Abstract

The structural origin of the germanate anomaly in glasses, which involves complex Ge–O coordination environments, is frequently studied using crystalline analogs. This study aims to provide reliable spectroscopic fingerprints by performing a detailed structural and thermal analysis of crystalline A4Ge9O20 model systems with A = Li, Na, K. The compounds were synthesized via melt crystallization and characterized using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and Raman spectroscopy techniques. The results demonstrate clear cation-dependent crystallization pathways. The Li-containing system predominantly forms Li2Ge7O15 in mixture with Li4Ge9O20, indicating a preference for thermodynamically stable phases. The Na-system successfully yields the target Na4Ge9O20 compound. In contrast, the K-system primarily produces the likely metastable K2Ge4O9 phase with a significant amorphous fraction, highlighting the role of kinetic limitations. This comparative study demonstrates that the size of the alkali cation is a critical factor for controlling phase formation under identical stoichiometric and thermal conditions.

1. Introduction

Germanate glasses possess unique physical properties and exhibit unusual behavior upon the addition of modifiers (see, for example, Refs. [1,2,3]). They are considered structurally anomalous compared to their silicate analogs, as their physical properties, such as density, hardness, glass transition temperature, Young’s modulus, etc., often exhibit extrema as a function of composition (see, for example, [4,5,6]). The germanate anomaly was first observed by Ivanov and Evstropiev [7] in sodium and potassium germanate glasses, and by Murthy and Ip [8] in lithium-, rubidium- and caesium-containing germanate glasses. This behavior, known as the ‘germanate anomaly’, is closely associated with the average Ge–O coordination number. Germanate anomaly arises from structural rearrangements in the germanate network, where GeO5 and GeO6 polyhedral may form alongside GeO4 units, leading to increased network connectivity and altered property trends. The anomaly is particularly prominent in alkali and alkaline earth germanate glasses, where modifier oxides (e.g., Na2O, CaO) induce coordination number changes in Ge [9,10,11,12].

While both GeO5 and GeO6 coordination units are known to coexist in germanate glasses, their quantitative segregation is still difficult to determine. Techniques like Raman and X-ray absorption spectroscopy often show overlapping spectral features for these intermediate and high-coordination states, requiring comprehensive fitting procedures. Thus, investigating the structural origins of the germanate anomaly in oxide glasses and establishing the relationship between composition, Ge–O coordination, and physicochemical properties remains a challenging task.

Unlike oxide glasses, which exhibit a wide range of Ge–O coordination environments, crystalline germanates possess well-defined and stable Ge coordination states, making them valuable reference systems for structural studies. The synthesis and characterization of definite crystalline phases have been a cornerstone in understanding of germanate chemistry. Early phase equilibrium studies in A2O–GeO2 (A = Li, Na, K) systems by Murthy and coworkers [13,14,15] established the existence of numerous stoichiometric compounds, providing a fundamental framework for subsequent research. For instance, the synthesis and single-crystal structure determination of Li4Ge9O20 by Völlenkle et al. [16] and Li2Ge7O15 by the same group [17] revealed complex networks of GeO4 tetrahedra and GeO6 octahedra, offering direct structural models for coordination environments in glasses.

Raman spectroscopy has proven to be a particularly powerful tool for investigating the local structure in both crystalline and glassy germanates. Early work by Furukawa and White [18] provided a comprehensive set of Raman spectra for binary alkali germanate glasses and their crystallized products. Their study established clear correlations between specific vibrational bands and the prevailing germanium coordination. Subsequent investigations on other crystalline germanates, such as Na2Ge8O17 and K2Ge8O17, have further enriched the library of reference spectra, thereby enabling the interpretation of the more complex glass spectra.

Determination of the correlation between crystalline and glass-like phases, as well as comparison of the coordination of Ge in crystals and glasses with the same composition, provides critical insights into the nature of the germanate anomaly. Also, comparison with crystal analogs allows for clarifying the local environment of Ge in glasses (GeO4 vs. GeO5 vs. GeO6).

Therefore, to clarify complex structural architecture of germanate glasses, this study employs a comparative methodology using structurally characterized crystalline analogs. Crystalline compounds with the general formulas A4Ge9O20 (where A = Li, Na, K) were chosen as reference systems at the initial research stage. The primary objective is to perform a detailed structural and spectroscopic investigation of these crystalline phases to identify clear and definitive spectral signatures for each germanium coordination environment. These established “fingerprints” will then be used to assign overlapping spectral features observed in the corresponding glasses. This approach will provide critical quantitative insights into the coordination changes driven by modifier content, leading to better understanding of the structural rearrangements that underpin the germanate anomaly and its profound effect on the properties of germanate glasses.

This manuscript reports a comprehensive structural and thermal study of crystalline A4Ge9O20 (A = Li, Na, K) model systems using PXRD, DSC, and Raman spectroscopy. The aim is to establish clear Raman spectral signatures for specific Ge–O coordination environments. The reference spectra obtained here provide a foundational dataset for the spectral interpretation and quantitative analysis of corresponding germanate glasses.

2. Materials and Methods

Two subsequent routes were applied to prepare specimens for further investigation. In the first stage, alkali-germanates glasses were synthesized using analytical grade alkali carbonates, A2CO3 (A = Li, Na, K) and 99.999% pure germanium dioxide. The starting reagents were mixed in stoichiometric ratios corresponding to A4Ge9O20 compound, following the reactions:

2A2CO3 + 9GeO2 → A4Ge9O20 + 2 CO2↑

The mixture was thoroughly homogenized and melted in a platinum crucible in a SNOL 12/12 muffle furnace (SNOL-Term, Tver, Russia), heating to 1100 °C and holding for 1 h for complete homogenization of the melt. After pouring into a steel mold, the melt was cooled in air.

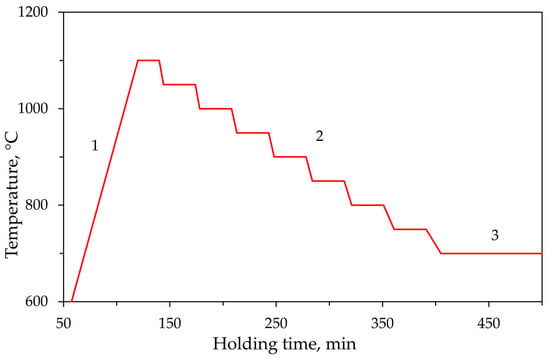

The glasses were then ground, placed in quartz crucibles, and heated to 1100 °C. Subsequently, they were cooled using a controlled stepwise regime, holding for 30 min at every 50 °C interval (as shown in Figure 1). Finally, the samples were held at 700 °C for 24 h to ensure system stabilization.

Figure 1.

Thermal treatment profile for glass crystallization: (1) heating to 1100 °C; (2) controlled cooling with 30 min holds at 50 °C intervals; (3) isothermal annealing at 700 °C for 24 h.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were performed using the STA 449 F5 Jupiter instrument (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). The experiments were carried out in PtRh20 crucibles with a volume of 85 μL. All DSC curves were recorded in the heating-cooling cycle from 50–1150 °C at a constant heating rate of 20 °C/min under a continuous argon gas flow.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis was conducted using a Rigaku MiniFlex-600 diffractometer (Rigaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with Cu-Kα1,2 wavelengths (1.54051 and 1.54433 Å). Datasets were collected in continuous mode at room temperature over the 2θ range of 3–70° with a scanning rate of 5°/min. Phase identification was performed using the Pearson’s Crystal Data (PCD) database [19], Crystallography Open Database (COD) [20]. To further elucidate the thermal behavior, selected samples underwent thermal treatment on a Pt plate at 1100 °C for 1 h. The products after thermal treatment were analyzed using the PXRD method to identify any changes in the crystal structure or phase composition.

The Raman spectra of the samples were recorded in the spectral range of 100–1700 cm−1 using a Renishaw inVia Reflex (λ = 532 nm) confocal Raman microscope (Renishaw, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom) equipped with 50 mW diode lasers in combination with a charged-coupled device (CCD) array detector (Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry, RAS, Moscow, Russia).

3. Results and Discussion

Figure 2 presents images of the original glasses. The Li4Ge9O20 composition demonstrates effective crystallization in air, while Na4Ge9O20 glass shows only partial crystallization under the same quenching conditions. In contrast, the potassium germanate glass remains amorphous after this quenching process.

Figure 2.

As-synthesized original glasses after air quenching.

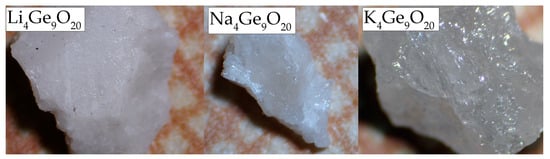

Annealing yielded polycrystalline samples. While LiGe and NaGe are fine-grained, white or light-gray ceramics, KGe appears as a semi-transparent gray glass-ceramic sample (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Optical images of the synthesized samples.

The results of the phase identification in A2O – GeO2 (A = Li, Na, K) systems by PXRD technique are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of phase identification.

3.1. The 2Li2O–9GeO2 Composition

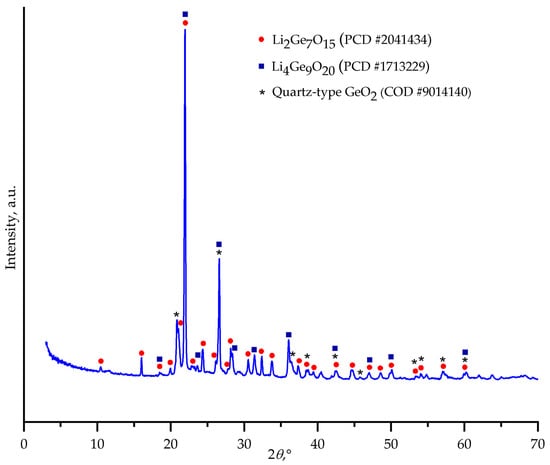

PXRD analysis revealed that the crystallization process yielded a mixture of three phases: lithium heptagermanate (Li2Ge7O15) as dominant compound, lithium enneagermanate (Li4Ge9O20), and a minor quartz-type GeO2 phase (Figure 4). The coexistence of several phases is typical for the Li2O-GeO2 system, as reported in previous studies [13,21].

Figure 4.

Powder X-ray diffraction pattern of the crystallization products obtained from the melt of nominal 2Li2O–9GeO2 composition.

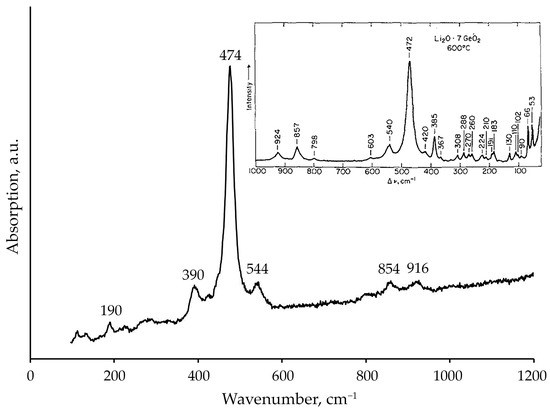

Raman spectroscopy provided further confirmation of the predominant phase formation (Figure 5). The observed spectrum exhibited characteristic bands at approximately 190, 390, 474, 544, 854, and 916 cm−1. This profile shows excellent agreement with the reference spectrum of Li2Ge7O15 crystallized from Li2O–7GeO2 glass at 600 °C reported by Furukawa and White [18]. The strong correspondence, particularly in the medium-frequency region (400–600 cm−1) and the high-frequency range (800–950 cm−1), identifies Li2Ge7O15 as the major crystalline phase in the system studied.

Figure 5.

Raman spectrum of the crystallization products obtained from the melt of nominal 2Li2O–9GeO2 composition. The inset shows the Raman spectrum of Li2Ge7O15 crystallized from the Li2O–7GeO2 glass at 600 °C, as reported by [18].

According to Refs. [22,23] the crystal structure of lithium heptagermanate can be characterized by the chemical formula Li2[[VI]Ge([IV]Ge2O5)3]. The Li2Ge7O15 compound adopts a three-dimensional framework structure, formed by highly distorted layers of [GeO4] tetrahedra that are linked together via [GeO6] octahedra. Although lithium heptagermanate exhibits an orthorhombic structure, it can be viewed as a derivative of the hexagonal quartz-like GeO2, with channels formed along the pseudohexagonal axis. The Li+ cations serve to compensate for the excess negative charge associated with the [GeO6] octahedra.

From the literature data, it is known that the frequency range of 300–700 cm−1 is primarily associated with vibrations of [GeO4] tetrahedra and highly coordinated germanium atoms, whereas scattering in the 700–1100 cm−1 range is attributed to vibrations of Qn structural units. It is established that in alkali germanates with up to 15 mol% alkali metal oxide, a sufficient concentration of non-bridging oxygen atoms does not appear [24,25,26]. Consequently, the bands at 854 and 916 cm−1 in the high-frequency region of the Raman spectra of the germanates studied in this work are due to the TO/LO splitting of antisymmetric stretching vibrations of Ge-O-Ge bonds [26,27,28,29].

Raman spectroscopic analysis reveals a dominant peak at ~474 cm−1, corresponding to the vibrational modes of the Ge–O bonds within the [GeO4] tetrahedra. The band at 474 cm−1, similar to the 440 cm−1 band in the spectrum of trigonal quartz-type GeO2, is assigned to deformation vibrations [27]. In several studies [24], the interpretation of this band has been refined as symmetric stretching vibrations of [IV]Ge–O–[IV]Ge bridges within six-membered or four-membered rings [28] formed by [GeO4] tetrahedra. Furthermore, there is a suggestion that this band may be associated with the formation of five-coordinated germanium [9,25,26].

The band at 544 cm−1 indicates the presence of six-coordinated germanium [GeO6]. Based on the study of crystalline Rb2Ge4O9, Kamitsos et al. [24] suggested that this band is associated with the formation of a bridging bond [IV]Ge–O–[VI]Ge. The low-frequency band at 190 cm−1 lacks a definitive interpretation but is most likely caused by vibrations involving oxygen bonds with modifier cations. Additionally, the band at 390 cm−1 may be attributed to symmetric stretching vibrations, partly mixed with deformation vibrations, of Ge–O–Ge bonds [9], though its precise structural origin remains unknown.

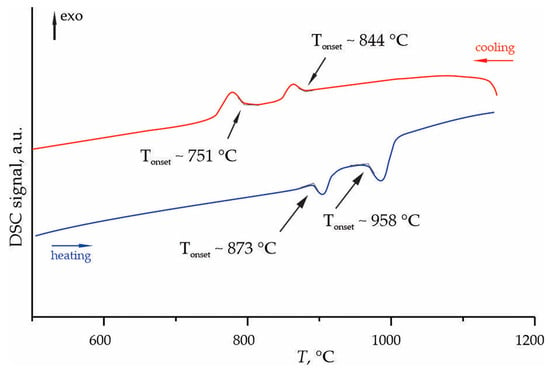

DSC analysis of the phases crystallized from the 2Li2O–9GeO2 melt revealed complex thermal behavior during heating and cooling cycles (Figure 6). During heating, two endothermic peaks were detected with onset temperatures (Tonset) of 873 °C and 958 °C. Subsequent cooling showed exothermic peaks at 844 °C and 751 °C, indicating a multi-stage crystallization process.

Figure 6.

Fragment of the DSC curves of the phases crystallized from the melt of nominal 2Li2O–9GeO2 composition, measured in the temperature range of 50–1200 °C.

Comparison with the established Li2O–GeO2 phase diagram [13] suggests that the endothermic peaks at 873 °C and 958 °C likely correspond to eutectic reactions rather than melting of pure compounds. The lower temperature peak (873 °C) may be attributed to the eutectic between Li2Ge7O15 and Li4Ge9O20 phases, while the higher temperature peak (958 °C) could correspond to the eutectic involving Li2Ge7O15 and GeO2. The exothermic peaks observed during cooling at 844 °C and 751 °C represent crystallization from the melt. The higher temperature peak (844 °C) likely corresponds to the primary crystallization of Li2Ge7O15, while the lower temperature one (751 °C) may indicate the crystallization of the eutectic mixture. This two-stage crystallization behavior is characteristic for complex multicomponent systems and reflects the kinetic competition between different crystalline phases [21].

The Li2O–GeO2 system has been reported by Murthy & Ip [13] to contain five congruently melting compounds: Li2O·7GeO2, 3Li2O·8GeO2, Li2O·GeO2, 3Li2O·2GeO2 and 2Li2O·GeO2 with melting points of 1033 ± 5 °C, 953 ± 5 °C, 1245 ± 15 °C, 1125 ± 15 °C, and 1280 ± 15 °C, respectively. The authors also described simple binary eutectic relations existing among the compounds. In Ref. [16], the synthesis of lithium enneagermanate (Li4Ge9O20) was reported. It involved melting a stoichiometric mixture of Li2CO3 and GeO2 at 1200 °C, followed by air cooling of the melt. Slow air cooling was emphasized as essential for obtaining the target compound. Rapid cooling, such as quenching the crucible in water, resulted in glass formation, while excessively slow cooling led to the crystallization of impurity phases. The DSC data obtained suggest that the cooling rate in our experiments favored the formation of Li2Ge7O15 as the dominant phase, with Li4Ge9O20 as a secondary one.

The crystallization behavior observed in the sample of composition 2Li2O–9GeO2 shows both similarities and differences with the devitrification of lithium germanate glasses reported in the literature. Pernice et al. [21] studied the crystallization of Li2O–5GeO2 glass and observed a three-step process involving metastable Li2Ge4O9 formation followed by conversion to stable Li2Ge7O15 and finally GeO2 crystallization at higher temperatures. In our case, the direct formation of Li2Ge7O15 and Li4Ge9O20 without detectable metastable intermediates suggests different crystallization pathways between bulk and glass-ceramic systems. The absence of Li2Ge4O9 in our products is particularly noteworthy. This phase, which is kinetically favored but thermodynamically metastable [17,21], apparently does not form under our synthesis conditions, possibly due to the direct crystallization from the melt rather than through glass devitrification. The structural similarity between Li2Ge7O15, Li4Ge9O20, and Li2Ge4O9, containing chains of GeO4 tetrahedra linked by GeO6 octahedra, may facilitate rapid conversion of any metastable phases to the stable Li2Ge7O15 structure in our system. This could explain why only the stable phases are detected in the final crystallization products.

3.2. The 2Na2O–9GeO2 Composition

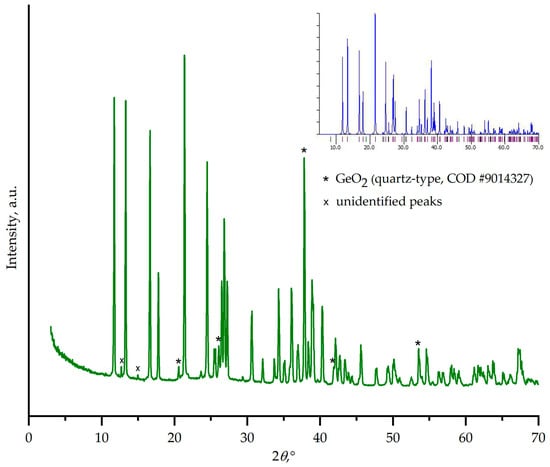

The phase composition of the phases crystallized from the 2Na2CO3–9GeO2 melt was unambiguously determined using a combination of powder X-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy techniques. The PXRD pattern (Figure 7) confirmed that the crystallization process primarily yielded the target phase, sodium enneagermanate Na4Ge9O20. All major reflections correspond well with the reference pattern (PDF #00-018-02368), establishing it as the dominant crystalline component [14,30].

Figure 7.

Powder X-ray diffraction pattern of the crystallization products obtained from the melt of nominal 2Na2CO3–9GeO2 composition. The pattern matches the calculated one for Na4Ge9O20 (PCD #1802368, see inset).

In addition to the target phase, several other reflections were observed. Peaks associated with a quartz-type GeO2 phase were identified, which is consistent with the phase equilibrium data for the Na2O–GeO2 system. Furthermore, two low-intensity peaks at 2θ ≈ 12.8° and 15° remain unassigned. These reflections do not match any known stable phases in the Na2O–GeO2 system or the starting materials. Their origin is unclear but may be attributed to a metastable intermediate or a minor, unidentified impurity phase.

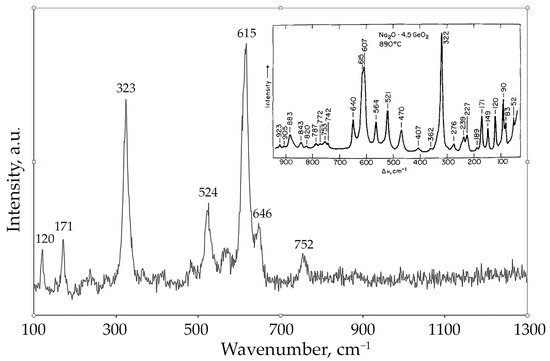

The Raman spectrum (Figure 8) of the phases crystallized from the 2Na2CO3-9GeO2 melt shows characteristic bands at 120, 171, 323, 524, 615, 646, 752, and 819 cm−1. This profile fits well with the Raman spectrum of Na4Ge9O20 crystallized from the Na2O·4.5GeO2 glass at 890 °C, as reported by Furukawa and White [18]. The bands at 615 and 646 cm−1 are evidently associated with the presence of vibrations from six-coordinated germanium atoms [24], while the vibration in the 323 cm−1 region indicates long-range order in crystalline sodium germanate. The band at 524 cm−1 is likely related to vibrations of mixed ring units containing [GeO4] tetrahedra and [GeO6] octahedra [27]. The low-intensity band at 752 cm−1 arises from Ge-O bond vibrations in germanate tetrahedra. The low-frequency bands at 120 and 171 cm−1 present in the spectrum of crystalline Na4Ge9O20 represent vibrations of various types of oxygen bonds with sodium cations.

Figure 8.

Raman spectrum of the crystallization products obtained from the melt of nominal 2Na2CO3–9GeO2 composition. The inset shows the Raman spectrum of Na4Ge9O20 crystallized from the Na2O–4.5GeO2 glass at 890 °C, as reported by [18].

The strong correlation between the PXRD and Raman data provides robust evidence for the successful synthesis of the Na4Ge9O20 phase. The structure of sodium enneagermanate has both four- and six-fold coordinated Ge atoms. Germanium atoms occupy three non-equivalent crystallographic positions: one tetrahedral site Ge(1), one tetrahedral site Ge(2), and one octahedral site Ge(3) [31]. This results in an octahedral-to-tetrahedral Ge ratio of 4:5. The corresponding crystal-chemical formula is Na2[IV]Ge5[VI]Ge4O20. The Raman spectra of Na4Ge9O20 are characterized by intense peaks at approximately 323, 615, and 646 cm−1, which can be attributed to vibrational modes of the [GeO6] octahedra.

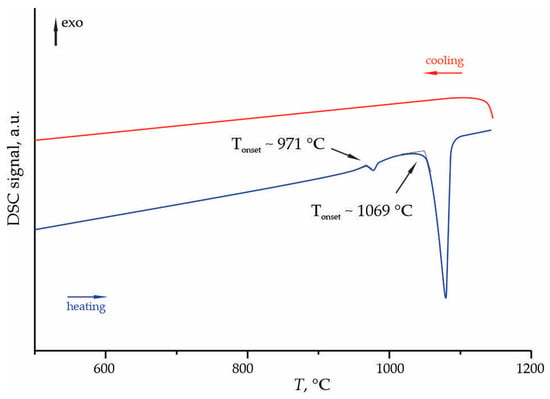

Figure 9 shows the fragment of the DSC curves for the sample in the 500–1200 °C temperature range. The heating curve exhibits two endothermic peaks with onset temperatures of ~971 and ~1020 °C, while no exothermic peaks were detected during cooling. The first endothermic peak at~971 °C aligns closely with the reported eutectic temperature of 950 ± 10 °C between Na4Ge9O20 and GeO2 [14]. This provides direct thermal evidence for the presence of the GeO2 impurity phase, as identified by PXRD, and corresponds to the melting of this eutectic mixture.

Figure 9.

Fragment of the DSC curves of the phases crystallized from the melt of nominal 2Na2O-9GeO2 composition, measured in the temperature range of 50–1200 °C.

The second more pronounced endothermic peak at~1020 °C can be assigned to the melting of the Na4Ge9O20 phase. The measured temperature is in reasonable agreement with the literature value of 1073 ± 3 °C [14], with the minor discrepancy likely attributable to experimental factors such as heating rate or instrument calibration. The clear separation of these two melting events confirms the multiphase nature of the sample as determined by PXRD.

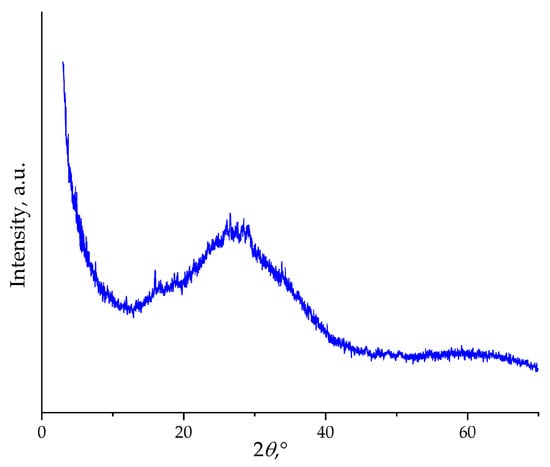

The absence of exothermic peaks during cooling indicates no crystallization occurs, suggesting two possible pathways: either Na4Ge9O20 melts incongruently, decomposing into different phases upon heating, or the melt exhibits strong glass-forming tendency at the employed cooling rates. The latter scenario appears more probable given the known glass-forming ability of germanate systems. To verify this, the 2Na2O–9GeO2 composition was melted and rapidly quenched, and the resulting product was analyzed by powder X-ray diffraction technique (Figure 10). The PXRD pattern confirms the amorphous nature of the sample, as evidenced by a broad scattering halo and the absence of any sharp crystalline peaks.

Figure 10.

Powder X-ray diffraction pattern of the 2Na2O–9GeO2 composition. The pattern exhibits a characteristic broad halo with no crystalline reflections, confirming the amorphous state of the material after thermal treatment.

3.3. The 2K2O–9GeO2 Composition

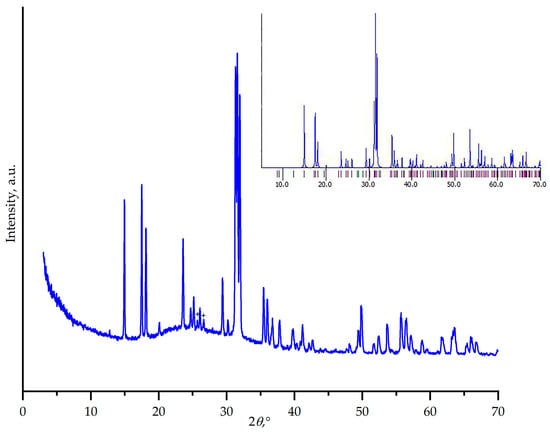

Powder X-ray diffraction analysis of the crystallization products obtained from the 2K2CO3–9GeO2 melt demonstrates the formation of dipotassium tetragermanate, K2Ge4O9, as the primary crystalline phase. All major reflections in the diffraction pattern correspond well to the reference pattern for K2Ge4O9 (Figure 11). In addition to the sharp Bragg peaks of K2Ge4O9, the XRD pattern exhibits a broad halo at low angles, indicative of a significant amorphous component, suggesting incomplete crystallization. Furthermore, two medium-intensity peaks at 2θ~12.8° and ~25.7° remain unassigned. These reflections do not correspond to any known phases in the K2O–GeO2 system or potential impurities from the starting materials. Their origin may be attributed to a metastable intermediate or a minor secondary phase that could not be identified, highlighting the complexity of phase formation in this system. The target compound K4Ge9O20 seems to be a metastable phase crystallized over the wide composition range.

Figure 11.

Powder X-ray diffraction pattern of the crystallization products obtained from the melt of nominal 2K2CO3–9GeO2 composition. The pattern matches the calculated one for K2Ge4O9 (COD #2019133, see inset). Unassigned peaks are marked with “+”.

The phase relations in the K2O–GeO2 system, however, present a complex and historically debated picture. Early studies by Schwarz and Heinrich [32] reported K2Ge4O9 (as K2O·4GeO2) as a stable compound. In contrast, the detailed reinvestigation by Murthy et al. [15] using quenching techniques identified three distinct stable compounds in the composition range of 65 to 100 mol.% GeO2: K2O·2GeO3, K2O·7GeO3, and 3K2O·11GeO3, and with no evidence of K2Ge4O9. A thorough reinvestigation of the K2O–GeO2 system in the 78–82 mol% GeO2 region revealed and confirmed, via X-ray data, the phase 3K2O·11GeO2, rather than the previously reported K2O·4GeO2. Furukawa and White [18] suggested K2Ge4O9 as a stable phase. They noted that X-ray diffraction pattern of 3K2O·11GeO2 [15] is identical to that of single-crystal K2Ge4O9, obtained from oxide-fluoride melts with slow cooling [33]. This disagreement suggests that K2Ge4O9 may be a metastable phase that forms under specific kinetic conditions rather than at thermodynamic equilibrium. On the other hand, the authors of Ref. [34] successfully synthesized K2Ge4O9 under hydrothermal conditions in KF-containing systems, demonstrating that this phase can be stabilized through the employed crystallization route.

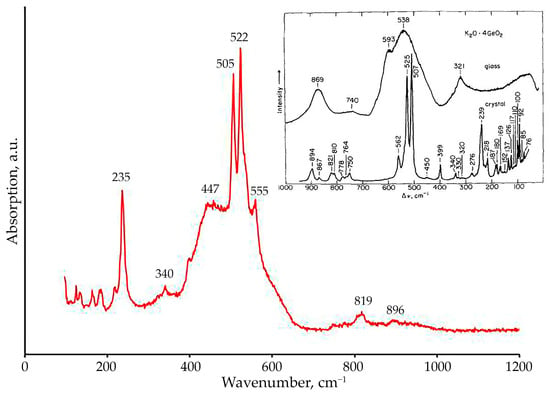

The phase identification was further corroborated by Raman spectroscopy. The spectrum of the crystallization products (Figure 12) shows characteristic bands at 235, 340, 447, 505, 522, 555, 819, and 896 cm−1. These spectral features are consistent with literature data for the K2Ge4O9 phase [18] and agree well with the PXRD results, confirming the local structure of the synthesized compound. The crystal structure exhibits Ge atoms in both four- and six-fold coordination in a 1:3 ratio. The set of bands in the low-frequency region of 100–300 cm−1, with the most intense at 235 cm−1, corresponds to potassium-oxygen bond vibrations, which may be partially deformational or stretching in nature [27]. The strong doublet observed at 505–522 cm−1 is assigned to [IV]Ge-O-[VI]Ge bridges connecting tetrahedral and octahedral germanium units. Similarly, the band at 555 cm−1 is attributed to the symmetric stretching vibration of [IV]Ge-O-[IV]Ge bridges in three-membered rings of [GeO4] tetrahedra, as well as of mixed [IV]Ge-O-[VI]Ge bridges. [24,26,35]. The bands around 819 and 896 cm−1 can also be attributed to the TO/LO splitting of antisymmetric stretching vibrations of Ge-O-Ge bonds [26,27,28,29].

Figure 12.

Raman spectrum of the crystallization products obtained from the melt of nominal 2K2CO3–9GeO2 composition. The inset shows the Raman spectra of K2O–4GeO2 glass and glass crystallized at 810 °C, reproduced from [18].

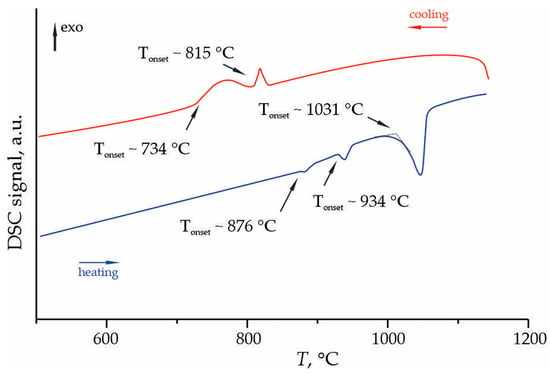

DSC analysis of the phases crystallized from the 2K2O–9GeO2 melt demonstrate complex thermal behavior during heating and cooling cycles (Figure 13). During heating, three endothermic peaks were detected Tonset of 876 °C, 934 °C, and 1031 °C. Subsequent cooling showed exothermic peaks at 815 °C and 734 °C, indicating a multi-stage crystallization process.

Figure 13.

Fragment of the DSC curves of the phases crystallized from the melt of nominal 2K2O–9GeO2 composition, measured in the temperature range of 50–1200 °C.

Interpreting these thermal events in the context of the established phase diagram for the K2O–GeO2 system [15] allows for their tentative assignment. The composition of our sample (∼18.2 mol% K2O, ∼81.8 mol% GeO2) lies within the primary crystallization field of GeO2, close to the boundary with the compound K2O·7GeO2. The high-temperature endotherm at ~1031 °C can be attributed to the liquidus temperature for this composition, representing the final melting of the crystalline assemblage. The endotherm at ~934 °C likely corresponds to the peritectic decomposition of K2O·7GeO2. According to Murthy et al. [15], this compound melts incongruently at 950 °C into a liquid and crystalline 3K2O·11GeO3. The slight discrepancy in temperature (950 °C vs. 934 °C) can be explained by kinetic effects, the heating rate used in DSC, and the fact that our sample is a bulk glass/ceramic mixture rather than an equilibrium mixture of pure crystalline phases.

The endotherm at ~876 °C can be assigned to the eutectic reaction between the remaining solid phases. The most probable candidate is the eutectic between K2O·2GeO3 and 3K2O·11GeO3, which, according to the phase diagram [15], occurs at a temperature very close to the peritectic melting of K2O·2GeO3 at 761 °C. However, the significantly higher temperature observed here suggests the involvement of other phases or a metastable eutectic reaction in our non-equilibrium sample.

The cooling curve exhibits two exothermic peaks at 815 °C and 734 °C, indicating a multi-stage crystallization process from the melt. The peak at ~815 °C likely corresponds to the primary crystallization of a potassium germanate phase, possibly K2O·7GeO2 or 3K2O·11GeO3. The lower temperature crystallization event at ~734 °C may signify the formation of a second crystalline phase or a polymorphic transformation. This complex crystallization behavior, coupled with the presence of a significant amorphous phase identified by XRD, points to substantial kinetic limitations and a strong tendency for glass formation during solidification in the K2O–GeO2 system.

The comparative investigation of the crystallization behavior in the A4Ge9O20 (where A = Li, Na, K) systems reveals distinct phase formation pathways, strongly influenced by the alkali cation size and the thermal history of the samples.

In the lithium system, the crystallization products were dominated by Li2Ge7O15, with Li4Ge9O20 as a secondary phase. The absence of the metastable Li2Ge4O9 phase, often reported in devitrified glasses, suggests that direct crystallization from the melt under the employed thermal regime favors thermodynamically stable phases. This behavior is reflected in the observed thermal events: two-stage melting occurs at ~873 °C and ~958 °C, corresponding to eutectic transformations involving Li2Ge7O15 and Li4Ge9O20, while upon cooling, crystallization proceeds in two stages at ~844 °C (primary crystallization of Li2Ge7O15) and ~751 °C (crystallization of the eutectic mixture). These multi-stage thermal events align with the complex eutectic relationships in the Li2O–GeO2 system, corroborating the phase coexistence identified by PXRD and Raman spectroscopy. The structural similarity between Li2Ge7O15 and Li4Ge9O20, both featuring chains of [GeO4] tetrahedra interconnected by [GeO6] octahedra, may facilitate rapid phase stabilization, bypassing metastable intermediates.

For the sodium system, the successful synthesis of the target Na4Ge9O20 phase was confirmed by both PXRD and Raman spectroscopy. The presence of a GeO2 impurity and unidentified minor phases, however, indicates slight deviations from ideal stoichiometric crystallization. The DSC heating curve showed clear endotherms corresponding to the eutectic melting of Na4Ge9O20 + GeO2 at ~971 °C and the melting of Na4Ge9O20 itself at ~1020 °C. The lack of crystallization exotherms upon cooling underscores the strong glass-forming tendency of this composition, consistent with the known behavior of sodium germanate systems and indicating kinetic suppression of crystallization under the applied cooling regime.

The potassium system exhibited the most complex behavior, with K2Ge4O9 identified as the primary crystalline phase. This phase is likely metastable, as it is not present in the equilibrium phase diagram but forms under specific kinetic conditions, supported by earlier hydrothermal synthesis reports. The thermal analysis reveals three endothermic events upon heating: ~876 °C (possibly a metastable eutectic), ~934 °C (peritectic decomposition of the K2O·7GeO2 compound), and ~1031 °C (liquidus). Upon cooling, crystallization occurs in two stages at ~815 °C (primary crystallization, likely of K2O·7GeO2) and ~734 °C (secondary crystallization or polymorphic transformation). The significant amorphous background in the PXRD pattern and the multi-stage thermal events in DSC highlight the strong kinetic inhibition to crystallization and the propensity for glass formation in the K2O–GeO2 system. The unidentified peaks in the PXRD pattern further suggest the presence of transient or minor phases that could not be stabilized under the given conditions.

Thus, under identical stoichiometric and thermal conditions, the size of the alkali metal cation critically influences thermal behavior and phase selection: small Li+ promotes the formation of stable crystalline phases with clear melting and crystallization temperatures, intermediate Na+ suppresses crystallization upon cooling, favoring glass formation, and large K+ leads to complex, multi-stage melting and crystallization with a predominance of metastable phases and kinetic barriers. These differences highlight the key role of cation radius in controlling phase selection and thermal history in germanate systems.

4. Conclusions

This comparative study of A4Ge9O20 (A = Li, Na, K) systems synthesized under identical conditions demonstrates the critical role of alkali cation size in directing phase formation and thermal behavior. The small Li+ cation favors the crystallization of thermodynamically stable phases (Li2Ge7O15 and Li4Ge9O20), with clear multi-stage melting and crystallization events. The intermediate Na+ cation allows successful formation of the target Na4Ge9O20 phase but also shows a strong glass-forming tendency upon cooling, suppressing crystallization. The large K+ cation leads to complex, kinetically controlled behavior, primarily forming the likely metastable K2Ge4O9 phase alongside a significant amorphous fraction, highlighting substantial kinetic barriers. Thus, under fixed stoichiometry and thermal history, the alkali cation radius determines the crystallization pathway, modulating the competition between thermodynamic stability and kinetic limitations. The obtained Raman spectra for the crystalline phases establish clear spectroscopic features for specific Ge–O coordination environments. These reference data provide a foundation for interpreting the complex, overlapping spectral features in corresponding germanate glasses, advancing the quantitative understanding of the structural rearrangements underlying the germanate anomaly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.V. and O.N.K.; methodology, E.A.V. and O.N.K.; validation, E.A.V., O.N.K., L.A.N., E.Y.K. and V.L.K.; formal analysis, E.A.V., O.N.K., L.A.N., E.Y.K. and V.L.K.; investigation, E.A.V., O.N.K., L.A.N., E.Y.K. and V.L.K.; resources, E.A.V. and O.N.K., and V.L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.V. and O.N.K.; writing—review and editing, E.A.V. and O.N.K.; visualization, E.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out within the framework of the State Assignment of the Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow, Russia).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kiczensk, T.J.; Ma, C.; Hammarsten, E.; Wilkerson, D.; Affatigato, M.A.; Feller, S. A study of selected physical properties of alkali germanate glasses over wide ranges of composition. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2000, 272, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaky, K.M.; Sayyed, M.I. Selected germanate glass systems with robust physical features for radiation protection material use. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 215, 111321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serkina, K.S.; Knyazkova, O.V.; Stepanova, I.V.; Runina, K.I.; Sektarov, E.S. Properties of Sodium-Germanate Glasses Doped by Bismuth, Thulium, and Erbium. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2025, 89, 2053–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulos, Y.D.; Varsamis, C.; Kamitsos, E.I. Density of Alkali Germanate Glasses Related to Structure. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2001, 293, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rednic, V.; Rada, M.; Culea, E.; Rada, S.; Bot, A.; Aldea, N. Anomalies of some physical properties and electrochemical performance of lithium lead germanate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 3129–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.K.; Sapian, I.N.; Hisam, R.; Yusof, M.I.M. The influence of germanate anomaly on elastic moduli and Debye temperature behavior of xLi2O-(100 − x)[0.65GeO2·0.35PbO] glass system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 493, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.O.; Evstrop’ev, K.S. On the structure of simple germanate glass. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1962, 145, 797–800. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, M.K.; Ip, J. Some physical properties of alkali germinate glasses. Nature 1964, 201, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.S.; Wang, H.M. Germanium coordination and the germanate anomaly. Eur. J. Mineral. 2002, 14, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.S. The germanate anomaly: What do we know? J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, O.L.G.; Hannon, A.C.; Feller, S.; Beanland, R.; Holland, D. The Germanate Anomaly in Alkaline Earth Germanate Glasses. J. Phys. Chem. 2017, C121, 9462–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, R.S.; Wilkinson, C.J.; Shih, Y.-T.; Bødker, M.S.; DeCeanne, A.V.; Smedskjaer, M.M.; Huang, L.; Affatigato, M.; Feller, S.A.; Mauro, J.C. Topological model of alkali germanate glasses and exploration of the germanate anomaly. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 4224–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, M.K.; Ip, J. Studies in germanium oxide systems: I, Phase equilibria in the system Li2O–GeO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1964, 47, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, M.K.; Aguayo, J. Studies in germanium oxide systems: II, Phase equilibria in the system Na2O–GeO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1964, 47, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, M.K.; Long, L.; Ip, J. Studies in germanium oxide systems: IV, Phase equilibria in the system K2O–GeO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1968, 51, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völlenkle, H.; Wittmann, A.; Nowotny, H. Die Kristallstruktur des Lithium-enneagermanats Li4[Ge9O20]. Monatshefte Chem. 1971, 102, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völlenkle, H.; Wittmann, A.; Nowotny, H. Die Kristallstruktur des Lithiumheptagermanats Li2[Ge7O15]. Monatshefte Chem. 1970, 101, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; White, W.B. Raman spectroscopic investigation of the structure and crystallization of binary alkali germanate glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 1980, 15, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villars, P.; Cenzual, K. Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds (on DVD); Release 2023/24; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://crystallography.net (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Pernice, P.; Aronne, A.; Marotta, A. Crystallizing phases and kinetics of crystal growth in Li2O·19GeO2 glass. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1992, 11, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgashev, V.; Yuzyuk, J.; Latush, L.; Burmistrova, L.; Kadlec, F.; Smutný, F.; Petzelt, J. Infrared and Raman spectroscopy of Li2Ge7O15 single crystals: Spectra of the paraelectric and aristotypephases. J. Phys. Condens. Mater. 1995, 7, 5681–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyushin, G.D.; Dem’yanets, L.N. Crystal chemistry of germanates: Characteristic structural features of Li, Ge-germanates. Crystallogr. Rep. 2000, 45, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsos, E.I.; Yiannopoulos, Y.D.; Karakassides, M.A.; Chryssikos, G.D.; Jain, H. Raman and infrared structural investigation of xRb2O·(l − x)GeO2 glasses. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 11755–11765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, O.N.; Shtenberg, M.V.; Ivanova, T.N. The structure of potassium germanate glasses as revealed by Raman and IR spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 510, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, O.N.; Osipov, A.A. In situ Raman spectroscopy of K2O–GeO2 melts. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 531, 119850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, H.; Buster, J.H.J.M. The structure of lithium, sodium and potassium germanate glasses, studied by Raman scattering. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1979, 34, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.S.; Amos, R.T. The structure of alkali germanophosphate glasses by Raman spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2003, 328, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, O.N.; Shtenberg, M.V.; Bychinskii, V.A. Melts and glasses of the K2O-GeO2 system: Physicochemical modelling with correction based on the results of Raman spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 594, 121795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuwa, C.I.; Mayer, A.; Zednicek, W. Phases in the Na2O–GeO2 System. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1993, 12, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E. Refinement of the structure of sodium enneagermanate (Na4Ge9O20). Acta Cryst. 1990, C46, 1202–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, R.; Heinrich, F. Beiträgezur Chemie des Germaniums: IX. Mitteilung. Über die Germanate der Alkali—und Erdalkalimetalle. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1932, 205, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, E.A.; Li, C.T. Growth of complex oxide single crystals from fluoride melts. J. Amer. Ceram. Soc. 1969, 52, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelchenko, G.A.; Demyanets, L.N.; Lobachev, A.N. Hydrothermal crystal synthesis in the H2O3(Yb2O3)–GeO2–KF–H2O systems. J. Solid State Chem. 1975, 14, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingri, N.; Lundgren, G.; Theander, O.; Brimacombe, J.S.; Cook, M.C. Crystal structure of Na4Ge9O20. Acta Chem. Scand. 1963, 17, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.