Effects of Total Calcium and Iron(II) Concentrations on Heterogeneous Nucleation and Crystal Growth of Struvite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

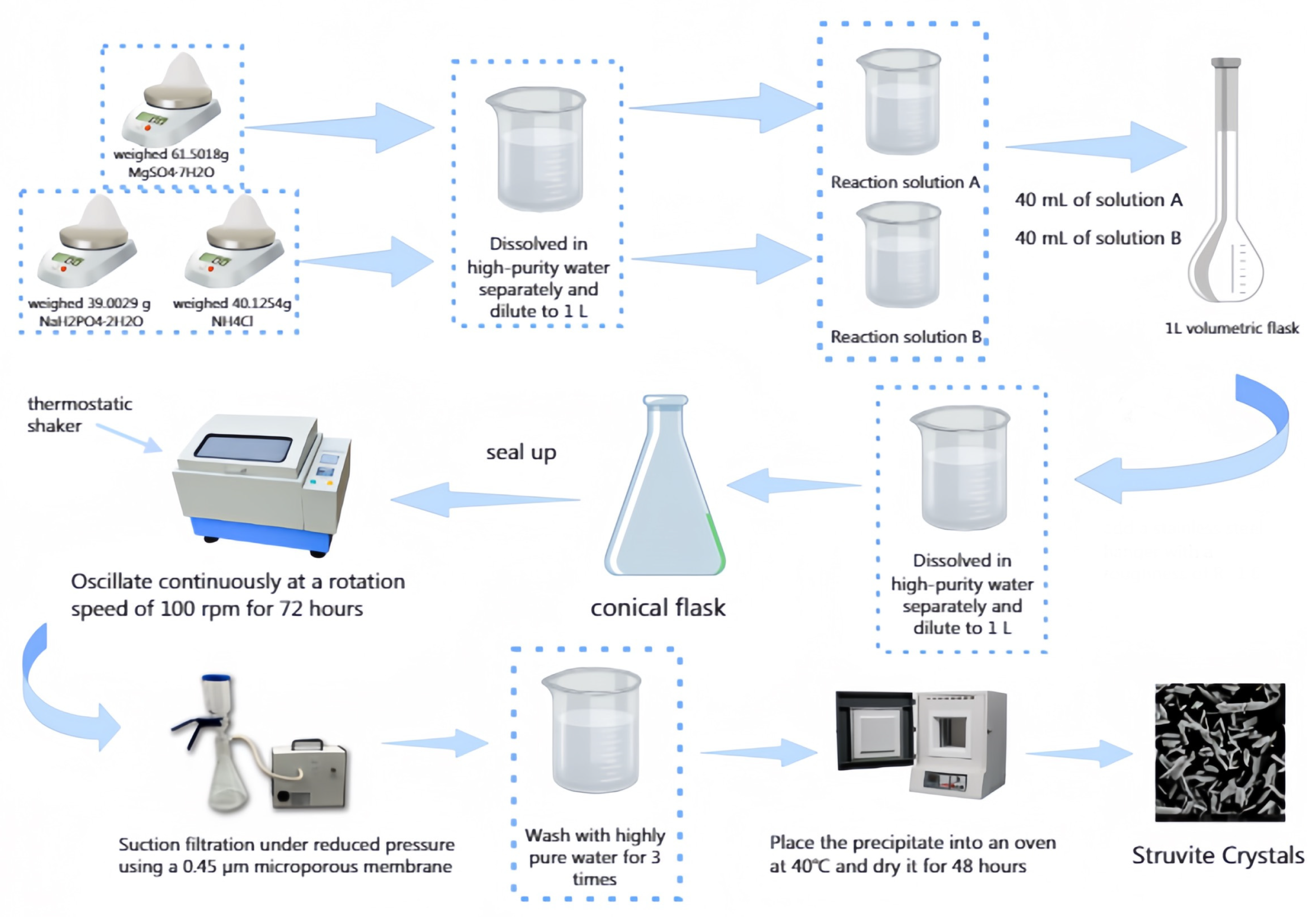

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.3.3. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.5. Real-Time pH Monitoring

2.3.6. Redox Potential (Eh) Monitoring

2.3.7. Kinetic Analysis Based on Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

2.3.8. Thermodynamic Modeling

3. Results

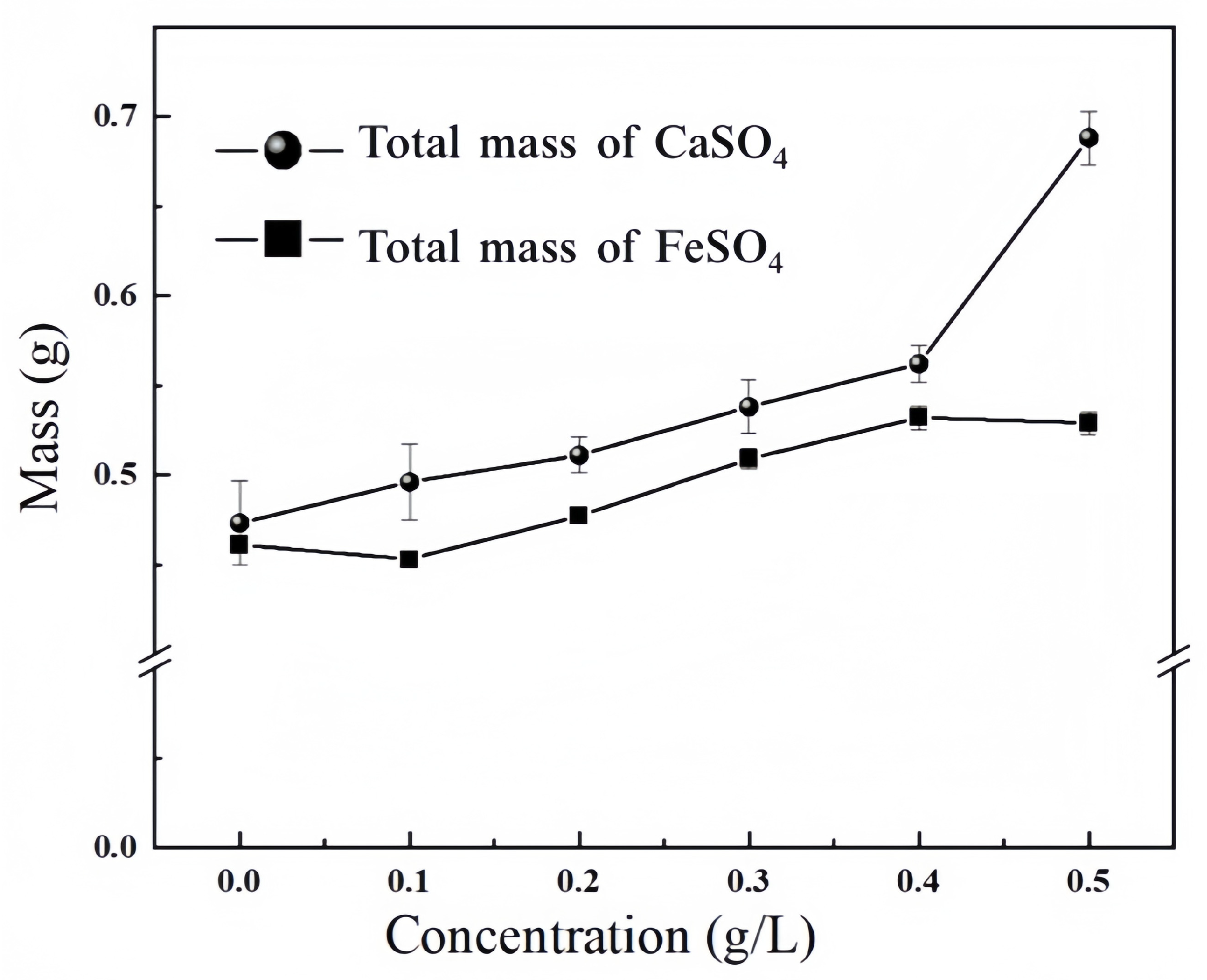

3.1. Precipitation Performance of Struvite Under Ca2+ and Fe2+ Interference

3.2. Multidimensional Characterization of Struvite Precipitates

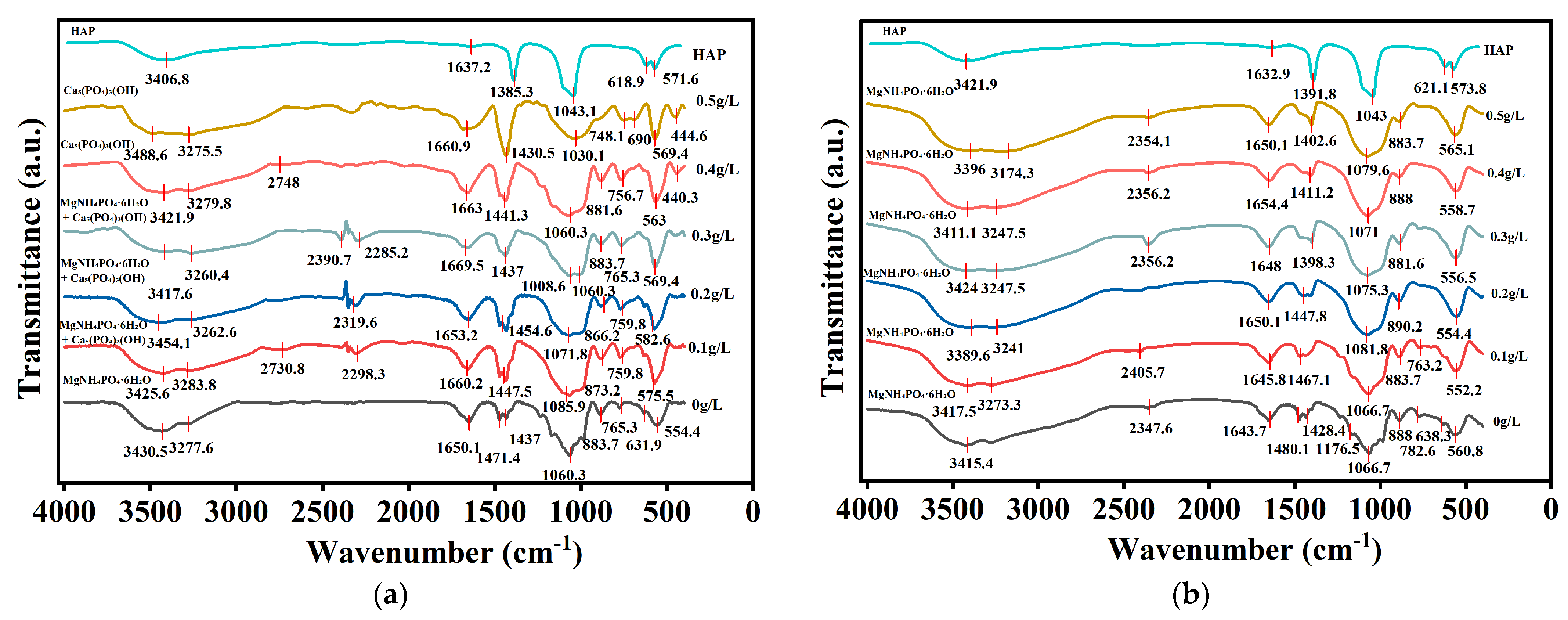

3.2.1. FTIR Spectra of Struvite Precipitates Under Ca2+ and Fe2+ Interference

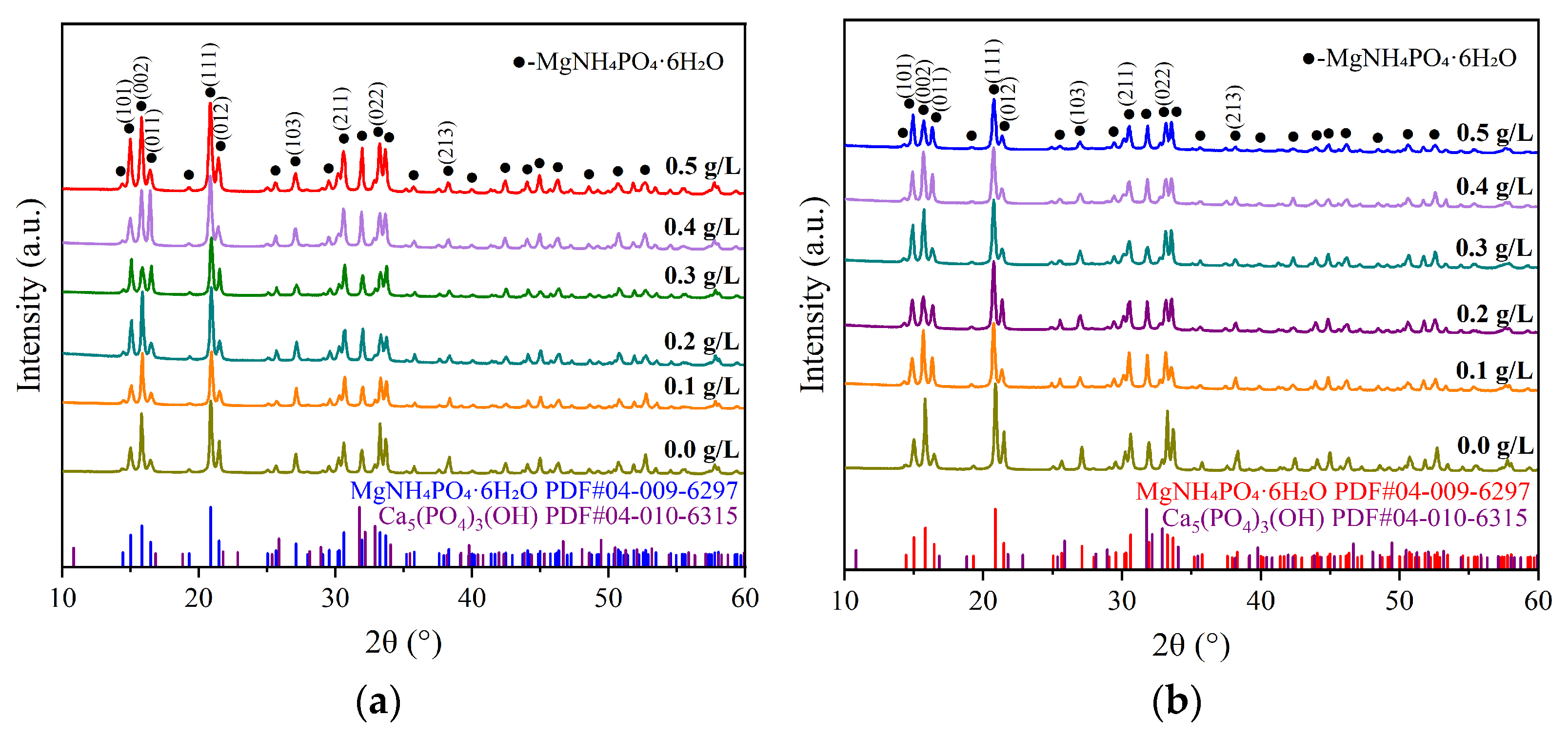

3.2.2. XRD Patterns of Struvite Precipitates Under Ca2+ and Fe2+ Interference

3.2.3. SEM Observation of the Morphological Evolution of Struvite Crystals

3.2.4. XPS Characterization of Surface Element Composition and Chemical State

3.3. Real-Time Monitoring of Solution Chemistry

3.3.1. pH Evolution During Crystallization

3.3.2. Redox Potential (Eh) and Iron Speciation

3.4. Thermodynamic Saturation Index Calculations

4. Discussion

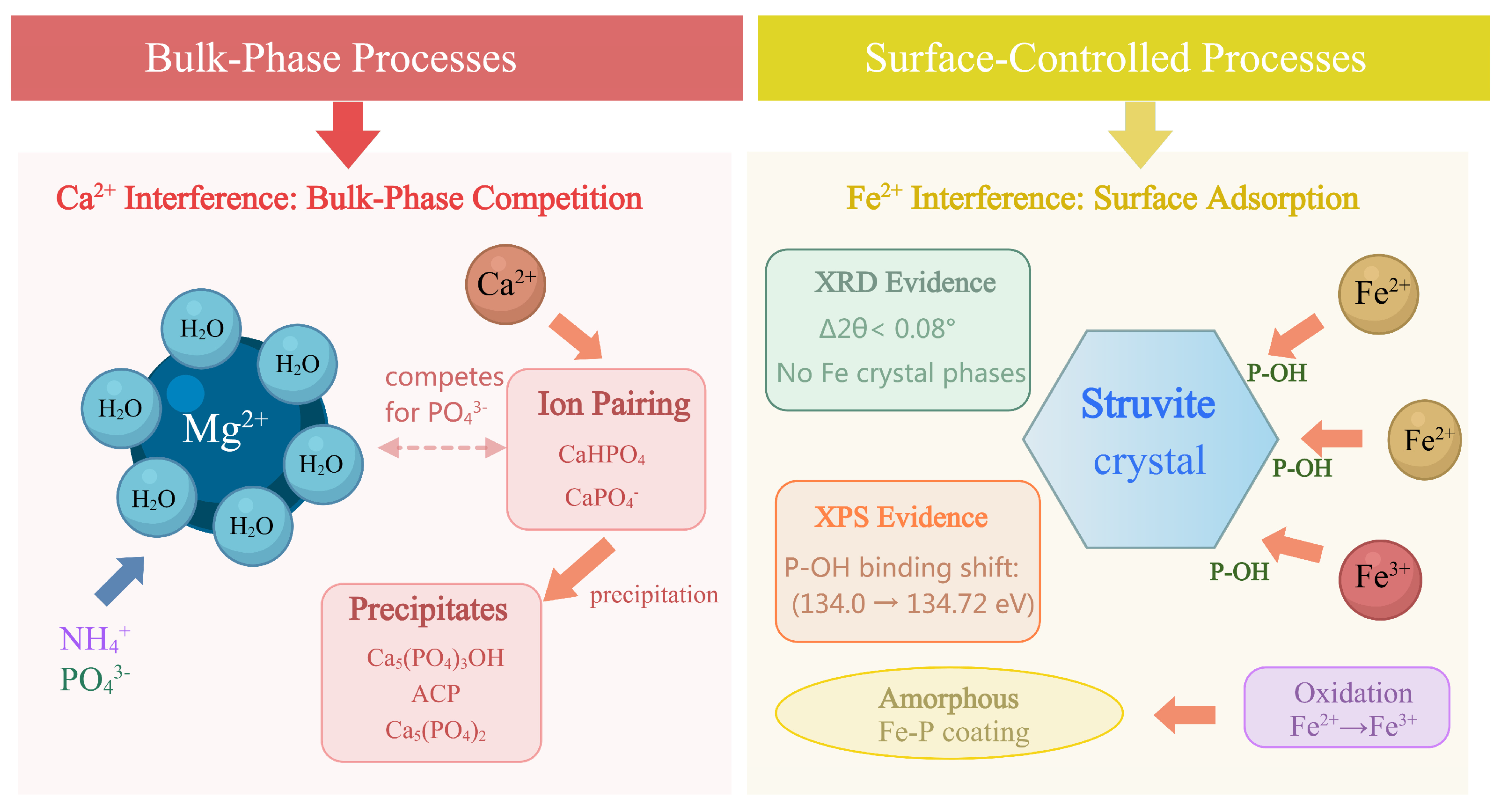

4.1. Influence of Ca2+: Bulk-Phase Competition and Formation of Ca–P Phases

4.2. Influence of Fe2+: Surface Adsorption, Growth Poisoning, and Amorphous Fe–P Layer Formation

4.3. Kinetic Analysis Based on Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

4.4. Comparative Mechanistic Framework: Thermodynamic Limitation Versus Kinetic Inhibition

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Ca2+ and Fe2+ were found to suppress struvite crystallization through qualitatively different pathways. Ca2+ interference was dominated by bulk-phase chemical competition for phosphate and the promotion of Ca-P precipitation routes, which reduces the effective supersaturation available for struvite. In contrast, Fe2+ interference was better explained by surface-mediated processes under reducing conditions, where interfacial coordination/adsorption can impede nucleation and growth even without forming detectable crystalline Fe–P impurities. This distinction indicated that the inhibition is not a single phenomenon but a mechanism-dependent outcome.

- (2)

- Ca2+ inhibition can be generalized as a thermodynamic/supersaturation-limiting mechanism.When Ca2+ increased, phosphate was preferentially diverted into Ca-P pathways, causing a systematic reduction in the struvite driving force. In nucleation terms, this corresponds to a higher nucleation barrier and a larger critical nucleus, which manifested as delayed crystallization, reduced crystallite size, and higher susceptibility to poorly crystalline by-products. Therefore, Ca2+-rich matrices should be viewed as phosphate-availability-limited for struvite formation.

- (3)

- Fe2+ inhibition can be generalized as an interfacial/kinetic mechanism. Under stable anaerobic conditions, Fe2+ remained the dominant dissolved iron species and interact strongly with phosphate-containing moieties at the crystal–solution interface. Such interfacial Fe-O-P coordination was consistent with a growth-site blocking mechanism, in which ordered attachment of struvite growth units becomes less favorable. Consequently, Fe2+-rich reduced matrices may exhibit suppressed struvite crystallization even when bulk thermodynamics alone would haved predicted favorable precipitation.

- (4)

- Process control should be mechanism-specific rather than ion-specific. Because Ca2+ acted mainly through bulk competition, mitigation should focus on restoring struviting supersaturation and reducing Ca-P diversion (e.g., softening, pH/alkalinity management, staged dosing of Mg2+, or controlling phosphate availability). Because Fe2+ acted mainly through interfacial inhibition, control should emphasize surface chemistry and adsorption management (e.g., competitive complexants/ligands, surface passivation approaches, or operational strategies that reduce Fe–phosphate interfacial interactions). Treating both ions with the same mindset may lead to inefficient or unnecessary pretreatment.

- (5)

- A comparative mechanistic framework was found to be essential for complex wastewaters where multiple ions coexist. Real wastewaters often contain Ca2+ and Fe2+ simultaneously, and their combined effects may not be a linear superposition. Bulk competition by Ca2+ may reduce phosphate availability, while surface poisoning by Fe2+ may further hinder nucleation or growth, potentially leading to stronger-than-expected suppression. Future studies should therefore evaluate multi-ion coupling effects and develop predictive models that integrate thermodynamic speciation with interfacial kinetics to enable robust process optimization.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, Y.; Kallikazarou, N.I.; Nisiforou, O.; Shang, Q.; Fu, D.; Antoniou, M.G.; Fotidis, I.A. Phosphorus recovery through struvite crystallization from real wastewater: Bridging gaps from lab to market. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 427, 132408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Ou, R.; Zeng, G. A review of struvite crystallization for nutrient source recovery from wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monballiu, A.; Ghyselbrecht, K.; Crabeels, X.; Meesschaert, B. Calcium phosphate precipitation in nitrified wastewater from the potato-processing industry. Environ. Technol. 2018, 40, 2250–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaja, P.; Murugan, P.; Karthiyayini, C.; Sudha, D.; Sabarishwaran, G.; Sekaran, G. Evaluation of fenton-like oxidation coupled with struvite precipitation for the enhanced treatment of Cu-contaminated ammoniacal nitrogen-rich wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 381, 125204. [Google Scholar]

- Iftikhar, A.; Tao, W. Production of natural fertilizers with sludge digestate by mineral-based struvite crystallization and organic binding. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hasanr, H.; Hamdi, R.; Muhamad, M.H.; Nazairi, N.A. Efficient nitrogen recovery from domestic wastewater through struvite precipitation: Optimizing process parameters and characterization analysis. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallikazarou, N.I.; Nisiforou, O.; Kokkinidou, D.A.; Koutsokeras, L.; Michael, C.; Castro, J.L.; Anayiotos, A.S.; Constantinides, G.; Botsaris, G.; Fotidis, I.A.; et al. Pilot-scale production of high-purity struvite fertilizer from livestock waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127009. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; Chai, L.Y.; Kuroda, K.; Okido, M.; Song, Y.X. New insights into the interaction between heavy metals and struvite: Struvite as platform for heterogeneous nucleation of heavy metal hydroxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 365, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyanto, E.; Ang, H.M.; Sen, T.K. Impact of various physico-chemical parameters on spontaneous nucleation of struvite: Kinetic and nucleation mechanism. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 6620–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J. Impact of calcium on struvite crystallization in the wastewater and its competition with magnesium. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwitasari, D.S.; Muryanto, S.; Schmahl, W.W.; Jamari, J.; Bayuseno, A.P. A kinetic and structural analysis of the effects of Ca- and Fe ions on struvite crystal growth. Solid State Sci. 2022, 134, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyemadze, I.; Momade, F.W.Y.; Oduro-Kwarteng, S.; Essandoh, H. Phosphorus recovery by struvite precipitation: A review of the impact of calcium on struvite quality. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2021, 11, 706. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Da, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Chang, J. Competitive adsorption of heavy metals between Ca-P and Mg-P products from wastewater during struvite crystallization. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yoo, B.H.; Kim, S.K.; Lim, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, T.H. Enhancement of struvite purity by re-dissolution of calcium ions in synthetic wastewaters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 261, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Corre, K.S.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Hobbs, P.; Parsons, S.A. Phosphorus Recovery from Wastewater by Struvite Crystallization: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 39, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Shao, Y.; Chen, F.; Sun, M.; Liu, B. Effects of physicochemical parameters on struvite crystallization based on kinetics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7204. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, C.T.; Huang, T.H.; Lacson, C.F.Z.; Vilando, A.C.; Lu, M.C. Recovering struvite from livestock wastewater by fluidized-bed homogeneous crystallization. Environ. Res. 2023, 235, 116639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, M.; Santoro, S.; Di Profio, G.; La Russa, M.F.; Limonti, C.; Straface, S.; D’Andrea, G.; Curcio, E.; Siciliano, A. Membrane distillation for separation and recovery of valuable compounds from anaerobic digestates. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 315, 123687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ye, Z.L.; Ye, C.; Ye, X.; Chen, S. Struvite crystallization induced the discrepant transports of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, V.; Fuentes, B.; Gómez, G.; Vidal, G. Struvite precipitation in wastewater treatment plants anaerobic digestion supernatants. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164607. [Google Scholar]

- Muhmood, A.; Lu, J.; Maqsood, A.; Chishti, M.Z.; Liu, H.; Dong, R.; Makinia, J.; Wu, S. Struvite precipitation within wastewater treatment: A problem or a circular economy opportunity? Heliyon 2022, 8, e08911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Salleh, M.A.M.; Rashid, U.; Ahsan, A.; Hossain, M.M.; Ra, C.S. Production of slow release crystal fertilizer from wastewaters through struvite crystallization—A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2014, 7, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaddel, S.; Bakhtiary-Davijany, H.; Kabbe, C.; Dadgar, F.; Østerhus, S.W. Sustainable sewage sludge management: From current practices to emerging nutrient recovery technologies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.-D.; Wang, C.-C.; Lan, L.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Struvite formation, analytical methods and effects of pH and Ca2+. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 58, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, S.B.; Tlili, M.M.; Batis, N.; Amor, M.B. Influence of temperature on Struvite precipitation by CO2-degassing method. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2011, 46, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Tansel, B.; Lunn, G.; Monje, O. Struvite formation and decomposition characteristics for ammonia and phosphorus recovery: A review of magnesium-ammonia-phosphate interactions. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, N.; Unpaprom, Y.; Ramaraj, R.; Maniam, G.P.; Govindan, N.; Arunachalam, T.; Paramasivan, B. Recent advances and future prospects of electrochemical processes for microalgae harvesting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, A.; Limonti, C.; Curcio, G.M.; Molinari, R. Advances in struvite precipitation technologies for nutrients removal and recovery from aqueous waste and wastewater. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Guo, G.; Tang, S. Phosphate recovery from swine wastewater using plant ash in chemical crystallization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaddel, S.; Ucar, S.; Andreassen, J.P.; Østerhus, S.W. Engineering of struvite crystals by regulating supersaturation—Correlation with phosphorus recovery, crystal morphology and process efficiency. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102918. [Google Scholar]

- Fidaleo, M.; Ferraris, S.; Ferraris, S.; Ferraris, R. Crystallization of struvite from aqueous solutions: Thermodynamics and kinetics analysis. J. Cryst. Growth 2023, 615, 127234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, B.; Su, T.; Wu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, T.-Y. Crystallographic phase identifier of a convolutional self-attention neural network (CPICANN) on powder diffraction patterns. IUCrJ 2024, 11, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, Y.J.; Ruffel, R.; de Luna, M.D.G.; Huang, Y.H.; Lu, M.C. Simulated solar light induced photocatalytic degradation of acetaminophen by struvite-BiVO4 composites. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106166. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Chiu, H.-C.; Rasool, M.; Brodusch, N.; Gauvin, R.; Jiang, D.-T.; Ryan, D.H.; Zaghib, K.; Demopoulos, G.P. Hydrothermal crystallization of Pmn21 Li2FeSiO4 hollow mesocrystals for Li-ion cathode application. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 359, 1592–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, M.; Donnadio, A.; Costantino, F.; Vivani, R.; Casciola, M. Synthesis, crystal structure, and proton conductivity of one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional zirconium phosphonates. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12131–12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczynski, G.; Hultman, L. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Towards reliable binding energy referencing. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 107, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raii, M.; Dietrich, E.; Kessler, V.G.; Seisenbaeva, G.A. Surface chemistry and electrochemical properties of struvite-K for battery applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7954–7962. [Google Scholar]

- Paskin, A.; Couasnon, T.; Pérez, J.P.H.; Lobeck, H.L.; Alwmark, S.; Horlitz, A.; Zeiger, M.; Pure, M.; Marshak, R.; Benning, L.G. Nucleation and crystallization of ferrous phosphate hydrate via an amorphous intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15137–15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, J.J.; Zhou, B.; Awasthi, M.K.; Ali, A.; Zhang, Z.; Gaston, L.A.; Lahori, A.H.; Mahar, A. Enhancing phosphate adsorption by Mg/Al layered double hydroxide functionalized biochar with different Mg/Al ratios. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Prywer, J.; Torzewska, A.; Płociński, T. Unique surface and internal structure of struvite crystals formed by Proteus mirabilis. Urol. Res. 2012, 40, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.D.; Wang, C.C.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Hu, Y.S. Looking beyond struvite for P-recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4965–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, D.J.; Elektorowicz, M.; Oleszkiewicz, J.A. Struvite precipitation and phosphorus removal using magnesium sacrificial anode. Chemosphere 2014, 101, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Ye, Z.L.; Lou, Y.; Pan, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.K.; Chen, S. A comprehensive understanding of saturation index and upflow velocity in a pilot-scale fluidized bed reactor for struvite recovery from swine wastewater. Powder Technol. 2016, 295, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfert, P.; Dugulan, A.I.; Goubitz, K.; Korber, L.; Witkamp, G.J.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Vivianite as the main phosphate mineral in digested sewage sludge and its role for phosphate recovery. Water Res. 2018, 144, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothe, M.; Kleeberg, A.; Zippel, B.; Zak, D. Sedimentary sulphur:iron ratio indicates vivianite occurrence: A study from two contrasting freshwater systems. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143737. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoukos, P.G.; Valsami-Jones, E. Principles and applications of controlled nucleation and growth of calcium phosphates from aqueous solutions. In Biomineralization and Biomaterials; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2016; pp. 103–135. [Google Scholar]

- Habraken, W.J.E.M.; Masic, A.; Bertinetti, L.; Al-Sawalmih, A.; Glazer, L.; Bentov, S.; Fratzl, P.; Sagi, A.; Aichmayer, B.; Berman, A. Layered growth of crayfish gastrolith: About the stability of amorphous calcium carbonate and role of additives. J. Struct. Biol. 2015, 189, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y. Heterogeneous nucleation or homogeneous nucleation? J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 9949–9955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhoun, M.; Montastruc, L.; Azzaro-Pantel, C.; Biscans, B.; Frèche, M.; Pibouleau, L. Temperature impact assessment on struvite solubility product: A thermodynamic modeling approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 167, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3: A computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. In Techniques and Methods; Book 6, Chapter A43; U.S. Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crutchik, D.; Garrido, J.M. Struvite crystallization versus amorphous magnesium and calcium phosphate precipitation during the treatment of a saline industrial wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 64, 2460–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlinger, K.N.; Young, T.M.; Schroeder, E.D. Predicting struvite formation in digestion. Water Res. 1998, 32, 3607–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Pan, Y.; Yin, C.; Du, C.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H. Proton-self-doped PANI@CC as the cathode for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 650, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Chaudhary, P.; Singh, A.; Tripathi, R.K.; Yadav, B.C. ZnS Nanosheets in a Polyaniline Matrix as Metallopolymer Nanohybrids for Flexible and Biofriendly Photodetectors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 4860–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Feng, J.; Sun, F. Efficient Simultaneous Adsorption of Phosphate and Ammonia Nitrogen by Magnesium-Modified Biochar Beads and Their Recovery Performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110875. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, T.; Huang, J.; Chen, M.; Hu, H.; Peng, L.; Wu, L.; Chaocheng, Z.; Zhang, Q. Efficient incorporation of highly migratory thallium into struvite structure: Unraveling the stabilization mechanisms from a mineralogical perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Guo, N.; Yan, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, L.; Chi, X.; Zhao, H.; et al. Recovery of phosphate, magnesium and ammonium from eutrophic water by struvite biomineralization through free and immobilized Bacillus cereus MRR2. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Z.; Shen, Q.; Hou, X.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, C.; Xu, D. Optimized preparation, characterization and the adsorption mechanism of magnesium-modified bentonite-based porous adsorbents: Thermodynamic and kinetic analysis. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 4982. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, A.H.; Guo, F.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Ying, G.; Zhang, J. Concurrent removal of phosphate and ammonium from wastewater for utilization using Mg-doped biochar/bentonite composite beads. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 285, 120399. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, R.; Hao, L.; Sun, W. Effects of calcium on phosphorus recovery from wastewater by vivianite crystallization: Interaction and mechanism analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Sun, Y.; Tian, H.; Zhan, W.; Du, Y.; Ye, H.; Du, D.; Zhang, T.C.; Hou, H. Electrolytic manganese residue-based cement for manganese ore pit backfilling: Performance and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 124941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-H.; Wang, Y.; Hua, L.; Fan, M.-Y.; Ren, X.-H.; Zhang, L. Mg-Fe bimetallic oxide nanocomposite for superior phosphate removal and recovery from aquatic environment: Synergistic effects of sorption and struvite crystallization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Xie, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; He, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Enhancing concurrent production of volatile fatty acids and phosphorus minerals from waste activated sludge via magnesium ferrate pre-oxidation. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 421, 132156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, X.; Ni, B.; Chen, X.; Xie, F.; Guo, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, W.; Yue, X.; Zhou, A. Synchronous vivianite and hydrogen recovery from waste activated sludge fermentation liquid via electro-fermentation mediated by iron anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, M.; Wang, L.; Feng, J. Phosphate recovery from wastewater via vivianite crystallization using separable ferrous modified biochar beads. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jing, X.; Li, Z.; Xing, Y.; Li, B. Valorization of vanadium industry waste into calcium-rich hydroxyapatite for ultrahigh-capacity lead remediation: A multimechanistic approach to lead sequestration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169433. [Google Scholar]

| Crystal Face | Control | 0.1 g/L | 0.2 g/L | 0.3 g/L | 0.4 g/L | 0.5 g/L | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Fe | Ca | Fe | Ca | Fe | Ca | Fe | Ca | Fe | ||

| (101) | 15.00 | 15.06 | 14.86 | 15.08 | 14.88 | 15.06 | 14.92 | 14.98 | 14.90 | 14.98 | 14.92 |

| (002) | 15.80 | 15.86 | 15.68 | 15.86 | 15.68 | 15.86 | 15.72 | 15.80 | 15.68 | 15.78 | 15.70 |

| (111) | 20.86 | 20.92 | 20.74 | 20.90 | 20.74 | 20.92 | 20.74 | 20.84 | 20.74 | 20.86 | 20.76 |

| (211) | 30.62 | 30.68 | 30.50 | 30.68 | 30.52 | 30.68 | 30.50 | 30.58 | 30.52 | 30.60 | 30.52 |

| (022) | 33.26 | 33.30 | 33.14 | 33.32 | 33.16 | 33.30 | 33.14 | 33.26 | 33.16 | 33.24 | 33.16 |

| Time (min) | pH | Eh (mV vs. SHE) | Fe2+ (mM) | Fe3+ (mM) | Fe2+ Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9.20 | −185 ± 5 | 5.36 | <0.01 | >99.9 |

| 5 | 8.80 | −175 ± 8 | 4.65 | <0.01 | >99.9 |

| 15 | 8.52 | −160 ± 6 | 3.82 | <0.01 | >99.9 |

| 30 | 8.35 | −145 ± 5 | 2.95 | <0.01 | >99.9 |

| 60 | 8.18 | −130 ± 5 | 2.15 | <0.01 | >99.9 |

| 120 | 8.05 | −115 ± 5 | 1.45 | <0.01 | >99.9 |

| Condition | SI (Struvite) | SI (Vivianite) | SI (Hydroxyapatite) | SI (Fe(OH)3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control, pH 8.5 | 1.85 ± 0.08 | - | 2.12 ± 0.15 | - |

| 0.1 g/L Fe, pH 8.5 | 1.72 ± 0.09 | 3.45 ± 0.12 | 2.08 ± 0.14 | 5.82 ± 0.20 |

| 0.2 g/L Fe, pH 8.5 | 1.65 ± 0.09 | 3.85 ± 0.14 | 2.02 ± 0.15 | 6.15 ± 0.21 |

| 0.3 g/L Fe, pH 8.5 | 1.58 ± 0.10 | 4.21 ± 0.15 | 1.95 ± 0.16 | 6.45 ± 0.22 |

| 0.4 g/L Fe, pH 8.5 | 1.52 ± 0.11 | 4.45 ± 0.16 | 1.88 ± 0.17 | 6.68 ± 0.24 |

| 0.5 g/L Fe, pH 8.5 | 1.45 ± 0.12 | 4.68 ± 0.18 | 1.82 ± 0.18 | 6.89 ± 0.25 |

| Condition | SI (Struvite) | SI (Hydroxyapatite) | SI (ACP) | SI (Brushite) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control, pH 8.5 | 1.85 ± 0.08 | 2.12 ± 0.15 | −0.45 ± 0.10 | −1.25 ± 0.12 |

| 0.1 g/L Ca, pH 8.5 | 1.68 ± 0.08 | 3.85 ± 0.20 | 0.82 ± 0.12 | −0.58 ± 0.10 |

| 0.2 g/L Ca, pH 8.5 | 1.60 ± 0.09 | 4.18 ± 0.21 | 1.15 ± 0.13 | −0.32 ± 0.11 |

| 0.3 g/L Ca, pH 8.5 | 1.52 ± 0.10 | 4.52 ± 0.22 | 1.48 ± 0.14 | −0.05 ± 0.11 |

| 0.4 g/L Ca, pH 8.5 | 1.45 ± 0.10 | 4.85 ± 0.24 | 1.78 ± 0.15 | 0.18 ± 0.12 |

| 0.5 g/L Ca, pH 8.5 | 1.38 ± 0.11 | 5.15 ± 0.25 | 2.05 ± 0.16 | 0.42 ± 0.13 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Control Group (0 g/L) | Ca2+ Functional Group (0.5 g/L) | Fe2+ Functional Group (0.3 g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supersaturation | S | - | 8.54 | 4.12 | 8.30 |

| Interfacial tension | σ | mJ/m2 | 60.00 | 62.5 | 85.00 |

| Critical nuclear radius | r* | nm | 0.85 | 1.62 | 1.48 |

| Gibbs free energy barrier | ΔG | ×10−19 J | 1.82 | 8.45 | 6.88 |

| Critical Growth Unit | n* | - | 15.00 | 45.00 | 32.00 |

| Characteristic | Ca2+ | Fe2+ |

|---|---|---|

| Primary mechanism | Bulk-phase competition | Surface-controlled inhibition |

| Mode of action | Phosphate sequestration into Ca-P phases | Adsorption onto crystal surfaces |

| Effect on supersaturation (S) | Significant reduction (↓ 47%) | Minimal change |

| Effect on interfacial tension (σ) | Slight increase | Significant increase (↑ 42%) |

| Secondary phases | Amorphous/crystalline Ca-P | Amorphous Fe-P surface layer |

| pH response | Gradual, sustained acidification | Rapid initial pH drop |

| Mitigation strategy | Mg:Ca ratio adjustment; Ca pre-precipitation | Surface-active additives; redox control |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, P.; Deng, K.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Hui, F.; Wang, D.; Dong, K. Effects of Total Calcium and Iron(II) Concentrations on Heterogeneous Nucleation and Crystal Growth of Struvite. Crystals 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020080

Wei P, Deng K, Huang Y, Yang J, Hui F, Wang D, Dong K. Effects of Total Calcium and Iron(II) Concentrations on Heterogeneous Nucleation and Crystal Growth of Struvite. Crystals. 2026; 16(2):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020080

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Pengcheng, Kaiyu Deng, Yang Huang, Jiayu Yang, Fujiang Hui, Dunqiu Wang, and Kun Dong. 2026. "Effects of Total Calcium and Iron(II) Concentrations on Heterogeneous Nucleation and Crystal Growth of Struvite" Crystals 16, no. 2: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020080

APA StyleWei, P., Deng, K., Huang, Y., Yang, J., Hui, F., Wang, D., & Dong, K. (2026). Effects of Total Calcium and Iron(II) Concentrations on Heterogeneous Nucleation and Crystal Growth of Struvite. Crystals, 16(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020080