Abstract

The synthesis and crystal structures of three heteroleptic complexes of Zn(II) and Cd(II) with pyridine ligands (ethyl nicotinate (EtNic), N,N-diethylnicotinamide (DiEtNA), and 2-amino-5-picoline (2Ampic) are presented. The complex [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2] (1) showed a distorted tetrahedral coordination geometry with two EtNic ligand units and two chloride ions as monodentate ligands. Complexes [Zn(DiEtNA)(H2O)4(SO4)]·H2O (2) and [Cd(OAc)2(2Ampic)2] (3) had hexa-coordinated Zn(II) and Cd(II) centers. In the former, the Zn(II) was coordinated with three different monodentate ligands, which were DiEtNA, H2O, and SO42−. In 3, the Cd(II) ion was coordinated with two bidentate acetate ions and two monodentate 2Ampic ligand units. The supramolecular structures of the three complexes were elucidated using Hirshfeld analysis. In 1, the most important interactions that governed the molecular packing were O···H (15.5–15.6%), Cl···H (13.6–13.8%), Cl···C (6.3%), and C···H (10.3–10.6%) contacts. For complexes 2 and 3, the H···H, O···H, and C···H contacts dominated. Their percentages were 50.2%, 41.2%, and 7.1%, respectively, for 2 and 57.1%, 19.6%, and 15.2%, respectively, for 3. Only in complex 3, weak π-π stacking interactions between the stacked pyridines were found. The Zn(II) natural charges were calculated using the DFT method to be 0.8775, 1.0559, and 1.2193 for complexes 1–3, respectively. A predominant closed-shell character for the Zn–Cl, Zn–N, Zn–O, Cd–O, and Cd–N bonds was also concluded from an atoms in molecules (AIM) study.

Keywords:

cadmium(II); zinc(II); pyridine-type ligand; Hirshfeld; intermolecular interactions; X-ray 1. Introduction

Metallosupramolecular complexes are currently attracting a lot of attention because of their diverse uses in different applications, such as gas storage, optics, catalysis, electronic conductivity, and magnetism [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Non-covalent interactions, namely aromatic π⋯π stacking and H-bonding interactions, are important for the construction of supramolecular structures from the self-assembly of diverse components [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. These interactions, along with van der Waals forces, play important roles in a variety of domains, including crystal engineering, inorganic chemistry, biochemistry, and others [33,34,35,36].

Different metal ions have various characteristics and different modes of coordination, which represent important factors in determining the molecular and supramolecular structures of complexes. For instance, metal ions with d10 configurations, such as Zn(II) and Cd(II), when reacting with organic ligands, frequently exhibit several coordination numbers [37,38,39,40]. With their spherical d10 configuration, these metal ions show rather spherical and non-selective coordination, with coordination numbers simply governed by the size of the metal ion and the ligands. Because of their structural flexibility and their significance as luminescent materials and in ligand exchange chromatography, this category of complexes has received a lot of attention [41,42,43,44,45]. In addition, complexes of Zn(II) have interesting biological applications [46]. Among neutral aromatic N-donor ligands, pyridine derivatives are important ligands [47] for constructing various coordination compounds [48,49,50,51,52,53] with diverse applications [54,55,56]. These compounds can be used to treat brain illnesses and neurological diseases and are also used as an anesthetic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer agent [57]. Additionally, the nature of the small anion has a significant impact on the complex’s structure [58,59,60,61,62,63]. Hence, combining metal ions with nitrogen donor ligands and a small anionic oxygen donor could be a way to synthesize new heteroleptic complexes.

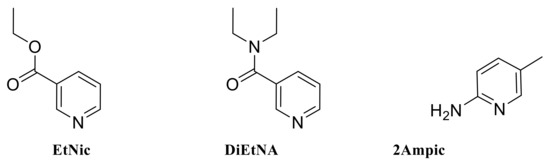

In this work, new Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes with the pyridine derivatives (Figure 1) ethyl nicotinate (EtNic), N,N-diethylnicotinamide (DiEtNA), and 2-amino-5-picoline (2Ampic) were synthesized, and their supramolecular structures were characterized using X-ray single-crystal structure and Hirshfeld analyses. The charge distribution and bonding were studied using DFT-based natural charge calculations and the atoms in molecules (AIM) method.

Figure 1.

Structures of the studied ligands EtNic [64,65,66], DiEtNA [67,68,69,70] and 2Ampic [71,72,73].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Physical Measurements

All chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade and were used without additional purification, as received from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). CHN analysis was performed using a PerkinElmer 2400 Elemental Analyzer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The metal content was measured with a Shimadzu atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AA-7000 series, Shimadzu, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan).

2.2. Synthesis of Complexes 1–3

A similar procedure was used to prepare the three complexes. An aqueous solution of the metal salt was mixed with an ethanolic solution of the functional ligand. The resulting clear solution was left for slow evaporation at room temperature for a couple of days. After a week, colorless crystals of the target compounds suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained.

2.2.1. [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2] (1)

Complex 1 was prepared by mixing a 10 mL aqueous solution of ZnCl2 (13.6 mg, 0.1 mmol) with a 10 mL ethanolic solution of EtNic (30.2 mg, 0.2 mmol). C16H18Cl2N2O4Zn: Yield: 85%; Anal. Calc.: C, 43.81; H, 4.14; N, 6.39; Zn, 14.91%. Found: C, 43.50; H, 4.06; N, 6.25; Zn, 14.79%.

2.2.2. [Zn(DiEtNA)(H2O)4(SO4)]·H2O (2)

Complex 2 was prepared by mixing equimolar amounts of a 10 mL aqueous solution of ZnSO4.7H2O (28.8 mg, 0.1 mmol) with a 10 mL ethanolic solution of DiEtNA (17.8 mg, 0.1 mmol). C10H24N2O10SZn: Yield: 79%; Anal. Calc.: C, 27.95; H, 5.63; N, 6.52; Zn, 15.22%. Found: C, 27.74; H, 5.54; N, 6.39; Zn, 15.05%.

2.2.3. [Cd(OAc)2(2Ampic)2] (3)

Complex 3 was prepared by mixing a 10 mL aqueous solution of Cd(OAc)2 (23.0 mg, 0.1 mmol) with a 10 mL ethanolic solution of 2Ampic (21.6 mg, 0.2 mmol). C16H22Cd N4O4: Yield: 81%; Anal. Calc.: C, 43.01; H, 4.96; Cd, 25.16; N, 12.54%. Found: C, 42.72; H, 4.85; Cd, 25.06; N, 12.33%

2.3. Crystal Structure Determination

The crystal structure determinations for complexes 1–3 are described in method S1 and Table S1 (Supporting Materials) [74,75].

2.4. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

The Crystal Explorer Ver. 3.1 [76] program was used to construct the Hirshfeld surfaces and determine the 2D fingerprint plot for the studied complexes [77,78].

2.5. DFT Calculations

All DFT computations were performed using Gaussian 09 software [79]. Natural charge calculations [80] were performed at the MPW1PW91 [81] level combined with cc-PVTZ and cc-PVTZ-PP basis sets for nonmetal and metal atoms, respectively [82,83]. Atoms in molecules (AIM) parameters were calculated [84] using the Multiwfn program [85].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. X-ray Structure Description

3.1.1. Structure of [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2]; 1

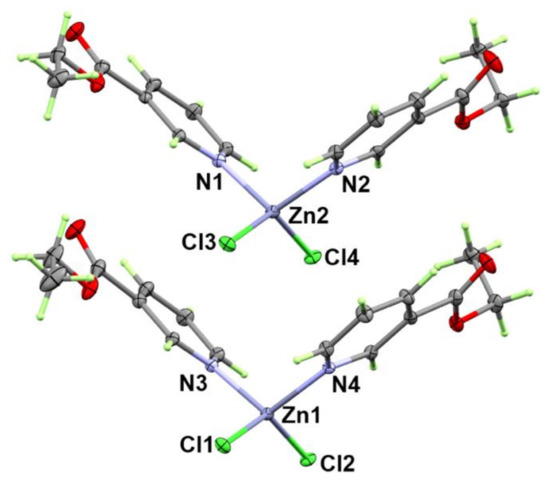

The X-ray structure of the heteroleptic Zn(II) complex 1 is shown in Figure 2. The complex crystallized in the monoclinic crystal system and P21/c space group. The unit cell parameters were a = 14.1940(9) Å, b = 19.8380(11) Å, c = 14.3957(9), Å and β = 111.432(3)°. The view of the unit cell of 1 along the ac plane is shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Materials). The asymmetric unit comprised two [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2] formula units. The Zn(II) was coordinated with two EtNic molecules via the ring N-atom and two chloride ions. The Zn–N distances were marginally different (2.057(3)–2.061(3) Å), and the same is true for the Zn–Cl bonds (2.221(1)–2.226(1) Å). The N-Zn-N and Cl-Zn-Cl angles were in the ranges of 110.68(13)–110.84(13)° and 129.13(4)–129.46(4)°, respectively (Table 1). Hence, Zn(II) was tetra-coordinated with a distorted tetrahedral coordination environment, which is expected for a small size metal ion with a spherical d10 configuration.

Figure 2.

The asymmetric unit of the [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2] complex.

Table 1.

The important geometric parameters (Å, °) in complex 1.

The supramolecular structure of 1 is controlled by weak non-classical C-H···O interactions between the protons from the CH2 group in the ester moiety of one molecule with the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group in the ester moiety of another molecule. As can be seen from the packing scheme shown in Figure 3, the C7-H7A···O5 and C31-H31B···O4 interactions form a wave-like chain along the a-direction. The hydrogen bond parameters are depicted in Table S2 (Supporting Materials). The H7A···O5 and H31B···O4 distances were 2.58 and 2.55 Å, respectively. In addition, the corresponding donor–acceptor distances were 3.076(5) and 3.055(6) Å, respectively.

Figure 3.

Wave-like packing of 1 along the ab plane.

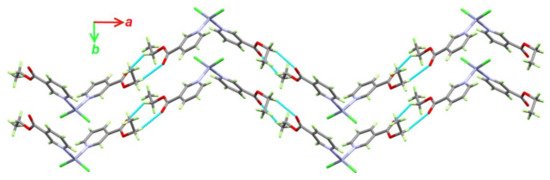

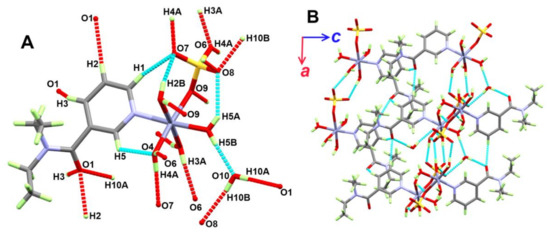

3.1.2. Structure of [Zn(DiEtNA)(H2O)4(SO4)]·H2O; 2

The X-ray structure of 2 also revealed a heteroleptic Zn(II) complex, but in this case, the Zn(II) was hexa-coordinated (Figure 4). This complex crystallized in the orthorhombic crystal system and P212121 space group. The unit cell parameters were a = 7.6541(3) Å, b = 9.9244(4), Å and c = 23.1526(10) Å. The asymmetric unit comprised one [Zn(DiEtNA)(H2O)4(SO4)]·H2O formula unit. The view of the unit cell of 2 along the ac plane is shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Materials). In this complex, the Zn(II) was hexa-coordinated to only one bulky DiEtNA organic ligand; five small ligands, which were the four water molecules; and one sulfate anion, all acting as monodentate ligands. The structure of this complex comprised one crystal water, which was not a part of the coordination sphere but contributed significantly to the molecular packing of this complex. Among the five Zn-O interactions, the longest zinc-to-oxygen distance was Zn1-O9 (2.1284(10) Å), which occurred with the weakly coordinated sulfate anion. By contrast, the Zn1-O4 bond, which occurred between the Zn(II) ion and the water molecule trans to the Zn1-O9 bond, was the shortest (2.0657(11) Å). Additionally, the distance between the Zn(II) and the heterocyclic nitrogen of DiEtNA was 2.1388(12) Å. In addition, the bond angles inside the coordination sphere deviated from the ideal values of 180 and 90° for the trans and cis bonds, respectively (Table 2). The angles between the trans bonds ranged from 174.37(4)° (O4-Zn1-O9) to 177.53(5)° (O3-Zn1-O2), while the angles between the cis bonds were in the range of 83.99(4)° (O5-Zn1-O9) to 92.91(4)° (O4-Zn1-N1). The distance between the Zn(II) ion and the oxygen of the crystal water was 4.325(3) Å, which is too long to be a bond. Hence, the fifth water molecule was a part of the outer sphere.

Figure 4.

The asymmetric unit of [Zn(DiEtNA)(H2O)4(SO4)]·H2O (2). The disorder of one of the ethyl groups was refined as Part 1 (59.7%) and Part 2 (40.3%).

Table 2.

The important geometric parameters (Å, °) in complex 2.

In contrast to 1, the supramolecular structure of 2 was controlled by several strong O-H···O hydrogen bonds (Table 3). The coordinated and crystal water molecules acted as hydrogen bond donors, while the oxygen atoms from the amide group, the coordinated sulfate ion, and the crystal water were the hydrogen bond acceptors. In addition, the structure was found to be stabilized by some intramolecular O···H interactions. The intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds are shown in Figure 5A as turquoise and red dotted lines, respectively, while the 3D packing structure is shown in Figure 5B.

Table 3.

Hydrogen bond parameters (Å, °) in 2.

Figure 5.

Intra- and intermolecular contacts (A) through O-H···O hydrogen bonds and packing of 2 along the ac plane (B).

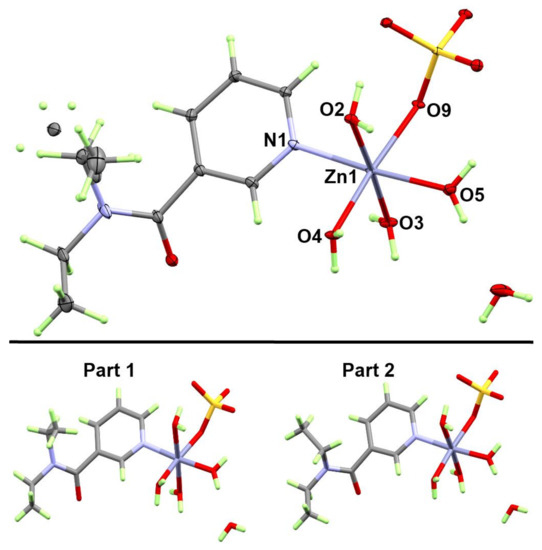

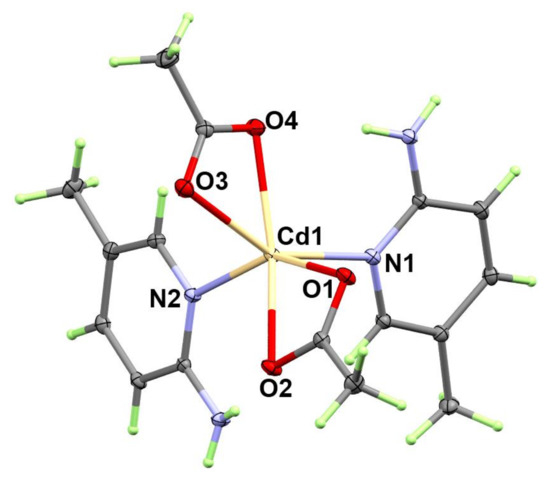

3.1.3. Structure of [Cd(OAc)2(2Ampic)2]; 3

The X-ray structure of the [Cd(OAc)2(2Ampic)2] complex 3 is shown in Figure 6. This compound crystallized in the monoclinic crystal system and P21/n space group. The unit cell parameters were a = 8.4025(4) Å, b = 17.1565(15) Å, c = 12.9867(9) Å, and β = 94.661(3)°. The view of the unit cell of 3 along the bc plane is shown in Figure S3 (Supporting Materials). In this complex, the large Cd(II) ion was hexa-coordinated with the heterocyclic nitrogen atom of the two bulky 2Ampic molecules, which acted as the monodentate ligand. In addition, the Cd(II) was coordinated with four oxygen atoms from two bidentate acetate ions. The Cd1-N1 and Cd1-N2 distances were 2.3210(8) and 2.2723(8) Å, respectively, while the N1-Cd1-N2 angle was 93.39(3)°, indicating that the two pyridine ligand units are located cis to one another. On the other hand, the acetate group of the lower atom numbering had different Cd-to-O distances. The Cd1-O1 and Cd1-O2 distances were 2.2993(7) and 2.4484(7) Å, respectively. The other acetate group had two almost equidistant Cd-O bonds, for which the Cd1-O3 and Cd1-O4 distances were 2.3813(8) and 2.3356(7) Å, respectively. The bite angles of the two acetate groups were 55.08(2) and 55.67(3)°, respectively (Table 4). Because of the small bite angles of the two acetate groups, one could consider that the two acetate ions are also located cis to each other.

Figure 6.

The asymmetric unit of [Cd(OAc)2(2Ampic)2] (3).

Table 4.

The important geometric parameters (Å, °) in complex 3.

The supramolecular structure of 3 is controlled by a complicated set of classical (N-H···O) and non-classical (C-H···O) hydrogen bonding interactions (Table 5). The molecular structure of 3 is stabilized by the intramolecular N3-H3A···O4 and N4-H4D···O2 hydrogen bonds, which are shown in Figure 7A as turquoise dotted lines, while the intermolecular hydrogen bonds are shown in the same figure as red dotted lines. The 3D packing structure of complex 3 is shown along the ab plane in Figure 7B.

Table 5.

Hydrogen bond parameters (Å, °) in 3.

Figure 7.

The intra- and intermolecular contacts (A) and packing scheme via O-H···O hydrogen bonds along ab plane (B) of 3.

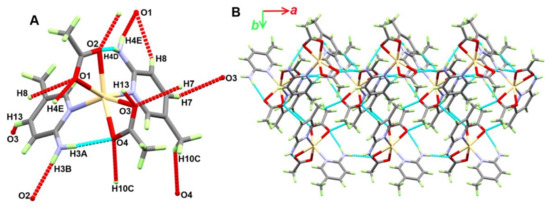

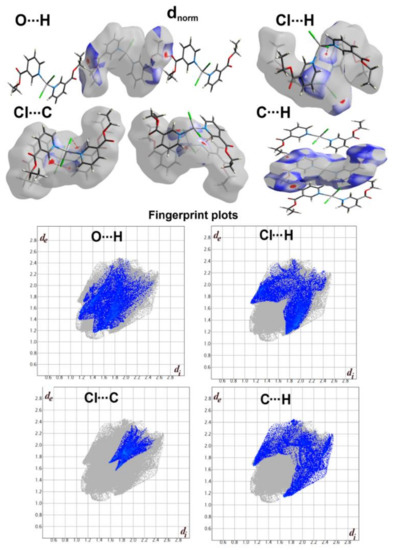

3.2. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

The use of Hirshfeld surface analysis to describe the intermolecular interactions that affect the molecule packing in crystals has been shown to be very effective [86]. In this context, various contacts in the crystal structures of the investigated complexes were quantitatively evaluated using Hirshfeld calculations. For complex 1, the single-crystal X-ray structure showed the presence of two [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2] units per asymmetric formula (Zn1 and Zn2 units), so there are two sets of results for this crystal structure (Table 6). It is clear that the types of interactions, as well as their percentages in both units, were nearly identical, and the most predominant contacts in both units were H···H, O···H, Cl···H, C···H, and Cl···C (Table 6). Their percentages were 43.8%, 15.6%, 13.6%, 10.6%, and 6.3%, respectively, for the Zn1 unit and 44.0%, 15.5%, 13.8%, 10.3%, and 6.3%, respectively, for the Zn2 unit.

Table 6.

Different contacts and their percentages in complex 1.

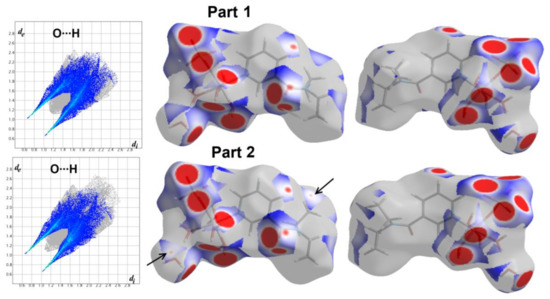

The decomposed dnorm maps and fingerprint plots strongly show that O···H, Cl···H, Cl···C, and C···H are the most important interactions that govern the molecular packing of 1. The appearance of these contacts as red spots in the dnorm maps and relatively sharp spikes in the fingerprint plots (Figure 8) reveal the importance of these short contacts in the crystal stability of this complex. The contact distances of all the short contacts are listed in Table 7.

Figure 8.

The fingerprint plots (left) and dnorm maps (right) of the short contacts in complex 1.

Table 7.

The distances of all short contacts in 1.

For complex 2, there was disorder in one of the two ethyl groups attached to the amide moiety. As a result, there were two disordered parts, which differed in the orientation of this ethyl group (Figure 4). The fingerprint plot of the two parts was dominated by H···H, O···H, and C···H contacts. The contributions of these contacts to the overall surface were 50.2%, 41.1%, and 7.0%, respectively, for part 1 and 50.2%, 41.2%, and 7.1% for part 2. The other interactions had a negligible effect on the Hirshfeld surface in both forms (Figure S4; Supporting Materials). The dnorm maps of the two parts showed that the most important contacts were the polar O···H interactions, which appeared as large intense red spots and sharp spikes in the fingerprint plot, indicating short contacts (Figure 9). The distances of these short contacts are listed in Table 8. The main difference between the results of the two disordered parts is the presence of two extra red spots corresponding to the O10···H31C interaction (2.558 Å) only for part 2 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The fingerprint plots and dnorm maps related to O···H contacts in 2. The solid black arrows refer to the extra O10…H31C interactions that exist in part 2.

Table 8.

The short O···H contacts in complex 2.

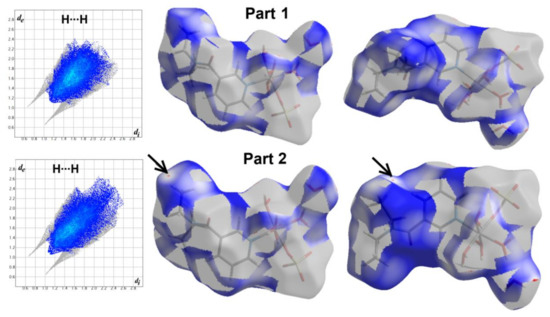

There was another difference between the two disordered parts of complex 2. In part 2, there was one short H···H contact (H14B···H31C) which was not found in part 1. The interaction distance of this contact was 2.167 Å. The steep spikes that occurred in the fingerprint plot of part 2 and the red spot in the corresponding dnorm map were additional evidence of the importance of the H···H contacts in part 2 of complex 2 (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The fingerprint plots and dnorm maps related to H···H contacts in 2. The solid black arrows refer to the extra H14B···H31C interactions that exist in part 2.

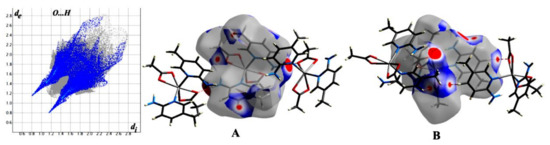

For complex 3, the H···H, O···H, and H···C contacts dominated the crystal structure, with 57.1%, 16.9%, and 15.2% contributions, respectively. In addition, there were some minor contributions from N···H, C···C, N···C, and O···C interactions (Figure S5; Supporting Materials). The strong polar O···H interactions appeared as large intense red spots on the dnorm map and sharp spikes in the fingerprint plot (Figure 11). The most important O···H interactions occurred between oxygen atoms of the acetate moiety as the hydrogen bond acceptor, with the N-H protons of the amino group as the hydrogen bond donor (Figure 11A). The corresponding O···H contact distances were 1.933 Å (N4-H4E···O1) and 2.005 Å (N3-H3B···O2). Other O···H interactions, such as C7-H7···O3 (2.458 Å), C8-H8···O1 (2.472 Å), C13-H13···O3 (2.473 Å), and C10-H10C···O4 (2.474 Å) occurred with the C-H protons of the picoline moiety as the hydrogen bond donor (Figure 11B).

Figure 11.

The FP plot and dnorm maps showing the different N-H···O (A) and C-H···O (B) interactions in complex 3.

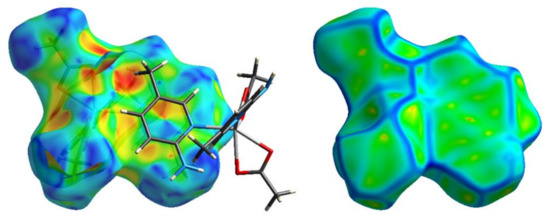

In addition, it is important to note the presence of complementary red/blue triangles in the shape index map and the green flat area in the curvedness map. Both indicated the presence of π-π stacking interactions between the nearly parallel stacked pyridine rings (Figure 12). The C5···C7 (3.507 Å) is the shortest distance between the stacked pyridine rings. This distance was slightly longer than twice that of the vdWs radii (3.40 Å) of the carbon atoms, indicating a relatively weak π-π stacking interaction.

Figure 12.

Red/blue triangles in shape index (left) and flat green surface in curvedness (right) revealed the presence of π-π stacking interaction in 3.

3.3. Natural Charge Distribution

In metal–organic complexes, the interaction between a metal ion and ligand groups causes considerable changes in their charges as a result of the partial electron density transfer from the ligand (Lewis base) to the metal ion (Lewis acid). The results of their natural charges are listed in Table 9. The calculated natural charges at the central metal ion were 0.8775, 1.0559, and 1.2193 for complexes 1–3, respectively. All values were notably different from the formal charge of +2 for the isolated metal ion. In complex 1, the Cl− and EtNic ligands transferred 0.406 e and 0.155 e (average values), respectively. In the case of complex 2, the organic ligand (DiEtNA) and the weakly coordinating anion (SO42−) transferred lower electron densities of 0.131 and 0.271 e, respectively, to the Zn(II) compared with 1. In addition, the four coordinated water molecules transferred a net of 0.5421 e to the Zn(II) ion. In complex 3, the amounts of electrons transferred from each 2Ampic and OAc− fragments were 0.1242 and 0.2661 e, respectively. Hence, the net electron densities transferred from the ligand groups to the central metal ion were 1.1226, 0.9441, and 0.78071 e for complexes 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The highest value was found in complex 1, probably because of the presence of the strongly coordinating Cl− anion.

Table 9.

Charge analysis in complexes 1, 2, and 3.

3.4. The Atoms in Molecules (AIM) Studies

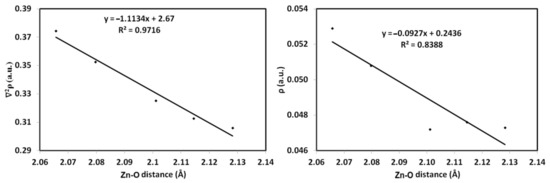

According to the AIM approach [87,88,89,90], each bond has a bond path and a bond critical point [91]. We calculated the AIM parameters of each coordinate bond at its BCP (Table S3 (Supplementary data)). According to the literature, the degree of the electron density function (ρ) at BCP can express the strength of the bond [91]. It is clear that all bonds hadan electron density (ρ) smaller than 0.1 a.u., and the Laplacian (∇2ρ) had positive values; this clearly revealed the predominant closed-shell character of the Zn-Cl, Zn-N, Zn-O, Cd-O, and Cd-N bonds, which agrees with their spherical coordination environment, indicating that no specific coordination is preferred and only size determines the number of ligands [92,93,94]. In addition, large ρ and ∇2ρ values indicate that the structure has a high level of local stability [95,96]. As clearly seen in Table S3 (Supplementary data), these parameters were higher for the Zn-N interactions in complex 1 than those in 2, which agrees with the shorter Zn-N bonds in the former compared with the latter [97]. Similarly, there are clear inverse correlations between these parameters and Zn-O distances (Figure 13). On the other hand, the quantities of total energy density (H(r)) [98] were near zero, indicating very well that all coordinate bonds have low covalent characters.

Figure 13.

Correlation between the AIM parameters and Zn-O distances.

4. Conclusions

The molecular and supramolecular structures of three heteroleptic complexes of Zn(II) and Cd(II) metal ions with pyridine-type ligands were discussed. The compounds [Zn(EtNic)2Cl2]; 1, [Zn(DiEtNA)(H2O)4(SO4)]·H2O; 2, and [Cd(OAc)2(2Ampic)2]; 3 were synthesized by the self-assembly of the corresponding metal(II) salt and the functional pyridine ligand in water–ethanol as solvents. Their single-crystal X-ray structures were determined and analyzed using Hirshfeld analysis. It was found that the Zn(II) was tetra-coordinated in 1 with a distorted tetrahedral coordination environment, while the Zn(II) and Cd(II) were hexa-coordinated in complexes 2 and 3, respectively. In all complexes, the pyridine ligands were monodentate N-donors via the heterocyclic nitrogen atom. Hirshfeld analysis was used to elucidate the different intermolecular interactions that govern the molecular packing in the studied complexes. DFT calculations of the natural charges predicted decreases in the Zn(II) and Cd(II) natural charges as a consequence of the interactions with the ligand groups. In addition, atoms in molecules (AIM) parameters were used to investigate the nature of the Zn-Cl, Zn-N, Zn-O, Cd-O, and Cd-N coordination interactions. Hence, no specific coordination is preferred, and only size determines the number of ligands around the metal ion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst12050590/s1, Table S1: Crystallographic details of complexes 1–3. Table S2: Hydrogen bond parameters (Å, °) in 1. Table S3: AIM topology parameters (a.u.) at bond critical points (BCPs) as well as the bond distances of the coordinated bonds in complexes 1, 2, and 3. Figure S1: View of the unit cell of 1 along the ac plane. Figure S2: View of the unit cell of 2 along the ac plane. Figure S3: View of the unit cell of 3 along the bc plane. Figure S4: Distribution of all contacts in complexes 1 and 2. Figure S5: Intermolecular interactions in 3 and their percentages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.S. and M.A.M.A.-Y.; methodology, E.M.F., D.H., J.H.A., A.M.A.B., T.S.K. and A.B.; software, S.M.S., M.S.A., A.M.A.B. and A.B.; formal analysis, E.M.F., D.H., A.M.A.B. and M.S.A.; investigation, S.M.S., A.M.A.B., T.S.K., E.M.F. and D.H.; resources, M.S.A., M.A.M.A.-Y. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.S., E.M.F., M.A.M.A.-Y., A.M.A.B. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, S.M.S., E.M.F., M.A.M.A.-Y., A.M.A.B. and A.B.; supervision, S.M.S. and M.A.M.A.-Y.; project administration, M.S.A., A.B., S.M.S. and M.A.M.A.-Y.; funding acquisition, M.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R86), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R86), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Férey, G. Hybrid porous solids: Past, present, future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L. Metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003, 32, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.-L.; Xiang, S.-C.; Qian, G.-D. Metal−Organic Frameworks with Functional Pores for Recognition of Small Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batten, S.R.; Robson, R. Interpenetrating Nets: Ordered, Periodic Entanglement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1460–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaworotko, M.J. Designer pores made easy. Nature 2008, 451, 410–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, S.M.; Halder, G.J.; Chapman, K.W.; Duriska, M.B.; Moubaraki, B.; Murray, K.S.; Kepert, C.J. Guest tunable structure and spin crossover properties in a nanoporous coordination framework material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12106–12108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, D.-F.; Wang, Z.-M.; Gao, S. Framework-structured weak ferromagnets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3157–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-R.; Sculley, J.; Zhou, H.-C. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Separations. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 869–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspoch, D.; Ruiz-Molina, D.; Veciana, J. Old materials with new tricks: Multifunctional open-framework materials. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 770–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-D.; Du, M.; Mak, T.C.W. Controlled generation of heterochiral or homochiral coordination polymer: Helical conformational polymorphs and argentophilicity-induced spontaneous resolution. Chem. Commun. 2005, 35, 4417–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.-Q.; Sakurai, H.; Xu, Q. Preparation, adsorption properties, and catalytic activity of 3D porous metal-organic frameworks composed of cubic building blocks and alkali-metal ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2542–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.-S.; Leng, J.-D.; Liu, J.-L.; Meng, Z.-S.; Tong, M.-L. Polynuclear and polymeric gadolinium acetate derivatives with large magnetocaloric effect. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-Y.; Jin, Z.; Su, H.-M.; Jing, X.-F.; Sun, F.-X.; Zhu, G.-S. Targeted synthesis of a 2D ordered porous organic framework for drug release. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6389–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, S.; Uemura, K. Dynamic porous properties of coordination polymers inspired by hydrogen bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.W. Molecular Tectonics: From Simple Tectons to Complex Molecular Networks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Zhao, X.-J.; Guo, J.-H.; Batten, S.R. Direction of topological isomers of silver(i) coordination polymers induced by solvent, and selective anion-exchange of a class of PtS-type host frameworks. Chem. Commun. 2005, 38, 4836–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-F.; Hong, M.-C.; Wu, X.-T. Lanthanide–transition metal coordination polymers based on multiple N- and O-donor ligands. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockwig, N.W.; Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Reticular Chemistry: Occurrence and Taxonomy of Nets and Grammar for the Design of Frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiong, R.-G.; Huang, S.-D. 3D Framework Containing Cu4Br4 Cubane as Connecting Node with Strong Ferroelectricity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10468–10469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-P.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Lin, J.-B.; Chen, X.-M. Metal azolate frameworks: From crystal engineering to functional materials. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1001–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, R.-F.; Xing, S.-K.; Liu, X.-M.; Hu, T.-L.; Bu, X.-H. A Highly Selective On/Off Fluorescence Sensor for Cadmium(II). Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 10041–10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, G.-G.; Li, H.-B.; Cao, H.-T.; Zhu, D.-X.; Li, P.; Su, Z.-M.; Liao, Y. Reversible piezochromic behavior of two new cationic iridium(iii) complexes. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2000–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-R.; Kuppier, R.J.; Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1477–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.-X.; Xiang, S.-C.; Zhang, W.-W.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Wang, L.; Bai, J.-F.; Chen, B.-L. A new MOF-505 analog exhibiting high acetylene storage. Chem. Commun. 2009, 48, 7551–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-Z.; Li, M.-A.; Li, Z.; Hou, J.-Z.; Huang, X.-C.; Li, D. Concomitant and controllable chiral/racemic polymorphs: From achirality to isotactic, syndiotactic, and heterotactic chirality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6371–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Vagnerova, K.; Czernek, J.; Lhotak, P. Flip–flop Motion of Circular Hydrogen Bond Array in Thiacalix [4]arene. Supramol. Chem. 2006, 18, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Khan, E.; Shimpi, M.R.; Tandon, P.; Sinha, K.; Velaga, S.P. Molecular structure and hydrogen bond interactions of a paracetamol–4,4′-bipyridine cocrystal studied using a vibrational spectroscopic and quantum chemical approach. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpetuo, G.J.; Janczak, J. Supramolecular architectures in crystals of melamine and aromatic carboxylic acids. J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 891, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roesky, H.W.; Andruh, M. The interplay of coordinative, hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking interactions in sustaining supramolecular solid-state architectures. A study case of bis(4-pyridyl)- and bis(4-pyridyl-N-oxide) tectons. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 236, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.L.; Li, Z.H.; Chen, J.S.; Wang, X.P.; Sun, D. Solution and Mechanochemical Syntheses of Two Novel Cocrystals: Ligand Length Modulated Interpenetration of Hydrogen-Bonded 2D 63-hcb Networks Based on a Robust Trimeric Heterosynthon. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Liu, F.J.; Huang, R.B.; Zheng, L.S. Three guest-dependent nitrate–water aggregations encapsulated in silver(i)–bipyridine supramolecular frameworks. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 7872–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, Y.H.; Hao, H.J.; Liu, F.J.; Wen, Y.M.; Huang, R.B.; Zheng, L.S. Solvent-Controlled Rare Case of a Triple Helical Molecular Braid Assembled from Proton-Transferred Sebacic Acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 3323–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, W.; Ouari, K.; Bendia, S.; Bourzami, R.; Ali, M.A. Crystal structure, spectroscopic studies, DFT calculations, cyclic voltammetry and biological activity of a copper (II) Schiff base complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1203, 127313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadeo, E.; Dubois, L.; Latour, J.-M. Trinuclear copper complexes as biological mimics: Ligand designs and reactivities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 374, 345–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.-Q.; Wu, X.-H.; Ren, N.; Zhang, J.-J.; Geng, L.-N. Construction of two novel lanthanide complexes supported by 2-bromine-5-methoxybenzoate and 2,2′-bipyridine: Syntheses, crystal structures and thermodynamic properties. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2017, 113, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, O.; Das, S.K. Supramolecular inorganic chemistry leading to functional materials. J. Chem. Sci. 2020, 132, 46–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Zheng, X.J.; Yuan, D.Q.; Ablet, A.; Jin, L.P. In Situ Formed White-Light-Emitting Lanthanide–Zinc–Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 1201–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, K.K.; Allen, C.A.; Cohen, S.M. Photochemical Activation of a Metal–Organic Framework to Reveal Functionality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9730–9733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Jiang, F.L.; Chen, L.; Yan, C.F.; Wu, M.Y.; Hong, M.C. Exceptionally high H2 storage by a metal–organic polyhedral framework. Chem. Commun. 2009, 9, 5296–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Qi, D.D.; Xie, Z.; Cao, W.; Wang, K.; Shang, H.; Jiang, J.Z. Synthesis and decarboxylative Wittig reaction of difluoromethylene phosphobetaine. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachuri, Y.; Parmar, B.; Bisht, K.K.; Suresh, E. Solvothermal self-assembly of Cd2+ coordination polymers with supramolecular networks involving N-donor ligands and aromatic dicarboxylates: Synthesis, crystal structure and photoluminescence studies. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 3623–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.G.; Morsali, A.; Bigdeli, F. A New Metal–Organic ZnII Supramolecular Assembled via Hydrogen Bonds and N···N Interactions as a New Precursor for Preparation Zinc(II) Oxide Nanoparticles, Thermal, Spectroscopic and Structural Studies. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2011, 21, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, N.H.C.; Viavattene, R.L.; Eksteen, R.; Wong, W.S.; Davies, G.; Karger, B.L. Use of metal ions for selective separations in high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1978, 149, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Page, J.N.; Lindner, W.; Davies, G.; Seitz, D.E.; Karger, B.L. Resolution of the optical isomers of dansyl amino acids by reversed phase liquid chromatography with optically active metal chelate additives. Anal. Chem. 1979, 51, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, W. HPLC-Enantiomerentrennung an gebundenen chiralen Phasen. Nat. Schaften 1980, 67, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, N.; Sirajuddin, M.; Uddin, N.; Ullah, H.; Ali, S.; Tariq, M.; Tirmizi, S.A.; Khan, A.R. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, biological screenings, DNA binding study and POM analyses of transition metal carboxylates. Spectrochim. Acta A 2015, 140, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, B.V.; Hingorani, M.S. Characteristic IR and Electronic Spectral Studies on Novel Mixed Ligand Complexes of Copper(II) with Thiosemicarbazones and Heterocyclic Bases. Synth. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 1990, 20, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, M.; Matsushima, S.; Noro, A.; Matsushita, Y. Mechanical Property Enhancement of ABA Block Copolymer-Based Elastomers by Incorporating Transient Cross-Links into Soft Middle Block. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.N.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.C. Preparation of 4-vinylpyridine (4VP) resin and its adsorption performance for heavy metal ions. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4226–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdie, M.P.; Belfiore, L.A. Spectroscopic analysis of transition-metal coordination complexes based on poly(4-vinylpyridine) and dichlorotricarbonylruthenium(II). Polymer 1999, 40, 2889–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oconnell, E.M.; Yang, C.Z.; Root, T.W.; Cooper, S.L. Spectroscopic studies of pyridine-containing polyurethanes blended with metal acetates. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 6002–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noro, A.; Matsushima, S.; He, X.D.; Hayashi, M.; Matsushita, Y. Thermoreversible Supramolecular Polymer Gels via Metal-Ligand Coordination in an Ionic Liquid. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 8304–8310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Bulit, P.; Garza-Ortiz, A.; Mijangos, E.; Barron-Sosa, L.; Sanchez-Bartez, F.; Gracia-Mora, I.; Flores-Parra, A.; Contreras, R.; Reedijk, J.; Barba-Behrens, N. 2,6-Bis(2,6-diethylphenyliminomethyl)pyridine coordination compounds with cobalt(II), nickel(II), copper(II), and zinc(II): Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, X-ray study and in vitro cytotoxicity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 142, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrat, P.; Gros, P.C.; Fort, Y. Solid phase synthesis of pyridine-based derivatives from a 2-chloro-5-bromopyridine scaffold. J. Comb. Chem. 2005, 7, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, M.; Mongin, F. Pyridine elaboration through organometallic intermediates: Regiochemical control and completeness. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asath, R.M.; Premkumar, R.; Mathavan, T.; Benial, A.M.F. Structural, spectroscopic and molecular docking studies on 2-amino-3-chloro-5-trifluoromethyl pyridine: A potential bioactive agent. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 175, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.P.; Mohan, S. Vibrational spectra and normal co-ordinate analysis of 2-aminopyridine and 2-amino picoline. Spectrochim Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2006, 64, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machura, B.; Nawrot, I.; Michalik, K.B.; Machura, I.; Nawrot, K. Michalik, Novel thiocyanate complexes of cadmium(II)-Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, X-ray studies and DFT calculations. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhu, M.L.; Yuan, C.X.; Feng, S.S.; Lu, L.P.; Wang, Q.M. A Molecular Helix: Self-Assembly of Coordination Polymers from d10 Metal Ions and 1,10-Phenanthroline-5,6-dione (pdon) with the Bridges of SCN− and Cl−Anions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Tong, M.L.; Chen, X.M. Hydrothermal synthesis and crystal structures of three-dimensional coordination frameworks constructed with mixed terephthalate (tp) and 4,4′-bipyridine (4,4′-bipy) ligands: [M(tp)(4,4′-bipy)] (M = CoII, CdII or ZnII). J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000, 20, 3669–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.M.L.; Chui, S.S.Y.; Shek, L.Y.; Lin, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Wen, G.H.; Williams, I.D. Solvothermal Synthesis of a Stable Coordination Polymer with Copper-I−Copper-II Dimer Units: [Cu4{1,4-C6H4(COO)2}3(4,4‘-bipy)2]n. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6293–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Feng, S.H.; Sun, Y.; Hua, J. Novel Coordination Polymers with Mixed Ligands and Orientated Enantiomers. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 5312–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, S.; Mukherjee, P.S.; Ribas, J.; Drew, M.G.B.; Ribas, J.; Chaudhuri, N.R. Syntheses of Two New 1D and 3D Networks of Cu(II) and Co(II) Using Malonate and Urotropine as Bridging Ligands: Crystal Structures and Magnetic Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourosh, P.; Bulhac, I.; Covaci, O.; Zubareva, V.; Mitina, T. Iron(II) Bis-α-Benzyldioximate Complexes with 3- and 4-Pyridine Hemiacetals as Axial Ligands: Synthesis, Structure, and Physicochemical Properties. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2018, 44, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechitskaya, E.D.; Kuratieva, N.V.; Lider, E.V.; Eremina, J.A.; Klyushova, L.S.; Eltsov, I.V.; Kostin, G.A. Tuning of cytotoxic activity by bio-mimetic ligands in ruthenium nitrosyl complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1219, 128565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Sun, X.; Wan, D.; Chen, J.; Li, B. Chloridobis(dimethylglyoximatok2N,N’)(ethyl pyridine-3-carboxylatekN) cobalt(III). Acta Cryst. E 2012, 68, m20. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, T.; Köse, D.A.; Avci, G.A.; Þahin, O.; Akkurt, F. Novel coordination compounds: Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) cations with acesulfame/N,N-diethylnicotinamide ligands. J. Coord. Chem. 2019, 72, 3502–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigoli, F.; Braibant, A.; Pellinghelli, M.A.; Tiripicchio, A. The Crystal and Molecular Structure of Diaquobis-(N,N-diethylnicotinamide)-diisothiocyanatozinc. Acta Cryst. B 1973, 29, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasova, T.G.; Pervukhina, N.V.; Kuratieva, N.V.; Cherkasova, E.V.; Isakova, I.V.; Mizinkina, Y.A.; Tatarinova, E.S. Mixed-Ligand Cobalt(II) and Nickel(II) Complexes with N,N,-Diethylpyridine-3-carboxamide: Synthesis and Crystal Structure. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 65, 1160–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maa, Z.; Sutradhar, M.; Gurbanov, A.V.; Maharramov, A.M.; Aliyeva, R.A.; Aliyeva, F.S.; Bahmanova, F.N.; Mardanova, V.I.; Chyragov, F.M.; Mahmudov, K.T. CoII, NiII and UO2II complexes with β-diketones and their arylhydrazone derivatives: Synthesis, structure and catalytic activity in Henry reaction. Polyhedron 2015, 101, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, M.; Emelina, A.; Kiskin, M.; Sidorov, A.; Aleksandrov, G.; Bogomyakov, A.; Dobrokhotova, Z.; Novotortsev, V.; Eremenko, I. Coordination polymer [Li2Co2(Piv)6(l-L)2]n (L = 2-amino-5-methylpyridine) as a new molecular precursor for LiCoO2 cathode material. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 3628–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, G.-S.; ZHANGJ, H.-L. Synthesis, Characterization And Crystal Structure of A Polymeric Silver(I) Complex With Cytotoxic Property. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2015, 60, 2677–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pakhmutova, E.V.; Malkov, A.E.; Mikhailova, T.B.; Sidorov, A.A.; Fomina, I.G.; Aleksandrov, G.G.; Novotortsev, V.M.; Ikorskii, V.N.; Eremenkoa, I.L. Formation of bi and tetranuclear cobalt(II) trimethylacetate complexes with 2amino5methylpyridine and 2,6diaminopyridine. Russ. Chem. Bullet 2003, 52, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS, Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data; ScienceOpen: Burlington, VT, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, M.A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshfeld, F.L. Bonded-Atom Fragments for Describing Molecular Charge Densities. Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 44, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Davis, R.E.; Shimoni, L.; Chang, N.-L. Patterns in Hydrogen Bonding: Functionality and Graph Set Analysis in Crystals. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1555–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. GAUSSIAN 09; Revision A02; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glendening, E.D.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Weinhold, F. NBO, version 3.1; CI; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Exchange functionals with improved long-range behavior and adiabatic connection methods without adjustable parameters: The mPW and mPW1PW models. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, D. The role of databases in support of computational chemistry calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 1996, 17, 1571–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, K.L.; Didier, B.T.; Elsethagen, T.; Sun, L.; Gurumoorthi, V.; Chase, J.; Li, J.; Windus, T.L. Basis set exchange: A community database for computational sciences. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comp. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.J.; Spackman, M.A.; Mitchell, A.S. Novel tools for visualizing and exploring intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. Acta Cryst. B 2004, 60, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, C.F.; Hernandez-Trujillo, J.; Tang, T.-H.; Bader, R.F.W. Hydrogen–Hydrogen Bonding: A Stabilizing Interaction in Molecules and Crystals. Chem. Eur. J. 2003, 9, 1940–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, S.J.; Pfitzner, A.; Zabel, M.; Dubis, A.T.; Palusiak, M. Intramolecular H···H Interactions for the Crystal Structures of [4-((E)-But-1-enyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenyl]pyridine-3-carboxylate and [4-((E)-Pent-1-enyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenyl]pyridine-3-carboxylate; DFT Calculations on Modeled Styrene Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 1831–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, C.F.; Castillo, N.; Boyd, R.J. Characterization of a Closed-Shell Fluorine−Fluorine Bonding Interaction in Aromatic Compounds on the Basis of the Electron Density. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 3669–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendás, A.M.; Francisco, E.; Blanco, M.A.; Gatti, C. Bond Paths as Privileged Exchange Channels. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 9362–9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.G.; Pereira, F.S.; de Araujo, R.C.M.C.; Ramos, M.N. The hdyrogen bond strength: New proposals to evaluate the intermolecular interaction using DFT calculations and the AIM theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 427, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, R.F.W.; Essén, H. The characterization of atomic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 80, 1943–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.G.A.; Bader, R.F.W. Identifying and Analyzing Intermolecular Bonding Interactions in van der Waals Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 10892–10911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrov, M.F.; Popova, G.V.; Tsirelson, V.G. A topological analysis of electron density and chemical bonding in cyclophosphazenes PnNnX2n (X = H, F, Cl; N = 2, 3, 4). Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2006, 80, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, C. Chemical bonding in crystals: New directions. Z. Für Krist.-Cryst. Mater. 2005, 220, 399–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G.V.; Downs, R.T.; Cox, D.F.; Ross, N.L.; Boisen, M.B.; Rosso, K.M. Shared and Closed-Shell O−O Interactions in Silicates. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 3693–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, I. Polar covalent bonds: An AIM analysis of S,O bonds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 2640–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, D.; Kraka, E. Chemical Bonds without Bonding Electron Density—Does the Difference Electron-Density Analysis Suffice for a Description of the Chemical Bond? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1984, 23, 627–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).