Abstract

GpsB is a conserved cell-cycle regulator in the Firmicute clade of Gram-positive bacteria that coordinates multiple aspects of envelope biogenesis. Recent studies demonstrate interactions between GpsB and the key division cytoskeleton FtsZ, suggesting that GpsB links cell division to various aspects of cell envelope biogenesis in Staphylococcus aureus and potentially other Firmicutes. We determined a 1.7 Å resolution crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of Staphylococcus aureus GpsB, revealing an asymmetric dimer with a bent conformation. This conformation is nearly identical to one of two conformations reported by Sacco et al., confirming the unique conformation of S. aureus GpsB compared to other Gram-positive bacteria. This structural agreement provides strong validation of the S. aureus GpsB fold and supports its proposed role in organizing the cell division machinery.

1. Introduction

GpsB is a widely conserved adaptor protein in Gram-positive Firmicutes (synonym Bacillota) that coordinates cell-cycle progression by coupling cell envelope biogenesis to the cell-division machinery. GpsB has two structured domains—an N-terminal dimerization domain and a C-terminal trimerization domain—which are separated by a flexible linker [1,2]. Thus, GpsB is thought to act as a hexamer that can bind to multiple cell division proteins simultaneously, thereby facilitating the spatiotemporal coordination of various molecular machines [3]. The N-terminal domain of GpsB, in addition to containing a membrane-binding loop that drives binding to the inner leaflet of the membrane [1], also binds small peptides bearing a consensus (S/T)-R-X-X-R-(R/K) motif. This motif is found in proteins such as PBP1A [4], FtsZ [5,6], EzrA [7], DivIVA [8], TarO/G [6], and FacZ [9], allowing GpsB to coordinate division site localization of multiple protein complexes. Consistent with these binding motifs, GpsB directly binds and regulates FtsZ [5], contributing to the correct placement of FtsZ and other Staphylococcal division proteins [9] and coordinating cell envelope growth to division [6], underlining its intriguing potential to communicate information between cell envelope synthesis and morphogenetic factors. Unsurprisingly, and presumably as a result of its coordination of these features, GpsB is necessary for normal S. aureus morphogenesis [10,11]. GpsB’s interactions with FtsZ [12] and various cell envelope synthesis factors [4] are conserved in other Firmicutes, suggesting its role as an adaptor between cell cycle and envelope growth is also broadly conserved.

Prior to 2024, structures for the N-terminal domain of GpsB had been described for Bacillus subtilis [4,13], Listeria monocytogenes [4], and s [4]. These GpsB orthologs adopt a conserved fold, showing a long parallel two-helix bundle with two short helices that form a 4-helix ‘cap’ at one end [1]. Notably, the central helical bundle is a rigid helix, reinforcing the model of GpsB as a linear adaptor scaffold.

Recently, Sacco et al. revealed a novel conformation of S. aureus GpsB (SaGpsB) [14], where the N-terminal homodimer adopts an asymmetric dimer, in which two protomers display a kinked helix conformation, mediated by a hinge formed by a three-residue insertion exclusive to Staphylococcus species. This hinge comprises a cluster of methionine residues (“MAD” or “MNN” insertion) not found in other Firmicutes, conferring conformational flexibility. Excising this insertion increases thermal stability and abolishes an overexpression lethal phenotype in Bacillus, suggesting functional tuning via flexibility. Thus, functional and structural divergence appears between S. aureus and other Gram-positives. Whereas GpsB in other species is rigid, SaGpsB seems conformationally dynamic, possibly acting as a regulatory switch in divisome assembly.

We present here a 1.7 Å X-ray crystal structure of the N-terminal helical dimer of the S. aureus GpsB protein. This structure is in strong agreement with one of two conformations observed previously in Sacco et al., providing independent validation of this novel conformation. Notably, our structure agrees with the most structurally divergent conformation compared to the rigid helix conformations of B. subtilis, S. pneumoniae, and L. monocytogenes, highlighting the structural divergence between species.

2. Results

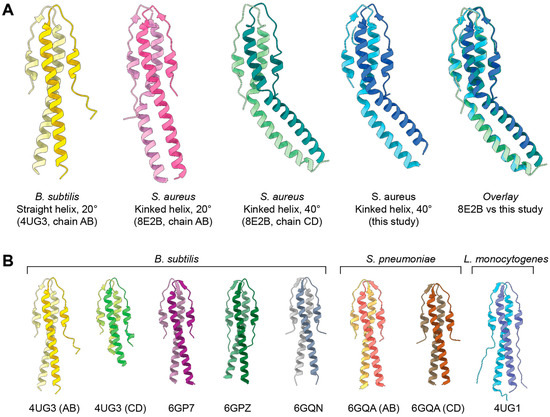

We independently crystallized the N-terminal domain (residues 1–75) of SaGpsB and determined its structure at 1.7 Å resolution (Figure 1A, Table 1). Our analysis shows an asymmetric dimer with a kinked helix conformation, in excellent agreement with the GpsB dimers seen in 8E2B.pdb (chains C/D) and 8E2C.pdb (chains A/B) (Figure 1A). Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between our model and 8E2B chains C/D is ~0.53 Å over all matching Cα atoms (132 residues). RMSD between our model and 8E2C chains A/B is ~0.57 Å over all matching Cα atoms (132 residues). This analysis underscores the similarity of the two structures. While 8E2B contains two SaGpsB dimers in the asymmetric unit, a dimer with a kinked helix of approximately 20° and a dimer with a kinked helix of approximately 40°, our structure best matches the 40° bent helix conformation (Figure 1A). RMSD between our model and the 20° bent helix conformation (8E2B chains A/B) is ~7.56 Å over all matching Cα atoms (132 residues), highlighting the differences between these two structures. However, RMSD is ~0.53 Å when considering only residues 1–47, and ~0.57 Å when considering only residues 48–75, showing that the structural differences between the two complexes can be explained by a rigid motion between the two regions of the protein.

Figure 1.

X-ray structure of SaGpsB residues 1–75. (A) Comparison of BsGpsB (yellow), SaGpsB conformation 1 (pink), SaGpsB conformation 2 (green), and SaGpsB from this study (blue). Each GpsB model is colored with two different shades of the same color to show the dimeric assembly. An overlay of the 40° kinked helix conformation from 8E2B and the 40° kinked helix structure from this study is shown (far right). (B) Comparison of GpsB from B. subtilis, S. pneumoniae, and L. monocytogenes. PDB codes are below each structure, with chain IDs labeled if more than one dimer was present in the asymmetric unit. Note that all GpsB structures from these three species show a straight helix conformation.

Table 1.

X-ray collection and refinement statistics.

As shown in Figure 1B, all previously reported structures of GpsB from B. subtilis, L. monocytogenes, and S. pneumoniae all display a straight helix conformation. Several of these structures were co-crystallized with a small (S/T)-R-X-X-R-(R/K) motif peptide, although the presence of the peptide does not appear to affect the overall conformation of the helical bundle. Both described SaGpsB conformations vary significantly from the nearly straight helices observed in BsGpsB, LmGpsB, and SpGpsB.

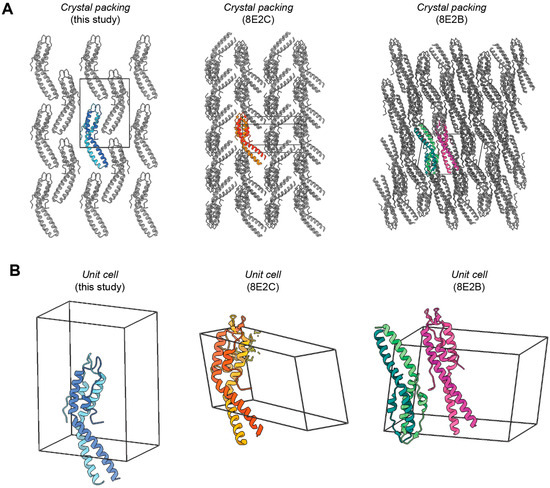

Importantly, our analysis shows a unique crystal packing morphology compared to the other reported structures of SaGpsB, 8E2B and 8E2C (Figure 2). This confirms that the kinked-helix conformation is not an artifact of specific crystal-packing conditions. Our data therefore supports the model proposed by Sacco et al., whereby the hinge-mediated flexibility serves as a dynamic switch in S. aureus. Although no ligand was present in our crystals, the conformation observed is virtually identical to SaGpsB bound to the (S/T)-R-X-X-R−(R/K) motif of PBP4 (8E2C.pdb), suggesting the asymmetric dimer is intrinsic to SaGpsB’s fold and not induced by ligand binding. Thus, this conformation likely represents the physiologically relevant state that mediates binding to partners.

Figure 2.

Crystal packing and unit cell arrangement for three SaGpsB crystal structures. (A) Crystal packing for our SaGpsB crystal structure (left) is compared with crystal packing for SaGpsB + FtsZ peptide (8E2C.pdb; center) and SaGpsB (8E2B.pdb; right). While our crystal structure and 8E2C both have a single copy of GspB dimer in the asymmetric unit, their crystal packing arrangement is unique, demonstrating that the conformation observed is not influenced by the crystal lattice. (B) Unit cell for each crystal structure is shown, with the same general orientation as in (A) but slightly tilted to show the outlines of the unit cell.

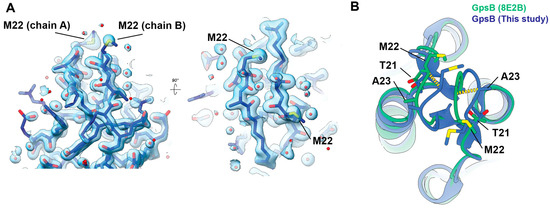

The only significant difference between our structural analysis is slight heterogeneity in the membrane-bending loop (residues ~17–27) (Figure 3), which may reflect dynamic motion of the hinge region, as suggested in Sacco et al. The high-quality electron density shows the conformation we observe is not a model building artifact, or due to low confidence in map quality at this interface (Figure 3A). Comparing the same region between our structure and the same SaGpsB structure from 8E2B shows a clear loop displacement between the two independent structures, showing that this region of the protein is able to adopt multiple conformations. This heterogeneity is expected for a loop region proposed to insert into the inner leaflet of the membrane [1]. An important caveat is that differences in the loop conformation observed in our structure may be influenced by the crystal packing arrangement. Further analysis of this membrane binding loop is required to understand the functional consequences, if any, of this structural plasticity.

Figure 3.

Comparison of SaGpsB membrane-bending loop. (A) 2mFo-DFc electron density map contoured at 2.2 sigma showing density for the membrane bending loop. Two views are shown, tilted by 90 degrees. (B) Zoom-in of the membrane binding loop (aa 17–27) of the SaGpsB dimer. The view in (B) is the same as in the right panel of (A), just shown in ribbon representation and with the SaGpsB dimer from 8E2B overlaid. The two conformations observed have loop displacements of 2.5–3.0 Å (yellow dashes).

3. Conclusions

Our independent crystal structure of the SaGpsB N-terminal domain validates and reinforces the asymmetric, hinge-mediated conformation first described by Sacco et al. While a rigid helical conformation is a defining features of other bacteria like B. subtilis, S. pneumoniae, and L. monocytogenes, Staph. aureus GpsB has a clear structural plasticity that is an intrinsic feature of the protein. These findings support the hypothesis that hinge flexibility enables regulatory control of divisome component assembly by modulating GpsB interactions with other binding partners. Together, this work affirms GpsB’s role as a dynamic adaptor in S. aureus cell-division and provides a solid structural foundation for further functional studies.

4. Materials & Methods

4.1. GpsB 1–75 Purification

GpsB residues 1–75 (from S. aureus strain NCTC 8325; Uniprot Q2FYI5; SAOUHSC_01462) were recombinantly purified as a fusion with an N-terminal 10xHis-SUMO tag. Briefly, BL21 (DE3) E. coli transformed with the expression plasmid were grown in Lysogeny Broth (LB) with 50 μg/mL kanamycin to mid log phase (OD600 ~ 0.6) and induced with 0.5 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 18 °C overnight. Cells were harvested in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF), lysed by sonication, and clarified via centrifugation at 28,000× g. Lysate was applied to Ni+-NTA resin (GoldBio, St Louis, MO, USA), washed with high salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1000 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole), and low salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole), and eluted with elution buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 300 mM Imidazole). Protein was dialyzed overnight into crystallization buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT), along with SUMO protease to cleave the purification tag. The following day, the uncleaved protein and free His-SUMO tag were removed by passing the eluent over Ni+-NTA resin. The protein was further purified by anion exchange chromatography using a 5 mL HiTrap Q FF column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) in a background buffer of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 using a linear gradient from 100 mM NaCl to 500 mM NaCl over 20 column volumes. Fractions containing GpsB were pooled, concentrated, and applied to a Superdex75 size exclusion chromatography column (Cytiva) in a background buffer of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl. The protein was concentrated to 5 mg/mL.

4.2. GpsB 1–75 Crystallization, Data Collection, and Model Building

Protein was tested for crystallization against common commercially available crystal screens using a Mosquito dropsetter (SPT Labtech, Hertfordshire, UK) with drops composed of 200 nL protein and 200 nL reservoir solution set over 30 μL reservoir volumes. Crystals were observed within one week over a reservoir solution composed of 1.0 M Succinic Acid, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 1% w/v PEG 2000 MME. The crystals were briefly soaked in reservoir supplemented with 15% ethylene glycol then cryocooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, using an incident beam of 1 Å in wavelength. Data were reduced in HKL-2000 [15]. The structure was phased by molecular replacement using Phaser [16] with PDB 8e8b as the search model [14]. Real space rebuilding was done in Coot [17], and reciprocal space refinements and validations were done in PHENIX [18]. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession number 9PV2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.B. and R.W.B.; methodology, N.I.N. and R.W.B.; software, N.I.N.; validation, N.I.N.; formal analysis, N.I.N. and R.W.B.; investigation, N.I.N. and R.W.B.; resources, R.W.B.; data curation, R.W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W.B.; writing—review and editing, T.M.B. and R.W.B.; visualization, R.W.B.; supervision, R.W.B.; project administration, R.W.B.; funding acquisition, R.W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by institutional start-up funds to R.W.B. from the UNC Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession number 9PV2 (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9PV2, accessed on 1 September 2025). The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. SER-CAT is supported by its member institutions, equipment grants (S10_RR25528, S10_RR028976 and S10_OD027000) from the National Institutes of Health, and funding from the Georgia Research Alliance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Halbedel, S.; Lewis, R.J. Structural Basis for Interaction of DivIVA/GpsB Proteins with Their Ligands. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 1404–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, L.R.; White, M.L.; Eswara, P.J. ¡vIVA La DivIVA! J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00245-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleverley, R.M.; Rismondo, J.; Lockhart-Cairns, M.P.; Van Bentum, P.T.; Egan, A.J.; Vollmer, W.; Halbedel, S.; Baldock, C.; Breukink, E.; Lewis, R.J. Subunit Arrangement in GpsB, a Regulator of Cell Wall Biosynthesis. Microb. Drug Resist. 2016, 22, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleverley, R.M.; Rutter, Z.J.; Rismondo, J.; Corona, F.; Tsui, H.-C.T.; Alatawi, F.A.; Daniel, R.A.; Halbedel, S.; Massidda, O.; Winkler, M.E.; et al. The Cell Cycle Regulator GpsB Functions as Cytosolic Adaptor for Multiple Cell Wall Enzymes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswara, P.J.; Brzozowski, R.S.; Viola, M.G.; Graham, G.; Spanoudis, C.; Trebino, C.; Jha, J.; Aubee, J.I.; Thompson, K.M.; Camberg, J.L.; et al. An Essential Staphylococcus aureus Cell Division Protein Directly Regulates FtsZ Dynamics. eLife 2018, 7, e38856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, L.R.; Sacco, M.D.; Khan, S.J.; Spanoudis, C.; Hough-Neidig, A.; Chen, Y.; Eswara, P.J. GpsB Coordinates Cell Division and Cell Surface Decoration by Wall Teichoic Acids in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0141322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, V.R.; Bottomley, A.L.; Garcia-Lara, J.; Kasturiarachchi, J.; Foster, S.J. Multiple Essential Roles for EzrA in Cell Division of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 80, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottomley, A.L.; Liew, A.T.F.; Kusuma, K.D.; Peterson, E.; Seidel, L.; Foster, S.J.; Harry, E.J. Coordination of Chromosome Segregation and Cell Division in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, T.M.; Sisley, T.A.; Mychack, A.; Walker, S.; Baker, R.W.; Rudner, D.Z.; Bernhardt, T.G. FacZ Is a GpsB-Interacting Protein That Prevents Aberrant Division-Site Placement in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, J.A.F.; Cooke, M.; Tinajero-Trejo, M.; Wacnik, K.; Salamaga, B.; Portman-Ross, C.; Lund, V.A.; Hobbs, J.K.; Foster, S.J. The Roles of GpsB and DivIVA in Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Division. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1241249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.F.; Saraiva, B.M.; Veiga, H.; Marques, L.B.; Schäper, S.; Sporniak, M.; Vega, D.E.; Jorge, A.M.; Duarte, A.M.; Brito, A.D.; et al. The Role of GpsB in Staphylococcus aureus Cell Morphogenesis. mBio 2024, 15, e03235-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.; King, A.; McKnight, L.; Horigian, P.; Eswara, P.J. GpsB Interacts with FtsZ in Multiple Species and May Serve as an Accessory Z-Ring Anchor. Mol. Biol. Cell 2025, 36, ar10. [Google Scholar]

- Rismondo, J.; Cleverley, R.M.; Lane, H.V.; Großhennig, S.; Steglich, A.; Möller, L.; Mannala, G.K.; Hain, T.; Lewis, R.J.; Halbedel, S. Structure of the Bacterial Cell Division Determinant GpsB and Its Interaction with Penicillin-Binding Proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 99, 978–998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sacco, M.D.; Hammond, L.R.; Noor, R.E.; Bhattacharya, D.; McKnight, L.J.; Madsen, J.J.; Zhang, X.; Butler, S.G.; Kemp, M.T.; Jaskolka-Brown, A.C.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus FtsZ and PBP4 Bind to the Conformationally Dynamic N-Terminal Domain of GpsB. eLife 2024, 13, e85579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z.; Minor, W. [20] Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997, 276, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A.J.; Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W.; Adams, P.D.; Winn, M.D.; Storoni, L.C.; Read, R.J. Phaser Crystallographic Software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40 Pt 4, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P.; Lohkamp, B.; Scott, W.G.; Cowtan, K. Features and Development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66 Pt 4, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebschner, D.; Afonine, P.V.; Baker, M.L.; Bunkóczi, G.; Chen, V.B.; Croll, T.I.; Hintze, B.; Hung, L.-W.; Jain, S.; McCoy, A.J.; et al. Macromolecular Structure Determination Using X-Rays, Neutrons and Electrons: Recent Developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2019, 75, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).