Abstract

The electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 in the gas phase has been carried out in a PEM type cell. The influence of the support material of the macroporous substrate (MPS) and the binding agent used to join the catalytic layer (CL) with the MPS has been analyzed. Three types of carbon paper used as support for the MPS have been compared and the influence of the use of Nafion® as a binding agent has been analyzed. Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T have allowed similar results in the CO2 conversion rate to be obtained, although significant differences are observed regarding the selectivity of the process. Regarding the use of binding agent, it has been observed that it is essential to be able to carry out the electroreduction process and, although its concentration does not seem to greatly affect the rate of CO2 conversion, it does influence the selectivity of the process.

1. Introduction

One of the most pressing concerns facing contemporary society is climate change, primarily driven by anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels for transportation and electricity generation, as well as from industrial activities, deforestation, and agriculture [1,2]. The electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 represents a promising strategy for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions while simultaneously enabling the production of valuable chemicals and fuels [3,4]. This process entails the use of an electrocatalyst to facilitate the conversion of CO2 into various chemical products, including formic acid [4,5], methane [6], and ethylene [7,8]. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction is accomplished by applying an electrical potential between two electrodes composed of electrocatalytic materials, resulting in an anodic reaction (typically water oxidation) and a cathodic reaction involving the reduction of CO2. The cathodic electrocatalyst serves as a mediator between CO2 molecules and electrons, thereby enabling the reaction to proceed at a reduced energy cost.

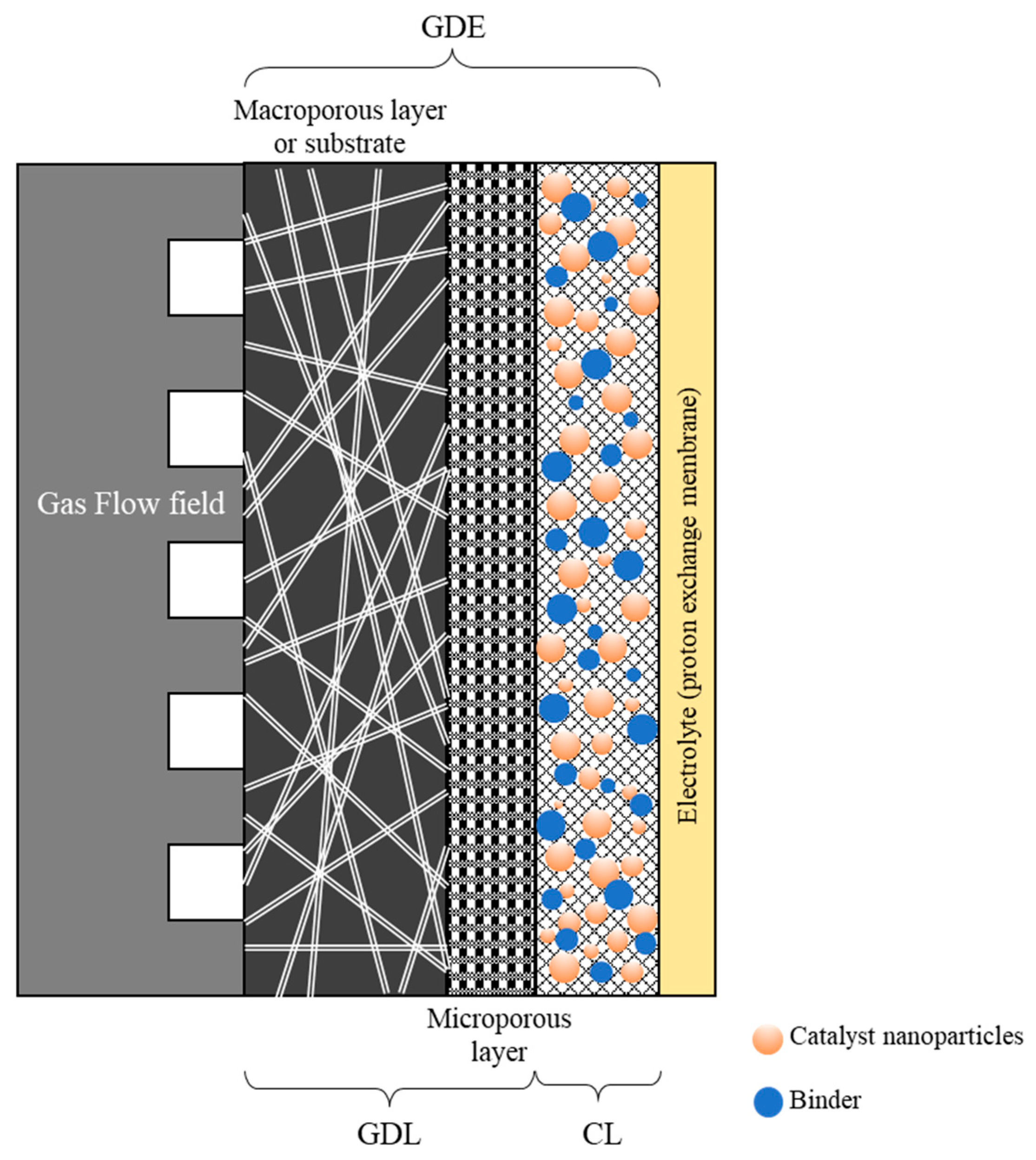

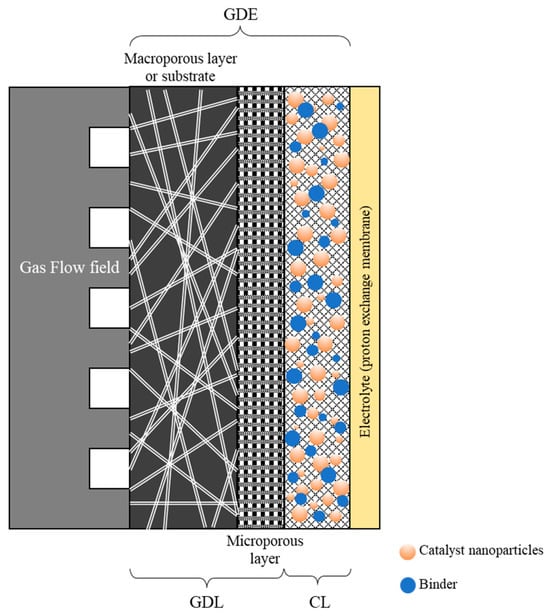

In recent years, flow cells have increasingly supplanted traditional H-type liquid cells, addressing their limitations in gas diffusion and maximum achievable current density [4,9]. Gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) are essential components in many electrochemical CO2 reduction flow cells. The most commonly reported GDE architecture in the literature features a layered structure, in which the catalyst is incorporated within an ionomer/polymer matrix to form the catalytic layer (CL), which is deposited atop a hydrophobic gas diffusion layer (GDL) [4,10] (Figure 1). Nafion® (Wilmington, DE, USA) (a perfluorinated polymer) and PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) are typically employed as binding agents in these systems. Nafion®, owing to its hydrophilic nature, enhances electrode wetting and facilitates proton conduction, whereas PTFE promotes the formation of larger pores, thereby improving CO2 transport. The use of Nafion® as a binder has been extensively investigated in fuel cell applications, as it increases the electrochemical surface area within the catalyst layer and strengthens the interface between the membrane and the electrode, ultimately reducing cell resistance [11,12]. The GDL itself consists of a macroporous substrate, which may be supplemented with a microporous layer (MPL).

Figure 1.

Layered structure of a typical gas diffusion electrode assembled in a PEM type cell with a membrane-based electrolyte.

The gas diffusion layer (GDL) in gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) fulfills a multifaceted role in the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. It provides an extensive surface area for gas diffusion, thereby promoting efficient mass transfer of reactants [4,13]. Additionally, the electrical conductivity of the GDL facilitates the rapid transfer of electrons from the electrocatalyst to the external circuit [4], ensuring that reduction reactions proceed efficiently and with minimal energy losses. Furthermore, the GDL offers mechanical support to the electrocatalyst [14,15], thereby enhancing its stability and longevity during electrochemical reactions. Consequently, the design and composition of the GDL can significantly influence the selectivity of CO2 reduction products. By tailoring the properties of the GDL, researchers can exert control over both the rate and selectivity of the process [16], enabling the selective production of various products such as carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), or ethylene (C2H4).

The macroporous substrate (MPS) of the GDL acts as the physical framework and provides structural support for the remaining layers. The choice of substrate material has emerged as a critical factor in the performance of GDEs for the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. Commonly used substrate materials include carbon paper, carbon cloth, and carbon felt [17,18]. Carbon paper, a porous and conductive material, has been widely employed in various electrochemical systems due to its advantageous properties, including high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and superior chemical stability [19]. These characteristics make carbon paper an ideal candidate for use in gas diffusion electrodes for CO2 reduction.

To control the wettability of the MPS, various hydrophobic additives such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), and fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) can be incorporated onto its surface [14,20]. The influence of PTFE on the performance of electrocatalytic flow cells has been extensively investigated [16]. High PTFE loadings in the microporous layer render the GDL less susceptible to electrolyte flooding; however, this also leads to reduced gas transport and increased electrical resistance [21].

Despite the numerous advantages of employing carbon paper as the GDL in GDEs, several limitations persist. A primary concern is the susceptibility to carbon corrosion, which may occur when the electrocatalyst and carbon paper are subjected to high potentials over extended periods [22]. Carbon corrosion can result in the degradation of both the electrocatalyst and the GDL, ultimately diminishing performance and increasing operational costs. Addressing this issue necessitates a more comprehensive investigation into the behavior of the MPS within the GDL.

Therefore, the main objective of this study is to compare the efficiency and selectivity of the electrocatalytic CO2 reduction process using different GDE substrates. Additionally, this work aims to elucidate how the use and content of Nafion® polymer as a binding agent influence the performance of the electroreduction process.

2. Results and Discussion

As previously mentioned, the main objective of this work consists of the analysis of the effect of the material used as the macroporous layer of the gas diffusion electrode in the electrocatalytic CO2 reduction process. Likewise, it is studied how the Nafion® containing solution used as a binding agent affects the process. It must be noted that the electrode surface area is 25 cm2, which is larger than many of those used for these kinds of studies, but it is closer to values required for future industrial applications.

2.1. Characterization of Gas Diffusion Electrodes (GDEs)

First, the elements that are part of the GDEs have been structurally characterized with the aim of subsequently relating these properties to the electrocatalytic behavior of the resulting GDEs.

The characterization of Cu/CNTs catalyst synthesized through SFD technique has been carried out using TEM, XRD, and ICP. The main results and discussion are included in the Supplementary Material, as the study of the catalytic material, in this case Cu/CNT, is not the main objective of this work. Thus, Cu/CNT with a 17% of Cu and a synthesis yield of 85 ± 5% has been obtained with mostly spherical metallic Cu nanoparticles after the synthesis through SFD (with mean crystallite size of 12 ± 3 nm). Also, cubic nanoparticles corresponding to copper oxidized species can be observed.

2.1.1. Superficial MPS Characterization

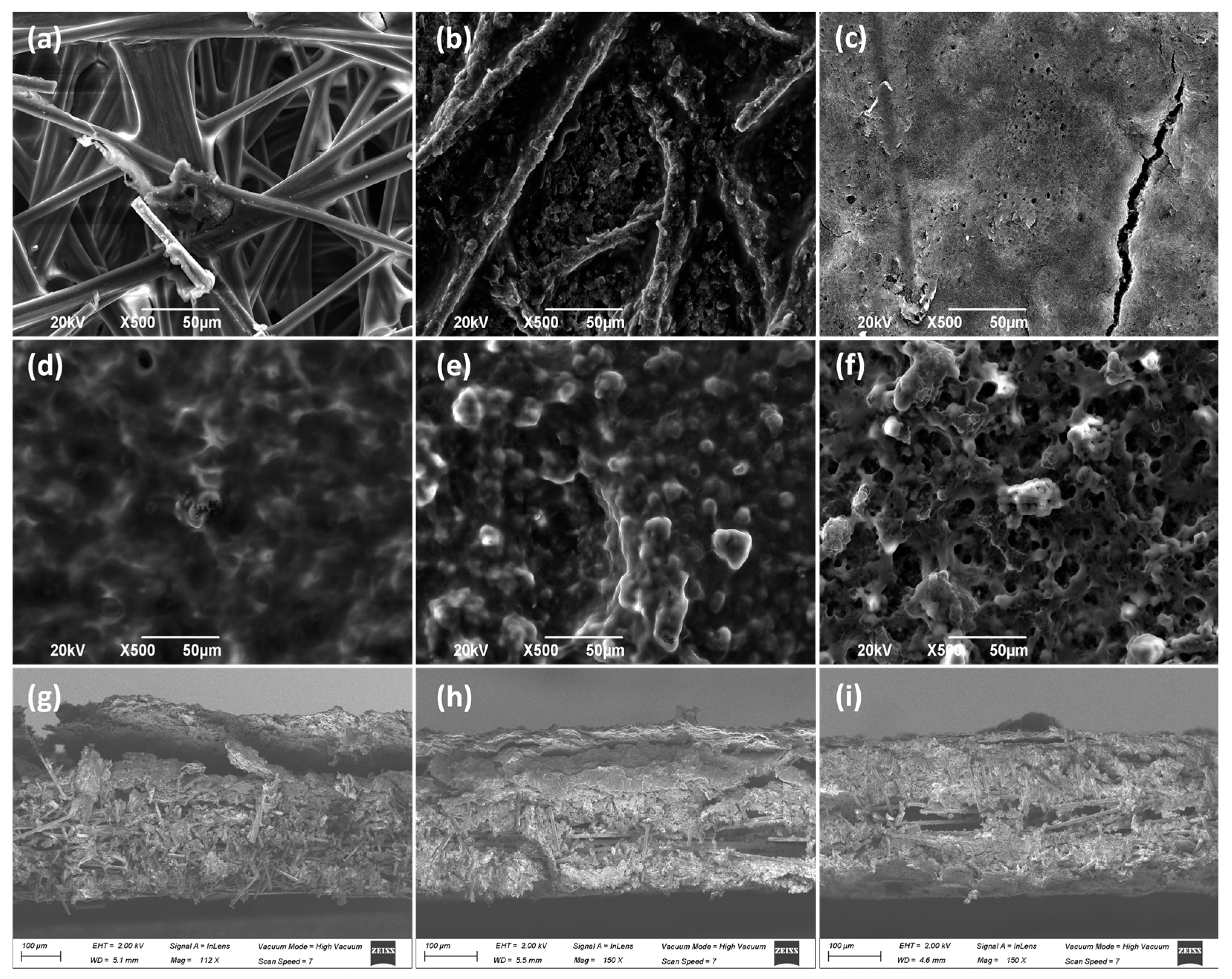

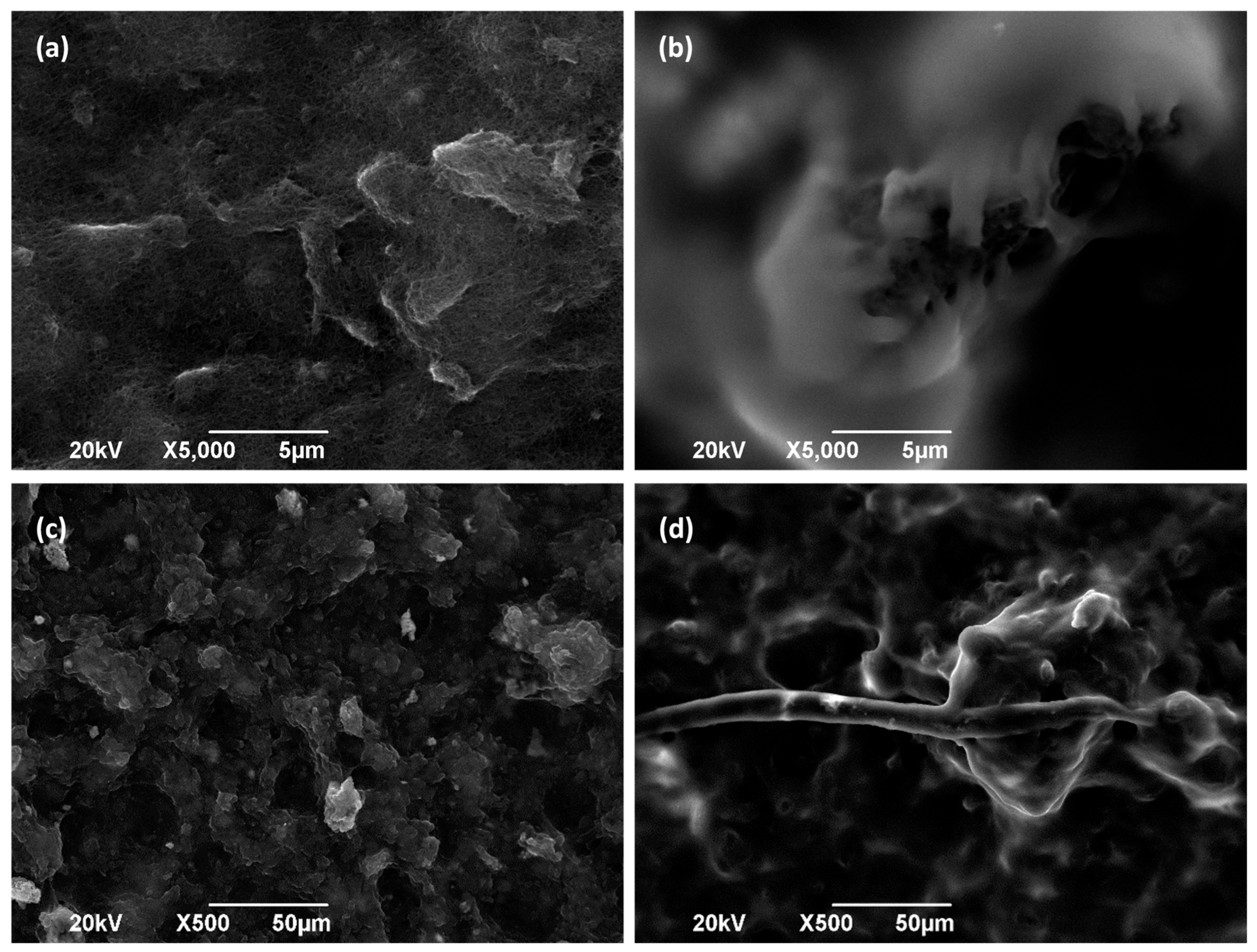

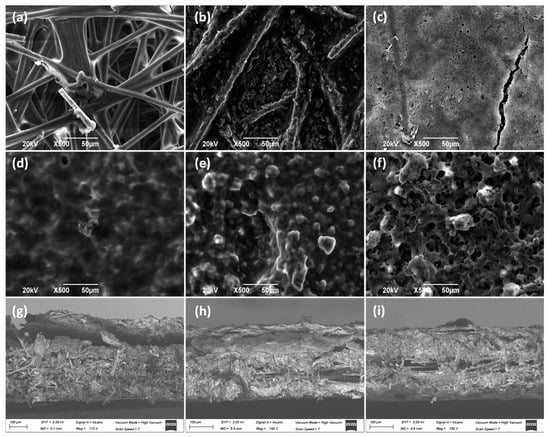

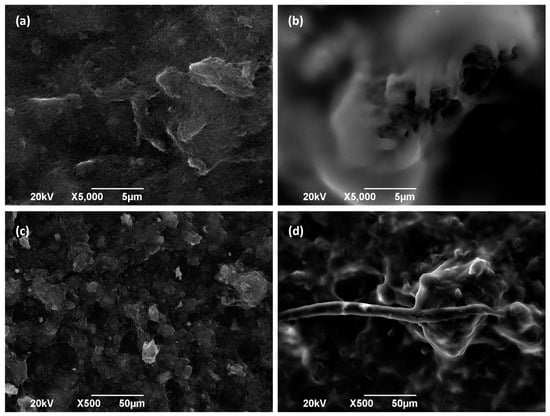

SEM and BET have been used to determine morphological differences among 3 types of carbon papers used as MPS in GDEs and how Cu/CNTs are placed on them.

SEM pictures (Figure 2) show the morphological structure of the different carbon paper studied as MPS in this work (Figure 2a–c). As can be observed, in the first two materials (Toray 090, Figure 2a and AvCarb P75T, Figure 2b), the fibers are distributed in a matrix, whereas in the third one (Freudenberg H23C2, Figure 2c), the microporous layer (MPL) can be appreciated. Moreover, it can be observed that the catalytic layer (CL) is deposited on them (Figure 2d–f). As can be observed, once the CL is deposited on the piece of carbon paper, the aspect of the materials seems to be quite different. Thus, Toray 090 (Figure 2d) appears to form the smoothest surface of the three materials studied as macroporous substrate. It should be considered that a larger porosity of substrate could help to achieve a better union with CL. Furthermore, cross-section images have also been taken to better appreciate the deposition of the catalytic layer on each material (Figure 2g–i). Thus, in Figure 2g, corresponding to Toray paper, the catalytic layer can be clearly seen in the upper part of the image, partially lifted when the piece was cut to carry out the measurement. Likewise, the fibers of the Toray 090 carbon paper piece are clearly visible below the said CL. This structure is also observed in the other materials, although the layers are partially intermixed because of the shearing produced during the cutting of the piece.

Figure 2.

SEM pictures of GDE carbon paper before and after spreading the CL (Cu/CNT + binding agent). (a) Toray 090, (b) Avcarb P75T, (c) Freudenberg H23C2, (d) Toray 090 + CL, (e) Avcarb P75T + CL, (f) Freudenberg H23C2 + CL, (g) Cross section of Toray 090 + CL, (h) Cross section of Avcarb P75T + CL, (i) Cross section of Freudenberg H23C2 + CL. In every case, 1.2 mg/cm2 of Nafion® polymer has been added as a binder, during electrodes preparation.

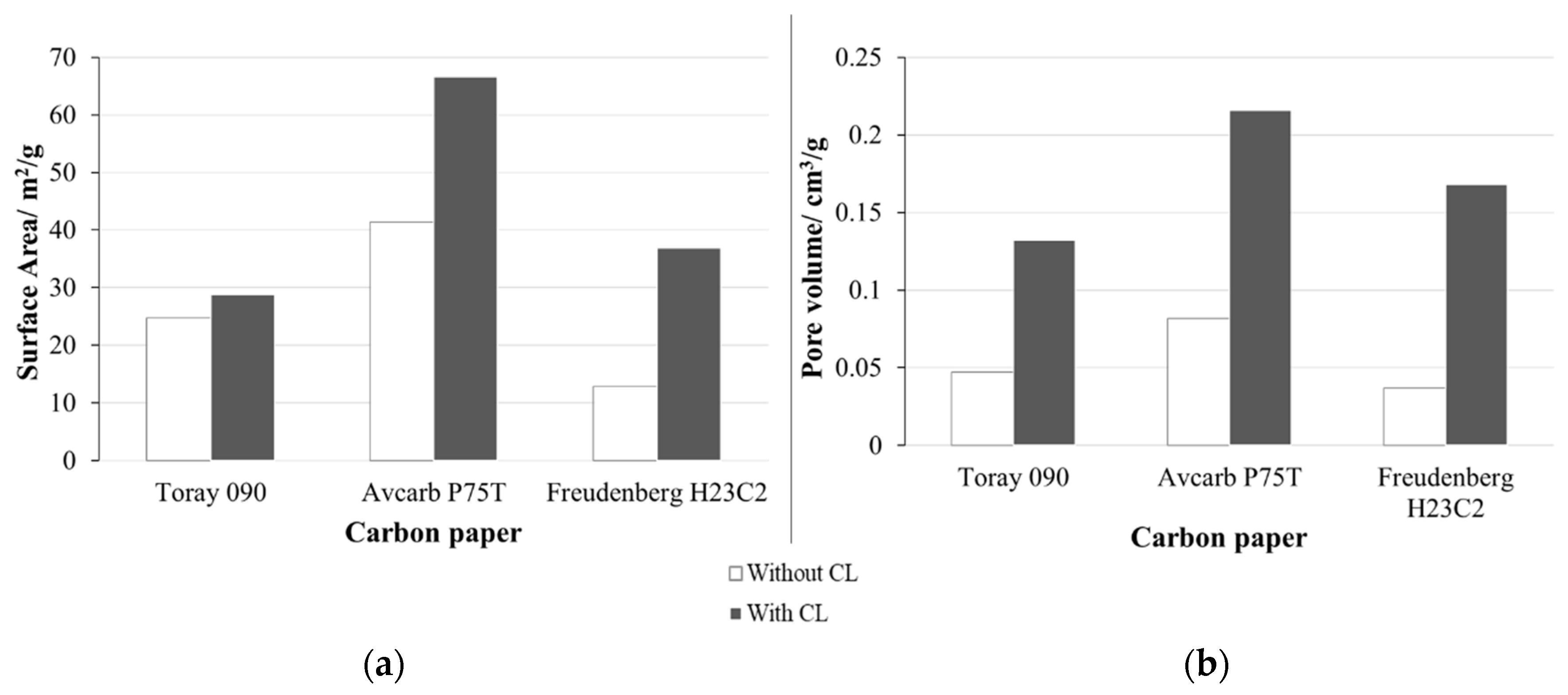

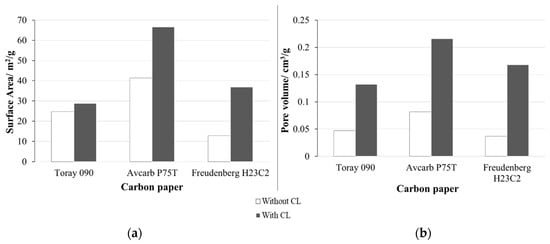

The surface area and porosity of the three types of carbon paper with and without CL have been analyzed using BET (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Results obtained from BET analysis of the three carbon papers studied with and without catalytic layer (CL). (a) Surface area (m2/g) and (b) pore volume (cm3/g).

Results obtained from BET in Figure 3 show that Avcarb P75T presents the largest surface area and pore volume. In any case, both parameters increase when adding the CL. However, this increase is much important in the case of Freudenberg H23C2 (surface area increase in ~190% and pore volume increase in ~360%), that in the case of Toray 090 (~20% and ~180%) or Avcarb P75T (~60% and ~160%). These observations (marked increase in surface area and pore volume with CL) are probably related to the presence of MPL in Freudenberg H23C2, unlike the other carbon papers.

As previously commented, the surface area of the substrate material could be relevant in its union with the CL. In this sense, the lower surface area of Freudenberg could result in a less efficient union between the substrate and the CL, leading to a high surface structure mainly formed by the CL deposited on the substrate, but with an important part of the catalyst being relatively far from the carbon substrate. On the contrary, the high surface area of Toray and, especially of AvCarb, promotes the formation of a high surface CL in which part of the catalyst penetrates the structure of the substrate. As a result, the catalyst particles would be closer to the carbon substrate.

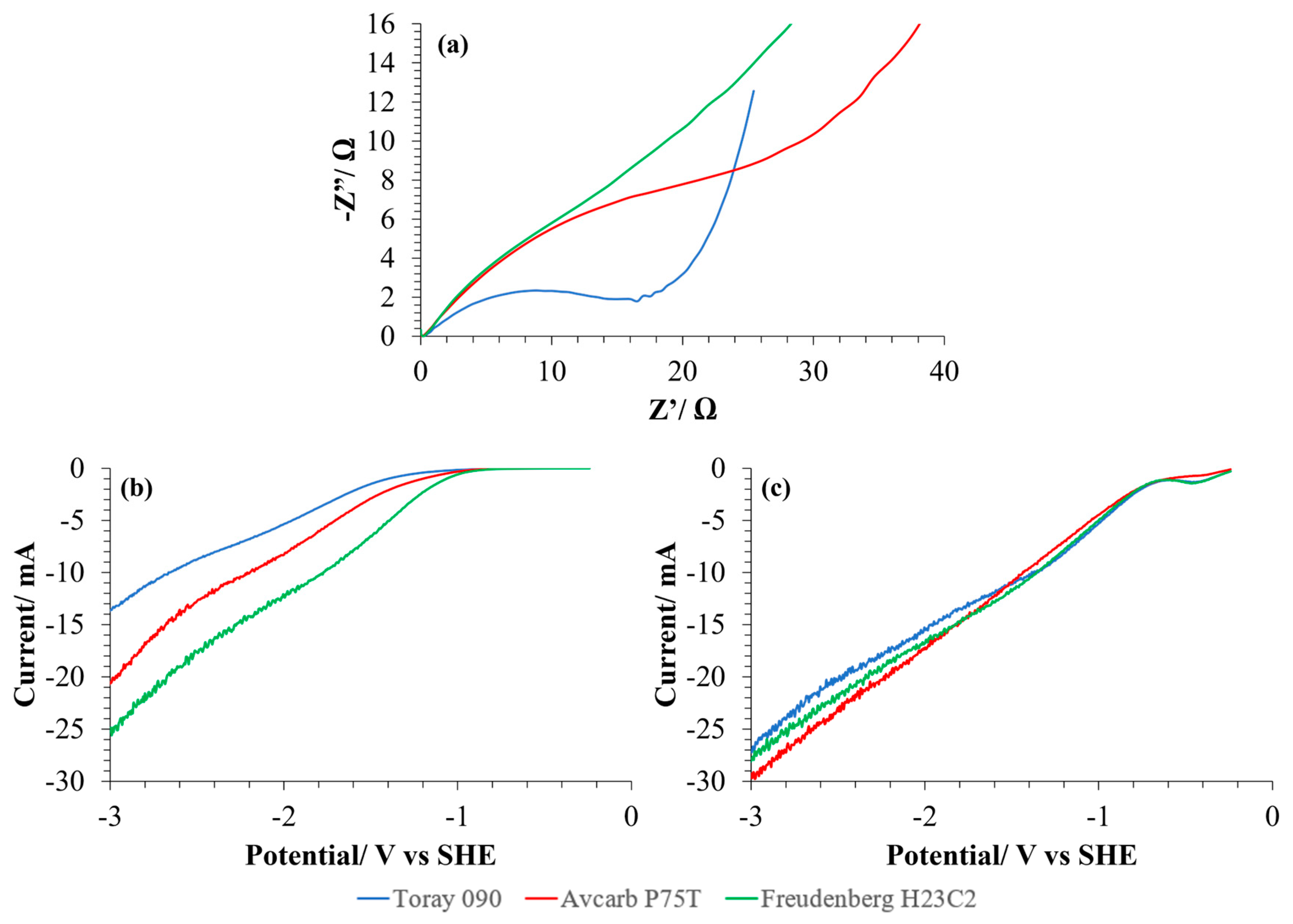

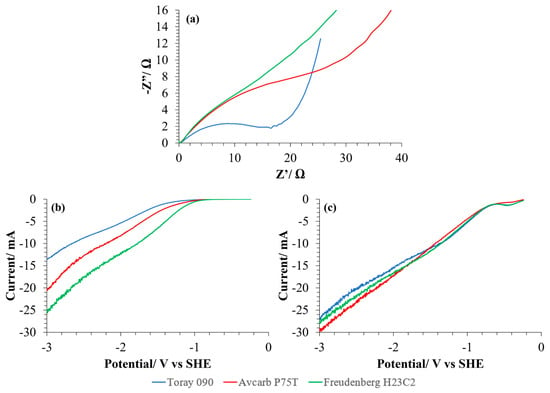

2.1.2. Electrochemical MPS Characterization

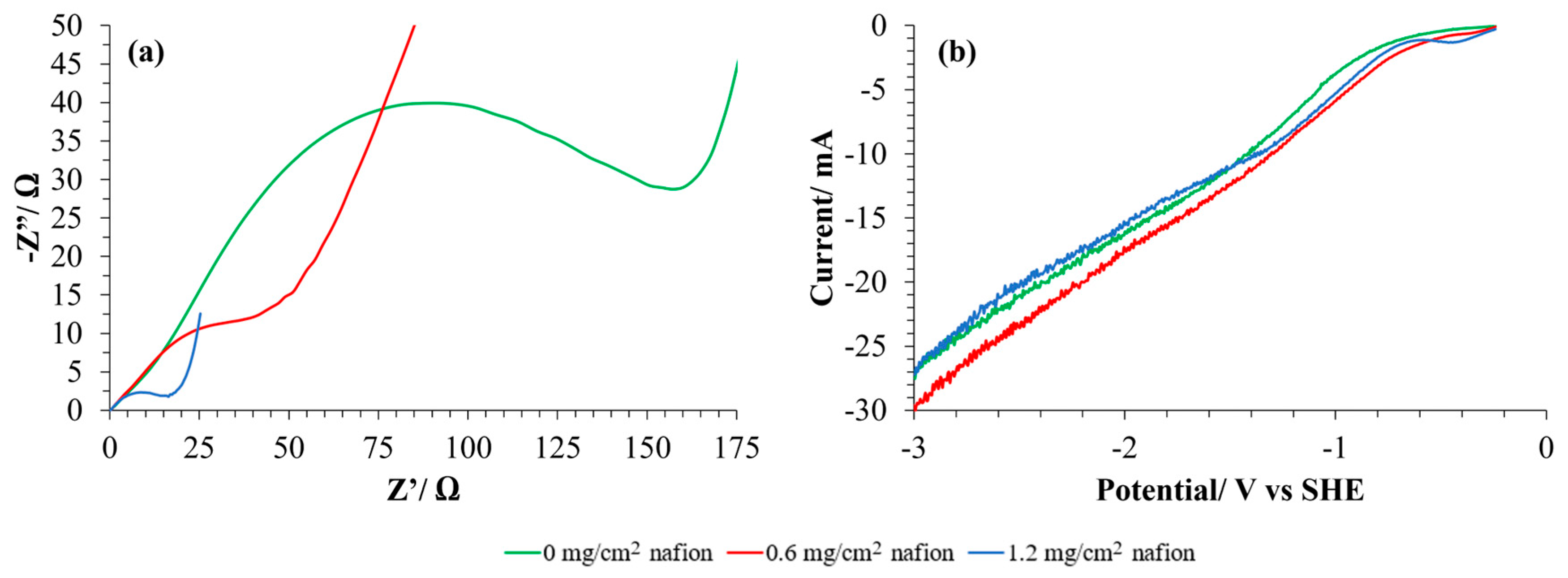

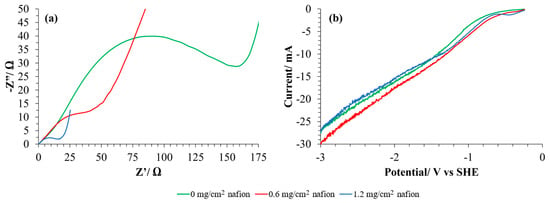

For the electrochemical characterization of the GDEs prepared with the three different carbon papers, EIS and LSV have been carried out and the results are shown in Figure 4. First, Nyquist diagrams obtained from the EIS of each different GDE have been compared in Figure 4a. To facilitate the comparison, the Nyquist data were aligned to a common origin by subtracting the ohmic resistance. In general, the use of Avcarb P75T or, specially, Freudenberg H23C2 as MPS resulted in larger diameters for the semicircle and consequently, to a larger total faradaic impedance. Therefore, the GDE based on Toray 090 carbon paper seems to have the best conduction properties leading to a better electrocatalytic activity in terms of charge transfer. Nevertheless, when analyzing the results of LSV of the carbon substrates (as received, without catalyst) (Figure 4b), it can be observed that Freudenberg H23C2 achieves the larger currents. However, when the CL is added to the carbon paper to obtain the GDEs (Figure 4c), the current obtained increases for both based on Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T, but not for that made with Freudenberg, which makes the current achieved with the three materials quite similar in that case. These results show that, although the three MPS have different electrical characteristics from each other, and their resistance to charge transfer is different, once the catalytic layer has been added, the current intensity they achieve is very similar. This could be indicative of a predominance of other mechanisms controlling the process (such as diffusion) and not of charge transfer in the conditions studied.

Figure 4.

Results obtained from the electrochemical characterization of the MPS with the three carbon papers studied. (a) Nyquist diagrams of each GDE composed of the carbon paper and the catalytic layer (CL) based on Cu/CNTs catalyst and Nafion® binding agent. (b) LSV (scan rate: 5 mV/s) of the carbon papers in the CO2-saturated electrolyte. (c) LSV (scan rate: 5 mV/s) of the carbon papers with the CL impregnated (Cu/CNTs + binding agent) in CO2 saturated electrolyte. A Pt mesh has been used as a counter electrode and calomel as a reference electrode. 0.1 M KHCO3 has been used in every case as electrolyte. EIS were recorded in the range of 1 Hz to 100 kHz in a potentiostatic operation mode with an applied potential of 0 V and an amplitude of 0.01 V.

Charge transfer resistance (Rct) has been determined from fitting Nyquist diagrams [23] (Table 1). The GDE composed of Toray 090 exhibits the lowest Rct, which reflects its higher charge transfer capacity. On the contrary, the GDE obtained with Freudenberg H23C2 shows the highest Rct (almost five times higher than with Toray 090), maybe because of the presence of the MPL, with a much higher Teflon® content (40%).

Table 1.

Values of charge transfer resistance of the GDEs obtained with different MPSs and binding agent concentrations.

2.1.3. Binding Agent Effect

As previously commented, Nafion® is one of the most common binding agents used in PEM electrocatalytic cells. EIS and LSV allow us to evaluate the effect of adding a certain amount of Nafion® solution to the catalytic ink on the electrical performance of GDEs. So, Nyquist curves and LSV were obtained for GDEs with different Nafion® content and in absence of Nafion® (Figure 5a and Figure 5b, respectively) and Rct were calculated from fitting Nyquist diagrams (Table 1). The commonly used load of Nafion® polymer in previous works of our group has been 1.2 mg/cm2 [24,25]. Thus, for this study, half that load has been compared (0.6 mg/cm2), as well as the absence of binding agent. In every case, Toray 090 has been used as MPS material for this study.

Figure 5.

(a) Nyquist diagrams and (b) LSV (scan rate: 5 mV/s) in CO2 saturated electrolyte for GDLs with different content of binding agent in the CL. Toray 090 has been used as MPS in every case. A Pt mesh has been used as a counter electrode and calomel as a reference electrode. 0.1 M KHCO3 has been used in every case as electrolyte. EIS were recorded in the range of 1 Hz to 100 kHz in a potentiostatic operation mode with an applied potential of 0 V and an amplitude of 0.01 V.

As expected, it can be observed that an increase in the content of the binding agent implies a decrease in the charge transfer resistance (Rct) of the GDE (more than seven times lower when 1.2 mg/cm2 of Nafion® is used). When Nafion® is added to the electrodes (together with Cu/CNT), it forms a polymeric layer, as can be seen in Figure 6b,d with respect to Figure 6a,c, which correspond to Toray paper without CL. Nafion® binding agent can enhance conductivity, proton selectivity, and proton exchange between gas and liquid medium. At assembly time, Nafion® acts like a glue to link catalyst particles supported on GDLs to polymer electrolyte membrane [11]. However, the resulting current intensity in the LSVs seems to be practically independent of the amount of binding agent used (Figure 5b). These observations could suggest that, although the charge transfer is easier in the presence of Nafion®, there are many other processes involved in the catalytic reduction reactions that result in the similar behavior of the GDEs. Thus, according to the literature, while increased Nafion® loading enhances proton conductivity and reduces charge transfer resistance, it may simultaneously have a detrimental effect on gas-phase mass transport [26]. Excessive Nafion® can obstruct pores within the catalyst layer or coat active sites, thereby limiting the diffusion of reactants to the catalyst sites [26]. Conversely, during chronoamperometry or polarization measurements, limitations in CO2 diffusion or the accumulation of reactants can significantly affect performance [27]. This may result in a decrease in the electrical charge generated at a given voltage in the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements.

Figure 6.

SEM picture of Toray 090 carbon paper with Cu/CNTs deposited in (a,c) absence and (b,d) presence of Nafion® polymer (1.2 mg/cm2).

2.2. CO2 Electroreduction

Once the different parts of the GDE have been characterized, their influence in the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 in the gas phase in a zero-gap cell has been studied. To this end, tests have been carried out under galvanostatic conditions, so product formation and CO2 reduction rates have been studied at different values of current density. In all cases, three replicates were performed for each of the experimental conditions studied. The error bars representing the standard deviation are shown in the figures. The CO2 conversion rate was calculated as a single-pass conversion rate, based on the molar production rates (mmol/h) of each detected gaseous and liquid product. For this calculation, the stoichiometry of each product with respect to CO2 consumption was considered, allowing the total amount of converted CO2 to be determined from the sum of all CO2-derived products formed during a single pass through the electrochemical cell. Prior to each round of experiments, several tests were carried out using N2 instead of CO2 as blanks, to remove all interference items such as Nafion® solution solvents (aliphatic alcohols) occluded into the CL and the carbon paper at the assembly process.

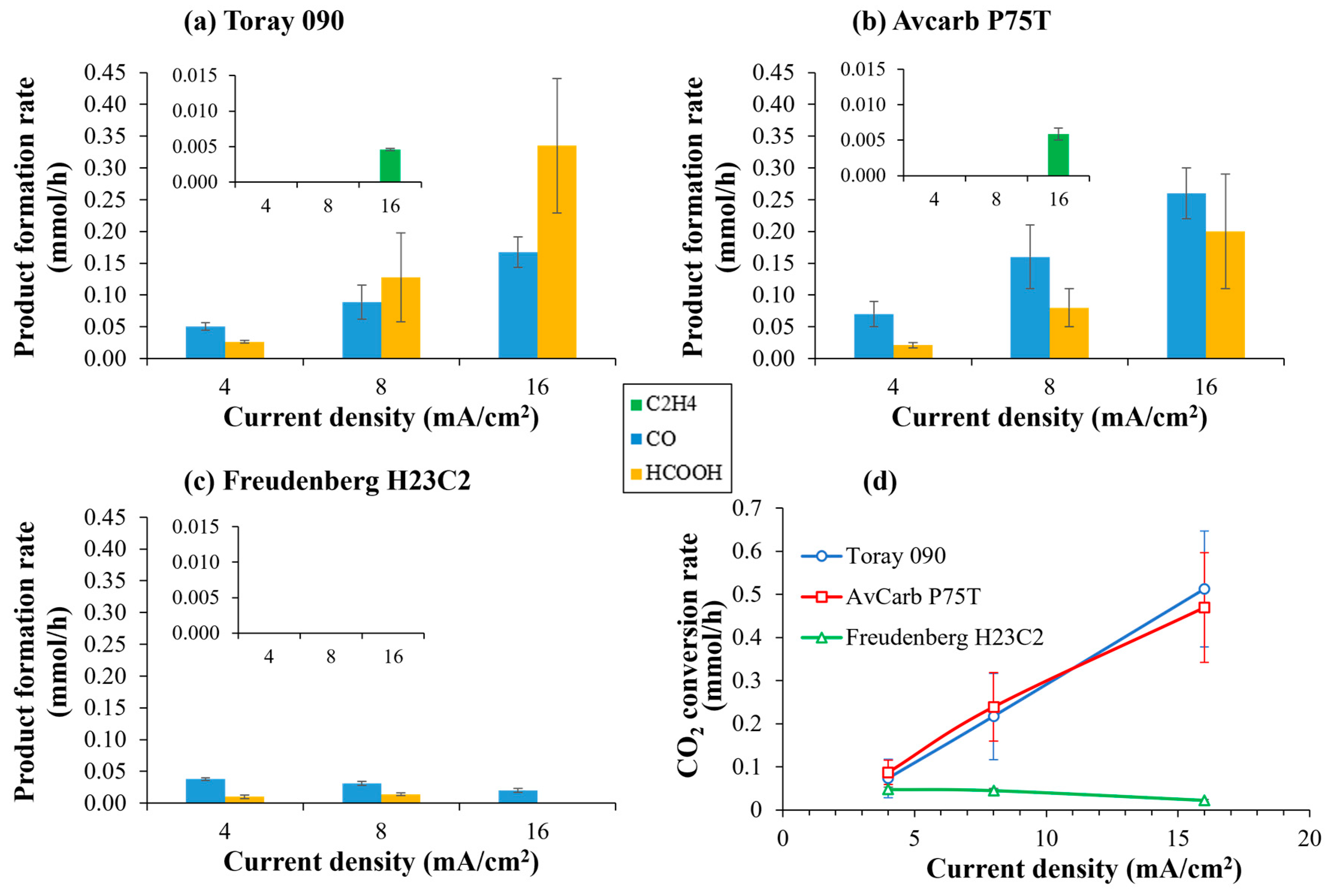

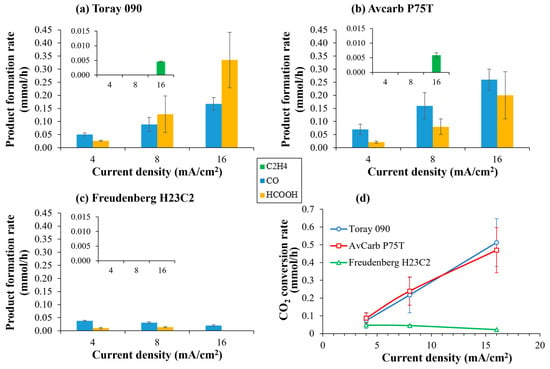

2.2.1. Influence of Carbon Paper in the Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2

Firstly, the influence of the carbon paper used as a MPS on the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 in the gas phase has been studied. Thus, Figure 7 shows the distribution of reaction products (Figure 7a–c) and the rate of CO2 conversion (Figure 7d) at increasing current densities, with the three different carbon papers used as MPS. In any case, the main reaction products are CO and formic acid, no matter the carbon paper used. However, with GDEs based on Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T, a small amount of ethylene (4.6 and 5.9 µmol/h, respectively) can be observed at 16 mA/cm2 as well as very small traces (below 0.1 µmol/h) of ethanol in the case of GDEs based on Avcarb P75T.

Figure 7.

Product formation rate (a–c) and CO2 conversion rate (d) at different current densities using Cu/CNTs catalyst deposited over different carbon papers: (a) Toray 090, (b) Avcarb P75T and (c) Freudenberg H23C2. Experimental conditions: anolyte: 0.1 M KHCO3, temperature: 60 °C, CO2 flow rate: 0.05 L/min. The onset in the figures shows a magnification where the formation of ethylene can be observed.

As shown in Figure 7d, GDEs based on Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T exhibit comparable CO2 conversion rates, increasing linearly with current density in both cases. In contrast, GDEs prepared with Freudenberg H23C2, despite containing an MPL, display extremely low CO2 conversion, largely independent of current density and even decreasing at higher current densities. This markedly poorer performance cannot be solely attributed to its lower porosity or surface area. Instead, it is consistent with the behavior described by Baumgartner et al. (2022) [28], who demonstrated that certain GDLs present a narrow pressure-stability window, making them highly susceptible to premature flooding or gas-pathway blockage under relatively mild operating conditions. When such instability occurs, CO2 access to the catalytic layer becomes severely restricted, the three-phase boundary collapses, and mass transport limitations dominate, favoring hydrogen evolution over CO2 reduction. Thus, even when BET indicates an apparent increase in surface area after catalyst deposition, much of that area would not be electrochemically accessible under the operative conditions used because the microporous network would be quickly flooded or poorly connected. These mechanistic effects documented in Baumgartner et al. 2022 [28] offer a consistent explanation for the very low CO2 conversion and elevated H2 selectivity observed with Freudenberg H23C2 in our experiments.

Additionally, SEM imaging reveals that Freudenberg H23C2 presents a significantly lower fraction of cracks within the MPL. These cracks act as preferential gas-transport channels, facilitating reactant penetration into the catalytic layer. Their scarcity in Freudenberg, combined with the limited pressure-stability window highlighted by Baumgartner et al. [28], likely reduces the electrochemically accessible area of the deposited Cu/CNT-Nafion CL despite the increase in BET surface area measured ex situ. Under the operative conditions studied, the microporous network of Freudenberg would be therefore more susceptible to localized wetting and loss of gas permeability, coherently explaining its low CO2 conversion rate and high H2 selectivity.

On the other hand, the main difference between Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T lies in process selectivity. While Toray favors formic acid formation, Avcarb promotes higher CO production. Both materials show an increasing proportion of formate at higher current densities. Faradaic efficiencies (FEs) corresponding to both CO2 reduction and H2 evolution were quantified (Figure S5a, Supplementary Material). Overall faradaic efficiency rises with current density due to enhanced hydrogen generation, particularly when using Freudenberg H23C2. Faradaic efficiency toward formic acid also increases with current density in Toray and Avcarb, surpassing that of CO at higher current densities. Likewise, the formation of ethylene is observed in the larger currents studied, with faradaic efficiencies of 0.4–0.5% for Toray and Avcarb, respectively. The highest faradaic efficiency for CO2 reduction products relative to H2 formation was achieved with Avcarb P75T at 16 mA/cm2 (6.72%), whereas Freudenberg H23C2 consistently remained below 3%.

Finally, considering the intrinsic properties of the substrates, Toray 090 presents the lowest charge transfer resistance, while Avcarb P75T provides the highest surface area and porosity after CL deposition, enhancing catalyst–binder interactions and mass transport. This seems to favor the further reduction in reaction intermediates (such as CO2H*) to CO [29], instead of their desorption to formate. These features likely explain the similar CO2 conversion rates observed with both materials, although their different structural characteristics and GDL thickness result in diverging product selectivity patterns. Thus, several authors [16,28] related the variation in selectivity during CO2 electroreduction in zero gap cells with the thickness of the GDL. In our case, the highest proportion of formic acid is observed when using a GDE composed of Toray 090, which has the greatest thickness (280 µm), while Avcarb P75T and Freudenberg H23C2, with slightly smaller thicknesses (250 and 255 µm, respectively), mainly give rise to CO.

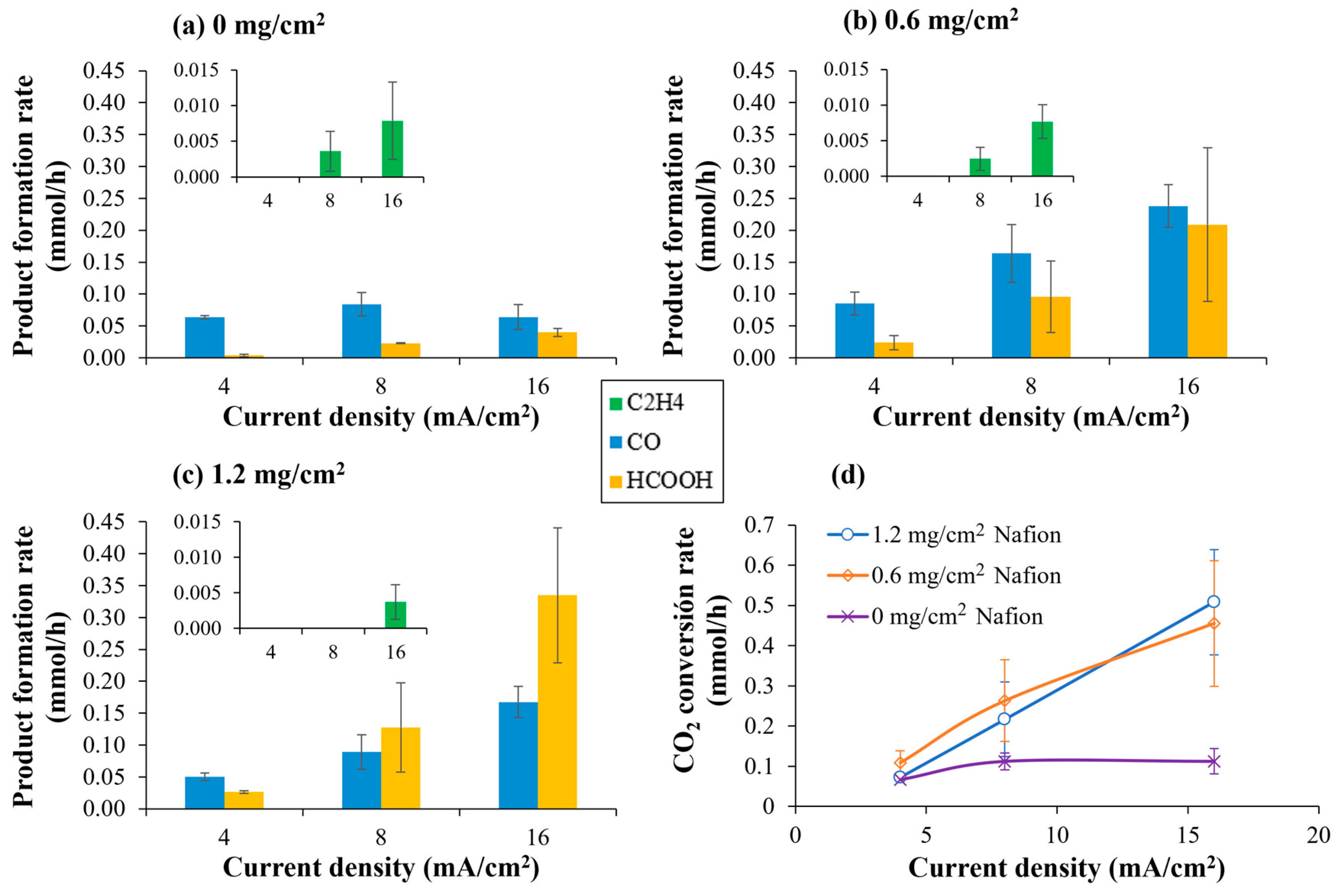

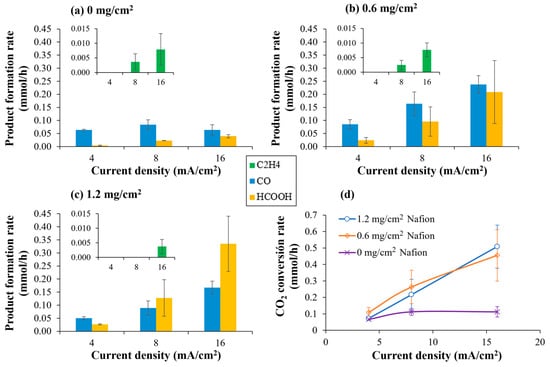

2.2.2. Influence of Nafion® Polymer Content in CL on Electroreduction Process

Results involving CO2 electrocatalytic reduction with Cu/CNTs supported on Toray 090 carbon paper with different Nafion® polymer content in the catalytic layer (0, 0.6 and 1.2 mg/cm2) are shown at Figure 8. Previous works of our group related to the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 have been carried out using 1.2 mg/cm2 of pure Nafion® in the catalytic layer [25,30]. However, little amounts of organic compounds such as methanol and isopropanol were observed even without the circulation of CO2 flowrate through the cell, but with N2 in the first two or three assays with every new membrane–electrode assembly. It could be observed that, when Nafion® solution was not added to the catalytic layer, those products were not observed, which seems to confirm that they came from the Nafion® solution.

Figure 8.

Influence of Nafion® content in the CL during CO2 electrocatalytic reduction using Cu/CNTs catalyst. (a) 0 mg Nafion polymer; (b) 0.6 mg/cm2 Nafion polymer; (c) 1.2 mg/cm2 Nafion polymer; (d) CO2 conversion rate as a function of Nafion polymer content in the CL. Experimental conditions: anolyte: 0.1 M KHCO3, temperature: 60 °C, CO2 flow rate: 0.05 L/min. The onset in the figures shows a magnification where the formation of ethylene can be observed.

However, although it was found that not using the Nafion® solution prevented the observation of said products that did not come from the reduction of CO2, the absence of a binding agent caused the rate of CO2 conversion to be greatly diminished. Thus, as can be observed in Figure 8, the incorporation of a binding agent into the CL is indispensable for establishing the ionomeric network required to sustain CO2 electroreduction. The presence of Nafion® enables the formation of continuous proton-conducting domains that connect the membrane with the catalytic sites, ensuring that both ionic and electronic pathways coexist within the CL [31]. In the absence of a sufficient amount of binder, proton availability becomes the limiting factor, resulting in negligible faradaic efficiencies toward CO2-derived products (as can be observed in Figure S1). As the Nafion® content is increased from 0 to 0.6 mg/cm2, these conductive networks become progressively more interconnected, which translates into an enhancement in catalytic accessibility and improved CO2 conversion.

However, when the Nafion® loading is further increased from 0.6 to 1.2 mg/cm2, no significant improvement in the CO2 conversion rate is observed. Instead, marked variations in product selectivity appear. Across all operating conditions, CO and formic acid remain the major products, with ethylene formation only detected at the highest current densities, in agreement with the higher overpotentials needed for C-C coupling. Notably, higher Nafion® proportions promote the formation of formic acid relative to CO, shifting the product distribution toward pathways that require more proton-rich intermediates. This observation is consistent with the findings of Kim et al. [12], who demonstrated that an insufficient amount of Nafion® polymer can cause protons to be unable to access all parts of the CL. This could translate into a greater limitation for the CO2 molecule to react with said protons to form formic acid, promoting the re-action towards the formation of CO.

The beneficial role of Nafion® at moderate loadings can also be interpreted from a structural perspective. At appropriate contents, the ionomer wets the catalyst particles, establishing thin ionic films that enhance catalyst–electrolyte interaction while preserving open pathways for gas diffusion [32]. Under these conditions, CO2 molecules can permeate through the CL, react at the exposed active sites, and be efficiently converted. Nevertheless, as the Nafion® content continues to rise, the morphology of the CL undergoes a transition in which the ionomer would cause the blocking of the pores of the catalytic layer as well as the electronic conduction path [12]. This not only restricts gas-phase CO2 transport but also decreases the triple-phase boundary length, reducing the number of catalytically active sites actually participating in the reaction. This phenomenon is frequently reported in the literature for GDE-based systems, where the delicate balance between hydrophobicity, ionomer coverage, and porosity determines the overall device performance [31,32].

The onset of mass-transfer limitations is further supported by the electrochemical characterization. The decreases in current density observed in the LSVs for high Nafion® contents reflect reduced CO2 accessibility and the hindered removal of gaseous products, suggesting that the CL becomes increasingly compact and diffusion-limited. These findings corroborate the FE trends displayed in Figure S1b (in the Supplementary Material): faradaic efficiencies increase markedly as Nafion® loading rises from 0 to 0.6 mg/cm2 across all current densities, reaching a maximum of 7.2% at 8 mA/cm2 (0.2 A) for CO2 reduction products formation. When the loading is further increased to 1.2 mg/cm2, the FEs decline for both CO2 reduction and H2 formation, indicating that the accumulation of ionomer no longer provides additional protonic connectivity but instead suppresses electrochemical activity by diminishing gas transport and obstructing the electronic conduction pathways necessary for efficient charge transfer.

From a broader perspective, these results highlight the importance of achieving an optimal balance between ionomer content, catalyst utilization, and pore structure. Insufficient ionomer leads to limited proton transport and incomplete catalyst wetting, whereas excessive ionomer coverage produces overly dense CLs with reduced permeability and increased ohmic resistance. The observed trends align with the behavior reported for advanced CO2 electrolyzers and PEM-based devices, where the interplay between binder distribution, microstructural homogeneity, and mass transport ultimately dictates the achievable selectivity and efficiency. Therefore, the identification of an optimal Nafion® loading is essential for maximizing CO2 conversion while maintaining adequate gas diffusion and minimizing transport losses.

The use of gas diffusion electrodes in PEM type cells to carry out the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 has gained great relevance in recent years. However, the studies carried out related to the CO2 reduction process usually focus on the composition and design of the catalyst, but do not usually focus on the rest of the components of the gas diffusion electrodes.

In this context, as has been observed in this work, the different elements of the GDE, apart from the catalyst, play an important role in the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. Thus, two carbon papers used as carbon support such as Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T, with different mechanical and electrical properties, lead to very similar results in terms of CO2 conversion rate but with different selectivity. On its part, the use of a binding agent is necessary for the process to take place, and its concentration can affect both the efficiency and the selectivity of the process.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Experimental Equipment

3.1.1. Synthesis of Cu/CNT Catalyst Using Supercritical CO2

The electrocatalyst used in this work consists of Cu nanoparticles deposited on carbon nanotubes (Cu/CNTs), given its good performance in gas phase CO2 electroreduction [33]. It is synthesized by supercritical fluid deposition (SFD), as described in previous works [24]. The experimental set-up used for the synthesis of Cu/CNT electrocatalysts involves an ad hoc 90 mL stainless steel reactor (DEMEDE Engineering and Research) with a temperature controller (TTM-204, TOHO, Tokyo, Japan) and a high-pressure pump (P-50, Thar SFC, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) to increase CO2 pressure. There is also a circuit that consists of a vessel to feed hydrogen from a cylinder. The reactor output stream reaches a filter (1 mm) to prevent the catalyst loss during the decompression stage. A scheme of this set-up is shown in Figure S2 in the Supplementary Material.

3.1.2. CO2 Electroreduction

Regarding the experimental set-up for carbon dioxide electroreduction in the gas phase, it is also described in previous works [24,30], and can be seen in Figure S3 in the Supplementary Material. It includes a PEM (proton exchange membrane)-type electrochemical cell (ElectroChem electrochemical cell, supplied by Fuelcellstore (College Station, TX, USA), electrode area 25 cm2). The catalytic layer (CL) of both gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) is composed by Cu/CNT catalyst and Nafion® polymer as binding agent (perfluorinated resin Nafion®, 5% in lower aliphatic alcohols, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). The catalytic ink (suspended in isopropanol) is sprayed by airbrushing on carbon paper (used as MPS). Three different commercial carbon papers (Toray® (Tokyo, Japan) 090, Avcarb® (Lowell, MA, USA) P75T and Freudenberg® (Weinheim, Germany) H23C2) have been compared in this work. Their characteristics are shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material. To obtain the membrane–electrodes assembly (MEA), both GDEs (anode and cathode) are assembled to a Nafion® 117 proton exchange membrane by hot pressing.

The cell, equipped with a temperature controller, receives a 0.1 M KHCO3 solution in its anodic compartment by means of a peristaltic pump (D21-V, DINKO, Taoyuan City, Taiwan), and a constant CO2 flowrate (0.05 L/min) in its cathodic compartment thanks to a mass-flow controller (SLA5850, BROOKS, Seattle, WA, USA). A humidifier of the gas stream is placed between the mass-flow controller and the cell. Electric current is supplied with a potentiostat–galvanostat (PGSTAT302N, AUTOLAB, METROHM, Herisau, Switzerland).

3.2. Analytical Methods

3.2.1. Characterization of GDEs

Different characterization techniques have been applied for the evaluation of Cu/CNT catalyst synthesized using supercritical fluid deposition as well as for the analysis of the superficial and electrochemical properties of the materials studied in this work.

TEM (transmission electron microscopy) was performed with a Jeol 2100 TEM microscope (Peabody, MA, USA) operating at 200 kV equipped with a side entry double-tilt (±25 °C) sample holder and EDS detector (Oxford Link, Oxford, UK).

Regarding SEM (scanning electron microscopy), a Jeol 6490LV SEM microscope was employed to appreciate structural qualities of each carbon paper, Cu/CNTs, and the effect of adding Nafion® solution as a binding agent.

ICP-AES (inductively coupled plasma, atomic emission spectrometry) Liberty Sequential (VARIAN) was used to analyze the copper concentration of Cu/CNT catalysts.

XRD (X-ray diffraction) measures with an XRD Philips, X Pert MPD were essential to determine the copper species deposited on the carbon nanotubes and carbon paper characteristics. The mean crystallite size of copper nanoparticles deposited onto the carbon nanotubes has been calculated from the XRD diffractograms using the Scherrer equation.

Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) have been carried out in a 3-electrodes liquid cell, using a potentiostat–galvanostat (AUTOLAB, PGSTAT302N) to evaluate the electrochemical behavior of the different materials studied in this work. A Pt mesh has been used as counter electrode and calomel as a reference electrode. In every case, 0.1 M KHCO3 was used as electrolyte. EIS were recorded in the range of 1 Hz to 100 kHz in a potentiostatic operation mode with an amplitude of 0.01 V.

BET (Brunauer–Emmett–Teller) area analyzer (ASAP 2020, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA) has been used to determinate porosity and surface area of carbon papers and electrodes.

3.2.2. Electroreduction Product Determination

Liquid and gas products coming from the cathodic compartment of the electroreduction cell circulate through a cold trap to collect liquids. Gas products escaping from the trap were injected twice in a gas chromatograph (GC 7890A, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with FID and TCD detectors. Liquid products from the trap were analyzed using a sample pre-concentration system (Auto Sampler 80, Houston, TX, USA) equipped with a solid-phase microextraction (SPME) system with a Carboxen (Darmstadt, Germany)/PDMS fiber coupled with the 7890A GC. The detailed analytical method is described in a previous work [33]. In the case of formic acid, it is determined with a HPLC chromatograph (UV 2025 plus UV/VIS, Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) with an analytic method developed elsewhere [24].

3.3. Experimental Procedures

3.3.1. Synthesis of Cu/CNT Catalyst Using Supercritical CO2

Previous works describe how to synthetize the Cu/CNT catalyst using supercritical fluid deposition technique [24,25]. Briefly, in a batch mode experiment, 0.25 g CNT (MWCNT, 98% carbon basis, Sigma-Aldrich), 0.25 g metal precursor (Cu acetylacetonate, 98%, Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium), and 5 mL of methanol (>99%, Honeywell, Charlotte, NC, USA) are introduced in the reactor. Once the reactor is connected to the experimental set-up and the temperature achieves the set point value (200 °C), the pressure is increased by pumping CO2 up to 100 bar. Those conditions are maintained for 60 min to dissolve metal precursor. Next, hydrogen is introduced into the reactor (4.5% v/v) and pressure is increased up to 250 bar for 30 min to reduce deposited metal to the metallic form. The catalyst obtained is vacuum filtered and dried at 105 °C overnight.

3.3.2. CO2 Electroreduction Experiments

The procedure of spreading the catalyst on a piece of carbon paper is described on previous works [24,30]. First, the catalytic ink is formulated by dispersing Cu/CNTs previously obtained by SFD in 2-propanol and Nafion® solution (if necessary) using ultrasound for 90 min. With the help of an airbrush, catalytic ink is sprayed on a piece of carbon paper (Toray®, Avcarb® or Freudenberg®, all of them Teflon® (Wilmington, DE, USA) treated) to form the GDE. The copper load in the GDE has been set to 0.4 mg/cm2. Both anode and cathode are composed of Cu/CNT for simplicity [24] and according to the advantages proposed by several authors [34,35,36] related to the use of copper for OER (oxygen evolution reaction) as an alternative to noble metals.

Electrochemical CO2 reduction experiments were developed under continuous CO2 flowrate in the cathodic compartment of the PEM cell. This gas is previously humidified in a bubble flask heated with 120 mL of osmotized water. A solution of KHCO3 is used as electrolyte in the anode compartment to provide conductivity and water, whose oxidation provides protons that participate in the reduction of CO2 at the cathode. The aqueous solution is recirculated through the anode compartment using a peristaltic pump (flowrate 0.05 L/min). The operating temperature during the electroreduction experiment is 60 °C, that has been set to this value considering the CO2 conversion results observed in previous works [25,37]. The current intensity (0.1, 0.2 or 0.4 A) is set to begin the galvanostatic electroreduction experiment, which lasts 120 min (and, in addition, the voltage values are recorded along the experiment).

At the outlet of the cathode compartment, the unconverted CO2 stream is circulated together with the reaction products through a liquid trap at 5 °C. The part that does not condense in the trap is circulated to the GC. During the 120 min of the experiment, 2 injections of this gas stream are made into the GC to quantify the concentration of gaseous compounds formed (at 45 and 120 min). At the end of the experiment, the volume of liquid retained in the trap is measured and 1 mL is taken to analyze using GC coupled to a preconcentration system using SPME. With this analysis, the quantification of the concentrations of methanol, acetaldehyde, ethanol, acetone, and isopropanol is carried out. The concentration of formic acid present in the liquid sample is quantified using HPLC.

Once the cell assembly has been completed, the first three experiments are always carried out using a N2 stream instead of CO2, which serves as a control.

4. Conclusions

The main conclusions obtained in the study of the different components of the gas diffusion layer in the electrocatalytic CO2 reduction process in gas phase in a PEM type cell are presented below.

From this study, it can be concluded that the carbonaceous material that acts as a substrate for the catalytic layer is of special importance in the reduction rate of CO2 but also affects the selectivity of the process. Thus, while the use of Toray 090 as MPS results in the majority formation of formic acid, Avcarb P75T mainly results in the formation of CO, although in both cases, the CO2 conversion rates at different current densities are very similar. For its part, when Freudenberg H23C2 (the only one in this study with a microporous layer) is used as the MPS of the GDL, the CO2 conversion rate obtained is more than twenty times lower than that achieved by the other two carbon substrates at the highest current density studied. CO is the main product obtained in that case. These results could be attributed to the high surface area of the GDE based on Avcarb P75T and its interaction with the CL, promoting the reduction in reaction intermediates to CO. In contrast, despite the presence of a microporous layer, the Freudenberg H23C2 substrate exhibits a narrower pressure stability window and a more compact microstructure, which can hinder effective CO2 transport under operating conditions relevant to high current densities. Furthermore, the lower density of microstructural cracks typically observed in Freudenberg-based GDLs limits the availability of preferential gas diffusion pathways, reducing CO2 accessibility to the catalyst layer and thereby suppressing the overall CO2 conversion rate. As a consequence, the Cu/CNT catalyst is unable to fully exploit its intrinsic activity when supported on Freudenberg H23C2, leading to markedly inferior performance compared to Toray 090 and Avcarb P75T substrates.

Furthermore, the binding agent, necessary to achieve an adequate binding between CL and MPS, has been found to be a key component in the performance and selectivity of the process. When the binder is not used during electrodes preparation, the conversion rates are appreciably lower. Thus, the use of Nafion® as a binding agent has been shown to be very important in the reduction of CO2, although the conversion rate does not seem to improve greatly by increasing the binding agent content from 0.6 to 1.2 mg/cm2. However, the binding agent content does seem to affect the selectivity of the process. Thus, it has been observed that an increase in the binding agent content allows the selectivity of the process to be shifted towards the formation of formic acid instead of CO (and ethylene). These results can be explained considering that the binding agent can promote the access of protons to the catalyst, which would favor the formation of formic acid. Taking all of this into account, the election of the carbon substrate for the GDE as well as the binding agent content in the CL, should be considered as important factors beyond the catalysts to achieve high CO2 conversion rates and specific target products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16020133/s1. Scheme of experimental set-ups, information of the carbon paper types used in this work, XRD and TEM graphs as well as faradaic efficiencies are included as supporting information. Refs. [24,30,38] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

V.D.: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis. R.C.: Writing—review and editing, Resources, Methodology. F.M.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Project administration. J.R.: Project administration, Writing—review and editing. C.J.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the funding of this work through projects PID2019-111416RB-I00 (Ministry of Science and Innovation of Government of Spain—MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and SBPLY/19/180501/000318 (Regional Government of Castilla-La Mancha, co-funded by EU through FEDER).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5.2) and Google Translator to translate some sentences of the work from their mother language to English or to rewrite certain phrases or expressions into more appropriate scientific language. After using this tools/services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller area analyzer |

| CL | Catalytic layer |

| CNT | Carbon nanotubes |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| GDE | Gas diffusion electrode |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ICP-AES | Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy |

| JCDPS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

| LSV | Linear sweep voltammetry |

| MEA | Membrane–electrode assembly |

| MPL | Microporous layer |

| MPS | Macroporous substrate |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| SCE | Saturated calomel electrode |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SFD | Supercritical fluid deposition |

| SPME | Solid phase microextraction |

| TCD | Thermal conductivity detector |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-Ray diffraction |

References

- United Nations Delivering the Glasgow Climate Pact, UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) at the SEC—Glasgow. In Proceedings of the Delivering the Glasgow Climate Pact, UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), Glasgow, Scotland, 31 October–12 November 2023.

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; Blanco, G.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, Y. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction on Metal Electrodes. In Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 89–189. ISBN 978-0-387-49489-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Caso, K.; Díaz-Sainz, G.; Alvarez-Guerra, M.; Irabien, A. Electroreduction of CO2: Advances in the Continuous Production of Formic Acid and Formate. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 1992–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Leung, D.Y.C.; Wang, H.; Leung, M.K.H.; Xuan, J. Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to Formic Acid. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, K.P.; Hatsukade, T.; Cave, E.R.; Abram, D.N.; Kibsgaard, J.; Jaramillo, T.F. Electrocatalytic Conversion of Carbon Dioxide to Methane and Methanol on Transition Metal Surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14107–14113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Xie, S.; Liu, T.; Fan, Q.; Ye, J.; Sun, F.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y. Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to Ethylene and Ethanol through Hydrogen-Assisted C–C Coupling over Fluorine-Modified Copper. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhai, P.; Li, A.; Wei, B.; Si, K.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Q.; Gu, X.; et al. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction to Ethylene by Ultrathin CuO Nanoplate Arrays. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiee, H.; Ge, L.; Zhang, X.; Hu, S.; Li, M.; Yuan, Z. Gas Diffusion Electrodes (GDEs) for Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide, Carbon Monoxide, and Dinitrogen to Value-Added Products: A Review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1959–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, A.; Rieg, C.; Hierlemann, T.; Salas, N.; Kopljar, D.; Wagner, N.; Klemm, E. Influence of Temperature on the Performance of Gas Diffusion Electrodes in the CO2 Reduction Reaction. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 4497–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.Y.; Choi, J.H. The Effect of a Modified Nafion Binder on the Performance of a Unitized Regenerative Fuel Cell (URFC). J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, E.A.; Lee, S.Y.; Lim, T.H.; Yoon, S.P.; Hwang, I.C.; Jang, J.H. The Effects of Nafion® Ionomer Content in PEMFC MEAs Prepared by a Catalyst-Coated Membrane (CCM) Spraying Method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xuan, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, C. Influence and Optimization of Gas Diffusion Layer Porosity Distribution along the Flow Direction on the Performance of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Aldave, S.; Andreoli, E. Fundamentals of Gas Diffusion Electrodes and Electrolysers for Carbon Dioxide Utilisation: Challenges and Opportunities. Catalysts 2020, 10, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Dinh, C.T. Gas Diffusion Electrode Design for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7488–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samu, A.A.; Szenti, I.; Kukovecz, Á.; Endrődi, B.; Janáky, C. Systematic Screening of Gas Diffusion Layers for High Performance CO2 Electrolysis. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, F.C.; Ismail, M.S.; Ingham, D.B.; Hughes, K.J.; Ma, L.; Lyth, S.M.; Pourkashanian, M. Alternative Architectures and Materials for PEMFC Gas Diffusion Layers: A Review and Outlook. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 166, 112640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Choo, H.L.; Ahmad, H.; Sivasankaran, P.N. Pore Parameter Selection for Fused Deposition Modeling of Gas Diffusion Layers in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Du, T.; Ren, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Miao, J.; Liu, Z. A Review of Carbon Materials for Supercapacitors. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 111017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, F.; Chamier, J.; Tanaka, S. Membrane Electrode Assembly Performance of a Standalone Microporous Layer on a Metallic Gas Diffusion Layer. J. Power Sources 2020, 464, 228222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-G.; Sohn, Y.-J.; Yang, T.-H.; Yoon, Y.-G.; Lee, W.-Y.; Kim, C.-S. Effect of PTFE Contents in the Gas Diffusion Media on the Performance of PEMFC. J. Power Sources 2004, 131, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Huang, H.; Lu, T.; Wang, Z.-J.; Zhu, S.; Jin, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Lv, J.-J.; Wang, S. Monitoring of Anodic Corrosion on Carbon-Based Gas Diffusion Layer in a Flow Cell. Carbon N. Y. 2023, 205, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, W. One-Step Synthesized CuS and MWCNTs Composite as a Highly Efficient Counter Electrode for Quantum Dot Sensitized Solar Cells. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Cerrillo, M.I.; Martínez, F.; Camarillo, R.; Quiles, R.; Rincón, J. Synthesis of Cu-Based Nanoparticulated Electrocatalysts for CO2 Electroreduction by Supercritical Fluid Deposition. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 186, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; García, J.; Martínez, F.; Camarillo, R.; Rincón, J. Cu Nanoparticles Deposited on CNT by Supercritical Fluid Deposition for Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 in a Gas Phase GDE Cell. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 337, 135663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolini, E.; Giorgi, L.; Pozio, A.; Passalacqua, E. Influence of Nafion Loading in the Catalyst Layer of Gas-Diffusion Electrodes for PEFC. J. Power Sources 1999, 77, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajna, M.S.; Zavahir, S.; Popelka, A.; Kasak, P.; Al-Sharshani, A.; Onwusogh, U.; Wang, M.; Park, H.; Han, D.S. Electrochemical System Design for CO2 Conversion: A Comprehensive Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, L.M.; Koopman, C.I.; Forner-Cuenca, A.; Vermaas, D.A. Narrow Pressure Stability Window of Gas Diffusion Electrodes Limits the Scale-Up of CO2 Electrolyzers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 4683–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatsukade, T.; Kuhl, K.P.; Cave, E.R.; Abram, D.N.; Jaramillo, T.F. Insights into the Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 on Metallic Silver Surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 13814–13819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo, M.I.; Jiménez, C.; Ortiz, M.Á.; Camarillo, R.; Rincón, J.; Martínez, F. Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with N/B Co-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide Based Catalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 127, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, J.; Shi, Z.; Holdcroft, S. Hydrocarbon Proton Conducting Polymers for Fuel Cell Catalyst Layers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Mashio, T.; Horibe, N.; Akizuki, K.; Ohma, A. Analysis of the Microstructure Formation Process and Its Influence on the Performance of Polymer Electrolyte Fuel-Cell Catalyst Layers. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Cerrillo, M.I.; Martínez, F.; Camarillo, R.; Rincón, J. Effect of Carbon Support on the Catalytic Activity of Copper-Based Catalyst in CO2 Electroreduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 248, 117083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Chen, Z.; Ye, S.; Wiley, B.J.; Meyer, T.J.; Du, J.-L.; Chen, Z.-F.; Ye, S.-R.; Wiley, B.J.; Meyer, T.J. Copper as a Robust and Transparent Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Meyer, T.J.; Chen, Z.; Meyer, T.J. Copper(II) Catalysis of Water Oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Wu, X.; Sun, L. Copper-Based Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysts for Electrochemical Water Oxidation. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 4187–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Jiménez, C.; Martínez, F.; Camarillo, R.; Rincón, J. Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 Using Pb Catalysts Synthesized in Supercritical Medium. J. Catal. 2018, 367, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arán-Ais, R.M.; Rizo, R.; Grosse, P.; Algara-Siller, G.; Dembélé, K.; Plodinec, M.; Lunkenbein, T.; Chee, S.W.; Cuenya, B.R. Imaging Electrochemically Synthesized Cu2O Cubes and Their Morphological Evolution under Conditions Relevant to CO2 Electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.