Abstract

Yuanjiang County is one of the most important gem-producing areas in China. The authors of this study discovered and collected gem-quality andradite Garnsts in the epidote amphibolite from the periphery of the ruby deposit in Shaku Village, Yuanjiang County. After careful observation of the collected andradite, it was found that these andradite samples appear green when the thickness is less than 2 mm and reddish-brown when the thickness is greater than 2 mm, exhibiting the typical Usambara effect. To investigate the gemological and spectroscopic characteristics of Yuanjiang andradite, this study conducted basic gemological tests, microscopic observation, electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), ultraviolet–visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and laser Raman spectroscopy on the collected samples. Tests show that Yuanjiang andradite has a lower specific gravity than typical andradite, which is due to the presence of epidote inclusions inside. EPMA results indicate that the samples contain a certain amount of Cr element. The crystal chemical formula of the samples calculated from the EPMA results is (Ca2.89–2.93, Mn0.01–0.02, Fe0.15–0.10)(Fe1.69–1.95, Al0.00–0.23, Cr0.00–0.23, Si0.05–0.08)(SiO4)3. UV-Vis tests show that the samples have transmission windows in both the green- and red-light regions, with Fe3+ and Cr3+ acting as the main chromogenic ions, among which Cr3+ is crucial for the occurrence of the Usambara effect. The FTIR and Raman test results are basically the same as previous research results, but some peak positions related to metal cations differ from the theoretical values, which may be caused by the presence of a certain amount of Cr3+ in the samples.

1. Introduction

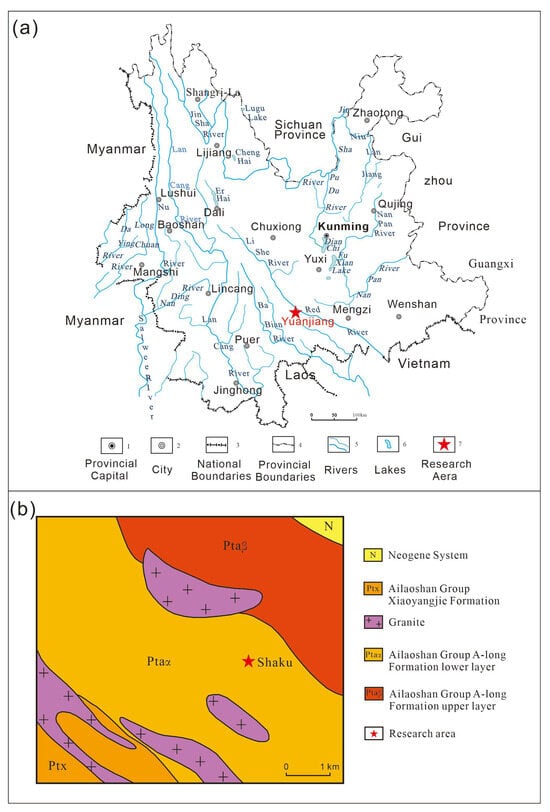

Yuanjiang County in southern Yunnan is the most famous gemstone deposit concentration area in China (Figure 1a). Since the 1960s, gem minerals such as ruby, sapphire, tourmaline, spinel, clinohumite, idocrase, zircon, and rutile have been successively discovered in this area [1,2]. This deposit concentration area is located in the Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone at the boundary between the Indochina Block and the Sichuan–Yunnan Block [3], where typical Barrovian Metamorphic Sequence Rocks are developed [4]. These conditions provide favorable temperature, pressure, and fluid conditions for the formation of various gemstone deposits.

Figure 1.

(a): Location map of the research area; (b): geological map of research area.

Recently, during the sample collection work carried out by the author’s team in Yuanjiang County, gem-quality garnet crystals were found in the epidote amphibolite on the periphery of the Yuanjiang Shaku ruby deposit (Figure 1b). Subsequent tests revealed that the garnet samples discovered belong to andradite; these garnet samples exhibited the rare Usambara effect.

The Usambara effect is a phenomenon where a gemstone exhibits color differences due to variations in thickness in different parts of the gemstone. Generally, thicker regions (usually greater than 1.5 mm) appear red, while thinner regions appear green [5,6,7]. The scientific term “Usambara effect” was first proposed by Halvosen and Jensen in 1997. Subsequently, Nassau clearly defined the Usambara effect as a color change involving a hue shift. A change in color concentration cannot be called the Usambara effect but can only be referred to as the Concentratione [5].

Up to now, the Usambara effect has been found in gemstones such as chrysoberyl [5], tourmaline [7,8,9,10], and andalusite [11]. Additionally, previous researchers have also reported Pyrope-Spessartine as displaying the Usambara effect [12,13,14]. However, there have been no previous reports on andradite regarding the Usambara effect. Therefore, the andradite displaying the Usambara effect, discovered in Yuanjiang County, may be the first reported case.

Based on the above research, for the andradite with the Usambara effect collected in Yuanjiang County, we obtain characteristics such as the specific gravity, hardness, refractive index, and fluorescence of andradite through basic gemological tests; use Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) to test the chemical composition of the samples and perform end-member calculations; and utilize ultraviolet–visible absorption spectroscopy (UV-VIS), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and Raman Spectroscopy (Raman) to investigate the spectroscopic characteristics of the samples and the correlation between sample color and composition.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sample Materials

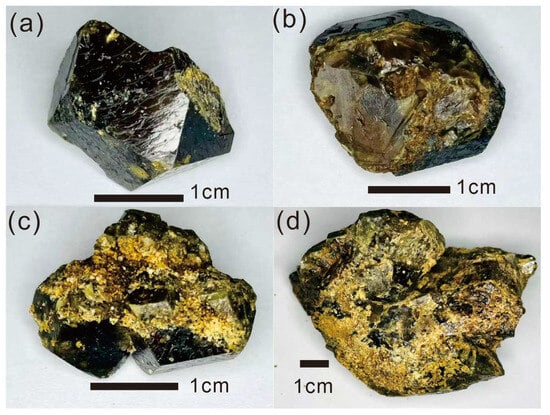

A total of 5 samples were collected in this study (Figure 2), among which two samples were obtained by cutting a single parallel intergrowth crystal into two pieces. The samples are euhedral crystals, mostly rhombic dodecahedrons, with an overall brownish-red color, and green coloration at the thin edges. These andradite crystals for research were collected from epidote amphibolite in the lower layer of A-long Formation of Ailaoshan Group in the highly weathered periphery of the ruby deposit in Shaku Village, Yuanjiang County. These andradite crystals are associated with dark green flaky and granular epidote and are rich in euhedral granular epidote inclusions.

Figure 2.

Andradite crystals of Yuanjiang. (a) single crystal of andradite; (b)single crystal of andradite; (c) parallel intergrowth crystal of andradite; (d) andradite in the epidote amphibolite.

Three samples were cut and polished into 3 faceted gemstones, YJ-B1, YJ-B2, and YJ-B3, for basic gemological tests and spectroscopic tests. Among these, two samples with fewer inclusions, YJ-B1 and YJ-B2, were used for FTIR and UV-VIS tests, and YJ-B3, with more inclusions, was used for Raman test. Two samples were sliced and polished to observe the Usambara effect and, after observation, they were made into electron probe targets YJ-B4 and YJ-B5.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Basic Gemological Testing

Basic gemological testing was conducted at the Research Center for Analysis and Measurement Kunming University of Science and Technology. Refractivity testing was conducted using the GI-RB Gemstone Digital Refractometer (BGI, Nanjing, China) with the spot measurement method. Specific gravity was determined by hydrostatic weighing, using the FA2004 electronic precision balance (Tianjin Qingda, Tianjin, China) as the measuring instrument. Fluorescence reaction testing was completed using a Convoy S2 (UV365nm) ultraviolet lamp (Convoy, Hongkong). The Mohs Hardness of the Yuanjiang andradite samples was determined using the scratch method with ZJ-209 Mohs Hardness Pens (ZJIA, Shenzhen, China).

2.2.2. Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA)

Electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) was conducted using a JXA-8230 electron probe microanalyzer (JOEL, Tokyo, Japan) at the Testing Center of Shandong Bureau, China Metallurgical Geology Bureau. The samples were firstly coated with a thin conductive carbon film prior to analysis, and we obtained a ca. 20 nm approximately uniform coating. The analysis was carried out under operating conditions of 15 kV accelerating voltage, 20 nA beam current, and a 20 μm beam diameter. Calibration was performed using SPI Minerals/Metals Standards (USA), including jadeite (for SiO2 and Na2O), rutile (TiO2), yttrium aluminum garnet (Al2O3), olivine (for FeO and MgO), rhodonite (MnO), and diopside (CaO). Data were calibrated using the ZAF correction method.

2.2.3. Ultraviolet–Visible Absorption Spectroscopy (UV-VIS)

Ultraviolet–visible absorption spectroscopy (UV-VIS) was performed at the Qingdao Institute of Measurement Technology. The ultraviolet–visible spectrum analysis was carried out using the UV5000XL Ultraviolet–Visible Spectrometer (Baoguang Co., Nanjing, China). All samples had polished planes. The testing range was 220–1000 nm; the integration time was 85 ms. The reflection method was adopted for the test, and the average number of scans was 40.

2.2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was conducted at the Qingdao Institute of Measurement Technology using infrared spectroscopy analysis, carried out using a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany). All samples had polished planes. The testing range was 400–1200 cm−1, the resolution was 4 cm−1, the scanning time was 16 s, and the reflection method was adopted for the test.

2.2.5. Raman Spectroscopy (RAMAN)

Raman spectroscopy was performed at the Qingdao Institute of Measurement Technology. Raman spectra were recorded on a setup consisting of a Thunder Optics Raman probe (Thunder Optics, Montpellier, France) and an NR Laser spectrometer (CNI, Changchun, China), using 532.1 nm laser excitation and a 50 μm slit. The spectra covered the Raman shift range of 140–1200 cm−1. The testing conditions were as follows: laser wavelength of 532.1 nm, wavenumber range of 140–4000 cm−1, data collection range of 100–1200 cm−1, resolution of 1 cm−1, 5 accumulations, and detection time of 30 s.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gemological Characteristics

It is necessary to conduct refractive index, specific gravity, fluorescence reaction, and Mohs Hardness tests on andradite samples YJ-B1 and YJ-B2, The test results are shown in Table 1. The refractive index test is completed using the spot measurement method.

Table 1.

Basic gemology test results of samples.

Fluorescence reaction test using long-wave (365 nm) and short-wave (253.7 nm) ultraviolet light.

Test results show that the refractive index of Yuanjiang andradite samples is 1.878~1.880, with no birefringence, which is consistent with the refractive index characteristics of andradite from other localities. The specific gravity is 3.69~3.66, which is lower than that of andradite reported in previous studies, which may be caused by the inclusion of a large number of low-density inclusions.

Under both long-wave (365 nm) and short-wave (253.7 nm) ultraviolet light, the samples were inert to fluorescence. This might be caused by the iron element present in the sample, which leads to fluorescence quenching. The Mohs hardness of samples is 7.5; this is the same as that of andradite from the other areas.

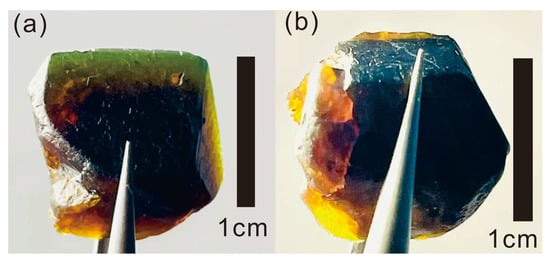

The sliced samples YJ-B4 and YJ-B5 were observed under a light source with a color temperature of 2850 k. The edge part of JY-B4 has a thickness of less than 2 mm, and the central part has a thickness of more than 2 mm, with its edge showing green colors and the center showing reddish-brown colors. When YJ-B4 and YJ-B5 were stacked to make the edge thickness greater than 2 mm, the edge color showed reddish-brown colors, and a hue change occurred (Figure 3). This phenomenon indicates that the color of the sample is related to thickness rather than being affected by the color temperature of the light source, which conforms to the definition of the Usambara effect.

Figure 3.

Usambara effect on (a) YJ-B4 and (b) YJ-B5.

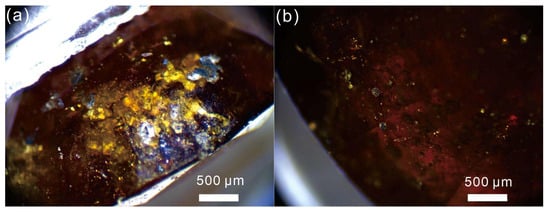

3.2. Microscopic Characteristics

Microscopic observation and photomicrography were conducted at the Faculty of Land and Resources Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology, using a LEICA S6D stereomicroscope to examine the faceted and cabochon samples of Yuanjiang andradite. Microscopic examination revealed that the YJ-B1, YJ-B2, and YJ-B3 commonly contain euhedral crystal solid inclusions. Based on the color and shape of the inclusions, it is speculated that these inclusions are epidote (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a,b) Inclusions of Yuanjiang andradite samples. Bar = 500 μm.

3.3. Electron Probe Micro-Analysis (EPMA)

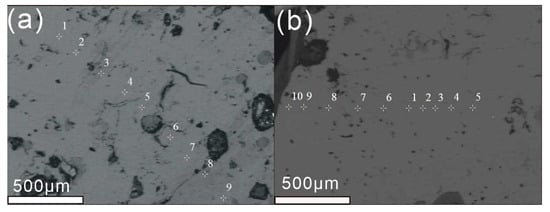

The EPMA was used to capture backscattered electron (BSE) images (Figure 5) of typical andradite grains from probe slices YJ-B4 and YJ-B5. The BSE image shows that the sample does not have any well-developed zoning in the andradite samples, and there are also some hole structures present. Additionally, small automorphic andradite mineral inclusions were identified within the andradite grains in the BSE images.

Figure 5.

BSE images with the marks of test points of YJ-B4 (a) and YJ-B5 (b). Bar = 500 μm.

Electron probe wavelength dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) analysis was performed at 10 points on sample YJ-B5, and performed at 9 points on sample YJ-B4 in two probe sections to determine the major element oxide contents of Yuanjiang andradite. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

EPMA analytical result of andradite from Yuanjiang (Wb/%).

EPMA analysis provides the weight percentages of oxides for Yuanjiang andradite samples YJ-B4 and YJ-B5, which will be used to calculate the atomic counts and crystal chemical formulas of the samples. Since EPMA analysis can only provide the total FeO content and cannot directly reflect the contents of Fe2O3 and FeO, it is necessary to calculate based on the FeO content to obtain the contents of Fe2O3 and FeO.

The values of Fe2O3 and FeO were calculated using the charge balance method [15]. The raw EPMA data were processed using the geochemical data analysis software GeoKit (version: GeoKitPro) [16]. Based on 12 oxygen atoms and 8 cations, the ionic numbers of the samples were calculated [17], and the results are presented in Table 3. The crystal chemical formula of the samples was derived from the calculated ionic numbers: A3B2(ZO3)4. The results show that the crystal chemical formula of the samples is (Ca2.89–2.93, Mn0.01–0.02, Fe0.15–0.10)(Fe1.69–1.95, Al0.00–0.23, Cr0.00–0.23, Si0.05–0.08)(SiO4)3, which is very close to the theoretical chemical formula of andradit, Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3. In addition, the sample contains a certain amount of Cr element, which can also be called demantoid.

Table 3.

Ions of andradite from Yuanjing. nB (number of ions calculated on the basis of n (O) = 12).

The end-member components of Yuanjing andradite were calculated using the geochemical data processing software GeoKit [15], with the results shown in Table 4. The calculations reveal that the analyzed samples are primarily composed of andradite, containing minor components of grossularite, spessartine, almandine, and pyrope. Trace amounts of uvarovite, schorlomite and knorringite were also detected in some measurement points.

Table 4.

End-member components of andradite from Yuanjiang.

3.4. UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy Analysis

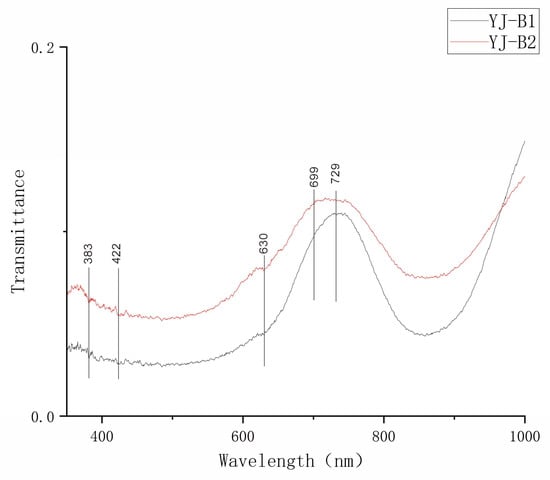

UV-Vis test results show that samples YJ-B1 and YJ-B2 have three transmission windows, namely, a weak transmission window in the green-light region at 560–580 nm, a relatively weak transmission window in the green- to yellow-light region at 585–630 nm, and a strong transmission window in the yellow- to red-light region at 633–857 nm. The transmission windows located in the green-light region and yellow- to red-light region, respectively, may be among the important factors influencing the formation of the Usambara effect.

In this UV-Vis test, the Yuanjiang andradite samples have absorption peaks at 383 nm, 422 nm, 630 nm, 699 nm, and 729 nm (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

UV-Vis spectrum of Yuanjiang andradite samples.

According to previous studies, peaks at 383 nm and 422 nm are attributed to Fe3+ occupying octahedral sites, corresponding to electronic transitions between the 6A1g → 4E14Ag energy levels [18,19,20,21,22]. Peaks at 443 nm are related to the spin-allowed electronic d-d transitions resulting from Cr3+ in the octahedral field, corresponding to 4A2g(4F) → 4T2g(4F) transitions [23,24,25]. The absorption peak at 630 nm can be attributed to the transition absorption of the 3d3 electrons of Cr3+ between the 4A2 and 2Eg energy levels [25]. The absorption peak at 699 nm is caused by the electron transition between the 4A2g(4F) and 4T2g(4F) energy levels, which results from the splitting of the 4A2g(4F) term in the 3d3 electron configuration of Cr3+ ions [25]. The absorption peak at 729 nm is caused by the electron transition between the 6A1g and 4T2g energy levels of Fe2+ ions [25].

Combined with the EPMA test data and end-member calculation results mentioned above, Fe3+ plays a dominant role in influencing the color of the samples, and Cr3+ also has a certain impact on the color of the samples.

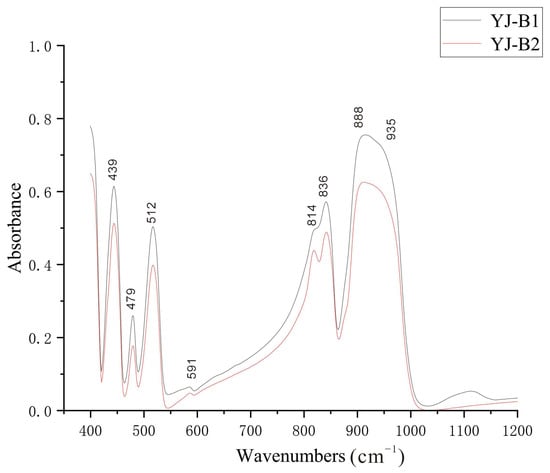

3.5. FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis

Based on A.M. Hofmeister’s research on the vibrational spectroscopy of garnet end-member minerals using DFT calculations and Luo W.’s research findings on the FTIR absorption spectra of garnet end-member minerals, andradite exhibits 8 absorption peaks in the range of 400–1200 cm−1, with the attribution table provided in Table 5a [26,27].

Table 5.

(a) Vibrational frequencies (IR absorption peaks) of andradite (cm−1). (b) Vibrational frequencies (Raman-active modes) of andradite (cm−1).

This test, performed on samples YJ-B1 and YJ-B2, collected a total of 8 FTIR absorption peaks. The FTIR absorption peaks of samples are as follows:

A: 936 ± 1 cm−1, B: 915 ± 5 cm−1, C: 839 ± 3 cm−1, D: 816 ± 2 cm−1, E: 590 ± 2 cm−1, F: 514 ± 2 cm−1, G: 478 ± 2 cm−1, H: 441 ± 2 cm−1.

The infrared absorption peaks obtained in this study are basically consistent with previous studies. However, the peak position of peak B differs significantly from the theoretical value of the B peak position of andradite. After comparison with garnet group minerals of other end-members, it is found that its peak position is consistent with the theoretical value of the B peak position of uvarovite. Therefore, it is considered that this phenomenon may be related to the sample with a certain uvarovite end-member component.

From Figure 7, we can observe that the peak at 888 cm−1 and the peak at 935 cm−1 of the two samples undergo significant peak merging. Therefore, the peak at 814 cm−1 and the peak at 835 cm−1 also show a certain degree of peak merging.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectrum of Yuanjiang andradite samples.

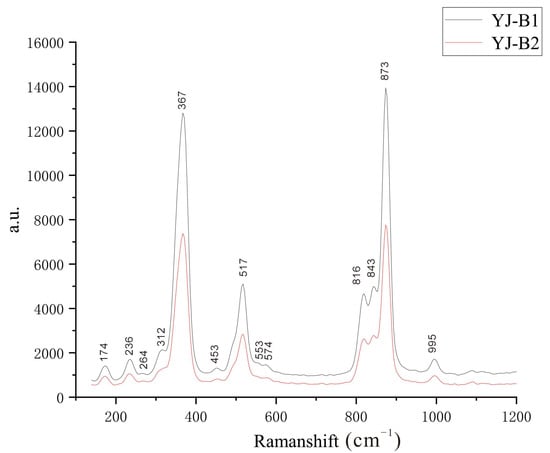

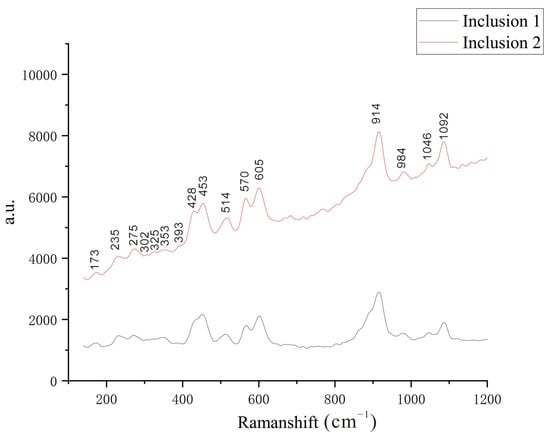

3.6. Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

A total of 13 Raman-active modes were detected (Figure 8). This result exhibits some peak position deficiencies compared to the number of Raman-active modes reported in previous studies or measurements, with the missing peaks attributed to overlapping signals and low-intensity peaks. The observed Raman shifts are as follows: 995 cm−1, 873 cm−1, 843 cm−1, 816 cm−1, 574 cm−1, 553 cm−1, 517 cm−1, 453 cm−1, 367 cm−1, 312 cm−1, 264 cm−1, 236 cm−1, and 174 cm−1 (Figure 8). Peak position assignments for the obtained Raman-active modes were performed based on previous studies, and the results are presented in Table 5b [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Several Raman-active modes had undergone a blue shift relative to the theoretical positions. This phenomenon is due to the fact that the measured sample is not entirely composed of the grossularite end-member; in particular, the presence of the andradite end-member component in the sample causes a blue shift in some peak positions [32].

Figure 8.

RAMAN spectrum of Yuanjiang andradite samples.

In addition, this time, Raman spectroscopy was also used to test a single green inclusion that was exposed to the surface of sample YJ-B1. A total of 16 Raman-active modes were detected (Figure 9). These Raman-active modes are consistent with the active modes reported for the (001) plane of epidote in previous studies [34]. Therefore, it is believed that the green mineral inclusion should be epidote [34].

Figure 9.

RAMAN spectrum of inclusions in Yuanjiang andradite samples.

3.7. Discussion

According to the previous research, the Usambara effect is strongly correlated with the alexandrite effect, and both effects are related to Cr3+. The spectral positions of the spin-allowed absorption bands of Cr3+ have two transmission windows, green and red, and the transmittance ratio of these two transmission windows depends on the difference in sample thickness [35]. According to EPMA tests, the samples in this study contain a certain amount of Cr3+, and UV-VIS test results also found two transmission windows related to Cr3+ located in the green-light region and red-light region, respectively. Although the two transmission windows in the green and red regions exist simultaneously, due to the difference in human eye perception of different colored lights [10,36], we can observe that when the sample thickness is thin, the sample appears green, while when the sample thickness is thick, the sample appears reddish-brown.

In addition, the number of 8 peaks obtained in our FTIR test is consistent with that recorded in previous studies [27], but the position of the H peak related to trivalent cations has a red shift of 11 cm−1. For andradite, the trivalent cation position is generally occupied by Fe3+. However, according to EPMA data and end-member component calculation results, the samples from Yuanjing contain a certain amount of Cr3+, which may be the reason for the red shift in the H peak position.

In conclusion, although Yuanjing andradite contains only a small amount of Cr3+, these Cr3+ have a significant impact on the gemological and spectroscopic characteristics of the samples.

Cr3+, as a crucial component influencing the color of andradite, is inherited from the protolith. These chromium ions enter the mineral lattice by substituting for ferric iron ions (Fe3+) within the andradite crystal structure. Under the high-temperature and -pressure conditions of regional metamorphism, minerals in the protolith become unstable and undergo recrystallization, forming new stable mineral assemblages. During this process, chromium already present in the protolith is redistributed [1]. As andradite forms as a metamorphic mineral, it directly scavenges Fe3+ and Cr3+ from the local chemical system in which it grows.

Therefore, the possible protoliths are iron-rich sedimentary rocks (such as ferruginous jasper, iron formations) [3,4], intermingled with chromium-enriched clays or detritus derived from the weathering products of ancient ultrabasic rocks. In this environment, chromium is inherent to the protolith and is utilized in situ during metamorphic recrystallization, entering the lattice of the newly formed andradite.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The hardness, refractive index, fluorescence, and other features of Yuanjing andradite are in line with those of other andradites. However, its specific gravity is lower compared than those from other origins. This is due to the presence of some epidote inclusions within Yuanjing andradite that have a lower density than andradite.

- (2)

- Yuanjing andradite samples exhibit a reddish-brown color when their thickness exceeds 2 mm and a green color when their thickness is less than 2 mm. This color-changing effect is solely related to the sample thickness and is a typical Usambara effect.

- (3)

- EPMA test results and end-member component calculations indicate that the crystal chemical formula of Yuanjing andradite is (Ca2.89–2.93, Mn0.01–0.02, Fe0.15–0.10)(Fe1.69–1.95, Al0.00–0.23, Cr0.00–0.23, Si0.05–0.08)(SiO4)3. The end-member components of the samples are predominantly andradite, with small amounts of grossularite, spessartine, almandine, and pyrope end-member components, as well as trace amounts of uvarovite, schorlomite and knorringite end-member components.

- (4)

- UV-Vis tests reveal that the color of Yuanjing andradite is mainly associated with Fe3+ and Cr3+. There are three transmission windows in the visible light band, all located in the green-light and red-light regions. Among them, two relatively major transmission windows are related to Cr3+.

- (5)

- Both FTIR and RAMAN test results demonstrate that the samples possess the characteristics of typical andradite. However, there are some differences between certain peak positions and theoretical values. In combination with EPMA test results and end-member component calculation results, we consider that this is because the end-member components other than andradite contained in the samples influenced the peak positions of FTIR and RAMAN.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-R.-X.C. and Y.-M.T.; methodology, L.-R.-X.C.; investigation, Y.-M.T., L.-R.-X.C., S.-T.Z., Z.Q., H.-T.S., X.-Q.Y. and Y.-K.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Q., H.-T.S. and X.-Q.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.-R.-X.C. and Y.-M.T.; writing—review and editing, L.-R.-X.C. and Y.-M.T.; visualization, Y.-M.T.; supervision, S.-T.Z. and Y.-M.T.; project administration, S.-T.Z. and Y.-M.T.; funding acquisition, Y.-M.T. and S.-T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Fundation of China (grant No. 42302030); Talent training project of KUST (Kunming University of Science and Technology), grant No. KKZ3202421134; Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program (this funding do not have grant No.); the New round of mineral exploration operation of Yunnan (grant No. Y202407).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to gemstone cutters Yong Yin and Wenzhong Zhu for their assistance in cutting the samples. And we would like to express our gratitude to Si-qi Yang from the Faculty of Materials Science and Engineering at KUST for his assistance to us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, C.; Hu, C. Mineralization Characteristics of Gems in Ailaoshan Structural Belt, Yunnan Province. J. Gemmol. 2003, 3, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ni, P.; Zhou, J.; Shui, T.; Pan, J.; Fan, M.; Yang, Y. Progress in the study of a marble-hosted ruby deposit from Yuanjiang, Yunnan Province, China. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Academic Conference on Jewelry and Accessories, Qingdao, China, 1–5 October 2023; pp. 95–98+103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Tong, Y.; Pei, J.; Yang, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z. Tectonic evolution of the Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone and its relationship with the growth of the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Gondwana Res. 2024, 129, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Liu, F.; Palin, R.; Wang, F.; Sun, Z. Thermal and Physical Properties of Barrovian Metamorphic Sequence Rocks in the Ailao Shan-Red River Shear Zone, and Implications for Crustal Channel Flow. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2023JB027253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidinger, W. Ueber den pleochroismus des chrysoberylls. Ann. Der Phys. 1849, 153, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, A.; Jensen, B. A new colour-change effect. J. Gemmol. 1997, 25, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, A. The Usambara effect and its interaction with other colour change phenomena. J. Gemmol. 2006, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassau, K. The Physies and Chemistry of Color: The Fifteencauses of Color, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Simonet, C. Geology of the yellow mine (Taita-Taveta district, Kenya)and other yellow tourmaline deposits in East Africa. J. Gemmol. 2000, 27, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Lv, F.; Jia, C.; Shen, X. Chemical Composition and Spectroscopie Characteristie of Tourmaline with Usambara Effect. J. Gems Gemmol. 2024, 26, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeau, B.; Chamard-Bois, S.; Fritsch, E.; Notari, F.; Chauviré, B. Reverse dichromatism in gem andalusite related to total pleochroism ofthe Fe2+-Ti+ IVCT. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 204, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, D.V.; Stockton, C.M. Pyrope-Spessartine Garnets with Unusual Color Behavior; Gems & Gemology: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Krzemnicki, M.S. Exceptional colour change garnets showingthe Usambara effect. Facette 2014, 12, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Palke, A.C.; Renfro, N. Vanadium-and chromiumbearing pink pyrope garnet: Characterization and quantitative colorimetric analysis. Gems Gemol. 2015, 51, 348–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.R. Calculation of Fe3+ and Fe2+ from electron microprobe analysis. Acta Mineral. Sin. 1983, 1, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.F. GeoKit: A geochemical toolkit developed with VBA. Geochimica 2004, 5, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.J.B. Electron Microprobe Analysis and Scanning Electron Microscopy in Geology; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, C.A.; Stahl, A.; Rossman, G.R. Raspberry-red grossular from Sierra de Cruces Range, Coahuila, Mexico. Eur. J. Mineral. 1999, 11, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.G. Optical absorption spectra of Fe3+ in octahedral and tetrahedral sites in natural garnets. Can. Mineral. 1972, 11, 826–839. Available online: https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/mac/canmin/article-abstract/11/4/826/10874/Optical-absorption-spectra-of-Fe-super-3-in?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Amthauer, G. Kristallchemie und Farbe Chromhaltiger Granate: Neues Jahrbuch Fur Minerulogie Abhandlungen; Gems & Gemology: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 1976; Volume 126, pp. 158–186. [Google Scholar]

- Amthauer, G.; Rossman, G.R. The hydrous component in andradite garnet. Am. Miner. 1998, 83, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.L. A member of the ugrandite garnet series found in Western Australia. Aust. Gemmol. 1973, 11, 19–20. Available online: https://eurekamag.com/research/091/118/091118004.php (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Vigier, M.; Fritsch, E. Pink axinite from Merelani, Tanzania:Origin of colour and luminescence. J. Gemmol. 2020, 37, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, I.; Lauria, A.; Spinolo, G. Optical absorption spectra of Fe2+ and Fe3+ in aqueous solutions and hydrated crystals. PSSB 2007, 12, 4669–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Y. The Gemology Characteristics of Green Garnet. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, A.M.; Chopelas, A. Vibrational spectroscopy of end-member silicate garnets. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1991, 17, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L. Mineral Infrared Spectroscopy; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kolesov, B.A.; Geiger, C.A. Raman spectra of silicate garnets. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1998, 25, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, V.; Winkler, B.; White, J.A.; Pickard, C.J.; Payne, M.C.; Akhmatskaya, E.V.; Nobes, R.H. Electronic Structure, Properties, and Phase Stabilityof lnorganic Crystals: A Pseudopotential Plane-Wave Study. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015, 77, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1967, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, T.; Birrer, J.; Libowitzky, E.; Beran, A. Crystal chemistry of Ti-bearing andradites. Eur. J. Miner. 1998, 10, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C. Raman Scattering of Grossular-Andradite Solid Solution. Chin. J. High Press. Phys. 2020, 34, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.Y. Compositional Characteristics and Color Quality Evaluation of Iron-Magnesium-Aluminum Garnets. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.J. The Study on Gemological and Mineralogical Characteristics of Epidote from Pakistan. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, M.N.; Naumenko, I.V. Usambara effect in tourmaline: Optical spectroscopy and colourimetric studies. Miner. Mag. 2016, 80, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Ye, D. Role of Cr and V in colour change effect of gemstones. J. Gems Gemmol. 2003, 5, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).