Abstract

The catalytic removal of toluene, a representative aromatic volatile organic compound (VOC), requires efficient and stable catalysts. This study systematically investigated the effect of B-site doping with transition metals (Fe, Cu, and Ni) on the catalytic performance of LaMnO3 perovskite for toluene oxidation. The LaMn0.5X0.5O3 catalysts were synthesized via a sol–gel method and evaluated. The LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 catalysts exhibited the optimal catalytic performance, achieving toluene conversion temperatures of 243 °C at 50% conversion (T50) and 296 °C at 90% conversion (T90). Comprehensive characterization revealed that Ni doping effectively refined the catalyst’s microstructure (grain size decreased to 19.21 nm), increased the concentration of surface-active oxygen species (142.7%), elevated the Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio to 0.65, and enhanced lattice oxygen mobility. These modifications collectively contributed to its outstanding catalytic activity. The findings demonstrate that targeted B-site doping, particularly with Ni, is a promising strategy for engineering efficient perovskite catalysts for VOC abatement.

1. Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are precursors of secondary particulate matter and O3. They drive atmospheric pollution and harm human health [1,2]. Aromatic VOCs are widely present in daily life and industrial production environments. In relatively enclosed spaces, these compounds can cause irritation to the eyes, nasal passages, and throat and may lead to symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, impaired memory and vision, and, in severe cases, even death [3]. Further studies have shown that aromatic VOCs can undergo photochemical reactions with nitrogen oxides (NOx), generating various secondary pollutants, including tropospheric ozone and photochemical smog [4]. Aromatic VOCs possess stable benzene rings. These rings resist degradation and enhance toxicity. Efficient removal of aromatic VOCs remains a significant challenge.

Among the treatments for aromatic VOCs, catalytic oxidation is widely used [5,6]. It is efficient, energy-saving, and eco-friendly. The required temperature is substantially lower than that of direct combustion. Dioxins and other harmful by-products are suppressed [7]. Perovskites are regarded as one of the promising catalysts or catalyst supports due to their high catalytic activity, low cost, and excellent thermal stability.

Perovskite is a classic ABO3 mixed oxide [8]. The A-site ion stabilizes the framework via twelve-fold cuboctahedral coordination with oxygen atoms. The B-site cation sits in an octahedral site with six oxygen atoms. This unique coordination activates organic molecules and tunes oxygen species [9,10,11]. Álvarez-Galván et al. [12] tested LaBO3 (B = Ni, Co, Cr, Mn) perovskites in methyl ethyl ketone oxidation. It was found that B-site substitution clearly boosts activity. Mn and Co are the preferred B-site cations in perovskite oxides for VOCs removal. Weng et al. [13] studied the phosphoric acid etching of La3Mn2O7+δ for the catalytic oxidation of chlorinated organics. This etching enhanced lattice oxygen mobility, increased proton donor availability, and enriched Mn(IV) species. These effects led to superior catalytic activity toward dichloromethane degradation. Pan et al. [14] synthesized LaFe1−xCoxO3 (x = 0–0.3) perovskite catalysts and systematically investigated the effects of cobalt doping on the structure, redox properties, and total oxidation activity of LaFeO3 for propylene. It was found that the introduction of cobalt, while slightly reducing the specific surface area, significantly enhanced the reducibility, oxygen mobility, and quantity of surface-active oxygen species of the material. Ansari et al. [15] prepared Ce3+-doped LaMnO3 perovskite catalysts. Their study revealed that Ce3+ doping effectively modulates the Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio and increases the oxygen vacancy concentration. Furthermore, it enhances oxygen species migration, which collectively leads to a significant improvement in catalytic performance for benzyl alcohol oxidation. Li et al. [16] reported that the La0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3 perovskite, through Sr/Fe co-doping, optimizes the Co4+ valence state and oxygen vacancy concentration. This catalyst exhibits excellent activity in toluene catalytic combustion, following the Mars–van Krevelen (MVK) mechanism, in which lattice oxygen migration plays a key role. Zhang et al. [17] discovered that partially substituting the B-site Mn in LaMnO3 perovskite with Co, Ni, or Fe significantly enhanced its catalytic activity for vinyl chloride oxidation. Through a combination of multiple characterization techniques, it was found that this activity improvement is primarily attributed to the enhanced low-temperature reducibility of the B-site, the increased quantity of surface-adsorbed oxygen species, and the formation of oxygen vacancies. The unique structure of perovskite allows flexible ion substitution and doping while maintaining the crystal structure intact [18]. Partial substitution at the A- or B-site exploits valence and radius differences to tune physicochemical properties and enhance catalytic activity [19].

This study employs a sol–gel method to achieve controlled B-site doping in LaMnO3, synthesizing LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, Ni) based on the ionic radius differences in transition metals. The evolution of physicochemical properties in the modified catalysts was systematically investigated using multiple characterization techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and oxygen temperature-programmed desorption (O2-TPD). The research aims to establish structure-activity relationships between doped perovskite and toluene removal performance, thereby elucidating the synergistic catalytic oxidation mechanism of multiple metal sites for toluene elimination.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Evaluation of the Catalytic Performance

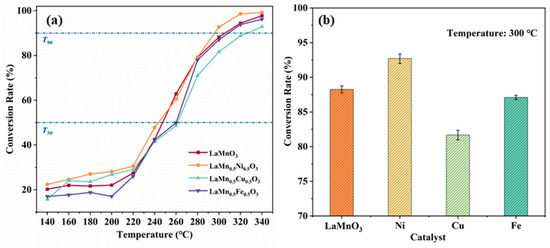

As shown in Figure 1a, the performance curves of toluene catalytic oxidation over the prepared LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, Ni) are presented. The temperature at 50% conversion (T50) and that at 90% conversion (T90) are summarized in Table 1. The results indicate that not all metal ion doping at the B-site of LaMnO3 enhance the catalytic performance for toluene oxidation. Among them, the LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3 exhibited the poorest performance (T50 = 262 °C, T90 = 326 °C). Similarly, the LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3 also showed relatively low activity (T50 = 260 °C, T90 = 309 °C). However, the catalytic performance of LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 improved to some extent (T50 = 243 °C, T90 = 296 °C). Compared to LaMnO3, the T50 was lowered by 4 °C and the T90 by 9 °C.

Figure 1.

Performance curves of LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, Ni) catalyzed oxidation of toluene (a) and conversion of toluene by the catalyst at 300 °C (b).

Table 1.

Characteristic parameters of catalytic oxidation of toluene with LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, Ni).

As shown in Figure 1b, the toluene conversion rates of the LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, Ni) are presented at 300 °C. The doping of different metal ions at the B-site exerted varying effects on catalytic performance. Specifically, LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3 and LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3 exhibited inhibitory effects. In contrast, LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibited the highest toluene conversion rate of 92.7%, which was 5% higher than that of LaMnO3.

In summary, B-site Ni doping is beneficial for enhancing catalytic activity. The toluene oxidation performance of the prepared catalysts, ranked from lowest to highest, follows the order: LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3 < LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3 < LaMnO3 < LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3.

2.2. XRD Analysis

To determine the crystal structure of the LaMn0.5X0.5O3 catalysts synthesized by the sol–gel method, XRD analysis was performed on the catalyst powders.

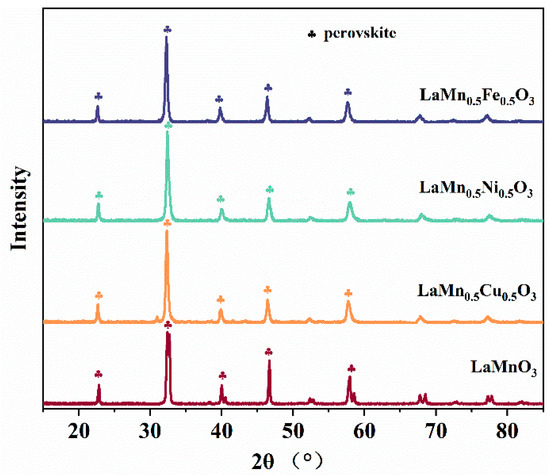

As shown in the XRD pattern in Figure 2, the diffraction peaks of LaMnO3 appear at 22.83°, 32.36°, 32.66°, 39.97°, 46.64°, and 57.90°, which match the characteristic peaks of the LaMnO3 phase recorded in the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) database (PDF#82-1152). These diffraction peaks correspond to the crystal planes (012), (110), (104), (202), (024), and (214), respectively. The characteristic diffraction peaks of the LaMn0.5X0.5O3 series appear at 22.902°, 32.611°, 40.224°, 46.788°, 52.708°, 58.194°, 68.321°, 73.108°, 77.775°, 82.362°, and 86.899°, consistent with an orthorhombic perovskite structure (JCPDS#75-0440). The corresponding crystal planes are (100), (110), (111), (200), (210), (211), (220), (300), (310), (311), and (222), respectively.

Figure 2.

XRD spectra of LaMnO3 doped with different metal ions at the B-site (X = Fe, Cu, Ni).

The introduction of Cu, Ni, and Fe elements at the B-site is likely to result in slight local structural distortions in the LaMnO3 perovskite crystal structure [20,21,22]. However, all catalyst samples maintain a single-phase pure perovskite structure, with no detectable impurity diffraction peaks. This indicates that the incorporation of these three elements does not disrupt the perovskite crystal structure or generate new crystal phases.

Table 2 presents the grain size of the prepared catalysts, calculated using the Scherrer equation [23]. As shown in the table, compared with LaMnO3, the introduction of a second metal element at the B-site leads to a reduction in grain size for all catalysts. This phenomenon occurs because the incorporation of a second metal component at the B-site causes perovskite grains to segregate at grain boundary regions during growth [24]. This segregation forms local energy barriers that inhibit grain boundary migration and consequently hinder grain growth [25].

Table 2.

Grain size of LaMnO3 doped with different metal ions at the B-site.

The LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibits the smallest grain size of 19.21 nm. The metal-doped perovskite exhibits a smaller grain size compared to LaMnO3. This reduction in grain size contributes to an increased specific surface area. Based on previous studies [26,27,28], an increased specific surface area is generally considered conducive to promoting the exposure of active sites, which may be one of the factors contributing to the observed enhancement in catalytic performance.

2.3. SEM Analysis

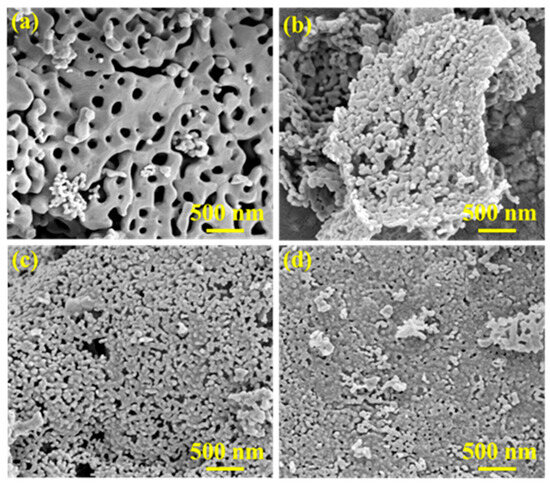

The surface morphology of a series of prepared LaMn0.5X0.5O3 was investigated using SEM. As presented in Figure 3, the LaMnO3 exhibits a porous structure with relatively large grain sizes, along with particle agglomeration and disordered arrangement.

Figure 3.

SEM of LaMnO3 (a), LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 (b), LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3 (c), LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3 (d) catalysts.

In contrast, the B-site-doped perovskites demonstrate significantly increased pore density. The catalyst particles appear quasi-spherical and are well-dispersed in an ordered manner. This is attributed to the introduction of a second metal ion at the B-site, which promotes crystallite refinement and leads to smaller particle sizes.

Furthermore, the SEM images reveal that the surface of the undoped perovskite catalyst is relatively smooth. In contrast, the B-site-doped catalysts exhibit rougher surfaces with more uniform pores. This porous structure is a result of thermal decomposition during the high-temperature calcination step in the catalyst preparation process. It originates from the release of gases from nitrates and citric acid, which generate abundant pore channels.

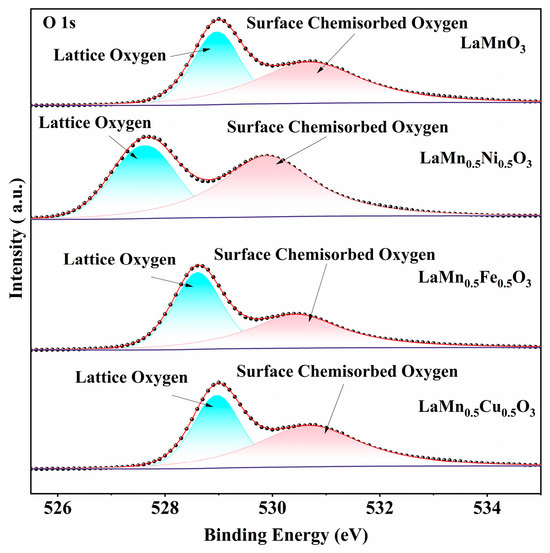

2.4. XPS Analysis

Figure 4 presents the XPS O 1s envelopes of B-site Ni-, Fe-, and Cu-doped perovskites. Each spectrum is deconvoluted into two peaks: lattice oxygen (~529 eV) and surface chemisorbed oxygen (~531 eV) [29,30]. Deconvolution analysis of the XPS O 1s spectra reveals that B-site doping effectively reduces the binding energy of oxygen species in the catalyst. Compared to the oxygen species in LaMnO3, a chemical shift of approximately 0.4–0.8 eV was observed. Among them, the LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibits the lowest oxygen species binding energy. The decreased binding energy of surface chemisorbed oxygen facilitates its desorption from the perovskite surface, thereby promoting participation in toluene oxidation. Meanwhile, the reduction in lattice oxygen binding energy enhances the mobility of lattice oxygen toward surface active sites [31].

Figure 4.

XPS O 1s spectra of LaMnO3 doped with different metal ions at the B-site.

In catalytic reactions, active oxygen species participate in the oxidation of reactants. Therefore, a higher concentration of active oxygen in the catalyst can effectively enhance its activity. As shown in Table 3, LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3 exhibits a higher surface oxygen content (153.8%) compared to that of LaMnO3 (128.3%). In toluene catalytic oxidation, surface chemisorbed oxygen species act as the key active oxygen, and their concentration exhibits a positive correlation with catalytic activity [32,33]. This indicates that B-site doping effectively increases both the surface chemisorbed oxygen content and catalytic activity. Doping was shown to increase oxygen vacancy concentration in perovskites, thereby enriching surface chemisorbed oxygen and improving catalytic performance [34].

Table 3.

Surface oxygen content of LaMnO3 doped with different metal ions at the B-site.

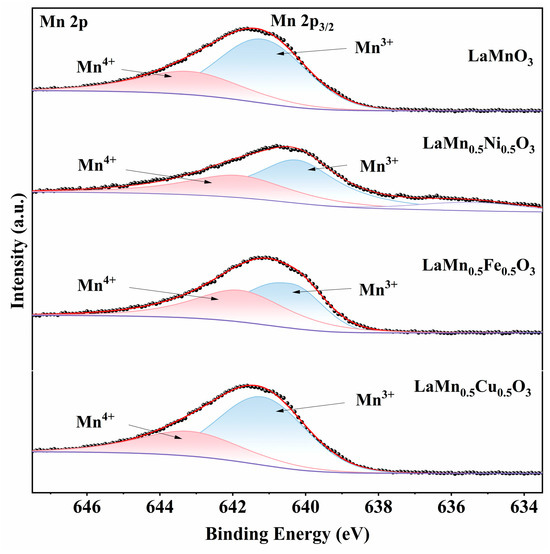

Figure 5 displays the asymmetric Mn 2p XPS spectra of the catalysts. As shown, the Mn 2p3/2 peak was deconvoluted into two sub-peaks corresponding to Mn3+ (~640.1–641.1 eV) and Mn4+ (~642.0–643.0 eV) [34,35]. As listed in Table 4, B-site transition metal doping promotes the formation of higher Mn oxidation states. This confirms that B-site modification alters the ionic valence distribution in perovskites and favors higher oxidation states.

Figure 5.

XPS Mn 2p spectra of LaMnO3 doped with different metal ions at the B-site.

Table 4.

Mn content in LaMnO3 doped with different metal ions at the B-site.

After B-site doping, the elevated Mn4+ content enhances electron attraction and acceptance capabilities, thereby improving the catalyst’s oxidative properties and charge transfer efficiency. Concurrently, the higher Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio suggests increased oxygen vacancy concentration on the catalyst surface. However, only optimized doping elements and stoichiometry can simultaneously achieve both high Mn4+/Mn3+ ratios and superior toluene oxidation activity. This explains why LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibits superior catalytic performance.

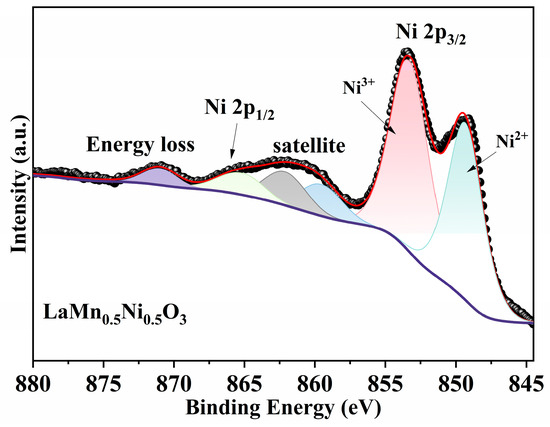

As shown in Figure 6, two main peaks corresponding to Ni 2p3/2 (845–860 eV) and Ni 2p1/2 (∼870 eV) are observed in the range of 846–890 eV for LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3. Deconvolution analysis of the Ni 2p3/2 peak reveals two characteristic peaks corresponding to Ni3+ (~853 eV) and Ni2+ (~850 eV) [36]. The satellite peak of Ni 2p3/2 is observed in the 856–869 eV range. The coexistence of Ni3+ and Ni2+ in the Ni 2p spectrum indicates the presence of defects in Ni2+ ions, which can generate oxygen vacancies [37].

Figure 6.

XPS Ni 2p spectra of LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3.

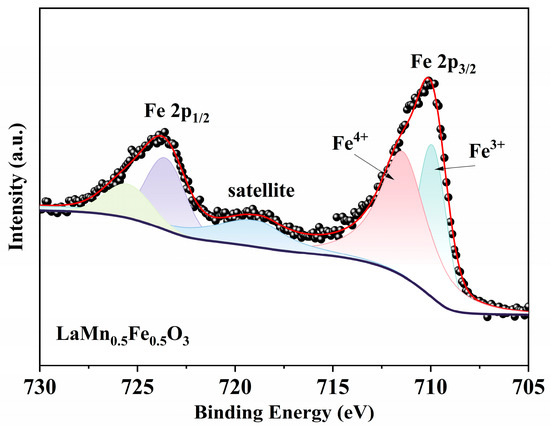

From Figure 7 and the standard XPS spectra of iron, it can be observed that the LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3 contains iron ions in both Fe2+ (peak corresponding to the Fe 2p3/2 orbital) and Fe3+ (peak corresponding to the Fe 2p1/2 orbital) valence states [38]. The peak of the Fe 2p3/2 orbital can be deconvoluted into two components corresponding to Fe3+ (~710 eV) and Fe4+ (~711 eV). Similarly, the peak of the Fe 2p1/2 orbital can be deconvoluted into two components attributed to Fe3+ (~724 eV) and Fe4+ (~725 eV). Additionally, a satellite peak of Fe 2p3/2 is observed at 718.8 eV [39].

Figure 7.

XPS Fe 2p spectra of LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3.

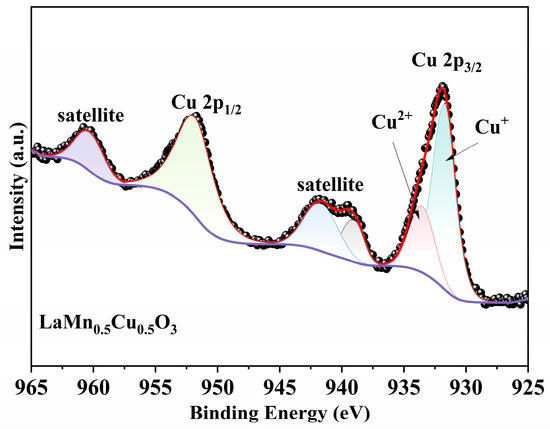

Figure 8 displays the XPS Cu 2p spectrum of the LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3. The peak corresponding to Cu 2p3/2 can be deconvoluted into two components, attributable to the reduced state Cu+ (931.7 eV) and the oxidized state Cu2+ (933.5 eV) [40,41]. The spectral features between 936–946 eV and 956–965 eV are identified as satellite peaks of Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2, respectively [42].

Figure 8.

XPS Cu 2p spectra of LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3.

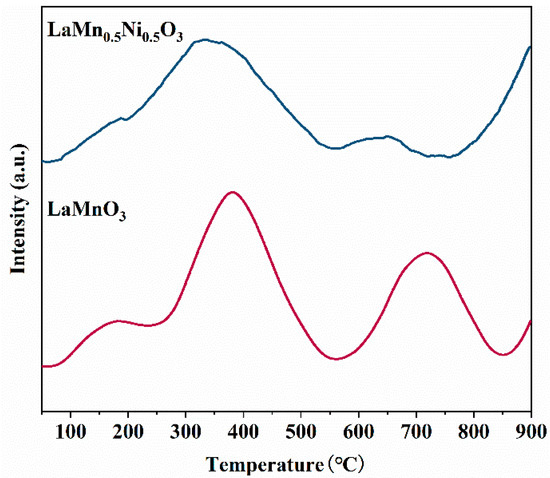

2.5. O2-TPD Analysis

Perovskite catalysts exhibit exceptional oxygen storage capacity and oxygen mobility due to their unique crystal structure. The concentration of oxygen vacancies in perovskites can be modulated by varying the type and content of B-site metal ions [43]. The oxygen desorption profile of perovskite catalysts typically comprises two distinct features: α-oxygen and β-oxygen [44]. The α-oxygen desorption peak (below 500 °C) corresponds to surface-adsorbed oxygen species at vacancy sites, while the β-oxygen peak (600–800 °C) arises from the release of bulk lattice oxygen. As shown in Figure 9, Ni doping at the B-site lowers the desorption temperatures of both α-oxygen and β-oxygen. This indicates that the LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 possesses a higher oxygen vacancy concentration and enhanced oxygen mobility at lower temperatures. Ni doping enhances the content of chemically adsorbed oxygen on the catalyst surface. This further increases the oxygen vacancy concentration. Chemically adsorbed surface oxygen has a weaker binding energy. This makes it more readily adsorbed and desorbed, thereby improving catalytic activity. Thus, Ni doping facilitates the formation of surface oxygen, demonstrating higher reactivity of surface-adsorbed oxygen.

Figure 9.

O2-TPD curves of the catalysts LaMnO3 and LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3.

In summary, the LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibits significantly enhanced catalytic activity compared to the LaMnO3, which aligns with the toluene catalytic oxidation performance tests.

In summary, LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibits the most favorable overall characteristics: it possesses an appropriate Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio, a high content of surface-adsorbed oxygen, the smallest grain size, and relatively low desorption temperatures for both lattice oxygen and adsorbed oxygen. In contrast, although LaMn0.5Cu0.5O3 shows the highest surface oxygen content, its higher binding energy hinders the migration of lattice oxygen to surface active sites. Meanwhile, LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3 has the highest Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio, but the lowest surface oxygen content. Consequently, LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 achieves the optimal balance among microstructure, surface chemistry, and oxygen mobility, which contributes to its highest catalytic activity in toluene oxidation.

3. Materials and Methods

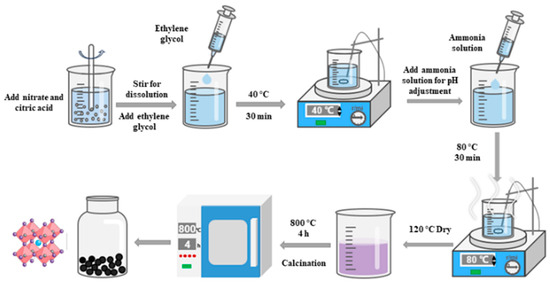

3.1. Preparation of Perovskite Samples

In this study, LaMnO3 and a series of LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, Ni) were synthesized via the sol–gel method, with citric acid as the complexing agent. The chemical reagents used in the preparation of the perovskite samples are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Chemical reagents used for the synthesis of perovskite samples.

The preparation procedure is shown in Figure 10. First, stoichiometric amounts of nitrate salts were weighed and dissolved in ultrapure water. Citric acid monohydrate was weighed as the complexing agent at a molar ratio of 1:1.5 relative to the total metal cations. After being completely dissolved in the mixed solution, a small amount of ethylene glycol was added as a polymerization agent. The mixture was heated at 40 °C under stirring for 30 min. Ammonia solution was used to adjust the pH to neutral, yielding a neutral precursor solution. The solution was continuously stirred at 80 °C. As polymerization proceeded, the viscosity increased until a wet gel formed, characterized by the cessation of flow and no deformation upon container tilting. The wet gel was dried at 120 °C to obtain a dry gel. Finally, the dry gel was calcined in a muffle furnace at 800 °C for 4 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting catalyst was ground and sieved to obtain powdered catalyst with a particle size of less than 75 μm.

Figure 10.

Preparation process of perovskite catalyst.

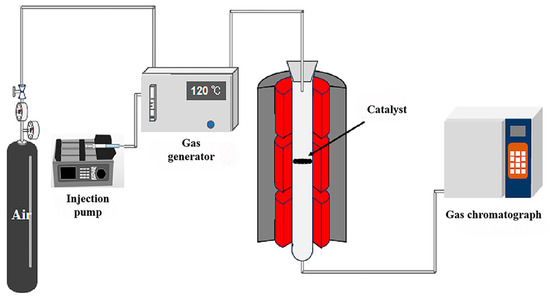

3.2. Experimental Process of the Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene

The experiment for evaluating the catalytic oxidation performance of perovskite on toluene was conducted in a fixed-bed reaction system set up in the laboratory, as illustrated in Figure 11. The experimental setup consists of four main components: the gas delivery system, gas mixing system, catalytic oxidation reaction system, and gas detection system.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the experimental process for the performance of catalyst in catalytic oxidation of toluene.

The gas delivery system comprises gas cylinders, pressure-reducing valves, associated gas pipelines, and flow meters. The gas mixing system includes a syringe pump and a VOCs generator. The reaction system is composed of a vertical tube furnace and a quartz reactor with a diameter of 48 mm. For gas detection, a gas chromatograph equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector was employed for analysis.

Based on preliminary experiments, the reaction space velocity was determined to be 18,000 mL/(g·h). Before starting the experiment, the setup was assembled and tested for airtightness. A catalyst sample weighing 1.0 ± 0.001 g was weighed in advance and placed on the air distributor inside the quartz tube reactor. The toluene flow rate was adjusted to maintain a reaction concentration of 1000 ppm, and the temperature control system was set to the desired reaction temperature. The reactant mixture of toluene and air was then passed through the catalytic bed, where oxidation reactions occurred.

4. Conclusions

Through a systematic investigation of doping strategies with B-site transition metals (Fe, Cu, and Ni), the crystal structure and surface properties of LaMnO3 were successfully modulated. By combining multiscale characterization and catalytic performance tests, this study clarifies the influence of different B-site metal dopants on the physicochemical properties of the material and its performance in the catalytic oxidation of toluene. The results indicate that the activity of LaMn0.5X0.5O3 (X = Fe, Cu, and Ni) exhibits significant metal dependence, with LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 demonstrating the best catalytic performance. The toluene conversion temperatures were significantly reduced, with T50 at 243 °C and T90 at 296 °C. Further characterization revealed that Ni doping effectively refines the grain size, decreasing it from 24.70 nm to 19.21 nm. It also increases the surface-adsorbed oxygen content from 128.3% to 142.7%. Furthermore, it significantly enhances the Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio from 0.46 to 0.65. The synergistic improvement of these properties collectively contributes to the enhanced catalytic performance. In summary, LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3 exhibits optimal catalytic activity for toluene oxidation, owing to its optimized microstructure and surface chemical properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C. and Y.W.; methodology, Y.W. and X.S.; validation, X.C., Y.W. and J.L.; investigation, Z.S.; data curation, X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. and X.S.; writing—review and editing, X.C.; visualization, F.Z. and Z.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by project of Technical Innovation of Hainan Scientific Research Institutes (KYYSGY2024-002).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaoliang Shi was employed by the company China Mobile Communications Group Henan Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| O2-TPD | Oxygen temperature-programmed desorption |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

References

- Kim, H.-S.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kang, S.-H.; Ryu, J.-H.; Park, N.-K.; Yun, D.-S.; Bae, J.-W. Noble-Metal-Based Catalytic Oxidation Technology Trends for Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Removal. Catalysts 2022, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.; Kim, S.; Jung, J.; Park, J.-H.; Hwang, W.S.; Jeon, D.-W.; Kim, H. Photocatalytic Degradation of VOCs Using Ga2O3-Coated Mesh for Practical Applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.S.; Razzak, S.A.; Hossain, M.M. Catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—A review. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 140, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ying, Q.; Kleeman, M.J. Source apportionment of wintertime secondary organic aerosol during the California regional PM10/PM2.5 air quality study. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wen, M.; Li, G.; An, T. Recent advances in VOC elimination by catalytic oxidation technology onto various nanoparticles catalysts: A critical review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 281, 119447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlianskii, P.V.; Kustov, A.L.; Timofeeva, M.N.; Kustov, L.M. Microwave irradiation as an instrument for tuning of physicochemical and catalytic properties of MFe2O4 spinels. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2025, 208, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Miao, G.; Pi, Y.; Xia, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Xiao, J. Abatement of various types of VOCs by adsorption/catalytic oxidation: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 1128–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlianskii, P.; Morozov, D.; Kapustin, G.; Davshan, N.; Kalmykov, K.; Chernyshev, V.; Kustov, A.; Kustov, L. Correlations between synthetic conditions and catalytic activity of LaMO3 perovskite-like oxide materials (M: Fe, Co, Ni): The key role of glycine. ChemPhysMater 2025, 4, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimov, E.Y.; Rogov, V.A.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Isupova, L.A.; Tsybulya, S.V. Microstructural Changes in La0.5Ca0.5Mn0.5Fe0.5O3 Solid Solutions under the Influence of Catalytic Reaction of Methane Combustion. Catalysts 2019, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shen, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Su, Y.; Zhao, Z. Catalytic performance of NO oxidation over LaMeO3 (Me = Mn, Fe, Co) perovskite prepared by the sol–gel method. Catal. Commun. 2013, 37, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Bi, L.; Zhang, J.; Cao, H.; Zhao, X.S. The role of oxygen vacancies of ABO3 perovskite oxides in the oxygen reduction reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 1408–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Galván, M.C.; de la Peña O’Shea, V.A.; Arzamendi, G.; Pawelec, B.; Gandía, L.M.; Fierro, J.L.G. Methyl ethyl ketone combustion over La-transition metal (Cr, Co, Ni, Mn) perovskites. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 92, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Meng, Q.; Liu, J.; Jiang, W.; Pattisson, S.; Wu, Z. Catalytic Oxidation of Chlorinated Organics over Lanthanide Perovskites: Effects of Phosphoric Acid Etching and Water Vapor on Chlorine Desorption Behavior. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhang, W.; Ferronato, C.; Valverde, J.L.; Giroir-Fendler, A. Boosting propene oxidation activity over LaFeO3 perovskite catalysts by cobalt substitution. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2022, 643, 118779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.A.; Ahmad, N.; Alam, M.; Adil, S.F.; Ramay, S.M.; Albadri, A.; Ahmad, A.; Al-Enizi, A.M.; Alrayes, B.F.; Assal, M.E.; et al. Physico-chemical properties and catalytic activity of the sol-gel prepared Ce-ion doped LaMnO3 perovskites. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Yin, K.; Jia, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, J.; Yang, L. Understanding the mechanisms of catalytic enhancement of La-Sr-Co-Fe-O perovskite-type oxides for efficient toluene combustion. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Zhan, W.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, G.; Baylet, A.; Giroir-Fendler, A. Catalytic oxidation of vinyl chloride emission over LaMnO3 and LaB0.2Mn0.8O3 (B = Co, Ni, Fe) catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, M.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S. A review of recent advances in catalytic combustion of VOCs on perovskite-type catalysts. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019, 23, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, S.; Xiang, W. Oxygen vacancy induced performance enhancement of toluene catalytic oxidation using LaFeO3 perovskite oxides. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387, 124101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.-C.; Ding, M.-W.; Liu, S.-K.; Wu, S.-K.; Lin, Y.-C. Ni-substituted LaMnO3 perovskites for ethanol oxidation. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 5329–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Luo, K.; Tian, H.; Cheng, H.; Giannakis, S.; Song, Y.; He, Z.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Fang, J.; et al. Transforming Plain LaMnO3 Perovskite into a Powerful Ozonation Catalyst: Elucidating the Mechanisms of Simultaneous A and B Sites Modulation for Enhanced Toluene Degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 12167–12178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Lv, X.; Wang, X. Theoretical screening method of oxygen carriers with high lattice oxygen activity towards CO oxidation. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 119, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamboli, A.H.; Suzuki, N.; Terashima, C.; Gosavi, S.; Kim, H.; Fujishima, A. Direct Dimethyl Carbonates Synthesis over CeO2 and Evaluation of Catalyst Morphology Role in Catalytic Performance. Catalysts 2021, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Vahidi, H.; Kang, H.; Shah, S.; Xu, M.; Aoki, T.; Rupert, T.J.; Luo, J.; Gilliard-AbdulAziz, K.L.; Bowman, W.J. Tuning grain boundary cation segregation with oxygen deficiency and atomic structure in a perovskite compositionally complex oxide thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 171605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yin, X.; Hong, L. Modification of B-site doping of perovskite LaxSr1−xFe1−y−zCoyCrzO3−δ oxide by Mg2+ ion. Solid State Ion. 2009, 180, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; You, Y.; Yuan, J.; Yin, Y.X.; Li, Y.T.; Xin, S.; Zhang, D. Nickel-Doped La0.8Sr0.2Mn1−xNixO3 Nanoparticles Containing Abundant Oxygen Vacancies as an Optimized Bifunctional Catalyst for Oxygen Cathode in Rechargeable Lithium-Air Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 6520–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Drexler, H.; Ruh, T.; Lindenthal, L.; Schrenk, F.; Bock, J.; Rameshan, R.; Föttinger, K.; Irrgeher, J.; Rameshan, C. Cu-doped perovskite-type oxides: A structural deep dive and examination of their exsolution behaviour influenced by B-site doping. Catal. Today 2024, 437, 114787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.H. Study on the Relation of Lattice Constant Dependence on the Grain Size in Some Nanocrystallites of Perovskite Structures. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 271–273, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, Q.; Li, D. Low-temperature catalytic combustion of chlorobenzene over MnOx–CeO2 mixed oxide catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2008, 9, 2158–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, G.; Dai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y. Efficient low-temperature catalytic combustion of trichloroethylene over flower-like mesoporous Mn-doped CeO2 microspheres. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2011, 102, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Liu, B.; Jia, L.; Li, R. Perovskite materials for highly efficient catalytic CH4 fuel reforming in solid oxide fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 24441–24460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; He, H.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, L.; Xie, Y.; Hu, T. Selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over iron titanate catalyst: Catalytic performance and characterization. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 96, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zheng, A.; Li, H.; He, F.; Huang, Z.; Wei, G.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, Z. Exploration of the mechanism of chemical looping steam methane reforming using double perovskite-type oxides La1.6Sr0.4FeCoO6. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 219, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, K. Evaluation of Fe substitution in perovskite LaMnO3 for the production of high purity syngas and hydrogen. J. Power Sources 2020, 449, 227505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Shen, L. Perovskite-type LaMn1−xBxO3+δ (B = Fe, CO and Ni) as oxygen carriers for chemical looping steam methane reforming. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 128751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.W. Syngas production on a Ni-enhanced Fe2O3/Al2O3 oxygen carrier via chemical looping partial oxidation with dry reforming of methane. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Yu, J. Oxygen vacancies in metal oxides: Recent progress towards advanced catalyst design. Sci. China Mater. 2020, 63, 2089–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Zhang, L.; Miao, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, S. Boosting the high-temperature discharge performance of nickel-hydrogen batteries based on perovskite oxide Co-coated LaFeO3 as proton insertion anode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 14961–14970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, C.; Li, X.; Ding, H.; Shen, C.; Cao, D.; Zhang, L. Development of LaFeO3 modified with potassium as catalyst for coal char CO2 gasification. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 32, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, C.; Wang, X.; Lyu, L.; Sheng, G. Enhanced degradation of organic pollutants over Cu-doped LaAlO3 perovskite through heterogeneous Fenton-like reactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 332, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Liu, C.; Yang, B.; Ding, C.; Mao, S.; Shi, M.; Hong, X.; Wang, F.; Xia, M. The efficient degradation of high concentration phenol by Nitrogen-doped perovskite La2CuO4 via catalytic wet air oxidation: Experimental study and DFT calculation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 322, 124310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Lu, J.; Xie, S.; Dong, L.; Fan, M.; Li, B. LaMnO3-La2CuO4 two-phase synergistic system with broad active window in NOx efficient reduction. Mol. Catal. 2020, 493, 111111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Dong, S.; Li, S.; Yang, G.; Pan, X. A Review on the Catalytic Decomposition of NO by Perovskite-Type Oxides. Catalysts 2021, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.-P.; Zhao, P.-T.; Wang, Y.-X.; Yan, H.; Huang, N. Effect of A-site disubstituted of lanthanide perovskite on catalytic activity and reaction kinetics analysis of coal combustion. Fuel 2020, 260, 116380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.