Abstract

Metallic glass alloys exhibit excellent properties, yet suffer from poor room-temperature plasticity, a limitation that restricts their engineering applications. Bulk metallic glass matrix composites (BMGMCs) have proven effective in enhancing the plasticity of metallic glasses, and the addition of alloying elements serves as a key strategy to regulate their microstructure and optimize the properties of these composites. This study aims to investigate the effects of a vanadium (V) addition on the mechanical properties and microstructure of Ti-based BMGMCs, while exploring the underlying mechanism of V’s influence. Using (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx (x = 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20) BMGMCs as test specimens, microstructural characterization was performed via X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and compressive mechanical properties were tested. The results indicate that a V addition refines dendrites without altering the phase composition, which remains composed of β-Ti crystals and an amorphous matrix. With the increase in V content, the compressive plastic strain shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing; when x = 12, the specimen exhibits the maximum compressive plastic strain, reaching 7.9%. Additionally, the volume fraction of the crystalline phase gradually increases with increasing V content. This study clarifies the mechanism by which V regulates the microstructure and properties of Ti-based BMGMCs, thereby providing theoretical and experimental insights for optimizing alloy compositions to enhance the mechanical performance.

1. Introduction

In recent years, metallic glass alloys have garnered extensive attention owing to their unique microstructures and exceptional properties [1,2]. They exhibit numerous advantages, including high strength, a high elastic limit, high magnetic permeability, and excellent electrical conductivity [3,4]. They have been widely used in applications such as semi-conductors, transformers, and high magnetic permeability materials [5,6,7]. However, these alloys suffer from poor room-temperature plasticity and are prone to catastrophic fracture [8], a critical drawback that significantly restricts their practical engineering applications. To address the low plasticity of monolithic metallic glass alloys, many researchers have developed bulk metallic glass matrix composites (BMGMCs), which have achieved certain improvements in plasticity. Specifically, Zr-based BMGMCs could effectively enhance the plasticity by introducing a crystalline phase into the glass matrix [9]. During in situ tensile tests of Ti-based BMGMCs, it was observed that the β-Ti dendrites in the glassy matrix effectively blocked the shear bands, forcing the plastic deformation to be distributed more evenly, thus enhancing the overall plasticity [10]. In carbon-fiber-reinforced Mg-based BMGMCs, in situ observations have indicated that a well-designed interface between the carbon fiber and the metallic glass matrix can improve the stress transfer efficiency. The interface can not only prevent the premature debonding of the reinforcement but also facilitate the initiation and propagation of multiple shear bands in the matrix, thereby enhancing the plasticity of the composite [11].

In general, BMGMCs are fabricated by introducing alloying elements to induce the in situ growth of crystalline phases within the glassy matrix, thereby forming a composite structure composed of both crystalline and amorphous phases [12]. The addition of such elements is one of the research hotspots in the field of bulk metallic glasses (BMGs), primarily owing to its simplicity and feasibility in practical experimental operations. Furthermore, the incorporation of alloying elements can fundamentally alter the microstructure and modulate the mechanical properties of BMGMCs.

According to previous studies, the addition of alloying elements exerts three primary effects on BMGMCs: ① It influences the thermal stability of the composites [13]; ② it enhances the strength and plasticity [14]; and ③ it improves the corrosion resistance [15]. In Zr-based BMGMCs, an increase in zirconium (Zr) content leads to a higher volume fraction of β-Zr dendrites, which, in turn, reduces the glass-forming ability; notably, the plasticity can exceed 35% [16]. In CuZr-based BMGMCs, increasing the Al content results in a gradual decrease in glass-forming ability, while the plasticity improves from a very low level to a value that can potentially make the material more ductile and less prone to catastrophic failure [17]. For Zr-based BMGMCs with ex situ reinforced Ta additions, the Ta5 specimen forms a core-shell structure, exhibiting a fracture strength of 1950 MPa and a plastic strain of 3.8%, whereas the Ta7 specimen undergoes brittle fracture with almost no plasticity [18]. Taking the Ti-based BMGMCs as the object, when the Mo content ranges from 0 to 2%, the yield stress increases significantly from 1185 MPa to 1380 MPa. In contrast, the increase in yield stress becomes much more gradual (from 1401 MPa to 1446 MPa) as the Mo content rises from 4% to 10%. Regarding the plasticity and fracture stress, a precipitous increase is noted as the Mo content increases from 4% to 10%. Specifically, when the Mo content reaches 10%, the plasticity and fracture stress increase to 31% and 2690 MPa, respectively [19]. In another Ti-based BMGMCs, the alloy with a 0 at% Nb content exhibits no plasticity, while its yield strength reaches 1690 MPa. With an increasing Nb content, the yield strength gradually decreases to 1422 MPa, whereas both the plastic strain and ultimate strength increase. When the Nb content reaches 10%, the ultimate strength is 2588 MPa and the plastic strain is dramatically improved to 36.4% [20]. Furthermore, the elemental content can also be adjusted by substituting other elements. For the Zr60Cu25Al10Fe5−xAgx BMGMCs, where Ag substitutes for Fe, when x = 0, the composite exhibits a high yield stress of 1772 MPa but a poor plastic strain of only 0.4%. When x = 2%, both the yield strength and plastic strain increase, reaching 1798 MPa and 1.4%, respectively. Furthermore, the plastic strain reaches a maximum value of 3.7% when x = 4% [21]. In conclusion, an increase in a specific alloying element not only modulates the volume fraction and the size of the crystalline phases in BMGMCs but also regulates their plasticity and strength. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism by which alloying elements govern the crystalline phase size, plasticity, and strength of BMGMCs remains to be elucidated.

The present study will focus on (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx BMGMCs, specifically investigating the effects of the vanadium (V) content on the volume fraction and the size of the crystalline phases, as well as on the plasticity and strength, while analyzing the corresponding influencing mechanisms.

2. Experimental Procedures

In this study, Ti-based bulk metallic glass matrix composites (BMGMCs) were used as the research objects. By varying the content of vanadium (V), six sets of specimens were prepared with compositions following the formula (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx (at.%), where x = 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. In the following text, these six sets of (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100, (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)96V4, (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)92V8, (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)88V12, (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)84V16, and (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)80V20 BMGMCs are represented by the codes V0, V4, V8, V12, V16, and V20, respectively. High-purity metals, including Ti (99.94%), V (99.96%), Zr (99.96%), Cu (99.96%), and Be (99.95%), were first homogenously mixed. The mixture was then melted 4–5 times in a vacuum arc melting furnace (model: DHL-500 II) under a high vacuum (10−4 Pa) to ensure homogeneous component distribution. Subsequently, six sets of as-cast V0, V4, V8, V12, V16, and V20 BMGMCs with dimensions of 4 mm and a length of 70 mm (φ4 × 70 mm) were prepared via the copper mold suction casting method.

The phase composition of the specimens was characterized via X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a diffractometer (model: Bruker D8 ADVANCE). The microstructures were investigated by scanning electronic microscopy (SEM, model: FEI Quanta 200F). Similarly, the side surface morphology of compressed specimens and the fracture surface morphology of the fractured specimens were also observed by SEM. For mechanical property testing, specimens with a diameter of 4 mm and a height of 8 mm were prepared. The room-temperature quasi-static compression tests were then conducted using a universal testing machine (model: E45.105) at a strain rate of 5 × 10−6 s−1.

Based on the images analysis software Image Pro Plus 6.0 (IPP 6.0), the microstructure parameters, such as the crystal volume fraction (fc), and the proportions of dendrites and granular crystals in the crystalline phase, were calculated by Formula (1) [22]:

where Ai was the area of the ith grain; A was the field area; N was the number of grains to be measured; i was the ith particle; and N was the total number of particles.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Element V on Ti-Based BMGMCs

3.1.1. Microstructure

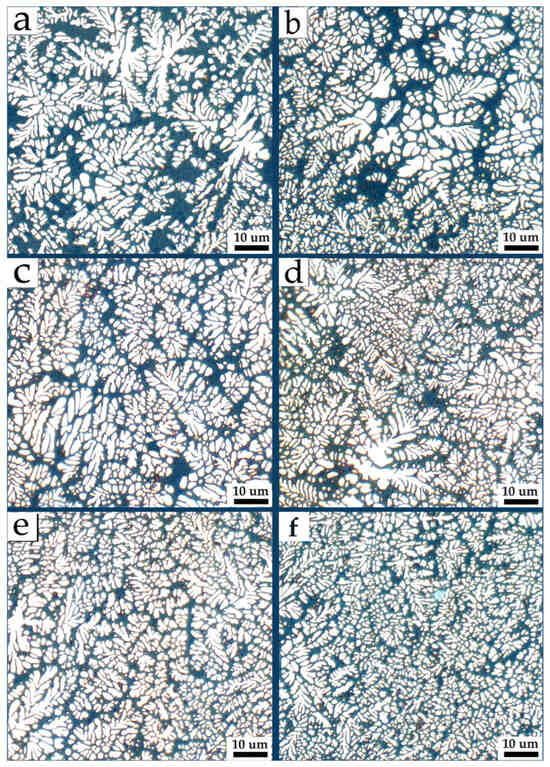

For the microstructural observation, specimens were cut from the mid-section of each as-cast ingot. The microstructures of the six as-cast BMGMC groups (V0, V4, V8, V12, V16, and V20) are observed by SEM, as shown in Figure 1. Specifically, Figure 1a corresponds to the (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx composite with x = 0 (i.e., 0% V content). It can be observed that the crystalline phases are distributed within the amorphous matrix. The microstructure is dominated by relatively well-developed dendritic crystals and contains a small amount of granular crystals. Some parameters for evaluating the dendrite size are measured and statistically analyzed using Image Pro Plus 6.0 (IPP 6.0) software [23], based on microstructure figures obtained from five non-overlapping microscopic fields. This approach minimizes bias and ensures an adequate volume of data to support reliable statistical analysis. For the V0 specimen, the volume fraction (fc) of the crystalline phases is approximately 45.5%, and dendritic crystals account for more than 90%, with only a small fraction (<10%) of granular crystals present. The average secondary dendrite arm spacing (SDAS) is 1.91 μm, indicating the growth of relatively coarse dendrites. Figure 1b corresponds to the composite with a 4% V content, where the average SDAS decreases to 1.62 μm. The volume fraction of the crystalline phases increases to approximately 47.3%, with dendritic crystals making up about 86% and granular crystals accounting for approximately 14%. This observation reveals that, compared with the V0 specimen, the crystalline phases in the 4% V composite exhibit a reduced size (reflected by a smaller SDAS) but an increased volume fraction. In Figure 1c, the average SDAS of the V8 specimen is further reduced to 1.44 μm, which indicates a significant suppression of dendritic growth. Furthermore, the volume fraction of the crystalline phases in the V8 specimen is roughly 50.6%; among these, dendritic crystals constitute ~80%, while granular crystals increase to roughly 20%. Compared with the V4 specimen, the V8 specimen exhibits an increased content of crystalline phases, in which the proportion of dendritic crystals decreases, whereas that of granular crystals increases, and the crystals undergo further refinement. Figure 1d presents the composite with a 12% V content, in which a notable microstructural change is observed: the average SDAS is 1.36 μm. Additionally, the volume fraction of the crystalline phases reaches 53.9%, with dendritic crystals accounting for approximately 75% and granular crystals making up around 25% of the total crystalline phase. For the V16 specimen (corresponding to Figure 1e), the average SDAS is reduced to 1.19 μm, which indicates significant dendritic refinement. The volume fraction of the crystalline phases reaches 57.5%, where dendritic crystals account for approximately 68%, while granular crystals occupy a proportion of 32%. Figure 1f corresponds to the V20 specimen, whose average SDAS drops to 1.12 μm, approaching the size of granular crystals. Additionally, the volume fraction of the crystalline phases reaches 58%, in which dendritic crystals account for approximately 64% and granular crystals for 36%.

Figure 1.

The microstructure of (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx BMGMCs: (a) V0; (b) V4; (c) V8; (d) V12; (e) V16; and (f) V20.

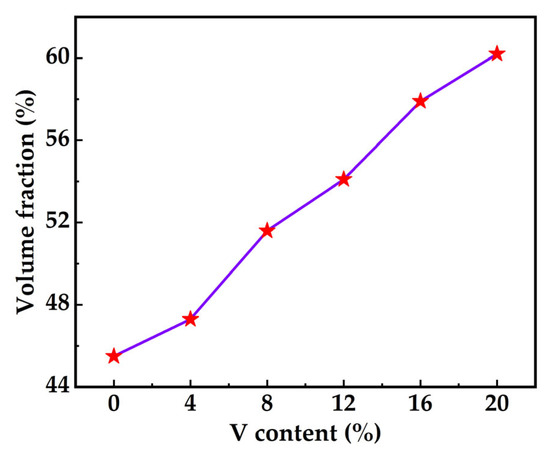

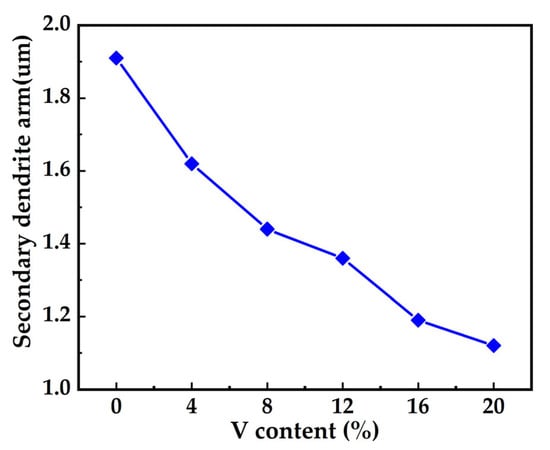

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that the crystalline phases of all six specimen groups are composed of dendritic crystals and granular crystals. From the V0 to V20 specimens, the dendritic crystals not only undergo a gradual refinement in size but also exhibit a continuous decrease in their proportion relative to the total crystalline phases, whereas the proportion of granular crystals increase significantly. Overall, the volume fraction of the crystalline phase shows an upward trend. Specifically, the volume fraction of the β-Ti crystals gradually increases with increasing V content, as presented in Figure 2. The relationship between the secondary dendrite arm spacing and V content is plotted in Figure 3, which demonstrates that the addition of the V element can refine the β-Ti crystals.

Figure 2.

The volume fraction of the β-Ti crystals in (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx BMGMCs.

Figure 3.

The secondary dendritic arm spacing of the β-Ti dendrites.

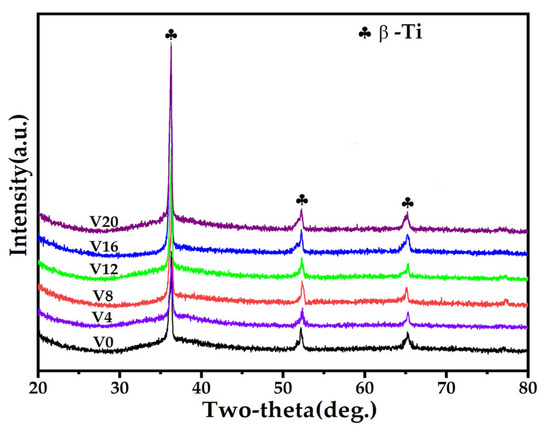

Figure 4 presents the XRD patterns of the six BMGMC groups. It can be seen that each diffraction spectrum is a diffraction peak with a crystal phase superimposed on the diffuse peak, corresponding to the BCC β-Ti crystal phase, indicating that the microstructure consists of a BMG matrix and β-Ti solid-solution two phases. Therefore, all six BMGMCs are composed of β-Ti crystals and amorphous. As evident from the figure, the intensity of the β-Ti crystal diffraction peaks varies with increasing V content, which reflects the effect of V on the volume fraction and size of β-Ti crystals. Notably, the V addition does not alter the phase composition of the BMGMCs, indicating that increasing the V content does not induce phase transformation.

Figure 4.

The XRD patterns of (Ti51Zr25Cu6Be18)100−xVx BMGMCs.

3.1.2. Mechanical Properties

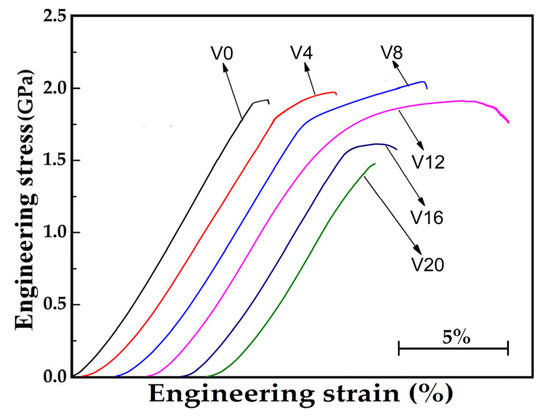

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the mechanical property data, three parallel compression specimens were tested for each of the six Ti-based BMGMCs. The mechanical properties were evaluated via compression testing using a universal testing machine with a load accuracy of ±0.5% and a displacement accuracy of ±0.001 mm, and the resultant room-temperature stress–strain curves of the six BMGMCs are presented in Figure 5. The yield strength (σy), maximum strength (σmax), and plasticity (εp) were calculated based on the stress–strain curves, with an experimental error of ±5 MPa and ±0.2% (determined by the standard deviation of the data from the three parallel samples), as shown in Table 1. It can be seen that the plasticity first increases and then decreases with increasing V content. Specifically, when x = 12 (corresponding to specimen V12), the εp reaches its maximum value of 7.9%. Similarly, the maximum strength also exhibits an increase first and then a decrease, with the highest value of 2051 MPa observed in the V8 specimen (x = 8). In contrast, the yield strength (σy) gradually decreases, with the V0 specimen showing the highest yield strength of 1898 MPa. These findings demonstrate that the addition of V exerts a significant effect on the mechanical properties of Ti-based BMGMCs.

Figure 5.

The compression stress–strain curves of V0 to V20 BMGMCs specimens.

Table 1.

The compression properties of V0 to V20 BMGMCs specimens.

3.1.3. Observation of the Surface of the Fractured Specimen

Researchers determine the fracture mode of specimens by analyzing the morphological characteristics of the fracture surfaces of the fractured specimens [24,25]. For brittle fracture and ductile fracture, the typical surface morphological features of ductile fracture include vein patterns and shear-sliding steps, whereas the fracture characteristic of brittle fracture involve the presence of some smooth regions and a viscous flow layer on the fracture surface [26,27]. In the present study, the surface morphology of compressed fracture specimens is observed via SEM, and a schematic diagram of the fracture surface and side surface is provided in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the fracture surface and side surface of the compressed fracture specimens.

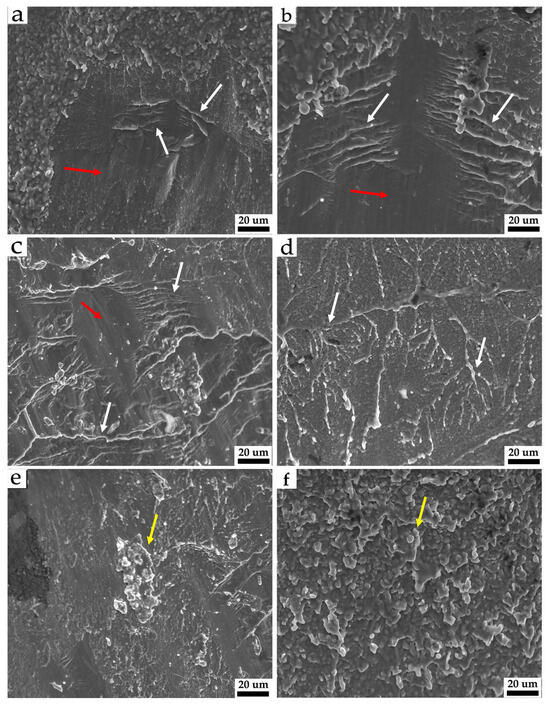

The fracture surface of the V0 specimen was observed, with the results corresponding to Figure 7a. As shown, most regions of the fracture surface consist of smooth areas (as indicated by the red arrows) and a viscous flow layer formed by high temperatures generated at the moment of fracture. A small number of fringe-like stripes and a limited number of shear-sliding steps are also present (as indicated by the white arrows in the figure). This indicates that the V0 specimen undergoes brittle fracture with its low plasticity. The fracture surface of the V4 BMGMCs is observed, corresponding to Figure 7b. The fracture surface of the V4 specimen features smooth regions, fringe-like stripes, and a limited number of shear-sliding steps. Compared with the V0 specimen, it exhibits more fringe-like stripes and shear-sliding steps, along with fewer smooth regions. This indicates that the V4 specimen possesses a certain degree of plasticity, which is consistent with the results of the compression tests. Additionally, the V4 specimen shows a larger plastic deformation ability than the V0 specimen. As shown in Figure 7c, a large number of distinct shear-sliding steps are observed on the fracture surface of the V8 specimen. Additionally, some well-developed pulse-like garlands are present, whereas the number of vein-like rosettes is relatively small. Nevertheless, the V8 specimen still exhibits more significant plastic deformation compared with the V0 and V4 specimens. Figure 7d presents the fracture surface scan of the V12 specimen. As observed, a large number of shear-sliding steps are aggregated, and typical river-like patterns are also present. Notably, the quantity and size of ridge patterns on the fracture surface can reflect the plastic deformation capacity of BMGMCs. The presence of shear-sliding steps indicates that the material is obstructed by the dendritic phase during the shearing process. This confirms that the V12 specimen has better plasticity than the V8 specimens. For the V16 specimen (see Figure 7e), no special fracture morphology was observed on its fracture surface. However, typical “droplets” (as indicated by the yellow arrows in the figure) are present, formed by the softening and melting of the BMG due to the high temperature at the moment of fracture. Therefore, the plasticity of the V16 specimen is relatively low. Figure 7f shows the fracture surface scan of the V20 BMGMC specimen. Some very tiny dimples (as indicated by the yellow arrows in the figure) can be found, measuring about a micron. Despite the presence of these dimples, the V20 composition specimen still shows relatively low plasticity, which is attributed to its excessively small crystalline phase size.

Figure 7.

The appearance of fracture surface of the specimens after compression fracture: (a) V0, (b) V4, (c) V8, (d) V12, (e) V16, and (f) V20.

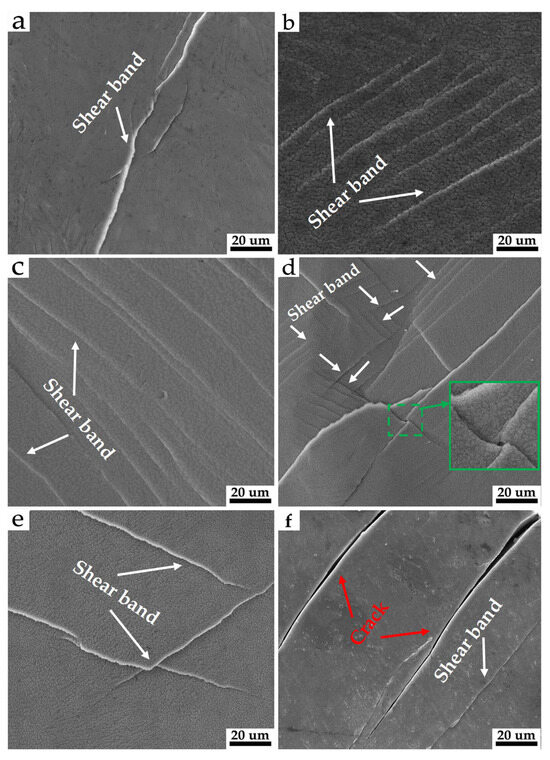

3.1.4. Observation of the Side Surfaces of Fractured Specimens

In the study of such BMGMCs, the characteristics of shear bands are typically used to characterize plastic deformation [28,29,30]. Figure 8 shows SEM images of the side surfaces of the six fractured specimens, where Figure 8a–f correspond to the V0 to V20 specimens, respectively. As shown in Figure 8a, the side surface of the V0 specimen contains a small number of sparsely distributed shear bands, which propagate along a straight path. These shear bands traverse the entire specimen along the direction of maximum shear stress, a typical feature of brittle fracture that results in low plasticity. Compared with the V0 specimen, the V4 specimen (Figure 8b) exhibits a significant increase in the number and density of shear bands, and these shear bands are approximately parallel. This indicates that the V4 specimen has a higher plasticity than the V0 specimen. Similarly, from the V4 to V8 specimens, the number and density of shear bands continue to increase, leading to a corresponding continuous improvement in plasticity. As shown in Figure 8d, the V12 specimen has a significantly higher shear band density than the V8 specimen, with multiple sets of intersecting shear bands (as indicated by the white in different directions). This phenomenon arises because the stress concentration effect of crystalline phases induces the formation of new shear bands. Meanwhile, the elastic deformation capacity of these crystals dissipates part of the shear energy, hindering the rapid propagation of primary shear bands. This mechanism not only contributes to the continuous improvement of plasticity but also explains why some shear bands are small in size. Consequently, the plasticity of the V12 specimen is higher than that of the V8 specimen. When the V content reaches 16%, as shown in Figure 8e, the shear bands are sparsely distributed and significantly reduced in number. It is known that, from V8 to V12 specimens, the plasticity decreases sharply. When the V content reaches 20%, corresponding to Figure 8f, almost no shear bands are observed, but there are obvious macroscopic cracks that propagate through the specimen along the direction of maximum shear stress. This leads to nearly no plastic deformation and brittle fracture. In summary, the addition of V regulates the characteristics of shear bands by modifying the features of crystalline phases, with an optimal addition range of 8–12 at.%.

Figure 8.

The appearance of side surface of fractured specimens after compression fracture: (a) V0, (b) V4, (c) V8, (d) V12, (e) V16, and (f) V20.

4. Discussions

In the amorphous composite system, vanadium (V) can not only promote the formation of crystalline phases but also tailor the characteristics of crystals, including their morphology, size, and volume fraction [31]. With respect to the crystalline phase content, an increase in V content promotes a gradual rise in the volume fraction of the crystalline phases. This is attributed to the ability of V atoms to act as nucleation sites during the crystallization process, which significantly reduces the energy barrier required for nucleation [32]. This creates favorable conditions for the ordered arrangement of atoms into a crystalline structure, thereby significantly increasing the probability of the transformation from the amorphous phase to the crystalline phase. Regarding the crystal morphology, at low V contents, the crystals tend to exhibit a dendritic structure. As the V content increases, although the content of granular crystals increases, the crystal phases are always dominated by dendrites, which is consistent with the findings reported by Sun, Y. et al. [33]. This is because a higher V content modifies the diffusion direction and rate of atoms within the amorphous matrix, which, in turn, ensures that the growth rates of crystalline phases in different directions become more uniform, ultimately leading to the formation of granular crystals [34]. With respect to the crystal size, as the V content increases, the sizes of both dendrites and granular crystals gradually decrease. This is attributed to the fact that excessive V atoms form a large number of nucleation sites in the system. These numerous nucleation sites compete for limited atomic resources, restricting the growth space of individual crystals and resulting in the refinement of the crystal size [35].

When the V content is denoted as x = 0, the volume fraction of the amorphous phase is higher than that of the crystalline phase. Consequently, the V0 specimen exhibits the typical mechanical properties of amorphous materials, including a high strength, low plasticity, and high brittleness. For the V4 specimen (x = 4), compared with the V0 specimen, the volume fraction of the ductile crystalline phase increases, leading to a decrease in yield strength and an increase in plasticity. Additionally, the V4 specimen exhibits strain hardening after yielding, resulting in a maximum compressive strength (σmax) that is higher than that of the V0 specimen. However, since the amorphous content of the V4 specimen is still higher than the crystalline content, its plasticity remains restricted to a relatively low level. In the case of the V8 specimen (x = 8), the crystalline phase content exceeds the amorphous content, with the specimen dominated by crystalline phases. As a result, the V8 specimen has a lower yield strength and higher plasticity than the V4 specimen, with the plasticity increasing by 97% relative to the V4 specimen. Similarly, for the V12 specimen (x = 12), the crystalline phase content increases to 54.9%, and its plasticity continues to increase while its strength decreases. However, when x = 16, the crystalline phase content in V16 specimen reaches 57.5%. In the crystalline phase, dendrites are the dominant morphology compared to fine granular crystals. However, the proportion of granular crystals increases to 32%, and their influence on the properties cannot be ignored. Fine granular crystals restrict plasticity, because the fine granular crystals cannot effectively hinder the propagation of shear bands [36]. This leads to the unconstrained propagation of shear bands and the limited formation of new shear bands, making it difficult for the plasticity to be improved further. Compared with the V12 specimen, the V16 specimen exhibits a lower plasticity despite its higher crystalline phase content. Similarly, when the V content reaches 20% (V20 specimen), although the crystalline phase content is as high as 60.1%, the crystalline phases are still dominated by dendritic crystals. Notably, the proportion of fine granular crystals in the total crystalline phases reaches 32%, which exerts a significant influence on the plastic deformation capacity. The infinite propagation of shear bands can easily evolve into cracks, ultimately leading to brittle fracture [37]. This is consistent with the observation of unlimited crack propagation and low-plasticity brittle fracture on the side surface of the fractured specimen.

For the V0 to V12 specimens, an increase in the crystal content contributes to an enhanced plasticity. Meanwhile, a decrease in the crystal size tends to reduce the plasticity. Notably, the beneficial effect of an increased crystal content on improving plasticity is more pronounced than the detrimental effect of the reduced crystal size. This dominance of the beneficial effect results in an increased plasticity across the V0–V12 range. For the V12 to V20 specimens, however, the detrimental effect of the reduced crystal size outweighs the beneficial effect of the increased crystal content, leading to a decline in plasticity. Collectively, the plasticity of the V0 to V20 specimens exhibits a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. In summary, the vanadium (V) element influences the mechanical properties by regulating the characteristics of the secondary crystalline phase, with an optimal addition range of 8–12%. This regularity provides an important reference for the composition design and performance regulation of amorphous composites.

5. Conclusions

① The addition of vanadium (V) can refine the dendrites without altering the phase composition of the Ti-based BMGMCs. And the addition of V content can refine dendritic crystals, enhance the volume fraction of crystalline phases, and induce a gradual increase in the proportion of granular crystals relative to the total crystalline phases.

② With an increasing V content, the yield strength of Ti-based BMGMCs decreases continuously, while both the compressive plastic strain and maximum compressive strength first increase and then decrease. Specifically, the V12 specimen exhibits the maximum compressive plastic strain of 7.9%, and the V8 specimen achieves a maximum compressive strength of 2051 MPa.

③ V influences the evolution of shear bands by regulating the characteristics of crystalline phases, with 8–12% identified as the optimal V addition range.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H., J.L. and G.W.; data curation, X.H.; investigation, X.H., J.L. and G.W.; software, X.H.; writing—original draft, X.H.; writing—review and editing, X.H., J.L., G.W., B.C., C.W. and Y.O.; visualization, B.C., C.W. and Y.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2023JJ50453), Science Research Excellent Youth Project of Hunan Educational Department (Grant No. 24B0709), and Social Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 23ZDB033).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

References

- Poulsen, H.F.; Wert, J.A.; Neuefeind, J.; Honkimäki, V.; Daymond, M. Measuring strain distributions in amorphous materials. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.P.; Liu, J.W.; Yang, K.J.; Xu, F.; Yao, Z.Q.; Minkow, A.; Fecht, H.J.; Ivanisenko, J.; Chen, L.Y.; Wang, X.D.; et al. Effect of pre-existing shear bands on the tensile mechanical properties of a bulk metallic glass. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, J.; Seetharaman, S.; Gupta, M. Processing and properties of aluminum and magnesium based composites containing amorphous reinforcement: A review. Metals 2015, 5, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.S.; Kim, C.P.; Lee, S.; Kim, N.J. Microstructure and tensile properties of high-strength high-ductility Ti-based amorphous matrix composites containing ductile dendrites. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 7277–7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ahmadi, A.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Abedinzadeh, R.; Abed, A.M.; Smaisim, G.F.; Toghraie, D. Investigation of the mechanical properties of different amorphous composites using the molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Z. Recent advances and future developments in Fe-based amorphous soft magnetic composites. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 616, 122440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Pailhes, S.; Debord, R.; Ruta, B.; Gravier, S.; Blandin, J.J.; Blanchard, N.; Gomes, S.; Assy, A.; Tanguy, A.; et al. Thermal transport properties in amorphous/nanocrystalline metallic composites: A microscopic insight. Acta Mater. 2017, 136, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Wang, X.; Shao, Y.; Chen, N.; Liu, X.; Yao, K.F. A Ti–Zr–Be–Fe–Cu bulk metallic glass with superior glass-forming ability and high specific strength. Intermetallics 2013, 43, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Saida, J.; Zhao, M.; Lu, S.; Wu, S. In-situ Ta-rich particle reinforced Zr-based bulk metallic glass matrix composites with tensile plasticity. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 775, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ye, H.Y.; Shi, J.Y.; Yang, H.J.; Qiao, J.W. Dendrite size dependence of tensile plasticity of in situ Ti-based metallic glass matrix composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 583, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qi, L.; Chao, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, J. Highly thermal conductive Csf/Mg composites by in-situ constructing the unidirectional configuration of short carbon fibers. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liu, C.; Yan, Y.Q.; Liu, S.; Ma, X.; Yue, S.; Shan, Z.W. Elemental partitioning-mediated crystalline-to-amorphous phase transformation under quasi-static deformation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Hua, D.; Zhou, Q.; Pei, X.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Liu, W. Concurrently achieving strength-ductility combination and robust anti-wear performance in an in-situ high-entropy bulk metallic glass composite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 272, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasiak, M.; Sobieszczańska, B.; Łaszcz, A.; Biały, M.; Chęcmanowski, J.; Zatoński, T. Fabrication and comprehensive evaluation of Zr-based bulk metallic glass matrix composites for biomedical applications. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 4087–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hu, L.; Lin, B.; Wang, Y.; Tang, J.; Qi, L.; Liu, X. Significant improvement of corrosion resistance in laser cladded Zr-based metallic glass matrix composite coatings by laser remelting. Corros. Sci. 2024, 238, 112360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Formation and mechanical properties of a Zr73Al8Cu6Ni13 bulk metallic glass composite containing in-situ beta-Zr dendrites. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 801, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xu, J. Improving plasticity and toughness of Cu-Zr-Y-Al bulk metallic glasses via compositional tuning towards the CuZr. J. Mater. Res. 2010, 25, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.S.; Wu, J.Y.; Liu, Y.T. Effect of the volume fraction of the ex-situ reinforced Ta additions on the microstructure and properties of laser-welded Zr-based bulk metallic glass composites. Intermetallics 2016, 68, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.M.; Lin, S.F.; Zhu, Z.W.; Zhang, B.; Li, Z.K.; Zhang, L.; Fu, H.M.; Wang, A.M.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.W.; et al. The design and mechanical behaviors of in-situ formed ductile dendrite Ti-based bulk metallic glass composites with tailored composition and mechanisms. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 732, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Z.; Ma, D.Q.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Ma, M.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, R.P. Enhancing the compressive and tensile properties of Ti-based glassy matrix composites with Nb addition. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2017, 463, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sun, W.C.; Qi, H.N.; Lv, J.W.; Wang, F.L.; Ma, M.Z.; Zhang, X.Y. Effects of Ag substitution for Fe on glass-forming ability, crystallization kinetics, and mechanical properties of Ni-free Zr–Cu–Al–Fe bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 827, 154385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.E.; Aronin, A.S.; Kholstinina, N.N. On the determination of the volume fraction of the crystalline phase in amorphous-crystalline alloys. Phys. Solid State 2010, 52, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, V.; Singh, K. Crystallization kinetics study of magnesium vanadate glasses using non-isothermal method. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 595, 121820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Su, S.; Fu, W. Strain-induced structural evolution of interphase interfaces in CuZr-based metallic-glass composite reinforced by B2 crystalline phase. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 258, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.J.; Wang, W.H.; Greerm, A.L. Intrinsic plasticity or brittleness of metallic glasses. Phil. Mag. Lett. 2005, 85, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgerdi, J.N.; Marquis, G.; Anbarlooie, B.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; Gupta, M. Microstructure-sensitive investigation on the plastic deformation and damage initiation of amorphous particles reinforced composites. Compos. Struct. 2016, 142, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.J.; Kim, C.P.; Lee, S. Tensile deformation behavior of two Ti-based amorphous matrix composites containing ductile β dendrites. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 552, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gong, P.; Yang, X.; Hu, H.; Chi, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Zr-based metallic glass composites with size-variable tungsten reinforcements. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.T.; Sohn, S.A.; Curtarolo, S.; Hofmann, D.; Schroers, J. Tension-compression asymmetry of shear band stability in bulk metallic glasses. Materialia 2025, 40, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Narayan, R.L.; Zhou, K.; Babicheva, R.; Ramamurty, U.; Shan, Z.W. A real-time TEM study of the deformation mechanisms in β-Ti reinforced bulk metallic glass composites. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 818, 141427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Sun, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X. Effect of vanadium reinforcement on the microstructure and mechanical properties of magnesium matrix composites. Crystals 2021, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Fan, H.; Ning, Z.; Huang, Y. Effect of crystalline phase on deformation behaviors of amorphous matrix in a metallic glass composite. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 872, 144957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayebi, B.; Delbari, S.A.; Asl, M.S.; Ghasali, E.; Parvin, N.; Shokouhimehr, M. A nanostructural approach to the interfacial phenomena in spark plasma sintered TiB2 ceramics with vanadium and graphite additives. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 222, 109069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.L.; Sun, X.D.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.G.; Li, X.D. Effect of vanadium content on microstructure and properties of in situ TiC reinforced V x FeCoNiCu multi-principal-element alloy matrix composites. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2021, 28, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Liao, Y.; Gu, J. The influence of vanadium element on the microstructure and mechanical properties of (FeCoNi)100-xVx high-entropy alloys. Mater. Charact. 2022, 192, 112232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Nie, L.H.; Hui, X.D.; Wang, T.; Wei, B. Ultrasonic excitation induced nanocrystallization and toughening of Zr46.75Cu46.75Al6.5 bulk metallic glass. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 45, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhu, Z.W.; Li, S.T.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Z.K.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.F. Shear band evolution and mechanical behavior of cold-rolled Zr-based amorphous alloy sheets: An in-situ study. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 181, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).