Abstract

The parameters of the austempering process play a crucial role in governing the microstructure and mechanical properties of carbide-free bainitic (CFB) steel. In this study, a CFB steel was austempered at temperatures close to its martensite start (Ms = 372 °C) temperature to investigate the bainitic transformation kinetics, microstructure, and mechanical properties. To identify the optimal strength–ductility combination, austempering was carried out at 360 °C, 380 °C, and 400 °C for comparison. The results show that austempering slightly below Ms (360 °C) produces the highest yield-to-tensile strength ratio and a good strength–ductility balance. Dilatometry curves indicate that the onset of bainite transformation occurs fastest when austempering slightly below Ms. The stronger transformation driving force and the presence of athermal martensite are the primary reasons. The enhanced thermodynamic driving force and increased nucleation density promote the formation of a larger amount of bainitic laths. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis reveals that the retained austenite blocks are finest after austempering at 360 °C, which helps alleviate the ductility loss associated with the reduction in retained austenite content.

1. Introduction

With the growing concern for vehicle safety, the performance requirements of automotive body materials are becoming more demanding. The concept of third-generation automotive steels with low cost and high performance has been proposed to replace the traditional first- and second-generation steels [1]. Carbide-free bainitic (CFB) steel, as an important representative of the third-generation advanced high-strength steels, has attracted much attention in the automotive industry due to its excellent strength–ductility combination [2].

The typical microstructure of CFB steel consists of bainitic ferrite (BF), retained austenite (RA), and a small amount of fresh martensite (FM) [3,4]. Austempering is the commonly applied heat treatment process used for its production [5,6,7,8,9]. During the isothermal holding stage, the bainitic transformation occurs. As the transformation proceeds, carbon atoms are partitioned from bainite into the surrounding untransformed austenite, thereby enhancing the thermal stability of austenite. When the holding stage ends and cooling starts, the austenite with lower stability transforms into martensite, forming fresh martensite, while the austenite with higher stability is retained to room temperature as RA. Bainite provides the primary strength of the steel, while retained austenite improves ductility through the transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) effect under strain. Therefore, the volume fraction, morphology, and spatial distribution of bainite and retained austenite determine the strength and ductility of CFB steel. In other words, the isothermal temperature and holding time are the key parameters that control the microstructure and mechanical properties of CFB steel.

Previous studies [10,11] have reported clear differences in the microstructure and mechanical properties of CFB steels austempered above and below the martensite start (Ms) temperature. When the heat treatment is conducted above Ms, increasing the isothermal temperature results in a higher fraction of fresh martensite, while the fractions of bainite and retained austenite gradually decrease [12]. In contrast, when austempered below Ms, the formation of athermal martensite can significantly accelerate the bainitic transformation, refine the bainitic laths, and reduce the amount of fresh martensite [13]. However, at much lower temperatures below Ms, the degree of transformation of supercooled austenite increases markedly, causing a significant decrease in retained austenite and a loss in elongation [14]. Compared with below-Ms austempering, treatments above Ms produce a larger amount of bainite but also more fresh martensite [15]. Overall, the literature suggests that austempering about 20 °C above Ms provides the best combination of strength and ductility. However, the microstructure and mechanical behavior of CFB steels austempered near Ms remain insufficiently understood.

In this study, a typical low-carbon C–Si–Mn microalloyed steel was selected and subjected to austempering to obtain CFB steel. The bainite transformation kinetics, microstructure, and mechanical properties after isothermal treatments at different temperatures near the Ms were systematically investigated. The findings are expected to provide scientific guidance for the design of process parameters in industrial production.

2. Materials and Methods

The chemical composition (wt.%) of the low-carbon microalloyed steel used in this study was Fe-0.2C-1.3Si-1.9Mn-0.05V-0.05Ti-0.17Mo. An appropriate amount of Si was added to suppress carbide precipitation and to obtain a carbide-free bainitic microstructure. After melting, homogenization, and forging, the initial experimental steel billet was produced. The billet was then heated at 1250 °C for 1 h and hot-rolled to a thickness of 3 mm. The hot-rolled sheet was immediately transferred to a furnace preheated to 620 °C, held for 30 min, and then furnace-cooled. Finally, the hot-rolled sheet was cold-rolled to a thickness of 1.6 mm.

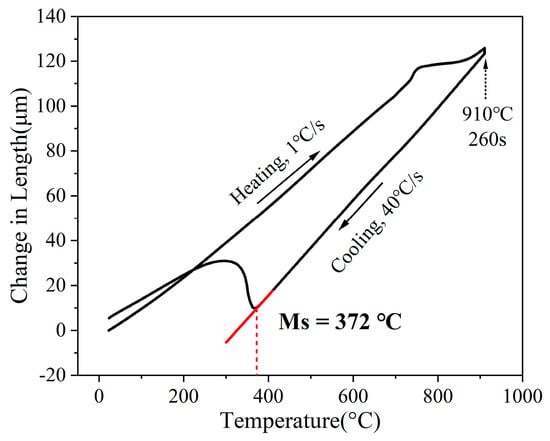

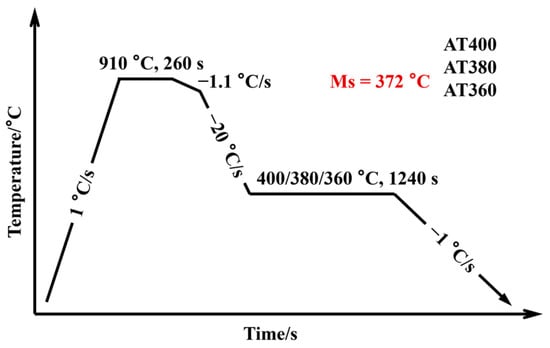

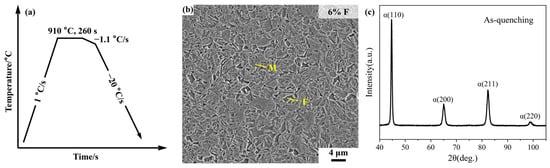

Samples with dimensions of 10 mm (rolling direction) × 4 mm × 1.6 mm were cut from the cold-rolled sheets by wire electrical discharge machining for dilatometry tests. As shown in Figure 1, the dilatometric curve reveals that the martensite start temperature (Ms) of the experimental steel is 372 °C. Based on this result and existed industrial continuous annealing routes, the austempering process was designed as shown in Figure 2. The samples were first heated from room temperature to 910 °C at a rate of 1 °C/s and held for 260 s for austenitization. They were then cooled to 760 °C at 1.1 °C/s, followed by quenching to 400 °C, 380 °C, and 360 °C at 20 °C/s for isothermal holding for 1240 s. Finally, the samples were cooled to room temperature at 1 °C/s. To ensure precise control of the process parameters, all heat treatment procedures were carried out using a continuous annealing simulator equipped with thermocouples. The specimens austempered at 400 °C, 380 °C, and 360 °C were designated as AT400, AT380, and AT360, respectively.

Figure 1.

Dilatometric curve of the experimental steel.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the austempering process for the experimental steel.

The microstructural morphology of the austempered samples was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Sigma 500, ZEISS, Baden-Württemberg, Germany). The samples for SEM analysis were first polished sequentially with 400#, 800#, 1200#, and 2000# sandpapers to remove the oxide layer, followed by mechanical polishing using a cloth with 2.5 μm diamond particles. The polished surfaces were then etched with a 4% nitric acid solution until the microstructure was fully revealed.

X-ray diffraction (XRD, Cu-Kα radiation, 40 kV, 30 mA) was used to determine the volume fraction of retained austenite (RA) and its average carbon content in the austempered samples. The integrated intensities of the (111)γ, (200)γ, (220)γ, (311)γ, (110)α, (200)α, (211)α and (220)α diffraction peaks were used to estimate the RA fraction. The volume fraction of RA was calculated using Equation (1) [16]:

where n is the number of peaks examined, and I is the integrated intensity of the diffraction peak. R is a material scattering factor, . v is the volume of the unit cell, F is a structure factor, P is a multiplicity factor, is a temperature factor, is an angular factor, and θ is the diffraction angle.

The concentration of carbon in austenite was calculated by Equation (2) [17]:

where is the austenite lattice parameter (Å) calculated by Equations (3) and (4). and are the concentrations of manganese and aluminum in austenite (wt.%), respectively.

where h, k, l are the crystallographic indices, d is the crystallographic spacing, θ is the diffraction angle, and λ is the wavelength of the X-ray.

The microstructure was further analyzed using a field emission scanning electron microscope equipped with an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD, NordlysNano max3, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) detector to identify phases and characterize the orientations of bainitic laths and the distribution of retained austenite. EBSD data were collected from an area of 45 × 45 μm with a step size of 60 nm. The acquired data were post-processed using AztecCrystal software (version 2.1). Samples for EBSD and XRD analysis were prepared using the same procedure. They were first manually ground and then mechanically polished, followed by electro-polishing in a 7% perchloric acid–ethanol solution to fully remove the surface stress layer.

To monitor the bainitic and martensitic transformations during austempering, the austempering process was simulated on a dilatometer (DIL L78/Q/D/T, LINSEIS, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) to obtain the corresponding dilatometry curves. Two thermocouples were attached to the symmetrically positioned centers on the 4 mm × 10 mm sample surface using multiple spot welds.

The mechanical properties of the austempered samples were measured using an electronic universal testing machine. The tensile specimens had a thickness of 1.6 mm, a gauge length of 50 mm, and were aligned parallel to the rolling direction.

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties

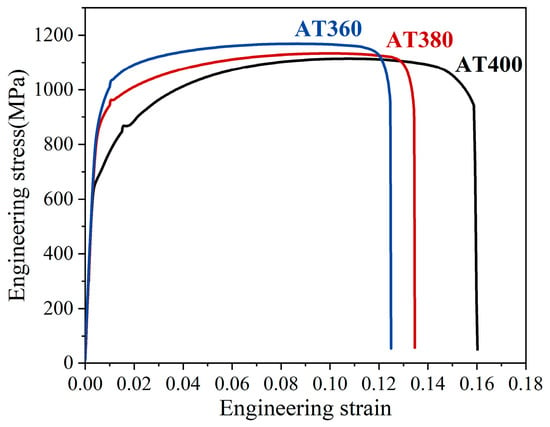

Figure 3 shows the engineering stress–strain curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 tensile specimens. The detailed tensile properties are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, decreasing the austempering temperature results in lower yield and tensile strengths, while both uniform elongation and total elongation increase. The sample austempered slightly below Ms (AT360) exhibits the best overall mechanical performance, including the highest yield-to-tensile strength ratio, highest strength, and an appropriate elongation. For samples austempered above Ms (AT400 and AT380), increasing the isothermal temperature leads to a significant reduction in the yield-to-tensile ratio, although elongation and the strength–ductility product are improved.

Figure 3.

The engineering stress–strain curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 tensile samples.

Table 1.

Tensile mechanical properties of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples. YS: yield strength; UTS: ultimate tensile strength; UE: uniform elongation; TE: total elongation; PSE: product of tensile strength and total elongation.

3.2. Microstructural Features

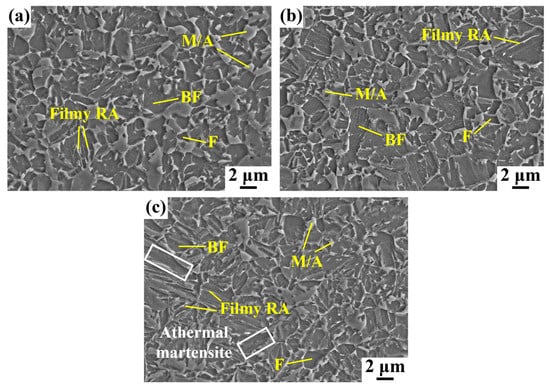

Figure 4 shows the SEM microstructures of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples. The microstructures of AT400 and AT380 samples are quite similar, consisting of a small amount of polygonal ferrite (F), bainitic ferrite (BF), retained austenite (RA), and a few martensite/austenite (M/A) blocks. In contrast, a small amount of athermal martensite is present in the AT360 sample, manifesting as large, slender laths containing dispersed carbide particles. As the austempering temperature decreases, the size of the M/A blocks gradually decreases. In addition, the AT360 sample appears to contain the largest fraction of lath bainite.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the microstructure for the samples: (a) AT400, (b) AT380, and (c) AT360.

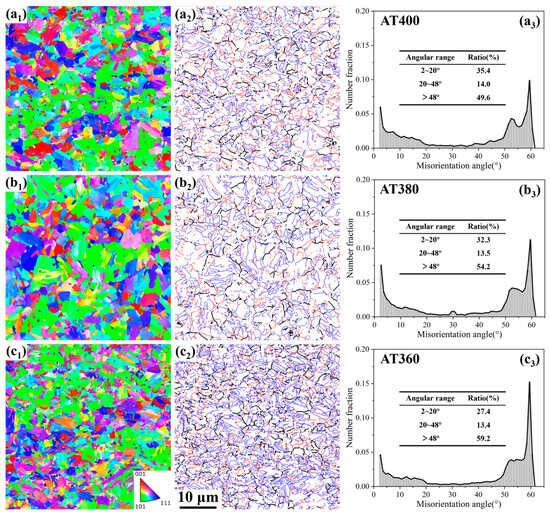

To clarify the morphology of bainite in each sample, EBSD was used to characterize the orientations and boundaries of individual bainitic laths. Figure 5(a1–c1) show the inverse pole figure (IPF) maps of the VTi-added samples at different austempering temperatures. It can be seen that as the austempering temperature decreases from 400 °C to 380 °C and 360 °C, the bainitic laths become progressively finer. Figure 5(a2–c2) show the boundaries between bainitic laths/blocks derived from Figure 5(a1–c1). The boundaries were classified as low-angle (2–20°), medium-angle (20–48°), and high-angle (>48°) boundaries, marked in red, black, and blue, respectively. Figure 5(a3–c3) present the distribution of misorientation angles based on Figure 5(a2–c2). From the misorientation angle distributions, different types of bainite can be distinguished, including upper bainite, granular bainite, and lower bainite [18,19]. Upper bainite is characterized by a high fraction of low-angle boundaries and few high-angle boundaries, whereas lower bainite shows the opposite. Granular bainite exhibits a more random distribution of boundary angles, typically showing a broad peak in the high-angle region and a small peak in the low-angle region.

Figure 5.

EBSD inverse pole figure maps (a1–c1), bainitic lath/block boundary maps (a2–c2), and misorientation distribution maps (a3–c3) of the samples: (a) AT400; (b) AT380; (c) AT360.

As shown in Figure 5(a3–c3), the AT400 sample exhibits a high fraction of high-angle boundaries (49.6%), a lower fraction of low-angle boundaries (35.4%), and an even smaller fraction of medium-angle boundaries (14.0%). As the austempering temperature decreases from 400 °C to 380 °C and 360 °C, the fraction of low-angle boundaries gradually declines, the fraction of high-angle boundaries increases, and the fraction of medium-angle boundaries remains nearly unchanged. Consequently, the AT400 sample contains the smallest amount of lath bainite, the AT360 sample contains the largest amount, and the AT380 sample is intermediate.

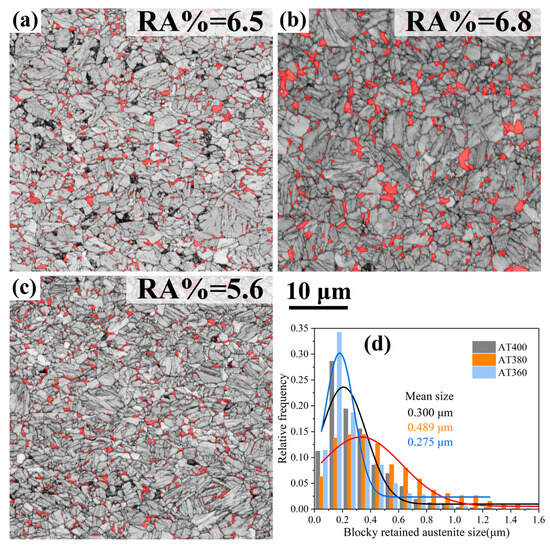

Figure 6a–c present the overlay of contrast maps and phase maps derived from EBSD data, revealing the distribution of retained austenite (RA) in the samples. It should be noted that blocky RA with much smaller sizes and nanoscale RA films exceed the resolution of EBSD; thus, only large blocky RA (>60 nm) is detected. The size distribution of blocky RA at different austempering temperatures is shown in Figure 6d. In AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples, blocky RA exhibits a similar distribution pattern, with most located near the prior austenite grain boundaries and a few distributed within the grains. The average sizes of blocky RA in AT400, AT380, and AT360 are 0.300 μm, 0.489 μm, and 0.275 μm, respectively. Clearly, austempering slightly below Ms results in finer blocky RA.

Figure 6.

Blocky retained austenite (RA) distribution derived from EBSD data for the samples: (a) AT400; (b) AT380; (c) AT360; (d) presents the size distribution statistics of the blocky retained austenite in each sample.

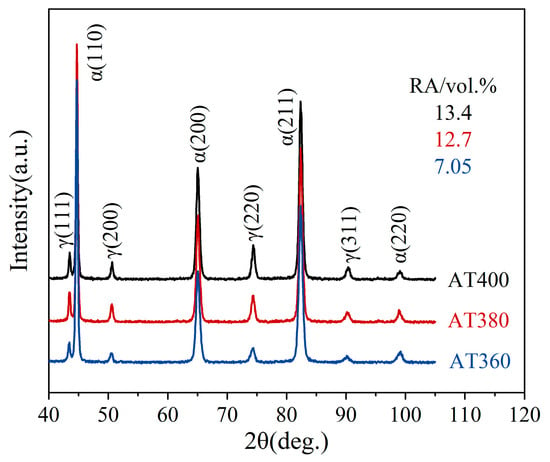

Figure 7 shows the XRD patterns of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples. The retained austenite (RA) contents in AT400, AT380, and AT360 are 13.4%, 12.7%, and 7.9%, respectively, with corresponding average carbon contents of 0.98 wt.%, 1.04 wt.%, and 1.09 wt.%. As the austempering temperature decreases, the RA content gradually declines, while the average carbon content increases.

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples.

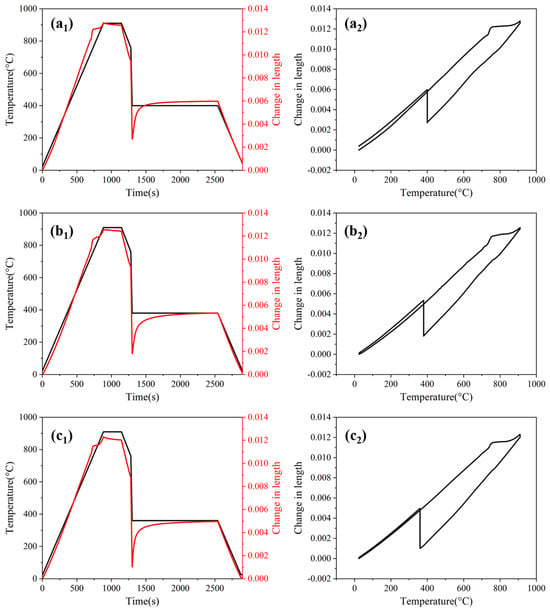

3.3. Phase Transformation Behaviors

Figure 8 shows the dilatation curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 processes. The phase transformation behaviors during the designed austempering process may involve five types of transformations, which occur at different stages. During the initial heating and holding stages, austenite transformation takes place. In the quenching stage prior to isothermal bainitic transformation, ferrite, pearlite and martensite may form. During holding at 400 °C, 380 °C, or 360 °C, isothermal bainitic transformation occurs. Finally, in the final quenching stage, martensitic transformation occurs under continuous cooling.

Figure 8.

Dilatation curves for the processes: (a1) Dilatation–time and (a2) dilatation–temperature curves for AT400; (b1,b2) for AT380; (c1,c2) for AT360.

To examine the microstructural state before isothermal bainitic transformation, a direct quenching process without any isothermal transformation was designed (Figure 9a). Samples produced under this process were characterized by SEM to observe the microstructure and by XRD to determine the retained austenite content. As shown in Figure 9b,c, the as-quenched microstructure contains approximately 6 vol.% ferrite, while the retained austenite content is nearly zero.

Figure 9.

(a) Process route for direct quenching to room temperature without isothermal transformation; (b) SEM microstructure of the as-quenched sample; (c) XRD pattern of the as-quenched sample.

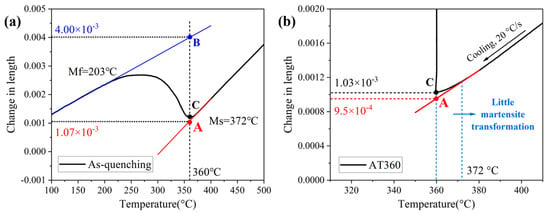

The formation of a small amount of athermal martensite in AT360 occurs during the cooling process prior to the isothermal holding stage. These athermal martensite also exist in the as-quenched sample. Here, the content of athermal martensite is calculated using the lever rule [20,21,22] based on the dilatation curves of the as-quenched sample and AT360. As shown in Figure 10a, the athermal martensite content is obtained as the percentage of the length change corresponding to segment AC relative to that of segment AB, where the length change of segment AC represents the expansion associated with the formation of athermal martensite. According to Figure 10b, the length change in AT360 corresponding to the formation of athermal martensite is approximately 8 × 10−5. It should be noted that the microstructure of the quenched sample contains 6% ferrite. Therefore, the content of athermal martensite in AT360 can be calculated as [8 × 10−5/(4.00 × 10−3 − 1.07 × 10−3)] × 94% ≈ 2.7%.

Figure 10.

(a) Demonstration of the lever rule calculation based on the dilatation curve of the as-quenched sample; (b) length change caused by the formation of athermal martensite in the AT360 sample.

The following sections separate bainitic transformation during the isothermal holding stage and the martensitic transformation during the final cooling stage, and carefully examines the differences among the AT400, AT380, and AT360 processes.

3.3.1. Bainitic Transformation Behavior

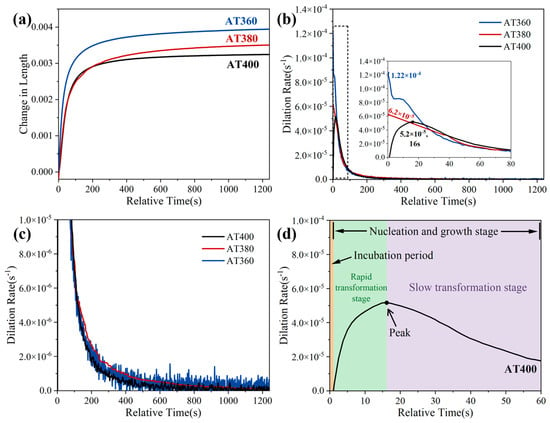

Figure 11a shows the dilatation curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples during the isothermal bainitic transformation. Figure 11b presents the corresponding curves of dilatation rate versus holding time. The change in dilatation reflects the extent of bainitic transformation, while the dilatation rate indicates the transformation kinetics. Additionally, Figure 11d uses the dilatation rate curve of the AT400 sample as an example to illustrate how the different stages of the bainite transformation are mapped onto the curve. The bainite transformation typically consists of three stages: the incubation period, the nucleation stage, and the growth stage [23]. In the dilatation curve, the transformation kinetics are generally reflected by a rapid transformation stage (usually corresponding to nucleation and the early growth stage) followed by a slow growth stage (typically corresponding to the later growth stage) [24].

Figure 11.

(a) Dilatation curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples during the isothermal bainite transformation; (b) corresponding dilatation rate curves; (c) a magnified view of (b); (d) an example using the dilatation rate curve of the AT400 sample to illustrate how the different stages of the bainite transformation are mapped onto the curve.

From Figure 11a, it can be seen that the amount of bainite formed during the entire isothermal holding period gradually increases as the austempering temperature decreases. It should be noted that, compared with AT400, AT380 forms less bainite in the early stage of isothermal holding, but its bainite fraction gradually catches up and eventually surpasses that of AT400 as the holding time increases. In contrast, AT360 consistently exhibits the highest bainite fraction throughout the holding stage until the end of austempering.

Based on the bainite-transformation stages shown in Figure 11d, together with the transformation-rate curves in Figure 11b, it can be observed that AT400 exhibits a very short incubation period (~1 s), whereas the other samples show no detectable incubation period. The bainite transformation rate of AT400 follows a trend in which it first increases to a peak (5.2 × 10−5 s−1) and then slowly decreases. In contrast, the transformation rates of AT380 and AT360 decrease directly from the beginning. Compared with AT380 (6.2 × 10−5 s−1), AT360 shows a higher initial transformation rate (1.22 × 10−4 s−1), features an additional plateau, and then drops more rapidly.

According to Figure 11c, the time required for the bainite transformation to approach completion can be ranked from shortest to longest as AT400 < AT380 ≈ AT360. AT400 is the first to reach the near-completion stage of bainite transformation. It is also noted that the later-stage transformation of AT360 proceeds extremely slowly, ultimately approaching the same level as AT380.

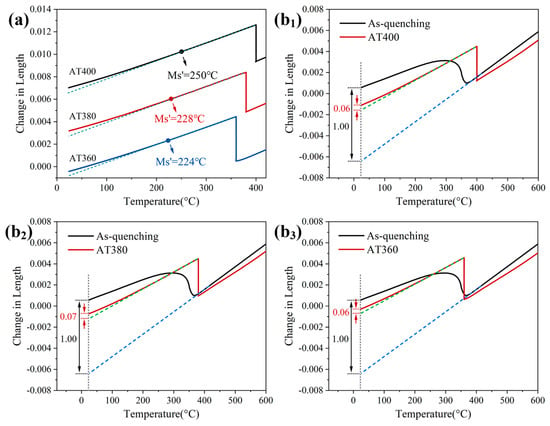

3.3.2. Martensitic Transformation Behavior

Figure 12a shows the dilatation curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples during the final quenching stage. It can be seen that as the austempering temperature decreases, the dilatation curves gradually deviate from their original linear behavior, and the deviation becomes more pronounced at lower temperatures. This is caused by the expansion associated with martensitic transformation of the undercooled austenite. By extending the initial linear portion of the final cooling stage to room temperature, the martensite start temperature (Ms′) can be estimated. The Ms′ for AT400, AT380, and AT360 are 250 °C, 228 °C, and 224 °C, respectively.

Figure 12.

(a) Dilatation curves of the AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples during the final quenching stage; (b1–b3) Determination of the fresh martensite content in the austempered samples by comparing the dilatation curves of direct-quenched and austempered samples: (b1) AT400, (b2) AT380, and (b3) AT360.

In addition, the amount of fresh martensite formed in the austempered samples was estimated following a literature method [25,26,27]. Directly quenched samples contain 6% ferrite, with the remainder as martensite. Figure 12(b1–b3) show comparisons of the dilatation curves between directly quenched and austempered samples for AT400, AT380, and AT360. By comparing the expansion due to martensitic transformation under the two processes, the ratios (DIL%) are calculated as 5.9%, 6.8%, and 5.9%, respectively. Accordingly, the amounts of fresh martensite in the AT400, AT380, and AT360 austempered samples are 5.5%, 6.4%, and 5.5%, respectively.

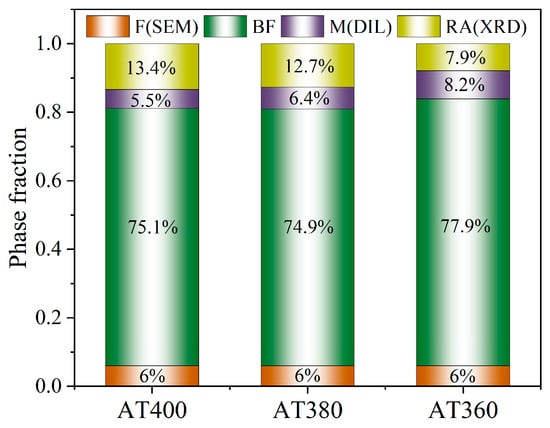

Based on the above data, the contents of ferrite, martensite, and retained austenite in the samples have all been determined. The amount of bainitic ferrite can then be calculated indirectly by excluding the contents of these phases. Accordingly, the bainitic ferrite fractions in AT400, AT380, and AT360 are 75.1%, 74.9%, and 77.9%, respectively. Using the phase fractions in each sample, Figure 13 is plotted to facilitate subsequent discussion and analysis.

Figure 13.

The phase fractions of AT400, AT380, and AT360 samples. F: ferrite; BF: bainite ferrite; M: martensite; RA: retained austenite.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Austempering Temperature on Bainitic Transformation

Based on the dilatation results, lowering the isothermal austempering temperature can accelerate the early-stage kinetics of bainitic transformation, while the later-stage kinetics appear to slow down. When isothermal austempering is conducted near and below Ms, the initial stage of bainitic transformation is significantly accelerated. The mechanism of bainitic transformation is still not fully established [28,29]. However, it is widely accepted [30,31] that bainitic transformation involves both a shear-type displacive process and accompanying carbon diffusion. Carbon diffusion refers to the process in which carbon atoms in the already formed bainitic ferrite diffuse into the regions of untransformed austenite, leading to carbon enrichment in the austenite. Based on these reported results in the literature, it can be concluded that the transformation driving force and carbon diffusion capability are key factors influencing bainitic transformation.

Previous studies [32,33,34] have shown that the driving force for bainitic transformation increases as the isothermal transformation temperature decreases. In the present study, as the isothermal austempering temperature was gradually reduced from 400 °C to 380 °C and 360 °C, the driving force for bainitic transformation correspondingly increased. An increased transformation driving force promotes the nucleation of bainitic ferrite and the migration of interfaces. Therefore, in theory, lowering the isothermal temperature should accelerate the overall kinetics of bainitic transformation.

However, in practice, decreasing the isothermal temperature only accelerates the early-stage kinetics, while the later-stage kinetics do not increase and may even slow down. This is because the reduced carbon diffusion capability significantly hinders the later-stage bainitic transformation, specifically by limiting the growth of the bainitic laths [35,36]. Compared with AT400, the isothermal bainitic transformation temperature of AT380 is lower, which implies that the diffusion of carbon from bainite into austenite is less effective. Carbon atoms more readily accumulate at the interfaces between bainite ferrite and austenite. Over time, the carbon concentration at the interfaces continues to rise, increasing the thermal stability of the adjacent austenite and ultimately reducing the driving force for further bainitic transformation.

It is thus evident that the carbon diffusion capability constrains the beneficial effect of the transformation driving force on bainitic transformation. As the isothermal temperature decreases further, although the driving force increases, the carbon diffusion capability simultaneously diminishes. This is a very likely reason why the later-stage transformation kinetics of AT380 remain slow compared with AT400.

In addition, it is noted that the AT360 sample exhibits the fastest initial kinetics of bainitic transformation. This is not only related to the enhanced transformation driving force, but also closely associated with the presence of athermal martensite. Several studies [37,38,39] have reported that pre-existing martensite can significantly accelerate subsequent isothermal bainitic transformation. It is convincing that the presence of martensite introduces new martensite/austenite interfaces, which act as heterogeneous nucleation sites for bainite, thereby substantially promoting bainite nucleation [40,41]. Furthermore, some reports [42,43] indicate that the formation of martensite generates strain fields near the interfaces, which can increase the nucleation rate of bainite.

Compared with most previous studies, in the present work, the AT360 sample underwent bainitic transformation near and below Ms, resulting in a very small fraction of athermal martensite (~3%). However, the presence of even a small amount of martensite is not negligible in accelerating bainitic transformation. It is noteworthy that the early-stage bainitic transformation in AT360 exhibits a burst-like kinetic, followed by a rapid decrease, then a short plateau, and finally a slow decline. The appearance of the plateau suggests that multiple factors simultaneously promote bainitic transformation. The driving force for bainitic transformation gradually decreases as the transformation proceeds, owing to carbon enrichment in the remaining untransformed austenite. According to the study by Navarro-López et al. [39], even a small amount of pre-existing martensite can increase the bainite nucleation rate by several orders of magnitude compared with the absence of pre-martensite. This observation is consistent with the behavior of the AT360 sample.

Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that, in the AT360 sample, an additional factor—the pre-formed martensite—contributes to the kinetics of bainitic transformation.

However, in terms of the bainitic ferrite content, the AT400 and AT380 samples appear to show little difference, whereas the AT360 sample exhibits a relatively higher content. The bainitic transformation in AT400 and AT380 is primarily influenced by the transformation driving force and carbon diffusion capability. Based on the dilatation rate curves, compared with AT400, the early-stage bainitic transformation in AT380 is faster, while the later-stage transformation is slower, which can be attributed to the increased driving force and reduced carbon diffusion capability, respectively. It is possible that the effects of these two factors partially counterbalance each other. The likely reason why the AT360 sample has the highest bainitic ferrite content is the additional promoting factor—the presence of athermal martensite as repeatedly mentioned above.

4.2. Effect of Austempering Temperature on Microstructure-Mechanical Properties Relationship

The tensile test results indicate that as the austempering temperature decreases, the strength of the samples increases monotonically, while the elongation shows the opposite trend. The AT400 sample exhibits the highest strength–ductility product (18.9 GPa·%), but its yield-to-tensile strength ratio is unsatisfactory. In contrast, the AT380 and AT360 samples have higher yield-to-tensile ratios, with elongation remaining within an acceptable range. Lowering the temperature from slightly above Ms (380 °C) to below Ms (360 °C) further improves both the yield-to-tensile ratio and strength without significantly compromising ductility. These results suggest that austempering slightly below Ms can achieve an optimal combination of mechanical properties.

The differences in mechanical properties are closely related to phase composition and microstructural features. As shown in Figure 13, with decreasing austempering temperature, the amount of bainite increases, the retained austenite fraction decreases, and the amount of fresh martensite changes little. EBSD analysis indicates that lower austempering temperatures lead to more lath bainite formation. In AT380, the increase in bainitic laths is associated with the higher driving force for transformation. For AT360, the increase is attributed to a higher nucleation rate, resulting in more parallel-arranged bainitic ferrite subunits within the grains [44]. The reduction in retained austenite is due to the increased extent of bainitic transformation, leaving less untransformed austenite.

Overall, the increase in strength can be attributed to the higher bainite fraction and the greater proportion of lath bainite. The decrease in elongation is mainly due to the reduction in retained austenite content. Compared with AT380, the elongation of AT360 sample does not decrease significantly because the morphology and size of retained austenite differ. Large blocky retained austenite has poor mechanical stability and tends to transform early via the TRIP effect during the initial stage of tensile deformation, leading to rapid consumption [45]. In contrast, fine blocky retained austenite is mechanically more stable and transforms gradually under higher accumulated strain. In AT380, the coarser retained austenite induces a concentrated TRIP effect in the early deformation stage, but its high content maintains good elongation. For AT360, although the retained austenite content is much lower, it can still provide a TRIP effect in the later deformation stage, helping to relieve stress concentrations and resulting in appreciable elongation.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the phase transformation behaviors, microstructure, and mechanical properties of an experimental steel with the composition Fe-0.2C-1.3Si-1.9Mn-0.05V-0.05Ti-0.17Mo (wt.%) under austempering at different temperatures (360 °C, 380 °C, and 400 °C) near Ms (372 °C). The effects of isothermal treatment slightly above and below Ms on bainitic transformation kinetics and the microstructure–property relationship were systematically examined. The key conclusions are as follows:

- Compared with treatments slightly above Ms (380 °C and 400 °C), austempering slightly below Ms (360 °C) achieves the highest yield-to-tensile ratio and good strength–ductility balance. The increase in strength is attributed to the higher bainite fraction and the greater proportion of lath bainite, while the decrease in elongation is due to reduced retained austenite content;

- Dilatation curves indicate that the early-stage bainitic transformation is fastest under austempering slightly below Ms. The stronger transformation driving force and the presence of athermal martensite are the primary reasons. For treatments slightly above Ms, lowering the austempering temperature slightly accelerates the early-stage bainitic transformation kinetics but slows down the later stage, due to the increased transformation driving force and reduced carbon diffusion capability, respectively;

- The increase in the driving force for bainitic transformation and the higher number of nucleation sites promote the formation of more bainitic laths within individual austenite grains. AT360 contains the highest fraction of lath bainite, resulting in the finest blocky retained austenite;

- Compared with AT380, the finer blocky retained austenite in AT360 explains why elongation is not significantly compromised despite the notable reduction in retained austenite content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z., Z.L. and X.H. (Xuefei Huang); methodology, H.Z. and Z.L.; formal analysis, H.Z. and Z.L.; investigation, H.Z. and Z.L.; resources, H.F., X.H. (Xiao Hu), G.S., Y.J., H.W. and T.X.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., Z.L. and X.H. (Xuefei Huang); visualization, Z.L. and X.H. (Xuefei Huang); supervision, X.H. (Xuefei Huang); project administration, H.Z. and X.H. (Xuefei Huang); funding acquisition, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “the Major Science and Technology Research Project in Panxi Experimental Area of Sichuan Province (the sixth batch of project)”, which was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to liuzhixiang@stu.scu.edu.cn (Z.L.).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from “the Major Science and Technology Research Project in Panxi Experimental Area of Sichuan Province (the sixth batch of project)”. The authors appreciate Wang Hui from the Analytical & Testing Center of Sichuan University for her help with EBSD characterization. Also, gratefully thank Chen Shu from the Analytical & Testing Center of Panzhihua Iron and Steel Research Institute Co., Ltd., Pangang Group for his help with SEM characterization and EBSD preparation. Finally, sincerely thank Zhang Jie and Zhang Xiaoshan from the college of Materials Science and Engineering of Sichuan University for their help with dilatometric experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Haoqing Zheng, Xiao Hu, Guanqiao Su, Yang Jin and Tao Xie were employed by the company Panzhihua Iron and Steel Research Institute Co., Ltd. Authors Hua Fan and Hongwei Wang were employed by the company Pangang Group Xichang Steel & Vanadium Co., Ltd. Authors Zhixiang Liu and Xuefei Huang declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Yu, S.; Wang, C. Microstructural evolution and mechanical behaviors of the third–generation automobile QP980 steel under continuous tension and compression loads. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 883, 145533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J. Advanced lightweight materials for automobiles: A review. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, D.; Wang, R.; Wang, T.; Di, H.; Yi, H. Improving fracture strain of carbide-free bainitic steel via deformation-induced microstructure refinement and homogenization. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Chen, H.; Ding, R.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Z.; van der Zwaag, S. Fundamentals and application of solid-state phase transformations for advanced high strength steels containing metastable retained austenite. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2021, 143, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhu, G.; Dai, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C. Improving strength-toughness of low carbon bainitic microalloyed steel via tailoring isothermal quenching process and niobium microalloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 901, 146515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, M.; Pezzato, L.; Gennari, C.; Hanoz, D.; Bertolini, R.; Fabrizi, A.; Polyakova, M.; Brunelli, K.; Bonollo, F.; Dabalà, M. Influence of austempering temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-Silicon carbide-free bainitic steel. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2200821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Mostert, R.; Aarnts, M. Heat treatment effects on microstructure and properties of advanced high-strength steels. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 2642–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hojo, T.; Koyama, M.; Akiyama, E. Effect of austempering treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 0.4C–1.5Si-1.5Mn TRIP-aided bainitic ferrite steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 819, 141479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, C.; Winkelhofer, F.; Clemens, H.; Primig, S. Morphology change of retained austenite during austempering of carbide-free bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 664, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tripathi, A.; Dwivedi, R.K.; Arya, R.K.; Yadav, A.S.; Agarwal, A. Influence of austempering temperature on carbide free bainite development, a critical review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2484, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr El-Din, H.; Showaib, E.A.; Zaafarani, N.; Refaiy, H. Structure-properties relationship in TRIP type bainitic ferrite steel austempered at different temperatures. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2017, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Lan, H.; Tao, Z.; Qi, M.; Du, L. Microstructure, crystallography, mechanical and damping properties of a low-carbon bainitic steel austempered at various temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 19068–19087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Mostert, R.; Aarnts, M. Microstructure and properties of an advanced high-strength steel after austempering treatment. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 37, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Z. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 18Mn3Si2CrMo steel subjected to austempering at different temperatures below Ms. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 724, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Xu, G.; Zhou, M.; Hu, H. Refined Bainite Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a High-Strength Low-Carbon Bainitic Steel Treated by Austempering Below and Above MS. Steel Res. Int. 2018, 89, 1700469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.K.; Murdock, D.C.; Mataya, M.C.; Speer, J.G.; Matlock, D.K. Quantitative measurement of deformation-induced martensite in 304 stainless steel by X-ray diffraction. Scr. Mater. 2004, 50, 1445–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gui, X.; Bai, B.; Gao, G. Effect of tempering on the stability of retained austenite in carbide-free bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 850, 143525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Barbier, D.; Iung, T. Characterization and quantification methods of complex BCC matrix microstructures in advanced high strength steels. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 48, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, S.; Schwinn, V.; Tacke, K.H. Characterisation and quantification of complex bainitic microstructures in high and ultra-high strength linepipe steels. Mater. Sci. Forum 2005, 500–501, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kop, T.A.; Sietsma, J.; Van Der Zwaag, S. Dilatometric analysis of phase transformations in hypo-eutectoid steels. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.-W.; Oh, C.-S.; Han, H.N.; Kim, S.-J. Dilatometric analysis of austenite decomposition considering the effect of non-isotropic volume change. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 2659–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, B. Dilatometric Analysis and Kinetics Research of Martensitic Transformation under a Temperature Gradient and Stress. Materials 2021, 14, 7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, F.; Long, X. In situ observation of bainitic transformation behavior in medium carbon bainitic steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Yang, R.; Sun, D.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y. Roles of cooling rate of undercooled austenite on isothermal transformation kinetics, microstructure, and impact toughness of bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 870, 144821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qian, L.; Wei, C.; Yu, W.; Ding, Y.; Ren, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Meng, J. Effect of prior austenite grain size on austenite reversion, bainite transformation and mechanical properties of Fe-2Mn-0.2C steel. Mater. Charact. 2024, 215, 114134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qian, L.; Wei, C.; Yu, W.; Ren, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Meng, J. Effects of above- or below-Ac3 austenitization on bainite transformation behavior, microstructure and mechanical properties of carbide-free bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 888, 145814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.; Kumar, S.; Chakrabarti, D.; Singh, S.B. Effect of prior austenite grain size on the formation of carbide-free bainite in low-alloy steel. Philos. Mag. 2020, 100, 2320–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, L.C.D. The Bainite Controversy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Bainite—Unanswered questions and why they matter. Proc. Int. Symp. Steel Sci. 2024, 2024, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.-j.; Wang, S.-z.; Wu, G.-l.; Gao, J.-h.; Yang, X.-s.; Wu, H.-h.; Mao, X.-p. Application of phase-field modeling in solid-state phase transformation of steels. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2022, 29, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Song, R.; Yu, P.; Huo, W.; Qin, S.; Liu, Z. Phase Transformation and Precipitation Mechanism of Nb Microalloyed Bainite–Martensite Offshore Platform Steel at Different Cooling Rates. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1900224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, L.; Kolmskog, P.; Höglund, L.; Hillert, M.; Borgenstam, A. Critical Driving Forces for Formation of Bainite. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 4509–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtacha, A.; Kozlowska, A.; Skowronek, A.; Gulbay, O.; Opara, J.; Gramlich, A.; Matus, K. Design concept and phase transformation study of advanced bainitic-austenitic medium-Mn steel. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morawiec, M.; Ruiz-Jimenez, V.; Garcia-Mateo, C.; Grajcar, A. Thermodynamic analysis and isothermal bainitic transformation kinetics in lean medium-Mn steels. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Chen, H.; Sun, J.; van der Zwaag, S.; Sun, J. Carbon solute drag effect on the growth of carbon supersaturated bainitic ferrite: Modeling and experimental validations. Acta Mater. 2024, 268, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrabah, I.-E.; Brechet, Y.; Hutchinson, C.; Zurob, H. On the origin of carbon supersaturation in bainitic ferrite. Scr. Mater. 2024, 250, 116182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toji, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Raabe, D. Effect of Si on the acceleration of bainite transformation by pre-existing martensite. Acta Mater. 2016, 116, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avishan, B.; Mohammadzadeh Khoshkebari, S.; Yazdani, S. Effect of pre-existing martensite within the microstructure of nano bainitic steel on its mechanical properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 260, 124160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-López, A.; Sietsma, J.; Santofimia, M.J. Effect of Prior Athermal Martensite on the Isothermal Transformation Kinetics Below Ms in a Low-C High-Si Steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, A.M.; Navarro-López, A.; Sietsma, J.; Santofimia, M.J. Influence of martensite/austenite interfaces on bainite formation in low-alloy steels below Ms. Acta Mater. 2020, 188, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhara, S.; van Bohemen, S.M.C.; Santofimia, M.J. Isothermal decomposition of austenite in presence of martensite in advanced high strength steels: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrabah, I.-E.; Deboer, A.; Geandier, G.; Van Landeghem, H.; Hutchinson, C.; Brechet, Y.; Zurob, H. Effect of deformation on the bainitic transformation. Acta Mater. 2024, 277, 120195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Feng, X.; Zhao, A.; Li, Q.; Ma, J. Influence of Prior Martensite on Bainite Transformation, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties in Ultra-Fine Bainitic Steel. Materials 2019, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Lan, H.; Tao, Z.; Misra, R.D.K.; Du, L. Enhanced Strength and Toughness of Low-Carbon Bainitic Steel by Refining Prior Austenite Grains and Austempering Below Ms. Steel Res. Int. 2021, 92, 2100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-B.; Hu, C.-Y.; Hu, F.; Cheng, L.; Isayev, O.; Yershov, S.; Xiang, H.-J.; Wu, K.-M. Insight into the impact of microstructure on crack initiation/propagation behavior in carbide-free bainitic steel during tensile deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 846, 143175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).