Adjustable Cryogenic Near-Zero Thermal Expansion and Magnetic Properties in Antiperovskite Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Preparation

2.2. Materials Characterization

3. Results

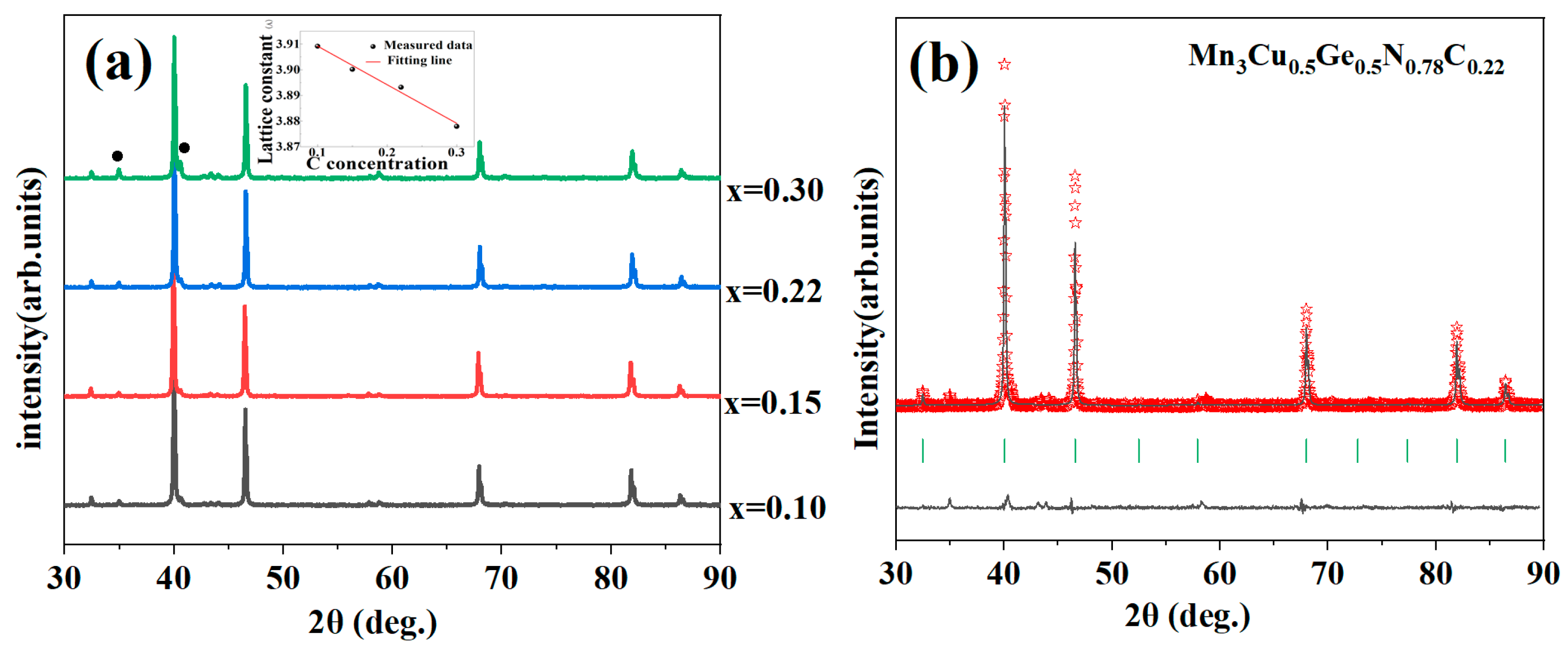

3.1. Phase Analysis

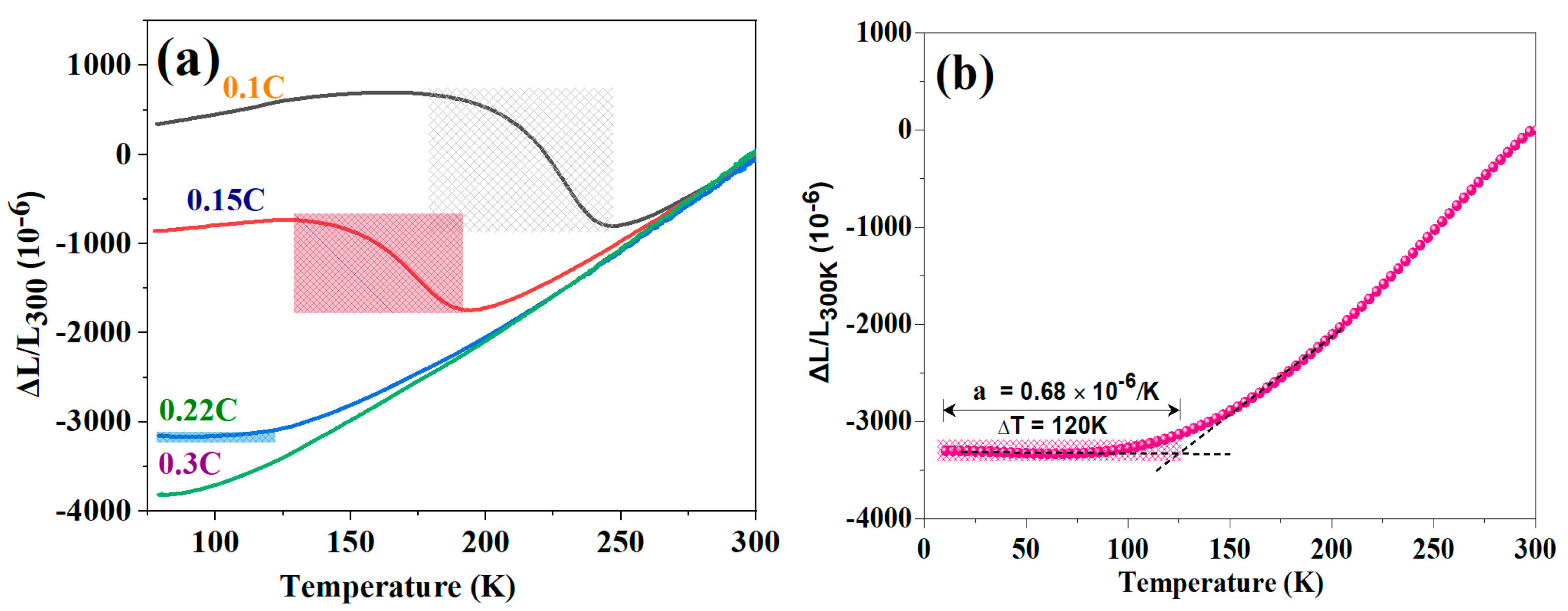

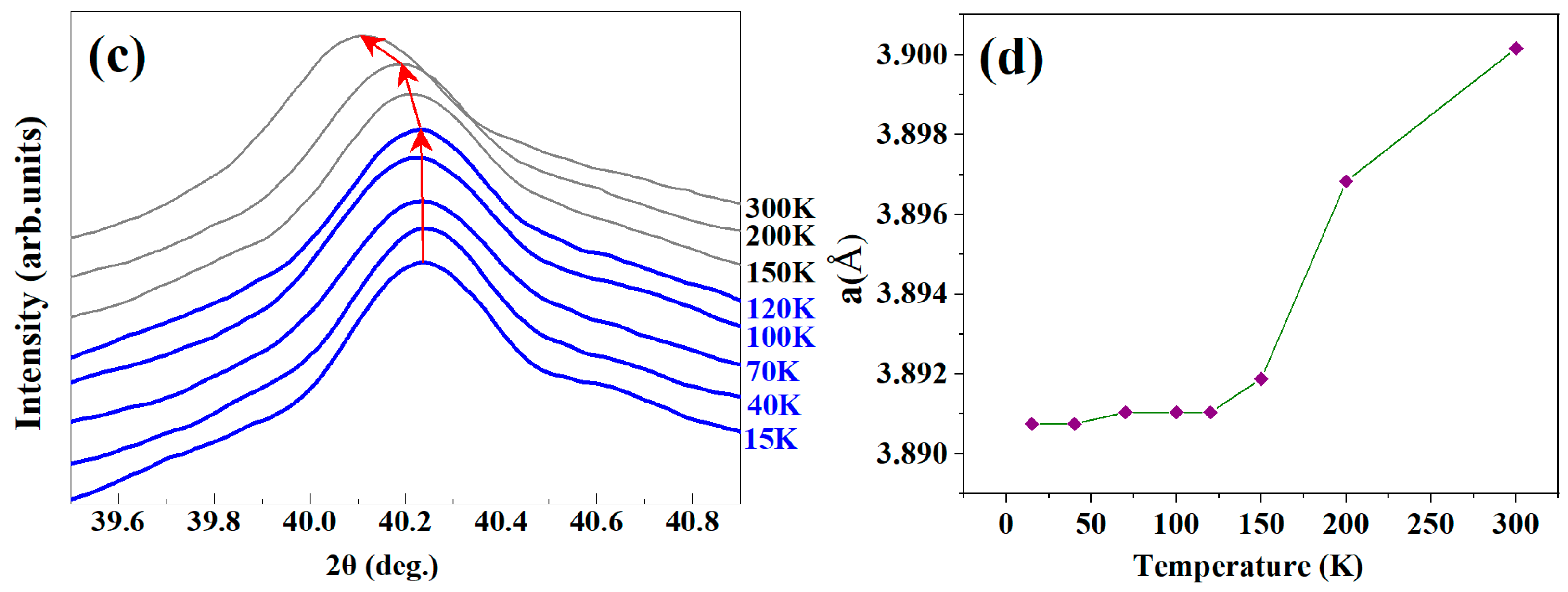

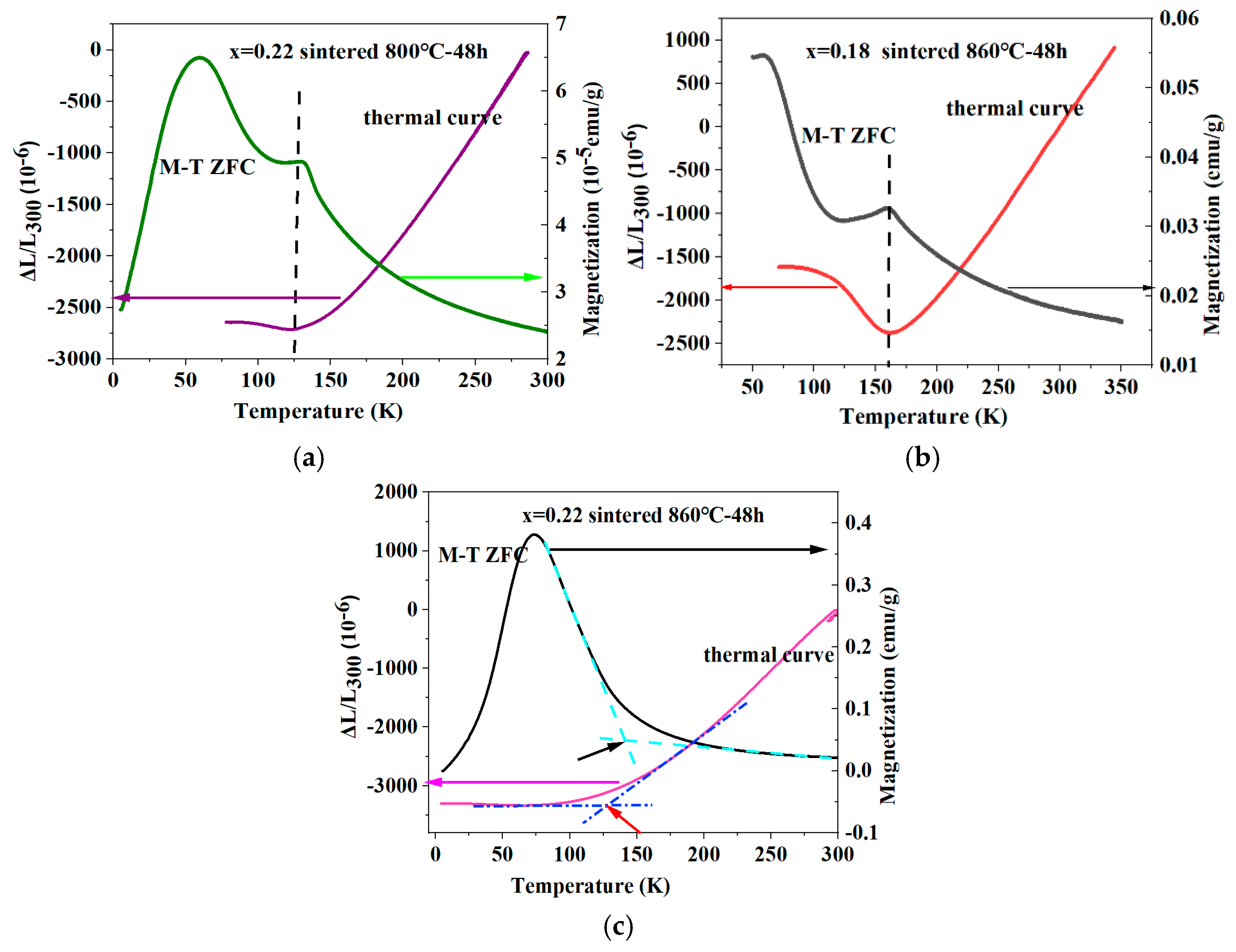

3.2. Thermal Expansion

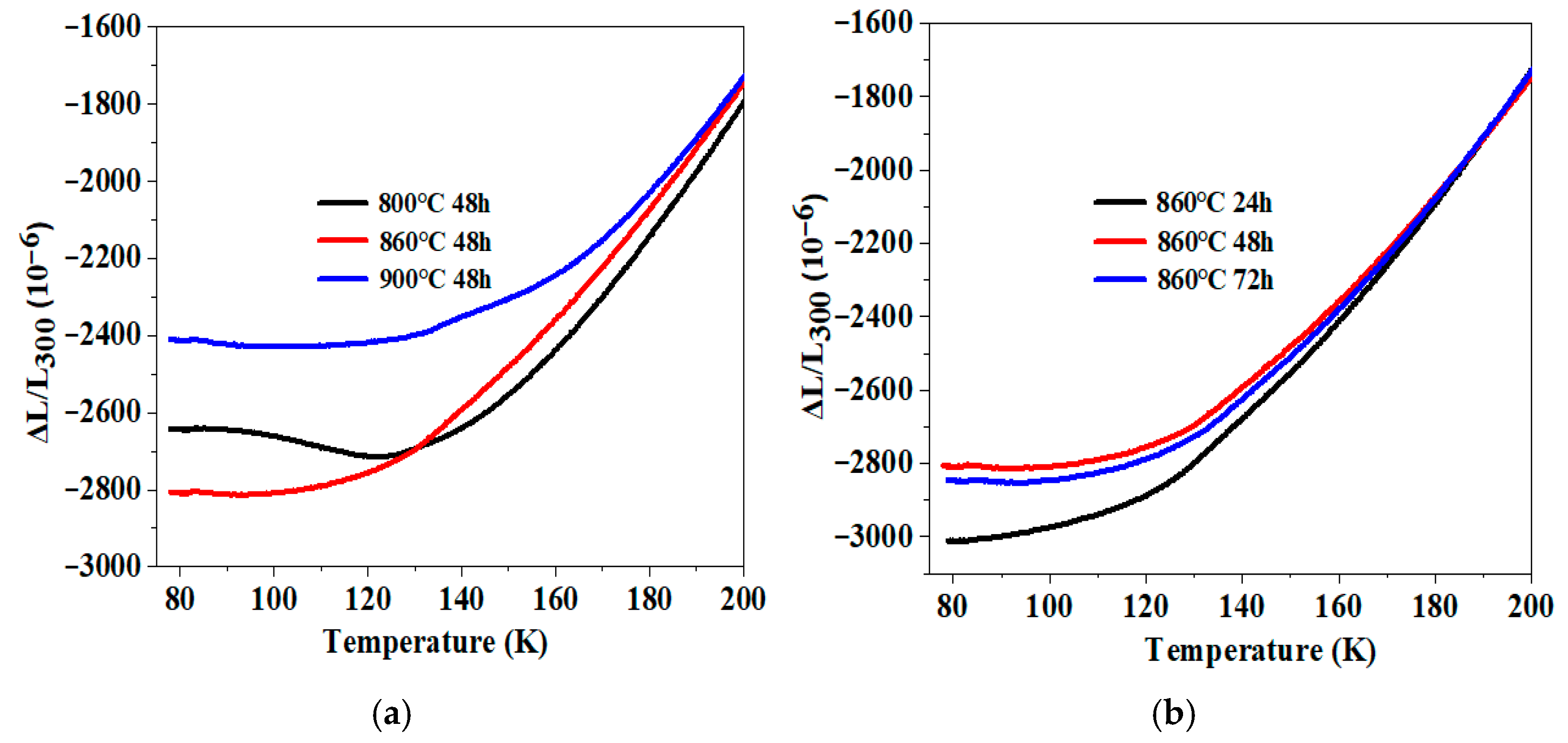

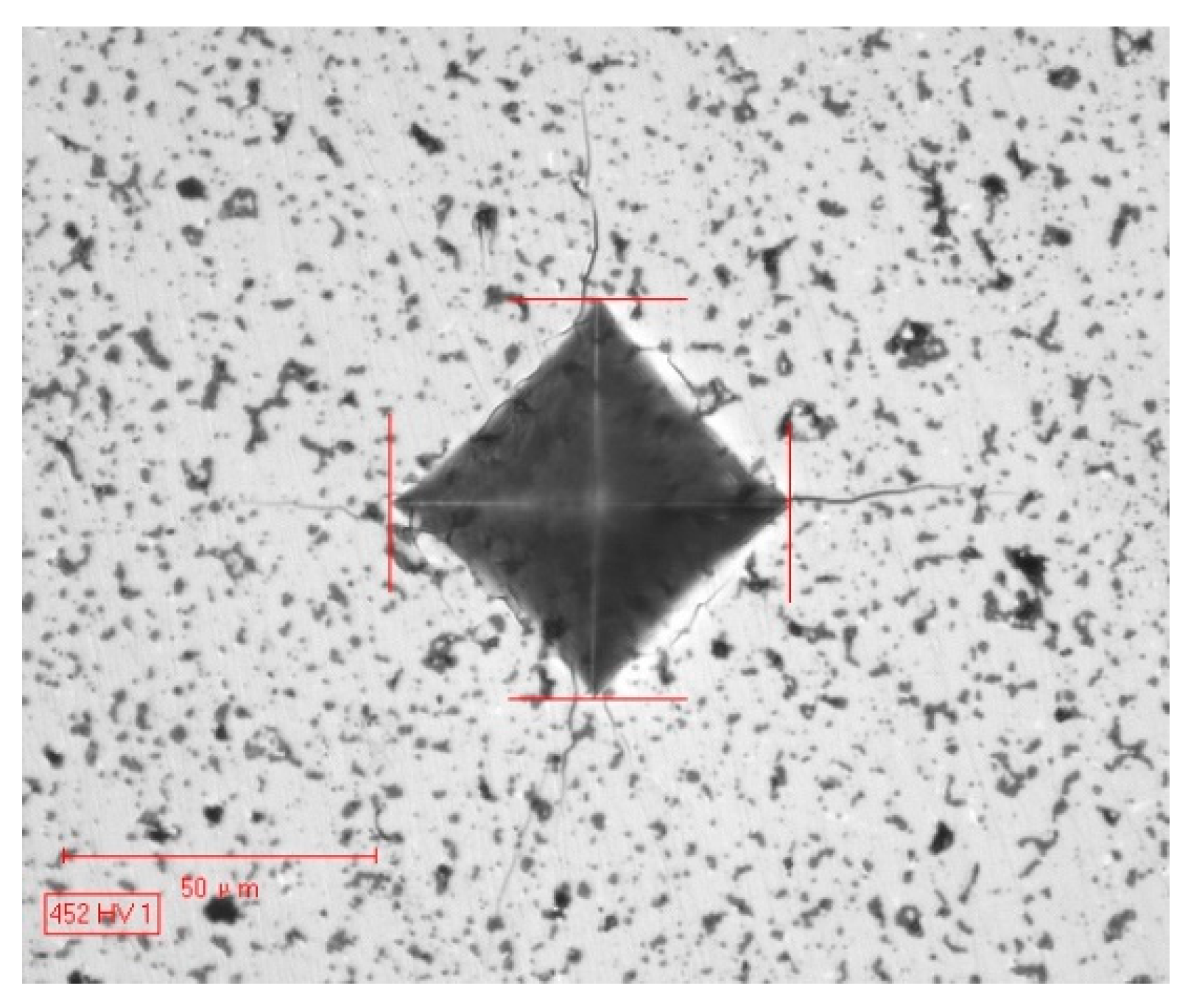

3.3. Zero Thermal Expansion Behavior and Mechanical Properties

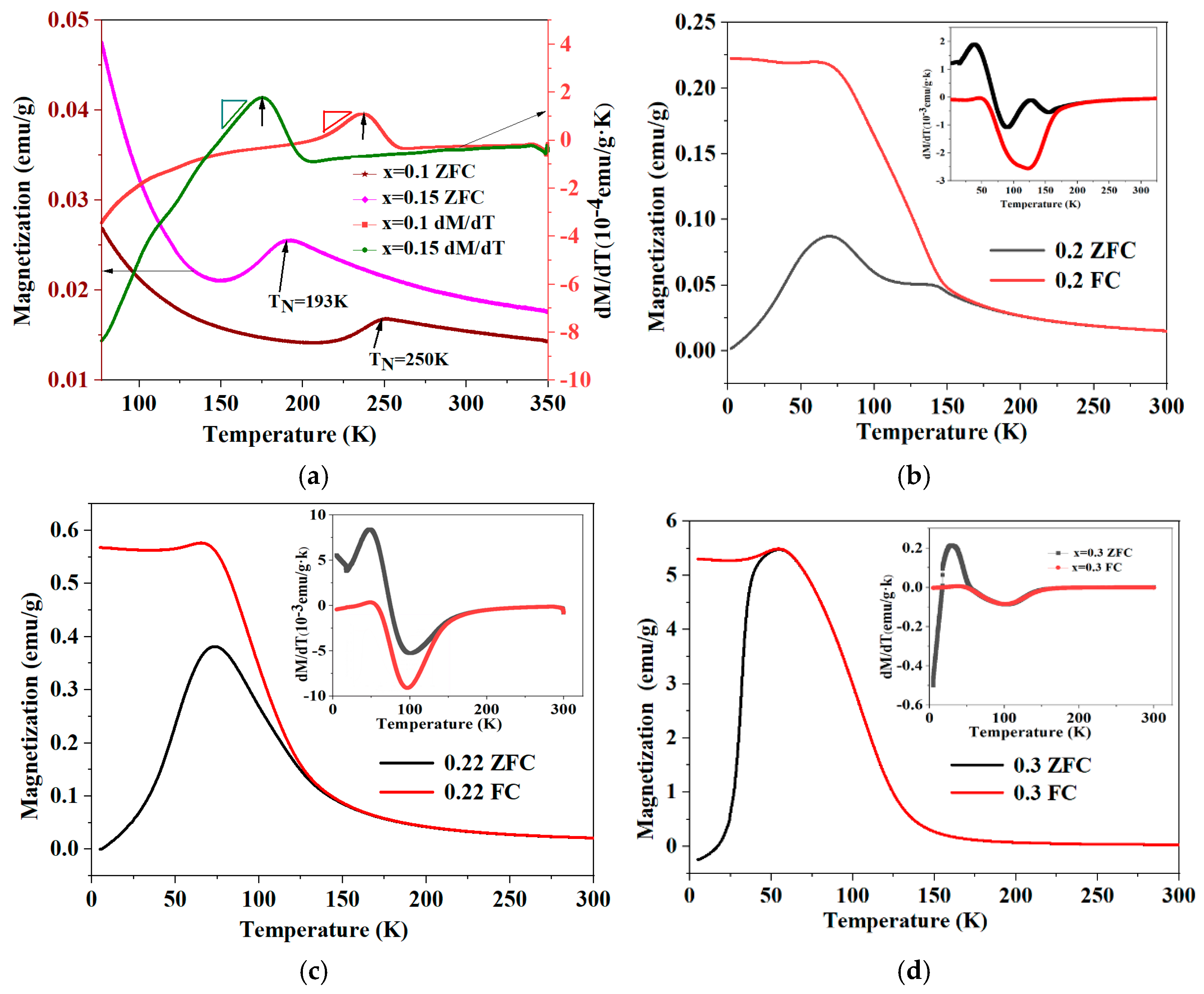

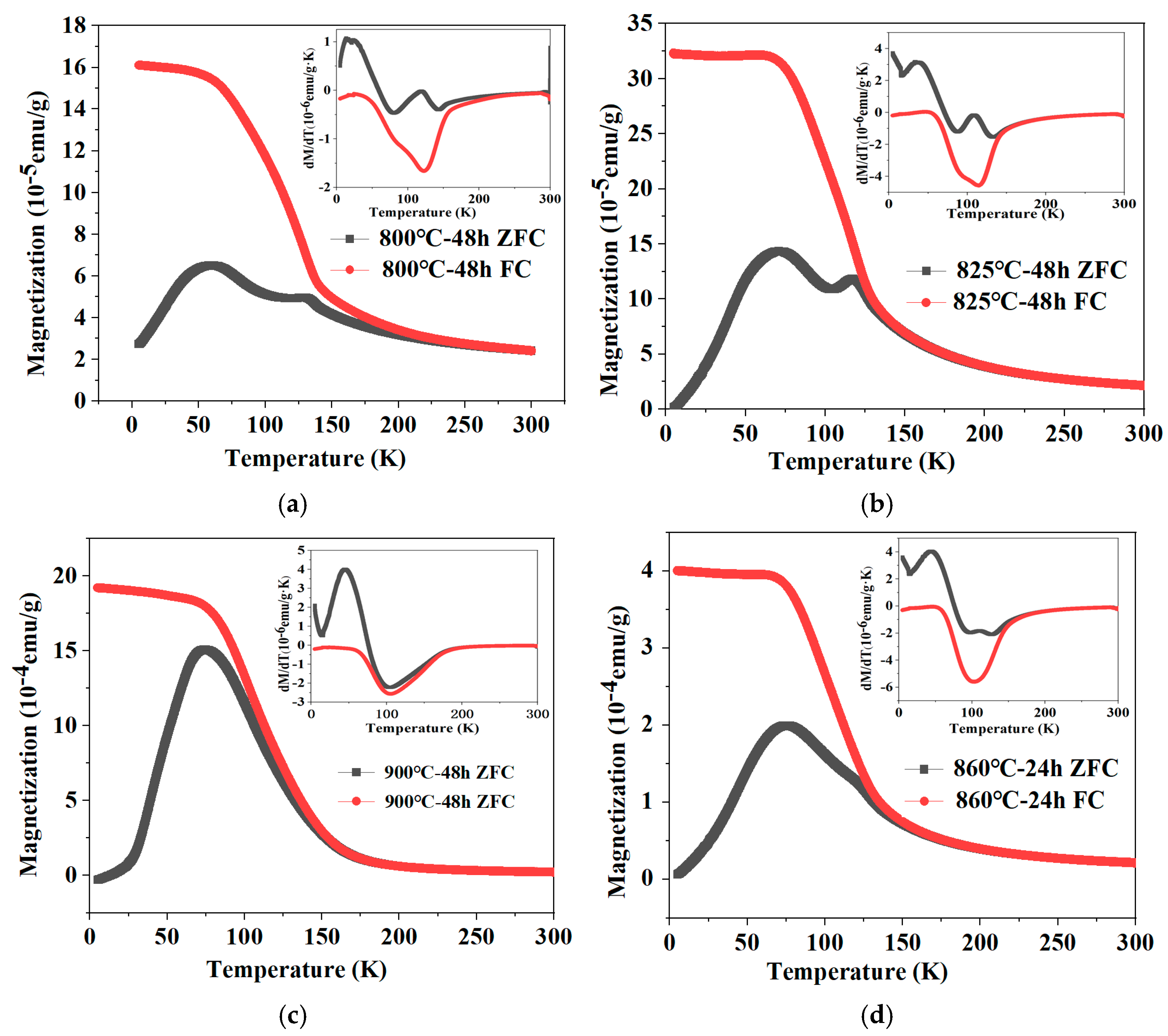

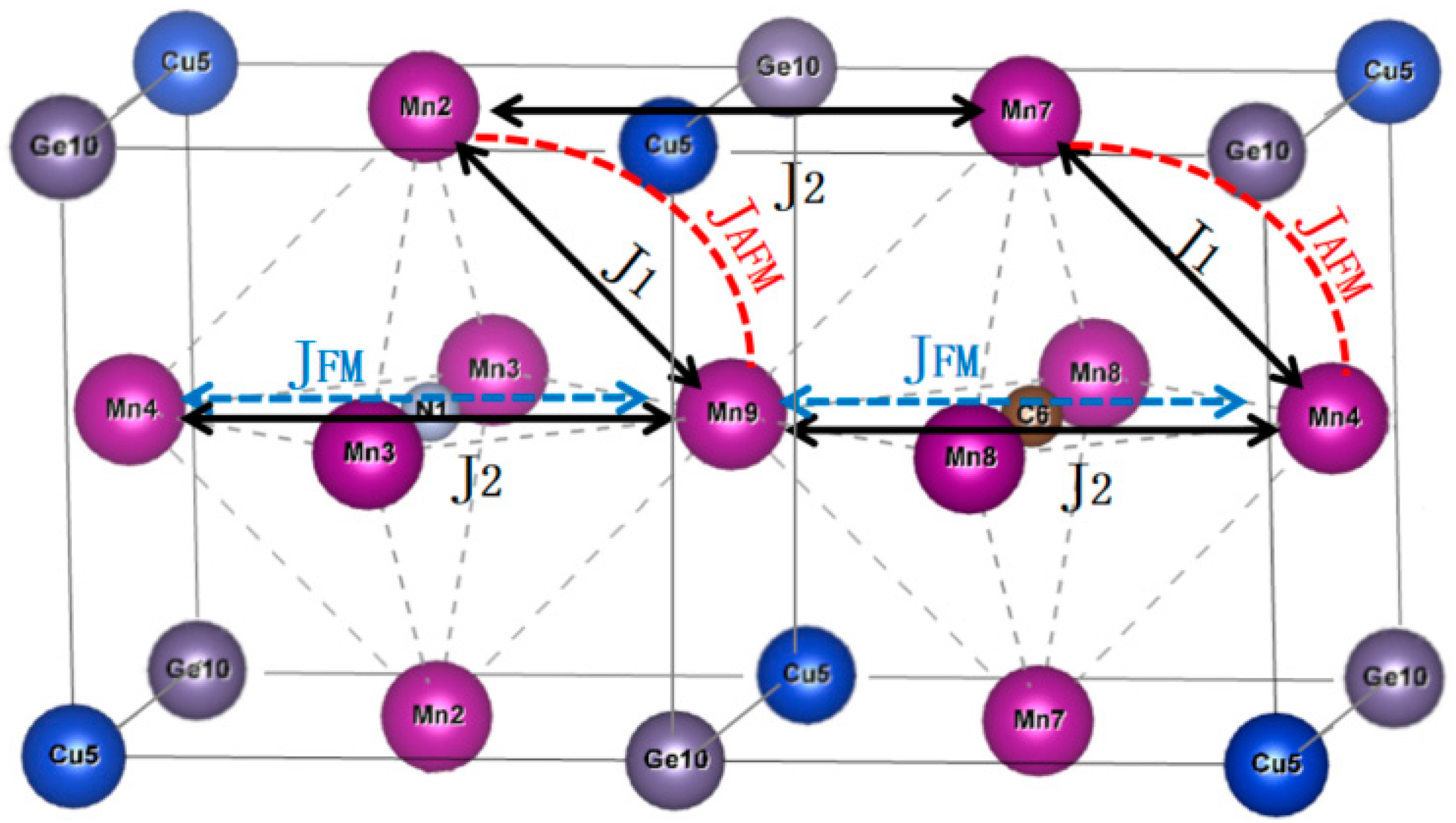

3.4. Magnetic Properties

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sleight, A.J.N. Zero-expansion plan. Nature 2003, 425, 674–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.K.; Wei, C.L.; Lin, J.C.; Xie, L.L.; Liu, K.K.; Xiong, T.J.; Song, W.H.; Tong, P.; Sun, Y.P. Technology, A biomimetic aluminum composite exhibiting gradient-distributed thermal expansion, high thermal conductivity, and highly directional toughness. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 213, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qian, J.; Qian, Z.; Hao, B.; Cong, Q.; Zhou, C. Sintering Temperature Effect of Near-Zero Thermal Expansion Mn3Zn0.8Sn0.2N/Ti Composites. Materials 2023, 16, 5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Qian, J.; Fu, L.; Pei, Y.; Zhong, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Q. Residual stress regulation optimization of plastic and near-zero thermal expansion composite. Acta Mater. 2025, 288, 120881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Lin, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; An, K.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.; Li, T.; Fu, X.; Yu, Q.; et al. An isotropic zero thermal expansion alloy with super-high toughness. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zou, K.; Wang, B.; Yuan, X.; An, S.; Ma, Z.; Shi, K.; Deng, S.; Xu, J.; Yin, W.; et al. Zero Thermal Expansion Behavior in High-Entropy Anti-Perovskite Mn3Fe0.2Co0.2Ni0.2Mn0.2Cu0.2N. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Qiao, Y.; Li, M.; Fan, W.; Guo, J.; Xu, M.; Gao, Q. Tunable thermal expansion from positive, zero to negative in RbMgInMo3O12 with NASICON structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 202201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, H.; Guo, J.; Shi, X.; Liang, E.; Gao, Q. Zero thermal expansion in KxMnxIn2-x (MoO4)3 based materials. Acta Mater. 2024, 281, 120358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Su, Z.; Guo, J.; Shi, X.; Chao, M.; Guo, J.; Wei, B.; Gao, Q. Near-zero thermal expansion of GeNb18O47 ceramic. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 15702–15708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Gao, Q. Zero Thermal Expansion in NiPt(CN)6. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fang, M.; Liu, Q.; Ren, X.; Qiao, Y.; Chao, M.; Liang, E.; Gao, Q. Zero thermal expansion in Cs2W3O10. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Lin, K.; Chen, X.; Jiang, S.; Cao, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; An, K.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D. Superior zero thermal expansion dual-phase alloy via boron-migration mediated solid-state reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Han, Y.; Li, L. Zero thermal expansion achieved by an electrolytic hydriding method in La (Fe, Si)13 compounds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Gao, Q. Negative thermal expansion of two-dimensional materials: A review. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94908155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Shi, K.; Sun, Y.; Colin, C.V.; Deng, S.; An, S.; Ma, Z.; Bordet, P.; Wang, C. Effect of Fe-doping on magnetic structures and “spin-lattice-charge” strong correlation properties in Mn3Sn1-xFexC compounds. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobukawa, Y.; Yasuda, T.; Amemiya, K.; Suemasu, T. Magnetic compensation and preferential substitution site for Ag in Mn4−xAgxN epitaxial thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2025, 9, 064408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Sun, Y.; Lu, H.; Shi, K.; Deng, S.; Yuan, X.; Hao, W.; Du, Y.; Xia, Y.; Fang, L.; et al. Noncoplanar antiferromagnetism induced zero thermal expansion behavior in the antiperovskite Mn3Sn0.5Zn0.5Cx. Phycical Rev. 2023, 107, 094412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; MacLaren, D.; Boldrin, D. Improving barocaloric properties by tailoring transition hysteresis in Mn3Cu1−uSnxN Antiperovskites. J. Phys. Energy 2023, 5, 024018. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Ren, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Asymmetric orbital hybridization in Zn-doped antiperovskite Cu1−xZnxNMn3 enables highly efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 89, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Amaris, D.; Bautista-Hernandez, A.; González-Hernández, R.; Romero, A.H.; Garcia-Castro, A.C. Anomalous Hall conductivity control in Mn3NiN antiperovskite by epitaxial strain along the kagome plane. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 195113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Guo, X.; Yang, G.; Wang, N.; Li, J. The spin-glass-like behavior in antiperovskite Mn3AgN. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 055104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Bai, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Pan, F.; Song, C. Room temperature anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnetic Mn3SnN films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 222404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Guo, Y.; Yao, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, Z. Temperature-Dependent Valence Electron Structures and Properties of the Antiperovskite Compound Mn3Ni1−xAgxN. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 718, 417937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Takenaka, K.; Kishimoto, A.; Takagi, H. Mechanical Properties of Metallic Perovskite Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N: High-Stiffness Isotropic Negative Thermal Expansion Material. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 2999–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, Z.; Huang, Q.; Rettenmayr, M.; Liu, X.; Seyring, M.; Li, G.; Rao, G.; Yin, F. Adjustable zero thermal expansion in antiperovskite manganese nitride. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Huang, R.; Wang, W.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Han, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, L. Broad negative thermal expansion operation-temperature window in antiperovskite manganese nitride with small crystallites. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 2302–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.; Tong, P.; Zhou, X.J.; Lin, H.; Ding, Y.W.; Bai, Y.X.; Chen, L.; Guo, X.G.; Yang, C.; Song, B.; et al. Giant negative thermal expansion covering room temperature in nanocrystalline GaNxMn3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 131902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, K.; Takagi, H. Zero thermal expansion in a pure-form antiperovskite manganese nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 131904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Song, X.; Huang, R.; Li, L.; Sun, Z. Effect of Si doping on structure, thermal expansion and magnetism of antiperovskite manganese nitrides Mn3Cu1−xSixN. Mater. Lett. 2015, 139, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Huang, R.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Sun, Z. Near zero thermal expansion in Ge-doped Mn3GaN compounds. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 1608–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Sun, Z. Effect of Sn doping on the structure, magnetism and thermal expansion of Mn3Ga1−xSnxN (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7) compounds. Appl. Phys. A 2017, 123, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.J. Studies on the Thermophysical Properties of Doped Manganese Nitride Negative Thermal Expansion Materials at Cryogenic Temperature. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cherrad, D.; Maouche, D.; Louail, L.; Maamache, M. Ab initio comparative study of the structural, elastic and electronic properties of SnAMn3 (A = N, C) antiperovskite cubic compounds. Solid State Commun. 2010, 150, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Kanomata, T.; Shirakawa, K. Pressure effect on the magnetic transition temperatures in the intermetallic compounds Mn3MC (M = Ga, Zn and Sn). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1987, 56, 4047–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Yang, J.; Shen, B.; Yi, W.; Matsushita, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; et al. Carbon-induced ferromagnetism in the antiferromagnetic metallic host material Mn3ZnN. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.; Tong, P.; Lin, S.; Wang, B.S.; Song, W.H.; Sun, Y.P. Continuously tunable temperature coefficient of resistivity in antiperovskite AgN1−xCxMn3 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.15). Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 213912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, K.; Takagi, H. Giant negative thermal expansion in Ge-doped anti-perovskite manganese nitrides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 261902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y. Fabrication and Physical Properties of Antiperovskite Mn3(Cu1−xGex)N Negative Thermal Expansion Compounds. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iikubo, S.; Kodama, K.; Takenaka, K.; Takagi, H.; Shamoto, S. Magnetovolume effect in Mn3Cu1−xGexN related to the magnetic structure:Neutron powder diffraction measurements. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, R020409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Designed Composition | Actual Number of Carbon Atoms | Wt% | Preparation Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.9C0.1 | 0.1307 | 0.6350% | 860 °C + 48 h |

| Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22 | 0.2301 | 1.1245% | 860 °C + 48 h |

| Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22 | 0.2267 | 1.1040% | 860 °C + 24 h |

| Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22 | 0.2367 | 1.1529% | 800 °C + 48 h |

| Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.7C0.3 | 0.3301 | 1.5904% | 860 °C + 48 h |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, Z.; Han, C.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Y.; Sun, Z. Adjustable Cryogenic Near-Zero Thermal Expansion and Magnetic Properties in Antiperovskite Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22. Crystals 2026, 16, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010041

Hu Z, Han C, Zhang H, Dai Y, Sun Z. Adjustable Cryogenic Near-Zero Thermal Expansion and Magnetic Properties in Antiperovskite Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Zhishan, Cuihong Han, Hao Zhang, Yongjuan Dai, and Zhonghua Sun. 2026. "Adjustable Cryogenic Near-Zero Thermal Expansion and Magnetic Properties in Antiperovskite Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22" Crystals 16, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010041

APA StyleHu, Z., Han, C., Zhang, H., Dai, Y., & Sun, Z. (2026). Adjustable Cryogenic Near-Zero Thermal Expansion and Magnetic Properties in Antiperovskite Mn3Cu0.5Ge0.5N0.78C0.22. Crystals, 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010041