Abstract

Plasmon-driven surface catalysis has attracted significant interest due to its capacity to integrate near-field enhancement and hot-carrier effects at the nanoscale synergistically. In this work, nanoporous Au-Ag shells (NPASs) were prepared via a galvanic replacement process. The coupling of p-nitrothiophenol (PNTP) to form 4,4′-dimercaptoazobenzene (DMAB) was used as a model reaction to evaluate plasmonic catalytic kinetics on three substrates, including NPASs, Au nanoparticles (Au NPs), and Ag nanoparticles (Ag NPs), under 532 and 633 nm excitation. TEM, XRD, EDX, and HAADF-STEM analyses confirmed that the NPASs exhibited a hollow nanoporous morphology and a homogeneous Au-Ag alloy structure. UV-Vis extinction spectroscopy revealed a broadband response in the visible region, with a main peak at ~683 nm and a shoulder at ~542 nm. Based on in situ time-resolved SERS monitoring and first-order kinetic fitting, all three substrates showed faster conversion rates under 532 nm excitation. To quantitatively assess wavelength selectivity, a wavelength-dependent factor (R = k532/k633) was introduced. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that Au NPs exhibited the most significant R value (15.0), followed by Ag NPs (2.3), whereas NPASs exhibited the smallest R value (1.7). This distinct difference indicated that the wavelength selectivity of monometallic Au NPs was primarily governed by the resonant matching between the LSPR and the incident wavelength. In contrast, the broadband extinction of NPASs enabled strong optical responses at both wavelengths, resulting in a significantly weaker wavelength dependence. This work provides essential experimental evidence for designing plasmonic catalytic substrates with improved wavelength adaptability.

1. Introduction

Plasmonic nanostructures can excite localised surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) under illumination, generating intense, localised electromagnetic field enhancements at the nanoscale and producing non-equilibrium charge carriers (hot electrons/hot holes) [1,2]. These synergistic effects substantially lower surface reaction energy barriers, facilitating charge transfer processes and enabling the selective chemical transformations of adsorbed molecules. These phenomena provide novel materials and mechanistic pathways for efficient light-to-chemical energy conversion, establishing a significant research frontier in nanophotocatalysis and surface/interface reactions [1,2,3].

Among numerous plasmonic catalytic model systems, the photoinduced dimerisation of p-nitrothiophenol (PNTP) on noble metal surfaces to form 4,4′-dimercaptoazobenzene (DMAB) is widely employed [4,5,6]. PNTP forms stable metal-S bonds with metal surfaces via its thiol group, achieving molecular anchoring while simultaneously establishing interfacial charge transfer pathways [5]. Under plasma excitation, hot electrons are injected into PNTP molecules, progressively reducing the nitro group. Adjacent molecules subsequently undergo further coupling to form azo (N=N) bonds [2,6]. This reaction exhibits distinct spectral characteristics: the symmetric stretching vibration peak of the nitro group in PNTP (1340 cm−1) gradually diminishes, while characteristic peaks associated with the azo group in DMAB (1141, 1391, and 1440 cm−1) emerge and progressively intensify. Leveraging the in situ and real-time monitoring capabilities of surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), this system has emerged as an ideal probe reaction for investigating the mechanisms and kinetics of plasmonic catalysis [6,7,8].

The plasmonic catalytic efficiency is closely related to the excitation wavelength. When the incident light matches the LSPR of the nanostructure, plasmon excitation efficiency is maximised, enabling the generation of a higher density of hot charge carriers [9,10,11]. Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) and silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs), as classical plasmonic substrates, exhibit characteristic LSPR responses in the visible spectrum, with characteristic absorption peaks near 540 nm and 420 nm, respectively [9,12]. However, nanostructures with differing morphologies and compositions exhibit distinct LSPR response characteristics, and their wavelength-dependent catalytic performance also varies [12,13]. Recently, bimetallic nanomaterials with porous structures have garnered attention due to their abundant surface active sites and potential broadband optical response [14,15,16]. However, for conventional plasmonic catalysts, catalytic efficiency often relies strictly on matching the LSPR peak. When the excitation wavelength deviates from this narrowband resonance, both the optical response and reaction efficiency decline sharply, limiting their applicability under polychromatic light or non-resonant conditions. Consequently, developing plasmonic catalytic substrates with enhanced wavelength adaptability is crucial.

In this study, we fabricated nanoporous Au-Ag shells (NPASs). These structures exhibited a distinctive broadband extinction response in the visible region (main peak at ~683 nm, shoulder at ~542 nm), contrasting markedly with the narrowband LSPR characteristics of monometallic nanoparticles. Using in situ time-resolved SERS to monitor the PNTP→DMAB probe reaction, we systematically compared reaction rates at two representative wavelengths (532 nm and 633 nm) and introduced a wavelength-dependence factor, R (k532/k633), for quantitative evaluation. Notably, although the primary extinction peak of NPASs is located in the red region (~683 nm), they demonstrated superior catalytic kinetics under green light (532 nm) excitation. This phenomenon suggested that, beyond mere extinction intensity, specific electronic excitation and decay pathways played a crucial role in the reaction process. Considering the shoulder peak features near 542 nm, we further discussed the synergistic interaction between LSPR and interband transition (IBT) processes, providing experimental rationale for designing alloyed porous plasmonic substrates with broadband response and weak wavelength dependence.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterisation of Microstructure and Optical Properties

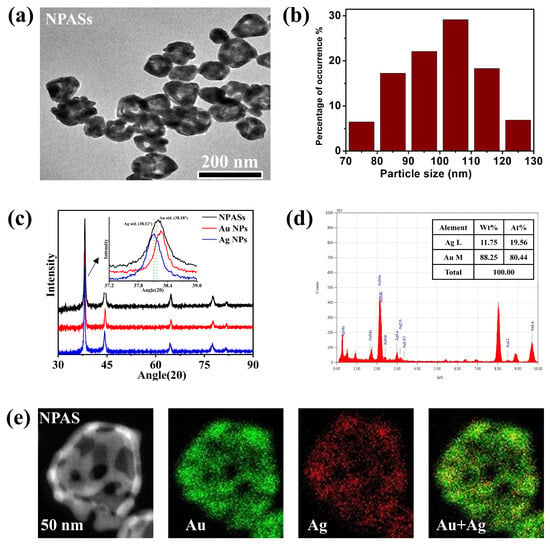

Before conducting catalytic reaction studies, the prepared NPASs were characterised in terms of their microstructure and optical properties to confirm their morphology, composition, and plasmonic response characteristics. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results, as shown in Figure 1a, revealed that NPASs exhibited a typical hollow porous structure, with nanopores formed by galvanic replacement reaction clearly observable on the particle surface. Statistical analysis of 150 randomly selected particles using Nano Measurer (version 1.2.5) software (Figure 1b) indicated that the particle size distribution of NPASs followed an approximate normal distribution, with a predominant concentration within the 70–130 nm range, and an average outer diameter of approximately 100 nm.

Figure 1.

Morphology, crystal structure, and elemental composition characterisation of NPASs. (a) TEM image; (b) particle size distribution based on TEM statistics; (c) XRD patterns of NPASs compared with those of bulk Au NPs and Ag NPs. The inset showed the magnified (111) diffraction peaks, with the vertical dashed lines indicating the standard positions of bulk Ag (JCPDS No. 04-0783) and Au (JCPDS No. 04-0784); (d) EDX spectrum; (e) HAADF-STEM image of a single NPAS particle and the corresponding Au and Ag elemental distribution maps.

Figure 1c presents the XRD patterns of NPASs, Au NPs, and Ag NPs; all three exhibit characteristic diffraction peaks typical of fcc structures. The inset magnified the (111) peak, with dashed lines indicating the standard positions of the fcc Ag (38.12°, JCPDS 04-0783) and fcc Au (38.18°, JCPDS 04-0784) (111) reflections. The (111) peak of the NPASs was shifted relative to those of the pure phases and lies between the Au and Ag peaks. This indicates that its lattice parameter lay between the two, suggesting Au–Ag alloying/solid-solution formation (consistent with Vegard’s law) [17].

Based on the (111) diffraction peak at 2θ = 38.2° (FWHM = 0.448°), the average crystallite size of the NPASs was estimated to be 18.8 nm using the Scherrer equation. This value is significantly smaller than the average particle diameter obtained from TEM statistics (~100 nm), indicating that individual NPASs are composed of multiple nanocrystalline domains, thereby exhibiting characteristics of polycrystalline or nanocrystalline aggregates.

From the Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum in Figure 1d, it can be seen that NPASs are composed of Au and Ag elements, with mass fractions of 88.25 wt% and 11.75 wt%, respectively (corresponding atomic percentages of 80.44 at% and 19.56 at%). This confirms that the material is an Au-rich Au-Ag bimetallic structure.

As shown by the high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) characterization in Figure 1e, the individual NPAS exhibits a pronounced porous structure. In terms of element distribution, the Au (green) and Ag (red) signals were relatively uniformly distributed throughout the nanobelt region. The elemental overlay image further confirmed the formation of the Au-Ag alloy structure [18].

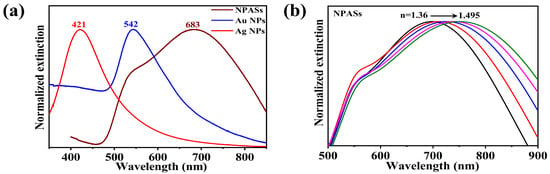

Having confirmed the porous alloy structure of NPASs, we further investigated their optical properties. Figure 2a compares the UV-vis extinction behaviour of NPASs with pure Au and Ag nanoparticles in an aqueous phase. To facilitate comparison of spectral profiles and peak positions, Figure 2a presents normalized extinction spectra; the corresponding raw (non-normalized) spectra for quantitative reference are provided in Supplementary Figure S1. The Ag NPs (~60 nm) and Au NPs (~80 nm) samples exhibited characteristic LSPR peaks at 421 nm and 542 nm, respectively. NPASs (~100 nm), however, showed a broad peak spanning 500–800 nm, with a main peak at 683 nm and a distinct shoulder peak at 542 nm.

Figure 2.

(a) Normalized UV–vis extinction spectra of NPASs, Ag NPs and Au NPs in aqueous media for comparison of spectral profiles and peak positions; the corresponding non-normalized (raw) extinction/absorbance spectra are provided in Supplementary Figure S1 for quantitative reference. (b) Evolution of NPAS extinction spectra in solvents with varying refractive indices (n = 1.36–1.495).

To further characterise the optical properties of NPASs, the spectral response of NPASs was examined in solvents with varying refractive indices (Figure 2b). As the refractive index of the medium increased (n = 1.36–1.495), the main peak at 683 nm exhibited a pronounced red shift, demonstrating the refractive index sensitivity characteristic of LSPR [18,19]. It was noteworthy that the position of the shoulder peak at 542 nm remained essentially unchanged across solvents of varying refractive indices, suggesting that this absorption band may have a different physical origin from the main peak.

When combined with two excitation wavelengths (532 nm and 633 nm), Au NPs exhibited strong extinction at 532 nm (matching its LSPR peak) and weak extinction at 633 nm; Ag NPs exhibited considerable extinction at 532 nm (arising from the LSPR tail) and negligible extinction at 633 nm; whereas NPASs, owing to their broad spectral response characteristics, maintained pronounced extinction at both 532 nm (within the shoulder peak region) and 633 nm (near the main peak).

2.2. Plasmon-Driven PNTP Surface Catalytic Reactions

Based on the aforementioned optical property analysis, excitation wavelengths of 532 nm and 633 nm were selected to systematically compare the plasmonic catalytic performance of the three substrates. Following immersion of NPASs, Ag NPs, and Au NPs substrates in a 0.1 mM PNTP ethanolic solution to form self-assembled monolayers, time-dependent SERS spectra were acquired under 532 nm and 633 nm excitation to compare the wavelength dependence of the PNTP → DMAB reaction systematically.

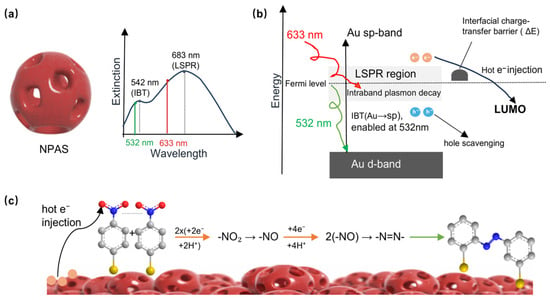

Figure 3 illustrates the plasmonic catalytic mechanism by which NPASs drove PNTP coupling reactions. PNTP molecules were adsorbed onto the metal surface through metal–sulfur bonds, whereby molecular immobilization was achieved and interfacial charge transfer pathways were established [5]. Upon laser irradiation, NPASs underwent LSPR excitation coupled [6] with IBT in the Au component, which generated high-energy non-equilibrium hot carriers. The wavelength-dependent excitation mechanism shown in Figure 3, particularly the synergistic contribution of interband transitions, was discussed in detail in Section 2.3. As illustrated in Figure 3b, hot electrons were injected into the LUMO of the adsorbed molecules, driving the stepwise reduction of the nitro group [5,20,21]. Simultaneously, surrounding water molecules were oxidized by hot holes through a “hole scavenging” process, whereby the requisite protons (H+) were generated in situ for the reaction. Through the combined participation of hot electrons and protons, the coupling between adjacent molecules was facilitated, leading to the formation of –N=N– azo bonds and the ultimate yield of DMAB. Under the conditions studied, only light irradiation was required for this process to achieve complete conversion, without the need for additional reducing agents [21].

Figure 3.

Catalytic mechanism of NPASs. (a) Extinction spectrum of NPASs highlighting the IBT (542 nm) and LSPR (683 nm) modes. (b) Energy level diagram illustrating the hot carrier dynamics under dual-wavelength excitation; 532 nm activates both LSPR and Au IBT to provide more efficient hot electron injection into the PNTP LUMO. (c) Detailed chemical pathway for the stepwise reduction and coupling of PNTP to form DMAB on the nanoporous surface. In panel (c), the purple-red porous spheres represent the as-prepared nanoporous Au–Ag shells; in the ball-and-stick models, C is gray, N is blue, O is red, and S is yellow.

According to literature reports, direct spectroscopic evidence for the surface-catalysed dimerisation of PNTP to DMAB includes: (1) The attenuation or disappearance of the symmetric stretching vibration peak of the nitro group (–NO2) at 1340 cm−1; (2) The appearance of characteristic peaks attributed to DMAB at 1141, 1391, and 1440 cm−1 [6]. This study employed the SERS intensity changes in the aforementioned characteristic peaks as probes to track the reaction kinetics of PNTP on NPASs, Ag NPs, and Au NPs when excited at 532 nm and 633 nm, respectively.

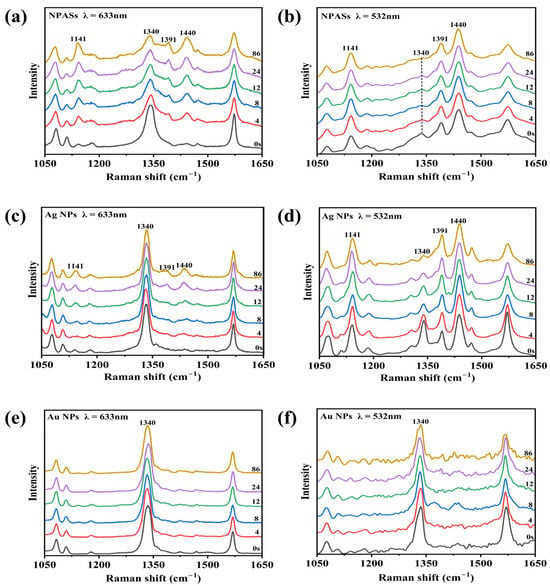

Figure 4 compares the time-dependent SERS spectral evolution of PNTP at two excitation wavelengths on NPASs (a,b), Ag NPs (c,d), and Au NPs (e,f) substrates. At the initial time point (0 s), all systems exhibited the characteristic peaks typical of PNTP: 1076 cm−1 (C−S stretching vibration) [22], 1340 cm−1 (–NO2 symmetric stretching vibration) [6,22,23], and 1574 cm−1 (benzene ring skeletal vibration) [6,22]. Among these, the characteristic peak at 1340 cm−1 served as the key fingerprint peak for determining whether PNTP conversion had occurred [6,22,23].

Figure 4.

In situ time-resolved SERS spectra of PNTP on various substrate surfaces under different excitation wavelengths. (a,b) NPASs; (c,d) Ag NPs; (e,f) Au NPs. The left column (a,c,e) corresponds to 633 nm excitation, while the right column (b,d,f) corresponds to 532 nm excitation. Experimental conditions: laser power 0.42 mW, integration time of 4 s.

As shown in Figure 4a, under 633 nm excitation, the 1340 cm−1 peak of PNTP molecules on the surface of NPASs exhibited a slow decay with prolonged irradiation time. Concurrently, the characteristic peaks of DMAB at 1141, 1391, and 1440 cm−1 (corresponding to C–N stretching, N=N stretching, and in-plane C–H bending vibrations, respectively) [6,23] showed no significant enhancement. These results indicated that the photocatalytic conversion efficiency was relatively low under these conditions. In contrast, under 532 nm excitation (Figure 4b), the 1340 cm−1 peak exhibited significant attenuation during the initial reaction phase, while intense characteristic DMAB peaks rapidly appeared at 1141, 1391, and 1440 cm−1, indicating a rapid progression of the reaction.

For comparison, identical control experiments were conducted on Ag NP and Au NP substrates. As shown in Figure 4c–f, both monometallic nanoparticle substrates exhibit trends consistent with those observed for NPASs: the decay rate of the 1340 cm−1 peak under 532 nm excitation was markedly faster than under 633 nm conditions. This indicated that 532 nm laser excitation more effectively drove the surface-catalysed dimerisation reaction of PNTP on all three substrates.

The aforementioned wavelength dependence could be preliminarily understood by examining the UV-Vis spectrum in Figure 2. The extinction intensity of Au NPs at 532 nm was significantly higher than at 633 nm, consistent with the position of their LSPR peak (542 nm). However, Ag NPs exhibited weaker extinction at both wavelengths; their extinction at 532 nm remained superior to that at 633 nm. Notably, NPASs demonstrated slightly stronger extinction at 633 nm than at 532 nm, yet exhibited higher catalytic efficiency upon excitation at 532 nm. This phenomenon will be further discussed in Section 2.3.

Given that the reaction on NPAS substrates under 532 nm excitation at 0.42 mW was largely completed in its initial phase, it was challenging to capture the complete kinetic process. Therefore, the laser power was reduced to 0.17 mW to obtain more detailed time-resolved spectral information.

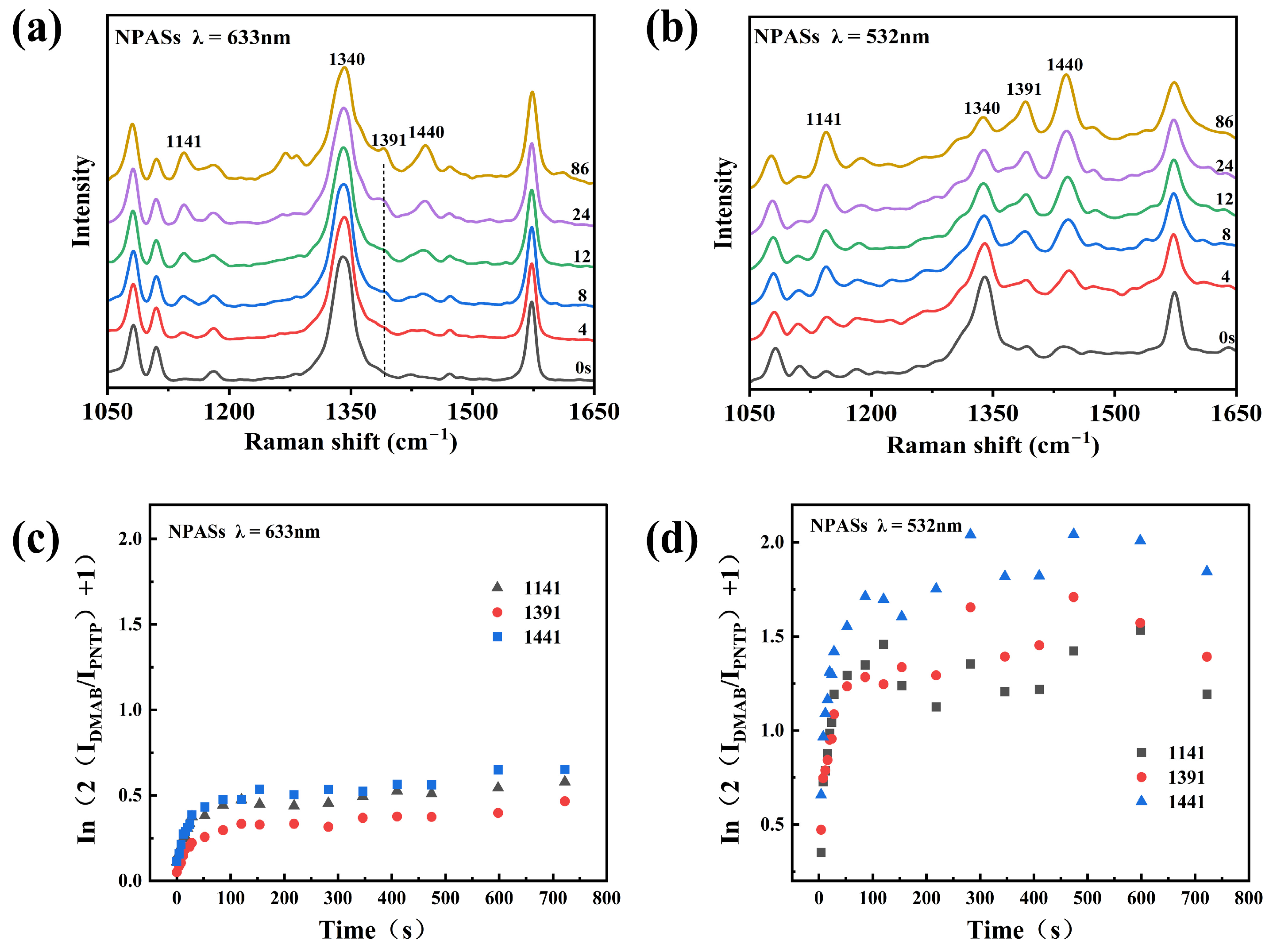

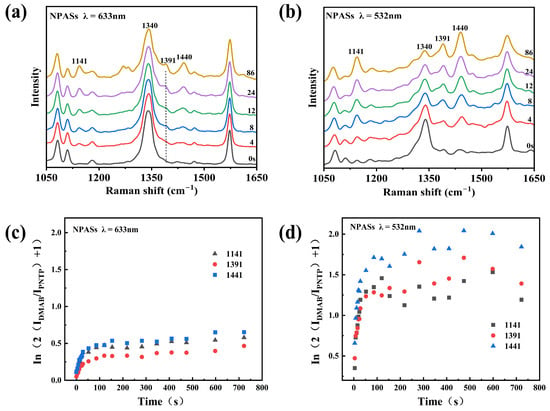

Figure 5a and Figure 5b, respectively, illustrate the temporal evolution of the SERS spectra of PNTP on the surface of NPASs under 633 nm and 532 nm excitation. Under 532 nm excitation (Figure 5b), the intensity of the nitro vibration peak at 1340 cm−1 gradually diminished with prolonged irradiation time, while the characteristic DMAB peaks at 1141, 1391 cm−1, and 1440 cm−1 progressively intensified, indicating the ongoing reaction. In contrast, under 633 nm excitation (Figure 5a), the 1340 cm−1 peak maintained high intensity throughout the monitoring, with limited growth of DMAB characteristic peaks, indicating a slower reaction progression.

Figure 5.

Photocatalytic reaction kinetics analysis on NPAS substrates under low laser power (0.17 mW). (a,b) Evolution of SERS spectra over time upon excitation at 633 nm and 532 nm, respectively; (c,d) Corresponding ln(2IDMAB/IPNTP + 1) versus time curves. Different symbols in the figure denote distinct characteristic peaks of DMAB.

To quantitatively compare the reaction kinetic behaviour, we plotted ln(2IDMAB/IPNTP + 1) versus time based on the first-order reaction model (Figure 5c,d), where IDMAB and IPNTP represent the peak heights (maximum intensities) of the baseline-corrected SERS bands of DMAB (1141, 1391, 1440 cm−1) and PNTP (1340 cm−1), respectively.

As shown in Figure 5d, the ln(2IDMAB/IPNTP + 1) values for all three peaks rapidly increased over time under 532 nm excitation, plateauing after approximately 400 s, indicating near-completion of the reaction. Under 633 nm excitation (Figure 5c), this value increased slowly and did not reach a plateau throughout the monitoring period. By performing linear fitting on the initial stage, the apparent rate constant k could be calculated. For instance, at an excitation power of 0.17 mW, the k values for the 633 nm excitation peaks at 1141, 1391, and 1440 cm−1 were 0.0027, 0.0021, and 0.0023 s−1, respectively. Under 532 nm excitation, these values were 0.0073, 0.0044, and 0.0105 s−1. It is worth noting that significant variations were observed in the apparent k values derived from the three DMAB characteristic bands under 532 nm excitation. This discrepancy is likely attributed to wavelength- and mode-dependent SERS enhancement (including possible charge-transfer contributions) [24], as well as the shorter initial linear regime resulting from the faster reaction kinetics.

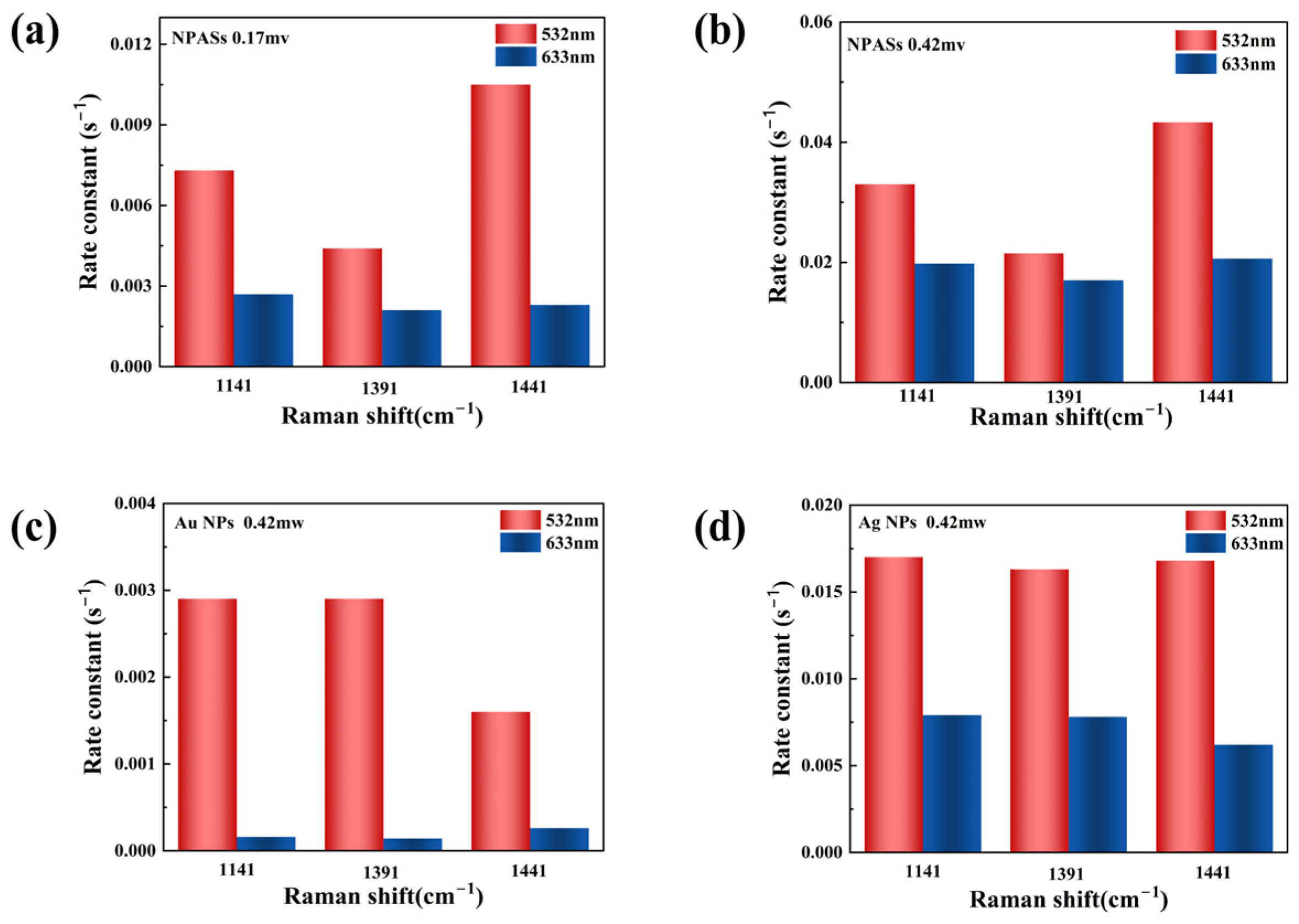

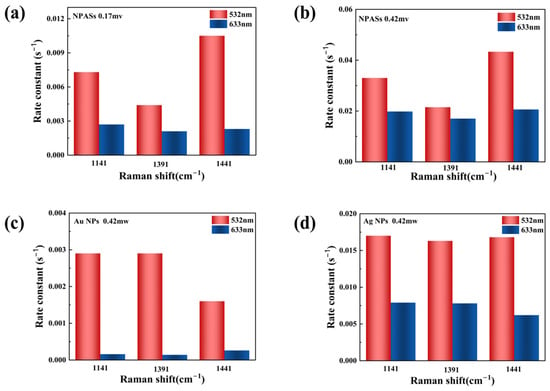

Figure 6 summarizes the apparent reaction rate constants on different substrates under various excitation conditions (specific values are provided in Supplementary Table S1). As shown in Figure 6a, at a laser power of 0.17 mW, NPASs exhibit superior catalytic activity when excited at 532 nm compared to excitation at 633 nm.

Figure 6.

Comparison of apparent reaction rate constants (k) for different substrates under varying excitation conditions. (a) NPASs (0.17 mW); (b) NPASs (0.42 mW); (c) Au NPs (0.42 mW); (d) Ag NPs (0.42 mW). Red bars represent 532 nm excitation; blue bars represent 633 nm excitation.

When the laser power was increased to 0.42 mW (Figure 6b), the rate constants at both wavelengths increased significantly, indicating the promotional effect of the laser power on the reaction [25,26]. Although the relative difference between the two excitation wavelengths narrowed at high power, the 532 nm excitation still exhibited a higher reaction rate.

Comparative experiments revealed that Au NPs (Figure 6c) and Ag NPs (Figure 6d) also exhibited wavelength-dependent trends similar to NPAS at a power of 0.42 mW. Among these, Au NPs exhibited the most pronounced wavelength selectivity, with differences exceeding one order of magnitude. This significant disparity was primarily attributed to the substantial spectral overlap between the localised surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peak of Au NPs (542 nm) and the 532 nm excitation light. As demonstrated experimentally by Liu et al., when the incident laser (532 nm) resonantly overlaps with the LSPR frequency of Au nanoantennas (approximately 520–550 nm), it induces significant localised field enhancement and charge transfer, leading to a pronounced shift in Raman spectral characteristics [9]. Moreover, Raja Mogan and Lee also noted in their review that precise spectral matching is the key mechanism for maximising the plasmonic enhancement effect [12].

By contrast, Ag NPs exhibited relatively mild wavelength selectivity, with the rate constant under 532 nm excitation being approximately 2.1–2.7 times higher than that under 633 nm excitation.

2.3. Wavelength-Dependent Analysis

The results above indicated that all three substrates exhibited a general trend of superior performance under 532 nm excitation compared with 633 nm, though the degree of wavelength dependence varied between materials. To quantitatively compare the differences in catalytic efficiency across excitation wavelengths, we defined the wavelength dependence factor R = k532/k633 [27]. R was calculated under identical incident power conditions (0.42 mW), derived from multiple DMAB characteristic peaks and averaged (see Supplementary Table S2).

Results indicated that Au NPs exhibited the most pronounced wavelength dependence (mean R = 15.0), followed by Ag NPs (mean R = 2.3), with NPASs showing the least (mean R = 1.7). This phenomenon can be understood from several perspectives.

- (1)

- Photon energy and effective carriers

At 532 nm (2.33 eV), the photon energy is higher than that at 633 nm (1.96 eV), with a difference of 0.37 eV. Within the framework of plasmon decay generating non-equilibrium carriers, the higher photon energy elevates the upper limit of the carrier energy distribution. This enables a greater number of high-energy carriers to possess the capacity to overcome the energy barrier required for interfacial charge transfer [28].

It is noteworthy that at a fixed incident power, the photon flux at 633 nm is approximately 19% higher than that at 532 nm (Nphoton633/Nphoton532 ≈ 1.19).

To normalise this photon flux disparity and evaluate photocatalytic efficiency more intrinsically, we calculated the apparent quantum yield (AQY) (see Supplementary Table S3). Results indicated that despite higher photon flux at 633 nm, all substrates exhibited significantly higher AQY at 532 nm. Specifically, the AQY of Au NPs decreased by an order of magnitude (approximately 15-fold) from 532 nm to 633 nm, exhibiting strong resonance dependence; whereas NPASs differed by only about 2-fold and maintained high quantum efficiency at 633 nm. This quantitative evidence confirms that the energy distribution of effective carriers plays a more crucial role than photon flux in determining reaction rates [28,29]. In other words, the high-energy hot electrons generated at 532 nm possess a greater advantage in overcoming the reaction energy barrier, thereby providing the physical basis for the common wavelength-dependent trend observed across the three substrates.

- (2)

- Differences in optical response and degree of wavelength dependence

Given the commonality in photon energy composition, variations in R values across different substrates primarily reflect differences in their extinction responses at two excitation wavelengths.

The LSPR peak position of Au NPs (542 nm) exhibited a high degree of spectral matching with the 532 nm laser but a significant mismatch with the 633 nm laser. As is evident from Figure 2a, Au NPs demonstrated markedly different extinction behaviours at these two wavelengths. This pronounced optical response, combined with the photon energy factor, resulted in the most substantial wavelength dependence (R = 15.0).

The LSPR peak of Ag NPs occurs at 421 nm, which does not coincide with either excitation wavelength. When excited at 532 nm, this wavelength lay within the descending region of the extinction curve, yet a certain optical response remained observable. However, under 633 nm excitation, the response approached zero. Consequently, the wavelength dependence (R = 2.3) was moderate.

In contrast, NPASs exhibited distinct behavioural characteristics. Their ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra revealed a higher extinction intensity at 633 nm (close to the 683 nm main peak position) than at 532 nm (corresponding to the shoulder peak region). However, experimental results indicated that catalytic efficiency was actually higher under 532 nm excitation conditions. This phenomenon demonstrated that, within NPAS systems, extinction intensity alone could not serve as the sole determinant of catalytic efficiency. This may be attributed to the higher photon energy at 532 nm, alongside potential absorption or energy transfer mechanisms distinct from those within the main peak in the shoulder region. Furthermore, as NPAS exhibited a significant optical response at both 532 nm and 633 nm excitation wavelengths with minimal variation in extinction intensity, its overall wavelength dependence was the weakest (R = 1.7).

- (3)

- Physical Origin of the 542 nm Shoulder Peak

With an increasing solvent refractive index, the 683 nm main peak exhibited a pronounced red shift (Figure 2), demonstrating the high sensitivity of typical LSPR to the dielectric environment [18,19]. In contrast, the position of the 542 nm shoulder peak remained virtually unchanged with refractive index variation, indicating that this shoulder peak did not originate from conventional localised surface plasmon resonance but corresponded to a distinct physical mechanism. Given that NPASs constitute an Au-dominant system (~80 at%), and with the shoulder peak energy (~2.3 eV) being close to the interband transition threshold of Au’s d-sp band (2.4 eV) [30,31], this shoulder peak can be attributed to interband transition absorption of the Au component. Unlike LSPR excitation, IBT constitute direct optical absorption and can directly generate electron-hole pairs. Previous studies indicate that interband transition excitation exhibits higher catalytic activity or greater carrier generation efficiency for catalysis compared to direct LSPR excitation [32]. Therefore, under 532 nm excitation, in addition to the LSPR effect, the interband transition pathway of Au may further provide an additional carrier source for the system. This synergistic effect between LSPR and IBT was likely the key reason why NPASs exhibited significantly superior catalytic activity at 532 nm compared to 633 nm [32].

This broadband adaptability stands in stark contrast to the high wavelength selectivity commonly observed in recently reported plasmonic catalysts. Many plasmon-driven coupling systems exhibit a precipitous drop in reaction efficiency once the excitation frequency deviates from the substrate’s primary optical absorption channel. For instance, Kong et al. reported that on silver nanoislands, the conversion of 4-NTP to DMAB was readily observed under 532 nm excitation but became negligible under 633 nm excitation at cryogenic temperatures [6]. Similarly, multi-wavelength studies on Ag@Au/ITO systems by Ding et al. demonstrated that the yield of DMAB declined progressively from 532 nm to 633 nm and 785 nm, underscoring the limitations of resonance matching in conventional substrates [20].

In contrast, NPASs exhibited a broadband extinction feature, characterized by a main band in the red region accompanied by an additional shoulder near the green region. This unique optical profile enabled strong responses at both 532 nm and 633 nm. Consequently, the wavelength dependence was significantly attenuated, as quantitatively described by the low wavelength dependence factor (R = 1.7), highlighting the superior wavelength adaptability of the NPASs compared to conventional narrowband catalysts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

p-Nitrothiophenol (PNTP, 80%), 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS, 99%), hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2, 30%), and concentrated sulphuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Tetrachloroauric acid hydrate (HAuCl4·4H2O), silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.8%), and ethanol were procured from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Trisodium citrate (C6H5Na3O7, 99%) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All chemicals were of analytical grade and used directly without further purification.

3.2. Synthesis of NPASs

NPASs were synthesized using Ag NPs as precursors via a galvanic displacement reaction with HAuCl4. The procedure was as follows:

First, 100 mL of a 1 mM AgNO3 solution was added to a three-necked flask. A condenser reflux apparatus was attached, and the mixture was heated to boiling under magnetic stirring. Subsequently, 1 mL of a 1 wt% trisodium citrate solution was rapidly added as the reducing agent. After reacting for 40 min, a colloidal solution of silver nanoparticles with an average particle size of approximately 60 nm was obtained. A portion of this colloidal solution was set aside to serve as the Ag NPs reference sample for subsequent characterization.

Subsequently, under boiling and stirring conditions, 1.8 mL of a 50 mM HAuCl4 was rapidly added to the aforementioned silver colloid, and the reaction was continued for 1 h. Upon completion of the reaction, heating was ceased, and the mixture was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. This yielded a purple-red NPAS colloid with an average particle size of approximately 100 nm.

3.3. Synthesis of Au NPs

Au NPs were synthesized via the Frens method. Briefly, 100 mL of a 0.01 wt% HAuCl4 aqueous solution was heated to boiling under vigorous magnetic stirring equipped with a reflux condenser. Upon boiling, 0.5 mL of a 1 wt% trisodium citrate solution was rapidly injected into the mixture. The reaction was refluxed for 20 min, during which the solution color shifted to wine red, indicating the formation of nanoparticles. Finally, the heating source was removed, and the colloidal solution was allowed to cool to room temperature. The obtained Au NPs possessed an average diameter of approximately 80 nm.

3.4. Preparation of SERS-Active NPAS Substrates

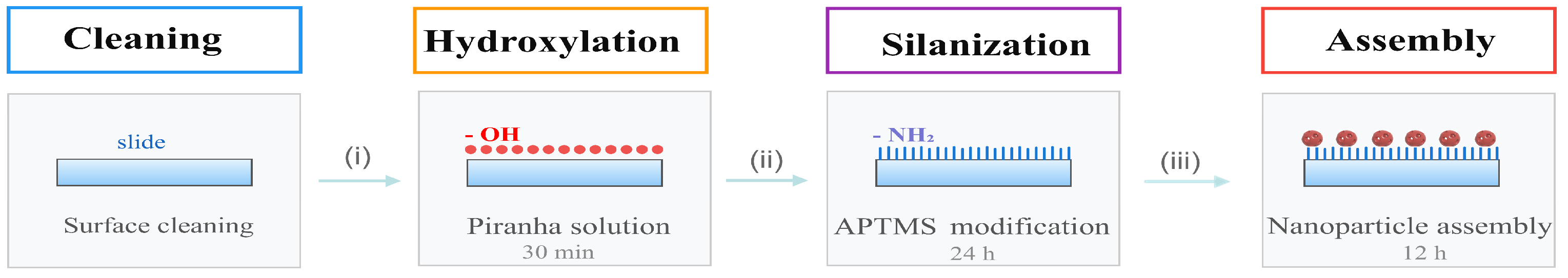

As shown in Figure 7, a SERS-active substrate was prepared via surface chemical modification. This preparation process primarily comprised three key steps: hydroxylation, silanisation, and the immobilisation and assembly of metal nanoparticles.

Figure 7.

SERS-active Substrate Preparation Process: (i) hydroxylation, (ii) silanisation, (iii) metal Nanoparticle Adsorption and Assembly (the purple-red porous spheres represent the as-prepared nanoporous Au–Ag shells).

First, the slides were washed alternately with detergent and ultrapure water, then dried with nitrogen (N2). To introduce abundant hydroxyl groups (–OH) onto the glass surface, the slides were immersed in freshly prepared piranha solution (concentrated sulphuric acid: hydrogen peroxide = 7:3) for 30 min. Following removal, they were rinsed with copious amounts of ultrapure water to eliminate residual acid solution and dried with N2.

Subsequently, surface silanisation modification was performed. The hydroxylated slides were placed in a sealed 5% APTMS (3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane) solution and reacted at room temperature for 24 h to achieve amino group (–NH2) functionalisation of the surface. Following the reaction, the slides were sequentially rinsed with ultrapure water, anhydrous ethanol, and ultrapure water to remove physically adsorbed silane molecules, then dried with N2.

The nanoparticle assembly was then performed. To mitigate the risk of agglomeration during assembly with high-concentration colloids and enhance the single-particle dispersion of the substrate, the NPASs, Au NPs, and Ag NPs colloids were diluted to one-third, one-half, and one-half of their original concentrations, respectively. The aminated slides were immersed in these diluted solutions and left to stand for 12 h. Following removal, surfaces were gently rinsed with ultrapure water to remove unbound particles. After drying with nitrogen gas, NPASs, Au NPs, and Ag NPs SERS substrates were obtained.

3.5. Microstructural Characterization and Raman Spectroscopy

The prepared nanomaterials and SERS substrates were characterised using the following methods. UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured using a UV-2550 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Microstructural characterisation was performed by TEM using a JEM-2100F microscope (JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan). Elemental composition was analysed via EDX equipped on the same JEM-2100F system. XRD patterns were collected using a PW-1830 diffractometer (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Raman spectra were acquired using a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope/spectrometer, employing excitation sources of 532 nm and 633 nm lasers (Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The integration time for Raman spectra in this study was set to 4 s.

3.6. Dynamic Analysis Methods

To quantitatively evaluate reaction rates under varying conditions, this study analysed the coupling process of PNTP based on a first-order reaction kinetic model. According to the law of mass action, the reaction rate is proportional to the residual surface concentration of PNTP [33], yielding the following rate equation:

In the equation, a denotes the initial concentration of PNTP, x represents the concentration of the product DMAB at time t, and k0 is the rate constant. Since two PNTP molecules couple to form one DMAB molecule, the remaining PNTP concentration is (a − 2x). Integrating the differential equation under the boundary condition (at t = 0, x = 0) yields the concentration evolution over time:

Given the difficulty in directly monitoring absolute surface concentrations during experiments, this study employed the relative SERS intensity ratio as a quantitative basis for comparison. Based on the physical correlation that SERS intensity (I) was proportional to molecular concentration, substituting IDMAB for x and IPNTP for (a − 2x) transforms the aforementioned equation into the following linearised kinetic model:

In this work, the SERS intensity was extracted as the peak height (maximum intensity) of the baseline-corrected Raman band (instead of the integrated peak area). Here, k denotes the apparent rate constant, which is proportional to k0. The value of k is directly obtained from the slope by performing a linear fit to the experimental data [34].

4. Conclusions

This study prepared nanoporous gold-silver shells (NPASs) and systematically compared their catalytic performance with Au NPs and Ag NPs in the PNTP coupling reaction to generate DMAB under 532 nm and 633 nm excitation. All three substrates exhibited a general trend in which 532 nm excitation outperformed 633 nm excitation. Quantitative analysis of the wavelength dependence factor R (k532/k633) revealed significant differences among substrates: Au NPs exhibited a strong LSPR response at 532 nm but a weak response at 633 nm, demonstrating the strongest wavelength selectivity (R = 15.0); Ag NPs showed intermediate selectivity (R = 2.3); whereas NPASs, owing to their broad spectral response, exhibited minimal extinction disparity at both wavelengths and the weakest wavelength dependence (R = 1.7). These results indicated that plasmonic catalytic efficiency was jointly influenced by photon energy and the optical response characteristics of the material, providing necessary guidance for designing plasmonic catalysts and selecting excitation wavelengths.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16020166/s1, Figure S1: Raw (non-normalized) UV-Vis extinction spectra of Ag NPs, Au NPs, and NPASs; Table S1: Reaction rate constants of different substrates at various excitation wavelengths and laser powers; Table S2: Wavelength dependence factor R (k532/k633) of different substrates at 0.42 mW; Table S3: Estimated apparent AQY at P = 0.42 mW. Reference [35] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y. and L.Q.; methodology, W.Y., W.G., G.W. and X.L.; validation, W.G., G.W., X.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, W.Y., W.G., G.W. and S.L.; investigation, W.Y., W.G., G.W., X.L. and S.L.; resources, W.Y., L.X. and D.Y.; data curation, W.Y. and W.G.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Y. and W.G.; writing—review and editing, W.Y., W.G., G.W., X.L., L.Q., S.L., L.X. and D.Y.; visualization, W.Y. and W.G.; supervision, W.Y., L.Q., L.X. and D.Y.; project administration, W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. and L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52201215.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Microstructural characterizations (SEM and TEM) were carried out in the Analytical and Testing Center of HUST.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khurgin, J.; Bykov, A.Y.; Zayats, A.V. Hot-electron dynamics in plasmonic nanostructures: Fundamentals, applications and overlooked aspects. eLight 2024, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, M.; Brancato, A.; Longo, C.; Barcellona, M.; Fragalà, M.E.; Fazio, E.; Compagnini, G.; D’Urso, L. Tuning plasmonic reactivity: Influence of nanostructure, and wavelength on the dimerization of 4-NTP. J. Catal. 2025, 450, 116267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, S.; Acharya, A.; Dehghan, Z. Revisiting thermal and non-thermal effects in hybrid plasmonic antenna reactor photocatalysts. Chem Catal. 2025, 5, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, Z.-X.; Zhang, J.-X.; Zhang, X.-B.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Z.-C. Probing coverage-dependent adsorption configuration and on-surface dimerization by single-molecule tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 129, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Ehtesabi, S.; Höppener, C.; Deckert-Gaudig, T.; Schneidewind, H.; Kupfer, S.; Gräfe, S.; Deckert, V. Mechanism of Plasmon-Induced Catalysis of Thiolates and the Impact of Reaction Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, T.; Kang, B.; Wang, W.; Deckert-Gaudig, T.; Zhang, Z.; Deckert, V. Thermal-effect dominated plasmonic catalysis on silver nanoislands. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 10745–10750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Cao, J.R.; Wang, S.L.; Huang, M.J. In situ surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy study of interfacial catalytic reaction of bifunctional metal nanoparticles. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2024, 73, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, C.R.; Santos, J.J.; Lopes, D.S.; Ferreira, D.C.; Andrade, G.F.S.; Corio, P. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Study of the Product-Selectivity of Plasmon-Driven Reactions of p-Nitrothiophenol in Silver Nanowires. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 49192–49198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Feng, K.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, B.; Dong, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Quantifying the distinct role of plasmon enhancement mechanisms in prototypical antenna-reactor photocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Zhu, L.; Bao, X.; Liang, X.; Zheng, Z. Engineering hybrid plasmonic nanomaterials for solar energy conversion: Insight into the structure-function relations. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2025, 702, 120351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, D.; Lv, Q.; Lee, C. Integrative plasmonics: Optical multi-effects and acousto-electric-thermal fusion for biosensing, energy conversion, and photonic circuits. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 5342–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogan, T.R.; Lee, H.K. Architecting light for catalysis: Emerging frontiers in plasmonic–photonic crystal hybrids for solar energy conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 29806–29832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Kishida, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Kawahara, T.; Honda, K.; Kagawa, R.; Takeyasu, N.; Shoji, S. Visualization of plasmon-enhanced electric fields in silver dendritic fractal structures. Opt. Commun. 2025, 591, 132109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Chang, Y.-S.; Escobedo, E.; Gong, J. Enhancing photocatalytic activity through the manipulation of intrinsic electric fields in yolk–shell hollow AuPd@TiO2 structures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 7503–7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Kan, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, D. Stable Au–Ag nanoframes based on Au nanorods: Construction and plasmon-enhanced catalytic performance. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 5799–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.S.; Rajendran, S.; Arun, P.S.; Vijaykumar, A.; Mathew, T.; Gopinath, C.S. Bimetallic and plasmonic Ag and Cu integrated TiO2 thin films for enhanced solar hydrogen production in direct sunlight. Energy Adv. 2024, 3, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, M. Ag-Au bimetallic nanoparticle-based electrochemical sensing platform for quantification of B-type natriuretic peptide. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajna, N.D.; Rajeev, K.S. Shape-controlled Synthesis and Bulk Refractive Index Sensitivity Studies of Gold Nanoparticles for LSPR-based Sensing. Plasmonics 2024, 20, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McOyi, M.P.; Mpofu, K.T.; Sekhwama, M.; Mthunzi-Kufa, P. Developments in Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Plasmonics 2024, 20, 5481–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yang, Y.; Kang, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Kong, L.; Song, P. Effect of hot electron induced charge transfer generated by surface plasmon resonance on Ag@Au/ITO/PNTP systems. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 310, 123911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, S.; Hu, Y.; Yan, R.; Gao, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Dong, J. Fabrication of 3D popcorn-like Ag microstructures film array substrate: SERS and catalytic property. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 44, 103760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Huang, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. In-Situ investigation of the catalytic hydrogenation reaction of 4-nitrothiophenol by using single Pt@Au nanowires as a new platform. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 176018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, Y.; Song, P.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, L. Surface plasmon-assisted catalytic reduction of p-nitrothiophenol for the detection of Fe2+ by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 680, 115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Puebla, R.A. Effects of the Excitation Wavelength on the SERS Spectrum. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Fan, S.; Nguyen, W.; Chen, W.; Zhao, B.; Li, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Dong, J. Developing highly reliable Ag@NaYF4 hybrid structures for efficiently improving optical property. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 173, 112675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Yanagiyama, K.; Mukherjee, P.; Phulkerd, P.; Sathiyan, K.; Sawade, E.; Wada, T.; Taniike, T. Identifying rate-limiting steps in photocatalysis: A temperature-and light intensity-dependent diagnostic of charge supply vs. charge transfer. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 16204–16211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Huang, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhou, N.; Tang, H.; Meng, G. SERS spectral evolution of azo-reactions mediated by plasmonic Au@Ag core-shell nanorods. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 4730–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Diederich, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Höhn, C.; Harbauer, K.; Fan, F.; Li, C.; van de Krol, R.; Friedrich, D. Ultrafast nonthermal electron transfer at plasmonic interfaces. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, S.; Gao, S. Unified Description of Thermal and Nonthermal Hot Carriers in Plasmonic Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 12804–12813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Wu, S.; Yim, J.E.; Zhao, B.; Sheldon, M.T. Hot Electrons in a Steady State: Interband vs Intraband Excitation of Plasmonic Gold. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 19077–19085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, M.; Venugopal, A.; Tordera, D.; Jonsson, M.P.; Biskos, G.; Schmidt-Ott, A.; Smith, W.A. Hot Carrier Generation and Extraction of Plasmonic Alloy Nanoparticles. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Nguyen, S.C.; Ye, R.; Ye, B.; Weller, H.; Somorjai, G.A.; Alivisatos, A.P.; Toste, F.D. A Comparison of Photocatalytic Activities of Gold Nanoparticles Following Plasmonic and Interband Excitation and a Strategy for Harnessing Interband Hot Carriers for Solution Phase Photocatalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X.; Tao, Y.; Yang, G.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Q. Tuning the modal coupling in three-dimensional Au@Cu(2)O@Au core-shell-satellite nanostructures for enhanced plasmonic photocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 8069–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Geng, W.; Lu, X.; Qian, L.; Luo, S.; Xu, L.; Shi, Y.; Song, T.; Li, M. Unveiling the Photocatalytic Behavior of PNTP on Au-Ag Alloy Nanoshells Through SERS. Catalysts 2025, 15, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cara, E.; Hönicke, P.; Kayser, Y.; Beckhoff, B.; Giovannozzi, A.M.; Klapetek, P.; Zoccante, A.; Cossi, M.; Tay, L.-L.; Boarino, L.; et al. Molecular surface coverage standards by reference-free GIXRF supporting SERS and SEIRA substrate benchmarking. Nanophotonics 2024, 13, 4605–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.