Tuning Crystallization Pathways via Phase Competition: Heat-Treatment-Induced Microstructural Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experiments

2.1. Preparation of Glass-Ceramic

2.2. Experimental Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.2. Analysis of Crystalline Phases and Morphology Under Different Heat Treatment Processes

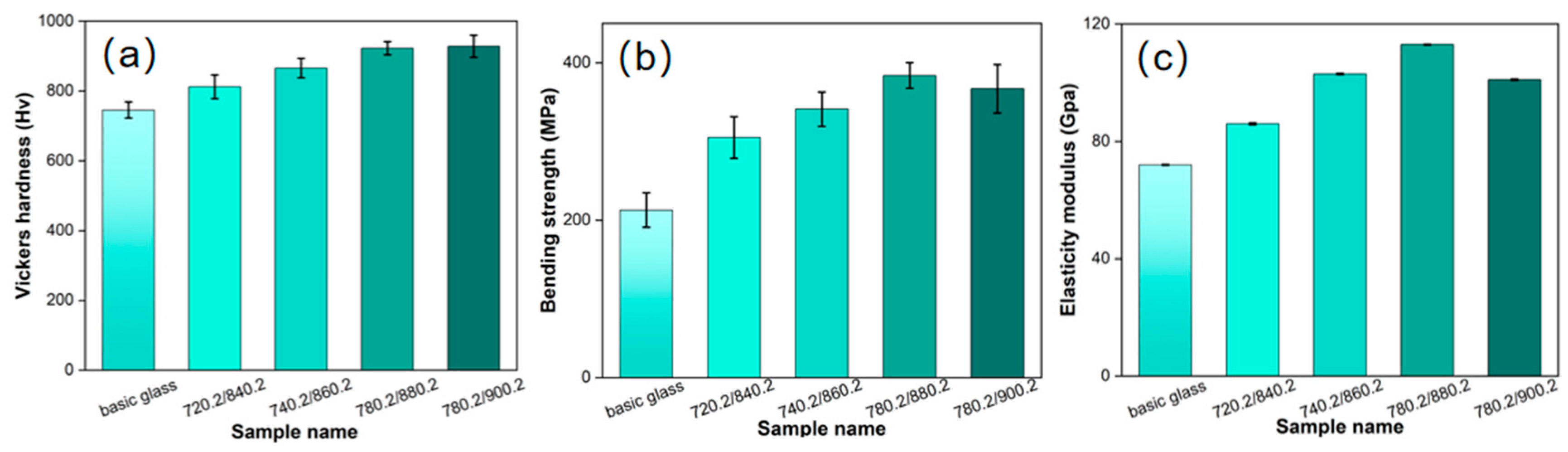

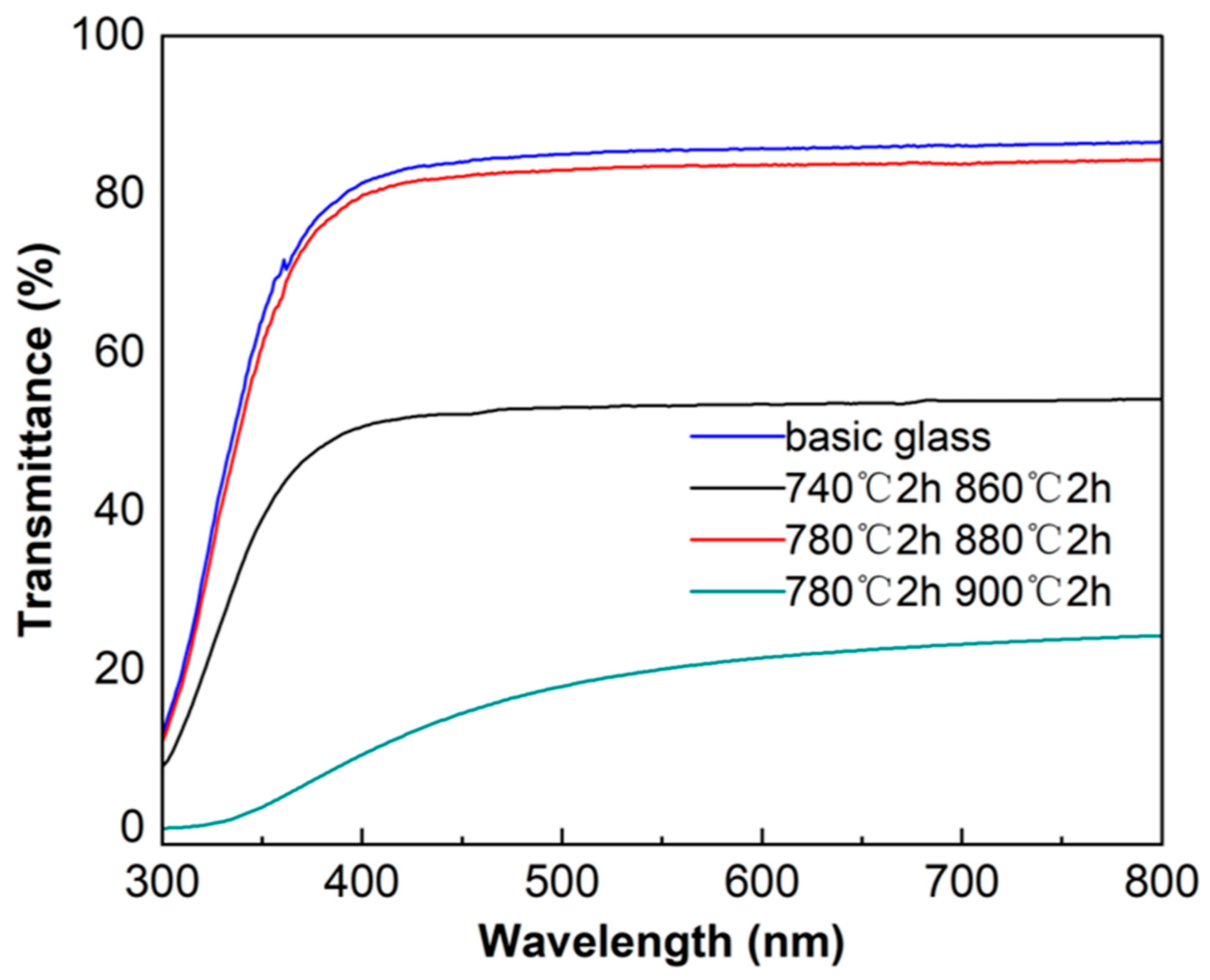

3.3. Performance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petrova, P. Glass-ceramic materials with luminescent properties in the system ZnO-B2O3-Nb2O5-Eu2O3. Molecules 2024, 29, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettlewell, B.; Boyd, D. State of the art review for titanium fluorine glasses and glass ceramics. Materials 2024, 17, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, G.H.; Megles, J.E.; Pinckney, L.R. Glass-Ceramics Containing Cristobalite and Potassium Fluorrichterite. U.S. Patent 4,608,348, 26 August 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tkalčec, E.; Kurajica, S.; Ivanković, H. Crystallization behavior and microstructure of powdered and bulk ZnO-Al2O3-SiO2 glass-ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2005, 351, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.R.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Singh, S.P.; Lancelotti, R.F.; Zanotto, E.D.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Dousti, M.R.; de Camargo, A.S.; Magon, C.J.; Silva, I.D.A. Crystallization, mechanical, and optical properties of transparent, nanocrystalline gahnite glass-ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 1963–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokmann, U.; Sönnichsen, K.; Hülsenberg, D. Application of micro structured photosensitive glass for the gravure printing process. Microsyst. Technol. 2008, 14, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denry, I.; Holloway, J.A. Ceramics for Dental Applications: A Review. Materials 2010, 3, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun-Cai, Z.; Xiao-Mei, L. Development of Glass-ceramic Composites Research. Mater. Mech. Eng. 2007, 31, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ying, W.; He, J.; Fan, X.; Xu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, S. Dual-wavelength enhanced upconversion luminescence properties of Li+-doped NaYF4:Er,Yb glass-ceramic for all-optical logic operations. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 2948–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Quan, Z.; Kong, D.; Liu, X.; Lin, J. Y2O3: Eu3+ Microspheres: Solvothermal Synthesis and Luminescence Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2007, 7, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.S.; Shama, S.A.; Dessouki, H.A.; Ali, A.A. Synthesis, thermal and spectral characterization of nanosized Ni(x)Mg(1−x)Al2O4 powders as new ceramic pigments via combustion route using 3-methylpyrozole-5-one as fuel. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 81, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; She, W.T.; Han, J.J.; Li, L.Y. A Chemically Strengthenable Spinel Glass-Ceramic, Its Preparation Method and Application. CN115010369A, 9 August 2022. CN202210737448.6A, 9 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, M.R.; Scalvi, L.V.A.; Neto, V.S.L.; Dall’antonia, L.H. Development of bilayer glass-ceramic SOFC sealants via optimizing the chemical composition of glasses: A review. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2016, 20, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotto, E.D. A bright future for glass-ceramics. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2010, 89, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Guo, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C. Crystallization of sodium calcium silicate glass for highly transparent glass-ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 3218–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisert, N. Application and machining of Zerodur for optical purposes. In Optical Fabrication and Testing; OSA: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, H. Kinetic analysis of the crystallization of Y2O3 and La2O3 doped Li2O-Al2O3-SiO2 glass. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 7052–7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Dong, C.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, H. Light-transmitting lithium aluminosilicate glass-ceramics with excellent mechanical properties based on cluster model design. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleebusch, E.; Patzig, C.; Höche, T.; Rüssel, C. Effect of the concentrations of nucleating agents ZrO2 and TiO2 on the crystallization of Li2O–Al2O3–SiO2 glass: An X-ray diffraction and TEM investigation. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 10198–10209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Wang, Y.; Lan, B.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Z.; Lv, S.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, S. Pressureless Crystallization of Glass for Transparent Nanoceramics. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1901096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.; Shen, A.H.; Liu, Y.G.; Qian, Z. Raman spectra study of heating treatment and order-disorder transition of Cr3+-doped MgAl2O4 spinel. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2019, 39, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hwa, L.G.; Hwang, S.L.; Liu, L.C. Infrared and Raman spectra of calcium alumino-silicate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1998, 238, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, K.J.; Hemley, R.J. Raman spectroscopic study of microcrystalline silica. Am. Mineral. 1994, 79, 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Loiko, P.; Belyaev, A.; Dymshits, O.; Evdokimov, I.; Vitkin, V.; Volkova, K.; Tsenter, M.; Volokitina, A.; Baranov, M.; Vilejshikova, E.; et al. Synthesis, characterization and absorption saturation of Co:ZnAl2O4 (gahnite) transparent ceramic and glass-ceramics: A comparative study. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 725, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaček-Grošev, V.; Vrankić, M.; Maksimović, A.; Mandić, V. Influence of titanium doping on the Raman spectra of nanocrystalline ZnAl2O4. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 697, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechgaard, T.K.; Goel, A.; Youngman, R.E.; Mauro, J.C.; Rzoska, S.J.; Bockowski, M.; Jensen, L.R.; Smedskjaer, M.M. Structure and mechanical properties of compressed sodium aluminosilicate glasses: Role of non-bridging oxygens. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 441, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, D.A.; Muller, I.S.; Buechele, A.C.; Pegg, I.L.; Kendziora, C.A. Structural characterization of high-zirconia borosilicate glasses using Raman spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2000, 262, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, G. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of Sm3+-doped CaO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2 glasses and glass ceramics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 4896–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-L.; Hwang, C.-S. Structures of CeO2Al2O3SiO2 glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1996, 202, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample No. | Nucleation Temperature/°C | Nucleation Time/h | Crystallization Temperature/°C | Crystallization Time/h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 720 | 2 | 820 | 2 |

| 2 | 720 | 2 | 840 | 2 |

| 3 | 740 | 2 | 840 | 2 |

| 4 | 740 | 2 | 860 | 2 |

| 5 | 760 | 2 | 860 | 2 |

| 6 | 760 | 2 | 880 | 2 |

| 7 | 770 | 2 | 870 | 2 |

| 8 | 780 | 2 | 880 | 2 |

| 9 | 780 | 1 | 880 | 3 |

| 10 | 780 | 2 | 880 | 3 |

| 11 | 780 | 3 | 880 | 2 |

| 12 | 780 | 2 | 900 | 2 |

| 13 | 780 | 2 | 920 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Jiang, H. Tuning Crystallization Pathways via Phase Competition: Heat-Treatment-Induced Microstructural Evolution. Crystals 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010029

Pan Y, Wu Y, Zhang J, Ma Y, Li M, Jiang H. Tuning Crystallization Pathways via Phase Competition: Heat-Treatment-Induced Microstructural Evolution. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010029

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Yan, Yulong Wu, Jiahui Zhang, Yanping Ma, Minghan Li, and Hong Jiang. 2026. "Tuning Crystallization Pathways via Phase Competition: Heat-Treatment-Induced Microstructural Evolution" Crystals 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010029

APA StylePan, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, J., Ma, Y., Li, M., & Jiang, H. (2026). Tuning Crystallization Pathways via Phase Competition: Heat-Treatment-Induced Microstructural Evolution. Crystals, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010029