Abstract

Blue calcite mineral formations occurring within Paleozoic marbles of Central Anatolia have been investigated in terms of their mineralogical and geochemical characteristics, as well as their potential for use as ornamental stones or decorative objects. XRD analyses of samples with different color tones (white, grayish-blue, and blue) revealed that the white sample contains only calcite, the grayish-blue samples include calcite and dolomite, while the blue sample contains calcite and quartz. XRF and ICP-MS analyses indicate a marked enrichment of trace elements such as Fe, Cr, and Ni in the blue sample, and Mn and Fe in the grayish-blue samples, suggesting these elements may influence the observed color variations. The presence of dolomite in grayish-blue samples and quartz in the blue sample corresponds to elevated MgO and SiO2 contents, respectively. Based on their distinct colors, textures, transparency, and other aesthetic properties, the grayish-blue and blue marbles show significant potential for use as decorative stones or ornamental objects.

1. Introduction

Calcite is one of the most abundant carbonate minerals in nature, with the chemical formula CaCO3 (calcium carbonate), and it exhibits a wide range of colors and textural features [1]. This mineral occurs in significant quantities within sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. The color variations of calcite (white, black, yellow, orange, blue, etc.) largely depend on the presence of trace elements incorporated into the crystal lattice, organic residues, and radiation-induced color centers. Handin (1957) [2] reported that Yule marbles exposed to gamma radiation showed a color transition from white to bright blue due to deformation, with the intensity of coloration depending on both the direction and degree of deformation. In this process, the formation of CO33− color centers associated with dislocations and twinning structures was suggested to play a key role in blue coloration [2,3].

Blue calcite is a rare variety of calcite characterized by translucent to semi-transparent shades ranging from grayish-pale blue to light navy. Due to its aesthetic appeal, it is often used in decorative objects and ornamental stone applications. Its coloration is associated with trace amounts of transition metals and heavy elements such as Fe, Ni, Mn, Cu, Sr, Ba, V, and Co incorporated into the crystal lattice, as well as possible contributions from organic matter [4,5,6,7,8].

Globally, occurrences of blue calcite have been identified in various geological environments, including California, USA [9,10]; Eastern Ontario and New York, USA [11]; Western Quebec and Eastern Ontario, Canada [11]; Madagascar [6]; Tamil Nadu, India [12]; Estremoz, Portugal [7,13]; Italy [14]; Delos Island, Greece [15]; and in Türkiye, notably in Denizli [16] and İzmir [17,18].

The Central Anatolia region of Türkiye represents a significant geological belt rich in natural stone resources such as marble, granite, and travertine [19,20,21]. The white marbles of the region were extensively used by ancient civilizations in architectural structures [22,23], artworks [24], and both functional and ornamental objects [25]. However, there is no archaeological or written evidence indicating the historical use of blue calcite from the Kırşehir area in any ancient structures.

Although rare in nature, blue calcites have been used in limited amounts in Anatolia for their visual appeal, both in historical architecture [16,18,26,27] and in decorative artifacts [28,29,30]. Today, blue calcite continues to be used in modern artworks [31,32]. Nevertheless, aside from the İzmir [17,18] and Denizli [16] regions, there are no existing records in the literature concerning the geological origin or source areas of blue calcite occurrences in Anatolia. Therefore, elucidating the mineralogical, geochemical, and color formation mechanisms of blue calcites from the Kırşehir region holds both scientific and industrial significance.

2. Materials and Methods

Representative calcite-bearing marble samples were collected from several localities within the Kırşehir region, Central Anatolia, Türkiye, to investigate their mineralogical and geochemical characteristics. All analytical procedures were performed following standard laboratory protocols to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility. Thin sections were prepared and examined under a bottom-illuminated polarizing microscope in Mineralogy–Petrography Laboratory in Department of Geological Engineering in Kırşehir Ahi Evran University. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were performed on unoriented powdered samples over a 2θ range of 5–90°, using a Panalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Worcestershire, England) at the Erciyes University Technology Research and Application Center in Kayseri in Türkiye. Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (WD-XRF) analyses were conducted on pressed powder pellets using a Panalytical Axios Advanced wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Worcestershire, England) at the same laboratory to determine the major oxide compositions of the samples. Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry (ICP–MS) analyses were carried out on acid-digested solutions of the powdered samples using an Agilent 7500A ICP–MS (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, United States) instrument at the Erciyes University Technology Research and Application Center, in Kayseri in Türkiye, in order to determine the trace and rare element concentrations.

3. Geology and Field Setting

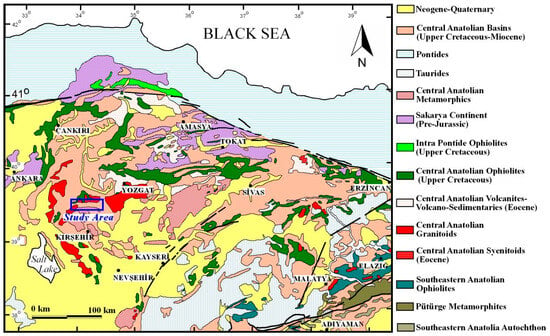

The Central Anatolia Region, where the study area is located, hosts numerous geological units that differ in age, geotectonic position, and lithological characteristics [33] (Figure 1). The region forms part of a north–south-trending geological section extending from the Black Sea in the north to Central Anatolia in the south and consists of continental blocks separated by ophiolitic suture zones. These tectonic belts are, from north to south, identified as the Pontide Continent, the Intra-Pontide Suture Zone, the Sakarya Continent, the Ankara–Yozgat–Erzincan Suture Zone (Central Anatolian Ophiolites), and the Kırşehir Continent (Central Anatolian Metamorphics). These continental blocks developed through the Pan-African, Hercynian, and Cimmerian orogenic events and preserved their continental character throughout the Neo-Tethyan oceanic evolution of the region [34].

Figure 1.

Regional geological map of the study area and its surroundings (adopted from Başıbüyük, 2006) [33].

The Neo-Tethys Ocean opened during the Liassic period as a result of rifting along two distinct zones within these continental foundations, leading to the development of the Intra-Pontide and Ankara–Yozgat–Erzincan oceanic branches [35]. By the Early Late Cretaceous, the Intra-Pontide Ocean began to subduct northward beneath the Pontide Continent, while the Ankara–Yozgat–Erzincan Ocean started to subduct beneath the Sakarya Continent in the west and the Pontide Continent in the east [34]. By the end of the Late Cretaceous, complete closure of these oceanic basins resulted in ophiolite emplacement, and the compressional tectonic regime responsible for this closure continued to be effective until the end of the Paleogene [34].

The North Anatolian Ophiolites represent allochthonous units of the northern branch of the Neo-Tethys Ocean and were emplaced southward onto the Tauride–Anatolide Platform during the Late Cretaceous–Paleocene [36] or Late Cretaceous [37]. Following the complete closure of the Neo-Tethys during the Eocene, vertical tectonic movements became dominant across the region, accompanied by the development of magmatic rocks of acidic, intermediate, and basic compositions [38]. Collision-related magmatism led to the formation of the Central Anatolian Granitoids during the Paleocene [39], the Central Anatolian Syenitoids during the Middle–Late Eocene [40], and the Central Anatolian Volcanic Rocks.

Concurrently with the closure of the Neo-Tethys, the Central Anatolian Basins began to develop over the Sakarya Continent and the Kırşehir Block from the Late Cretaceous onward [35], and they continued to evolve until the Middle Miocene [41,42]. Beginning in the Middle Miocene, the region came under the influence of the neotectonic “basin” regime characteristic of this period [43,44], during which intracratonic basins were formed [42]. This tectonic regime persisted until the Late Pliocene [41].

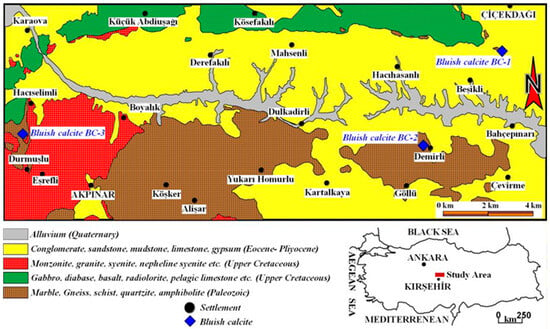

The oldest units exposed in the study area are the Paleozoic Central Anatolian Metamorphics, composed of marble, gneiss, schist, quartzite, and amphibolite (Figure 2). This high-grade metamorphic rock assemblage constitutes the basement of the region. Overlying these metamorphics along a tectonic contact are the Upper Cretaceous Central Anatolian Ophiolites, which represent allochthonous rock assemblages belonging to the Neo-Tethys Ocean. The ophiolitic sequence was later intruded by Upper Cretaceous intrusive rocks through thermal contact, and in some places, these intrusions penetrated the metamorphic basement. These intrusive rocks, collectively known as the Central Anatolian Syenitoids and Granitoids, consist of plutonic rocks of varying compositions such as monzonite, granite, syenite, and nepheline syenite. All of these units are unconformably overlain by Eocene–Quaternary marine and continental sedimentary sequences [45,46,47].

Figure 2.

Geological map of the study area (adopted from MTA, 1990; MTA, 1991) [46,47].

In the northeastern part of the study area, in the southern section of Çiçekdağı, dark grayish-blue marbles (BC-1) are observed, forming a very limited outcrop within a narrow local extent (Figure 2). This unit consists of coarse-crystalline, well-cleaved calcite crystals and lacks any apparent foliation plane. Lithologically, these marbles exhibit a massive texture and a homogeneous crystalline structure characterized by an equigranular granoblastic texture. The coarse-grained texture of the calcite crystals indicates that the unit has undergone a high degree of recrystallization (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Field (a) and close-up (The 50 Turkish kuruş coin was used as the scale) (b,c) views of dark grayish-blue marble (BC-1), southern Çiçekdağı.

In the southeastern part of the study area, west of Demirli Village, light grayish-blue calcite (BC-2) occurrences are exposed over a wider area, covering several square kilometers (Figure 2). These marbles are composed of coarse-crystalline, highly cleaved calcite crystals and exhibit distinct foliation planes (Figure 4). They display a granoblastic texture and, in places, microfold structures.

Figure 4.

Field (a) and close-up (b,c) views of light grayish-blue marble (BC-2), west of Demirli.

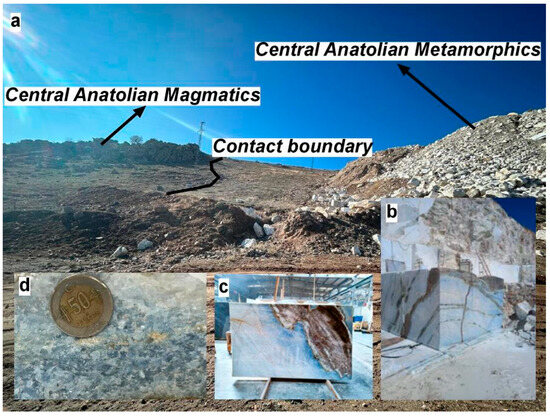

In the western part of the area, north of Durmuşlu Village, the marbles are rich in blue-colored calcite (BC-3) (Figure 2). These marbles are cut by plutonic rocks belonging to the Central Anatolian Magmatic Complex through thermal contact (contact metamorphism) (Figure 5). Blue calcite occurs very close to this contact zone, and the observed color variation is thought to be related to temperature effects and hydrothermal fluid circulation. The marbles exhibit coarse-crystalline, well-cleaved, granoblastic textures, and locally show distinct calcite twinning.

Figure 5.

Field (a,b) and close-up (The 50 Turkish kuruş coin was used as the scale) (c,d) views of blue marble (BC-3), north of Durmuşlu.

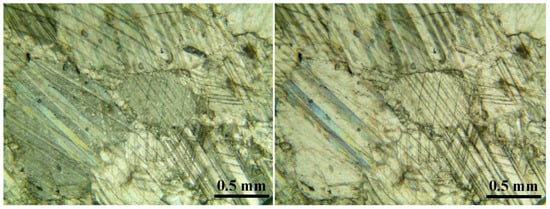

In the southern part of the study area, around Alişar Village, white marbles (BC-4) are observed (Figure 2). These marbles are composed of coarse-crystalline, well-cleaved calcite crystals (Figure 6) and display a hard, compact, and massive appearance. Structurally, they are non-foliated and homogeneous. The calcite crystals exhibit high optical purity and well-developed rhombohedral twinning. Thin section analysis of white marbles has revealed that, for example, they consist entirely of coarse calcites. These calcites exhibit polysynthetic twinning and bidirectional cleavage (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Field (a) and close-up (The 1 Turkish lira coin was used as the scale) (b,c) views of white marble (BC-4), south of Alişar.

Figure 7.

The thin section views of white marble (BC-4), south of Alişar (+N cross-polarized light (left); //N plain-polarized light (right)).

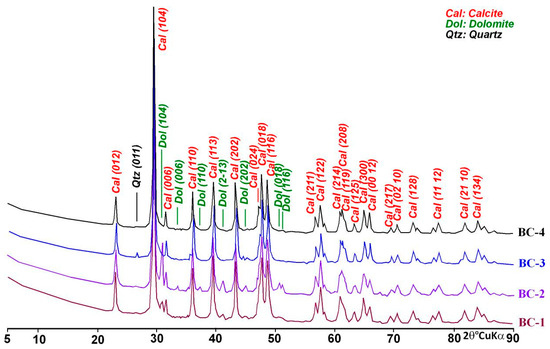

According to the XRD analysis results, the white-colored sample from the region (BC-4) consists entirely of pure calcite. The grayish-blue samples (BC-1 and BC-2) contain a mineral assemblage of calcite and dolomite, whereas the blue-colored sample includes a combination of calcite and quartz minerals (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the marble samples.

4. Geochemistry

The XRF and ICP-MS analytical results of the white, grayish-blue, and blue calcite samples show consistent trends when evaluated together with the XRD data. Compared to the pure calcite sample, the samples containing quartz and dolomite display a distinct increase in SiO2 and MgO contents, as expected (Table 1).

Table 1.

XRF and ICP-MS analytical results of grayish-blue, blue, and white calcite samples.

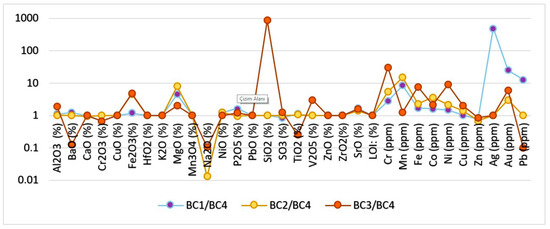

To determine the cause of the color variations, the major and trace element compositions of the grayish-blue and blue calcite samples were normalized to the chemical composition of the white, pure calcite mineral (Figure 9). The findings indicate that the grayish-blue samples (BC-1 and BC-2) exhibit internally consistent distributions, except for the elements Ag, Au, and Pb. In these samples, enrichment was observed in Fe2O3, SrO, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ag, and Au contents, while depletion was detected in Na2O and Zn contents.

Figure 9.

Normalized diagram of grayish-blue and blue calcite samples relative to white calcite (BC-1 and BC-2: grayish-blue; BC-3: blue; BC-4: white).

In the blue-colored sample (BC-3), enrichment was detected in the major oxides Fe2O3, MgO, V2O5, and SrO, whereas depletion occurred in BaO, Na2O, and TiO2. In terms of trace elements, enrichment was observed in Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Au, while Pb showed depletion.

5. Conclusions

Mineralogical and geochemical investigations indicate that the color variations observed in the calcite samples from the study area are closely related to their mineral compositions and trace element enrichments.

XRD analyses revealed that the white sample (BC-4) consists entirely of pure calcite; the grayish-blue samples (BC-1 and BC-2) contain a calcite–dolomite assemblage; and the blue sample (BC-3) includes a calcite–quartz assemblage. These mineralogical distinctions are consistent with the chemical compositional variations determined by XRF and ICP-MS analyses.

Examination of the major oxide compositions shows that CaO contents in all samples range between 52% and 55%, confirming calcite as the dominant component. The significantly higher MgO concentrations in the grayish-blue samples (1.44% and 2.57%) compared to the white sample (0.32%) clearly support the presence of dolomite. In the blue sample (BC-3), the SiO2 content measured at 0.877% provides geochemical confirmation of the quartz contribution. The major oxide contents in the samples are consistent with the mineral association determined by XRD analysis.

The distribution of trace elements plays a key role in understanding the coloration mechanisms. In the grayish-blue samples (BC-1 and BC-2), enrichment was detected in Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ag, and Au; notably, the elevated Mn (14.6–25.71 ppm) and Fe (3.2–4.25 ppm) concentrations indicate their influence on color formation. The blue sample (BC-3) shows enrichment in Cr (3.39 ppm), Fe (14.31 ppm), Ni (4.39 ppm), Cu (0.78 ppm), and Au (0.006 ppm), while Pb (0.001 ppm) and Zn (5.59 ppm) remain relatively low. These results suggest that blue coloration is primarily associated with the incorporation of transition metals such as Fe, Ni, Cr, and Cu within the crystal lattice.

Previous studies in the literature support these findings. García-Guinea et al. (2015) [6] reported that blue coloration in calcite is related to Sr, Ba, V, and Ni; Wiersema (1960) [5] and Medlin (1959) [4] associated it with Mn and Pb; and Ponnusamy et al. (2004) [12] linked it to Mn enrichment. Therefore, it can be concluded that the blue hues in the study area are mainly attributed to the presence of transition metals (Fe, Mn, Ni, Cr, and Cu).

Within Paleozoic marbles that developed under similar geological and evolutionary conditions (namely regional metamorphism and orogeny), distinct differences emerge among white, blue, and bluish-gray calcite varieties when evaluated in conjunction with mineralogical and geochemical findings. According to X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses, the white calcite sample is composed entirely of pure calcite phase. The negligible concentrations of major oxides (e.g., MgO, Fe2O3) and trace elements (Fe, Mn, Ni, Cr, Cu, etc.) indicate an absence of chemical heterogeneity capable of inducing coloration. In contrast, the blue calcite samples display both the presence of quartz and a notable enrichment in transition metals such as Fe, Ni, Cr, and Cu. This enrichment is directly associated with hydrothermal fluid circulation that developed during the emplacement of the Late Cretaceous Central Anatolian magmatic intrusions into the marble sequence. The diffusion of these trace elements into the calcite lattice within recrystallization zones under the influence of such hydrothermal fluids is observed to be the principal factor contributing to the development of the blue coloration. The bluish-gray calcite samples, on the other hand, are characterized mineralogically by the presence of dolomite and geochemically by a pronounced enrichment in Mn. These features indicate that the bluish-gray calcites crystallized under metamorphic and chemical conditions different from those of the blue calcites. In particular, the incorporation of Mn2+ and Fe2+/3+ ions into the crystal lattice plays a dominant role in the observed coloration of these samples.

Additionally, it is considered that the twinning, dislocations, and development of color centers within the crystals of both blue and bluish-gray calcites may have formed during the tectonic deformations associated with the Alpine orogenies. These structural defects are interpreted to have interacted with trace elements to produce optical color centers, thereby influencing the observed color variations.

In conclusion, the color diversity observed in the Paleozoic marbles of the study area can be primarily explained by the combined effects of trace-element enrichment (Fe, Mn, Ni, Cr, Cu), hydrothermal fluid activity, the presence of dolomite, and microstructural defects induced by tectonic deformation. These findings demonstrate that the blue and bluish-gray coloration in calcite is the result of a complex interplay between geochemical and structural metamorphic processes.

The aesthetic appearance and rarity of blue calcite make it a potentially valuable raw material for decorative and ornamental use. However, properties such as low hardness (Mohs 3), perfect cleavage, and chemical reactivity can limit its range of applications. To enhance long-term durability, reinforcement with epoxy- or polyester-based resins is recommended. Such treatments could expand the aesthetic and economic potential of these minerals for broader industrial and artistic applications.

Author Contributions

Experimental design, İ.K.A.; methodology, Z.B. and İ.K.A.; data curation, Z.B. and İ.K.A.; data analysis, Z.B. and İ.K.A.; writing—original draft, Z.B. and İ.K.A.; writing—review and editing, Z.B. and İ.K.A.; supervision, Z.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reeder, R.J. (Ed.) Carbonates: Mineralogy and Chemistry (Reviews in Mineralogy); Mineral Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; Volume 11, p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- Handin, J.; Higgs, D.V.; Lewis, D.R.; Weyl, P.K. Effects of gamma radiation on the experimental deformation of calcite and certain rocks. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1957, 68, 1203–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, T.; Aguilar, M.; Coy-Yll, R. Relationship between blue color and radiation damage in calcite. Radiat. Eff. 1983, 76, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, W.L. Thermoluminescent properties of calcite. J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 30, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, A. Experiments on Color Centers in Crestmore Blue Calcite. Master’s Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- García-Guinea, J.; Correcher, V.; Benavente, D.; Sanchez-Moral, S. Composition, luminescence, and color of a natural blue calcium carbonate from Madagascar. Spectrosc. Lett. 2015, 48, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.P.; de Oliveira, D.; Veiga, J.P.; Lisboa, V.; Carvalho, J.; Barreiros, M.A.; Coutinho, M.L.; Salas-Colera, E.; Vigário, R. Contribution to the understanding of the colour change in bluish-grey limestones. Heritage 2022, 5, 1479–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voudouris, P.; Melfos, V.; Tarantola, A. A Field Guide on the Geology, Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Lavrion ore Deposit, Attica, Greece; University of Lorraine: Nancy, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenholtz, J.L.; Smith, D.T. Crestmore sky blue marble: Its linear thermal expansion and color. Am. Mineral. 1950, 35, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, C.W. Contact metamorphism of magnesian limestones at Crestmore, California. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1959, 70, 879–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.F.; Schumann, D.; de Fourestier, J. The clusters of accessory minerals in Grenville marble crystallized from globules of melt. In Proceedings of the Book of Abstracts, Proceedings of the CAM-2017: Conference on Accessory Minerals, Vienna, Austria, 13–17 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy, V.; Ramasamy, V.; Dheenathayalu, M.; Hemalatha, J. Effect of annealing in thermostimulated luminescence (TSL) on natural blue colour calcite crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2004, 217, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menningen, J.; Siegesmund, S.; Lopes, L.; Martins, R.; Sousa, L. The Estremoz marbles: An updated summary on the geological, mineralogical and rock physical characteristics. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, G.; Pieruccioni, D. Geological characterization of the marble commercial varieties outcropping in the Frigido Valley (Apuan Alps, Italy). Geoheritage 2020, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettor, T.; Sautter, V.; Jolivet, L.; Moretti, J.C.; Pont, S. Marble quarries in Delos Island (Greece): A geological characterization. BSGF–Earth Sci. Bull. 2022, 193, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L. Regional marble quarries. The Aphrodisias Regional Survey; Ratté, C., de Staebler, P., Aphrodisias, V., Eds.; Verlag Philipp von Zabern: Darmstadt, Germany, 2012; pp. 165–201. [Google Scholar]

- Adak, M.; Kadıoğlu, M. Die Steinbrüche von Teos und «Marmor Luculleum». Philia 2017, 3, 1–43. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Şişman Tükel, F.; Aysal, N.; Yildirim, İ.D.; Guillong, M.; Uysal, T.; Öngen, S.; Erdem, E. U–Pb calcite geochronology, EPR, geochemistry, and C–O–Sr isotopes of Africano marbles in Seferihisar (İzmir, Türkiye). Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2025, 34, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavumirza, M.; Kılıç, Ö.; Mesut, A. Mucur (Kirşehir) Yöresi Kireçtaşi Mermerleri Ve Travertenlerinin Fiziko-Mekanik Özellikleri. In Türkiye IV. Mermer Sempozyumu (Mersem’2003) Bildiriler Kitabi, Ankara, Turkey, 18–19 Aralık 2003; TMMOB Maden Mühendisleri Odası: Ankara, Türkiye, 2003. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Ekincioğlu, G.; Başıbüyük, Z.; Ekdur, E.; Ballı, F.; ve Kanbir, E.S. Kırşehir Doğal Taş Sektörü Analizi ve Yatırım Fırsatları Raporu; Kırşehir Sanayi ve Ticaret Odası: Kırşehir, Türkiye, 2014. Available online: https://ahika.gov.tr/assets/ilgilidosyalar/Kirsehir-Dogal-Tas-Sektor-Analizi-ve-Yatirim-Imkanlari-Raporu.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026). (In Turkish)

- Başıbüyük, Z.; Ekincioğlu, G. Usability of the leucitites in the Kırşehir (Akpınar) region as facing stone. Gümüşhane Univ. J. Sci. 2019, 9, 655–663. [Google Scholar]

- Zöldföldi, J.; Satır, M. Provenance of the white marble building stones in the monuments of Ancient Troia. In Troia and the Troad: Scientific Approaches; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Başıbüyük, Z.; Ekincioğlu, G.; Önal, M.M. Natural building stones used in the Yozgat Sarıkaya Thermal Roman Bath and their engineering properties. Çukurova Univ. J. Fac. Eng. Archit. 2019, 34, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Akçay, A. A general evaluation on the Tabal sculptural works. Ank. Hacı Bayram Veli Univ. Fac. Lett. J. 2020, 1, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baysal, E.L. Neolithic period personal ornaments: New approaches and recent research in Turkey. TÜBA-AR J. Archaeol. 2015, 18, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, O. From the Dipteros of Polykrates to the Pseudodipteros of Hermogenes. Anadolu 2012, 38, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yeşilbaş, E. Portal design and ornamentation in mosques and madrasas of Mardin (13th–15th centuries). Mukaddime 2020, 11, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durna, G.E. An analysis of the Knidian character—From the visible to the invisible. Belleten 2009, 73, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, M.; Bamyacı, O. Early Bronze Age mace head blanks from Maydos Kilisetepe: Typology and spatial use. TÜBA-AR J. Archaeol. 2020, 26, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girginer, K.S. Thoughts on a group of stone artifacts preserved in the Kahramanmaraş Museum. Çukurova Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Inst. 2022, 31, 573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman, Ö. The new paradigm of contemporary art: Situational aesthetics. Tykhe J. Art Des. 2020, 5, 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- İba, Ş.M. The phenomenon of pastiche in contemporary sculpture: The example of Daniel Arsham. RumeliDE J. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2024, 40, 462–477. [Google Scholar]

- Başıbüyük, Z. Eosen Volkaniklerinin Hidrotermal Alterasyon Mineralojisi-Petrografisi ve Jeokimyası: Zara-İmranlı-Suşehri-Şerefiye Dörtgeni’nden Bir Örnek (Sivas kuzeydoğusu, İç-Doğu Anadolu, Türkiye). Doktora Tezi, Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi, Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Sivas, Türkiye, 2006. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Tüysüz, O. A Geotraverse from the Black Sea to the Central Anatolia: Tectonic evolution of the Northern Neo-Tethys. Türkiye Petrol Jeologları Derneği Bülteni 1993, 5, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Yılmaz, Y. Tethyan evolution of Turkey: A plate tectonic approach. Tectonophysics 1981, 75, 181–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A. Fundamental geological features and structural evolution of the area between the Upper Kelkit River and the Munzur Mountains. Bull. Geol. Soc. Turk. 1985, 28, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Göncüoğlu, M.C.; Dirik, K.; Kozlu, H. Pre-Alpine and Alpine terranes in Turkey: Explanatory notes to the Terrane Map of Turkey. Ann. Géol. Pays Hell. 1997, 37, 515–536. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, A.; Okay, A.; Bilgiç, T. Fundamental Geological Characteristics and Results of the Upper Kelkit River Region and Its Southern Area, 1985; MTA Report No. 7777. 124p, (unpublished).

- Boztuğ, D. S-I-A-type intrusive associations: Geodynamic significance of the synchronism between metamorphism and magmatism in Central Anatolia, Turkey. In Tectonics and Magmatism in Turkey and the Surrounding Area (Geological Society Special Publication No. 173); Geological Society: London, UK, 2000; pp. 441–458. [Google Scholar]

- Boztuğ, D.; Yılmaz, S.; Kesgin, Y. Petrography, geochemistry, and petrogenesis of the eastern part of the Kösedağ pluton (Suşehri–NE Sivas) in the Inner–Eastern Anatolian alkaline province. Türk. Jeol. Bül. 1994, 37, 1–14. Available online: https://tjb.jmo.org.tr/detail-article.php?articlekod=742&lg=en (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Koçyiğit, A. An example of an accretionary forearc basin from northern central Anatolia and its implications for the history of subduction of Neo-Tethys in Turkey. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1991, 103, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görür, N.; Tüysüz, O.; Şengör, A.M.C. Tectonic evolution of the Central Anatolian Basins. Int. Geol. Rev. 1998, 40, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C. The North Anatolian transform fault: Its age, offset, and tectonic significance. J. Geol. Soc. 1979, 136, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, E. 1:2,000,000 Scale Geological Map of Turkey; Mineral Research and Exploration Publication: Ankara, Turkey, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Seymen, İ. Stratigraphy and metamorphism of the Kırşehir Massif around Kaman (Kırşehir). TJK Bull. 1981, 24, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- MTA. 1:100.000 Ölçekli Açınsama Nitelikli Türkiye Jeoloji Haritaları Serisi, Kırşehir–I32 Paftası; MTA Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 1991. Available online: https://eticaret.mta.gov.tr/index.php?route=product/product&product_id=17819 (accessed on 1 January 2026). (in Turkish)

- MTA. 1:100.000 Ölçekli Açınsama Nitelikli Türkiye Jeoloji Haritaları Serisi, Kırşehir–J32 Paftası; MTA yayınları Ankara, Türkiye, 1990. Available online: https://eticaret.mta.gov.tr/index.php?route=product/product&path=2_7&product_id=17857 (accessed on 1 January 2026). (in Turkish)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.