Abstract

In this study, three distinct hydrolysates, which are designated Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, were generated from extrusion-pretreated Durvillaea antarctica biomass by applying viscozyme, cellulase, and α-amylase, respectively. Chemical analyses demonstrated distinct compositional differences among the extracts, whereas FTIR spectra verified the presence of fucose-containing sulfated polysaccharides. Furthermore, NMR analyses revealed pronounced structural variations among the extracts. To investigate neuroprotective properties of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, rotenone (Rot) was added to SH-SY5Y cells that had been pretreated with Dur-I/II/III. Here, flow cytometry was employed to assess changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), Bcl-2 expression, cytochrome c release, caspase-9, -8, and -3 activation, as well as DNA fragmentation. The protective effect of Dur-I/II/III pretreatment of SH-SY5Y cells on the Rot-induced death process was further investigated using cell cycle and annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/PI (propidium iodide) double staining analyses. The results reveal that the Rot-induced apoptotic factors were all recovered by the pretreatment of Dur-I/II/III. Moreover, cell cycle and annexin V-FITC/PI double staining analyses also indicated that Dur-I/II/III were capable of protecting SH-SY5Y cells from Rot-induced cytotoxicity. Therefore, these Dur extracts are considered as good candidates for the prevention and treatment of neurodegeneration induced by oxidative stress.

1. Introduction

Marine algae, particularly brown seaweeds, are rich sources of bioactive polysaccharides such as fucoidans, cellulose, and alginic acids, which exhibit antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities. These bioactivities are strongly influenced by structural features, including molecular weight, linkage type, solubility, and backbone conformation [1]. To enhance their functional properties, polysaccharides can be modified using physical, chemical, or biological approaches [2]. Physical methods change size and conformation using energy or mechanical forces [3]. Chemical methods introduce new chemical groups or bonds to alter functionality [4]. Biological methods use enzymes or microorganisms to mediate changes in polysaccharides under mild, eco-friendly conditions [3]. Generally, enzymatic modification offers high specificity, efficiency, and yield, while minimizing structural damage and side effects [3]. Recent studies indicate that enzyme-assisted extraction effectively enhances the bioactivity of seaweed-derived polysaccharides [5]. Enzyme-assisted hydrolysis has demonstrated advantages such as high yield, low cost, and simplified purification [6]. Accordingly, this study employed three food industry relevant glycoside hydrolases, namely viscozyme, cellulase, and α-amylase, to facilitate efficient polysaccharide extraction from seaweed biomass.

The prevalence of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) is steadily increasing. These diseases are characterized by progressive neuronal damage leading to cognitive or motor dysfunction and are closely associated with oxidative stress-induced cellular injury [7]. Oxidative damage contributes to both normal aging and the pathogenesis of AD and PD [8]. Neurodegeneration involves extensive neuronal loss mediated by multiple cell death pathways, including apoptosis and autophagy-related mechanisms [9]. Given the multifactorial nature of neuronal death, enhancing endogenous antioxidant defenses represents a promising therapeutic strategy. Thus, identifying natural neuroprotective compounds with antioxidant activity and minimal side effects remains a critical research priority.

Rotenone is a naturally occurring pesticide that inhibits mitochondrial Complex I, inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. It is widely used in neuronal cell models to evaluate neuroprotective effects against mitochondria-mediated toxicity [10]. Moreover, extrusion cooking is a high temperature, short time process widely used in the food industry for cereal and protein processing through shear induced structural modification [11]. Despite its effectiveness in altering biomaterials, its application for enhancing polysaccharide extraction remains relatively underexplored. Building on our previous work [6], extrusion-pretreated Durvillaea antarctica was hydrolyzed using viscozyme, cellulase, or α-amylase to compare the physicochemical properties and bioactivities of the resulting products. Structural and compositional analyses were performed using FTIR, HPLC, NMR, and related assays. Neuroprotective effects were evaluated in rotenone-treated SH-SY5Y cells. This study is the first to demonstrate the potential of enzyme-derived hydrolysates from extrusion-pretreated D. antarctica as natural neuroprotective agents relevant to Parkinson’s disease. In contrast to conventional fucoidan extraction methods, the novelty of this study lies in the simultaneous comparison of the compositional and structural differences among products obtained through enzyme assisted extraction using viscozyme, cellulase, and α amylase. In addition, the neuroprotective effects of the extracts produced by these three enzymes were systematically evaluated, and their potential protective mechanisms were also elucidated. The findings of this study provide a scientific basis for the future development of neuroprotective functional food ingredients and for drug discovery and development targeting neurodegenerative disorders.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of Enzyme Extracts (Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III) from Extrusion-Pretreated D. antarctica and Physicochemical Characteristics of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III

In this study, dried and milled D. antarctica biomass was subjected to an extrusion-pretreatment procedure to disrupt the cell wall matrix prior to enzymatic hydrolysis. Subsequent hydrolysis with viscozyme, cellulase, or α-amylase produced three enzyme assisted extraction-derived extracts, designated Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. The processing parameters for extrusion-pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis are summarized in Table 1. The extraction yields of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III were 41.3 ± 2.3%, 45.5 ± 3.0%, and 44.2 ± 0.8%, respectively, indicating slightly higher yields for Dur-II and Dur-III compared with Dur-I, although the differences were not substantial. In preliminary tests, non-extruded samples yielded 38.4 ± 1.1%, 43.0 ± 0.2%, and 41.4 ± 0.6% for Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, respectively. These findings demonstrate that extrusion-pretreatment enhances the extractability of bioactive components from D. antarctica. Generally, plant and algal biomass (such as D. antarctica) are inherently recalcitrant due to tightly interwoven cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and other matrix polymers. These components form a rigid, compact structure that sterically limits enzyme access to target polysaccharides. During extrusion pretreatment, the mechanical shear and compressive forces break apart the cell wall matrix, creating micro-cracks, fractures, and fiber separation. The physical disruption increases the specific surface area and pore volume, allowing enzymes deeper and more extensive access to substrates [12,13]. Extrusion can also increase biomass porosity and hydrophilicity, which promoting better swelling in aqueous environments and having improved diffusion of enzymes and water molecules into the cell wall structure. Enhanced water penetration is critical because enzyme-substrate interactions occur at hydrophilic surfaces, and swelling increases the effective surface availability for enzymatic catalysis [14]. Collectively, these mechanistic effects may explain the consistently higher extraction yields observed under extrusion-pretreatment conditions compared with non-extruded samples.

Table 1.

Hydrolysis conditions and extraction yields of the enzymatically produced hydrolysates (Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III) derived from D. antarctica.

The employment of viscozyme, cellulase, and α-amylase following an extrusion pretreatment may offer several scientific and practical benefits for extracting fucoidan compared with traditional extraction methods: (1) Seaweed cell walls are mainly composed of complex polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose) that physically entrap fucoidan. Enzymatic treatments can hydrolyze these structural components under near-neutral pH, facilitating efficient release of fucoidan without harsh chemicals or high temperatures, reducing the risk of degradation of heat-labile or acid-sensitive fucoidan chains [15]. (2) Enzyme-assisted extraction methods have been shown to improve fucoidan yields compared with conventional extraction, as enzymes break down the cell wall matrix and enhance mass transfer [16]. (3) In a commercial process, the high enzyme costs are often offset by higher yields, reduced energy consumption, and fewer processing steps relative to conventional extraction [17]. (4) Enzyme-assisted methods are inherently greener and more sustainable, as compared to hot-acid or organic solvent extraction. To compare enzyme specificity and functionality, viscozyme, a multicarbohydrase complex, hydrolyzes cellulose, hemicellulose, and β-glucans, enabling extensive cell wall degradation and improved access to intracellular fucoidan fractions [18]. Cellulase specifically targets β-1,4 glycosidic bonds in cellulose, effectively collapsing the rigid cellulose network within the seaweed cell wall. This supports enhanced mass transfer and extraction efficiency of fucoidan [19]. In contrast, α-amylase is an endo-acting glycoside hydrolase that randomly cleaves internal α-1,4-glycosidic linkages in α-linked glucose polymers. Although fucoidan itself lacks α-1,4 glucose linkages, D. antarctica biomass contains diverse α-linked glucans and storage polysaccharides embedded within a complex matrix of alginate, cellulose, and heteropolysaccharides. Hydrolysis of these non-target components by α-amylase reduces matrix integrity, indirectly enhancing fucoidan release. Such enzyme-assisted disruption of surrounding polysaccharide networks improves extractability and may promote the formation of lower-molecular-weight fucoidan fractions with enhanced solubility and bioactivity [20]. Table 2 presents the physicochemical characteristics of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) revealed distinct molecular weight distributions for each extract (see Table 2 and Figure S1). In all three extracts, two main peaks appeared. For Dur-I, a high-MW peak at ~201.4 kDa accounted for ~96.8% of the total area, while a low-MW peak at ~10.9 kDa corresponded to ~3.2%. Dur-II exhibited a high-MW peak at ~213.5 kDa (approximately 99.9%) and a minor low-MW peak at ~15.6 kDa (approximately 0.1%). In contrast, Dur-III showed a substantially different profile: the high-MW fraction centered at ~170.5 kDa accounted for approximately 46.7%, whereas the low-MW fraction at ~3.68 kDa represented about 54.3%. These results imply that the enzymes employed target different cleavage sites, and that the hydrolysis leading to Dur-III produces a greater proportion of oligosaccharides (approximately 3.7 kDa) compared to Dur-I and Dur-II. The pronounced shift to low-MW species in Dur-III is consistent with prior observations that enzymatic treatments can generate significant low-molecular-weight fractions in seaweed-derived polysaccharide extracts. For example, in polysaccharides from Laminaria japonica, two high-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC) peaks were reported after alginate lyase, cellulase, or combination of alginate lyase 102C300C and cellulase enzymatic hydrolysis [21]. These findings reinforce the notion that enzyme selection and processing protocol critically influence the molecular weight profile of seaweed extracts. In the present study, the prevalence of low-MW oligomers in Dur-III may have implications for bioactivity and downstream functionality, and it warrants further investigation.

Table 2.

Physicochemical analyses for Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III.

Table 2 also summarizes the chemical composition and monosaccharide profiles of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, including total sugar, fucose, sulfate, uronic acid, alginic acid, polyphenols, and protein contents. The measured total sugar contents were 43.8 ± 0.2% (Dur-I), 36.9 ± 0.4% (Dur-II), and 73.7 ± 0.3% (Dur-III). Fucose represented 14.6 ± 0.5%, 15.8 ± 0.5%, and 22.5 ± 0.5% of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, respectively. Overall, Dur-III contained markedly higher proportions of both total carbohydrate and fucose than Dur-I and Dur-II. These differences likely reflect the distinct hydrolytic specificities of the enzymes applied, which not only alter molecular-weight distributions but can also enrich or deplete particular monosaccharide fractions (for example, by generating oligosaccharides enriched in fucose). The compositional shifts observed here are consistent with previous reports showing that enzyme selection and depolymerization conditions strongly influence the monosaccharide composition of brown-algal polysaccharide preparations, with consequences for bioavailability and biological activity [22]. The sulfate contents measured in Dur-I, Dur-II and Dur-III were 38.1 ± 0.0%, 41.9 ± 0.0%, and 25.6 ± 0.0%, respectively. Uronic acid comprised 15.6 ± 0.2% (Dur-I), 15.6 ± 0.3% (Dur-II), and 18.2 ± 0.4% (Dur-III), while alginic acid accounted for 4.54 ± 0.15%, 4.59 ± 0.70%, and 6.78 ± 0.56%, respectively. The polyphenol contents were comparatively low (0.39 ± 0.02%, 0.33 ± 0.00%, and 0.36 ± 0.06%), and protein content remained below ~1.2% across all extracts (0.93 ± 0.03%, 1.13 ± 0.05%, and 1.03 ± 0.00% for Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, respectively). Overall, Dur-II exhibited the highest sulfate content, whereas Dur-III had the largest proportions of uronic acid and alginic acid. Table 2 also lists the monosaccharide profiles of Dur-I, Dur-II and Dur-III. Briefly, Dur-I was dominated by fucose, rhamnose, galacturonic acid and xylose, whereas Dur-II contained primarily fucose, rhamnose, glucose and xylose. Dur-III showed a mixture in which fucose, rhamnose, galacturonic acid, glucose and xylose were the major constituents. Collectively, these results indicate clear compositional differences among the three extracts. Such variation in monosaccharide composition and shift the relative abundance of chemical constituents (sulfate, uronic acids, alginate backbone), and together with the distinct molecular-weight distributions reported above, implies that Dur-I, Dur-II and Dur-III are likely to possess different physicochemical behaviors (e.g., solubility, viscosity, and chain conformation) and may therefore exhibit divergent biological activities. Recent studies have shown that enzyme choice and processing conditions strongly influence both MW distribution and monosaccharide/functional-group composition of algal polysaccharide preparations, with downstream effects on functional properties and bioactivity [23,24,25,26].

2.2. Elucidation of Structural Characterization of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III by FTIR and NMR Techniques

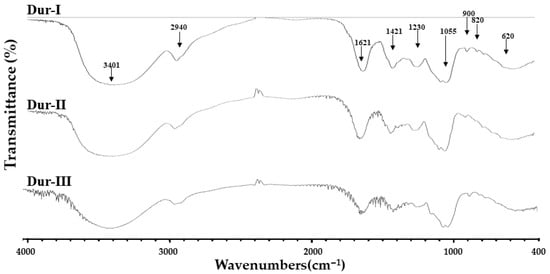

Structural characterization of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III was carried out using FTIR and NMR methods. As shown in Figure 1, all three extracts exhibited an absorption band at 3401 cm−1 and a band near 2940 cm−1, which correspond to O–H/H2O stretching and C–H stretching in pyranoid rings (or at C-6 positions of fucose/galactose residues), respectively, which features commonly observed in fucoidan-type polysaccharides [27,28,29]. In the fingerprint region (1800–600 cm−1), absorption peaks around 1621 and 1421 cm−1 were detected, likely reflecting H2O scissoring vibrations and in-plane ring C–H, C–O–H, and C–O–C deformations associated with polysaccharide backbones [27,28,30]. The bands at ~1230 and ~1055 cm−1 are consistent with asymmetric S=O stretching (sulfate ester) and C–O–C stretching of the glycosidic linkages [27,28,31]. The band at 900 cm−1 was associated with C1–H bending vibrations in β-anomeric units, likely originating from galactose [32]. Additionally, a peak near 820 cm−1, often attributed to C–O–S bending vibrations of sulfate substitutions, supports the presence of sulfated sugar residues in all extracts [33,34,35]. The band raised at 620 cm−1 may be attributed to symmetric O=S=O deformation [32]. Taken together, the FTIR data confirm that Dur-I, Dur-II and Dur-III share the general spectral features characteristic of sulfated, fucose-rich polysaccharides (e.g., “fucoidan-like” materials). However, the spectra of the three extracts are very similar, and no major differences in band positions or overall profile were evident, suggesting that despite differences in molecular weight distribution and monosaccharide composition, and the overall backbone chemistry and functional-group pattern remain broadly comparable. Such observations align with recent structural studies on brown-algal polysaccharides, which report that while variations in molecular weight or sulfate content may influence bioactivity, the core spectral fingerprint (OH, C–H, glycosidic link, sulfate) remains relatively conserved across differently processed extracts.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, highlighting absorption bands at 3401, 2940, 1621, 1421, 1230, 1055, 900, 820, and 620 cm−1.

Figure S2A shows the 1H NMR spectra of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. The signal at 4.13 ppm (4[H]) suggests the presence of 3-linked α-L-fucose [30]. Peaks at 4.07 and 3.95 ppm (6[H] and 6′[H]) indicate a (1-6)-β-D-linked galactan [36]. The signals at 3.78 ppm and 3.72 ppm may reflect 4-linked β-D-galactose (3[H]) and 2,3-linked α-β-mannose (4[H]), respectively [30]. The signals in the region 3.3–3.6 ppm likely correspond to ring protons (H-2 through H-5) of fucopyranose or other sugar residues (e.g., hexoses or uronic acids), including those adjacent to glycosidic linkages or sulfate/acetyl substituents [15]. Meanwhile, the weak resonances at ~2.71 and ~2.87 ppm may reflect minor components or modifications, such as residual acetyl groups, non-sugar impurities (e.g., amino acid residues) or protons on carbons adjacent to sulfate esters or uronic acid moieties [37]. The resonances observed at ca. 1.23–1.32 ppm can be attributed to the C-6 methyl protons (–CH3) of the 6-deoxy-sugar unit L-fucose, which is characteristic of fucoidan and confirmed in recent spectral studies [15,38]. Overall, the 1H-NMR profile supports the presence of a fucose-rich sulfated polysaccharide backbone across all three extracts, with subtle differences possibly attributable to variations in substitution patterns, composition (e.g., inclusion of uronic acids or hexose units), or processing history. In the 13C-NMR spectra of Dur-I, Dur-II and Dur-III (Figure S2B), the resonances were assigned as follows. Resonances in the 80–65 ppm region are characteristic of carbohydrate ring carbons (C-2 to C-5) of pyranose residues and typically include signals arising from sulfated or otherwise substituted ring carbons, which are shifted downfield relative to non-substituted carbons; therefore, peaks in this range are best interpreted as the ring C-2–C-5 carbons of fucopyranosyl, galactopyranosyl, or uronic-acid residues and likely include contributions from positions bearing sulfate esters [39,40]. The signal at 62.88 ppm is consistent with a C-6 (CH2OH) carbon of hexopyranose units (e.g., glucose, galactose) or with the C-6 of substituted galactose/galacturonic acid residues; such CH2 carbons typically appear near 60–63 ppm in polysaccharide spectra and serve as markers for the presence of hexose residues or hexose side-chains [41,42]. The resonance observed at 20.32 ppm in Dur-III is indicative of the methyl carbon of an acetyl group (–COCH3), suggesting the occurrence of O- or N-acetylation within the sample. Typically, acetyl methyl carbons in polysaccharides are detected in the 20–23 ppm region, and their presence is commonly reported in the coextraction of fucoidans or in partially acetylated fucoidans [39,42]. Finally, the resonance at 15.54 ppm corresponds well to the C-6 methyl carbon of L-fucose (–CH3); fucose C-6 methyl carbons are typically observed around 15–17 ppm and are diagnostic for fucose-rich sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidans). The presence of this signal therefore corroborates the high fucose content reported for Dur-I/II/III [40,41]. HSQC (heteronuclear single quantum coherence), a two-dimensional NMR spectrum, correlates proton chemical shifts (1H) with the chemical shifts in a directly bonded heteronucleus (commonly 13C). That means each cross-peak locates a specific H–C pair, which greatly helps assign which proton belongs to which carbon in a molecule [43]. Figure S2C depicts the HSQC spectra of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. Basically, two major clusters can be found (as shown in red rectangular). The HSQC spectra of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III reveal clear differences in the heteronuclear correlation patterns that reflect variations in their glycosidic linkages and sulfation profiles. All three extracts display dense clusters of cross-peaks within the typical carbohydrate region (δH 3.2–5.2 ppm/δC 60–105 ppm), consistent with the presence of fucose, rhamnose, and galactose-derived residues. However, Dur-III exhibits a more dispersed set of correlations, particularly between δH 4.5–5.1 ppm and δC 95–103 ppm, indicating a higher proportion of anomeric protons and suggesting a more heterogeneous mixture of oligosaccharide fragments, which is consistent with its lower molecular weight fraction. Dur-I and Dur-II show more compact anomeric clusters, implying a higher degree of structural uniformity. In addition, Dur-III presents stronger correlations in the δC 65–75 ppm region paired with δH 3.4–4.2 ppm, which are characteristic of C2/C4-sulfated fucose residues, whereas Dur-II displays slightly intensified correlations near δC ~80 ppm, possibly reflecting substituted C3 positions. The subtle variations in cross-peak distribution therefore suggest that enzyme-specific hydrolysis generated distinct linkage patterns and sulfation motifs across the three extracts, supporting the hypothesis that Dur-III contains more extensively cleaved oligosaccharides compared with Dur-I and Dur-II. Collectively, both Dur-I and Dur-II show comparatively compact anomeric clusters and fewer dispersed cross-peaks, consistent with higher-molecular-weight fractions dominated by repeating fucose-rich sequences and fewer distinct oligomeric end-groups. Dur-II, which had the highest measured sulfate content, shows subtle intensification of correlations near δC ~80 ppm, a region frequently associated with sulfation at C-3 (or stereoelectronic effects from adjacent substitutions). This pattern suggests enzyme-dependent preferences for cleavage sites and positions of sulfate retention or enrichment. In addition, Dur-III displays a broader and more dispersed distribution of anomeric correlations (δH ~4.5–5.1 ppm/δC ~95–103 ppm) and more intense cross-peaks in the δC 65–75 ppm/δH 3.4–4.2 ppm region. These observations may show the information of increased heterogeneity of anomeric linkages (more distinct anomeric environments) and a higher occurrence of sulfation at positions that shift ring carbons into the 65–75 ppm window (for example, 2-O or 4-O sulfation on fucose). From an enzyme reaction and structural perspective, the α-amylase treatment used to generate Dur-III appears to promote the formation of more extensively cleaved and sulfate-rich fucose oligosaccharides. α-Amylase is an endo-acting glycoside hydrolase that randomly hydrolyzes internal α-1,4-glycosidic linkages, producing oligosaccharides of heterogeneous length rather than site-specific products. Although fucoidan is not a direct substrate of α-amylase, the complex polysaccharide matrix of brown seaweed contains α-linked glucans and storage polysaccharides interwoven with fucoidan, alginate, and cellulose. Random cleavage of these non-target components reduces matrix integrity, increases the number of accessible chain ends, and facilitates solubilization of fucoidan fragments [44]. Consistent with this mechanism, HSQC spectra of Dur-III show more dispersed anomeric correlations and intensified signals in regions associated with C2- and C4-sulfated fucose residues, indicating greater structural heterogeneity and enriched sulfation motifs. In contrast, extracts produced using viscozyme or cellulase display more compact anomeric clusters, suggesting preservation of relatively uniform, higher-molecular-weight sequences. Collectively, these findings suggest that the non-specific, endo-acting behavior of α-amylase in a heterogeneous biomass context favors the release of diverse, sulfate-rich fucoidan oligosaccharides, which may contribute to the enhanced biological activity observed for Dur-III [45]. Given the inherent structural heterogeneity and conformational complexity of polysaccharides, additional complementary analytical techniques are often required to achieve unambiguous structural elucidation. In summary, these spectroscopic signatures reconcile with the following compositional information: Dur-III’s high total sugar and fucose percentages and elevated proportion of low-MW species (SEC) are reflected in its dispersed HSQC pattern and stronger low-MW-related correlations, whereas Dur-I and Dur-II preserve larger, more uniform polymeric regions. The higher sulfate content in Dur-II corresponds to HSQC shifts consistent with substitution at specific ring carbons. Such correlations between SEC, compositional analysis, FTIR and 2D NMR are well described in recent studies, which emphasize that molecular-weight, sulfation degree and substitution position jointly determine NMR chemical-shift patterns and biofunctional potential [39,46]. Dur-III exhibited intensified HSQC cross-peaks characteristic of C2- and C4-sulfated fucose residues, indicating enriched site-specific sulfation. Such sulfation patterns are critical for bioactivity, as sulfate groups enhance electrostatic interactions with proteins and signaling molecules involved in oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways. The structural diversity of sulfated oligosaccharides in Dur-III may therefore promote multiple molecular interactions, contributing to its enhanced cytoprotective effects [47].

2.3. Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III Attenuated Rotenone-Induced Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Neuronal Cells

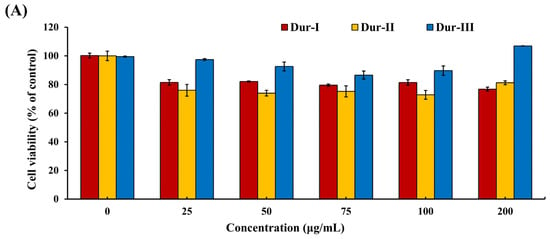

Protective effects of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III against rotenone-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III attenuated rotenone-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y neuronal cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells retain an immature, neuroblast-like phenotype and exhibit low or inconsistent expression of dopaminergic markers, thereby limiting their utility for directly modeling dopaminergic neuronal pathology without prior differentiation. Although differentiation protocols, typically involving retinoic acid, alone or in combination with neurotrophic factors, can enhance dopaminergic features such as tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine transporter expression, these procedures are often time-consuming and experimentally complex. Nevertheless, SH-SY5Y cells remain a widely utilized and cost-effective in vitro model for studies of neurotoxicity and neuroprotection [48,49]. Accordingly, the present study employed undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells to evaluate the cytoprotective activities of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III against rotenone-induced apoptosis within an established rotenone neurotoxicity paradigm. Accumulating evidence indicates that neuronal apoptosis is a key pathological event following metabolic stress or neurotoxic injury and contributes substantially to the progression of both acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders in the adult brain [50]. In neuroprotective studies using SH-SY5Y cells, it is standard practice to first determine a non-toxic concentration range of test compounds before evaluating their protective effects against cellular stressors. Polysaccharide extracts such as Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III are complex high-molecular-weight biopolymers that are generally well tolerated by cells at moderate concentrations, but may exert cytotoxic effects at higher doses. Accordingly, a concentration range of 0–200 μg/mL was selected based on prior studies showing that similar extracts (e.g., fucoidan and related marine polysaccharides) are non-cytotoxic within this range and can be meaningfully evaluated for dose-dependent effects on cell viability and protective activity without inducing inherent toxicity themselves [51,52]. In this study, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay to determine the cytotoxic profiles of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III in SH-SY5Y cells across a concentration range of 0–200 μg/mL, as well as the cytotoxic effect of 50 μM rotenone (Rot). In addition, the protective potential of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III against Rot-induced cytotoxicity was evaluated by examining their ability to restore cell viability following Rot exposure. Given that the MTT assay primarily provides an initial assessment of cell viability, it was utilized in this study to guide the selection of appropriate treatment concentrations for downstream analyses. Subsequently, flow cytometric analysis was conducted to systematically compare the neuroprotective mechanisms of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. As shown in Figure 2A, none of the polysaccharide fractions within the concentration range of 0–200 μg/mL reduced cell viability below approximately 80%, indicating minimal cytotoxic effects. In agreement with previous reports, exposure to 50 μM rotenone (Rot) resulted in approximately 50% cell death (Figure 2B) [53]. As further illustrated in Figure 2B, pretreatment with Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III (25–200 μg/mL for 24 h) significantly attenuated Rot-induced cytotoxicity. The maximal protective effects were observed at concentrations of approximately 100–200 μg/mL for Dur-I, 50 μg/mL for Dur-II, and 200 μg/mL for Dur-III. To enable a consistent and effective comparison of the neuroprotective effects among Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, a concentration of 200 μg/mL was therefore selected for all three extracts in subsequent flow cytometric analyses.

Figure 2.

(A) SH-SY5Y cells treated with different concentrations of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III (0, 25, 50, 75, 100, and 200 μg/mL) for 48 h; (B) SH-SY5Y cells treated with different concentrations of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III (0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) for 24 h prior to the addition of Rot (rotenone) 50 μM to the culture medium for 24 h, and the cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Bars labeled with different letters differ significantly at p < 0.05.

To further and comparatively elucidate the protective effects of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III against rotenone (Rot)-induced neuronal apoptosis, a series of mechanistic analyses were conducted using flow cytometry. These analyses encompassed the measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), examination of Bcl-2 protein regulation, evaluation of cytochrome c release, determination of caspase-9, -8, and -3 activation, and quantification of DNA fragmentation, as the results were presented in Table 3 and Figure S3. Accumulating evidence indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and impairment of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium (mitoK ATP) channels, plays a pivotal role in the initiation of programmed cell death [54]. Irreversible mPTP opening disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis, leading to ATP depletion and the onset of apoptosis [55]. Because maintenance of MMP is essential for ATP synthesis and overall cellular homeostasis [56], the loss of MMP represents a hallmark of early apoptosis and is closely associated with downstream caspase activation [57]. MMP was assessed using the tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) assay. TMRE is a cationic, lipophilic dye that accumulates within polarized mitochondria in proportion to membrane potential. Depolarization reduces TMRE accumulation and consequently decreases fluorescence intensity, making TMRE a reliable indicator of mitochondrial integrity and function [58]. As TMRE enters the cell, it interacts with fluorescent proteins and other intracellular components, leading to the emission of fluorescence. When the membrane potential decreases, TMRE accumulates within the cell, resulting in an increased fluorescence signal. In contrast, a rise in membrane potential causes TMRE to be expelled, leading to weaker fluorescence [52]. Therefore, measuring TMRE accumulation in mitochondria provides an effective indicator of mitochondrial function. In the present study, exposure of SH-SY5Y cells to 50 µM Rot markedly increased the proportion of low-TMRE cells (Table 3), reflecting substantial MMP loss. This shift corresponded to a reduction in the fraction of high-TMRE cells, consistent with mitochondrial depolarization. Importantly, pretreatment with Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III (200 µg/mL, 24 h) significantly mitigated the Rot-induced decline in TMRE fluorescence, indicating preservation of MMP. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the Dur I/II/III effectively protect SH-SY5Y cells from Rot-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby attenuating early apoptotic signaling. Bcl-2 is a key anti-apoptotic member of the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) protein family and plays an essential role in preserving mitochondrial integrity. Previous studies have shown that Bcl-2 prevents mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) depolarization and delays the activation of downstream apoptotic effectors, including the release of cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and Smac/Diablo [59]. Conversely, downregulation of Bcl-2 facilitates the progression of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. As summarized in Table 3, exposure of SH-SY5Y cells to 50 µM Rot for 24 h markedly decreased Bcl-2 expression (65.2% ± 0.7%) compared with untreated controls (87.7% ± 0.6%). However, pretreatment with 200 µg/mL of Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III significantly restored Bcl-2 levels to 69.3% ± 0.3% (p = 0.0074), 73.5% ± 0.4% (p = 0.00062), and 71.4% ± 0.4% (p = 0.00166), respectively, as compared to the Rot group, indicating that the Dur I/II/III mitigated Rot-induced suppression of this anti-apoptotic protein. Among the three samples, Dur-II exhibited the strongest protective effect on Bcl-2 expression, followed by Dur-III and Dur-I. This enhanced neuroprotective effect of Dur-II is likely attributable to its distinct chemical composition, particularly its higher sulfate content and balanced monosaccharide profile, compared with Dur-I and Dur-III. Higher sulfate densities can increase interaction with cellular proteins and signaling cascades relevant to redox homeostasis and apoptosis regulation [16]. Fucoidan structure-activity studies indicate that relative amounts of fucose, rhamnose, uronic acids, etc., can influence bioactivity by affecting molecular conformation, solubility, and carrier interactions with cell surface receptors or intracellular targets [60]. Dur-II’s composition includes substantial proportions of fucose and other sugars (e.g., rhamnose, glucose, xylose), which may help optimize structural flexibility and facilitate interactions with neuronal protective pathways more effectively than either Dur-I or the hyper-carbohydrate-rich Dur-III. Previous studies have shown that the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) induces matrix condensation and exposes cytochrome c to the intermembrane space, thereby facilitating its release into the cytosol and initiating apoptotic signaling cascades [61]. In the present study, the effect of Rot on cytochrome c release in SH-SY5Y cells was evaluated. Exposure to 50 µM Rot for 24 h markedly reduced the proportion of high-fluorescence cells from 55.6% ± 1.2% (control) to 19.2% ± 0.5%, indicating substantial mitochondrial cytochrome c release (Table 3). In contrast, pretreatment with Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III significantly increased the proportion of high-fluorescence cells to 39.3% ± 2.2% (p = 0.0044), 50.2% ± 0.9% (p = 3.7 × 10−5), and 35.9% ± 2.0% (p = 0.0049), respectively, as compared to the Rot group, demonstrating attenuation of Rot-induced cytochrome c release. Among the three extracts, Dur-II exerted the strongest protective effect, followed by Dur-I and Dur-III. Sulfated polysaccharides are well known to preserve mitochondrial integrity under oxidative stress, with bioactivity closely linked to the degree of sulfation. Higher sulfate content generally enhances radical scavenging, limits mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, and suppresses cytochrome c release. Among the extracts, Dur-II exhibited the highest sulfate content, which may underlie its superior ability to attenuate ROS-induced mitochondrial damage [62]. In addition, its balanced monosaccharide composition may favor optimal solubility, chain conformation, and interactions with cellular membranes and mitochondrial targets. Emerging evidence suggests that synergism between sulfation level and sugar diversity, rather than fucose content alone, is critical for cytoprotective efficacy [62]. Consistent with the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, the release of cytochrome c enables apoptosome formation, which subsequently activates downstream caspases that execute apoptosis [63]. The present study also evaluated the effects of Dur I/II/III on the activation status of caspase-9, caspase-8, and caspase-3 in SH-SY5Y cells. As shown in Table 3, exposure to 50 µM Rot for 24 h markedly increased the levels of active caspase-9, -8, and -3 compared with untreated control cells, indicating robust activation of the apoptotic pathways. In contrast, pretreatment with 200 µg/mL of Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III significantly reduced Rot-induced caspase activation, demonstrating that the Dur I/II/III effectively suppressed the initiation and execution phases of apoptosis. Caspase-3, a principal executioner caspase activated by both the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death-receptor) pathways, cleaves nuclear and cytosolic substrates (e.g., ICAD/DFF45), thereby enabling CAD-mediated DNA fragmentation and producing the characteristic internucleosomal ‘ladder’ of late apoptosis [64]. To further assess apoptosis progression, DNA fragmentation was quantified using a TUNEL assay. As shown in Table 3, the proportion of high-fluorescence (TUNEL-positive) cells significantly increased from 43.0% ± 0.4% (control) to 69.2% ± 0.6% following 24 h exposure to 50 µM Rot, confirming substantial DNA fragmentation. Pretreatment with Dur extracts attenuated this effect, reducing the TUNEL-positive population to 59.2% ± 3.1% (p = 0.0419), 63.0% ± 0.6% (p = 0.0005), and 48.6% ± 0.9% (p = 3.3 × 10−5) for Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, respectively, as compared to the Rot group. Among the three extracts, Dur-III conferred the strongest protection, followed by Dur-II and Dur-I. Dur-III contains the highest total carbohydrate (73.7% ± 0.3%) and fucose percentage (22.5% ± 0.5%) among the three extracts. Polysaccharides rich in fucose and diverse sugar units are often associated with strong antioxidant capabilities and ROS-scavenging functions, which can diminish oxidative damage to nuclear DNA under stress conditions like Rot exposure. Fucoidans and other heteropolysaccharides with diverse sugar profiles have been shown to protect cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and DNA damage by reducing ROS and stabilizing cellular membranes [26]. Dur-III also possesses the largest proportions of uronic acid (18.2% ± 0.4%) and alginic acid (6.78% ± 0.56%). Uronic and alginic acid residues can provide additional antioxidant capacity and metal-chelating properties, which may further reduce formation of ROS and protect DNA integrity. Uronic acid-rich polysaccharides are often more effective in forming protective physical barriers and maintaining cellular homeostasis under stress. Such properties can slow apoptotic progression and limit DNA fragmentation [26]. Combined with a broad monosaccharide distribution (fucose, rhamnose, galacturonic acid, glucose, xylose), Dur-III’s polysaccharide mixture likely supports favorable chain conformations and solubility characteristics that enhance cell-surface interactions and intracellular signaling modulation. These structural features have been linked to robust modulation of apoptosis signaling pathways, where reduced oxidative stress and modulation of cell survival signaling may slow caspase activation and limit DNA fragmentation that commonly follows caspase-3-mediated cleavage of nuclear substrates [26]. In addition, the structural features indicated more extensively cleaved, sulfate-rich oligosaccharides in Dur-III that may also contribute to distinct biological activities (e.g., higher solubility, altered molecular interactions). Studies on low-molecular-weight fucoidans reveal that oligosaccharide generation and sulfate distribution strongly influence bioactivity, including antioxidant and neuroprotective effects [65]. In contrast to Bcl-2 and cytochrome c endpoints, protection against DNA fragmentation involves later stages of apoptosis that depend on a combination of upstream antioxidant defenses and structural stabilization of intracellular compartments. Dur-III’s unique compositional profile and structural aspect appear to be particularly effective at suppressing oxidative damage and caspase-mediated DNA fragmentation, even if it is slightly less efficient at preventing early mitochondrial events than Dur-II. Thus, while Dur-II’s high sulfate content supports earlier apoptotic checkpoint protection (mitochondrial integrity/Bcl-2 and cytochrome c), Dur-III’s distinct more extensively cleaved, sulfate-rich oligosaccharides, mix of high total carbohydrates, fucose, uronic and alginic acids better targets the later and critical apoptotic processes (like DNA fragmentation) by maintaining genome integrity under sustained oxidative stress. Collectively, these findings indicate that Dur I/II/III mitigate Rot-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells by suppressing caspase activation and preventing downstream DNA fragmentation.

Table 3.

Expressions of mitochondria-dependent apoptotic factors in Rot-, Dur-I-, Dur-II-, and Dur-III-treated SH-SY5Y cells.

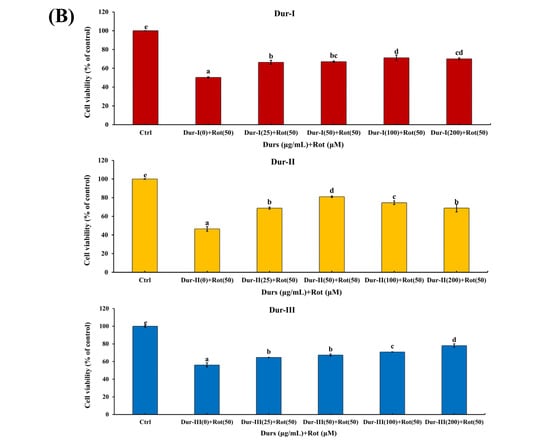

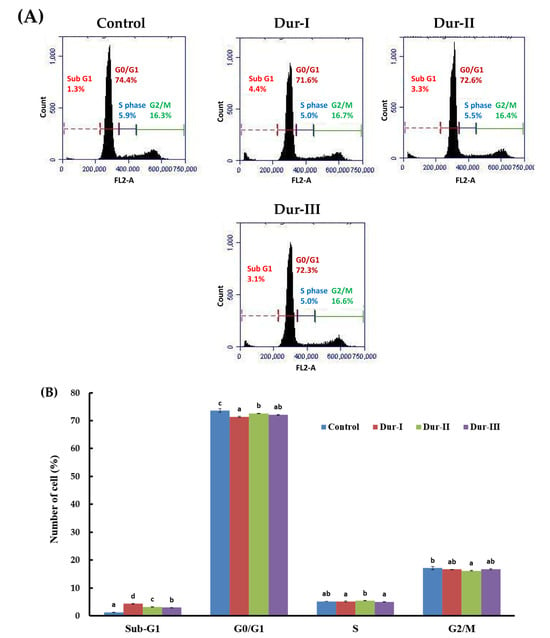

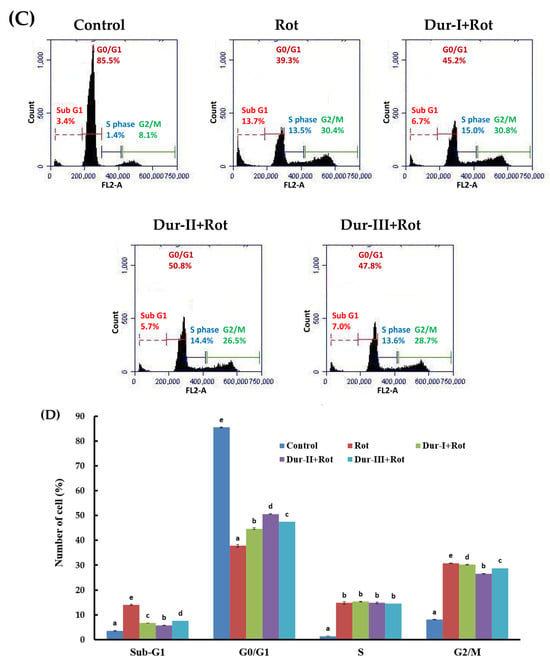

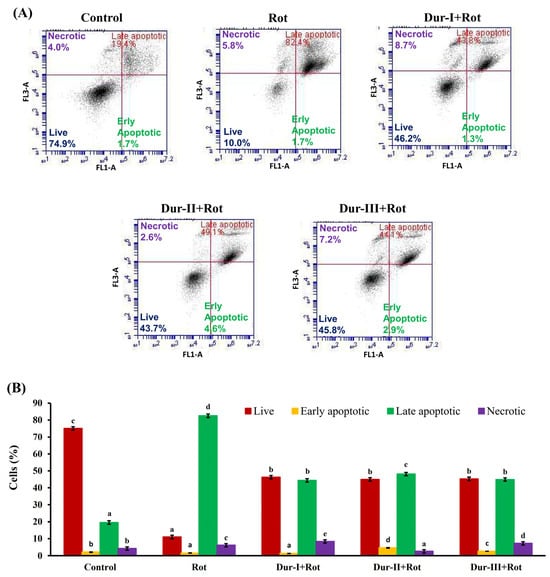

During propidium iodide (PI) staining, flow cytometric analysis enables the identification of apoptotic cells and cells exhibiting nuclear fragmentation, which are typically characterized as a sub-G1 population [66]. To further examine the baseline regulatory effects of Dur-I/II/III on cell death under physiological conditions, we assessed the cell-cycle distribution in cells treated with Dur I/II/III alone, without Rot exposure. As shown in Figure 3A,B, treatment with Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III at 200 µg/mL for 48 h resulted in a slight increase in the proportion of sub-G1 cells compared with the untreated control, whereas the distributions of other phases (G0/G1, S, and G2/M) remained largely unchanged. These findings indicate that Dur I/II/III exhibit minimal cytotoxicity toward SH-SY5Y cells and help maintain cellular survival signaling under basal conditions. As shown in Figure 3C,D, analysis of DNA content revealed that treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with 50 µM Rot induced a significant increase in the proportion of cells with sub-G1 DNA content (14.0% ± 0.22%) compared with untreated cells (3.53% ± 0.13%). Pretreatment with 200 µg/mL Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III and then treatment with 50 µM Rot significantly reduced the apoptotic sub-G1 populations to 6.70% ± 0.00% (p = 0.0004), 5.80% ± 0.08% (p = 6.7 × 10−5), and 7.50% ± 0.08% (p = 0.0001), respectively, as compared to the Rot group. Overall, Dur-II exhibited the strongest protective effect, followed by Dur-III and Dur-I. These findings indicate that Rot exposure markedly increases the percentage of sub-G1 cells, reflecting enhanced DNA fragmentation and apoptosis. Moreover, Dur-I/II/III pretreatment significantly attenuated the Rot-induced sub-G1 accumulation, suggesting that Dur-I/II/III confer protective effects against neuronal damage in SH-SY5Y cells. In comparison with a previously published study in which fucoidans were extracted from brown seaweed Sargassum hemiphyllum using hot-water extraction at 85 °C (yielding extract SH1), treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with 75 µM 6-OHDA resulted in a marked increase in the sub-G1 population (36.45% ± 0.88%) relative to control cells (0.49% ± 0.07%). Co-treatment with SH1 at 500 µg/mL significantly reduced the sub-G1 fraction to 5.25% ± 0.05%, indicating a protective effect against 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity [52]. Notably, the effective concentration of SH1 was approximately 2.5-fold higher than that required for Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III in the present study. This comparison suggests that enzyme-assisted extraction may yield fucoidan-rich extracts with enhanced neuroprotective potency compared with conventional hot-water extraction approaches. Moreover, treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with 50 µM Rot resulted in a pronounced arrest or delay in entry into the G2/M phase, increasing the G2/M population to 30.8% ± 0.05% compared with untreated cells (8.07% ± 0.05%) (Figure 3D). Pretreatment with 200 µg/mL Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III and then treatment with 50 µM Rot attenuated this G2/M accumulation, reducing the G2/M populations to 30.2% ± 0.17% (p = 0.0391), 26.6% ± 0.09% (p = 1.6 × 10−5), and 28.8% ± 0.29% (p = 0.0096), respectively, as compared to the Rot group. These results suggest that Dur-I/II/III mitigate Rot-induced cell-cycle arrest and growth inhibition in SH-SY5Y cells. Overall, Dur-II exhibited the strongest rescue effect, followed by Dur-III and Dur-I. An additional apoptosis assessment was performed using Annexin V-FITC and PI double staining. Early apoptosis is marked by the disruption of plasma membrane asymmetry, leading to the translocation of phosphatidylserine (PS) residues from the inner to the outer leaflet of the membrane [67]. Annexin V binds strongly and specifically to exposed PS, making Annexin V staining a dependable method for detecting early apoptotic events. In contrast, PI enters only non-viable cells, allowing clear distinction among viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations. Viable cells exhibit no staining with either Annexin V-FITC or propidium iodide (PI); early apoptotic cells are Annexin V-FITC-positive and PI-negative; late apoptotic cells are positive for both Annexin V-FITC and PI; whereas necrotic cells are Annexin V-FITC-negative and PI-positive. [66]. As shown in Figure 4, exposure of SH-SY5Y cells to 50 µM Rot for 24 h markedly increased the proportion of late apoptotic cells to 82.5% ± 0.5%, accompanied by a substantial reduction in viable cells to 11.0% ± 0.2%, compared with the control group (19.5% ± 0.3% and 75.1% ± 0.6%, respectively). Pretreatment with 200 µg/mL Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III and then treatment with 50 µM Rot significantly reduced late apoptotic populations to 44.4% ± 0.2% (p = 3.1 × 10−6), 48.1% ± 0.7% (p = 3.3 × 10−6), and 44.9% ± 0.7% (p = 1.2 × 10−6), respectively, as compared to the Rot group. Overall, Dur-III exhibited the strongest rescue effect, followed by Dur-I and Dur-II. Correspondingly, the proportion of viable cells increased to 46.2% ± 0.5% (p = 6.8 × 10−6), 45.0% ± 0.9% (p = 0.0002), and 45.3% ± 0.5% (p = 2.0 × 10−5) in the Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III groups, respectively, as compared to the Rot group. These findings clearly demonstrate that Dur I/II/III provide substantial protection against Rot-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells, particularly by reducing late apoptotic cell death.

Figure 3.

Effects of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III, as well as rotenone (Rot) with or without pretreatment using these hydrolysates, on the cell cycle distribution of SH-SY5Y cells. (A) SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III (200 μg/mL) for 48 h, followed by cell cycle analysis. (B) The bar chart summarizes data from three independent flow cytometry assays, presenting the percentages of cells in the sub-G1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases for each treatment, analyzed using BD Accuri C6 software version 1.0. (C) SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III (200 μg/mL) for 24 h and then treated with Rot (50 μM) for an additional 24 h before cell cycle evaluation. (D) The corresponding bar chart presents results from three independent experiments, showing phase distribution under each condition, analyzed with BD Accuri C6 software. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). For each cell cycle phase, bars marked with the same letter do not differ significantly (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of Rot treatment, with or without Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III pretreatment, on annexin V-FITC/PI-labeled SH-SY5Y cells. (A) SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with Dur-I, Dur-II, or Dur-III (200 μg/mL) for 24 h, followed by exposure to Rot (50 μM) for an additional 24 h. Annexin V-FITC/PI fluorescence patterns were then evaluated. (B) The accompanying bar graph shows the proportions of viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells, based on three independent flow cytometry experiments analyzed using BD Accuri C6 software version 1.0. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Bars labeled with different letters differ significantly at p < 0.05.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

A specimen of D. antarctica was obtained from a local grocery market in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan. The sample was oven-dried and stored in sealed plastic containers at 4 °C prior to further use. Analytical standards, including L-fucose, L-rhamnose, D-glucuronic acid, D-galacturonic acid, D-glucose, D-galactose, and D-xylose, as well as chemical reagents such as sodium carbonate, rotenone, potassium sulfate, potassium bromide (KBr), potassium persulfate, sodium sulfite, dextrans (1, 12, 50, 150, and 670 kDa), trypsin/EDTA, MTT, Bradford reagent, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Enzymes, including viscozyme, cellulase, and α-amylase, were also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Cell culture reagents, namely RPMI-1640 medium, fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin, were supplied by Gibco Laboratories (Grand Island, NY, USA). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was procured from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). Fluorescent probes, including tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) and FITC-conjugated anti-Bcl-2 antibodies, were obtained from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other biochemical and immunological reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified.

3.2. Extrusion Method

Extrusion processing was carried out using a laboratory-scale single-screw extruder (Tsung Hsing Co., Ltd., Kaohsiung, Taiwan) with a screw diameter of 74 mm and a length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio of 3.07:1, fitted with a rounded die of 5 mm diameter. Prior to extrusion, the raw D. antarctica material was conditioned to a moisture content of 35%. Based on our previously established methodology [13], extrusion was performed under optimized conditions to ensure stable and reproducible operation. Therefore, the extrusion parameters were set as follows: a feed rate of 10.4 kg h−1, a barrel temperature of 115 °C, and a screw rotation speed of 360 rpm. Upon completion of extrusion, the processed material was dried at 55 °C for 30 min, allowed to cool to ambient temperature, and subsequently milled into powder. The resulting product was sealed in aluminum bags and stored at 4 °C until further use in enzymatic extraction experiments.

3.3. Seaweed Extraction by Enzymes

The enzymatic extraction was performed following previously described procedures [6,68] with slight modifications. In brief, 1 g of dried D. antarctica was suspended in 100 mL of double-distilled water (ddH2O) adjusted to pH 6.0. Enzymatic hydrolysis was initiated by the addition of either viscozyme (100 μL, ≥100 FBGU g−1), cellulase (100 mg, approximately 0.8 U mg−1 solid), or α-amylase (100 mg, ≥5 U mg−1 solid). The dosages of viscozyme, cellulase, and α-amylase were determined by integrating reported effective ranges for algal polysaccharide hydrolysis [68,69], manufacturer-recommended depolymerization levels, and practical enzyme loadings under standardized reaction conditions. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 40 °C for 17 h under continuous agitation at 250 rpm. After this period, the enzymatic reaction was terminated by boiling the suspension at 85 °C for 10 min and thereafter immediate cooling in an ice bath. Following hydrolysis, the suspensions were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm PVDF membranes to remove residual insoluble material. The resulting filtrates were frozen at −80 °C, lyophilized, and the obtained powders were stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Hydrolysis efficiency and the extent of depolymerization were indirectly assessed using complementary analytical parameters, including extraction yield, monosaccharide composition, sulfate content, and molecular weight distribution. Extraction yield was calculated according to the following equation:

where gA is the dry weight of the recovered extract and gB is the dry weight of the original sample.

Extraction yield (%) = (gA/gB) × 100

3.4. Molecular Weight Analysis

The molecular weight distribution of the polysaccharides was assessed following the procedure described by Yang [66]. Column calibration was performed using a series of dextran standards with molecular weights of 1, 12, 50, 150, and 670 kDa.

3.5. Chemical Methods

Total sugar content was determined using the phenol-sulfuric acid colorimetric method, with galactose employed as the calibration standard. Fucose concentration was quantified according to a previously reported procedure [6], using L-fucose for standard curve generation. Uronic acid content was measured by a colorimetric assay using D-galacturonic acid as the reference compound [6]. Alginate levels were evaluated following an established analytical protocol [6]. Total polyphenols were quantified using the Folin–Ciocalteu assay, with gallic acid as the standard. Sulfate content was assessed by acid hydrolysis of the samples in 1 N HCl at 105 °C for 5 h, followed by determination of sulfate ions using an ion chromatography system (Dionex ICS-1500, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an IonPac AS9-HC analytical column (4 × 250 mm). The chromatographic analysis was performed at 30 °C with a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1, employing 9 mM Na2CO3 as the eluent, and potassium sulfate (K2SO4) as the external standard. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the reference standard.

3.6. Analysis of Monosaccharide Composition

The monosaccharide composition was measured using aforementioned protocol [6], using fucose, rhamnose, glucuronic acid, galacturonic acid, glucose, galactose, and xylose as the standards.

3.7. FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR analysis was carried out following the procedure described by Shih [6]. Briefly, the sample was blended with KBr at a 1:50 ratio (w/w) and ground thoroughly until the particle size was below 2.5 μm. Transparent KBr pellets were then produced by pressing the mixture at 500 kg/cm2 under vacuum. Spectra were recorded using an FT-730 spectrometer (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) over the range of 400 to 4000 cm−1. A KBr pellet without sample served as the background control.

3.8. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

The extracts were initially dissolved in 99.9% deuterium oxide (D2O) directly within NMR tubes for subsequent analysis. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were acquired using a Varian VNMRS-700 spectrometer (Varian, Lexington, KY, USA) to investigate the structural characteristics of polysaccharides. The proton chemical shift was expressed in ppm.

3.9. Cell Culture

The human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (ATCC® CRL-2266™) was obtained from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U mL−1), and streptomycin (100 µg mL−1). The cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The culture medium was replaced every 48–72 h.

3.10. Cell Viability Analysis

Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT colorimetric assay. Briefly, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells mL−1 and allowed to reach approximately 80% confluence. The cells were then treated with extracts at various concentrations for the indicated time periods. After treatment, MTT solution (final concentration, 0.1 mg mL−1) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h to allow the formation of formazan crystals. Subsequently, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to solubilize the formazan and lyse the cells. Cell viability was calculated as a percentage relative to the untreated control according to Equation (2).

AT is the absorbance at 570 nm in the test, and AC is the absorbance at 570 nm for the control.

3.11. Flow Cytometry-Based Analyses

The SH-SY5Y cells with a cell density 4 × 104 cells/mL were cultured without (cells were in serum-free medium, as a control) and with 200 μg/mL Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III (cells were in serum-free medium) for 24 h, and then the cells were added with Rot (50 μM) for 24 h, and thereafter the cells were collected for flow cytometer-based analysis as the described protocols: (1) For the MMP analysis, the cells were labeled with tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) (100 nM). (2) For the Bcl-2 expression analysis, the cells were labeled with FITC-anti-Bcl-2 antibody (1:25, v/v). (3) A 1:10 (v/v) FITC-anti-cytochrome c antibody was applied to label the cell preparations for the cytochrome c release experiment. (4) The cells were labeled with FITC-LEHD-FMK solution for caspase-9 detection, FITC-IETD-FMK solution for caspase-8 detection, and FITC-DEVD-FMK solution for caspase-3 detection, respectively. (5) For the DNA fragmentation assay, apoptotic cells were labeled with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and subsequently incubated with a FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. (6) For cell-cycle analysis, cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI; 50 µg/mL) and RNase A (25 µg/mL) at 37 °C for 15 min. (7) For the Annexin V–FITC/PI assay, cells were double-stained with Annexin V-FITC (1:20, v/v) and PI (1:20, v/v). Following staining, flow-cytometric analyses were performed using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (San Jose, CA, USA), with a minimum of 10,000 events acquired per sample. Data acquisition and analysis were conducted using BD Accuri C6 software.

3.12. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 12.0. Differences among groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple range test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For comparisons between two groups, statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, and the corresponding p values were reported.

4. Conclusions

In this study, three Durvillaea antarctica extracts (Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III) were produced from extrusion-pretreated biomass using different enzymatic strategies, resulting in distinct compositional, molecular weight, and structural characteristics. Extrusion pretreatment improved enzymatic accessibility and extraction efficiency. All extracts significantly protected SH-SY5Y cells against rotenone-induced apoptotic injury, with Dur-III, obtained using the non-specific enzyme α-amylase, showing the most pronounced neuroprotective effect. This enhanced activity is likely associated with its higher carbohydrate, fucose, uronic acid, and alginic acid contents and enrichment in extensively cleaved, sulfate-rich fucose oligosaccharides. Despite the limitations of undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells as a neuronal model, these findings demonstrate robust cytoprotective effects of the Dur extracts under oxidative stress. Future investigations warrant to employ differentiated SH-SY5Y cells and/or relevant in vivo models. Overall, the results highlight the potential of these enzyme-derived extracts as promising candidates for the development of neuroprotective agents targeting oxidative stress-related neurological disorders.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16020113/s1. Figure S1: Size exclusion chromatographic profiles for Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. Dextrans with molecular weights 1, 12, 50, 150, and 670 kDa were utilized as the standards; Figure S2: NMR spectra for Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III. (A) 1H spectra. (B) 13C spectra. (C) HSQC spectra. The characteristic peaks are labeled; Figure S3: Effects of Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III treatment and Rot treatment with or without Dur-I, Dur-II, and Dur-III (200 μg/mL) pretreatment on the apoptotic factors of SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Low mitochondrial membrane potential; (B) Level of Bcl-2; (C) Release of cytochrome c; (D) Caspase-9 activity; (E) Caspase-8 activity; (F) Caspase-3 activity; (G) DNA fragmentation.

Author Contributions

W.-C.H.: Conceptualization. T.-C.W.: Data curation and Writing—Original draft preparation. Y.-H.H.: Visualization and Investigation. M.-C.L.: Formal analysis and Methodology. Y.-W.C.: Software, Investigation, and Validation. C.K.: Software and Writing—Original draft preparation. C.-Y.H.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, and Writing—Reviewing and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yuan’s General Hospital, Taiwan, grant number YUAN-IACR-25-01 to Wei-Cheng Hsiao. This work was supported by grants from the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH112-M201) to Tien-Chiu Wu. This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan [grant number NSTC 113-2221-E-992-008], [grant number NSTC 114-2918-I-992-003], and [grant number NSTC 114-2221-E-992-020-MY3], which were awarded to Chun-Yung Huang. This research was also supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Taiwan, under grant number 114AS-1.6.2-AS-24, which was awarded to Chun-Yung Huang.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SEC | Size-exclusion chromatography |

| HPSEC | High-performance size exclusion chromatography |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear single quantum coherence |

| Rot | Rotenone |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| mitoK ATP | Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium |

| TMRE | Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma-2 |

| AIF | Apoptosis-inducing factor |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| KBr | Potassium bromide |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

References

- Zhou, Q.L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W.T.; Liu, X.F.; Cheong, K.L.; Zou, Y.X.; Zhong, S.Y.; Li, R. The structural characteristics, biological activities and mechanisms of bioactive brown seaweed polysaccharides: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, K.; Tatsumi, D.; Sugiyama, T.; Hiraoka, M.; Igura, N.; Tsubaki, S. Accelerating sulfated polysaccharides extraction from fast-growing Ulva green seaweed by frequency-controlled microwaves. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29896–29903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfinaikh, R.S.; Alamry, K.A.; Hussein, M.A. Sustainable and biocompatible hybrid materials-based sulfated polysaccharides for biomedical applications: A review. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 4708–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yang, M.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, Q.; Chai, G.; Lu, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhang, S.; Ding, C. Structural modification and biological activity of polysaccharides. Molecules 2023, 28, 5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeewa, K.A.; Herath, K.; Kim, Y.S.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from seaweeds and microalgae. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 167, 117266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M.K.; Hou, C.Y.; Dong, C.D.; Patel, A.K.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lin, M.C.; Xu, Z.Y.; Perumal, P.K.; Kuo, C.H.; Huang, C.Y. Production and characterization of Durvillaea antarctica enzyme extract for antioxidant and anti-metabolic syndrome effects. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, N.; Mao, X. Incidental vs. engineered nanoparticles in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: Pathological pathways and therapeutic interventions. Nano Res. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.D. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Dhapola, R.; Sharma, P.; Paidlewar, M.; Vellingiri, B.; Medhi, B.; Hari Krishna Reddy, D. Unravelling neuronal death mechanisms: The role of cytokines and chemokines in immune imbalance in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 112, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, U.; Bir, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Cytotoxicity of mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone: A complex interplay of cell death pathways. Bioenerg. Commun. 2022, 2022, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, J.M.; Wu, S.J.; Tsai, H.T. Isolation and characterization of fish scale collagen from tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) by a novel extrusion-hydro-extraction process. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Liang, F.; Fang, G.; Jiao, J.; Huang, C.; Tian, Q.; Zhu, B.; Deng, Y.; Han, S.; Zhou, X. An integrated pretreatment strategy for enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency of poplar: Hydrothermal treatment followed by a twin-screw extrusion. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 211, 118169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, W.C.; Hong, Y.H.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Patel, A.K.; Guo, H.R.; Kuo, C.H.; Huang, C.Y. Extraction, biochemical characterization, and health effects of native and degraded fucoidans from Sargassum crispifolium. Polymers 2022, 14, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ale, S.; Dhungana, P.; Howieson, J.; Bhattarai, R.R. Effective valorisation of cereal lignocellulosic waste: A review of pretreatment techniques to enhance microstructural modification. Sustain. Food Technol. 2026; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E.O.; Kanwugu, O.N.; Panda, P.K.; Adadi, P. Marine fucoidans: Structural, extraction, biological activities and their applications in the food industry. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 142, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Hong, T.; Guo, S.; Cai, M.; Zhao, L.; Su, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, C.; et al. Antioxidant and anticancer properties of fucoidan isolated from Saccharina japonica brown algae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera Barragán, J.A.; Olivieri, G.; Boboescu, I.; Eppink, M.; Wijffels, R.; Kazbar, A. Enzyme assisted extraction for seaweed multiproduct biorefinery: A techno-economic analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 948086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, E.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Enzymatic extraction of fucoxanthin from brown seaweeds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 2195–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Ma, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhou, H.; He, Y.; Ren, D.; Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Wu, L. Enzyme-assisted extraction of fucoidan from Kjellmaniella crassifolia based on kinetic study of enzymatic hydrolysis of algal cellulose. Algal Res. 2022, 66, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna Perumal, P.; Huang, C.Y.; Chen, C.W.; Anisha, G.S.; Singhania, R.R.; Dong, C.D.; Patel, A.K. Advances in oligosaccharides production from brown seaweeds: Extraction, characterization, antimetabolic syndrome, and other potential applications. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 2252659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhan, Y.; Li, N.; Yu, D.; Gao, W.; Gu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Li, R.; Zhu, C. Enzymatic preparation of low-molecular-weight Laminaria japonica polysaccharides and evaluation of its effect on modulating intestinal microbiota in high-fat-diet-fed mice. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 820892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, T.U.; Nagahawatta, D.; Fernando, I.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, J.S.; Jeon, Y.J. A review on fucoidan structure, extraction techniques, and its role as an immunomodulatory agent. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, A.; Sobuj, M.K.A.; Islam, M.S.; Chakroborty, K.; Tasnim, N.; Ayon, M.H.; Hossain, M.F.; Rafiquzzaman, S.M. Seaweed polysaccharides: Sources, structure and biomedical applications with special emphasis on antiviral potentials. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusch, K.L.; Torres, M.D.; Domínguez, H. Characterization, ultrafiltration, depolymerization and gel formulation of Ulvans extracted via a novel ultrasound-enzyme assisted method. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 111, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzkar, N.; Rungsardthong, V.; Tamadoni Jahromi, S.; Laraib, Q.; Das, R.; Babich, O.; Sukhikh, S. A recent update on fucoidonase: Source, isolation methods and its enzymatic activity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1129982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Shang, N.; Wu, K.; Liao, W. Recent advances in the structure, extraction, and biological activity of Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharides. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; ur Rehman, I. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Pei, Y.P.; Fang, Z.X.; Sun, P.L. Effects of partial desulfation on antioxidant and inhibition of DLD cancer cell of Ulva fasciata polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 65, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Vásquez, M.R.; Alvarado-García, P.A.A.; Youssef, F.S.; Ashour, M.L.; Bogari, H.A.; Elhady, S.S. FTIR characterization of sulfated polysaccharides obtained from Macrocystis integrifolia algae and verification of their antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory potency in vitro and in vivo. Mar. Drugs 2022, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Vinosha, M.; Marudhupandi, T.; Rajasekar, P.; Prabhu, N.M. Isolation of fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum brown algae: Structural characterization, in vitro antioxidant and anticancer activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sathuvan, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Tang, S.; Liu, Y.; Cheong, K.L. Characterization of polysaccharides from different species of brown seaweed using saccharide mapping and chromatographic analysis. BMC Chem. 2021, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Bleha, R.; Synytsya, A.; Pohl, R.; Hayashi, K.; Yoshinaga, K.; Nakano, T.; Hayashi, T. Mekabu fucoidan: Structural complexity and defensive effects against avian influenza A viruses. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadj Ammar, H.; Lajili, S.; Ben Said, R.; Le Cerf, D.; Bouraoui, A.; Majdoub, H. Physico-chemical characterization and pharmacological evaluation of sulfated polysaccharides from three species of Mediterranean brown algae of the genus Cystoseira. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.G.; Mischnick, P.; Rosenau, T.; Böhmdorfer, S. Refined linkage analysis of the sulphated marine polysaccharide fucoidan of Cladosiphon okamuranus with a focus on fucose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 342, 122302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayabaskar, P.; Vaseela, N.; Thirumaran, G. Potential antibacterial and antioxidant properties of a sulfated polysaccharide from the brown marine algae Sargassum swartzii. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2012, 10, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immanuel, G.; Sivagnanavelmurugan, M.; Marudhupandi, T.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Palavesam, A. The effect of fucoidan from brown seaweed Sargassum wightii on WSSV resistance and immune activity in shrimp Penaeus monodon (Fab). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 32, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usoltseva, R.V.; Zueva, A.O.; Malyarenko, O.S.; Anastyuk, S.D.; Moiseenko, O.P.; Isakov, V.V.; Kusaykin, M.I.; Jia, A.; Ermakova, S.P. Structure and metabolically oriented efficacy of fucoidan from brown alga Sargassum muticum in the model of colony formation of melanoma and breast cancer cells. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Riquelme, C.L.; Maldonado, E.A.L. Multifunctional characterization of fucoidan: Structural insights and efficient removal of toxic metal ions. J. Res. Updates Polym. Sci. 2025, 14, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmes, J.; Mikkelsen, M.D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Tran, V.H.N.; Meier, S.; Nielsen, M.S.; Ding, M.; Seekamp, A.; Meyer, A.S.; Fuchs, S. Depolymerization of fucoidan with endo-fucoidanase changes bioactivity in processes relevant for bone regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 119286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhahri, M. Cystoseira myrica: From beach-cast seaweed to fucoidan with antioxidant and anticoagulant capacity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1327408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichert, A.; Le Gall, S.; Klau, L.J.; Laillet, B.; Rogniaux, H.; Aachmann, F.L.; Hehemann, J.-H. Ion-exchange purification and structural characterization of five sulfated fucoidans from brown algae. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravana, P.S.; Karuppusamy, S.; Rai, D.K.; Wanigasekara, J.; Curtin, J.; Tiwari, B.K. Elimination of ethanol for the production of fucoidans from brown seaweeds: Characterization and bioactivities. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, L.; Rajpoot, K.; Jeeves, M.; Ludwig, C. Automated analysis for multiplet identification from ultra-high resolution 2D-1H, 13C-HSQC NMR spectra. Wellcome Open Res. 2023, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xi, W.; Chen, N.; Wei, X.; Liu, H.; Duan, J.-a.; Xiao, P. Glycoside hydrolases: Effective tools to enhance the bioactivities and improve the properties of food-derived polysaccharides. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 14, 9250281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabate, B.; Daub, C.D.; Malgas, S.; Pletschke, B.I. Characterisation of Sargassum elegans fucoidans extracted using different technologies: Linking their structure to α-glucosidase inhibition. Algal Res. 2025, 85, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, N.; Ohmes, J.; Mikkelsen, M.D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Blümel, M.; Wang, F.; Tasdemir, D.; Seekamp, A.; Meyer, A.S.; Fuchs, S. Impact of enzymatically extracted high molecular weight fucoidan on lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial activation and leukocyte adhesion. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.D.; Ma, D.Y.; Shi, S.R.; Song, S.L.; Li, W.L.; Qi, X.H.; Guo, S.D. Preparation and bioactivities of low-molecular weight fucoidans and fuco-oligosaccharides: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 356, 123377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, S.J.; Veerakumarasivam, A.; Teoh, S.L.; Lim, W.L.; Chew, J. Lactoferrin protects against rotenone-induced toxicity in dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells through the modulation of apoptotic-associated pathways. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 74, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, Z.B.; Santiago-Padilla, V.; Lim, M.; Boschen, S.L.; Atilla, P.; McLean, P.J. Optimizing SH-SY5Y cell culture: Exploring the beneficial effects of an alternative media supplement on cell proliferation and viability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ke, C.; Li, D. Significance of programmed cell death pathways in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H. Fucoidan suppresses mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinum-induced neuronal cytotoxicity via regulation of PGC-1α expression. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, C.H.; Chen, P.W. Compressional-puffing pretreatment enhances neuroprotective effects of fucoidans from the brown seaweed Sargassum hemiphyllum on 6-hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Molecules 2017, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Han, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, T.; He, J.; Du, W.; Cao, X.; Gan, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Rosmarinic acid attenuates rotenone-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Parkinson’s disease cell model through Abl inhibition. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, A.C.; El Baradie, K.B.Y.; Hamrick, M.W. Targeting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to prevent age-associated cell damage and neurodegeneration. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6626484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, P.; Gerle, C.; Halestrap, A.P.; Jonas, E.A.; Karch, J.; Mnatsakanyan, N.; Pavlov, E.; Sheu, S.S.; Soukas, A.A. Identity, structure, and function of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: Controversies, consensus, recent advances, and future directions. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1869–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, B.; Koshenov, Z.; Malli, R.; Graier, W.F. Implications of mitochondrial membrane potential gradients on signaling and ATP production analyzed by correlative multi-parameter microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadsena, S.; Jenner, A.; García-Sáez, A.J. Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization at the single molecule level. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3777–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianello, C.; Dal Bello, F.; Shin, S.H.; Schiavon, S.; Bean, C.; Magalhães Rebelo, A.P.; Knedlík, T.; Esfahani, E.N.; Costiniti, V.; Lacruz, R.S.; et al. High-throughput microscopy analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential in 2D and 3D models. Cells 2023, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]