Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Conversion of Methane at Low Temperatures

Abstract

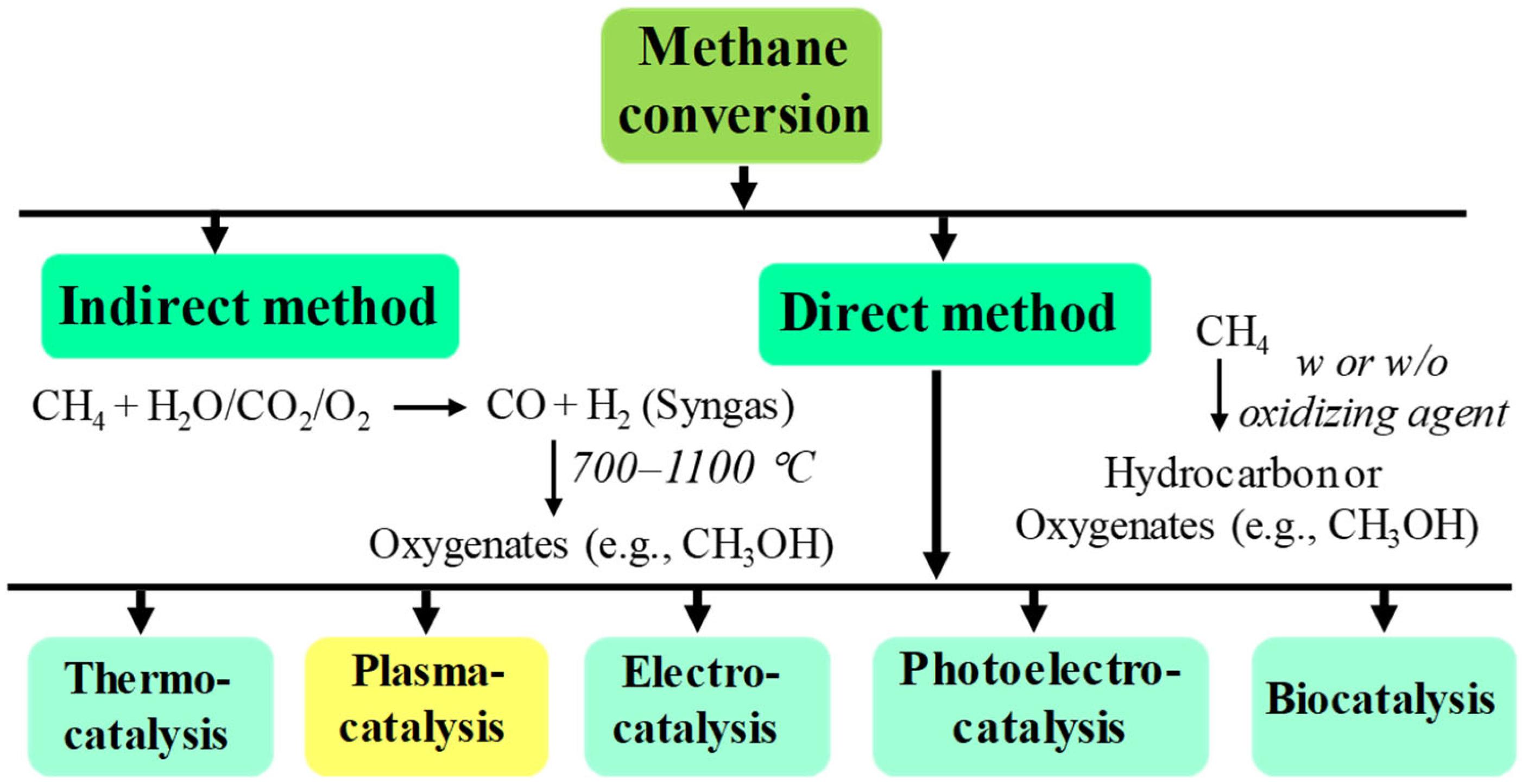

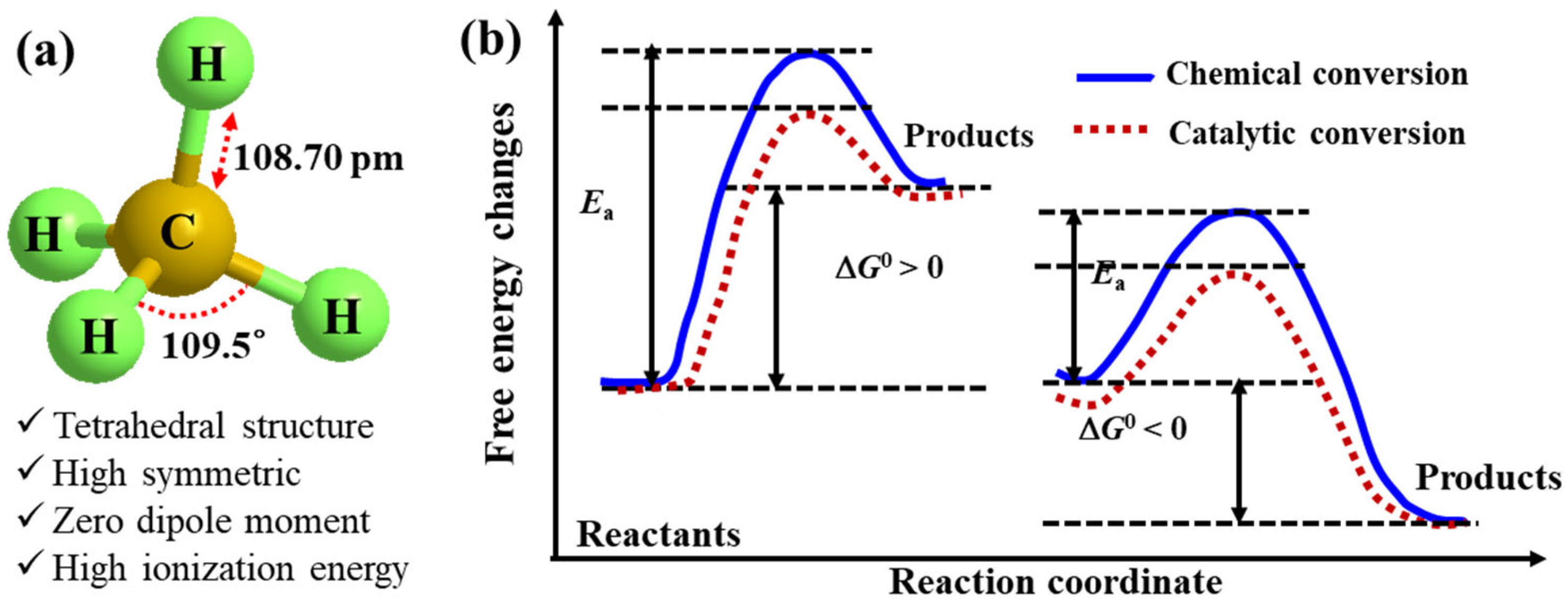

1. Introduction

2. Thermodynamics of Methane Conversions

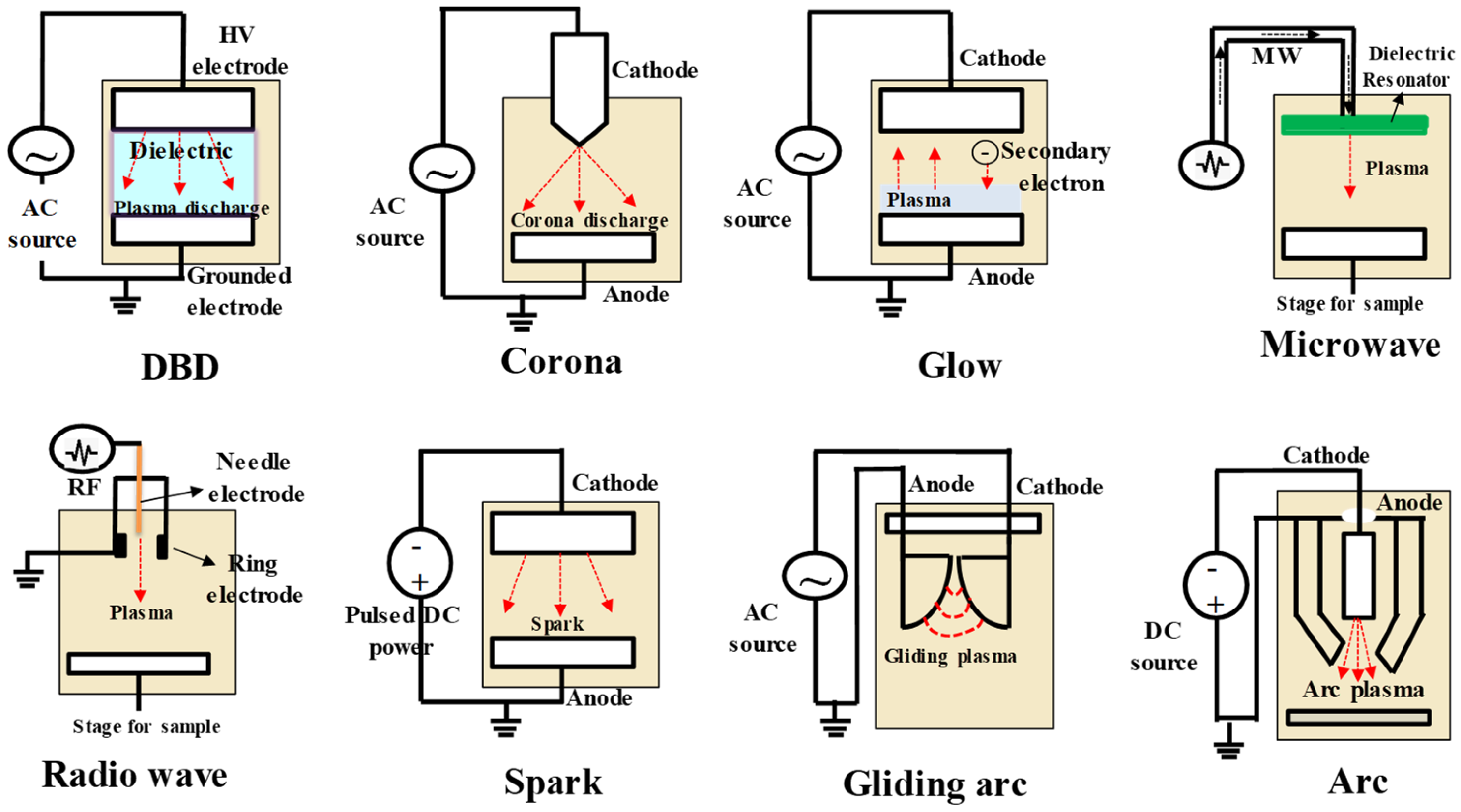

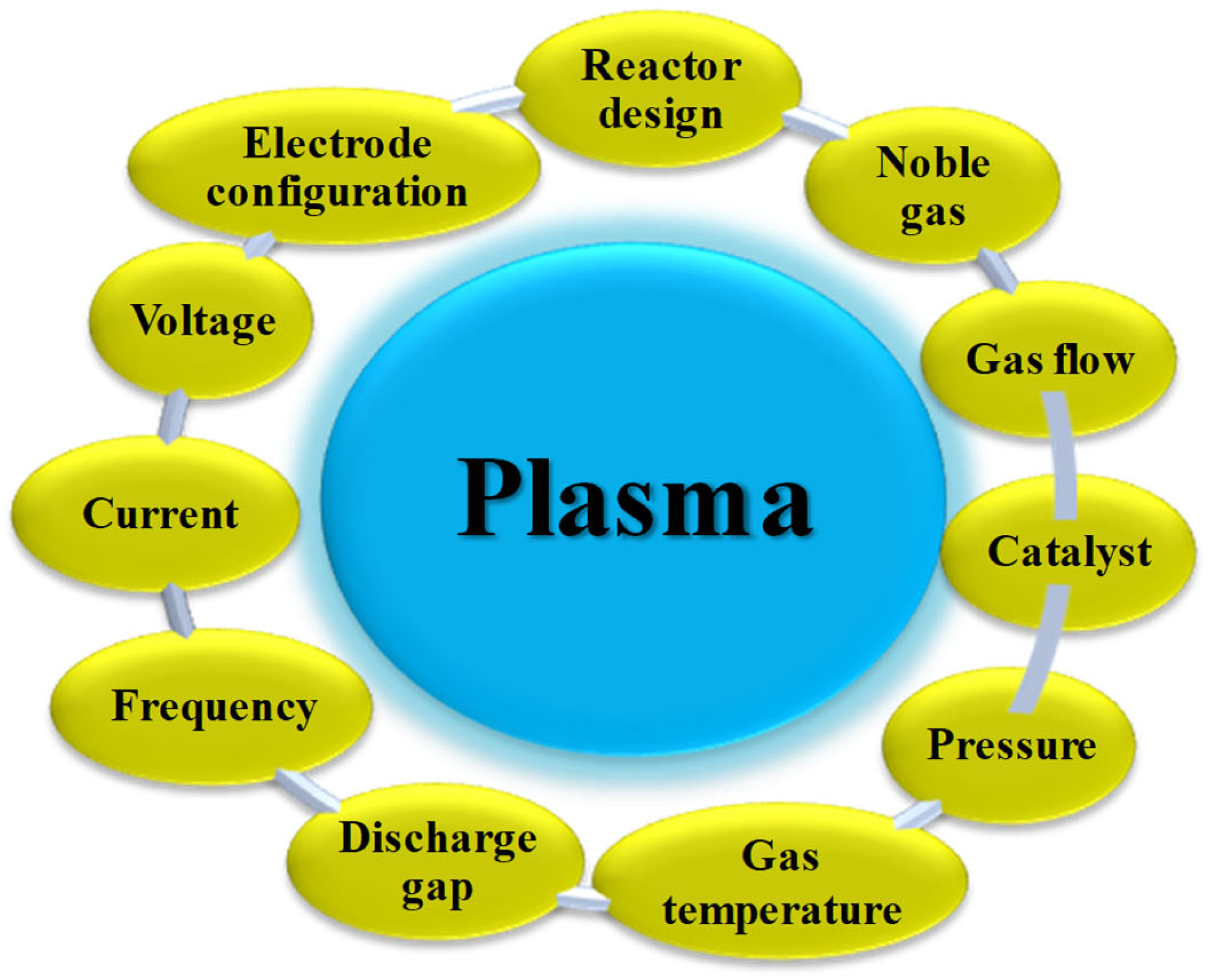

3. Plasma Generation and Properties

4. Plasma-Assisted Methane Conversions

5. Plasma-Induced Surface Engineering Strategies

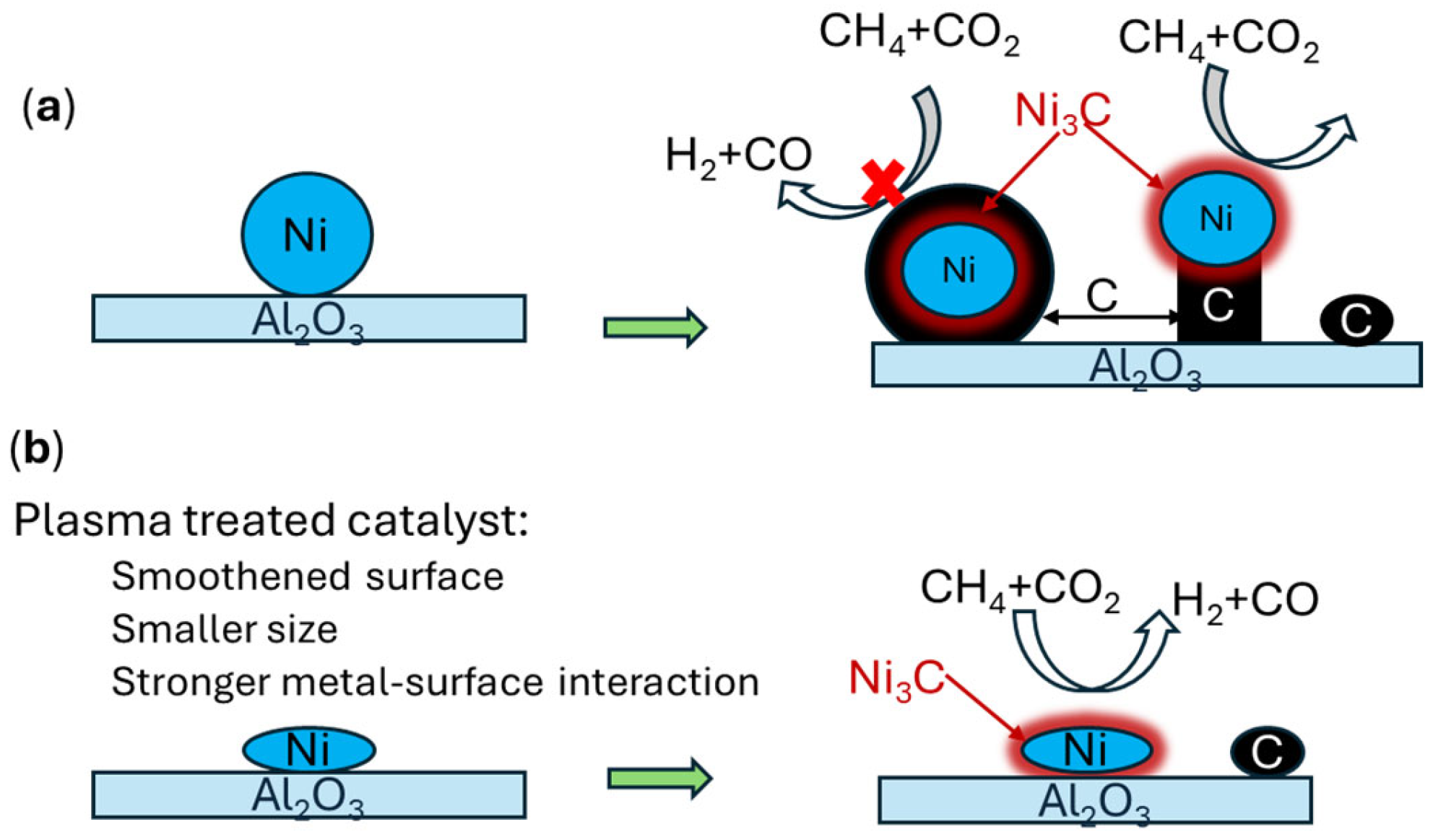

6. Catalytic Methane Conversion Assisted by Low-Temperature Plasma

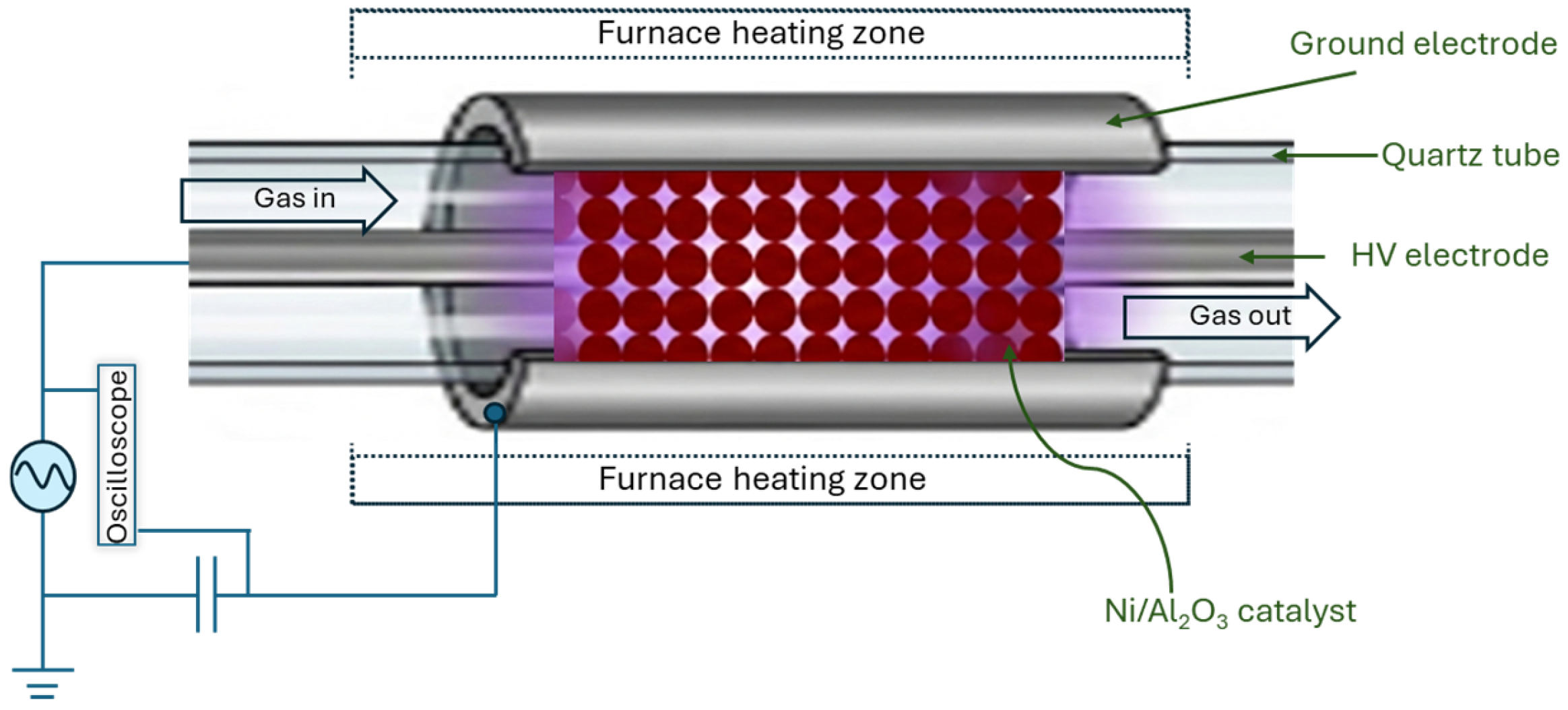

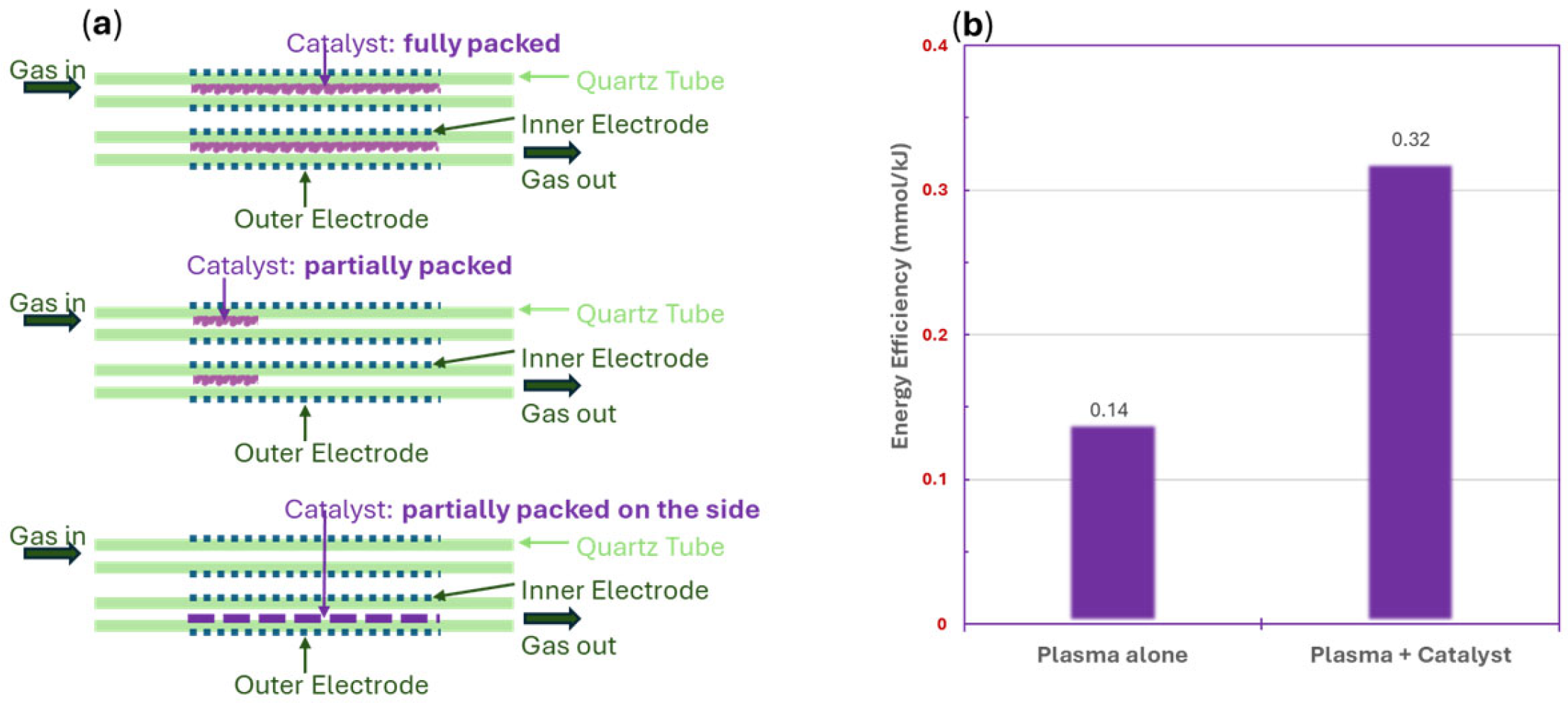

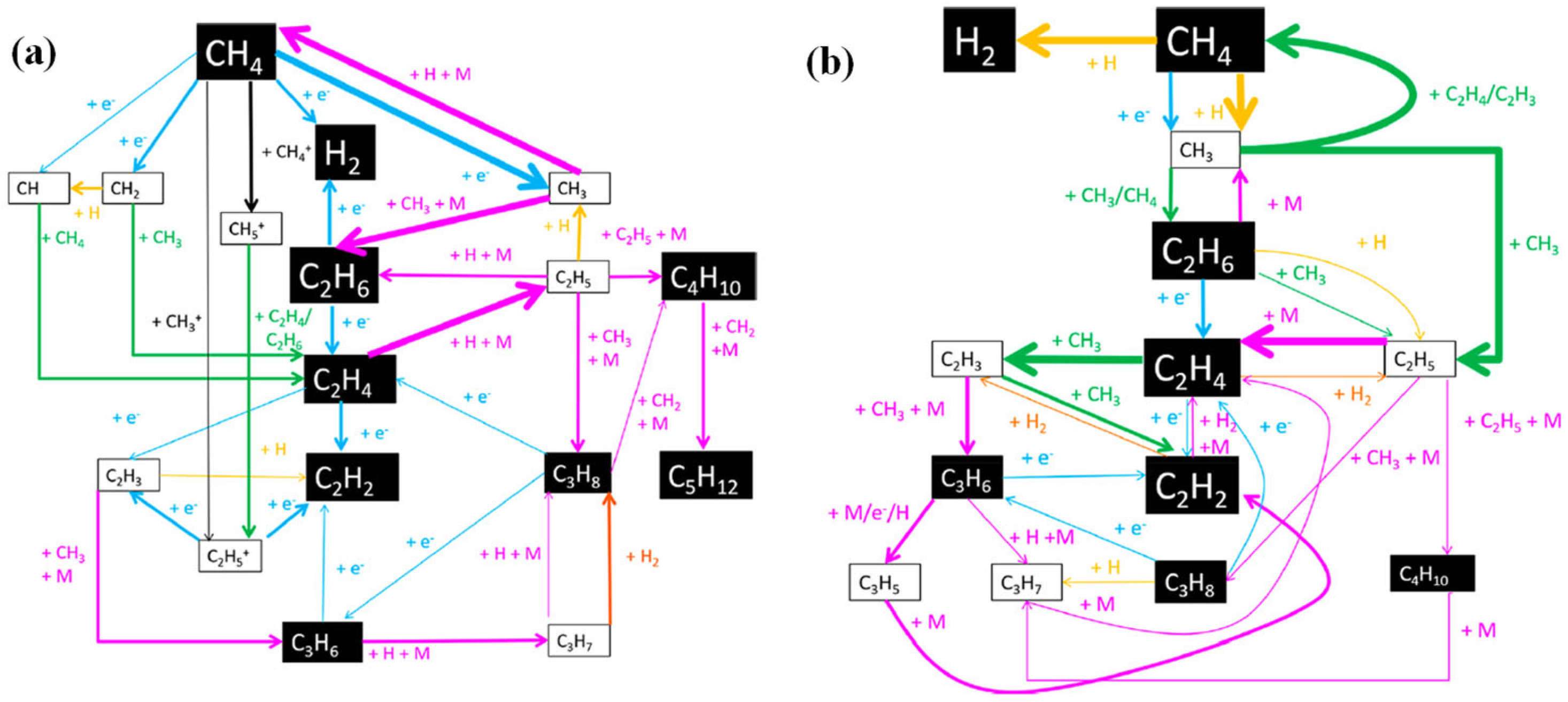

6.1. DBD Plasma-Assisted Conversions

6.1.1. Catalysts Composition

6.1.2. Catalyst Structure and Morphology

| Plasma Reactor Parameters | Feed Gas Composition | Gas Temperature (K) | CH4 Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | Catalyst | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC/pulsed DBD with 0.5 lpm flow rate, 380 W power, and 48 kJ/L SED | 5% CH4 and 95% N2 | >500 | 14.8 | 10.6 (C2H6) 0.7 (C2H4) 0.8 (C2H2) 2 (C-3) | No | [81] |

| Pulsed spark with 5 mm gap, 50 Hz DC, and 5 kV | 100% CH4 | 420 to 460 | 65 | 5 (C2H4) 85 (C2H2) 5 (C-3 to C-5) | No | [77] |

| DBD with 1.2 mm gap, 120 mm length, and 3 kHz | 50% He and 50% CH4 | 373 | 18.4 | 80.7 (C2H6) 6.3 (C2H4) 1.3 (C2H2) 5.3 (C3H8) 6.5 (C-4+) | No | [140] |

| Miro-DBD with 0.4 mm gap, 200 mm length, and 6.4–8.6 kV | 100% CH4 | 448 | 25.1 | 80.3 (C-2/C-3) | No | [85] |

| DBD with 1 mm gap, 50 mL volume, 20 kV, 30 kHz, 2 bar | 20% O2 and 80% CH4 | 353 | 15 | 22 (CH3OH) | No | [141] |

| DBD with 2 mL volume and 1 mm gap | 5% CH4, 5% N2O, and 90% Ar | 330 | 32.2 53.8 (N2O) | 10 (CH3OH) 25 (HCHO) 10 (C2H6) | No | [142] |

| DBD with 4 mm gap and 688 cm2 electrode surface | 75% CH4 and 25% O2 | 301 | 24 74 (O2) | 17 (CH3OH) 5 (HCOOCH3) 16 (HCOOH) 13 (HCHO) 1 (C2H5OH) | No | [143] |

| Micro-DBD with 1 mm ID, twisted metallic electrode, and 75 kHz | 80% N2, 10% CH4, and 10% O2 | 298 | 45 83 (O2) | 17 (CH3OH) 3 (HCHO) 9 (HCOOH) | No | [144] |

| Micro-DBD with 1.5 mm ID and 10 kHz | 50% CH4 and 50% O2 | 283 | 12 | 10 (CH3OH) 15 (HCHO) 14 (HCOOH) | No | [145] |

| DBD with 1.1 mm gap | 67.4% CH4 and 32.6% CO2 | 338 | 55 37 (CO2) | 3 (Alcohols) 8 (Acid) 14 (C2H6) 7.5 (C3H8) 8 (C-4+) | No | [146] |

| DBD with 1 mm gap, 200 mm length, and 25 kHz | 66.8% CH4 and 33.2% CO2 | 333 | 64.3 43.1 (CO2) | 5.2 (CH3COOH) 1 (CH3CH2COOH) 0.3 (CH3OH) 1.8 (C2H5OH) | No | [147] |

| DBD with 140 W power, 7 kHz frequency, and 2.5 mm gap | CH4/air (1:1) | 423 | 25–26 | CH3OH 7.6 (Plasma only) 9 (Pt) 10.7 (Fe2O3) 8.5 (CeO2) | Pt/Fe2O3/CeO2 | [148] |

| DBD with 2.5 mm gap and 300 sccm feed flow rate | CH4/air (1:1) | 423 | 24.5–25.5 | CH3OH 8.5 (Ceramic pellet) 9 (CuO) 10.1 (Fe2O3) 11.3 (Fe2O3–CuO) | CuO/Fe2O3 | [94] |

| DBD with 61 W power and 7 kHz frequency | CH4/air (1:1) | 423 | 35–36 | CH3OH 2.5 (CuO/y-Al2O3) 3.5 (Mo–CuO/y-Al2O3) | CuO/y-Al2O3 Mo–CuO/y-Al2O3 | [139] |

| DBD with 1.2 mm gap, 2.8 W power, and 23 kHz frequency | 6% CH4 in Ar was fed at 20 mL/min | RT | 34 | 70 (C2-C4) | Pd/Al2O3 | [149] |

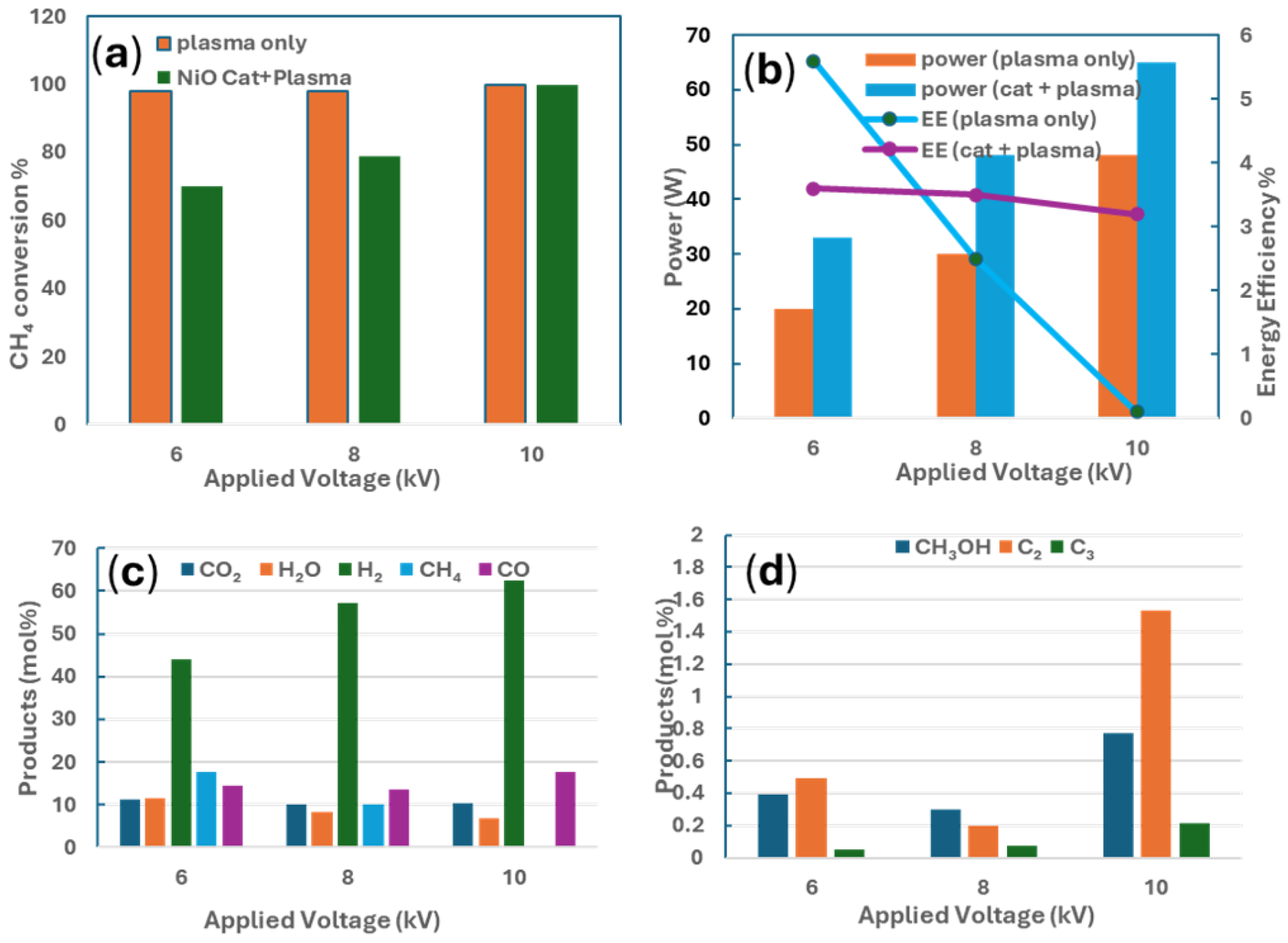

| DBD with voltage of 10 kV and flow rate of 6 mL/min | CH4/O2 (3:1) | RT | 99.9 | 64.7 (H2) 36.36 (CO) | NiO-CaO/Al2O3 | [45] |

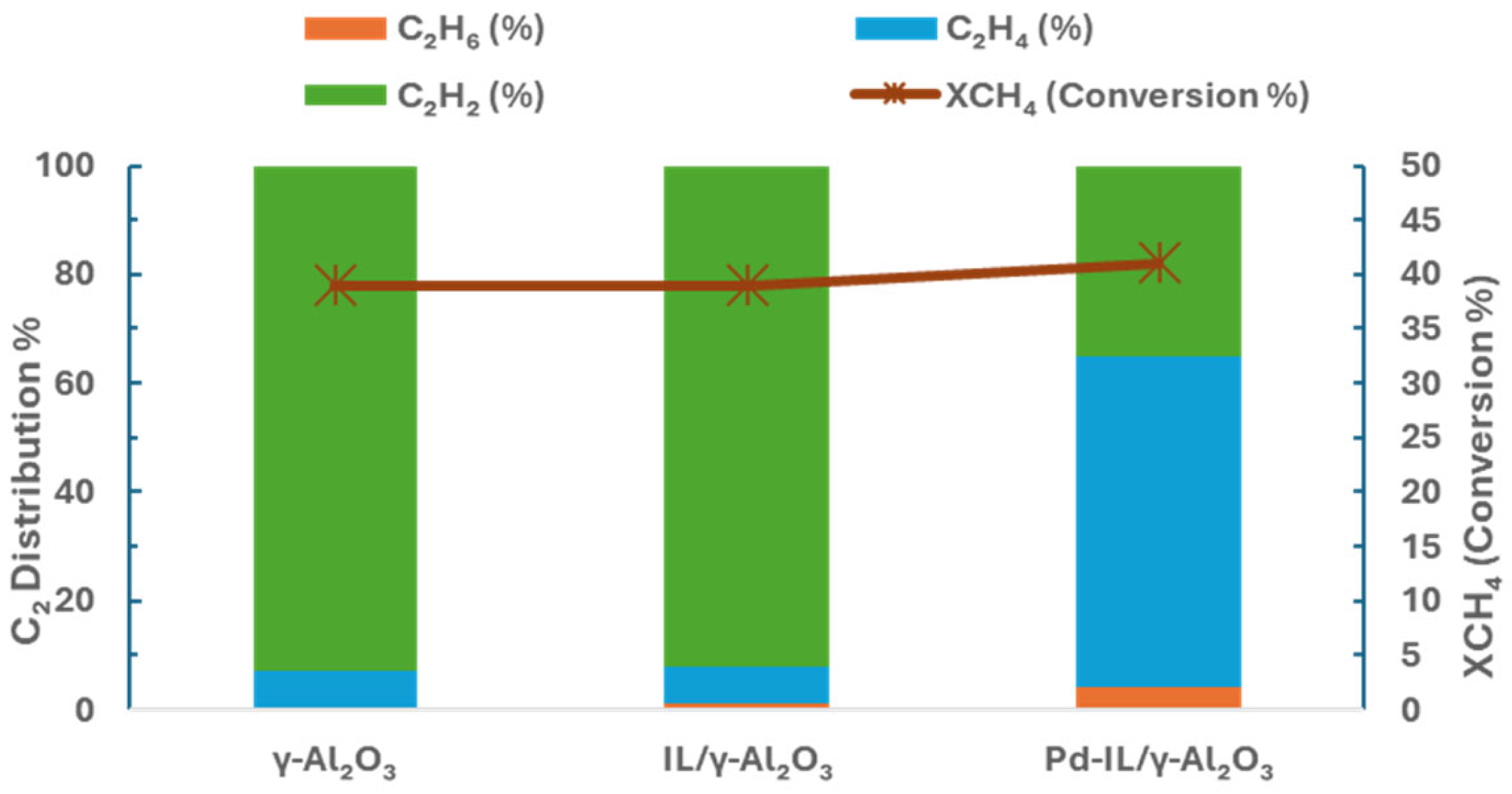

| DBD with 10 mm gap and voltage of 10 kV | CH4/H2 (2:3) | RT | ~40 | 94.6 (C2) 64 (C2H4) | Pd-ionic liquid-γ-Al2O3 | [47] |

| Pulsed spark with 13 mm electrode distance and 11 W discharge power | CH4/H2 | 393 | 74 | 57 (C2H4) | Ag-Pd/SiO2 | [150] |

| DBD with 4.0 mm gap, 7.5 kV voltage, and 4 kHz discharge frequency | 20% CH4 and 10% O2 | <373 | 30.5 | 49.6 (CO) 15 (CO2) 32.6 (CH3OH) | Mn2O3 | [48] |

| Gliding spark discharging plasma with 5.0 mm electrodes gap and discharge frequency of 20 kHz | CH4 | <423 | 75 | 17 (C4) 6 (C6) | No | [151] |

| 2.45 GHz microwave-based plasma | CH4/N2 | 673 | 100 | 76 (H2) 24 (C2H2 and HCN) | No | [152] |

| Single-step plasma | 5% CH4/Helium | <523 | 38 | 32 (C2) 76 (H2) | NaY zeolite | [153] |

| GD plasma with discharge frequency of 4.7–5 kHz | CH4/noble gas/H2/CO2 | ~400 | 36 | 76 (C2) | Cu/Zn/Al2O3 | [154] |

| Coaxial DBD with gap of 3 mm and discharge volume of 11.4 cm3 | CH4/CO2 (1:1) | ~500 | 38.0 21.2 (CO2) | 27.6 (H2) 45.3 (CO) | Ni/γ-Al2O3 | [155] |

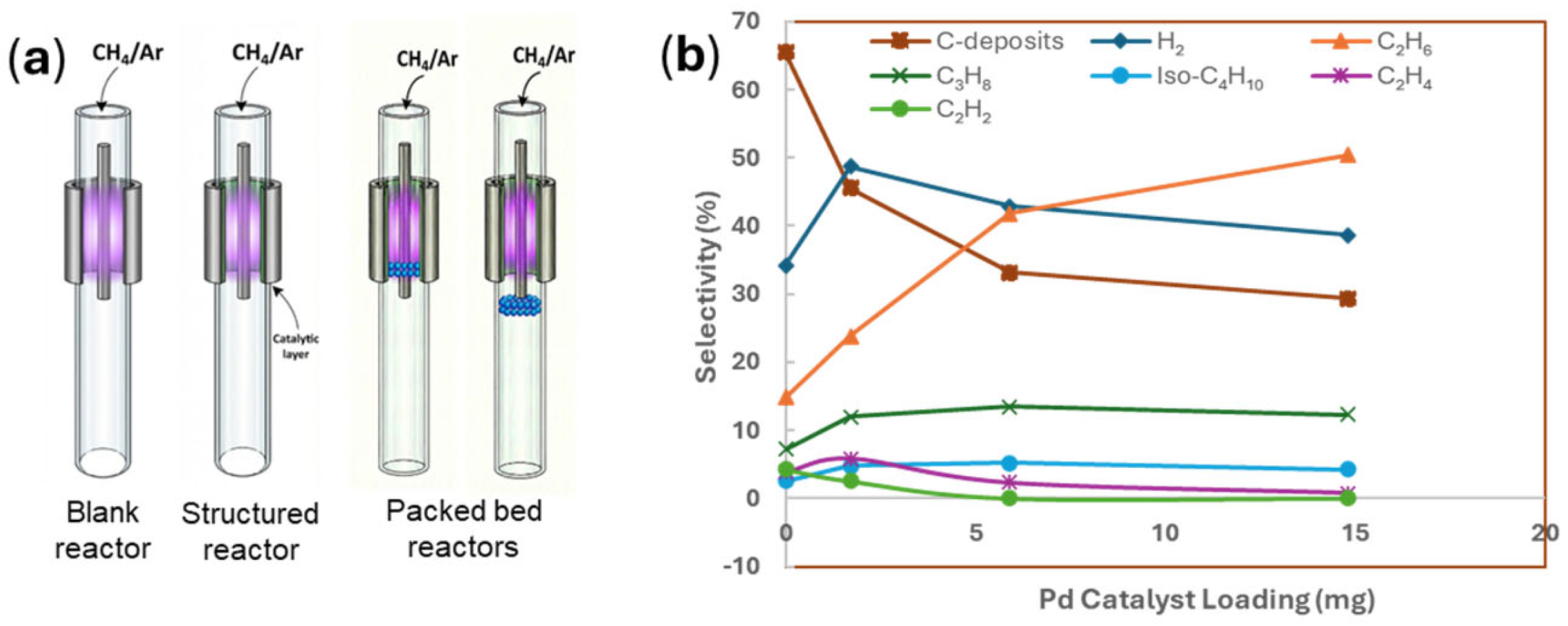

6.1.3. Plasma Reactor Configuration and Packing

6.1.4. Products of Methane Conversion

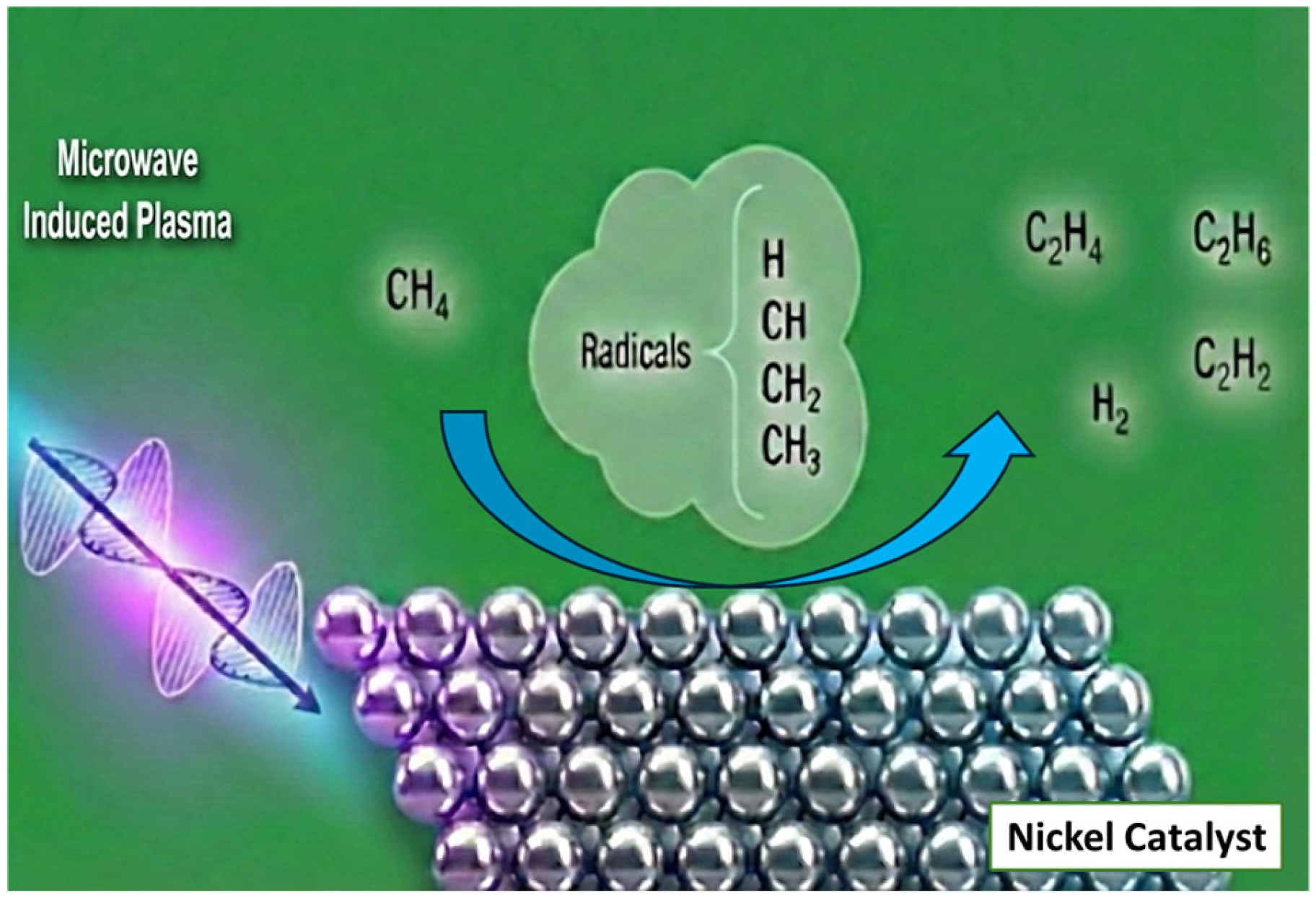

6.2. MW Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Conversions

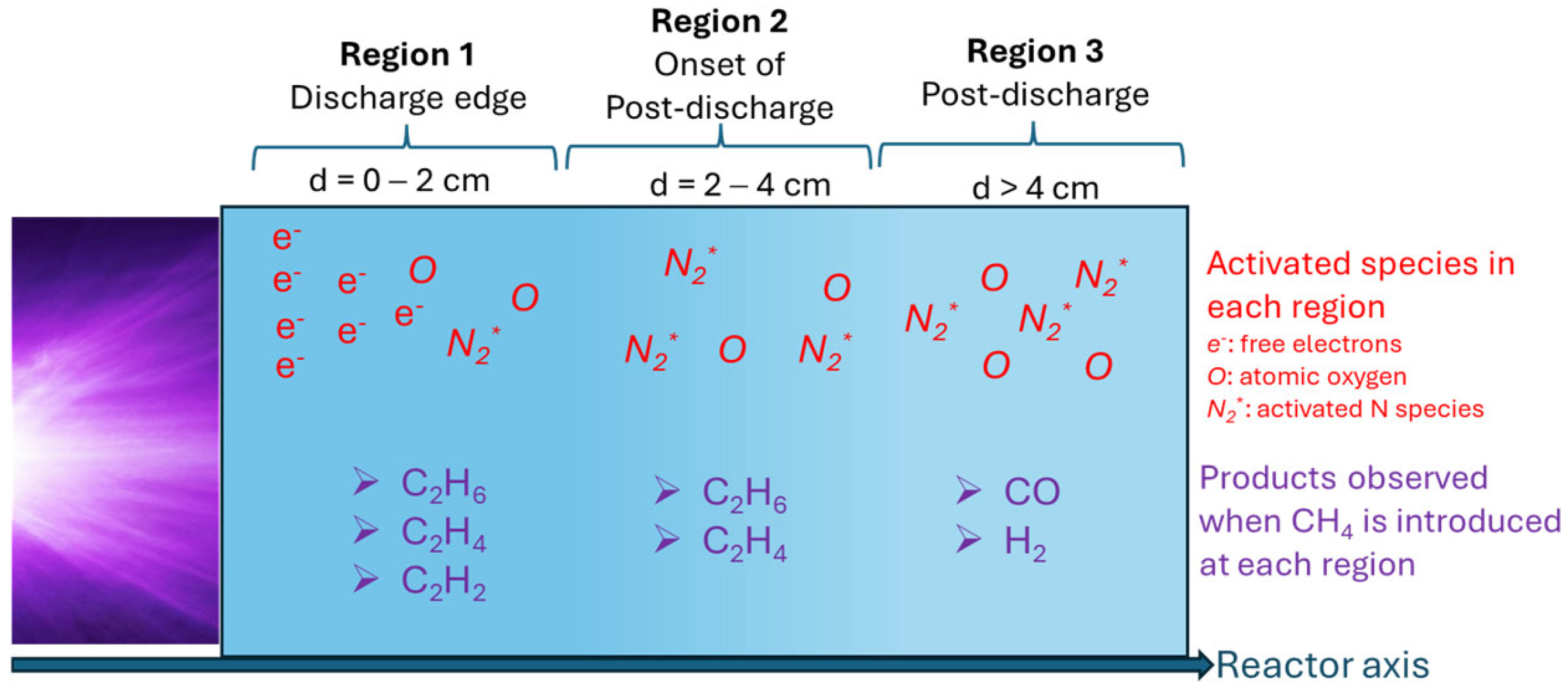

6.3. Catalytic Conversions Assisted by Other Plasmas

7. Reaction Mechanisms at Catalyst Surface

8. Modelling for CH4 Conversion

9. Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saha, D.; Grappe, H.A.; Chakraborty, A.; Orkoulas, G. Postextraction Separation, On-Board Storage, and Catalytic Conversion of Methane in Natural Gas: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11436–11499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwach, P.; Pan, X.; Bao, X. Direct Conversion of Methane to Value-Added Chemicals over Heterogeneous Catalysts: Challenges and Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8497–8520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.R.; Bolaño, T.; Gunnoe, T.B. Catalytic Oxy-Functionalization of Methane and Other Hydrocarbons: Fundamental Advancements and New Strategies. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, M.; Ranocchiari, M.; van Bokhoven, J.A. The Direct Catalytic Oxidation of Methane to Methanol—A Critical Assessment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16464–16483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labinger, J.A.; Bercaw, J.E. Understanding and exploiting C–H bond activation. Nature 2002, 417, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashof, D.A.; Ahuja, D.R. Relative contributions of greenhouse gas emissions to global warming. Nature 1990, 344, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivos-Suarez, A.I.; Szécsényi, À.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Ruiz-Martinez, J.; Pidko, E.A.; Gascon, J. Strategies for the Direct Catalytic Valorization of Methane Using Heterogeneous Catalysis: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2965–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, R.D. An accurate ab initio study of the multipole moments and polarizabilities of methane. Mol. Phys. 1979, 38, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.-G.; Nichols, J.A.; Dixon, D.A. Ionization Potential, Electron Affinity, Electronegativity, Hardness, and Electron Excitation Energy: Molecular Properties from Density Functional Theory Orbital Energies. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 4184–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Meng, X.; Wang, Z.-j.; Liu, H.; Ye, J. Solar-Energy-Mediated Methane Conversion. Joule 2019, 3, 1606–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Ma, D. Methane activation: The past and future. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2580–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, S.D.; Monteleone, G.; Giaconia, A.; Lemonidou, A.A. State-of-the-art catalysts for CH4 steam reforming at low temperature. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 1979–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.; Studt, F.; Kasatkin, I.; Kühl, S.; Hävecker, M.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Zander, S.; Girgsdies, F.; Kurr, P.; Kniep, B.-L.; et al. The Active Site of Methanol Synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 Industrial Catalysts. Science 2012, 336, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Galvan, M.C.; Mota, N.; Ojeda, M.; Rojas, S.; Navarro, R.M.; Fierro, J.L.G. Direct methane conversion routes to chemicals and fuels. Catal. Today 2011, 171, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H. Short history and present trends of Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. Appl. Catal. A 1999, 186, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakov, A.Y.; Chu, W.; Fongarland, P. Advances in the Development of Novel Cobalt Fischer−Tropsch Catalysts for Synthesis of Long-Chain Hydrocarbons and Clean Fuels. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1692–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.; Gray, J.T.; Ha, S.; McEwen, J.-S. Improving Ni Catalysts Using Electric Fields: A DFT and Experimental Study of the Methane Steam Reforming Reaction. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.; Ha, S.; McEwen, J.-S. Elucidating the field influence on the energetics of the methane steam reforming reaction: A density functional theory study. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 195, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagiopoulos, P.N.; Angeli, S.D.; Lemonidou, A.A. Low temperature steam reforming of methane: A combined isotopic and microkinetic study. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 205, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligthart, D.A.J.M.; van Santen, R.A.; Hensen, E.J.M. Influence of particle size on the activity and stability in steam methane reforming of supported Rh nanoparticles. J. Catal. 2011, 280, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hua, L.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, F.; He, L.; et al. Room-Temperature Methane Conversion by Graphene-Confined Single Iron Atoms. Chem 2018, 4, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuno, T.; Zheng, J.; Vjunov, A.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Ortuño, M.A.; Pahls, D.R.; Fulton, J.L.; Camaioni, D.M.; Li, Z.; Ray, D.; et al. Methane Oxidation to Methanol Catalyzed by Cu-Oxo Clusters Stabilized in NU-1000 Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10294–10301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Fung, V.; Jiang, D.-e.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Iwasawa, Y.; Sakata, T.; Nguyen, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Single rhodium atoms anchored in micropores for efficient transformation of methane under mild conditions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, B.E.R.; Vanelderen, P.; Bols, M.L.; Hallaert, S.D.; Böttger, L.H.; Ungur, L.; Pierloot, K.; Schoonheydt, R.A.; Sels, B.F.; Solomon, E.I. The active site of low-temperature methane hydroxylation in iron-containing zeolites. Nature 2016, 536, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, N.; Freakley, S.J.; McVicker, R.U.; Althahban, S.M.; Dimitratos, N.; He, Q.; Morgan, D.J.; Jenkins, R.L.; Willock, D.J.; Taylor, S.H.; et al. Aqueous Au-Pd colloids catalyze selective CH4 oxidation to CH3OH with O2 under mild conditions. Science 2017, 358, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periana, R.A.; Taube, D.J.; Gamble, S.; Taube, H.; Satoh, T.; Fujii, H. Platinum Catalysts for the High-Yield Oxidation of Methane to a Methanol Derivative. Science 1998, 280, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushkevich, V.L.; Palagin, D.; Ranocchiari, M.; van Bokhoven, J.A. Selective anaerobic oxidation of methane enables direct synthesis of methanol. Science 2017, 356, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, B.G.; Konnick, M.M.; Bischof, S.M.; Gustafson, S.J.; Devarajan, D.; Gunsalus, N.; Ess, D.H.; Periana, R.A. Main-Group Compounds Selectively Oxidize Mixtures of Methane, Ethane, and Propane to Alcohol Esters. Science 2014, 343, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fang, G.; Li, G.; Ma, H.; Fan, H.; Yu, L.; Ma, C.; Wu, X.; Deng, D.; Wei, M.; et al. Direct, Nonoxidative Conversion of Methane to Ethylene, Aromatics, and Hydrogen. Science 2014, 344, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Galvan, C.; Melian, M.; Ruiz-Matas, L.; Eslava, J.L.; Navarro, R.M.; Ahmadi, M.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Fierro, J.L.G. Partial Oxidation of Methane to Syngas Over Nickel-Based Catalysts: Influence of Support Type, Addition of Rhodium, and Preparation Method. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh Mostaghimi, A.H.; Al-Attas, T.A.; Kibria, M.G.; Siahrostami, S. A review on electrocatalytic oxidation of methane to oxygenates. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 15575–15590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Ordomsky, V.V.; Khodakov, A.Y. Major routes in the photocatalytic methane conversion into chemicals and fuels under mild conditions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 286, 119913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Park, S.J.; Na, J.G.; Chang, I.S.; Kim, C.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, J.W.; et al. Biocatalytic conversion of methane to methanol as a key step for development of methane-based biorefineries. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Rohani, V.; Fabry, F.; Parakkulam Ramaswamy, A.; Sennour, M.; Fulcheri, L. Direct conversion of CO2 and CH4 into liquid chemicals by plasma-catalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 261, 118228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.; Da Costa, S.; Da Costa, P. Plasma-assisted catalytic oxidation of methane: On the influence of plasma energy deposition and feed composition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 82, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Neyts, E.C. Plasma Technology: An Emerging Technology for Energy Storage. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, H. Chemistry with Methane: Concepts Rather than Recipes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10096–10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasireddy, V.D.B.C.; Likozar, B. Activation and Decomposition of Methane over Cobalt-, Copper-, and Iron-Based Heterogeneous Catalysts for COx-Free Hydrogen and Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Production. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Lee, D.H.; Song, Y.-H. Effect of gas temperature on partial oxidation of methane in plasma reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 13643–13648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, M.R.; Jahanmiri, A.; Mohamadzadeh Shirazi, M.; Hooshmand, N.; Taghvaei, H. Combination of non-thermal plasma and heterogeneous catalysis for methane and hexadecane co-cracking: Effect of voltage and catalyst configuration. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 219, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-B.; Yeo, Y.-K.; Na, B.-K. Conversion of CH4 and CO2 to syngas and higher hydrocarbons using dielectric barrier discharge. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indarto, A. A review of direct methane conversion to methanol by dielectric barrier discharge. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2008, 15, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeckx, R.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma technology—A novel solution for CO2 conversion? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5805–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indarto, A.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, H.; Song, H.K. Decomposition of greenhouse gases by plasma. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2008, 6, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareei, M.; Taghvaei, H.; Azimi, A.; Shahbazi, A.; Mirzaei, M. Catalytic DBD plasma reactor for low temperature partial oxidation of methane: Maximization of synthesis gas and minimization of CO2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 31873–31883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, T. Nonthermal plasma-assisted direct conversion of methane over NiO and MgO catalysts supported on SBA-15. Catal. Today 2018, 299, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Di, L.; Zhou, Q. Methane conversion under cold plasma over Pd-containing ionic liquids immobilized on γ-Al2O3. J. Energy Chem. 2013, 22, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, D.H. Direct methanol synthesis from methane in a plasma-catalyst hybrid system at low temperature using metal oxide-coated glass beads. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.; Saidina Amin, N.A.; Noshadi, I. A Review of Methanol Production from Methane Oxidation via Non-Thermal Plasma Reactor. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2010, 38, 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- Khoja, A.H.; Tahir, M.; Amin, N.A.S. Recent developments in non-thermal catalytic DBD plasma reactor for dry reforming of methane. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 183, 529–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, T.; Okazaki, K. Non-thermal plasma catalysis of methane: Principles, energy efficiency, and applications. Catal. Today 2013, 211, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Song, G.; Li, C.; Lim, K.H.; Das, S.; Sarkar, P.; Liu, L.; Song, H.; Ma, Y.; Lyu, Q.; et al. Recent progress in single-atom catalysts for thermal and plasma-assisted conversion of methane. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 325, 119390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, S.; Sajjadi, B. Non-thermal plasma enhanced catalytic conversion of methane into value added chemicals and fuels. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 97, 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Nguyen, H.M.; Li, W.; Wang, A.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, F.; Jing, L.; Chen, Z.; Gates, I.; et al. Non-thermal plasma-assisted dry reforming of methane: Catalyst design, in situ characterization and hybrid system development. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 145, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Sun, Q. Research Progress on Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Dry Reforming of Methane. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierczyński, P.; Mierczynska-Vasilev, A.; Szynkowska-Jóźwik, M.I.; Ostrikov, K.; Vasilev, K. Plasma-assisted catalysis for CH4 and CO2 conversion. Cataly. Commun. 2023, 180, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandoss, S.; Mohan, H.; Balasubramaniyan, N.; Assadi, A.A.; Khezami, L.; Loganathan, S. A Review Paper on Non-Thermal Plasma Catalysis for CH4 and CO2 Reforming into Value Added Chemicals and Fuels. Catalysts 2025, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliati, L.; Yoshida, H. Photocatalytic conversion of methane. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1592–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Hu, Y.H. Advances in catalytic conversion of methane and carbon dioxide to highly valuable products. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tendero, C.; Tixier, C.; Tristant, P.; Desmaison, J.; Leprince, P. Atmospheric pressure plasmas: A review. Spectrochim. Acta Part B 2006, 61, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulcheri, L.; Dames, E.; Rohani, V. Plasma-based conversion of methane into hydrogen and carbon black. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 50, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U. Dielectric-Barrier Discharges: Their History, Discharge Physics, and Industrial Applications. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2003, 23, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliyalil, H.; Lašič Jurković, D.; Dasireddy, V.D.B.C.; Likozar, B. A review of plasma-assisted catalytic conversion of gaseous carbon dioxide and methane into value-added platform chemicals and fuels. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 27481–27508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseh, M.V.; Khodadadi, A.A.; Mortazavi, Y.; Pourfayaz, F.; Alizadeh, O.; Maghrebi, M. Fast and clean functionalization of carbon nanotubes by dielectric barrier discharge plasma in air compared to acid treatment. Carbon 2010, 48, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.-S.; Chang, Z.; Bu, X.-H. Perspectives on Electron-Assisted Reduction for Preparation of Highly Dispersed Noble Metal Catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-j.; Xu, G.-h.; Wang, T. Non-thermal plasma approaches in CO2 utilization. Fuel Process. Technol. 1999, 58, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, V.; Marotta, E.; Ceretta, C.; Konjević, N.; Ivković, M.; Schiorlin, M.; Paradisi, C. Development and Testing of a Self-Triggered Spark Reactor for Plasma Driven Dry Reforming of Methane. Plasma Processes. Polym. 2014, 11, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ma, X.; Xia, Y.; Xiang, X.; Wu, X. A novel method of production of ethanol by carbon dioxide with steam. Fuel 2015, 158, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Caiola, A.; Bai, X.; Lalsare, A.; Hu, J. Microwave Plasma-Enhanced and Microwave Heated Chemical Reactions. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2020, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Direct Non-oxidative Methane Conversion by Non-thermal Plasma: Experimental Study. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2003, 23, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinov, S.Y.; Lee, H.; Song, H.K.; Na, B.-K. A kinetic study on the conversion of methane to higher hydrocarbons in a radio-frequency discharge. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2004, 21, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafarizal, N.; Albert, A.R.A.; Amirah, A.S.S.; Salwa, O.; Ahmad, M.A.R. Plasma properties of RF magnetron sputtering system using Zn target. AIP Conf. Proc. 2012, 1455, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Neyts, E.; Gijbels, R.; van der Mullen, J. Gas discharge plasmas and their applications. Spectrochimi. Acta B 2002, 57, 609–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltrin, M.E.; Dandy, D.S. Analysis of diamond growth in subatmospheric dc plasma-gun reactors. J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 74, 5803–5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, J.C.; Diamy, A.M.; Hrach, R.; Hrachová, V. Mechanisms of methane decomposition in nitrogen afterglow plasma. Vacuum 1999, 52, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Marafee, A.; Mallinson, R.; Lobban, L. Methane conversion to higher hydrocarbons in a corona discharge over metal oxide catalysts with OH groups. Appl. Catal. A 1997, 164, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kado, S.; Sekine, Y.; Nozaki, T.; Okazaki, K. Diagnosis of atmospheric pressure low temperature plasma and application to high efficient methane conversion. Catal. Today 2004, 89, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Lee, D.H.; Song, Y.-H. Product analysis of methane activation using noble gases in a non-thermal plasma. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 130, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Tu, X. Plasma-assisted methane conversion in an atmospheric pressure dielectric barrier discharge reactor. J. Energy Chem. 2013, 22, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, W.S.; Song, Y.-H. Effect of packing material on methane activation in a dielectric barrier discharge reactor. Phys. Plasmas 2013, 20, 123507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Song, Y.-H.; Kim, K.-T.; Lee, J.-O. Comparative Study of Methane Activation Process by Different Plasma Sources. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2013, 33, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijkers, S.; Aghaei, M.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma-Based CH4 Conversion into Higher Hydrocarbons and H2: Modeling to Reveal the Reaction Mechanisms of Different Plasma Sources. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 7016–7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indarto, A.; Coowanitwong, N.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, H.; Song, H.K. Kinetic modeling of plasma methane conversion in a dielectric barrier discharge. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indarto, A.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, H.; Song, H.K. Effect of additive gases on methane conversion using gliding arc discharge. Energy 2006, 31, 2986–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yan, W.; Ge, W.; Duan, X. Methane conversion into higher hydrocarbons with dielectric barrier discharge micro-plasma reactor. J. Energy Chem. 2013, 22, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamir, F.M.; Matin, N.S.; Jalili, A.H.; Esfarayeni, M.H.; Khodagholi, M.A.; Ahmadi, R. Conversion of methane to methanol in an ac dielectric barrier discharge. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2004, 13, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, K.; Onoe, K.; Takiguchi, Y.; Yamaguchi, T. Conversion of methane by an electric barrier-discharge plasma using an inner electrode with discharge disks set at 5mm intervals. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 95, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliati, L.; Hattori, T.; Yoshida, H. Highly dispersed magnesium oxide species on silica as photoactive sites for photoinduced direct methane coupling and photoluminescence. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, T.; Muto, N.; Kado, S.; Okazaki, K. Dissociation of vibrationally excited methane on Ni catalyst: Part 1. Application to methane steam reforming. Catal. Today 2004, 89, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.-K.; Guo, Z.-G.; Aman-ur-Rehman; Yu, Z.-D.; Ma, J. Tuning effect of inert gas mixing on electron energy distribution function in inductively coupled discharges. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2005, 48, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhão, N.R.; Janeco, A.; Branco, J.B. Influence of Helium on the Conversion of Methane and Carbon dioxide in a Dielectric Barrier Discharge. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2011, 31, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagiopoulos, P.N.; Rogers, J.; Maitre, P.-A.; McCue, A.J.; Bannerman, M.N. Non-Oxidative Coupling of Methane via Plasma-Catalysis Over M/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts (M = Ni, Fe, Rh, Pt and Pd): Impact of Active Metal and Noble Gas Co-Feeding. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2024, 44, 2057–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Tian, D.; Xu, R.; Wong, R.J.; Xi, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Tu, X.; Li, K. Shielded bifunctional nanoreactor enabled tandem catalysis for plasma methane coupling. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Lei, L. Post-Plasma Catalysis for Methane Partial Oxidation to Methanol: Role of the Copper-Promoted Iron Oxide Catalyst. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2010, 33, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyts, E.C. Plasma-Surface Interactions in Plasma Catalysis. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2016, 36, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Huo, P.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Cheng, D.-G.; Liu, C.-J. Structure and reactivity of plasma treated Ni/Al2O3 catalyst for CO2 reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 81, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyts, E.C.; Ostrikov, K.; Sunkara, M.K.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma Catalysis: Synergistic Effects at the Nanoscale. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 13408–13446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-S.; Lee, H.; Na, B.-K.; Song, H.K. Plasma-assisted reduction of supported metal catalyst using atmospheric dielectric-barrier discharge. Catal. Today 2004, 89, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.K.; Choi, J.-W.; Yue, S.H.; Lee, H.; Na, B.-K. Synthesis gas production via dielectric barrier discharge over Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Catal. Today 2004, 89, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiev, R.S.; Sladkovskiy, D.A.; Semikin, K.V.; Murzin, D.Y.; Rebrov, E.V. Non-Thermal Plasma for Process and Energy Intensification in Dry Reforming of Methane. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, A.H.; Azad, A.K.; Saleem, F.; Khan, B.A.; Naqvi, S.R.; Mehran, M.T.; Amin, N.A.S. Hydrogen Production from Methane Cracking in Dielectric Barrier Discharge Catalytic Plasma Reactor Using a Nanocatalyst. Energies 2020, 13, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Mukhriza, T.; Liu, X.; Greco, P.P.; Chiremba, E. A study on CO2 and CH4 conversion to synthesis gas and higher hydrocarbons by the combination of catalysts and dielectric-barrier discharges. Appl. Catal. A 2015, 502, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Tan, S.; Dong, L.; Li, S.; Chen, H. LaNiO3@SiO2 core–shell nano-particles for the dry reforming of CH4 in the dielectric barrier discharge plasma. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 11360–11367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahemi, N.; Haghighi, M.; Babaluo, A.A.; Allahyari, S.; Estifaee, P.; Jafari, M.F. Plasma-Assisted Dispersion of Bimetallic Ni–Co over Al2O3–ZrO2 for CO2 Reforming of Methane: Influence of Voltage on Catalytic Properties. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xu, J.-Q.; Chu, W. CO2 reforming of methane over Mn promoted Ni/Al2O3 catalyst treated by N2 glow discharge plasma. Catal. Today 2015, 256, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Tian, H.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Gong, J. Dry reforming of methane over Ni/La2O3 nanorod catalysts with stabilized Ni nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahemi, N.; Haghighi, M.; Babaluo, A.A.; Jafari, M.F.; Estifaee, P. CO2 Reforming of CH4 Over CeO2-Doped Ni/Al2O3 Nanocatalyst Treated by Non-Thermal Plasma. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 13, 4896–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahemi, N.; Haghighi, M.; Babaluo, A.A.; Jafari, M.F.; Estifaee, P. Synthesis and physicochemical characterizations of Ni/Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocatalyst prepared via impregnation method and treated with non-thermal plasma for CO2 reforming of CH4. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estifaee, P.; Haghighi, M.; Babaluo, A.A.; Rahemi, N.; Jafari, M.F. The beneficial use of non-thermal plasma in synthesis of Ni/Al2O3–MgO nanocatalyst used in hydrogen production from reforming of CH4/CO2 greenhouse gases. J. Power Sources 2014, 257, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhab, I.; Amin, N.A.S.; Asmadi, M. Dry reforming of methane over oil palm shell activated carbon and ZSM-5 supported cobalt catalysts. Int. J. Green Energy 2017, 14, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Jin, Y. Dry reforming of methane in an atmospheric pressure plasma fluidized bed with Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, B.M.; Bulushev, D.A.; Beloshapkin, S.; Ross, J.R.H. The effect of potassium on the activity and stability of Ni–MgO–ZrO2 catalysts for the dry reforming of methane to give synthesis gas. Catal. Today 2011, 178, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, B.; Abd Ghani, N.A.; Vo, D.-V.N. Recent advances in dry reforming of methane over Ni-based catalysts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ning, N.; Tang, S.-Y.; Qian, C.; Zhou, S. Plasma-Assisted Dry Reforming of Methane over the Ti–Ni Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 2626–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istadi; Amin, N.A.S. Co-generation of synthesis gas and C2+ hydrocarbons from methane and carbon dioxide in a hybrid catalytic-plasma reactor: A review. Fuel 2006, 85, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sm, N.B.; Rao, M.U.; Madras, G.; Subrahmanyam, C. Solution Combustion Synthesized Ni-Based Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane Reaction Using Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202500048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawdhury, P.; Wang, Y.; Ray, D.; Mathieu, S.; Wang, N.; Harding, J.; Bin, F.; Tu, X.; Subrahmanyam, C. A promising plasma-catalytic approach towards single-step methane conversion to oxygenates at room temperature. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 284, 119735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indarto, A.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, H.; Song, H.K. A Brief Catalyst Study on Direct Methane Conversion Using a Dielectric Barrier Discharge. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2007, 54, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Yashima, T. Small Amounts of Rh-Promoted Ni Catalysts for Methane Reforming with CO2. Catal. Lett. 2003, 89, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, N.C.D.; Jeong, H.W.; Han, D.S.; Park, H.; Lee, J.-J. Facile Electrochemical Synthesis of Highly Efficient Copper–Cobalt Oxide Nanostructures for Oxygen Evolution Reactions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 026510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, N.C.D.; Lee, J.-J. Intercalation-type electrodes of copper–cobalt oxides for high-energy-density supercapacitors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 861, 113947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraleedharan Nair, M.; Kaliaguine, S. Structured catalysts for dry reforming of methane. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 4049–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Bai, M.; Li, X.; Long, H.; Shang, S.; Yin, Y.; Dai, X. CH4–CO2 reforming by plasma—Challenges and opportunities. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Dalai, A.K. Development of stable bimetallic catalysts for carbon dioxide reforming of methane. J. Catal. 2007, 249, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, A.H.; Tahir, M.; Amin, N.A.S.; Javed, A.; Mehran, M.T. Kinetic study of dry reforming of methane using hybrid DBD plasma reactor over La2O3 co-supported Ni/MgAl2O4 catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 12256–12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Lei, L. Application of in-plasma catalysis and post-plasma catalysis for methane partial oxidation to methanol over a Fe2O3-CuO/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2010, 19, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.H.; Goujard, V.; Tatibouët, J.M.; Batiot-Dupeyrat, C. Activation of methane and carbon dioxide in a dielectric-barrier discharge-plasma reactor to produce hydrocarbons—Influence of La2O3/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Catal. Today 2011, 171, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, M.; Gonçalves, R.d.F.; Leite, E.R.; Raubach, C.W.; Carreño, N.L.V.; Probst, L.F.D.; Longo, E.; Fajardo, H.V. Gadolinium-doped cerium oxide nanorods: Novel active catalysts for ethanol reforming. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Tahir, B.; Amin, N.A.S. Gold-nanoparticle-modified TiO2 nanowires for plasmon-enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction with H2 under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, N.C.D.; Choi, S.Y.; Jeong, H.W.; Lee, J.-J.; Park, H. Stand-alone photoconversion of carbon dioxide on copper oxide wire arrays powered by tungsten trioxide/dye-sensitized solar cell dual absorbers. Nano Energy 2016, 25, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Dielectric barrier discharge plasma for preparation of Ni-based catalysts with enhanced coke resistance: Current status and perspective. Catal. Today 2015, 256, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C. Influence of copper nanowires grown in a dielectric layer on the performance of dielectric barrier discharge. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2017, 35, 010603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.; De Pasquale, L.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Genovese, C. Synergistic effects of light and plasma catalysis on Au-modified TiO2 nanotube arrays for enhanced non-oxidative coupling of methane. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 3725–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Tan, S.; Dong, L.; Li, S.; Chen, H. Silica-coated LaNiO3 nanoparticles for non-thermal plasma assisted dry reforming of methane: Experimental and kinetic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 265, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, Y.; Shariatinia, Z.; Bahadoran, F. High catalytic activity and stability of ZnLaAlO4 supported Ni, Pt and Ru nanocatalysts applied in the dry, steam and combined dry-steam reforming of methane. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 299, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-F.; Ye, D.-Q.; Chen, K.-F.; He, J.-C.; Chen, W.-L. Toluene decomposition using a wire-plate dielectric barrier discharge reactor with manganese oxide catalyst in situ. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 245, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameshima, S.; Mizukami, R.; Yamazaki, T.; Prananto, L.A.; Nozaki, T. Interfacial reactions between DBD and porous catalyst in dry methane reforming. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Mao, D.; Han, L.; Yu, J. Effect of preparation method on performance of Cu–Fe/SiO2 catalysts for higher alcohols synthesis from syngas. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 55233–55239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, X.-W.; Chen, L.; Lei, L.-C. Direct Oxidation of Methane to Methanol Over Cu-Based Catalyst in an AC Dielectric Barrier Discharge. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2011, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji Tarverdi, M.S.; Mortazavi, Y.; Khodadadi, A.A.; Mohajerzadeh, S. Synergetic Effects of Plasma, Temperature and Diluant on Nonoxidative Conversion of Methane to C2+ Hydrocarbons in a Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2005, 24, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.M.; Xue, B.; Kogelschatz, U.; Eliasson, B. Partial Oxidation of Methane to Methanol with Oxygen or Air in a Nonequilibrium Discharge Plasma. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 1998, 18, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Tanabe, S.; Okitsu, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Suib, S.L. Selective Oxidation of Methane to Methanol and Formaldehyde with Nitrous Oxide in a Dielectric-Barrier Discharge−Plasma Reactor. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 5304–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, D.W.; Lobban, L.L.; Mallinson, R.G. The direct partial oxidation of methane to organic oxygenates using a dielectric barrier discharge reactor as a catalytic reactor analog. Catal. Today 2001, 71, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, T.; Hattori, A.; Okazaki, K. Partial oxidation of methane using a microscale non-equilibrium plasma reactor. Catal. Today 2004, 98, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, T.; Ağıral, A.; Yuzawa, S.; Han Gardeniers, J.G.E.; Okazaki, K. A single step methane conversion into synthetic fuels using microplasma reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Eliasson, B.; Wang, Y. Synthesis of Oxygenates and Higher Hydrocarbons Directly from Methane and Carbon Dioxide Using Dielectric-Barrier Discharges: Product Distribution. Energy Fuels 2002, 16, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Eliasson, B. Plasma methane conversion in the presence of carbon dioxide using dielectric-barrier discharges. Fuel Process. Technol. 2003, 83, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, X.-W.; Huang, L.; Lei, L.-C. Partial oxidation of methane with air for methanol production in a post-plasma catalytic system. Chem. Eng. Process. 2009, 48, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moncada, N.; van Rooij, G.; Cents, T.; Lefferts, L. Catalyst-assisted DBD plasma for coupling of methane: Minimizing carbon-deposits by structured reactors. Catal. Today 2021, 369, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.J.; Li, X.S.; Wang, H.; Shi, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, A.M. Oxygen-Free Conversion of Methane to Ethylene in a Plasma-Followed-by-Catalyst (PFC) Reactor. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2008, 10, 600–604. [Google Scholar]

- Bidgoli, A.M.; Ghorbanzadeh, A.; Lotfalipour, R.; Roustaei, E.; Zakavi, M. Gliding spark plasma: Physical principles and performance in direct pyrolysis of methane. Energy 2017, 125, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facas, G.G.; Calabrese, G.; Schüller, N.; Schreiber, D.; Zennegg, M.; Radoiu, M.; Eggenschwiler, P.D. Hydrogen production by microwave plasma CH4 pyrolysis: Characterization via optical emission spectroscopy and response surface methodology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-J.; Mallinson, R.; Lobban, L. Nonoxidative Methane Conversion to Acetylene over Zeolite in a Low Temperature Plasma. J. Catal. 1998, 179, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Szałowski, K.; Górska, A.; Młotek, M. Plasma-catalytic Conversion of Methane by DBD and Gliding Discharges. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2006, 9, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Whitehead, J.C. Plasma-catalytic dry reforming of methane in an atmospheric dielectric barrier discharge: Understanding the synergistic effect at low temperature. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 125, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheraslani, M.; Gardeniers, H. Plasma Catalytic Conversion of CH4 to Alkanes, Olefins and H2 in a Packed Bed DBD Reactor. Processes 2020, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Bruggeman, P.J. Investigation of the Mechanisms Underpinning Plasma-Catalyst Interaction for the Conversion of Methane to Oxygenates. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2022, 42, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawdhury, P.; Rawool, S.B.; Rao, M.U.; Subrahmanyam, C. Methane decomposition by plasma-packed bed non-thermal plasma reactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 258, 117779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, J.; Chen, G.; Xiang, Y. Dual-Bed Plasma/Catalytic Synergy for Methane Transformation into Aromatics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 2516–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawdhury, P.; Ray, D.; Vinodkumar, T.; Subrahmanyam, C. Catalytic DBD plasma approach for methane partial oxidation to methanol under ambient conditions. Catal. Today 2019, 337, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, M.; Bae, J.; Hong, D.-Y.; Park, Y.-K.; Hwang, Y.K.; Jeong, M.-G.; Kim, Y.D. Plasma-Assisted Non-Oxidative Conversion of Methane over Mo/HZSM-5 Catalyst in DBD Reactor. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Castro, G.J.; Scotto d’Apollonia, A.; Cho, Y.; Hicks, J.C. Plasma-Catalyst Synergy in the One-Pot Nonthermal Plasma-Assisted Synthesis of Aromatics from Methane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 18394–18402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M.; Akan, T. Arc-Free Atmospheric Pressure Cold Plasma Jets: A Review. Plasma Process. Polym. 2007, 4, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Baek, Y.; Moon, S.-K.; Kim, Y.C. Oxidative coupling of methane with microwave and RF plasma catalytic reaction over transitional metals loaded on ZSM-5. Catal. Today 2002, 74, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagazoe, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kimuro, H.; Onoe, K. Characteristics of Methane Conversion under Combined Reactions of Solid Catalyst with Microwave Plasma. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2006, 39, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintze, M.; Magureanu, M. Methane Conversion into Aromatics in a Direct Plasma-Catalytic Process. J. Catal. 2002, 206, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-F.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chang, W.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-M. Methane steam reforming for producing hydrogen in an atmospheric-pressure microwave plasma reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumghar, A.; Legrand, J.C.; Diamy, A.M.; Turillon, N. Methane conversion by an air microwave plasma. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 1995, 15, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoe, K.; Fujie, A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Hatano, Y. Selective synthesis of acetylene from methane by microwave plasma reactions. Fuel 1997, 76, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dai, B.; Zhu, A.; Gong, W.; Liu, C. The simultaneous activation of methane and carbon dioxide to C2 hydrocarbons under pulse corona plasma over La2O3/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Catal. Today 2002, 72, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delikonstantis, E.; Scapinello, M.; Stefanidis, G.D. Low energy cost conversion of methane to ethylene in a hybrid plasma-catalytic reactor system. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 176, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, P.A.; Abbas, A.; Daud, W.M.W. Insight into catalytic reduction of CO2: Catalysis and reactor design. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchia, S. Fuel processing activities at European level: A panoramic overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 17953–17968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliyalil, H.; Filipic, G.; Cvelbar, U. Selective Plasma Etching of Polyphenolic Composite in O2/Ar Plasma for Improvement of Material Tracking Properties. Plasma Process. Polym. 2016, 13, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.; Steen, P.G.; Graham, W.G. Atomic oxygen surface loss coefficient measurements in a capacitive/inductive radio-frequency plasma. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.-S.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Bhatia, S. Utilization of Greenhouse Gases through Dry Reforming: Screening of Nickel-Based Bimetallic Catalysts and Kinetic Studies. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, A.M.; Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Leys, C. Non-thermal plasmas for non-catalytic and catalytic VOC abatement. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 195, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-R.; Neyts, E.C.; Bogaerts, A. Influence of the Material Dielectric Constant on Plasma Generation inside Catalyst Pores. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 25923–25934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegemann, D.; Navascués, P.; Snoeckx, R. Plasma gas conversion in non-equilibrium conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 100, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourali, N.; Vasilev, M.; Abiev, R.; Rebrov, E.V. Development of a microkinetic model for non-oxidative coupling of methane over a Cu catalyst in a non-thermal plasma reactor. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 395204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, Q.; Sun, J.; Liu, N.; Liu, B.; Zhang, M. From electric field catalysis to plasma catalysis: A combined experimental study and kinetic modeling to understand the synergistic effects in methane dry reforming. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 161015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, P.-A.; Bieniek, M.S.; Kechagiopoulos, P.N. Plasma-Catalysis of Nonoxidative Methane Coupling: A Dynamic Investigation of Plasma and Surface Microkinetics over Ni(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 19987–20003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Li, X.-S.; Liu, J.-L.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, A.-M. Kinetics study on carbon dioxide reforming of methane in kilohertz spark-discharge plasma. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 264, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-G.; Tan, S.-Y.; Dong, L.-C.; Li, S.-B.; Chen, H.-M.; Wei, S.-A. Experimental and kinetic investigation of the plasma catalytic dry reforming of methane over perovskite LaNiO3 nanoparticles. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 137, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Mei, D.H.; Shen, Z.; Tu, X. Nonoxidative Conversion of Methane in a Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor: Prediction of Reaction Performance Based on Neural Network Model. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 10686–10693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Marafee, A.; Hill, B.; Xu, G.; Mallinson, R.; Lobban, L. Oxidative Coupling of Methane with ac and dc Corona Discharges. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996, 35, 3295–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.-C.; Chang, M.-B. Review of catalysis and plasma performance on dry reforming of CH4 and possible synergistic effects. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delikonstantis, E.; Scapinello, M.; Stefanidis, G.D. Investigating the Plasma-Assisted and Thermal Catalytic Dry Methane Reforming for Syngas Production: Process Design, Simulation and Evaluation. Energies 2017, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C. Plasma–catalysis: The known knowns, the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2016, 49, 243001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, D.W.; Lobban, L.L.; Mallinson, R.G. Production of Organic Oxygenates in the Partial Oxidation of Methane in a Silent Electric Discharge Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.M.; Xue, B.; Kogelschatz, U.; Eliasson, B. Nonequilibrium Plasma Reforming of Greenhouse Gases to Synthesis Gas. Energy Fuels 1998, 12, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulamanti, A.; Moya, J.A. Production costs of the chemical industry in the EU and other countries: Ammonia, methanol and light olefins. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methane Conversions | ΔG0 at 298 K (kJ mol−1) | Equation # |

|---|---|---|

| 50.7 | (1) | |

| 68.6 | (2) | |

| 434.0 | (3) | |

| −320.0 | (4) | |

| −288.0 | (5) | |

| 142.0 | (6) | |

| −165.0 | (7) | |

| −92.0 | (8) | |

| 171.0 | (9) | |

| 71.1 | (10) | |

| −36.0 | (11) | |

| −126.4 | (12) | |

| −104.0 | (13) | |

| 204.0 | (14) |

| a Reactor | DBD | CD | GD | MW | RF | GAD | SD | AD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermo-Type | Non-Equilibrium (Te ≠ Tgas) | Equilibrium (Te = Tgas) | ||||||

| Electron density (cm−3) | 1012 to 1015 | 109 to 1013 | 108 to 1011 | ~1016 | ~1010 | 1014 to 1015 | 1014 to 1015 | 1015 to 1019 |

| Electron temp (eV) | 1 to 30 | 1~5 | 0.5 to 2 | 0.9 | 2–2.5 | 1.4 to 2.1 | - | 1 to 10 |

| Current (A) | 1 to 50 | 10–5 | - | - | - | 0.1 to 50 | 20 to 30 | 30 to 300,000 |

| Voltage (kV)/freq. | 5 to 25 | 10 to 50 | 10 V/cm | 2.45 GHz | 13.56 MHz | 0.5 to 4 | 5 to 15 | 10 to 100 |

| Gas temp (K) | 300 to 500 | ~400 | RT | RT | RT | >1000 | 400 to 1000 | 5 103 to 104 |

| Pressure (bar) | 1 | 1 | <10 mbar | 1 | Low pressure | High pressure | High pressure | High pressure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nath, N.C.D.; Du, G. Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Conversion of Methane at Low Temperatures. Catalysts 2026, 16, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020165

Nath NCD, Du G. Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Conversion of Methane at Low Temperatures. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020165

Chicago/Turabian StyleNath, Narayan Chandra Deb, and Guodong Du. 2026. "Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Conversion of Methane at Low Temperatures" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020165

APA StyleNath, N. C. D., & Du, G. (2026). Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Conversion of Methane at Low Temperatures. Catalysts, 16(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020165