Abstract

Earth-abundant nickel phosphide electrocatalysts show great potential for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), yet their efficiency requires further enhancement for practical applications. Herein, a novel in situ strategy is developed to synthesize a high-performance electrocatalyst on nickel foam (NF), composed of N-doped carbon-coated Ni5P4–Ni3P heterostructures. This is achieved through the phosphidation and subsequent carbon coating of hydrothermally grown Ni(OH)2 nanosheets. The resulting catalyst exhibits excellent HER activity in acidic media, requiring a low overpotential of only 63 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2. The superior performance stems from the synergistic effects of multiple factors: the porous nanosheet architecture and multi-phase interfaces provide abundant active sites, while the conductive N-doped carbon network significantly enhances charge-transfer kinetics and catalyst stability. This work presents an effective approach for designing efficient non-precious metal HER electrocatalysts.

1. Introduction

In response to the growing energy crisis and environmental issues [1,2,3], hydrogen is regarded as an ideal solution due to its clean, renewable, and efficient nature [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Electrocatalytic water splitting is one of the most fascinating approaches that can realize hydrogen production with low energy consumption [11,12,13,14]. To date, noble Pt is still regarded as the best catalyst with the highest electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution, which has extremely low overpotential and a small Tafel slope. However, the low storage and the high cost of Pt greatly limit its large-scale industrial application [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, designing and developing high-efficiency electrocatalysts toward HER with low cost and enormous reserves still remains challenge.

During the past decades, transition metal-based compounds have been extensively developed, including nitrides [21,22], oxides [23,24], carbides [25,26,27], sulfides [28,29,30], and phosphides [31,32]. Among them, transition metal phosphides such as iron phosphides, nickel phosphides, and cobalt phosphides attract much attention due to their excellent HER activity [33]. Nickel phosphides such as Ni2P, NiP2, Ni12P5, Ni3P, and Ni5P4 with high conductivity and low cost have attracted great research interest [34,35,36,37,38]. However, nickel phosphides single phase cannot meet the current requirements of highly efficient and economic-friendly electrocatalysts. It has already been confirmed that the HER activity can be promoted by creating interfaces between two phases of nickel phosphides, generating rich active sites and modulating the electronic structure. Generally, nickel phosphide polymorphs can be obtained by direct phosphorization of metal nickel. For example, Luo et al. [39] fabricated Ni2P-Ni12P5 via direct phosphorization of NF with the assistance of water. The obtained Ni2P-Ni12P5/NF catalysts have been certified with abundant interfaces and, as a consequence, possessed excellent HER performance and durability in alkaline condition. Furthermore, electrocatalysts with multi-phase features and hierarchical coupling architecture can have strong electronic interaction between different components, which leads to the synergistic effect that could alter the charge distribution and is also beneficial for optimizing adsorption through lowering the free energy of hydrogen. For example, Li et al. [40] designed an electrocatalyst by embedding Ni-Ni3P nanoparticles into N, P-doped carbon on 3D graphene framework, the abundant active area and interfaces of the electrocatalyst endow the outstanding HER activity. Therefore, combining different phases of nickel phosphides coated with carbon conductive as the three-dimensional conductive skeleton to construct a multi-component catalyst with multi-interfaces is expected to achieve the simultaneous optimization of the electronic structures and active sites, thereby accelerating HER kinetics.

In this study, we designed a multi-component electrocatalyst consisting of N-doped carbon coating, Ni3P, and Ni5P4 and NF (NF). The N-doped carbon-coated Ni5P4-Ni3P/Ni electrocatalysts can be obtained by hydrothermal growth of Ni(OH)2 nanosheets on the NF, followed by in situ phosphating the resulting Ni(OH)2/NF with red phosphorus and thermal treatment with g-C3N4. Due to the delicate structural design, rich active sites, and compositional modulation, the as-prepared optimized electrocatalyst displays attractive HER performance with 63 mV and 260 mV overpotentials to produce a current density of 10 mA cm−2 and 100 mA cm−2 in acidic electrolyte, respectively. It is anticipated that this contribution could provide a novel strategy for the preparation of mesoporous metal phosphide-based HER electrocatalyst with rich-edge active sites and high nitrogen-doped carbon coating.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

NF, nickel nitrate, ammonium fluoride, urea, red phosphorus, platinum, and melamine were all purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). All reagents are of analytical reagent grade, which were used as received without further purification.

2.2. Preparation of Ni(OH)2/NF

Firstly, several pieces of NFs with a size of 2 cm × 5 cm were placed into 1M HCl solution and sonicated for 10 min to remove the oxide layer on the surface, then rinsed alternately with deionized water and ethanol for more than three cycles. Subsequently, they were dried in a vacuum drying oven at a temperature of 60 °C and maintained at this temperature for 12 h.

Ni(OH)2 nanosheets grown on the NF were obtained according to the previous literature [41]. In a typical synthesis process, 0.58 g Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.148 g NH4F, and 0.6 g urea were dissolved in 30 mL deionized water to obtain a homogeneous solution which was followed by ultrasound treatment for 20 min. The cleaned NF was put into the above prepared solution, and continued to sonicate for 30 min. Then, the NF together with the solution were put into the lining of the Teflon reaction kettle and left to stand for 4 h. Finally, the polytetrafluoroethylene lining was put into a stainless steel reaction kettle, heated to 120 °C and kept for 10 h. After the reaction kettle was naturally cooled to room temperature, the resulting product was taken out, rinsed off with ethanol and deionized water, and finally dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h.

2.3. Preparation of Nickel Phosphide/NF

In order to in situ synthesize nickel phosphide nanosheets on the NF substrate derived from the resulting Ni(OH)2 nanosheet, the sample was cut into a size of 2 cm × 0.5 cm, and three strips of NF (each 120 mg) and 6 mg of red phosphorus were put into a dented quartz tube. After adding the quartz plug, the quartz tube was evacuated, and the quartz plug was heated with a hydrogen–oxygen flame gun to melt it together with the quartz tube. Subsequently, the sealed quartz tube was put into a muffle furnace and heated to 600 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1 for 3 h, and then naturally cooled to room temperature.

2.4. Preparation of N-Doped Carbon-Coated Ni5P4-Ni3P/NF

First, 5 g of melamine powder was put into a crucible, covered, and placed in a muffle furnace. It was heated to 650 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1, and kept for 3 h. After naturally dropping to room temperature, the obtained g-C3N4 bulk material was ground into powders and put into a crucible again, heated to 500 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1, and kept for 2 h. After naturally cooling to room temperature, g-C3N4 powders were obtained.

Two small strips of NiP/NF prepared above were vacuum sealed with 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg of g-C3N4 addition, respectively. The sealed quartz tube was put into a muffle furnace and heated up to 700 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1, keeping the temperature for 3 h, and naturally cooling to room temperature. With the amount of g-C3N4 increase, the resulting products were marked as NCNPNF-1, NCNPNF-2, and NCNPNF-3, respectively.

2.5. Electrochemical Measurement

The electrochemical test was carried out with a three-electrode system at room temperature, and the electrochemical workstation used in the test was the CHI660E workstation produced by Shanghai ChenHua Company (Shanghai, China). The working electrode is the prepared nickel phosphide material, the counter electrode is the carbon rod, and the reference electrode is the saturated calomel electrode. HER measurements were evaluated by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 with a test voltage range of −0.241 to −1 V with iR compensation. The electrolyte tested was a nitrogen-saturated H2SO4 solution. Electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was determined by a series of CV tests (scan rate: 10~120 mV s−1). The multi-step chronopotentiometric test starts from −0.241, with 0.05 V increments per step, and 12-step tests for each step of 500 s. In this work, all potentials are referenced to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). The potential conversion equation from SCE to RHE is described as follows: ERHE = ESCE + 0.0591 pH + 0.241. The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) values were estimated from the electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl), as described in the following equation [42]:

2.6. Characterization

The morphologies and structure of the samples were explored using a S-4800 (Hitachi, Chiyoda, Japan) field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) instrument and a Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) transmission electron microscope (TEM), respectively. The XRD patterns were recorded using a Rigaku D/max2200PC X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. Data were collected in the 2θ range of 20° to 80° with a scanning step of 0.02° and a scanning speed of 5° min−1. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were acquired with using a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha system (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) under an Al Kα X-ray source (hv = 1486.6 eV). Raman spectra were obtained via a DXR Raman Microscope (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) using a 532 nm laser.

3. Results and Discussion

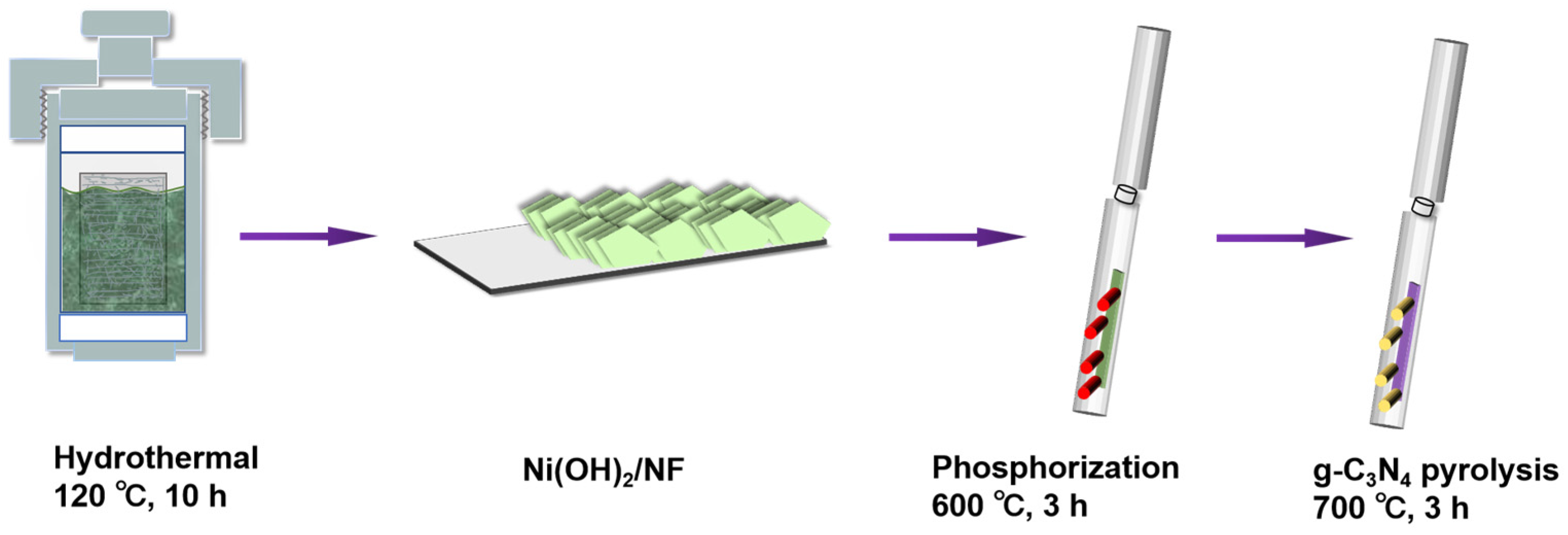

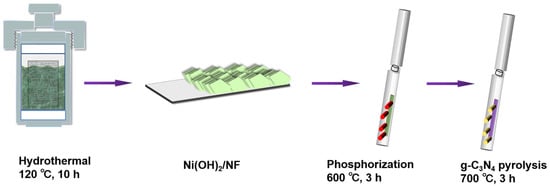

As presented in Figure 1, the typical preparation process of NC-coated NP/NF nanosheets can contain three main steps: (1) hydrothermal growth of Ni(OH)2 nanosheets on the NF; (2) in situ phosphidation of Ni(OH)2 nanosheets to form porous NiP nanosheets; and (3) in situ nitrogen-doped carbon-coated resulting NiP nanosheets to form NiP-NC with the interconnected porous conductive carbon framework. As for step 1, high quality Ni(OH)2 nanosheets with green color can be well grown on the surface of NF via a facile solvothermal approach. Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials) demonstrates that the crystal structure of the resulting product is a mixture of metal Ni (JCPDS No 65-2865) and Ni(OH)2 (JCPDS No 38-0715) [42,43], which is denoted as Ni(OH)2/NF. In the following phosphorization process, the diffraction peaks of Ni(OH)2 can disappear and weak peaks of Ni3P (JCPDS No 65-1605) can emerge, indicating that Ni(OH)2 can be completely transformed into the Ni3P crystal, and the as-obtained product is denoted as NiP/NF. Thereafter, a series of NCNPNF samples can be obtained via the carbon coating treatment with the NP/NF produced in step 2 with different amounts of g-C3N4 addition at 700 °C.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration for the preparation process of NCNPNF.

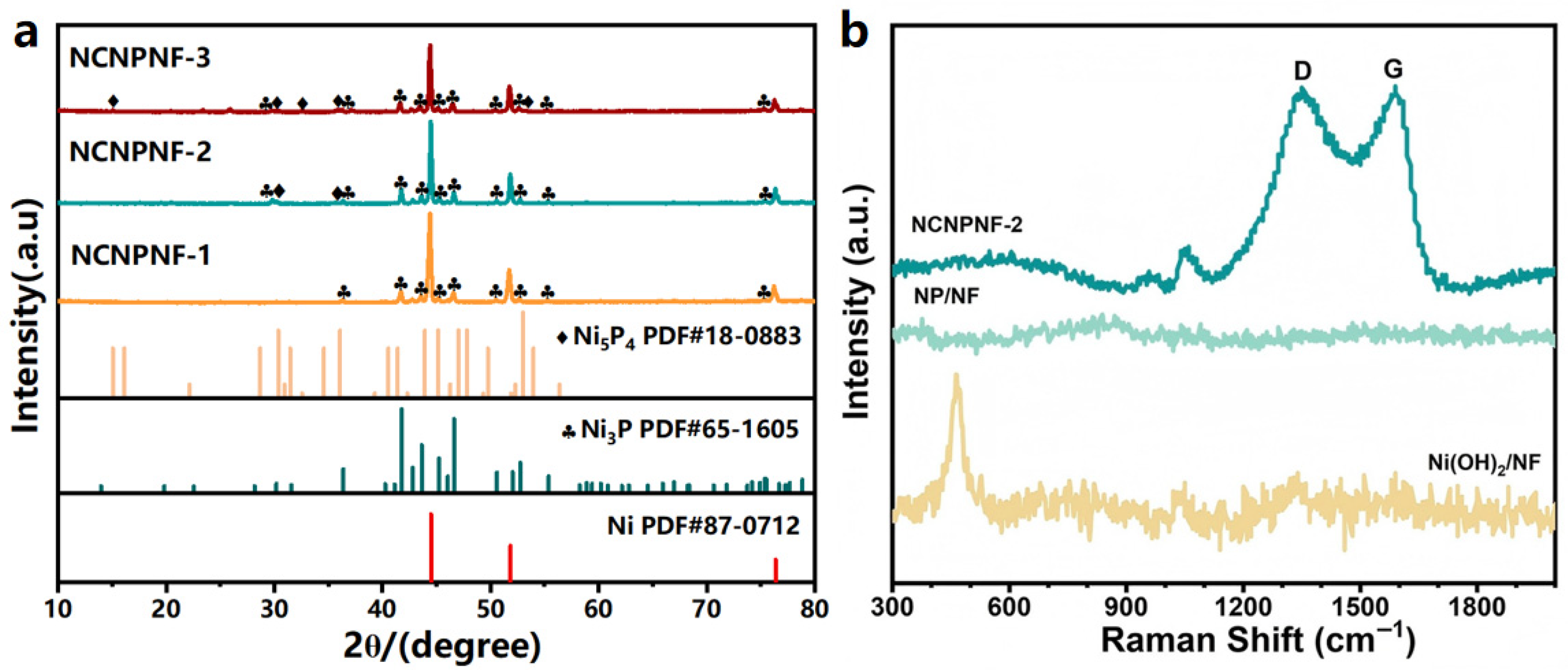

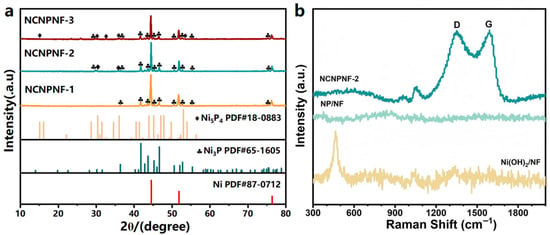

Figure 2a displays the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the products treated with different amounts of melamine derived g-C3N4 heated at 700 °C. For NCNPNF-1, the diffraction peaks at approximately 2θ = 44.5°, 51.9°, and 76.4° can be indexed to the crystal planes of (111), (200), and (220) of metal Ni (JCPDS No 87-0712) [44,45], respectively. The diffraction peaks at approximately 2θ = 36.4°, 41.8°, 42.8°, 43.7°, 50.6°, 52.8°, and 55.4° can be attributed to the crystal plane of (301), (321), (330), (112), (222), (312), and (341) of Ni3P (JCPDS No 65-1605), respectively. For the XRD pattern of NCNPNF-2 and NCNPNF-3, weak diffraction peaks of Ni5P4 (JCPDS No 18-0883) [46] can be observed, demonstrating that homojunction Ni3P-Ni5P4 can be formed in the sample NCNPNF-2 and NCNPNF-3. The phosphidation process generates a multi-phase homojunction within a single nanosheet, leading to abundant interfaces between distinct crystalline phases and porous structure with enriched edge states. This significantly enhances the photoelectrochemical (PEC) activity of NiP-based electrocatalysts. In particular, the formation of the NiP multiple-phase junctions with the size of several nanometers can be highly desired for effective charge transfer and separation. Therefore, the rational design of such the NiP-based two-phase junctions provides a promising strategy to enhance the PEC hydrogen generation efficiency. To resolve the overlapping diffraction features and quantify the phase composition, LeBail fitting was performed (Figure S2). The excellent fit (Rwp = 3.76%) confirms the successful formation of the predominant Ni3P phase alongside trace Ni5P4, establishing the intended heterojunction. A minor amount of nickel phosphate (Ni2P2O7, <8 wt%) was also identified, attributable to surface oxidation during high-temperature synthesis—a common phenomenon that does not compromise the primary heterostructure. This quantitative analysis validates our catalyst design centered on the Ni3P-Ni5P4 interface. Notably, no distinct sharp diffraction peaks corresponding to crystalline graphitic carbon are discernible, indicating that the N-doped carbon coating is predominantly amorphous. Raman spectra (Figure 2b) are used to further confirm the existence of carbon. Two typical response peaks, D-band and G-band, appear at approximately 1349.9 and 1590 cm−1, which stand for the disorder or structure defects in the sp2-hybridized carbon atoms and in-plane vibrations of sp2 atoms in a 2D hexagonal graphitic lattice [47], respectively. A peak observed in Ni(OH)2/NF at 460 cm−1 may come from the defect states of oxygen vacancies, while NiP/NF displays no obvious peaks.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns of the prepared samples; (b) Raman spectra of Ni(OH)2/NF, NP/NF, and NCNPNF-2, respectively.

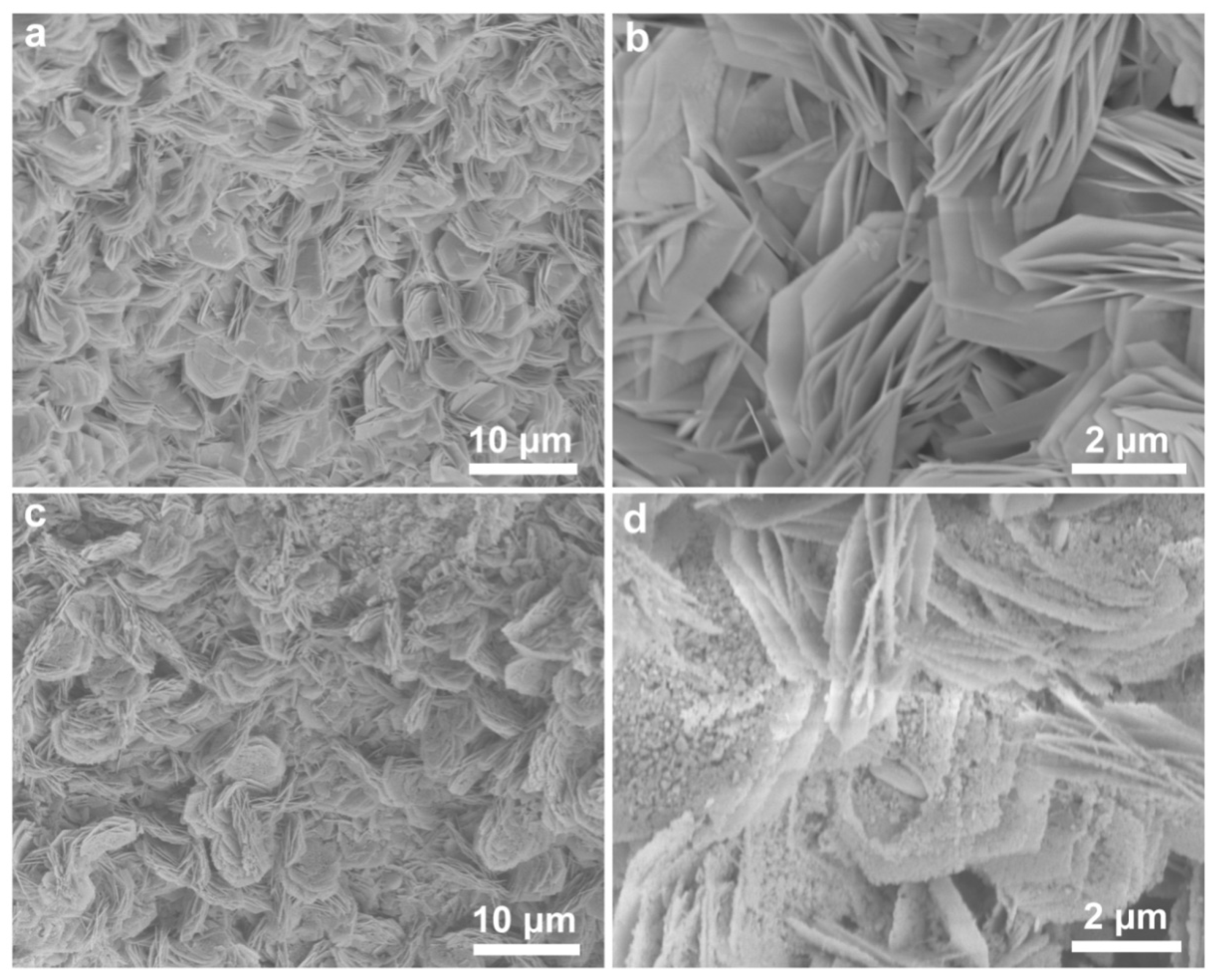

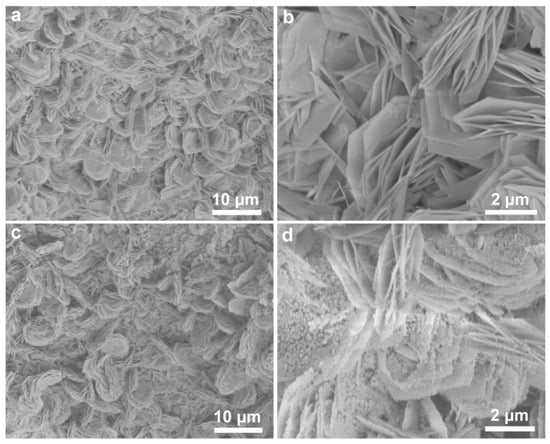

The morphologies of the as-prepared samples were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Figure 3a,b show that the obtained Ni(OH)2/NF are composed of numerous self-assembled ultrathin hierarchical nanosheets. The nanosheets have uniform morphology with the thickness of 20 nm and the lateral dimension of several micrometers, indicating that there are only tens of atom layers in one nanosheet. And meanwhile, they are vertically aligned and interconnected with each other on the surface of NF. As shown in Figure 3c,d, NiP possesses more pore structures and many nanoparticles are distributed over the nanosheets. The resulting NiP nanosheets exhibit a porous structure with a relatively rough surface instead of a smooth one, primarily attributed to the generation of pores induced by the phosphidation process. The digital pictures of these samples are given in Figure S3, and obviously changes in the surface can be observed.

Figure 3.

(a,b) SEM images of Ni(OH)2 nanosheets grown on the NF substrate with different magnification, (c) SEM images of the in situ phosphidation growth of NiP nanosheet, and (d) nitrogen-doped carbon-coated NiP nanosheet.

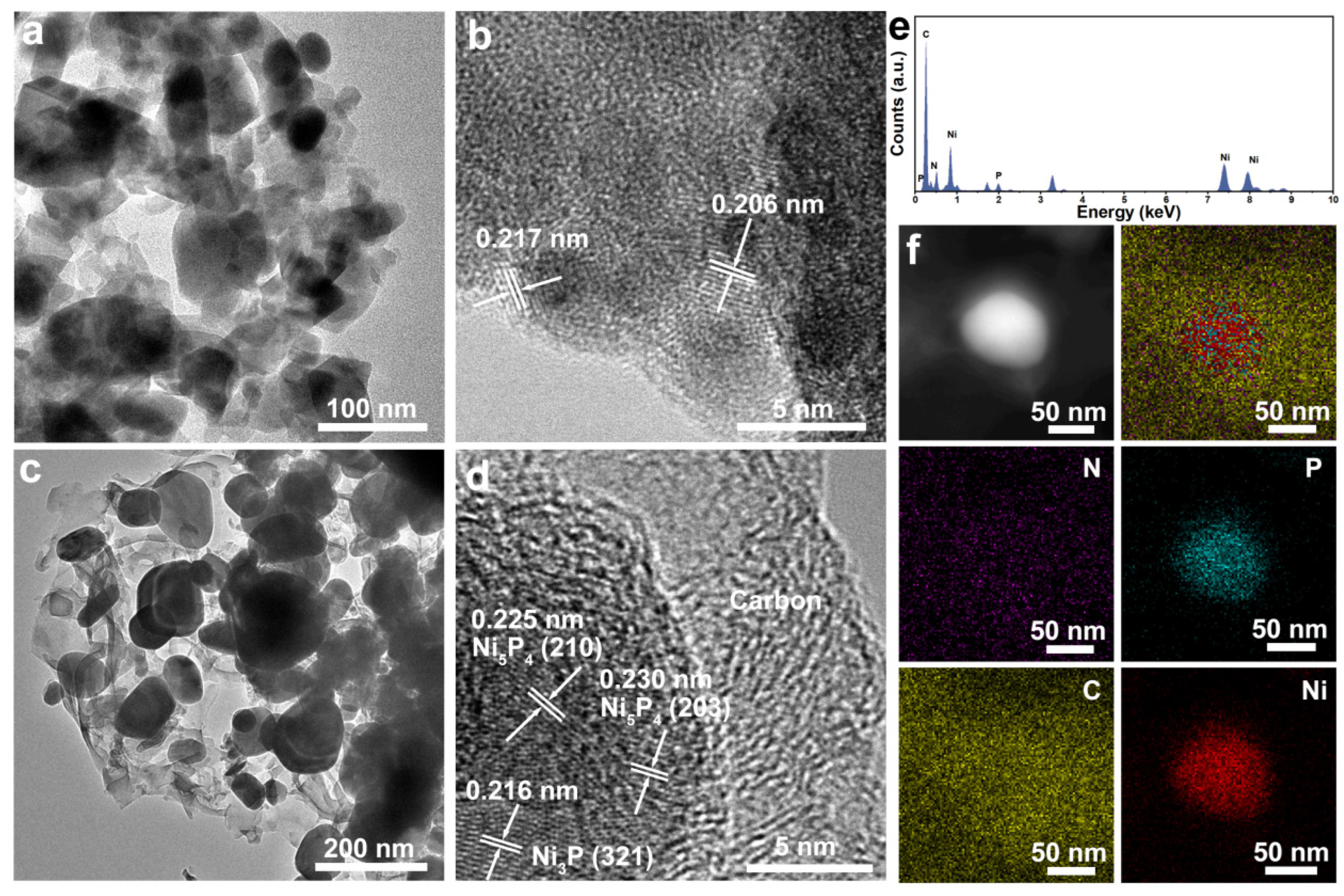

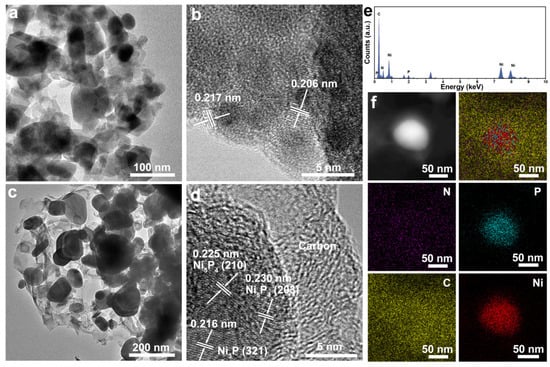

TEM was used to further analyze the microstructure, pore size distribution, the forming pore–grain interface, and crystal structure. As shown in Figure 4a, the synthesized NiP nanosheets are of hierarchical porous structure with interconnected nanograins with the diameter in the range of 20~180 nm and a pore size ranging from 10 to 60 nanometers. At the same time, the porous feature means that they can have a rich grain interface, indicating higher surface area and rich active sites for PEC performance compared with that of an NiP nanosheet with a smooth surface. The lattice fringes of 0.217 nm and 0.206 nm observed by HRTEM belong to the (321) and (112) crystal planes of Ni3P (Figure 4b), respectively, confirming that the Ni(OH)2 can be transformed to Ni3P crystal structure during the phosphorization process. Microstructure information about the NCNPNF-2 sample can be found in Figure 4c,f. Figure 4c clearly reveals that the two-dimensional layer-like structures exhibiting a typically wrinkled feature can be observed and these structures filled inside the pore of NiP nanosheet can connect with the Ni3P nanograins after the carbon coating treatment using g-C3N4 addition. The HRTEM image (Figure 4d) clearly demonstrates the existence of rich interfaces between Ni5P4, Ni3P, and carbon, and the exhibited apparent lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.216 nm can be attributed to the (321) plane of Ni3P, while the lattice fringes of 0.225 nm and 0.230 nm belong to the (210) and (203) crystal planes of Ni5P4, respectively. These results indicate the coexistence of Ni5P4 and Ni3P in NCNPNF-2, which is in good agreement with that of the XRD results (Figure 2a). The intimate Ni5P4–Ni3P interface visualized here facilitates strong electronic coupling, which is expected to modulate the local electronic environment, lowering the energy barrier for hydrogen adsorption/desorption and enhancing charge transport—a mechanism supported by studies on similar nickel phosphide heterostructures [39]. Consequently, the heterostructured NCNPNF-2 exhibits superior HER kinetics, as evidenced by its reduced Tafel slope and charge-transfer resistance compared to single-phase catalysts. Furthermore, the HRTEM images further reveal that a uniform, amorphous N-doped carbon coating encapsulates the Ni5P4–Ni3P nanoparticles, forming a continuous and conformal shell. The thickness of the carbon layer is estimated to be approximately 6–8 nm based on the TEM observations, and it exhibits a relatively uniform distribution across the sample. This thin yet continuous carbon coating not only enhances the electrical conductivity but also protects the phosphide phases from corrosion during the HER process, thereby contributing to both activity and stability. The corresponding EDX spectrum (Figure 4e), recorded from the area of Figure 4d, verifies that the NCNPNF-2 are composed of P, C, Ni, and N elements. Minor signals, including one from the Cu grid used for TEM analysis, are present but do not affect the primary compositional analysis. The energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mapping images in Figure 4f demonstrate that both N and C elements are uniformly distributed throughout the whole area, suggesting that g-C3N4 have been converted into N-doped carbon coating at the pyrolysis temperature of 700 °C. Meanwhile, P and Ni elements, only distributed on the area with brighter color, demonstrate that the Ni5P4-Ni3P nanoparticle can be wrapped by the N-doped carbon shells. According to the above results, it can be concluded that NCNPNF-2 with multi-interfaces consists of N-doped carbon, Ni5P4, Ni3P, and Ni. The porosity property, in conjunction with carbon coating and the NiP two-phase interface, provides a plethora of active sites for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) on the surface of NiP/N-C nanosheets. This structural feature is of paramount importance in facilitating the development of high-performance electrocatalysts.

Figure 4.

Typical TEM images of (a,b) NP/NF and (c,d) NCNPNF-2 sample (the lattice fringes in (d) show spacings corresponding to Ni4P5 and Ni3P planes). (e) EDX elemental spectrum and (f) mapping of N, P, C, and Ni of NCNPNF-2, respectively.

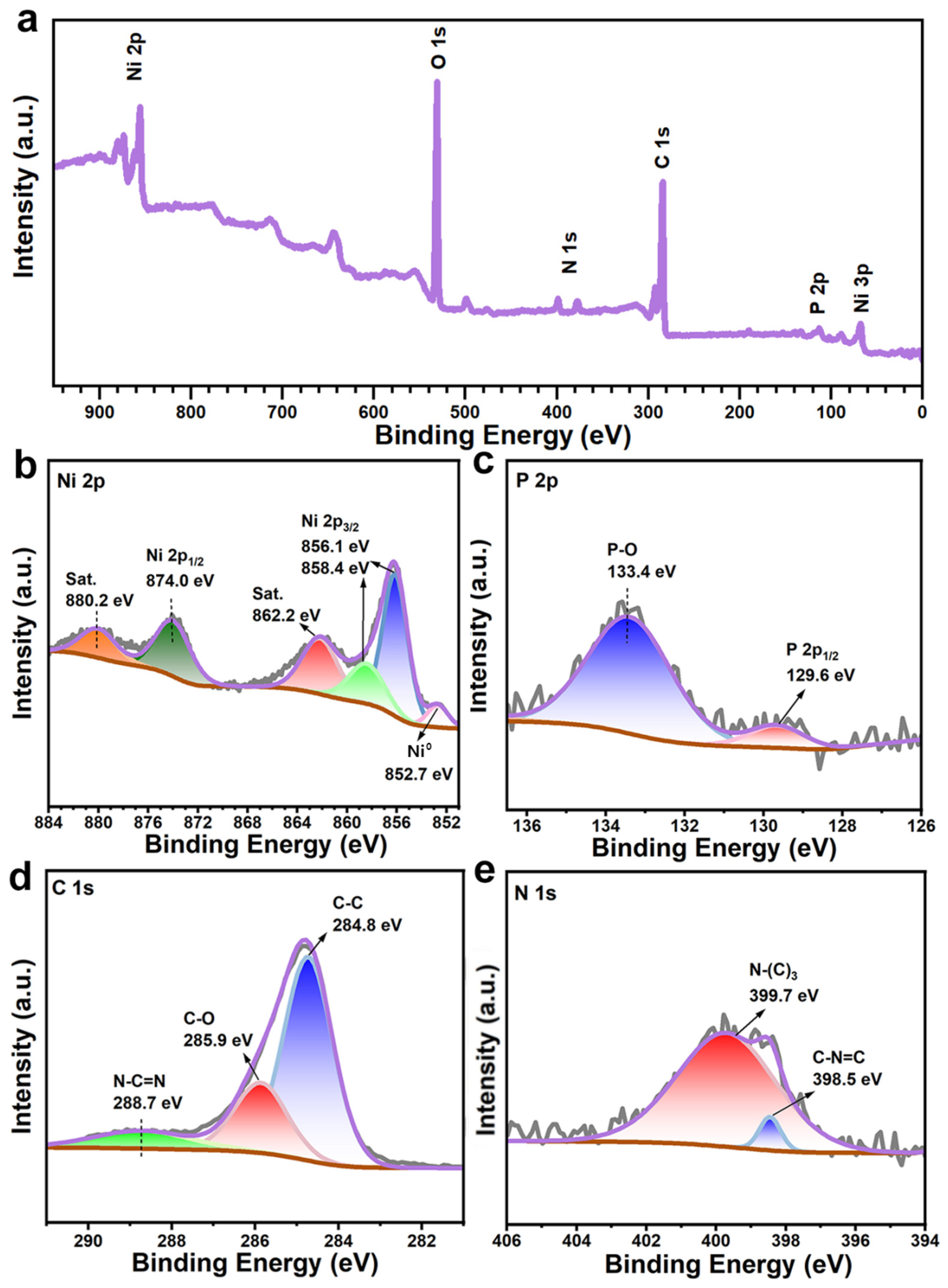

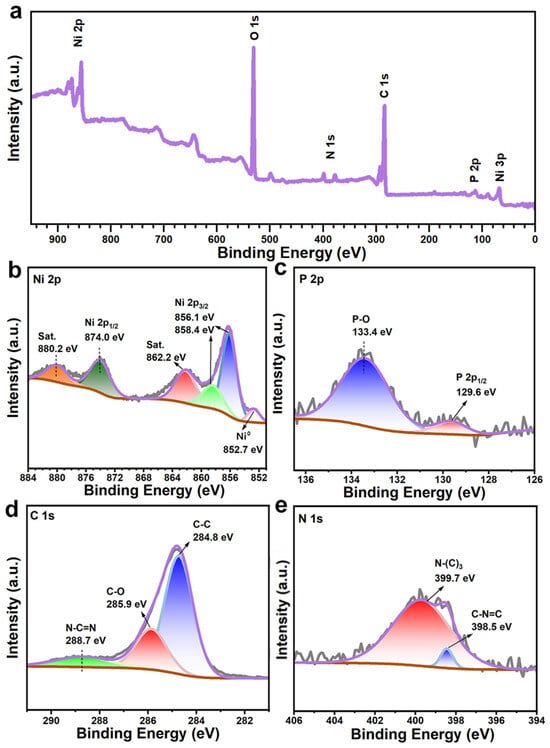

The elemental compositions and chemical states of NCNPNF-2 were measured by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). It is manifested from Figure 5a that the characteristic peaks of Ni, P, C, and N elements are observed in the survey spectrum, confirming the presence of the NiP and N-carbon in NCNPNF-2, which corresponds to the elemental mapping results. For the Ni 2p spectrum (Figure 5b), the peak located at 874.0 eV can be attributed to Ni 2p1/2, and the peaks at 858.4 eV and 856.1 eV can be indexed by Ni 2p3/2, respectively. The peaks at 862.2 eV and 880.2 eV are the corresponding satellite peaks, indicating the existence of the Ni2+ species, which arises from the inevitable surface oxidation when exposing the phosphide to air. Notably, the distinct peak observed at approximately 852.7 eV is assigned to metallic nickel (Ni0), confirming the presence of the NF substrate within the probed region. This multi-component Ni 2p signature—encompassing Ni0 and Ni2+ in phosphides and surface Ni2+ oxides/hydroxides—corroborates the complex phase composition revealed by XRD. As for the P 2p spectra in Figure 5c, the doublet with the P 2p3/2 peak at 129.6 eV is assigned to phosphide anions (P3−) in the nickel phosphides (Ni5P4-Ni3P). The peak at 133.4 eV originates from phosphorus in a pentavalent oxidized state (P5+, e.g., in phosphate species), likely formed due to surface oxidation [48,49]. The peaks at 284.8, 285.9, and 288.7 eV for C 1 s spectra in Figure 5d can be attributed to the strong C–C, C–O, and N–C=N from carbon-doped C [48], respectively. From Figure 5e, it can be observed that two peaks of N 1s at 399.8 eV and 398.4 eV can be assigned to the tertiary N bonded to carbon atoms (N–(C)3) and the sp2-bonded nitrogen in C–N=C, respectively, which illustrates that the N atom is incorporated into carbon [50]. Due to the disparity in size, bond length, and valence electrons, nitrogen-doped carbon can effectively induce a large number of defects in the carbon microstructure and increase the specific surface area to accommodate more ions, further forming more HER active centers, improving the performance of materials.

Figure 5.

(a) Wide-scan XPS survey of NCNPNF-2 and corresponding high resolution XPS: (b) Ni 2p, (c) P 2p, (d) C 1s, and (e) N 1s, respectively.

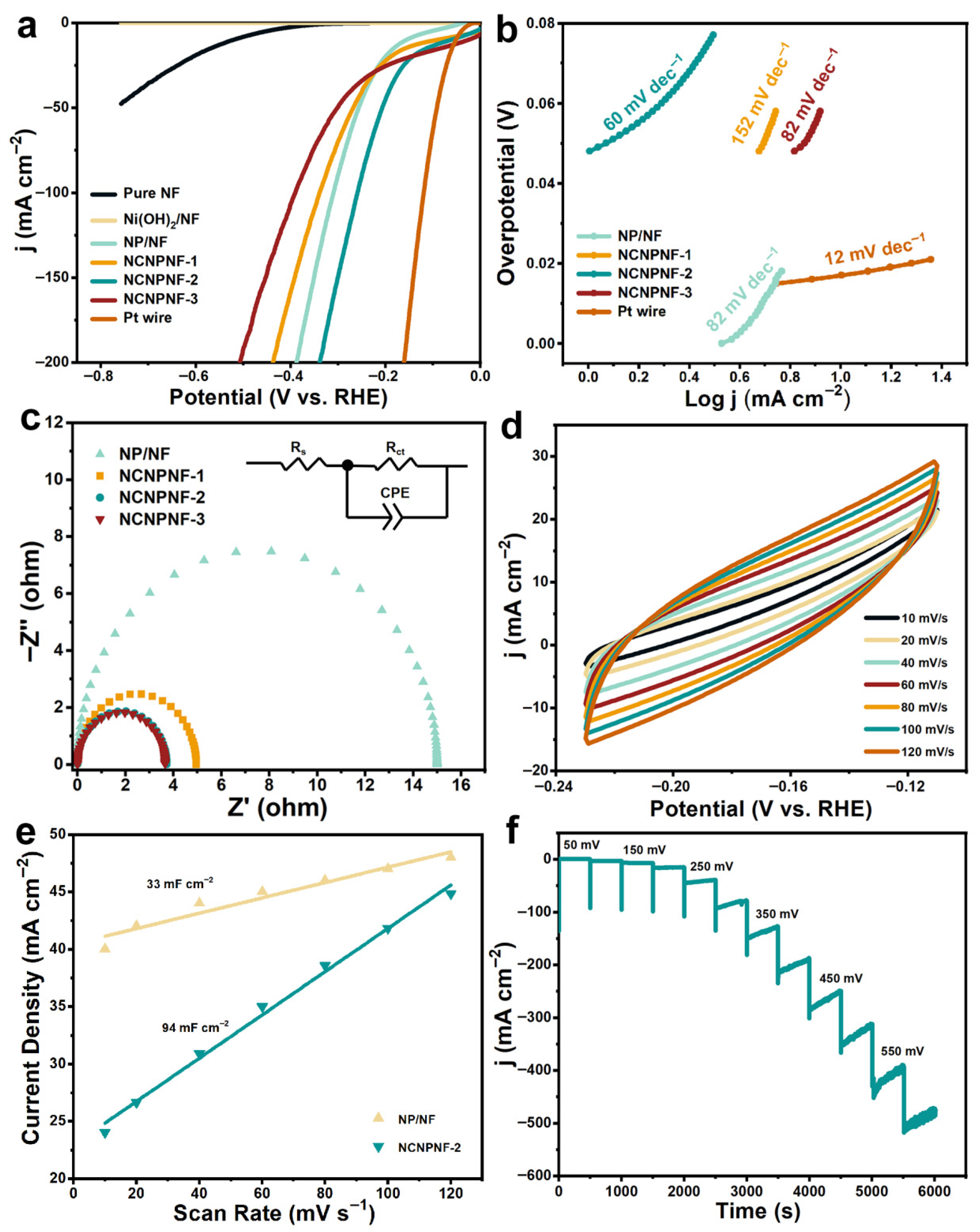

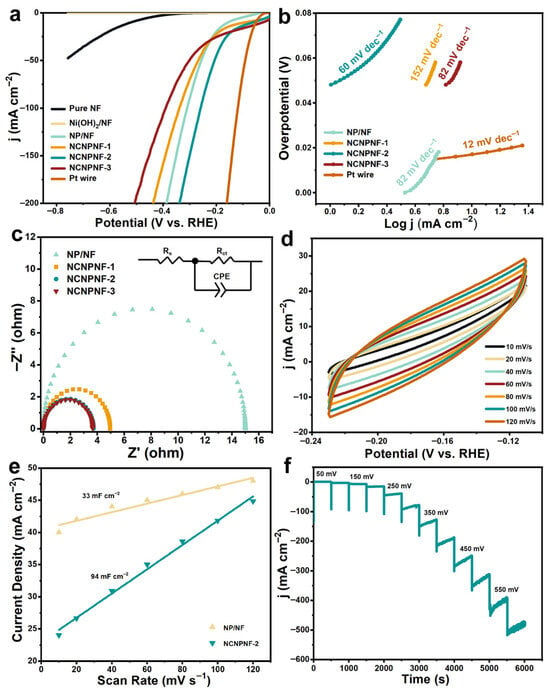

The electrocatalytic HER performance of the as-prepared samples were investigated in a typical three-electrode configuration in 0.5 M N2-saturated H2SO4 solution. Figure 6a shows the HER polarization curves of pure NF, Ni(OH)2/NF, NP/NF, NCNPNF, and Pt wire electrocatalysts. The Ni(OH)2/NF sample exhibits negligible HER activity. As expected, the Pt wire possessed the best HER performance among the tested samples, only requiring an overpotential of 52 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2 and an overpotential of 120 mV at a current density of 100 mA cm−2. It can be observed that NCNPNF-2 possesses the most excellent HER performance with a low overpotential of 63 mV to achieve the current density of 10 mA cm−2, that is lower than that of NP/NF (156 mV) and NCNPNF-1 (92 mV). In particular, for NCNPNF-3, it only needs an overpotential of 26 mV to reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2, but in terms to producing a high current density, for example, 100 mA cm−2, NCNPNF-3 requires an overpotential of 391 mV, which is higher than that of NP/NF (310 mV), NCNPNF-1 (340 mV), and NCNPNF-2 (260 mV). The above results demonstrate that the Ni5P4-Ni3P and N-doped carbon coating can play important role in enhancing HER activity. The HER kinetics of the samples can be evaluated by the corresponding Tafel plots. As displayed in Figure 6b, the Tafel slope of NCNPNF-2 is calculated to be 60 mV dec−1, which is significantly smaller than that of NP/NF (82 mV dec−1), NCNPNF-1 (152 mV dec−1), and NCNPNF-3 (82 mV dec−1), indicating a fast electron transfer and thus favorable HER kinetics proceeding on NCNPNF-2. This further proves that the developed N-doped carbon-coated Ni5P4-Ni3P/NF creates fast-moving conditions for an electron transfer route. According to the established mechanisms for the HER in acid media, the Tafel slope value of NCNPNF-2 electrode manifests that the HER should follow a Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism (H+ + e− → Had, H+ + Had + e− → H2) [40,51]. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out to gain further insight into the electrode kinetics during the HER process. As illustrated in Figure 6c, the Nyquist plot of the NCNPNF-2 exhibits a lower charge-transfer resistance (Rct) value of 3.72 Ω than that of NP/NF (14.99 Ω) and NCNPNF-1 (4.95 Ω), suggesting the favorable kinetics of NCNPNF-2 during the HER process. This reduced resistance benefits from the integrated conductive network: the metallic NF substrate provides a highly conductive backbone for efficient electron collection and delivery, while the N-doped carbon coating further enhances charge transfer across the active Ni5P4–Ni3P phases. Notably, NCNPNF-3 displays the smallest charge-transfer resistance, which might be explained by the fact that NCNPNF-3 requires the smallest overpotential at current density of 10 mA cm−2. Those results again confirm that the N-doped carbon collaborated with Ni5P4-Ni3P/Ni could significantly enhance the charge transport kinetics of the HER, which is mainly attributed to the continuous and excess carbon providing a channel for electron transfer. However, the excess carbon forming thick and continuous carbon coating can greatly encapsulate the HER active site and interface of NiP nanograins, hindering them from contacting with the electrolyte. The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) of NCNPNF-2 and NP/NF were measured by cyclic voltammograms (CVs), which is a pivotal parameter for estimating the electrochemical area at the solid–liquid interface. The electrochemical activities can be further normalized by the electrochemical surface area (ECSA) [52]. The ECSA were calculated from the electrochemical Cdl acquired from CV in a non-faradaic region [42]. Figure 6d reveals the CV curves of NCNPNF-2 in the potential range of −0.11 to 0.23 V versus reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) at various scan rates. On the basis of the CV results, the Cdl value of the NCNPNF-2 is identified to be 94 mF cm−2, which is almost 2.8 times than that of the NP/NF (33 mF cm−2) (Figure 6e). Apart from the remarkable activity, the long-term stability of the HER electrocatalyst is also recognized as a critical criterion for practical large-scale applications. Figure 6f demonstrates the multi-potential step curves for NCNPNF-2 in acidic electrolyte, demonstrating the impressive electrochemical stability in acid solution.

Figure 6.

HER performance of the prepared electrocatalysts in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. (a) IR-corrected LSV polarization curves, (b) corresponding Tafel slopes, (c) Nyquist plots, (d) cyclic voltammetry curves, (e) double-layer capacitance (Cdl), and (f) multi-step chronoamperometric curve of NCNPNF-2, respectively.

To comprehensively evaluate the HER performance of our catalyst, we compare NCNPNF-2 with other recently reported nickel phosphide-based electrocatalysts in acidic media (Table 1). While some catalysts achieve slightly lower overpotentials at 10 mA cm−2 (e.g., 13 mV for CoP@WP2/NF-2h [53], 61 mV for Ni3Fe–Ni3P/NF [54]), NCNPNF-2 offers a balanced and competitive performance profile. It exhibits a low overpotential (63 mV), favorable kinetics (Tafel slope of 60 mV dec−1), and excellent long-term stability (>24 h). More importantly, this performance is achieved through a simple, scalable synthesis route without requiring noble metals, complex heteroatom doping, or exotic supports. The superior performance of NCNPNF-2 can be attributed to the synergistic effects of its unique architecture: the mesoporous nanosheet morphology ensures high surface area and efficient mass transport; the in situ formed Ni5P4-Ni3P heterojunctions optimize the electronic structure for hydrogen adsorption and the conformal N-doped carbon coating enhances electrical conductivity while protecting active sites. This comparison validates our design strategy and demonstrates that NCNPNF-2 is a promising, cost-effective alternative to precious metal-based HER electrocatalysts.

Table 1.

Comparison of HER performance for NCNPNF-2 and recently reported nickel phosphide-based electrocatalysts in acidic media.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a high-performance HER electrocatalyst composed of N-doped carbon-coated Ni5P4–Ni3P heterostructures supported on NF (NCNPNF-2) via a simple and scalable hydrothermal–phosphidation–carbonization route. Comprehensive characterization (XRD, SEM, TEM, XPS, Raman) clearly delineates the structural evolution at each synthesis stage: from vertically aligned Ni(OH)2 nanosheets to porous NiP nanosheets and finally to carbon-encapsulated Ni5P4–Ni3P heterojunctions. The optimized NCNPNF-2 catalyst exhibits outstanding HER activity in 0.5 M H2SO4, requiring low overpotentials of only 63 mV and 260 mV to deliver current densities of 10 and 100 mA cm−2, respectively, along with a favorable Tafel slope of 60 mV dec−1 and robust long-term stability (>24 h). This performance is highly competitive among recently reported non-precious metal phosphide electrocatalysts.

The enhanced HER performance is attributed to the synergistic combination of several structural and electronic features. The interconnected nanosheet architecture ensures efficient charge transport pathways and exposes abundant active sites, as evidenced by the lower charge-transfer resistance and higher double-layer capacitance of NCNPNF-2 compared to the uncoated counterpart. Furthermore, the intimate Ni5P4–Ni3P heterointerface, confirmed by both XRD and HRTEM, promotes favorable electronic coupling that optimizes hydrogen adsorption energy, leading to improved intrinsic activity reflected in the reduced Tafel slope. Additionally, the conformal N-doped carbon coating significantly enhances electrical conductivity across the catalyst framework and simultaneously protects the active phosphide phases from degradation during prolonged HER operation. This work provides a rational and effective strategy for designing efficient, stable, and cost-effective HER electrocatalysts through integrated heterostructure and surface engineering.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst16020100/s1, Figure S1:XRD patterns of the prepared NiOH nanosheet (red curve), NiP (yellow curve), and N-C coating- NiP compounds (blue curve), respectively; Figure S2: LeBail fitting of the XRD pattern for the NCNPNF-2 catalyst; Figure S3: Digital photos of the resulting samples.

Author Contributions

X.N. and Z.G.: Conceptualization. Y.T. and C.W.: Methodology, Investigation (including synthesis, material characterizations, electrochemical measurements, and device assembly), Formal analysis. X.M., H.W. and H.P.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program for Demand-Driven Basic Research, Department of Science and Technology of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2025JH2/101330019); the Liaoning Province International Cooperation Project (Grant No. 2023030491-JH2/107); the Tsinghua University Open Fund (Grant No. KY-2024126); and the Northeast Geological Science and Technology Innovation Center (Grant Nos. QCJJ2023-46, QCJJ2023-50).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wen, Y.; Cai, H.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z. Effects of freeze-thaw cycles on soil greenhouse gas emissions: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, X.; Qi, C.Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D. Sedum alfredii Hance: A cadmium and zinc hyperaccumulating plant. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Cai, H.; Song, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. Stress of polyethylene and polylactic acid microplastics on pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) and soil bacteria: Biochar mitigation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekalgne, M.A.; Nguyen, T.V.; Hong, S.H.; Le, Q.V.; Ryu, S.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Synergistic enhancement of electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution by CoS2 nanoparticle-modified P-doped Ti3C2Tx heterostructure in acidic and alkaline media. Fuel 2024, 371, 131976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.L.; Lu, X.F.; Wu, Z.P.; Luan, D.; Lou, X.W.D. Engineering Platinum-Cobalt Nano-alloys in Porous Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotubes for Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19068–19073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, A.L.; Xiao, W.; Chao, D.; Zhang, X.; Tiep, N.H.; Chen, S.; Kang, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, J.; et al. In Situ Grown Epitaxial Heterojunction Exhibits High-Performance Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhong, C.; Hu, W.; Han, X. Phase and composition controlled synthesis of cobalt sulfide hollow nanospheres for electrocatalytic water splitting. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 4816–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhou, W.; Kou, Z.; Pennycook, S.J.; Xie, J.; Guan, C.; Wang, J. Open hollow Co–Pt clusters embedded in carbon nanoflake arrays for highly efficient alkaline water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 20214–20223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Geng, Z.; Zeng, J. Doping regulation in transition metal compounds for electrocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 9817–9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, W.; Duan, H.; Jiang, J. Recent developments and perspectives of Ti-based transition metal carbides/nitrides for photocatalytic applications: A critical review. Mater. Today 2024, 76, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, S.; Tian, N.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Nanostructured Metal Sulfides: Classification, Modification Strategy, and Solar-Driven CO2 Reduction Application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 31, 2008008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Wang, L. A self-templating method for metal–organic frameworks to construct multi-shelled bimetallic phosphide hollow microspheres as highly efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8602–8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, W.; Xiong, W.; Zeng, G.; Huang, D.; Zhang, C.; Song, B.; Xue, W.; Li, X.; et al. Recent advances in application of transition metal phosphides for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Deng, C.; Ding, H.; Huang, T.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L. Cerium doping induces in-situ reconstruction of Ni5P4 to enhance urea-assisted water splitting. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 543, 147556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, A.; Wang, C.; Zhou, W.; Liu, S.; Guo, L. Interfacial Electron Transfer of Ni2 P-NiP2 Polymorphs Inducing Enhanced Electrochemical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1803590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, A.B.; Wexler, R.B.; Whitaker, M.J.; Izett, E.J.; Calvinho, K.U.D.; Hwang, S.; Rucker, R.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Garfunkel, E.; et al. Climbing the Volcano of Electrocatalytic Activity while Avoiding Catalyst Corrosion: Ni3P, a Hydrogen Evolution Electrocatalyst Stable in Both Acid and Alkali. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4408–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, S.; Chen, S.; Yu, Y.; Bao, S.; Xu, M.; Yue, Q.; Xin, H.; et al. Nanoporous V-Doped Ni5P4 Microsphere: A Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction at All pH. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 37092–37099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Feng, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wilkinson, D.P. Non-noble Metal Electrocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Water Electrolysis. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2021, 4, 473–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaravel, S.; Vignesh, S.; Balu, K.; Madhu, R.; Kusmartsev, F.V.; Alkallas, F.H.; Ben Gouider Trabelsi, A.; Oh, T.H.; Lee, D.S. In-situ synthesis of bifunctional N-doped CoFe2O4/rGO composites for enhanced electrocatalysis in hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidenhans’l, A.A.; Regmi, Y.N.; Wei, C.; Xia, D.; Kibsgaard, J.; King, L.A. Precious Metal Free Hydrogen Evolution Catalyst Design and Application. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 5617–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bui, V.Q.; Lee, J.; Jadhav, A.R.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, M.G.; Kawazoe, Y.; Lee, H. Modulating Interfacial Charge Density of NiP2–FeP2 via Coupling with Metallic Cu for Accelerating Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Li, K.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, L.; Nicolosi, V.; Xiao, X.; Lee, J.M. Transition metal nitrides for electrochemical energy applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1354–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Niu, X.; Yin, H.; Yu, S.; Li, J. Synergistic effect of oxygen defects and hetero-phase junctions of TiO2 for selective nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2022, 636, 118596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.S.S.; Rusho, M.A.; Abilkasimov, A.; Latipova, M.; Aldulaimi, A.; Taki, A.G.; Albadr, R.J.; Taher, W.M.; Smerat, A.; Raja, M.R.; et al. Exploring transition metal-based electrocatalysts for carbon dioxide reduction: Towards enhanced product. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2025, 880, 142410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, A.; Gao, H.; Wang, G.; Yin, Y.; Che, L.; Gao, H. Boosting Oxygen Evolution Reaction Catalyzed by Transition Metal Carbides. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Tong, Y. Self-supporting Nickel Phosphide/Hydroxides Hybrid Nanosheet Array as Superior Bifunctional Electrode for Urea-Assisted Hydrogen Production. ChemCatChem 2022, 14, e202201047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ye, Q.; Wang, X.; Sheng, J.; Yu, X.; Zhao, S.; Zou, X.; Zhang, W.; Xue, G. Applying sludge hydrolysate as a carbon source for biological denitrification after composition optimization via red soil filtration. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Hu, M.; Yang, J. Heterostructure engineering of the Fe-doped Ni phosphides/Ni sulfide p-p junction for high-efficiency oxygen evolution. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 924, 166613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Guo, X.; Li, X. Design of molybdenum phosphide @ nitrogen-doped nickel-cobalt phosphide heterostructures for boosting electrocatalytic overall water splitting. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2023, 648, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; Liu, M.; Yue, N.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, W. Inverted-design for highly-active hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst of MoS2@Ni3S2 core-shell via unlocking the potential of Mo. Particuology 2023, 77, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Shen, X.; Wang, Y.; Hocking, R.K.; Li, Y.; Rong, C.; Dastafkan, K.; Su, Z.; Zhao, C. In Situ Reconstruction of V-Doped Ni2P Pre-Catalysts with Tunable Electronic Structures for Water Oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liao, L.; Bian, Q.; Yu, F.; Li, D.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Tang, D.; Zhou, H.; et al. Engineering In-Plane Nickel Phosphide Heterointerfaces with Interfacial sp H—P Hybridization for Highly Efficient and Durable Hydrogen Evolution at 2 A cm−2. Small 2021, 18, 2105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahuja, M.; Riyajuddin, S.; Afshan, M.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Sultana, J.; Maruyama, T.; Ghosh, K. Se-Incorporated Porous Carbon/Ni5P4 Nanostructures for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction with Waste Heat Management. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Cai, L.; Shi, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhong, S.; Lu, W. Phase engineering reinforced multiple loss network in apple tree-like liquid metal/Ni-Ni3P/N-doped carbon fiber composites for high-performance microwave absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 135009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Su, G.; Shi, Z.; Huang, M. Redistributing interfacial charge density of Ni12P5/Ni3P via Fe doping for ultrafast urea oxidation catalysis at large current densities. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Han, D.; Niu, L.; Ivaska, A. Nanoengineering Construction of Cu2O Nanowire Arrays Encapsulated with g-C3N4 as 3D Spatial Reticulation All-Solid-State Direct Z-Scheme Photocatalysts for Photocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 6367–6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, S.; Xiao, D.; Gong, M.; Liang, J.; Zhao, T.; Shen, T.; Wang, D. Hierarchical Bimetallic Ni-Co-P Microflowers with Ultrathin Nanosheet Arrays for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction over All pH Values. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 42233–42242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Tian, D.; Jiang, H.; Cao, D.; Wei, S.; Liu, D.; Song, P.; Lin, Y.; Song, L. Achieving Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction over a Ni5P4 Catalyst Incorporating Single-Atomic Ru Sites. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1906972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liang, K.; Zeng, Q.; Tang, L.; Yang, Y.; Song, J.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Hu, L.; Fang, Y. Rational fabrication of Ni2P-Ni12P5 heterostructure with built-in electric-field effects for high-performance urea oxidation reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 654, 159433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Cao, Q.; Du, J.; Zhao, L.; Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W. Ni-Ni3P nanoparticles embedded into N, P-doped carbon on 3D graphene frameworks via in situ phosphatization of saccharomycetes with multifunctional electrodes for electrocatalytic hydrogen production and anodic degradation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 261, 118147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zeng, F.; Song, X.; Sha, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Yu, M.; Jiang, C. In-situ growth of Ni(OH)2 nanoplates on highly oxidized graphene for all-solid-state flexible supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 456, 140947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, J.; Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Lin, J.; Fan, H.J.; Shen, Z.X. A Flexible Alkaline Rechargeable Ni/Fe Battery Based on Graphene Foam/Carbon Nanotubes Hybrid Film. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 7180–7187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.-Z.; Fan, R.-Y.; Yu, N.; Zhou, Y.-N.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Dong, B.; Yan, Z.-F. Facile Synthesis of Ni(OH)2 through Low-Temperature N-Doping for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts 2024, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Gao, M.; Duan, G.; Cao, F. In-Situ Construction of Fe-Doped NiOOH on the 3D Ni(OH)2 Hierarchical Nanosheet Array for Efficient Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Materials 2024, 17, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jang, Y.; Yoon, G.; Lee, S.; Ryu, G.H. Synthesis and electrochemical evaluation of nickel hydroxide nanosheets with phase transition to nickel oxide. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 10172–10181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhong, J.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y. Interface Engineering Induced N, P-Doped Carbon-Shell-Encapsulated FeP/NiP2/Ni5P4/NiP Nanoparticles for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Coatings 2024, 14, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebiri, Z.; Debbache, N.; Sehili, T. Sheet-like g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of naproxen. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 446, 115189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Lu, B.; Yan, X.; Deng, Z.; Chang, C.; Zhou, K. Geometric Structure-Dependent Catalyst Performance in CH4 Reforming Using Ni-Based Catalysts. Catalysts 2025, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, H.; Liu, S.; Zheng, J. Enhancing Water Splitting Performance via NiFeP-CoP on Cobalt Foam: Synergistic Effects and Structural Optimization. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X. N-Doped carbon shelled bimetallic phosphates for efficient electrochemical overall water splitting. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 22787–22791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, U.; Tahira, A.; Mazzaro, R.; Morandi, V.; Ishaq Abro, M.; Baloch, M.M.; Yu, C.; Ibupoto, Z.H. Nickel–cobalt bimetallic sulfide NiCo2S4 nanostructures for a robust hydrogen evolution reaction in acidic media. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 22196–22203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.Y.; Jeong, D.I.; Ha, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, H.; Yoo, J.H.; Choi, H.G.; Kim, H.Y.; Kang, B.K.; Park, Y.S.; et al. Fine-tunable N-doping in carbon-coated CoFe nano-cubes for efficient hydrogen evolution in AEM water electrolysis. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 2025, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Huang, L.; Yu, Y.; Sun, D.; Qu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wen, J.; Su, Q.; Meng, F.; Du, G.; et al. Crystalline CoP@ Amorphous WP2 Coaxial Nanowire Arrays as Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Water Splitting. Small 2025, 21, e2412689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, A. Rational Design of Self-Supported Ni3Fe–Ni3P/NF Electrocatalyst for pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 19411–19421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.; Shin, D.; Kim, H.; Song, H.; Choi, S.-I. FexNi2–xP Alloy Nanocatalysts with Electron-Deficient Phosphorus Enhancing the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Acidic Media. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11665–11673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Niederberger, M.; Tervoort, E.; Mei, J.; Peng, D.L. Self-Assembled Preparation of Porous Nickel Phosphide Superparticles with Tunable Phase and Porosity for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2024, 20, e2309435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.