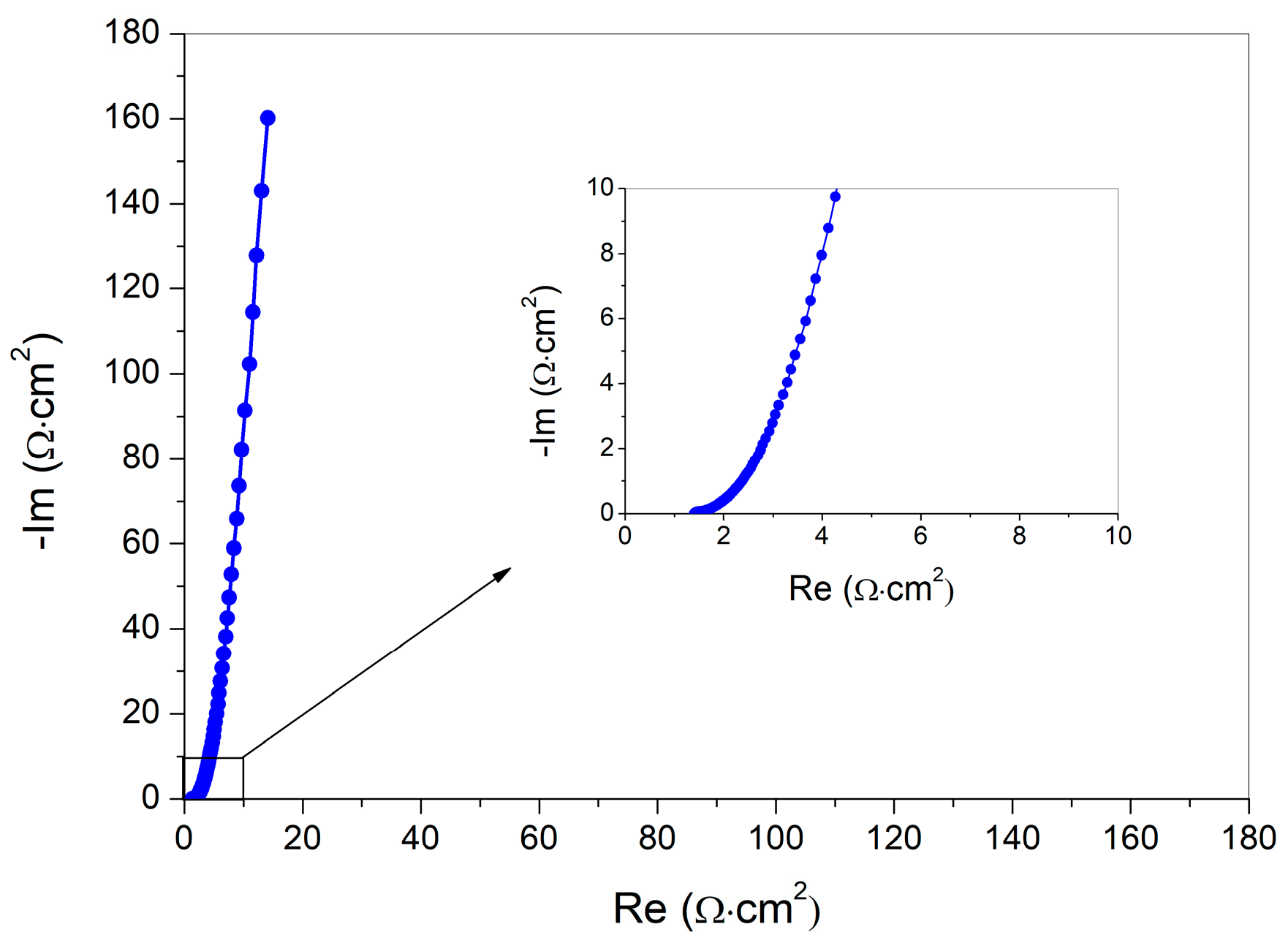

3.7. Electrochemical Investigation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enasel, E.; Dumitrascu, G. Storage solutions for renewable energy: A review. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, S.; Koudahi, M.F.; Frackowiak, E. Reline deep eutectic solvent as a green electrolyte for electrochemical energy storage applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 1156–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, K.; Kularatna-Abeywardana, D. A review of supercapacitors: Materials, technology, challenges, and renewable energy applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amisha; Acharya, A.D.; Thakur, Y.S. Tuning electrochemical performance of polyaniline-based supercapacitors by inclusion of protonic acid and electrolyte concentration. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2025, 102, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frackowiak, E.; Béguin, F. Carbon materials for the electrochemical storage of energy in capacitors. Carbon 2001, 39, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil Joshi, P. Supercapacitor: Basics and Overview. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2019, 9, 609–625. [Google Scholar]

- Alipoori, S.; Mazinani, S.; Aboutalebi, S.H.; Sharif, F. Review of PVA-based gel polymer electrolytes in flexible solid-state supercapacitors: Opportunities and challenges. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, V.S. Corrosion and Materials Degradation in Electrochemical Energy Storage and Conversion Devices. ChemElectroChem 2023, 10, e202300136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, P.; Żyła, W.; Kazimierczak, K.; Marcinkowska, A. Hydrogel Polymer Electrolytes: Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization and Application in Electrochemical Capacitors. Gels 2023, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.K.L.; Pham-Truong, T.N. Recent Advancements in Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Flexible Energy Storage Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelu, M.; Musuc, A.M. Polymer Gels: Classification and Recent Developments in Biomedical Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Meena, A.; Nam, K.W. Gels in Motion: Recent Advancements in Energy Applications. Gels 2024, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Islam, M.; Raut, B.; Yun, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Nam, K.W. A Comprehensive Review of Functional Gel Polymer Electrolytes and Applications in Lithium-Ion Battery. Gels 2024, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, A.D.; Shah, S.S.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Aziz, M.A. Advancing gel polymer electrolytes for next-generation high-performance solid-state supercapacitors: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 114851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadilohar, B.L.; Shankarling, G.S. Choline based ionic liquids and their applications in organic transformation. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 227, 234–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M.R.; Lima, A.S.; Oliveira, G.B.R.; Liao, L.M.; Franceschi, E.; Silva, R.; Cardozo-Filho, L. Choline Chloride- and Organic Acids-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Exploring Chemical and Thermophysical Properties. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 3403–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supiyeva, Z.; Mansurov, Z.; Azat, S.; Abbas, Q. A unique choline nitrate-based organo-aqueous electrolyte enables carbon/carbon supercapacitor operation in a wide temperature window (−40 °C to 60 °C). Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1377144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrade, S.; Zhao, Z.; Supiyeva, Z.; Chen, X.; Dsoke, S.; Abbas, Q. An asymmetric MnO2|activated carbon supercapacitor with highly soluble choline nitrate-based aqueous electrolyte for sub-zero temperatures. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 425, 140708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, N.; Luo, J.; Park, K.; Oakes, M.; Martin, B.; Balakrishnan, A.; Connell, J.; Kang, D.; Akolka, R. Choline Chloride-Based Water-in-Salt Electrolyte for Efficient Iron Electrodeposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 062503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdolšek, N.; Mihalinec, G.; Radovanović-Perić, F.; Mikić, D.; Dimitrijević, A.; Roković, M.K. Choline-based ionic liquid electrolyte additives for suppression of dendrite growth in Zn-ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2025, 997, 119474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygocki, P.; Abbas, Q.; Gorska, B.; Béguin, F. High-energy hybrid electrochemical capacitor operating down to −40 °C with aqueous redox electrolyte based on choline salts. J. Power Sources 2019, 427, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.H.; Ramachandran, R.M.; Mansur, S.A.; Saleh, N.M.; Asman, S. Selective recognition of bisphenol a using molecularly imprinted polymer based on choline chloride-methacrylic acid deep eutectic solvent monomer: Synthesis characterization and adsorption study. Polymer 2023, 283, 126279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, A.; Niesyto, K.; Neugebauer, D. Pharmaceutical Functionalization of Monomeric Ionic Liquid for the Preparation of Ionic Graft Polymer Conjugates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Panzer, M.J. Chemically Cross-Linked Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)-Supported Deep Eutectic Solvent Gel Electrolytes for Eco-Friendly Supercapacitors. ChemElectroChem 2017, 10, 2556–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Z.; Yan, L. Deep eutectic solvents eutectogels: Progress and challenges. Green Chem. Eng. 2021, 2, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Sang, M.; Li, G.; Zuo, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. Stretchable, self-healable, conductive and adhesive gel polymer electrolytes based on a deep eutectic solvent for all-climate flexible electrical double-layer capacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Qin, S.; Li, S.; Wan, C.; Xie, H. Fabrication of Gelatin-Derived Gel Electrolyte Using Deep Eutectic Solvents through In Situ Derivatization and Crosslinking Strategy for Supercapacitors and Flexible Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 41483–41493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Lian, H.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, C.; Liimatainen, H. A stretchable and compressible ion gel based on a deep eutectic solvent applied as a strain sensor and electrolyte for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Sakurai, A.; Sakakibara, M.; Saga, H. Preparation and Properties of Transparent Cellulose Hydrogels. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 3020–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, M.; Sato, H.; Kaneko, Y.; Okumura, D.; Hossain, M. Evaluation of intermolecular interactions of hydrogels: Experimental study and constitutive modeling. Int. J. Solid Struct. 2025, 317, 113428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaganov, Z.; Malchik, F.; Bakenov, Z.; Mansurov, Z.; Maldybayev, K.; Kurbatov, A.; Ng, A.; Pavlenko, V. Electrochemical Evaluation of Choline Bromide-Based Electrolyte for Hybrid Supercapacitors. Energies 2024, 17, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Banerjee, K.; Gupta, M.; Bainsla, Y.K.; Pandit, V.U.; Singh, P.; Uke, S.J.; Kumar, A.; Mardikar, S.P.; Kumar, Y. Concentration dependent electrochemical performance of aqueous choline chloride electrolyte. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 53, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, P.; Lewandowska, A.; Szcześniak, K.; Przesławski, G.; Marcinkowska, A. Optimization of the Properties of Photocured Hydrogels for Use in Electrochemical Capacitors. Polymers 2021, 13, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Long, H.; Zhang, D.; Fu, Z.; Wu, N.; Zhai, Z.; Wang, B. 3D hierarchical porous hydrogel polymer electrolytes for flexible quasi-solid-state supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 510, 161766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, J.H.; Choi, U.H. Triple-network hydrogel polymer electrolytes: Enabling flexible and robust supercapacitors for extreme conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | ChMAA, wt.% | PEGDA, wt.% | HEMA, wt.% | 1M ChNO3, wt.% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPE_1 | 10 | 5 | 15 | 70 |

| HPE_2 | 10 | 3 | 17 | 70 |

| HPE_3 | 10 | 1.5 | 18.5 | 70 |

| HPE_4 | 10 | 1.2 | 18.8 | 70 |

| HPE_5 | 10 | 1.1 | 18.9 | 70 |

| HPE_6 | 10 | 1 | 19 | 70 |

| HPE_4(70) | HPE_4(87) | |

|---|---|---|

| Force [N] | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| Elongation [mm] | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 1.1 |

| Ionic conductivity [mS·cm−1] | 18.1 ± 4.0 | 34.2 ± 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malczak, J.; Żyła, W.; Gajewski, P.; Szcześniak, K.; Popenda, Ł.; Marcinkowska, A. Ionic Conductive Hydrogels with Choline Salt for Potential Use in Electrochemical Capacitors. Polymers 2025, 17, 3030. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223030

Malczak J, Żyła W, Gajewski P, Szcześniak K, Popenda Ł, Marcinkowska A. Ionic Conductive Hydrogels with Choline Salt for Potential Use in Electrochemical Capacitors. Polymers. 2025; 17(22):3030. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223030

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalczak, Jan, Wiktoria Żyła, Piotr Gajewski, Katarzyna Szcześniak, Łukasz Popenda, and Agnieszka Marcinkowska. 2025. "Ionic Conductive Hydrogels with Choline Salt for Potential Use in Electrochemical Capacitors" Polymers 17, no. 22: 3030. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223030

APA StyleMalczak, J., Żyła, W., Gajewski, P., Szcześniak, K., Popenda, Ł., & Marcinkowska, A. (2025). Ionic Conductive Hydrogels with Choline Salt for Potential Use in Electrochemical Capacitors. Polymers, 17(22), 3030. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223030