Abstract

Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) nanofibers have emerged as promising materials for flexible piezoelectric sensors, yet their performance is fundamentally constrained by the limited formation and alignment of the electroactive β-phase. In this study, we report a phase-engineering strategy that integrates ionic functionalization, inorganic nanofiller incorporation, and post-fabrication corona poling to achieve enhanced crystalline ordering and electromechanical coupling in electrospun PVDF nanofibers. Tetrabutylammonium perchlorate increases solution conductivity, enabling uniform, bead-free fiber formation, while barium titanate nanoparticles act as nucleation centers that promote β-phase crystallization at the expense of the non-polar α-phase. Subsequent corona poling further aligns molecular dipoles and strengthens remnant polarization within both the PVDF matrix and embedded nanoparticles. Structural analyses confirm the synergistic evolution of crystalline phases, and piezoelectric measurements demonstrate a substantial increase in peak-to-peak output voltage under dynamic loading conditions. This combined phase-engineering approach provides a simple and scalable route to high-performance PVDF-based piezoelectric sensors and highlights the importance of coupling crystallization control with dipole alignment in designing next-generation wearable electromechanical materials.

1. Introduction

Piezoelectric pressure sensors convert mechanical deformation into electrical signals and are widely used in wearable electronics, biomedical monitoring, and human–machine interfaces [1,2]. Among the major classes of piezo-based sensors—piezoresistive, piezocapacitive, and piezoelectric—the piezoelectric type is particularly attractive because of its self-powered operation and high sensitivity [1,2,3,4]. Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) has received significant attention as a flexible piezoelectric material owing to its mechanical robustness, chemical stability, and compatibility with large-area processing [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

The piezoelectricity of PVDF originates from the electroactive β-phase, which possesses an all-trans conformation with a large net dipole moment [15]. This phase enables strong dipole alignment and efficient electromechanical coupling [7,16,17,18]. However, PVDF commonly crystallizes into the non-polar α-phase under standard processing conditions, requiring external stimuli—such as mechanical stretching, electrical poling, or the introduction of functional additives—to induce β-phase formation and achieve enhanced piezoelectric performance [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

Electrospinning has emerged as a versatile method for fabricating PVDF nanofiber webs with inherently elevated β-phase content, owing to the intense electric field applied during fiber formation [15,24]. Compared with other nanofiber fabrication techniques, electrospinning provides high surface area, porosity, and mechanical flexibility, which are key attributes for wearable sensing applications [1,7]. Nevertheless, the β-phase fraction and dipole alignment in as-spun PVDF nanofibers are often insufficient to deliver high piezoelectric output, making additional phase-engineering strategies necessary [17,21].

To address this limitation, various fillers and dopants have been employed to tailor crystalline phase formation in PVDF. In particular, barium titanate nanoparticles (BTNPs) act as effective nucleation centers that enhance β-phase crystallization through interfacial electrostatic interactions with PVDF chains [23,24,25]. These interactions promote the transformation from the non-polar α-phase to the electroactive β-phase, thereby improving the piezoelectric potential of the nanocomposite fibers [23,24,25,26,27]. In parallel, the electrical conductivity of the spinning solution strongly influences fiber morphology; the introduction of ionic additives can increase ionic concentration, stabilize the electrospinning jet, and yield uniform, bead-free nanofibers [28,29].

In this work, we introduce a combined phase-engineering strategy that integrates ionic functionalization, inorganic nanofiller incorporation, and post-fabrication poling to enhance the crystalline ordering and electromechanical properties of electrospun PVDF nanofibers. Tetrabutylammonium perchlorate (TBAP) is employed as an ionic additive to increase solution conductivity, enabling the formation of uniform nanofibers with reduced morphological defects [28,29]. BTNPs are incorporated as β-phase-inducing fillers that promote the transition from α- to β-crystalline phases in the presence of TBAP [23,24,25,30]. Following electrospinning, corona poling is applied to further align molecular dipoles and strengthen remnant polarization within the PVDF matrix and the embedded nanoparticles.

Unlike conventional approaches that rely solely on nanoparticle doping or electrical poling, the present study demonstrates the synergistic effect of concurrently optimizing solution conductivity, crystalline phase evolution, and dipole alignment. This integrated methodology provides a scalable route to PVDF nanofiber webs with substantially enhanced piezoelectric response. More broadly, this work highlights current challenges in simultaneously achieving high piezoelectric performance, signal uniformity, and scalable fabrication in polymer-based piezoelectric systems.

Advanced interfacial engineering, incorporation of multifunctional nanofillers, and optimized poling strategies are expected to further enhance electromechanical coupling. From an application perspective, the phase-engineered PVDF nanofiber platforms developed here show strong potential for flexible pressure sensors, wearable health-monitoring devices, soft robotics, and human–machine interfaces, while the simple and scalable processing strategy facilitates large-area manufacturing and integration into practical flexible electronic systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Webs with TBAP and BTNPs

PVDF (Mw = 370,000 Da; Kynar 761, Elf Atochem, Seoul, Republic of Korea) was used as a base polymer. A 16 wt% PVDF solution was prepared by dissolving PVDF in a solvent mixture of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and acetone (6:4, v/v) with stirring at 60 °C for 4 h to ensure complete dissolution. TBAP (Product No. 86893, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added at 0.2 wt%. TBAP was selected through preliminary screening of several quaternary ammonium salts due to its superior compatibility with the PVDF/DMF–acetone solution, enabling homogeneous dispersion without phase separation while effectively increasing solution conductivity. Accordingly, its role in this study is limited to stabilizing the electrospinning process and improving fiber uniformity. BTNPs (Product No. 745952, 50 nm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) were incorporated at 4, 8, and 12 parts per hundred resin (phr). Each BTNP-doped solution was magnetically stirred at 30 °C for 12 h, followed by sonication for 90 min to achieve a homogeneous dispersion. BTNPs were chosen as functional fillers owing to their high dielectric constant and ferroelectric nature, which provide strong interfacial electrostatic interactions with PVDF and promote stabilization of the electroactive β-phase during electrospinning.

Electrospinning was performed using the horizontal setup (Figure 1a). Each solution (50 mL) was loaded into a syringe fitted with a 22G needle and electrospun under the following conditions: a flow rate of 1.5 mL/h, applied voltage of 17 kV, and tip-to-collector distance of 13 cm. The collector was rotated at 50 rpm to ensure uniform deposition. The obtained pristine PVDF and TBAP/BTNP-doped PVDF nanofiber webs had an average thickness of 70 ± 2 μm.

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental setup for electrospinning; (b) Corona poling apparatus; (c) Structure of the fabricated sensor; (d) Custom-built dynamic pressure instrument used for piezoelectric performance evaluation.

The electrical conductivity of the PVDF spinning solutions was measured using a conductivity meter (CM-41X, DKK-TOA, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to measurement, the conductivity meter was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions using standard calibration solutions. All measurements were performed at room temperature. Each PVDF solution was gently stirred to ensure homogeneity before measurement, and the conductivity probe was fully immersed in the solution to obtain stable readings. For each composition, the conductivity value was recorded after stabilization of the signal, and the reported values represent the average of multiple measurements to ensure reproducibility.

2.2. Corona Poling Process

The corona poling setup is shown in Figure 1b. A 1 μm-thick PVDF layer was first spin-coated onto a 2 cm × 2 cm indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass substrate and fully dried. The PVDF nanofiber webs were electrospun directly onto the base layer. A grounding wire was connected to the ITO substrate and a DC voltage of 15 kV was applied to the needle tip. The corona treatment was performed for 10 min to align the dipoles and enhance the piezoelectric response.

2.3. Fabrication of Piezoelectric Sensors

Piezoelectric sensors were fabricated using the corona-poled PVDF nanofiber webs. Each nanoweb was sandwiched between two circular electrodes composed of a nickel–copper-plated polyester fabric bonded with a conductive adhesive (Figure 1c). The assembled devices were encapsulated with a transparent adhesive tape for protection and structural stability.

2.4. Piezoelectric Output Measurement

The piezoelectric performance of the nanofiber-based sensors was evaluated by measuring the peak-to-peak voltage (Vp–p) generated under dynamic mechanical loading using a custom-built pressure system (Figure 1d). The active sensing area had a diameter of 2 cm and the loading frequency was set to 0.5 Hz. The cyclic application and release of pressure produced time-dependent polarization changes, resulting in alternating positive and negative voltage signals. Because all devices were fabricated with the same active area and comparable nanofiber web thickness and were evaluated under an identical loading protocol and measurement setup, the measured Vp–p values are intended for relative comparison of processing variables rather than extraction of intrinsic piezoelectric coefficients. A periodic normal force of 1–5 kgf was applied in the form of a 10 Hz square wave with a 50% duty cycle. The output signals were amplified using a Piezo Film Lab Amplifier (TE Connectivity, Berwyn, PA, USA) in the voltage mode (input resistance: 1 GΩ, gain: 0 dB), filtered by a passive bandpass filter (0.1–10 Hz), and recorded using an NI-DAQ board (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) connected to a personal computer.

2.5. Characterization

The morphologies and microstructures of the nanofibers were characterized by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; LEO SUPRA 55, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). The crystalline phase was analyzed using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; 66V FTIR, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) and X-ray diffraction (XRD; D8 Advance diffractometer, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Electrospun Nanofibers from PVDF Solution with TBAP

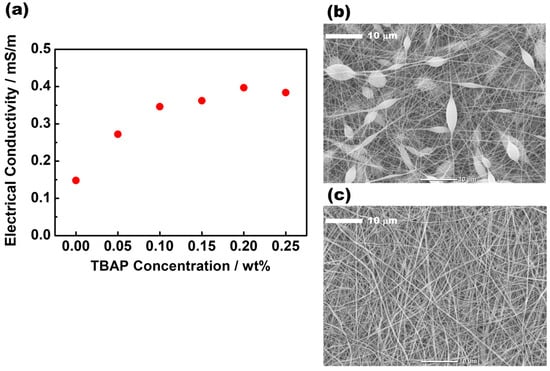

Figure 2a shows the electrical conductivity of PVDF solutions as a function of TBAP concentration, measured using a CM-41X conductivity meter (DKK-TOA, Tokyo, Japan). The conductivity increased with TBAP content up to 0.2 wt% and then plateaued, suggesting that this concentration is optimal for enhancing the electrical properties of the solution. As shown in Figure 2b,c, the improved conductivity directly translated into enhanced fiber morphology: nanofibers electrospun from pristine PVDF exhibited numerous bead defects, whereas those prepared from the solution containing 0.2 wt% TBAP were uniform and bead-free, reflecting improved electrospinning jet stabilization. At this low TBAP concentration (0.2 wt%), no noticeable change in solution viscosity was observed, indicating that the improved fiber uniformity primarily originates from enhanced solution conductivity rather than viscosity reduction.

Figure 2.

(a) Electrical conductivity of PVDF solutions as a function of TBAP concentration. Conductivity increased with TBAP content up to 0.2 wt% and then plateaued, indicating that 0.2 wt% is the optimal concentration for maximizing solution conductivity; (b) FE-SEM image of electrospun nanofibers from a pristine PVDF solution, showing numerous bead defects; (c) FE-SEM image of electrospun nanofibers from a PVDF solution containing 0.2 wt% TBAP, exhibiting uniform, bead-free morphology due to improved jet stabilization resulting from higher conductivity.

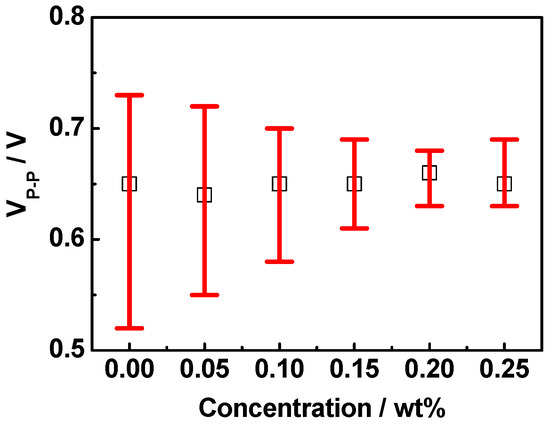

TBAP, a representative quaternary ammonium salt, was used as an additive during electrospinning to promote formation of uniform fibers. The effect of fiber uniformity on the piezoelectric performance was evaluated by measuring the in-plane Vp–p under a constant load of 5 kgf at five locations on each web (without BT nanoparticles). The results summarized in Table 1 and Figure 3 show the maximum, minimum, and average Vp–p values and the differences between the maximum and minimum values as a function of TBAP content. The average Vp–p remained nearly constant regardless of TBAP concentration, indicating that TBAP did not significantly enhance the piezoelectric response. However, increasing the TBAP to the optimal level improved the fiber uniformity, minimizing the in-plane variation in Vp–p across different spots on the same web. These results demonstrate that the enhanced conductivity contributes to better fiber uniformity [28,29] and a more stable in-plane piezoelectric output. The lack of a direct increase in Vp–p with TBAP concentration is attributed to its negligible effect on β-phase crystallization which makes the main contribution to the piezoelectric properties of PVDF. Therefore, although TBAP improved the fiber uniformity and signal consistency, it did not directly increase the intrinsic piezoelectric response. Achieving a bead-free, uniform nanofiber morphology through TBAP incorporation may enhance electromechanical efficiency, mechanical durability, and integration with other functional materials, highlighting the potential of this approach for practical applications.

Table 1.

Vp–p measured under a constant load of 5 kgf. For each TBAP concentration, the in-plane variation in Vp–p was evaluated by measuring five different spots on the web, and the maximum, minimum, and average values are listed.

Figure 3.

Differences between the maximum and minimum values of the in-plane Vp–p, together with the average values, as a function of TBAP concentration. Open squares indicate the average value.

3.2. Electrospun Nanofiber Webs from PVDF Incorporating BTNPs

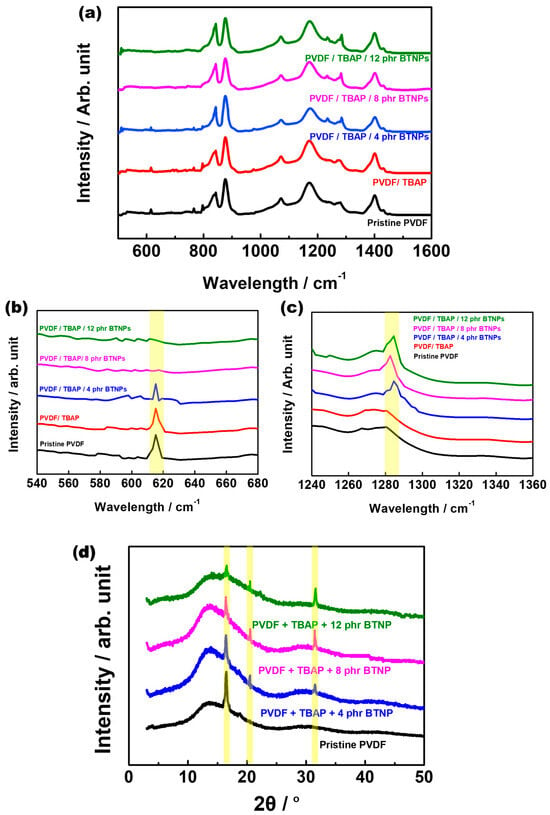

PVDF nanofibers typically consist of both α and β crystalline phases, with the β-phase playing a critical role in piezoelectric performance. To increase the β-phase content and promote favorable polymer chain alignment along the electric field during electrospinning, BTNPs were incorporated into the PVDF solution. Figure 4a shows the FTIR spectra of electrospun PVDF nanofibers prepared from a pristine PVDF solution, a solution containing only 0.2 wt% TBAP, and PVDF solutions containing 0.2 wt% TBAP with varying concentrations of BTNPs. Here, FTIR analysis is used to compare relative changes in crystalline phase content among samples measured under identical conditions, rather than to extract absolute β-phase fractions. The spectra of the pristine PVDF and TBAP-only samples are nearly identical, confirming that TBAP does not significantly influence the crystalline structure of PVDF. In contrast, the incorporation of BTNPs leads to a progressive reduction in the α-phase absorption band at ~620 cm−1 (Figure 4b) and a concomitant enhancement of the characteristic β-phase band at ~1285 cm−1 (Figure 4c), indicating effective stabilization of the electroactive β-phase. The promotion of the β-phase by the incorporation of BTNPs is also confirmed by XRD analysis. XRD data of electrospun PVDF nanofibers prepared under different compositions are provided in Figure 4d. In the XRD spectra, the α-phase is observed at 2θ = 17.6° corresponding to the (100) plane, while the β-phase is detected at 2θ = 20.5° corresponding to the (200) plane. In addition, BTNPs exhibit a strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 31.5° corresponding to the (110) plane. As the BTNP content increases, the intensity of the α-phase peak decreases, whereas the characteristic peaks of the β-phase and BTNPs increase.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of electrospun PVDF nanofibers: (a) FTIR spectra of electrospun PVDF nanofibers prepared from pristine PVDF solution, from a solution containing only 0.2 wt% TBAP, and from PVDF solutions containing 0.2 wt% TBAP with varying concentrations of BTNPs. The spectra of pristine PVDF and TBAP-only samples were nearly identical, indicating that TBAP alone does not significantly influence the crystalline structure. By contrast, incorporation of BTNPs into the PVDF/TBAP solution altered the FTIR profiles; (b) Progressive reduction in the α-phase band (~620 cm−1) with increasing BTNP content; (c) Enhanced β-phase band (~1285 cm−1), indicating BTNP-induced stabilization of the electroactive β-phase; (d) XRD data of electrospun PVDF nanofibers prepared under different compositions. As the BTNP content increases, the intensity of the α-phase peak decreases, whereas the characteristic peaks of the β-phase and BTNPs increase.

This β-phase promotion can be attributed to interfacial interactions between PVDF chains and BTNPs. PVDF chains possess strong dipole moments, which interact with the localized charge distribution and interfacial electric fields at the surface of BTNPs. These dipole–dipole and electrostatic interactions promote preferential chain alignment in an all-trans conformation at the polymer–particle interface, allowing BTNPs to act as effective nucleation sites for the electroactive β-phase. Consequently, BTNP incorporation promotes the nucleation and stabilization of the β-phase at the expense of the non-polar α-phase, thereby contributing to the enhanced piezoelectric potential of the nanofiber webs [25,29,30].

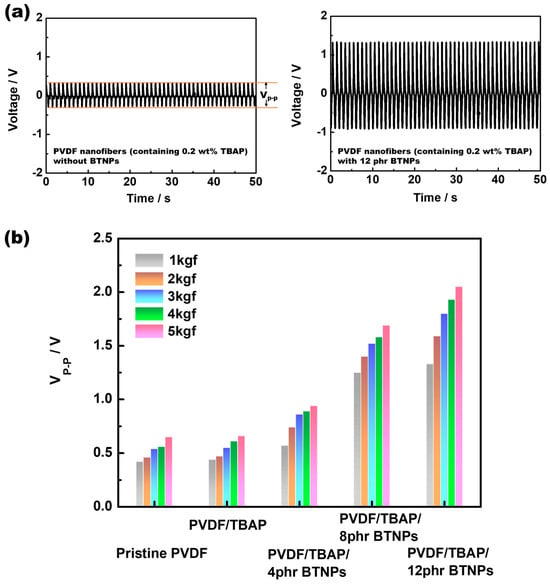

Figure 5a shows representative output Vp–p values for sensors fabricated from electrospun PVDF nanofibers containing 0.2 wt% TBAP without BTNPs and with 12 phr BTNPs, under a constant load of 5 kgf. Figure 5b summarizes the dependence of Vp–p on both the BTNP concentration and applied normal force. The incorporation of BTNPs resulted in a substantial increase in output Vp–p, which can be attributed to the synergistic effects of enhanced β-phase content and improved polymer chain alignment induced by BTNPs during electrospinning. Both factors contributed to the improved piezoelectric performance of the nanofiber webs.

Figure 5.

(a) Representative Vp–p values of sensors fabricated from electrospun PVDF nanofibers (containing 0.2 wt% TBAP) without BTNPs and with 12 phr BTNPs under a constant load of 5 kgf; (b) Dependence of Vp–p on BTNP concentration and applied normal force. The incorporation of BTNPs resulted in a substantial increase in Vp–p. The TBAP concentration was fixed at 0.2 wt%.

We observed that the piezoelectric performance increased proportionally with BTNP content up to 12 phr. At BTNP contents exceeding 12 phr, a degradation in piezoelectric performance was observed, which is likely associated with reduced nanoparticle dispersibility at higher loadings—a behavior commonly reported in PVDF-based nanocomposites [31]—and can adversely affect fiber morphology and overall sensor performance. Therefore, in the present study, all experiments were conducted using BTNP concentrations of ≤12 phr.

3.3. Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Webs with Corona Poling Treatment

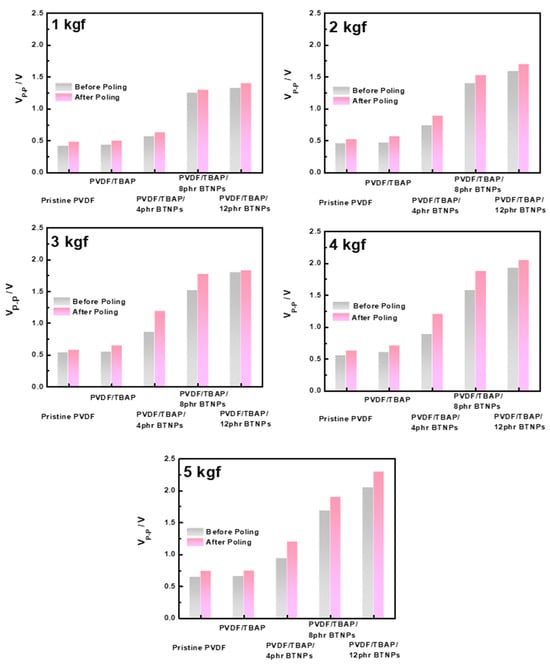

To further enhance the piezoelectric properties of the nanofiber webs, a high-voltage corona poling treatment was applied to electrospun PVDF nanofiber webs prepared from solutions containing 0.2 wt% TBAP and varying concentrations of BTNPs. Figure 6 compares the output Vp–p values of electrospun PVDF nanofiber webs fabricated with and without corona poling as a function of BTNP concentration under different applied pressures. The corona poling treatment consistently enhances the output Vp–p across all BTNP concentrations and pressure levels, with the enhancement becoming more pronounced at higher applied pressures. This improvement primarily arises from enhanced dipole alignment within the PVDF matrix, which constitutes the dominant contribution to the piezoelectric response.

Figure 6.

Comparison of output Vp–p of electrospun PVDF nanofiber webs with and without corona poling plotted as a function of BTNP concentration for different applied pressures. Corona poling consistently enhanced Vp–p across all BTNP concentrations and pressure levels, with the poling effect becoming particularly pronounced at higher applied pressures. The TBAP concentration was fixed at 0.2 wt%.

In the PVDF/BTNP composite system, the dielectric mismatch between the polymer matrix and the embedded BTNPs leads to local electric field concentration at the polymer–particle interface during poling. This interfacial field amplification enhances electromechanical coupling in PVDF chains adjacent to the BTNP surface and facilitates efficient transfer of applied mechanical stress into localized polarization changes. As a result, the combined effects of PVDF dipole alignment and interfacial field concentration create a more effective stress-to-charge generation pathway, accounting for the observed increase in piezoelectric output after corona poling. These findings demonstrate that corona poling is an effective and scalable post-treatment strategy for improving the piezoelectric performance of electrospun PVDF nanofiber webs.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated a phase-engineering strategy that integrates ionic functionalization, inorganic nanofiller incorporation, and post-fabrication poling to enhance the electromechanical performance of electrospun PVDF nanofiber webs. The introduction of TBAP increased the electrical conductivity of the spinning solution, enabling the formation of uniform, bead-free fibers. Incorporation of BTNPs promoted the nucleation and stabilization of the electroactive β-phase while suppressing the non-polar α-phase, as verified by FTIR analysis. These crystalline-phase modifications, combined with the chain alignment induced during electrospinning, substantially improved the piezoelectric output. Corona poling provided an additional enhancement by reinforcing dipole orientation and remnant polarization within both the PVDF matrix and the embedded nanoparticles, leading to stronger electromechanical coupling under dynamic loading.

The piezoelectric performance achieved in this study is comparable, at the device output level, to that reported for recently developed flexible PVDF-based piezoelectric sensors employing composite structures and post-poling treatments. Recent electrospun PVDF-based systems have demonstrated similar output ranges under dynamic loading conditions, indicating that the present material platform provides competitive performance within this context. Importantly, this device-level performance is achieved through a simple and scalable processing strategy, highlighting its potential for practical flexible sensing applications. Future work will include standardized measurements of intrinsic piezoelectric coefficients to enable more direct and quantitative comparison with literature-reported values.

Overall, the synergistic combination of solution optimization, nanofiller-driven phase transformation, and electrical poling presents a scalable and effective route for producing high-performance PVDF-based piezoelectric materials. This work highlights the importance of coupling crystalline-phase control with dipole alignment in the design of flexible piezoelectric sensors for wearable electronics, soft robotics, and human–machine interfaces. Future studies incorporating numerical modeling and microscopic analyses will further elucidate the structure–property relationships governing the enhanced performance demonstrated here.

Author Contributions

Investigation, S.K.H.; Data curation, J.-J.L.; Writing—original draft, S.K.H.; writing—review and editing, S.-W.C., Visualization. J.-J.L., Supervision, S.-W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea under Grant No. RS-2020-NR049601. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Capacity Enhancement Project through Korea Basic Science Institute (National research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 to assist with improving clarity and readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kalimuldina, G.; Turdakyn, N.; Abay, I.; Medeubayev, A.; Nurpeissova, A.; Adair, D.; Bakenov, Z. A Review of Piezoelectric PVDF Film by Electrospinning and Its Applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.-G. Processes of Electrospun Polyvinylidene Fluoride-Based Nanofibers, Their Piezoelectric Properties, and Several Fantastic Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Ahn, Y.; Null, A.P.; Null, K.K. Piezoelectric Polymer and Piezocapacitive Nanoweb Based Sensors for Monitoring Vital Signals and Energy Expenditure in Smart Textiles. J. Fiber Bioeng. Inform. 2013, 6, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, H.; Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Yeung, L. Preparation of Polyurethane Nanofibers by Electrospinning. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 109, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Li, H.; Chu, X.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Yan, S. The Tuning of Crystallization Behavior of Ferroelectric Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-trifluoroethylene). J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 1742–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozza, E.S.; Monticelli, O.; Marsano, E.; Cebe, P. On the Electrospinning of PVDF: Influence of the Experimental Conditions on the Nanofiber Properties. Polym. Int. 2013, 62, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D.; Yoon, S.; Kim, K.J. Origin of Piezoelectricity in an Electrospun Poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) Nanofiber Web-Based Nanogenerator and Nano-Pressure Sensor. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xia, G.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Q.; Song, R.; Ma, Z. Unzipped Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes-Incorporated Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Nanocomposites with Enhanced Interface and Piezoelectric β Phase. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 393, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Prabu, A.A.; Kim, K.J.; Park, C. Metal Salt-Induced Ferroelectric Crystalline Phase in Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Films. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2008, 29, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.J.; Prabu, A.A. Ferroelectric P(VDF/TrFE) Ultrathin Film for SPM-Based Data Storage Devices. Solid State Phenom. 2007, 124–126, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Kotaki, M.; Ramakrishna, S. A Review on Polymer Nanofibers by Electrospinning and Their Applications in Nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 2223–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhu, G.; Vugrinovich, B.; Kataphinan, W.; Reneker, D.H.; Wang, P. Enzyme-Carrying Polymeric Nanofibers Prepared via Electrospinning for Use as Unique Biocatalysts. Biotechnol. Prog. 2002, 18, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekbote, G.S.; Khalifa, M.; Mahendran, A.; Anandhan, S. Cationic Surfactant Assisted Enhancement of Dielectric and Piezoelectric Properties of PVDF Nanofibers for Energy Harvesting Application. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T. (Ed.) Nanofibers—Production, Properties and Functional Applications; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, K.; Kobayashi, M. FTIR Study on Molecular Orientation and Ferroelectric Phase Transition in Vacuum-Evaporated and Solution-Cast Thin Films of Vinylidene Fluoride–Trifluoroethylene Copolymers: Effects of Heat Treatment and High-Voltage Poling. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Spectrosc. 1994, 50, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bune, A.V.; Fridkin, V.M.; Ducharme, S.; Blinov, L.M.; Palto, S.P.; Sorokin, A.V.; Yudin, S.G.; Zlatkin, A. Two-Dimensional Ferroelectric Films. Nature 1998, 391, 874–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Dielectric Properties and Ferroelectric Behavior of Poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) 50/50 Copolymer Ultrathin Films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 80, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.M.; Xu, H.; Fang, F.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Xia, F.; You, H. Critical Thickness of Crystallization and Discontinuous Change in Ferroelectric Behavior with Thickness in Ferroelectric Polymer Thin Films. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 89, 2613–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Razavi, B.; Xu, H.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Zhang, Q.M. Dependence of Threshold Thickness of Crystallization and Film Morphology on Film Processing Conditions in Poly(vinylidene fluoride–trifluoroethylene) Copolymer Thin Films. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 3111–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, T.J.; Ducharme, S.; Sorokin, A.V.; Poulsen, M. Nonvolatile Memory Element Based on a Ferroelectric Polymer Langmuir–Blodgett Film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.S. Simple Synthesis of Palladium Nanoparticles, β-Phase Formation, and the Control of Chain and Dipole Orientations in Palladium-Doped Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Thin Films. Langmuir 2012, 28, 10310–10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, C.J.L.; Job, A.E.; Chinaglia, D.L. Phase Transition in Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride) Investigated with Micro-Raman Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005, 59, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulelah, H.; Sweah, Z.J.; Fouad, F.; Modhi, H. Enhancing PVDF Polymer Properties via Varied Barium Titanate Morphologies and Synthesis Techniques: Review. J. Technol. Sci. 2024, 1, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, M.; Makreski, P.; Zanoni, M.; Gasperini, L.; Selleri, G.; Fabiani, D.; Gualandi, C.; Bužarovska, A. Effects of Nano-Sized BaTiO3 on Microstructural, Thermal, Mechanical and Piezoelectric Behavior of Electrospun PVDF/BaTiO3 Nanocomposite Mats. Polym. Test. 2023, 126, 108158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, H.; Agarwala, S. PVDF-BaTiO3 Nanocomposite Inkjet Inks with Enhanced β-Phase Crystallinity for Printed Electronics. Polymers 2020, 12, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athira, B.S.; George, A.; Vaishna Priya, K.; Hareesh, U.S.; Gowd, E.B.; Surendran, K.P.; Chandran, A. High-Performance Flexible Piezoelectric Nanogenerator Based on Electrospun PVDF-BaTiO3 Nanofibers for Self-Powered Vibration Sensing Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 44239–44250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.D.; Mohapatra, P.C.; Aria, A.I.; Christie, G.; Mishra, Y.K.; Hofmann, S.; Thakur, V.K. Piezoelectric Materials for Energy Harvesting and Sensing Applications: Roadmap for Future Smart Materials. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorayani Bafqi, M.S.; Bagherzadeh, R.; Latifi, M. Fabrication of Composite PVDF-ZnO Nanofiber Mats by Electrospinning for Energy Scavenging Application with Enhanced Efficiency. J. Polym. Res. 2015, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobola, D.; Kaspar, P.; Částková, K.; Dallaev, R.; Papež, N.; Sedlák, P.; Trčka, T.; Orudzhev, F.; Kaštyl, J.; Weiser, A.; et al. PVDF Fibers Modification by Nitrate Salts Doping. Polymers 2021, 13, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.K.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, K.J.; Choi, S.W. Electrospun Poly L-Lactic Acid Nanofiber Webs Presenting Enhanced Piezoelectric Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadwal, N.; Ben Mrad, R.; Behdinan, K. Review of Piezoelectric Properties and Power Output of PVDF and Copolymer-Based Piezoelectric Nanogenerators. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.