Research on the Influence of Different Aging Temperatures on the Microstructure and Properties of GH2787 Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

3. Results

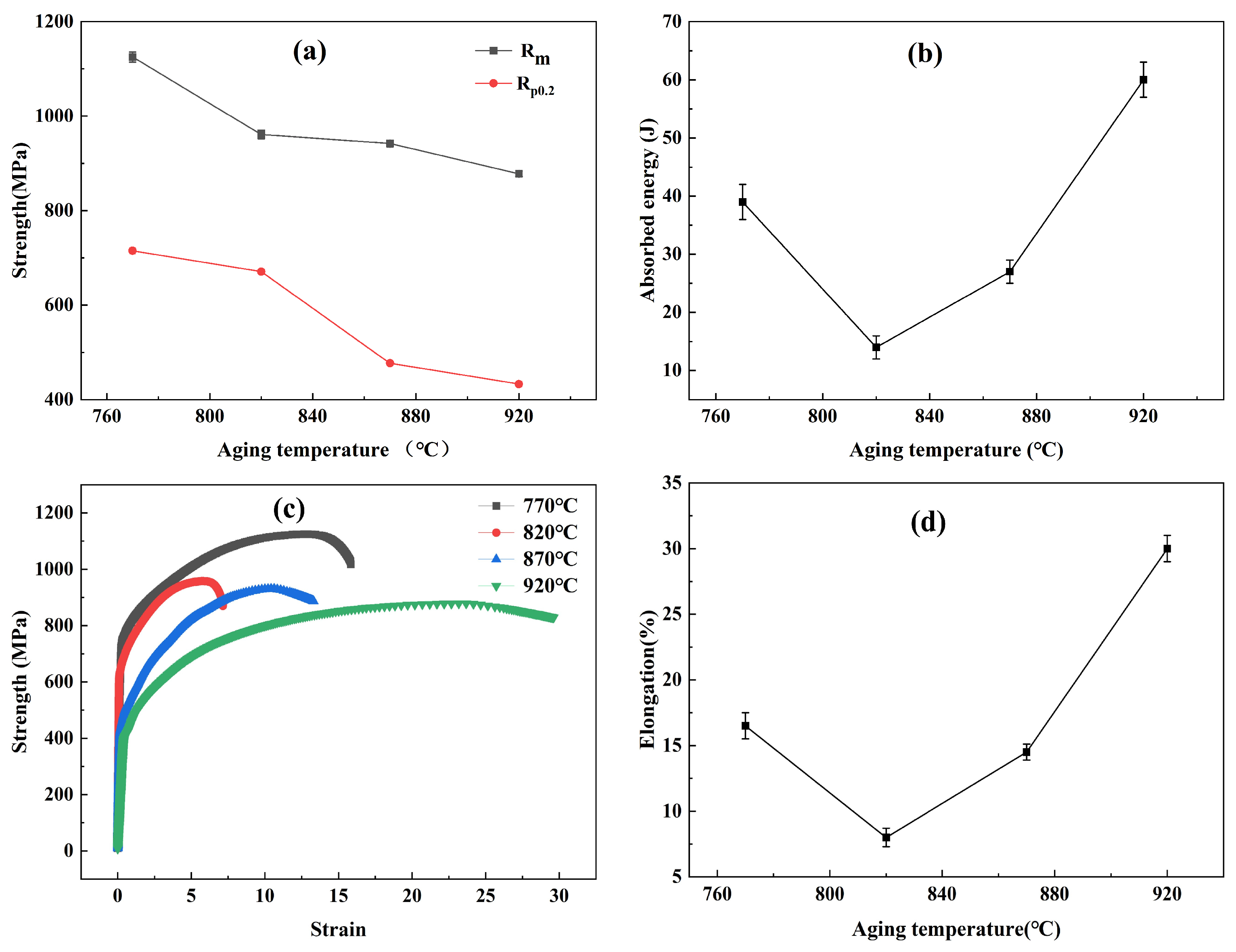

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.2. Microstructure

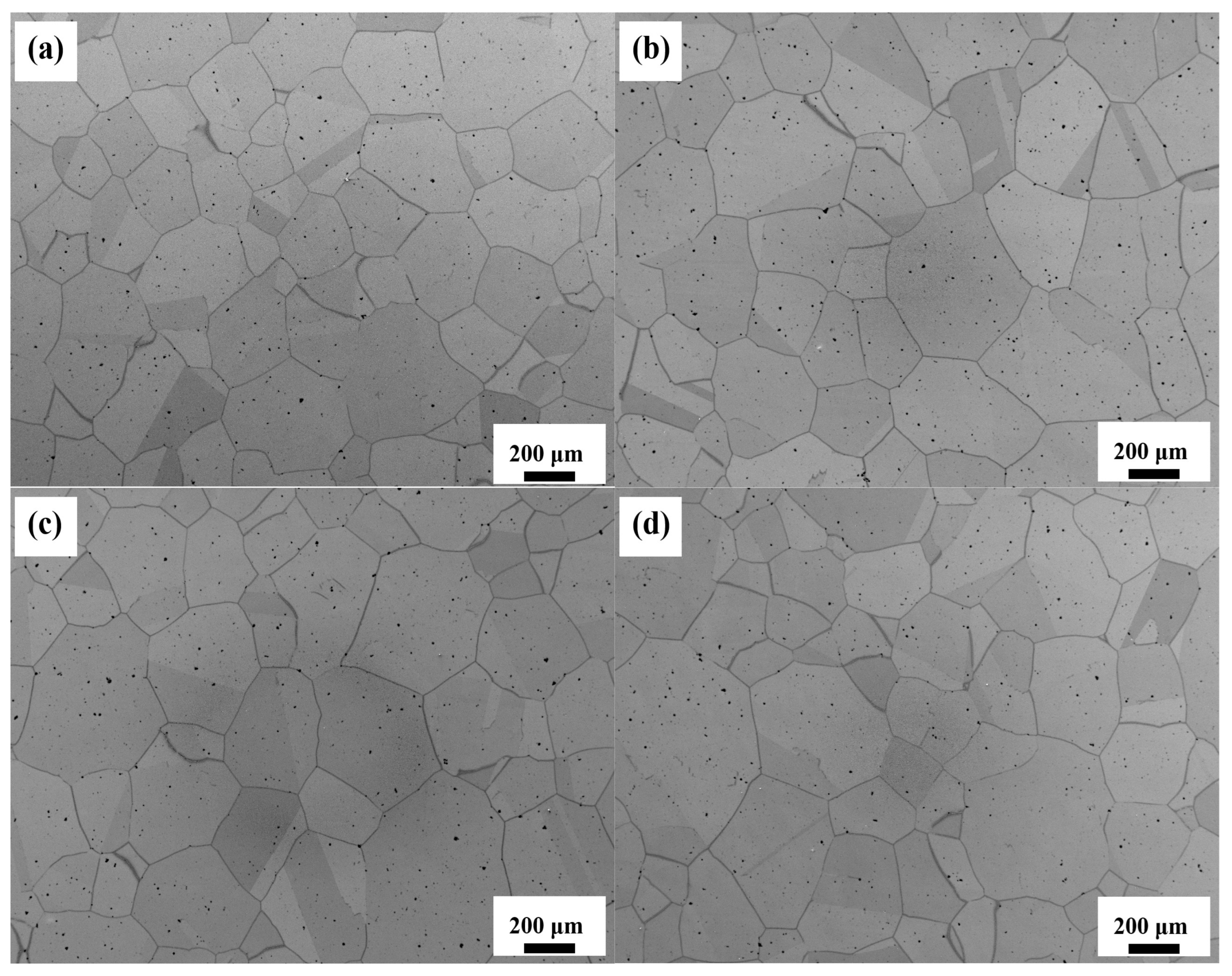

3.2.1. Prior Austenite Grain

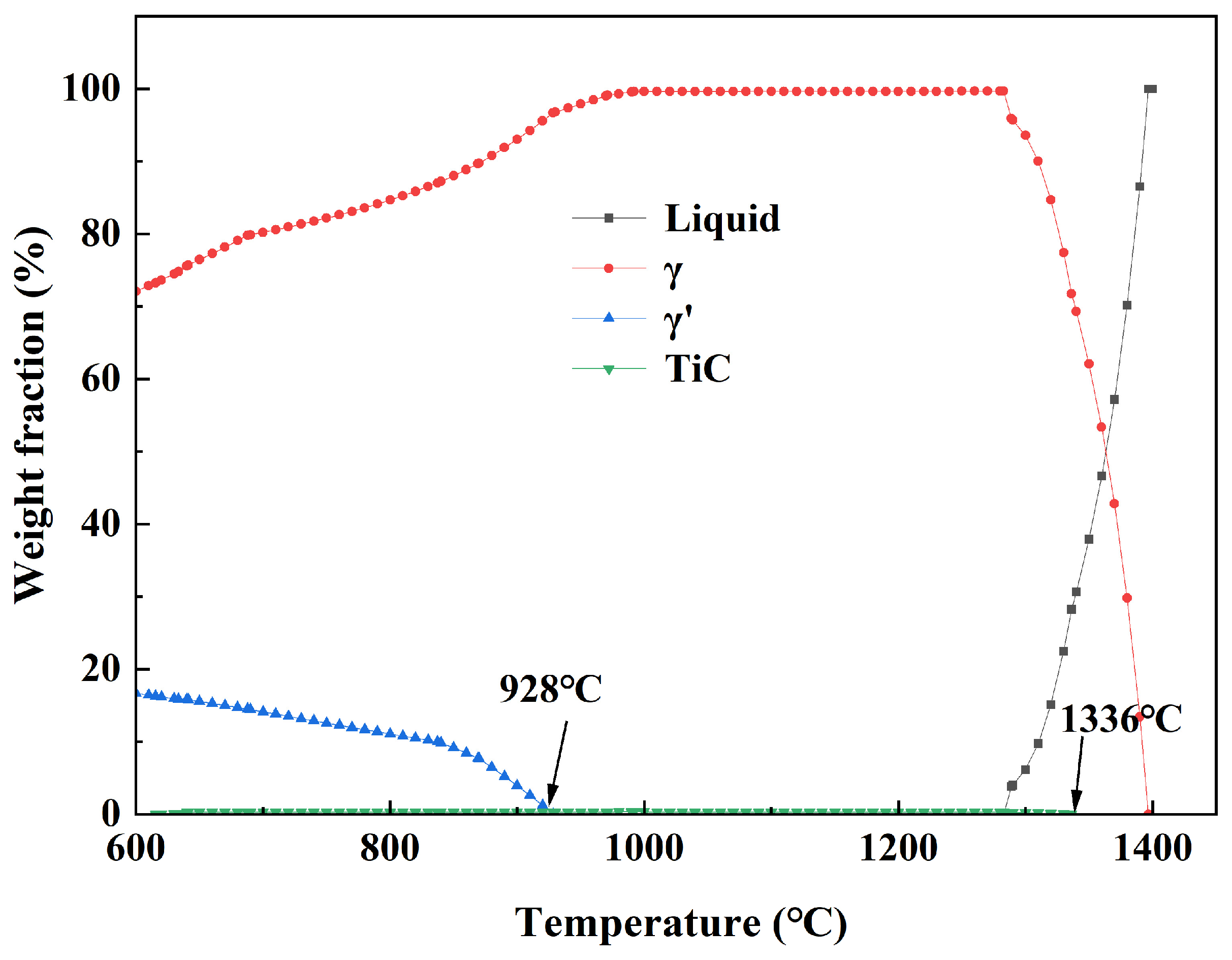

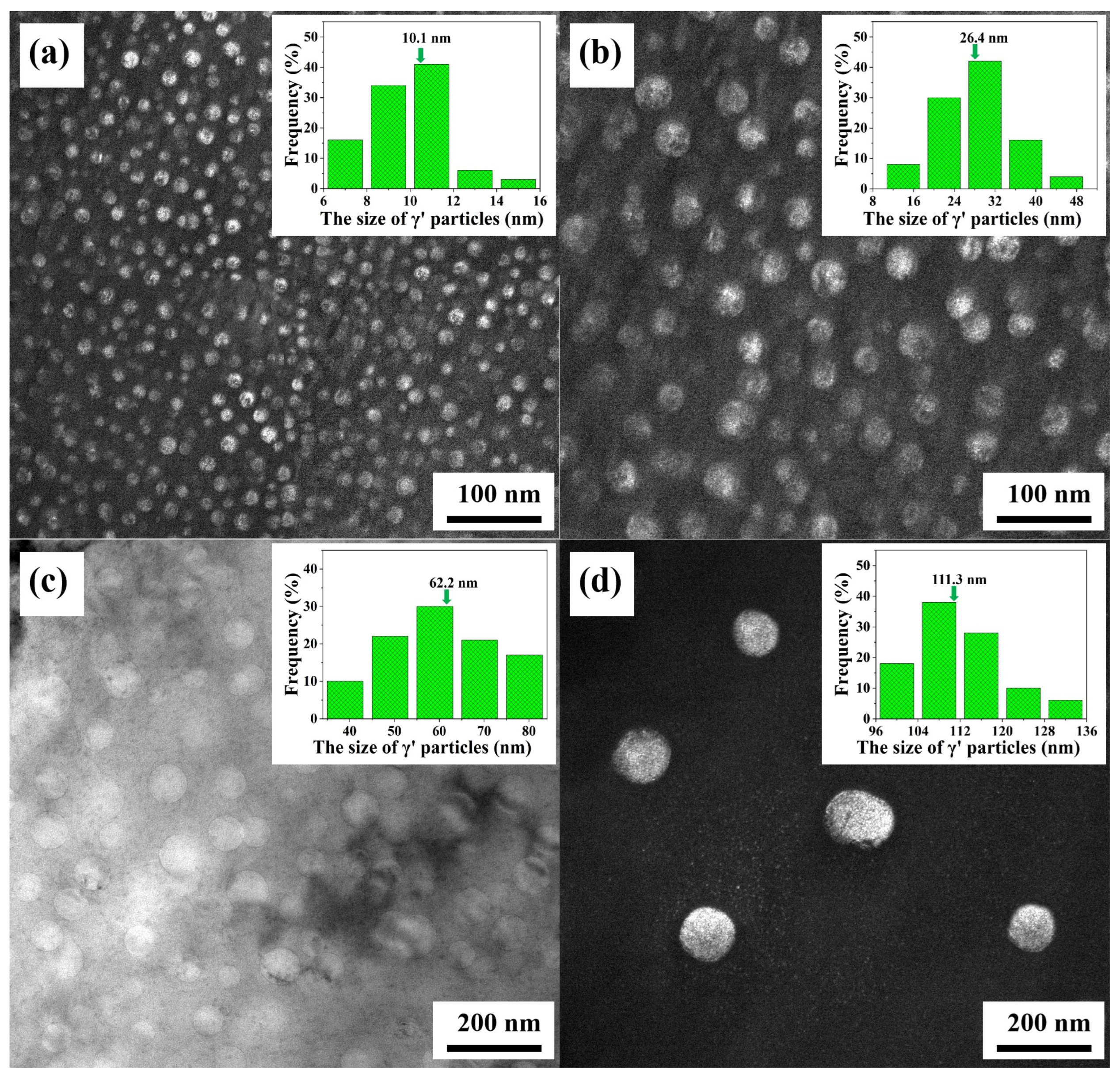

3.2.2. Precipitates

3.2.3. Interaction of Dislocations and Precipitates

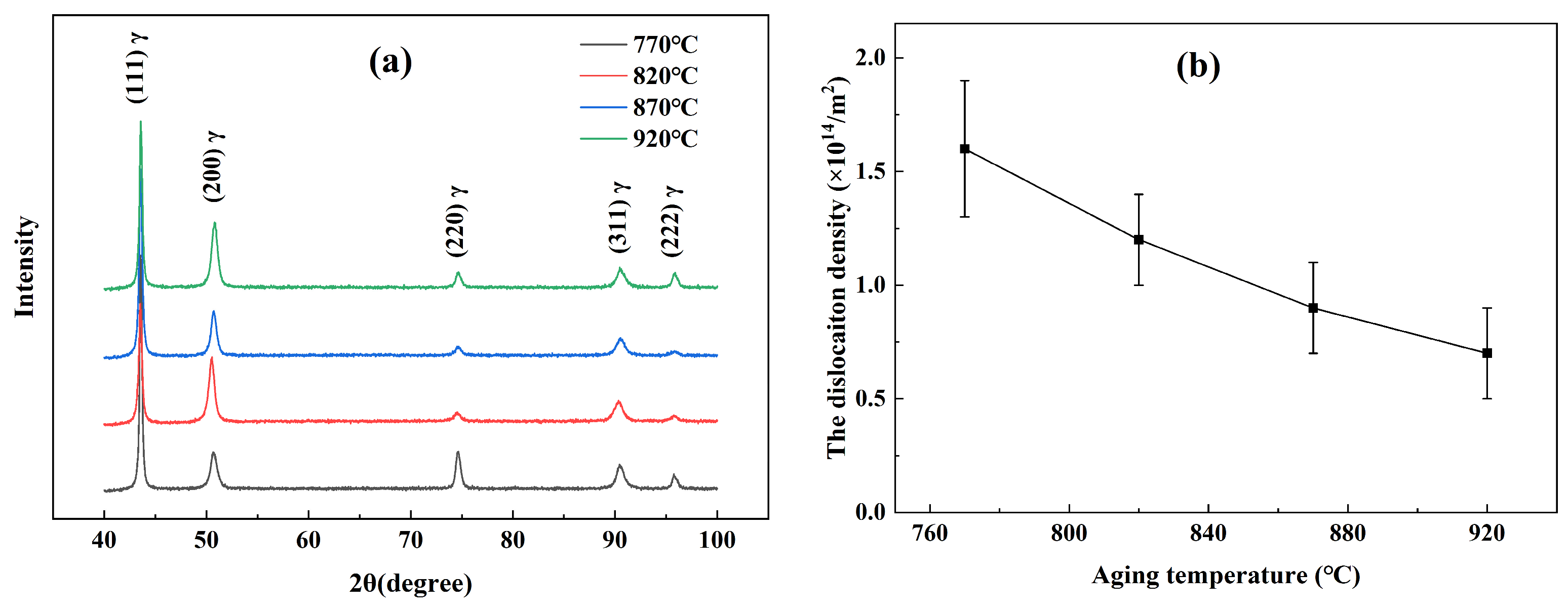

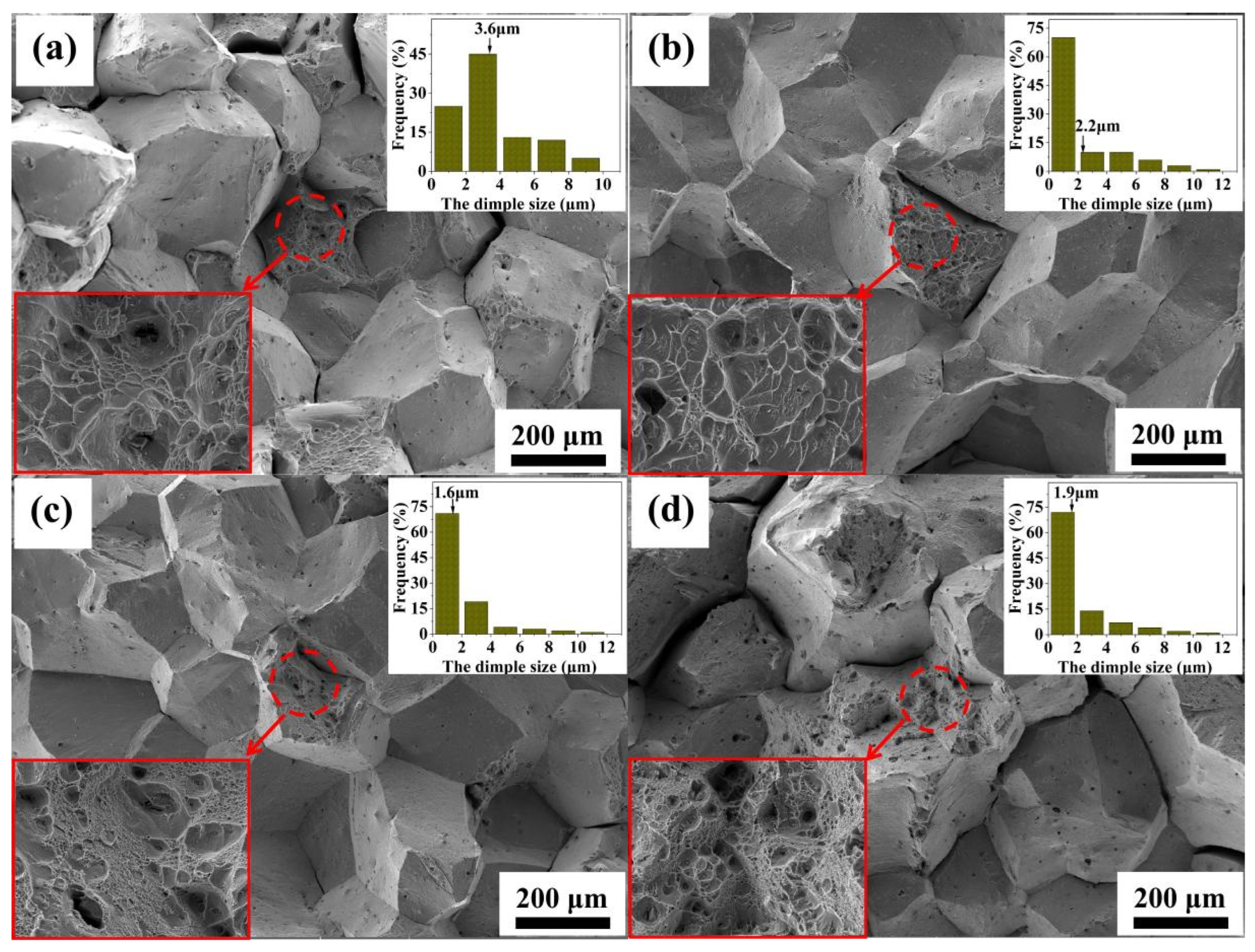

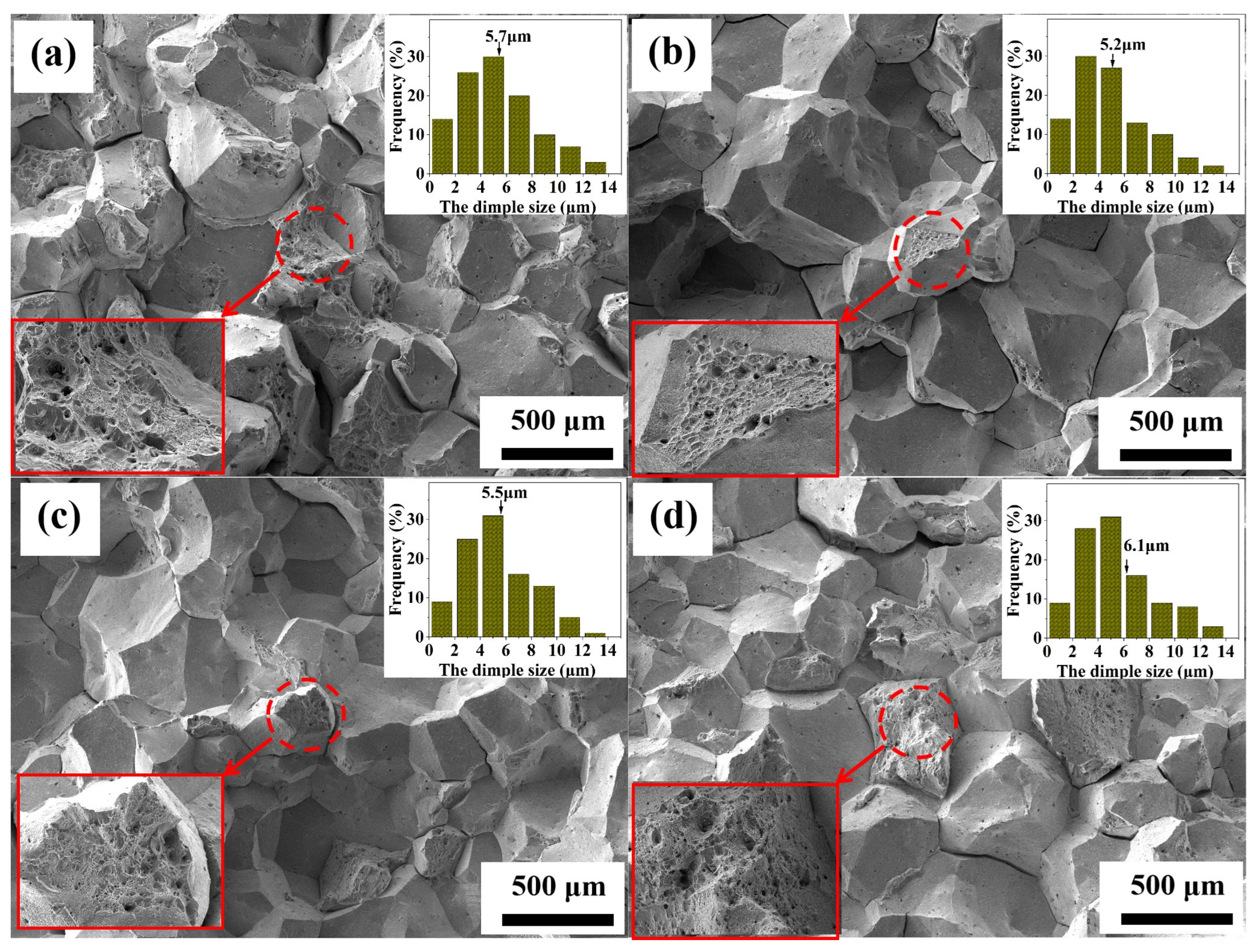

3.3. Fracture Morphology

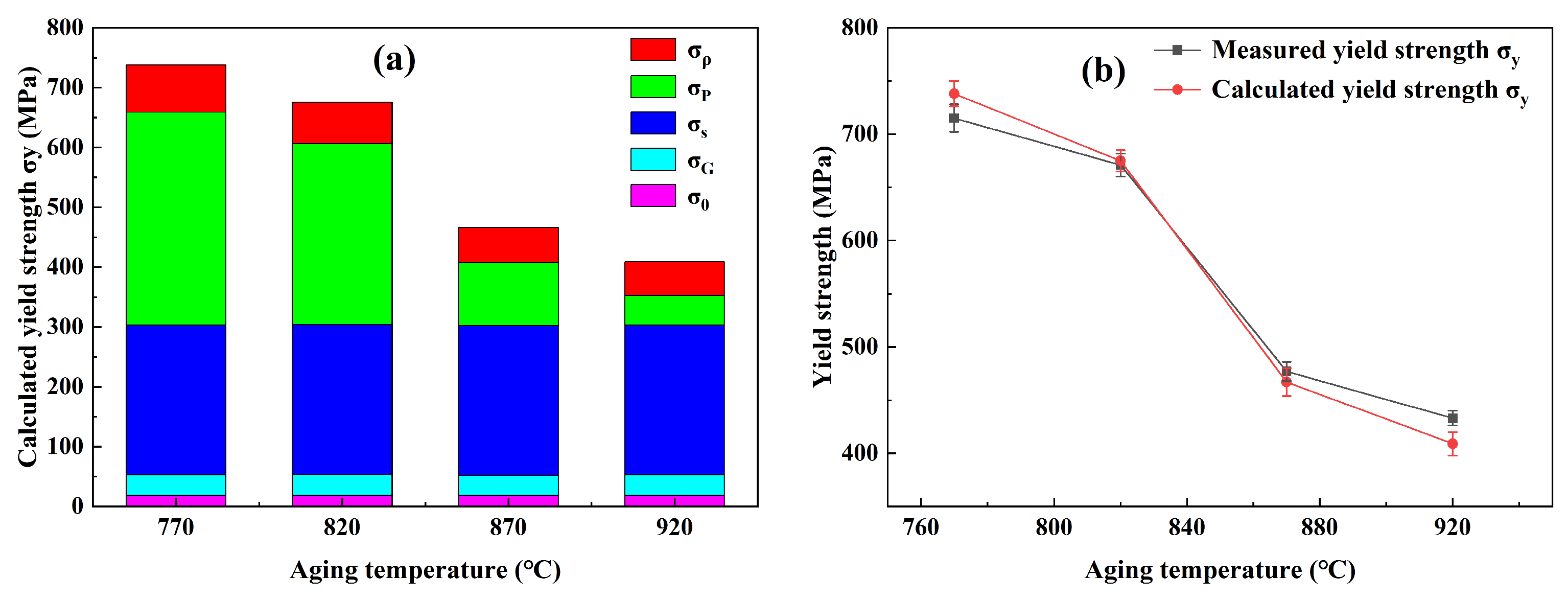

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheng, M.; Sheng, R. High temperature creep properties of directionally solidified CM-247LC Ni-based superalloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 655, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, M. Particle size dependence of the microsegregation and microstructure in the atomized Ni-based superalloy powders: Theoretical and experimental study. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 171, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.P.; Gao, Y.T. Synergistic evolution of MC/M23C6 carbides in a polycrystalline Ni-based superalloy during long-term aging: Elemental diffusion and interaction mechanisms. Mater. Charact. 2025, 229, 115462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, F.W.C.; Duarte, V.R. High-performance Ni-based superalloy 718 fabricated via arc plasma directed energy deposition: Effect of post-deposition heat treatments on microstructure and mechanical properties. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 88, 104252. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Pavan, A.H.V. Role of threshold stress in creep of IN740H, a γ′-lean Ni-based superalloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 903, 146667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Xu, X. Effect of Diamond Rotary Rolling Treatment on Surface Property and Fatigue Life of GH2787 Superalloy. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qi, L.; Zhang, L.; Cui, Z.; Shang, Y.; Qi, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Nadimpalli, V.K.; Huang, L. Microstructural evolution of nickel-based single crystal superalloy fabricated by directed energy deposition during heat treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 904, 163943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattré, A.; Devincre, B.; Roos, A. Orientation dependence of plastic deformation in nickel-based single crystal superalloys: Discrete-continuous model simulations. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Chang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Loge, R.E.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, X.; Huang, K. Deformation mechanisms of primary γ′ precipitates in nickel-based superalloy. Scr. Mater. 2023, 224, 115109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, N.; Li, F.; Wu, G.; Li, F.; Yang, L. The influence of heat treatment procedures on the endurance properties and longitudinal low-microstructure of GH2787 alloy. J. Iron Steel Res. 2011, 23, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y. Study on grain evolution law of GH2787 alloy blade forgings. Hot Work. Technol. 2022, 51, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Ning, L.K.; Xin, T.Z.; Zheng, Z. Coarsening behavior of gamma prime precipitates in a nickel based single crystal superalloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Babu, R.P.; Slater, T.; Mitchell, R.; Ciuca, O.; Preuss, M. On the diffusion-mediated cyclic coarsening and reversal coarsening in an advanced Ni-based superalloy. In Phase Transformations in Multicomponent Melts; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; pp. 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.F.; Yang, G.X.; Fu, Y.H.; Ming, C.; Xie, Y.Q.; Zhuang, J.; Ning, X.J. Solute diffusion in the γ′ phase of Ni based alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2010, 47, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, J.; Zheng, M.; Lu, Q.; Chen, W.; Wei, X.; Song, B. Atomic-scale insights into the frictional wear behaviour of nickel-based single-crystal high-temperature alloys in the γ/Laves phase. Mol. Simul. 2025, 51, 624–638. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Umair, M.; Jiang, Y.; Nerella, D.K.; Ali, M.A.; Steinbach, I. Morphological evolution of γ′ and γ″ precipitation in a model superalloy: Insights from 3D phase-field simulations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 256, 113972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, M.; Yoshida, N.; Kajita, S.; Tokitani, M.; Baba, T.; Ohno, N. In situ observation of structural change of nanostructured tungsten during annealing. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 449, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tong, Y.; Ji, X.X.; Huang, H.; Yang, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hua, M.; Cao, S. Effect of Tantalum content on microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrNiTax medium entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 847, 143322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Sui, H.; Fu, J.; Duan, H. Microstructure-based intergranular fatigue crack nucleation model: Dislocation transmission versus grain boundary cracking. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2023, 173, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Z.; Chen, J.H.; Yang, X.B.; Ren, S.; Wu, C.L.; Xu, H.Y.; Zou, J. Revisiting the precipitation sequence in Al-Zn-Mg-based alloys by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy. Scr. Mater. 2010, 63, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Couchet, C.; Allain, S.Y.P.; Geandier, G.; Teixeira, J.; Gaudez, S.; Macchi, J.; Lamari, M.; Bonnet, F. Recovery of severely deformed ferrite studied by in situ high energy X-ray diffraction. Mater. Charact. 2021, 179, 111346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huo, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, N.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z. Influence of austenitizing temperature on the mechanical properties and microstructure of reduced activation ferritic/martensitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 826, 141934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungár, T.; Borbély, A. The effect of dislocation contrast on X-ray line broadening: A new approach to line profile analysis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 69, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, S.; Kunieda, T. Comparison of the dislocation density in martensitic steels evaluated by some X-ray diffraction methods. ISIJ Int. 2010, 50, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajyakbary, F.; Sietsma, J.; Böttger, A.J. An improved X-ray diffraction analysis method to characterize dislocation density in lath martensitic structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 639, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Poojari, G.; Das, S.; Das, K. Insights into the dynamic impact behavior of intercritically annealed automotive-grade Fe–7Mn–4Al–0.18C steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 887, 145769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.C. The Superalloys Fundamentals and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, Q.L. The Second Phase of Steel and Iron Material; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, H.A.; Davis, C.L.; Thomson, R.C. Modeling solid solution strengthening in nickel alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1997, 28, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypen, L.A.; Deruyttere, A. Multi-component solid solution hardening. J. Mater. Sci. 1977, 12, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Gong, S.; Li, S.; Deng, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; Guo, W. Research on the Influence of Different Aging Temperatures on the Microstructure and Properties of GH2787 Alloy. Crystals 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020081

Wang Y, Xu G, Gong S, Li S, Deng J, Wang T, Liu Z, Guo W. Research on the Influence of Different Aging Temperatures on the Microstructure and Properties of GH2787 Alloy. Crystals. 2026; 16(2):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020081

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yan, Guohua Xu, Shengkai Gong, Shusuo Li, Juan Deng, Tianyi Wang, Zhen Liu, and Wenqi Guo. 2026. "Research on the Influence of Different Aging Temperatures on the Microstructure and Properties of GH2787 Alloy" Crystals 16, no. 2: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020081

APA StyleWang, Y., Xu, G., Gong, S., Li, S., Deng, J., Wang, T., Liu, Z., & Guo, W. (2026). Research on the Influence of Different Aging Temperatures on the Microstructure and Properties of GH2787 Alloy. Crystals, 16(2), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16020081