Abstract

Reinforced concrete flat slabs or flat plates continue to be among the most popular floor systems due to speed of construction and inherent flexibility it offers in relation to locations of partitions. However, flat slab/plate floor systems that are deficient in two-way shear strength are susceptible to brittle failure at a slab–column junction that may propagate and lead to progressive collapse of a larger segment of the structural system. Deficiency in two-way shear strength may be due to design/construction errors, material under-strength, or overload. Fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) composite laminates in the form of sheets and/or strips are used in structurally deficient flat slab systems to enhance the two-way shear capacity, flexural strength, stiffness, and ductility. Glass FRP (GFRP) has been used successfully but carbon FRP (CFRP) sheets/strips/laminates are more commonly used as a practical alternative to other expensive and/or challenging methods such column enlargement. This article reviews the literature on the methodology and effectiveness of utilizing FRP sheets/strips and laminates at the column/slab intersection to enhance punching shear strength of flat slabs.

1. Introduction

Reinforced concrete slabs that are not supported by beams, also known as flat slabs are the most popular floor system in the building construction industry due to architectural flexibility and speed of construction. Speed of constructing flat slab systems is owed primarily to savings in time that would have been needed to build formwork for supporting beams. They also offer designers the flexibility of placing heavy and light partitions anywhere on the floor slab without abiding by location of beams. However, flat slabs are susceptible to brittle two-way shear failure (i.e., punching shear failure) at the slab–column connection that is caused by the transfer of shear and unbalanced moments [1]. Although the mechanics of punching shear is not completely understood, many methods have been developed over the years to prevent this type of failure. Four basic stages in the punching failure of a slab–column connection are generally recognized. Firstly, flexural and shear cracks form in the tension zone of the slab near the face of the loaded area. Secondly, the slab tension steel close to the loaded area yields. Thirdly, flexural and shear cracks extend into what was the compression zone of the concrete. Finally, failure occurs before yielding of reinforcing steel extends beyond the vicinity of the loaded area. A possible reason for punching failure is the rupture of the reduced compression zone in the slab [2]. The failed surface forms a conical shape enclosed by an inclined critical crack pattern which meets a horizontal crack parallel to the reinforcing steel reaching the tension side [3]. When a slab–column connection is loaded, the initial response is linear-elastic, followed by cracking which reduces the connection stiffness. The deflected profile in the slab compression region can be considered as straight lines, while that in the tension region shows a slight discontinuity, especially when the shear crack intersects the reinforcement. Moe [4] tested 43 slabs and investigated the results of 140 footings in addition to 120 slabs that are reported in the literature and noted the common appearance of inclined cracks at 60% of the ultimate load. These inclined cracks started from bending cracks, then rapidly extended up to the proximity of the neutral axis and finally developed rather slowly but leaving only a very narrow depth of the compression zone unaffected. During the structural design phase, if the shear capacity is exceeded, shear reinforcement can be designed to enhance the capacity. Some studies indicated that using shear reinforcement in two-way slabs may double the punching shear strength [5].

Strengthening flat slabs at the column–slab juncture using externally applied material with high tensile strength did not start with the fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) sheets. Steel plates with steel anchor bolts were used successfully to increase the two-way shear strength of flat slabs. Ebead and Marzouk [6] strengthened slab–column junctions by installing on the tension side 6 mm thick American society for testing and materials (ASTM) A6 plates using 19 mm diameter ASTM A325 bolts. Steel plates increased the ultimate load of the flat slab by 45% when the applied load was central and by 122% when the specimens were subjected to both central loads and moments. The light weight, flexibility, and high tensile strength of FRP sheets and laminates make them viable alternative to steel plates. Externally bonded carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) sheets that are anchored to concrete at their ends were shown to increase punching shear strength, especially when applied skewed relative to the column orientation [7]. Flexural capacity of concrete flat slab can also be increased by bonding CFRP sheets, strips, or laminates to the tension side [8,9].

Steel reinforcing bars are generally used to carry flexural tensile stresses on tension side of reinforced concrete members. Studies by Rasha et al. [9] concluded that the flexural tensile reinforcement above the column in flat slab contributes to the punching capacity of the slab. Yield strength of flexural reinforcement is amongst the factors determining the necessary amount of tension steel. Nonetheless, Dilger et al. [10] noted that no conclusive evidence exists to indicate any effect of yield strength on punching shear capacity.

Experimental studies by Ebead and Marzouk [6] on centrally loaded 1.9 m × 1.9 m × 0.25 m flat slab specimens found that the ultimate load-carrying capacity in punching shear increased compared to reference unreinforced flat slab sample by 54% when the flexural reinforcement ratio over the column was 1%. Similarly, the ultimate load for punching shear increased by 36.5% compared to the unreinforced specimen when the flexural tensile capacity was 0.5%. When the area surrounding the column, where a central load is applied, was strengthened by steel plates using bolts, the stiffness of the strengthened flat slab specimens increased by 105% compared to the un-strengthened specimens. In addition, studies by Caldentey et al. [11] showed a reduction in punching shear strength when flexural reinforcement does not pass through the slab–column intersection, compared to similar flat slabs with flexural reinforcement passing through the intersection.

McHarg et al. [12] studied the effect of flexural top reinforcement distribution on punching shear capacity. The investigators noted a 14% increase in punching shear capacity when a portion of the top flexural steel is banded over the column compared to uniform distribution of reinforcing steel.

Perhaps one of the earliest studies that suggested punching shear strength in flat slabs is proportional to the cubic root of the compressive strength was presented in the 1956 in article by Elstner and Hognestad [13]. Inácio et al. [14] found that the punching shear capacity increases by 43% when high-strength concrete is used compared to normal-strength concrete, and failure is more brittle when compared to normal strength capacity.

Tests by Alexander and Simmonds [15] showed that increasing concrete cover thickness of top flexural reinforcement at interior slab–column connections increases two-way shear capacity by a small margin compared to smaller cover. However, larger cover makes behavior less stiff compared to a slab with smaller concrete covers which suffered larger bond deformation.

One of the early studies on the effect of column aspect ratio was conducted by Hawkins et al. [16]. The study concluded that the punching shear strength decreases markedly as the column aspect ratio increases beyond 2.0.

2. Punching Shear Strength in Selected Codes and Standards

Before examining the effect of FRP sheets and strips on two-way shear strength of concrete, it is useful to evaluate the inherent two-way strength of concrete as described in building codes and design standards. International codes and standards vary in their models for estimating punching shear capacity. In the following Table 1 the models of punching shear capacity of concrete in American Concrete Institute code ACI 318 [17] and Euro code 2 (EC 2) [18] are briefly compared and discussed.

Table 1.

Comparison of two-way shear capacity in American Concrete Institute code ACI 318 and Eurocode 2 (EC 2).

As indicated in Table 1, ACI 318 requires integrity longitudinal reinforcing steel to provide residual capacity in the event of loss or damage of vertical load-carrying member. A study by Weng et al. [20] showed that integrity reinforcement plays a significant role in post-punching behavior of flat slabs and recommends a minimum of 0.63% integrity reinforcement ratio to be provided. A typical concern in relation to punching shear failure in flat plates is that its brittle nature may lead to progressive collapse of large segment of the structural system. Mohamed et al. [21] discussed effect of two-way shear on triggering progressive collapse, along with recommended design/detailing measures to enhance the post-failure behavior of the structural system.

Additionally, Table 2 demonstrates the punching shear capacity of concrete slabs as described by American Concrete Institute code ACI 318 [17], the Canadian code CSA-S806-12 [22], the British standard BS-8110 [23], the European code Eurocode 2 [18] (including shear reinforcement), and Japanese standard JSCE [24].

Table 2.

International code equations for design punching shear.

3. Experimental Specimens, FRP Strengthening Patterns, and Methods

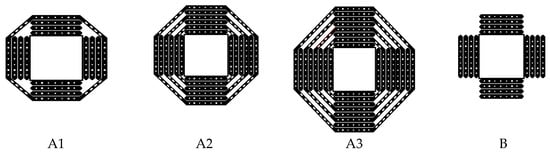

The following section includes discussion on details of experimental program, various FRP strengthening patterns and methods and some significant research findings. Binici and Bayrak [25] used 25-mm wide vertical CFRP strips for strengthening the flat slab specimens (2133 mm × 2133 mm × 152 mm) against punching shear. Strengthening of flat slab is achieved by punching 18-mm diameter vertical holes around the loading area. A practical downside to the method is the potential of cutting tension and/or integrity steel around the column which could contribute to failure. Two specimens had four holes in a line extending from each side of the loading area, one specimen had six holes on each side of the loading area, and one specimen had eight holes extending from each side of the loading area. The holes started at distance equals to ¼ of the effective depth (d/4) from the face of the loaded area and spaced at half of the effective depth (d/2) center-to-center. The authors clearly observed that that the use of diagonal CFRP strips between the holes containing the vertical strips as seen in Figure 1A1–A3 around the loading area is effective in preventing punching shear inside the shear-strengthened area compared to pattern B, with orthogonal strips. Extending CFRP shear-strengthening further along with diagonal strips to join vertical strips (A3) increases load-carrying capacity 1.51 times and the ductility 2.0 times the unstrengthening control specimens. In addition, extending the shear strengthening further from the loading area (A2 and A3), for the specimens with diagonal CFRP strips was effective in changing the failure mode from brittle punching to a more ductile failure mode.

Figure 1.

Carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) pattern A with diagonal strips provide higher two-way shear capacity compared to pattern B with orthogonal strips [25].

Applying CFRP vertically in the form of shear reinforcement is superior to bonding CFRP strips/laminate on the tension side in terms of enhancing punching shear strength. Sissakis and Sheikh [26] reported 80% increases in punching shear capacity by applying CFRP strips vertically through holes created at constant spacing perpendicular to the loading column in a manner similar to stitching of the slab.

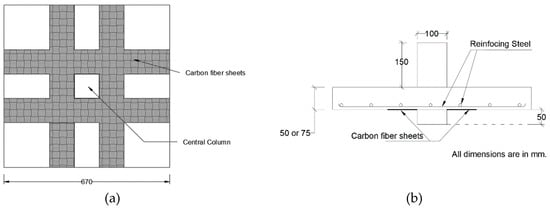

Harajli and Soudki [27] demonstrated that providing reinforcing CFRP strips on the tension face of the slab increased the punching shear strength ranged from 17% to 45% compared to the control flat slab specimens that did not contain CFRP strips for strengthening purpose as seen in Figure 2. The mechanism by which this method of strengthening increases two-way shear strength is by restricting the growth of tension cracks or by increasing flexural strength at the connection. Therefore, strengthening the slab on the tension slide in the column zone may change flexural failure mode to flexure-shear failure or pure two-way shear failure. The authors tested 670 mm square specimens with tension steel reinforcement ranging from 1% to 2%. The loading column is 100 mm × 100 mm which was cast monolithic with the slab. Four CFRP strip widths (50, 100, 150, and 200 mm) were used. Using strips on the tension side only did not affect the punching shear cracking extent and remained at a distance 2.0 × h (h = overall slab depth) from the face of the loading column.

Figure 2.

Test specimens for orthogonal CFRP strengthening strips, (a) CFRP strip pattern applied to tension side and (b) loading column and slab specimen dimensions [27].

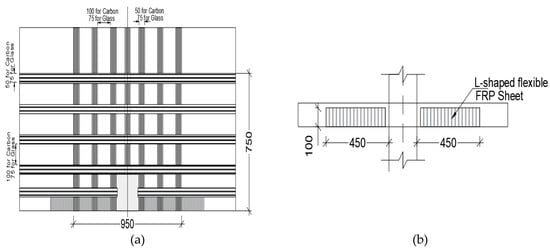

El-Salakawy et al. [28] concluded that applying CFRP or glass FRP (GFRP) strips on the tension surface of flat slab around edge columns increases the flexural stiffness and delays opening of flexural cracks, and hence increases punching shear capacity. Depending on the area of FRP sheets and configuration, the increase of edge column punching shear strength ranges from 2% to 23% compared to unstrengthen specimens. The authors examined effectiveness of strengthening edge columns in flat slab systems. Specimens were 1540 mm × 1020 mm × 120 mm thick and the supporting edge column was 250 mm × 250 mm. The slabs were reinforced with an average of 0.75% tension steel in each direction and an average of 0.45% compression steel in each direction. L-shaped strips were used perpendicular to the free edge while straight strips were applied on the tension side parallel the main reinforcement in each direction. FRP strip width was 50 mm when CFRP was used for strengthening while 75 width strips were used when GFRP was used for strengthening as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Orthogonal CFRP or glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) strengthening strips for flat slab specimen supported by the edge column: (a) extend of strip application and (b) extension of strip into L-shape at the end of the slab [28].

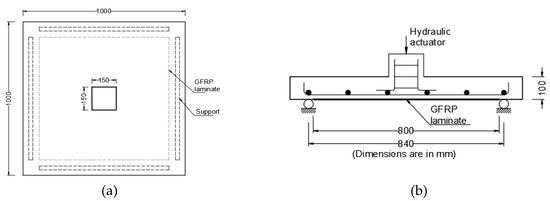

A study by Chen and Li [29] confirms that GFRP strengthening sheet increases the punching shear capacity by acting as an external flexural reinforcement. The percentage increase in punching shear capacity is higher in lower grade concrete (16.9 MPa) than in concrete of normal strength (34.4 MPa). However, GFRP sheets change the failure mode from flexure-punching failure to brittle punching failure. This study included 1000 mm × 1000 mm × 150 mm specimens loaded centrally with 150 mm square column stub to simulate interior columns in flat slabs. The flexural tension steel reinforcement ratio was 0.59% in one direction and 1.31% in the perpendicular direction. The GFRP laminate in the form of fabric is applied as one layer (1.31 mm thick) or two layers (1.93 mm thick). Using one layer of GFRP laminate increased the ultimate load from 17% to 45% while using two layers increased the ultimate, depending on the concrete grade and reinforcement ratio. For identical conditions, using two layers of laminates always increased the ultimate load.

While the failure mode in punching shear created by the GFRP sheets is consistent with published literature reviewed in this paper, the investigators covered the area under the loading column with GFRP fabric, which is not typical for building structures, except for columns supporting the roof. For this study, the authors concluded that the two-way shear prediction formulas proposed by BS 8110 and JSCE produce consistent results with their experimental study while ACI 318 was found to be more conservative. The GFRP strengthening pattern used in the study is shown in Figure 4. Liberati et al. [30] attributed the conservatism in ACI318 prediction of punching shear capacity to the fact that ACI318 does not explicitly consider the positive contribution of flexural reinforcement.

Figure 4.

GFRP laminate applied to tension side of 1000 mm × 1000 mm specimen, (a) specimen and loading column dimension and (b) loading applied causing tension at the bottom with GFRP [29].

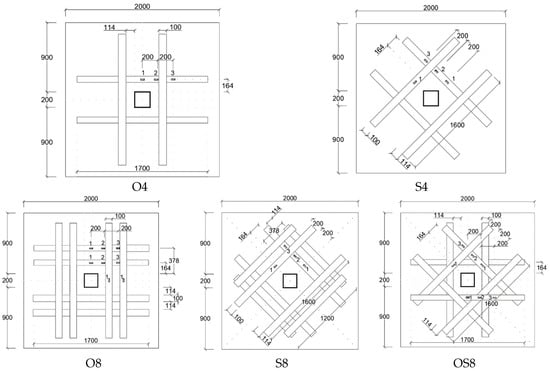

Sharaf et al. [31] observed that strengthening flat slabs in the tension zone around column using externally bonded CFRP strips increases stiffness from 29% to 60% compared the reference unreinforced flat slab depending on amount of reinforcement. Similarly tension-side stiffening around the column increases punching shear strength from 6% to 16% depending on the area and pattern of the strengthening strips. CFRP strips, in general, delayed the initiation of flexural cracks and controlled their propagation. Tested slabs demonstrated failure in punching shear predominantly. Researchers also studied the effect of orthogonal application of CFRP strips (patterns O4 and O8), skewed application of strips (patterns S4 and S8) and combination of skewed and orthogonal strips (OS8) as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

CFRP strips applied to tension side orthogonal to column orientation (O4 and O8), skewed with respect to column orientation (S4 and S8), or both orthogonal and skewed (OS8) [31].

All strips had the same width of 100 mm, therefore the effect of CFRP strip area was studied by testing specimens reinforced with either four strips (O4 and S4) or eight strips (O8, S8, and OS8). Specimens with skewed pattern and higher CFRP strip area (S8 and OS8) carried the highest ultimate load compared to orthogonal strips.

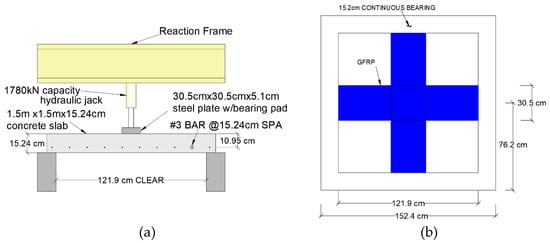

Esfahani [32] compared effectiveness of CFRP strengthening applied on the tension side of flat slab when loading is monotonic versus cyclic. It was observed that CFRP strengthening of flat slabs on the tension side increases the punching shear strength under monotonic loading, but cyclic loading decreases the effectiveness of CFRP strips in resisting punching shear. The effectiveness of strips in enhancing punching shear strength under cyclic load was more pronounced with higher tension steel reinforcement ratio. He tested two sets of 1000 mm × 1000 mm × 100 mm slabs with tension steel reinforcement ratio of 0.84 and 1.59, respectively, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

CFRP strengthening sheet applied to tension side of flat slab specimen [32].

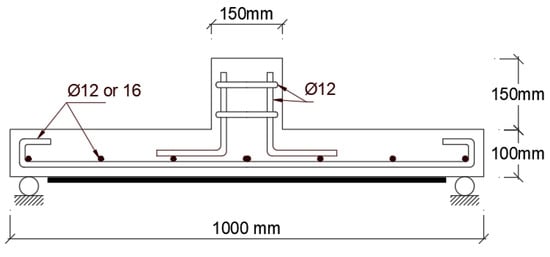

Farghaly and Ueda [33] noted that applying 0.167 mm thick CFRP strips to the tension side of flat slab around the loading column increases punching shear strength by 20%–40% compared to the unstrengthen flat slab depending on the area of the CFRP strips. Brittle punching shear failure was the dominant mode for the CFRP strengthened flat slabs. They studied 1600 mm × 1600 mm × 120 mm slab specimens with load applied through 100 mm × 100 mm. One set of slabs was strengthened with CFRP strips that are 50 mm wide (SF5) while a second set of slabs was strengthened with 100 mm wide (SF10) CFRP strips as shown in Figure 7. Steel reinforcement ratio was 1.4% designed to generate punching shear failure mode.

Figure 7.

CFRP strips with different widths applied to the tension side of the slab, (a) two-way specimen cross section, (b) top and bottom reinforcement and two CFRP strip widths tested [33].

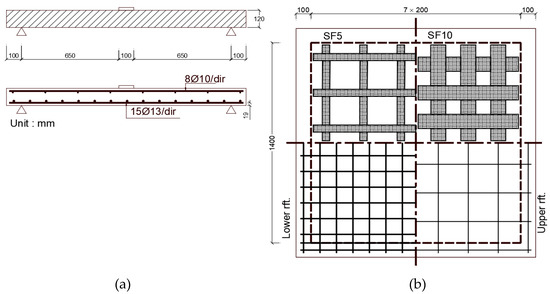

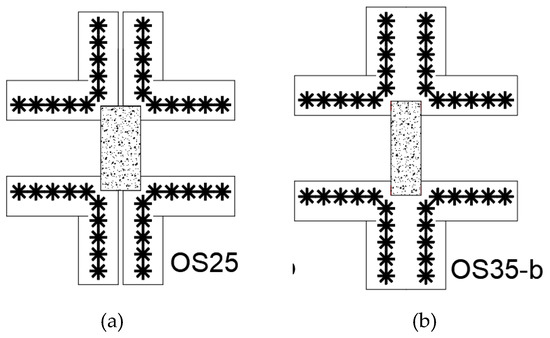

Erdogan [34] observed that vertical CFRP strips arranged in pairs perpendicular to each of the four sides of the column provide better resistance to punching shear compared to the arrangement of the vertical CFRP strips in a circular pattern around the column. In the case of perpendicular reinforcement arrangement, the failed surface was outside of the strengthened zone, while circular arrangement led to failure inside the strengthened zone. Furthermore, CFRP strengthening is more effective when the column is square than when the column is rectangular where a reduction in punching shear capacity was noticed. The investigator studied the effect of CFRP vertical strips (referred to as dowels) arranged around the interior column on punching shear strength as shown in Figure 8. The strips are applied vertically in pairs, perpendicular to each column dimension and through the depth of the slab. The pairs are spaced at d/2 (where d is the effective depth of tension steel) to ensure 45 degree cracks are intercepted. Vertical strips are intended to enhance resistance to punching shear by intercepting inclined punching shear cracks. The vertical CFRP strips were installed after concrete casting into vertical 14 mm diameter cylindrical openings. The openings were created by embedding 14 mm × 150 mm polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes prior to casting. Pipes were removed after casting.

Figure 8.

(a) Orthogonal “O” pattern of CFRP vertical shear reinforcement and (b) Circular “C” pattern of CFRP vertical reinforcement [34].

Erdogan [34] also studied the effect of column aspect ratio, as shown in Figure 9 on punching shear capacity. For columns having the same perimeter, changing the aspect ratio from 1 to 3 does not have significant effect on post-punching capacity. However, increasing the column aspect ratio decreases punching shear capacity. This behavior is recognized in ACI318 through the column aspect ratio .

Figure 9.

CFRP vertical reinforcement orthogonal to column orientation five rows with (a) column aspect ratio of 2.0 (OS25) and (b) a column aspect ratio of 3.0 [34].

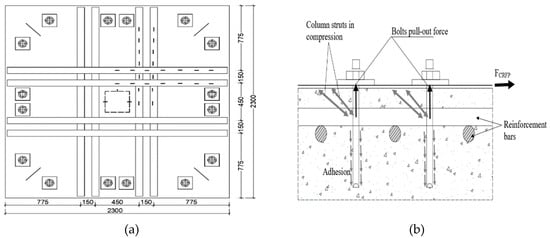

Urban and Tarka [35] observed an increase of 11% to 36% in punching shear capacity of flat slabs strengthened with CFRP strips around internal support columns. The percentage increase in punching shear capacity depends on the area of CFRP strips and whether or not anchor bolts were used to enhance bonding of the strips to the slab. The investigators studied 2300 mm × 2300 mm × 180 mm flat slab loaded with square 250 mm columns simulating internal flat slab–column intersection as shown in Figure 10a. The tensile steel reinforcement ratio for all specimens was 0.5%. Other than the control specimen, flat slabs were reinforced with 1.4 mm × 90 mm CFRP strips with varying areas (in terms of number of strips) applied around the loading column as shown in Figure 10. In addition to the adhesive, some samples were provided with additional 10 mm diameter anchoring bolts embedded 100 mm deep into the concrete slab in order to enhance bonding of the CFRP strips to concrete. Specimens strengthened using CFRP strips failed in a brittle explosive manner compared to the control specimen that was not strengthened. However, specimens in which CFRP strips were fixed to the slab using anchor bolts failed more gently than identical specimens without anchor bolts. The authors believe this “softer” failure is due to gradual pulling out of the anchor bolts from concrete as illustrated in Figure 10b.

Figure 10.

(a) Specimens with 8 strips bonded to the tension side with M10 anchor bolts and (b) anchor bolt failure mechanisms [35].

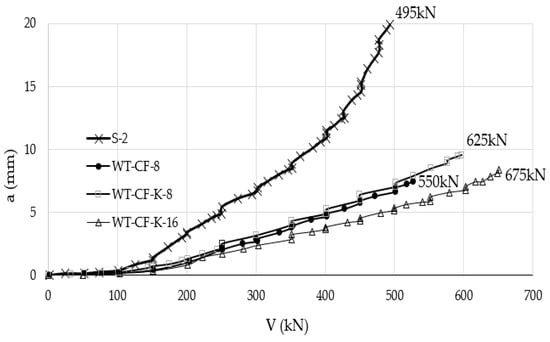

When a smaller area of CFRP strips is applied to the tension side, the effect of using anchor bolts was negligible to crack width development under applied load. However, when a larger area of CFRP strips is used to strengthen the slab, anchor bolts decreased the crack width under the applied load compared to control specimen and identical specimen with CFRP strips without anchor bolts. CFRP strips increase slab stiffness, therefore, deflection of slab strengthened with CFRP strips was much lower than the control unstrengthen flat slab. In addition for the same CFRP area using anchor bolts may or may not decrease slab deflection, depending on the area of the CFRP strips. For a larger CFRP strip area, anchor bolts decreased deflection more significantly, especially for larger applied loads than control slab or CFRP slab without anchor bolts. Thus, anchor bolts have limited or no effect on deflection of slab strengthened with CFRP strips. However, as shown in Figure 11, CFRP strengthened specimens (WT-CF-8, WT-CF-K-8, and WT-CF-K-16) and were all much stiffer than the control (unstrengthend) specimen (s-2), as indicated by the smaller deflections for the same force.

Figure 11.

Load–deflection relationship for the control specimen (s), specimen with 8 CFRP strips specimen (WT-CF-8), specimen with 8-CFRP strips and anchor bolts (WT-CF-K-8), specimen with 8-CFRPs in double layers with anchor bolts [35].

The study by Halabi et al. [36] concluded that CFRP strengthening increases the ultimate failure load in one-way spanning flat slabs when the tension-side is strengthened with CFRP strip in the column zone. The investigators concluded that eccentric loading at flat slab–column connection strengthened with CFRP sheet decreases the ductility and ultimate load. Flat slabs designed for flexural failure in negative moment area above supporting column under concentric load, will transform into shear failure occurring at a lower applied load when the failure load is eccentric. The failure load decreases with eccentricity when the slab is strengthened with CFRP or remains un-strengthened.

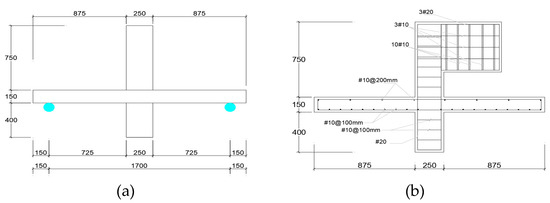

The researchers studied a total of six 2000 mm × 1000 mm × 150 mm flat slab specimens shown in Figure 12a,b supported to span in one-way to simulate internal and external slab–beam connections. The loading was applied concentrically in some specimens and eccentrically in others through 250 mm square column stubs extending above and below the flat slab specimens as shown in Figure 13a,b. The tensile steel reinforcement ratio was 0.92% in longitudinal as well as transverse directions; on compression side of the flat slab specimens the steel reinforcement ratio was 0.5%. The reinforcement was chosen for flexural failure by steel yielding prior to concrete crushing.

Figure 12.

(a) Configuration A with four 300 mm wide CFRP sheets and (b) configuration B with CFRP sheet covering entire width of slab in one direction [36].

Figure 13.

(a) Test specimen for applying concentric gravity load and (b) test specimen for applying concentric and eccentric loading [36].

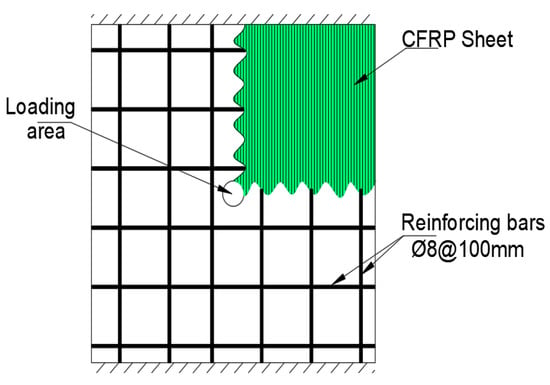

Abbas et al. [37] studied 600 mm × 600 mm × 90 mm flat slabs supported along two parallel sides to span in one-way. The steel reinforcement ratio on the tension face was 0.71%. The CFRP sheet were unidirectional applied to the slab on the tension side parallel to the direction of the span as shown in Figure 14. The loading was applied through a 40-mm diameter steel pipe.

Figure 14.

One-way supporting concrete specimen strengthened with CFRP sheet covering the entire specimen except the circular loading area [37].

It was observed that CFRP strengthening of one-way spanning flat slab increases the load-carrying capacity by 12.4% (for 39.9 MPa concrete) and 16.4% (for 63.2 MPa concrete) compared to un-strengthened control slab. However, in this study the investigators noted the presence of two peaks in the load-deflection curve. The first peak is associated with the punching failure of concrete as it loses shear capacity followed by a drop in the curve during which resistance is due to aggregate interlocked and reinforcing steel dowel action as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Load–displacement variation for punching of slabs for concrete grade B (SB: control slab; CFRP strengthened slab; and SB-T: TRM strengthened slab) [37].

After cracking the CFRP sheets are engaged in resisting the load leading to second peak in load-carrying capacity. In comparison to the control slab which would have experience significant drop in load-carrying capacity, the second peak of CFRP offers the slab much higher load-carrying capacity 189.6% (for 39.9 MPa concrete) and 275.5% (for 63.2 MPa concrete).

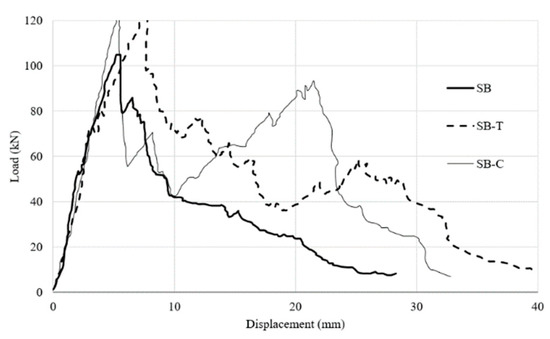

Radik et al. [38] studied seven 1500 mm × 1500 mm × 152.4 mm flat slabs to evaluate the effect of strengthening on the tension side using 305 mm wide strips applied to the tension side of the slab in two perpendicular directions. Schematic of test apparatus and pattern of GFRP strips bonded to the tension face are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

(a) Test apparatus with loading from top of the slab producing tension at the bottom, (b) 30.4 cm wide GFRP strips bonded to the tension face [38].

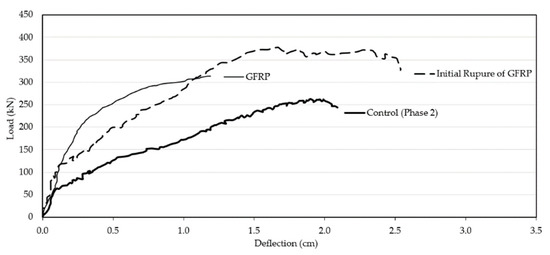

GFRP laminates bonded to the tension side increased both the ultimate load and ductility of the flat slab compared to the control specimen as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Load versus deflection plots for rehabilitated specimens [38].

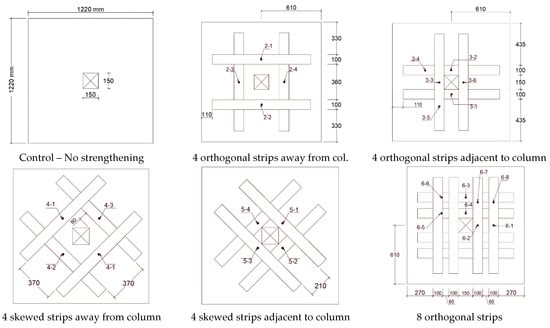

Experimental study by Soudki et al. [39] concluded that applied CFRP strips on the tension side around internal columns of flat slab increases the punching shear strength by up to 29% compared to control un-strengthened slab. CFRP strengthened slabs are stiffer, hence, experience less deflections compared to the control slab. Applying strengthening strips near the column increased stiffness of the slab while applying the same strips offset from the column increased punching shear capacity. The most efficient configuration is skewed strips offset further from the column. This investigation was performed on 1220 mm × 1220 mm × 100 mm flat slab specimens made of 25.8 MPa concrete. The effect of CFRP was studied by reinforcing selected specimens using 100 mm wide × 1.2 mm thick strips applied on the tension side around the loading column in various configurations. The orientations and configurations of the CFRP strips studied includes orthogonal to column, skewed, offset from column, or adjacent to columns is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Effect of CFRP strip area, orientation with respect to column, and distance from face of column [39].

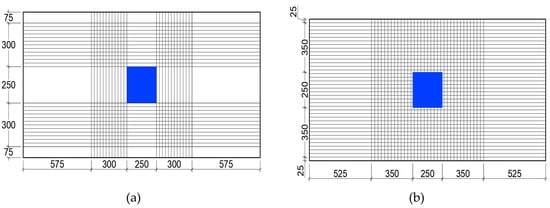

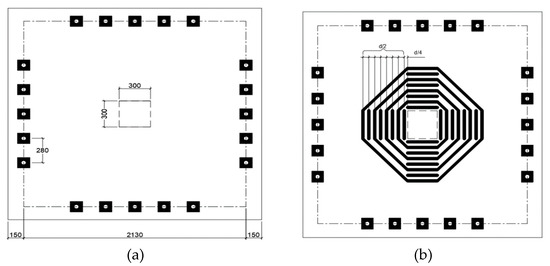

Erdogan et al. [40] examined a flat slab CFRP strengthening technique and concluded that it is capable of restoring the strength of flat slab specimen damaged through punching shear through interior column. It was also noted that rehabilitation of damaged flat slab using CFRP can restore strength to level higher than CFRP strengthened flat slab. They studied five 2130 mm × 2130 mm × 150 mm flat slabs loaded with 300 mm square plate representing internal column to flat slab connection. The goal of the study was to evaluate effectiveness of CFRP strengthening and repair of pre-loaded slabs that failed due to punching shear. The investigators indicated the dimensions chosen to represent 2/3 scale models of 8-m span flat slab that is 225-mm thick supported by 450-mm square columns. The flat slab specimens were reinforced with 19-mm bars at 140-mm spacing in each direction, without compression steel, which gives a tension reinforcement ratio of 1.86%. Specimen and column dimensions, loading points and eight CFRP rows around loading column are shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

(a) Specimen dimensions, column dimensions, and locations of perimeter loading points and (b) 8 CFRP rows around loading column [40].

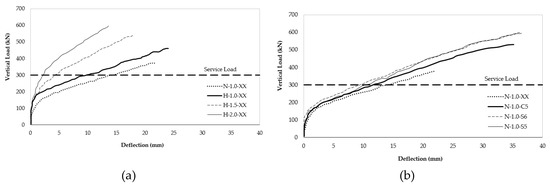

Hussein and El-Salakawy [41] concluded that increasing the flexural tension GFRP reinforcement ratio of high-strength flat slab (80 MPa) from 1% to 1.5% (50% increase) increases the punching shear strength by 15%, while increasing the reinforcement ratio to 2% (100% increases) increases the punching shear strength by 27%. The longitudinal GFRP tension reinforcement was No. 16 (15.9 mm) having a tensile strength of 1685 MPa.

GFRP shear reinforcement curbed down widening of cracks and controlled its propagation. Control of cracking lead to enhancement of the stiffness and decrease of deflection in normal strength (40 MPa) slab. No. 13 (12.7 mm diameter) GFRP shear studs increased punching shear strength by 51% compared to the control slab without shear reinforcement. No. 10 (9.5 mm) corrugated GFRP shear reinforcement increased punching shear strength by 34% compared to the control slab.

High-strength (80 MPa) flat slabs with tension GFRP reinforcement from 0.5% to 1.5%, but without shear reinforcement, failed in punching shear in a brittle manner. Cracking begins at column corners then propagates radially from the column in all directions. When the load reached 45–50% of the ultimate load circumferential cracks appeared and connected radial cracks together in all directions. The normal-strength flat slab (40 MPa) failed in the same manner when there is no shear reinforcement. However, the normal-strength flat slab exhibited higher cracking at failure compared to the high-strength flat slab. It was noted that increasing the tension reinforcement ratio decreased the punching failure cone radius by making the inclination angel of the failure crack steeper.

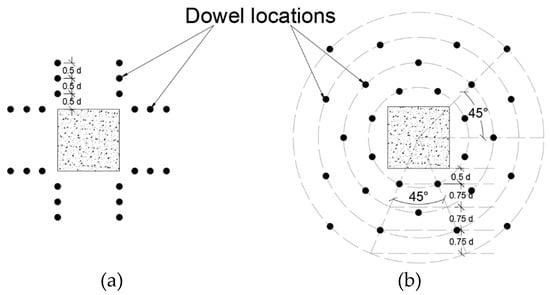

The study was performed on six 2800 mm × 2800 mm × 200 mm flat slab specimens loaded by 300 mm square column. The specimens represent interior column–flat slab connection reinforced with flexural steel on the tension-side. One test series of three specimen was used to evaluate the effect of tension steel reinforcement ratio on punching shear capacity of high-strength concrete, and a second set of three specimens was used to examine the effect of GFRP shear reinforcement type on punching shear capacity of normal-strength concrete. The flat slab specimens (three in total) set made of high-strength concrete were reinforced with 1%, 1.5%, and 2% flexural steel. The normal-strength flat slab set tested for the effect of GFRP shear reinforcement consisted of one control specimen without shear reinforcement, a second specimen reinforced with GFRP shear studs, and a third specimen reinforcement with corrugated GFRP shear reinforcement as seen in Figure 20. The study by Ferreira et al. [42] demonstrated that in the presence of studs, punching shear failure is initiated by loss of anchorage at the base of stud.

Figure 20.

(a) Load–deflection relationship for the high-strength (80 to 87 MPa) concrete, (b) load–deflection relationship for normal-strength (43 MPa) concrete [41].

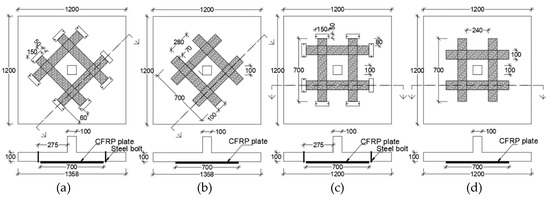

Silva et al. [43] studied eight 1200 mm × 1200 mm × 100 mm flat slab specimens with loading through 100 mm square stub simulating internal column of flat slab. CFRP strengthening strips were 700 mm long × 100 mm wide × 1 mm thick. All strengthening strips, whether orthogonal (O) or skewed (S) were placed starting one effective depth (75 mm) from the face of the column as shown in Figure 21. End anchorage of CFRP strips, when applied, was done through 50 mm × 150 mm transverse steel plates attached to the slab through 10 mm diameter steel bolts. It was observed that the skewed arrangement of CFRP strips can increase punching shear strength flat slabs by nearly 46% compared to the control slabs. Using end anchorage at the end of the strips is particularly effective in enhancing the load-carrying capacity. The critical perimeter in control slabs is located 1.5- to 2.5-times the effective depth from the column face.

Figure 21.

(a) Skewed CFRP strips with end anchorage, (b) skewed CFRP strips without end anchorage, (c) orthogonal CFRP strips with end anchorage, and (d) orthogonal CFRP strips without end anchorage [43].

Failure in the control slab occurred by formation of radial cracks at distances from 1.5 to 2.5 × d (where d = effective depth) from the face of the column. The study reported that CFRP strengthened slab failed in flexure. All strengthened specimens without end anchorage failed by de-bonding and strips failed in rupture due to their high tensile strength.

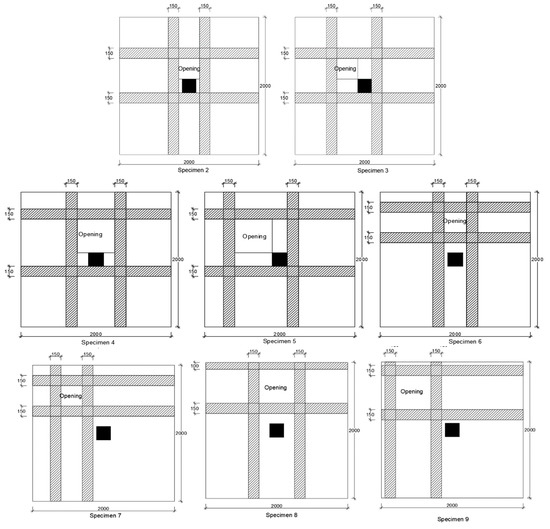

The study by Durucan and Anil [44] examined nine 2000 mm × 2000 mm × 120 mm flat slab specimens with concrete compressive strength of 20 MPa on average. The control flat slab did not have an opening while the remaining eight specimens contained openings at different locations with respect to the supporting columns, and strengthening with CFRP strips. The study included two (300 mm and 500 mm) square opening sized as shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22.

CFRP strips strengthening openings at various locations close-to or further-from the support [44].

It was demonstrated that CFRP strips were able to restore punching shear capacity of flat slabs affected by the presence of openings near the supporting columns, to nearly the same capacity of the control slabs without openings. Similarly, numerical studies by Mohamed et al. [45] observed that CFRP strengthening around openings located further from the supporting column enhances flexural capacity and overall stiffness of the slab. In fact, Lapi et al. [46] believes that the increase in punching shear strength through strengthening of the flat slab using FRP strips is the indirect effect of the increase in slab stiffness due to the strengthening strips.

A similar reduction in punching shear strength exists in voided flat slabs, where voids are incorporated in the slab to reduce self-weight [47], with applications in seismic areas. In such cases solutions for enhancing punching shear capacity may include use of a steel sheet in the critical area near the supporting column.

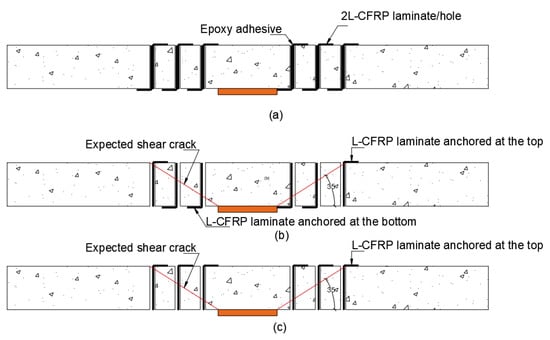

Saleh et al. [48] carried out an experimental study on four 2300 mm × 2300 mm × 200 mm flat slabs loaded concentrically through 300 mm square plates. The control flat slab was prepared with 25 MPa concrete and was not reinforced in shear. Three specimens were reinforced in shear using L-shaped CFRP laminates installed through pre-drilled 25-mm holes as shown in Figure 23. The CFRP strips were fixed through the holes with part of it (to form L-shaped) to the top or bottom using epoxy resin. The L-shaped CFRP shear reinforcing strips were applied to the unloaded slab in three perimeters around the loading plate. Perimeter one is located at a distance d/2 (where d is the effective depth) from the loading plate. Perimeters 2 and 3 are located at distances 0.7d from the loading plate.

Figure 23.

(a) Two L-shaped laminates per hole, (b) one L-shaped laminate per hole anchored at top or bottom alternately, and (c) one L-shaped laminate per hole anchored at the top [48].

It was concluded that L-shaped CFRP strips are capable of increasing the ultimate load of flat slab specimens by 97–104% higher than the control flat slab without CFRP strips. Moreover, L-shaped strips increased the deflection at failure to 400% of the control specimen.

4. Results of Experimental Studies and Major Findings

Many investigations have been conducted on strengthening the flat slab using both CFRP and GFRP. All have examined methods to delay or prevent punching shear failure. Table 3 shows summary of existing experimental work of FRP strengthening.

Table 3.

Experimental results and numerical simulation of load-carrying capacity of reference reinforced concrete flat slab.

It is important to note that experimental studies are generally conducted on a scaled-down prototype specimens due to traditional laboratory limitations. Studies by Goh and Hrynyk [49] indicate that flat slab continuity and lateral restraint greatly affect the two-way shear capacity. Studies on multi-bay slabs showed improved two-way shear capacity compared to isolated column-zone specimens.

5. Conclusions

This article reviewed the literature published in the past two decades on the effect of strengthening flat slabs/plates using fiber reinforced polymer sheets/strips in the supporting column region to enhance two-way/punching shear capacity. While CFRP and GFRP are both used for strengthening, CFRP is the dominant material, therefore, covered extensively in the literature and in this study. Models for predicting punching shear capacity in selected international codes and standards were reviewed to develop an understanding of inherent capacity and factors influencing punching shear strength. Experimental studies by various investigators were presented and discussed.

1. Several building codes and standards such as the Canadian (CSA) and Euro code 2 (EC2) recognize the contributing of flexural reinforcement in enhancing the two-way shear capacity of flat slab systems. Punching shear capacity models in ACI 318 do not incorporate the influence of flexural reinforcing steel.

2. The two most commonly used techniques to strengthen the area near a supporting column using CFRP sheets/strips include: (1) bonding (gluing) CFRP sheets/strips on the tension side of the slab around the column, (2) installing the CFRP vertically in various ways that that mimic shear reinforcement. One-way to use vertical strips is to insert them vertically leaving part of strips extended outside of the slab to be bonded horizontally for anchorage purposes.

3. Bonding CFRP sheets/trips/laminates on the tension side around supporting columns of flat slabs increases the punching shear capacity of concrete as well as the ultimate load. The effectiveness and extent of capacity improvement depends on various factors such as orientation of strips with respect to support columns, end anchorage, area of strips/sheets, etc.

4. Increase in punching shear capacity by bonding CFRP sheets/strips to the tension side of test specimens at the support location is best when the strengthening sheets/strips are anchored at the ends. Steel anchor bolts installed vertically through the slab at the ends of the strips were used successfully to increase punching shear capacity as much as 46% compared control specimen without CFRP strengthening when the load is applied concentrically. Similar improvements in punching shear capacity was observed when end anchorage is done using CFRP strips applied at the end and perpendicular to the main strengthening strips. Improvement in punching shear capacity when CFRP is bonded to tension side is lower when the load is eccentric.

5. Installing CFRP strips vertically, resembling shear reinforcement perpendicular to the slab at selected spacing from column face is more effective in enhancing punching shear capacity compared to bonding CFRP strips/sheets to the tension side of the slab.

6. Need for Future Research

The literature review revealed that additional research is needed to address critical issues and fill gaps in the current state-of-knowledge in relation to FRP strengthened slabs. The following are amongst the pressing research needs:

1. Studies have shown that vertically placed FRP sheets/laminae/strips are more effective in resisting two-way shear force. It is necessary to investigate further methods of installation that induce minimal disturbance of the flat slab that is being retrofitted.

2. Further research is needed to develop models and clear design guidelines for vertically placed FRP retrofitting strips that takes into account pattern, spacing, FRP material properties, concrete properties, etc.

3. Most studies in the past focused on flat slab specimen sizes that are feasible within typical laboratories studies. However, the limited studies that considered larger mutli-span flat slab specimens indicated possible size effects on results. There is a need to investigate larger size specimens to predict the response of FRP retrofitted slabs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A.M.; methodology, O.A.M. and R.K.; investigation, M.K.; resources, R.K; writing—original draft preparation, O.A.M. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, O.A.M. and M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, R.K.; project administration, O.A.M. and R.K.; funding acquisition, O.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs (ORSP) at Abu Dhabi University through grant No. 19300376.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zaghlal, M.Y.A. Punch Resistance of Slab Column Connection under Lateral Loads. Master’s Thesis, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S.; Simmonds, S. Shear-moment transfer in slab–column connections. In Structural Engineering Report; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1989; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Guandalini, S.; Burdet, O.L.; Muttoni, A. Punching tests of slabs with low reinforcement ratios. ACI Struct. J. 2009, 106, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, J. Shearing Strength of Reinforced Concrete Slabs and Footings under Concentrated Loads; Portland Cement Association: Skokie, IL, USA, 1961; Volume D47, p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, R.B.; Regan, P.E. Punching resistance of RC flat slabs with shear reinforcement. ACI Struct. J. 1999, 125, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebead, U.; Marzouk, H. Strengthening of two-way slabs subjected to moment and cyclic loading. ACI Struct. J. 2002, 99, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.A.L.; Madushanka, W.I.; Ariyasena, P.S.I.; Gamage, J.C.P.H. Punching Shear Capacity Enhancement of Flat Slabs Using End Anchored Externally Bonded CFRP Strips; Society of Structural Engineers: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2018; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Malalanayake, M.L.V.P.; Gamage, J.C.P.H.; Silva, M.A.L. Experimental investigation on enhancing punching shear capacity of flat slabs using CFRP. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction Management (ICSECM2017), Kandy, Sri Lanka, 7–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rasha, T.S.M.; Amr, B.; Hany, A. Effect of flexural and shear reinforcement on the punching behavior of reinforced concrete flat slabs. Alex. Eng. J. 2017, 56, 591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Dilger, W.; Birkle, G.; Mitchell, D. Effect of flexural reinforcement on punching shear resistance. Spec. Publ. 2005, 232, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Caldentey, A.P.; Lavaselli, P.P.; Peiretti, H.C.; Fernández, F.A. Influence of stirrup detailing on punching shear strength of flat slabs. Eng. Struct. 2013, 49, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHarg, P.J.; Cook, W.D.; Mitchell, D.; Yoon, Y.S. Benefits of concentrated slab reinforcement and steel fibres on performance of slab–column connections. ACI Struct. J. 2000, 97, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Elstner, R.C.; Hognestad, E. Shearing strength of reinforced concrete slabs. Int. Assoc. Bridges Struct. Eng. 1956, 53, 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Inácio, M.; Ramos, A.; Lúcio, V.; Faria, D. Punching of High-Strength Concrete Flat Slabs-Experimental Investigation. In Proceedings of the Fib Symposium Tel Aviv 2013, Tel Aviv, Israel, 22–24 April 2013; Volume 293, p. 500. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S.D.; Simmonds, S.H. Tests of column-flat plate connections. ACI Struct. J. 1992, 89, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, N.M.; Fallsen, H.B.; Hinojosa, R.C. Influence of Column Rectangularity on the Behavior of Flat Plate Structures. Spec. Publ. 1971, 30, 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- ACI Committee 318. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary: ACI 318-14; American Concrete Institute: Detroit, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. EN 1992-1-1Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings; The European Union per Regulation 305/2011; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ACI Committee 440. Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Concrete Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars: ACI 440.1R-15; American Concrete Institute: Detroit, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y.; Qian, K.; Fu, F.; Fang, Q. Numerical investigation on load redistribution capacity of flat slab substructures to resist progressive collapse. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.; Khattab, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Isam, F. Recommendations for reducing progressive collapse potential in flat slab structural systems. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 052069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Standards Association. Design and Construction of Building Structures with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer 2012; CAN/CSA S806-12; Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- British Standards Institution. Structural Use of Concrete—Code of Practice for Design and Construction; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Society of Civil Engineering. Recommendation for Design and Construction of Concrete Structures Using Continuous Fiber Reinforcing Materials; Concrete Engineering Series 23; Japan Society of Civil Engineering: Tokyo, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Binici, B.; Bayrak, O. Punching shear strengthening of reinforced concrete flat plates using carbon fiber reinforced polymers. J. Struct. Eng. ASCE 2003, 229, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissakis, K.; Sheikh, S.A. Strengthening concrete slabs for punching shear with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer laminates. ACI Struct. J. 2007, 104, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Harajli, M.H.; Soudki, K.A. Shear strengthening of interior slab–column connections using carbon fiber-reinforced polymer sheets. J. Compos. Constr. 2003, 7, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Salakawy, E.; Soudki, K.A.; Polak, M.A. Punching shear behavior of flat slabs strengthened with fiber reinforced polymer laminates. J. Compos. Constr. 2004, 8, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Li, C.Y. Punching shear strength of reinforced concrete slabs strengthened with glass fiber-reinforced polymer laminates. ACI Struct. J. 2005, 202, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, E.A.P.; Marques, M.G.; Leonel, E.D.; Almeida, L.C.; Trautwein, L.M. Failure analysis of punching in reinforced concrete flat slabs with openings adjacent to the column. Eng. Struct. 2019, 182, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.H.; Soudki, K.A.; Dusen, M.V. CFRP strengthening for punching shear of interior slab–column connections. J. Compos. Constr. 2006, 10, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, M.R. Effect of cyclic loading on punching shear strength of slabs strengthened with carbon fiber polymer sheets. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2008, 6, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Farghaly, A.S.; Ueda, T. Punching strength of two-way slabs strengthened externally with FRP sheets. JCI Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2009, 31, 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, H. Improvement of Punching Strength of Flat Plates by Using Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Dowels. Ph.D. Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, T.; Tarka, J. Strengthening of slab–column connections with CFRP strips. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2010, 56, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, Z.; Ghrib, F.; El-Ragaby, A.M.; Sennah, K. Behavior of RC slab–column connections strengthened with external cfrp sheets and subjected to eccentric loading. J. Compos. Constr. 2013, 17, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.; Abadel, A.A.; Almusallam, T.; Al Salloum, Y. Effect of CFRP and TRM strengthening of RC slabs on punching shear strength. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2015, 12, 1616–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radik, M.J.; Erdogmus, E.; Schafer, T. Strengthening two-way reinforced concrete floor slabs using polypropylene fiber reinforcement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. ASCE 2011, 23, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudki, K.; El-Sayed, A.K.; Vanzwol, T. Strengthening of concrete slab–column connections using CFRP strips. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2012, 24, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, H.; Zohrevand, P.; Mirmiran, A. Effectiveness of externally applied CFRP stirrups for rehabilitation of slab–column connections. J. Compos. Constr. ASCE 2013, 17, 04013008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.H.; El-Salakawy, E.F. Punching shear behavior of glass fiber-reinforced polymer-reinforced concrete slab–column interior connections. ACI Struct. J. 2018, 115, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.D.; Oliveira, M.H.; Sales, G.; Melo, S.A. Tests on the punching resistance of flat slabs with unbalanced moments. Eng. Struct. 2019, 196, 109311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.L.; Gamagea, J.C.P.H.; Fawzia, S. Performance of slab–column connections of flat slabs strengthened with carbon fiber reinforced polymers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durucan, C.; Anil, O. Effect of opening size and location on punching shear behavior of interior slab–column connections strengthened with CFRP strips. Eng. Struct. 2015, 105, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.A.; Khattab, R.; Okasha, R. Numerical analysis of RC slab with opening strengthened with CFRP laminates. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 603, 042038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapi, M.; Ramos, A.P.; Orlando, M. Flat slab strengthening techniques against punching-shear. Eng. Struct. 2019, 180, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gasham, T.S.; Mhalhal, J.M.; Jabir, H.A. Improving punching behavior of interior voided slab–column connections using steel sheets. Eng. Struct. 2019, 199, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.; Kalfat, R.; Abdouka, K.; Al-Mahaidi, R. Punching shear strengthening of RC slabs using L-CFRP laminates. Eng. Struct. 2019, 194, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.Y.M.; Hrynyk, T.D. Numerical investigation of the punching resistance of reinforced concrete flat plates. J. Struct. Eng. ASCE 2018, 144, 04018166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).