A Recyclable Thermoresponsive Catalyst for Highly Asymmetric Henry Reactions in Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

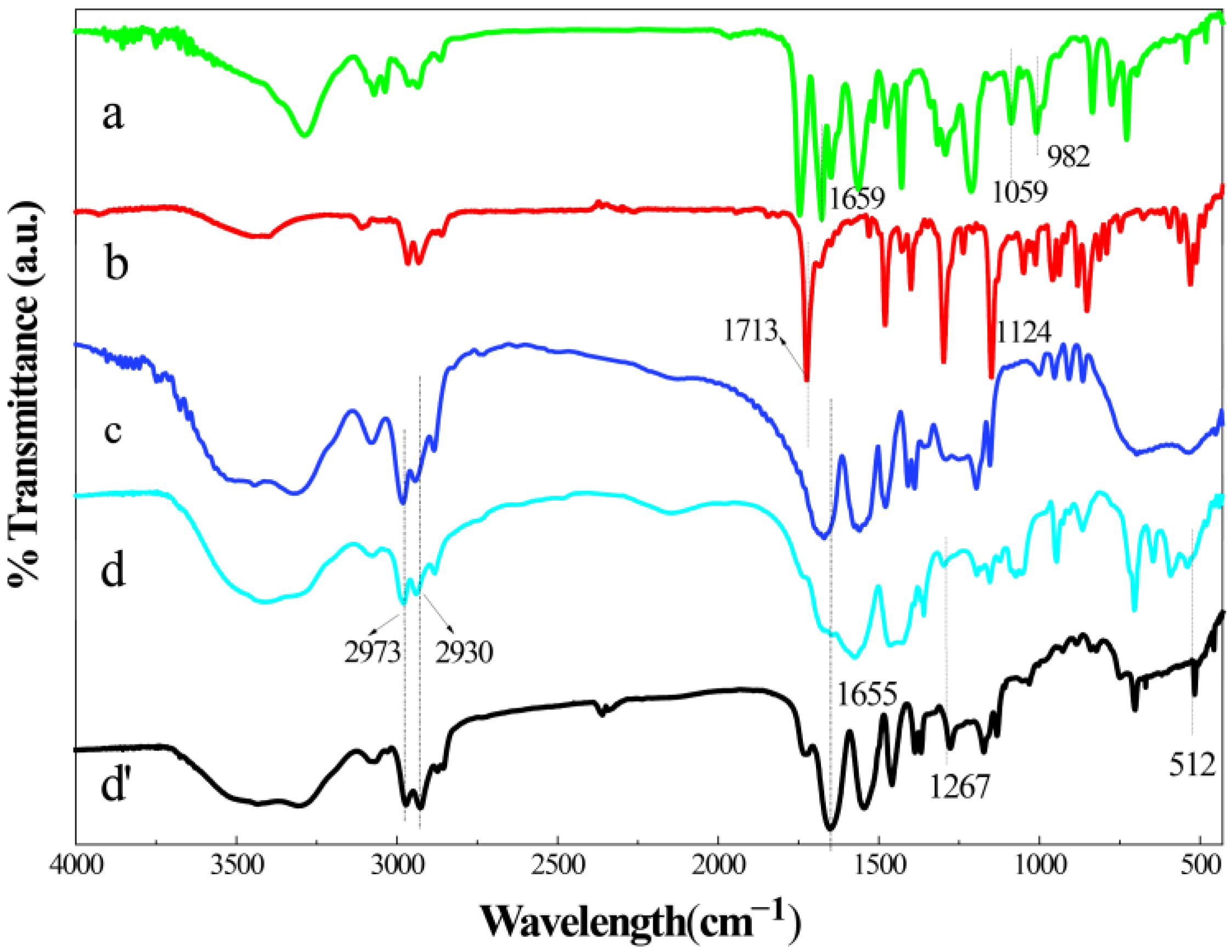

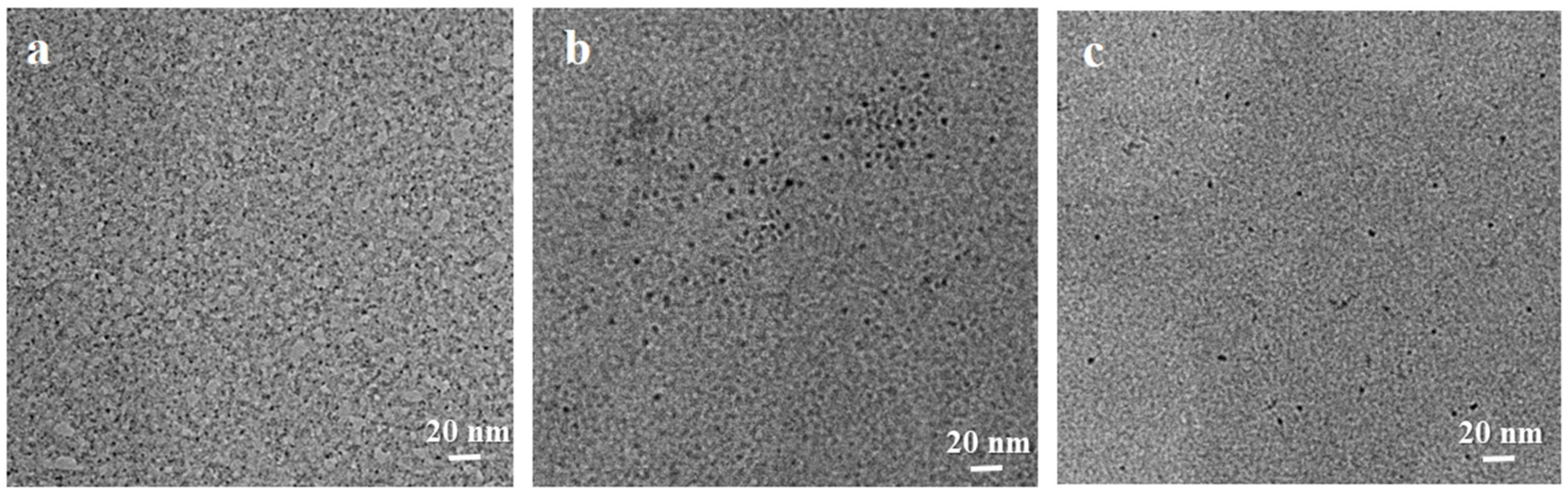

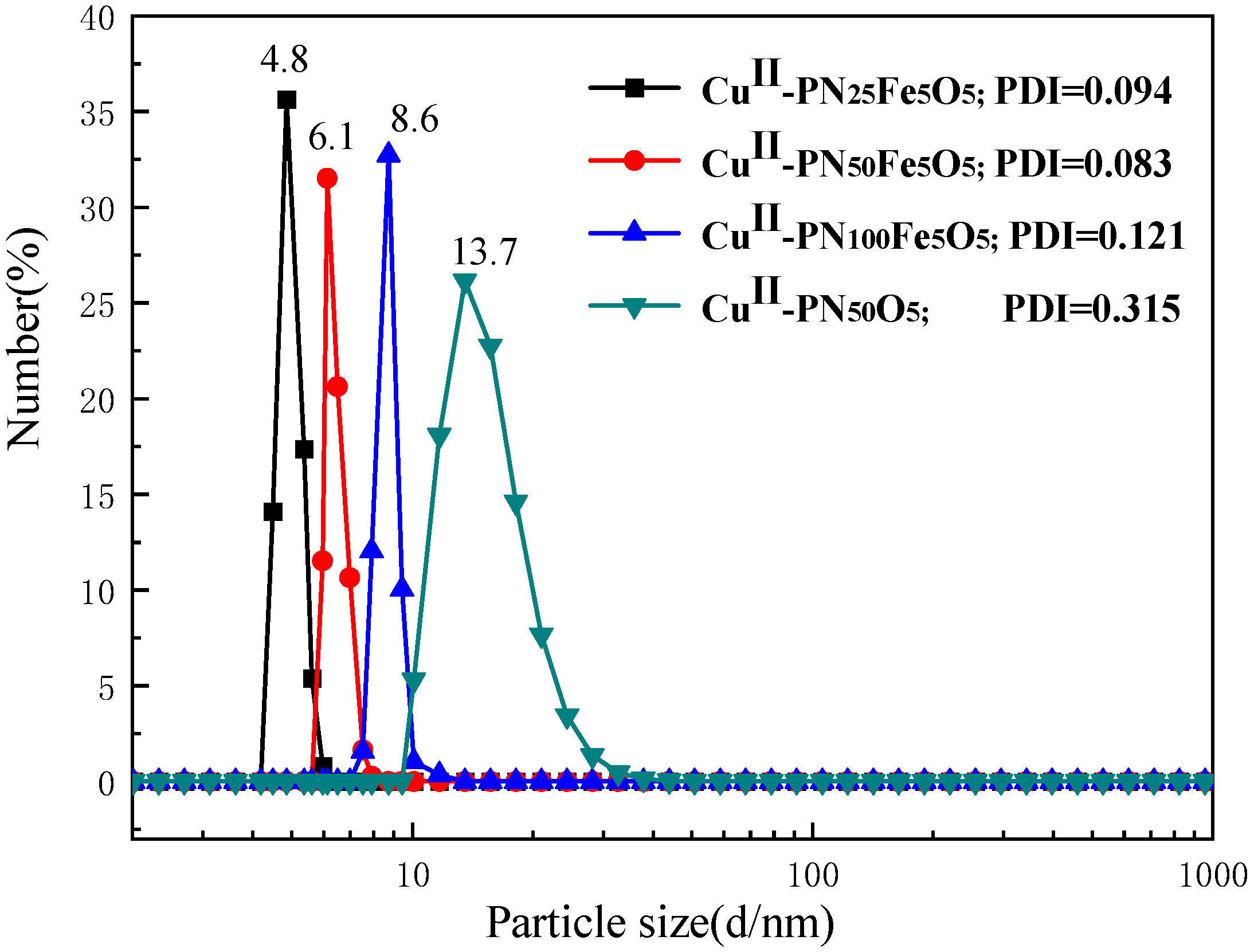

2.1. Characterization of Materials Structure

2.2. Catalytic Activity of CuII-PN50Fe5O5 Catalyst

2.2.1. Optimization of Reaction Conditions

2.2.2. Expansion of Reaction Substrates

2.3. Recycle and Reuse of CuII-PN50Fe5O5

3. Experiment

3.1. Materials

3.2. Analytical Methods

3.3. Synthesis of Catalysts

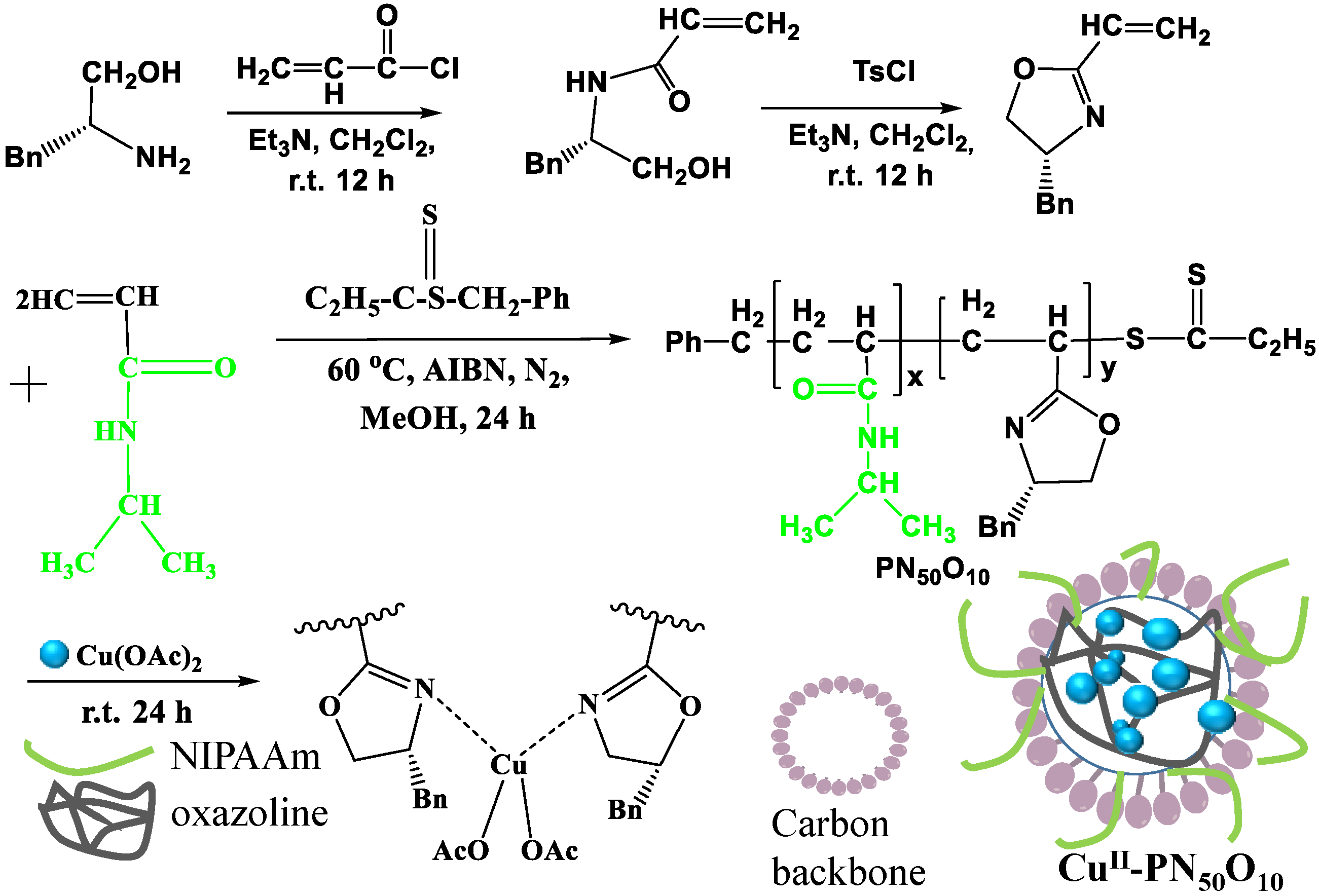

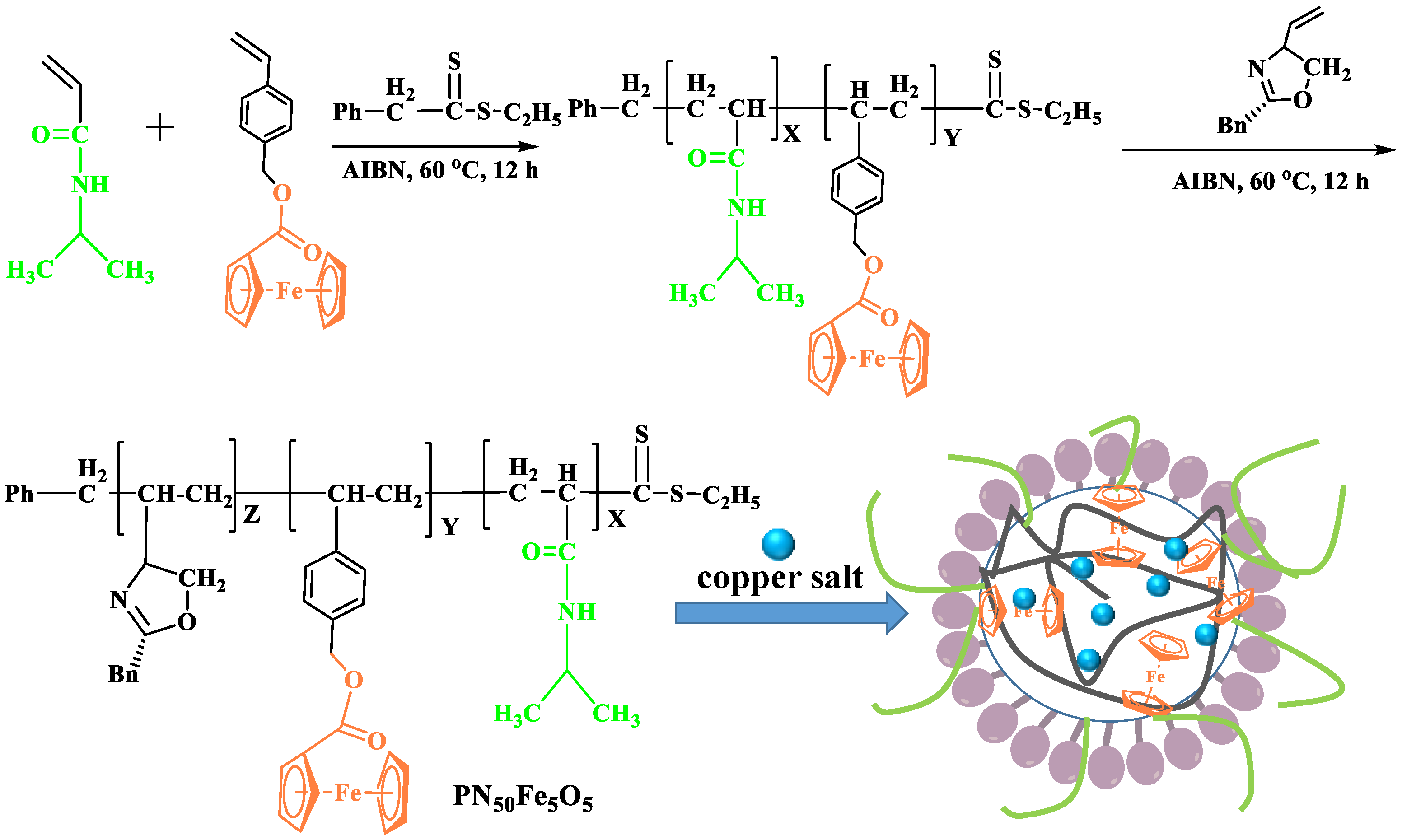

3.3.1. Preparation of the Diblock Azolein Cu Catalyst CuII-PN50O5

3.3.2. Cu(II) Loading onto Supported Material Composite

3.4. Catalytic Activity Tests of CuII-PNxFeyO5 Catalyst

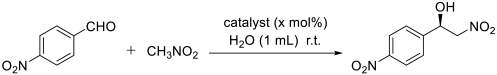

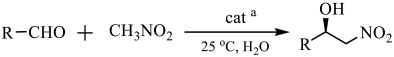

3.4.1. General Procedure for CuII-PNxFeyO5 Catalyzed Asymmetric Henry Reaction in Aqueous Phase

3.4.2. Determination of Optimum Test Conditions

3.5. Recycling and Reusing of CuII-PNxFeyO5

4. Conclusions

- (1)

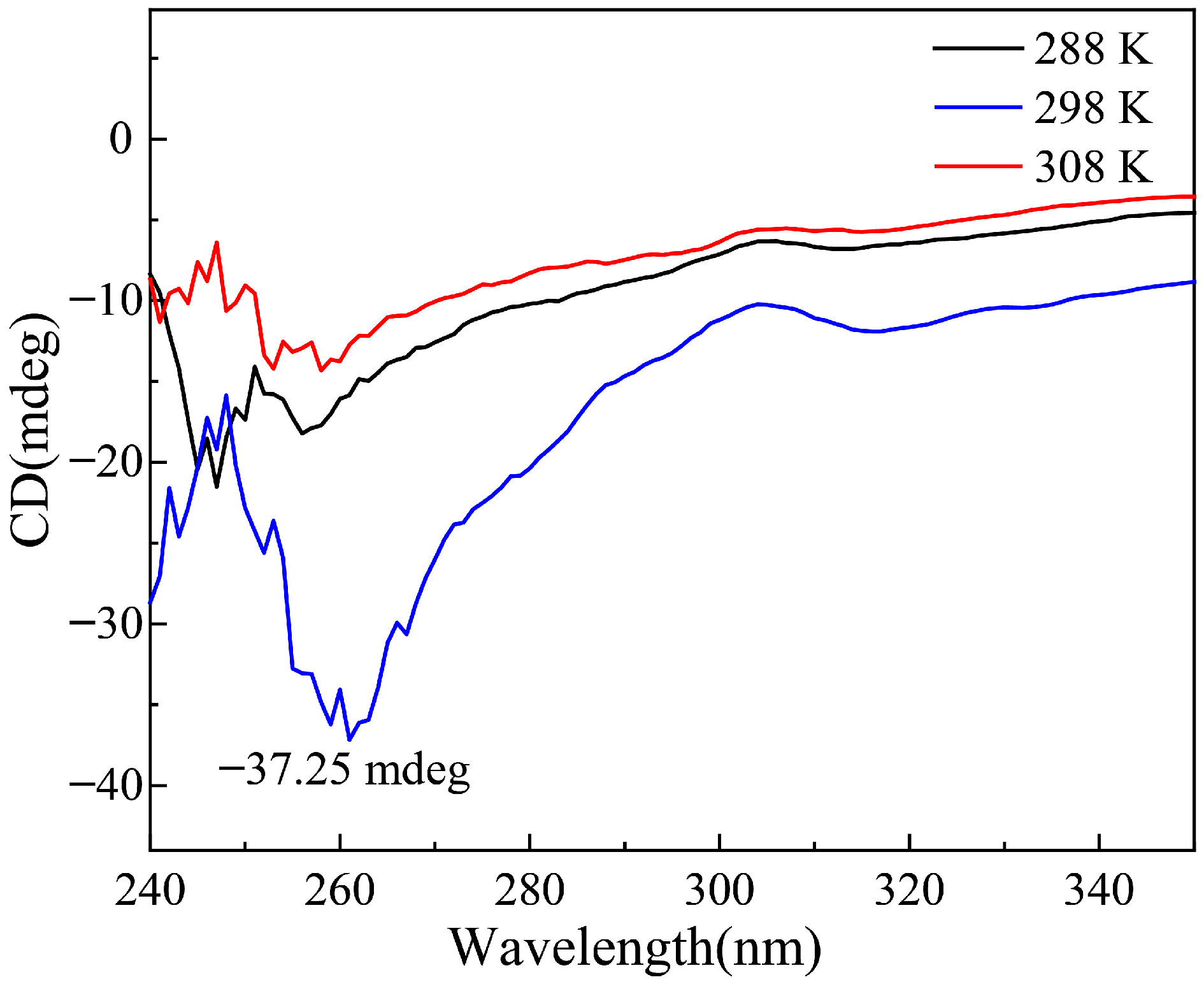

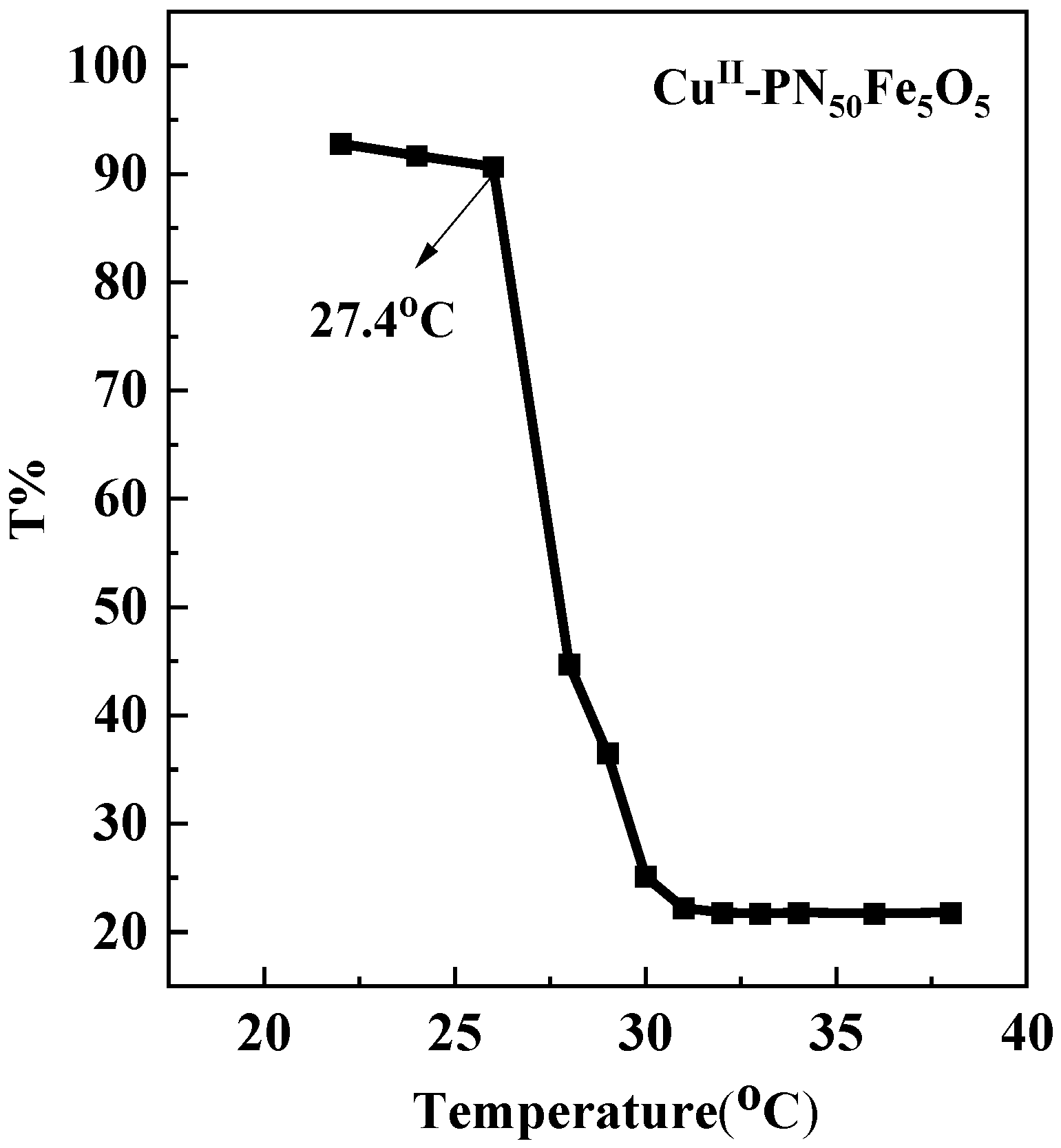

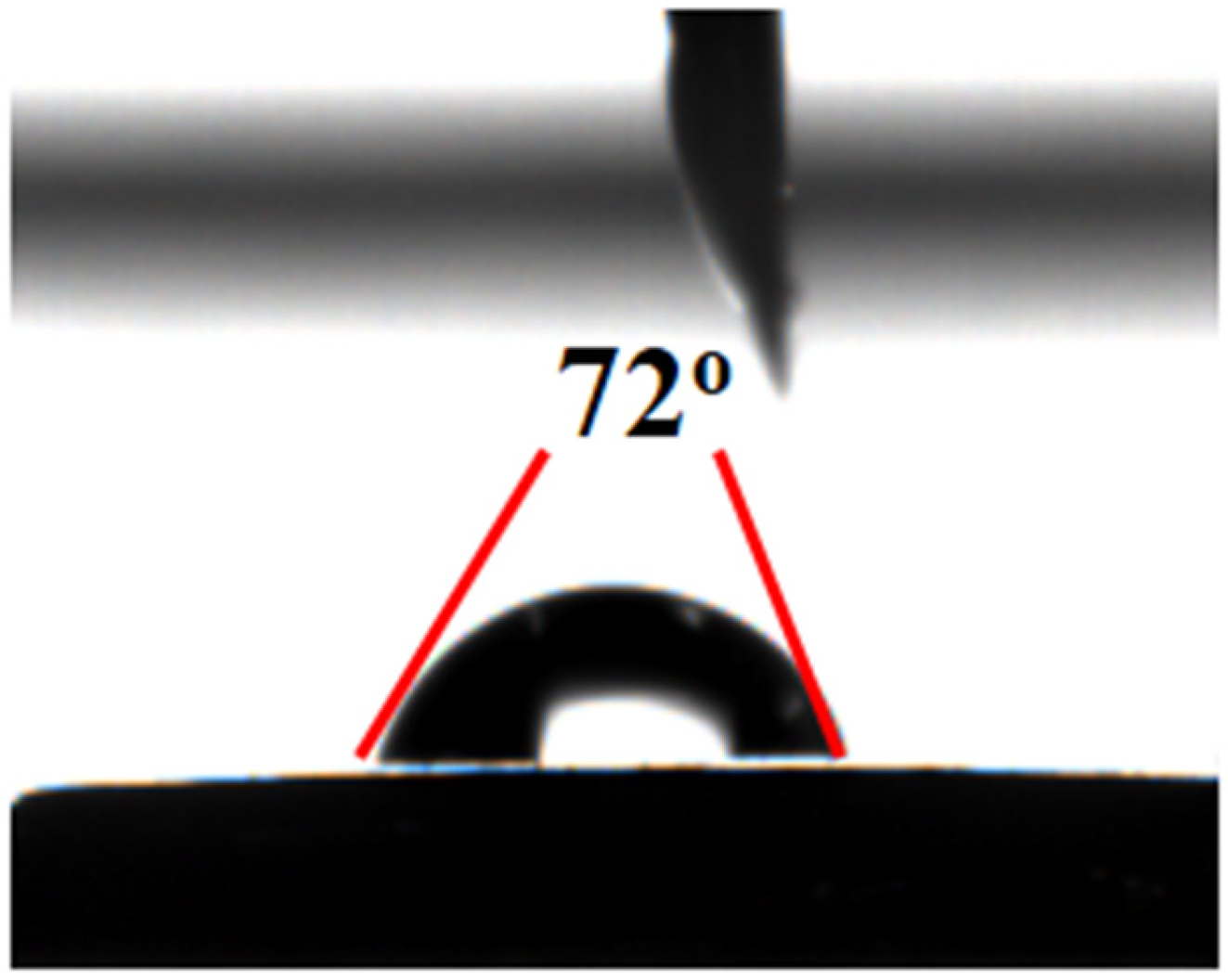

- A thermosensitive, single-chain triblock polymer (comprising NIPAAm as the thermosensitive unit, a ferrocene unit, and an oxazoline unit) was designed and synthesized via reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization. This polymer was then coordinated with copper acetate to yield a class of biomimetic, single-chain aggregated chiral oxazoline–copper catalysts, denoted as CuII-PNxFeyOz. For comparison, a control catalyst lacking the ferrocene unit, CuII-PN50O5, was also prepared to elucidate the role of ferrocene in the system. The structures of these catalysts and their self-assembled morphologies in water were confirmed through characterization by FT-IR, TEM, DLS, and CD.

- (2)

- This series of catalysts is fully water-soluble and undergoes intramolecular folding in aqueous solution to form single-chain nanoparticles, driven by hydrophobic interactions and metal coordination. As catalysis proceeds at 25 °C, the hydrophilic segments encapsulate the hydrophobic active sites, mimicking biological systems. The catalytic activity of the triblock catalysts was significantly higher than that of both a traditional chiral oxazoline–copper catalyst (NC-Bn-Cu) and the diblock control catalyst (CuII-PN50O5). CuII-PN50Fe5O5 showed the highest activity, and the nanoreactor effect enhances its enantioselectivity.

- (3)

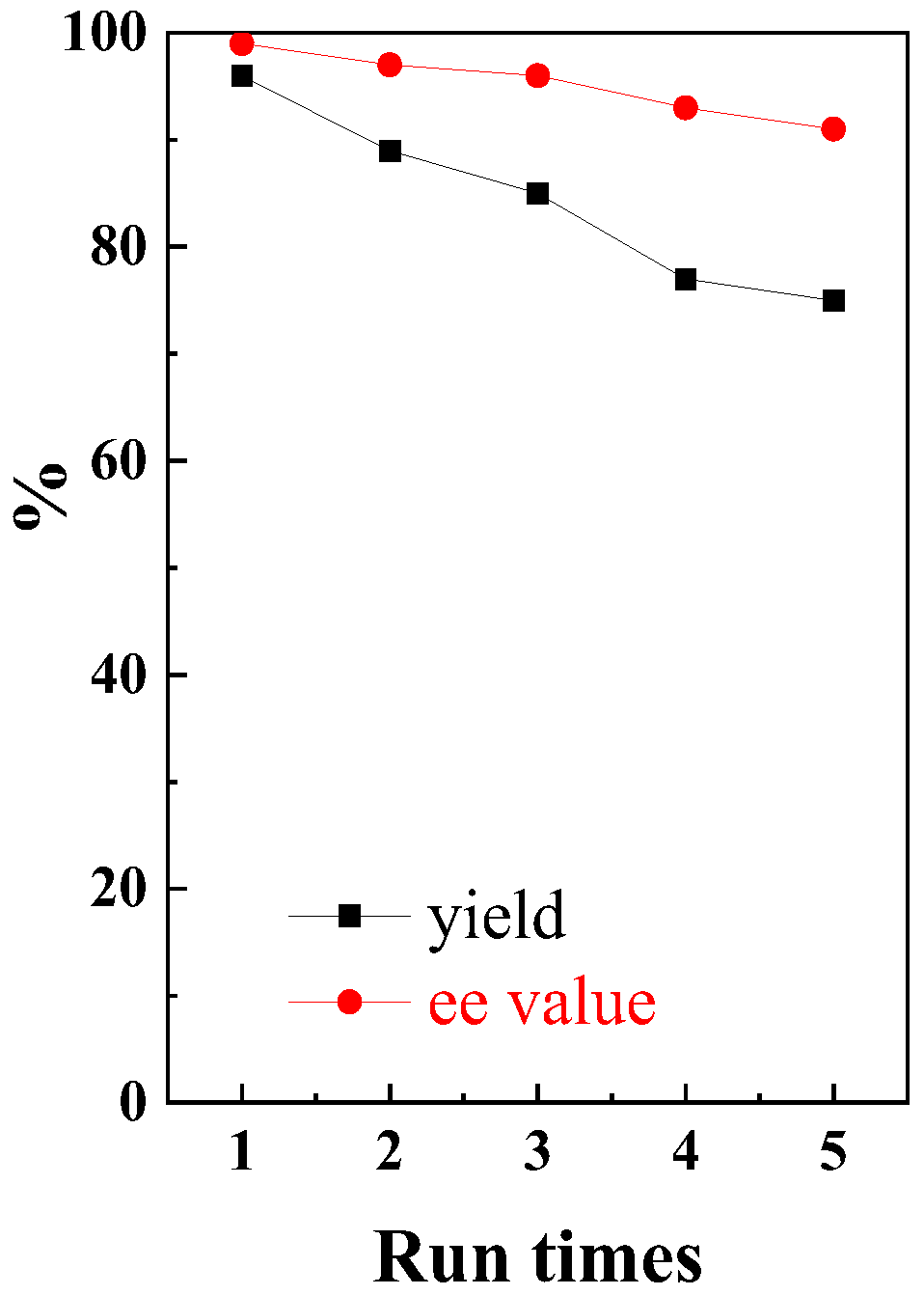

- While the catalyst (CuII-PNxFeyO5) is soluble in water at 25 °C, it can be recovered post-reaction by leveraging its thermosensitive property. Raising the temperature of the reaction mixture triggers the precipitation of the hydrophobic catalyst as a solid, allowing for convenient separation. However, this recovery process was accompanied by the leaching of copper ions. Consequently, after four reuse cycles, both the yield and enantioselectivity showed a notable decrease. Thus, although the catalyst can be readily recovered, its reusability remains limited under the current post-treatment conditions.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z. Recent progress in copper catalyzed asymmetric Henry reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K.; Hirota, S.; Fujino, A.; Ishihara, K.; Shioiri, T.; Matsugi, M. Asymmetric Henry reaction using a double fluorous-tagged Co-salen complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 99, 153833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, W.; Sun, X.; Zou, H.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Z. Optically active helical polymers bearing cinchona alkaloid pendants: An efficient chiral organocatalyst for asymmetric Henry reaction. Polym. Chem. 2025, 16, 1869–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Tu, Y. Construction of polyfunctionalized 6-5-5 fused tricyclic carbocycles via one-pot sequential semipinacol rearrangement/Michael addition/Henry reaction. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2076–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konev, V.N.; Pai, Z.P.; Khlebnikova, T.B. Synthesis of new chiral secondary 1,2-diamines based on levopimaric acid and their use as ligands in copper(II)-catalyzed asymmetric Henry reaction. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 4, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.; Srinivas, D.; Ratnasamy, P. EPR and catalytic investigation of Cu(salen) complexes encapsulated in zeolites. J. Catal. 1999, 188, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Mistri, S. Schiff base based metal complexes: A review of their catalytic activity on aldol and Henry reaction. Commen. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 43, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Lin, L.; Yang, J.; Sun, M.; Li, F.; Li, B.; Yao, Y. A new low-cost and effective method for enhancing the catalytic performance of Cu-SiO2 catalysts for the synthesis of ethylene glycol via the vapor-phase hydrogenation of dimethyl oxalate by coating the catalysts with dextrin. J. Catal. 2017, 350, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xia, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Tan, C.; Cui, Y. Chiral covalent organic frameworks with high chemical stability for heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8693–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureshy, R.I.; Das, A.; Khan, N.H.; Abdi, S.H.R.; Bajaj, H.C. Cu(II)-macrocylic [H4] salen catalyzed asymmetric nitroaldol reaction and its application in the synthesis of α1-adrenergic receptor agonist (R)-phenylephrine. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-L.; Yang, K.-F.; Li, F.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, L.-W. Probing the evolution of an ar-binmol-derived salen-Co(III) complex for asymmetric Henry reactions of aromatic aldehydes: Salen-Cu(II) versus salen-Co(III) catalysis. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 37859–37867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Dong, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dai, L.; Zhang, M. The first 4,4′-imidazolium-tagged C2-symmetric bis(oxazolines): Application in the asymmetric Henry reaction. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 4758–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.A.; Seidel, D.; Rueping, M.; Lam, H.W.; Shaw, J.T.; Downey, C.W. A new copper acetate-bis(oxazoline)-catalyzed, enantioselective Henry reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12692–12693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuchuryukin, A.V.; Huang, R.; Lutz, M.; Chadwick, J.C.; Spek, A.L.; van Koten, G. NCN-pincer metal complexes (Ti, Cr, V, Zr, Hf, and Nb) of the phebox ligand (S,S)-2,6-Bis(4′-isopropyl-2′-oxazolinyl)phenyl. Organometallics 2011, 30, 2819–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.; Mondal, J.; Zhao, Y. Urea–pyridine bridged periodic mesoporous organosilica: An efficient hydrogen-bond donating heterogeneous organocatalyst for Henry reaction. J. Catal. 2015, 330, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Duraimurugan, K.; Siva, A. A new series of bipyridine based chiral organocatalysts for enantioselective Henry reaction. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 7148–7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branneby, C.; Carlqvist, P.; Magnusson, A.; Hult, K.; Brinck, T.; Berglund, P. Carbon-carbon bonds by hydrolytic enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 874–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuryev, R.; Briechle, S.; Gruber-Khadjawi, M.; Griengl, H.; Liese, A. Asymmetric retro-Henry reaction catalyzed by hydroxynitrile lyase from hevea brasiliensis. Chemcatchem 2010, 2, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Lin, X. Enzymatic synthesis of optical pure β-nitroalcohols by combining D-aminoacylase-catalyzed nitroaldol reaction and immobilized lipase PS-catalyzed kinetic resolution. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, G.; Le, Z. The Henry reaction in [Bmim][PF6]-based microemulsions promoted by acylase. Molecules 2013, 18, 13910–13919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schätz, A.; Grass, R.N.; Kainz, Q.; Stark, W.J.; Reiser, O. Cu(II)-azabis(oxazoline) complexes immobilized on magnetic Co/C nanoparticles: Kinetic resolution of 1,2-diphenylethane-1,2-diol under batch and continuous-flow conditions. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, B.; García, J.I.; Herrerías, C.I.; Mayoral, J.A.; Miñana, A.C. Polytopic bis(oxazoline)-based ligands for recoverable catalytic systems applied to the enantioselective Henry reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 9314–9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Deng, P.; Zeng, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, H. Anti-selective asymmetric Henry reaction catalyzed by a heterobimetallic Cu-Sm-aminophenol sulfonamide complex. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1578–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedasso, G.D.; Tzou, D.M.; Chung, P. Amino group functionalized pitch-based carbocatalyst for the Henry reaction of furfural. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E 2024, 158, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulauf, A.; Mellah, M.; Schulz, E. New chiral thiophene-salen chromium complexes for the asymmetric Henry reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2242–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.D.; Shaw, S. A new catalyst for the asymmetric Henry reaction: Synthesis of β-nitroethanols in high enantiomeric excess. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6270–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, P.K.; Murugesan, S.; Siva, A. Highly enantioselective asymmetric Henry reaction catalyzed by novel chiral phase transfer catalysts derived from cinchona alkaloids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 10101–10109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Mishra, A.K.; Hussain, M.Z.; Peraman, R.; Jana, A. Breaking base dependency: EDC·HCl-promoted Henry reaction under solvent-free mild acidic conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 15508–15518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W. Cu-diamine ligand-controlled asymmetric Henry reactions and their application in concise total syntheses of linezolid and rivaroxaban. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 35292–35295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, R.; Mannepalli, L.K.; Rathod, V. Kinetics of Henry reaction catalyzed by fluorapatite. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 181, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, F.; Fink, F.; Schier, W.S.; Soerensen, S.; Petrunin, A.V.; Richtering, W.; Herres Pawlis, S.; Pich, A. Catalyzed Henry reaction by compartmentalized copper-pyrazolyl-complex modified microgels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yao, B.; Wang, J.; Leng, Y.; Xu, W.; Dong, Y. Chiral pool-engineered homochiral covalent organic frameworks for catalytic asymmetric synthesis of drug intermediate. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 17029–17032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Han, B.; Li, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L. Controllable preparation of chiral oxazoline-Cu(II) catalyst as nanoreactor for highly asymmetric Henry reaction in water. Catal. Lett. 2022, 152, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Fu, C.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Zhu, L. Cellulose supported TiO2/Cu2O for highly asymmetric conjugate addition of α,β-unsaturated compounds in aqueous phase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, R.; Gao, M.; Hao, P.; Yin, D. Bio-inspired single-chain polymeric nanoparticles containing a chiral salen TiIV complex for highly enantioselective sulfoxidation in water. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Fu, C.; Fang, Z.; Xiong, B.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Zhu, L. Chitosan nanoreactor modified with PNIPAAm as efficient catalyst for preparation of chiral boron compounds in aqueous phase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, A.; Liu, C.; Cheng, J.; Hu, M. Helical polyether-immobilized chiral aza-bis(oxazolines): Synthesis and synergistic effect on the enantioselectivity of Zn-catalyzed Henry reaction. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 194, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Bi, F.; Ye, J.; Guo, X.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, W.; Guo, X. Partially carbonized chiral polymer with Cu-bis(oxazoline) as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for asymmetric Henry reaction. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 10794–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Feng, L.; Jiang, L. Thermo-driven controllable emulsion separation by a polymer-decorated membrane with switchable wettability. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2018, 57, 5740–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyakkumar, P.; Liang, Y.; Guo, M.; Lu, S.; Xu, D.; Li, X.; Guo, B.; He, G.; Chu, D.; Zhang, M. Emissive metallacycle-crosslinked supramolecular networks with tunable crosslinking densities for bacterial imaging and killing. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2020, 59, 15199–15203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbe, A.; Pomposo, J.A.; Asenjo-Sanz, I.; Bhowmik, D.; Ivanova, O.; Kohlbrecher, J.; Colmenero, J. Single chain dynamic structure factor of linear polymers in an all-polymer nano-composite. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Chang, F.; Yen, H.; Lee, D.; Chiu, C.; Xin, Z. Supramolecular assembly mediates the formation of single-chain polymeric nanoparticles. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 1184–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C.; Massiot, A.; Dolcher, E.; Blacque, O.; Cariou, K.; Gasser, G. Synthesis of 1,2-fluorinated ferrocenes and 1,3-fluorinated ferrocenes. Organometallics 2025, 44, 2182–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, M.; Cellini, F.; Cacciotti, I.; Peterson, S.D.; Porfiri, M. In situ temperature sensing with fluorescent chitosan-coated pnipaam/alginate beads. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 12506–12512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, J.; He, H.; Ma, S.; Yao, J. Flame-retardant PNIPAAm/sodium alginate/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels used for fire-fighting application: Preparation and characteristic evaluations. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 255, 117485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Xu, S.; Xu, J.; He, J. Preparation and properties of a multi-crosslinked chitosan/sodium alginate composite hydrogel. Mater. Lett. 2024, 354, 135414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, M.S.; Scheerer, S.; Linseis, M.; White, A.J.P.; Winter, R.F.; Albrecht, T.; Long, N.J. Oligomeric ferrocene rings. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Feng, A.; Liu, S.; Huo, M.; Fang, T.; Wang, K.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, J. Electrochemical stimulated pickering emulsion for recycling of enzyme in biocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2016, 8, 29203–29207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Werlé, M.; Nano, A.; Maisse-François, A.; Bellemin-Laponnaz, S. Asymmetric benzoylation and Henry reaction using reusable polytopic bis(oxazoline) ligands and copper(II). New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 4748–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Qu, Y.; Liu, C.; Khan, H.; Sun, P.; Zhang, W. Redox-responsive multicompartment vesicles of ferrocene-containing triblock terpolymer exhibiting on-off switchable pores. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, R.; Zhao, G.; Luo, X.; Xing, C.; Yin, D. Thermo-responsive self-assembled metallomicelles accelerate asymmetric sulfoxidation in water. J. Catal. 2016, 335, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Smith, A.E.; Kirkland, S.E.; Mccormick, C.L. Aqueous raft synthesis of pH-responsive triblock copolymer mPEO-PAPMA-PDPAEMA and formation of shell cross-linked micelles. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 8429–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromova, O.V.; Yashkina, L.V.; Stoletova, N.V.; Maleev, V.I.; Belokon, Y.N.; Larionov, V.A. Selectivity Control in Nitroaldol (Henry) Reaction by Changing the Basic Anion in a Chiral Copper(II) Complex Based on (S)-2-Aminomethylpyrrolidine and 3,5-Di-tert-butylsalicylaldehyde. Molecules 2024, 29, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionov, V.A.; Yashkina, L.V.; Medvedev, M.G.; Smol’yakov, A.F.; Peregudov, A.S.; Pavlov, A.A.; Eremin, D.B.; Savel’yeva, T.F.; Maleev, V.I.; Belokon, Y.N. Henry Reaction Revisited. Crucial Role of Water in an Asymmetric Henry Reaction Catalyzed by Chiral NNO-Type Copper(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 11051–11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Fu, W.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Z.; Tan, R.; Yin, D. Titanium(IV)-folded single-chain nanoparticles as artificial metalloenzyme for asymmetric sulfoxidation in water. Chem. Commun. 2018, 68, 9430–9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckennon, M.J.; Meyers, A.I.; Drauz, K.; Schwarm, M. A convenient reduction of amino acids and their derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Meng, J.; Lv, H.; Zhang, X. Highly regio- and enantioselective synthesis of γ,δ-unsaturated amido esters by catalytic hydrogenation of conjugated enamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2015, 54, 1885–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst a | CH3NO2 | Catalyst Amount (mol) | Time (h) | Yield b (%) | ee c (%) |

| 1 | Cu(CH3COO)2 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | / | / |

| 2 | Cu(CH3COO)2 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 48 | 4 | / |

| 3 | NC-Bn-Cu | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 20 | 35 |

| 4 | NC-Bn-Cu | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 48 | 31 | 35 |

| 5 | CuII-PN50O5 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 63 | 99 |

| 6 | CuII-PN50O5 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 18 | 92 | 99 |

| 7 | CuII-PN25Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 78 | 99 |

| 8 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 96 | 99 |

| 9 | CuII-PN100Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 87 | 95 |

| 10 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 0.5% | 12 | 14 | 99 |

| 11 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 1.0% | 12 | 33 | 99 |

| 12 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 1.5% | 12 | 58 | 99 |

| 13 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 2.5% | 12 | 93 | 99 |

| 14 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 3 mmol | 3.0% | 12 | 93 | 99 |

| 15 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 1 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 19 | 99 |

| 16 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 2 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 65 | 99 |

| 17 | CuII-PN50Fe5O5 | 4 mmol | 2.0% | 12 | 97 | 99 |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

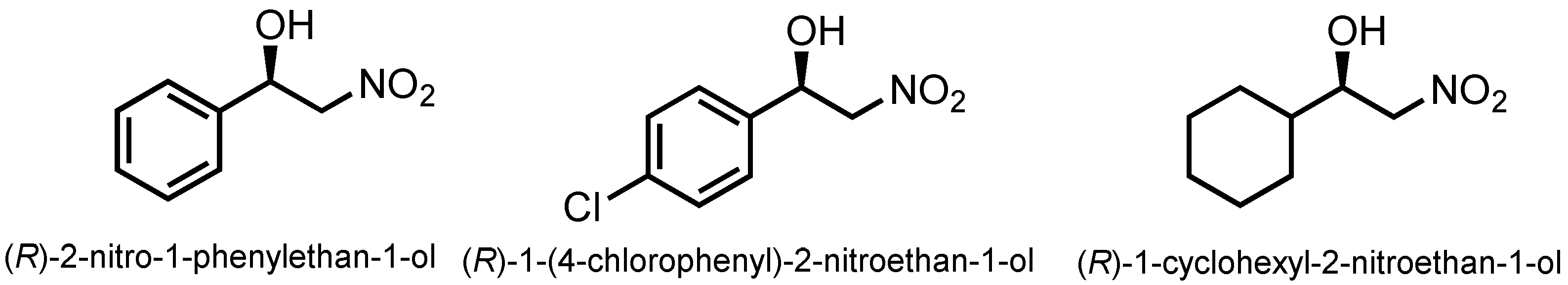

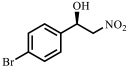

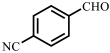

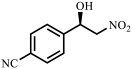

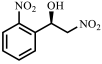

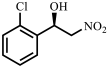

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield b (%) | ee c (%) |

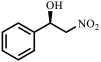

| 1 |  |  | 31 | 87 |

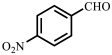

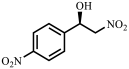

| 2 |  |  | 96 | 99 |

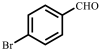

| 3 |  |  | 35 | 85 |

| 4 |  |  | 63 | 92 |

| 5 |  |  | 88 | 99 |

| 6 |  |  | 30 | 90 |

| 7 |  |  | 19 | 87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Qu, X.; Li, X.; Xiong, B.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L. A Recyclable Thermoresponsive Catalyst for Highly Asymmetric Henry Reactions in Water. Catalysts 2026, 16, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020132

Wang M, Zhang Y, Jiang Z, Zhong Y, Qu X, Li X, Xiong B, Liu X, Zhu L. A Recyclable Thermoresponsive Catalyst for Highly Asymmetric Henry Reactions in Water. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020132

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Meng, Yaoyao Zhang, Zifan Jiang, Yanhui Zhong, Xinzheng Qu, Xingling Li, Bo Xiong, Xianxiang Liu, and Lei Zhu. 2026. "A Recyclable Thermoresponsive Catalyst for Highly Asymmetric Henry Reactions in Water" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020132

APA StyleWang, M., Zhang, Y., Jiang, Z., Zhong, Y., Qu, X., Li, X., Xiong, B., Liu, X., & Zhu, L. (2026). A Recyclable Thermoresponsive Catalyst for Highly Asymmetric Henry Reactions in Water. Catalysts, 16(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020132