Abstract

Antiviral polymers are part of a major campaign led by the scientific community in recent years. Facing this most demanding of campaigns, two main approaches have been undertaken by scientists. First, the classic approach involves the development of relatively small molecules having antiviral properties to serve as drugs. The other approach involves searching for polymers with antiviral properties to be used as prescription medications or viral spread prevention measures. This second approach took two distinct directions. The first, using polymers as antiviral drug-delivery systems, taking advantage of their biodegradable properties. The second, using polymers with antiviral properties for on-contact virus elimination, which will be the focus of this review. Anti-viral polymers are obtained by either the addition of small antiviral molecules (such as metal ions) to obtain ion-containing polymers with antiviral properties or the use of polymers composed of an organic backbone and electrically charged moieties like polyanions, such as carboxylate containing polymers, or polycations such as quaternary ammonium containing polymers. Other approaches include moieties hybridized by sulphates, carboxylic acids, or amines and/or combining repeating units with a similar chemical structure to common antiviral drugs. Furthermore, elevated temperatures appear to increase the anti-viral effect of ions and other functional moieties.

1. Introduction

Viruses are not living organisms per se, but small structures containing only a nucleic acid genome within a mostly protein based protecting membrane. Unlike living organisms, viruses must penetrate a living host cells to reproduce and replicate [1].

Viruses are usually classified into seven major classes [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Class I includes viruses with double-stranded DNA, like Poxvirus, which uses asymmetric transcription to raise their mRNA, much like “regular” cells, but depend on the hosting cell’s polymerases to transcript their genome. Class II contains single-stranded DNA viruses. The DNA’s polarity in these viruses is equal to their mRNA’s. This Class contains the Anelloviridae, Circoviridae, Parvoviridae, Geminiviridae, Microviridae, and more. Class III includes viruses with double-stranded RNA. These viruses’ mRNA demonstrates an asymmetric transcription of the virus’ genome. This group includes the Reoviridae and Birnaviridae viruses. Class IV consists of viruses with single-stranded RNA. These viruses’ mRNA is the sequence’s base identical to their virion RNA. These viruses are referred to as “positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses”. This group contains Togaviridae, Astroviridae (causing diarrhea), Caliciviridae, Flaviviridae (including many different diseases such as Hepatitis-C, bovine viral diarrhea virus, and more), Picornaviridae (including the rhinoviruses, which causes the “common cold”), Arteriviridae, and Coronaviridae [including the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)]. Class V contains viruses with single-stranded RNA. These viruses’ mRNA is complementary in the base to their RNA, and thus also referred to as “negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses”. This class includes Filoviridae, Arenaviridae, Rhabdoviridae (include the rabies virus), Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, and Bunyaviridae. Class VI contains viruses that along with single-stranded RNA, use the reverse transcription of their positive RNA into a DNA molecule, and thus depend on the host’s polymerases to synthesis their required proteins and to replicate their genome. One example of these viruses is the retroviruses (like HIV). Class VII, one of the smallest classes, consists of viruses with double-stranded DNA that formed into a closed covalent loop. The major example of this group is the Hepatitis-B virus.

The antiviral mechanisms are not always established, and hence common antiviral drug mechanisms are yet to be well understood.

A common antiviral therapeutic method is the use of specific negatively or positively charged particles. Copper and silver ions were of the very first antiviral particles to be studied. In their research about ”the molecular mechanisms of copper and silver ion disinfection of bacteria and viruses”, Thurman and Gerba suggest that positively charged particles (i.e., cations) may affect the DNA/RNA of the viruses [9]. Most microorganisms, including viruses, have some negative charge over their membranes, under near-neutral pH conditions, due to prototrophic groups such as carboxyl, amino, guanidyl, and imidazole which may cause ionization. Cations, therefore, are attracted to the microorganisms’ surface where they might undergo certain reactions. Those cations may also attach to the DNA, RNA, or some enzymes while affecting their action. It should be noted, however, that not all the cations have the same effect – whether it is due to the lack of fitting channels in the membrane or because the cation itself lacks any toxic effect over the microorganism (for example, while copper and silver ions are toxic to most microorganisms, calcium ions are part of their functions and thus lack any toxic effect and might even increase viruses attachment ability [10]). Moreover, as Thurman and Gerba described, neutral particles penetrate the membrane more easily than ions. Thus, neutral complexes (salts) of toxic ions are more effective in the disinfection of bacteria and viruses than pure ions. It should be noted that, as shown by Chambers, the antiviral efficiency of all ions generally increases in proportion to the ion concentration, besides the specific mechanisms that will be described below [11].

While discussing toxic metal ions, several mechanisms have been demonstrated. Lund suggested that the effect of heavy metal ions comes from their oxidation potential, with a higher oxidation potential correlating to a faster reaction [12]. Samuni et al. suggested that due to the “Fenton mechanism”, transition metal ions bind to specific sites in biological polymers/macromolecules. During binding, those ions undergo redox reaction forming secondary radicals next to the original binding target. Then, those radicals attack the macromolecule-metal ion complex, creating H2O2 which attacks again the complex to form OH radicals. This cyclic redox reaction causes damage to the original molecule and thus leads to its inactivity [13,14]. While this mechanism matches the copper toxic effect [9] and some other metal ions redox reagents [13], three other explanations for the silver toxicity mechanism have been suggested. Tilton and Rosenberg [15] and Khandelwalet et al. [16] suggested that silver might interfere with the essential electron transportation of the microorganisms, and thus cause their elimination. Furthermore, they suggested that silver might bind to DNA/RNA and/or interact with the microorganism’s membrane which leads to functional damage. Petering proposed that while binding to proteins and some other biomaterials, silver form insoluble compounds which is the basic toxic activity of silver and silver ions [17]. Another explanation for the toxicity of both silver and copper ions is that these two metal ions are attracted to the molecules in the cells/viruses more than the cell ions such as phosphate-based ions. When such ions switch positions with the original cell ones, they cause denaturation and/or other structural damage. Moreover, when a metal ion is placed between two particles with hydrogen bonds, a replacement of the hydrogen occurs and then the pH of the surroundings increases [9,18,19]. While these are the major explanations for copper and silver antiviral and antibacterial properties, some other explanations were suggested in the literature, for both these ions and others [9,16,20,21]. Further study conducted by Hashimoto et al. showed that solid-state cuprous compounds, such as cuprous oxide (Cu2O), sulphide (Cu2S), iodide (CuI), and chloride (CuCl) have high antiviral efficiency, compared to solid-state silver and cupric compounds [22].

Zinc is another example of a metal cation that has been well studied for its in vitro antiviral effect on the viral proteins (at low concentrations) and DNA (at high concentrations) [23]. Read et al. in their review about the role of zinc in antiviral immunity, pointed out that the zinc concentrations that were needed to achieve the antiviral effect (mM [23]) are much higher than the physiological concentrations (μM), with some differences in the needed concentrations between different types of viruses [24]. For example, van Hemert and his associates demonstrated the inhibition effect of some zinc derivatives over the binding and elongation of coronaviruses’ RdRp enzymes [25]. They showed that a combination of 2–320 μM of pyrithione with 2–500 μM of Zn(AC)2 has a major effect, with increasing effect at higher concentrations, over SARS-CoV and EAV populations. Moreover, they suggested that water-soluble zinc-ionophores might have a higher antiviral effect. Hong et al. demonstrated the effect of 60–300 μM ZnCl2 on the RNA polymerase of Hepatitis C viruses [26]. Takagi et al. also demonstrated the effect of ZnCl2, but with lower concentrations of 50–150 μM on the replication of Hepatitis C viruses [27]. Further, 50–200 μM of ZnSO4 has an antiviral effect, as shown by Ahlenstiel et al. [28] and by Brendel et al. [23]. Some other Zn salts that showed antiviral effects are pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), zinc gluconate (Zn(Glu)2) [24,29], zinc lactate (Zn(Lac)2), zinc citrate (CIZAR), zinc picolinate (Zn(pic)2), and zinc aspartate (Zn(asp)2) [24] as well as zinc ionophores pyrithione [30]. Also, it seems that the antiviral effect of zinc ions is temperature-depended. While at lower temperatures (4–18 °C) zinc has no significant effect on the virus population, at elevated temperatures (20–25 °C) the antiviral effect is significantly increased [23].

While only a few studies have been conducted on the effect of iron ions, it seems that these ions have some level of antiviral effect, as described in Aagripanti et al. work [31]. Cobalt (III) is also a metal ion with antiviral effects [32].

Some other metal-based anions showed antiviral properties like nickel [20], polyoxometalates, polyatomic ions containing three transitional metals such as titanium, vanadium, tungsten, molybdenum, etc. that form clusters with the surrounding oxygen (the transition metal oxyanions linked to each other with sharing oxygen atoms). Those anions show antiviral properties by affecting the virus envelopes/membranes which lead to inhibition of virus infections and an effect on the syncytium formation [33,34].

Non-metal ions have also been studied for their antiviral properties. Pyridinium-based ions, for example, were shown to cause an almost full destruction of viral envelope/membrane, leading leakage of virus DNA/RNA [35]. Quaternary ammonium derivatives are another non-metal cations that have also shown antiviral properties, probably due to their effect on the virus envelopes permeability which is far beyond their viability [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. This mechanism leads to high efficiency against envelope containing viruses, while its effect on non-envelope viruses is debatable [45]. It should be noted that ammonium derivatives are known to have not only an antiviral effect, but also an antibacterial effect [45,46], and thus form the basis of some commercial disinfectants and cleaners. These commercial products, specifically quaternary ammonium chloride ones, have been tested and found effective against the foot-and-mouth disease virus [47]. Xanthates shows an antiviral effect on RNA and DNA viruses under acidic conditions, as was demonstrated by Sauer et al. in 1987 [48].

Besides ions, other antiviral moieties have been studied. Aurintricarboxylic acid (ATA) could easily be polymerized in water by reacting salicylic acid with formaldehyde, sulphuric acid, and sodium nitrite [49]. Reymen et al. displayed that owing to an interaction between aurintricarboxylic acid analog polymers and the virus membrane/envelope, the replication of DNA and RNA virus was inhibited [49]. Sulphate and phosphorothioate oligonucleotides have been studied for antiviral therapeutics, due to their effect on the hydrophobic properties of the virus envelops, affecting the virus penetrating ability. This effect is amplified with the amount of sulphate or phosphorothioate oligonucleotides moieties, and thus several sulphate/phosphorothioate oligonucleotides containing polymers have been studied, as will be described later [50]. Ganciclovir and Acyclovir are well known commercial antiviral drugs which, though not having any electrical charge, have a well-established effect on some virus polymerase. Some other molecules with antiviral effects are 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA), verapamil, and diltiazem. Some studies suggest their effect is a result of the ion-blocking effect. Others suggested that the viral inhibition is based on interactions with virus proteins [51]. Other neutral antiviral molecules are ascorbic and dehydroascorbic acids [52], triclosan [53] and the camphor imine derivatives. Various studies conducted in recent years showed the antiviral potential of the latter, especially against Influenza viruses [54,55,56].

4. Summary and Conclusions

The antiviral battle has been the focus of numerous studies over the years. While originally focusing on small molecules based on antiviral drugs, in recent years, researchers started concentrating on hybrid and composite polymers as a promising approach to the global viral problem. The antiviral campaign is waged in two main approaches. The first employing polymers as drug delivery systems based on biodegradable polymers conjugated with antiviral drugs. In this approach, polymers are used in a supporting role, increasing efficacy and half-life of delivered drugs. The second exploiting hybrid and composite polymers. In this approach, polymers are incorporated with metal and/or metal-ions particles like zinc, silver, copper, zirconium, magnesium, tungsten, and more or otherwise hybridized antiviral polymers based on electrically-charged moieties, are employed, whether anionic or anionic, such as carboxylate and/or organic acids/anhydride, or cationic or cationic such as ammonium, phosphonium, and amines. Some other approaches studied include sulphate containing polymers, phenol/hydroxyl-containing polymers and organometal polymers such as organotin-based polymers. Moreover, some studies have suggested the polymerization of commercial antiviral drugs to achieve a more efficient treatment.

Lastly, it was shown that some antiviral effects are temperature dependent. Most of the reported investigations pointed out that increased temperatures enhance the antiviral impact of ions and the hybrid polymers. Thus, a combination of anti-viral polymers along with the ability to increase temperature may be an additional tool to increase antiviral properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.K. and H.D.; Writing—original draft preparation: N.J. and S.K.; Writing-review & editing: N.J. and S.K.; Validation: S.K. and H.D.; Supervision: S.K. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| PAS | Poly(anethole sulphonic acid) | Cu2S | Cuprous sulfide |

| 6′SLN-PAA | Poly(N-2-hydroxyethylacrylamide) | EIPA | 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride |

| PVS | Poly(vinyl Sulphonic acid) | ATA | Aurintricarboxylic acid |

| TESET | Poly[tert-butylstyrene-b-(ethylene-alt-propylene)-b-(styrene sulphonate)-b-(ethylene-alt-propylene)-b-tert-butylstyrene] | AcMNPV | Autographa californica Multicapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| PEI | Polyethyleneimine | CuCl | Cuprous chloride |

| PHB | Polyhydroxybutyrat | CuI | Cuprous iodide |

| PHBV | Polyhydroxybutyrate valerate | Cu2O | Cuprous oxide |

| PGN | Poly-l-glutamine | DDAB | didodecyldimethylammonium bromide |

| PDTC | Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate | FCV | Feline Calicivirus |

| SNP | Silica Nanoparticle | VHSV | Hemorrhagic Septicaemia viruses |

| HIV | The human immunodeficiency virus | HSV | Herpes simplex virus |

| TiO2 | Titanium Oxide | HA | Humic acid |

| TMV | Tobacco mosaic virus | IPNV | Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis virus |

| Zn(AC)2 | Zinc Acetate | MOFs | Metal-organic frameworks |

| Zn(asp)2 | Zinc aspartate | EMCV | Murine Encephalomyocarditis virus |

| CIZAR | Zinc citrate | 6′SLN | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ |

| Zn(Glu)2 | Zinc gluconate | PLO | Poly(l-ornithine) |

| Zn(Lac)2 | Zinc lactate | PAMPS | poly(2-acry-lamido-2-methyl-l-propane sulphonic acid) |

| Zn(pic)2 | Zinc picolinate | PSS | Poly(4-styrene sulphonic acid) |

References

- Introduction to Virology | Division of Medical Virology. Available online: http://www.virology.uct.ac.za/vir/teaching/mbchb/intro (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Kayser, F.H.; Bienz, K.A.; Eckert, J.; Zinkernagel, R.M. Kaiser, Medical Microbiology; Thieme: Zurich, Switzerland, 2005; ISBN 3131319917. [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore, D. Expression of animal virus genomes. Bacteriol. Rev. 1971, 35, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.E.; Zweerink, H.J.; Joklik, W.K. Polypeptide components of virions, top component and cores of reovirus type 3. Virology 1969, 39, 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderblom, H.R. Structure and Classification of Viruses. In Medical Microbiology; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996; ISBN 0963117211. [Google Scholar]

- Van Regenmortel, M.H.V. The Species Problem in Virology. In Advances in Virus Research; Academic Press Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 100, pp. 1–18. ISBN 9780128152010. [Google Scholar]

- Kibenge, F.S.B. Classification and identification of aquatic animal viruses. In Aquaculture Virology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 9–34. ISBN 9780128017548. [Google Scholar]

- Van Regenmortel, M.H.V. Virus Species. In Genetics and Evolution of Infectious Diseases; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 3–19. ISBN 9780123848901. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman, R.B.; Gerba, C.P. The molecular mechanisms of copper and silver ion disinfection of bacteria and viruses. Crit. Rev. Environ. Control 1989, 18, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, N.E.; Anderson, D.A. Early interactions of hepatitis A virus with cultured cells: Viral elution and the effect of pH and calcium ions. Arch. Virol. 1997, 142, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.L. Effect of ionic concentration on the infectivity of a virus of the citrus red mite, Panonychus citri. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1968, 10, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E. The significance of oxidation in chemical inactivation of poliovirus. Arch. Gesamte Virusforsch. 1962, 12, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuni, A.; Aronovitch, J.; Godinger, D.; Chevion, M.; Czapski, G. On the cytotoxicity of vitamin C and metal ions: A site-specific Fenton mechanism. Eur. J. Biochem. 1983, 137, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuni, A.; Chevion, M.; Czapski, G. Roles of copper and superoxide anion radicals in the radiation- induced inactivation of T7 bacteriophage. Radiat. Res. 1984, 99, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilton, R.C.; Rosenberg, B. Reversal of the Silver Inhibition of Microorganisms by Agar. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1978, 35, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, N.; Kaur, G.; Kumar, N.; Tiwari, A. Application of silver nanoparticles in viral inhibition: A new hope for antivirals. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2014, 9, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Petering, H.G. Pharmacology and toxicology of heavy metals: Silver. Pharmacol. Ther. Part A Chemother. Toxicol. 1976, 1, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.Z.; Heng, X.; Chen, S.J. Theory meets experiment: Metal ion effects in HCV genomic RNA kissing complex formation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mönttinen, H.A.M.; Ravantti, J.J.; Poranen, M.M. Evidence for a non-catalytic ion-binding site in multiple RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzaghou, I.; Bougie, I.; Bisaillon, M. Effect of metal ion binding on the structural stability of the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 49755–49761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javidpour, L.; Lošdorfer Božič, A.; Naji, A.; Podgornik, R. Multivalent ion effects on electrostatic stability of virus-like nano-shells. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunada, K.; Minoshima, M.; Hashimoto, K. Highly efficient antiviral and antibacterial activities of solid-state cuprous compounds. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 235–236, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumel, G.; Schrader, S.; Zentgraf, H.; Daus, H.; Brendel, M. The mechanism of the antiherpetic activity of zinc sulphate. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 2989–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.A.; Obeid, S.; Ahlenstiel, C.; Ahlenstiel, G. The Role of Zinc in Antiviral Immunity. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Velthuis, A.J.W.; van den Worml, S.H.E.; Sims, A.C.; Baric, R.S.; Snijder, E.J.; van Hemert, M.J. Zn2+ inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E.; Wright-Minogue, J.; Fang, J.W.S.; Baroudy, B.M.; Lau, J.Y.N.; Hong, Z. Characterization of Soluble Hepatitis C Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, K.; Naganuma, A.; Sato, K.; Ikeda, M.; Kato, N.; Takagi, H.; Mori, M. Zinc is a negative regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Liver Int. 2006, 26, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, S.A.; Parnell, G.; Booth, D.; Douglas, M.W.; George, J.; Ahlenstiel, G. The antiviral role of zinc and metallothioneins in hepatitis C infection. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.B.; Cetnarowski, W.E. Effect of Treatment with Zinc Gluconate or Zinc Acetate on Experimental and Natural Colds. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krenn, B.M.; Gaudernak, E.; Holzer, B.; Lanke, K.; Van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Seipelt, J. Antiviral Activity of the Zinc Ionophores Pyrithione and Hinokitiol against Picornavirus Infections. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagripanti, J.L.; Routson, L.B.; Lytle, C.D. Virus inactivation by copper or iron ions alone and in the presence of peroxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 4374–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.L.; Simmers, C.; Knight, D.A. Cobalt complexes as antiviral and antibacterial agents. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 1711–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeta, S.; Mori, S.; Kodama, E.; Kodama, J.; Takahashi, K.; Yamase, T. Broad spectrum anti-RNA virus activities of titanium and vanadium substituted polyoxotungstates. Antiviral Res. 2003, 58, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, K.; Katoh, N.; Matsuoka, T.; Fujinami, K. In vitro Antimicrobial Effects of Virus Block, Which Contains Multiple Polyoxometalate Compounds, and Hygienic Effects of Virus Block-Supplemented Moist Hand Towels. Pharmacology 2019, 104, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

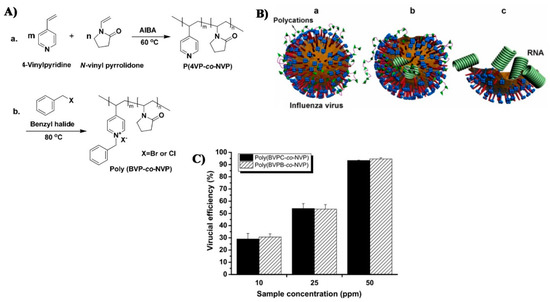

- Xue, Y.; Xiao, H. Antibacterial/antiviral property and mechanism of dual-functional quaternized pyridinium-type copolymer. Polymers (Basel) 2015, 7, 2290–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkov, S.N. The Antiviral Activity of Chitosan (Review). Prikl. Biokhimiya Mikrobiol. 2002, 38, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E.M.; Liu, O.C. Studies of Inhibitory Effect of Ammonium Ions in Several Virus-Tissue Culture Systems. Exp. Biol. Med. 1961, 107, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, R.D.; Hirschfield, J.E.; Forbes, M. A common mode of antiviral action for ammonium ions and various amines. Nature 1965, 207, 664–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Niu, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Lu, A.; Wang, X.; Qian, Z.; Huang, Z.; Jin, X.; et al. Antiviral effects of ferric ammonium citrate. Cell Discov. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuladhar, E.; de Koning, M.C.; Fundeanu, I.; Beumer, R.; Duizer, E. Different virucidal activities of hyperbranched quaternary ammonium coatings on poliovirus and influenza virus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2456–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mi, Y.; Dong, F.; Lei, C.; Guo, Z. Enhanced antioxidant and antifungal activity of chitosan derivatives bearing 6-O-imidazole-based quaternary ammonium salts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

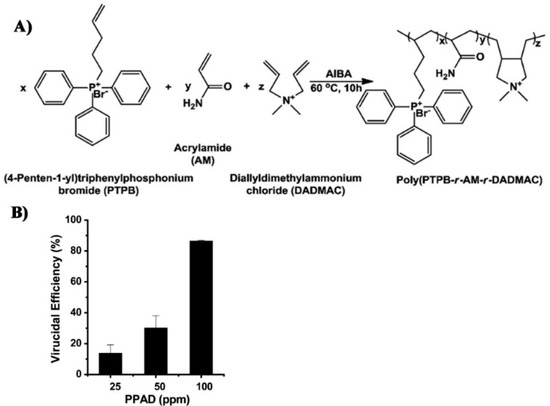

- Xue, Y.; Pan, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhao, Y. Novel quaternary phosphonium-type cationic polyacrylamide and elucidation of dual-functional antibacterial/antiviral activity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 46887–46895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaruma, L.G. Synthetic biologically active polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1975, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.S.; Ahmad, M.; Minhas, M.U.; Tulain, R.; Barkat, K.; Khalid, I.; Khalid, Q. Chitosan/Xanthan Gum Based Hydrogels as Potential Carrier for an Antiviral Drug: Fabrication, Characterization, and Safety Evaluation. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Niu, L.N.; Ma, S.; Li, J.; Tay, F.R.; Chen, J.H. Quaternary ammonium-based biomedical materials: State-of-the-art, toxicological aspects and antimicrobial resistance. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 71, 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, N.; Keul, H.; Heine, E.; Moeller, M. From multifunctionalized poly(ethylene imine)s toward antimicrobial coatings. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2874–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HARADA, Y.; LEKCHAROENSUK, P.; FURUTA, T.; TANIGUCHI, T. Inactivation of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus by Commercially Available Disinfectants and Cleaners. Biocontrol Sci. 2015, 20, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amtmann, E.; Müller-Decker, K.; Hoss, A.; Schalasta, G.; Doppler, C.; Sauer, G. Synergistic antiviral effect of xanthates and ionic detergents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1987, 36, 1545–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymen, D.; Witvrouw, M.; Esté, J.A.; Neyts, J.; Schols, D.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R.; Cushman, M.; Hejchman, E.; De Clercq, E. Mechanism of the antiviral activity of new aurintricarboxylic acid analogues. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1996, 7, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, A. Nucleic acid polymers: Broad spectrum antiviral activity, antiviral mechanisms and optimization for the treatment of hepatitis B and hepatitis D infection. Antiviral Res. 2016, 133, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazina, E.V.; Harrison, D.N.; Jefferies, M.; Tan, H.; Williams, D.; Anderson, D.A.; Petrou, S. Ion transport blockers inhibit human rhinovirus 2 release. Antiviral Res. 2005, 67, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, A.; Uozaki, M.; Yamasaki, H.; Arakawa, T.; Arita, M.; Koyama, A.H. Antiviral effects of ascorbic and dehydroascorbic acids in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 22, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PATRA, J.K.; GOUDA, S. Application of nanotechnology in textile engineering: An overview. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2013, 5, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Korchagina, D.V.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Tretiak, T.S.; Anfimov, P.M.; Kiselev, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Camphor-based symmetric diimines as inhibitors of influenza virus reproduction. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Shernyukov, A.V.; Gatilov, Y.V.; Razumova, Y.V.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Tretiak, T.S.; Pokrovsky, A.G.; Kiselev, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Discovery of a new class of antiviral compounds: Camphor imine derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 105, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarubaev, V.V.; Garshinina, A.V.; Tretiak, T.S.; Fedorova, V.A.; Shtro, A.A.; Sokolova, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Broad range of inhibiting action of novel camphor-based compound with anti-hemagglutinin activity against influenza viruses in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2015, 120, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, P.; Kaur, G. Polymeric films as a promising carrier for bioadhesive drug delivery: Development, characterization and optimization. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, I.C.; Poff, J.; Cortés, M.E.; Sinisterra, R.D.; Faris, C.B.; Hildgen, P.; Langer, R.; Shastri, V.P. A novel polymeric chlorhexidine delivery device for the treatment of periodontal disease. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3743–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallury, P.; Airrabeelli, R.; Li, J.; Paquette, D.; Kalachandra, S. Release of antimicrobial and antiviral drugs from methacrylate copolymer system: Effect of copolymer molecular weight and drug loading on drug release. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Huang, X.; Yu, R.; Jing, X.L.; Xu, J.; Wu, C.A.; Zhu, C.X.; Liu, H.M. Elevated ambient temperature differentially affects virus resistance in two tobacco species. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.; Yeom, M.; Kim, H.O.; Lim, J.W.; Na, W.; Park, G.; Park, C.; Kang, A.; Yun, D.; Kim, J.; et al. Efficient antiviral co-delivery using polymersomes by controlling the surface density of cell-targeting groups for influenza A virus treatment. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Weight, A.K.; Haldar, J.; Wang, L.; Klibanov, A.M.; Chen, J. Polymer-attached zanamivir inhibits synergistically both early and late stages of influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20385–20390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostoni, V.; Chalati, T.; Horcajada, P.; Willaime, H.; Anand, R.; Semiramoth, N.; Baati, T.; Hall, S.; Maurin, G.; Chacun, H.; et al. Towards an Improved anti-HIV Activity of NRTI via Metal-Organic Frameworks Nanoparticles. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013, 2, 1630–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, S.; Kizilel, S. Biomedical Applications of Metal Organic Frameworks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 1799–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, R.; Tort, O.; García-Pardo, J.; Escribà, T.; Lorenzo, J.; Arnedo, M.; Ruiz-Molina, D.; Alibés, R.; Busqué, F.; Novio, F. Versatile iron-catechol-based nanoscale coordination polymers with antiretroviral ligand functionalization and their use as efficient carriers in HIV/AIDS therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.A.A.; Kryger, M.B.L.; Wohl, B.M.; Ruiz-Sanchis, P.; Zuwala, K.; Tolstrup, M.; Zelikin, A.N. Macromolecular (pro)drugs in antiviral research. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 6407–6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

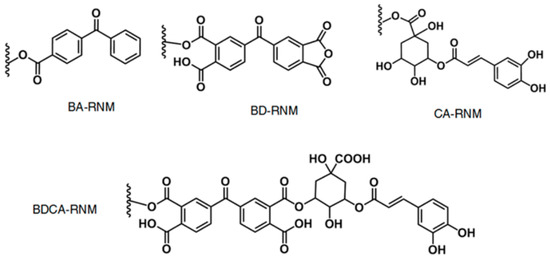

- Kryger, M.B.L.; Wohl, B.M.; Smith, A.A.A.; Zelikin, A.N. Macromolecular prodrugs of ribavirin combat side effects and toxicity with no loss of activity of the drug. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2643–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.M. Antiviral Polymeric Drugs and Surface Coatings; Massachusetts Institute Of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, A.M.; Wang, H.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, T.; Chen, J.; Klibanov, A.M. Conjugating Drug Candidates to Polymeric Chains Does Not Necessarily Enhance Anti-Influenza Activity. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 3896–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

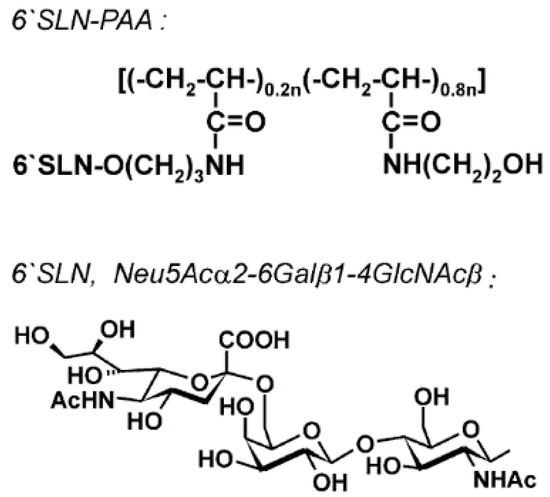

- Gambaryan, A.S.; Boravleva, E.Y.; Matrosovich, T.Y.; Matrosovich, M.N.; Klenk, H.D.; Moiseeva, E.V.; Tuzikov, A.B.; Chinarev, A.A.; Pazynina, G.V.; Bovin, N.V. Polymer-bound 6′ sialyl-N-acetyllactosamine protects mice infected by influenza virus. Antiviral Res. 2005, 68, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

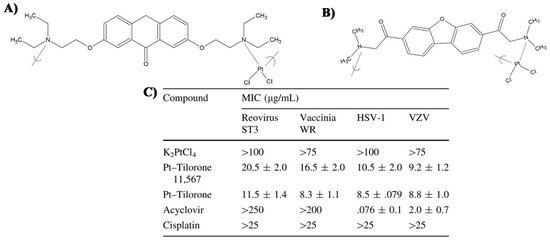

- Roner, M.R.; Carraher, C.E.; Dhanji, S.; Barot, G. Antiviral and anticancer activity of cisplatin derivatives of tilorone. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2008, 18, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roner, M.R.; Carraher, C.E. Cisplatin derivatives as antiviral agents. In Inorganic and Organometallic Macromolecules: Design and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 193–223. ISBN 9780387729466. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.M.O.; Islam, M.S.; Haque, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Hamid, M.A. Antibacterial activity of polyaniline coated silver nanoparticles synthesized from Piper betle leaves extract. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigita, S.; Tsurumi, H.; Naka, H. Anti-Viral Fiber, Process for Producing the Fiber, and Textile Product Comprising the Fiber. U.S. Patent Application No. 10/591,460, 26 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, K.; Ogawa, H.; Bui, V.N.; Inoue, H.; Fukuda, J.; Ohba, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nakamura, K. Inactivation of high and low pathogenic avian influenza virus H5 subtypes by copper ions incorporated in zeolite-textile materials. Antiviral Res. 2012, 93, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, S.; Imoto, Y.; Kosaka, T.; Nishida, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Yamamoto, T.A. Antiviral Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Immobilized onto Textile Fabrics Synthesized by Radiochemical Process. MRS Adv. 2016, 1, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elechiguerra, J.L.; Burt, J.L.; Morones, J.R.; Camacho-Bragado, A.; Gao, X.; Lara, H.H.; Yacaman, M.J. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2005, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, H.H.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C. PVP-coated silver nanoparticles block the transmission of cell-free and cell-associated HIV-1 in human cervical culture. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, H.H.; Ayala-Nuñez, N.V.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C. Mode of antiviral action of silver nanoparticles against HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Singh, A.; Vig, K.; Pillai, S.; Singh, S. Silver Nanoparticles Inhibit Replication of Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2008, 4, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J.V.; Parkinson, C.V.; Choi, Y.W.; Speshock, J.L.; Hussain, S.M. A preliminary assessment of silver nanoparticle inhibition of monkeypox virus plaque formation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speshock, J.L.; Murdock, R.C.; Braydich-Stolle, L.K.; Schrand, A.M.; Hussain, S.M. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with Tacaribe virus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Ono, T.; Miyahira, Y.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Matsui, T.; Ishihara, M. Antiviral activity of silver nanoparticle/chitosan composites against H1N1 influenza A virus. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagna, C.; Perero, S.; Percivalle, E.; Nepita, E.V.; Ferraris, M. Virucidal effect against Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 of a silver nanocluster/silica composite sputtered coating. Open Ceram. 2020, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Kizima, L.; Seidor, S.; Menon, R.; Jean-Pierre, N.; Pugach, P.; Levendosky, K.; Derby, N.; Gettie, A.; et al. A modified zinc acetate gel, a potential nonantiretroviral microbicide, is safe and effective against simian-human immunodeficiency virus and herpes simplex virus 2 infection in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4001–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

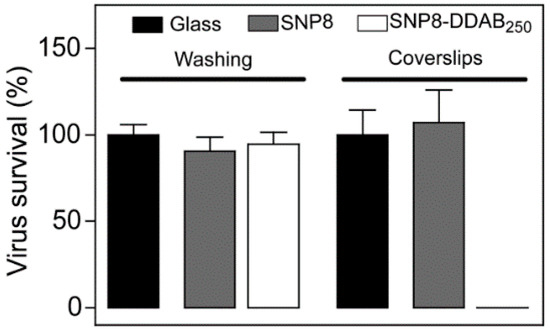

- Botequim, D.; Maia, J.; Lino, M.M.F.; Lopes, L.M.F.; Simões, P.N.; Ilharco, L.M.; Ferreira, L. Nanoparticles and surfaces presenting antifungal, antibacterial and antiviral properties. Langmuir 2012, 28, 7646–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiviral Agent, Coating Composition, Resin Composition and Antiviral Product. U.S. Patent 16/078,534, 17 February 2017.

- Parthasarathi, V.; Thilagavathi, G. Development of tri-laminate antiviral surgical gown for liquid barrier protection. J. Text. Inst. 2015, 106, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.Y.; Mohammad, A.W.; Leo, C.P.; Hilal, N. Polymeric membranes incorporated with metal/metal oxide nanoparticles: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2013, 308, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyigundogdu, Z.U.; Demir, O.; Asutay, A.B.; Sahin, F. Developing Novel Antimicrobial and Antiviral Textile Products. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 181, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, O.D.; Durán, N.E.C. Polymeric Anhydride of Magnesium and Proteic Ammonium Phospholinoleate with Antiviral, Antineoplastic and Immunostimulant Properties. U.S. Patent 5,073,630, 17 December 1991. [Google Scholar]

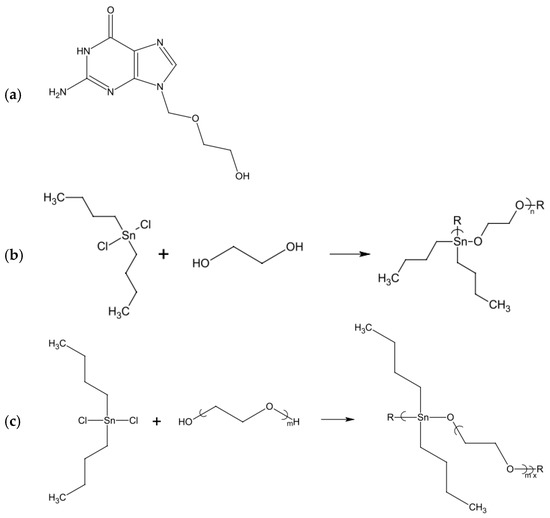

- Roner, M.R.; Carraher, C.E.; Miller, L.; Mosca, F.; Slawek, P.; Haky, J.E.; Frank, J. Organotin Polymers as Antiviral Agents Including Inhibition of Zika and Vaccinia Viruses. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roner, M.R.; Carraher, C.E.; Shahi, K.; Barot, G. Antiviral activity of metal-containing polymers-organotin and cisplatin-like polymers. Materials (Basel) 2011, 4, 991–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, L.; Tang, C. Metal-containing and related polymers for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5232–5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

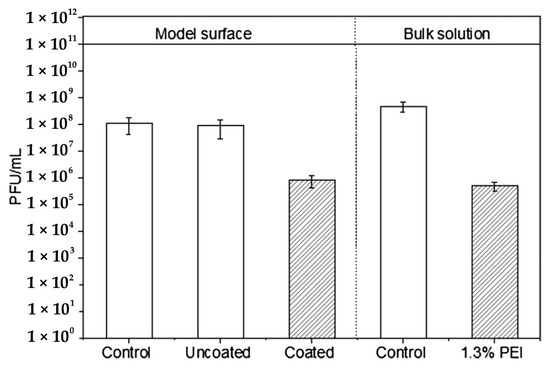

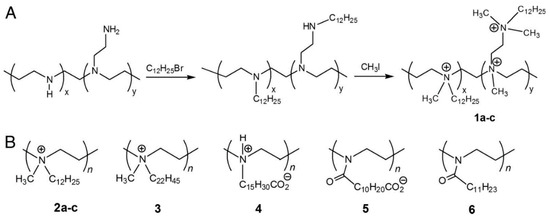

- Sinclair, T.R.; Robles, D.; Raza, B.; van den Hengel, S.; Rutjes, S.A.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; de Grooth, J.; de Vos, W.M.; Roesink, H.D.W. Virus reduction through microfiltration membranes modified with a cationic polymer for drinking water applications. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 551, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiyama, K.; Yang, C.; Chandrasekaran, L.; Liu, S.; Rong, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, S.; Lee, A.; Ohba, K.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Cooperative Orthogonal Macromolecular Assemblies with Broad Spectrum Antiviral Activity, High Selectivity, and Resistance Mitigation. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, L.; Bromberg, D.J.; Hatton, T.A.; Bandín, I.; Concheiro, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Antiviral properties of polymeric aziridine- and biguanide-modified core-shell magnetic nanoparticles. Langmuir 2012, 28, 4548–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Oh, H.S.; Knipe, D.M.; Klibanov, A.M. Decreasing herpes simplex viral infectivity in solution by surface-immobilized and suspended N,N-dodecyl,methyl-polyethylenimine. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Klibanov, A.M. Biocidal Packaging for Pharmaceuticals, Foods, and Other Perishables. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2013, 4, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Hsu, B.B.; Rautaray, D.; Haldar, J.; Chen, J.; Klibanov, A.M. Hydrophobic polycationic coatings disinfect poliovirus and rotavirus solutions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshina, J.L.; Kelly, A.; Oldham, T.; Rogers, R.D. Agricultural uses of chitin polymers. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, H.; Wang, F.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X.; Lei, C. Antioxidant, antifungal and antiviral activities of chitosan from the larvae of housefly, Musca domestica L. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Dong, Y.; Xu, C.; Xie, Q.; Xie, Y.; Xia, Z.; An, M.; Wu, Y. Novel combined biological antiviral agents Cytosinpeptidemycin and Chitosan oligosaccharide induced host resistance and changed movement protein subcellular localization of tobacco mosaic virus. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 164, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donalisio, M.; Ranucci, E.; Cagno, V.; Civra, A.; Manfredi, A.; Cavalli, R.; Ferruti, P.; Lembo, D. Agmatine-containing poly(amidoamine)s as a novel class of antiviral macromolecules: Structural properties and in vitro evaluation of infectivity inhibition. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 6315–6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Xue, Y.; Snow, J.; Xiao, H. Tailor-made antimicrobial/antiviral star polymer via ATRP of cyclodextrin and guanidine-based macromonomer. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2015, 216, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha-Blob, L.; Vengris, V.E.; Pitha, P.M.; Pitha, J. Uptake and Fate of Water-Soluble, Nondegradable Polymers with Antiviral Activity in Cells and Animals. J. Med. Chem. 1977, 20, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

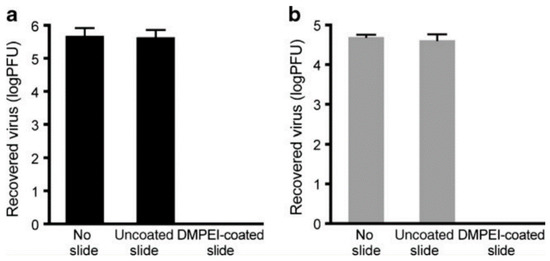

- Haldar, J.; An, D.; De Cienfuegos, L.Á.; Chen, J.; Klibanov, A.M. Polymeric coatings that inactivate both influenza virus and pathogenic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 17667–17671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

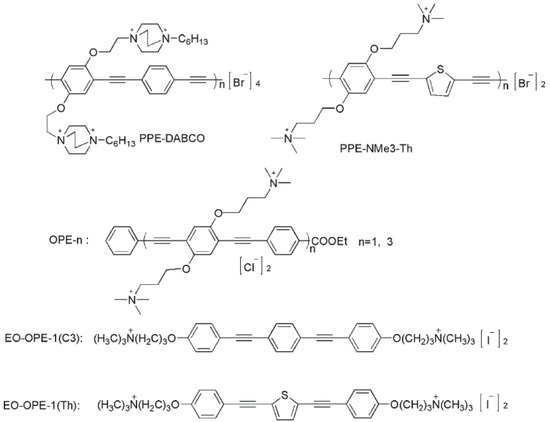

- Wang, Y.; Canady, T.D.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, Y.; Price, D.N.; Bear, D.G.; Chi, E.Y.; Schanze, K.S.; Whitten, D.G. Cationic phenylene ethynylene polymers and oligomers exhibit efficient antiviral activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 2209–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

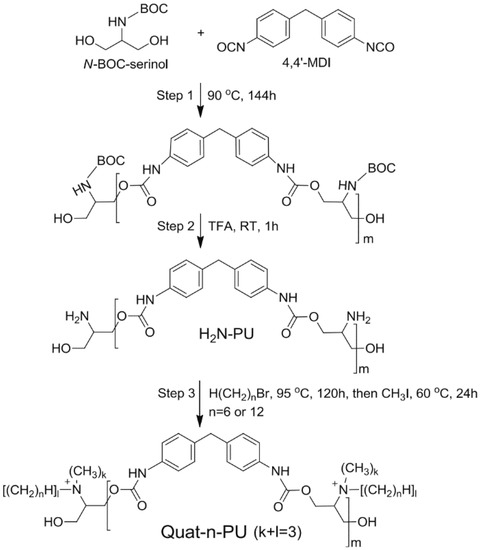

- Park, D.; Larson, A.M.; Klibanov, A.M.; Wang, Y. Antiviral and antibacterial polyurethanes of various modalities. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 1134–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulve, N.; Kimmerling, K.; Johnston, A.D.; Krueger, G.R.; Ablashi, D.V.; Prusty, B.K. Anti-herpesviral effects of a novel broad range anti-microbial quaternary ammonium silane, K21. Antiviral Res. 2016, 131, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Kakehi, H.; Shuto, Y. Antibacterial/Antiviral Coating Agent. U.S. Patent 10,550,274, 4 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Macchione, M.A.; Guerrero-Beltrán, C.; Rosso, A.P.; Euti, E.M.; Martinelli, M.; Strumia, M.C.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.Á. Poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) Nanogels with Antiviral Behavior against HIV-1 Infection. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, J. Antimicrobial and Antiviral Polymeric Materials. U.S. Patent No. 7,169,402 B2, 30 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.; Imanishi, N.; Kashiwayama, Y.; Kawano, A.; Terasawa, K.; Shimada, Y.; Ochiai, H. Inhibitory effect of cinnamaldehyde, derived from Cinnamomi cortex, on the growth of influenza A/PR/8 virus in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2007, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randazzo, W.; Fabra, M.J.; Falcó, I.; López-Rubio, A.; Sánchez, G. Polymers and Biopolymers with Antiviral Activity: Potential Applications for Improving Food Safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigan, T.C.; Finkelstein, M.S. Interferon-stimulating and in vivo antiviral effects of various synthetic anionic polymers. Virology 1968, 35, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Loebenstein, G. Induced Interference by Synthetic Polyanions with the Infection of Tobacco Mosaic Virus. Phytopathology 1972, 62, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

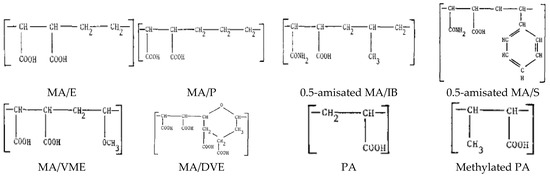

- Feltz, E.T.; Regelson, W. Ethylene maleic anhydride copolymers as viral inhibitors. Nature 1962, 196, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, M.; Otsuki, K.; Takakuwa, H.; Tsunekuni, R. Antiviral Substance, Antiviral Fiber, and Antiviral Fiber Structur. U.S. Patent Application 12/679,211, 28 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone, V.; Passic, S.; Wigdahl, B.; Rando, R.F.; Labib, M.; Krebs, F.C. A styrene- alt -maleic acid copolymer is an effective inhibitor of R5 and X4 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Suflet, D.M.; Pelin, I.M.; Chiţanu, G.C. Biomedical applications of maleic anhydride copolymers. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2011, 56, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Arnáiz, E.; Vacas-Cõrdoba, E.; Galán, M.; Pion, M.; Gõmez, R.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.Á.; De La Mata, F.J. Synthesis of anionic carbosilane dendrimers via “click chemistry” and their antiviral properties against HIV. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neenan, T.X.; W. Harry Mandeville, I. Antiviral Polymers Comprising Acid Functional Groups and Hydrophobic Groups. U.S. Patent 6,268,126, 31 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Helbig, B.; Klöcking, R.; Wutzler, P. Anti-herpes simplex virus type 1 activity of humic acid-like polymers and their o-diphenolic starting compounds. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1997, 8, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y. Antiviral activity of alginate against infection by tobacco mosaic virus. Carbohydr. Polym. 1999, 38, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate: Properties and biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

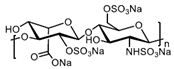

- Schols, D.; Clercq, E.D.; Balzarini, J.; Baba, M.; Witvrouw, M.; Hosoya, M.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R.; Neyts, J.; Pauwels, R.; et al. Sulphated Polymers are Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Various Enveloped Viruses, Including Herpes Simplex Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Vesicular Stomatitis Virus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and Toga-, Arena-, and Retroviruses. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1990, 1, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Srisomporn, P.; Hayashi, K.; Tanaka, T.; Sankawa, U.; Hayashi, T. Effects of structural modification of calcium spirulan, a sulfated polysaccharide from Spirulina Platensis, on antiviral activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, H.R., Jr.; Tankersley, R.W., Jr. Antiviral Sulfonated Naphthalene Formaldehyde Condensation Polymers. U.S. Patent 4,604,404, 5 August 1986. [Google Scholar]

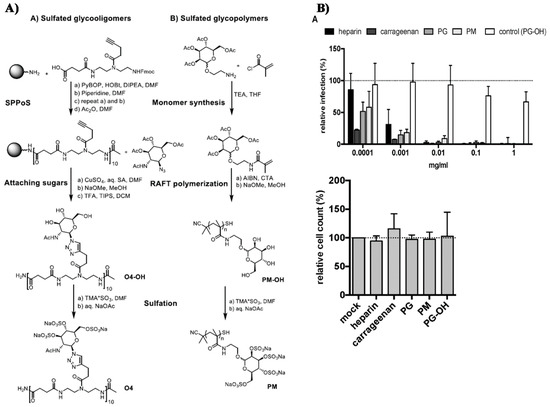

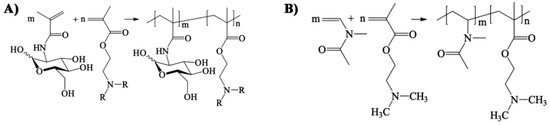

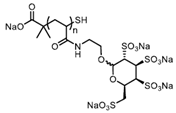

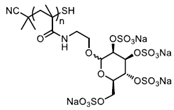

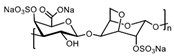

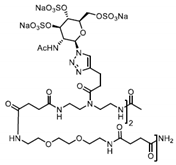

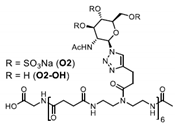

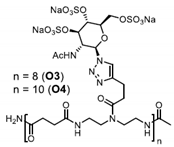

- Soria-Martinez, L.; Bauer, S.; Giesler, M.; Schelhaas, S.; Materlik, J.; Janus, K.A.; Pierzyna, P.; Becker, M.; Snyder, N.L.; Hartmann, L.; et al. Prophylactic antiviral activity of sulfated glycomimetic oligomers and polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peddinti, B.S.T.; Scholle, F.; Vargas, M.G.; Smith, S.D.; Ghiladi, R.A.; Spontak, R.J. Inherently self-sterilizing charged multiblock polymers that kill drug-resistant microbes in minutes. Mater. Horizons 2019, 6, 2056–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, I.; Takayama, K.; Honma, K.; Gonda, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Hatanaka, K.; Uryu, T.; Yoshida, O.; Nakashima, H.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Synthesis, structure and antiviral activity of sulfates of curdlan and its branched derivatives. Br. Polym. J. 1990, 23, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, A.R.; Strick, N.; Li, Y.Y. Anti-HIV-1 activity of anionic polymers: A comparative study of candidate microbicides. BMC Infect. Dis. 2002, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusconi, S.; Moonis, M.; Merrill, D.P.; Pallai, P.V.; Neidhardt, E.A.; Singh, S.K.; Willis, K.J.; Osburne, M.S.; Profy, A.T.; Jenson, J.C.; et al. Naphthalene sulfonate polymers with CD4-blocking and anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.L.; Li, Y.; Ni, L.Q.; Li, Y.X.; Cui, Y.S.; Jiang, S.L.; Xie, E.Y.; Du, J.; Deng, F.; Dong, C.X. Structural characterization and antiviral activity of two fucoidans from the brown algae Sargassum henslowianum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y. Antiviral activity of polysaccharides against infection of tobacco mosaic virus. Macromol. Symp. 1995, 99, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y. Antiviral activity of chondroitin sulfate against infection by tobacco mosaic virus. Carbohydr. Polym. 1997, 33, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiyue, S.; Ying, L.; Kanamoto, T.; Asai, D.; Takemura, H. Elucidation of anti-HIV mechanism of sulfated cellobiose – polylysine dendrimers. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, P.; Schols, D.; Baba, M.; De Clercq, E. Sulfonic acid polymers as a new class of human immunodeficiency virus inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 1992, 18, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Came, P.E.; Lieberman, M.; Pascale, A.; Shimonas, G. Antiviral Activity of an Interferon-Inducing Synthetic Polymer. Exp. Biol. Med. 1969, 131, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.L.; Brennan, T.M.; Bridges, C.G.; Mullins, M.J.; Tyms, A.S.; Jackson, R.; Cardin, A.D. Potent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus by MDL 101028, a novel sulphonic acid polymer. Antiviral Res. 1995, 28, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, D.J.; Nordali, S.F.; Walter, D.C. Antimicrobial And Biological Active Polymer Composites And Related Methods, Materials and Devices. U.S. Patent 15/509,834, 26 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MARCHETTI, M.; PISANI, S.; PIETROPAOLO, V.; SEGANTI, L.; NICOLETTI, R.; ORSI, N. Inhibition of Herpes Simplex Virus Infection by Negatively Charged and Neutral Carbohydrate Polymers. J. Chemother. 1995, 7, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, S. Tempesta Proanthocyanidin polymers having antiviral activity and methods of obtaining same. U.S. Patent 5,211,944, 18 May 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wyde, P.R.; Ambrose, M.W.; Meyerson, L.R.; Gilbert, B.E. The antiviral activity of SP-303, a natural polyphenolic polymer, against respiratory syncytial and parainfluenza type 3 viruses in cotton rats. Antiviral Res. 1993, 20, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catel-Ferreira, M.; Tnani, H.; Hellio, C.; Cosette, P.; Lebrun, L. Antiviral effects of polyphenols: Development of bio-based cleaning wipes and filters. J. Virol. Methods 2015, 212, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarova, O.V.; Anan’eva, E.P.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Sinegubova, E.O.; Zolotova, Y.I.; Bezrukova, M.A.; Panarin, E.F. Synthesis and Antibacterial and Antiviral Properties of Silver Nanocomposites Based on Water-Soluble 2-Dialkylaminoethyl Methacrylate Copolymers. Pharm. Chem. J. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.; Fu, Q.; Huang, K.; Nitin, N.; Ding, B.; Sun, G. Daylight-driven rechargeable antibacterial and antiviral nanofibrous membranes for bioprotective applications. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

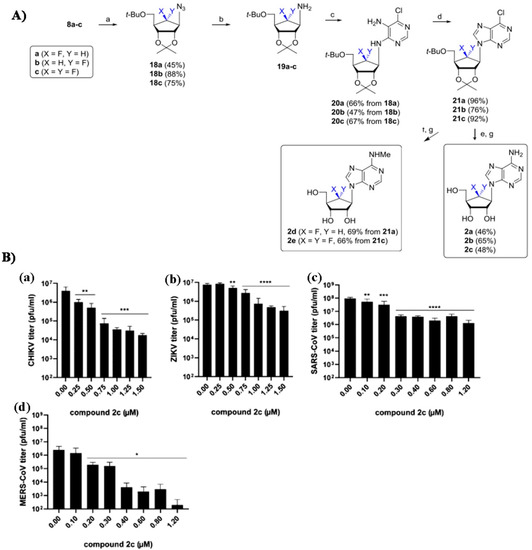

- Yoon, J.S.; Kim, G.; Jarhad, D.B.; Kim, H.R.; Shin, Y.S.; Qu, S.; Sahu, P.K.; Kim, H.O.; Lee, H.W.; Wang, S.B.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Anti-RNA Virus Activity of 6′-Fluorinated-Aristeromycin Analogues. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 6346–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

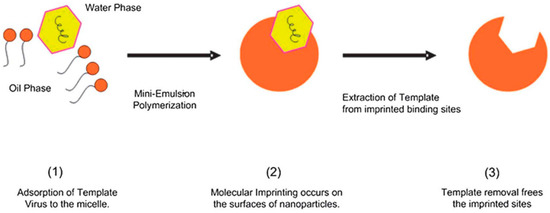

- Sankarakumar, N.; Tong, Y.W. Preventing viral infections with polymeric virus catchers: A novel nanotechnological approach to anti-viral therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 2031–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpstra, F.G.; Rechtman, D.J.; Lee, M.L.; Van Hoeij, K.; Berg, H.; Van Engelenberg, F.A.C.; Van’t Wout, A.B. Antimicrobial and antiviral effect of high-temperature short-time (HTST) pasteurization apllied to human milk. Breastfeed. Med. 2007, 2, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholtissek, C.; Rott, R. Effect of temperature on the multiplication of an Influenza virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1969, 5, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.C.; Spendlove, R.S.; Goede, R.W. Effect of temperature on survival and growth of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus. Infect. Immun. 1975, 11, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Paul, A.V.; Wimmer, E. Effects of temperature and lipophilic agents on poliovirus formation and RNA synthesis in a cell-free system. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 5932–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaya, M.; Nishimura, H.; Lusamba Kalonji, N.; Deng, X.; Momma, H.; Shimotai, Y.; Nagatomi, R. Effects of high temperature on pandemic and seasonal human influenza viral replication and infection-induced damage in primary human tracheal epithelial cell cultures. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, D.K. Effects of temperature on virus-host relationships and on activity of the noninclusion virus of citrus red mites, Panonychus citri. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1974, 24, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.H.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Lam, S.Y.; Poon, L.L.M.; Yuen, K.Y.; Seto, W.H. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HARRISON, B.D. Studies on the Effect of Temperature on Virus Multiplication in Inoculated Leaves. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1956, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzadeh, F. Literature Review of The Effect of Salinity on the Larger Marine Algae. Ashrae 2014, 117, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Randazzo, W.; Fabra, M.J.; Lagaron, J.M.; Aznar, R.; Sánchez, G. Antiviral properties of silver nanoparticles against norovirus surrogates and their efficacy in coated polyhydroxyalkanoates systems. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cababie, L.A.; Incicco, J.J.; González-Lebrero, R.M.; Roman, E.A.; Gebhard, L.G.; Gamarnik, A.V.; Kaufman, S.B. Thermodynamic study of the effect of ions on the interaction between dengue virus NS3 helicase and single stranded RNA. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenbroich, D.; Özel, M.; Vater, J.; Kamp, R.M.; Pauli, G. Mechanism of inactivation of enveloped viruses by the biosurfactant surfactin from Bacillus subtilis. Biologicals 1997, 25, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, S.K.; Danthi, P.; Chow, M.; Hogle, J.M. Stabilization of poliovirus by capsid-binding antiviral drugs is due to entropic effects. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 296, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Galabov, A.S.; Mileva, M. Abstract Tannins as Antiviral Agents. In Tannins—Structural Properties, Biological Properties and Current Knowledge; Aires, A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).