Abstract

The synthesis of polymer brushes on inorganic particles is an effective approach to surface modification. The polymer brushes on the surface endow the substrates with new surface properties. However, the lack of functional groups and the difficulty of surface modification have made it difficult to develop an effective method for the synthesis of polymer brushes on metal surfaces. Herein, a simple and versatile strategy for synthesizing polymer brushes on copper particles is reported. Tannic acid (TA) molecules are adsorbed onto the surfaces of copper particles, forming TA coatings. Quaternized poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate)-block-polystyrene (qPDMAEMA-b-PS) block copolymer (BCP) chains are grafted on the TA coatings through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interaction, and PS brushes are grafted on the copper particles. The effects of TA concentration on the adsorption of TA and PS brush synthesis are discussed. The PS brushes are able to form surface nanostructures on the copper particles through co-assembly with PDMAEMA-b-PS BCP chains. The effect of BCP concentration on the surface nanostructures is investigated. It is reasonable to expect that polymer brushes and surface nanostructures can be synthesized on different metal surfaces by using the TA-coating approach reported in this paper.

1. Introduction

The grafting of polymer brushes onto surfaces is an effective approach to the surface modification of inorganic particles [1,2,3,4,5]. Many properties of the particles, especially the dispersion and the stability of the particles in organic solvents, have been improved due to the synthesis of the polymer brushes on the surfaces. Polymer brushes refer to the polymer chains that are tethered to the solid surfaces at high grafting densities [6,7,8]. Polymer brushes can be synthesized by using the “grafting to” or “grafting from” methods [9,10,11,12]. In the “grafting to” approach, polymer chains are grafted to the surfaces at chain ends through chemical reactions or specific interactions between polymer chains and particle surfaces [13,14,15,16]. In the “grafting from” approach, polymer chains grow from the initiator or chain transfer agent (CTA)-modified solid surfaces [17,18,19,20,21].

In both the “grafting to” and “grafting from” methods, it is necessary to achieve surface functionalization in order to introduce reactive functional groups or initiator (or CTA) groups onto the surfaces. In the past few decades, many studies on surface functionalization have been conducted. In order to synthesize polymer brushes through click chemistry, azide groups (or alkynes) have been introduced onto the surfaces of substrates [22,23]. Thiol groups or pyridyl disulfide groups were prepared on the surfaces of particles, and polymer brushes on the particle surfaces were prepared through thiol chemistry [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) initiators or reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) CTAs were introduced onto the solid surfaces and polymer brushes were prepared by using the “grafting from” approach [31,32].

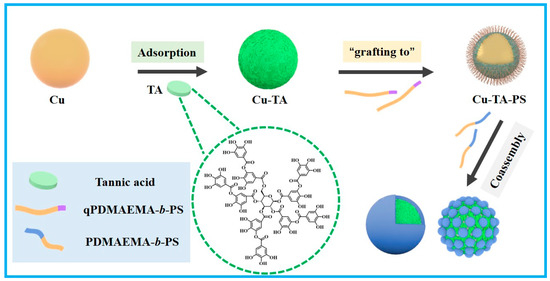

Although great success has been achieved in the synthesis of polymer brushes, it is difficult to synthesize polymer brushes on metal particles due to the difficulty of surface functionalization. TA contains a large number of phenolic hydroxyl groups in its chemical structure which have strong hydrogen bond interactions with amino groups. The phenol hydroxyl anions have strong electrostatic interactions with the positively charged quaternized polymer blocks [33,34]. Previously, it has been demonstrated that tannic acid (TA) has a high surface binding affinity to a wide range of material surfaces due to the catechol/pyrogallol groups on the structures. TA has been used as building blocks in the fabrication of multilayer films and hollow capsules [35]. In a previous concept study, TA was coated on the surface of silica particles, and PS brushes were prepared on the TA coatings [36]. In that approach, surface modification of the substrate was not necessary as the TA-coating approach provides a direct, simple and versatile method for the fabrication of polymer brushes on substrate surfaces. In this study, we demonstrate that polymer brushes can be fabricated on the surface of copper particles by using the TA-coating method and nanostructures are constructed through surface co-assembly with a copolymer. As shown in Scheme 1, TA is adsorbed onto the surface of copper particles through noncovalent-specific interactions (Cu-TA). The TA coatings are used as a platform for the synthesis of polymer brushes. Partially quaternized poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate)-block-polystyrene (qPDMAEMA-b-PS) block copolymer (BCP) chains are grafted onto the TA coatings through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, resulting in the synthesis of PS brushes on TA coatings (Cu-TA-PS). Due to the grafted hydrophobic polymer brushes on the metal surface, it is reasonable to expect that this technology will be applied for metal anti-corrosion [37,38,39]. Hollow capsules are obtained after etching copper particles with hydrochloric acid. It can be used as a drug storage space or a nanoreactor and has potential application value in the fields of drug-controlled release, biological energy storage and nano-catalysis.

Scheme 1.

A schematic illustration of the coating of copper particles with TA, the synthesis of PS brushes on copper particles by using the “grafting to” approach and the fabrication of the surface nanostructures by using the co-assembly approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Styrene (98%, Tianjin Chemical reagent Company, Tianjin, China) and DMAEMA (98%, Aldrich) were purified by being passed through basic Al2O3 columns and distilled under reduced pressure. 2,2′-Azoisobutyronitrile (AIBN, 98%, Guo Yao Chemicals) was recrystallized in ethanol and dried under reduced pressure. TA was purchased from Aldrich and used as received. The synthesis of 4-cyanopentanoic acid dithiobenzoate (CPADB) was reported in our previous publication [29]. Spherical copper particles with an average size of 400 nm were purchased from Macklin and used as received. All of the solvents used in this study were purified before use.

2.2. Synthesis of PDMAEMA-b-PS

PDMAEMA-b-PS was synthesized through sequential RAFT polymerization. PDMAEMA-CTA was prepared through RAFT polymerization of DMAEMA using CPADB as a chain transfer reagent. The typical procedure is described as follows. CPADB (223 mg, 0.800 mmol), DMAEMA (6.2 g, 40 mmol) and AIBN (19.7 mg, 0.120 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of 1,4-dioxane in a 50 mL Schlenk flask. RAFT polymerization of DMAEMA was carried out at 70 °C for 6 h after three freeze–pump–thaw cycles. PDMAEMA-CTA was obtained by precipitating it into a 10-fold excess of hexane and drying it under reduced pressure at room temperature. PDMAEMA-b-PS was prepared through RAFT polymerization of styrene using PDMAEMA-CTA as a macromolecular chain transfer reagent. Styrene (2.77 g, 26.6 mmol), PDMAEMA-CTA (200 mg, 0.0440 mmol) and AIBN (1.0 mg, 0.0060 mmol) were dissolved in 2.5 mL of toluene in a 10 mL Schlenk flask. RAFT polymerization of styrene was carried out at 90 °C for 12 h after three freeze–pump–thaw cycles. PDMAEMA-b-PS was obtained by precipitating it into a 10-fold excess of hexane and drying it under reduced pressure at room temperature.

2.3. Synthesis of TA-Modified Copper Particles (Cu-TAs)

Copper particles (10 mg) were dispersed in 1 mL of a TA aqueous solution at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 h. After being washed with ultrapure water and THF, Cu-TAs were collected and dried under reduced pressure. The amount of TA adsorbed on copper particles was determined by UV–vis.

2.4. Synthesis of Polymer Brushes on Cu-TA (Cu-TA-PS)

There were two steps in the synthesis of polymer brushes on Cu-TA. In the first step, PDMAEMA27-b-PS130 BCPs were quaternized with methyl iodide; and in the second step, polymer brushes on Cu-TA were synthesized by anchoring the quaternized BCP chains onto the surfaces of Cu-TA through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding. The typical procedures are described as follows. PDMAEMA27-b-PS130 (20 mg) was dissolved in 20 mL of DMF in a 50 mL flask, 20 µL of iodomethane was dissolved in 1.98 mL of DMF (0.01 µL/mL) and 94 μL of the solution was added to the polymer solution. A quaternization reaction was performed at 40 °C in the dark for 24 h. After the reaction, partially quaternized BCPs (qPDMAEMA27-b-PS130) were obtained. Cu-TA (50 mg) was added to the polymer solution under ultrasonication, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After the adsorption, copper particles with polymer brushes on the surfaces were collected through centrifugation. After being washed with DMF five times, copper particles with polymer brushes (Cu-TA-PS) were dried under reduced pressure.

2.5. Co-Assembly of Cu-TA-PS and PDMAEMA-b-PS

A typical surface co-assembly procedure is described as follows. Cu-TA-PS (5 mg) and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 (1.0 mg) were dispersed/dissolved in 0.5 mL of THF. Methanol (3.5 mL) was added to the mixture at a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min. After surface co-assembly, the copper particles were washed with methanol three times and dried under reduced pressure. The hybrid particles with surface nanostructures (Cu-TA-PS/PDMAEMA-b-PS) were collected.

2.6. Fabrication of Hollow Capsules

Hollow capsules were prepared by etching copper particles with a HCl aqueous solution. In a flask, Cu-TA-PS/PDMAEMA-b-PS (5 mg) was dispersed in 1 mL of a HCl aqueous solution (pH = 1) and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After the reaction, hollow capsules were collected through centrifugation and washed with methanol.

2.7. Characterization

1H NMR measurements were performed on a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz spectrometer using deuterated chloroform as the solvent. The apparent molecular weight and distribution of BCPs were characterized by using size exclusion chromatography. The details about the equipment can be found in our previous publication [29]. The ultraviolet absorption spectrum was collected on a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer with a wavelength of 190–800 nm. Quartz cuvettes with a width of 2 nm were used. The surface nanostructures on copper particles were analyzed under the Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN electron microscope operating at 200 kV. The TEM specimens were prepared by depositing diluted solutions of the samples on carbon-coated copper grids and evaporating the solvent at room temperature. SEM images of the copper particles were obtained by using the Apreo S LoVac Thermo Scientific scanning electron microscope. SEM specimens were prepared by depositing diluted solutions of the samples on a silicon wafer and evaporating the solvent at room temperature. The zeta potential values of the copper particles were obtained on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS equipped with a 633 nm He-Ne laser. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves were obtained by using a Synchronous Thermal Analyzer (STA 499 F5). Before measurements, all of the samples were dried at 70 °C for 12 h and at room temperature for 24 h under reduced pressure. All of the samples were heated to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 K/min under nitrogen atmosphere. The data of TGA are normalized at 100 °C.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Polymer Brushes on TA-Coated Copper Particles (Cu-TA-PSs)

PDMAEMA-b-PS BCPs were synthesized through RAFT polymerization. The average repeating unit numbers of PDMAEMA and PS blocks were determined by 1H NMR. Two BCPs with different PDMAEMA block lengths and a similar PS block length, PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 and PDMAEMA27-b-PS130, were synthesized in this study. The 1H NMR result and size exclusion chromatography (SEC) curves of the BCPs are shown in Figure S1. The quaternized PDMAEMA27-b-PS130 (qPDMAEMA27-b-PS130) was synthesized through quaternization reactions between the BCP and methyl iodide [40,41]. The quaternization degree of the PDMAEMA27 block was around 50%. The TEM image of the copper particles used in this study is shown in Figure S2. The average size of the particles was determined to be around 400 nm.

After dispersing the copper particles in aqueous TA solutions of different concentrations, they were stirred for 10 h in the dark at room temperature. The amount of TA adsorbed on the surface of the copper particles was determined by UV–vis. The absorption spectra of TA at different concentrations and a standard curve are shown in Figure S3. We investigated the effect of the initial TA concentration on adsorption. In the adsorption tests, the concentration of copper particles was set at 10 mg/mL. The amount of TA adsorbed onto the copper particles at different TA concentrations was determined based on the standard curve. As shown in Figure 1a, the adsorption of TA on the surface of copper particles increased linearly, with the initial concentration at low concentrations, with a turning point at a concentration of 0.018 mg/mL. Above the critical concentration, the increase in the amount of adsorbed TA on the copper particles at this TA concentration is not as big as that in the low-concentration regime. When the initial concentrations of TA are 0.0025, 0.0050, 0.010 and 0.020 mg/mL, the surface densities of TA on the copper particles are calculated to be 0.36, 0.79, 1.08 and 2.36 molecules/nm2, respectively. Copper particles with a 0.36 molecules/nm2 surface density of TA are denoted as Cu-0.36TA. The radius of the projected area of a TA molecule is reported to be approximately 0.8 nm [42]; thus, the percentage of TA coverage on the Cu-0.36TA surface can be estimated to be about 76%. In this study, Cu-0.36TA was used in the synthesis of polymer brushes and surface nanostructures.

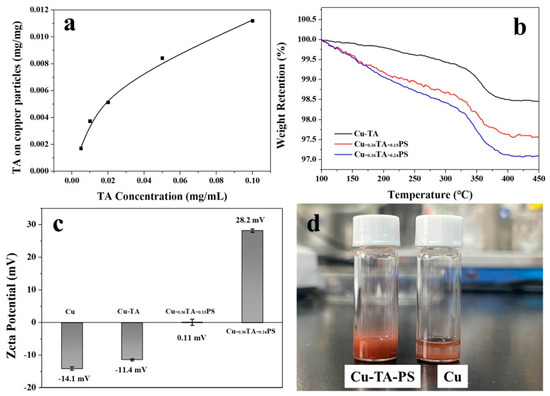

Figure 1.

(a) The amounts of TA that is adsorbed on the surfaces of copper particles at different concentrations of TA; (b) thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves of Cu-TA, Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS; (c) zeta potential values of the copper particles, Cu-TA, Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS, and (d) photographs of copper and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS particles in toluene.

To prepare polymer brushes, qPDMAEMA27-b-PS130 was dissolved in DMF, and Cu-0.36TA particles were added in the polymer solution under stirring. After centrifugation, copper particles with polymer PS brushes on the TA coatings were obtained (Cu-0.36TA-PS). On the surfaces of the particles, qPDMAEMA27 blocks were grafted onto the TA coatings through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding, and PS brushes on Cu-0.36TA were prepared (Scheme 1). It is reasonable to expect that the initial concentration of qPDMAEMA27-b-PS130 exerts a significant effect on the grafting density of PS brushes. Herein, polymer brushes were prepared at two different BCP concentrations, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves of Cu-0.36TA and the two different copper particles with PS brushes are shown in Figure 1b. The Cu-0.36TA particles have a total weight loss of 1.5 wt% in the range of 100–450 °C, and the two different particles with PS brushes have 2.25 and 2.88 wt% weight losses, respectively. Based on the TGA results, the surface densities of PS brushes on Cu-0.36TA particles are calculated to be 0.15 and 0.24 chains/nm2, respectively. The copper particles with two different PS surface densities are denoted as Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS, respectively.

The surface modification of copper particles by grafting qPDMAEMA27-b-PS130 results in large changes in the surface charges. The zeta potential values of the native copper particles, Cu-0.36TA, Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS, are shown in Figure 1c. The zeta potential of the native copper particles is -14.1 mV, and it changes to -11.4 mV after the coating of TA molecules on the surface (Cu-0.36TA). Upon the adsorption of the quaternized BCP chains, the zeta potentials of Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS increase to 0.1 and 28.2 mV due to the positively charged qPDMAEMA blocks on the particle surfaces. The grafting of polymer brushes significantly improves the dispersion of copper particles in organic solvents. As shown in Figure 1d, upon dispersion of the native copper particles in toluene, the particles precipitate from the solution immediately; in contrast, Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS particles can disperse in toluene for a while.

3.2. Construction of Surface Nanostructures on TA-Coated Copper Particles

In previous studies, it was reported that polymer brushes bonded covalently can be used to construct surface nanostructures by using surface co-assembly methods, and a variety of surface nanostructures including spherical surface micelles (s-micelles), worm-like structures and layered surface structures are formed. Herein, surface co-assembly of Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS (or Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS) and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 at different BCP concentrations was performed in a THF/methanol mixture. To perform surface co-assembly, 10 mg of Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS (or Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS) was dispersed in 1.0 mL of THF, and varying amounts of PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 was dissolved in the solution. Excess methanol (7.0 mL) was added in a dropwise manner to the mixture under stirring. Copper particles with surface nanostructures were collected after centrifugation. As shown in Scheme 1, upon the addition of methanol, the PS brushes on the surface of the copper particles and the PS blocks in the BCP collapsed to form the core of the surface nanostructures, and the PDEMA blocks stabilized the nanostructures by stretching outwards.

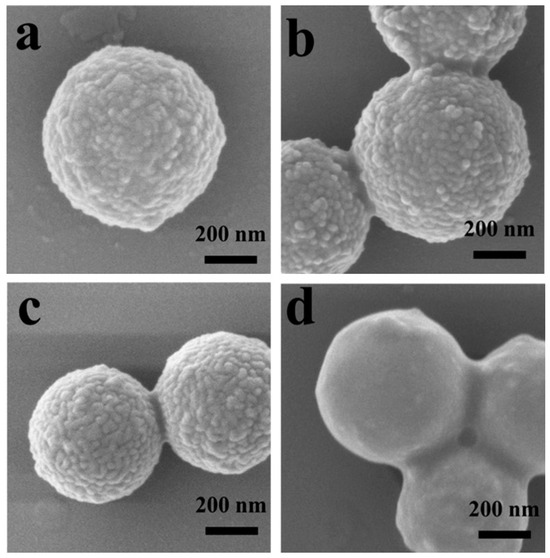

Figure 2 shows the SEM images of surface structures formed by Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 at different BCP concentrations. Spherical s-micelles are formed at BCP concentrations of 0.25, 0.37 and 0.50 mg/mL, and layered structures are formed at 0.63 mg/mL, indicating that s-micelles are formed at low BCP concentrations and layered nanostructures are formed at high BCP concentrations. It is noted that at 0.50 mg/mL, short worm-like s-micelles are also observed (Figure 2c). The formation of worm-like structures is attributed to the fusion of the neighboring isolated s-micelles formed at a high BCP concentrations. In a previous study, it was reported that with an increase in BCP concentration, the surface morphology experienced a change from isolated s-micelles to large-sized s-micelles, then to worm-like structures and finally to layered nanostructures [34]. Herein, with an increase in BCP concentration, more BCP chains are involved in the surface co-assembly; and in order to accommodate “free” BCP chains in the surface co-assembly process, short worm-like s-micelles and layered nanostructures are formed at high BCP concentrations.

Figure 2.

SEM images of surface nanostructures on TA-coated copper particles formed through surface co-assembly of Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 at BCP concentrations of (a) 0.25, (b) 0.37, (c) 0.50 and (d) 0.63 mg/mL. To fabricate surface nanostructures, Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and different amounts of PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 were dissolved in THF and seven-fold volumes of methanol were added into solutions.

The SEM images of surface nanostructures formed through the co-assembly of Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 at different BCP concentrations are shown in Figure 3. At 0.13 mg/mL, spherical s-micelles are observed on the copper particles, and layered structures are formed at a BCP concentration above 0.25 mg/mL. In comparison with Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS, the formation of layered structures on Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS is favored at the same BCP concentration. The grafting density of PS plays an important role in the fabrication of surface nanostructures. During surface co-assembly, PS brushes co-collapse with PS blocks to form the core of the s-micelles, and PDMAEMA blocks stabilize the nanostructures. As the grafting density of PS brushes increases, more BCP chains are required to stabilize the nanostructure during surface co-assembly. The layered nanostructures are able to accommodate more BCP chains than the spherical s-micelles, so the formation of the layered structures is favored on Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS at the same concentration of BCP.

Figure 3.

SEM images of surface nanostructures on TA-coated copper particles formed through surface co-assembly of Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 at BCP concentrations of (a) 0.13, (b) 0.25, (c) 0.63 and (d) 1.2 mg/mL. Scale bars in images represent 200 nm.

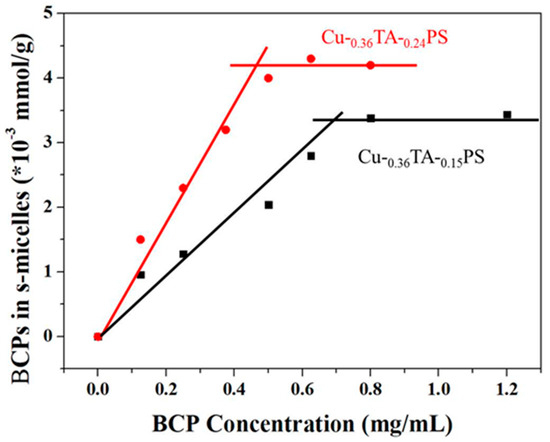

In order to determine the amount of BCP chains taking part in surface co-assembly, the copper particles with surface nanostructures were dispersed in DMF, and the BCP chains in the nanostructures were released into the solution. The “free” BCP contents in the solution were determined by UV–vis after centrifugation of the copper particles. The absorption spectra of BCP at different concentrations and a standard curve are shown in Figure S4. Figure 4 shows the contents of free BCP chains in the nanostructures on Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS formed at different BCP concentrations. Because of the higher grafting density of polymer brushes on the particles, at the same BCP concentration, more BCP chains are involved in the surface co-assembly on Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS than on Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS. On both plots, the content of BCP in the nanostructures increases with low BCP concentrations and remains constant after reaching a critical value. The amount of BCP chains involved in the surface self-assembly on the copper particles is related to the surface ratio of the particles and the grafting density of PS. A higher grafting density of PS is favorable for the adsorption of BCP chains onto the particle surfaces. The critical values on the plots represent the saturation concentrations of the BCP chains on the surfaces, and no more BCP chains take part in the surface co-assembly above the critical values.

Figure 4.

Amounts of PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 BCP involved in surface co-assemblies with Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS at different BCP concentrations.

3.3. Synthesis of Hollow Capsules

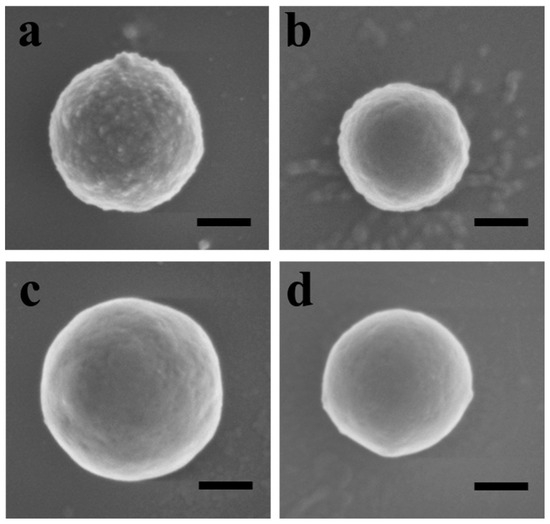

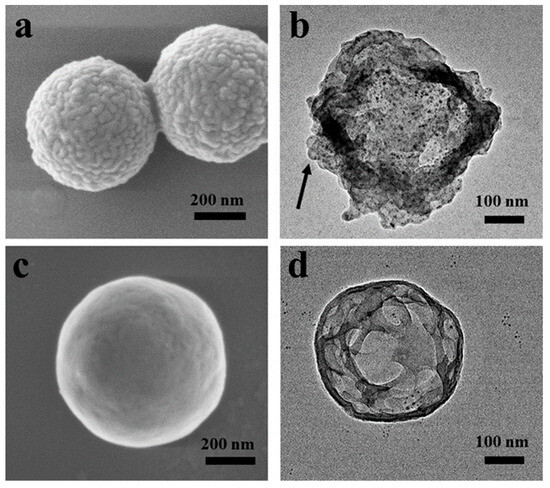

Inorganic particles with polymer coatings on the surfaces can be used as templates for the synthesis of hollow capsules. Herein, Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS and Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS particles with surface nanostructures are used as templates and hollow capsules are prepared by etching the copper particles with hydrochloric acid. Figure 5a shows the SEM images of copper particles with surface nanostructures self-assembled by PS brushes on Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS particles and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136. On the copper surfaces, spherical s-micelles formed by PS brushes and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 BCP chains are observed. Copper particles were etched with HCl acid and hollow capsules were obtained. As indicated by an arrow, s-micelles are located at the surfaces of the hollow capsules (Figure 5b), which suggests that the surface structures are maintained in the etching process. Figure 5c represents the SEM images of copper particles with surface nanostructures self-assembled by PS brushes and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 on Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS particles. Layered nanostructures are formed on the surfaces of the particles. After etching the copper particles, hollow capsules are formed (Figure 5d). TA molecules form coatings on the surfaces of the copper particles. Upon etching the copper particles with HCl acid, copper ions are produced, which form complexes with TA molecules on the coatings and result in the formation of the cross-linked coatings. The surface of the hollow capsules is composed of the surface nanostructures, spherical s-micelles or layered nanostructures, which are anchored to the TA coatings through the electrostatic interaction.

Figure 5.

Copper particles with surface nanostructures self-assembled by PS brushes on Cu-0.36TA-0.15PS particles and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 before (a) and after (b) etching with hydrochloric acid, and copper particles with surface nanostructures self-assembled by PS brushes on Cu-0.36TA-0.24PS particles and PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 before (c) and after (d) etching with hydrochloric acid. Images (a,c) are SEM images and (b,d) are TEM images.

4. Conclusions

TA molecules can be adsorbed onto copper particles, which leads to the formation of TA coatings. PS brushes can be synthesized on the TA coatings through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding between qPDMAEMA27-b-PS130 and the TA coatings. The PS brushes on the copper surfaces are able to achieve surface co-assembly with “free” BCP chains and surface nanostructures are fabricated on the copper particles. The PS grafting density exerts influence on the amount of BCP in the surface nanostructures and on the surface morphology. After etching the copper particles with HCl acid, hollow capsules are obtained. The surface nanostructures on the particles are maintained in the etching process. The copper particles with PS brushes will find applications for many different purposes. This study provides a versatile method for the synthesis of polymer brushes on metal surfaces. It is reasonable to expect that the TA-coating approach will find applications in achieving the anti-corrosion of metals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polym16111587/s1, Figure S1: (a) 1H NMR spectrum of PDMAEMA27-b-PS130 and (b) size exclusion chromatography (SEC) curves of PDMAEMA50-b-PS136, PDMAEMA27-b-PS130 and their precursors; Figure S2: TEM image of commercial copper particles; Figure S3: (a) Absorption of TA at different concentrations, (b) standard curve of absorption vs. TA concentration; Figure S4: (a) Absorption of PDMAEMA50-b-PS136 BCP at different concentrations, (b) standard curve of absorption vs. BCP concentration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; Methodology, C.W.; Software, C.W.; Formal analysis, C.W.; Investigation, C.W.; Data curation, C.W.; Writing—original draft, H.Z.; Writing—review & editing, H.Z.; Supervision, H.Z.; Project administration, H.Z.; Funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 51973094), the Science and Technology Committee of Tianjin under contract 20JCYBJC01520 and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Milner, S.T. Polymer brushes. Science 1991, 251, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Brittain, W.J. Polymer brushes: Surface-immobilized macromolecules. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2000, 25, 677–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, P.; Merlitz, H.; Sommer, J.-U.; Stamm, M. Polymer brushes for surface tuning. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhayo, A.M.; Yang, Y.; He, X. Polymer brushes: Synthesis, characterization, properties and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 130, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wei, Q.; Sheng, W.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F.; Li, B. Driving polymer brushes from synthesis to functioning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202219312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbey, R.; Lavanant, L.; Paripovic, D.; Schüwer, N.; Sugnaux, C.; Tugulu, S.; Klok, H. Polymer brushes via surface-initiated controlled radical polymerization: Synthesis, characterization, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 5437–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H. Polymer brushes and surface nanostructures: Molecular design, precise synthesis, and self-assembly. Langmuir 2024, 40, 2439–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, N. Brush-like polymers: Design, synthesis and applications. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10484–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansky, P.; Liu, Y.; Huang, E.; Russell, T.P.; Hawker, C. Controlling polymer-surface interactions with random copolymer brushes. Science 1997, 275, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueckel, T.; Luo, X.; Aly, O.F.; Macfarlane, R.J. Nanoparticle brushes: Macromolecular ligands for materials synthesis. Accounts Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; He, J.; Nie, Z. Polymer-guided assembly of inorganic nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 465–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, S.; Osborne, V.L.; Huck, W.T.S. Polymer brushes via surface-initiated polymerizations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionov, L.; Sidorenko, A.; Stamm, M.; Minko, S.; Zdyrko, B.; Klep, V.; Luzinov, I. Gradient mixed brushes: “Grafting to” approach. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 7421–7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Penn, L.S. Dense tethered layers by the “grafting-to” approach. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 4837–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdyrko, B.; Luzinov, I. Polymer brushes by the “grafting to” method. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Schmitt, S.K.; Choi, J.W.; Krutty, J.D.; Gopalan, P. From self-assembled monolayers to coatings: Advances in the synthesis and nanobio applications of polymer brushes. Polymers 2015, 7, 1346–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, A.J.; Seymour, B.T.; Zhao, B. Characterizing polymer-grafted nanoparticles: From basic defining parameters to behavior in solvents and self-assembled structures. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 6391–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Dong, A.; Luan, S.; Yin, J. Advances in design and biomedical application of hierarchical polymer brushes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 118, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, K.; Morinaga, T.; Koh, K.; Tsujii, Y.; Fukuda, T. Synthesis of monodisperse silica particles coated with well-defined, high-density polymer brushes by surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 2137–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Song, X.; Tang, T.; Zhao, H. Macromolecular brushes synthesized by “grafting from” approach based on “click chemistry” and RAFT polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppe, J.O.; Ataman, N.C.; Mocny, P.; Wang, J.; Moraes, J.; Klok, H.-A. Surface-initiated controlled radical polymerization: State-of-the-art, opportunities, and challenges in surface and interface engineering with polymer brushes. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 1105–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Bao, H.; Sahoo, N.G.; Wu, T.; Li, L. Water-soluble poly(n-isopropylacrylamide)–graphene sheets synthesized via click chemistry for drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 2754–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, X.; Yuan, L.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Ji, R.; Zhao, H. Synthesis of PNIPAM polymer brushes on reduced graphene oxide based on click chemistry and RAFT polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H. Surface nanostructures based on assemblies of polymer brushes. Chempluschem 2020, 85, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Li, Z.-W.; Zhao, H. Patchy micelles based on coassembly of block copolymer chains and block copolymer brushes on silica particles. Langmuir 2015, 31, 4129–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.-C.; Babu, T.; Aronova, M.; Wang, S.; Lu, Z.; Chen, X.; Nie, Z. Self-assembly of amphiphilic plasmonic micelle-like nanoparticles in selective solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7974–7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Liu, Y.; Babu, T.; Wei, Z.; Nie, Z. Self-assembly of inorganic nanoparticle vesicles and tubules driven by tethered linear block copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11342–11345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Huang, X. Polymer brushes: Efficient synthesis and applications. Accounts Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2314–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.; Feng, Y.; Li, B.; Zhao, H. Coassembly of linear diblock copolymer chains and homopolymer brushes on silica particles: A combined computer simulation and experimental study. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1894–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Surface reconstruction by a coassembly approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10577–10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Yang, Y.; Nie, Z. Alternating copolymerization of inorganic nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7917–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.; Zhong, W.; Zhao, H. Asymmetric colloidal particles fabricated by polymerization-induced surface self-assembly approach. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 2617–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, P.; Pranantyo, D.; Neoh, K.; Kang, E.; Teo, S. One-step anchoring of tannic acid-scaffolded bifunctional coatings of antifouling and antimicrobial polymer brushes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 1786–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejima, H.; Richardson, J.J.; Liang, K.; Best, J.P.; van Koeverden, M.P.; Such, G.K.; Cui, J.; Caruso, F. One-step assembly of coordination complexes for versatile film and particle engineering. Science 2013, 341, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shutava, T.; Prouty, M.; Kommireddy, D.; Lvov, Y. pH responsive decomposable layer-by-layer nanofilms and capsules on the basis of tannic acid. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 2850–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Synthesis of polymer brushes and removable surface nanostructures on tannic acid coatings. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, F.; Mao, J. Preparation and properties of thermosetting powder/graphene oxide coatings for anticorrosion application. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 48264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagi, P.; Ghorpade, R.; Choi, Y.; Patil, U.; Kim, I.; Baik, J.; Hong, S. Carbon Dioxide-Based Polyols as Sustainable Feedstock of Thermoplastic Polyurethane for Corrosion-Resistant Metal Coating. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3871–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Yuan, B.; Guo, Z. Aluminum dihydric tripolyphos-phate/polypyrrole-functionalized graphene oxide waterborne epoxy composite coatings for impermeability and corrosion protection performance of metals. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2021, 4, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ju, Y.; Zhao, H. Bioassemblies fabricated by coassembly of protein molecules and monotethered single-chain polymeric nanoparticles. Langmuir 2018, 34, 13705–13712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Yuan, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Self-assembly of monotethered single-chain nanoparticle shape amphiphiles. ACS Macro Lett. 2013, 2, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Xing, B. Tannic acid adsorption and its role for stabilizing carbon nanotube suspensions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5917–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).