Abstract

In this study, a duplex lightweight steel with the compositions of Fe-30Mn-9Al-1C-1V-5Ni (wt.%) was designed, and its microstructure and mechanical properties were analyzed after simple rolling and heat treatment. The microstructure of duplex lightweight steel consists of austenite and B2 phases, with the dual-nanoprecipitation of L′12 type long-range ordered domains and VC carbides within the austenite. The steel exhibits an ultra-high strength-ductility combination, with a yield strength of 1316 ± 16 MPa, a tensile strength of 1458 ± 11 MPa, and a total elongation of 11.7 ± 1.2%. Its high strength is primarily attributed to hetero-deformation induced (HDI) strengthening, solid solution strengthening, and precipitation strengthening. Meanwhile, the substantial dislocation accumulation in both austenite and B2 phases, coupled with the HDI hardening from intense heterogeneous deformation near grain/phase boundaries, collectively confers the steel with excellent ductility.

1. Introduction

High-Mn Fe–Mn–Al–C austenitic lightweight steels have garnered significant attention in automotive, aerospace, and energy industries due to their exceptional combination of low density and high strength [,,]. The addition of Al into the lightweight steels not only reduces specific weight but also induces the precipitation of fine L′12–structured κ′–carbides ((Fe,Mn)3AlCₓ) within austenite, thereby boosting yield strength (YS) via precipitation hardening []. However, these κ′–carbides are readily sheared by moving dislocations, which limits work–hardening capacity and reduces the uniform elongation. Furthermore, with an increase in aging time, brittle phases such as coarse κ-carbides and β-Mn are generated at grain boundaries, which can lead to a severe degradation in the ductility of the austenitic lightweight steel [,,].

To overcome the strength–ductility trade-off, recent studies have explored the substitution of κ′-carbides with long-range ordered (LRO) domain precipitation, achieving simultaneous improvements in strength and ductility of austenitic lightweight steels [,]. Similar results have also been reported in face-centered cubic high-entropy alloys [,,,]. However, the enhancement in YS of these alloys is limited (about 100 MPa) when relying solely on LRO domain strengthening. On the other hand, it is well established that precipitation hardening from nanoscale carbide precipitates, particularly VC, can significantly improve the YS and work-hardening capacity of steels. For instance, Xie et al. [] investigated the effect of adding 0.5 wt.% V to Fe-25Mn-10Al-1.1C (wt.%) austenitic lightweight steel and found that the addition of V increased the YS by approximately 260 MPa through VC precipitation strengthening and grain refinement. Similar strengthening effects were also observed in austenitic twinning-induced plasticity steels, where the addition of V enhanced the YS by 61–200 MPa [,]. Furthermore, the precipitation of VC consumes carbon within the austenite matrix, thereby lowering its carbon content. This reduction not only suppresses the coarsening of κ′-carbides but may also promote the formation of LRO domains.

Introducing heterogeneous structures into metallic materials has proven to be an effective strategy for achieving an optimal balance between strength and ductility, owing to the generation of heterogeneous deformation-induced (HDI) strengthening []. The heterogeneous structures, including multi-layered, bimodal, dual-phase/multi-phase, and gradient structures, induce strain incompatibility among different regions during deformation. Consequently, pronounced strain gradients are developed, which promote the accumulation of geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs) and lead to a significant HDI strengthening effect. For example, recent studies indicate that in Fe-21Mn-6Al-4Si-1C (wt.%) austenite-ferrite duplex lightweight steel, the formation of a dual-phase structure successfully achieved an HDI strengthening effect ranging from 180 MPa to 392 MPa []. Ni alloying can promote the formation of the B2 (NiAl) phase in duplex lightweight steels by transforming ferrite into B2 []. Because the B2 phase possesses a higher hardness than ferrite, a stronger HDI strengthening effect can be achieved []. However, the significant hardness mismatch between the austenite and B2 phases often increases the risk of cracking. Therefore, regulating the precipitation behavior within the austenite phase to balance the hardness between the two phases is crucial for achieving an excellent strength–ductility synergy in austenite-B2 duplex lightweight steels.

In this study, an Fe-30Mn-9Al-1C-1V-5Ni (wt.%) austenite–B2 duplex lightweight steel was designed, and its microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior were systematically investigated. By integrating the LRO- and VC-strengthened austenite with the B2 phase to form a heterogeneous dual-phase structure, the alloy simultaneously achieved ultra-high strength and excellent ductility. The steel is produced by a simple processing route involving cold rolling and heat treatment. The microstructural evolution and mechanical response of the duplex lightweight steel were thoroughly characterized. Based on the experimental results and available theoretical models, the mechanisms responsible for the outstanding mechanical properties of this steel are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

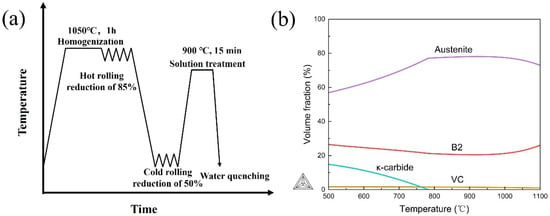

A 10 kg ingot of lightweight steel, with a nominal composition of Fe-30Mn-9Al-1C-1V-5Ni (wt.%), was prepared via induction melting under a high-purity argon atmosphere. Fe, Mn, Al, Ni, and V were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), while C was determined by the combustion-infrared absorption method. The measured compositions of the ingot are presented in Table 1. Plates with dimensions of 90 mm in length, 40 mm in width, and 20 mm in thickness were sectioned from the ingot. These plates were first homogenized at 1050 °C for 1 h and then hot-rolled to a thickness of 3 mm. Following hot rolling, the plates were immediately water-quenched to room temperature. The hot-rolled sheets were subsequently cold-rolled to a final thickness of approximately 1.5 mm. The single-pass reduction rate during cold rolling was maintained at or below 5%, corresponding to a total thickness reduction of 50%. Then, the cold-rolled sheet was solution-treated at 900 °C for 15 min, followed by water quenching, as shown in Figure 1a. Figure 1b displays the equilibrium phase diagram of the duplex lightweight steel calculated using Thermo-Calc 2021b software, which indicates the coexistence of austenite and B2 phases at 900 °C, along with the precipitation of VC.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions (wt.%) of Fe-30Mn-9Al-1C-1V-5Ni steel ingot.

Figure 1.

(a) Processing route and (b) equilibrium phase diagram for the duplex lightweight steel.

Flat dog-bone-shaped tensile specimens with a gauge dimension of 20 × 5 × 1.5 mm3 were cut from the solution-treated steel plate by electrical discharge machining (EDM). Uniaxial tensile tests were conducted at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 using a Meters Industrial CMT5105 universal testing machine(Meters Industrial, Minneapolis, America), where a Meters Industrial LX500 laser extensometer(Meters Industrial, Minneapolis, America) was used to monitor the tensile strain. Each specimen was tested three times to ensure the reproducibility of the tensile data. In addition, cyclic loading-unloading-reloading (LUR) tensile tests were performed on the same apparatus at a loading and unloading rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1. To reveal microstructural evolution during the deformation process, in situ tensile tests were performed using a TESCAN scanning electron microscope (SEM, TESCAN, , Brno, Czech Republic), equipped with an independent tensile loading system and an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) detector(Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK). The tensile rate was maintained at 2 μm/s, and tests were paused at tensile strains of 0%, 1%, 3%, and 6% to acquire EBSD data of the same surface region. Dog-bone-shaped specimens with a gauge dimension of 8 × 2 × 1 mm3 were prepared via EDM for these tests.

Microstructural characterization of the specimens was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), SEM, EBSD, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The XRD, SEM, and EBSD samples were carefully mechanically polished, followed by electro-polishing using an electrolyte of 10% perchloric acid in alcohol and a voltage of 40 V at about 10 °C. The XRD analysis was conducted with a Bruker D8(Bruker Corporation, Walzbachtal, Germany) Focus diffractometer using Cu-Kα radiation with a scanning range from 20° to 100°and a scanning rate of 2° min−1. The EBSD observations were carried out using a TESCAN MIRA4 scanning electron microscope(TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) equipped with a C-Nano+ EBSD detector. The following settings were used during EBSD data acquisition: a sample tilt angle of 70°, an acceleration voltage of 20 kV, a working distance of 15 mm, and step sizes of 0.1 μm. Following the EBSD data, MATLAB 2018b code was written to calculate GND density by the method in Refs [,]. For TEM analysis, ~0.5 mm thick flat specimens prepared using EDM were first ground into foils with a thickness of <100 µm and then further thinned until perforation by double-jet electrochemical polishing at 20 V and −30 °C with an electrolyte consisting of 90 vol.% methanol and 10 vol.% perchloric acid. TEM observation was carried out in Thermofisher Talos F200X instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, America) operated at 200 kV. The local nanoscale chemical compositions were measured through energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK) in the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mode.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Microstructures

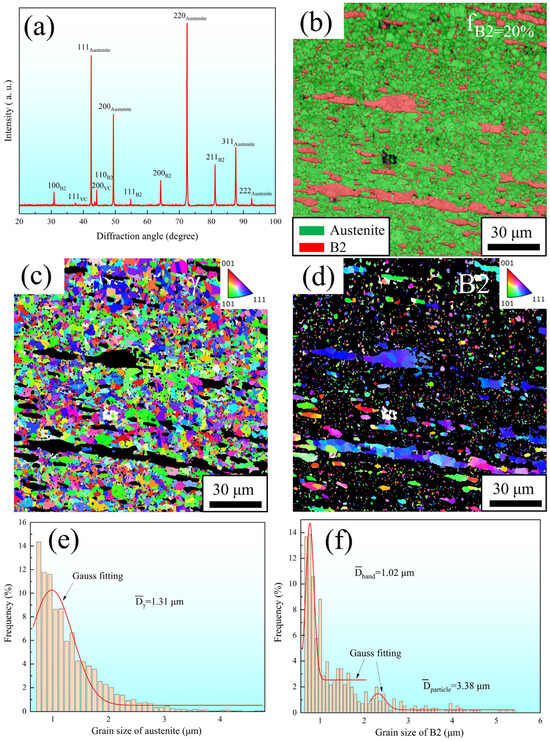

Figure 2a presents the XRD pattern of the lightweight steel, in which diffraction peaks corresponding to the austenite, B2 phases, and VC precipitation are clearly identified, consistent with the prediction of the equilibrium phase diagram in Figure 1b. The volume fractions of these phases were quantified using the XRD direct comparison method based on the integrated intensities of multiple diffraction peaks [], revealing a B2 phase fraction (VB2) of 20%. Figure 2b–f shows the EBSD characterization of the initial microstructures. In the EBSD phase map (Figure 2b), a duplex microstructure comprising austenite (green) and B2 (red) is observed. The inverse pole figure (IPF) maps (Figure 2c,d) reveal that the austenite exhibits an equiaxed morphology, whereas the B2 phase appears in two distinct forms, including long strip–like large grains and fine particles decorating austenite grain boundaries. The grain-size frequency distributions for the two phases are shown in Figure 2e,f, indicating an average grain size of 1.31 μm for austenite and a bimodal size distribution for B2, with mean grain sizes of 1.02 μm and 3.38 μm. Notably, the phase fractions obtained from the equilibrium phase diagram, XRD, and EBSD analyses are consistent.

Figure 2.

XRD and EBSD analyses of microstructures in the duplex lightweight steel. (a) XRD pattern. (b) EBSD phase map and (c,d) IPF maps. (e,f) Grain-size frequency distributions of austenite and B2.

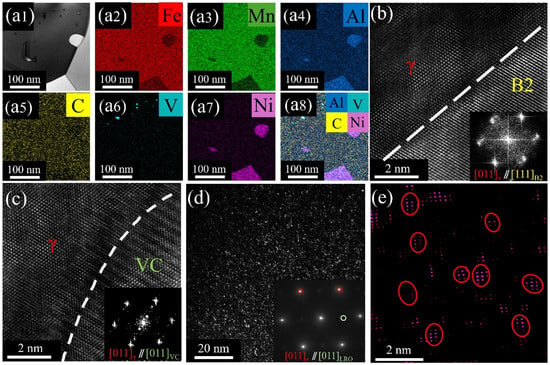

Figure 3 presents the results of (S)TEM analyses of lightweight steel. The STEM-EDS maps of Fe, Mn, Al, C, V, and Ni are presented in Figure 3(a1–a8). It is evident that Ni and Al are enriched inside the B2 phase, and V and C are enriched inside the VC precipitates. The statistics of VC precipitation on several bright-field (BF) TEM images showed that the average size of VC was 19.9 ± 6.2 nm with a volume fraction of 0.26%. High-resolution TEM images in Figure 3b,c, along with their corresponding fast Fourier transformation (FFT) images, show that the B2 phase has a semi-coherent relationship with the austenite, while the VC phase forms a coherent relationship with the austenite matrix. The inset of Figure 3d displays the selected area diffraction pattern (SADP) taken along the [011]γ zone axis inside the austenite grain. It is illustrated that, in addition to the primary reflections from austenite, the additional superlattice reflections are visible. These particular superlattice reflections have been previously verified to originate from the nanoscale L’12 type LRO domains []. The dark-field (DF) TEM image taken from the superlattice reflections is shown in Figure 3d. It can be seen that the L’12 ordered domains in the austenite grain appear as homogeneously distributed nanoscale particles. The inverse FFT image (Figure 3e) further reveals that the L’12 ordered domains exist as LRO domains with irregular shapes rather than cuboid-shaped κ′–carbides []. Statistical results reveal an average LRO domain size of 1.0 ± 0.3 nm and a volume fraction of 11.10%.

Figure 3.

(S)TEM images of the initial microstructures of duplex lightweight steel. (a1–a8) STEM-EDS maps of Fe, Mn, Al, C, V, and Ni. (b) High-resolution TEM image of the interface between the B2 and austenite phases. (c) High-resolution TEM image of an individual VC precipitate. (d) Dark-field TEM image taken from the L′12 superlattice reflection. (e) Inverse FFT image with the L′12 type ordered nanodomains highlighted.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

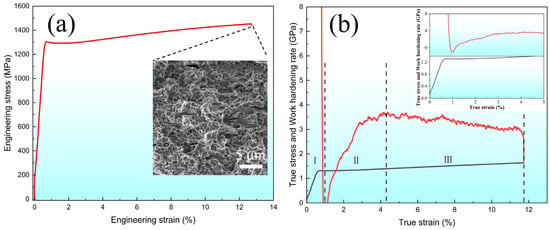

Figure 4a shows the typical tensile engineering stress–strain curve of the duplex lightweight steel. The steel exhibits a combination of ultra-high strength and excellent ductility, where the YS is 1316 ± 16 MPa, the ultimate tensile strength is 1458 ± 11 MPa, and uniform elongation is 11.7 ± 1.2%. The SEM image of the inset in Figure 4a shows that the fracture surface is characterized by dimples, indicating that the steel fractures in a ductile mode. Figure 4b demonstrates the true stress–strain curve and the corresponding work-hardening rate curve of the duplex lightweight steel. Specifically, three work-hardening stages can be observed. In stage I (0–1%), the work-hardening rate decreases sharply until it is below zero (shown in the inset of Figure 4b). The stage II (1–4.3%) is characterized by the rapid increase in the work-hardening rate. In stage III, exceeding 4.3% true strain, the work-hardening rate slowly decreases but remains at a high level (2.7 to 3.7 GPa), which is responsible for the excellent tensile strength and ductility.

Figure 4.

Tensile properties of the duplex lightweight steel. (a) Engineering stress–strain curve. (b) True stress–strain curve and corresponding work-hardening rate curve.

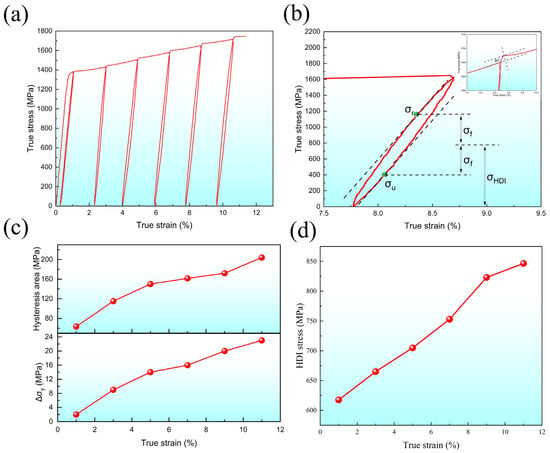

To investigate the origin of the superior mechanical properties of the duplex lightweight steel, LUR tensile tests (Figure 5) were conducted to evaluate the evolution of HDI stress. The steel sample was repeatedly loaded and unloaded at engineering strain levels of 1%, 3%, 5%, 7%, 9%, and 11% (corresponding true strains of 1.0%, 2.9%, 4.9%, 6.8%, 8.6%, and 10.4%), as exhibited in the LUR tensile testing curve (Figure 5a). Figure 5b shows a typical LUR loop at 8.6% true strain, where the unloaded yield stress (σu) and reloaded yield stress (σr) can be determined []. It can be observed that two typical features are yield drop (△σy) and hysteresis loops (Figure 5b) from the LUR tensile curve. The results show that the hysteresis area increases with increasing strain, effectively reflecting the Bauschinger effect and HDI strengthening []. The Δσy gradually increases with strain accumulation, which is due to the rapid relaxation of stress and strain at the interface between austenite and B2 [,]. As schematically depicted in Figure 5b, the HDI stress can be calculated using the equation σHDI = (σu + σr)/2, as proposed by Yang et al. []. As illustrated in Figure 5d, the HDI stress value increases progressively with increasing strain. This is primarily attributed to the deformation incompatibility between different grains and phases, which induces the accumulation of GNDs at heterogeneous interfaces, generating long-range back stresses and forward stresses in the soft and hard regions, respectively. Finally, the concurrent development of back and forward stresses enhances the resistance to plastic deformation, resulting in HDI strengthening and work-hardening [].

Figure 5.

Bauschinger effect and HDI strengthening of the duplex lightweight steel. (a) True stress–strain curve with loading and unloading. (b) Local amplification of the hysteresis loop defining σu, σr, σb, and Δσy. (c) Variation in hysteresis area and Δσy as a function of true strain. (d) Variation in HDI stress as a function of true strain.

3.3. Evolution of Microstructures During Deformation

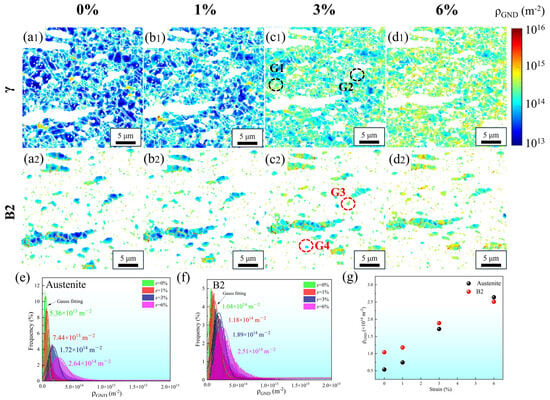

To elucidate the inherent deformation mechanisms, in situ EBSD analyses and postmortem TEM were performed to characterize the microstructural evolution of the steel during deformation. The differences in the microstructural evolution of the steel sample subjected to tensile deformation were analyzed using GND densities obtained from EBSD orientation data to assess the heterogeneous strain distributions []. Figure 6(a1–d1) shows that as the strain increases from 0% to 6%, the GND densities in the austenite and B2 phases increase monotonically from 5.36 × 1013 m−2 and 1.04 × 1014 m−2 at 0% strain to 2.64 × 1014 m−2 and 2.51 × 1014 m−2 at 6% strain, respectively. This indicates that the austenite and B2 phases undergo co-deformation, consistent with recent findings []. In the initial state (0% strain), both phases contain residual dislocations, which mainly originate from the relatively low annealing temperature (900 °C) used for the duplex lightweight steel, leading to incomplete annihilation of dislocations at grain and phase boundaries (Figure 6(a1,a2)). Because the average grain size of the B2 phase is smaller than that of the austenite, the initial GND density of B2 is higher (Figure 6e,f). With increasing deformation, the dislocation density in austenite increases more rapidly than in B2 and surpasses that of B2 at 6% strain, due to the higher deformability of austenite that facilitates dislocation accumulation both within austenite grains and along their grain boundaries (Figure 6g). The accumulation of GNDs in the B2 phase suggests that the B2 phase undergoes deformation, allowing dislocations to be stored internally. Notably, even among austenite (G1, G2) and B2 (G3, G4) grains with comparable grain sizes, differences in GND densities are still evident, as shown in Figure 6(c1,c2). This indicates that factors beyond grain size and crystal structure collectively govern the deformation behavior of individual grains.

Figure 6.

The GND distributions of the duplex lightweight steel. (a1,b1,c1,d1) GND images of austenitic phase for strains of 0%, 1%, 3%, and 6%. (a2,b2,c2,d2) GND images of B2 phase for strains of 0%, 1%, 3%, and 6%. (e–g) GND value distribution maps of austenite and B2 phases under different strains.

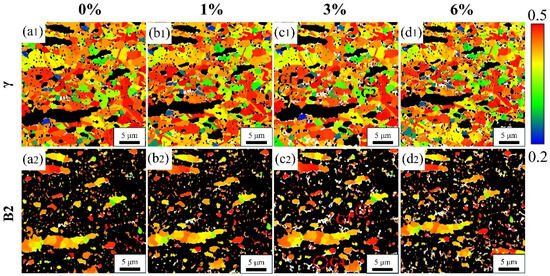

Figure 7 presents the Schmid factor maps at various strain levels (0%, 1%, 3%, and 6%), corresponding to the GND distributions. As shown in Figure 6(c1,c2) and Figure 7(c1,c2), the difference in GND density between the austenite grains (G1, G2) and the B2 grains (G3, G4) is attributed to their distinct Schmid factors. This indicates that the Schmid factor is also an important parameter influencing the deformation behavior of individual grains.

Figure 7.

The evolution of Schmid factors for austenite and B2 grains with an increase in strain (0%, 1%, 3% and 6%) in duplex lightweight steel. (a1,b1,c1,d1) austenite phase. (a2,b2,c2,d2) B2 phase.

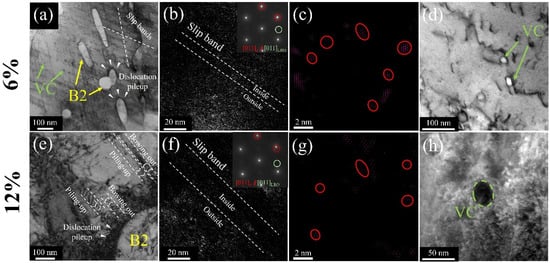

In order to further investigate the deformation mechanism of the duplex lightweight steel and the interaction between dislocations and precipitates, the samples at 6% and fractured strains were analyzed by TEM, as shown in Figure 8. The BF image of 6% strain, Figure 8a, shows that there are many dislocations inside both austenite and B2 phases, and dislocations in austenite exist in the form of nonplanar slip bands. In addition, some dislocation pile-ups can also be observed around the B2 phase in Figure 8a. Figure 8b shows a DF image of the austenite, in which the LRO domains within the slip bands are clearly weakened, and their volume fraction is reduced. The SADP shown in the inset of Figure 8b further reveals that, compared with the initial structure, the intensity of the superlattice reflections is significantly attenuated (Figure 3d). These results indicate that during the deformation of the dual-phase lightweight steel, dislocations shear through the LRO domains in austenite, leading to partial destruction of the LRO domains. In the inverse FFT shown in Figure 8c, the volume fraction of the LRO domains is decreased compared with the initial microstructure (Figure 3e), further confirming that the LRO domains have been sheared by dislocations during deformation. Figure 8d illustrates the interaction between VC precipitates and dislocations, where the VC particles impede dislocation motion and lead to the accumulation of dislocations around them. As the strain increases to 12%, Figure 8e, the dislocation density in both the austenite and B2 phases increases significantly. The interface between austenite and B2 not only impedes planar dislocation slip but also reflects the incoming dislocations, leading to the formation of new planar dislocation arrays in the austenitic matrix near the phase boundaries (Figure 8e). Figure 8f,g shows that with further straining, the volume fraction of LRO domains continues to decrease, confirming that more LRO domains within the slip bands are cut by dislocations. Figure 8h further reveals that, compared with the 6% strain, the hindering effect of VC particles on dislocation motion becomes more pronounced.

Figure 8.

TEM analyses of the deformation-induced microstructures at engineering strains: (a–d) 6% and (e–h) 12% (close to final failure).

4. Discussion

4.1. Multiple Strengthening Mechanisms

The ultra-high YS of duplex lightweight steel is attributed to a combination of multiple strengthening mechanisms, which are governed by interactions of dislocations and various obstacles in the austenite and B2 phases, as well as HDI strengthening (σHDI) due to pile-ups of GNDs near austenite/B2 boundaries. Thus, the contribution of different strengthening mechanisms to the yield stress (σYS) can be calculated from the following equation [,]:

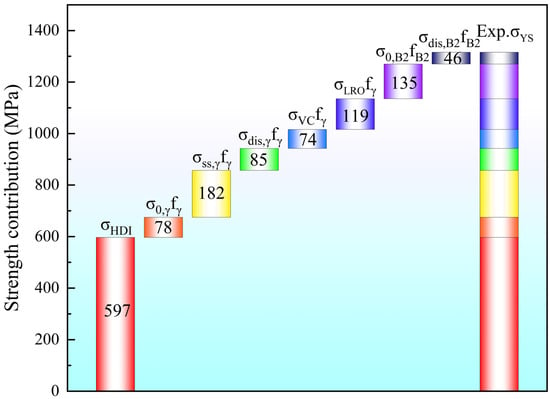

where σHDI corresponds to HDI strengthening on the yielding. σ0,γ, σss,γ, σVC,γ, σorder,γ, and σdis,γ correspond to the contributions to YS from the intrinsic lattice friction stress, solid solution strengthening, VC precipitation strengthening, chemical ordering-induced strengthening, and dislocation forest strengthening in austenite, respectively. Among these, σ0,γ is 97 MPa []. σ0,B2 and σdis,B2 correspond to the contributions to YS from the intrinsic lattice friction stress and dislocation forest strengthening in B2. The σ0 of the austenite and B2 phase are 97 MPa and 676 MPa, respectively []. σss,γ can be calculated by the following equation [,,,,]:

where XC, XMn, XAl, XNi and XV are the mass fractions of the elements C, Mn, Al, Ni, and V. The calculated σss,γ is 228 MPa. According to the Taylor strengthening model [], σdis is expressed as

where the Taylor factors M for γ-austenite and B2 phase are 3.06 [] and 2.75 [], respectively. The empirical constants α for γ-austenite and B2 phase are 0.26 and 0.4, respectively. The shear modulus G for γ-austenite and B2 phase is 70 and 82 GPa [,], respectively. The magnitudes of the Burgers vectors b for γ-austenite and B2 phase are 0.260 and 0.248 nm, respectively. Based on the average GND densities obtained from EBSD data (Figure 7), the calculated values of σdis for austenite and B2 are 106 and 227 MPa, respectively. The strengthening effect of VC can be described by the Orowan mechanism, as expressed by the following equation []:

where fVC is the fraction of VC precipitates, and DVC is the diameter of the VC. The strengthening contribution of VC precipitates is calculated to be 92 MPa.

In this study, the hardness difference in both austenite and B2 contributes to the strain incompatibility to trigger the strain gradient, thus leading to a pronounced HDI strengthening effect. σHDI can be obtained by extrapolating the HDI stress–strain curve (Figure 5d) [], and the value of σHDI is 597 MPa. Based on the above equations, σLRO can be calculated by the difference between the YS and the other strengthening contributions, which is estimated to be 119 MPa.

Figure 9 summarizes the contributions of different strengthening mechanisms to the overall YS of dual-phase lightweight steel. This indicates that the primary strengthening mechanisms in dual-phase lightweight steel are HDI stress, solution strengthening, and precipitation strengthening from nanoscale LRO and VC particles.

Figure 9.

The calculated YS of the duplex lightweight steel.

4.2. Strain Hardening Mechanisms Responsible for Tensile Ductility

As displayed in Figure 4b, the steel sample demonstrates three discernible stages of strain hardening (I, II, and III), which are expected to arise from distinct developments of deformation-induced microstructures upon deformation. At stage I, the rate of work-hardening decreases sharply due to the large dislocation mean free path in the austenite and B2 grains (Figure 6(a1,a2,b1,b2) and Figure 7a,b) []. The rate further decreases to below zero due to the rapid relaxation of internal stress and strain at the austenite/B2 interface after the yielding of the hard B2 phase []. At stage II, the work-hardening rate increases rapidly with strain, attaining a maximum value near 4.3% true strain. This pronounced ascent stems in part from the rapid storage of dislocations within both the austenite and B2 grains (Figure 7(c3)), coupled with their pronounced accumulation at austenite/B2 interfaces (Figure 7(c1,c2)), which together engender robust forest dislocation hardening. Furthermore, heterogeneous distribution of dislocations within grains and at austenite/B2 interfaces contributes to substantial HDI hardening (Figure 5d). Together, these mechanisms account for the dramatic rise in work-hardening rate during Stage II. During stage III (4.3–12%), the specimen exhibits a gradual decrease in the work-hardening rate with increasing strain, but the work-hardening rate remains at a relatively high level, exceeding 2.7 GPa. This is expected to be due to the decreased capability of dislocation storage (Figure 7(d3)) due to the accelerated dynamic recovery (Figure 8a) and the dissolution of ordered domains (Figure 8g). The dynamic recovery process corresponds to the dislocation annihilation as the dislocations on parallel slip bands are close enough or the local stress is high enough to enable cross-slip [,]. However, at this stage, dislocations in austenite and B2 continue to increase, and the dislocations build up at the interface of the duplex steel, which leads to a strong HDI strengthening and therefore a high work-hardening rate.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a duplex lightweight steel with the compositions of Fe-30Mn-9Al-1C-1V-5Ni (wt.%) was developed with excellent strength and ductility and good work-hardening capability. The microstructural evolution, the contributions of various strengthening mechanisms to YS, and the deformation mechanisms were systematically investigated for this steel. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) This duplex lightweight steel, comprising austenite and B2 phases, can be produced through simple rolling and heat treatment. L′12 type LRO domains and VC nanoprecipitation are present within the austenite phase.

(2) This duplex lightweight steel demonstrates exceptional strength and ductility, with a YS of 1316 ± 16 MPa, a tensile strength of 1458 ± 11 MPa, and a total elongation of 11.7 ± 1.2%. It exhibits three discernible stages of work-hardening, characterized by a work-hardening rate that initially decreases and then increases, and finally remains at a relatively high level (2.7 to 3.7 GPa) with a slight decrease.

(3) The high YS of the duplex lightweight steel primarily originates from solution strengthening, dislocation interactions with LRO domains and VC precipitates, as well as from HDI strengthening caused by dislocation pile-ups at grain and phase boundaries. The excellent ductility of the duplex lightweight steel is attributed to the high dislocation storage capability of both the austenite and B2 phases, as well as the high HDI hardening near phase and grain boundaries.

Author Contributions

M.Z.: validation, formal analysis, data curation, and writing. H.Z.: conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, review, editing, and funding acquisition. R.W.: validation and data curation. X.Y.: validation and formal analysis. X.L.: validation and formal analysis. Z.X.: validation and formal analysis. W.W.: review and editing. H.W.: review and editing. Y.S.: review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFB3707502), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52201141 and 52574452), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515110692), State Key Laboratory of Solidification Processing in NPU (No. 2025-TS-03), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (No. cstc2021jcyj-msxmX1189), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M702662), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (No. G2025KY05042).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to be disclosed.

References

- Moon, J.; Park, S.-J.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, T.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Hong, H.-U.; Han, H.N.; Lee, J.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, C. Investigations of the microstructure evolution and tensile deformation behavior of austenitic Fe-Mn-Al-C lightweight steels and the effect of Mo addition. Acta Mater. 2018, 147, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Seo, C.-H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.K.; Kwak, J.H.; Chin, K.G.; Park, K.-T.; Kim, N.J. Effect of aging on the microstructure and deformation behavior of austenite base lightweight Fe–28Mn–9Al–0.8C steel. Scr. Mater. 2010, 63, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Gao, G.; Gui, X.; Feng, C.; Misra, R.D.K.; Bai, B. Uncovering microstructure–property relationship in Ni-alloyed Fe–Mn–Al–C low-density steel treated by hot-rolling and air-cooling process. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2024, 37, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Rana, R.; Haldar, A.; Ray, R.K. Current state of Fe-Mn-Al-C low density steels. Progress. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, W.; Zhao, H.; He, J.; Wang, K.; Zhou, B.; Ponge, D.; Raabe, D.; Li, Z. Formation mechanism of κ-carbides and deformation behavior in Si-alloyed FeMnAlC lightweight steels. Acta Mater. 2020, 198, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.J.; Welsch, E.; Ponge, D.; Haghighat, S.M.H.; Sandlöbes, S.; Choi, P.; Herbig, M.; Bleskov, I.; Hickel, T.; Lipinska-Chwalek, M.; et al. Strengthening and strain hardening mechanisms in a precipitation-hardened high-Mn lightweight steel. Acta Mater. 2017, 140, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Chen, X.P.; Cao, Z.X.; Mei, L.; Li, W.J.; Cao, W.Q.; Liu, Q. Synergistic strengthening effect induced ultrahigh yield strength in lightweight Fe30Mn11Al-1.2C steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 752, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Luo, Y.; Su, Y.; Lai, M. A novel high-Mn duplex twinning-induced plasticity lightweight steel with high yield strength and large ductility. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 2164–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Elkot, M.; Antonov, S.; Zhang, H.; Lai, M. Simultaneously enhancing strength-ductility synergy and strain hardenability via Si-alloying in medium-Al FeMnAlC lightweight steels. Acta Mater. 2023, 245, 118611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wei, S.; Cann, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Tasan, C.C. Composition-dependent slip planarity in mechanically-stable face centered cubic complex concentrated alloys and its mechanical effects. Acta Mater. 2021, 220, 117314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dasari, S.; Ingale, T.; Jiang, C.; Gwalani, B.; Srinivasan, S.G.; Banerjee, R. Introducing local chemical ordering to trigger a planar-slip-initiated strain-hardening mechanism in high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2023, 258, 119248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Slone, C.; Dasari, S.; Ghazisaeidi, M.; Banerjee, R.; George, E.P.; Mills, M.J. Ordering effects on deformation substructures and strain hardening behavior of a CrCoNi based medium entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2021, 210, 116829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Aitken, Z.H.; Pattamatta, S.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Z.G.; Srolovitz, D.J.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhang, Y.-W. Simultaneously enhancing the ultimate strength and ductility of high-entropy alloys via short-range ordering. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Hui, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Bai, S. Achieving ultra-high yield strength in austenitic low-density steel via drastic VC precipitation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 861, 144306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Cao, X.; Jiang, W.; Sun, L.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z. Formation of precipitates and their effects on the mechanical properties in a Fe–Mn–Al–C austenitic low-density steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 9422–9431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.-W.; Huang, M.; Scott, C.P.; Yang, J.-R. Interactions between deformation-induced defects and carbides in a vanadium-containing TWIP steel. Scr. Mater. 2012, 66, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Gao, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, C.; Mao, X. Copious intragranular B2 nanoprecipitation mediated high strength and large ductility in a fully recrystallized ultralight steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 226, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, H.; Kim, N.J. Brittle intermetallic compound makes ultrastrong low-density steel with large ductility. Nature 2015, 518, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantleon, W. Resolving the geometrically necessary dislocation content by conventional electron backscattering diffraction. Scr. Mater. 2008, 58, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.; Zhang, C.; Antonov, S.; Yu, H.; Guo, T.; Su, Y. Investigations of dislocation-type evolution and strain hardening during mechanical twinning in Fe-22Mn-0.6C twinning-induced plasticity steel. Acta Mater. 2020, 195, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Zhi, H.; Wang, H. Promoting strength-ductility synergy through sequential martensitic transformation in a hierarchical heterostructured eutectic high-entropy alloy. Int. J. Plast. 2025, 190, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, E.; Ponge, D.; Haghighat, S.M.H.; Sandlöbes, S.; Choi, P.; Herbig, M.; Zaefferer, S.; Raabe, D. Strain hardening by dynamic slip band refinement in a high-Mn lightweight steel. Acta Mater. 2016, 116, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Z. Enhancing strength–ductility synergy in high-Mn steel by tuning stacking fault energy via precipitation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 187, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, W.; Zhao, H.; Liebscher, C.H.; He, J.; Ponge, D.; Raabe, D.; Li, Z. Ultrastrong lightweight compositionally complex steels via dual-nanoprecipitation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, C.; Zhai, Q. Multiphase precipitation and its strengthening mechanism in a V-containing austenite-based low density steel. Intermetallics 2021, 134, 107179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Trang, T.T.T.; Lee, O.; Park, G.; Zargaran, A.; Kim, N.J. Improvement of strength–ductility balance of B2-strengthened lightweight steel. Acta Mater. 2020, 191, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X. Back stress strengthening and strain hardening in gradient structure. Mater. Res. Lett. 2016, 4, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, X. Perspective on hetero-deformation induced (HDI) hardening and back stress. Mater. Res. Lett. 2019, 7, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xue, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Gao, S.; Yang, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; et al. Machine-learning design of ductile FeNiCoAlTa alloys with high strength. Nature 2025, 643, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; De Cooman, B.C.; Sandlöbes, S.; Raabe, D. Size and orientation effects in partial dislocation-mediated deformation of twinning-induced plasticity steel micro-pillars. Acta Mater. 2015, 98, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Nam, C.H.; Zargaran, A.; Kim, N.J. Effect of B2 morphology on the mechanical properties of B2-strengthened lightweight steels. Scr. Mater. 2019, 165, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hui, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. Effect of vanadium on microstructure and mechanical properties of bainitic forging steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 771, 138653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Gao, Q.; Zou, Y.; Ding, H. Achieving strength ductility synergy of multiple hetero-structured Fe–24Mn–10Al–1C duplex lightweight steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 922, 147651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, H.L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, X.Y.; Ding, H. The synergy of strength and ductility in a hetero-structured lightweight steel with controlled distribution, size and volume fraction of B2 precipitates. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).