Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties for Three Crystal Forms of Cordycepin and Their Interconversion Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Various Crystal Forms of Cordycepin

2.3. Crystal Transformation Testing: Slurry Conversion Experiments

2.4. Solubility Testing

2.5. Wettability Testing

2.6. Tablet Preparation and Dissolution Testing

2.7. Characterization

2.8. Calculation Methods

3. Results and Discussion

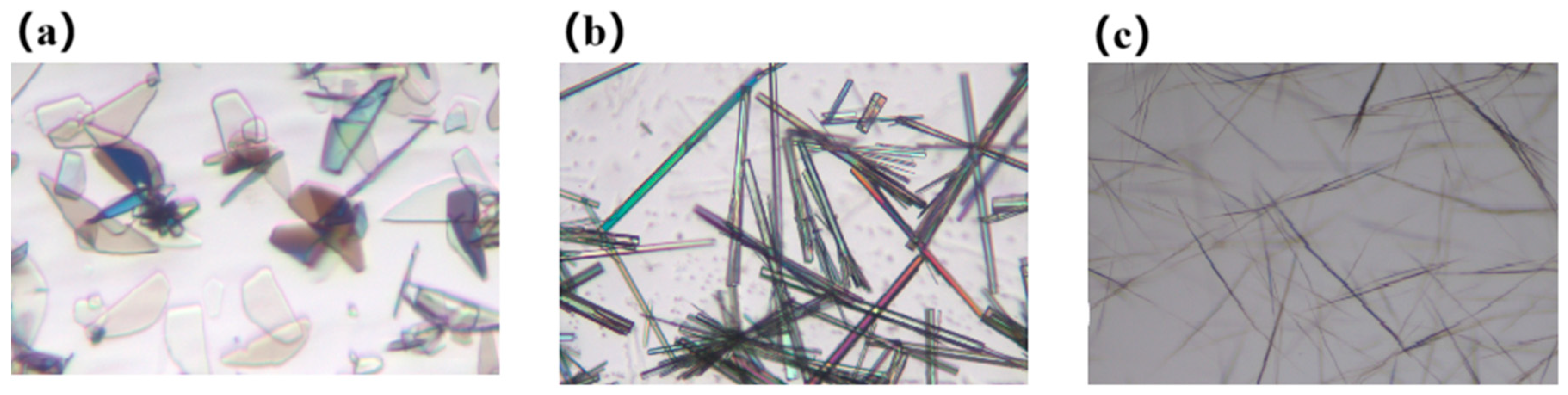

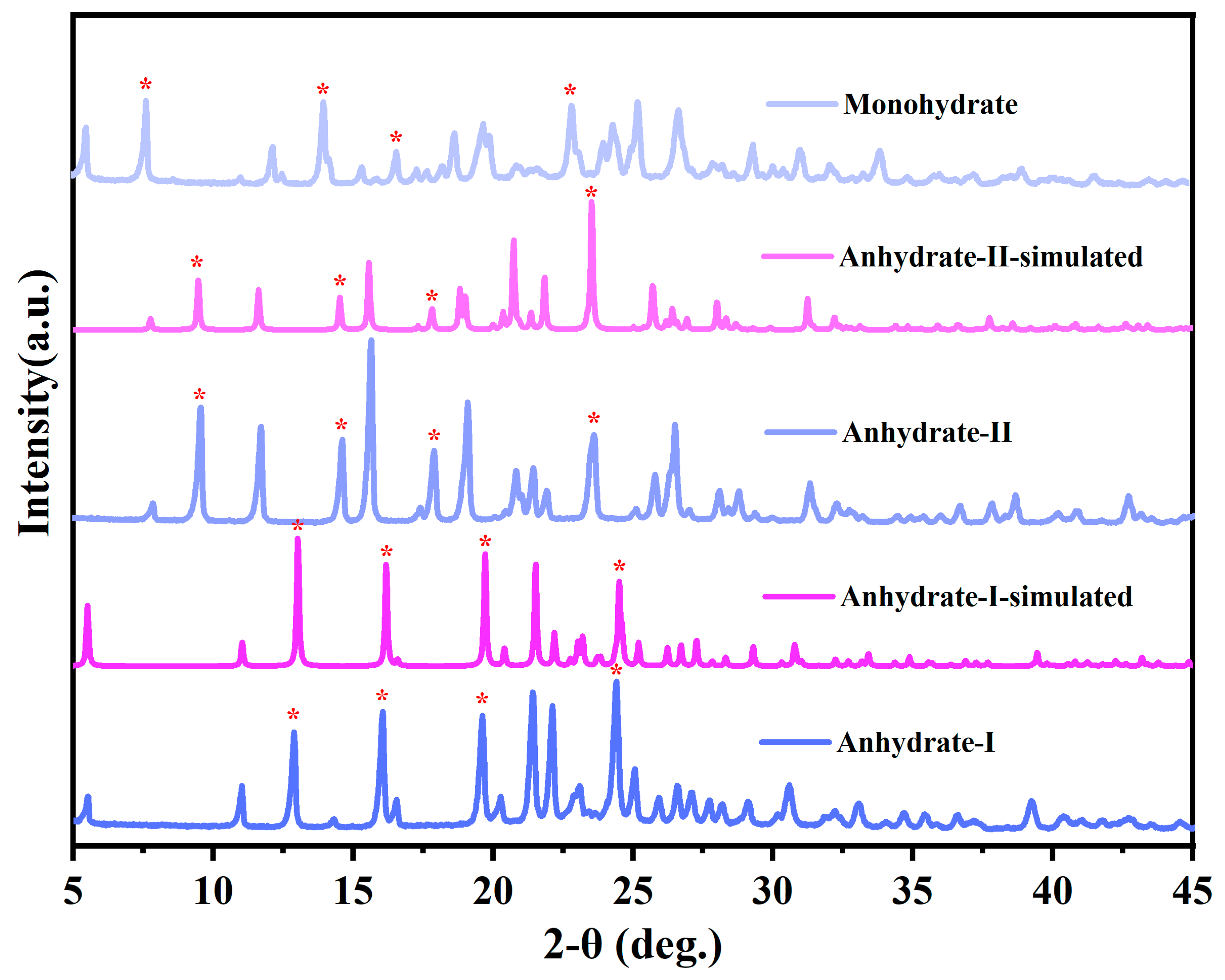

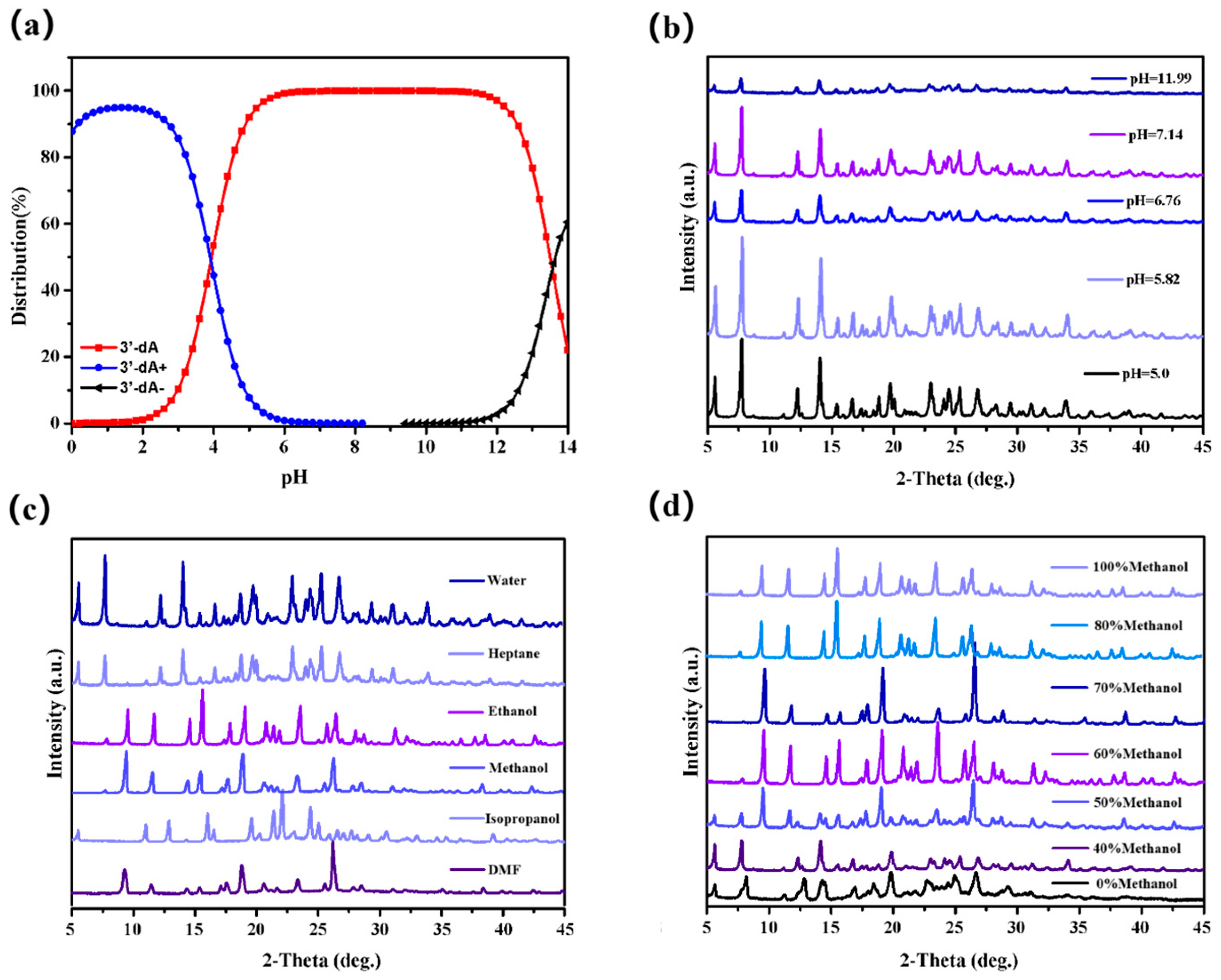

3.1. Morphology and PXRD Analysis of Various Solid Forms of Cordycepin

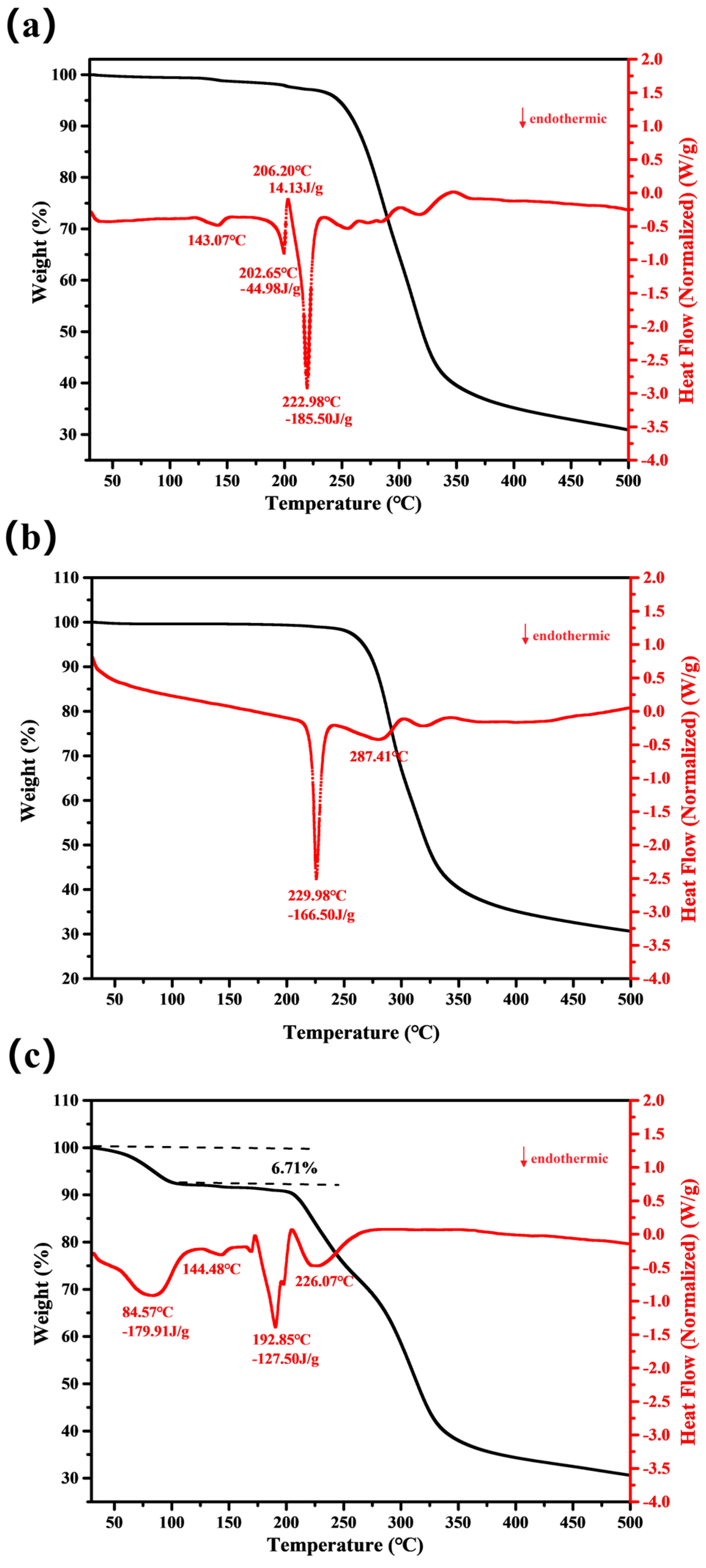

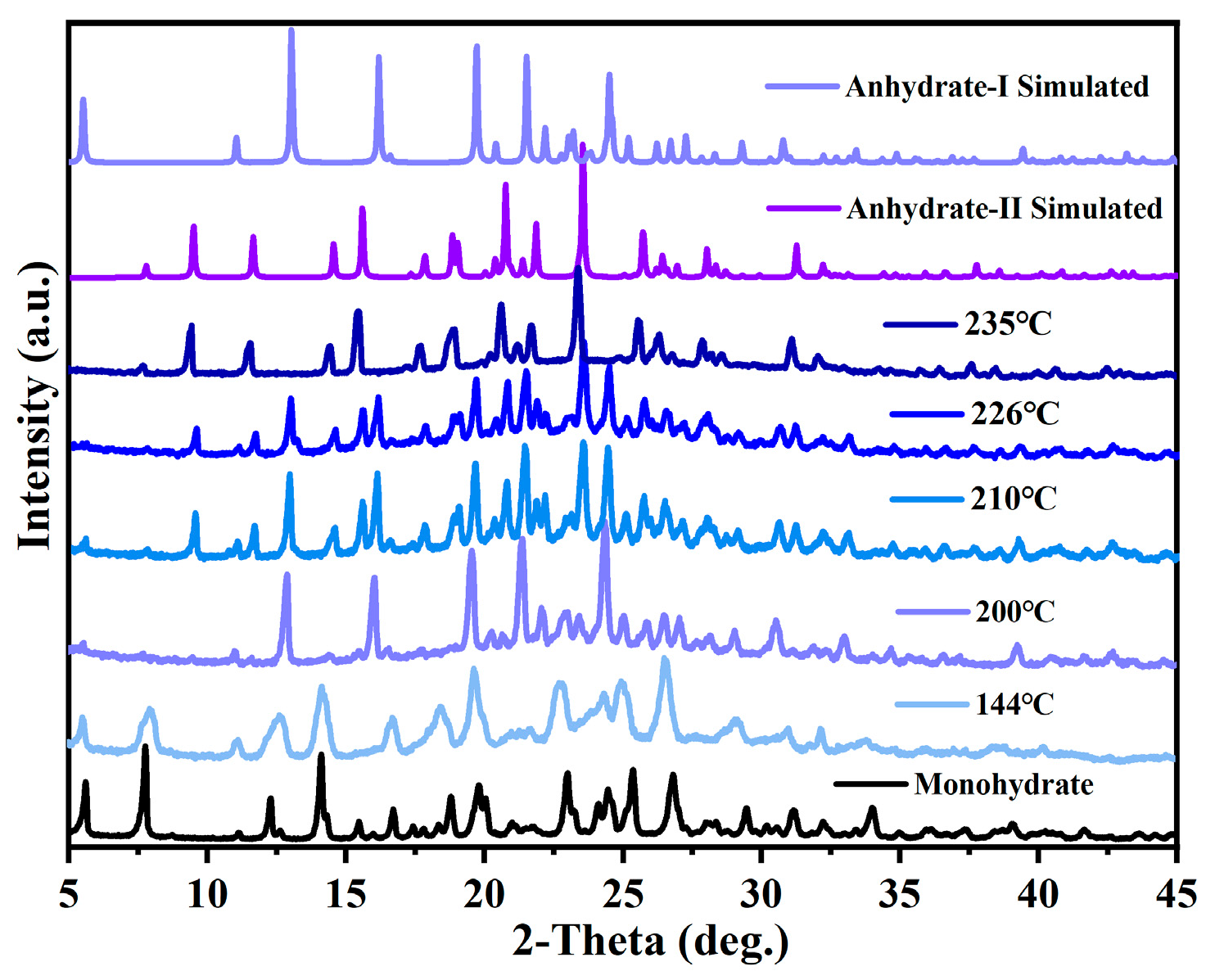

3.2. Thermodynamic Behaviors of the Three Crystal Forms

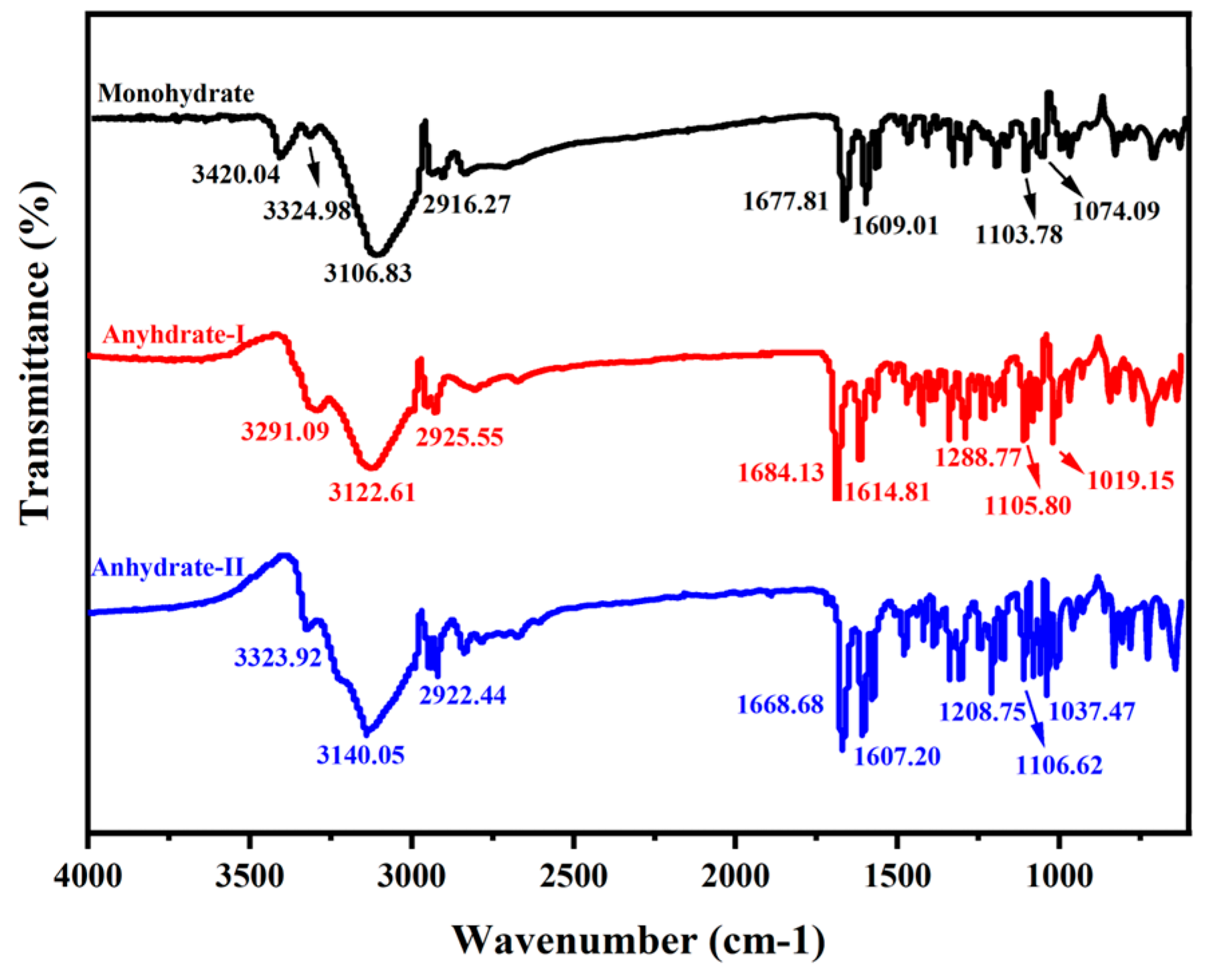

3.3. Comparative Infrared Spectra for Three Cordycepin Crystal Forms

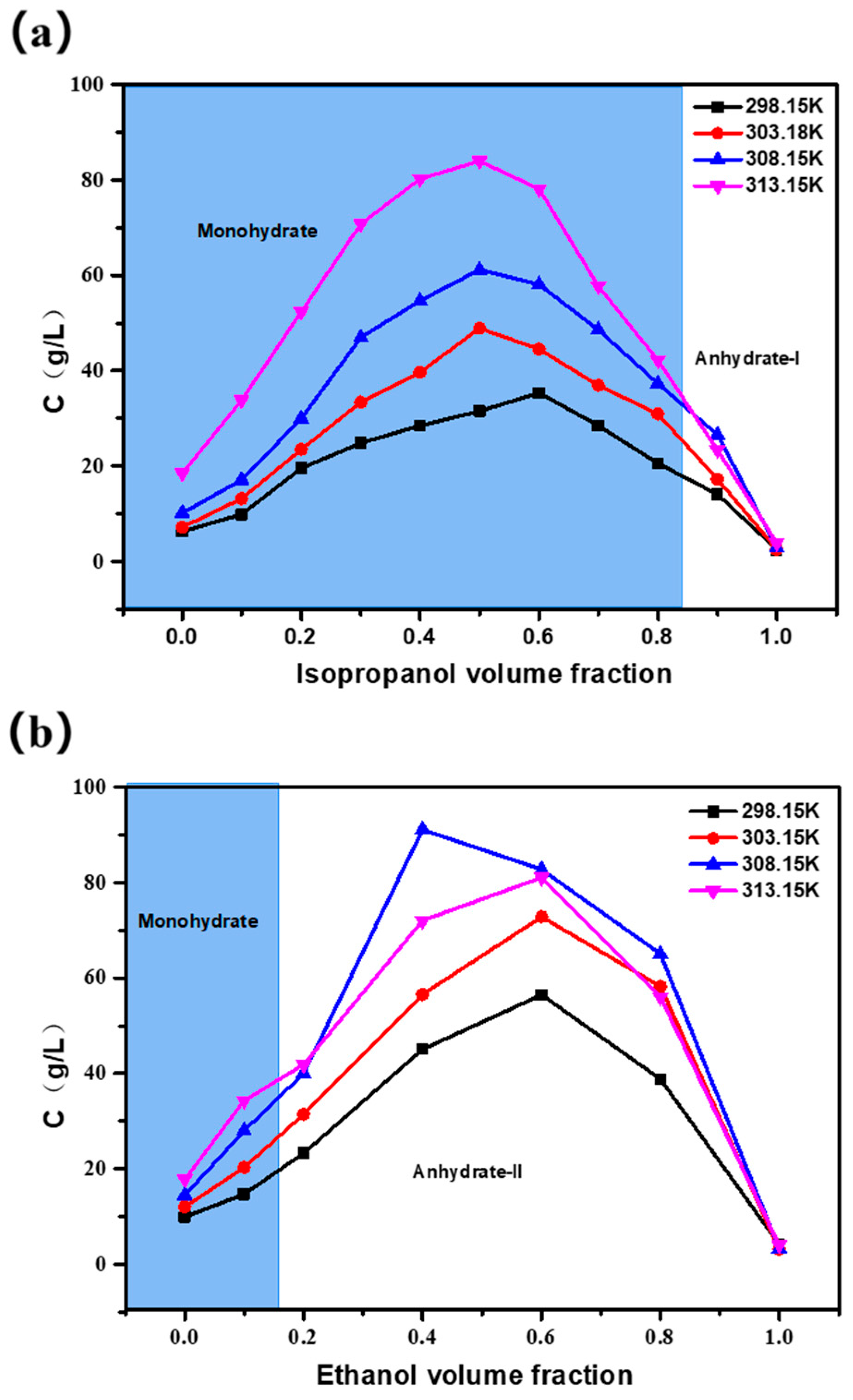

3.4. Influence of Water Activity on Solubility and Crystal Forms for Cordycepin

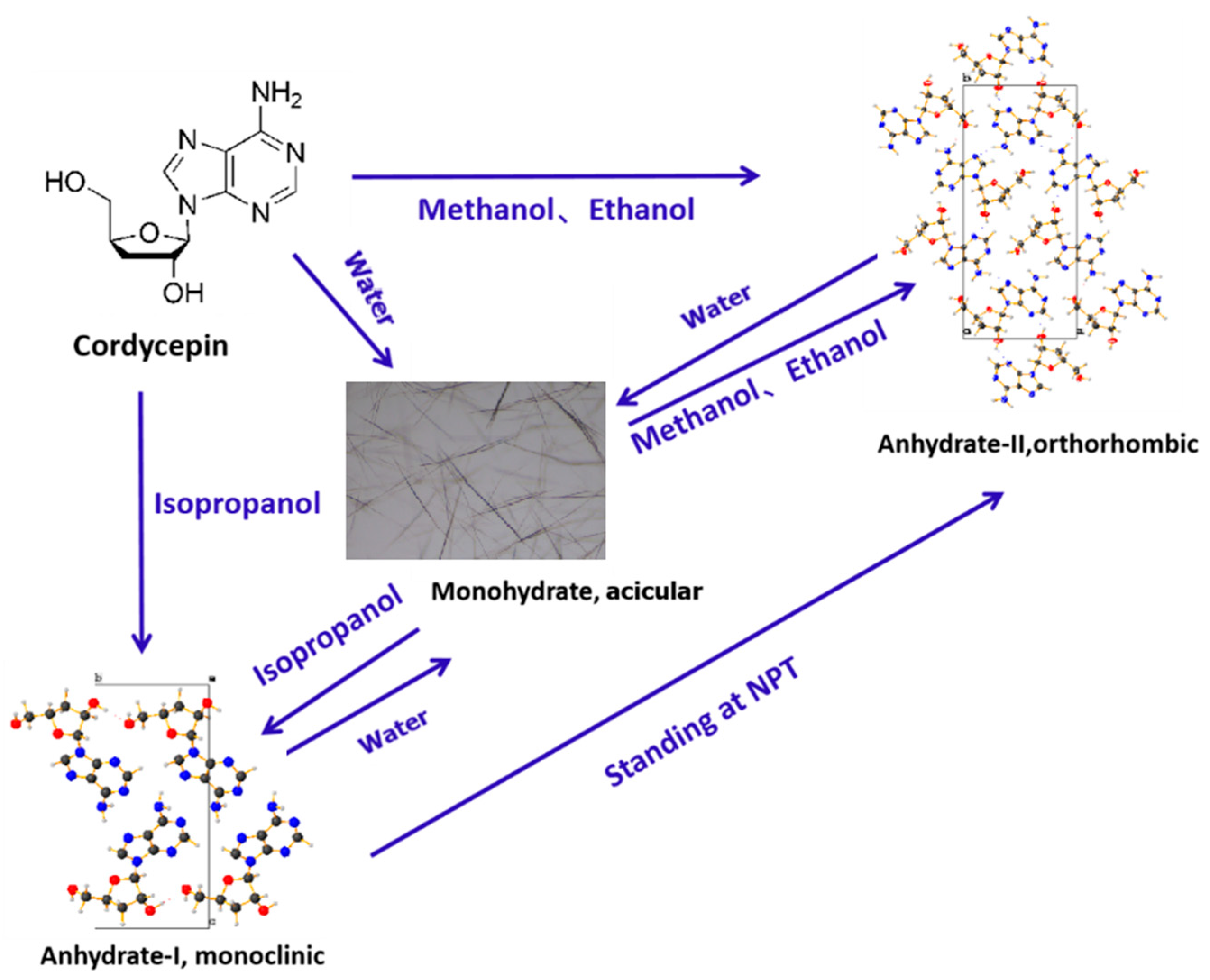

3.5. Transformation Relationship Among Various Cordycepin Crystal Forms

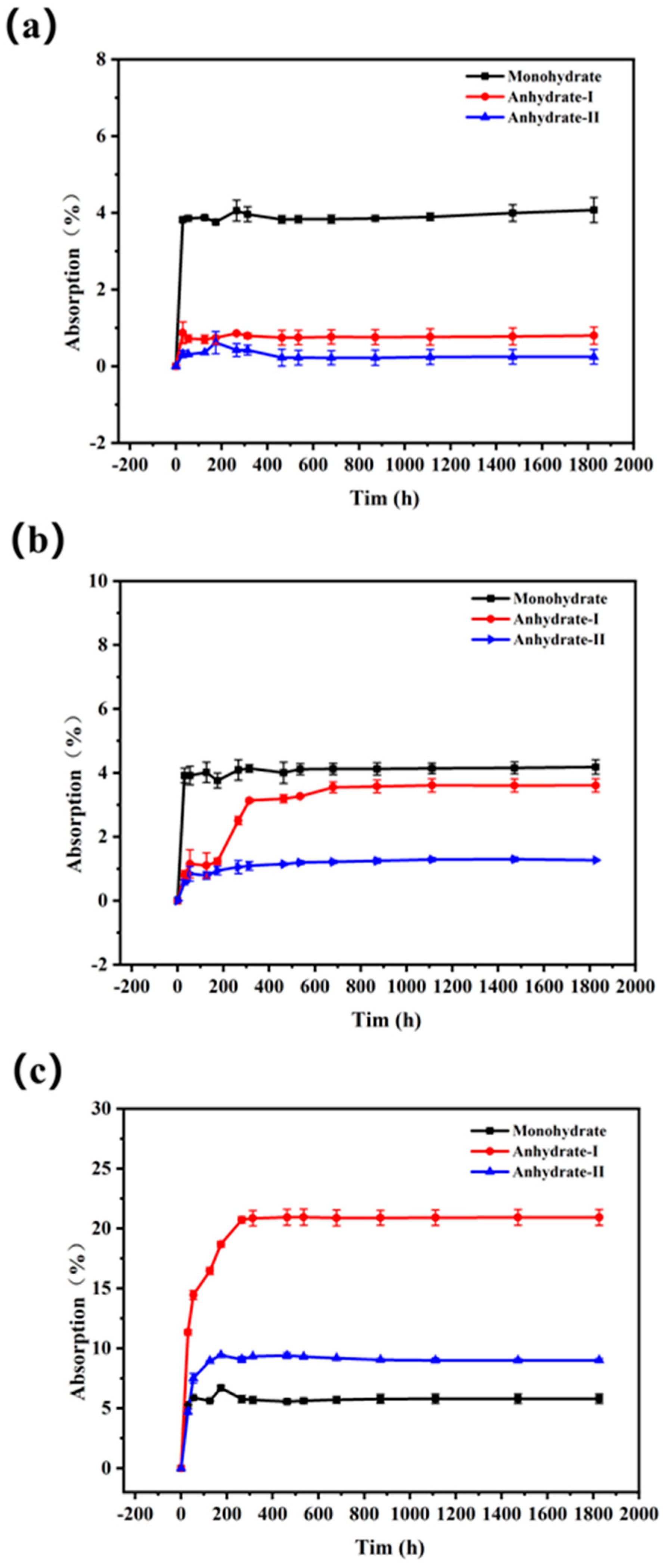

3.6. Hygroscopicity Experiments of Different Crystal Forms

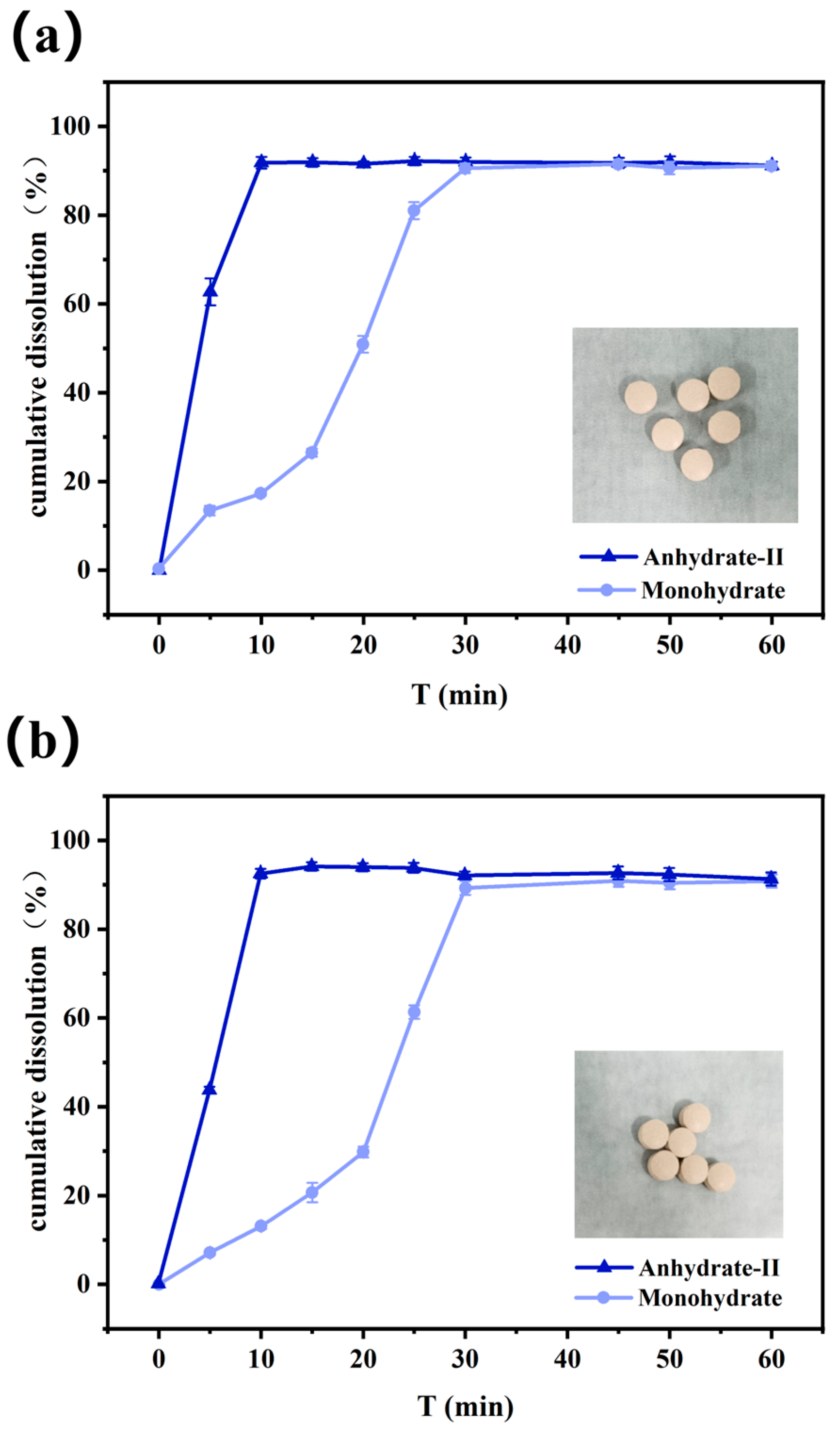

3.7. Dissolution Behaviors In Vitro of Anhydrate-II and Monohydrate of Cordycepin

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, Q.; Lou, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, C. Antimicrobial Effect and Proposed Action Mechanism of Cordycepin Against Escherichia Coli and Bacillus Subtilis. J. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, M.; Hui, W.; Feng, Y.; Lu, J.; Miranbieke, B.; Liu, H.; Gao, F. Cordycepin Exhibits Anti-bacterial and Anti-inflammatory Effects Against Gastritis in Helicobacter Pylori-Infected Mice. Pathog. Dis. 2022, 80, ftac005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.B.; Wang, H.X. Pharmacological actions of Cordyceps, a Prized Folk Medicine. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2005, 57, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Yang, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Ying, H.; Zheng, C. Quantitative Analysis of Cordycepin’s Solvent-Dependent Thermodynamics: Decoding Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions via COSMO-RS σ-profiling. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 438, 128727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, H.S.; Sharma, A.K.; Sandhu, S.S.; Kashyap, D. Cordycepin: A Bioactive Metabolite with Therapeutic Potential. Life Sci. 2013, 93, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottman, F.; Guarino, A.J. The Inhibition of Purine Biosynthesis de novo in Bacillus Subtilis by Cordycepin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1964, 80, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Y.; Liu, H.H.; Song, L.P.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Lu, X.Y.; Ji, X.J.; Tian, Y. Efficient Production of Cordycepin by Engineered Yarrowia Lipolytica from Agro-Industrial Residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 377, 128964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, M.; Das, S.K.; Hatashita, M.; Fujihara, S.; Sakurai, A. Efficient Production of Cordycepin by the Cordyceps Militaris Mutant G81-3 for Practical Use. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-J.; Lin, L.-C.; Tsai, T.-H. Pharmacokinetics of Adenosine and Cordycepin, a Bioactive Constituent of Cordyceps Sinensis in Rat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4638–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hate, S.S.; Thompson, S.A.; Singaraju, A.B. Impact of Sink Conditions on Drug Release Behavior of Controlled-Release Formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 114, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagden, N.; de Matas, M.; Gavan, P.T.; York, P. Crystal Engineering of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients to Improve Solubility and Dissolution Rates. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanan, Z.; Jingkang, W.; Yan, X.; Ting, W.; Xin, H. The Effects of Polymorphism on Physicochemical Properties and Pharmacodynamics of Solid Drugs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque-Flores, R.L.; Guzei, I.A.; Matos, J.d.R.; Yu, L. Polymorphs of the Antiviral Drug Ganciclovir. Acta Crystallogr. C 2017, 73, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, M.M.; Wilson, H.R. The Structure of Cordycepin. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1980, 36, 2185–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthe, P.; Gautham, N.; Kumar, A.; Katti, S.B. β-d-3′-Deoxyadenosine (Cordycepin). Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 1997, 53, 1694–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.; Ramberger, R. On the Polymorphism of Pharmaceuticals and Other Molecular Crystals. I: Theory of thermodynamic rules. Microchim. Acta 1979, 72, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanńska, U.; Kniaź, K. Solubility of Normal Alkanoic Acids in Selected Organic Binary Solvent Mixtures. Negative Synergetic Effect. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1990, 58, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, J.T.; Yalkowsky, S.H. Cosolvency and Cosolvent Polarity. Pharm. Res. 1987, 4, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemicals Reagents | Manufacturer | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Pure water | Prepared in our laboratory | 5.0 M Ω (20 °C) |

| Ultra-pure water Methanol Ethanol Isopropanol Cordycepin (standard) Cordycepin (crude) Cordycepin Sodium hydroxide Hydrochloric acid Phosphoric acid Starch Microcrystalline cellulose Mannitol | Prepared in our laboratory HUSHI HUSHI HUSHI Shanghai Yuan Ye LIFEGENERON Laboratory self-made Aladdin Mclean Mclean Laboratory self-made Shanghai Yuan ye Mclean | 18.2 M Ω (20 °C) GR, ≥99.7% AR, ≥99.7% AR, ≥99.7% ≥98% ≥85% ≥95% AR, ≥99.9% AR, ≥99.7% 85% HPLC ≥ 98% Food-level ≥98% |

| Edible alcohol | Hua Xing | 95% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Li, S.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Tang, C.; Zou, F.; Zhang, K.; Jiao, P.; Yang, P. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties for Three Crystal Forms of Cordycepin and Their Interconversion Relationship. Crystals 2025, 15, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121043

Li W, Li S, Wen Q, Zhang X, Zhang K, Tang C, Zou F, Zhang K, Jiao P, Yang P. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties for Three Crystal Forms of Cordycepin and Their Interconversion Relationship. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121043

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenbo, Shushu Li, Qingshi Wen, Xiaohan Zhang, Ke Zhang, Chenglun Tang, Fengxia Zou, Keke Zhang, Pengfei Jiao, and Pengpeng Yang. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties for Three Crystal Forms of Cordycepin and Their Interconversion Relationship" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121043

APA StyleLi, W., Li, S., Wen, Q., Zhang, X., Zhang, K., Tang, C., Zou, F., Zhang, K., Jiao, P., & Yang, P. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties for Three Crystal Forms of Cordycepin and Their Interconversion Relationship. Crystals, 15(12), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121043