5.1. Elasticity and Strength Parameters

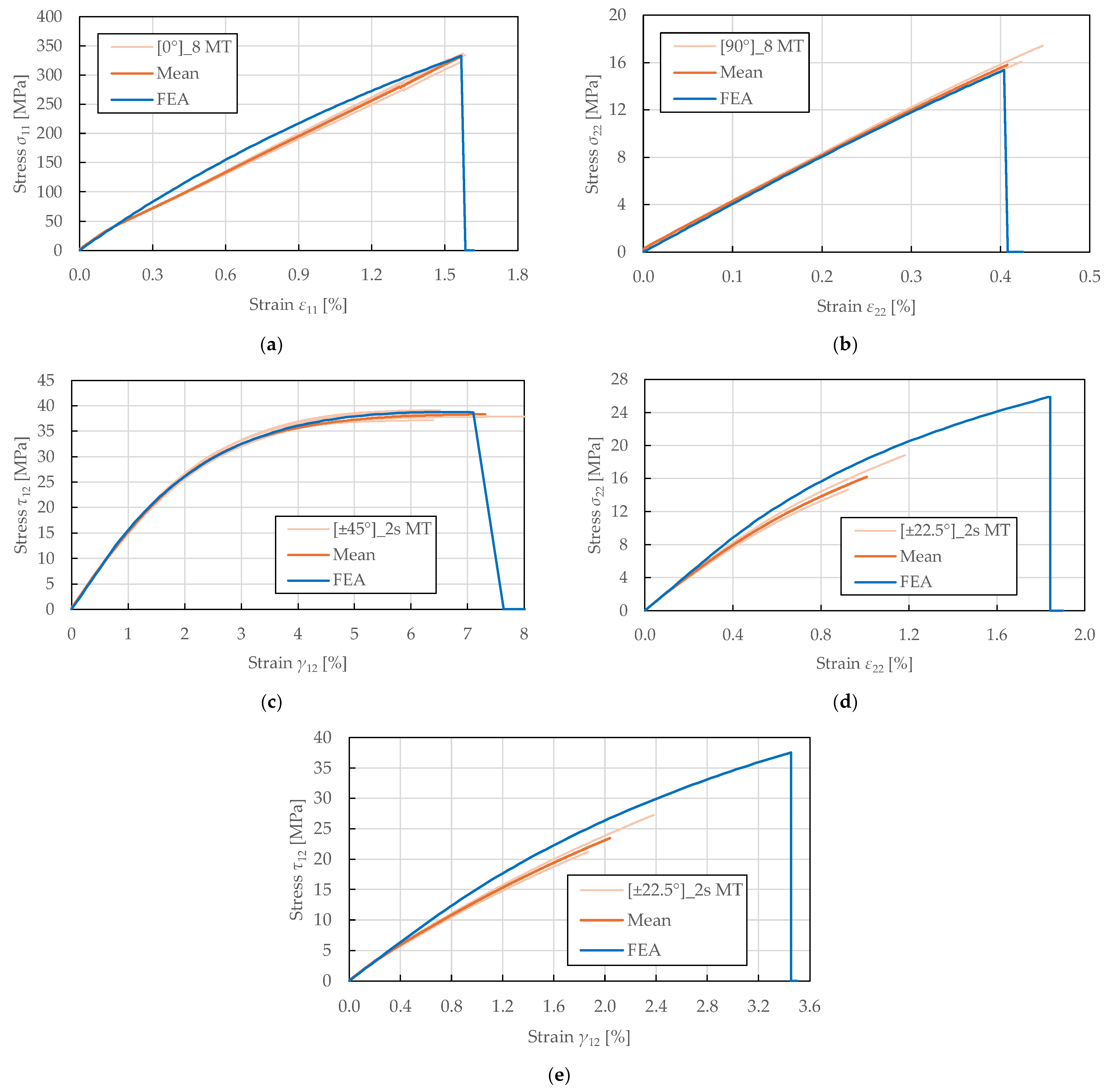

The elasticity and strength parameters of FFRPs were identified from experimental stress–strain curves following the recommendations in ASTM standards [

53,

55,

71].

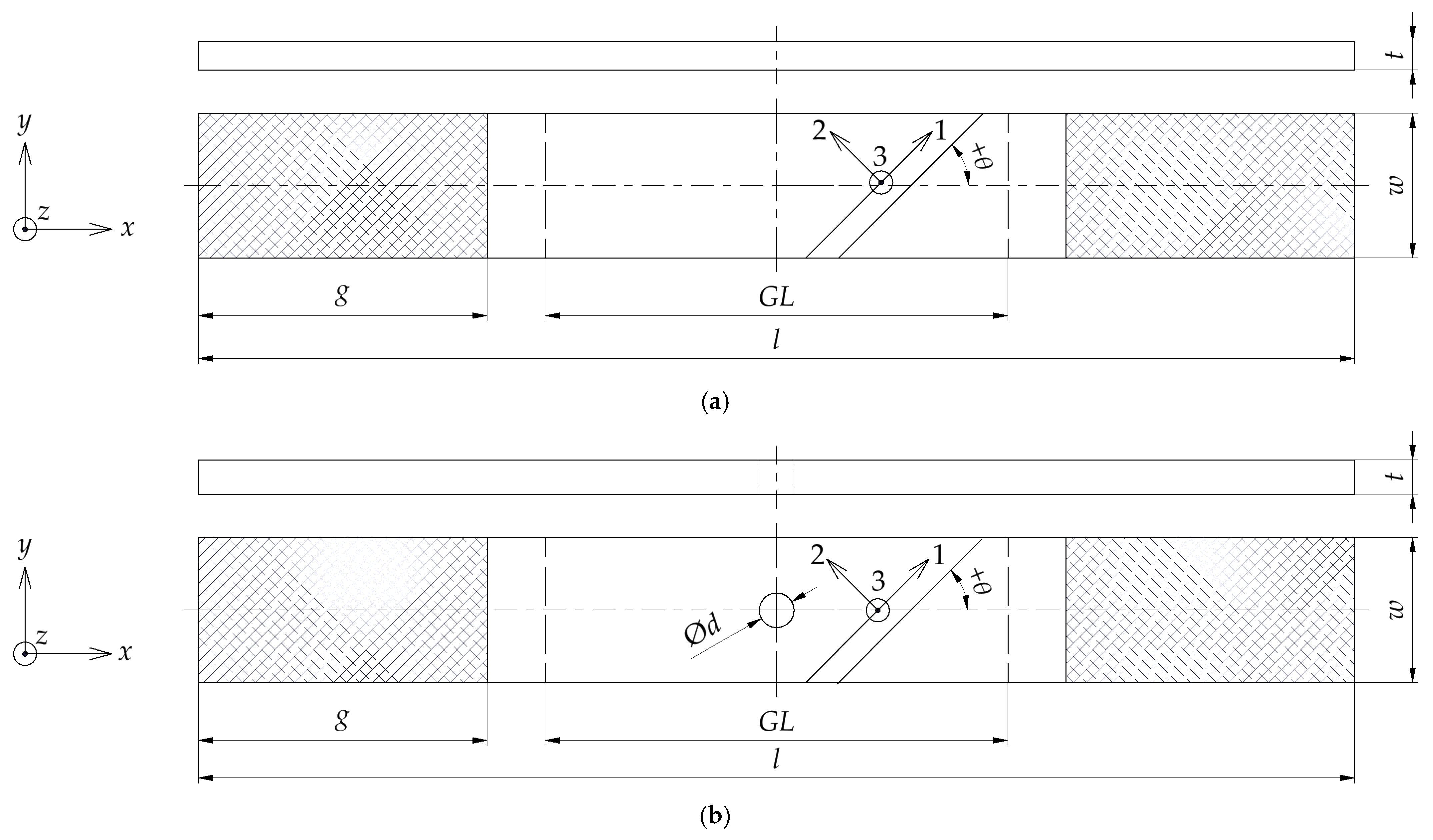

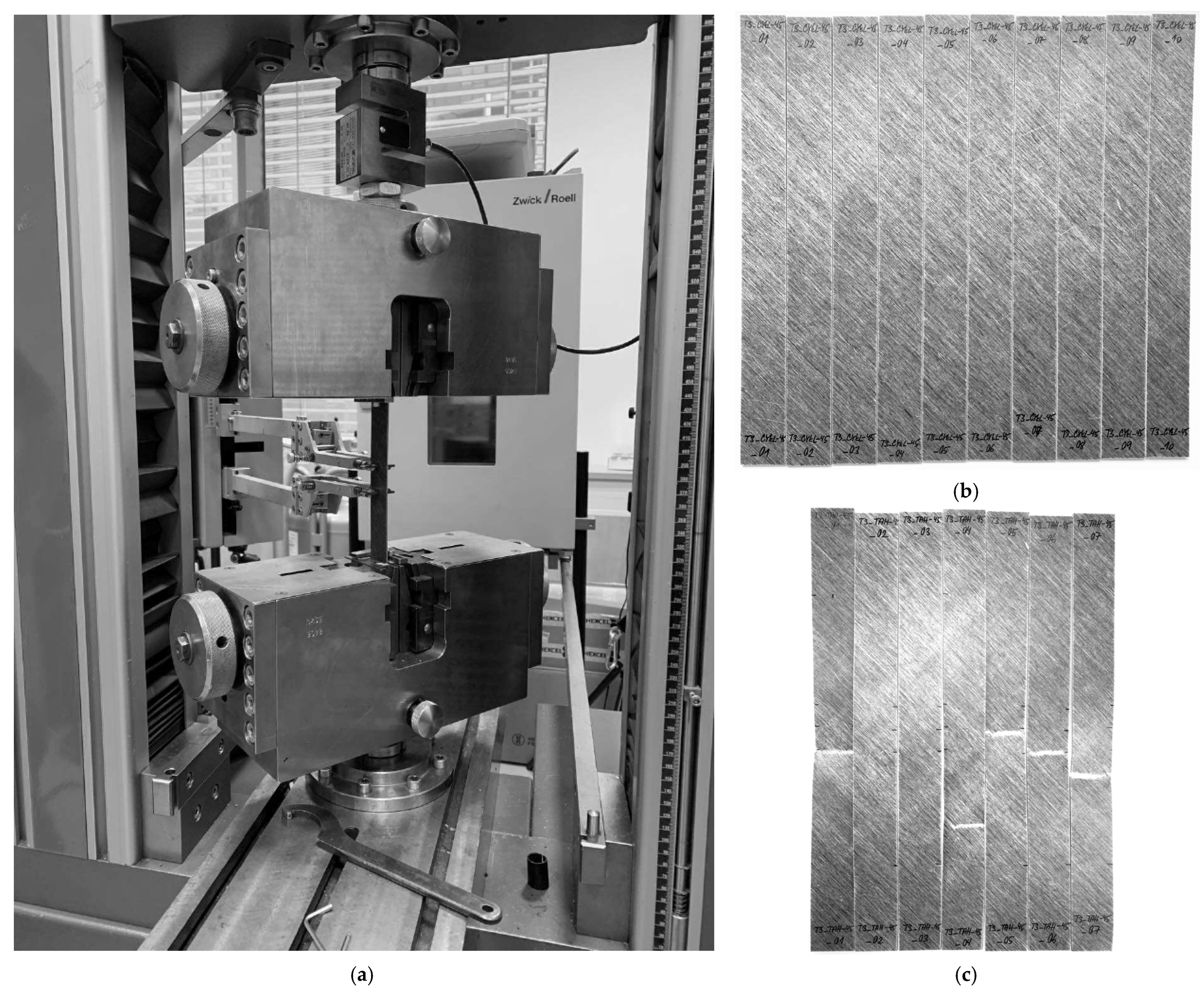

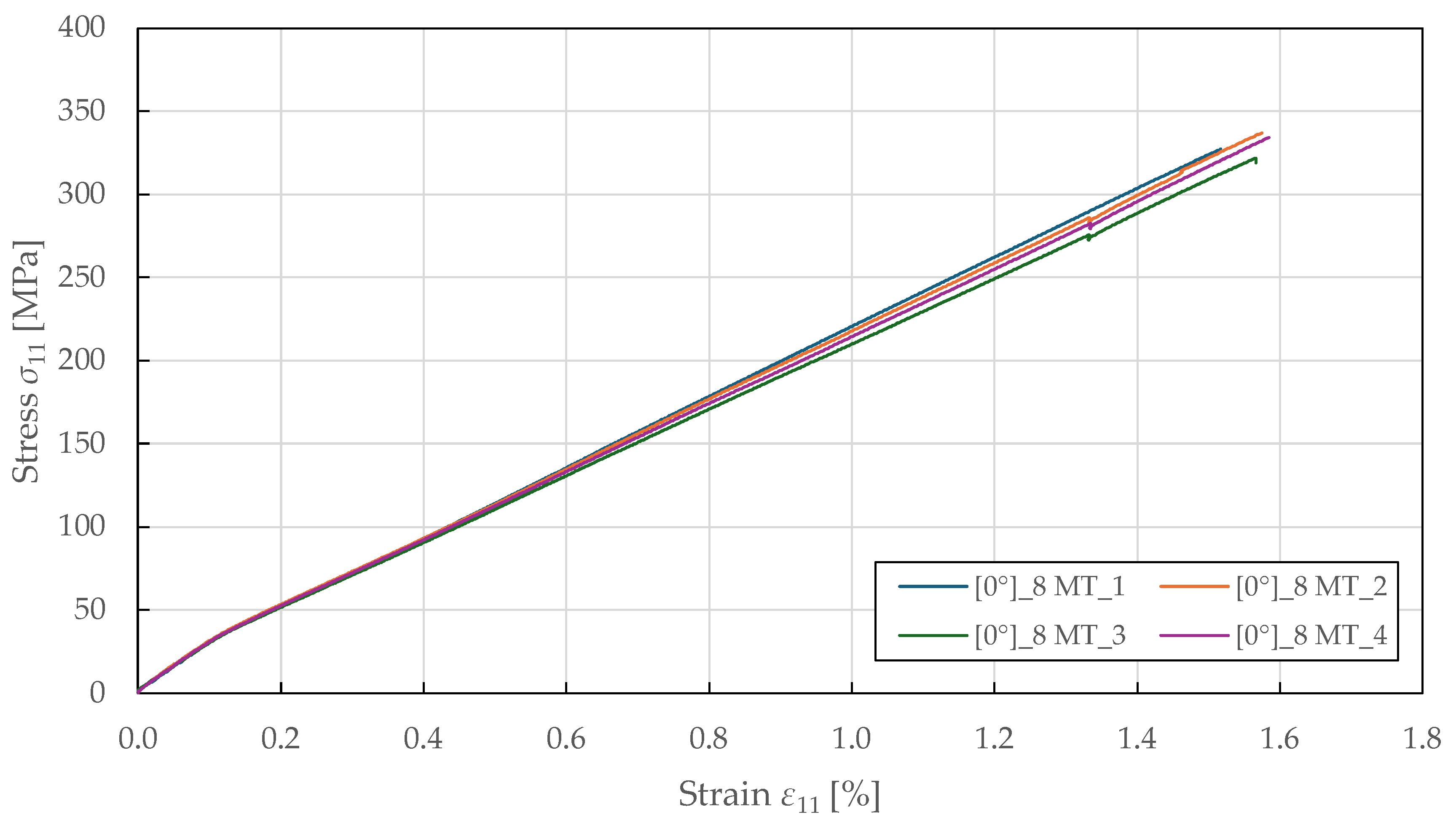

The tensile fibre-direction properties were determined using

specimens tested in accordance with ASTM D3039 [

53]. The resulting stress–strain curves in

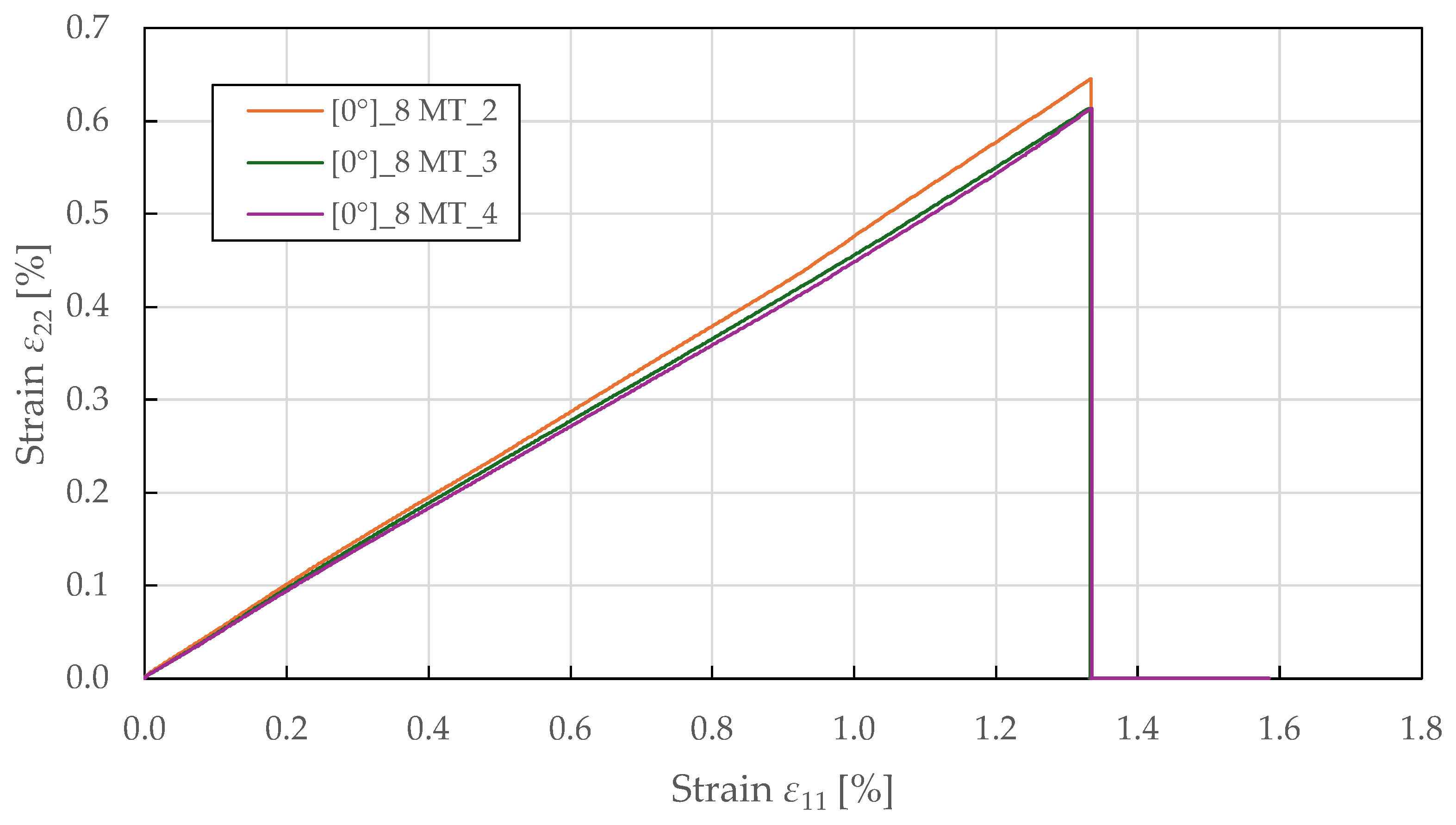

Figure 3 demonstrate a bi-linear response up to failure, yielding around a stress of 35 ± 2 MPa and a strain of 0.12 ± 0.01%, beyond which the response becomes nonlinear with a reduced tangent modulus. This bi-linear behaviour differs from that of carbon fibre composites, which typically exhibit a linear response to failure, and reflects the progressive accumulation of damage in the form of microcracking at the fibre–matrix interface and internal fibre damage. The yield point represents the onset of plastic deformation, beyond which permanent damage accumulates. The specimen-to-specimen variability in the post-yield behaviour is characteristic of natural fibre composites and reflects heterogeneity in fibre properties, waviness, and manufacturing quality. The relationship between transverse and longitudinal strain is predominantly linear, as shown in

Figure 4. The identified Poisson’s ratio (

) indicates strong coupling between longitudinal extension and transverse contraction. This high value of Poisson’s ratio (compared to typical values of 0.25–0.35 for synthetic fibre composites) may reflect the complex deformation mechanisms of flax fibres, including microstructural rearrangement and matrix plastic flow. The biaxial extensometer was unclipped at a longitudinal and transverse strain of 1.32 ± 0.05% and 0.57 ± 0.03%, respectively, to avoid damaging it, well before ultimate failure at 1.56 ± 0.06%. This confirms that the linear strain relationship is maintained throughout the majority of the loading history. The identified tensile fibre-direction material properties for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 2.

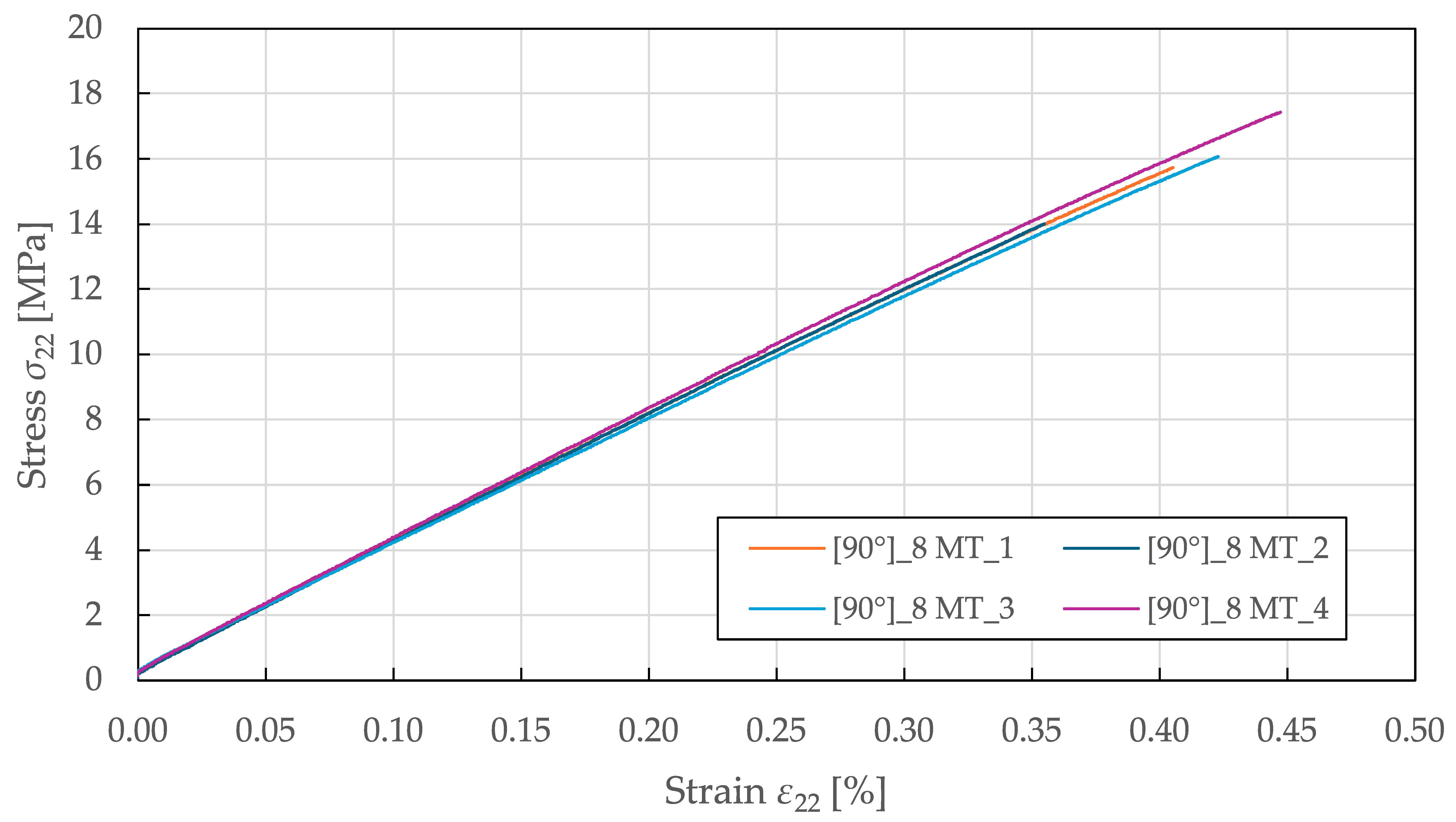

The tensile transverse direction properties were characterised using

specimens tested per ASTM D3039 [

53]. As shown in

Figure 5, the obtained stress–strain curves exhibit a predominantly linear response up to failure. Starting at a stress and strain of 5 ± 1 MPa and 0.13 ± 0.02%, the responses deviate from the initial linearity, resulting in a slight loss of stiffness. The identified tensile transverse direction material properties for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 3.

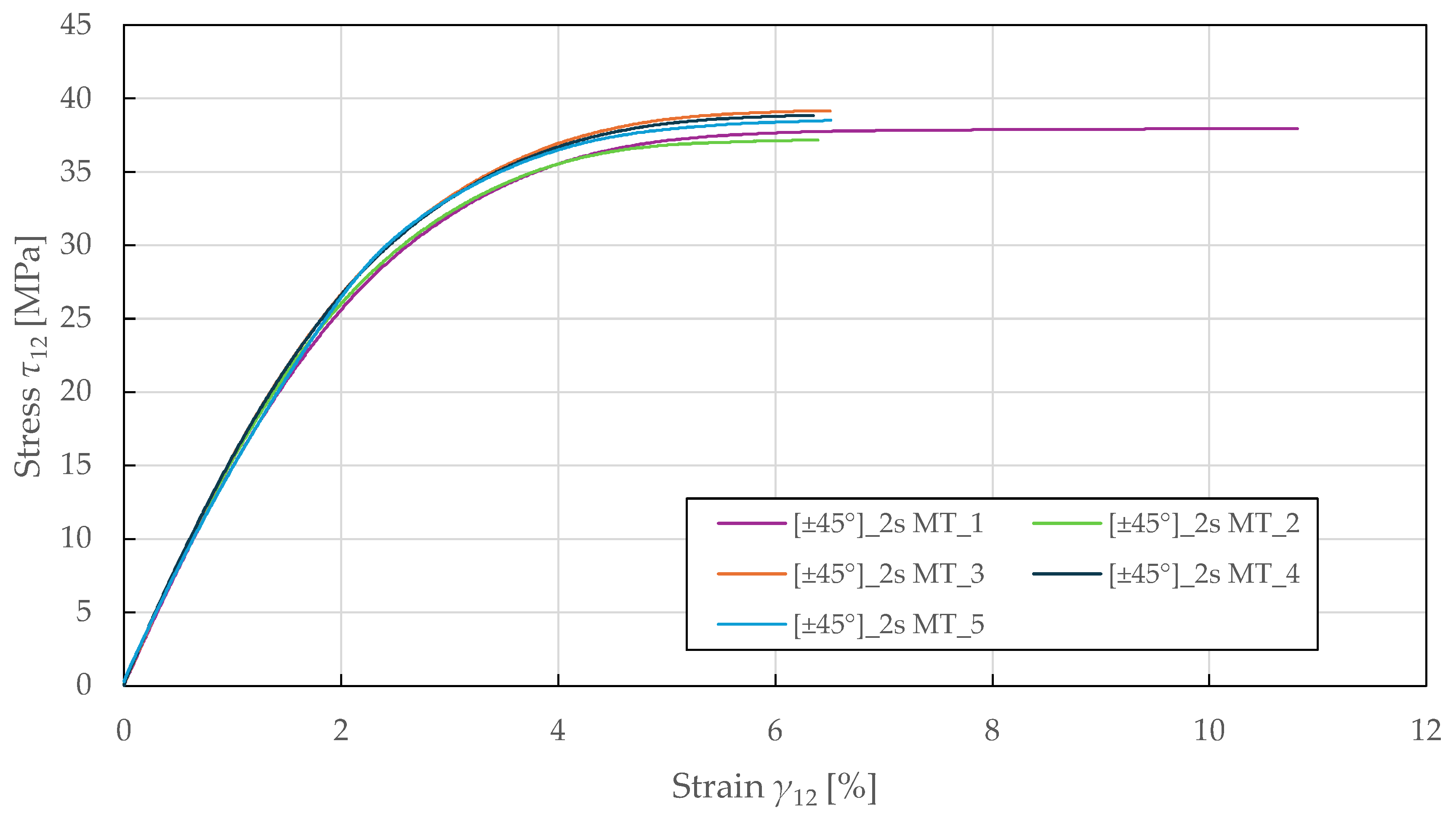

The in-plane shear properties were determined from tensile testing of

specimens according to ASTM D3518 [

71]. The resulting response in

Figure 6 demonstrates a nonlinear behaviour up to failure, with a yield point at a stress and strain of 24.5 ± 0.5 MPa and 1.80 ± 0.05%. The identified in-plane shear material properties for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 4.

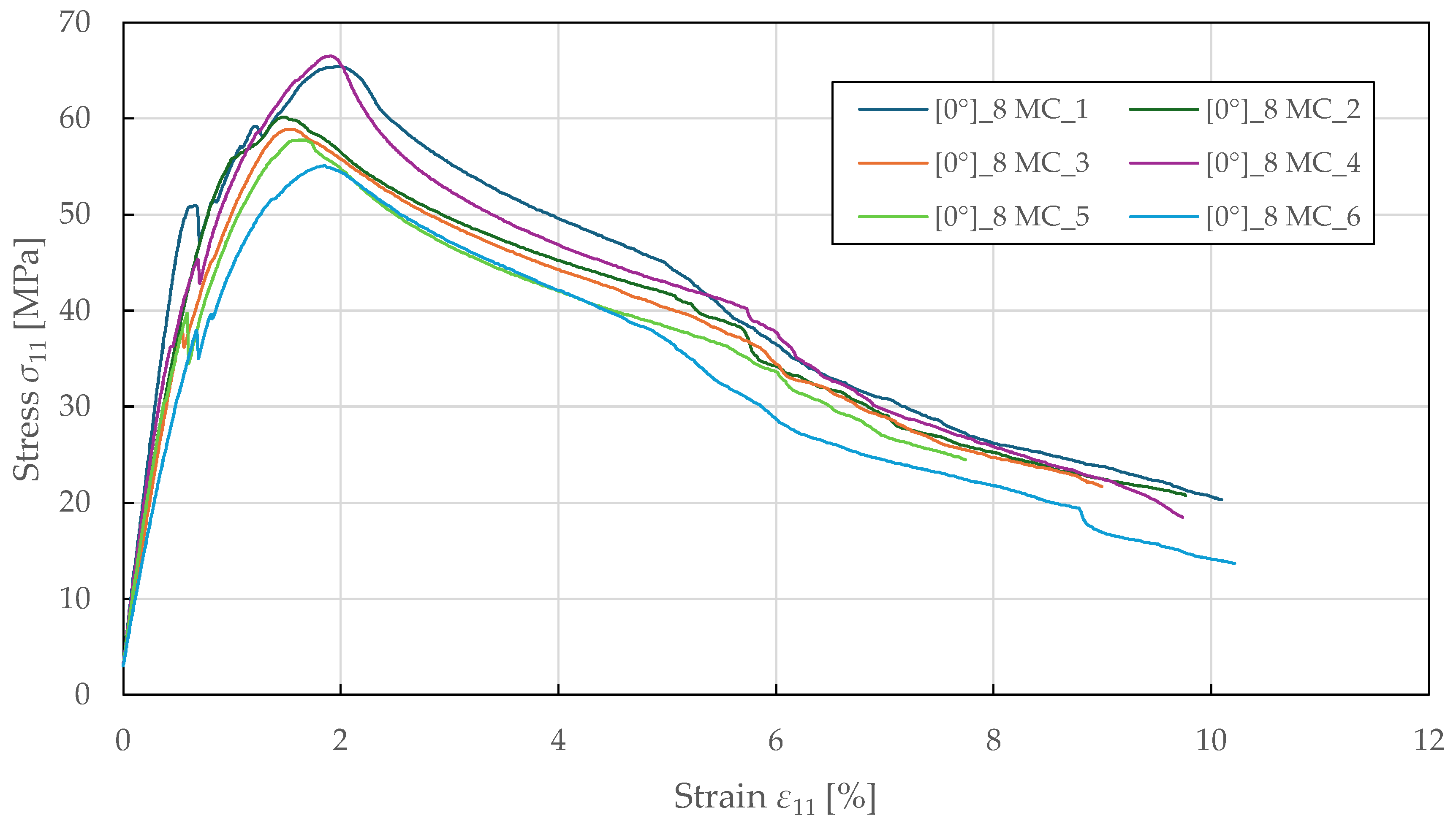

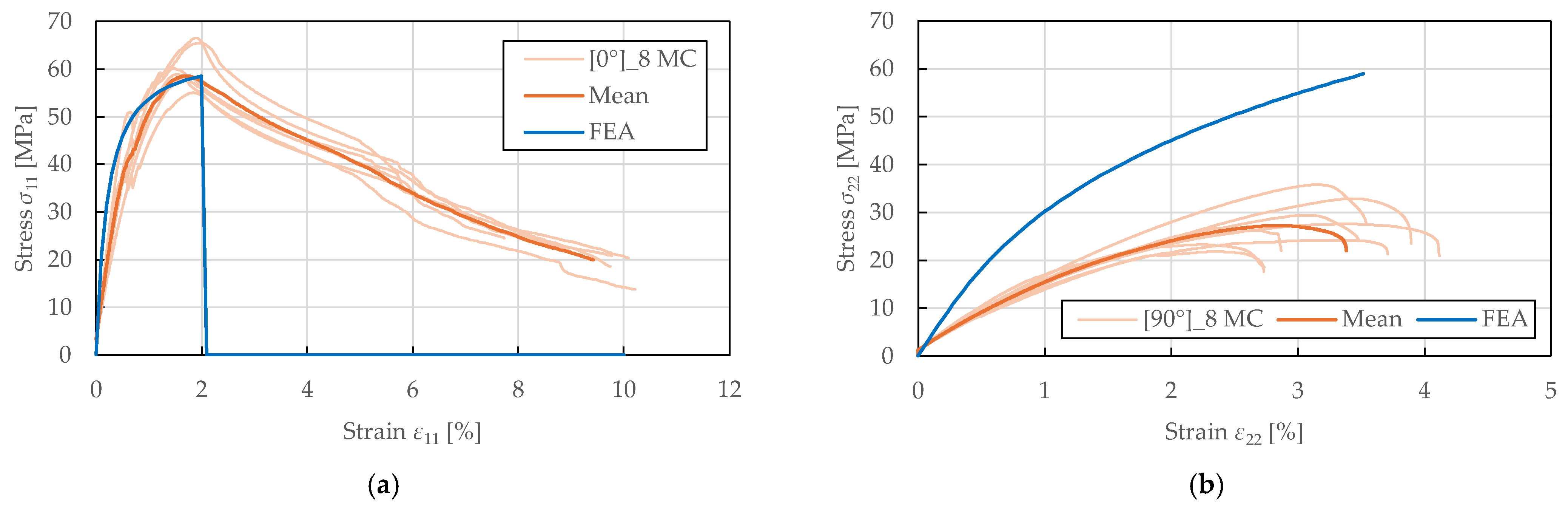

The compressive fibre-direction properties were determined from

specimens tested in accordance with ASTM D3410 [

55]. The experimental stress–strain curves shown in

Figure 7 exhibit a nonlinear response up to failure. Initially, the curves show a linear behaviour, followed by a sudden yield point at a stress and strain of 42.5 ± 8.0 MPa and 0.64 ± 0.05%. This likely indicates the onset of matrix microcracking or early fibre/matrix debonding. Beyond the peak stress region, the curves exhibit a softening behaviour characterised by a gradual decline in load-bearing capacity, reflecting loss of stability and bending of the specimens, which occurred consistently across all samples. The failure was observed at an ultimate strain of 9.5 ± 0.6%, far exceeding the strain at maximum stress. The identified compressive fibre-direction material properties for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 5.

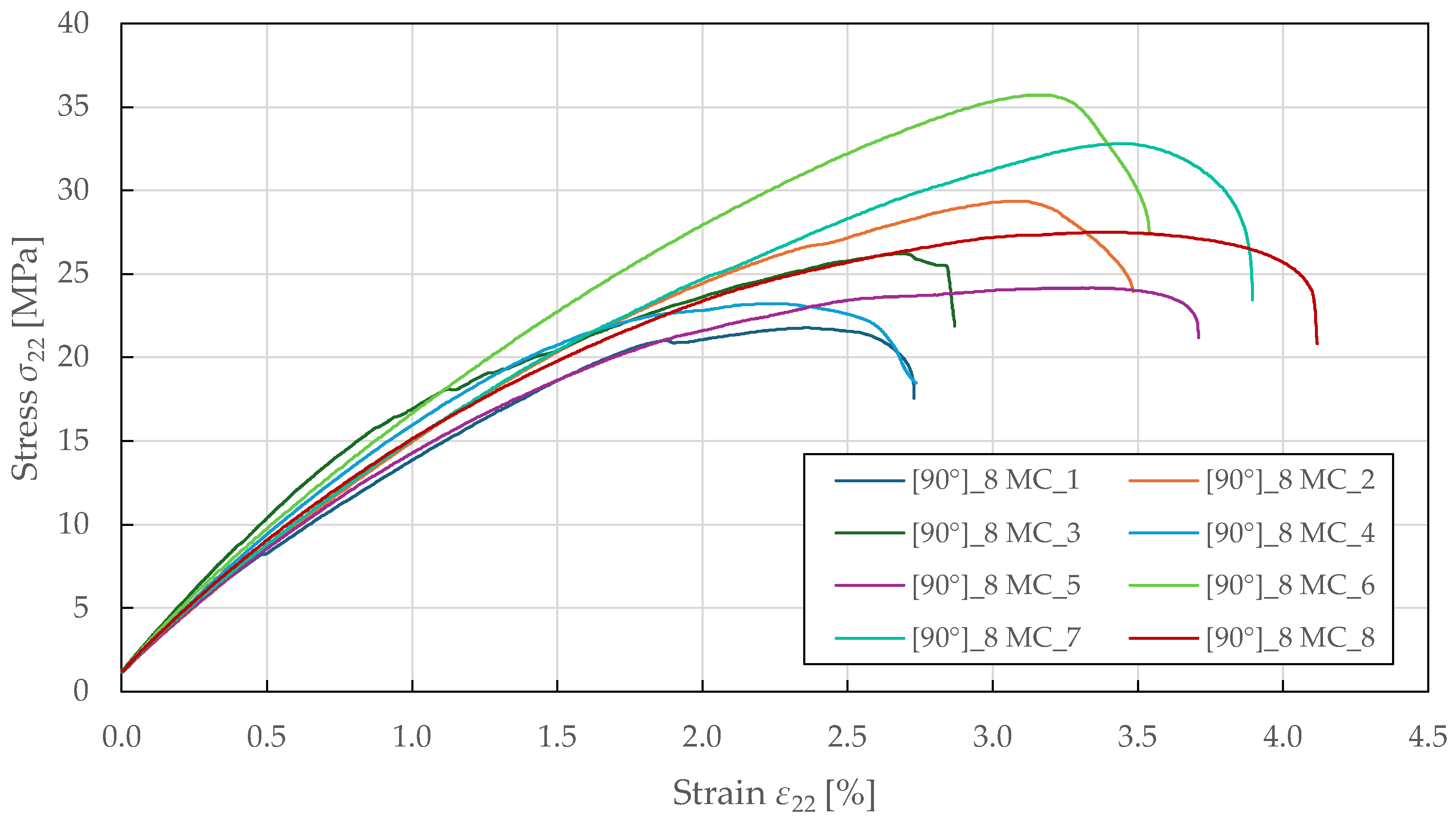

The tensile transverse direction properties were characterised using

specimens tested per ASTM D3410 [

55]. As shown in

Figure 8, the obtained response exhibits a nonlinear behaviour up to failure, with yielding occurring at a stress and strain of approximately 15.0 ± 1.5 MPa and 1.00 ± 0.08%. Post-peak, the curves show a sudden decrease in load-bearing capacity, indicating stable crushing, with a notable specimen-to-specimen variability in strength and ductility. The identified compressive transverse direction material properties for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 6.

The identified material parameters of FFRPs reveal characteristic damage anisotropy patterns that differ from those of typical synthetic fibre composites. The ratio of longitudinal to transverse tensile modulus (/ = 7.3) is lower than typical CFRPs (typically 10–15) but higher than GFRPs (typically 3–5), reflecting the moderate stiffness anisotropy of flax fibres. The ratio of tensile to compressive strength in the fibre direction (/ = 5.4) is significantly higher than that of CFRP (typically 1.5–2.0), indicating the relatively poor compressive performance of natural fibres due to kinking and microbuckling facilitated by their cellular structure. The transverse tensile-to-compressive strength ratio (/ = 0.57) also differs from synthetic composites, where transverse compression strength typically exceeds tension strength due to crack closure effects. In FFRPs, the porous structure and lower fibre–matrix interfacial strength result in progressive compressive damage under transverse compression, which the current model formulation does not adequately capture. The relatively high shear-to-transverse modulus ratio (/ = 0.4) compared to CFRP (typically 0.2–0.3) reflects the lower transverse stiffness and different deformation mechanisms of natural fibres. These anisotropy characteristics have important implications for design, as composite structures using FFRPs must be configured to minimise compressive loading perpendicular to the fibre direction.

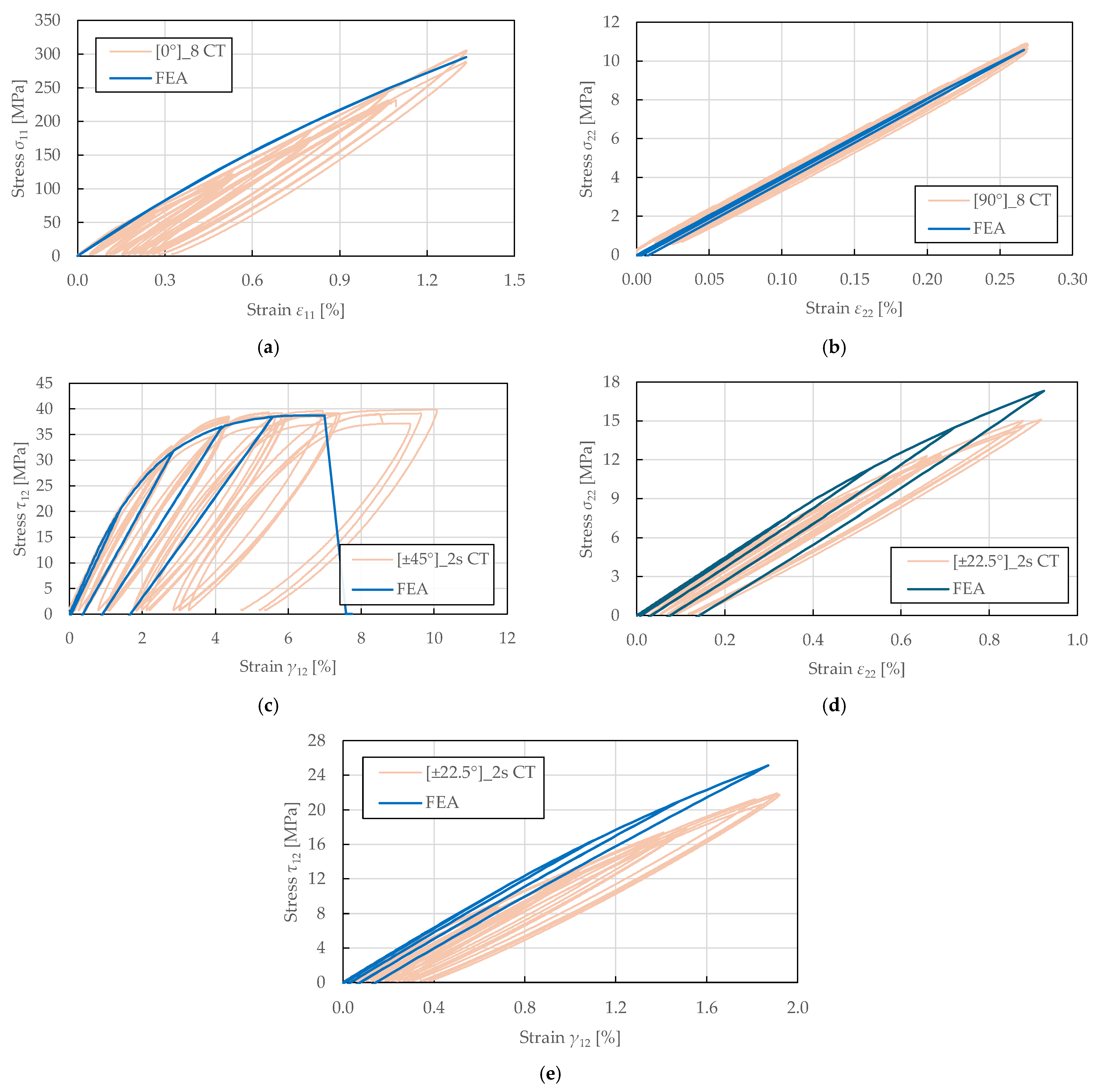

5.2. Damage and Plasticity Parameters

The damage, plasticity, and coupling parameters of FFRPs were identified following the procedure outlined in [

41] from cyclic tensile testing of specimens with

,

and

lay-ups. In the CDM model, progressive damage is characterised as a loss of moduli, which reflects material stiffness, and is revealed from hysteresis loops in stress–strain curves. The PLYUNI3 model does not account for stress and strain limits; instead, failure occurs when damage reaches its maximum [

66]. Therefore, the damage and plasticity parameters must be determined to capture the stress–strain response accurately.

The parameter identification procedure followed established protocols for CDM models and did not involve automated optimisation algorithms. Instead, parameters were determined through systematic analysis of experimental stress–strain curves from cyclic loading tests. For each loading cycle, elastic and plastic strain components were measured directly from the stress–strain data, and damage variables were calculated from the reduction in reloading modulus compared to the initial undamaged modulus using Equations (10) and (11). Thermodynamic forces were then computed from the measured stress and damage states using Equations (4) and (5). Linear regression (LR) with the least squares method (LSM) was applied to fit the damage evolution laws (Equations (8) and (9)) and the plasticity hardening law (Equation (13)) to the experimental damage-thermodynamic force and stress-plastic strain data, respectively. This direct identification approach based on physical measurements is preferred over inverse optimisation methods. It provides transparent parameter determination with clear physical interpretation and does not require iterative finite element simulations.

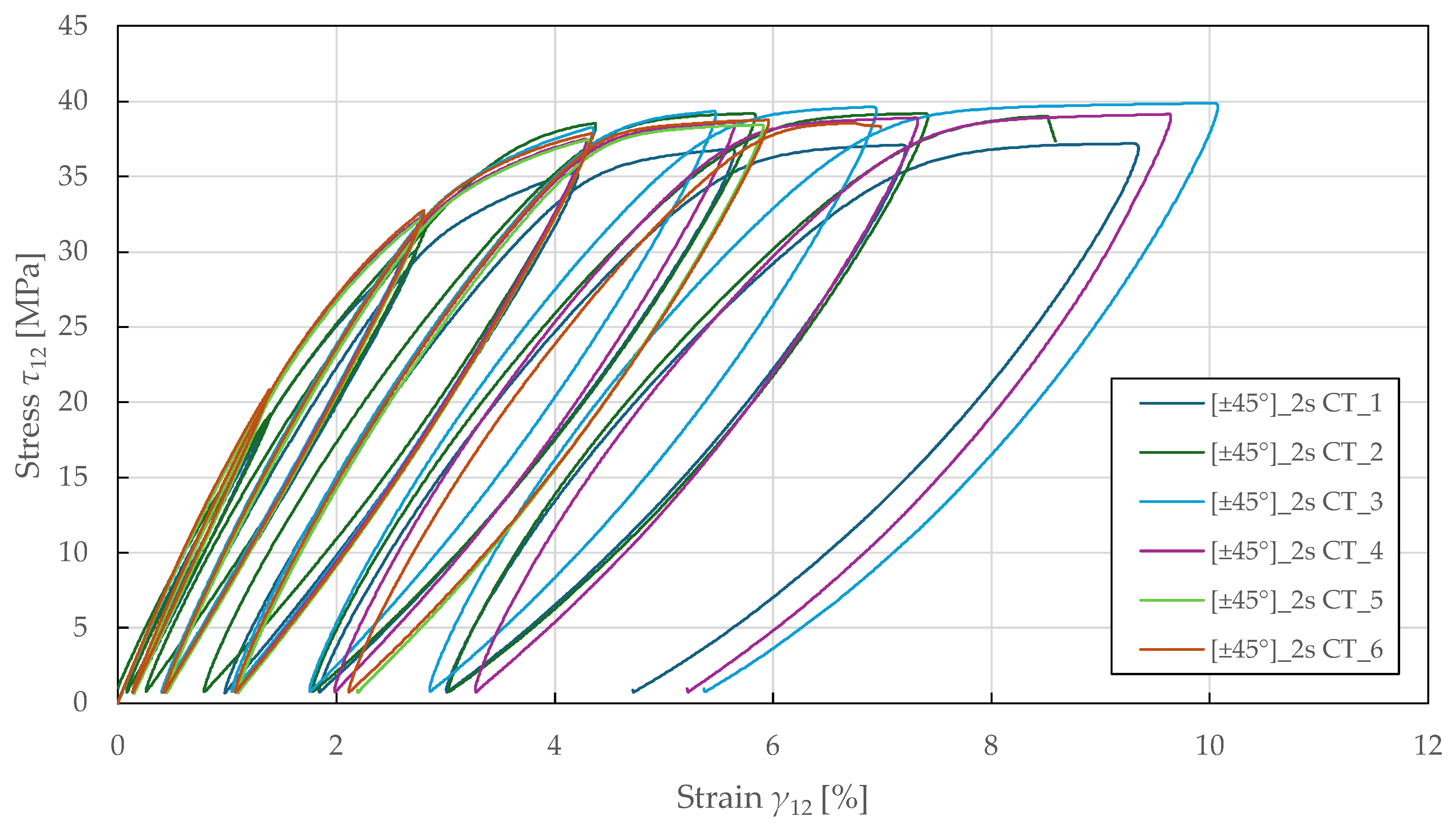

The in-plane shear damage and plasticity parameters were determined using

specimens subjected to cyclic tensile loading. The loading was controlled by extensometer displacement with an increment of 0.6 mm (equivalent to a strain of 0.8%). The resulting stress–strain curves are shown in

Figure 9.

Initially, the values of plastic and elastic shear strain and maximum shear stress were analysed from the stress–strain curves to calculate the shear modulus

in each cycle

. The undamaged shear modulus was obtained from the initial slope using LR (LSM) in the range of

MPa. By comparing the moduli, shear damage was determined from Equation (11):

This equation quantifies the shear damage variable by comparing the current degraded modulus to the initial undamaged modulus, providing a scalar measure of material stiffness loss ranging from 0 (undamaged) to 1 (complete damage).

Then, assuming the transverse damage is negligible for the specimens with

lay-up, the damage evolution law was obtained by substituting the shear thermodynamic force from Equation (5) into Equation (7):

The thermodynamic force represents the driving force for damage evolution, analogous to the energy release rate in fracture mechanics. It is calculated from the maximum stress state and the current damage level experienced by the material.

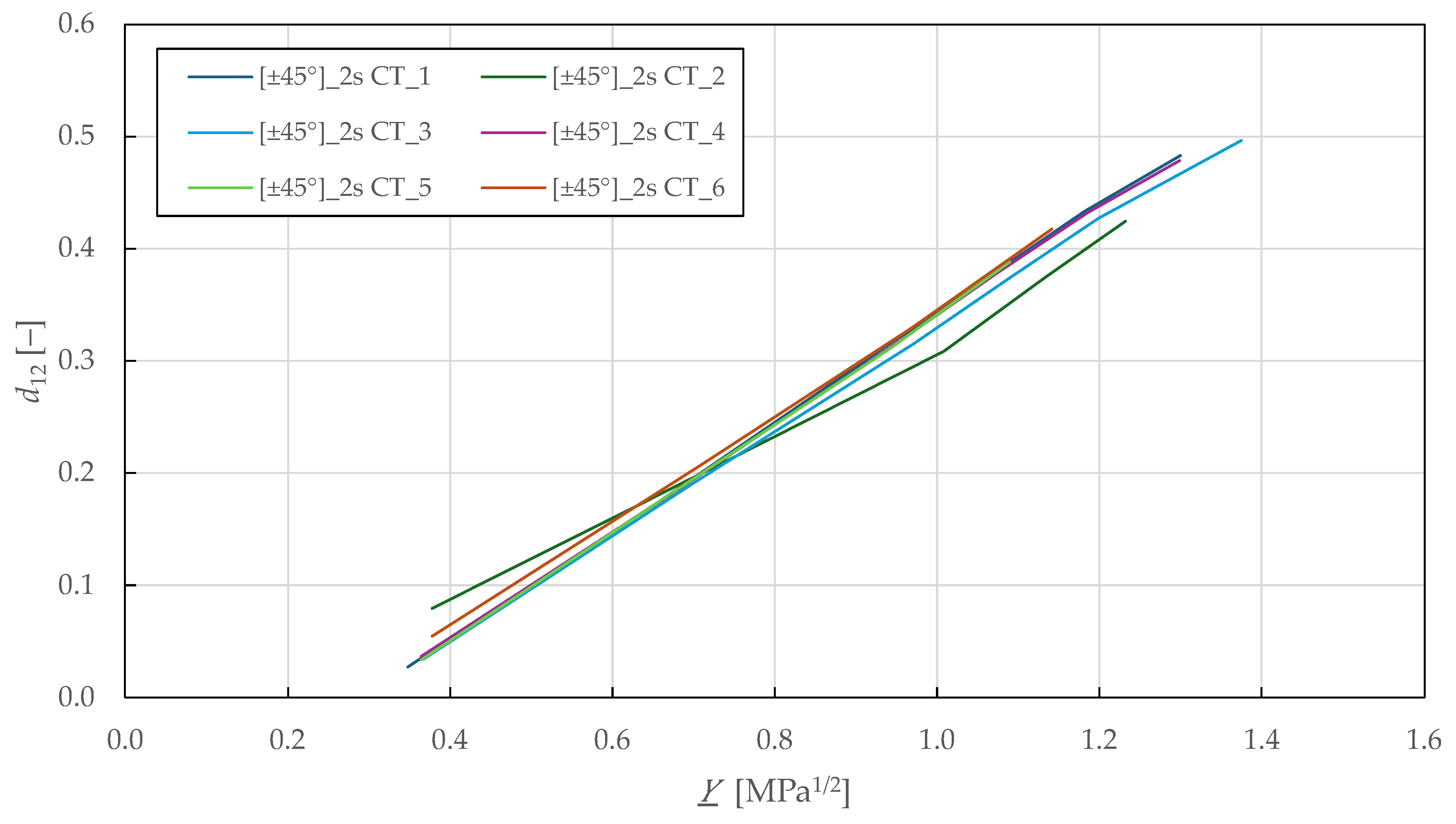

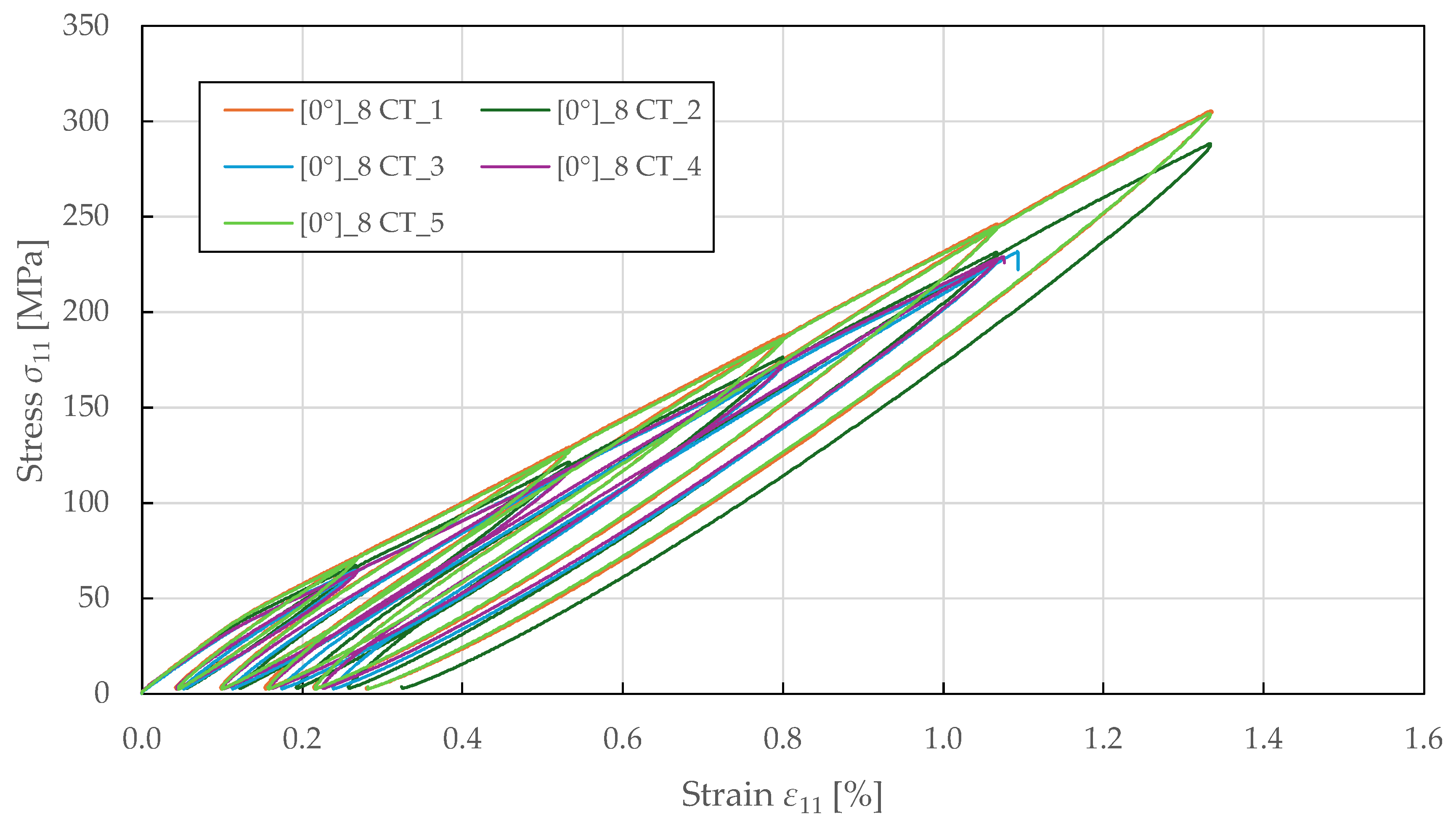

Figure 10 shows the

-

shear damage master curves, where a linear relationship is observed up to a shear damage of 0.47 ± 0.03 and thermodynamic force of 1.3 ± 0.04

. Then, LR (LSM) was used to fit the damage law in Equation (9) to the experimental data, showing a good repeatability of the results. The identified in-plane shear damage parameters for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 7.

To obtain the plasticity parameters, the plasticity threshold value was calculated by substituting the effective shear stress from Equation (14) into Equation (12):

This expression calculates the current yield stress, considering isotropic hardening, by accounting for the damage effect on the effective stress state. It represents the stress threshold that must be exceeded for continued plastic deformation to occur.

Considering only the in-plane shear strain rate to be non-zero for the specimens with the

lay-up, the accumulated plastic strain was obtained from Equation (15) as an area under the

-

curve:

The accumulated plastic strain is obtained by integrating the plastic strain rate weighted by the damage state. This scalar quantity characterises the total irreversible deformation history and governs the isotropic hardening.

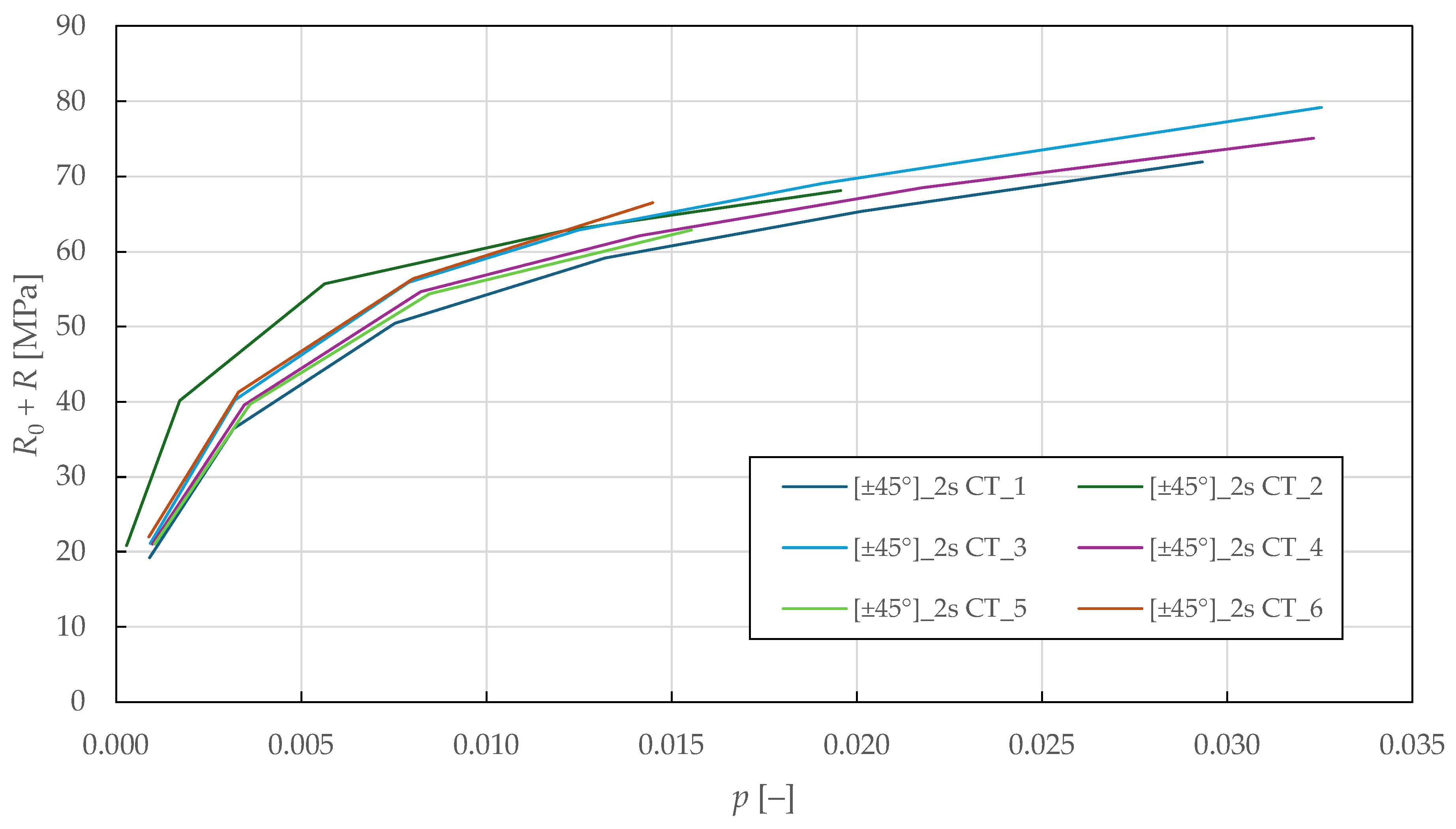

In

Figure 11, the

-

shear plasticity master curves are plotted. Then, LR (LSM) was used to fit the isotropic hardening power law in Equation (13) to the experimental data. The identified in-plane shear plasticity parameters for the CDM model are listed in

Table 7.

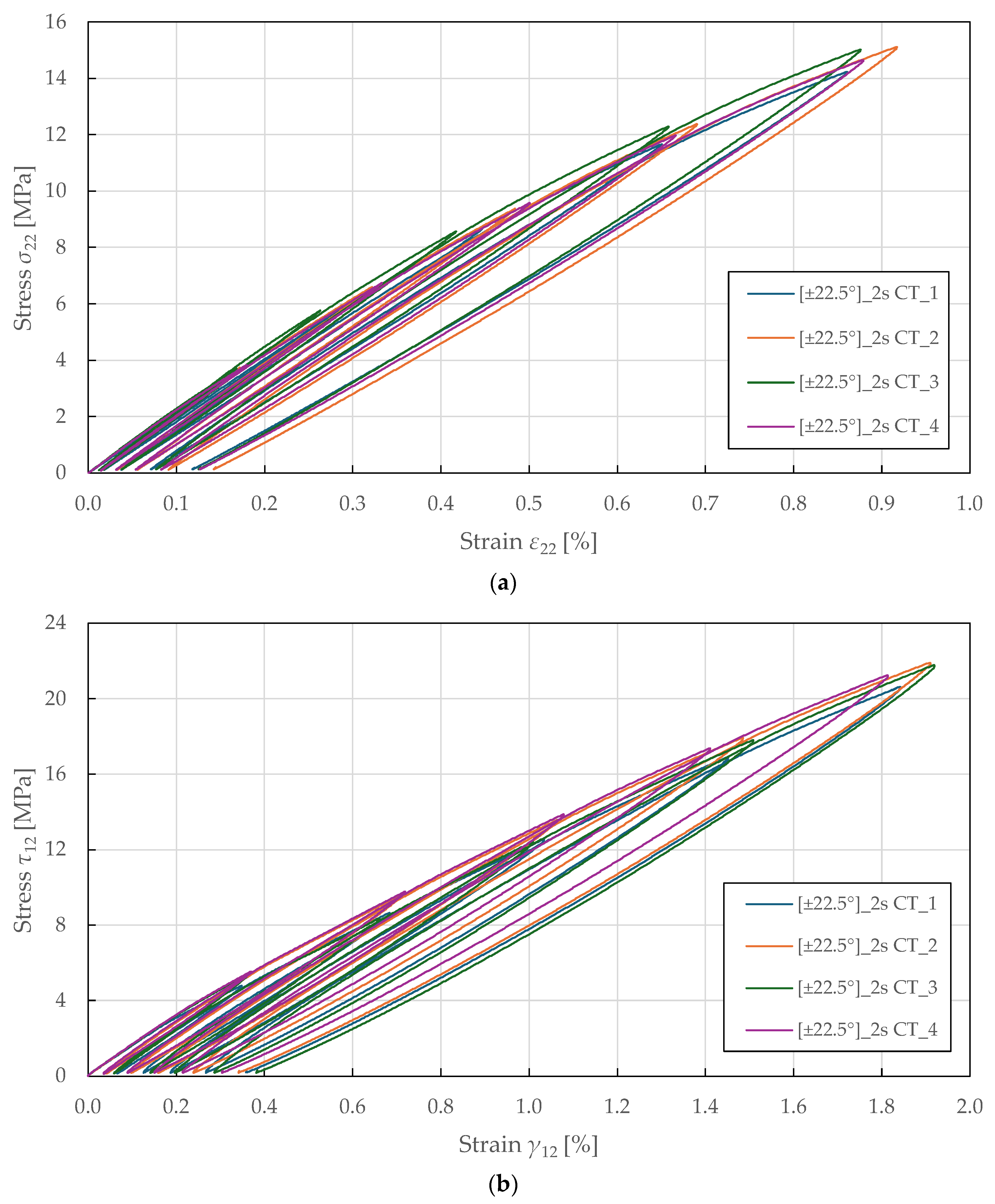

The shear-transverse damage and coupling parameters were identified from the cyclic tensile testing of specimens with

lay-up. The loading was controlled by extensometer displacement with an increment of 0.2 mm (equivalent to a strain of 0.27%). The principal stresses and strains for angle-ply laminates were calculated using classical laminate theory as described in [

74]:

where

,

, and

are variables describing the influence of ply angle and undamaged material properties as

These equations describe the transverse (22) and in-plane (12) stress–strain response of angle-ply laminates as a function of experimentally obtained axial stress (x) and biaxial strain (x,y), ply angle, and material properties in fibre (11), transverse (22), and in-plane (12) directions.

The resulting transverse and shear stress–strain curves are plotted in

Figure 12. For each i-th cycle, the transverse

and shear

moduli were determined as described in the previous section. The undamaged moduli were obtained from the initial slopes using LR (LSM) in the absolute stress range of 1 to 2 MPa. From there, the damage variables and thermodynamic forces were determined from Equations (4), (5), (10), and (11).

The shear-transverse damage-coupling parameter

is described by manipulating Equation (9) and substituting into Equation (7):

where

and

are parameters obtained from cyclic tensile testing on the

specimens (see

Table 7). In addition, a coupling parameter

was introduced to capture the relationship between shear and transverse damage as described in [

66]:

Subsequently, the shear-transverse plasticity coupling parameter

is derived by manipulating the yield conditions in Equation (17) and by substituting the effective stresses and strains from Equations (14) and (15):

The physical interpretation of these coupling parameters reflects the complex interaction between failure mechanisms in composite laminates. The parameter b2 quantifies how shear damage (fibre–matrix debonding) influences the evolution of transverse damage (matrix microcracking). The parameter b3 represents the ratio of transverse to shear damage accumulation rates, characterising the relative progression of these mechanisms. The parameter a governs the coupling between shear-transverse damage and plasticity through effective stress formulation, reflecting the internal friction mechanisms. These parameters are essential for accurately predicting the complex multi-axial behaviour of composite laminates under combined loading, with model sensitivity particularly pronounced for angle-ply laminates.

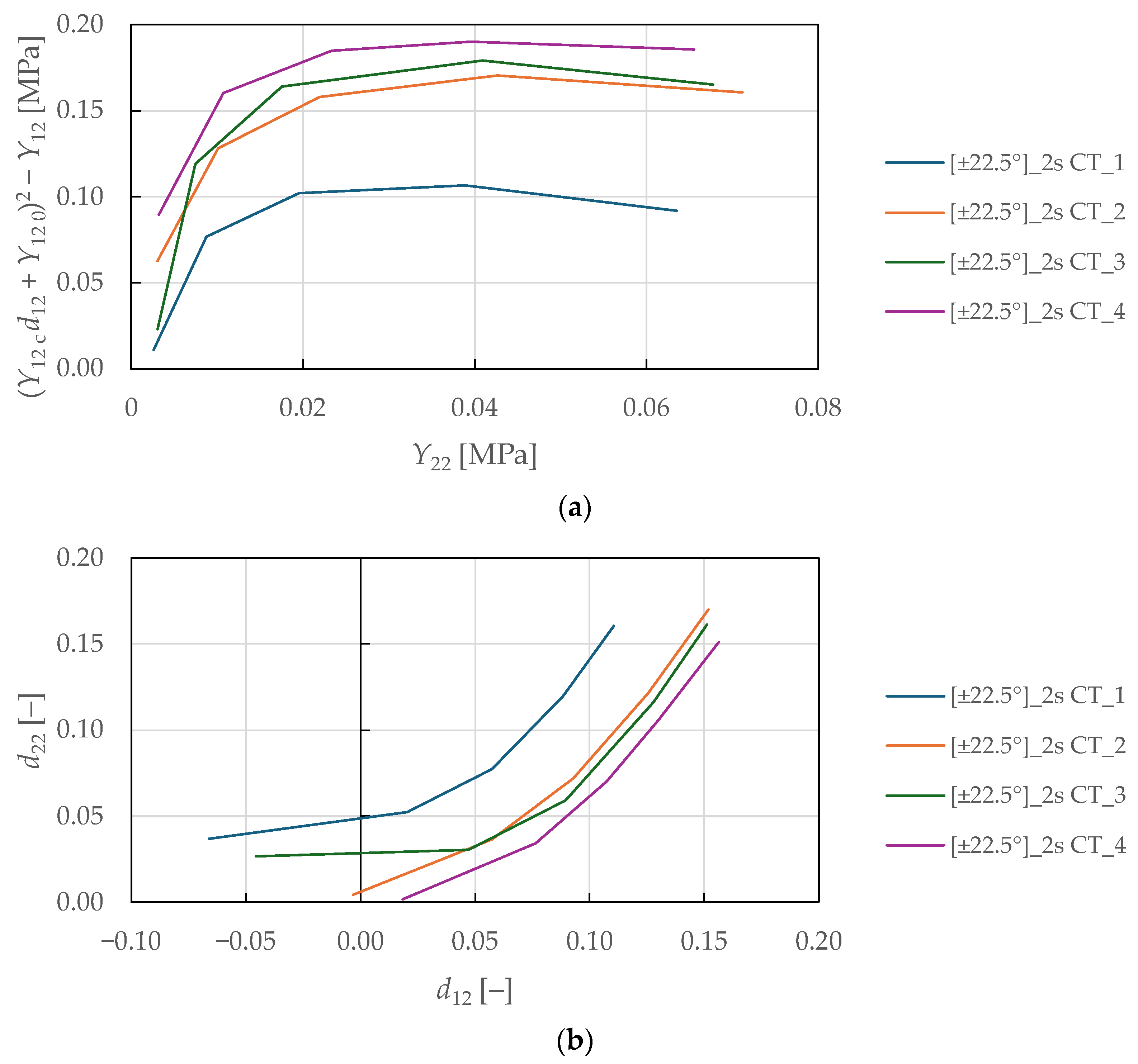

The coupling parameters represent the slope between the numerator and denominator, which was determined by fitting Equations (29)–(31) to the experimental data plotted in

Figure 13a,

Figure 13b, and

Figure 13c, respectively, using LR (LSM). A nonlinear behaviour was observed in the plotted curves for the shear-transverse damage-coupling parameters

and

, suggesting that damage coupling in FFRPs intensifies as damage accumulates. This behaviour differs from the linear coupling typically observed in synthetic fibre composites and reflects the complex hierarchical microstructure of natural fibres. Therefore, e.g., a bi-linear evolution law of the parameters would be more suitable for the damage modelling of FFRPs. The identified shear-transverse coupling parameters for the CDM model are listed in

Table 8.

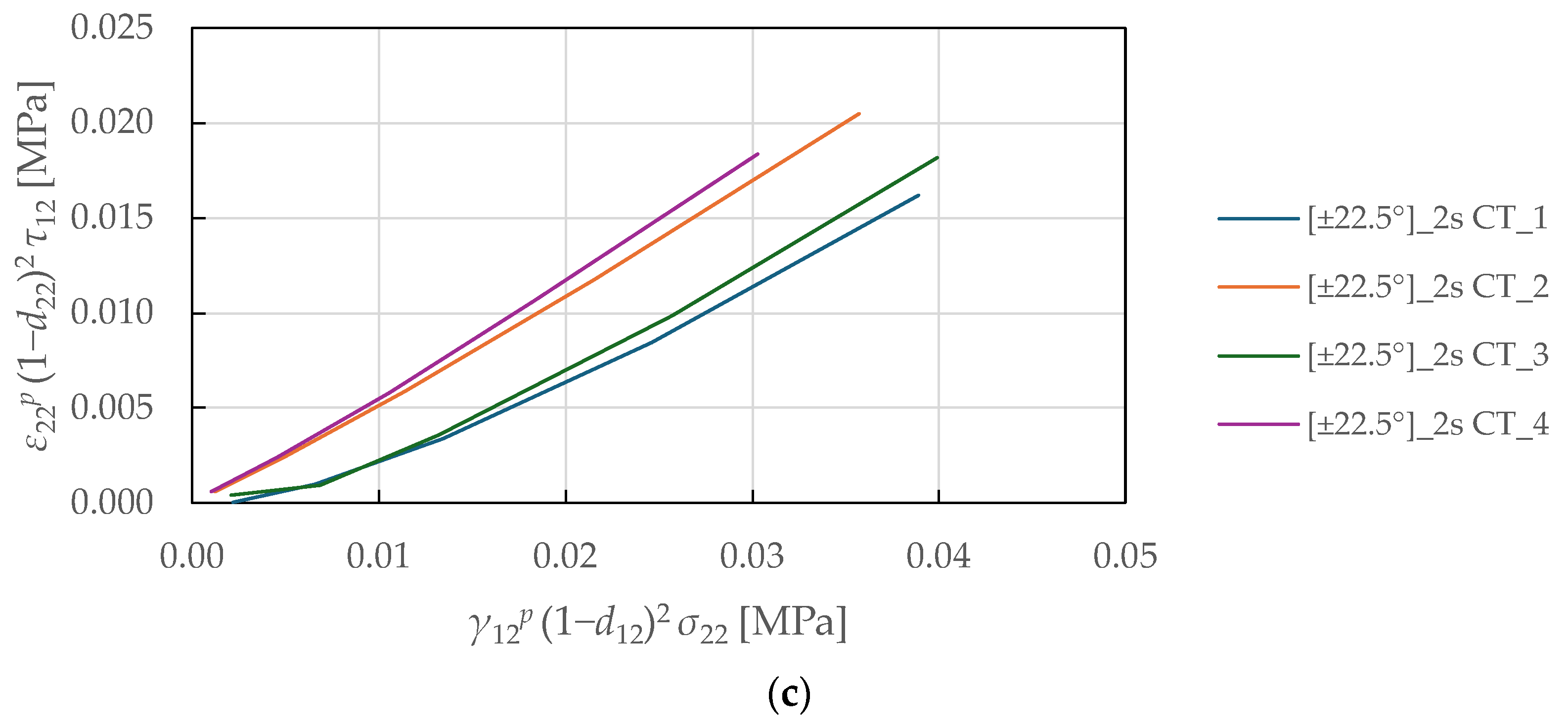

Considering the identified coupling parameters and damage evolution law in Equation (7), the

-

shear-transverse damage master curve is plotted in

Figure 14. The curves show a mostly linear relationship up to a transverse damage of 0.16 ± 0.01 and thermodynamic force of 0.52 ± 0.03

. Then, LR (LSM) was used to fit the damage law in Equation (8) to the experimental data. The identified shear-transverse damage parameters for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 8.

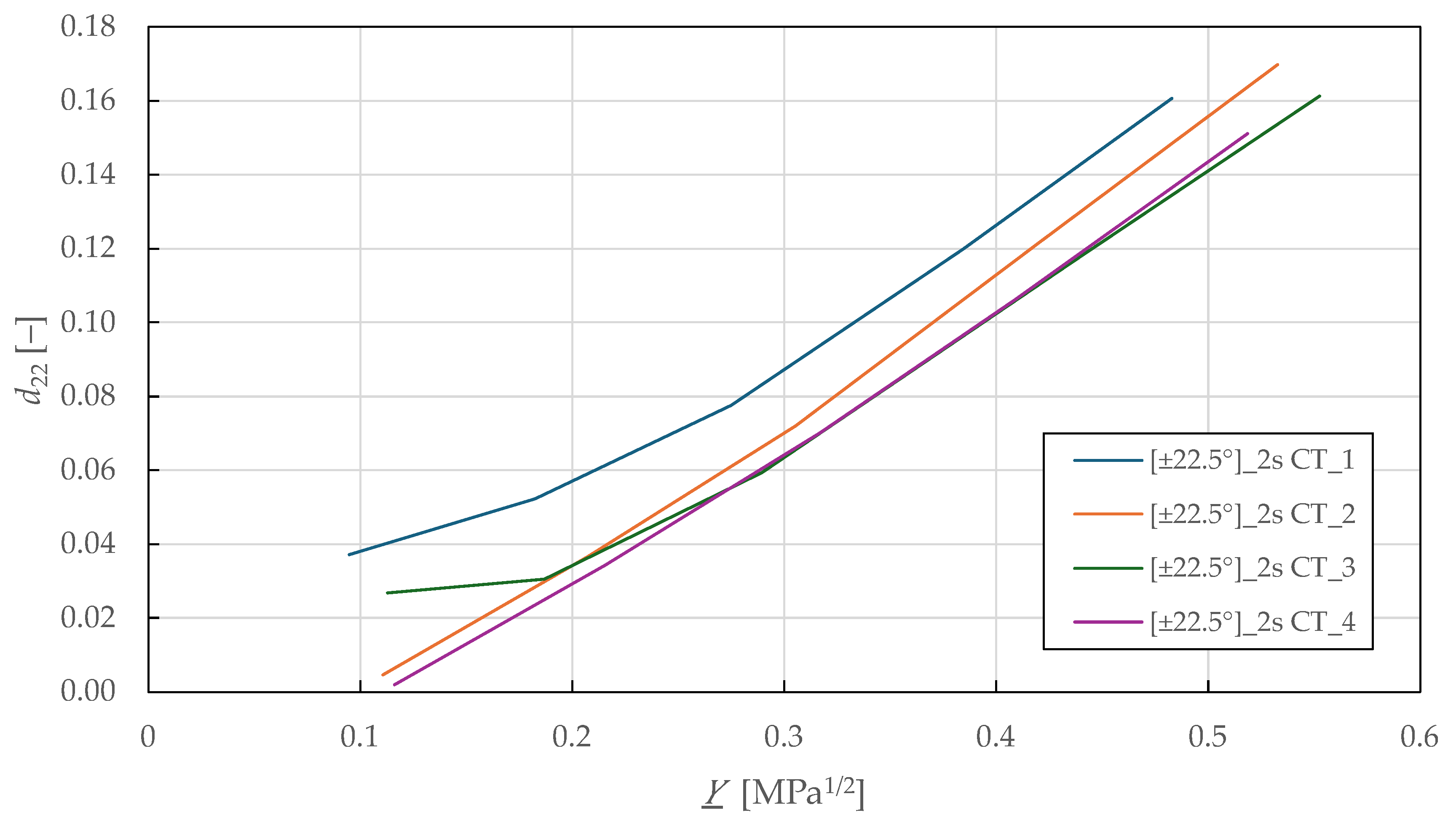

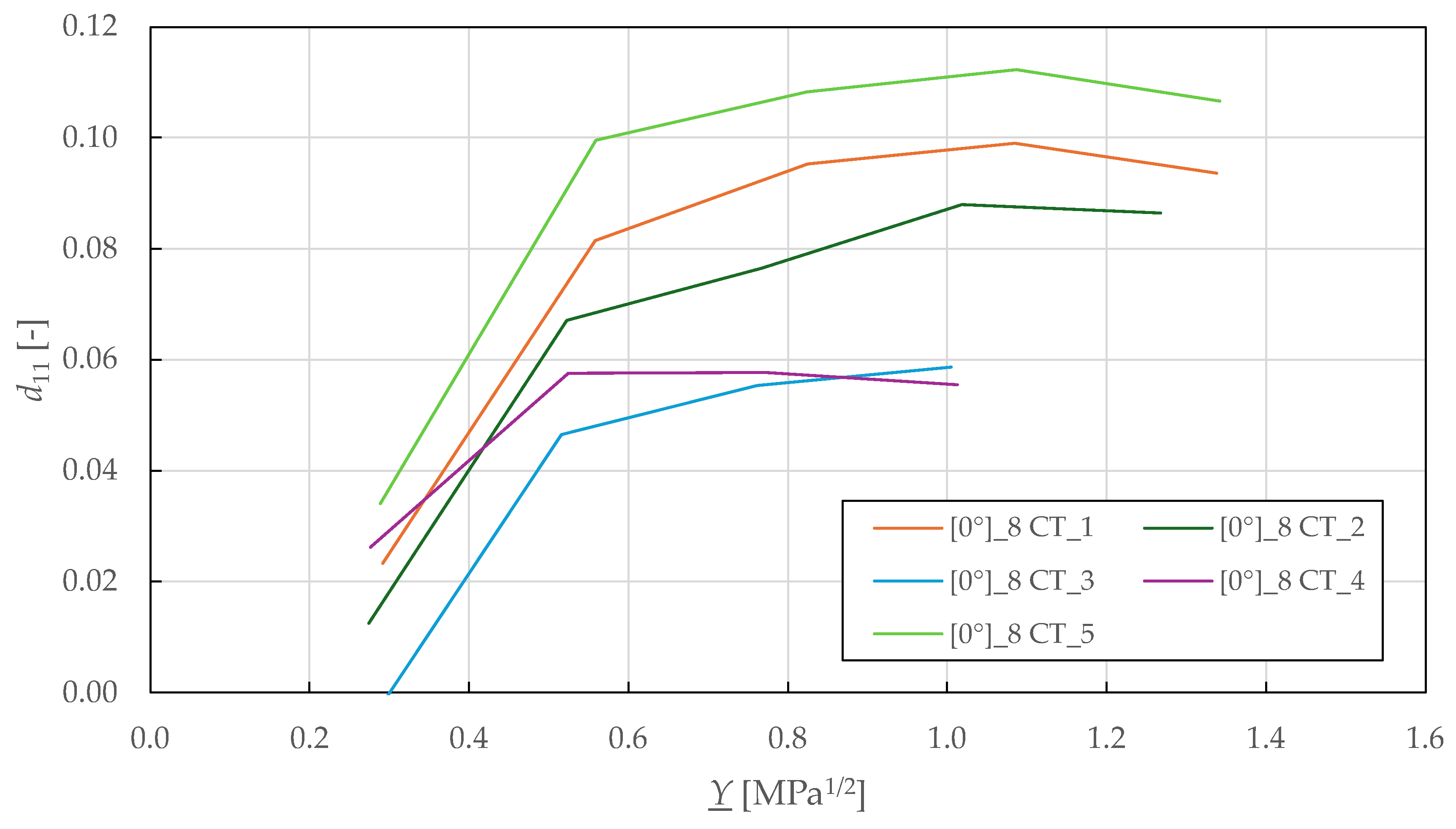

The fibre-direction damage parameters were identified from cyclic tensile testing on specimens with

lay-up. The loading was controlled by extensometer displacement with an increment of 0.2 mm (equivalent to a strain of 0.27%). The resulting stress–strain curves are shown in

Figure 15. During experimental testing, a progressive loss of stiffness was observed in each loading cycle, indicating a non-brittle failure.

Following the procedure described in the previous sections, the

-

fibre-direction damage master curves are plotted in

Figure 16. From there, the failure threshold in tension

was determined as the maximum observed thermodynamic force. This value was then adjusted for compression threshold

by considering the difference between the identified tensile and compressive strength (see

Table 2 and

Table 5). The identified fibre-direction damage parameters for the CDM model are summarised in

Table 9.